- 1Wildlife Conservation Society, New York, NY, United States

- 2WorldFish, Bayan Lepas, Malaysia

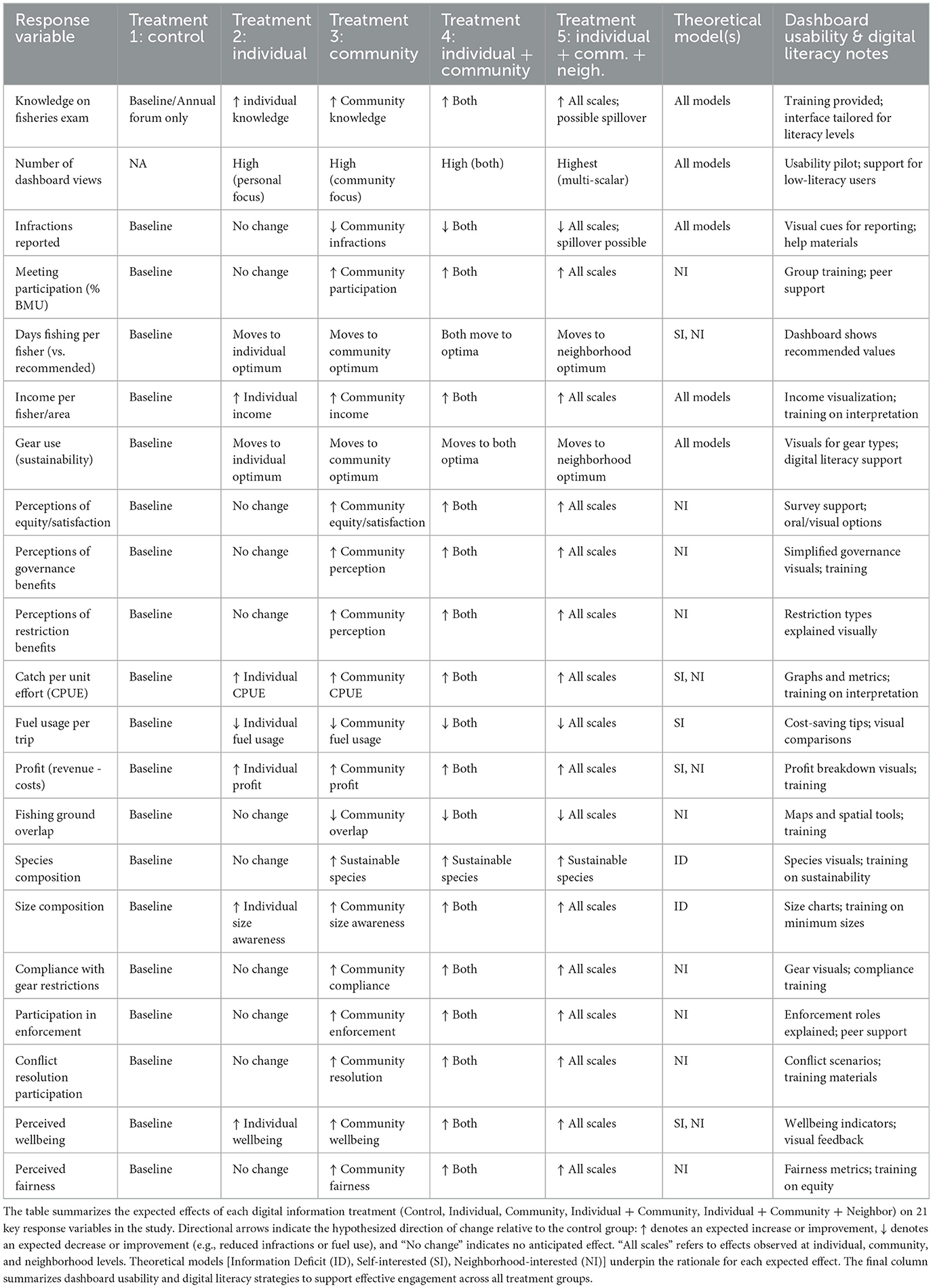

The proposed research protocol aims to evaluate the effects of digital information on behavior change in small-scale reef fisheries. The study addresses the challenges of sustainable fisheries management, particularly in environments where collective action is necessary but difficult to achieve due to diverse stakeholder behaviors and preferences. Utilizing the Knowledge-Attitude-Practice framework, the study will implement and test the WorldFish Peskas digital monitoring system across various Beach Management Units (BMUs) in Kenya. The experimental design includes five intervention levels, ranging from a control group with minimal information feedback to treatments providing increasingly localized and disaggregated. These interventions will be assessed using a Before-After-Control-Impact (BACI) approach. The study will test three heuristic models of human behavior: the information deficit model, the self-interested actor model, and the neighborhood interested actor model. These models will guide the interpretation of outcomes, which include changes in fishing practices, governance participation, and socio-economic benefits. The research will run over a 2-year period, with data collection on variables such as fishing patterns, compliance with regulations, and community well-being. Ultimately, this study seeks to inform policy on the effectiveness of digital tools in promoting sustainable fishing practices and improving livelihoods in coastal communities. The findings will provide governments and conservation organizations with a communication framework to better balance ecological sustainability with community needs.

1 Introduction

Sustainable fisheries are challenged by the environmental commons' problems. Commons are notoriously complex to manage and especially where there is an absence of knowledge, feedback information, forums, communication, and attitudes that promote cooperation, coordination, and collective action (Vollan and Ostrom, 2010). The complexity increases when resource users have close neighbors that have different preferences and extraction behaviors and fail to acknowledge their neighbors management systems. This can lead to the weakest-neighbor phenomenon where only the weakest restrictions are agreed on and followed among communities, which can lead to large-scale failures (Agrawal et al., 2013; McClanahan et al., 2024). A weak-neighborhood phenomenon is likely to occur in locations with dense populations, closely adjacent villages, and trans-jurisdictional environments (McClanahan et al., 2024; Fache and Breckwoldt, 2018; McClanahan and Abunge, 2020). Many of Kenya's nearshore coral reef fisheries provide these conditions and are therefore a good location to test various knowledge sharing and communication solutions in highly biodiverse nearshore fisheries commons (Barnes et al., 2019a,b).

Digital feedback systems such as the Peskas open-source toolkit offer real-time, scalable, and transparent information sharing, which can reduce information asymmetries, foster trust, and enable adaptive management in complex commons settings. By providing timely and localized data, these systems can empower stakeholders to make informed decisions and facilitate collective action, addressing key barriers in traditional fisheries governance. Below, we describe an experimental design proposed for implementing the Peskas digital toolkit in Kenyan nearshore fisheries. It is designed to evaluate the efficacy of the Knowledge-Attitude-Practice (KAP) framework of science communication (Gustafson and Rice, 2016) utilizing emerging technologies and digital information sharing approaches.

The KAP model has a long history in education (Sawin, 1957), and has been applied to medical practice (Kallgren and Wood, 1986) and other science communication issues, such as sustainability (Rehren et al., 2022). Outcomes have been mixed due to the complexity of human behaviors, but it remains a standard to stimulate behavioral change. We propose to examine the uptake and utility of knowledge sharing among fishing communities in the case of Kenya's coral reef fisheries commons using a before-after-control-impact (BACI) design with five levels of intervention (Table 2).

