- 1School of Management, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China

- 2Department of Economics, Business School, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Enhancing rural digital connectivity constitutes a significant strategy employed by China to refine rural economic development and mitigate urban–rural income inequality. Utilizing provincial data on urban–rural income inequality and rural digital connectivity spanning from 2012 to 2021, this paper adopts a rigorous two-way fixed effect model to explore the intricate mechanism through which rural digital connectivity narrows urban–rural income inequality. The findings indicate that the impact of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality follows a U-shaped curve. Furthermore, a comprehensive mechanism analysis reveals that rural digital connectivity narrows urban–rural income inequality by refining industrial structures, stimulating digital commerce, and fostering industrial convergence in rural areas. It is noteworthy that rural digital connectivity exerts varying degrees of influence across different regions, with a more profound impact observed in highly urbanized provinces offering free shipping services. Ultimately, this paper presents pertinent policy implications aimed at bolstering rural digital connectivity and mitigating potential negative spillover effects through the implementation of rational resource distribution.

1 Introduction

China, a typical agricultural nation, has experienced significant economic expansion following the implementation of the reform and opening-up policy (Xu et al., 2025b). However, this growth has also accentuated the pronounced rural–urban inequality inherent in its dualistic economic structure (Chan and Wei, 2021). According to China’s National Bureau of Statistics, while the Gini coefficient showed a slight decline from 0.474 in 2012 to 0.465 in 2019, it rose again to 0.468 in 2020, surpassing the international warning level of 0.4 and remaining significantly higher than in many OECD countries. This persistent inequality, largely driven by the widening urban–rural income ratio (Ma et al., 2018), poses a serious threat to China’s long-term sustainable development by increasing the risk of the country falling into the middle-income trap (Hu et al., 2023).

The rapidly expanding digital economy in China has emerged as a critical approach to addressing these disparities, with the potential to reduce the income gap between urban and rural areas and stimulate rural revitalization (Deng et al., 2024). It has emerged as a critical factor in advancing China’s high-quality development, presenting substantial opportunities for transforming rural areas by promoting new economic activities, improving market access, and enhancing overall quality of life (Wang et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024). Digital connectivity, which includes the ability to connect devices to the internet or mobile networks like 5G, as well as access to digital services, applications, and online platforms, plays a central role in this modern digital economy. Rural inhabitants perpetually face challenges in keeping pace with advancements in digital connectivity (Velaga et al., 2012), hindering their ability to actively participate in the digital economy. The Chinese government has implemented several national strategies, such as “Internet Plus,” “Broadband Rural,” and “Digital Village,” aimed at closing the connectivity gap and expanding rural digital inclusion. Recent evidence further links digital capability and rural digitalization to shared prosperity outcomes: household-level digital capability and financial literacy are positively associated with common prosperity (Lyu et al., 2025). The digital economy significantly promotes farmers shared prosperity, with high-quality agricultural development acting as a key channel and reveal spatial spillovers across regions (Lu et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2025). Against this backdrop, understanding how rural digital connectivity shapes urban–rural income inequality is essential for leveraging connectivity to reduce disparities and promote harmonious development.

Extant evidence links digitalization to both equalizing and disequalizing distributional outcomes, with effects that hinge on what is measured, where it is measured, the stage of digital development, and local endowments. At the county and household level, studies using ICT diffusion measures often find gap-narrowing effects (Dong et al., 2024). By contrast, at the inter-city scale, broadband roll-out yields heterogeneous distributional impacts that depend on city size, agglomeration, and human-capital composition, underscoring skill-biased channels whereby connectivity may either mitigate or exacerbate dispersion (Qiu et al., 2021b). At the provincial level, results vary with how digitalization is operationalized. Broader digital-economy composite indices tend to reveal impact heterogeneity with widening in some regions and narrowing in others consistent with a digital divide or digital dividend pattern (Xia et al., 2024). Nonlinear stage-dependence is also salient. Using panel data for 30 provinces from 2009 to 2019, (Jiang et al., 2022) document a U-shaped relationship between digital-economy development and the urban–rural income gap, together with spatial spillovers and evidence from the “Broadband Rural” policy shock. However, Wang and Liu (2025) find that the digital economy initially widens the gap but that this widening diminishes as digitalization progresses, with the sign and magnitude conditioned by regional endowments Complementing these province-level patterns, Qiu et al. (2021a) provide evidence consistent with a Technological Kuznets Curve (TKC) mechanism, in which internet penetration first exacerbates and later reduces the gap in specific macro-regions like north and east China, while reverse causality from inequality to internet diffusion is limited given the policy-driven rollout. Finally, recent provincial analyses based on internet-development indicators further corroborate that empirical signs flip with measurement choices, spatial scale, nonlinear stages, and regional heterogeneity (Wang et al., 2021).

