- 1Institute of Food and Strategic Reserves, Nanjing University of Finance and Economics, Nanjing, China

- 2School of Economics, Nankai University, Tianjin, China

Introduction: To ensure food security and stabilize farmers' incomes, China has implemented the Planting Income Insurance Policy (PIIP). The core objective of this policy is to steer the planting structure towards staple grain crops. However, empirical evidence regarding whether PIIP effectively facilitates planting structure adjustment remains scarce. This study aims to examine this relationship.

Methods: Drawing on data from the 2020 and 2022 China Land Economic Survey (CLES), this study employs a Difference-in-Differences (DID) model to examine the impact of the PIIP on the planting structure of staple grain crops and to investigate its underlying mechanisms.

Results and discussion: The findings of the study indicate the following: first, the implementation of the PIIP significantly facilitated a shift in planting structure towards staple grain crops. In pilot regions where this policy was implemented, the proportion of staple grain crops planted increased by an average of 15.4 percentage points compared to non-pilot regions. Second, a more detailed classification of staple grain crops revealed that the PIIP led to increases in the planting proportion for rice, wheat, and maize by 4.9, 7.1, and 3.4 percentage points, respectively. Thirdly, the policy encouraged the shift by incentivizing farmer participation in insurance, boosting agricultural machinery inputs, and expanding operational scale. Moreover, the impact of PIIP on planting structure differs among household types. A more pronounced impact was observed among households whose farmland has already been certified, whose agricultural labor endowment is weaker, and whose farmland operation scale is larger. Considering these findings, the government should introduce differentiated insurance measures tailored to various types of farming households and continue to optimize the design of the policy-based insurance system to safeguard food security.

1 Introduction

Frequent extreme climate events, escalating geopolitical conflicts, and widespread economic shocks persistently threaten the stability and resilience of global food supply chains. According to the Food Security Information Network (FSIN) and Global Network Against Food Crises (GNAFC) (2025), over 295 million people across 53 countries and territories currently face acute food insecurity, reflecting increasingly severe challenges to global food security. As a globally populous country with over 1.4 billion citizens, China consistently prioritizes national food security as a strategic cornerstone for its survival and development. The country sustains nearly 20% of the global population on less than 9% of the world's arable land, while maintaining a long-standing grain self-sufficiency target exceeding 95%, driving food security into a new phase of development. However, alongside rapid industrialization and urbanization, the comparative advantage driving factor mobility has accelerated the transfer of critical agricultural production factors, such as land resources and rural labor, toward non-agricultural sectors (Li et al., 2025; Huang et al., 2023; Haarsma and Qiu, 2017), leading to tightening resource constraints in grain production. Furthermore, compounded by frequent extreme natural disasters (Zhao et al., 2023), persistently rising prices of agricultural production inputs (Zhu et al., 2022), and the dual challenges of diminishing arable land alongside quality degradation (Cui and Zhong, 2024; Long et al., 2025), the foundation of China's food security is now under unprecedented pressure.

Against this backdrop, how to effectively promote income growth for grain farmers while safeguarding national food security has become a core policy issue. To address this challenge, the Chinese government initiated a pilot program for PIIP for the three major staple crops of rice, wheat, and maize in six provinces, including Inner Mongolia, Liaoning, Anhui, Shandong, Henan, and Hubei, in 2018. The core function of this policy lies in its use of a market-based risk transfer mechanism to comprehensively cover both yield and price risks for staple grains, thereby stabilizing farmers' expected income and reducing production volatility. In light of the pilot's outcomes, the Chinese government amplified the scope of the initiative in 2021, extending it to 13 major grain-producing provinces including Jiangsu and Heilongjiang. Specifically, for Jiangsu Province, in 2021, it conducted pilot schemes for PIIP in 33 counties (districts) including Tongshan District and Feng County. In 2022, the pilot areas were expanded to 56 counties (districts) including Jiangning District in Nanjing City. Regarding premium income and claims expenditure, Jiangsu's agricultural insurance premiums reached RMB 5.32 billion in 2021, with claims payments amounting to RMB 3.77 billion. In 2022, premiums rose to RMB 6.43 billion, while claims expenditure stood at RMB 4.34 billion. In 2023, agricultural insurance premium income reached RMB 7.43 billion, with insurance claims expenditure amounting to RMB 5.26 billion. Regarding insured amounts and premium sharing ratios, the insured amount for the three major staple crops is approximately RMB 1,000-1,300 per mu. The central, provincial, and district/county governments share the planting income insurance premiums at ratios of 35%, 30%, and 25% respectively. Regarding insurance premium rates, the rates for rice, wheat and maize stood at 3.5%, 4% and 5.5% respectively. Theoretically, the policy effect of this precise risk guarantee mechanism for staple grains embodies a profound inherent tension. On the one hand, by significantly reducing income volatility for staple grain production and increasing its certainty equivalent income, it effectively incentivizes risk-averse farmers to safeguard and expand staple crop cultivation (Yu et al., 2018; Liu and Wu, 2024), which is in line with the national grain quantity security strategic goal. On the other hand, according to risk aversion and production decision theory, while stabilizing returns from staple grains, the PIIP objectively increases the relative risk premium for higher-value cash crops and specialty grains which have insufficient coverage. Under the influence of opportunity cost, this readily leads to an excessive diversion of agricultural production factors, such as land, labor, and capital, toward the three major staple grains, strengthening the ‘staple grain' planting trend, thus squeezing out production space for crops like fruits, vegetables, and specialty coarse grains, thereby inhibiting the diversification of planting structures. Consequently, we raise some key questions: what is the impact of the PIIP on farmers' planting structure? Does the implementation of the PIIP strengthen a shift in planting structure toward staple grain crops? What is the underlying mechanism driving this effect? Do different types of farmers exhibit differentiated characteristics in their response to the agricultural insurance policy? Delving deeply into these questions holds significant theoretical value and practical importance for the scientific evaluation the effectiveness of the PIIP, the optimization of its institutional design, and the advancement of high-quality agricultural development in China.

The literature relevant to this study can be divided into two parts: first, research on the impact of policy-based agricultural insurance on agricultural production. A substantial body of research focuses on the policy's direct incentivizing effect on crop planting area (Xu and Liao, 2014; Hou and Wang, 2025). For instance, research targeting the US Corn Belt demonstrated that a 30% reduction in farmers' premium contributions significantly increased maize planting area by 0.28% (Goodwin et al., 2004). Yu et al. (2018) likewise confirmed that policy-based agricultural insurance exerts a positive influence on crop planting area. Specifically, a 10% increase in premium subsidies per unit led to a 0.43% expansion in crop planting area. While incentivising farmers to expand their planting scale, policy-based agricultural insurance also promotes the growth and stabilization of farm household income. Research by Fadhliani et al. (2019) in Indonesia showed that increases in rice insurance coverage and subsidy rates significantly raise the income levels of rice farmers. Utilizing farm data from France and Italy, Enjolras et al. (2014) found that crop insurance effectively reduces income volatility, functioning as an income stabilizer. Participation in insurance also leads to a significant improvement in farmers' wealth levels (Giné et al., 2008). Beyond the economic dimension, scholars have also examined the environmental implications of agricultural insurance policies. Niu et al. (2022) using provincial panel data from China, found that policy-based agricultural insurance exacerbates agricultural non-point source pollution. However, research by Xiao et al. (2024) on full-cost insurance policy reached the opposite conclusion, finding that full-cost insurance prompted a 21.761% reduction in fertilizer application intensity. Furthermore, research by ? revealed the complexity of these effects. They reported that crop insurance had no statistically significant effect on overall fertilizer input in China, but its specific impact varied by farm scale: participation prompted larger-scale farms to moderately reduce fertilizer input, while having no significant effect on smallholder farmers.

