- Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, College of Science, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana

Background: Nature Positive Food Production (NPFP) is an emerging framework for linking agricultural productivity with the regeneration of ecosystems. It works toward the restoration of soil health, improvement in biodiversity, and strengthening climate resilience of global food systems. Yet, evidence regarding how NPFP practices perform under a wide range of ecological and socio-economic contexts remains fragmented.

Methodology: This review synthesizes the evidence of nature-positive agricultural practices globally through a PRISMA framing. Searches in Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar include policy and grey literature relevant to the review published between 2010 and 2025. Eligible studies assessed agricultural approaches that presented quantifiable ecological restoration or sustainability outcomes. Of these, 45 studies were included and assessed for methodological quality using the adapted MMAT.

Results: Variations in the ecological and economic benefits exist for different types of farming, including regenerative agriculture, agroecology, agroforestry, climate-smart agriculture, and integrated pest management. This ranges from 15 to 30% increases in soil organic carbon, 20–50% improvements in on-farm biodiversity, and 10–25% improved yield stability relative to conventional approaches. Policies that promote coherence, agricultural investments, and inclusive financing channels have been widely recognized to enable scaling up nature-positive changes, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Conclusion: Nature-positive food production is the science-based pathway to bring ecosystems back to life in a way that secures safe, healthy, and sustainable food supplies. If this approach is to be scaled up globally, then good governance, fair finance, and knowledge platforms will be required that connect ecological regeneration with productivity and resilience.

1 Introduction

Nature Positive Food Production (NPFP) represents an innovative approach to transform agricultural systems which will protect environmental resources instead of causing damage. The research of Hodson de Jaramillo et al. (2023) and DeClerck et al. (2023) demonstrates how NPFP achieves ecosystem restoration through balanced food production systems that maintain soil health and protect biodiversity and manage water resources. The new agricultural framework demonstrates how farming evolved from resource extraction to environmental protection which maintains natural resources while promoting human health. The framework consists of three connected elements which work together to achieve its goals: (1) protecting natural habitats from additional conversion activities and (2) implementing sustainable agricultural practices to preserve ecosystem services and (3) restoring damaged ecosystems through soil and water and vegetation rehabilitation according to achieve Hodson de Jaramillo et al. (2023) recommendations. The established principles create a unified system to achieve biodiversity and climate targets through sustainable food production. The research of Ceddia et al. (2024) and Sher et al. (2024) demonstrates that NPFP stands as a leading factor for large-scale agricultural transformations which address multiple worldwide issues including climate change and biodiversity loss and soil deterioration and food accessibility problems. The implementation of multiple approaches through coordinated methods will strengthen ecosystem resilience while creating sustainable economic opportunities for people according to Niggli et al. (2023) and Brennan (2024). Some of these practices are regenerative agriculture, agroecology, and technology for a circular bioeconomy. According to Rosier et al. (2025) and Demmler and Tutwiler (2024), sample methods of regenerative techniques which improve the water-nutrient holding capacity of the soil, while also leading to lower greenhouse gas emissions, include crop diversification, cover cropping, conservation tillage, and integrated pest management. Other methodologies, which have utilized microbial and biotechnological innovations like biofertilizers, plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, and nano-enabled agrochemicals, have indeed also shown potential in enhancing soil microbial networks and optimizing nutrient cycling, according to Kaushal et al. (2023).

Nature-positive farming is associated with societal and economic benefits. It allows for fairness in development and inclusiveness through participatory innovation and traditional ecological knowledge by empowering smallholder farmers, Indigenous peoples, and local communities (Ceddia et al., 2024). NPFP becomes even more crucial to support people and the planet through reduced needs for artificial inputs, reduced pollution, and promotion of healthier diets (Rahman et al., 2024; Carvalho et al., 2024). These benefits reflect international initiatives under the UN Food Systems Summit and Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, where regenerative and resilient food systems are included as means to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (DeClerck et al., 2023; Niggli et al., 2023).

Though becoming more popular, it is still not being applied as widely. For most smallholders, NPFP faces technical, financial, and capacity constraints at the farm level, while incoherence and the lack of sufficient incentives for sustainable land management characterize the policy environment, issues pointed out by Iqbal et al. (2024) and Petros et al. (2025). Empirical information on how to effectively scale nature-positive initiatives within specific ecological and socio-economic settings is still lacking as pointed out by Ceddia et al. (2024) and Sher et al. (2024). The formulation of national agricultural and food security policies embodying a regenerative approach has been uneven and often disjointed; thus, unable to harness the ecological potential in full that arises from NPFP, as expressed by Demmler and Tutwiler (2024) and Hodson de Jaramillo et al. (2023).

Although the concept of NPFP has achieved increasing global attention, a proper understanding of how such principles are put into practice across varying agroecological and socio-economic contexts is still lacking. Most existing studies focus on isolated practices of regenerative agriculture, agroecology, or sustainable intensification, rather than integrated, holistic approaches that consider biodiversity restoration, productivity enhancement, and strengthening of rural livelihoods concurrently (Ceddia et al., 2024; DeClerck et al., 2023; Niggli et al., 2023). Furthermore, a number of gaps persist in policy alignment, financing mechanisms, and empirical evidence connecting NPFP interventions to clear ecological and socio-economic outcomes (Petros et al., 2025; Iqbal et al., 2024). This review therefore synthesizes existing evidence on NPFP frameworks, their potential for natural capital regeneration, enabling factors, and barriers towards adoption and scalability for transforming global food systems toward sustainability and resilience.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design

This paper represents a systematic review based on the PRISMA framework. The review was carried out to identify, map, and synthesize peer-reviewed and grey literature on strategies that catalyze nature-positive food production with a scope of coverage around the globe, while giving some prominence to evidence from Low and middle Income Countries (LMICs). Members of the review team were Joseph Amoah (first author), Gregory Ngmensoa (second author), and Reginald Annan (third author).

2.1.1 Objectives

1. To identify and categorise key nature-positive agricultural practices documented in academic and grey literature.

2. To assess the evidence supporting the effectiveness and implementation of these practices and to summarise policy implications for scaling NPFP.

2.2 Search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search across major bibliographic databases and institutional sources to capture literature on NPFP. Databases searched included Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Science Direct. We also searched Google Scholar and targeted institutional and policy sources such as Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) repositories and government/policy reports to retrieve relevant grey literature. Searches covered publications in English from 2010 through 2025.

2.3 Search terms and Boolean strategy

Search strings combined terms for the phenomenon of interest (e.g., “nature-positive,” “regenerative agriculture,” “agroecology,” “nature-based solutions”) with outcome and context terms (e.g., “food production,” “food security,” “sustainability,” “low-income,” “middle-income”). An example Boolean string used (adapted for each database syntax) was: (“nature positive” OR “nature-positive” OR “regenerative agriculture” OR agroecology OR “climate-smart agriculture”) AND (“food production” OR food” OR nutrition OR food security) AND (Africa OR Asia OR “low-income” OR “middle-income” OR global).

2.4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.4.1 Inclusion criteria

Papers that evaluate, describe, or discuss agriculture or food system practices explicitly framed as nature-positive, regenerative agriculture, or agroecological, or strategies with demonstrable ecological restoration outcomes. Studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries or studies with broader/global scope that include findings transferable to LMIC contexts. Peer-reviewed articles, policy reports, institutional reports, and relevant grey literature. Publications available in English and published between 2010 and 2025.

2.4.2 Exclusion criteria

Articles focused solely on non-food sectors (e.g., forestry with no link to food production outcomes). Purely technical agronomic studies that lack an ecological or system-level focus (for example, single-factor greenhouse experiments with no ecosystem or policy relevance). Non-English publications and records with no accessible abstract or full text.

2.5 Selection process

The selection process followed a four-step screening pipeline: identification, de-duplication, title/abstract screening, and full-text eligibility assessment.

1. Identification and de-duplication: The initial search identified 276 records. All records were imported into a reference manager (mendeley) and de-duplicated. After de-duplication and an initial title screen to remove clearly irrelevant records, 200 records proceeded to abstract screening.

2. Title/abstract screening: Two reviewers (Joseph Amoah and Gregory Ngmensoa) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Conflicts at this stage were flagged and discussed; unresolved conflicts were escalated to the third reviewer (Reginald Annan) for adjudication. Following abstract screening, 135 records were selected for full-text retrieval.

3. Full-text screening/eligibility assessment: Two reviewers (Joseph Amoah and Gregory Ngmensoa) independently assessed the 135 full texts against the eligibility criteria. Reasons for exclusion at full text were recorded (e.g., wrong outcome, or insufficient methodological detail).

4. The full-text screening resulted in the exclusion of 90 records and the inclusion of 45 studies in the final synthesis. These numbers are reported consistently in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1): Reports assessed for eligibility (n = 135); Reports excluded after full-text review (n = 90); Studies included in qualitative synthesis (n = 45). The PRISMA flowchart file and the screening log with exclusion reasons are provided in the Supplementary materials.

2.6 Data extraction and thematic categorization

The data were extracted using a standardized extraction form implemented in Microsoft Excel. Extracted fields included: author(s), year, study location, study type/design, agroecological context, nature-positive practice(s) described, reported ecological and socio-economic impacts, methodological quality indicators, and policy or implementation recommendations. Extracted data were cross-checked between the two primary reviewers; discrepancies were resolved by discussion and, when necessary, by the third reviewer.

Extracted items were grouped into thematic categories for synthesis. The primary thematic groups used for analysis were: regenerative agriculture; agroecology; agroforestry; climate-smart agriculture; integrated pest management; agricultural investments; and agricultural policy and governance.

2.7 Software used

Mendeley was used a reference manager whilst excel was used for the extraction of data. PRISMA flow diagram was prepared using PRISMA template.

2.8 Quality appraisal

We appraised methodological quality using a transparent, reproducible, simplified adaptation of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) appropriate for a heterogeneous evidence base. For each study we assessed five core domains adapted from MMAT and conventional bias criteria:

(1) Clarity and appropriateness of research questions/objectives,

(2) Appropriateness of study design to the question,

(3) Adequacy of sampling and data collection methods,

(4) Clarity and completeness of outcome reporting, and

(5) Consideration of confounders and sources of bias.