The evaluation of digital connectivity has evolved from a reliance on a single indicator to a more comprehensive assessment that incorporates a variety of indicators. However, a comprehensive methodology for accurately evaluating digital connectivity in rural areas is still conspicuously absent. Previous methodologies have focused exclusively on urban indicators and relied on a narrow set of measures, including internet and mobile phone penetration, digital financial inclusion, and fundamental infrastructure metrics (Deng et al., 2024; Peng and Dan, 2023; Yi et al., 2024; Lynn et al., 2022). These methods frequently depended on static and generalized measures that were unable to capture the dynamic nature of digital infrastructure development and usage patterns, particularly in rapidly evolving rural contexts. Additionally, they tended to employ uniform indicators in both urban and rural areas, overlooking rural-specific conditions. Remoteness is a critical factor in digital exclusion, as Park (2017) emphasized; however, it has been largely disregarded in conventional digital connectivity metrics. This oversight reveals significant deficiencies in current frameworks, which fail to address challenges endemic to rural settings, such as low mobility, poor transportation infrastructure, and limited investment opportunities, leaving a significant gap in our understanding and measurement of rural digital connectivity.

Existing literatures have laid a solid foundation for exploring the relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality. However, these studies predominantly analyze the impact across entire regions, failing to specifically focus on rural areas. Consequently, there remains a notable gap in understanding how rural digital connectivity influences urban–rural income inequality through indirect relationships and spatial interactions. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying these nonlinear dynamics require deeper exploration. The rapid development of the internet in the past year has facilitated the integration of provinces into a unified entity, strengthening spatial relationships between provinces. Hence, rural digital connectivity’s impact is likely to have significant non-linear spatial spillover effects, which have been largely overlooked in most literatures.

The potential contributions of the study are as follows: Firstly, we developed a remoteness-embedded China’s rural digital Connectivity Index for 30 provinces between 2012 and 2021, integrating rural-specific investment and infrastructure, service penetration and usage, and last-mile logistics. This method addresses the gap in current research, which frequently fails to consider dynamic development and the distinctive obstacles that rural areas encounter in digital engagement when assessing digital connectivity. Subsequently, we verify the U-shaped correlation between urban–rural income inequality and rural digital connectivity. We further examined this relationship by investigating spatial heterogeneity, with a prearticular emphasis on the varying effects of free shipping and urbanization levels across provinces. Furthermore, the nonlinear spillover effects of digital connectivity at the provincial level are investigated using a Spatial Durbin Model (SDM). Additionally, we systematically examine the indirect pathways through which rural digital connectivity influences urban–rural income inequality, focusing on two key mechanisms. First, we explore how rural digital connectivity promotes industrial structure, particularly by stimulating digital commerce. Second, we investigate how rural digital connectivity fosters industrial convergence in rural areas, thereby helping to reduce urban–rural income inequality.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured in the following manner: Section 2 explores the theoretical analysis and presents the research hypotheses. Section 3 provides an explanation of the data and methodologies used. Section 4 provides the empirical findings obtained from the baseline regressions, as well as performs robustness checks and heterogeneity analyses. Section 5 delves deeper into spatial spillover effects and examining intermediary mechanisms. Section 6 serves as a final summary, outlining the conclusions and their implications for policy.

2 Theoretical analysis and hypothesis

2.1 Direct effect of the rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality

During the early phases, advancements in rural digital connectivity can greatly enhance economic opportunities in rural areas by boosting business efficiency, developing the skills and knowledge of the local population, and increasing their digital engagement (Prieger, 2013). This increased connectivity enabling rural residents to access information, markets, and services more effectively, fostering digital literacy, innovation, and diversified income sources, ultimately narrow the urban–rural inequality and improved living standards (Townsend et al., 2013). However, as connectivity matures, disparities in access to advanced digital infrastructure, economic polarization, and a growing skill mismatch begin to emerge (Song et al., 2020). Urban areas, with their superior resources, attract more sophisticated digital services, while rural areas lag, limiting their ability to benefit from the latest digital advancements. Additionally, as the digital economy evolves, those with better initial access to resources and education within rural areas capitalize more effectively on these opportunities, widening the income gap. The lag in targeted policies and the focus on urban-centric development exacerbate these disparities, leading to a widening divide as rural areas struggle to keep pace with technological advancements. Our first hypothesis is:

H1: The impact of rural digital connectivity on urban-rural income inequality has a U-shaped curve

2.2 Spatial spillover effect rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality

The development of rural digital connectivity generates spatial spillover effects that influence urban–rural income inequality through a dynamic redistribution of economic opportunities and resources among rural regions (Xu and Tao, 2024). During the initial stages of rural digital connectivity development, well-connected rural areas tend to drain economic opportunities, resources, and investments from less developed neighboring rural areas. This siphoning effect widens the digital divide and exacerbates urban–rural income inequality, as the lagging rural areas struggle to reap the benefits of digitalization. However, as the more advanced rural regions reach a saturation point, the marginal returns on additional digital investment decline. Capital technology and economic opportunities begin to diffuse toward neighboring, less-developed rural areas. This transition creates a trickle-down effect that gradually reduces the urban–rural income inequality across regions by fostering economic growth, job creation, and improved digital infrastructure. Our second hypothesis is:

H2: Rural digital connectivity has an inverted U-shaped impact on urban–rural income inequality in neighboring provinces through spatial spillover effects.