However, the impact effects of agricultural insurance policies extend far beyond expanding acreage, increasing farm incomes, or generating environmental externalities; their deeper impacts lie in reshaping the planting structure of farmers. Shi et al. (2020) find that the Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) not only increases acreage, yields, and inputs for specialty crops but also incentivises farmers to adopt riskier production modes. Cole et al. (2017) confirm this by stating that the risk protection mechanism provided by insurance induces farmers to shift from traditional low-risk crops to higher-return but riskier cash crops. Early research by Turvey (1992) similarly points out that agricultural insurance prompts a shift in planting structure toward higher-risk crops. It is worth noting that the direction and intensity of insurance's effect on farmers' planting structure are not fixed, they are subject to complex influences including individual farmer characteristics and insurance policy design. For example, analysis by Adkins et al. (2020) of the “Prevented Planting” provision in US crop insurance demonstrates that risk-averse farmers exhibit a stronger preference for the fully compensated prevented planting option. When compensation levels are reduced or become inadequate, farmers may abandon planting altogether. In addition, farmers' own experience of receiving payouts, or that of members of their social networks, significantly increases their willingness to participate in insurance and drives their planting structure toward higher-risk crops Karlan et al., (2014). Focusing on the Chinese context, scholars have also paid attention to the impact of agricultural insurance on farmers' planting structures. For instance, (Chai and Zhang 2023), based on a 2018 survey of farmers in Inner Mongolia, China, found that farmers' insurance participation inhibited specialized planting behavior, and that there were complementary effects between agriculture insurance and diversified planting structure. Conversely, Cai (2016), using panel data from farm households in Jiangxi Province, China, found that the introduction of insurance increased the planted area of insured crops by 20% and reduced production diversity. In recent years, as China's food security strategy has intensified, studies have begun to focus on the effect of new agricultural insurance policies (such as full-cost insurance and planting income insurance) on promoting ‘grain-oriented' planting structure. Jiang et al. (2022) found that the new agricultural insurance policy significantly increased the total area planted with grain, promoting this structural shift. Yuan and Xu (2024) further clarified that the new policy primarily influences planting structure by enhancing the level of mechanization, and this effect is more pronounced in lower-risk regions.

In summary, the established literature has systematically revealed the complex effects of policy-based agricultural insurance on agricultural production, yielding substantial insights. However, there are still the following research deficiencies that need to be examined urgently. Firstly, most studies still focus on the income-generating effect, sown-area expansion, and environmental impacts of insurance policies, relatively neglecting the examination of new policy instruments with comprehensive risk protection functions, such as PIIP on crop planting structure. Secondly, the existing research on new insurance policy and planting structure mostly examines the trend of “grain-oriented” or “non-grain-oriented”, “specialization” or “diversification” of policy from the macro level, which fails to precisely identify the policy's impact on internal restructuring within the three major staple food crops. In addition, although the mechanistic analyses acknowledge mediating factors like agricultural machinery, there is a distinct lack of mechanism testing grounded in micro-level farmer behavior and household operation characteristics. At the same time, the influence of insurance policies on farmers' planting structure choices exhibits contextual heterogeneity, profoundly shaped by individual farmer attributes and their specific operating environments. However, prevailing heterogeneity analyses predominantly concentrate on regional dimensions, overlooking critical variations arising from institutional factors (such as land tenure certification) and household endowment constraints (such as labor limitations). Finally, related studies mostly rely on macro data, which have the shortcomings of insufficient granularity in mechanism identification. To address the above research gaps, this study leverages data from the China Land Economy Survey (CLES) for 2020 and 2022, and adopts a DID model, focusing on China's now vigorously promoted planting income insurance policy, to empirically test the effect of the policy's implementation on the planting structure towards staple grain crops. To provide micro-empirical evidence for China to optimize the design of its agricultural insurance policy and to more accurately serve the national food security strategy.

2 Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses

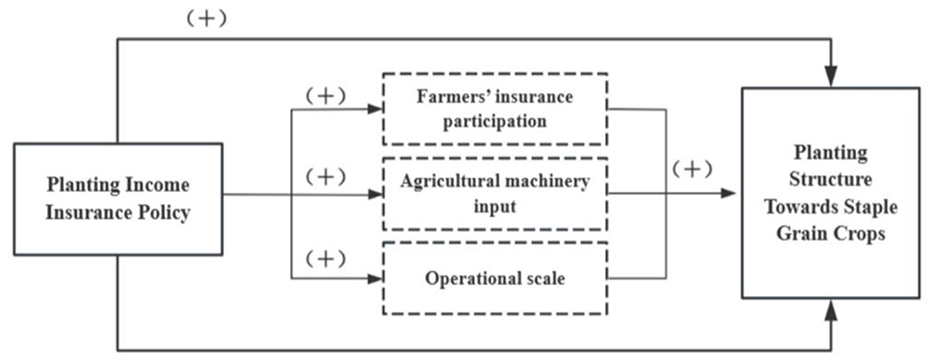

2.1 Planting income insurance policy and planting structure

Agricultural production confronts substantial production and market risks Cai and Su, (2020). Functioning as a crucial risk management instrument, agricultural insurance policies influence farmers' planting decisions, thereby ultimately shaping crop selection. The novel policy mechanism of crop income insurance incorporates a distinct institutional design characterized by focus on staple crops, substantial premium subsidies, and core functions mitigating both yield volatility and price fluctuations while safeguarding expected farm income. This mechanism may systematically reshape agricultural planting structures.

First, regarding insurance subsidy intensity, this scheme specifically targets rice, maize, and wheat, and operates with substantial government premium subsidies (such as Jiangsu Province provides a 90% subsidy). This establishes a significant institutional cost advantage relative to cash crops. Such asymmetric policy intervention effectively reduces the relative production costs and entry barriers for staple cultivation, thereby channeling production factors toward these crops. Second, in terms of risk management, planting income insurance covers both yield and price volatility (Jiang et al., 2024). Consequently, it substantially reduces downside risks to expected returns from staple crop planting. Even when farmers face natural disasters or market downturns, insurance payouts provide an effective income floor, stabilizing earnings around risk-adjusted expected values. This improvement in the stability and certainty of expected returns has significantly reduced the perceived risk of staple grain cultivation, satisfying the preferences of risk-averse farmers. Third, concerning risk-adjusted comparative returns, farmers' decision to switch to cash crops is motivated by high expected returns, but growing cash crops also entails higher operational risks. Given that policy-backed staple planting income insurance provides robust institutional safeguards, while equivalent risk-sharing mechanisms are absent for cash crops, the minimum reservation return threshold for staple production becomes significantly elevated. This differential enhances the relative attractiveness of staple crops, thereby profoundly reshaping farmers' planting choices within their risk-return trade-offs. Based on the above analyses, we propose hypothesis 1.

H1: PIIP can lead to a ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure.

2.2 Planting income insurance policy, farmers' insurance participation, and planting structure

The prerequisite for PIIP to drive farmers toward a ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure lies in its ability to significantly encourage farmers to actively participate in the insurance programme. Farmers' participation in insurance programmes depends on their premium affordability (Santeramo et al., 2016). The greater the government's subsidy for insurance premiums, the stronger farmers' willingness to participate (Goodwin and Smith, 2013; Lyu and Barré, 2017). In China, PIIP, as a high-subsidy policy, has significantly reduced farmers' actual premium expenditures, enabling them to manage future major income risks effectively at a small and certain cost (Azzam et al., 2021). This has significantly reduced farmers' perception of insurance costs, enhanced the expected stability of returns from insured crops, and thus positively incentivised farmers to participate in insurance (Wang et al., 2011). After farmers participate in insurance, based on the institutional design and policy orientation of PIIP, there is a tendency toward ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure. On the one hand, the core function of agricultural insurance lies in transferring and mitigating production risks associated with the three major staple crops, thereby stabilizing income expectations. When farmers' income projections are secure, they are more likely to secure financial backing from banks and other institutions for staple crop cultivation, enabling economies of scale. For banks, planting projects backed by PIIP carry lower risk profiles. Moreover, these three staple crops constitute strategic national commodities. Although prices fluctuate, they are often underpinned by policies such as minimum purchase prices, resulting in a relatively stable market. Income insurance provides a basic safety net for these staple commodities. With the assurance that their earnings from growing staple grains are guaranteed at the base level with unlimited upside potential, farmers are more inclined to commit substantial land, capital, and labor resources to staple grain production. Consequently, farmers' cultivation ratios for the three staple crops increase (Goodwin et al., 2004). Therefore, we propose hypothesis 2.

H2: PIIP promotes the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure by boosting farmers' insurance participation.

2.3 Planting income insurance policy, agricultural machinery input, and planting structure

Accelerated urbanization has intensified the transfer of rural labor to non-agricultural sectors, resulting in agricultural production confronting labor scarcity and persistently rising costs (Wu et al., 2021). Under the constraints of agricultural production seasonality and farming schedules, the continuous increase in labor expenses, combined with efficiency gains from agricultural mechanization, jointly drives farmers to adopt machinery as a labor substitute for cost minimization. This generates significant demand for mechanized farming services. PIIP have effectively reduced the uncertainty and risk premiums faced by farmers in making productive investments by stabilizing income expectations, thereby enhancing farmers' confidence in investing. Under the premise of effective income risk protection, farmers are more motivated to optimize agricultural production by purchasing agricultural machinery or agricultural machinery services (Fu et al., 2024; Hou and Wang, 2025). Against the backdrop of released agricultural machinery operation demand, since staple crops have a more complete agricultural machinery category system, a more mature agricultural machinery service market, and highly standardized production protocols in key cultivation stages that facilitate mechanization and specialized division of labor compared to cash crops, this further reinforces farmers' preference for staple grain crops production and drives the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure. Thus, we propose hypothesis 3.