Each domain was scored 1 (meets criterion) or 0 (does not meet). Total scores therefore ranged 0–5. Based on the total score, studies were classified as: High quality (Niggli et al., 2023; Ceddia et al., 2024), Medium quality (DeClerck et al., 2023; Sher et al., 2024), or Low quality (0–1). Two reviewers (Joseph Amoah and Gregory Ngmensoa) independently rated each study; disagreements in ratings were reconciled by discussion and, if necessary, finalized by the third reviewer (Reginald Annan). A copy of the appraisal rubric and per-study scores is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.9 Data synthesis

Given the heterogeneity of study designs, contexts, and outcome measures, we used a narrative synthesis approach guided by the thematic groups identified in Section 2.6. Quantitative results (for example, measured changes in soil organic carbon, biodiversity indices, or crop yields) were extracted and tabulated to enable cross-study comparison where possible; quantitative summaries are presented alongside qualitative syntheses of implementation experiences, barriers, and policy implications. Where data permitted, we highlighted comparative findings (e.g., approaches associated with larger biodiversity gains, or with stronger socio-economic co-benefits). Connections and interlinkages among themes (for example, agroforestry as a nature-positive practice that also supports climate-smart objectives) were emphasized in the synthesis. All syntheses explicitly reference study quality classifications so that interpretations account for methodological robustness.

2.10 Software and reproducibility

Reference management and de-duplication were performed in a bibliographic reference manager (Mendeley), and data extraction was implemented in Microsoft Excel (see Table 1)

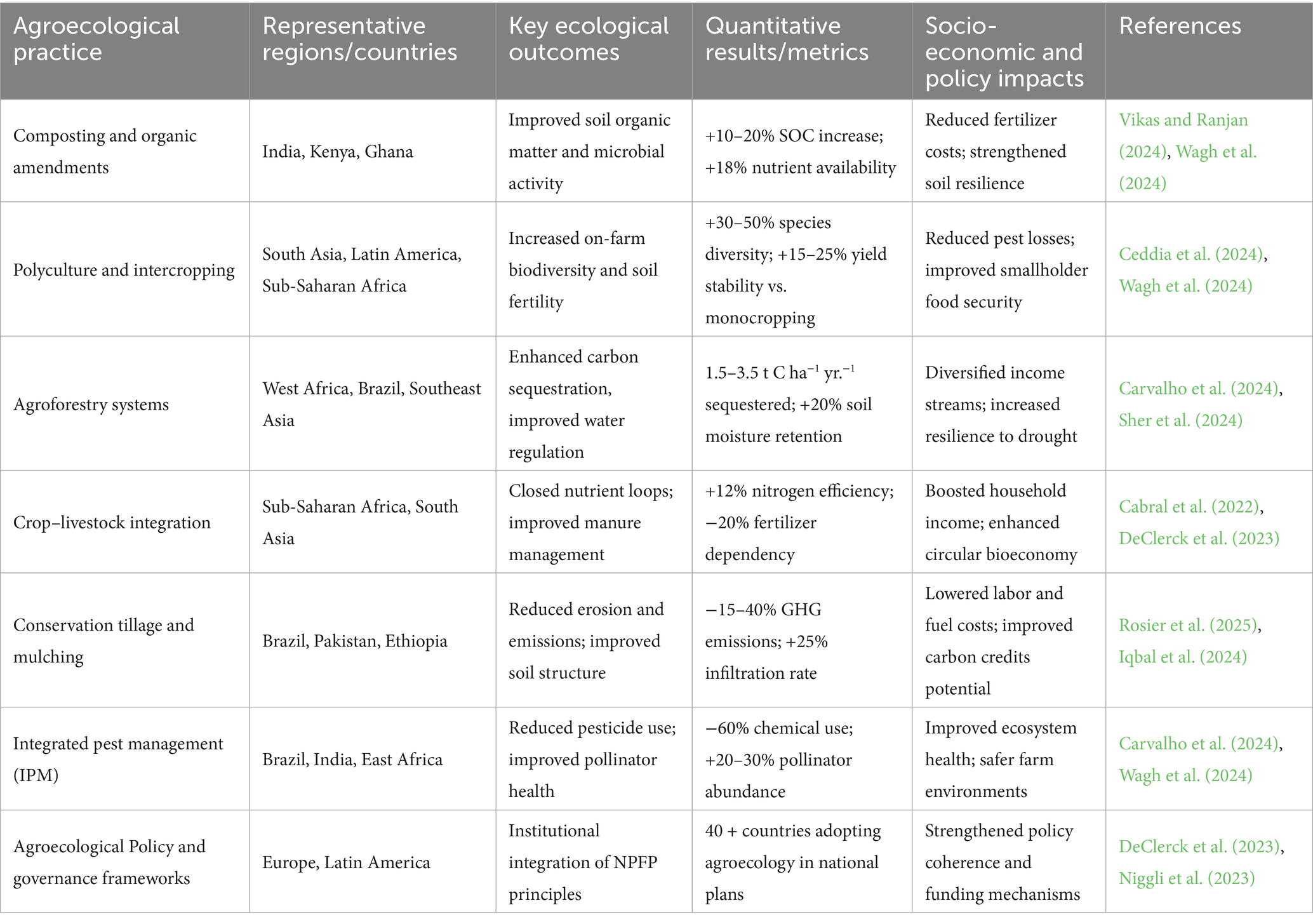

Table 1. The included studies by country/region, nature-positive practices, reportedoutcomes, and methodological quality.

3 Results

3.1 Regenerative agriculture

Regenerative agriculture has evolved over decades from agroecological and traditional land stewardship systems that predate industrial farming. Although its principles such as crop diversity, soil cover, and ecological balance can be traced back to indigenous and ecological land management practices of the 1930s, it entered mainstream discourse only recently, particularly through global policy dialogues such as the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit, COP26, and CBD COP15 (Cabral et al., 2022; Hodson de Jaramillo et al., 2023; Alavalapati et al., 2014). The approach has emerged as a key component of nature-positive food production (NPFP), emphasizing the restoration of ecosystem functions degraded by chemical-intensive and mechanized agriculture (Sher et al., 2024).

Regenerative agriculture encompasses practices and processes that restore soil organic matter, enhance biodiversity, and make ecosystems more resilient. This includes cover cropping, crop-livestock integration, conservation tillage, composting, agroforestry, rotational grazing, and crop diversification. These all link with each other to improve soil health and enhance its water-holding capacity, hence relying on fewer external inputs. This, along with the development of techniques that enhance nutrient cycling, soil microbial activities, and carbon sequestration, has been improving the ability of agroecosystems toward self-repair (Nair et al., 2021). Regenerative systems have been found to enhance soil organic carbon by 0.3–1.0 t C ha−1 yr.−1, increase water penetration by 20–60%, and enhance biodiversity by 30–40% compared to conventional systems.

All these advantages of regenerative farming also link ecological and economic factors. It enhances soil structure, nutrient cycling, and the diversity of life from tiny bacteria to pollinators and larger trophic species. It will benefit the livelihoods of people in rural areas by making food more secure and the environment more stable because of the reduction in input prices and keeping productivity stable during times of climate stress. Some studies in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America show that use of regenerative approaches with agroforestry and/or conservation agriculture has resulted in production gains of 10 to 20% and up to a 35% reduction in fertilizer use (Alavalapati et al., 2014).

Comparative analyses suggest that regenerative agriculture outperforms principal NPFP methodologies in terms of biodiversity and soil carbon gains, outperforming traditional intensification and even organic farming in some respects. It also serves as a natural carbon sink; global modelling indicates that, with broad implementation, sequestration could reach 3–8 Gt CO2-equivalent annually. The ecological benefits translate into measurable contributions to the climate mitigation and land restoration goals of the UNFCCC and Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (Alavalapati et al., 2014).

Although it has considerable potential, the major problems are not easily solved as far as wider application, especially in LMICs, is concerned. Some of the significant issues impeding the process are lack of access to finance and technical expertise, poor services for extension support, insecure tenure of land, and market incentives which are negligible for ecosystem-based production (Petros et al., 2025; Ceddia et al., 2024). Besides, the shift often demands investments that last for several years before benefits are completely realized, which makes it difficult for smallholders who need money right away (Iqbal et al., 2024).

The possible avenues through which regenerative agriculture can be popularized throughout the world in the future include:

1. Policy alignment and incentives: linking subsidies to carbon credits to ecosystem restoration outcomes (Demmler and Tutwiler, 2024)

2. Combining studies; using standardised measures to measure the long-term increases in soil carbon and biodiversity (Niggli et al., 2023)

3. Capacity development: putting money into farmer-led innovation and sharing knowledge in a way that everyone can take part.

4. Getting money: making green investment mechanisms bigger so that smallholders do not have to worry about the risks of making changes (Petros et al., 2025).

