- 1School of Karst Science, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, China

- 2Guizhou Provincial Key Laboratory, Guiyang, China

The expansion of non-grain cultivated land poses challenges to sustainable land use, particularly in fragile karst mountainous areas. This study focuses on Guizhou Province, which has the most extensive karst landforms, to investigate the spatial patterns and driving mechanisms of NGPCL in karst plateau mountainous areas. Based on the difficulty of restoration and cropping attributes, non-grain cultivated land was classified into four categories: planted non-grain crops (PNGC), unplanted cultivated land (UCL), engineering recoverable (ENR), and immediately recoverable (IMR). Using spatial autocorrelation, hotspot analysis, and the geographic detector method, the spatial distribution and clustering patterns of each type were revealed, and their driving factors were explored. The results show that: (1) non-grain cultivated land accounts for 27.78% of total cultivated land in Guizhou, with ENR having the largest area and readily recoverable land the smallest; the conversion of cultivated land to forest and orchard land is significant; (2) non-grain cultivated land exhibits strong spatial correlation and clustering, with hotspots in the central and northeastern regions, cold spots in the southeast regions, and no significant clustering elsewhere; (3) among multiple driving factors, distance to residential areas is the main factor influencing the spatial distribution of non-grain cultivated land, with different dominant drivers for each type, though some internal correlations exist. This study provides differentiated regional references and policy implications for sustainable agriculture and land use in karst plateau mountainous areas.

1 Introduction

Grain production underpins social stability and sustainable development across the globe. As the bedrock of national well-being, food security is paramount to the long-term stability and security of nations (Zuo et al., 2023; Cottrell et al., 2018; UNICEF, 2021). Globally, the conversion of cropland to non-grain uses represents a pervasive challenge amid ongoing agricultural transformation. This trend is exemplified by widespread cropland abandonment in Japan (Osawa et al., 2016), the large-scale re-purposing of farmland in West Java, Indonesia (Maryati et al., 2018) and the expansion of non-grain production in China’s Yangtze River Delta, which exerts comprehensive impacts on ecosystem services (Wang et al., 2026). Collectively, these shifts undermine regional food security. Echoing a global trend, the safeguarding of China’s cropland and food security is fundamental to sustainable socioeconomic development and constitutes a paramount national strategic imperative. The Third National Land Survey Main Data Bulletin shows that from 2009 to 2019, 7.47 million hectares of cultivated land were converted to forest land and 4.2 million hectares to garden land, indicating a clear non-grain production of cultivated land (NGPCL) phenomenon. According to field survey data, NGPCL in China is gradually expanding. Preliminary estimates suggest that approximately 27% of cultivated land is currently used for non-agricultural purposes (Xiang, 2020). This growing trend poses a significant threat to national food security. Guizhou Province shoulders a critical dual mandate: ensuring regional food security and maintaining the ecological stability of the upper Yangtze and Pearl River basins (Chen et al., 2024). This challenge is exacerbated by its uniquely fragmented cultivated land resources, which are scarce, shallow in soil depth, and possess weak water and nutrient retention capacity (Wang et al., 2004; Dx, 1997). As a quintessential example of China’s southwestern karst mountains, the trajectory of its land use change serves as a vital reference for analogous regions. However, this important issue remains a notable gap in the current literature. Constrained by karst landforms, high-quality cultivated land in Guizhou Province is inherently scarce. This scarcity is increasingly challenged by non-grain production, driven by urbanization-induced farmland loss (Xiao et al., 2017; Bren D’amour et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2020; Chen, 2012; Seto and Ramankutty, 2016), rural labor outflow, and agricultural structural adjustments (Liang et al., 2023). The expansion of non-grain cropping not only reduces the area available for staple crops but also exacerbates rocky desertification and disrupts fragile ecosystems (Su B. et al., 2018; El Kateb et al., 2013; Martínez-Paz et al., 2019), posing a dual threat to both food security and ecological integrity. Moreover, the cultivation of forestry and fruit-based cash crops on cultivated land, coupled with farmland abandonment, compromises the long-term sustainability of food production. Furthermore, the excessive use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers, along with degradation of the tillage layer, has intensified agricultural non-point source pollution (Bryan et al., 2018), further jeopardizing the stability and sustainability of food production. Given the increasingly prominent NGPCL trend, society is seeking scientific governance methods to address this issue (Lewis et al., 2009; Su et al., 2022).

In recent years, as NGPCL has gained attention from various sectors of society, academic interest has grown, leading to notable progress in the field. In defining its concept and connotation, academia widely recognizes that driven by the rise of cash crops and new export opportunities for fruits and vegetables, farmers have adjusted land use by converting cultivated land to these more profitable alternatives. This has led to the emergence of NGPCL (Li et al., 2021; Su et al., 2020), which, however, remains fundamentally an agricultural use (Ran et al., 2022; Jarzebski et al., 2020). Research on NGPCL primarily focuses on understanding driving mechanisms (Ran et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2023; Belay and Mengistu, 2019; Plieninger et al., 2016), identifying countermeasures (Lu et al., 2024; Dong et al., 2024), and exploring its temporal and spatial evolution as well as differentiation characteristics (Su et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2024; Zhang D. et al., 2023; Zhang Z. et al., 2023; Miao et al., 2021). In terms of research scope, most studies have been conducted at the national (Sun et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2022), provincial (Jiang et al., 2024; Bo et al., 2025; Mann et al., 2010), and municipal or county levels (Li et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2022b) Commonly used research methods include random forest models (Jie et al., 2024), regression analysis (Cheng et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023), spatial lag models (Ren et al., 2023), geographic detectors (Zhang Z. et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2022a), geographically weighted regression (Xu et al., 2025), and spatial autocorrelation analysis (Zhao et al., 2023). From the perspective of driving mechanisms, economic factors (such as cost–benefit considerations), institutional factors (such as land transfer dynamics), and geographical factors (including resource endowment and location) influence the extent of non-grain cultivated land to varying degrees (Zhao et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2022a; Su G. et al., 2018). The impacts of NGPCL are understood through a multifaceted lens: while strategic NGPCL can enhance agricultural profitability, increase farmer incomes, and optimize the agricultural structure (Do et al., 2020; Gellrich et al., 2007; Anselin, 2002), it concurrently poses significant threats. These include the displacement of prime farmland and consequent food insecurity, ecological degradation such as biodiversity loss and increased fragility, and socio-economic imbalances in regional development and land use efficiency (Long et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024). In response, recent studies have proposed targeted countermeasures. For instance, Zhang et al. (2024) advocated for nature-based land restoration that integrates land quality with production suitability to mitigate ecological threats. Similarly, Song et al. (2025) demonstrated that increasing agricultural labor input and improving mechanization can curb the expansion of NGPCL, thereby safeguarding food security.

Although non-grain land use has been widely discussed in the literature, existing studies still exhibit notable limitations in theoretical perspectives and regional applicability. First, they have primarily focused on major grain-producing regions and economically developed areas (Hu et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023), neglecting the ecologically fragile karst regions of southwest China. Second, few studies have analyzed the characteristics of NGPCL at the provincial scale using high-resolution remote sensing-derived land use data. This scarcity is particularly pronounced in karst mountainous areas, hindering the precise elucidation of non-grainification driving mechanisms under complex topographic conditions. Therefore, this paper classifies cultivated land according to its actual planting status and the difficulty of restoring non-grain cultivated land to grain production. Compared with flat terrain and plains or hilly regions with better resource conditions, karst areas exhibit complex landforms, severe rocky desertification and soil erosion (Xiaoqing et al., 2014), and a lack of high-quality cultivated land resources (Wang et al., 2020). In regions with poor resource endowments, phenomena of non-grain production such as land abandonment or agricultural structural adjustment are more likely to occur (Su G. et al., 2018; Subedi et al., 2021), and the driving mechanisms exhibit pronounced geomorphic dependence and regional specificity.

Therefore, this study focuses on the mountainous region of Guizhou (Wang et al., 2004; Dx, 1997), an area with the most widespread karst topography. The core objectives are to address the weaknesses in existing research on NGPCL amid the complex geomorphology and unique socioeconomic context of Guizhou’s mountainous regions, identify the spatial agglomeration patterns and hotspots of different NGPCL types, systematically dissect the driving mechanisms of NGPCL induced by topographic constraints, natural conditions, and socioeconomic factors, reveal the dominant driving pathways of NGPCL, and provide a scientific basis for food security and cultivated land conservation in karst mountainous areas.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study area

Located in the heart of southwestern China on the eastern Yungui Plateau (Figure 1), Guizhou Province (103°36′–109°35′E, 24°37′–29°13′N) encompasses 176,167 km2. The province borders Hunan, Guangxi, Yunnan, and Sichuan, as well as Chongqing, and sits at the strategic watershed of the Yangtze and Pearl River Basins. Its topography is high in the west and low in the east, characterized by rolling mountains and extensively developed karst landforms that cover nearly 70% of its area, making it a representative karst region in southern China. This complex terrain has resulted in poor-quality, fragmented cultivated land and severe rocky desertification, rendering land scarce, inefficiently utilized, and agricultural mechanization difficult. Consequently, between the second and third national land surveys, the province lost 109,038 hectares of cultivated land, exacerbating the prominent issue of non-grain cultivation.

Figure 1. Geographical location and topography of Guizhou Province; L denotes low elevation areas; H denotes high elevation areas; Digital Elevation Model (DEM) is expressed in meters (m).

2.2 Data sources

The 2022 land use data of Guizhou Province, derived from remote sensing interpretation, were obtained from the Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China (accuracy is 0.5 meters). The 2022 population density data were obtained from LandScan,1 which provides population spatial distribution data at a 1 km resolution. The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data were obtained from the official USGS website.2 The 2022 precipitation data were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center.3

2.3 The definition of NGPCL

According to The Technical Regulations of the Third National Land Survey of China, non-grain cultivated land is categorized into four types based on planting attributes and restoration requirements: planted non-grain crops (PNGC), unplanted cultivated land (UCL), engineering recoverable (ENR), and immediately recoverable (IMR). PNGC refers to land used for cultivating non-grain crops such as vegetables, cotton, oil-bearing crops, sugar crops, forage, and tobacco. UCL denotes uncultivated land, not designated as fallow, that can be restored to cultivation without intervention. ENR refers to cultivated land that has been converted to forest, orchard, grassland, or other agricultural uses and requires engineering measures to be restored to cultivation. IMR refers to cultivated land with an intact topsoil that is currently used as forest, orchard, grassland, or other agricultural land and can be readily restored to cultivation after clearing.