2.3 Indirect effect of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality

In this paper, we embark on a channel analysis of how digital connectivity in rural areas serves as a potent catalyst for shortening the income inequality between urban and rural areas. As Figure 1 properly illustrates, we examine the pathway of industrial upgrading as a key factor in narrowing the urban–rural income gap. Furthermore, we delve into the intricate mechanisms that underlie the motivation of industrial upgrading, particularly regarding the emerging digital commerce in rural areas, fueled by widespread digital technology adoption. Additionally, we will explain that industrial convergence is another important channel for narrowing urban–rural income inequality. This nuanced examination provides a deeper insight of the effectiveness of rural digital connectivity and its implications for sustainable economic development by alleviating income inequality.

2.3.1 Industrial structure optimization

Urban–rural income inequality primarily stems from imbalanced income distribution. In China, over half of the rural population relies on primary industries such as agriculture, fisheries, and animal husbandry, while most urban residents are engaged in secondary and tertiary industries. The income distribution is skewed toward these higher-paying sectors, with average incomes in secondary and tertiary industries significantly outpacing those in primary industries. Prior to the advent of rural digitization, industrial structure optimization was primarily observed in urban areas, as the scarcity of high-tech companies in rural regions left little incentive for such optimization. This urban-centric optimization exacerbated income and property inequality, widening the wage gap—a phenomenon known as the “inequality cost” of industrial upgrading in China (Chen and Ma, 2022). However, the enhancement of rural digital connectivity has spurred the evolution of the industrial structure in rural area. Hong and Zhang (2021) explored the impact of industrial upgrading on urban–rural income inequality. The findings suggested that the evolution of industrial structure could contribute to changes in income distribution, potentially influencing the urban–rural income inequality. Therefore, industrial structure optimization plays a significant role in narrowing the urban–rural income gap, highlighting the importance of considering industrial upgrading as a remarkable channel for income inequality alleviation. Digital connectivity in rural areas is crucial in facilitating industrial structure optimization by refining efficiency and innovation. As digital connectivity expanded, it provides companies across various industries with new opportunities to upgrade their operations, adopt new technologies and improve productivity (Fan, 2022). Besides, according to Li (2021), despite the interconnected technologies altering the traditional economic models, the effect of digital connectivity also stemmed from the profound influence of internet-industry integration on industry structure. Moreover, the development of digital connectivity per se encouraged independent innovation in digital technology and improved the institutional environment for the digital economy to promote industrial upgrading (Li et al., 2024). This paper employed the mediate effect model to examine whether rural digital connectivity narrowed the urban–rural income inequality by promoting industrial upgrading. To quantify industrial upgrading, three distinct methodologies will be employed. The required data sets in this section were collected from China Statistical Yearbook.

The first indicator is the industrial structure rationalization: This indicator reflects the aggregate quality and coordination between industries. It provides insights into the efficiency of resource utilization and the extent of inter-industry coordination, serving as a gauge of the coupling between input and output structures. This measurement, adopted from Xiong et al. (2023), is expressed by the Equation 1:

where represents output, donates employment, and indicates different provinces. R = 0 indicates that the economy is in equilibrium. When R is not equal to 0, the larger R, the greater the deviations from the equilibrium, leading to less efficiency and unreasonable employment structure.

The second indicator is the overall upgrading of industrial structure: Production processes in secondary and tertiary industries are typically more efficient and environmentally friendly. With the widespread adoption of new digital technologies, there is a noticeable increase in the proportion of secondary and tertiary industries, which elevates industrial structures from lower to higher levels. Alcorta et al. (2013) demonstrated that the transition from primary to secondary and tertiary sectors is integral to achieving sustainable economic growth. Following the methodology of Wu et al. (2021), we define the overall upgrading index of the industrial structure based on Petty-Clark’s Law, calculated as Equation 2:

Among them, represents the overall upgrading index of industrial structure, represents the proportion of the output of the i-th industry.

The third indicator is the industrial structure advanced index: Since 1970, the advent of the information revolution has significantly influenced the industrial structure of industrialized nations. A noticeable progression towards the tertiary sector within the industrial structure has emerged. This transition has been further propelled by the digitalization. This indicator can stand out as a pivotal aspect in the enhancement of the industrial structure (Gan et al., 2011). Drawing on the method of Gan et al. (2011), the industrial structure advanced index is defined as Equation 3:

Among them, represents the industrial structure upgrading index, represents the increase in the output of i-th industry.

Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis.

H3: Industrial structure optimization plays a significant mediating role in the nexus between rural digital connectivity and urban-rural income inequality.