H3: PIIP promotes the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure by incentivising farmers' agricultural machinery input.

2.4 Planting income insurance policy, operational scale, and planting structure

Expanding the scale of operations helps reduce unit production costs, improve the efficiency of factor utilization, and thereby increase farmers' expected income (Yin et al., 2024). However, expanding the scale of operations also means higher production risks. As an effective risk-pooling mechanism, PIIP incentivises farmers to expand land operations for economies of scale by mitigating scale-related production risks (Fang et al., 2021). First, high premium subsidies significantly reduce farmers' insurance costs and the threshold for scale operations, enabling farmers to expand their operational scale through land transfers to achieve scale benefits. Second, according to risk aversion theory, when expected returns are similar, farmers tend to choose lower-risk options. PIIP effectively stabilizes farmers' expected returns by diversifying the risks of large-scale production. Additionally, this risk protection mechanism synergises with existing grain support policies in China, such as the Agricultural Support and Protection Subsidy (Fan et al., 2023), the Rice Minimum Purchase Price policy, and the Corn-Soybean Producer Subsidy (Chen and Cheng, 2025), collectively enhancing farmers' confidence in engaging in large-scale production. Furthermore, large-scale operators may possess superior bargaining leverage and information acquisition capabilities during claims settlement (Fang et al., 2021). This advantage further reduces perceived risk costs, strengthening scale-enlargement incentives. As scale increases, farmers face intensified labor constraints. Given the persistent rise in labor costs and off-farm employment opportunities, mechanization becomes the critical solution for sustaining scaled operations (Zou et al., 2024). Within this context, China's staple crops demonstrate greater mechanization feasibility owing to their mature machinery systems, lower operational costs, and higher standardization. Consequently, this further reinforces the production preferences of scaled operators toward staple grain crops. As a result, we propose hypothesis 4.

H4: PIIP promotes the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure by incentivising farmers' operational scale expansion.

Figure 1 illustrates the mechanism through which PIIP influences farmers' planting structures.

3 Material and methods

3.1 Data sources

The data sources for this paper are divided into two main sections. First, the policy pilot data. The data of planting income insurance pilot area and pilot time applied in this paper research come from Jiangsu Province Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Second, micro-farming household data. In this paper, the individual-level, household-level, and village-level data of farm households come from CLES data conducted by Nanjing Agricultural University. The database covers more than 2,000 farm households in 13 prefectural-level cities in Jiangsu Province, and the questionnaire covers land market, agricultural production, and other aspects, which can effectively reflect the changes in farm household insurance participation and farm household planting structure. This paper applies the 2020 and 2022 CLES data to conduct baseline regression analysis, mechanism of action test, heterogeneity analysis, and robustness test. Before the empirical analyses, this paper first processed the survey samples and screened out the variables required for this study according to the research content needs; secondly, the samples with missing key information and abnormalities were excluded, and finally, 2,360 valid samples were obtained.

3.2 Model setting

3.2.1 Benchmark model

In this paper, we use the quasi-natural experiment of PIIP implemented to construct a DID model to identify the causal effect of the implementation of PIIP on the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure of farmers, and the specific model is set as follows.

In model (1), struit is the dependent variable, and reflects farmer i's adoption of the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure in year t. DIDit is the core explanatory variable, and its coefficient reflects the impact of the implementation of the PIIP. Specifically, DIDit takes the value of 1 if the PIIP is implemented in the region where farmer i is located and year t is the year of policy implementation and the following years, otherwise DIDittakes the value of 0. xit denotes the control variables that may affect the ‘staple grain-oriented' cropping structure of the farmer household, which includes the characteristics of variables at the head of the household level, the household level and the village level. θ0 is a constant term, θ1 and θ2 is the parameter to be estimated. εit is a random disturbance term.

3.2.2 Mechanism testing model

In order to further verify the intermediary role of farmers' insurance participation, agricultural machinery inputs and operational scale, this paper adopts the methodology proposed by (Wen and Ye 2014). Building upon the benchmark regression, it incorporates mediating variables to examine the causal mechanism, and the model is set as follows.

Among them, Mit is the mediating variable, including farmers' insurance participation (Insurance), farmers' agricultural machinery input (Mach) and operational scale (Scale), and other variables are the same as those in the baseline regression model (1). Equation (2) represents the total effect of the implementation of PIIP on the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure of farmers. Equation (3) shows the effect of the implementation of PIIP on the intermediary variables of farmers' insurance participation, agricultural machinery input, and operation scale. Equation (4) represents the direct effect of the implementation of planting income insurance policy on farmers' planting structure “staple grain-oriented” after adding intermediary variables. γ1 is the direct effect coefficient; σ1γ2 is the indirect effect coefficient, also known as the mediating effect coefficient. If θ1 is significant, and both σ1 and γ2 are significant, this indicates that the mediating effect is significant. If σ1γ2 and γ1 have the same sign, it means that the intermediary variable plays an intermediary role in the PIIP and farmers' planting structure “staple grain-oriented”; if σ1γ2 and γ1 have different signs, it means that the intermediary variable has a masking effect in it.

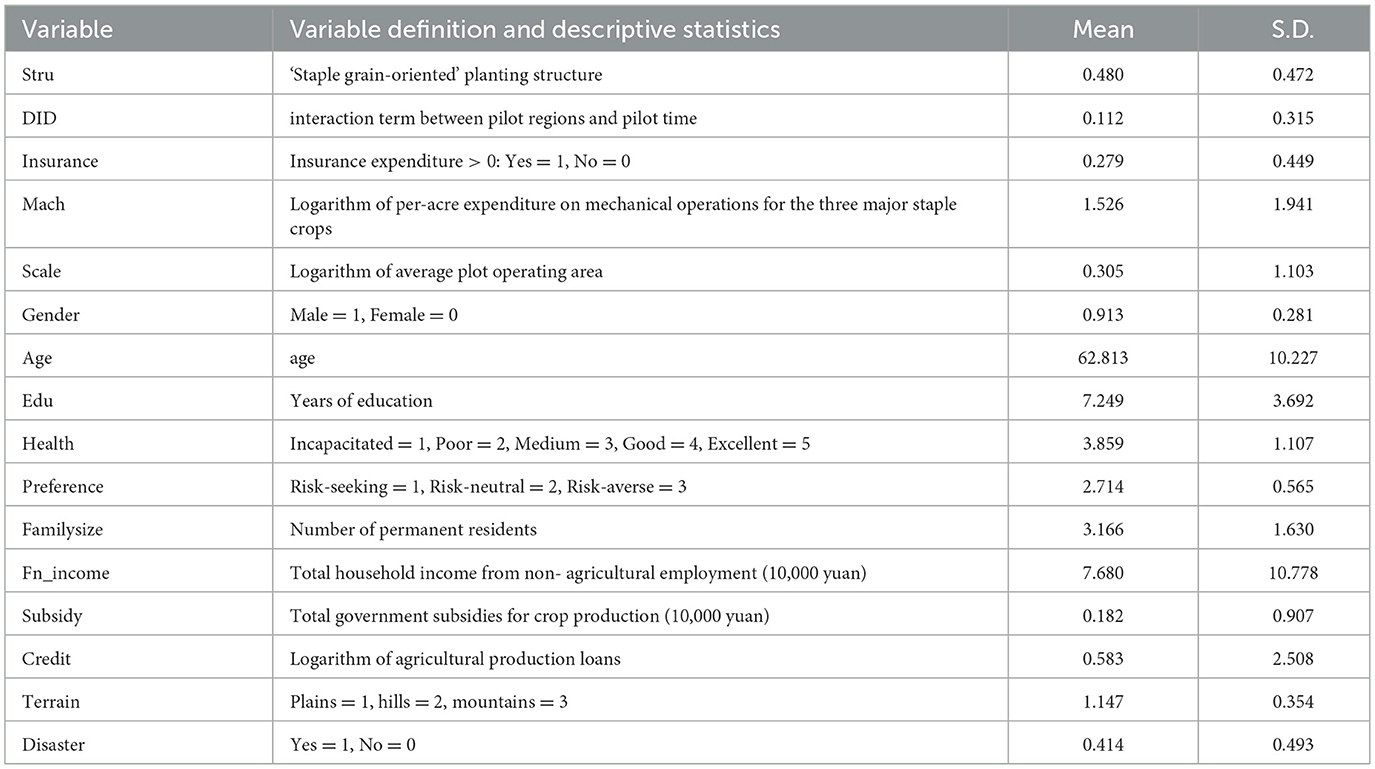

3.3 Variable selection and measurement

3.3.1 Explained variables

‘Staple grain-oriented' planting structure (stru). The three major staple crops defined in this paper include rice, wheat and maize, and the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure is expressed in terms of the proportion of the sown area of the three major staple crops in the total sown area of crops.