2.4 Research framework

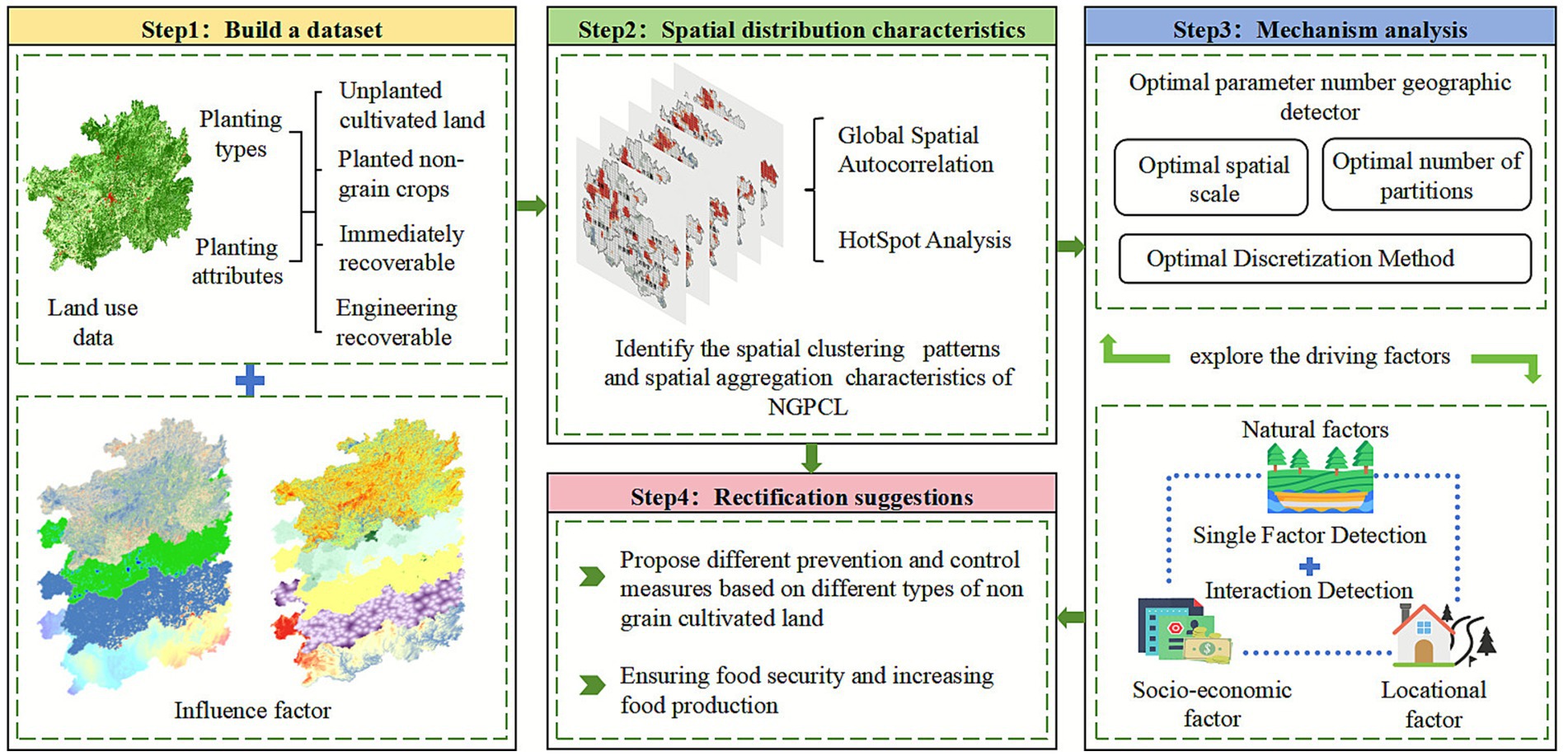

To reveal the spatial distribution characteristics of non-grain cultivated land and investigate its driving mechanisms, we constructed a framework as follows. Step 1: Build a dataset of non-grain cultivated land, combine it with land use data, and classify non-grain cultivated land into four types based on restoration difficulty and cropping attributes: PNGC, UCL, ENR, and IMR. Land use data provide information on the spatial distribution of cultivated land and support the identification of different types of non-grain cultivated land. Through classification and processing, these data help clarify the spatial distribution characteristics of various types of non-grain cultivated land. Step 2: The spatial differentiation patterns of overall non-grain cultivated land and its various types in Guizhou Province are analyzed using global spatial autocorrelation and hotspot analysis. Spatial autocorrelation analysis was used to identify the spatial clustering patterns of non-grain cultivated land, while hotspot analysis further revealed the specific characteristics of these clusters. Step 3: A quantitative analysis of the influence of various factors (e.g., topography, precipitation, distance from settlements) on the distribution of NGPCL was conducted using the Optimal Parameter Geographical Detector model. Interaction detection was also employed to explore the combined effects of multiple factors. This approach reveals the driving forces behind spatial distribution and helps identify key influencing factors. Step 4: Propose governance recommendations for the prevention and control of NGPCL (see Figure 2).

2.5 Research method

2.5.1 Spatial autocorrelation analysis

To characterize the spatial patterns of NGPCL in Guizhou’s karst mountainous areas, we employed spatial autocorrelation analysis (Sridharan et al., 2007). Given the contiguous, boundary-defined land parcels in the study area, we first constructed and standardized a Rook contiguity spatial weight matrix. We then calculated the Global Moran’s I to quantify the overall spatial autocorrelation of NGPCL across the province, with its statistical significance confirmed via a Z-test. The formula is as follows (Equation 1):

In the formula: n represents the number of spatial units; xᵢ and xⱼ denote the attribute values in units i and j, respectively; x represents the mean value of all units; and wᵢⱼ is the spatial weight matrix. The value of Moran’s I (I∈[−1, 1]) indicates the nature of spatial autocorrelation: I > 0 suggests a clustering trend and positive spatial correlation; I < 0 indicates a dispersion trend and negative spatial correlation; and I = 0 denotes a random distribution with no spatial correlation.

2.5.2 Spatial hotspot analysis

To identify local clusters of high (hotspots) and low (coldspots) values of NGPCL, we performed a hotspot analysis using the Getis-Ord statistic ( ) statistic (Feng et al., 2018). This approach reveals the internal spatial heterogeneity of NGPCL and provides a geographic basis for targeted management. For this analysis, the study area was divided into a 10 km × 10 km grid. We then calculated the NGPCL area within each grid cell and applied the statistic to identify statistically significant hotspots and coldspots. The formula is as follows (Equations 2, 3):

In the formula, represents the clustering index of unit i; wᵢⱼ is the spatial weight between units i and j; xj denotes the area of non-grain cultivated land in unit j; and n is the total number of spatial units. Z is the normalized value, with is the expected value and Var ( ) is the variance. When Z > 0 and the p-value is significant, it indicates that location i is a hotspot; conversely, when Z < 0 and the p-value is significant, it indicates that location i is a cold spot.

2.5.3 Geographical detector model with optimized parameters

To identify the driving mechanisms behind the spatial differentiation of NGPCL in Guizhou Province, we employed the optimal-parameter Geodetector model. Grounded in the theory of spatial stratified heterogeneity, it is particularly effective for quantifying the explanatory power of various factors on a dependent variable’s spatial pattern. By utilizing both factor and interaction detection, Geodetector can dissect the individual and combined effects of driving variables, making it ideally suited for analyzing phenomena with significant spatial autocorrelation (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2010). Unlike traditional regression models constrained by linearity or independence assumptions, this approach is well suited to unravel the pronounced spatial heterogeneity and complex nonlinear relationships stemming from the fragmented topography and diverse land-use patterns of Guizhou’s karst region. This provides a robust analytical framework for identifying the driving forces of such geographical phenomena. We specifically employed the optimal-parameter Geographical Detector model refined by Song et al. (2020), to enhance the accuracy and stability of identifying and quantifying spatially stratified heterogeneity. To ensure accurate identification of spatial heterogeneity, each driving factor was discretized within the model using multiple classification methods (e.g., natural breaks, quantile). The model then automatically selected the optimal scheme for each factor, ensuring the most accurate representation of its spatial stratification. We optimized the spatial scale and classification number to maximize explanatory power, which substantially improved the accuracy and stability in detecting spatially stratified heterogeneity. Finally, the explanatory power and their interactions were assessed through permutation tests, ensuring the robustness and reliability of our results. This approach not only pinpoints the primary drivers of NGPCL in Guizhou Province but also clarifies their differential contributions to spatial heterogeneity, thereby establishing a theoretical foundation for understanding the NGPCL process in karst mountainous regions. The principle of factor detection is as follows (Equation 4):

In the formula, Hh represents the number of units in layer h, and h denotes the total number of units in the study area; and represent the variance of the non-grain production rate in layer h and in the entire study area, respectively. q represents the explanatory power of a factor, with a value range of [0, 1]. A value of 0 suggests that the independent variable does not explain the spatial distribution of the dependent variable, whereas a higher q value reflects a stronger ability to explain spatial differentiation, indicating a more pronounced impact on the distribution of non-grain production of cultivated land. Interaction factor detection can be used to identify the explanatory power of the interactions between different independent variables. The judgment criteria are shown in Table 1.