2.3.2 Digital commerce and industrial structure optimization

Behind the optimization of industrial structure in rural areas lies a transformative mechanism driven by rural digital connectivity. Rural digital connectivity boosts digital infrastructure, enhances internet connections, and expands connectivity-derived services, which collectively propel digital commerce in rural regions. This enhanced connectivity facilitates a seamless flow of information, logistics, and financial transactions (Kimura and Chen, 2017), ensuring the sustainable development of digital commerce. Chen and Ruddy (2020) also proposed that enhancing digital connectivity should be a policy priority to support digital commerce. With the advancement of digital technologies, the burgeoning digital commerce heralded new opportunities in China. In the past decade, the emergence of Taobao village in rural China was a typical example of the promotion of rural digital commerce where pioneer entrepreneurs brought digital commerce to the village with well-established digital connectivity, achieving success in this business. Social networking further played a mediating role in diffusion and attracted more investment in rural digital commerce (Zang et al., 2023). The emergence of digital commerce in rural areas profoundly influenced the structures of rural industries through household consumption structures and innovation. For instance, digital commerce in rural areas increased the disposable income of rural households, thus promoting their consumption structure (Zhou, 2024). The upgrading of households’ consumption structure led to the overall development and transformation of industries. Zhang et al. (2019) explored the relationship between household consumption and industrial structure upgrading. His findings indicated that household consumption played a crucial role in promoting industrial structure upgrading through growth in the consumption of new products in the private sector. Besides, digital commerce stimulates competition in markets, encouraging firms to optimize innovation factors. Specifically, the digital economy could enhance industrial structure upgrading by facilitating innovation factor allocation, leading to advancements in industrial structure servitization, upgradation, and interaction levels within the industrial sector (Chang et al., 2024). Chu (2024) also noted that digital commerce, a pivotal component of the digital economy, could contribute to enhancing and advancing industrial structure by enhancing regional innovation. Hence, this paper investigated the relationship between digital connectivity and industrial structure through digital commerce. To start, we developed an evaluation index system for rural digital commerce (Table 1) and measure its development level using the entropy method. The detailed measurement steps are provided in Appendix 1. Our fourth hypothesis is therefore:

H4: Rural digital connectivity can promote industrial structure optimization by enhancing digital commerce.

