- 1Taizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Taizhou, China

- 2State Key Laboratory of Vegetable Bio-breeding, Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China

- 3Jiaojiang District Seed Affairs Station of Taizhou, Taizhou, China

Home food gardening (HFG) is increasingly popular worldwide. Understanding the preferences and challenges of HFG participants holds significant value for the horticulture industry. Tomatoes, a favored ingredient in Chinese cuisine, are particularly popular among Chinese HFG participants. To evaluate their preferences, challenges, and experiences with tomato cultivation, we conducted a survey of 1,296 Chinese tomato growers through social media platforms by using a citizen-science approach, and assessed the germination rates of 400 tomato varieties. The provinces of Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang exhibit the highest proportions of home tomato growers, accounting for 18.75, 16.67, and 15.97%, respectively. East China (including Shanghai, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, Anhui Province, Fujian Province, Jiangxi Province, and Shandong Province) is the region with the highest concentration of growers, accounting for 46.53% of the total. Most respondents fall within the age range of 25 to 39 years (84.03%), with females outnumbering males, comprising 86.11% of the participants. Over 80.00% of respondents have <4 years of cultivation experience. The primary motivation for growing tomatoes is personal or family preference (87.50%). Preferred cultivation sites include rooftops (38.19%) and residential peripheral plots or wasteland (31.94%). Regarding tomato species selection, 60.42% of respondents opt for cherry tomatoes, while double-stem pruning is favored by 39.58%. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TY virus) affects 39.58% of growers, and red spider mites impact 45.83%. Fruit cracking during the rainy season is the most prevalent issue, occurring in 66.67% of cases. A significant majority of respondents (95.14%) purchase seeds online, with 22.22% willing to pay over 10 CNY (Chinese Yuan) per seed. Desired seed pack sizes are predominantly 3 to 5 seeds (75.00%) and 6 to 10 seeds (40.97%). Seed mystery boxes are rejected by 79.86% of respondents. Only 40.00% of seeds purchased online demonstrate a germination rate exceeding 80.00%, while 7.50% have a germination rate of 0. Tomatoes are popular in Chinese HFG, and challenges such as pests, diseases, and inconsistent seed quality require attention. To better meet the needs of Chinese HFG participants, it is suggested that seed producers can introduce tomato seeds in small package sizes specifically tailored to their requirements. Additionally, QR codes can be attached to the seed packaging, enabling HFG participants to scan the QR codes and obtain relevant prevention and control techniques for various pests and diseases that may occur during tomato cultivation.

Introduction

Urbanization has brought benefits in education, and healthcare, however, it has also posed potential threats to food security (Weidner et al., 2019). Fresh vegetables play an important role in human dietary (Romero et al., 2022; Deng et al., 2023). Currently, the supply of fresh vegetables in most cities worldwide relies heavily on external supply chains (Zasada et al., 2019; Jensen and Orfila, 2021; Song et al., 2021; Murdad et al., 2022; Hossain et al., 2023). However, major public health events (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) (Khan et al., 2020; Lal, 2020; Underhill et al., 2023), geopolitical tensions (e.g., the Israel-Palestine conflict) (Bar-Nahum et al., 2020), as well as geological and meteorological disasters can all cause severe traffic congestion or interruptions, leading to shortages of vegetables in urban areas. This, in turn, triggers panic among citizens, resulting in hoarding and stockpiling of vegetables, which further exacerbates the supply crisis (Cattivelli, 2022; Kpadé et al., 2023).

Since the beginning of the 21st century, urbanization rate in China has been growing at an average annual rate of 1.04%, now this rate has exceeded 60.00% (Zeng et al., 2022). It is projected that by 2050, this rate will reach 70.00%, with the urban population increasing by 300–400 million compared to the early 2020s (Wang and Salman, 2023). Rapid urbanization poses significant challenges to vegetable supply in Chinese cities (Li et al., 2023). For instance, in Shanghai between 27th March and 1st June 2022, authorities closed roads and implemented exhaustive quarantine checks to contain the spread of COVID-19, throttling the supply chains that deliver fresh produce and leaving the city’s markets severely short of vegetables (Han et al., 2024a, 2024b).

Home food gardening (HFG), also known as home gardening, residential food gardening, or household food gardening, refers to the small-scale agricultural activity where residents use spaces such as courtyards, balconies, windowsills, patios, rooftops, and small plots of land adjacent to their homes to grow edible horticultural plants. The products from home gardens are primarily consumed by family members, and any surplus is often shared with neighbors or friends and relatives (Kortright and Wakefield, 2011; Burgin, 2018; Grebitus, 2021; Song et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2024). In the event of a disruption in the supply chain of vegetables, the produce from home gardens can meet the short-to medium-term nutritional needs of residents (Kortright and Wakefield, 2011). Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing number of people worldwide have begun to pay attention to and practice HFG (Music et al., 2022; Perez-Lugones et al., 2023). Surveys indicate that during the COVID-19 pandemic, 17.40% of the population in Canada started practicing HFG (Mullins et al., 2021), and the number of people engaging in HFG in Europe also increased by 10.00% (Turnšek et al., 2022). Chinese people have a deep-seated fondness for growing vegetables in the vicinity of their homes, transforming even the tiniest plot of land into a vegetable garden. This inclination can be traced back to the deeply rooted agricultural ethos that has long been a part of Chinese culture (Deng et al., 2023; Xie and Xing, 2024). Despite the absence of nationally representative data, empirical observations nevertheless indicate an intense interest in HFG among urban residents throughout China (Figures 1a,b) (Clarke et al., 2014; Wei and Jones, 2022; Xie and Xing, 2024).

Figure 1. Tomato plants grown in Chinese residential areas, which have highly decorative value (a,b), tomatoes harvested by a HFG tomato grower from Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, China (c).

In addition to providing food, HFG has many other benefits: (1) HFG has good aesthetic values (Figures 1a,b) (Santos et al., 2022); (2) For individuals living alone, sharing gardening experiences and giving away surplus horticultural products from home gardens can help them build harmonious neighborly relationships and effectively alleviate feelings of loneliness (Theodorou et al., 2021); (3) For individuals with high work and life stress, HFG can help alleviate mental stress (Corley et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022); (4) For parents, engaging in HFG is an excellent educational method, allowing children to fully interact with and experience nature (Chalmin-Pui et al., 2021); (5) Compared to other entertainment activities in cities, HFG is relatively inexpensive and affordable for most people (Xu et al., 2024); (6) HFG can regulate the microclimate of dwellings and even reduce the urban heat island effect (Al-Mayahi et al., 2019); (7) HFG can significantly reduce the fossil fuel consumption during the transportation of fresh vegetables (Li et al., 2023); (8) New immigrants plant vegetables from their hometowns in their home gardens and cook dishes with their cultural characteristics, which helps to alleviate homesickness (Head et al., 2004; Taylor and Lovell, 2015); (9) Some home gardens plant local native plants, which helps to maintain local plant diversity (Suwardi et al., 2023); (10) Some HFG enthusiasts use compost bins, compost bags, and other devices to make their own compost, which can significantly reduce the disposal costs of kitchen waste, and fallen leaves (Gao et al., 2022).

Tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) are versatile, serving both as fruits and vegetables. They are rich in soluble sugars, vitamin C, amino acids, folic acid, dietary fiber, minerals, and other nutrients, making them the second most consumed vegetable globally, just after potatoes (Panno et al., 2021; Han et al., 2024a, 2024b). Tomato fruits have good aesthetic values, as shown in Figure 1c, they come in a wide variety of types with a rich array of fruit colors, including red, pink, orange, yellow, light yellow, green, purple, and white (Ha et al., 2021; Naeem et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). They also exhibit diverse shapes such as round, oval, and pear-shaped (Safaei et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2022; Tripodi et al., 2023). These strengths converge to make the tomato the undisputed star of the home gardens worldwide. Statistics show that nearly 90.00% of home gardens in the United States cultivate tomatoes (Mullins et al., 2021; Cruz and Gómez, 2022; Perez-Lugones et al., 2023). Tomatoes are also highly favored and widely consumed across China, featuring prominently in various Chinese dishes, such as stir-fried tomatoes with eggs, and braised beef brisket with tomatoes. As depicted in Figures 1a,b, many Chinese HFG enthusiasts have been cultivating tomatoes in their residences. However, at present, there is limited research focusing on the actual situation of tomato cultivation in Chinese HFG.

According to the preliminary investigation conducted by the authors, Chinese HFG enthusiasts primarily purchase tomato seeds through three channels currently: (1) Buying seeds from agricultural supply stores or markets; (2) Purchasing repackaged seeds through online shopping platforms such as Taobao, Kuaituantuan, RED, and Pinduoduo; (3) Organizing group purchases, where orders are placed and seed requirements are tallied using WeChat groups. The group organizer then buys original packaging seeds from seed companies or dealers, distributes them according to the pre-orders, and finally delivers them to each HFG enthusiast via mail. Additionally, some tomato seeds come from other sources, including seeds saved by HFG tomato growers, small trial packages given by seed companies (such as Rijk Zwaan), seeds provided by agricultural research institutions (such as local agricultural academies), and seeds exchanged or gifted among other HFG enthusiasts.