3.3.2 Core explanatory variables

The implementation of the PIIP (DID) is represented by the interaction term between pilot regions and pilot time for PIIP. This term takes the value of 1 if the farm household i is located in an area where the PIIP is implemented and the year t is the year of implementation and later years, otherwise it takes the value of 0.

3.3.3 Mediating variables

In order to test whether planting income insurance affects farmers' planting structure by promoting farmers' insurance participation, increasing farm machinery inputs, and improving farmers' operation scale, this paper sets three mediating variables, namely insurance participation (Insurance), farm machinery inputs (Mach), and operation scale (Scale). Among them, the insurance participation variable draws on Chai and Zhang's (2023) study and chooses whether farmers purchase agricultural insurance as the variable under examination. The agricultural insurance variable is assigned a value of 1 if the amount of agricultural insurance expenditure of the farm household is greater than 0, otherwise it is assigned a value of 0. The farm machinery input variable, drawing on Xu et al. (2024), is expressed as the logarithm of the average mu of farm machinery operating expenditure of the three major staple crops. The scale of operation variable, drawing on Li et al. (2025) is expressed using the average plot operating area, which is logarithmized in this paper.

3.3.4 Control variables

Farm household planting structure may be affected by household head characteristics, family characteristics and village characteristics, therefore, in order to reduce the estimation bias of the econometric model, this paper refers to the existing research (Li et al., 2024) and selects control variables that cover household head characteristics, family characteristics and village characteristics. Among them, the variables of household head characteristics include gender (gender), age (age), education level (edu), health status (health), and risk preference (preference). Household characteristics include household size (familysize), household non-agricultural income (fn_income), cultivation subsidy (subsidy), and agricultural production loan (credit). Village characteristics include village terrain (terrain), and village agricultural production disaster (disaster). Table 1 reports the measurement method and basic statistical characteristics of each variable.

4 Results

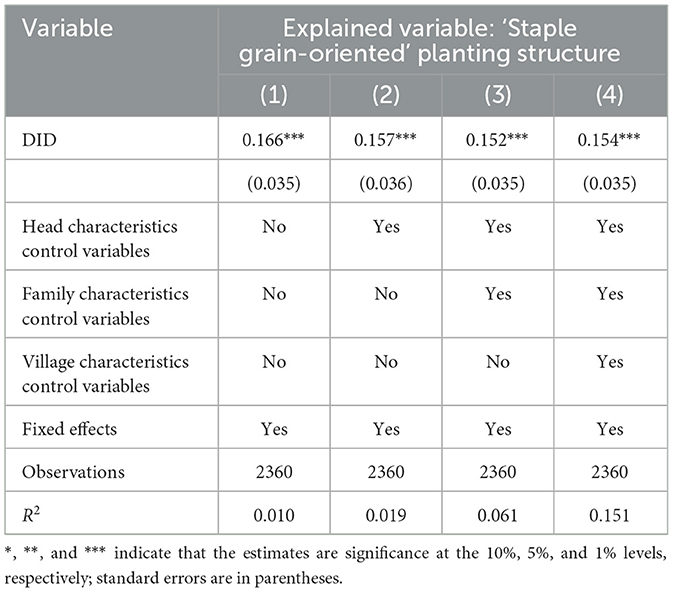

4.1 Benchmark regression

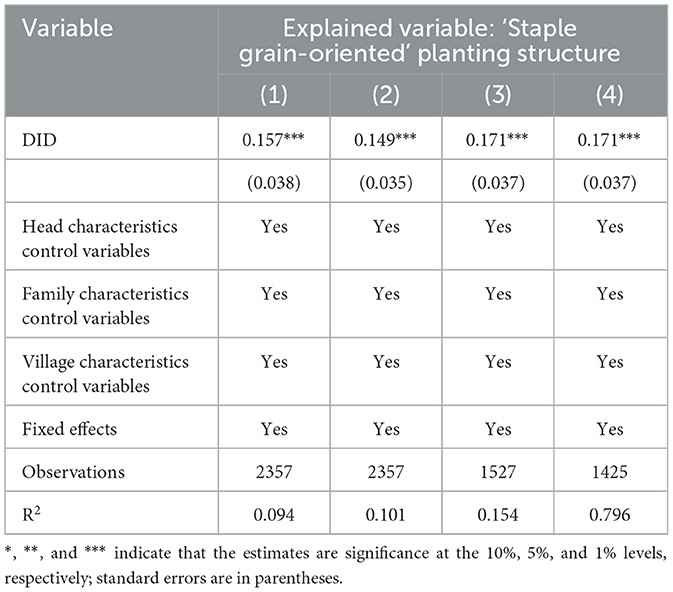

The results of the impact of PIIP on the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure is shown in Table 2. Model (1) shows the effect of PIIP on the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure of farmers when all control variables are not added, and model (2) (3) (4) shows the effect of PIIP on the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure when the control variables are added in turn. It can be found that whether or not the control variables are added, PIIP can significantly promote the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure. After controlling for other variables, the coefficient of influence of planting income insurance on the ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure is 0.154.

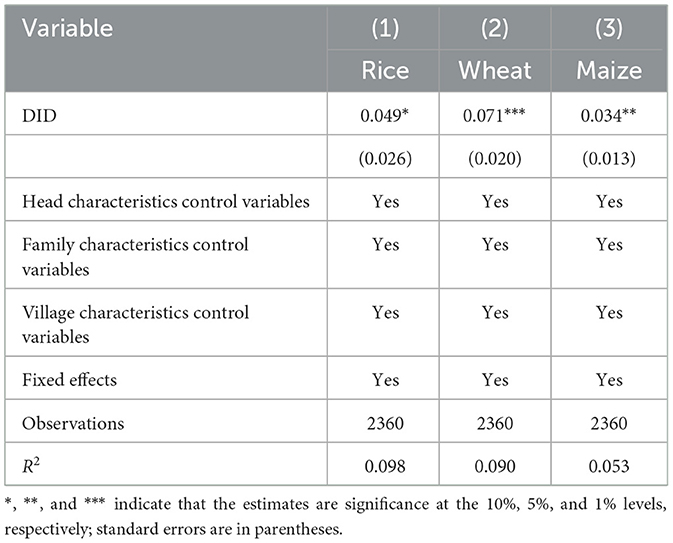

4.2 Regression analysis of staple crops by variety

Understanding the impact of PIIP on farmers' specific crop planting decisions is crucial to accurately optimize this policy. Therefore, this study breaks down the staple crops, and the regression results are shown in Table 3. Columns (1), (2), and (3) show the impact of PIIP on the proportion of rice, wheat, and maize planted by farmers, respectively. It can be seen that the implementation of PIIP significantly contributes to the proportion of rice, wheat and maize planted by farmers. Compared with areas where the policy has not been implemented, the proportion of rice, wheat, and maize cultivation among farmers in the implementation areas has increased by 4.9, 7.1, and 3.4 percentage points, respectively. This outcome stems from two primary factors: Firstly, as a policy instrument mitigating production risks for farmers, PIIP serves as a rational decision-making mechanism within risk mitigation frameworks by safeguarding expected income. Its core function lies in reducing income loss risks arising from fluctuations in agricultural product prices and yields. Following insurance enrolment, farmers' income expectations for rice, wheat, and maize stabilize. This risk protection mechanism objectively reinforces the cultivation of these three staple grain crops. Secondly, within the three staple crops themselves, Jiangsu Province has developed a mature rice and wheat cultivation system since the Ming and Qing dynasties, and continues to this day, becoming the province with the largest cultivation area under this model. The long history of farming has enabled farmers to accumulate deep experience and intellectual capital in rice and wheat cultivation, forming a significant comparative advantage in production. Under conditions where farmers' production risks are mitigated, they are more inclined to maintain and expand their investment in rice and wheat crops where they possess extensive experience and mature techniques. Consequently, PIIP exerts a slightly greater impact on rice and wheat than on maize.