2.3.3 Rural industrial convergence

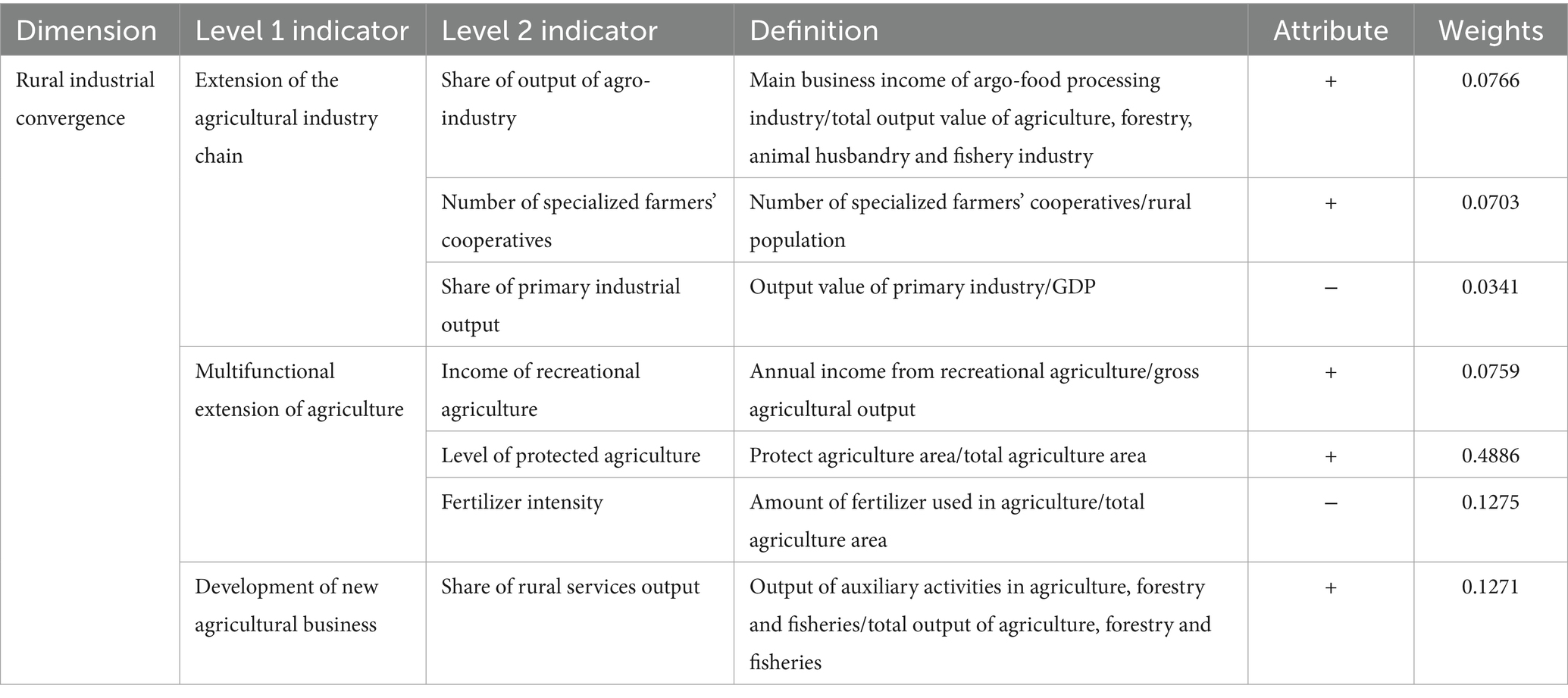

Since 2015, the Chinese government has focused on revitalizing rural industries, according to the China Agricultural Sector Development Report. This initiative has aimed to modernize agriculture and integrate primary, secondary, and tertiary industries within rural areas. Such thriving businesses are intended to boost farmer incomes, eradicate poverty, and foster rural prosperity. Concurrently, the authorities have implemented a pilot project to enhance the use of digital technologies in rural areas. This pilot project encompasses the overall planning and design of “digital villages,” improvement of new generation information infrastructure in participating villages, and exploration of new models for rural digital economy and rural governance. These policies enhanced rural digital connectivity, which in turn fostered industrial convergence in rural areas. Digital connectivity is catalyzing the convergence of industries by spawning new business opportunities and models (Guo et al., 2023). The integration of communication networks leads to increased productivity, reduced transaction costs, and foster connection between industries. Specifically, digital technologies are transforming traditional industries and catalyzing the emergence of new sectors. This evolution is not just facilitating industrial upgrading but is also enabling the integration of diverse industries, demonstrating the profound impact of digital technologies in reshaping the industrial landscape (Zhou et al., 2022). Furthermore, rural industrial convergence has extended the industrial chains and create more job opportunities in rural areas, rising the average income in rural areas and narrowing the urban–rural income inequality. Devasmita (2018) observed similar trends in income convergence within the EU and ASEAN from 2000 to 2014, noting that industrial convergence significantly reduces income inequality and promotes overall economic convergence. Building on the aforementioned analysis, this paper explored whether rural digital connectivity could narrow urban–rural income inequality through promoting industrial convergence. We draw on the method of Chen et al. (2021) and Wang et al. (2024), using the entropy methodology to measure the rural industrial convergence in the context of Table 2. Therefore, our final hypothesis is proposed as follows.

H5: Industrial convergence has a remarkably mediating effect on the non-linear impact of rural digital connectivity on urban-rural income inequality.

The analysis framework by which the rural digital connectivity affects urban–rural income inequality can be illustrate in Figure 1.

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Model specification

3.1.1 Panel models

To analyze the nonlinear causal relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality, we included both the core explanatory variable digital connectivity and its squared term in a two-way fixed effects model. The model is defined as Equation 4:

Where, the dependent variable, , represents urban–rural income inequality, while the explanatory variable, ,indicates the level of rural digital connectivity. The Vector represents the control variable; Subscripts and correspond to province and year, respectively. The model addresses bias arising from unobservable provincial heterogeneity by incorporating province-fixed effects and accounts for time-specific trends through the inclusion of time-fixed effects . The constant term is denoted by , and represents the random error term.

3.1.2 Spatial econometric model

Based on the theoretical analysis below, we utilized the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM) to estimate the spatial spillover effect of rural digital connectivity. The general form of the spatial econometric model is expressed as Equations 5–6:

Where and are the spatial autoregressive and spatial autocorrelation coefficients, respectively; represents the spatial weight matrix; and denote the regional and time effects, respectively; and is the error term. We select the geographic distance spatial weight matrix, which is established in Equation 7:

Where denotes the distance between the province and which are derived form their respective longitude and latitude coordinates.

3.2 Variable description

3.2.1 Explanatory variable

This study developed a comprehensive index that assesses rural digital connectivity (dig) using the entropy method. It is based on 11 secondary indicators (refer to Table 3), which are organized into three pillars and calculated using the entropy method. Digital Infrastructure and Investment capture the system’s capacity and commitment including optical-fiber cable length, mobile-phone coverage, rural network investment, and fixed investment in the social digital industry. Digital Services Penetration and Usage measures demand-side activation including internet penetration, the scale of rural network payments, and the share of rural household expenditure on transport and communications, which we treat as a positive remoteness-sensitive engagement indicator: in geographically remote settings, effective participation in the digital economy requires more distance-bridging activities, so a larger budget share signals stronger activation of the connectivity channel rather than mere price burden. Logistics and Communication Services addresses the last-mile feasibility of digital activity including rural postal and communication service levels, delivery routes, and the proportion of administrative villages with postal services capturing whether online transactions can be completed where mobility is low and transport infrastructure is thin. By combining usage-based activation with last-mile serviceability, the index embeds the remoteness dimension highlighted by Park (2017), which conventional connectivity metrics largely overlook. It therefore provides a geography-sensitive measure of rural regions’ capacity to participate in and benefit from the digital economy. The data for these indicators were derived from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Rural Statistical Yearbook, and Peking University’s Index of Digital Financial Inclusion.

3.2.2 Explained variable

The Theil index is employed to quantify the urban–rural income inequality across China’s 30 provinces from 2012 to 2021. Theil index is highly responsive to income fluctuations in high and low-income brackets, making it ideal for capturing the fundamental features of income inequalities in China, which are most evident at the upper and lower ends of the income distribution. The formula is defined as Equation 8:

Where and represent the total income of urban and rural residents, respectively, during period (calculated as the total population multiplied by the average per capita income). represents the total income for period , and represent the urban and rural populations during period and represents the total population during period . The Theil index accounts not only for absolute changes in urban and rural incomes but also incorporates changes in urban and rural population structures. A higher Theil index indicates a greater urban–rural income inequality. Data are drawn from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook and local statistical bureaus; missing values are imputed via within-province linear interpolation over time, and continuous variables are winsorized within year at the 1st and 99th percentiles across provinces.