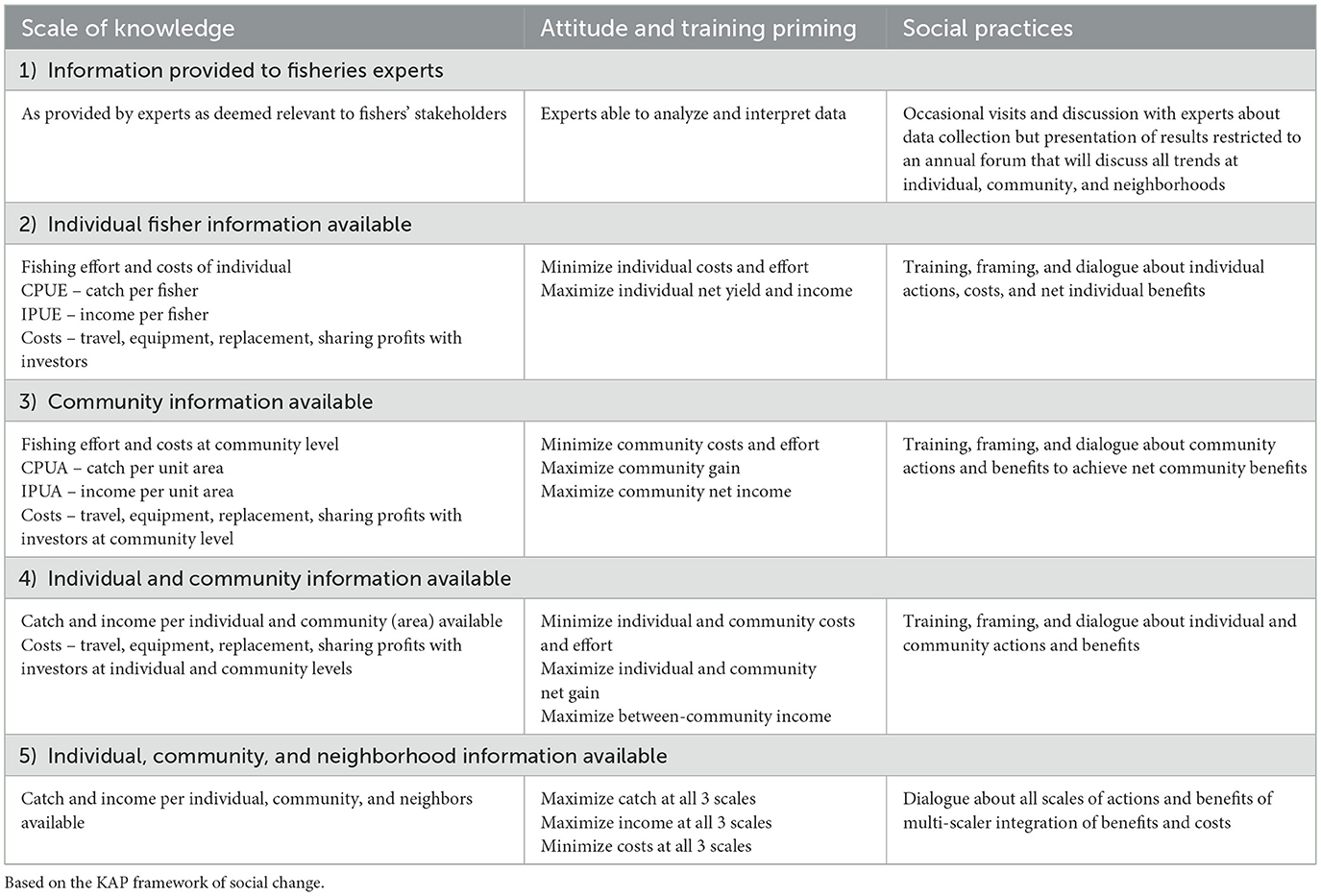

The design will be composed of five potential levels of information access and distribution. The first proposed intervention is a more standard “top-down” approach used in managing many fisheries. Here, information is collected and interpreted by people with skills to evaluate and interpret the information and report findings and recommendations to stakeholders. This treatment can be considered a control or benchmark for the other four interventions that increase the amount of locally available information. We propose many response variables that we would expect to change over the intervention period potentially representing the utility of each intervention. Proposed landing sites naturally exist in neighborhoods with nearby landing sites and these neighborhoods will be assigned different scales or levels of information inclusiveness.

In terms of a theory for making predictions, we proposed three heuristic theories, namely (1) the information deficit model, (2) a self-interested actor model, (3) a neighborhood interested actor model. These are common and simplified theories of human behaviors that will create a context for interpreting results. We acknowledge that they are potentially caricatures of more complex models of human behaviors but provide a useful tool for examining and interpreting results. The information deficit model suggests that public uncertainty and skepticism toward science (here fisheries science) around environmental issues is driven by a lack of sufficient knowledge and information, and that this can be rectified by supplying more information.

The self-interested actor model suggests that individual actors (fishers) are largely concerned with their own catch, food, and income and will largely focus on this information relevant to their condition and make decisions accordingly, as in an individual cost-benefit and opportunity cost analysis (e.g. Teh et al., 2015). The neighborhood interested actor model suggests that fishers are integral parts of local and nested communities, and this will stimulate interactions to move the production of resources to be optimized at a higher level than the individual, or a community cost-benefit where net production, profits, and sharing at a local or neighborhood will be maximized e.g. (Barnes et al., 2019a; Wilson et al., 2013; Finkbeiner et al., 2017). Measured responses in the interventions should be variable and complex but multivariate analysis should produce distinct clustering of responses that are best interpreted in terms of these three meta-theories of human behaviors.

We acknowledge that these meta-theories may be inappropriate to any specific location. Stakeholders may have ethical, political, religious, and cultural beliefs, in addition to personal histories and experiences that are not easily classified. Therefore, investigators are cognizant that responses may not represent any of the three theories of behaviors. Regardless of the theories, time and learning trade-offs among stakeholders implies that more aggregated, targeted, or pre-processed information might be more useful than raw and abundant forms of information. Community and neighborhood information may be essential to avoid commons conflicts and therefore essential to achieve larger scale goals. Failure to provide information at these large scales would, therefore, prevent reaching broad sustainable goals. This study will evaluate a potential trade-off effect of different levels of information focus as the most simplified and practical means of interpreting results. That is, there is some appropriate trade off in the levels of information that should become evident from the experimental design regardless of the theoretical context.

Our trial will evaluate the effectiveness of digital fisheries information on marine resource capture, conservation, and fisheries management preferences and behaviors in coastal reef fisheries in Kenya. Findings from our study will inform governments, practitioners, and donors on the implementation of effective digital interventions to improve dissemination of knowledge relevant to marine biodiversity and sustainable fisheries outcomes. Our study proposes a 2-year intervention among rural, coastal fishers and national government established Beach Management Units (BMUs) using a framework to test the effect of the interventions, alone and in combination.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

1. Does the provision of digital information at different scales (individual, community, neighborhood) lead to measurable changes in fisher behavior, governance participation, and socio-economic outcomes?