Due to constraints on planting space and spare time, individual HFG tomato growers typically require a small quantity of seeds for a single variety, usually no more than 10 seeds. However, the original packaging of tomato seeds in China is predominantly large, such as 1,000 seeds per pack, 500 seeds per pack, and 100 seeds per pack. This greatly increases the difficulty for HFG enthusiasts to purchase original seeds, often leading them to opt for repackaged seeds, which may pose potential quality risks. While methods like WeChat group purchases can partially alleviate this issue, it is often challenging for online groups composed of HFG enthusiasts, such as WeChat and QQ groups, to organize orderly and effective group purchases. Additionally, the subsequent seed distribution process is time-consuming and labor-intensive. According to surveys, the original packaging of Japanese tomato seeds is typically smaller, with sizes like 8 seeds per pack, 10 seeds per pack, 13 seeds per pack, 15 seeds per pack, and 16 seeds per pack. This effectively reduces the inconvenience caused by the excessive number of seeds in original packaging for HFG enthusiasts. Similar to the seed challenges faced in commercial production, many imported seeds used in HFG are also extremely expensive. As shown in Table 1, the Japanese tomato varieties BLOODY TIGER and ROUGE JAPONESE sold by Taobao merchants, both have a retail price of 138.00 CNY per pack, with each pack containing 8 seeds. This results in a high price of 17.25 CNY per seed, which deters most HFG enthusiasts from purchasing them.

In recent years, the mystery box economy has been gaining immense popularity in China (Liu, 2024). Mystery box originated from Japan’s fukubukuro. Merchants typically pack items with a higher value than the price of the fukubukuro into these boxes for sale. Due to their attractive cost-performance ratio, they have attracted many consumers. Over time, mystery boxes have evolved into a distinct sales model (Liao, 2024). Seed mystery boxes represent a unique seed sales approach where various types of seeds are randomly mixed into a single package. Consumers are unaware of the specific seeds they will receive until they open the package (Xu et al., 2024). Currently, Chinese e-commerce platforms like Taobao feature an array of tomato mystery box seed packs. These seed mystery boxes are relatively affordable and offer a delightful surprise for growers. However, they may also present challenges such as inconsistent pedigrees, poor resistance to adverse conditions, susceptibility to diseases, variability in fruit quality, and difficulty in ensuring consistent yields (Ma et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2024).

Consumer-horticulture encompasses a broad range of activities and interests related to horticultural products, including consumers’ demands, consumer motivations, preferences, and purchasing behaviors. HFG is closely related to consumer-horticulture, for example, the demands and preferences of HFG directly affect the market dynamics of consumer-horticulture. Citizen science serves as a highly effective approach within consumer-horticulture research, facilitating collaboration between academics and community members. This participatory research method proves to be a dependable means of gathering data across extensive geographical regions and offers invaluable insights into the experiences and preferences of participants (Perez-Lugones et al., 2023). To provide valuable insights and support to stakeholders in the horticulture industry, our research team conducted a questionnaire survey on the current state of HFG tomato cultivation by using a citizen-science approach. We interviewed HFG tomato growers through various social media platforms such as Weibo, WeChat groups, QQ groups, Tik Tok, Bilibili, and RED. Based on the survey results, we summarized and analyzed the population characteristics, planting preferences, issues encountered during the tomato cultivation process, and the use of seeds among Chinese HFG tomato growers.

Materials and methods

Recruitment, participant selection, and data collection

Prior to initiating the recruitment of project participants, all relevant documents for this study, including digital press releases, the project protocol, and the questionnaire, were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Taizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The survey for this study was administered from October 1st to December 31st, 2024. The target population included residents from China Mainland. To launch the survey, we first publicized our intentions and detailed information on a variety of online platforms, including Weibo, WeChat groups, QQ groups, TikTok, Bilibili, and RED. Subsequently, we invited participants to submit photographs of themselves engaging in HFG activities, specifically planting tomatoes, as tangible evidence of their involvement in HFG. To avoid repeated participation by users in the same region/community, we perform deduplication based on IP addresses or user information. As a token of our appreciation for their participation in the survey, we provided each respondent who completed the survey with a selection of tomato seeds from various cultivars as a gift. Informed consent has been obtained from all participants in the study.

The questionnaire (Table 2) covered the following aspects: region of residence, age, gender, years of tomato cultivation experience, reasons for choosing to grow tomatoes, planting site, planting arrangements and reasons, pruning methods, common diseases, common pests, other issues encountered during the planting process, seed sources, the highest price willing to pay for a single tomato seed, desired seed packaging specifications, and whether they would choose to purchase seed mystery boxes and the reasons for doing so. Ultimately, we successfully interviewed 1,296 Chinese nationals who are enthusiastic about tomato cultivation through these online platforms. After obtaining all the questionnaire results, the data were entered, organized, and analyzed using WPS Office 2019.

Detection of seed germination capacity

Additionally, we purchased seeds of 400 tomato varieties from 20 online stores on the Taobao platform, with 30 seeds for each variety. The seed germination experiment was conducted from November 21th, 2024 to April 16th, 2025, in the greenhouse of Taizhou Agricultural Science and Innovation Park in Taizhou, Zhejiang Province. The specific procedure was as follows: after receiving the seeds, we opened the packaging, did not soak the seeds, and directly sowed them into 50-hole trays containing moistened peat, recording the sowing time for each variety. After sowing, we thoroughly watered the trays. During the seedling cultivation period, the daytime temperature was maintained at 25 to 30°C, and the nighttime temperature was kept at 15 to 20°C. Based on actual needs, we irrigated the seedlings once every 5 to 7 days using a tidal irrigation system. Twenty days after sowing, we calculated the germination rate for each variety. After obtaining the data, we entered, organized, and analyzed it using WPS Office 2019.

Results

Population characteristics

Geographical distribution

As shown in Table 3, among all provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China, Guangdong Province has the highest proportion of HFG tomato growers, accounting for 18.75%. Next is Jiangsu Province, with a proportion of 16.67%, followed by Zhejiang Province at 15.97%, and then Sichuan Province at 11.11%. Among the remaining provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions, only Shanghai has a proportion exceeding 5.00%, reaching 5.56%. All other provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions have proportions below 5.00%. Additionally, in this survey, some provinces and autonomous regions did not record any participants.

Table 3. Distribution of HFG tomato growers in provinces, municipalities, or autonomous regions in China.

China is divided into seven major geographical regions. The Northeast China includes Liaoning Province, Jilin Province, and Heilongjiang Province. The North China region covers Beijing, Tianjin Province, Hebei Province, Shanxi Province, and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The East China region comprises Shanghai, Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, Anhui Province, Fujian Province, Jiangxi Province, and Shandong Province. The Central China region consists of Henan Province, Hubei Province, and Hunan Province. The South China region includes Guangdong Province, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, and Hainan Province. The Southwest China encompasses Chongqing, Sichuan Province, Guizhou Province, Yunnan Province, and Tibet Autonomous Region. The Northwest China comprises Shaanxi Province, Gansu Province, Qinghai Province, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, and Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. As shown in Figure 2a, it can be seen that among the seven major geographical regions in China, the East China region has the highest number of HFG tomato growers, accounting for 46.53%, this may be attributed to the fact that the urbanization rate in East China is higher than the national average in China. According to data from 2023, the overall urbanization rate in East China is higher than the national average. Specifically, the urbanization rate in East China has exceeded 70.00%, with Zhejiang Province at 74.23% and Jiangsu Province at 75.04%. Shanghai, as a core city, has an urbanization rate exceeding 89.46%. The national average urbanization rate in China in 2023 is 66.16%. This indicates that the East China region is in a leading position in the urbanization process, with a significantly higher urbanization rate than the national average (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2024). The South China region ranks second, with a proportion of 22.22%, followed by the Southwest region at 13.19%, and the Central China region at 9.72%. The North China, Northeast, and Northwest regions have fewer participants, with proportions all below 5.00%, specifically 4.86, 2.08, and 1.39%, respectively.

Figure 2. Geographical (a), age (b), gender (c), and planting experience (d) distribution of Chinese HFG tomato growers.

Age distribution

As shown in Figure 2b, among HFG tomato growers, those aged under 25 account for 4.86%, those aged 25 to 29 account for 22.92%, those aged 30 to 34 account for 31.94%, those aged 35 to 39 account for 29.17%, those aged 40 to 44 account for 5.56%, and those aged 45 and above account for 5.56%. The majority of HFG tomato growers are aged between 25 and 39, with a significant proportion of 84.03%.

Gender distribution

As shown in Figure 2c, among HFG tomato growers, the number of female participants far exceeds that of males, accounting for as much as 86.11%, while the male group only makes up 13.89%.

Planting experience

As shown in Figure 2d, 47.92% of HFG tomato growers have been growing tomatoes for no more than 2 years; 36.11% have been growing tomatoes for more than 2 years but no more than 4 years; 9.03% have been growing tomatoes for more than 4 years but no more than 6 years; 2.78% have been growing tomatoes for more than 6 years but no more than 8 years; 3.47% have been growing tomatoes for more than 8 years but no more than 10 years; and only 0.69% have been growing tomatoes for more than 10 years.

Planting preferences

Reasons for planting tomatoes

As shown in Figure 3, as high as 87.50% of HFG tomato growers choose to plant tomatoes because they or their family members enjoy eating them, they can grow varieties not available on the market, and the tomatoes they produce are more mature and safer. Additionally, 54.86% of HFG tomato growers choose to plant tomatoes because they enjoy the process of planting and harvesting, which can relieve stress and provide a sense of achievement. Furthermore, 21.53% of HFG tomato growers choose to plant tomatoes due to their high ornamental value. Moreover, only 9.72% of HFG tomato growers choose to plant tomatoes to give as gifts to friends and family. The reason tomatoes are easier to cultivate than other fruit and vegetable crops is not the main motivation for most HFG tomato growers to cultivate tomatoes, accounting for only 2.78%.