4.3 Robust test

4.3.1 Placebo test

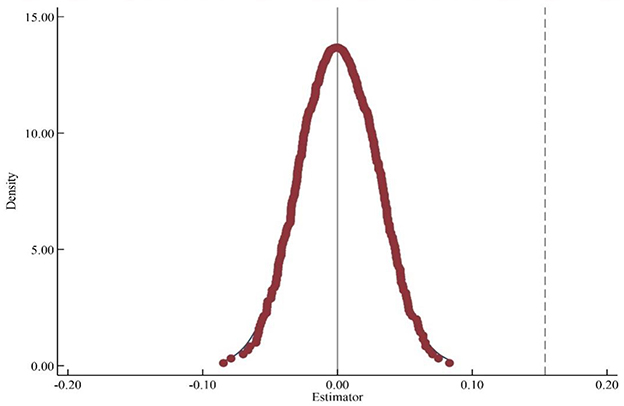

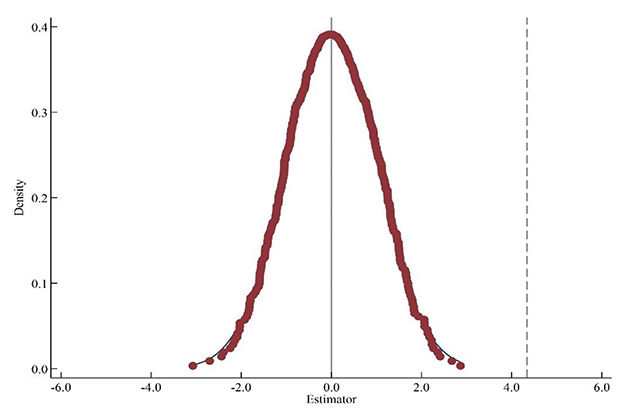

In order to further verify the real effect of PIIP implementation, this paper conducts a placebo test. Specifically, this paper randomly generates pseudo-DID terms based on the implementation of PIIP to randomize the shock of PIIP implementation on farmers' planting structure, based on which the model (1) is re-estimated, and this randomization process is repeated 500 times. Figures 2, 3 respectively show the regression coefficients and t-values for the effects of pseudo-policy implementation on the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure, with the vertical dashed line in Figure 2 being the true regression coefficient value and the vertical dashed line in Figure 3 being the true t-value. It can be seen that the regression coefficients and t-values of the pseudo-policy are distributed around 0 and approximately follow the normal distribution, while the estimated placebo coefficients are all smaller than the baseline regression results. This suggests that the “staple grain-oriented” cropping structure of farmers is caused by the implementation of PIIP, and there are no other random factors that affect the evaluation of PIIP, so the conclusions of this paper are reliable.

4.3.2 Replacement of explained variable measure

If farmer's ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure indicator is equal to or greater than 0.5, it signifies a staple crop planting preference; thus, the planting structure is defined as ‘staple grain-oriented' with the dependent variable coded as 1. Otherwise, it is defined as non-staple-oriented and coded as 0. The regression results are shown in column (1) of Table 4. It can be seen that after replacing the explanatory variable, the DID coefficient remains statistically significant and positive at the 1% level, which confirms that PIIP has promoted a shift towards ‘staple grain-oriented' planting structure.

4.3.3 Treatment of outliers

To mitigate the influence of outliers, a winsorisation procedure was applied to the continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The regression results following this treatment are presented in Column (2) of Table 4. The findings indicate that the implementation of the PIIP continues to have a statistically significant positive effect on the shift in farmers' planting structure toward staple grains, even after winsorising the continuous variables. This confirms that the baseline regression results are robust.

4.3.4 PSM-DID estimation

Although the DID model separates out the average treatment effect of the policy, there may still be a problem of selectivity bias because the PIIP is not strictly a quasi-natural experiment. Therefore, this paper further employs the PSM-DID method for robustness testing. Specifically, this paper takes the variables of household head characteristics, family characteristics and village characteristics as covariates, estimates the logit model for propensity score, and applies both caliper nearest-neighbor matching (1:1) and kernel density matching for propensity score matching, conducts a balanced test on the obtained data, and finally applies the DID model to estimate the impact of the implementation of PIIP on the planting structure of farm households. The regression results are presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 4. The results demonstrate that, after correcting for systematic bias arising from sample selection, the estimated coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive, which attests the reliability of the baseline regression conclusions.

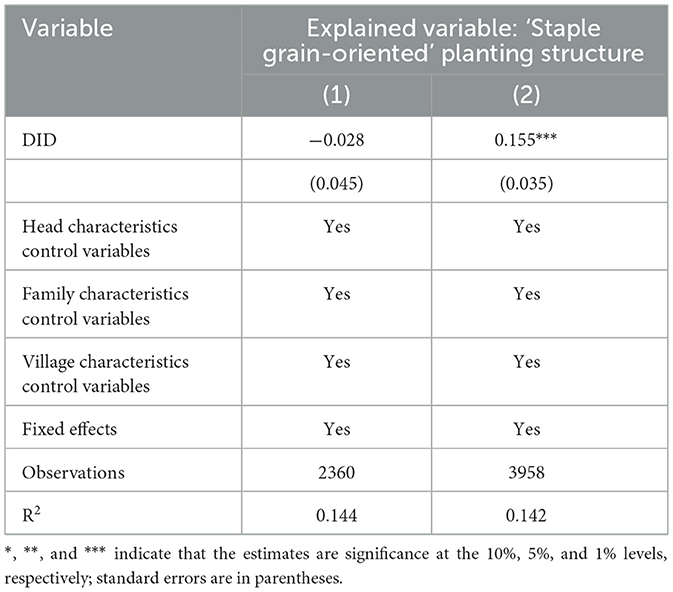

4.3.5 Fictitious policy shocks

To further examine whether differences in planting patterns between the intervention and control groups stem from the PIIP, this study adopts the methodology of Yan et al. (2024), employing a fictitious pilot vs. non-pilot region approach. Specifically, the districts of Lishui, Gaochun, Taicang, Kunshan, Ganyu, and Lianshui were hypothetically designated as pilot areas, with all other regions treated as non-pilot areas. Equation (1) was re-estimated to test the robustness of the baseline regression results. If the DID coefficient under this hypothetical policy shock is not statistically significant it indicates that, in the absence of the actual policy intervention, there is no systematic difference in trends between the treatment and control groups, thus supporting the robustness of the baseline findings. As shown in Column (1) of Table 5, the estimated coefficient for the hypothetical PIIP is not significant. This confirms that no systematic difference exists in the trends of crop structure changes between the treatment and control groups. Consequently, the sample selection in this study is random, and the research conclusions are reliable.

4.3.6 Extend the time window

This paper further employs an expanded time window approach to conduct robustness tests, incorporating CLES 2021 data into the research sample for regression analysis. The regression results are presented in Column (2) of Table 5. It can be observed that even after broadening the sample time window, PIIP remains statistically significant at the 1% level in promoting farmers' planting structure toward staple grain crops. This confirms the robustness of the study's conclusions.

4.4 Mechanism test

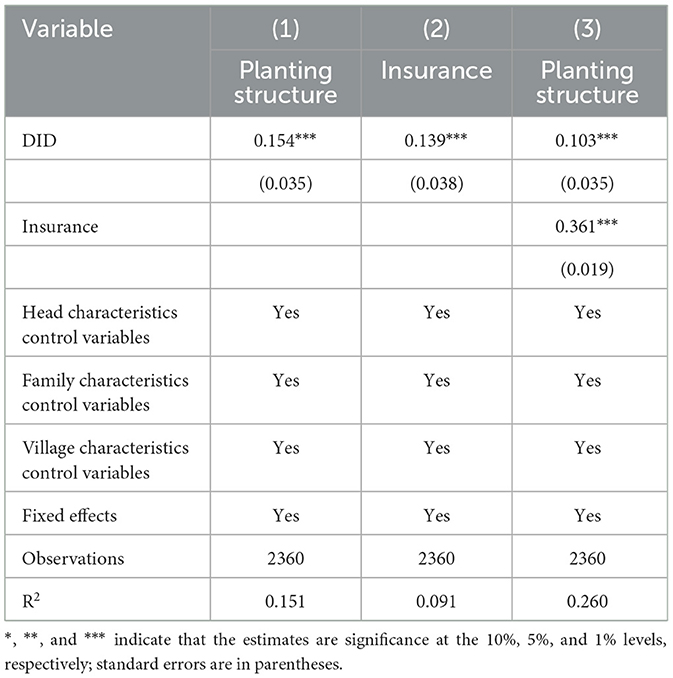

4.4.1 Intermediation tests of farmers' insurance participation

PIIP is an agricultural insurance whose insurance amount reflects the prices and yields of agricultural products, whose insurance targets cover the three major grain crops, and whose level of protection covers the cultivation income of relevant agricultural products. China's financial subsidies for planting income insurance premiums, based on reducing the cost of insurance purchased by farmers, but also able to reduce the income loss caused by fluctuations in prices and yields of staple crops, and stabilize the income expectations of farmers, therefore, this paper expects that, in the context of the implementation of the PIIP, the demand for farmers to participate in the insurance to enhance and cause the farming structure of the “staple grain-oriented” adjustment.

Table 6 reports the estimation results that the implementation of the PIIP promotes farmers' insurance participation and thus the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure. The coefficients of DID in columns (1) and (3) show that the total and direct effects of the implementation of PIIP on the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure are 0.154 and 0.103, respectively, and the coefficients of direct effect are smaller than the coefficients of total effect, which indicates that the insurance participation of farmers is a major factor in the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure through the implementation of PIIP. This indicates that the insurance participation of farmers plays a mediating role in the process of the influence of PIIP on farmers' planting structure of “staple grain-oriented”. The empirical results are consistent with expectations, and the hypothesis of this paper has been further verified.