2. Which theoretical model (information deficit, self-interested actor, neighborhood-interested actor) best explains observed behavioral changes?

3. Is there evidence for spillover effects of information interventions across neighboring communities?

Hypotheses

H1: Increasing levels of digital feedback (toward individual) will result in greater behavioral change compared to control.

H2: Self-interested and neighborhood-interested models will predict different patterns of response to information.

H3: There will be measurable spillover effects between neighboring BMUs.

2 Study context

Fisheries management in Kenya has gone through many social-economic changes (McClanahan et al., 2005). These have included traditional management by local ethnic authorities, national government controls, and more recent development toward co-management between national and local authorities. This new concept of co-management governance evolved because of the recognition that both local and national government themselves failed to achieve both human needs and sustainable biodiverse fisheries. The latest stage in this adaptive process is the upgrading of co-management areas to Joint Co-management areas (JCMAs). Consequently, more managerial power is being given to local level governance bodies through a process of decentralization and the creation of connected co-management arrangements. Recent evaluations of nearshore fisheries governance suggest that the fisher or landing site community is the central forum for airing grievances and discussing solutions but less effective at communicating and solving problems at larger social scales (McClanahan, 2024).

Pre-colonial fisheries management was based on the recognition of local community proprietorship of nearshore fisheries (McClanahan et al., 1997). Thus, fishers were attached to and seen to have authority over fishing grounds. Fisher moved with seasonal patterns but required to observe local customs and the payment or gift-giving to local traditional authorities. Local authorities also practiced cultural customs of cleanliness, prayer, and sacrifices aimed to increase capture and reduce harm to fishers. Colonial Kenya followed a British style parliamentary governance with a strong central government that promoted an expansionist free-trade economy with few restrictions. Free trade policies lacked local propriety or enforced restrictions, which led to fisheries capture rates that could not sustain the demand for fish and a near-poverty equilibrium (McClanahan and Kosgei, 2025). The results have been a nearshore fishery where unrestricted use has led to resource capture that exceeds local production, which has degraded biodiversity and loss of employment (McClanahan, 2022).

Tourism was promoted by the colonial and post-colonial governments to gain foreign exchange needed to maintain international trade. Therefore, promoting an interest in protecting key environmental attractions for tourism through the establishment of national parks. However, the benefits to local stakeholders were often weak and a source of conflict. A few well-managed areas closed to fishing in the marine national parks and community closures locally known as “tengefus” surround these fisheries and maintain production in the near surroundings (McClanahan, 2021). Their success is variable but in some locations these parks and community closures protect many of the remaining species and populations that have become rare in the fisheries (Buckley et al., 2019; McClanahan et al., 2025). Tourism in parks has made it possible to maintain these areas in the face of pressures to exploit the last remaining resources. Therefore, there has been government revenue to maintain national control over resource management, but this has, at times, conflicted with both fisheries and some forms of local community resource use and management.

Reconciling these conflicts initiated a new set of legislation that included the introduction of Beach Management Units (BMUs) under Legal Notice 402 of the Fisheries Act in 2007. Prior to this Act, the sole managers of fisheries resources were Kenya Fisheries Services. Later from 2010 to 2013, Kenya enacted a national program of governance devolution bringing power and income to the county levels where benefits could be more locally focused. The intention of this new legislation was to resolve some problems facing Kenya fisheries. Specifically, by increasing participation in governance, as expressed in the process of rulemaking to monitoring and enforcement. The challenge being to strengthen management of landing sites and fisheries resources with the inclusion of local communities and stakeholders. Thus, participation in governance was expected to improve the production of marine resources and livelihoods of dependent communities.

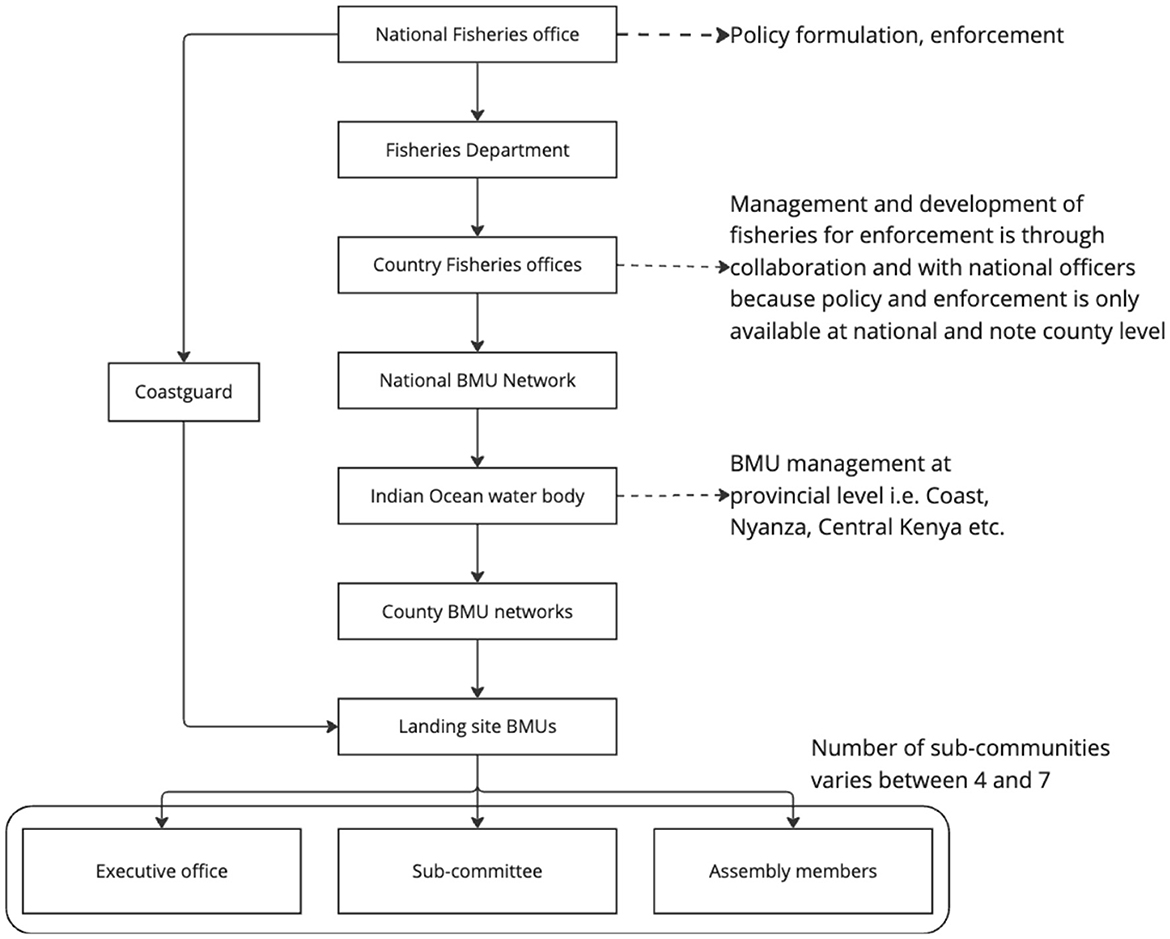

The creation of the BMU networks and Indian Ocean Waterbody caused the revision in 2014 to capture the roles of these 2 emerging governance bodies (Figure 1). The BMU now has 4 main objectives. These are: (1) to change fishers' perceptions, (2) to change fisher behavior to remove illegal gears, (3) to conserve fish resources, and (4) to improve fisher wellbeing. While there is an increasing number of governing bodies and BMUs, the number of successes is limited often because of the failure to fully integrate the principles of co-management into governance. In this way, Kenya BMUs differ from Tanzania and Mozambique, where co-management differs in the degree of national government centralization and from approaches in the Pacific Islands that emphasize customary tenure and traditional management.