3 Results

3.1 Present condition of non-grain cultivated land

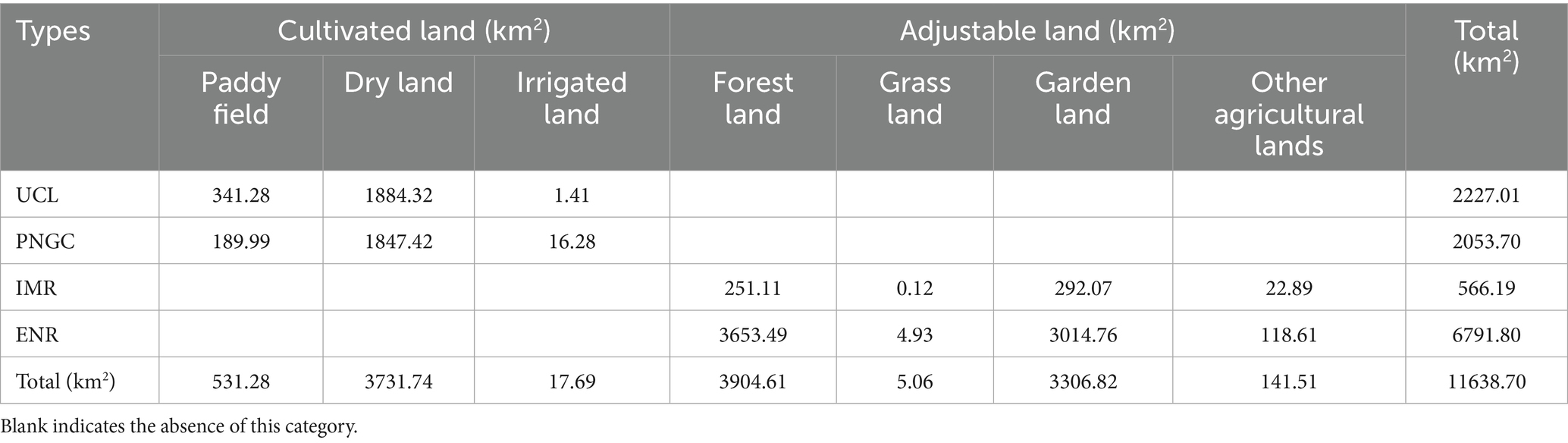

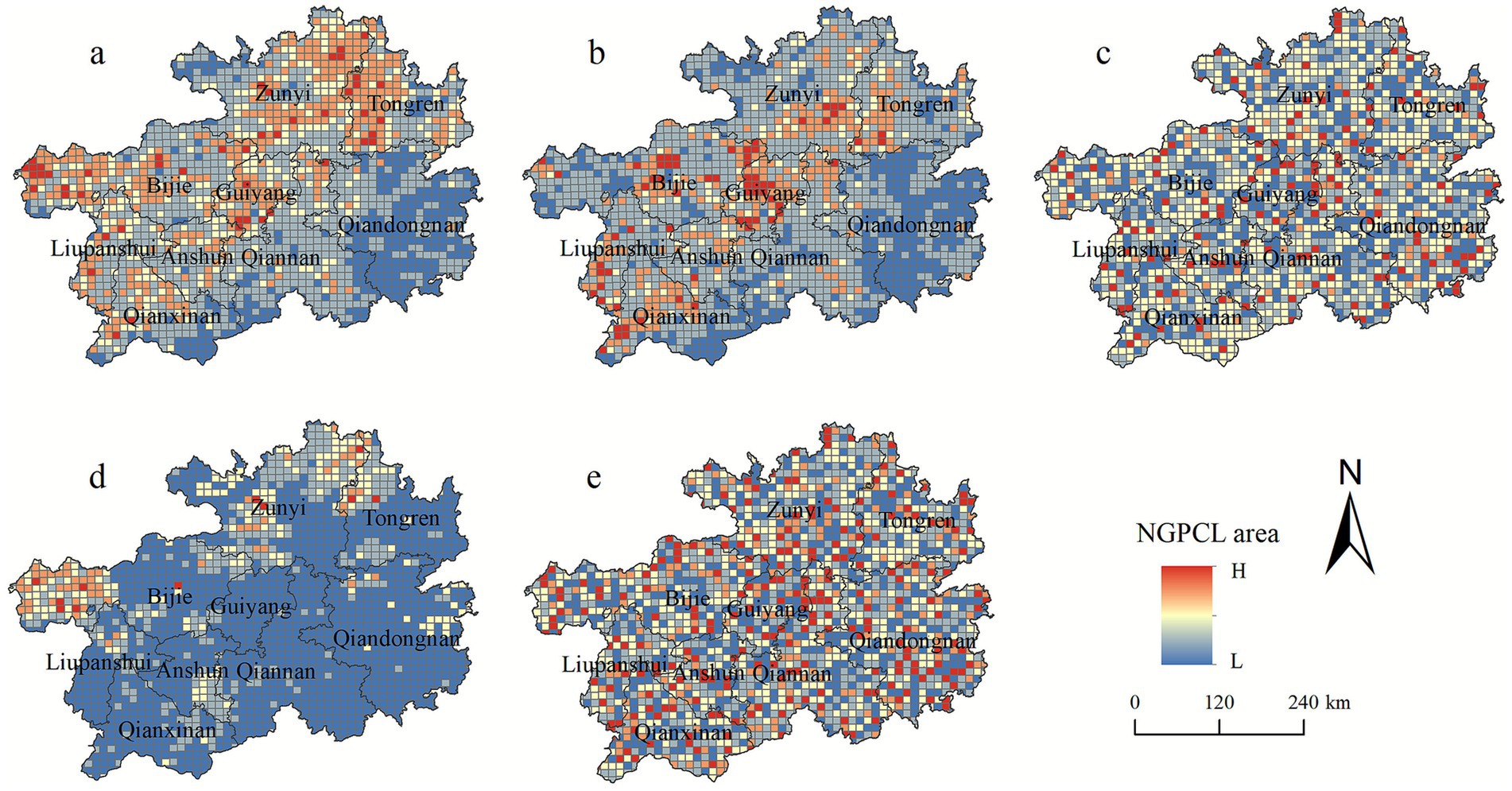

Guizhou is a typical karst landscape region characterized by intense karst development (Luo et al., 2021), rugged and fragmented terrain, poor soil quality, scattered cultivated land resources, and prominent ecological issues such as rocky desertification and land degradation. Under the combined influence of various factors, the trend toward non-grain cultivation has become increasingly pronounced. Analysis of 2022 land use data reveals that non-grain cultivated land in Guizhou Province totaled 11638.70 km2 (Table 2), representing 27.78% of the province’s total cultivated land area (41894.49km2). ENR was the dominant type, accounting for 58.36% of the total, while IMR was the smallest at 566.19 km2. The primary conversions were to forest and orchard land, totaling 7211.43 km2, with forest land alone constituting the largest portion of 3904.61 km2. From a spatial perspective (Figure 3), the NGPCL in Guizhou Province is concentrated in the western, central, and northeastern regions. ENR is concentrated in the central and northeastern regions, PNGC is primarily located in the western and northeastern regions, while IMR and UCL are sparsely distributed.

Figure 3. Spatial distribution of different types of non-grain cultivated land in Guizhou Province; (a) non-grain cultivated land; (b) ENR; (c) IMR; (d) PNGC; (e) UCL; L denotes low, and H denotes high non-grain cultivated land area.

3.2 Spatial pattern and differentiation characteristics of non-grain cultivated land

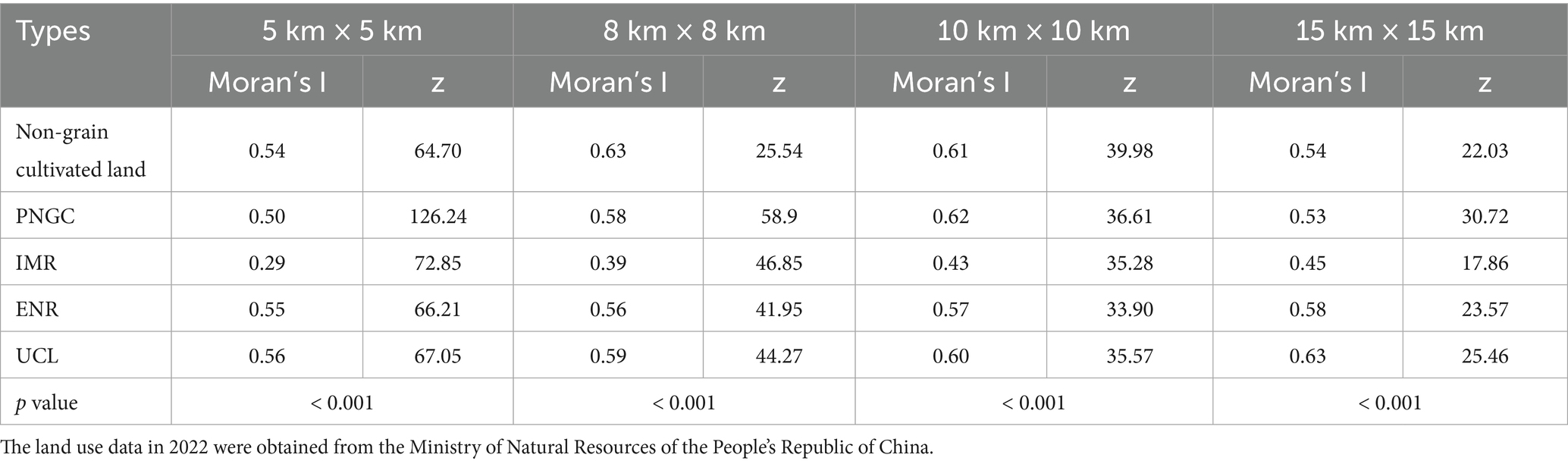

To objectively determine the optimal grid scale, we evaluated four resolutions (5 × 5 km, 8 × 8 km, 10 × 10 km, and 15 × 15 km) based on the strength of their global spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I), statistical significance (z- and p-values), and overall scale appropriateness. The 10 × 10 km scale exhibited the highest average Moran’s I, with all corresponding z-values being highly significant (p < 0.001), indicating stronger spatial autocorrelation and a more defined spatial structure at this resolution. By contrast, the 5 km scale, despite yielding higher z-values, is susceptible to local noise due to its high grid density. The 15 km scale, on the other hand, suffers from excessive spatial smoothing. Therefore, the 10 × 10 km grid was selected as the analytical unit.

The use of a multi-scale grid approach is well established in land research within karst and mountainous regions. Notable applications include studies on sloping cultivated land in Guizhou and on NGPCL in Hunan (Xu et al., 2025; Zhang et al., 2020). This body of work provides a strong methodological precedent for our study, validating the choice of this analytical strategy. Overall NGPCL and the four categories (PNGC, IMR, ENR, UCL) show Moran’s I values of 0.61, 0.62, 0.43, 0.57, and 0.60, respectively, in Guizhou Province. All z-scores passed the two-tailed significance test at the 0.01 confidence level. The results indicate that the distribution of various non-grain cultivated land types in Guizhou Province is characterized by significant positive spatial autocorrelation and strong clustering. Variations in Moran’s I indices among different types reveal that clustering is not uniform: PNGC and ENR show pronounced aggregation, whereas IMR is less clustered. These patterns highlight substantial spatial heterogeneity across the province. Based on these findings, we conducted spatial hotspot analysis to further delineate the specific agglomeration states of non-grain cultivated land (see Table 3).

Table 3. Spatial autocorrelation analysis of different types of non-grain cultivated land in Guizhou Province.