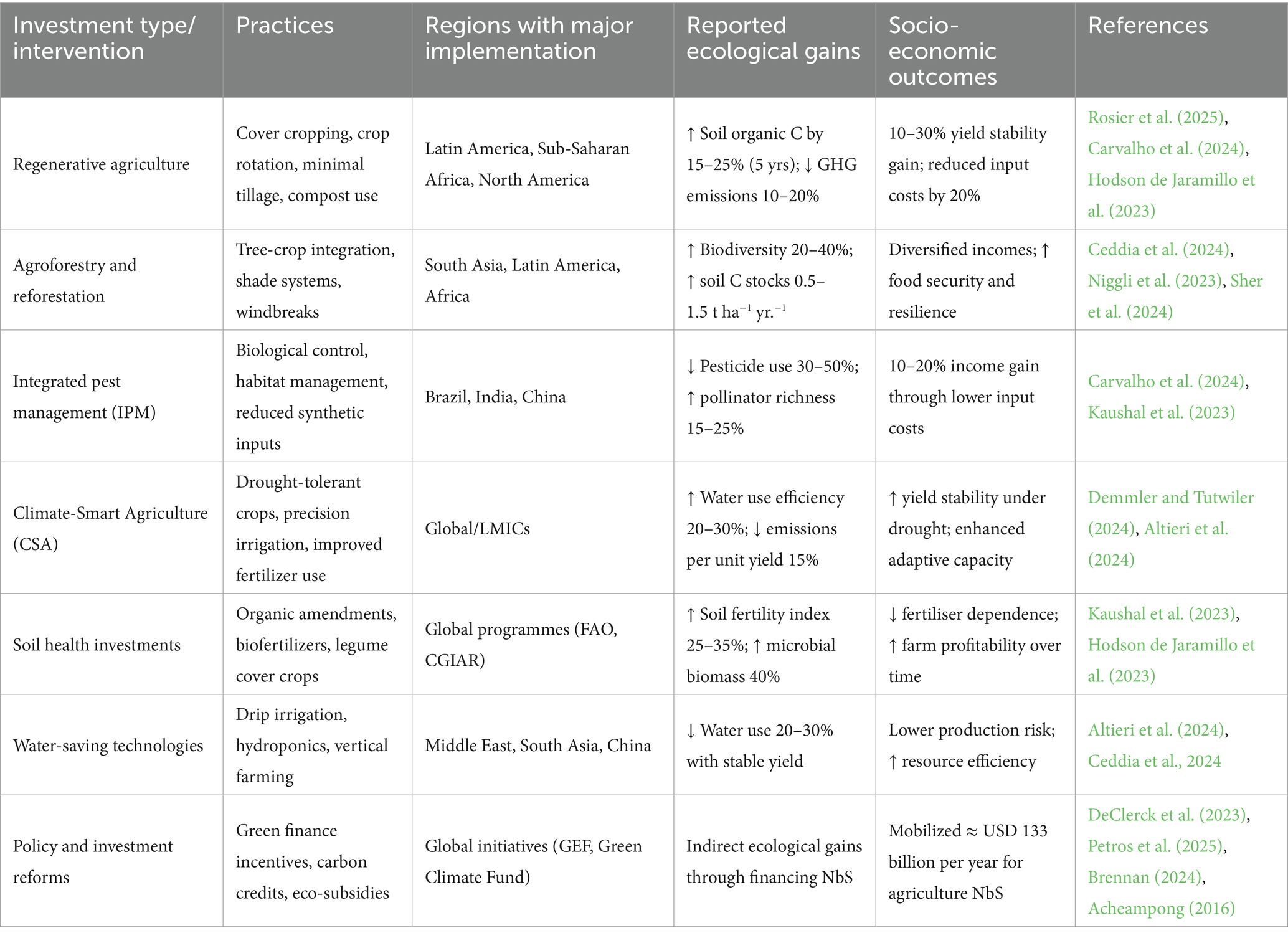

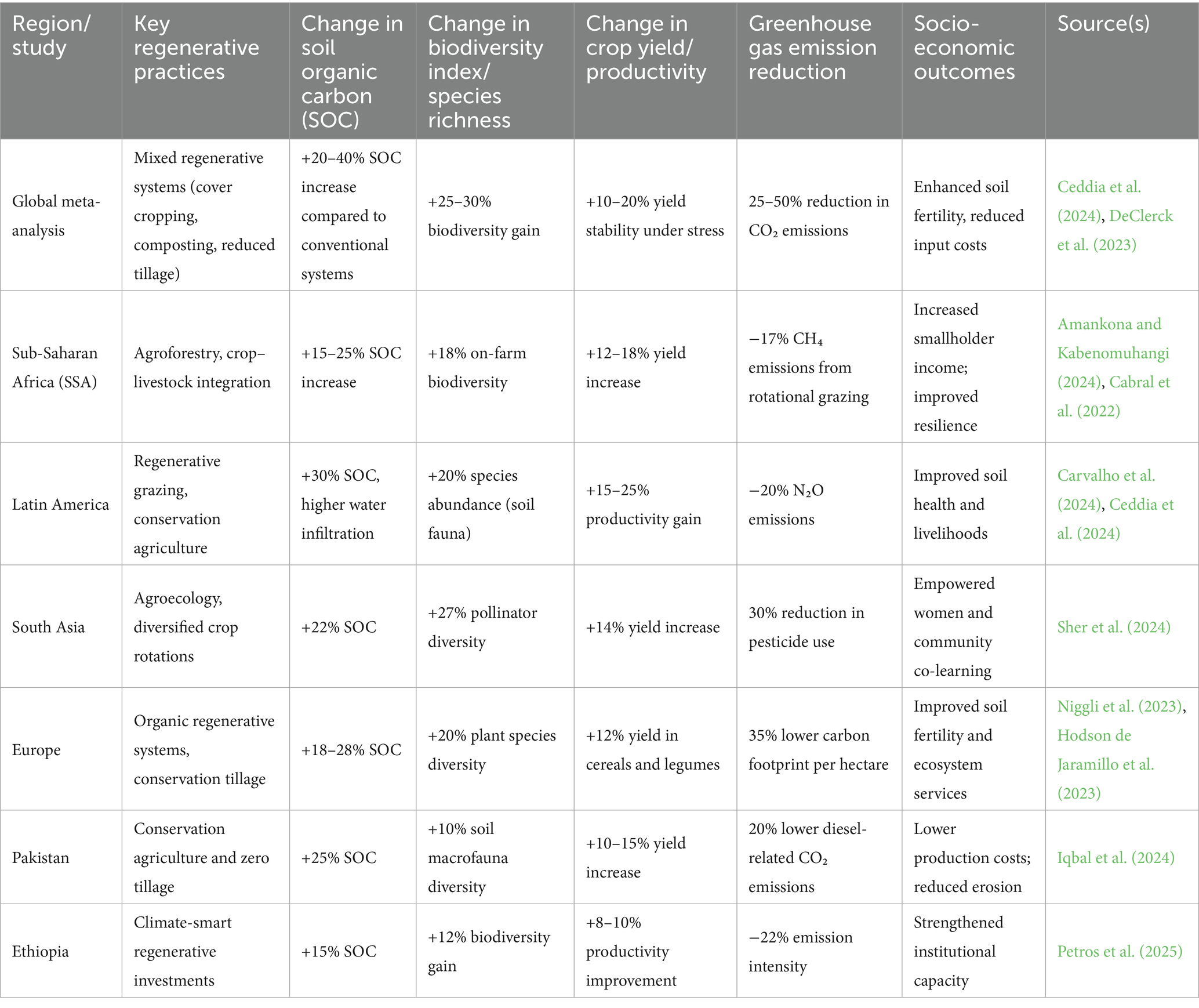

Regenerative agriculture is one of the most empirically validated and versatile approaches within NPFP, balancing ecological integrity with socio-economic sustainability. Based on evidence that it can restore natural capital, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and enhance resilience, it merits a central place in the global shift toward food systems that will work for both people and the environment (Hodson de Jaramillo et al., 2023; Ceddia et al., 2024; Sher et al., 2024) (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparative quantitative outcomes of regenerative agriculture for nature-positive food production.

3.2 Agroecology and nature-positive food production

Agroecological agriculture is a broad approach that incorporates ecological functions into farming methods for biodiversity conservation, nutrient cycling in the soil, cycling of resources, and application of traditional knowledge (Cabral et al., 2022). It thus employs sustainable, robust, and ecologically appropriate modes of food production (Wagh et al., 2024). It also encompasses fairness in social and economic matters. Besides productivity, cultural values and food sovereignty have been added to its definition. Agroecology is a complex concept that links scientifically sound management of agroecosystems to a commitment to transforming food systems as a whole (DeClerck et al., 2023). It emphasizes things such as polyculture, mixing crops and animals, agroforestry, composting, and conservative tilling for maintaining and enhancing soil fertility (Wagh et al., 2024). The most comprehensive tests carried out under varied conditions around the world reveal that agroecological farms can raise biodiversity by 30–40% and organic carbon in the soil by 15–20%, compared to conventional systems (Sher et al., 2024; Ceddia et al., 2024).

It brings agriculture back in line with social justice and ecological integrity by lowering power imbalances and embracing a wider range of knowledge systems, such as those from Indigenous and local communities (Niggli et al., 2023). Agroecology helps reduce the use of synthetic inputs, promote soil biological activity, and give power to rural people, especially smallholders in low- and middle-income countries (Ceddia et al., 2024; Petros et al., 2025). It encourages food production that is good for the environment by promoting functional biodiversity both above and below ground, creating habitats for pollinators, and using fewer synthetic chemicals that upset the balance of ecosystems (Wagh et al., 2024).

Some of the Agroecological activities that greatly enhance soil fertility, prevent erosion, and boost water infiltration include intercropping, composting, mulching, and agroforestry. Quantitative investigations show that intercropping systems raise soil organic matter by 20–35%, while agroforestry can sequester up to 5.5 tonnes of carbon per hectare yearly, according to Carvalho et al. (2024) and Sher et al. (2024). Wagh et al. (2024) and Ceddia et al. (2024) present these technologies as not only maintaining high yields but helping in the restoration of degraded soils and ecosystems, hence raising productivity in the long term without environmental degradation.