3.2.3 Control variables

Drawing on existing research, other factors also influence urban–rural income inequality (Chen, 2016; Tang and Sun, 2022; Kakwani et al., 2022). Our study controlled the degree of openness , measured by the proportion of the total import and export value of foreign investment to the regional GDP for each province; the strength of fiscal support for agriculture , measured by the ratio of local government expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs to the general budget expenditure of local finances; the agricultural industrial structure , measured by the proportion of the total agricultural output value to the total output value of agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, and fishery; and the level of economic development , measured by the logarithm of the regional GDP for each province. Data for these variables were obtained from the China Statistical Yearbook and the provincial statistical yearbook with missing values is filled via within-province linear interpolation over time.

Descriptive statistics for the variables are presented in Table 4.

4 Results and discussions

4.1 Baseline estimation results

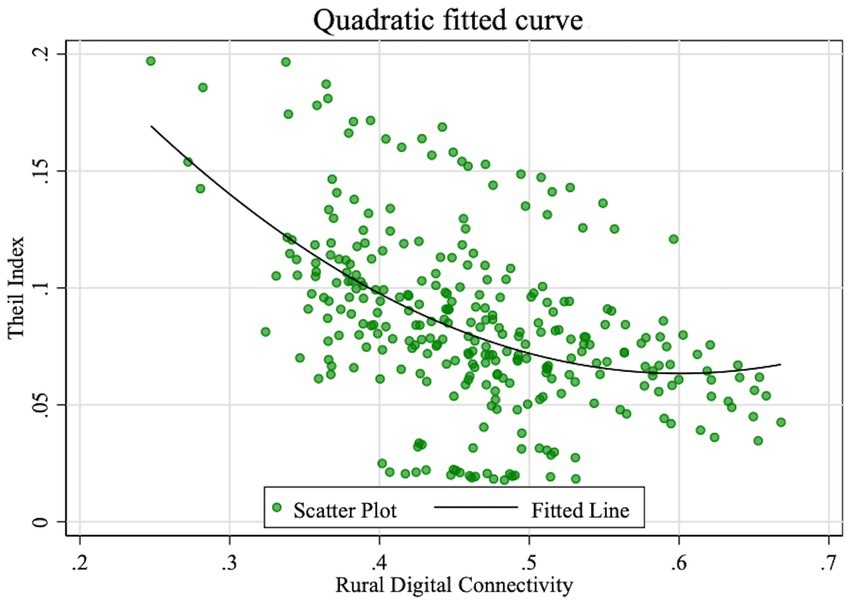

The U-shaped relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality is initially depicted through a scatter fit curve in Figure 2. Most provinces are positioned to the left of the turning point, offering preliminary evidence in support of Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2. Quadratic fitted curve between the rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality.