3.3 Spatial hotspot analysis results of NGPCL

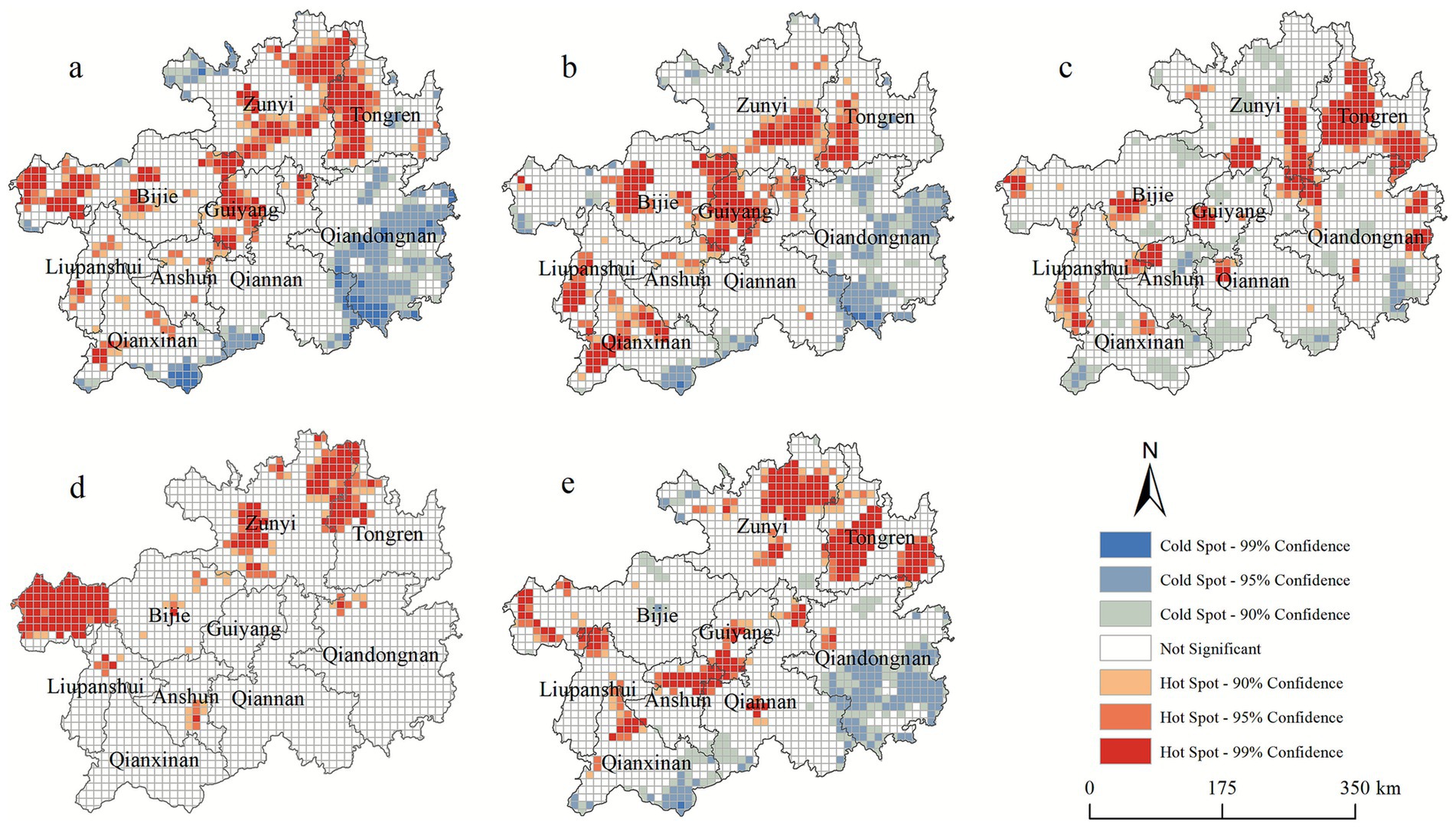

The results of Guizhou Province’s 2022 hotspot analysis for non-grain cultivated land (Figure 4a) indicate that such cultivation is mainly concentrated in the central and northeastern regions, while the southeastern region appears as a cold spot and the surrounding areas show no significant trends. The hotspot areas are primarily located in Guiyang City, Zunyi City, and Tongren City, whereas the cold spot areas are mainly concentrated in the Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture. UCL and ENR exhibited similar patterns (Figures 4b,e): coldspots dominated Qiandongnan, where complex terrain and strict ecological regulations preclude large-scale restoration, whereas hotspots were concentrated in the central region and the Tongren-Zunyi junction. This pattern reflects a regional focus on ecological conservation and traditional agriculture in typical ethnic minority areas. In contrast, Guiyang’s status as a provincial capital has driven significant urban expansion, while the Zunyi-Tongren border has developed specialty agriculture (e.g., tea cultivation), leading to widespread ENR, UCL, and PNGC. IMR showed extreme hotspots mainly in Tongren City, with scattered hotspots and coldspots in surrounding areas (Figure 4c). For PNGC (Figure 4d), there are no clustered cold spots; the hotspots are primarily concentrated in the western part of Bijie and at the junction of Zunyi and Tongren, with the remaining hotspots sporadically distributed across the study area. The western region of Bijie lies at a high elevation, making it suitable for cultivating hardy economic crops such as alpine tea and medicinal herbs. Under the combined influence of ecological agriculture initiatives and policy guidance, a substantial area of PNGC has developed in this region.

Figure 4. Hotspot analysis of different types of NGPCL in Guizhou Province; (a) non-grain cultivated land; (b) ENR; (c) IMR; (d) PNGC; (e) UCL; grid size: 10 km × 10 km; significance threshold: 0.05 (p < 0.05); spatial weight type: Rook contiguity.

3.4 Analysis results of driving factors of NGPCL in Guizhou Province

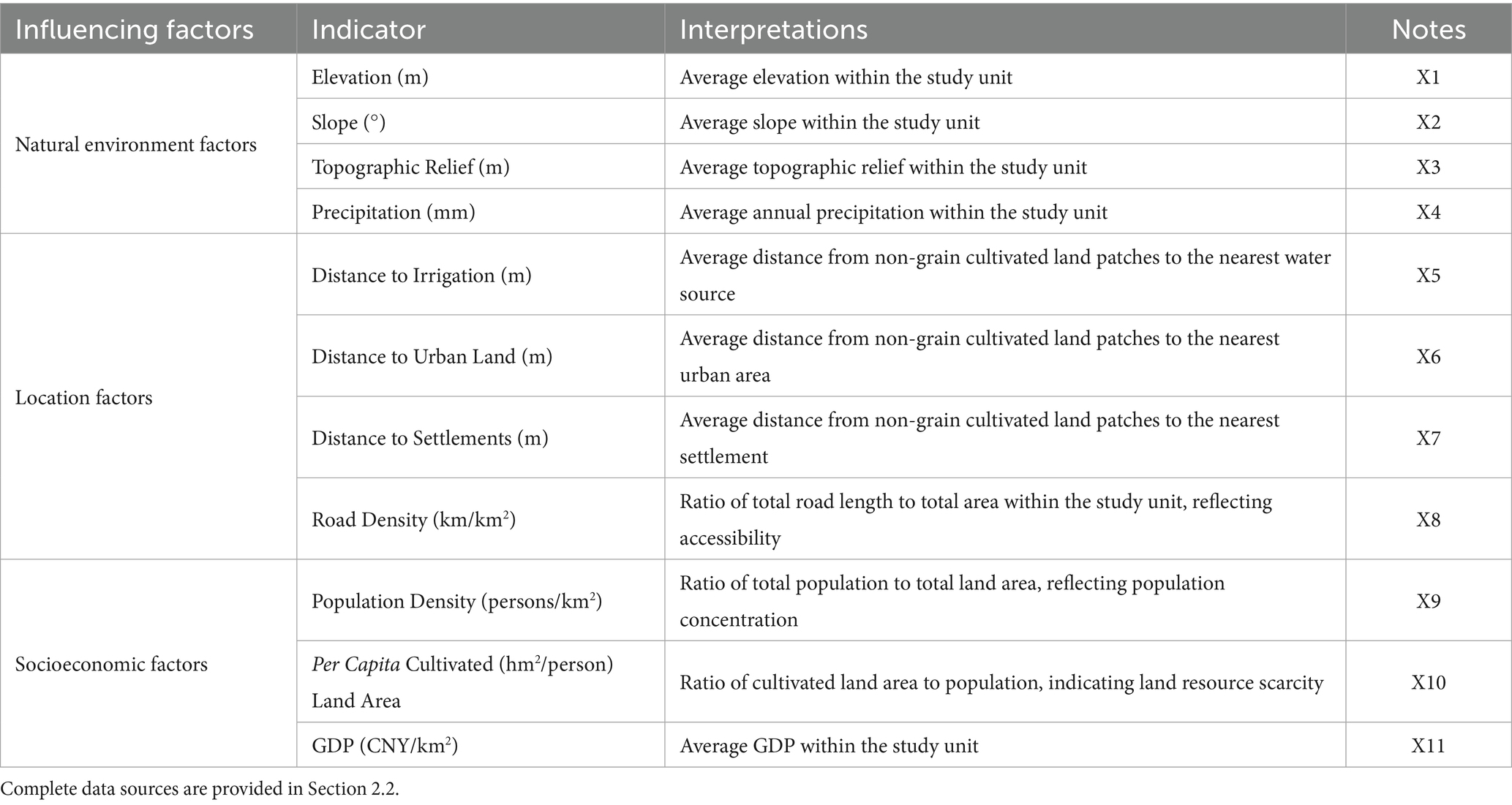

To explore the driving forces behind NGPCL, this study draws on existing research and considers the specific context of Guizhou Province, selecting 11 factors from three dimensions for analysis (Jiang et al., 2024; Bo et al., 2025; Mann et al., 2010): natural environment, locational conditions, and socioeconomic factors. Among natural factors, elevation governs hydrothermal conditions, while precipitation influences the classification and spatial distribution of cultivated land; both ultimately determine its actual use. Furthermore, slope and topographic relief dictate the contiguity and steepness of the land. Gentle terrain facilitates large-scale grain cultivation, whereas steep and rugged areas entail higher production costs, indirectly driving the formation and distribution of NGPCL. Locational conditions, including agricultural production convenience, transportation of agricultural products, and irrigation, affect the conversion of cultivated land to non-grain uses to varying degrees. Regional economic development steers the allocation of land resources, as both farmers’ cultivation planning and government land policy-making are shaped by the level of regional economic development and the opportunity cost of planting. Therefore, to investigate the driving factors of NGPCL, this study selected indicators from three domains: the natural environment (elevation, slope, topographic relief, and precipitation), locational conditions (road density, distance to settlements, distance to irrigation, and distance to urban land), and socioeconomic factors (population density, per capita cultivated land area, and GDP) (see Table 4).

3.4.1 Single-factor analysis of NGPCL

According to the results of the geographic detector analysis (Table 5), the spatial distribution of non-grain cultivated land, ENR, and UCL in Guizhou Province is mainly influenced by distance to settlements, while the dominant factors for PNGC and IMR are average elevation and road density, respectively.

The main influencing factors of NGPCL in Guizhou Province are: distance to settlements (X7) > population density (X9) > slope (X2) > road density (X8) > topographic relief (X3). Among these factors, distance to settlements and population density exhibited the highest q-values, indicating that the intensity of human activity is the dominant driver of non-grain production. In areas in close proximity to settlements and with high population density, superior cultivation and infrastructure conditions incentivize farmers to plant more economically profitable non-grain crops, leading to pronounced spatial agglomeration. The explanatory power of slope, topographic relief, and road density is secondary; steep and rugged cultivated land is characterized by fragmentation and restricted farming conditions, which limit the use of agricultural machinery (Tarolli and Straffelini, 2020) and reduce land use efficiency. Meanwhile, low road density constrains the transport of agricultural products, further exacerbating the spatial heterogeneity of non-grain production.