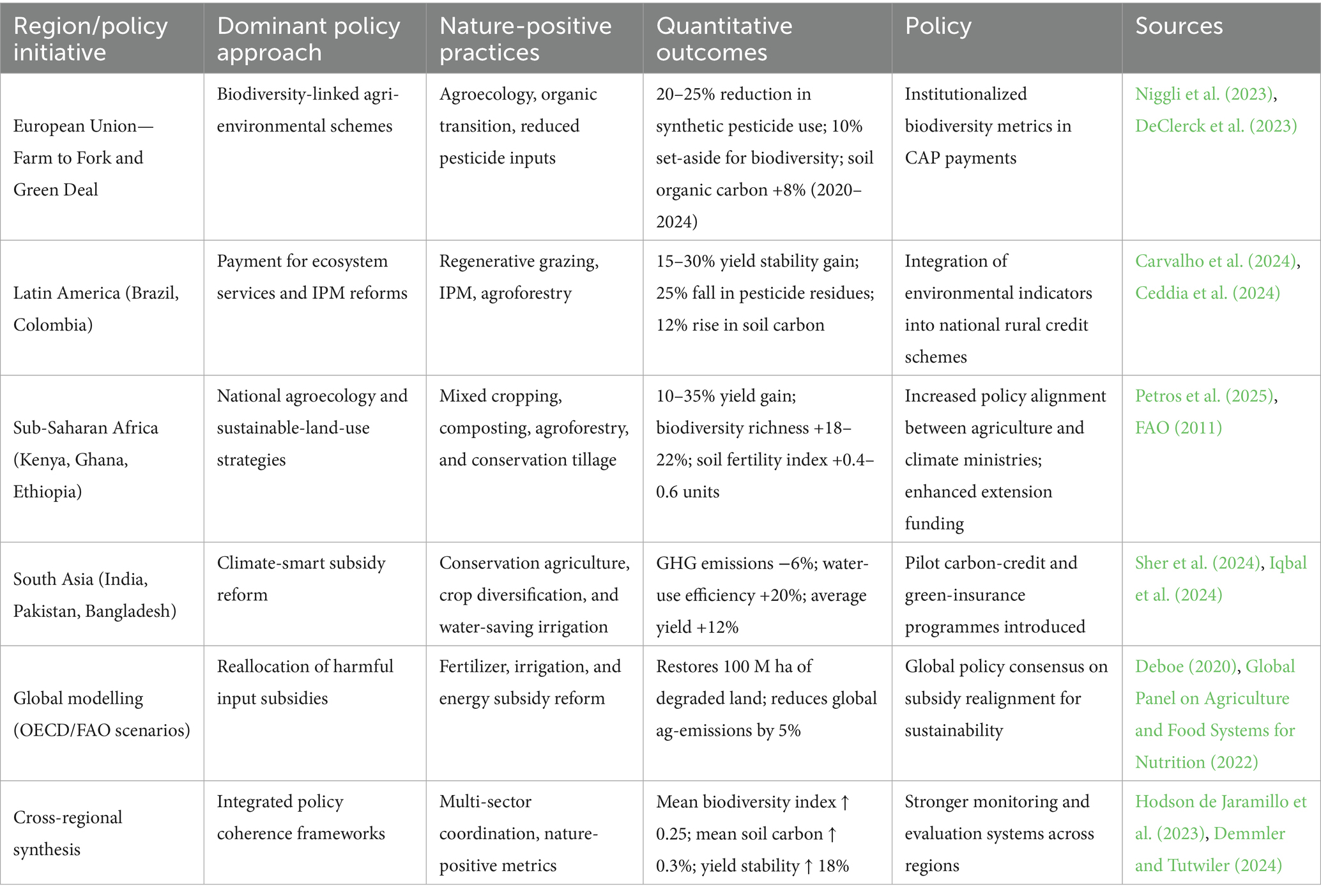

Agroecology is a smart way to deal with and improve climate change. Some estimates say that minimum tillage, organic amendments, and crop rotation can cut greenhouse gas emissions by up to 25% compared to traditional methods. Agroforestry systems and mixed cropping make microclimates that are good for plants, help hold water, and make plants more resistant to changes in temperature. Agroecology has proven beneficial; however, many problems are inhibiting its scaling up, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Problems include inability to secure funding, inadequate institutional support, and policy frameworks that are very often favoring input-intensive models over ecological methodologies-for example, see Petros et al. (2025) and Iqbal et al. (2024). Because of improper investment in research funding and extension services, there is not enough technical capacity among the smallholders to enable them to make a transition into agroecological practices. This is noted by DeClerck et al. (2023). Problems persist with the global supply chain, and there are few drivers for people to buy sustainably produced products, which makes it less likely that many people would switch to using them. As discussed by Ceddia et al. (2024), the future will have to be about making it easier for agroecological transitions to happen. This could mean more participatory research, adding agroecology to national agricultural investment plans, and providing finance to restore ecosystems. This might be achieved, for example, as discussed by Demmler and Tutwiler (2024) and Petros et al. (2025) to speed up the worldwide move towards nature-positive food production, it will be important to strengthen farmer networking, encourage South to South information sharing, and incorporate ecological principles into trade and food laws (Alavalapati et al., 2014) (Table 3).

3.3 Investment in agriculture

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) investments in agriculture have become an especially global strategy that changes agricultural systems in pursuit of resiliency, productivity, and environmental friendliness. In other words, investment in such interventions involves the flow of money and technical know-how into farming approaches that restore ecosystems while remaining profitable. It is assumed that at the global level, NbS investments in agriculture are more than USD 133 billion annually, which is over a third of all climate-related finance. These projects focus on things like reforestation, agroforestry, regenerative agriculture, wetland restoration, and soil conservation. These are noted to be inexpensive to put in place with large long-term benefits to the environment.

The nature-positive investment concept does not set environmental conservation against agricultural output; it incorporates ecological restoration into food production systems. It places nature first as a type of “green infrastructure” that’s very important for adapting to climate change, ensuring enough food, and ensuring people are able to make a living in an environmentally positive way. As an example, cover cropping, crop rotation, and limited tillage in regenerative farming led to a 15–25% increase in soil organic carbon over 5 years. This has reduced production costs and increased yields. Agroforestry systems raise biodiversity by 20–40% compared to traditional monocultures. The diversity in this regard contributes to stabilizing household incomes and making food supply more resilient (Alavalapati et al., 2014).

Agriculture can reduce water consumption by 20–30% without yield loss through water-saving technologies such as hydroponics, drip irrigation, and vertical farming (Altieri et al., 2024; Nair et al., 2021). Investment in soil through organic amendments, biofertilizers, and cover crops that fix nitrogen enhances the fertility of the soil, microbial diversity, and carbon sequestration. This further reduces reliance on synthetic fertilizers (Kaushal et al., 2023; Demmler and Tutwiler, 2024). Such innovations enhance low-emission farming and contribute to achieving goals under the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Nevertheless, NbS investments keep growing from a very low base, especially in low- and middle-income countries, due to a lack of access to green finance, low institutional capacity, and unclear policies. Many smallholder farmers lack access to credit collateral, extension support, or markets willing to purchase goods that are produced in a manner that is conducive to environmental sustainability. This is exacerbated by the lack of valuation data on ecosystem services and unclear governance. To address these knowledge gaps, agricultural investment planning, environmental accounting, and targeted finance for farmer-led innovation in carbon-smart production should be effectively integrated. Future initiatives focus on the design of blended finance models that amalgamate public and private capital to de-risk investments in regenerative agriculture and agroecology. Global alliances-between governments, agribusinesses, and research institutes-could accelerate the diffusion of nature-positive concepts more rapidly across more economies. For example, the work of General Mills with other companies demonstrates how industry-led investment in soil health has the potential to make farming more profitable while restoring ecosystems. Long-term scaling of NbS-aligned agricultural finance has multiple benefits: reduction of climate change, restoration of biodiversity, improvement of rural livelihoods-all these are needed to achieve a nature-positive global food system by 2050 (Nair et al., 2021) (Table 4).

3.4 Integrated pest management

Integrated pest management (IPM) is a well-known method that uses biological, cultural, mechanical, and chemical methods in managing the population of pests while maintaining ecosystem health (FAO, 2023; Zhou et al., 2024). On the other hand, IPM focuses on nonchemical control methods involving preventive and ecological strategies like rotation of crops, biological control, utilization of varieties resistant to pests, and preservation of beneficial species (Angon et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2024). This is a multifunctional approach that seeks to reduce the population of pests below the economic threshold in order to protect biodiversity, human health, and soil integrity (Ministry of Food and Agriculture, 2022).

Most of these methods have shown that IPM reduces pesticide use by 30–50% while increasing yields by 10–20% in many different cropping systems around the world. This is particularly the case when combined with agro-ecological principles (Ceddia et al., 2024; Niggli et al., 2023). Ecological engineering integrated pest management in Asia’s smallholder rice systems was able to reduce the frequency of pest outbreaks by 40% with improved net returns over traditional methods (Sher et al., 2024). Similarly, studies in Latin America and Africa record that biodiversity has significantly increased, especially regarding more pollinators and natural enemies, once chemical inputs were reduced and vegetative cover improved (Carvalho et al., 2024; Angon et al., 2023). Such findings confirm that IPM is directly contributing to nature-positive food production through restoring soil microbiota, conserving natural predators, and minimizing nontarget mortalities (Zhou et al., 2024).

Problems still exist, though, especially in low- and middle-income nations where integrated pest control does not work well because their economies are weak, their extension services are poor, and farmers do not get adequate training. High initial prices for biocontrol agents, limited access to resistant seed varieties, and an overall lack of monitoring infrastructure are other problems that can hinder adoption (DeClerck et al., 2023). Policy fragmentation and the absence of incentives make this sector less attractive for investment in integrated pest management solutions. For nature-positive agriculture to genuinely grow, institutions need to be able to do more and IPM needs to be included in national strategies for crop protection and climate change (Acheampong, 2016).

Future trends focus on integrating IPM with emerging digital technologies and farmer-led monitoring platforms that facilitate decision-making for farms. Brennan (2024) discusses the scaling up of relationships between public research institutes and private agricultural technology (agritech) companies to speed up the creation of biocontrols and bio-pesticides that function well in certain locations (Kaushal et al., 2023). Combining IPM projects with large-scale regenerative farming programs, like the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, would probably help both productivity and ecosystem restoration (Hodson de Jaramillo et al., 2023; Niggli et al., 2023).