Figure 1. Regulatory structure of fisheries in Beach Management Unit management system capturing the national, coast guard, county and BMU networks at distinct levels.

2.1 Mandates of three governance levels

Some of the clear mandates of the three governance systems in Kenya are as follows; The National government's role is to plan, develop and implement legislation including fisheries enforcement by national Coast Guard. They also act as the county and BMU watchdogs but primarily focused on county level (Figure 1). For example, licensing of fishers was initially under the county government but when county officers overlooked vetting systems to get votes during elections, the mandate was returned to national government.

County government takes the same role as the national government but within the boundaries of their counties. However, there are functions in the county government that are still under the national government e.g. management and development of fisheries, issuing of export permits and permission for international vessels in the Kenyan waters.

Beach management Units (BMUs) role is to identify, plan, manage and implement legislative functions within BMU itself, county and national government. It is therefore clear that development and establishment of legislation is not a BMU role. They are mandated to form sub-committees for management depending on needs and therefore the number of sub-committees varies from one BMU to another. Common sub-committees include environment, patrol, conflict resolution, sanitation/hygiene, health, welfare, finance, and enforcement. Out of the mentioned above, finance, enforcement, welfare, health should include issues of HIV and conflict resolution.

3 Methods

3.1 Experimental design

3.1.1 Timeline and workflow

The experiment will be composed of a pre-intervention, treatment period, and post-intervention period (Figure 2). The pre-intervention phase establishes baselines, stakeholder engagement and dashboards designs and should not take less than 12 months to complete. The treatment phase implements the digital feedback interventions and ongoing monitoring and will run for 12 months. The post-intervention phase involves endline data collection, analysis, and feedback and should take six months. Data collected at each stage is integrated to enable before-after-control-impact (BACI) analysis, ensuring robust attribution of observed changes to the interventions.

The first phase will involve utilizing legacy or historical fisheries catch data to Peskas and collating baseline social data from previous surveys. Pre-intervention sensitization and introductory presentations will begin in communities and BMUs, enumerators will be selected through a selective merit process, and baseline survey and catch data collection will be started. Thereafter, the design and coding of 5 information dashboards according to the 5 treatments will be initiated. The treatment period will require follow-up to ensure the KAP aspects of each treatment group are followed. The post-intervention period will begin with an endline survey, followed by data analysis, consultation, and feedback sessions, and reporting to make recommendations for future fisheries monitoring.

Several response variables (~20) will be evaluated to determine the level of influence of the interventions (Table 1). These include variables related to knowledge of fishing, fishing patterns and pressure, behavioral change, benefits of governance and restrictions, livelihood improvement, and wellbeing.

3.2 Sample and recruitment

3.2.1 Landing sites selection

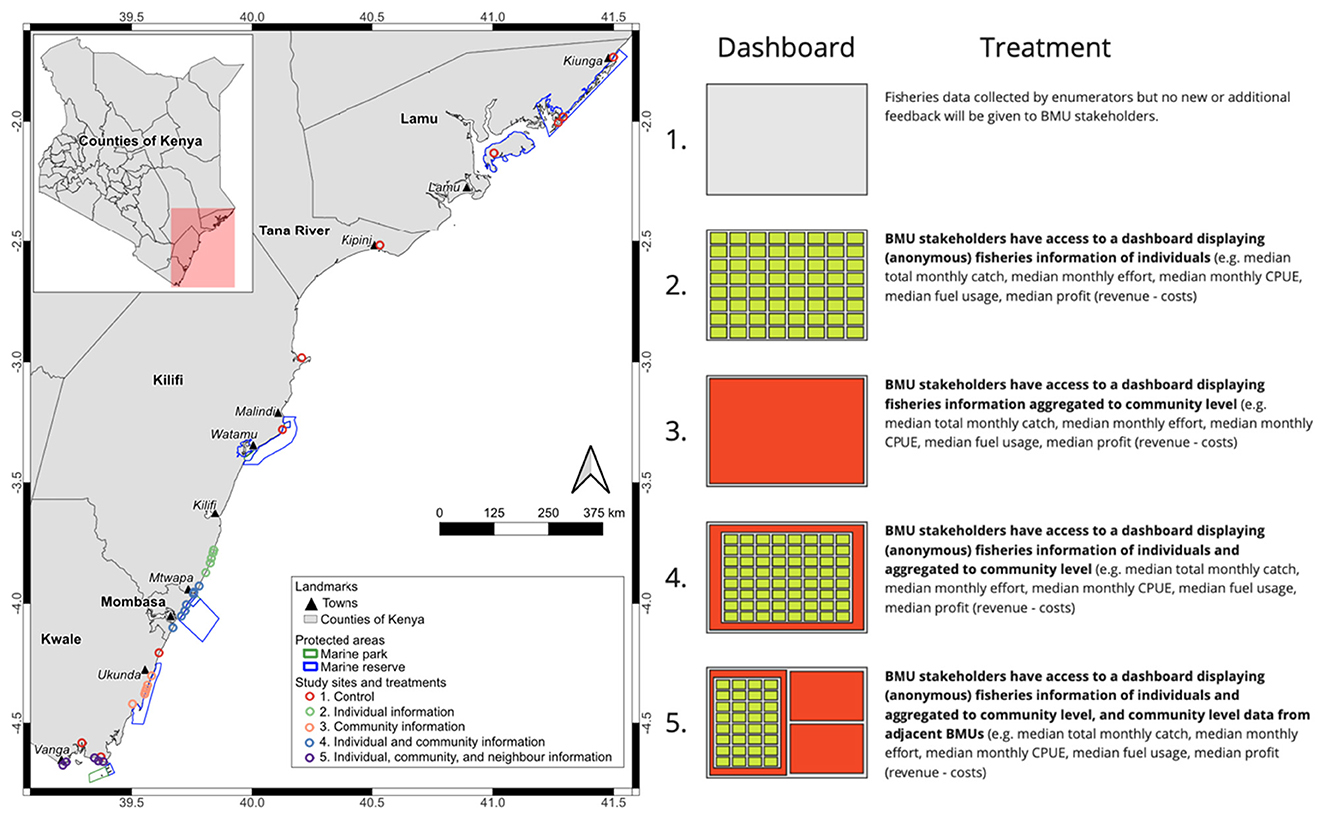

Landing sites are generally close together, particularly in the southern Kenyan fringing reef. The distance between them is about 5 km, and some smaller landings are grouped under a single BMU to fit the minimum population size criteria. Furthermore, the neighborhood informational design requires that they have neighbors that are being treated similarly by the experimental design. Consequently, the design requires working with adjacent but also administratively linked landing sites. These conditions require including related sites into a single treatment. The result is a clustered distribution of treatments along the coast except for the treatment 1 or benchmark group, which is more evenly distributed and has several more isolated landing sites (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A map depicting the proposed landing sites and the proposed treatment assignments (left pane), and a graphical representation of the treatments with detailed descriptions for formulation of the dashboards.