For ENR, the main factors are: distance to settlements (X7) > slope (X2) > topographic relief (X3) > road density (X8). In areas far from settlements, with poor accessibility or complex terrain, cultivation is challenging. The difficulty of cultivating land that is remote from settlements, poorly accessible, or topographically complex leads farmers to abandon it. Subsequently, this abandoned land is more readily converted for ecological restoration and is influenced by General Office of the People’s Government of Guizhou Province (2016) to transition into forestland or cash crops such as fruit trees that balance ecological and economic benefits, resulting in extensive ENR.

For IMR, the main factors are: road density (X8) > distance to settlements (X7). In regions with a well-developed transportation network, high farming convenience and greater profitability from cash crops, combined with low returns from grain cultivation, drive farmers’ preference for economically beneficial crops such as fruit and tea trees, resulting in the formation of IMR.

For PNGC, the main factors are: DEM (X1) > precipitation (X4). Cool and moist hydrothermal conditions in the high-altitude regions of Guizhou are suitable for specialty cash crops such as tea and medicinal herbs. Coupled with the general unsuitability of these areas for large-scale mechanized grain cultivation, this promotes the concentrated distribution of PNGC.

For UCL, the main factors are: distance to settlements (X7) > population density (X9) > slope (X2). In areas far from settlements with sparse populations, a shortage of agricultural labor, combined with poor farming conditions on steep-sloped cultivated land, leads to low land utilization. This increases the likelihood of abandonment, resulting in the formation of uncultivated cultivated land.

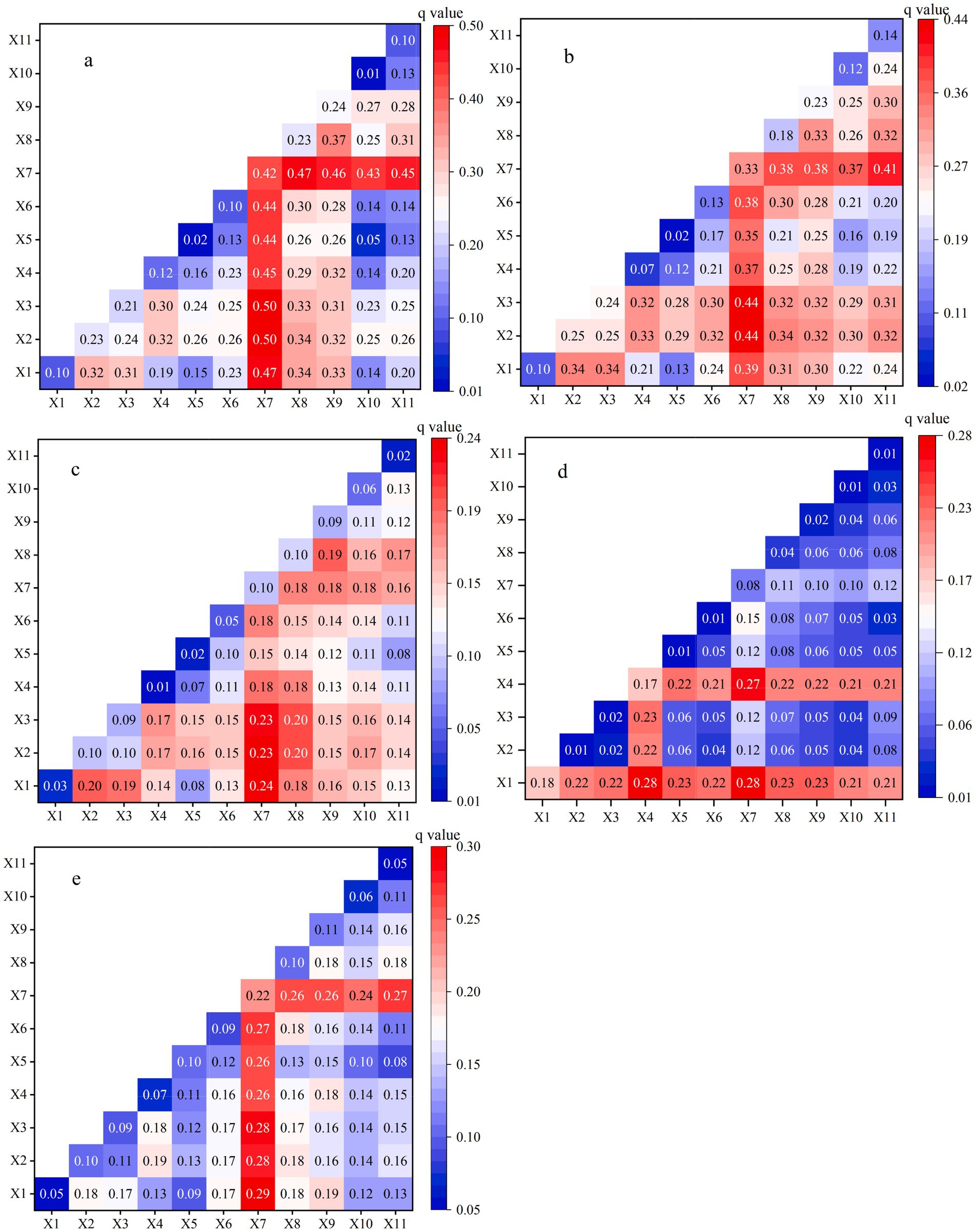

3.4.2 Interaction analysis of different influencing factors on NGPCL

Results from the interaction detection (Figure 5) reveal that the combined effects of factors provide greater explanatory power than any single factor. Interactions involving locational conditions were particularly significant, with the strongest enhancements observed between topographic relief and distance to residential settlements, and between road density and both distance to settlements and population density. Among all combinations, the interaction between distance to residential settlements and average elevation demonstrated the highest explanatory power for PNGC, IMR, and UCL.

Figure 5. Heatmap of interaction detection results for driving factors of NGPCL; (a) non-grain cultivated land; (b) ENR; (c) IMR; (d) PNGC; (e) UCL. The specific meanings of variables X1–X11 are detailed in Table 4.

The interactions of topographic relief with distance to settlements (X3∩X7) and of slope with distance to settlements (X2∩X7) are the dominant factors influencing the spatial differentiation of non-grain cultivated land in Guizhou Province (Figure 5a). In karst mountainous regions with steep slopes and high topographic relief, severe soil and water loss combined with greater distance to settlements and labor shortages reduces the feasibility of cultivation, leading to extensive non-grain cultivated land. The interaction between distance to settlements and any natural or socioeconomic factor consistently produces an enhancing effect, indicating that human activity has a strong regulatory influence on cultivated land-use patterns and is a key factor shaping the spatial pattern of non-grain production.

The interaction between slope and distance to settlements (X2∩X7) has the greatest impact on the spatial differentiation of ENR (Figure 5b). Notable interactions also include DEM and distance to settlements (X1∩X7), topographic relief and distance to settlements (X3∩X7), and distance to settlements and road density (X7∩X8). Steep slopes, high relief, and high altitude increase the difficulty of agricultural operations. This challenge is compounded by poor farming accessibility due to distance from settlements, which further undermines the sustainability of agricultural production. Ecological restoration policies that convert farmland back to forests and grasslands tend to be prioritized in these areas, thereby driving the spatial clustering of ENR.

The interaction between DEM and distance to settlements (X1∩X7) has the greatest influence on the spatial differentiation of IMR, PNGC, and UCL (Figures 5c,d,e). Lower annual average temperatures in high-elevation areas limit the cultivation of heat-requiring grain crops such as rice and corn. When these areas are also distant from settlements, the increased cultivation costs and labor difficulties incentivize farmers to abandon cultivation or switch to more profitable non-grain crops such as fruit trees and vegetables. This leads to the formation of UCL, IMR, and PNGC. Consequently, the interaction between elevation and distance from settlements promotes a more concentrated distribution of these non-grain land types. Long-term uncultivated farmland gradually transitions into IMR.

In UCL (Figure 5e), aside from DEM and distance to settlements (X1∩X7), the more significant interactions involve other factors with distance to settlements. This indicates that distance to settlements (cultivation distance) is the predominant driver of UCL. Cultivated land that is remote, high in elevation, and steep is inherently difficult to cultivate. Increased farming distances and higher production costs lead farmers to abandon it, forming uncultivated land. The interactions that are more significant in PNGC (Figure 5d) also include elevation and precipitation (X1∩X4) and precipitation and distance to settlements (X4∩X7). The interplay of topographic constraints, rainfall conditions, and distance from settlements in high-altitude areas favors the cultivation of cash crops characterized by flexible management and high input–output ratios, collectively shaping the spatial pattern of PNGC. In IMR (Figure 5c), other significant interactions include slope and distance to settlements (X2∩X7), topographic relief and distance to settlements (X3∩X7), slope and road density (X2∩X8), and topographic relief and road density (X3∩X8). In areas with steep slopes or fragmented terrain, compounded by remoteness from settlements and poor accessibility, cultivated land is prone to abandonment or conversion to fruit and tree cultivation. The planting of tea and fruit trees offers both ecological and economic benefits and aligns with the ecological restoration process.

4 Discussion

4.1 Mechanisms influencing the non-grain production of cultivated land

The driving factors of NGPCL vary due to differences in natural environment, locational conditions, and the level of socioeconomic development. Nguyen et al. (2018) demonstrated that in remote areas, logistical constraints and high labor costs diminish land-use efficiency, making these regions prone to non-grain conversion or abandonment. In their study of China’s major grain-producing areas. Osawa et al. (2016) found that farmland abandonment in Japan results from the combined influence of natural and social factors, with the primary drivers varying across regions. Our findings support the notion that increasing distance between settlements and cultivated land promotes non-grain conversion. This is driven by reduced cultivation incentives, as greater distance increases transportation and labor costs. This effect is amplified by the complex karst topography, in which rugged terrain worsens cultivation and transport difficulties and impedes infrastructure development. Consequently, reduced accessibility of remote cultivated land weakens agricultural enthusiasm and further accelerates the trend toward non-grain uses.