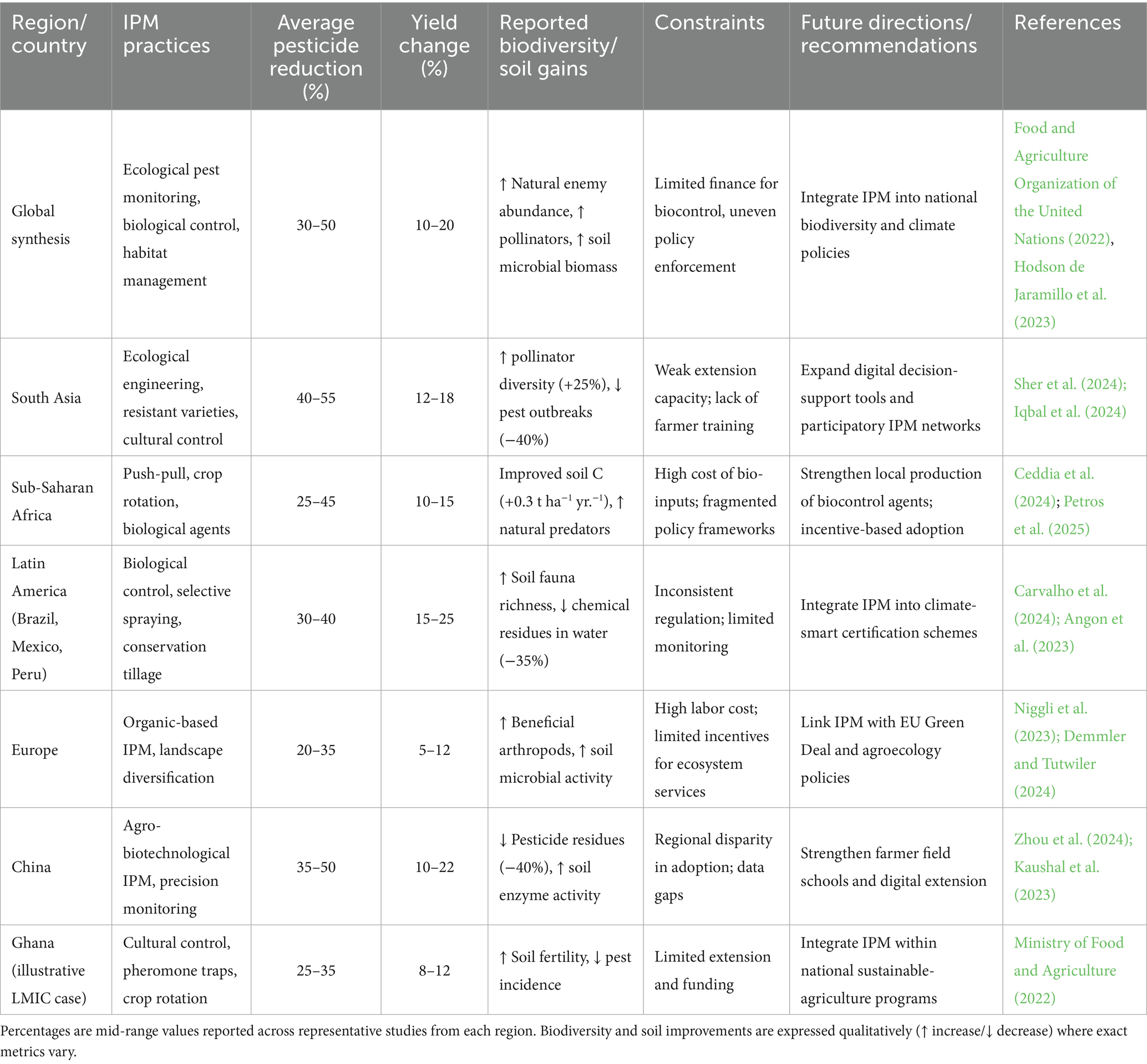

IPM is thought to be one of the finest ways to make food production more nature-friendly because it has ways to avoid difficulties and focusses on ecosystems. IPM helps maintain biodiversity a lot by using less pesticides, making soil more fertile, and keeping ecosystems in balance. This is important for long-term global food security (Table 5).

Table 5. Global evidence of integrated pest management (IPM) contributions to nature-positive food production.

3.5 Agroforestry

Agroforestry is a way of using land that combines trees with cropland and cattle in order to improve the health, productivity, and resilience of the agro-ecosystem. Integrating forestry with agricultural methods enhances biological interactions among species, leading to increased nature-positive food production. According to the FAO, more than 1.2 billion people use agroforestry, with an area of more than 1 billion hectares. It provides critical ecosystem services like conserving biodiversity, cycling nitrogen, and storing carbon.

It has been proven to work in many different locations. For example, in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, agroforestry systems containing native and commercially important tree species improved soil organic carbon by 35% and crop yields by 20% over a 10-year period while increasing biodiversity and water retention (Fahad et al., 2022). Put differently, Farpón et al. (2022) found that agroforestry on charlands in Bangladesh reduced soil erosion by 40%, making the households 25% more food secure. This thus shows that this could be a nature-based strategy for halting flooding in some areas. Lastly, Ceddia et al. (2024) found that the output levels of smallholder agroforestry systems in East Africa stood 15 to 30% higher than what had initially been there, using up to 50% less chemical fertilizers.

There are a number of ways that agroforestry is healthy for the environment. Trees with deep roots take nutrients from the soil layers below them and transfer them back into the soil layers above them, making them richer. Adding organic matter to the soil through leaf litter increases the carbon content and microbial activity of the soil, two key markers of healthy soil. Plants with legumes, like Gliricidia sepium and Leucaena leucocephala, take nitrogen from the air and store it in their roots. This means that plants growing with them can get nutrients directly from the soil rather than relying on synthetic fertilizers. Adding trees helps keep microclimates stable, reducing wind erosion and allowing more rain to soak into the ground. This makes plants use water more efficiently and makes them more drought-resistant.

Depending on how they are managed, agroforestry can store 2 to 9 metric tonnes per hectare of carbon each year. They can also increase the number of species by up to 60% in comparison with landscapes with monoculture plantations (Sobola and Amadi, 2017). These findings suggest that agroforestry might contribute to nature-positive food production. This is particularly important for the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework goals on biodiversity and climate change worldwide.

Besides its environmental advantages, agroforestry entails several social and economic benefits. This means that farmers should grow different kinds of crops so they can sell commodities like fruits, nuts, fuelwood, and lumber. In this situation, they are less likely to be affected by changes in the weather or the market (Ali et al., 2024). In many low- and middle-income countries-especially in Africa and Asia-agroforestry brings in as much as 43% of rural household income. It also makes more food available during the lean season (FAO, 2023). These benefits make lives more resilient, which is in line with the principles of nature-positive production, which aims at restoring natural systems while promoting economic growth.

Agroforestry is an underutilized agricultural system that has a range of benefits. Farmers in developing countries often lack the necessary means to practice agroforestry due to a lack of security of land tenure, money, and technical skills. Poor and nonsensical policies, lack of or minimal extension services, and exclusion from national agricultural strategies are other factors hindering its scaling-up. From another perspective, trees take long to generate income; hence, small holders are unlikely to adopt trees unless there is a clear reason to.

Other future directions for agroforestry include integrating it into national climate-smart agriculture frameworks, facilitating people’s access to green finance, and investing in long-term monitoring systems on soil and biodiversity. Closer collaboration between the government, private sector, and local communities can fast-track the transition to wider-scale adoption of nature-positive practices. Digital tools like geospatial mapping and participatory decision platforms are also opening up new ways to grow agroforestry while keeping the ecosystem in balance (Niggli et al., 2023).

Agroforestry is a great example of nature-positive food production since it may improve productivity, resilience, and ecological regeneration all at the same time. Agroforestry is one of the few ways to cultivate that serves more than one purpose. It is one of the finest methods to make farming more sustainable all around the world, as long as there are clear laws, financial incentives, and platforms for innovation that everyone can use (Sobola and Amadi, 2017) (Table 6).

Table 6. Comparative evidence on agroforestry outcomes for nature-positive food production across regions.

3.6 Climate-smart agriculture and its role in enhancing nature-positive food systems

Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) encompasses system-based integrated approaches whose initiatives are geared toward increasing agricultural productivity in an environmentally friendly way, increasing the robustness of farms against climate change, and, where possible, reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Tadesse et al., 2021; Mlengule, 2023). It effectively manages water and biodiversity resources, alongside soil, in ways that are efficient. CSA is yet to be performed at a global scale but is a key driver of nature-positive food systems through the combination of agricultural intensification with environmental regeneration and climate adaptation at that level (Ceddia et al., 2024; DeClerck et al., 2023).

Evidence from many parts of the world indicates that CSA has numerous benefits. For example, on-farm trials in Ethiopia demonstrated that conservation farming resulted in a 35–45% increase in soil organic carbon and a 25% increase in crop yields compared to traditional farming methods. In Ludewa District, Tanzania, minimum tillage, mulching, and agroforestry have made the soil hold more water, about 30%, and cut down on erosion by 40%. Other research from South Asia and Latin America supports the finding that crop variety, integrated nutrient management, and agroforestry enhance land productivity along with its structure and biodiversity.

The main ways that CSA helps nature include protecting soil and water, managing land in a way that is good for the environment, and improving organic soil. Practices that include contour farming, intercropping, use of organic fertilizers, and decreased tillage repair degraded landscapes and sustain productivity without the environmental costs typical of intensive agriculture. In Kenya and Nepal, applying the principles of CSA increased the availability of nitrogen and phosphorus in the soil by 20–40%, while carbon sequestration also increased by the same amount. Agroforestry, being the major component of CSA, provides more environmental services in terms of shade, fodder, and nitrogen fixation, which help in maintaining soil health and supporting biodiversity.

CSA has benefits for society and the economy as well as the environment. By diversifying crop portfolios, stabilizing yields during climate stress, and relying less on synthetic inputs, it makes households more resilient and lowers production costs (Sher et al., 2024; Iqbal et al., 2024). Smallholder farmers in LMICs who practise CSA have seen their income grow by as much as 10 to 30% since the land is more fruitful and they spend less on inputs (Demmler and Tutwiler, 2024). The integration of productivity, resilience, and mitigation in CSA shows how nature-positive agriculture may help both people and ecosystems at the same time (DeClerck et al., 2023; Niggli et al., 2023).

Even with many positives, there are still considerable problems with the adoption of CSA by people. In most low-income nations, access to climate data, appropriate financial options, institutional support, and extension services is limited (Petros et al., 2025). The major factors contributing to their low adoption include the high initial cost of constructing soil conservation structures, requiring much labor, and the absence of market incentives (Ceddia et al., 2024). In addition, policy fragmentation and a lack of concerted national-level CSA programs thwart progress on the scaling of successful practices (Demmler and Tutwiler, 2024).