3.2.2 Historical interventions at landing sites

Kenyan governance went through many local and national political changes before 2010. Among the key initiatives was the establishment of nationally protected marine areas (marine protected areas – MPAs) through the efforts of Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and gear restrictions under Kenya Fisheries Service (KeFS). Specifically, management of Kisite-Mpunguti marine park and reserve from 1988 and the gazettement of Diani Chale marine reserve in 1994 by KWS, as well as introduction of fisheries restrictions in 1990s and ban on most of destructive fishing gears in 2001 by KeFS in Kwale county. KWS begun managing three no-take marine protected areas, namely Mombasa, Watamu, and Malindi between 1968 and 2012, while Kuruwitu community fully enforced no-take area in 2007 in Mombasa and Kilifi counties. Subsequently, KWS begun to manage Kiunga national marine reserve in 1979. Additionally, several BMUs within the Mombasa and Kilifi counties established locally managed community closures often characterized by low compliance and weak management.

In 2010, Kenya adopted a new constitution which gave counties resources and some independence in fisheries management decision-making. For instance, Kwale County invests more in subsidizing fishing effort through purchase of fishing gears, boats and coolers while Kilifi and Mombasa counties invest more on capacity building and initiatives aimed at restoring resources. Lamu and Tana River counties invest both in subsidizing fisheries and restoration initiatives such creation of locally managed closures and coral restoration. These differences have seen more conservation initiatives in Kwale and Lamu counties and least in Tana River due to its limited coastline. Among the conservation initiatives are gear exchanges of traditional traps with gated traps in selected landing sites in Kwale, Mombasa, and Kilifi counties. Also, training and capacity building initiatives from research institutions and non-governmental institutions.

3.2.3 Sampling frame

The sampling frame comprises rural, coastal fishers and beach management units in Kenya. The 35 BMUs selected represent sites of historical coverage of WCS programs and additional representative sites that would cumulatively inform on Kenya's fisheries. To ensure the required sample size is satisfied (in accordance with the power analysis) we will generate a list of all fishers in the fishing community, both BMU members and non-members and involve them in the experiment. All fishers will be visited and asked if they would be willing to participate in the study. Where specific fishers are not willing, they will not be included.

3.2.4 Power analysis

A power analysis was conducted to determine the adequacy of the study design for detecting a small-to-moderate effect size (Cohen's f = 0.20) in the primary outcome: number of days fishing per fisher relative to recommended levels. Assuming five groups (one control and four treatment arms), an intra-cluster correlation (ICC) of 0.05, and 25 fishers per BMU across 35 BMUs (7 per arm), the total sample size yields an effective sample size of 398 respondents after adjusting for clustering. Using this effective sample size, the study achieves a statistical power of 90.6% at a significance level of α = 0.05. The minimum number of clusters required to achieve 80% power under the same assumptions was 27 BMUs. Therefore, the current study design is sufficiently powered to detect meaningful differences across treatment groups.

3.2.5 Recruitment and consent

This research will undergo the ethical approval process of WCS/WF as well as community level discussion and approval during the pre-intervention stage. Any BMU can opt in or out of participation in this research or social experiment endeavor. Given that WCS has a long history of successful engagement with fishing communities, it is expected that most will agree to participate in this research and learning process. Eligible participants include all active fishers associated with selected BMUs, regardless of membership status. Part-time fishers will be included if they participate in fishing activities at least once per week. Non-response will be documented, and refusal rates will be reported. Sensitivity analyses will assess the impact of non-response on study findings.

3.3 Intervention details

Behavior change will be structured on the KAP framework to include various important aspects of behavioral interventions (Alves et al., 2022). The interventions will differ based on the type and availability of information made accessible to each group via digital dashboards.

Hypotheses will make predictions for the differences in rates and types of responses between the treatment groups. The Information will be organized at the individual, community, and neighborhood levels and presented to stakeholders accordingly. Control group 1 will be the default expert opinion approach, where skilled personnel will have access to all information, interpret it, and present it at intervals not to exceed one year. Treatment groups will present information about individuals, communities, individuals + communities, and individuals + communities + neighbors. The primary information they will receive is the catch, income, and costs at these different levels of pooling and relative to previously estimated sustainable fishing levels (McClanahan and Azali, 2020; McClanahan and Kosgei, 2023). Secondary information will include information about fishing gear and boat use. This will be accomplished by providing dashboards developed specifically for the 5 treatments. Observers will do both the training and follow up to ensure that there is regular learning and feedback that matches the proposed attitudes and practices.

Testing theories of human organization will be based on 5 intervention treatment groups or Beach Management Units (BMUs) (Table 2). BMUs are an existing Kenyan government legal entity to organize landing sites into related groups with some minimum size of people and infrastructure per given geographic area. These BMUs and their associations will be the basis for clustering of similar or related sites and replication of treatment programs. Treatment groups listed herein reflect the trade-off between all possible combinations and the need to replicate treatments. A total of 35 accessible landing sites spread across the 5 coastal counties of Kenya will allow 5 treatments each with replicates between 5 and 10 per treatment.

Treatment Group 1: Control group – fisheries data will be collected by enumerators at this site and uploaded to Peskas, but no structured or regular feedback will be given to local BMU stakeholders. Feedback will consist of an annual forum where results are interpreted by research partners and presented to stakeholders for discussion and recommendations.

Treatment Group 2: BMU stakeholders have access to a dashboard displaying (anonymous) fisheries information of individuals (e.g. median total monthly catch, median monthly effort, median monthly CPUE, median fuel usage, median profit (revenue - costs).

Treatment Group 3: BMU stakeholders have access to a dashboard displaying fisheries information aggregated to community level (e.g. median total monthly catch, median monthly effort, median monthly CPUE, median fuel usage, median profit (revenue - costs).

Treatment Group 4: BMU stakeholders have access to a dashboard displaying (anonymous) fisheries information of individuals and aggregated to community level (e.g. median total monthly catch, median monthly effort, median monthly CPUE, median fuel usage, median profit (revenue - costs).

Treatment Group 5: BMU stakeholders have access to a dashboard displaying (anonymous) fisheries information of individuals and aggregated to community level, and community level data from adjacent BMUs (e.g. median total monthly catch, median monthly effort, median monthly CPUE, median fuel usage, median profit (revenue - costs).

3.3.1 Dashboard design

Ordinarily, the co-designing and development of visualization dashboards with end users involves a collaborative, iterative approach to ensure the final product meets the needs and expectations of its users. However, to ensure robust testing in this experimental setting, there is a need for dashboard elements within treatment groups to be consistent, and for the iterative and consultative process to be truncated.