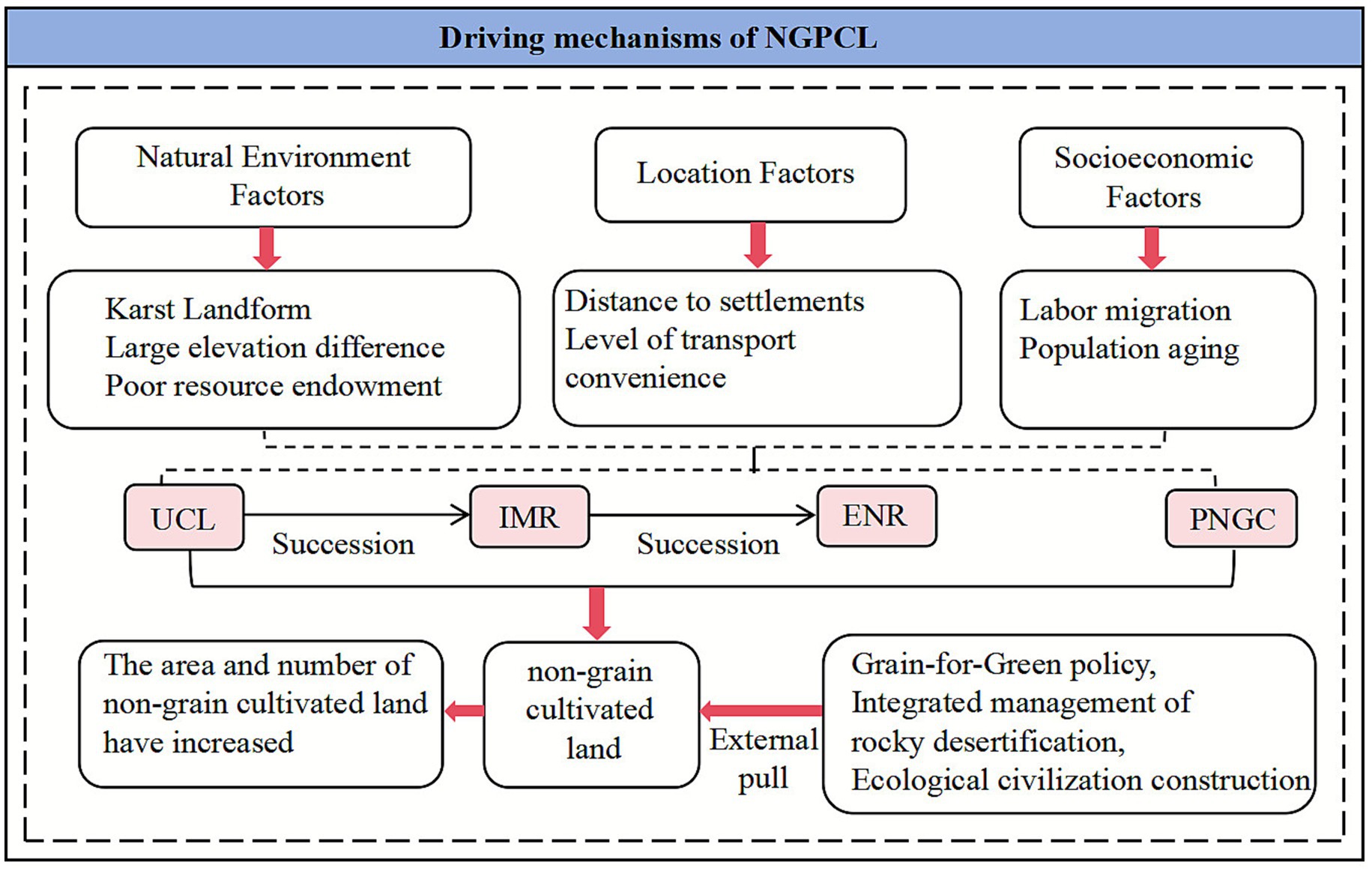

Focusing on the unique karst topography of Guizhou Province, this study further investigates the driving mechanisms of NGPCL (Figure 6). The region’s ecosystem is fragile, with pronounced rocky desertification and land degradation (Dx, 1997). The prevalence of mountains and hills results in fragmented, low-quality cultivated land, making it susceptible to agricultural structural adjustment or abandonment (Su G. et al., 2018; Subedi et al., 2021). Under the combined influence of topographic constraints and agricultural transformation, there has been a significant conversion of cultivated land to dual-purpose uses, such as forestland and orchard land, which balance ecological and economic functions. This trend has been further reinforced by the implementation of the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Land-use structural adjustments, integral to ecological civilization initiatives and rural development, have directly reduced grain-producing areas. Concurrently, poverty alleviation campaigns have promoted the large-scale cultivation of specialty cash crops like tea, fruits, and medicinal herbs. This has boosted farmer incomes, creating a demonstration effect that encourages others to follow, thereby further accelerating the non-grain conversion trend (Gellrich et al., 2007; Anselin, 2002).

In the karst mountainous regions of Guizhou, different topographic conditions exert a significant influence on NGPCL types. Karst mountainous valley bottoms, characterized by gentle topography, gentle topography, convenient transportation, proximity to settlements, and an abundant labor force make the area suitable for mechanized farming and the transport of high-value cash crops (Cherono and Workneh, 2018), promoting the conversion of cultivated land to PNGC, IMR, and ENR. On karst valley slopes, steep gradients are prone to soil and water loss, and transportation networks are inadequate. Consequently, farmers tend to plant fruit and forest trees to balance ecological and economic benefits, leading to the formation of IMR and ENR. On the valley tops of the karst regions, thin soil layers and poor water retention lead to costly grain cultivation with low returns. Accompanied by population aging and labor loss (Nguyen et al., 2018; Imai et al., 2023), the likelihood of cultivated land abandonment increases (Nguyen et al., 2018; Imai et al., 2023), forming uncultivated land. Prolonged non-cultivation leads to succession toward IMR and ENR.

Compared with regions such as Hokkaido (Osawa et al., 2016), China’s major grain-producing areas (Zhao et al., 2023), and West Java Province (Maryati et al., 2018), the karst mountainous areas are disadvantaged in terms of the quantity and quality of cultivated land, topographic conditions, transportation accessibility, and ecological environment. Consequently, the drivers of NGPCL differ across regions. Yet the expanding area of non-grain cultivated land represents a pervasive challenge. Preventing further conversion is therefore crucial for safeguarding both food and ecological security. Future efforts must prioritize strengthening the monitoring and early warning of this trend while maintaining ecological security, thereby promoting rational utilization and the sustainable development of mountainous cultivated land. Finally, we emphasize that the identification of driving mechanisms in this study is highly dependent on the chosen spatial scale. The influence of these factors varies with spatial resolution, and the conclusions derived from the driving mechanism analysis are associated with the spatial scale. Finer scales tend to amplify the local effects of micro-topographic factors such as slope and relief, whereas coarser scales reinforce the overall impact of macro factors such as GDP and population density and reduce the expression of fine-grained topographical or locational variations. The 10 km scale adopted in this study strikes a balance between the noise inherent in finer scales and the over-smoothing present at coarser scales. This resolution is well suited to the spatial characteristics of cultivated land in karst mountainous regions and provides a more empirically grounded perspective for the analysis of driving mechanisms.

4.2 Differentiated management and control strategies for NGPCL in the karst mountain areas of Guizhou

Guizhou Province has poor resource endowments and severe rocky desertification. Influenced by topography, climate, and other factors, the driving mechanisms vary across non-grain cultivated land types. Its complex terrain and landforms significantly influence cultivation decisions made by farmers and government bodies. Based on the four types of driving mechanisms of non-grain cultivated land identified in this study, we propose targeted cultivated land protection strategies.

ENR constitutes 58.36% of the province’s total NGPCL area and is the dominant type of non-grain cultivated land that should be prioritized for restoration. However, given the high costs associated with its reconversion to cultivated land, this paper explicitly defines the “restorability” of ENR as a dual dimension of technical feasibility and alignment with policy planning. Within Ecological Conservation Red Line zones, ENR should be primarily protected to strictly prevent ecological damage. Where the illegal occupation of basic or high-standard farmland has led to the destruction of topsoil and soil quality degradation (Dunjó et al., 2003), conditions for grain cultivation must be restored through soil reconstruction and fertility restoration techniques. Meanwhile, non-basic farmland plots should implement ecological buffering and rotational cultivation and recultivation. For mountainous ENR, such as in the border area between Tongren and Zunyi, which is characterized by significant topographic relief, steep slopes, high-altitude hills, and widespread rocky desertification (Department of Natural Resources of Guizhou Province, 2022), a slope-based graded management approach should be applied. This includes implementing rocky desertification control and ecological recultivation for ENR on slopes of 15–25° and strictly restricting the conversion of farmland with slopes greater than 25° to forestland under the Grain-for-Green Policy. This approach is beneficial for reducing soil and water loss, improving the ecological environment, and achieving positive interaction between ecological protection and economic development (Amidi et al., 2020; Rasiah et al., 2015).

For spatially concentrated UCL on slopes of less than 15°, protection and utilization should be prioritized. This involves optimizing the allocation and management of cultivated land resources and, in conjunction with grain planting subsidy policies (Wang et al., 2026), enhancing farmers’ enthusiasm for grain cultivation to stabilize the scale of grain production. For UCL that is of low quality and spatially scattered, its comprehensive grain production capacity should be enhanced by consolidating fragmented land and equipping it with basic production facilities. For UCL on slopes between 15° and 25°, rotational cultivation and fallow systems can be implemented to restore land productivity while balancing ecological protection. UCL with slopes greater than 25° should be incorporated into ecological restoration plans and undergo long-term monitoring to ensure a steady enhancement of ecological functions. With the diversification of demand for agricultural products, the increase in land for non-grain crop cultivation is justifiable in practice (Gawdiya et al., 2025; Hufnagel et al., 2020). Therefore, for PNGC outside of basic farmland, scientific guidance can be applied to their cropping structure. This involves rationally planning the rotation of grain and non-grain crops based on their varying nutrient requirements (Liu et al., 2022) to avoid soil quality degradation from long-term non-grain cultivation. As for basic farmland, which serves as the core safeguard area for grain production, any PNGC within its boundaries must be strictly limited to the cultivation of grain crops to ensure that the bottom line of national food security is not breached. IMR is sparsely distributed in Guizhou, accounting for only 4.86%. Therefore, for IMR, which is predominantly located in Tongren City (Figure 4c), it is necessary to strengthen planting planning and control, adopting a prevention-first approach to avert its succession into ENR.

Strengthen the management of areas with non-grain cultivated land. For hotspot areas of non-grain cultivation, it is necessary to establish strict land-use control measures and scientifically guide the rational layout of non-grain crops to prevent the expansion of non-grain farming. For cold spot areas, technical support and policy assistance for grain cultivation should be increased to consolidate their advantages in grain production. As the core safeguard zones for grain production, the expansion of non-grain cultivation must be comprehensively prohibited within Permanent Basic Farmland Protection Zones and Major Grain Production Functional Zones to safeguard the bottom lines of food security and the stable supply of major agricultural products. The government should fully leverage its guiding role in the allocation of cultivated land resources (Marson, 2025). This involves consolidating contiguous cultivated land at the township or village level to address fragmentation and establishing a differentiated subsidy mechanism. Grain subsidies should be prioritized for gently sloped cultivated land and basic farmland. Through policy incentives and optimized resource allocation, the objective is to protect cultivated land resources and achieve sustainable land use.