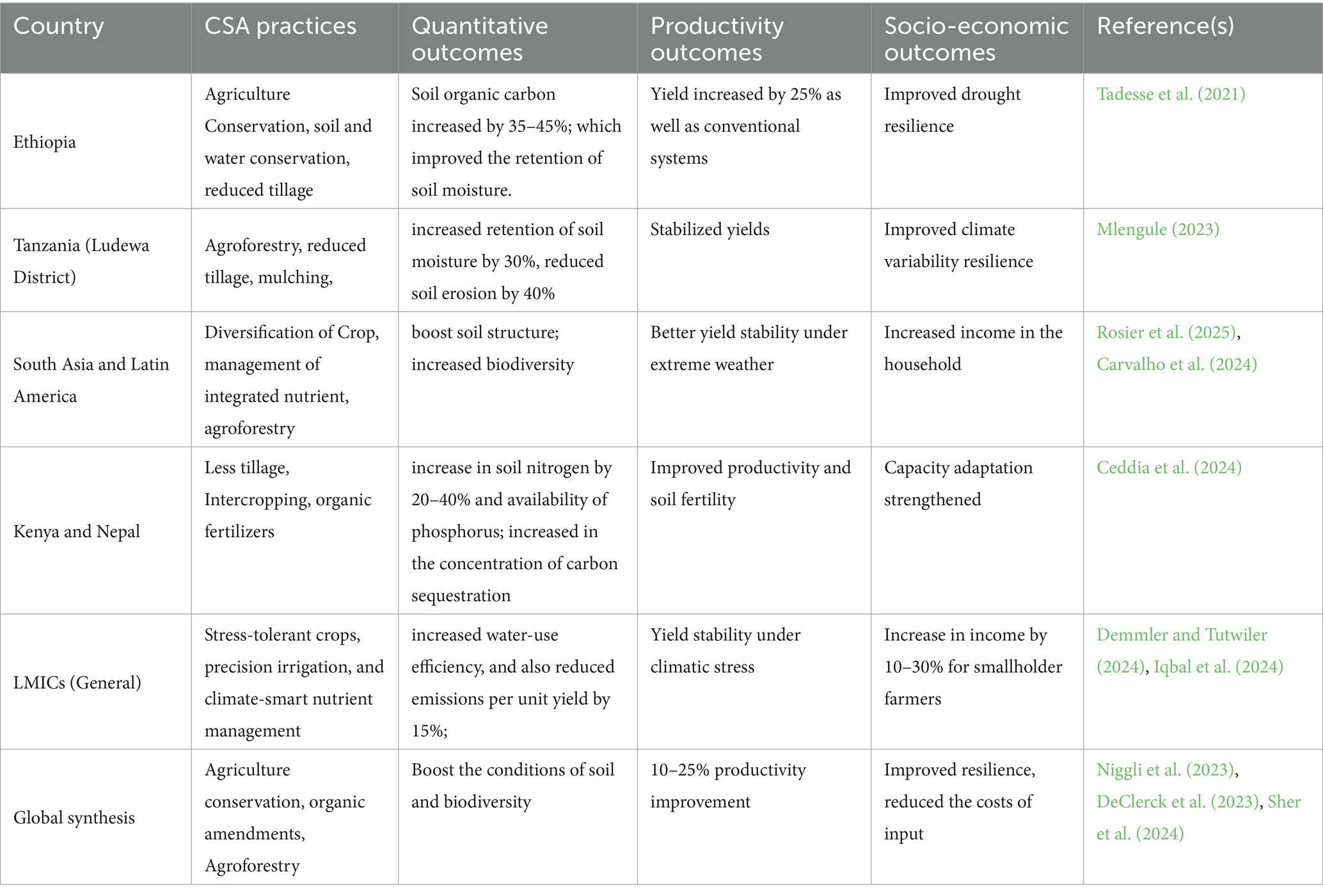

Scaling up CSA through enabling policies, climate finance, and knowledge-sharing networks that connect scientific, local, and indigenous knowledge systems will be very important in a world moving toward nature-positive food systems. In order to get more people to use new technologies, governments, research institutes, and farmers’ organizations should work together across sectors more, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Future work should also focus on quantifying ecosystem service contributions of CSA, like carbon sequestration, efficient water use, and biodiversity enhancement to support evidence-based policy decisions that accelerate the transition toward regenerative, resilient global food systems (Table 7).

Table 7. The quantitative evidence of the contribution of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) to nature-positive food production.

3.7 Government agricultural policy and its role in boosting nature-positive food production

The agricultural policy of the government turns the land into an ideal place for food production and long-term storage. It, in turn, stipulates legal, institutional, and financial parameters for the management of water, land, and biodiversity in farming regions. In developing and implementing planned agricultural policies around the world, such actions can support the transition of food systems away from methods that are unproductive, using-up too many resources and harming the environment. It needs to support perennial systems that are regenerative, of high biodiversity, and better in yielding long-term output. This will alter the rules with regard to land and technology use, change market incentives, and lead public and private investment that could either support or damage nature-positive outcomes.

But biodiversity and climate change goals throughout most countries and regions are gradually aligning with agricultural policy. Examples include the European Union’s Green Deal and Farm to Fork Strategy, which have nature-healthy goals: the use of fewer pesticides, bringing carbon back into the soil, and increasing biodiversity. The building of national agroecology frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America has in turn seen yield gains of up to 30%. They are seeing that the organic matter in the soil is growing and there are more pollinators. The examples above show that if ecological objectives are included in agricultural policy, then both production and ecosystem health can be furthered in parallel. But projects can become very fragmented if this balance between restoring the environment and industry is not apparent in the way policies work together.

Agricultural policy can also help when the markets and the environment are not functioning well. For instance, eliminating perverse input subsidies that cause farmers to overuse water or fertilizer, and establishing performance-based incentives based on sustainability criteria, may help farmers adapt their practices to be more regenerative. If we shift 10–15% of the existing agricultural subsidies into environment-improving investments, then over 100 million hectares of degraded land can be restored and reduce global agricultural emissions by over 5%. Reforming how governments manage money and ensuring that clear rules for tracking will facilitate actions in many places that are positive for the environment and biodiversity.

Everybody should be able to help set the rules. Current studies in Ghana, Brazil, and India have demonstrated that direct agricultural policies supporting small-scale farmers, women, and indigenous communities increase the adoption of agroecological and regenerative approaches by 25–40% (Sher et al., 2024). This participatory governance, involving farmers and local institutions in policy decisions, has been fundamental to scaling up nature positive programs while aligning national objectives with the real state of the environment (DeClerck et al., 2023; FAO, 2011).

However, there are still some very serious issues in developing nations. This involves access to finance and technology, extension services, conflicting rules across ministries, and poor means of implementing policies that make the scaling up of nature-positive treatments extremely challenging to achieve, according to Iqbal et al. (2024) and Petros et al. (2025). The governments are also challenged to monitor performance in some policy initiatives due to a lack of credible information on soil health and biodiversity indicators and ecosystem services as argued by Ceddia et al. (2024). The above limitations require that for the nature-positive pledges to be enhanced, rigid monitoring approaches become absolutely necessary, complemented by coordination between different sectors.

In this respect, agricultural policies in the future will have to incorporate measurable ecological indicators in agricultural planning and subsidy frameworks, such as soil organic carbon, water-use efficiency, biodiversity indices, and others. According to Kaushal et al. (2023) and Altieri et al. (2024), we have to spend more money on research, digital monitoring, and outreach to farmers to build evidence-based policies that are adaptable. Policies also include things that make people stronger, including climate-smart insurance and green financing mechanisms that protect small farmers from climate shocks and help restore ecosystems at the same time. Other examples are Demmler and Tutwiler (2024) and Petros et al. (2025) the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition and FAO’s Agroecology Knowledge Hub, among other things, could help people work together better across the world. This would make it easier and quicker to learn about policy, investment, and how to make food production better for the environment around the whole world. Good agricultural policy will finally make the world’s food systems better for the environment. With many people involved in creating and delivering this kind of policy, it may have the additional effects of making economies fairer, more resilient to climate change, more productive, and restoring life to ecosystems (Table 8).

4 Discussion

The big transition towards NPFP brings together the restoration of the environment, ensuring adequate food for all, and the survivability and thrivability of its people and businesses. To realize these outcomes at the regional level, the approach should be site-specific and involve both environmental and economic considerations. The experiences from Ghana are significant, but data from Asia, Africa, and Latin America and Europe shows this is only the beginning of how nature-positive systems could grow internationally.

Regenerative agriculture is becoming a huge part of NPFP around the world. Cover crops, reduced tillage, and compost-based fertility control all contribute to maintaining healthy soil. This increases the quantity of organic carbon in the soil, making it even more fertile. Studies done in Brazil, Kenya, and India reveal that regenerative approaches have increased soil organic carbon by 15–30% and yields by 10–25%, compared to conventional procedures. These also support studies undertaken in Ghana that show regenerative practices have enhanced soil structure, biodiversity, and drought resilience (Fahad et al., 2022). Even as these developments are very good, there are still challenges that need to be fixed before more people can use them. This is especially true in low- and middle-income countries, where there are many huge resource problems that exist, including lack of finance, technical support, and policy coordination. Global study shows that in order for these systems to grow sustainably, there is a requirement for regulatory support, blended finance, and farmer-led innovation.

This would make a lot of sense if you used the multi-dimensional framework of agro-ecological agriculture, which balances productivity with ecological integrity. Agroecological systems, such as intercropping, agroforestry, and composting, could increase biodiversity by 30–50% and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 40% compared to farming that is very input-intensive (Wagh et al., 2024; Vikas and Ranjan, 2024). Agroecology offers ecological benefits and social participation by empowering smallholders, especially women, and revitalizing indigenous knowledge systems (Cabral et al., 2022). Evidence from Latin America and East Africa highlights that agro-ecology is able to contribute to the dual objectives of economic and environmental development. However, challenges persist in terms of commercial incentives, inadequate extension services, and exclusion from mainstream policy. Iqbal et al. (2024) report that such problems are particularly severe in LMICs. Global frameworks should facilitate the collaboration of institutions and the development of equitable methods for financing that provide scope for local flexibility and expansion.