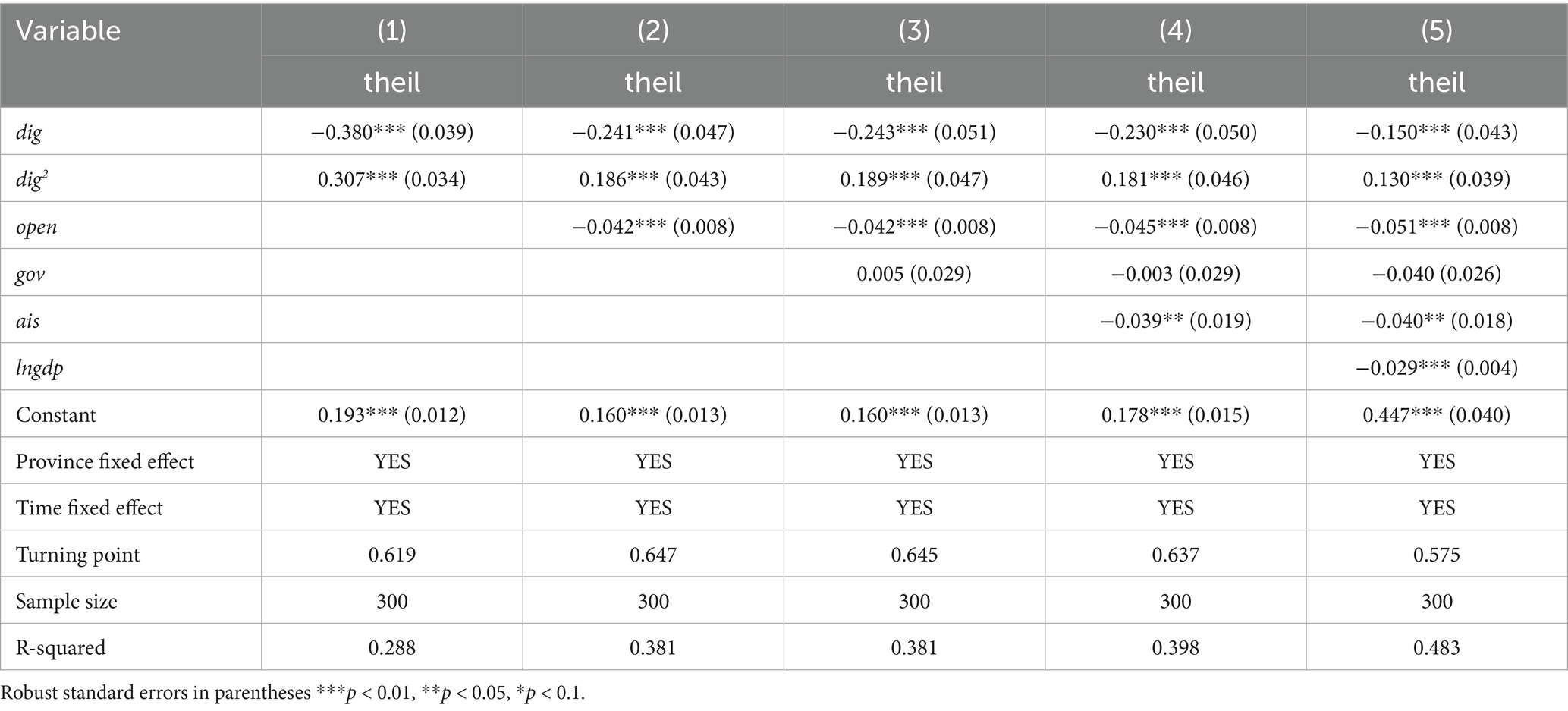

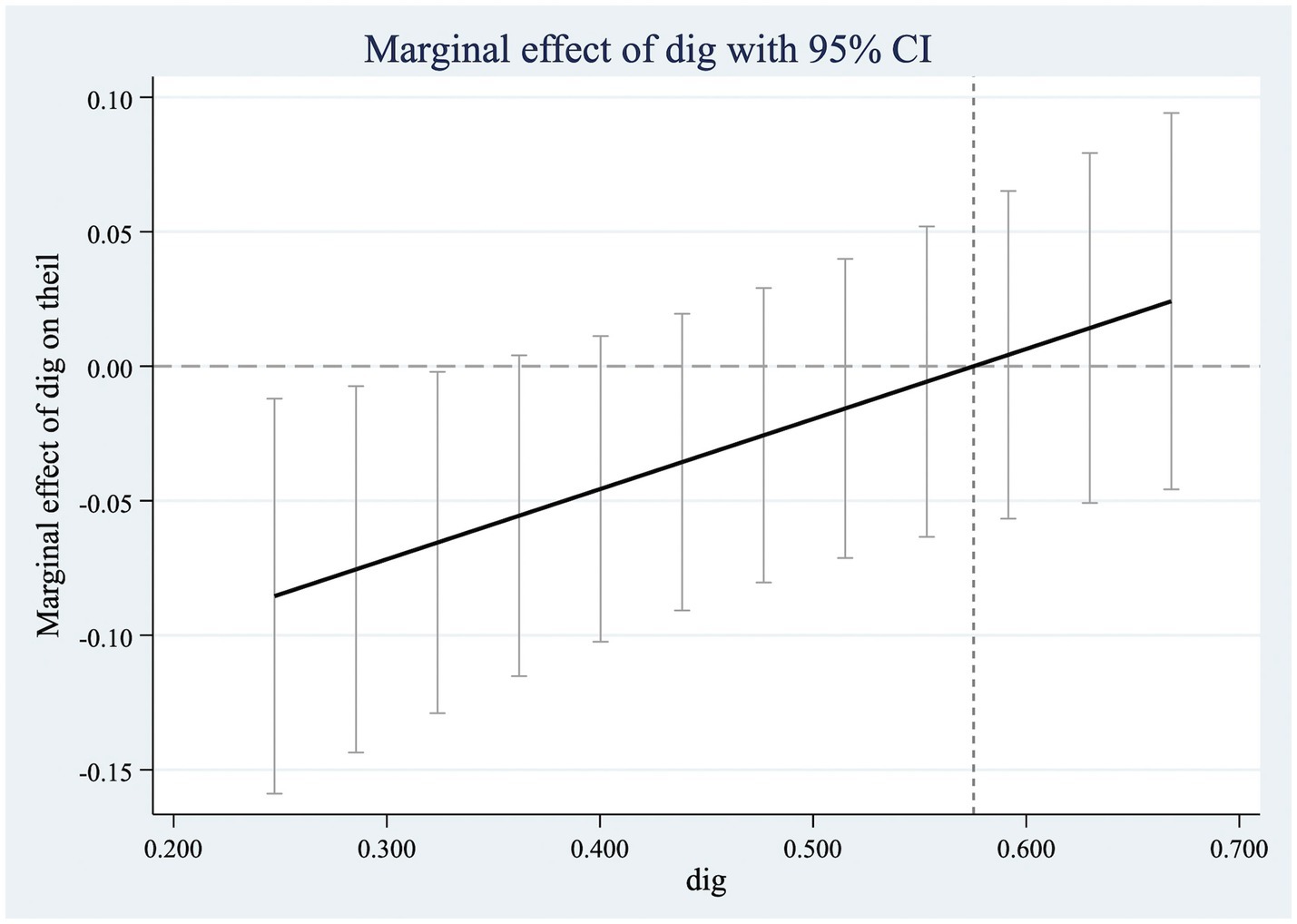

Using the two-way fixed effects (FE) panel regression model, confirmed as the more suitable option by the Hausman test, the analysis of full sample data from 30 Chinese provinces reveals a U-shaped relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality. Table 5 demonstrates this relationship, showing that as control variables are sequentially introduced from column (1) to (5), the coefficient for digital connectivity is consistently negative and its quadratic term positive, with both coefficients significant at the 1% level across all models. We performed a U-test following the methodology proposed by Lind and Mehlum (2010) to validate the existence of a U-shaped relationship. With all controls, the marginal effect of rural digital connectivity on the Theil index equals . At low connectivity the effect is negative because connectivity lowers search, transaction, and last-mile frictions, thereby narrowing the gap. As rises the magnitude of this reduction diminishes, the effect crosses zero at the turning point 0.57, and becomes positive thereafter, implying a subsequent widening of the gap as skill-biased gains that accrue disproportionately to more developed regions. Figure 3 trace the pattern of the marginal effect of the rural digital connectivity at 95% confidence