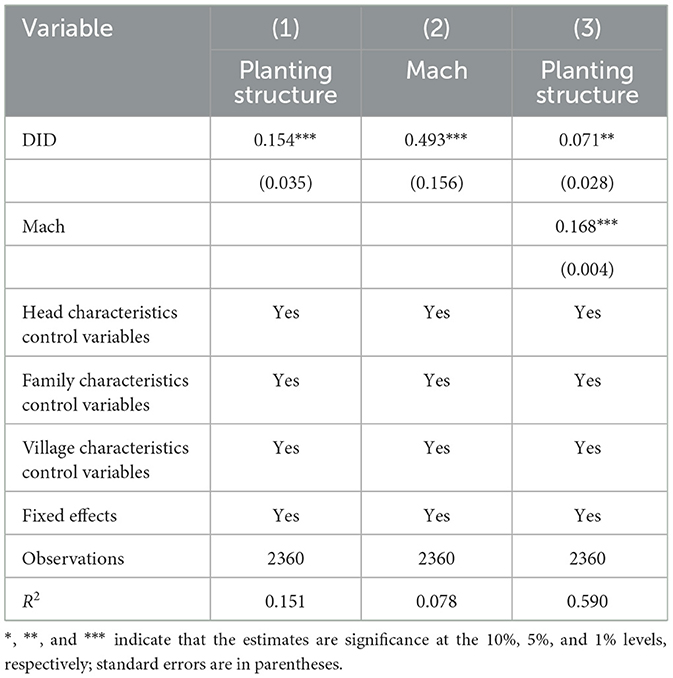

4.4.2 Intermediation tests for agricultural machinery inputs

Against the background of the current transfer of a large number of high-quality rural laborers to the non-agricultural sector, coupled with the strong seasonality of agricultural production and the continuing rise in the price of agricultural labor factors and the cost of hiring labor, the use of machinery to replace labor has become a rational choice for farmers to reduce production costs. The implementation of the planting income insurance policy stimulates the application and investment of agricultural machinery by stabilizing farmers' income expectations and prompting a change in farmers' risk attitude.

Table 7 reports the regression results of whether the implementation of PIIP can promote the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure by promoting the input of agricultural machinery. From the coefficients of DID in column (1) and column (3), it can be found that the total effect and direct effect of the implementation of PIIP on “staple grain-oriented” planting structure are 0.154 and 0.071, respectively, and at the same time, the coefficients of DID in column (2) and the coefficients of Mach in column (3) are significantly positive, which indicates that farm machinery inputs play a mediating role in the process of the impact of the PIIP on the “staple grain-oriented” cropping structure. This suggests that the implementation of PIIP can indeed cause the “staple grain-oriented” cropping structure by promoting farmers' farm machinery inputs, which is consistent with the findings of Yuan and Xu (2024).

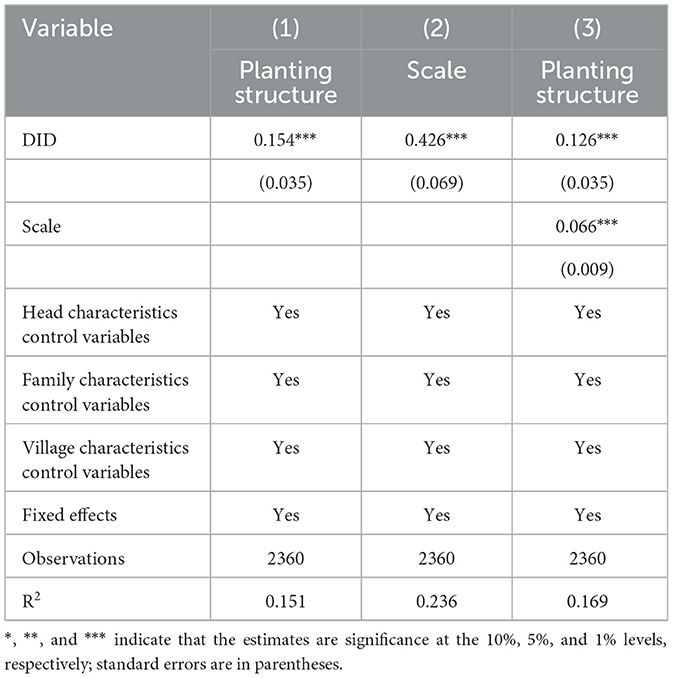

4.4.3 Intermediation tests for operational scale

The expansion of the scale of operation, on the one hand, helps to reduce the cost of factor inputs and realize the full utilization of agricultural factors of production, leading to an increase in the expected returns of farmers. On the other hand, the expansion of the scale of operation also means that farmers face greater production risks, the larger the scale of operation, the higher the initial input costs of farmers. PIIP, as a policy agricultural insurance, has a high level of protection, and farmers will further expand their scale of operation after they have transferred the risk of income fluctuation by participating in the insurance.

Table 8 reports the regression results of whether the implementation of the PIIP promotes the “staple grain-oriented” cropping structure by increasing their operational scale. The results in column (1) show that the implementation of PIIP can significantly increase the “staple grain-oriented” crop cultivation of farmers, with a total effect of 0.154. The regression coefficient of DID in column (2) is 0.426, which indicates that the implementation of PIIP can increase the scale of operation of farmers. The coefficient of DID in column (3) is 0.126, indicating that the direct effect of the implementation of the PIIP on the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure is 0.126, but its coefficient is smaller than the coefficient of DID in column (1), which means that the size of the farm household's operation plays a mediating role between the PIIP and the farm household's “staple grain-oriented” planting structure.

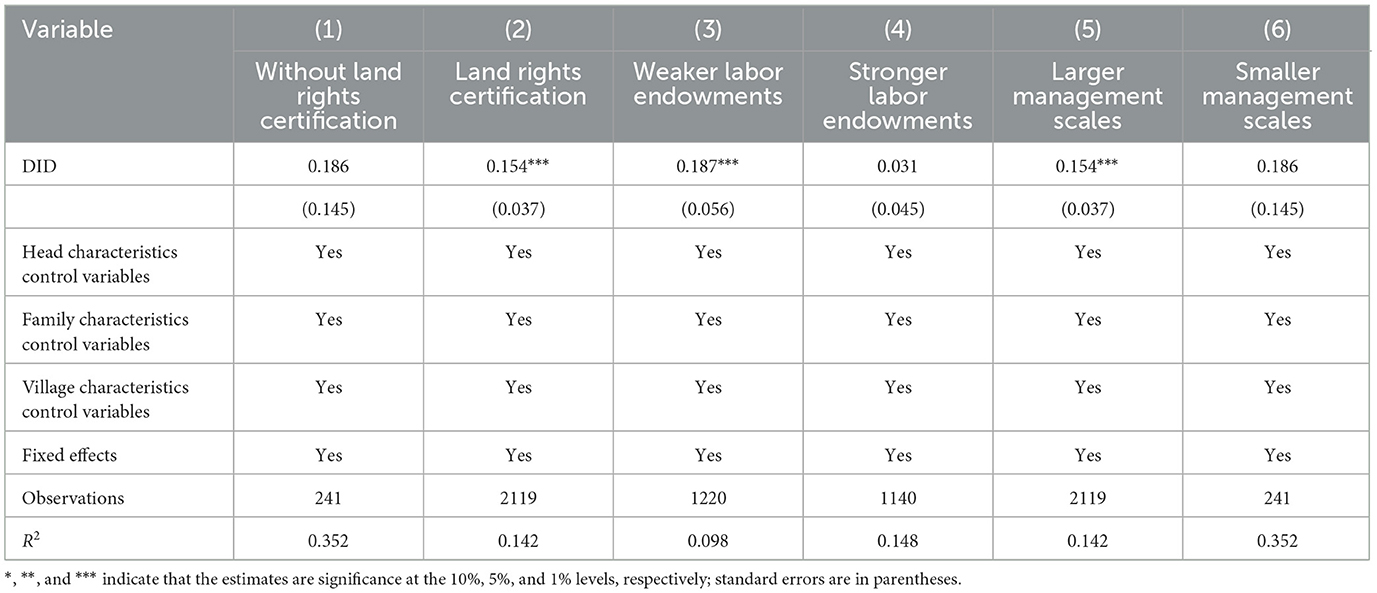

4.5 Heterogeneity analysis

4.5.1 Heterogeneity analyses based on the situation of land rights certification

Based on the situation of land rights certification, the sample is divided into farming households without land rights certification and farming households with land rights certification, and the specific regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9. It can be seen that the PIIP significantly contributes to the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure of farmland certified farmers, while the effect on farmland uncertified farmers is not significant. The reason for this may be that for farmers with certified land rights, the stable property structure established through legal empowerment is paramount. This stability significantly enhances farmers' willingness to cultivate staple grain crops. Specifically, on one hand, clearly defined property rights reduce operational risks. The precise demarcation of contractual and management rights substantially mitigates potential land disputes. On the other hand, the planting income insurance scheme stabilizes income expectations for staple grain crops, providing risk mitigation that incentivises farmers to expand operational scale and increase agricultural machinery investment, thereby shifting cultivation patterns toward staple crops. Underpinned by secure property rights, these mechanisms interact synergistically to form a dual protection system of “property rights protection and risk control”, driving staple crop cultivation. Conversely, for farmers who have not confirmed their rights and issued certificates, the ambiguity of land property rights has exacerbated the risk of factor allocation. The systemic risk derived from the uncertainty of ownership is difficult to fully cover by the current agricultural insurance policy, resulting in farmers facing the threat of sunk costs of factor inputs. Based on risk-return considerations, farmers often tend to use part of their land to grow cash crops, and diversify cultivation to spread operational risks. Therefore, PIIP can significantly promote the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure of farmland households with certified rights to farmland, while its impact on the “staple grain-oriented” of farmland households without certified rights to farmland is not significant.