Figure 3. Chinese HFG tomato growers’ reasons for growing tomatoes and the proportion of each reason (Participants can choose multiple reasons; therefore, the sum of the percentages in this figure does not equal 100%).

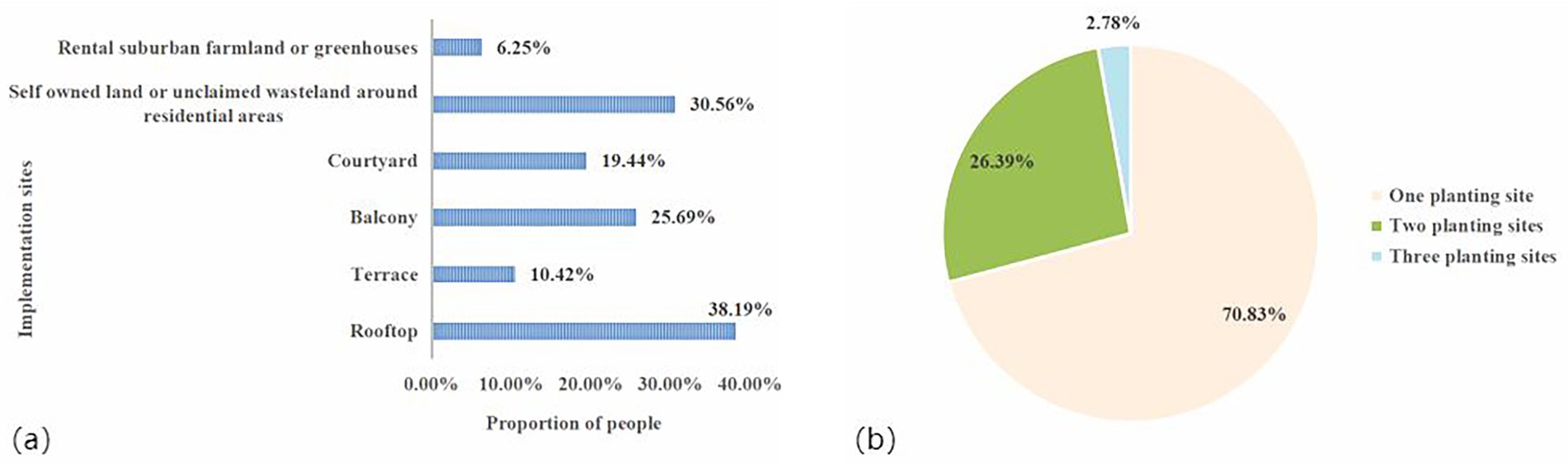

Implementation sites

As shown in Figure 4a, 38.19% of HFG tomato growers choose to cultivate tomatoes on rooftops; 30.56% choose to grow them in their own plots or unclaimed wasteland around their residences; 25.69% choose to grow them on balconies; 19.44% choose to grow them in their own courtyards; 10.42% choose to grow them on terraces; and 6.25% choose to rent arable land or greenhouse in the suburbs for growing tomatoes. As shown in Figure 4b, some HFG tomato growers have multiple types of sites for growing tomatoes. The proportion of those who grow tomatoes in two different types of sites is 26.39%, and the proportion of those who grow tomatoes in three different types of sites is 2.78%.

Figure 4. Distribution of sites (a) and site types (b) of Chinese HFG tomato growers [Participants could choose multiple implementation sites; therefore, the sum of the percentages in (a) does not equal 100%].

Planting arrangements and reasons

As shown in Figure 5a, over half of the HFG tomato growers prefer a planting arrangement dominated by cherry tomatoes, with a proportion as high as 60.42%. Additionally, 14.58% of the population choose to plant only cherry tomatoes. 20.14% of the HFG tomato growers allocate half of their planting area to cherry tomatoes, and the other half to medium and large-sized tomatoes. Only 4.86% of the population prefer a planting arrangement dominated by medium and large-sized tomatoes. Almost everyone plants cherry tomatoes to some extent.

Figure 5. Proportion of planting arrangements among Chinese HFG tomato growers (a), the reasons why only grow cherry tomatoes and the proportion of each reason (b), the reasons why some Chinese HFG tomato growers choose to mainly grow cherry tomatoes and the proportion of each reason (c), the reasons why some Chinese HFG tomato growers choose to mainly grow tomatoes with medium and large fruit sizes, and the proportion of each reason (d) (Participants could select multiple reasons; therefore, the sum of the percentages in b–d does not equal 100%).

As depicted in Figure 5b, among those who choose to plant only cherry tomatoes, 66.67% do so because cherry tomatoes are easier to grow compared to medium and large-sized tomatoes, being less prone to cracking and less susceptible to blossom end rot. 61.90% of the people prefer them due to their rich flavor and small size, making them more suitable for fresh consumption. 52.38% of the population choose them for their vibrant colors and beautiful clusters, which provide better ornamental value.

As illustrated in Figure 5c, among those who primarily plant cherry tomatoes, 28.47% do so because they are easier to grow than medium and large-sized tomatoes, being less likely to crack and less prone to blossom end rot. 53.47% of the people prefer them for their rich flavor and small size, which makes them more suitable for fresh consumption. 37.50% of the population choose them for their vibrant colors and beautiful clusters, which offer better ornamental value.

As shown in Figure 5d, among those who mainly plant medium and large-sized tomatoes, 71.43% do so because, despite the higher cultivation difficulty, there is a greater sense of achievement at harvest time. 85.71% of the people prefer them because medium and large-sized tomatoes are more suitable for culinary use compared to cherry tomatoes.

Pruning methods

As shown in Table 4, regardless of the type of tomato being grown, 25.69% of HFG tomato growers choose single-stem pruning, while 39.58% prefer double-stem pruning, and 1.39% opt for triple-stem pruning. Additionally, 11.81% adjust their pruning methods based on the size of the cultivation container, opting for double-stem, triple-stem, or multi-stem pruning when the container is large, and single-stem pruning when it is small. Furthermore, 10.42% base their pruning on planting density, using single-stem pruning for high density and double-stem, triple-stem, or multi-stem pruning for low density. Another 9.03% vary their pruning methods according to the tomato variety, choosing single-stem pruning for medium and large fruit types and double-stem, triple-stem, or multi-stem pruning for cherry tomatoes. A small percentage, 0.69%, use double-stem pruning in summer and single-stem pruning in autumn. Also, 0.69% prune occasionally due to lack of time, resulting in disorganized branches, and another 0.69% have not yet started pruning due to insufficient knowledge of pruning techniques.

Problems encountered during tomato cultivation

Common diseases

As shown in Table 5, the TY virus is the most common disease in tomatoes grown under home conditions, with an incidence rate as high as 39.58%. The second most prevalent disease is bacterial wilt, with an incidence rate of 13.19%. The diseases ranking third, fourth, and fifth in terms of incidence are gray mold, leaf spot, and blight, with rates of 12.50, 11.11, and 5.56%, respectively. Anthracnose, late blight, early blight, canker, and root rot occasionally occur in tomatoes, with incidence rates of 2.08, 2.08, 0.69, 0.69, and 1.39%, respectively. It is noteworthy that over 30.00% of HFG tomato growers are unable to effectively identify these diseases, making it difficult to apply appropriate treatments.

Common pests

As shown in Table 5, under home conditions, the red spider mite is the most prevalent pest affecting tomatoes, with an occurrence rate as high as 45.83%. The second most common pest is the whitefly, accounting for 24.32%. The third, fourth, and fifth most common pests are the Polyphagotarsonemus latus, leafminer, and bollworm, with occurrence rates of 22.22, 16.67, and 11.11%, respectively. Aphids, thrips, armyworm, scale insects, snails, Aulacophora femoralis, Drosophila, scarab beetles, and citrus rust mites occasionally cause damage to tomatoes, with occurrence rates of 5.56, 4.86, 2.78, 2.08, 1.39, 0.69, 1.39, 0.69, and 0.69%, respectively. It is noteworthy that 15.97% of HFG tomato growers are unable to effectively identify these pests, making it difficult for them to manage and control the infestations.

Other problems encountered during cultivation

Table 5 indicates that the most common issue faced by Chinese HFG tomato growers while growing tomatoes is fruit cracking during the rainy season, affecting 66.67% of growers. Additionally, low temperatures and weak light in winter, as well as high temperatures in summer, pose challenges to 18.06 and 11.81% of growers, respectively. Blossom end rot was observed by 7.64% of growers during tomato cultivation. Furthermore, 6.25% of growers consider the weak light conditions on indoor and lower-floor balconies to be a significant problem for tomato growth. Bird hazard, as shown in Figure 6, is also a notable issue for 5.56% of growers. Other problems, such as difficulty in cultivating strong seedlings, waterlogging, lack of knowledge in water and fertilizer management leading to waterlogging or seedling burn, and weak light during the rainy season, are less common, affecting 3.47, 1.39, 1.39, and 0.69% of growers, respectively.