4.3 Limitations and future prospects

While this study, focusing on the karst mountainous areas of Guizhou Province, investigates the spatial differentiation and driving mechanisms of various types of non-grain cultivated land to provide a scientific basis for their protection, it is subject to the following specific limitations considering its research design, data support, and analytical methods. The primary reliance on cross-sectional data makes it difficult to capture the long-term dynamic evolution of non-grain cultivation. Furthermore, the analysis did not refine the distinctions between different karst landforms, such as karst basins and peak-cluster depressions, leading to an insufficient revelation of the specificities of non-grain cultivation within each. Consequently, the management implications derived are skewed toward the macro level, hindering direct guidance for precise, plot-level policy implementation. This may limit the comprehensiveness of our research findings. Future research can enhance the precision, practical value, and operability of this study. This can be achieved by integrating long-term time-series remote sensing with field survey data, refining the analysis for different karst landforms and plot-level management schemes, and conducting an in-depth analysis of the coupling pathways among physical geographical conditions, policy interventions, and farmer decision-making behavior.

5 Conclusion

This study focuses on the non-grain cultivated land of 2022 in Guizhou Province, a typical karst mountainous area. Employing methods of Global Autocorrelation Analysis, Hotspot Analysis, and the Optimal Parameters-based Geodetector model, we investigate the spatial differentiation characteristics and driving factors of non-grainification. The main conclusions are as follows:

1. In 2022, NGPCL in Guizhou Province constituted 27.78% of the total cultivated land area. The ENR type was the most widespread, primarily involving the conversion of cultivated land to forests and gardens. At the 10 km × 10 km scale, all types of non-grain cultivated land exhibited significant spatial clustering (Moran’s I: 0.43–0.62).

2. The NGPCL in Guizhou Province was mainly characterized by hotspot areas concentrated in the central and northeastern regions, cold spots in the southeast regions, and an insignificant pattern in the surrounding areas. For ENR and UCL, hotspots are concentrated in the central region and the Zunyi-Tongren border area, with coldspots in the southeast. IMR hotspots are focused on Tongren, while PNGC shows no coldspot areas, with its hotspots concentrated in western Bijie and the junction of Zunyi and Tongren. This spatial pattern was influenced by multiple factors, among which distance to settlements (q = 4.2) emerged as the dominant driver. Furthermore, the dominant factors varied across different NGPCL types, indicating differentiated causal characteristics.

3. The formation of NGPCL is driven by complex interactions among multiple factors. Our interaction detection revealed that the synergy between distance to settlements and natural factors was the most significant driver, with the strongest interaction being X3∩X7 (q = 0.50, 18.3% enhancement), promoting the diversity of NGPCL types. Although the dominant drivers of different non-grain types vary significantly, they exhibit internal connections, with these land types undergoing dynamic transitions in which long-term uncultivated land evolves into IMR or ENR.

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: confidential data. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to MjMyMTAwMTcwNTc0QGd6bnUuZWR1LmNu.

Author contributions

NC: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Software. JZ: Funding acquisition, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JT: Writing – review & editing, Software. FZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. LY: Software, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Project: Research and Application of Comprehensive Monitoring Technology System for Geographic National Conditions in Karst Basins (Qiankehe Support [2023]General 222), China; the Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program ([2023] General 218).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Amidi, J., Stephan, J. M., and Maatouk, E. (2020). Reforestation for environmental services as valued by local communities: a case study from Lebanon. For. Econ. Rev. 2, 97–115. doi: 10.1108/FER-07-2019-0017

Anselin, L. (2002). Under the hood issues in the specification and interpretation of spatial regression models. Agric. Econ. 27, 247–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2002.tb00120.x

Belay, T., and Mengistu, D. A. (2019). Land use and land cover dynamics and drivers in the Muga watershed, upper Blue Nile basin, Ethiopia. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 15:100249. doi: 10.1016/j.rsase.2019.100249

Bo, H., Shang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., Gao, J., and Guo, X. (2025). Analysis of spatial and temporal characteristics and driving factors of “non-grain” cultivated land in Hebei Province. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 33, 960–972. doi: 10.12357/cjea.20240617

Bren d’Amour, C., Reitsma, F., Baiocchi, G., Barthel, S., Güneralp, B., Erb, K. H., et al. (2017). Future urban land expansion and implications for global croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8939–8944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606036114,

Bryan, B. A., Gao, L., Ye, Y., Sun, X., Connor, J. D., Crossman, N. D., et al. (2018). China’s response to a national land-system sustainability emergency. Nature 559, 193–204. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0280-2,

Chen, Y. (2012). Fractal dimension evolution and spatial replacement dynamics of urban growth. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 45, 115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2011.10.007

Chen, B., Liu, Y., He, X., and Jiang, H. (2024). Exploration of cultivated land use paths in mountainous areas balancing carbon emission reduction and food security. Prog. Geogr. 43, 1372–1388. doi: 10.18306/dlkxjz.2024.07.008

Cheng, X., Tao, Y., Huang, C., Yi, J., Yi, D., Wang, F., et al. (2022). Unraveling the causal mechanisms for non-grain production of cultivated land: an analysis framework applied in Liyang, China. Land 11:1888. doi: 10.3390/land11111888

Cherono, K, and Workneh, T. Effect of packing units during long distance transportation on the quality and shelf-life of tomatoes under commercial supply conditions. XXX international horticultural congress IHC2018: International symposium on fruit and vegetables for processing, international 1292, 2018:165–174.

Cottrell, R. S., Fleming, A., Fulton, E. A., Nash, K. L., Watson, R. A., and Blanchard, J. L. (2018). Considering land–sea interactions and trade-offs for food and biodiversity. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 580–596. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13873,

Department of Natural Resources of Guizhou Province. Major Data Bulletin of the Third National Land Survey in Guizhou Province. Official Website of Department of Natural Resources of Guizhou Province. (2021). Available at: https://zrzy.guizhou.gov.cn/wzgb/ztzl/lszt/gzsdscqggtdc/scdcgtdt/202206/t20220606_74618579.html

Do, V. H., La, N., Mulia, R., Bergkvist, G., Dahlin, A. S., Nguyen, V. T., et al. (2020). Fruit tree-based agroforestry systems for smallholder farmers in Northwest Vietnam—a quantitative and qualitative assessment. Land 9:451. doi: 10.3390/land9110451

Dong, Q., Peng, Q., Luo, X., Lu, H., He, P., Li, Y., et al. (2024). The optimal zoning of non-grain-producing cultivated land consolidation potential: a case study of the Dujiangyan Irrigation District. Sustainability 16:7798. doi: 10.3390/su16177798

Dunjó, G., Pardini, G., and Gispert, M. (2003). Land use change effects on abandoned terraced soils in a Mediterranean catchment, ne Spain. Catena 52, 23–37. doi: 10.1016/S0341-8162(02)00148-0

Dx, Y. (1997). Rock desertification in the subtropical karst of South China. Z. Geomorphol. 108, 81–90.

El Kateb, H., Zhang, H., Zhang, P., and Mosandl, R. (2013). Soil erosion and surface runoff on different vegetation covers and slope gradients: a field experiment in southern Shaanxi Province, China. Catena 105, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2012.12.012

Feng, Y., Chen, X., Gao, F., and Liu, Y. (2018). Impacts of changing scale on Getis-Ord Gi* hotspots of Cpue: a case study of the neon flying squid (Ommastrephes bartramii) in the Northwest Pacific Ocean. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 37, 67–76. doi: 10.1007/s13131-018-1212-6

Feng, Y., Ke, M., and Zhou, T. (2022). Spatio-temporal dynamics of non-grain production of cultivated land in China. Sustainability 14:14286. doi: 10.3390/su142114286

Gawdiya, S., Sharma, R. K., Singh, H., and Kumar, D. (2025). Crop diversification as a cornerstone for sustainable agroecosystems: tackling biodiversity loss and global food system challenges. Discov. Appl. Sci. 7, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s42452-025-06855-z

Gellrich, M., Baur, P., Koch, B., and Zimmermann, N. E. (2007). Agricultural land abandonment and natural forest re-growth in the Swiss mountains: a spatially explicit economic analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 118, 93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2006.05.001

General Office of the People’s Government of Guizhou Province. (2016). Notice of the general Office of the People’s government of Guizhou Province on printing and distributing the “work plan for the Forest-grass combined model under the new round of the grain-for-green program in Guizhou Province” (Qianfubanfa [2016] no. 3). Guizhou Provincial People’s Government Official Website. (2016). Available at: https://www.guizhou.gov.cn/zwgk/zcfg/szfwj/qfbf/201710/t20171027_70473579.html

Hu, J., Wang, H., and Song, Y. (2023). Spatio-temporal evolution and driving factors of “non-grain production” in Hubei province based on a non-grain index. Sustainability 15:9042. doi: 10.3390/su15119042

Hufnagel, J., Reckling, M., and Ewert, F. (2020). Diverse approaches to crop diversification in agricultural research. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 40:14. doi: 10.1007/s13593-020-00617-4

Imai, N., Otokawa, H., Okamoto, A., Yamazaki, K., Tamura, T., Sakagami, T., et al. (2023). Abandonment of cropland and seminatural grassland in a mountainous traditional agricultural landscape in Japan. Sustainability 15:7742. doi: 10.3390/su15107742

Jarzebski, M. P., Ahmed, A., Boafo, Y. A., Balde, B. S., Chinangwa, L., Saito, O., et al. (2020). Food security impacts of industrial crop production in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the impact mechanisms. Food Secur. 12, 105–135. doi: 10.1007/s12571-019-00988-x

Jiang, C., Wang, L., Guo, W., Chen, H., Liang, A., Sun, M., et al. (2024). Spatio-temporal evolution and multi-scenario simulation of non-grain production on cultivated land in Jiangsu Province, China. Land 13:670. doi: 10.3390/land13050670

Jie, S., Xiu, W., and Gui, H. (2024). Spatial pattern and driving factors of non-grain cultivation of cultivated land in the Sanjiang River basin (Yunnan section). J. Peking Univ. 60, 893–904. doi: 10.13209/j.0479-8023.2024.059

Lewis, D. J., Plantinga, A. J., and Wu, J. (2009). Targeting incentives to reduce habitat fragmentation. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 91, 1080–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8276.2009.01310.x

Li, Y., Zhao, B., Huang, A., Xiong, B., and Song, C. (2021). Characteristics and driving forces of non-grain production of cultivated land from the perspective of food security. Sustainability 13:14047. doi: 10.3390/su132414047

Liang, X., Jin, X., Liu, J., Yin, Y., Gu, Z., Zhang, J., et al. (2023). Formation mechanism and sustainable productivity impacts of non-grain croplands: evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 34, 1120–1132. doi: 10.1002/ldr.4520

Liu, C., Plaza-Bonilla, D., Coulter, J. A., Kutcher, H. R., Beckie, H. J., Wang, L., et al. (2022). Diversifying crop rotations enhances agroecosystem services and resilience. Adv. Agron. 173, 299–335. doi: 10.1016/bs.agron.2022.02.007,