Prototype dashboard will be designed based on the original Peskas dashboard developed in Timor-Leste (https://timor.peskas.org/), and the catch data and sampling regime already in place in Kenya from WCS and Kenya Fisheries Service to maximize uptake and sustainability of the digital tools at the end of the study. Information will be displayed with plots and metrics in a way that is consistent as far as possible with data fed back to fisher communities and participants over the past 20 years in Kenya from WCS and government agencies.

These dashboards will be assigned to 5 user types, reflecting the 5 treatment groups and the associated level of data aggregation (Figure 3).

3.4 Outcome measures

3.4.1 Fisheries data collection

Trained community data enumerators will record data from fishers on catches at their respective landing sites 3 times per week on alternate days. Landings data will be collected digitally using KoboCollect installed on smartphones, and will include descriptive information (consent to share data, name of landing site, date of sampling, name of observer, and name of fishing ground), effort information (gear type, number of fishers, number of boats), and catch information (fish categories and associated weights nearest to 0.1kg). Data submitted by enumerators will be entered into the Peskas fisheries monitoring software as reported in Longobardi et al. (2025). The vessel activity coefficient (average length and frequency of fishing trips per month) will be calculated from geospatial tracks from vessels tracks with a vessel monitoring system (Pelagic Data Systems Inc.) and compared with fishers' reports of fishing days, trip length and catch records.

Costs of fishing will be included in the data collected by asking fishers to estimate their daily costs. These will include travel, purchase or rental of gear, ice, bait, fuel, loans, and replacement/maintenance of fishing gear, boats or engines.

The different fish categories namely, rabbitfishes, parrotfishes, goatfishes, octopus, scavengers, lobsters, sharks, rays, pelagic fishes and mixed catch generated from the commonly used groupings by fishermen/traders guided by pricing and often corresponds with fish families except three categories will be considered during weighing. The “Scavengers” category comprises both fishes in Lutjanidae and Lethrinidae families, whereas the “mixed catch” category comprises multiple families not included in other categories. The “Pelagic” category comprises families that live in midwater and upper layers of the ocean.

Additional sampling will be conducted monthly collating fish prices per kilo for each fish category. Price data will be used to estimate fishers' daily revenues based on recorded catch rates. Weighing and pricing will consider large and small fish groupings as naturally grouped by fishers/traders.

Shapefiles of community mapped fishing grounds by gear type (generated through previous WCS research in study sites will be used to calculate catch per unit area information in dashboards.

3.4.2 Household surveys

The study will include multiple interview topics designed to evaluate the household, institutional status, and preferences for restriction options prior to interventions. The key objective of the project will be to assess changes by gathering information prior to and after the intervention. A secondary objective will be to evaluate knowledge and agreement with the 2016 and 2022 national fisheries laws. The two studies will be used to assess the relationships and responses to the five treatments to enhance knowledge, engagement, and stakeholder perceptions. Household respondents will be selected by a systematic random sampling protocol whereby a sampling fraction of every ith household (e.g., 2nd, 3rd, 4th…) will be determined by dividing the total number of households by the total expected sample size given the available survey resources constraints of time and funds following (Gurney et al., 2019). In each village, we will work with community guides (1 per enumerator) to ensure the correct households are visited and to ease any unnecessary tension or reluctance to interact with strangers. Each guide will cover a different section of the community. The interview location coordinates will be recorded as part of the interview using KoboCollect software. If the head of the household is not present, we will return later. If this person is still not present, we will move to the next selected household. Interviewees will be asked about their age. Youth will be defined as individuals between 15 and 24 following the UN definition.

We will ask questions about socio-economic characteristics, including ages, gender, origin, years of residence in the community, number of years in formal education, household size, income-generating jobs per household, dependency on fish, and membership in social groups. Respondents will be asked to indicate the frequency of fish consumption, where responses will include more than once a day, once a day, once a week, and more than once a month but less than once a week.

3.4.3 Assessing the strength of governance institutions

Governance institutions or design principles will be evaluated to elicit respondent's perceptions. We chose 13 governance institutions that will be based on a modification of the 8 original Good Governance Principles (Ostrom, 2015; Cox et al., 2010). We further distinguished some principles to be clear about specifics, such as the types of monitoring (users, ecosystems, and resources) following (McClanahan and Abunge, 2019): Our list of institutions includes

1) group identity

2) clear management boundaries

3) benefits of membership

4) sharing of benefits

5) engagement in decision making

6) monitoring resources

7) monitoring fisheries

8) monitoring ecology

9) graduated sanctions

10) conflict resolution among members

11) conflict resolution between neighbors

12) group autonomy

13) polycentric governance

These institutions will be first described to respondents, who then score their strengths on a 5-point scale ranging from very weak (−2) to very strong (+2). Questions will be framed to elicit the respondent's perceptions at the scale of the seascape.

3.4.4 Perceived benefits of fisheries restrictions

Users' perceptions of fisheries restriction benefits will be evaluated by assessing management preferences of six basic types of fisheries restriction. Interviewees will be asked about specific management restrictions and their perceptions in terms of benefits and sustainability. Restrictions evaluated included gear restrictions, minimum size of fish, species selection, protected or no fishing areas, national parks, and closed seasons. Protected or areas closed to fishing will be distinguished from national parks in that the former are permanent no-fishing zones managed by various local stakeholders, and the latter are area-based management restrictions managed by the national government. A question of how each restriction is expected to benefit the fishery will be read to interviewees who then will score their perceptions of the benefit on a 5-point scale ranging from disagree completely (−2) to agree completely (+2). Respondents will be also asked who benefits most from the restriction. Perceived benefits will be in four categories of no benefit and small, medium, and large benefits. The beneficiaries will include self, community, and government.

3.5 Analytical strategy

Several response variables can be evaluated to determine the level of influence of the interventions. These include variables related to fishing pattern and pressure, behavior change, livelihood improvement, and wellbeing.

The primary outcome variable is a dummy variable that indicates to which of the five treatment arms a fisher was assigned, but treatment arms will be masked during the analysis. Our primary model is an unadjusted model. However, if we find that after unmasking, there are variables in the dataset that appear different by treatment arm, we may consider adjusting for confounders in the model.

Primary analyses will use linear mixed-effects models to account for clustering at the BMU level, with treatment arm as a fixed effect and BMU as a random effect. Difference-in-differences models will be used for BACI analysis. Logistic regression will be applied for binary outcomes. If baseline imbalances are detected, covariate adjustment will be performed, and sensitivity analyses will be conducted.

A principal component analysis (PCA) will be undertaken to evaluate the associations with demographic traits from the PCA function in FactoMineR package 2.4 in R. Household PCA scores for axis 1 and 2 will be the wealth metrics used in subsequent perceptions analyses.

Several response variables can be evaluated to determine the level of influence of the interventions. These include variables related to fishing pattern and pressure, behavior change, livelihood improvement, and wellbeing:

3.5.1 Spillover effects

In addition to our research design feature for controlling spillovers, we will formally test for evidence of spillovers across neighboring BMUs and communities using Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of the fishers and BMUs. We test whether the presence of an individual from another experimental arm in a neighboring village affects the knowledge or attitudes of the neighbor. To check whether attitudes of the control group neighbors will be affected by spillovers, we will compare outcomes of control group neighbors who are close to a treated neighbor and control group neighbors further away from treated units. Using a border-to-treatment dummy variable, a t-test will be conducted to check that control group neighbors' attitudes will be not significantly affected by the presence of a neighbor from another experimental arm.

The Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA), which requires that each unit's outcome is unaffected by the treatment status of other units. Moreover, that there is only one version of the treatment, which may also be violated if WCS or other organizations working in the study sites implement interventions like the ones proposed in the study. This is especially problematic if the control group is targeted because of the feeling that they have been left out of a potentially beneficial intervention. We have controlled for this potential problem by collecting data about all organizations working in the study site and the interventions implemented (see Site selection section and Historical interventions at landing sites). In addition, we collaborate and discuss with partner and other organizations in Kenya to understand any future interventions, to ensure alignment, and to avoid parallel interventions being targeted at the same respondents by different organizations.

3.5.2 Dealing with attrition

Our study design incorporates strategies to minimize attrition including working with existing BMUs with whom WCS have worked for many years. However, we cannot rule out that attrition may still occur due to migration or death etc. Following implementation, we will check whether attrition rates are equal across the experimental arms or if concentrated in one arm. High attrition is potentially problematic, as it could signal selection bias. In case of high attrition, we will examine the implication of attrition for our results in several ways. First, we will test whether attrition is affected by treatment assignment. For example, the proportion of fishers deciding to exit the fishery based on information they receive in the study is a variable of interest and so could also be correlated with attrition specific to a treatment group.

3.5.3 Multiple hypothesis testing

Because we are making inference on many hypotheses, it is possible that significant results emerge from our analysis due to chance rather than actual treatment effects. We will follow (Arouna et al., 2021) and adjust the p-values using suitable methods. We will calculate Romano-Wolf adjusted p-values following (Clarke et al., 2020) to correct for the familywise error rate (FWER), the probability of making at least one false discovery among a family of comparisons. We will also calculate sharpened q-values as in Anderson (2008) to correct for the false discovery rate (FDR), the probability of making at least one false discovery among the discoveries already made.

3.5.4 Balance at baseline

The balance of treatment and control groups in terms of average characteristics will be tested formally at baseline through an F-test of joint orthogonality using a multinomial logit regression, which tests whether the observable characteristics in Table 2 are jointly unrelated to treatment status (Imai et al., 2008). Failure to reject this null hypothesis indicates that randomization succeeded in achieving balance across the experimental arms. In addition, we will calculate the standardized difference in means (Deaton and Cartwright, 2016; Canavari et al., 2019). We will check whether the standardized difference in means will be below the threshold of 0.25 as recommended in literature (Canavari et al., 2019; Cochran and Rubin, 1974), indicating balance.

4 Justification and conclusions

This multi-treatment experimental design and KAP framing is unusual for fisheries but is increasingly being used to evaluate interventions for poverty alleviation (Banerjee et al., 2015) and nutrition (Tilley et al., 2022). This study will be undertaken above the individual or household level, which is the focus of poverty. Therefore, it requires more engagement and coordination above the individual and household level. This creates challenges but is expected to succeed due to the long history of WCS involvement in Kenyan beach management units through measuring fish catch, conservation trainings and capacity building, hosting regular fisheries fora and information dissemination at BMUs and social media platforms. There is already a formal catch monitoring program underway through the Kenya Fisheries Service in Kenya, which involves BMUs submitting aggregated data at the county, and then national level, but there is frustration among stakeholders who receive very limited feedback or information in return for these data. Hence, the local availability of catch statistics is the most frequently requested information that fishers and stakeholders at landing sites require.

Therefore, this intervention is seeking to simply act on this frequent request. We are, however, trying to evaluate the efficacy of this information through a BACI and multiple treatment intervention that will provide useful information going forward to developing a sustainable catch data collection system. The intervention is expected to last ~2 years, but by the 3rd year we expect to be able to hold forums to discuss the longer-term organizational options of the landing sites. This will provide important lessons for implementation on a much larger scale. It will also provide quantitative information beyond subjective self-reports that are useful but insufficient to develop a comprehensive evaluation of fisheries sustainability (Tilley et al., 2024).

5 Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged: The adoption of digital tools may be uneven, as varying levels of digital literacy and access to technology among participants could hinder effective engagement. Concerns around data privacy may also influence willingness to participate and the accuracy of self-reported information. Additionally, behavioral fatigue over the course of the intervention could reduce participant engagement and affect the consistency of data collection. Although the findings are grounded in the Kenyan context, they may hold relevance for other small-scale fisheries facing similar governance challenges; however, careful adaptation to local contexts will be necessary to ensure broader applicability.

6 Ethics and data management

Ethics approval was received from the WCS Institutional Review Board (IRB) in 2024. Written informed consent will be obtained from all fishers and respondents before recruitment into the study. Based on the experience of similar surveys and trials, no harm is expected from trial participation. Any changes to the protocol will be reported to IRB.

Anonymous data from this study and the analysis code will be available through the Open Science Framework registration, as well as on the WorldFish Harvard Dataverse Repository and GitHub respectively.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JK: Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. LL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. AT: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This publication and continued work and scaling of open access digital fisheries systems are funded by the Digital Transformation Accelerator supported by contributors to the CGIAR Trust fund and UK International Development from the UK Government as part of the Asia–Africa BlueTech Superhighway Project led by WorldFish (FCDO Project Grant Number: 301203). Views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government's official policies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agrawal, A., Brown, D. G., Rao, G., Riolo, R., Robinson, D. T., Bommarito, M., et al. (2013). Interactions between organizations and networks in common-pool resource governance. Environ. Sci. Policy. 25, 138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.08.004

Alves, C. L., Garcia, O. D., and Kramer, R. A. (2022). Fisher perceptions of Belize's Managed Access program reveal overall support but need for improved enforcement. Mar. Policy 143:105192. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105192

Anderson, M. L. (2008). Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: A reevaluation of the abecedarian, Perry preschool, and early training projects. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 103, 1481–1495. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000841

Arouna, A., Michler, J. D., Yergo, W. G., and Saito, K. (2021). One size fits all? Experimental evidence on the digital delivery of personalized extension advice in Nigeria. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 103, 596–619. doi: 10.1111/ajae.12151

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Goldberg, N., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Parienté, W., et al. (2015). Development economics. A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: evidence from six countries. Science 348:1260799. doi: 10.1126/science.1260799

Barnes, M. L., Bodin, Ö., McClanahan, T. R., Kittinger, J. N., Hoey, A. S., Gaoue, O. G., et al. (2019a). Social-ecological alignment and ecological conditions in coral reefs. Nat. Commun. 10, 2039. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09994-1

Barnes, M. L., Mbaru, E., and Muthiga, N. (2019b). Information access and knowledge exchange in co-managed coral reef fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 238:108198. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108198

Buckley, S. M., McClanahan, T. R., Quintana Morales, E. M., Mwakha, V., Nyanapah, J., Otwoma, L. M., et al. (2019). Identifying species threatened with local extinction in tropical reef fisheries using historical reconstruction of species occurrence. PLoS ONE 14:e0211224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211224

Canavari, M., Drichoutis, A. C., Lusk, J. L., and Nayga, R. M. (2019). Jr. How to run an experimental auction: a review of recent advances. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 46, 862–922. doi: 10.1093/erae/jbz038

Clarke, D., Romano, J. P., and Wolf, M. (2020). The Romano-Wolf multiple hypothesis correction in stata. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 20, 812–843. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3513687

Cochran, W. G., and Rubin, D. (1974). Controlling bias in observational studies: a review. Sankhyā Indian J. Stat. Ser. A (1961-2002). 35, 417–446.