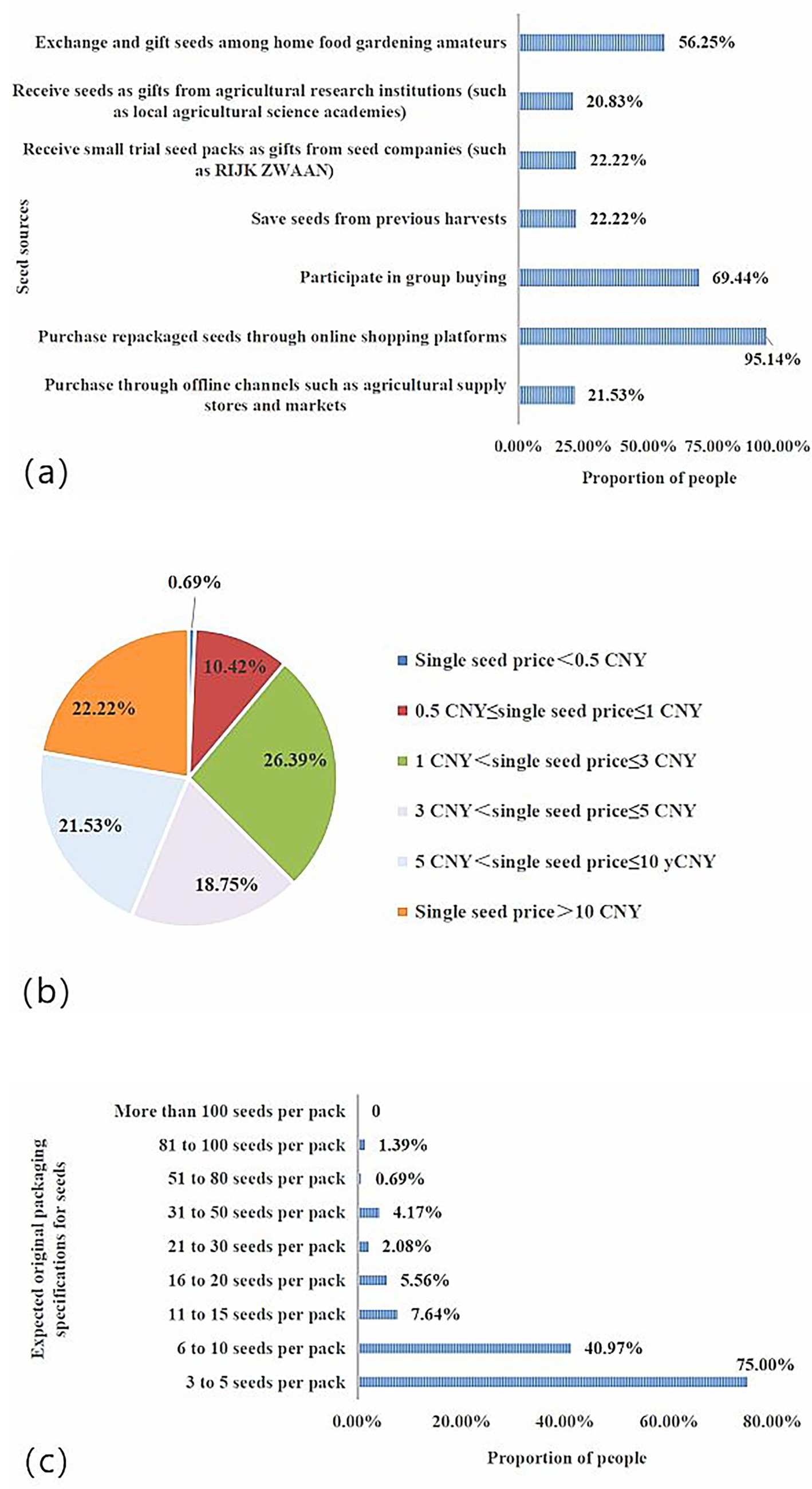

Seeds

Source of seeds

As shown in Figure 7a, 21.53% of HFG tomato growers have purchased tomato seeds through agricultural supply stores and markets; 95.14% have bought tomato seeds through online shopping platforms; 69.44% have obtained tomato seeds through self-organized group purchases; 22.22% have acquired tomato seeds by saving seeds themselves; 22.22% have received trial packs of tomato seeds gifted by seed companies; 20.83% have been given tomato seeds by agricultural research institutions; and 56.25% have obtained tomato seeds through mutual gifting and exchanging.

Figure 7. The sources of tomato seeds owned by Chinese HFG tomato growers (a), distribution of highest prices that Chinese HFG tomato growers are willing to pay for individual tomato seed (b), seed original packaging specifications expected by Chinese HFG tomato grower (c) [Participants could select multiple seed sources and expected seed original packaging specification; therefore, the sum of the percentages in (a,c) does not equal 100%].

The highest price willing to pay for a single tomato seed

As shown in Figure 7b, regarding the highest price HFG tomato growers are willing to pay for a single tomato seed, 0.69% of growers cannot accept a price higher than 0.5 CNY per seed. 10.42% of growers are willing to pay up to 0.5 to 1 CNY per seed. 26.39% of growers can accept a price of up to 1 to 3 CNY per seed. 18.75% of growers are willing to pay up to 3 to 5 CNY per seed. 21.53% of growers can accept a price of up to 5 to 10 CNY per seed. Finally, 22.22% of growers are willing to pay more than 10 CNY per seed.

Expected original seed specifications

As shown in Figure 7c, three quarters of HFG tomato growers prefer seed packets containing 3 to 5 seeds. Additionally, 40.97% of HFG tomato growers are willing to accept packets with 6 to 10 seeds. Smaller percentages are comfortable with larger quantities: 7.64% of HFG tomato growers can accept packets with 11 to 15 seeds, 5.56% with 16 to 20 seeds, and only 2.08% with 21 to 30 seeds. For even larger packets, 4.17% HFG tomato growers can accept 31 to 50 seeds, and a mere 0.69% HFG tomato growers are open to packets with 51 to 80 seeds. Only 1.39% are willing to accept packets with 81 to 100 seeds. Notably, no one prefers packets containing more than 100 seeds.

Acceptance of tomato seed mystery boxes

As shown in Figure 8a, 20.14% of HFG tomato growers would choose seed mystery boxes, while a staggering 79.86% would reject them. According to Figure 8b, among those who embrace seed mystery boxes, 89.66% are drawn to the unknown surprises they offer, and 37.93% are attracted by their affordable prices. In contrast, as depicted in Figure 8c, among those who reject seed mystery boxes, 91.30% prefer to use their limited gardening space efficiently to grow their favorite varieties, and 73.04% are concerned that the seeds in mystery boxes might not perform well, given the abundance of high-quality varieties available.

Figure 8. The acceptance of tomato seed mystery boxes among Chinese HFG tomato growers (a), reasons and proportion of Chinese HFG tomato growers choosing tomato seed mystery boxes (b), and not choosing tomato seed mystery boxes (c) [Participants could select multiple reasons; therefore, the sum of the percentages in (b,c) does not equal 100%].

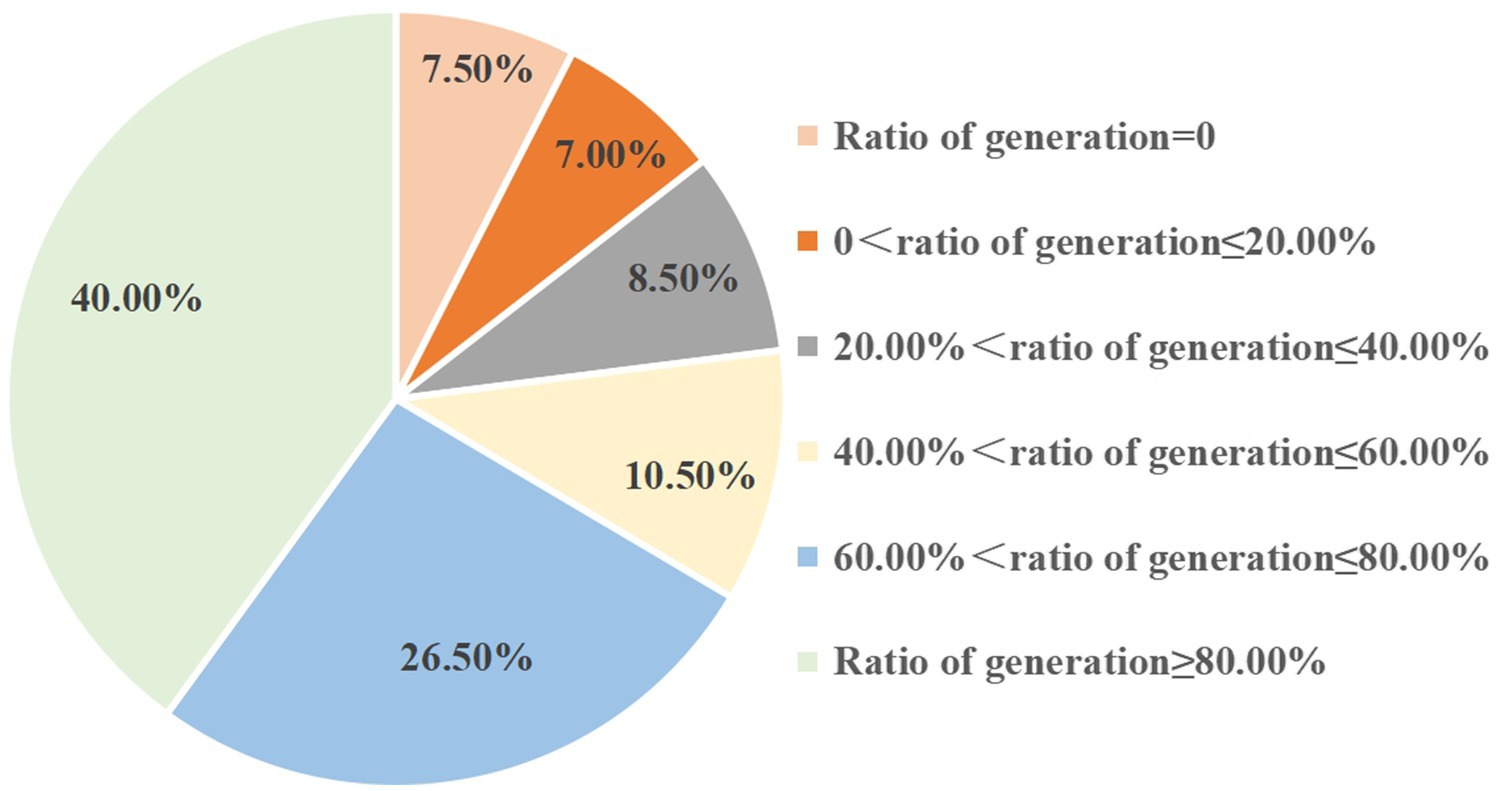

Germination ratio of tomato seeds purchased online

Based on feedback from many HFG tomato growers, some tomato seeds purchased online have low germination rates. Therefore, we conducted a germination test on 400 varieties of tomato seeds we had purchased online. As shown in Figure 9, the results indicate that, among all the varieties, 40.00% of varieties had a germination rate of over 80.00, 26.50% of varieties had a germination rate between 60.00 and 80.00%, 10.50% of varieties had a germination rate between 40.00 and 60.00%, 8.50% of varieties had a germination rate between 20.00 and 40.00%, 7.00% of varieties had a germination rate between 0 and 20.00, and 7.50% of varieties did not germinate.