Integrated pest management is another important part of improving nature. IPM has already helped cut the use of chemical pesticides around the world by 40–60%, with no loss of yields and sometimes even a gain (Dara, 2019; Stenberg, 2017; Barzman et al., 2015). Biological control agents and ecological monitoring have led to fewer pest outbreaks in East Africa and Asia. This has led to more pollinators and a better ecology overall (Carvalho et al., 2024). Training and farmer field schools have been very important for LMIC adoption, but a lack of knowledge and resources is still a big problem. More education for farmers, better access to biological control inputs, and making IPM work with national food safety rules will all help more people use IPM and stick with it over time.

Combining trees and crops in agroforestry systems is one of the most effective ways to get nature-positive results. They can sequester between 1.5 and 3.5 tonnes of carbon per hectare per year all over the world. They can also make farms up to 80% more varied than monocultures (Nair et al., 2021; Fahad et al., 2022). Agroforestry makes the soil in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia 20–25% more fertile, maintains microclimates consistent, and stops water from draining off of fields. Tree crops provide you extra methods to produce money and make you less reliant on markets that aren’t always stable. But it’s challenging to make agroforestry bigger since land ownership is often not stable, payback times are long, and there is not much institutional funding. To solve these problems, they need to be included in national adaptation plans where land rights are robust and linked to carbon credit programs for farmers.

Climate-Smart Agriculture is now a major aspect of global development policy. It connects mitigation, adaptation, and productivity. Azadi et al. (2021) and Lipper et al. (2014) say that CSA measures including better water management, stress-tolerant crops, and conservation tillage can boost yields by 15–30% and cut emissions by up to 40%. Evidence supporting this has also been coming from Asia, Latin America, and Africa. There are many opportunities to use CSA in areas where the weather is quite variable and extreme heat and rain can seriously threaten food security. Taylor (2018) contends that in the absence of rules facilitating the accessibility of climate information to farmers, investment in digital agriculture will enable farmers to make decisions informed by real-time data. For the LMICs, blended finance strategies and regional knowledge-sharing platforms have been seen as two important means to make CSA bigger.

Food systems are stronger when there is more money spent on research and development, digital innovation, and infrastructure in rural places around the world (Hrytsaienko et al., 2019; Bathla, 2017). In contrast, less successful scenarios typically exhibit inadequate governance structures characterized by limited transparency and inconsistent policies (Hallam, 2011). From this viewpoint, forthcoming trajectories would be shaped by enhancements in governance via participatory policymaking, the establishment of accountability, and the integration of environmental indicators into agricultural investment strategies (Lencucha et al., 2020).

Evidence from around the world shows that nature-positive agriculture, including regenerative farming, agroecology, IPM, agroforestry, or CSA, can be productive, protect biodiversity, and make farms more resilient provided they are supported by strong laws, funding, and information systems. The main problems in LMICs are that people cannot get loans, institutions do not work together, and there aren’t enough long-term incentives. To achieve large-scale nature-positive changes worldwide, future strategies must include interconnected pathways that connect supporting funding, legislative frameworks, and farmer-led innovation.

4.1 Nature-positive food production implementation constrains

Regardless of the fact that this write-up demonstrates the socioeconomic and ecological importance of the nature-positive food production (NPFP), there are, however, several structural and systemic constraints which impede its larger-scale adoption in many low-income countries. One major challenge is the lack of resources for the startup investment in regenerative agriculture and transitions in agroecology. The majority of smallholder farmers work under limited resource environments. They have limited access to loans, crop insurance and the mechanisms of green financing (Iqbal et al., 2024; Petros et al., 2025). These problems in finance hinder farmers from using long gestation methods such as agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and soil management in regenerative agriculture. These methods involve initial investments before the accumulation of the benefits or profits (Ceddia et al., 2024).

Improper extension and technical support system has hindered the implementation of NPFP practices. A lot of underfunded agricultural extension exists in many LMICs which has resulted in inadequate training of farmers to implement the advance practices such as pest management (IPM), restoration of the fertility of soil, bio-stimulation of microbes or microorganisms and mixed cropping (Sher et al., 2024; Carvalho et al., 2024).

There is the pervasiveness in institutional and policy constraints. Political instability and division in governance throughout the environment, agriculture and climate sectors often cause poor coherence in policies, less incentives and unclear structures in subsidy that continue to support input systems of intensive production over the alternative in ecology (Demmler and Tutwiler, 2024; Petros et al., 2025).

The insecurity in the land tenure systems in a lot of South Asian and many African countries further hinders the long-term investment in restoration of soil, regeneration of landscapes and agroforestry (Ceddia et al., 2024).

The constraints in infrastructure and environmental factors also hinder the scaling. The stress in climates such as drought, improper rainfall patterns, and floods has caused the instability of restoration methods when not backed by irrigation, the systems of early warning (Sher et al., 2024).

The quality organic inputs, including biofertilizers, compost, cover crop seeds, and biological control agents, are not easily accessible. These materials reduce the implementation of nature-positive practices (Kaushal et al., 2023; de Andrade et al., 2023).

Together, these constraints create an implementation gap to exist between the world vision for nature-positive food production and indigenous realities, especially in the LMICs that are hit hard with environmental, financial and institutional challenges (Hodson de Jaramillo et al., 2023).

4.2 Future directions

To speed up the world transition toward the nature-positive food systems, the future actions must consider the financial, institutional and the hindrance to knowledge through the integrated policy, investments and research platforms. Increasing the potential of policy alignment throughout the agricultural, climate and biodiversity areas is very important. National plans for agriculture should incorporate regenerative agriculture, agroforestry, agroecology, agroforestry and integrated Pest Management as the main methods for the productivity and the resilience to climate. This is backed by the integrated regulation and the governance which cuts across all sector frameworks (DeClerck et al., 2023; Niggli et al., 2023).

Improvement in NPFP will need an increase in the financial capacity to reduce the risk of change for smallholder farmers. Merging the finance models, the schemes for green credit, carbon markets and the payment for the services in the ecosystems can produce the incentives needed in the economy to settle the restoration of the ecology, enhancement in the soil carbon and the improvement in the biodiversity (Hodson de Jaramillo et al., 2023; Brennan, 2024). Adding smallholder farmers in the investment programmes in climate-smart agriculture can improve the uptake of technology and also build resilience (Petros et al., 2025).

Improvement in the capacity of research and the systems of extension is another important priority. Decisions in the future should incorporate the participatory expansion of research platforms, farmer field schools and digital advisory tools to strengthen local adaptation of the practices of regenerative agriculture and agroecology (Sher et al., 2024; Wagh et al., 2024). Investment in soil and monitoring the systems of biodiversity will add up to the development of the standardized metrics for evaluating the results of NPFP, which still stands out as a current research gap (Rosier et al., 2025; Niggli et al., 2023).

Much attention on the innovation in climate-smart agriculture will be critical. There should be precision in the nature positive practice, such as irrigation, varieties in drought tolerance and microbial or biotechnological soil changes to improve resilience in climate and productivity (Kaushal et al., 2023; Carvalho et al., 2024). Digital technologies which is made up of geospatial mapping together with mobile based decision support, can support farmers to check their inputs and trends in ecology.

Finally, the framework of inclusive implementation must be the priority so as to empower women, local communities and smallholder farmers whose system of knowledge can significantly contribute to the transformational system in agroecology (Ceddia et al., 2024; Cabral et al., 2022).

5 Conclusion

The analysis further demonstrates that NPFP is not a singular approach but necessitates the integration of several ecological, technological, and governance techniques for its execution. A mix of regenerative agriculture, agroecology, agroforestry, Integrated Pest Management, and Climate-Smart Agriculture is good for the economy and the environment, as shown by examples from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. For instance, regenerative and agroecological systems have been shown to improve soil organic carbon by 15–30%, biodiversity by up to 50%, and yields by 10–25% (Ceddia et al., 2024; Vikas and Ranjan, 2024). Agroforestry and community-supported agriculture significantly contribute to carbon sequestration at rates of 1.5–3.5 t C ha−1 yr.−1 and facilitate emissions reduction by 20–40%, hence enhancing the resilience of farming systems to climate change (Sher et al., 2024; Rosier et al., 2025).

One thing we can take from the study is that nature-positive changes need more than just new technology; they also need places where people can implement that technology. Policies would have to be harmonized, equitable access to financial means assured, and all key stakeholders participating in knowledge systems for effective functioning (Cabral et al., 2022; Petros et al., 2025). Limited institutional capacity, unstable land tenure, and weak market incentives are the biggest concerns and are getting worse now. These issues are still very big difficulties in many countries with poor or middling incomes. So, these difficulties could be helped by more consistent policies across sectors and targeted investments in agroecological innovation and strengthening capacity. All future work must focus on integrated landscape methods that include regenerative techniques and are backed by strong governance and financial mechanisms. Climate change, biodiversity, and food security must all be goals that NPFP shares if it is to be successful over the world. An ecological transition can change agriculture from a source of destruction to a driver of ecological restoration and fair growth (Hodson de Jaramillo et al., 2023; DeClerck et al., 2023).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JA: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RA: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2025.1723693/full#supplementary-material

References

Acheampong, E. O. (2016). Impact of roads on farm size, market participation, and forest cover change in rural Ghana (MPhil thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia). ResearchOnline — James Cook University. doi: 10.25903/2vq1-8r58

Alavalapati, J. R., Shrestha, R. K., Stainback, G. A., and Matta, J. R. (2014). Agroforestry development: an environmental economic perspective. Agrofor. Syst. 61, 299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:AGFO.0000029006.64395.72

Ali, M. M., Bari, M. S., Hanif, M. A., Rahman, M. S., Ahmed, B., and Rahman, M. S. (2024). Nature-based solutions Charland resilience: agroforestry innovations as nature-based solutions for climate-vulnerable communities in Bangladesh. Nat. Based Solut. 6:100165. doi: 10.1016/j.nbsj.2024.100165