Long, S., Cai, E., Li, L., Xie, F., Lai, S., Hu, H., et al. (2025). Structural changes, transfer trajectories, and driving forces of non-grain farmland in the main grain producing areas of Central China. J. Environ. Manag. 393:127029. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2025.127029,

Lu, D., Wang, Z., Su, K., Zhou, Y., Li, X., and Lin, A. (2024). Understanding the impact of cultivated land-use changes on China's grain production potential and policy implications: a perspective of non-agriculturalization, non-grainization, and marginalization. J. Clean. Prod. 436:140647. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140647

Luo, X., Wang, S., Bai, X., Tan, Q., Ran, C., and Chen, H. (2021). Spatiotemporal evolution of rocky desertification in the southwestern karst region of China. J. Ecol. 41, 680–693. doi: 10.5846/stxb201904030654

Mann, M. L., Kaufmann, R. K., Bauer, D., Gopal, S., Vera-Diaz, M. D. C., Nepstad, D., et al. (2010). The economics of cropland conversion in Amazonia: the importance of agricultural rent. Ecol. Econ. 69, 1503–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.02.008

Marson, M. (2025). Effects of public expenditure for agriculture on food security in Africa. Empir. Econ. 68, 2673–2704. doi: 10.1007/s00181-025-02713-4

Martínez-Paz, J. M., Banos-González, I., Martínez-Fernández, J., and Esteve-Selma, M. Á. (2019). Assessment of management measures for the conservation of traditional irrigated lands: the case of the Huerta of Murcia (Spain). Land Use Policy 81, 382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.050

Maryati, S, Humaira, A, and Pratiwi, F. Spatial pattern of agricultural land conversion in West Java Province. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 2018.

Miao, Y., Liu, J., and Wang, R. Y. (2021). Occupation of cultivated land for urban–rural expansion in China: evidence from national land survey 1996–2006. Land 10:1378. doi: 10.3390/land10121378

Nguyen, H., Hölzel, N., Völker, A., and Kamp, J. (2018). Patterns and determinants of post-soviet cropland abandonment in the Western Siberian Grain Belt. Remote Sens. 10:1973. doi: 10.3390/rs10121973

Osawa, T., Kohyama, K., and Mitsuhashi, H. (2016). Multiple factors drive regional agricultural abandonment. Sci. Total Environ. 542, 478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.067,

Plieninger, T., Draux, H., Fagerholm, N., Bieling, C., Bürgi, M., Kizos, T., et al. (2016). The driving forces of landscape change in Europe: a systematic review of the evidence. Land Use Policy 57, 204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.04.040

Ran, D., Zhang, Z., and Jing, Y. (2022). A study on the spatial–temporal evolution and driving factors of non-grain production in China’s major grain-producing provinces. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:16630. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192416630,

Rasiah, V., Florentine, S., and Dahlhaus, P. (2015). Environmental benefits inferred from impact of reforestation of deforested creek bank on soil conditioning: a case study in Victoria, Australia. Agrofor. Syst. 89, 345–355. doi: 10.1007/s10457-014-9771-9

Ren, G., Song, G., Wang, Q., and Sui, H. (2023). Impact of “non-grain” in cultivated land on agricultural development resilience: a case study from the major grain-producing area of Northeast China. Appl. Sci. 13:3814. doi: 10.3390/app13063814

Seto, K. C., and Ramankutty, N. (2016). Hidden linkages between urbanization and food systems. Science 352, 943–945. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7439,

Song, H., Li, X., Xin, L., and Wang, X. (2025). Improving mechanization conditions or encouraging non-grain crop production? Strategies for mitigating farmland abandonment in China’s mountainous areas. Land Use Policy 149:107421. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2024.107421

Song, Y., Wang, J., Ge, Y., and Xu, C. (2020). An optimal parameters-based geographical detector model enhances geographic characteristics of explanatory variables for spatial heterogeneity analysis: cases with different types of spatial data. GISci. Remote Sens. 57, 593–610. doi: 10.1080/15481603.2020.1760434

Sridharan, S., Tunstall, H., Lawder, R., and Mitchell, R. (2007). An exploratory spatial data analysis approach to understanding the relationship between deprivation and mortality in Scotland. Soc. Sci. Med. 65, 1942–1952. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.052

Su, B., Li, Y., Li, L., and Wang, Y. (2018). How does nonfarm employment stability influence farmers' farmland transfer decisions? Implications for China’s land use policy. Land Use Policy 74, 66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.053

Su, G., Okahashi, H., and Chen, L. (2018). Spatial pattern of farmland abandonment in Japan: identification and determinants. Sustainability 10:3676. doi: 10.3390/su10103676

Su, Y., Qian, K., Lin, L., Wang, K., Guan, T., and Gan, M. (2020). Identifying the driving forces of non-grain production expansion in rural China and its implications for policies on cultivated land protection. Land Use Policy 92:104435. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104435

Su, Y., Su, C., Xie, Y., Li, T., Li, Y., and Sun, Y. (2022). Controlling non-grain production based on cultivated land multifunction assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1027. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031027,

Subedi, Y. R., Kristiansen, P., Cacho, O., and Ojha, R. B. (2021). Agricultural land abandonment in the hill agro-ecological region of Nepal: analysis of extent, drivers and impact of change. Environ. Manag. 67, 1100–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00267-021-01461-2,

Sun, Y., Chang, Y., Liu, J., Ge, X., Liu, G.-J., and Chen, F. (2021). Spatial differentiation of non-grain production on cultivated land and its driving factors in coastal China. Sustainability 13:13064. doi: 10.3390/su132313064

Tarolli, P., and Straffelini, E. (2020). Agriculture in hilly and mountainous landscapes: threats, monitoring and sustainable management. Geogr. Sustain. 1, 70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.geosus.2020.03.003

UNICEF (2021). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021. New York: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund.

Wang, J. F., Li, X. H., Christakos, G., Wang, J.‐. F., Li, X.‐. H., Liao, Y.‐. L., et al. (2010). Geographical detectors-based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 24, 107–127. doi: 10.1080/13658810802443457

Wang, Q., Li, Y., and Luo, G. (2020). Spatiotemporal change characteristics and driving mechanism of slope cultivated land transition in karst trough valley area of Guizhou Province, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 79, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12665-020-09035-x

Wang, S. J., Liu, Q. M., and Zhang, D. F. (2004). Karst rocky desertification in southwestern China: geomorphology, landuse, impact and rehabilitation. Land Degrad. Dev. 15, 115–121. doi: 10.1002/ldr.592

Wang, X., Song, X., Wang, Y., Xu, H., and Ma, Z. (2024). Understanding the distribution patterns and underlying mechanisms of non-grain use of cultivated land in rural China. J. Rural. Stud. 106:103223. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103223

Wang, D., Su, Y., Yu, R., Jiang, X., Liu, X., Qian, J., et al. (2026). Inhibiting or promoting? Impacts of non-grain expansion on cropland ecosystem services: evidence from the Yangtze River Delta, China. Habitat Int. 167:103656. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2025.103656

Wang, L., Xu, J., Liu, Y., and Zhang, S. (2023). Spatial characteristics of the non-grain production rate of cropland and its driving factors in major grain-producing area: evidence from Shandong Province, China. Land 13:22. doi: 10.3390/land13010022

Wang, J.-F., Zhang, T.-L., and Fu, B.-J. (2016). A measure of spatial stratified heterogeneity. Ecol. Indic. 67, 250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.02.052

Xiang, K. (2020). The issue, causes, and countermeasures of the 'non-grain production' of cultivated land. Chinese land 30, 17–19. doi: 10.13816/j.cnki.ISSN1002-9729.2020.11.05

Xiao, Y., Wu, X.-Z., Wang, L., and Liang, J. (2017). Optimal farmland conversion in China under double restraints of economic growth and resource protection. J. Clean. Prod. 142, 524–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.027

Xiaoqing, S., Zhifeng, W., and Zhu, O. (2014). Route of cultivated land transition research. Geogr. Res. 33, 403–413. doi: 10.11821/dlyj201403001

Xu, L., Wen, C., Yi, Y., Yun, X., Liu, L., and Zhang, H. (2025). Study on the driving factors and spatial differentiation characteristics of non-grain cultivation of cultivated land in Hunan Province based on the GWR model. J. Nat. Sci. Hunan Norm. Univ. 48, 93–101. doi: 10.7612/j.issn.2096-5281.2025.02.011

Zhang, Y., Zhou, Z. F., Huang, D. H., Zhu, M., Wu, Y., and Sun, J. W. (2020). Analysis on spatial-temporal evolution and influencing factors of cultivated land in karst mountainous areas. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 36, 266–275. doi: 10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2020.22.030

Zhang, D., Yang, W., Kang, D., and Zhang, H. (2023). Spatial-temporal characteristics and policy implication for non-grain production of cultivated land in Guanzhong region. Land Use Policy 125:106466. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106466

Zhang, T., Zhang, F., Li, J., Xie, Z., and Chang, Y. (2024). Unraveling patterns, causes, and nature-based remediation strategy for non-grain production on farmland in hilly regions. Environ. Res. 252:118982. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2024.118982

Zhang, Z., Zheng, L., and Yu, D. (2023). Non-grain production of cultivated land in hilly and mountainous areas at the village scale: a case study in le’an country, China. Land 12:1562. doi: 10.3390/land12081562

Zhao, S., Xiao, D., and Yin, M. (2023). Spatiotemporal patterns and driving factors of non-grain cultivated land in China's three main functional grain areas. Sustainability 15:13720. doi: 10.3390/su151813720

Zhou, Y., Li, X., and Liu, Y. (2020). Land use change and driving factors in rural China during the period 1995-2015. Land Use Policy 99:105048. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105048

Zhu, Z., Dai, Z., Li, S., and Feng, Y. (2022a). Spatiotemporal evolution of non-grain production of cultivated land and its underlying factors in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8210. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138210,

Zhu, Z., Duan, J., Li, S., Dai, Z., and Feng, Y. (2022b). Phenomenon of non-grain production of cultivated land has become increasingly prominent over the last 20 years: evidence from guanzhong plain, China. Agriculture 12:1654. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12101654

Keywords: cultivated land, driving factors, karst mountainous areas, non-grain production, regulatory measures

Citation: Cai N, Zhong J, Tian J, Zhang F and Yan L (2025) Spatial patterns and driving forces of non-grain production of cultivated land in Guizhou Province. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1697962. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1697962

Edited by:

Enxiang Cai, Henan Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Linyu Yang, Guizhou Normal University, ChinaHua Shao, Nanjing Tech University, China

Shihong Long, Henan Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2025 Cai, Zhong, Tian, Zhang and Yan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiusheng Zhong, MjAxMzA3MDE1QGd6bnUuZWR1LmNu

Nanjia Cai

Nanjia Cai Jiusheng Zhong1*

Jiusheng Zhong1* Jiahui Tian

Jiahui Tian