Discussion

Analysis of population characteristics

As shown in Table 3, the proportion of HFG tomato growers in Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang Provinces accounts for more than 50.00% of the total. These three provinces are all economically developed regions in China. Therefore, We infer that the proportion of residents engaging in HFG in a particular area may be related to the economic development level of that area. Although HFG can provide food and save on household food expenses (Galhena et al., 2013; Algert et al., 2016), many home gardeners invest more in agricultural supplies, labor, and land rent than the economic value of the fruits and vegetables they actually harvest due to poor management or lack of cultivation experience. Thus, HFG in China is more of a recreational activity now. Residents in economically developed areas are relatively affluent and have more disposable income, which is why more people engage in HFG. As shown in Figure 2a, HFG tomato growers in the East China and South China regions account for nearly 70.00% of the total in China. The East China region is economically developed with a large population, hence the proportion of people willing to try HFG reaches 46.53%. The South China region, with its lower latitude and warm climate, includes Baise, Nanning, and Yulin in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, which are major production areas for open-field tomatoes in China during winter (Yang et al., 2023). Due to its unique climatic advantages, the proportion of HFG tomato growers in the South China region also reaches 22.22% of the national total.

As shown in Figure 2b, the majority of HFG tomato growers are aged between 25 and 39, accounting for 84.03% of the total. Most individuals within this age group are already employed and have the ability to invest a certain amount of money in their interests. Additionally, as shown in Figure 7a, online shopping is the primary way for gardeners to purchase tomato seeds, with a high proportion of 95.14%. People aged 25 to 39 (born between 1985 and 1999) have extensive experience in online shopping, which facilitates their engagement in HFG. Furthermore, research has indicated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, unmarried individuals experienced higher levels of mental stress compared to married individuals, and engaging in gardening activities can effectively alleviate this stress (Theodorou et al., 2021). In this study, the groups aged 25 to 29 and 30 to 34 account for 22.92 and 31.94% respectively, with a combined proportion exceeding 50.00%. Currently, due to economic pressures, educational and career development, the proportion of unmarried individuals in these two age groups in China is relatively high, which may partially explain the aforementioned phenomenon.

As shown in Figure 2c, among Chinese HFG tomato growers, the proportion of women is as high as 86.11%. Similarly, studies focusing on residents of Santiago, Chile (Cerda et al., 2022) and Florida, USA (Perez-Lugones et al., 2023) have also indicated that women are the primary participants in local HFG. The process of growing tomatoes involves various agricultural tasks such as seedling cultivation (Maynard et al., 2024), transplanting (Javanmardi and Moradiani, 2017), pruning (Navarrete and Jeannequin, 2000), thinning flowers and fruits (Pathirana et al., 2015), leaf trimming (Appolloni et al., 2023), fertilization and irrigation management (Hasnain et al., 2020; Mukherjee et al., 2023; Vurro et al., 2023), and pest and disease control (Nandi et al., 2018; Diao et al., 2019; Buragohain et al., 2021; Rasool et al., 2021; Tortorici et al., 2022; Yadav et al., 2023), which are time-consuming. It is speculated that among female HFG tomato growers, there is a higher proportion of housewives who have relatively ample and flexible time, allowing them to manage tomato plants in their home gardens more comfortably. Additionally, studies focusing on residents of Italy (Theodorou et al., 2021) and Vermont, USA (Wirkkala et al., 2023) have shown that during the COVID-19 pandemic, women faced greater stress and mental health issues. This may be related to their higher likelihood of unemployment compared to men (Bonga-Bonga et al., 2023), stricter adherence to pandemic restrictions (Ferrín, 2022), and greater concern about the negative health impacts of the virus (Metin et al., 2022). Engaging in gardening activities can significantly reduce stress for women, which might also explain the higher proportion of female home gardeners compared to males (Theodorou et al., 2021).

As shown in Figure 2d, over 80.00% of HFG tomato growers have less than 4 years of experience in tomato cultivation, which coincides with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Theodorou et al., 2021). The rapid increase in the number of HFG tomato growers indicates a broad market potential and significant growth opportunities for this industry in China. In addition to China, countries such as Canada (Mullins et al., 2021), the Philippines (Montefrio, 2020), the United States (Chenarides et al., 2021; Niles et al., 2021), and Indonesia (Aditya and Zakiah, 2022) have also seen a surge in HFG enthusiasts during the pandemic.

Analysis of planting preference

As shown in Figure 3, nearly 90.00% of HFG tomato growers choose to plant tomatoes due to their own or their family’s consumption needs. The post-harvest loss rate of tomatoes is as high as 50.00% (Thole et al., 2020; Yadav et al., 2022). Currently, in order to meet the demands of long-term storage and transportation, commercially available tomatoes often have firmer flesh (Yang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020) and lack flavor (Zhu et al., 2018), which fails to satisfy the consumption needs of many residents today. Some old tomato varieties with excellent flavor have soft flesh that is not suitable for storage and transportation, making them difficult to use in commercial production. However, HFG may become a primary channel for promoting these old varieties in the future. To facilitate storage and transportation, most tomatoes are harvested when they are not fully ripe, resulting in a noticeable difference in flavor and texture compared to fully ripe fruits (Baldwin et al., 1991; Kaur et al., 2023). Additionally, many varieties that perform well are not commercially produced. Therefore, for tomato enthusiasts with high taste standards, growing their own HFG tomatoes becomes a primary choice. Moreover, concerns about pesticide residues in commercially available fruits and vegetables have also become one of the main motivations for Chinese home gardeners to grow tomatoes (Zhang et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2023; Wan et al., 2023).

Spacious private courtyards are ideal places for HFG. However, with urban expansion, the number of courtyards has significantly decreased, and in some places, they have disappeared entirely (Burgin, 2018; Xu et al., 2024). As shown in Figure 4a, less than 20.00% of Chinese home gardeners can grow tomatoes in their own courtyards. Nearly 40.00% and over 30.00% of home gardeners choose to grow tomatoes on rooftops or in self-managed plots or unclaimed wastelands around their residences, respectively. These two sites are relatively open and provide ample planting space. Although most Chinese residences include balconies, their usable area is often too small, and balconies also serve functions such as drying and washing clothes, leaving limited space for home gardening. Therefore, only 25.69% of home gardeners choose to grow tomatoes on balconies. Although terraces offer more space, they are not commonly found in Chinese residences, so only 10.42% of home gardeners choose to grow tomatoes on terraces. For some gardeners with severely limited home cultivation space, renting nearby farmland or greenhouse is also a good alternative, 6.25% of home gardeners choose to grow tomatoes on rented plots.

All groups have chosen to grow cherry tomatoes. Previous research has found that the larger the tomato fruit, the higher the likelihood of blossom end rot (Topcu et al., 2022) and fruit cracking (Khadivi-Khub, 2014). Cherry tomatoes, with their significantly smaller fruit size compared to medium and large fruit tomatoes, have a much lower probability of developing blossom end rot and fruit cracking, thus gaining greater popularity (Figure 5a). Additionally, cherry tomatoes generally have a higher content of soluble solids than medium and large fruit tomatoes, which contributes to their superior flavor (Zhu et al., 2018). Furthermore, their small size makes them convenient for fresh consumption, avoiding the issue of being unable to consume larger fruits in one sitting.

Proper pruning can effectively tap into the yield potential of tomato plants and enhance the quality of tomatoes (Ma et al., 2024). As shown in Table 4, regardless of the variety of tomato being grown, nearly 40.00% of HFG tomato growers choose double-stem pruning. For cherry tomatoes, double-stem pruning is particularly beneficial for root growth and yield increase. For medium and large fruit varieties, plants pruned in this manner have a more rational plant and group structure, with an appropriate leaf-to-fruit ratio. Although the early fruiting rate may not be as high as with single-stem pruning, the fruiting rate in the middle and later stages is significantly higher (Appolloni et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Given ample cultivation space, double-stem pruning may be the most suitable pruning method.