4.5.2 Heterogeneity analyses based on agricultural labor endowment

Based on the agricultural labor endowment of farm households, the sample was divided into farm households with weaker agricultural labor endowment and farm households with stronger agricultural labor endowment. If the number of agricultural laborers in a farm household is smaller than the average number of agricultural labor inputs in a household in the sample, it is defined as a farm household with a weaker agricultural labor endowment, otherwise, it is defined as a farm household with a stronger agricultural labor endowment. The specific regression results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 9. It can be found that, PIIP can significantly promote the shift toward staple crops in the cropping patterns of farming households with weaker agricultural labor endowments, while having no significant impact on households with stronger agricultural labor endowments. The reason may be that, under the background of increasing labor rigidity constraints and rising labor opportunity costs, “staple grain-oriented” is the inevitable result of farmers' rational choice. Compared with cash crops, staple crops have more significant mechanization advantages and standardized production characteristics, and are less dependent on labor. Therefore, after participating in the insurance, farmers with weaker labor endowment are more inclined to choose staple crops with high degree of mechanization based on their labor input limitations and production feasibility, so as to reduce labor intensity and ease the pressure of labor costs. On the other hand, farmers with stronger labor endowment have more space to choose crops because of their relatively abundant family labor. Under the conditions of higher mechanization of staple crops, they can arrange part of their labor force to work on staple crops, while devoting the remaining labor force to other cash crops in pursuit of higher returns.

4.5.3 Heterogeneity analyses based on farmland operation scale

Based on the scale of farmland management within household farming operations, the sample was categorized into households with larger farmland management scales and those with smaller farmland management scales. Households whose farmland management scale fell below the average household farmland management scale within the sample were defined as having a smaller farmland management scale; otherwise, they were defined as having a larger farmland management scale. The regression results are presented in columns (5) and (6) of Table 9. It can be observed that the PIIP significantly promotes the shift toward staple crops in the cropping patterns of larger-scale farming households, while its impact on the cropping patterns of smaller-scale farming households is insignificant. This may be because, for larger-scale farming households, agricultural income constitutes the primary component of their household income, thereby heightening their demand for income stability. By safeguarding the expected returns on staple crops, PIIP effectively mitigates income uncertainty arising from yield or price fluctuations. This incentivises farmers to expand staple crop cultivation, driving crop structures toward concentration in the three major staple crops. Furthermore, larger-scale farming households possess distinct resource advantages in agricultural production: on the one hand, their scale grants bargaining power in purchasing agricultural inputs, enabling lower-cost acquisition of fertilizers, pesticides, and other inputs; on the other hand, large-scale cultivation facilitates the introduction and application of advanced agricultural machinery, thereby reducing unit area machinery costs and further enhancing the profitability and viability of staple crop cultivation. In contrast, farmers with smaller cultivated land holdings typically rely on non-agricultural employment as their primary income source, with agriculture serving more as a supplementary livelihood and household subsistence function. Consequently, their willingness to pay for planting income insurance and perceived utility of such schemes are lower, making it difficult for insurance policies to effectively influence their planting decisions. Concurrently, given the higher market value of cash crops like fruit and vegetables, smallholders often favor crop diversification strategies to reduce household food expenditure and meet varied consumption needs, rather than expanding staple crop proportions through monoculture expansion.

5 Conclusions and policy implications

5.1 Conclusion and discussion

As an important part of China's agricultural support and protection policy system, PIIP plays an important role in ensuring national food security. Based on the data from the China Land Economy Survey (CLES) for 2020 and 2022, this paper examines the impact of PIIP on the “staple grain” cultivation planting structure of farmers by using a DID model with the help of a quasi-natural experiment of PIIP.

The empirical results show that, first, the PIIP can promote the “staple grain-oriented” planting structure. Although existing literature has not directly examined this policy's staple grain-oriented effect, Jiang et al. (2022) found that new agricultural insurance policies stimulate grain crop cultivation and increase planting proportions, aligning with this study's conclusions. Second, our research identifies that the policy significantly increases the planting proportions of for rice, wheat and maize, with the impact on rice and wheat planting proportions being considerably greater than that on maize. This outcome diverges from Liu and Wu (2024), who found stronger incentive effects from policy-based agricultural insurance on maize production than on rice or wheat. A potential reason may lie in the fact that this study's sample focused on Jiangsu Province. This region has developed a mature rice-wheat cropping system since the Ming and Qing dynasties, accumulating extensive experience and technical capital, and possessing significant comparative production advantages. This may have led to the consolidation of its traditional rice-wheat cropping structure. Third, policy implementation drives the shift toward staple grain production by incentivizing insurance participation, increasing agricultural machinery investment, and expanding operational scale. This mechanism analysis aligns with extant research. For instance, Yuan and Xu (2024) confirm that insurance policies influence planting structures through machinery adoption, while Goodwin et al. (2004) note that policy-based agricultural insurance facilitates operational scale expansion. Fourth, heterogeneity analysis based on land tenure certification status, agricultural labor endowment and farmland management scale reveals more pronounced policy effects among households with formalized land rights, those with constrained agricultural labor resources, and those operating at a larger scale.

5.2 Policy implications

Understanding the impact of PIIP on farmers' transition to a “staple grain-oriented” planting structure carries significant policy implications. First, to consolidate the policy's role in guaranteeing national food security, especially for staple crops, it is essential to continuously raise the premium subsidy standard for staple grain crops under the PIIP, and to encourage farmers to participate in agricultural insurance and induce them to plant staple grain crops by raising the level of premium subsidies. Differentiated premium subsidy standards should be implemented across staple crops, guiding farmers to optimize internal planting structures through targeted support mechanisms. Simultaneously, in order to prevent PIIP squeeze fruits, vegetables, specialty grains, and other crops of production space, and inhibit the diversification of planting structure, policymakers should appropriately expand agricultural insurance coverage and introduce new insurable commodities to accommodate diversified production needs. Second, mechanisms for agricultural land confirmation, registration, and transfer must be synergistically advanced to prevent underdeveloped land systems and transfer markets from undermining the stabilizing effect of insurance policies on staple grain production. This requires strengthening property rights protection over land contracting and management rights following certification, thereby stabilizing farmers' operational expectations, while curbing irrational land rent increases through enhanced market supervision, ultimately ensuring orderly land transfers safeguard staple crop operators' rights and interests. Finally, improve the agricultural machinery purchase subsidy policy and agricultural machinery service market. Efforts should be made to develop the agricultural machinery service market, optimize the agricultural machinery purchase subsidy policy, and promote its synergistic effect with the policy of agricultural insurance. By encouraging farmers to increase investment in agricultural machinery operations, in order to give play to the advantages of large-scale grain production as well as obtain the benefits of scale, effectively guarantee the stable supply of food.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. The micro-level household data can be found at: https://jiard.njau.edu.cn/. Further details of the data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

WL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YC: Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adkins, K., Boyer, C. N., Smith, S. A., Griffith, A. P., and Muhammad, A. (2020). Analyzing corn and cotton producers optimal prevented planting decision on moral hazard. Agron. J. 112, 2047–2057. doi: 10.1002/agj2.20173

Azzam, A., Walters, C., and Kaus, T. (2021). Does subsidized crop insurance affect farm industry structure? Lessons from the U.S. J. Policy Model. 43, 1167–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jpolmod.2021.06.003

Cai, J. (2016). The impact of insurance provision on household production and financial decisions. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 8, 44–88. doi: 10.1257/pol.20130371

Cai, J., and Su, L. (2020). Impact of agricultural scale management on farmers? willingness to purchase agricultural insurance. Res. Dev. 39, 121–125.