Altieri, M. A., Nicholls, C. I., Dinelli, G., and Negri, L. (2024). Towards an agroecological approach to crop health: reducing pest incidence through synergies between plant diversity and soil microbial ecology. NPJ Sustain. Agric. 2:6. doi: 10.1038/s44264-024-00016-2

Amankona, S., and Kabenomuhangi, R. (2024). Regenerative agriculture and soil health: enhancing biodiversity through sustainable farming practices. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 5, 3203–3215. doi: 10.55248/gengpi.5.0924.2678

Angon, P. B., Mondal, S., Jahan, I., Datto, M., Antu, U. B., and Ayshi, F. J. (2023). Review article integrated pest management (IPM) in agriculture and its role in maintaining ecological balance and biodiversity. Adv. Agric. 2023, 1–19. doi: 10.1155/2023/5546373

Azadi, H., Moghaddam Movahhed, S., Burkart, S., Mahmoudi, H., Van Passel, S., Kurban, A., et al. (2021). Rethinking resilient agriculture: From climate-smart agriculture to vulnerable-smart agriculture. J. Clean. Prod. 319:128602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128602

Barzman, M., Bàrberi, P., Birch, A. N. E., Boonekamp, P., Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, S., Graf, B., et al. (2015). Eight principles of integrated pest management. Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 35, 1199–1215. doi: 10.1007/s13593-015-0327-9

Bathla, S. (2017). “Public investment in agriculture and growth: an analysis of relationship in the Indian context” In eds. S. Dev and R. Swaminathan, Changing contours of Indian agriculture: Investment, income and non-farm employment (Singapore: Springer Singapore), 13–28. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4941-2_2

Brennan, C. S. (2024). Regenerative food innovation: the role of agro-food chain by-products and plant origin food to obtain high-value-added foods. Foods 13:427. doi: 10.3390/foods13030427,

Cabral, L., Rainey, E., and Glover, D. (2022). Agroecology, regenerative agriculture, and nature-based solutions: competing framings of food system sustainability in global policy and funding spaces. Drawdown 2022, 1–64. Available at: https://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/SmokeAndMirrors_BackgroundStudy.pdf

Carvalho, G. P., Costa-Camilo, E., and Duarte, I. (2024). Advancing health and sustainability: a holistic approach to food production and dietary habits. Foods 13:3829. doi: 10.3390/foods13233829,

Ceddia, M. G., Boillat, S., and Jacobi, J. (2024). Transforming food systems through agroecology: enhancing farmers' autonomy for a safe and just transition. Lancet 8, e958–e965. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00234-1,

Dara, S. K. (2019). The new integrated pest management paradigm for the modern age. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 10:12. doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmz010

de Andrade, L. A., Santos, C. H. B., Frezarin, E. T., Sales, L. R., and Rigobelo, E. C. (2023). Plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria for sustainable agricultural production. Microorganisms 11:1088. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11041088,

Deboe, G. (2020). Impacts of agricultural policies on productivity and sustainability performance in agriculture: a literature review. Paris: OECD. doi: 10.1787/6bc916e7-en

DeClerck, F. A. J., Koziell, I., Benton, T., Garibaldi, L. A., Kremen, C., Maron, M., et al. (2023). “A whole earth approach to nature-positive food: biodiversity and agriculture” in Science and innovations for food systems transformation. ed. J. von Braun (Cham: Springer), 469–496.

Demmler, K. M., and Tutwiler, M. A. (2024). Diet, nutrition, and climate: historical and contemporary connections. Front. Nutr. 11:1516968. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1516968,

Fahad, S., Chavan, S. B., Chichaghare, A. R., Uthappa, A. R., Kumar, M., Kakade, V., et al. (2022). Agroforestry systems for soil health improvement and maintenance. Sustainability 14:14877. doi: 10.3390/su142214877

FAO (2011). Climate-smart agriculture: Policies, practices and financing for food security, adaptation and mitigation. Rome, Italy: FAO.

FAO (2023). Agroforestry. Available online at: https://www.fao.org/agroforestry/en/ (Accessed November 28, 2025).

Farpón, Y. S.-, Mills, M., Souza, A., and Homewood, K. (2022). The role of agroforestry in restoring Brazil’s Atlantic Forest: opportunities and challenges for smallholder farmers. People Nat. 4 462–480. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10297

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2022). Key messages on climate-smart agriculture: how do we achieve it? What do we need? Available online at: https://www.fao.org/climate-smart-agriculture/en/ (Accessed November 28, 2025).

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. (2022). Climate-smart food Systems for Enhanced Nutrition Available online at: https://glopan.org/sites/default/files/pictures/GloPan%20Climate%20Summary%20Final.pdf (Accessed November 28, 2025).

Hallam, D. (2011). International investment in developing country agriculture—issues and challenges. Food Secur. 3, 91–98. doi: 10.1007/s12571-010-0104-1

Hodson de Jaramillo, E., Niggli, U., Kitajima, K., Lal, R., and Sadoff, C. (2023). Boost nature-positive production. In J. Braunvon (Eds.), Science and innovations for food systems transformation. (pp. 319–340). Cham: Springer.

Hrytsaienko, H., Hrytsaienko, I., Bondar, A., and Zhuravel, D. (2019). “Mechanism for the maintenance of Investment in Agriculture” in ed. V. Nadykto. Modern development paths of agricultural production: Trends and innovations (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 29–40.

Iqbal, B., Alabbosh, K. F., Jalal, A., Suboktagin, S., and Elboughdiri, N. (2024). Sustainable food systems transformation in the face of climate change: strategies, challenges, and policy implications. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 34, 871–883. doi: 10.1007/s10068-024-01712-y,

Kaushal, P., Ali, N., Saini, S., Pati, P. K., and Pati, A. M. (2023). Physiological and molecular insight of microbial biostimulants for sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 14:1041413. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1041413,

Lencucha, R., Pal, N. E., Appau, A., Thow, A. M., and Drope, J. (2020). Government policy and agricultural production: a scoping review to inform research and policy on healthy agricultural commodities. Glob. Health 16:11. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-0542-2,

Lipper, L., Thornton, P., Campbell, B. M., Baedeker, T., Braimoh, A., Bwalya, M., et al. (2014). Climate-smart agriculture for food security. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 1068–1072. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2437

Ministry of Food and Agriculture (2022). Integrated pest management plan (IPMP). Available online at: https://example.gov/ipmp2022 (Accessed November 28, 2025).

Mlengule, D. (2023). Experience of smallholder farmers on climate smart agriculture on soil fertility and moisture conservation in Ludewa District, Tanzania. FARA 7, 474–487. doi: 10.59101/frr072337

Nair, P. R., Kumar, B. M., and Nair, V. D. (2021). An introduction to agroforestry: four decades of scientific developments. Cham: Springer.

Niggli, U., Sonnevelt, M., and Kummer, S. (2023). “Pathways to advance agroecology for a successful transformation to sustainable food systems” in Science and innovations for food systems transformation. ed. J. von Braun (Cham: Springer), 341–359.

Petros, C., Feyissa, S., Sileshi, M., and Shepande, C. (2025). Factors influencing climate-smart agriculture practices adoption and crop productivity among smallholder farmers in Nyimba District Zambia F1000Research 13, 815. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.144332.3

Rahman, M. S., Wu, O. Y., Battaglia, K., Blackstone, N. T., Economos, C. D., and Mozaffarian, D. (2024). Integrating food is medicine and regenerative agriculture for planetary health. Front. Nutr. 11:1508530. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1508530,

Rosier, C. L., Knecht, A., Steinmetz, J. S., Weckle, A., Bloedorn, K., and Meyer, E. (2025). From soil to health: advancing regenerative agriculture for improved food quality and nutrition security. Front. Nutr. 12:1638507. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1638507,

Sher, A., Li, H., Hamid, Y., Nasir, B., and Zhang, J. (2024). Discover sustainability importance of regenerative agriculture: climate, soil health, biodiversity and its socioecological impact. Discover Sustain. 1:662. doi: 10.1007/s43621-024-00662-z

Sobola, O. O., and Amadi, D. (2017). The role of agroforestry in environmental sustainability. IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science. Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India: International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR). 8, 20–25. doi: 10.9790/2380-08512025

Stenberg, J. A. (2017). A conceptual framework for integrated pest management. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.06.010,

Tadesse, M., Simane, B., Abera, W., Tamene, L., Ambaw, G., Recha, J. W., et al. (2021). The effect of climate-smart agriculture on soil fertility, crop yield, and soil carbon in southern Ethiopia. Sustainability 13, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/su13084515

Taylor, M. (2018). Climate-smart agriculture: what is it good for? J. Peasant Stud. 45, 89–107. doi: 10.1080/03066150.2017.1312355

Vikas,, and Ranjan, R. (2024). Agroecological approaches to sustainable development. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:409. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1405409

Wagh, P., Chouhan, S., Tutlani, A., and Kumari, S. (2024) Agro-ecology: integrating ecology into agricultural systems. In Fields of Tomorrow: Advancements in Modern Agriculture. Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh. India: Astitva Prakashan. 1–20.

Zhou, W., Arcot, Y., Medina, R. F., Bernal, J., Cisneros-zevallos, L., and Akbulut, M. E. S. (2024). Integrated pest management: An update on the sustainability approach to crop protection. ACS Omega, Washington, DC, United States: American Chemical Society. 9, 41130–41147. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c06628

Keywords: regenerative agriculture, nature-positive food production, agroforestry, agroecology, integrated pest management, climate smart agriculture (CSA)

Citation: Amoah J, Ngmensoa G and Annan RA (2025) Global evidence on nature-positive agricultural practices and their socio-economic and ecological impacts: a systematic review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1723693. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1723693

Edited by:

Olutosin Ademola Otekunrin, University of Ibadan, NigeriaReviewed by:

Thiru Selvan, Tripura University, IndiaAndualem Muche Hiywotu, Debark University, Ethiopia

Ganeshkumar D. Rede, Symbiosis International University, India

Kiran Kotyal, Institute of Agri-Business Management, India

Copyright © 2025 Amoah, Ngmensoa and Annan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joseph Amoah, amFtb2FoOTlAZ21haWwuY29t

Joseph Amoah

Joseph Amoah Gregory Ngmensoa

Gregory Ngmensoa