Analysis of issues involved in tomato cultivation and related suggestions

During tomato cultivation, both Chinese (Table 5) and American (Perez-Lugones et al., 2023) HFG tomato growers encounter various pest challenges. Common pests include red spiders, whiteflies, Polyphagotarsonemus latus, leaf miners, and bollworms. Notably, whiteflies serve as the primary vector for the TY virus disease (Dhaliwal et al., 2020). As indicated in Table 5, nearly 40.00% of HFG tomato growers are affected by TY virus. The typical open-air environment for HFG tomato cultivation makes it challenging to effectively manage pests. In contrast, within greenhouse tomato cultivation, whiteflies are prevalent, leaf miners occasionally appear, and the incidence of red spiders and Polyphagotarsonemus latus is relatively low. This may be attributed to the use of insect-proof nets. Therefore, it is recommended to develop small, insect-proof net rooms tailored for one or multiple tomato plants, inspired by the design of mosquito nets. This innovation would provide physical pest control and reduce the reliance on pesticides. Additionally, as Table 5 show, 31.25 and 15.97% of HFG tomato growers, respectively, struggle to accurately identify diseases and pests. To address this issue, online stores specializing in HFG supplies could create instructional videos on tomato diseases and pests, covering identification and control methods. This approach would offer customers a more intuitive learning experience and help establish a loyal customer base.

In addition to pests and diseases, non-ideal growing conditions also pose numerous challenges for HFG enthusiasts. Mature tomato fruits are prone to cracking, and this issue significantly worsens with rainfall, leading to a higher rate of cracked fruits (Yang et al., 2016). As shown in Figure 4a, the main sites for tomato cultivation include rooftops, residential plots, unclaimed wastelands, courtyards, and balconies, accounting for 38.19, 30.56, 19.44, and 10.42%, respectively. Most of these sites lack rain protection facilities, resulting in rain-related fruit cracking issues for two-thirds of home tomato growers (Table 5). We believe that manually constructing small plastic rain shelters could help alleviate this problem.

As shown in Table 5, 18.06% of Chinese HFG tomato growers are troubled by low temperatures and weak light in winter and spring, while 11.81% are troubled by high temperatures in summer. Tomatoes, which originated in tropical regions (Zhang et al., 2019), prefer warm and sunny conditions (Burgin, 2018; Zhang et al., 2022). The optimal daytime and nighttime temperatures for their growth are 25 to 32°C and 15 to 20°C, respectively (Wen et al., 2019). When temperatures exceed 32°C or drop below 12°C, tomato plants grow slowly, and the quality of their fruits significantly declines (Borella et al., 2023). Temperatures above 35°C can greatly reduce the fruit setting rate and hinder the normal color change of tomato fruits (Angmo et al., 2021). When temperatures fall below 5°C, the growth of tomato plants comes to a complete stop; and when temperatures drop to 0°C, the above-ground parts of the plants die quickly (Wang et al., 2020). For most regions in China, it is difficult for autumn-sown tomatoes to survive the winter outdoors. Additionally, previous research has found that high temperatures inhibit the expression of cell wall invertase in tomato cells, preventing the conversion of sucrose, a photosynthetic product, into glucose and fructose. This affects fruit development, leading to issues such as flower and fruit drop, uneven fruit size, and reduced quality (Lou et al., 2025).

Additionally, tomato seedlings are most sensitive to low temperatures (Li et al., 2021). As shown in Table 5, the low temperatures during winter and spring make it difficult for 3.47% of HFG tomato growers to cultivate strong seedlings. In response to the adverse low temperatures of winter and spring, most HFG tomato growers choose to move their tomato plants indoors for cultivation. However, research indicates that the photosynthetic photon flux density in residential environments is 50.00 to 99.00% lower than that outdoors (Cruz and Gómez, 2022). Therefore, indoor light conditions often fail to meet the photosynthetic needs of tomato plants. In light of this, as shown in Figures 10a,b, Chinese HFG tomato growers have tried using various supplementary lighting devices to provide additional light for their tomato plants, in order to reduce the negative impact of low light conditions on the growth and fruit quality of the plants. In addition to indoors, supplementary lighting can also be used appropriately on balconies with poor lighting, especially on lower floors.

Figure 10. Using supplemental lighting to provide extra light for indoor tomato plants (a, b), and preventing birds from pecking mature tomatoes by using netting bags (c, d).

In this study, 5.56% of HFG tomato growers have experienced bird hazard during tomato cultivation (Table 5). To prevent birds from pecking at the tomato fruits, many home gardeners cover the entire cluster of fruits with nets before they mature (Figures 10c,d). In addition to birds, previous studies have found that ripe tomato fruits in home gardens are also prone to being nibbled by small mammals such as squirrels and raccoons (Kortright and Wakefield, 2011).

Due to a lack of knowledge in water and fertilizer management, 1.39% of tomato growers have encountered issues such as waterlogging and seedling burn during tomato cultivation. These individuals are typically new to HFG. If they are young, they can learn cultivation experience through video platforms such as Bilibili. However, if they are middle-aged or elderly, they may not have access to electronic devices or may not be proficient in using them. Therefore, apart from books, it is difficult for them to learn cultivation experience from other sources (Xu et al., 2024). Younger family members in the homes of elderly growers can serve as valuable assistants in learning about tomato cultivation.

Blossom end rot is a common physiological disorder in tomato cultivation, generally believed to be caused by calcium deficiency. It is associated with factors such as tomato genotype (Olle and Williams, 2017), the application of plant growth regulators (Sethi et al., 2024), high concentrations of K+, Na+, Mg2+, and NH4+ in soil solutions or nutrient solutions (Hagassou et al., 2019; Topcu et al., 2022), high light intensity (Hagassou et al., 2019), and high temperatures and drought conditions (Sethi et al., 2024). As shown in Table 5, blossom end rot affects 7.64% of home tomato growers. The occurrence of this disease is unpredictable, and currently, there are no completely effective control methods (Olle and Williams, 2017). For HFG tomato growers aiming for high fruit yields, it is advisable to avoid selecting tomato varieties that are susceptible to blossom end rot. Additionally, during cultivation, it is important to manage scientifically by avoiding excessive application of potassium and ammonium nitrogen fertilizers. Applying soluble calcium sprays to the foliage during the fruit-setting stage can help reduce the incidence of blossom end rot.

As shown in Table 5, it is evident that waterlogging caused by natural disasters such as typhoons has posed challenges for 1.39% of HFG tomato growers. With the acceleration of climate change, the frequency and intensity of heavy rainfall and floods are expected to increase significantly (Wen et al., 2024). In low-lying areas with inadequate drainage, such as some courtyards and private plots, the risk of waterlogging is also on the rise. In addition to waterlogging, potted tomatoes planted on rooftops and balconies can become potential hazards as falling objects during typhoons and other severe weather conditions (Xu et al., 2024). Therefore, it is crucial to anchor these tomato pots in advance during typhoons and other adverse weather conditions.

Current situation and recommendations of tomato seeds used for HFG

Online shopping remains the primary channel for HFG enthusiasts in China (Figure 7a) and the United States (Marwah et al., 2024) to purchase seeds. However, there are issues with the quality of seeds available online. According to surveys, in addition to low germination rates (Figure 9), some sellers have been found to misrepresent their products, such as selling F2, F3, and F4 seeds as F1 hybrid varieties. The demand for seeds in HFG is small, with low transaction amounts and long time spans (from receiving seeds to germination, flowering, fruiting, and maturation, which takes about 3 to 4 months). Moreover, under HFG conditions, tomatoes are generally grown without facilities, and there are many interfering factors during the cultivation and management process. Indeed, some home gardeners lack the necessary knowledge to fully utilize the characteristics of certain varieties, and different varieties do have regional adaptability issues (Romdhane et al., 2023), making it difficult to effectively regulate such problems. Most home gardeners also tend to forgo their rights due to the small transaction amounts, high costs of time for rights protection, and doubts about their own cultivation techniques.

As shown in Figure 7a, 22.22% of HFG tomato growers attempt to obtain tomato seeds through self-saving, which can significantly reduce the cost of seeds (Xu et al., 2024). Due to the high degree of trait segregation in the offspring of F1 hybrid varieties (Ohyama et al., 2023), HFG tomato growers typically do not choose hybrid varieties for seed saving. On the contrary, heirloom varieties possess higher genetic stability, making them the preferred choice for most home gardeners to save seeds (Jordan, 2007). The TY virus poses a significant threat to tomatoes (Li et al., 2022). Under HFG conditions, it is difficult to establish effective pest defense barriers, leading to the easy infestation of tomato plants by whiteflies and other pests, resulting in the widespread spread of TY virus (Guo et al., 2019; El-Sappah et al., 2022). Currently, through interspecific hybridization, many hybrid cultivated tomatoes have successfully introduced TY virus resistance genes from wild tomato relatives, effectively resisting the threat of TY virus (Marchant et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2020). However, heirloom varieties, due to their ability to be self-saved and low commercial value, lack the motivation for research institutions and seed companies to develop new varieties. This also results in most heirloom tomato varieties lacking TY virus resistance genes, performing poorly in HFG environments. Additionally, heirlooms have drawbacks such as unstable flavor, irregular shape, and susceptibility to cracking (Joseph et al., 2017), leading many HFG tomato growers to gradually reject heirloom tomato varieties. Currently, many heirloom tomato varieties are gradually disappearing (Xu et al., 2024), with only a few remaining in HFG practitioners or enthusiasts. Therefore, it is highly recommended that local agricultural departments or public welfare organizations establish regional heirloom exchange networks among home growers. Besides reducing the seed cost for HFG tomato growers, heirloom varieties also have certain strategic value. In the event of seed production crises (such as difficulty in seed production due to wars), superior heirlooms can effectively reduce difficulties in seed production, and avoid the troubles brought by trait segregation in the offspring of F1 hybrid varieties. Tomatoes hold a significant position in Chinese diet (Ji et al., 2019; Qin and Hu, 2023). Therefore, we believes that it is important to be prepared for potential crises, and beyond mere economic interests, developing heirloom tomato varieties that are highly resistant, prolific, flavorful, and adaptable to home cultivation environments (such as tolerance to weak light and cracking) is also a direction worth exploring. In the future, if there are events that may pose a long-term threat to the stability of the fresh fruit and vegetable supply chain (such as major public health emergencies or wars), government departments can distribute previously developed heirloom tomato seeds and reserved agricultural supplies (such as cultivation containers, fertilizers, pesticides, fruit-setting agents, etc.) to residents, along with tomato planting guides in the form of short videos. This will allow residents to cultivate and harvest tomatoes in their homes, enriching their diets and reducing pressure on the fresh fruit and vegetable supply chain.