Cox, M., Arnold, G., and Villamayor Tomás, S. A. (2010). Review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 15:38. doi: 10.5751/ES-03704-150438

Deaton, A., and Cartwright, N. (2016). Understanding and Misunderstanding Randomized Controlled Trials. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w22595

Fache, E., and Breckwoldt, A. (2018). Small-scale managed marine areas over time: Developments and challenges in a local Fijian reef fishery. J. Environ. Manage. 220, 253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.05.029

Finkbeiner, E. M., Bennett, N. J., Frawley, T. H., Mason, J. G., Briscoe, D. K., Brooks, C. M., et al. (2017). Reconstructing overfishing: moving beyond Malthus for effective and equitable solutions. Fish Fish. 18, 1180–1191. doi: 10.1111/faf.12245

Gurney, G. G., Darling, E. S., Jupiter, S. D., Mangubhai, S., McClanahan, T. R., Lestari, P., et al. (2019). Implementing a social-ecological systems framework for conservation monitoring: lessons from a multi-country coral reef program. Biol. Conserv. 240:108298. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108298

Gustafson, A., and Rice, R. E. (2016). Cumulative advantage in sustainability communication. Sci. Commun. 38, 800–811. doi: 10.1177/1075547016674320

Imai, K., King, G., and Stuart, E. A. (2008). Misunderstandings between experimentalists and observationalists about causal inference. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A. Stat. Soc. 171, 481–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2007.00527.x

Kallgren, C. A., and Wood, W. (1986). Access to attitude-relevant information in memory as a determinant of attitude-behavior consistency. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 22, 328–338. doi: 10.1016/0022-1031(86)90018-1

Longobardi, L., Sozinho, V., Altarturi, H., Cagua, E. F., and Tilley, A. (2025). Peskas: Automated analytics for small-scale, data-deficient fisheries. SoftwareX 29:102028. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2024.102028

McClanahan, T., and Abunge, C. (2020). Perceptions of governance effectiveness and fisheries restriction options in a climate refugia. Biol. Conserv. 246:108585. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108585

McClanahan, T. R. (2021). Marine reserve more sustainable than gear restriction in maintaining long-term coral reef fisheries yields. Mar. Policy 128:104478. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104478

McClanahan, T. R. (2022). Fisheries yields and species declines in coral reefs. Environ. Res. Lett. 17:044023. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ac5bb4

McClanahan, T. R. (2024). Usage and coordination of governance principles to address proximate and distal drivers of conflicts in fisheries commons. Conserv. Biol. 38:e14178. doi: 10.1111/cobi.14178

McClanahan, T. R., and Abunge, C. A. (2019). Conservation needs exposed by variability in common-pool governance principles. Conserv. Biol. 33, 917–929. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13258

McClanahan, T. R., and Azali, M. K. (2020). Improving sustainable yield estimates for tropical reef fisheries. Fish Fish. 21, 683–699. doi: 10.1111/faf.12454

McClanahan, T. R., Glaesel, H., Rubens, J., and Kiambo, R. (1997). The effects of traditional fisheries management on fisheries yields and the coral-reef ecosystems of southern Kenya. Environ. Conserv. 24, 105–120. doi: 10.1017/S0376892997000179

McClanahan, T. R., and Kosgei, J. K. (2023). Low optimal fisheries yield creates challenges for sustainability in a climate refugia. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5:e13043. doi: 10.1111/csp2.13043

McClanahan, T. R., and Kosgei, J. K. (2025). Variation in coral reef fisheries production, employment, and living wage goals. Coral Reefs. doi: 10.1007/s00338-025-02779-7

McClanahan, T. R., Kosgei, J. K., and Humphries, A. T. (2025). Fisheries sustainability eroded by lost catch proportionality in a coral reef seascape. Sustainability 17:2671. doi: 10.3390/su17062671

McClanahan, T. R., Mwaguni, S., and Muthiga, N. A. (2005). Management of the Kenyan coast. Ocean Coast. Manag. 48, 901–931. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.03.005

McClanahan, T. R., Oddenyo, R. M., and Kosgei, J. K. (2024). Challenges to managing fisheries with high inter-community variability on the Kenya-Tanzania border. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 7:100244. doi: 10.1016/j.crsust.2024.100244

Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316423936

Rehren, J., Samoilys, M., Reuter, H., Jiddawi, N., and Wolff, M. (2022). Integrating resource perception, ecological surveys, and fisheries statistics: a review of the fisheries in Zanzibar. Rev. Fish Sci. Aquac. 30, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/23308249.2020.1802404

Sawin, E. I. (1957). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook 1. Committee of college and university examiners, Benjamin S. bloom. Elem Sch J. 57, 343–344. doi: 10.1086/459563

Teh, L. S. L., Teh, L. C. L., Sumaila, U. R., and Cheung, W. (2015). Time discounting and the overexploitation of coral reefs. Environ. Resour. Econ. 61, 91–114. doi: 10.1007/s10640-013-9674-7

Tilley, A., Byrd, K. A., Pincus, L., Klumpyan, K., Dobson, K., Dos Reis Lopes, J., et al. (2022). A randomised controlled trial to test the effects of fish aggregating devices (FADs) and SBC activities promoting fish consumption in timor-leste: a study protocol. PLoS ONE 17:e0269221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269221

Tilley, A., Dam Lam, R., Lozano Lazo, D., Dos Reis Lopes, J., Freitas Da Costa, D., De Fátima Belo, M., et al. (2024). The impacts of digital transformation on fisheries policy and sustainability: lessons from timor-leste. Environ. Sci. Policy 153:103684. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2024.103684

Vollan, B., and Ostrom, E. (2010). Social science. Cooperation and the commons. Science 330, 923–924. doi: 10.1126/science.1198349

Keywords: small-scale fisheries, behavioral intervention, governance, digital feedback, information use, value of information, behavior change

Citation: McClanahan T, Kosgei J, Longobardi L and Tilley A (2025) How much is too much information? Testing the effects of digital feedback on fisher behavior and governance in coastal small-scale fisheries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1689512. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1689512

Received: 20 August 2025; Revised: 02 November 2025;

Accepted: 11 November 2025; Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Victor Owusu, University of Education-Winneba, GhanaReviewed by:

Shyam Salim, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (ICAR), IndiaBenedict Arko, University of Education-Winneba, Ghana

Copyright © 2025 McClanahan, Kosgei, Longobardi and Tilley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexander Tilley, YWxleC50aWxsZXlAZ21haWwuY29t

Tim McClanahan

Tim McClanahan Jesse Kosgei1

Jesse Kosgei1 Alexander Tilley

Alexander Tilley