Chai, Z., and Zhang, X. (2023). The impact of agricultural insurance on planting structure adjustment—an empirical Study from Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Agriculture 14:41. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14010041

Chen, Y., and Cheng, M. (2025). The minimum purchase price policy in China and wheat production efficiency: a historical review, mechanisms of action, and policy implications. Front. Nutr. 12:1536002. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1536002

Cole, S., Giné, X., and Vickery, J. (2017). How does risk management influence production decisions? Evidence from a field experiment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 30, 1935–1970. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hhw080

Cui, X., and Zhong, Z. (2024). Climate change, cropland adjustments, and food security: Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 167:103245. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103245

Enjolras, G., Capitanio, F., Aubert, M., et al. (2014). Direct payments, crop insurance and the volatility of farm income. some evidence in France and in Italy[J]. New Medit 1, 31–40.

Fadhliani, Z., Luckstead, J., and Wailes, E. J. (2019). The impacts of multiperil crop insurance on Indonesian rice farmers and production. Agricult. Econ. 50, 15–26. doi: 10.1111/agec.12462

Fan, P., Mishra, A. K., Feng, S., Su, M., and Hirsch, S. (2023). The impact of China's new agricultural subsidy policy on grain crop acreage. Food Policy 118:102472. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2023.102472

Fang, L., Hu, R., Mao, H., and Chen, S. (2021). How crop insurance influences agricultural green total factor productivity: evidence from Chinese farmers. J. Clean. Prod. 321:128977. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128977

Food Security Information Network (FSIN) and Global Network Against Food Crises (GNAFC) (2025). Global Report on Food Crises 2025 September Update. FSIN/GNAC. doi: 10.71958/WFP131041

Fu, L. S., Qin, T., Li, G. Q., and Wang, S. G. (2024). Efficiency of agricultural insurance in facilitating modern agriculture development: from the perspective of production factor allocation. Sustainability 16:6223. doi: 10.3390/su16146223

Giné, X., Townsend, R., and Vickery, J. (2008). Patterns of rainfall insurance participation in rural India. World Bank Econ. Rev. 22, 539–566. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhn015

Goodwin, B. K., and Smith, V. H. (2013). What harm is done by subsidizing crop insurance? Am. J Agri. Econ. 95, 489–497. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aas092

Goodwin, B. K., Vandeveer, M. L., and Deal, J. L. (2004). An empirical analysis of acreage effects of participation in the federal crop insurance program. Am. J. Agri. Econ. 86, 1058–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.0002-9092.2004.00653.x

Haarsma, D., and Qiu, F. (2017). Assessing neighbor and population growth influences on agricultural land conversion. Appl. Spatial Anal. 10, 21–41. doi: 10.1007/s12061-015-9172-0

Hou, D., and Wang, X. (2025). How does agricultural insurance influence grain production scale? An income-mediated perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1524874. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1524874

Huang, K., Cao, S., Qing, C., Xu, D., and Liu, S. (2023). Does labour migration necessarily promote farmers' land transfer-in?-Empirical evidence from China's rural panel data. J. Rural Stud. 97, 534–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.12.027

Jiang, S., Fu, S., and Li, W. (2022). Can the agricultural insurance subsidy policy change the crop planting structure? evidences from Chinese quasi-natural experiments. Ins. Stud. 51–66. doi: 10.13497/j.cnki.is.2022.06.004

Jiang, S., Liu, X., and Jiang, S. (2024). Can China's staple grain agricultural insurance reform increase farmers' income?-Based on the protection level perspective. Ins. Stud. 38–52. doi: 10.13497/j.cnki.is.2024.11.004

Karlan, D., Osei, R., Osei-Akoto, I., and Udry, C. (2014). Agricultural decisions after relaxing credit and risk constraints. Q. J. Econ. 129, 597–652. doi: 10.1093/qje/qju002

Li, R., Chen, J., and Xu, D. (2024). The impact of agricultural socialized service on grain production: evidence from rural China. Agriculture 14:785. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14050785

Li, Y., He, J., Zheng, J., and Xu, D. (2025). How can continuous land transfers guarantee food security? A study from the perspectives of plot size. Appl. Econ. 57, 4426–4440. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2024.2360691

Liu, H., and Wu, C. (2024). The new agricultural insurance policies encourage grain production: logic, Problems and Path. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 45–53.

Long, M., Tan, R., Zhao, Y., Li, X., Zhou, C., and Zhang, D. (2025). The rice terrace abandonment and its challenge for food security in the rural villages of southern China. Habitat. Int. 160:103398. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2025.103398

Lyu, K., and Barré, T. J. (2017). Risk aversion in crop insurance program purchase decisions: Evidence from maize production areas in China. CAER 9, 62–80. doi: 10.1108/CAER-04-2015-0036

Niu, Z., Yi, F., and Chen, C. (2022). Agricultural insurance and agricultural fertilizer non-point source pollution: evidence from China's policy-based agricultural insurance pilot. Sustainability 14:2800. doi: 10.3390/su14052800

Santeramo, F. G., Goodwin, B. K., Adinolfi, F., and Capitanio, F. (2016). Farmer participation, entry and exit decisions in the Italian crop insurance programme. J. Agric. Econ. 67, 639–657. doi: 10.1111/1477-9552.12155

Shi, J., Wu, J., and Olen, B. (2020). Assessing effects of federal crop insurance supply on acreage and yield of specialty crops. Can. J. Agri. Econ. 68, 65–82. doi: 10.1111/cjag.12211

Turvey, C. G. (1992). An economic analysis of alternative farm revenue insurance policies. Can. J. Agricult. Econ. 40, 403–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7976.1992.tb03704.x

Wang, M., Shi, P., Ye, T., Liu, M., and Zhou, M. (2011). Agriculture insurance in China: history, experience, and lessons learned. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2, 10–22. doi: 10.1007/s13753-011-0007-6

Wen, Z., and Ye, B. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 22, 731–745. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00731

Wu, Z., Dang, J., Pang, Y., and Xu, W. (2021). Threshold effect or spatial spillover? The impact of agricultural mechanization on grain production. J. Appl. Econ. 24, 478–503. doi: 10.1080/15140326.2021.1968218

Xiao, Y., Yang, C., and Zhang, L. (2024). The impact of a full-cost insurance policy on fertilizer reduction and efficiency: the case of China. Agriculture 14:1598. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14091598

Xu, D., Liu, Y., Li, Y., Liu, S., and Liu, G. (2024). Effect of farmland scale on agricultural green production technology adoption: evidence from rice farmers in Jiangsu Province, China. Land Use Policy 147:107381. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2024.107381

Xu, J., and Liao, P. (2014). Crop insurance, premium subsidy and agricultural output. J. Integr. Agric. 13, 2537–2545. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60674-7

Yan, F., Yi, F., and Zhang, Q. (2024). The reducing effect of agricultural insurance on the use of chemical fertilizer: a re-examination fromthe perspective of dual constraints of credit and information. Chin. Rural Econ. 20–41. doi: 10.20077/j.cnki.11-1262/f.2024.10.002

Yin, G., You, Y., Han, X., and Chen, D. (2024). The effect of agricultural scale management on farmers' income from a dual-scale perspective: Evidence from rural China. Int. Rev. Econ. Fin. 94:103372. doi: 10.1016/j.iref.2024.05.051

Yu, J., Smith, A., and Sumner, D. A. (2018). Effects of crop insurance premium subsidies on crop acreage. Am. J. Agri. Econ. 100, 91–114. doi: 10.1093/ajae/aax058

Yuan, Y., and Xu, B. (2024). Can Agricultural insurance policy adjustments promote a ‘grain-oriented' planting structure?: measurement based on the expansion of the high-level agricultural insurance in China. Agriculture 14:708. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14050708

Zhao, Y., Zheng, R., Zheng, F., Zhong, K., Fu, J., Zhang, J., et al. (2023). Spatiotemporal distribution of agrometeorological disasters in China and its impact on grain yield under climate change. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 95:103823. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103823

Zhu, X., Li, C., and Zhou, H. (2022). Cost changes and technical efficiency of grain production in China against a background of rising factor prices. Sustainability 14:12852. doi: 10.3390/su141912852

Keywords: planting income insurance policy, PIIP, staple grain crops, planting structure, difference-in-differences (DID) model

Citation: Li W and Cai Y (2025) Can planting income insurance policy promote a shift in planting structure toward staple grain crops? Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1688835. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1688835

Received: 19 August 2025; Accepted: 30 October 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Bingnan Guo, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Zhihui Chai, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, ChinaAhmet Ali Koç, Akdeniz University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Li and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenqing Li, MTkyMDIzMDAxOEBzdHUubnVmZS5lZHUuY24=

Wenqing Li

Wenqing Li Yunkun Cai2

Yunkun Cai2