In recent years, the improvement in breeding efficiency has led to a continuous emergence of new tomato varieties. In commercial production, competition among these varieties has become increasingly fierce. Due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, HFG has become popular among some Chinese residents (Xu et al., 2024). Moreover, currently, the price of high-quality Chinese tomato seeds, such as Qingxia 66, typically does not exceed 1 CNY per seed in their original packaging. According to Figure 7b, 88.89% of HFG tomato growers are willing to accept a price of over 1 CNY per seed, more than 60.00% can accept a price of over 3 CNY per seed, over 40.00% can accept a price of over 5 CNY per seed, and even more than 20.00% can accept a price of over 10 CNY per seed. In light of the seed specifications preferred by HFG tomato growers as shown in Figure 7c, it is suggested that, in addition to the conventional packaging used for commercial production, seed companies could consider developing small packaging suitable for HFG, with each packet containing 3 to 10 seeds. The price of single seed in these small packages could be significantly higher than that of conventional packaging. Although the seed usage in HFG cannot be compared with commercial production, the profit margin in this emerging market is quite substantial, and seed companies should pay attention to it.

Compared to expensive seeds that can still be purchased, some high-quality tomato varieties are difficult to obtain due to information barriers and sales restrictions. Typical varieties include cherry tomato varieties such as Gourami, Chromis, Suncery, Operino, Ternetto, and Florantino, which are bred by Rijk Zwaan, as well as Beishi No. 1, developed by the Modern Agricultural Research Institute of Peking University.

Currently, there is a wide variety of tomato cultivars available on the market (Capel et al., 2017), however, most HFG tomato growers lack trustworthy reference information when selecting a variety. In most cases, their knowledge of new varieties is limited to information found on lifestyle-sharing platforms like RED and Weibo, in gardening enthusiast groups, and in product descriptions on online shopping platforms. However, each variety has regional adaptability, and due to environmental differences, the cultivation performance of different varieties can vary significantly, even drastically (Romdhane et al., 2023). Therefore, the process of growing new tomato varieties, for HFG tomato growers, is conducting variety comparison trials under home cultivation conditions. Unfortunately, due to the lack of professional background knowledge, most amateur tomato growers are unable to transform these results into credible written or video materials.

As illustrated in Figure 8a, approximately one-fifth of HFG tomato growers embrace tomato seed mystery boxes. Among this group, nearly 90.00% are drawn to purchasing tomato seed mystery boxes due to the thrill of surprise, as depicted in Figure 8b. The burgeoning mystery box economy thrives by tapping into consumer psychology. In today’s society, the quest for individuality is intensifying, and mystery boxes perfectly cater to this desire. Furthermore, seed mystery boxes alleviate the decision-making stress for those who struggle with choice overload. When home tomato growers purchase tomato seed mystery boxes and successfully cultivate unique tomato fruits, the unexpected reward they experience fuels their anticipation and eagerness for the next seed mystery box, prompting repeat purchases.

Additionally, as shown in Figure 8a, nearly four-fifths of home tomato growers have rejected seed mystery boxes. Among these individuals, over 90.00% prefer to effectively utilize their limited cultivation space by planting their favorite varieties, as indicated in Figure 8c. It can be inferred that the acceptance of seed mystery boxes might increase if there is ample cultivation space. However, currently, insufficient cultivation space is one of the main challenges faced by HFG, especially in densely populated mega-cities. For ordinary residents in these cities, HFG has become a kind of luxury (Xu et al., 2024). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 8c, more than 70.00% of people reject seed mystery boxes due to concerns about their cultivation performance. Unlike other mystery box products that provide immediate feedback, the cultivation cycle of tomatoes from sowing to the maturity of the first fruit cluster typically lasts 3 to 4 months. During this period, growers invest significant effort. If the cultivation performance is poor, it can easily undermine their confidence, leading them to quickly abandon seed mystery boxes.

Future prospects

The plants in home gardens offer both aesthetic appeal and edibility, making them more functional than purely ornamental plants. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many HFG enthusiasts have heightened their awareness of potential crises. As a result, they have begun to decrease the proportion of ornamental plants and increase the cultivation of vegetables (such as tomatoes, cucumbers, and leafy greens) and fruits (such as strawberries and blueberries) (Perez-Lugones et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2024). Regarding the emerging consumer trend of HFG, the Chinese government has yet to give it significant attention. In the realm of scientific research, the absence of dedicated funding hinders the development of specialized plant varieties and the study of related cultivation techniques (Xu et al., 2024).

Cultivating tomatoes under home conditions is significantly different from traditional commercial production. Currently, the development of supporting products for home tomato cultivation in China is still in its infancy. In addition to the aforementioned suggestions, we proposes the following recommendations for home tomato cultivation: (1) Draw inspiration from commercial production models to develop small-scale cultivation racks suitable for HFG. These racks should facilitate the lowering of stems and prevent operational difficulties caused by excessive height of potted tomato plants in the later stages; (2) When making seed mystery boxes, horticultural merchants can indicate the approximate range of tomato varieties included in the mystery box. This prevents it from becoming a product with an unlimited range and avoids using it primarily as a channel for merchants to dispose of unsold seeds and manage inventory risks; (3) For beginners, horticultural merchants can consider developing planting kits that include tomato seeds, seedling pots, substrates, cultivation containers, commonly used pesticides, fertilizers, fertilization and pesticide application devices, and cultivation racks. These kits should also come with technical guidance videos for the entire process from sowing to harvesting (consumers can watch by scanning a QR code), to enhance the planting experience for beginners.

Conclusion

This study investigated 1,296 HFG tomato growers through a questionnaire and conducts germination tests on 400 varieties of tomato seeds purchased online. The results indicate that among all provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China, the top three regions with the highest proportion of HFG tomato growers are Guangdong Province, Jiangsu Province, and Zhejiang Province. In the seven major geographical regions of China, the East China region has the most HFG tomato growers. The primary demographic for home tomato cultivation is individuals aged 25 to 39, with females being the predominant group. Over 80.00% of HFG tomato growers have less than four years of experience in tomato cultivation. A staggering 87.50% of HFG tomato growers choose to grow tomatoes because they or their family members enjoy eating them, and they can grow varieties not available in the market. Additionally, home-grown tomatoes are perceived to be more mature and safer. The main locations for growing tomatoes are rooftops, residential peripheral plots, or unclaimed wastelands. Cherry tomatoes are the primary choice, and double-stem pruning is commonly used. The most significant disease and pest affecting home tomato cultivation are TY virus and red spider mites, respectively, while fruit splitting during the rainy season is the most common issue. Over 90.00% of HFG tomato growers have purchased tomato seeds online. Regarding the maximum price they are willing to pay for a single tomato seed, 22.22% of HFG tomato growers can accept a price higher than 10 CNY per seed. The desired seed specifications are 3 to 5 seeds and 6 to 10 seeds per package. Nearly 80.00% of HFG tomato growers refuse to purchase seed mystery boxes. The germination rate of purchased tomato seeds is low, with only 40.00% of the varieties achieving a germination rate of over 80.00%. Overall, tomatoes are quite well-liked in HFG in China and have bright future possibilities. However, problems including uneven seed quality, pests and diseases still need to be resolved.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the (patients/ participants OR patients/participants legal guardian/next of kin) was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JX: Formal analysis, Visualization, Resources, Project administration, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. SL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HQ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. YW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. XG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. TL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JC: Data curation, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Taizhou Science and Technology Project (25nya10); Taizhou Agricultural Science and Technology Project (202202 and 202412); Beijing Leisure Agriculture Innovation Consortium (BAIC09-2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the 1296 HFG tomato growers who participated in this survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aditya, R. B., and Zakiah, A. (2022). Practical reflection and benefits of making a food garden at home during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Food Stud. 11, 85–97. doi: 10.7455/ijfs/11.1.2022.a8

Algert, S. J., Baameur, A., Diekmann, L. O., Gray, L., and Ortiz, D. (2016). Vegetable output, cost savings, and nutritional value of low-income families’ home gardens in San Jose, CA. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 11, 328–336. doi: 10.1080/19320248.2015.1128866

Al-Mayahi, A., Al-Ismaily, S., Gibreel, T., Kacimov, A., and Al-Maktoumi, A. (2019). Home gardening in Muscat, Oman: gardeners’ practices, perceptions and motivations. Urban For. Urban Green. 38, 286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2019.01.011

Angmo, P., Phuntsog, N., Namgail, D., Chaurasia, O. P., and Stobdan, T. (2021). Effect of shading and high temperature amplitude in greenhouse on growth, photosynthesis, yield and phenolic contents of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum mill.). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 27, 1539–1546. doi: 10.1007/s12298-021-01032-z

Appolloni, E., Paucek, I., Pennisi, G., Manfrini, L., Gabarrell, X., Gianquinto, G., et al. (2023). Winter greenhouse tomato cultivation: matching leaf pruning and supplementary lighting for improved yield and precocity. Agronomy 13:671. doi: 10.3390/agronomy13030671

Baldwin, E. A., Nisperos-Carriedo, M. O., and Moshonas, M. G. (1991). Quantitative analysis of flavor and other volatiles and for certain constituents of two tomato cultivars during ripening. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 116, 265–269. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.116.2.265

Bar-Nahum, Z., Finkelshtain, I., Ihle, R., and Rubin, O. D. (2020). Effects of violent political conflict on the supply, demand and fragmentation of fresh food markets. Food Secur. 12, 503–515. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01025-y

Bonga-Bonga, L., Molemohi, T., and Kirsten, F. (2023). The role of personal characteristics in shaping gender-biased job losses during the COVID-19 pandemic: the case of South Africa. Sustainability 15:6933. doi: 10.3390/su15086933

Borella, M., Baghdadi, A., Bertoldo, G., Della Lucia, M. C., Chiodi, C., Celletti, S., et al. (2023). Transcriptomic and physiological approaches to decipher cold stress mitigation exerted by brown-seaweed extract application in tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1232421. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1232421

Buragohain, P., Saikia, D. K., Sotelo-Cardona, P., and Srinivasan, R. (2021). Development and validation of an integrated pest management strategy against the invasive south American tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta in South India. Crop Prot. 139:105348. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105348

Burgin, S. (2018). ‘Back to the future’? Urban backyards and food self-sufficiency. Land Use Policy 78, 29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.06.012

Capel, C., Yuste-Lisbona, F. J., López-Casado, G., Angosto, T., Cuartero, J., Lozano, R., et al. (2017). Multi-environment QTL mapping reveals genetic architecture of fruit cracking in a tomato RIL Solanum lycopersicum × S. pimpinellifolium population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 130, 213–222. doi: 10.1007/s00122-016-2809-9

Cattivelli, V. (2022). The contribution of urban garden cultivation to food self-sufficiency in areas at risk of food desertification during the COVID-19 pandemic. Land Use Policy 120:106215. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106215

Cerda, C., Guenat, S., Egerer, M., and Fischer, L. K. (2022). Home food gardening: benefits and barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Santiago, Chile. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 6:841386. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2022.841386

Chalmin-Pui, L. S., Griffiths, A., Roe, J., Heaton, T., and Cameron, R. (2021). Why garden? – attitudes and the perceived health benefits of home gardening. Cities 112:103118. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2021.103118

Chenarides, L., Grebitus, C., Lusk, J. L., and Printezis, I. (2021). Who practices urban agriculture? An empirical analysis of participation before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Agribusiness 37, 142–159. doi: 10.1002/agr.21675

Clarke, L. W., Li, L., Jenerette, G. D., and Yu, Z. (2014). Drivers of plant biodiversity and ecosystem service production in home gardens across the Beijing municipality of China. Urban Ecosyst. 17, 741–760. doi: 10.1007/s11252-014-0351-6

Corley, J., Okely, J. A., Taylor, A. M., Page, D., Welstead, M., Skarabela, B., et al. (2021). Home garden use during COVID-19: associations with physical and mental wellbeing in older adults. J. Environ. Psychol. 73:101545. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101545

Cruz, S., and Gómez, C. (2022). Effects of daily light integral on compact tomato plants grown for indoor gardening. Agronomy 12:1704. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12071704

Deng, T., van den Berg, M., Heerink, N., Cui, H., Tan, F., and Fan, S. (2023). Can homestead gardens improve rural households' vegetable consumption? Evidence from three provinces in China. Agribusiness 39, 1578–1594. doi: 10.1002/agr.21855

Dhaliwal, M. S., Jindal, S. K., Sharma, A., and Prasanna, H. C. (2020). Tomato yellow leaf curl virus disease of tomato and its management through resistance breeding: a review. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 95, 425–444. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2019.1691060

Diao, Y., Larsen, M. M., Kamvar, Z. N., Zhang, C., Li, S., Wang, W., et al. (2019). Genetic differentiation and clonal expansion of Chinese Botrytis cinerea populations from tomato and other crops in China. Phytopathology 110, 428–439. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-18-0347-R

El-Sappah, A., Qi, S., Soaud, S., Huang, Q., Saleh, A., and Abourehab, M. (2022). Natural resistance of tomato plants to tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Front. Plant Sci. 13:1081549. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1081549

Ferrín, M. (2022). Reassessing gender differences in COVID-19 risk perception and behavior. Soc. Sci. Q. 103, 31–41. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13116

Galhena, D. H., Freed, R., and Maredia, K. M. (2013). Home gardens: a promising approach to enhance household food security and wellbeing. Agric. Food Secur. 2:8. doi: 10.1186/2048-7010-2-8

Gao, X., Yang, F., Yan, Z., Zhao, J., Li, S., Nghiem, L., et al. (2022). Humification and maturation of kitchen waste during indoor composting by individual households. Sci. Total Environ. 814:152509. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152509

Grebitus, C. (2021). Small-scale urban agriculture: drivers of growing produce at home and in community gardens in Detroit. PLoS One 16:e256913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256913

Guo, Q., Shu, Y., Liu, C., Chi, Y., Liu, Y., Shu, Y.-N., et al. (2019). Transovarial transmission of tomato yellow leaf curl virus by seven species of the Bemisia tabaci complex indigenous to China: not all whiteflies are the same. Virology 531, 240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2019.03.009

Ha, H. T. N., Van Tai, N., and Thuy, N. M. (2021). Physicochemical characteristics and bioactive compounds of new black cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) varieties grown in Vietnam. Plants 10:2134. doi: 10.3390/plants10102134

Hagassou, D., Francia, E., Ronga, D., and Buti, M. (2019). Blossom end-rot in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.): a multi-disciplinary overview of inducing factors and control strategies. Sci. Hortic. 249, 49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2019.01.042

Han, S., Jia, L., Liu, Z., Fuyuki, K., Imoto, T., and Zhao, X. (2024a). Food system under COVID-19 lockdown in Shanghai: problems and countermeasures. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1368745. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1368745

Han, Y., Lu, L., Wang, L., Liu, Z., Huang, P., Chen, S., et al. (2024b). In-situ straw return, combined with plastic film use, influences soil properties and tomato quality and yield in greenhouse conditions. Agric. Commun. 2:100028. doi: 10.1016/j.agrcom.2024.100028

Hasnain, M., Chen, J., Ahmed, N., Memon, S., Wang, L., Wang, Y., et al. (2020). The effects of fertilizer type and application time on soil properties, plant traits, yield and quality of tomato. Sustainability 12:9065. doi: 10.3390/su12219065

Head, L., Muir, P., and Hampel, E. (2004). Australian backyard gardens and the journey of migration*. Geogr. Rev. 94, 326–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1931-0846.2004.tb00176.x

Hossain, M. N., Islam, M. S., Abdullah, S. M., Alam, S. M., and Huque, R. (2023). Vegetables and fruits retailers in two urban areas of Bangladesh: disruption due to COVID-19 and implications for NCDs. PLoS One 18:e280188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280188

Javanmardi, J., and Moradiani, M. (2017). Tomato transplant production method affects plant development and field performance. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 23, 31–41. doi: 10.1080/19315260.2016.1169240

Jensen, P. D., and Orfila, C. (2021). Mapping the production-consumption gap of an urban food system: an empirical case study of food security and resilience. Food Secur. 13, 551–570. doi: 10.1007/s12571-021-01142-2

Ji, X., Li, J., Dong, B., Zhang, H., Zhang, S., and Qiao, K. (2019). Evaluation of fluopyram for southern root-knot nematode management in tomato production in China. Crop Prot. 122, 84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.04.028

Jordan, J. A. (2007). The heirloom tomato as cultural object: investigating taste and space. Sociol. Ruralis 47, 20–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2007.00424.x

Joseph, H., Nink, E., McCarthy, A., Messer, E., and Cash, S. B. (2017). The heirloom tomato is ‘in’. Does it matter how it tastes? Food Cult. Soc. 20, 257–280. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2017.1305828

Kaur, G., Abugu, M., and Tieman, D. (2023). The dissection of tomato flavor: biochemistry, genetics, and omics. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1144113. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1144113

Khadivi-Khub, A. (2014). Physiological and genetic factors influencing fruit cracking. Acta Physiol. Plant. 37:1718. doi: 10.1007/s11738-014-1718-2

Khan, M. M., Akram, M. T., Janke, R., Qadri, R. W., Al-Sadi, A. M., Qadri, R. W. K., et al. (2020). Urban horticulture for food secure cities through and beyond COVID-19. Sustainability 12:9592. doi: 10.3390/su12229592

Kortright, R., and Wakefield, S. (2011). Edible backyards: a qualitative study of household food growing and its contributions to food security. Agric. Hum. Values 28, 39–53. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9254-1

Kpadé, C. P., Bélanger, M., Laplante, C., Lambert, C., and Bocoum, I. (2023). Food insecurity, coping strategies, and resilience of agricultural cooperative members during COVID-19 in West Africa. Agric. Food Secur. 12:38. doi: 10.1186/s40066-023-00440-6

Lal, R. (2020). Home gardening and urban agriculture for advancing food and nutritional security in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Food Secur. 12, 871–876. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01058-3

Li, F., Qiao, R., Yang, X., Gong, P., and Zhou, X. (2022). Occurrence, distribution, and management of tomato yellow leaf curl virus in China. Phytopathol. Res. 4:28. doi: 10.1186/s42483-022-00133-1

Li, R., Sun, S., Wang, H., Wang, K., Yu, H., Zhou, Z., et al. (2020). FIS1 encodes a GA2-oxidase that regulates fruit firmness in tomato. Nat. Commun. 11:5844. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19705-w