intervals which further verify the Hypothesis 1. As of 2021, in most provinces, rural digital connectivity has not surpassed the turning point, indicating that increased digital connectivity in rural areas is currently narrowing urban–rural income inequality.

4.2 Robustness check

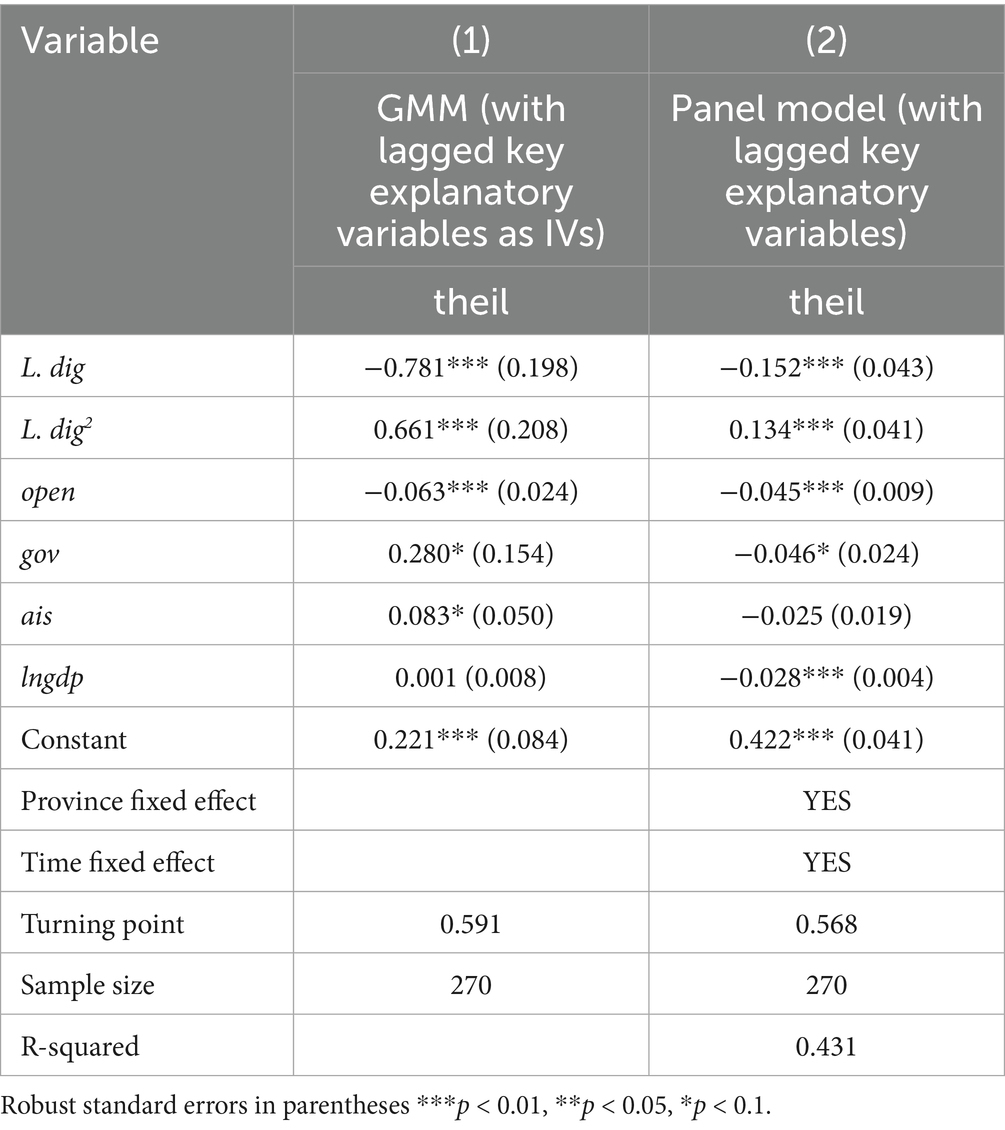

We utilized an iterative Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) approach, using one lagged key explanatory variables as instruments to address potential endogeneity. This method was chosen recognizing that the effects of increased rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality are not immediate. To ensure the reliability of our model, we conducted the AR (2) test for second-order serial correlation and the Sargan test for over-identifying restrictions, both of which returned p-values above 0.1. These results indicate an absence of second-order serial correlation and validate both the model and the instruments used. For additional robustness, we also utilized panel models with lagged explanatory variables. The findings, displayed in Table 6, show that the coefficient of rural digital connectivity is negative and its squared term is positive, with both significant at the 1% level. These results confirm the robust U-shaped relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality.

4.3 Heterogeneity analysis

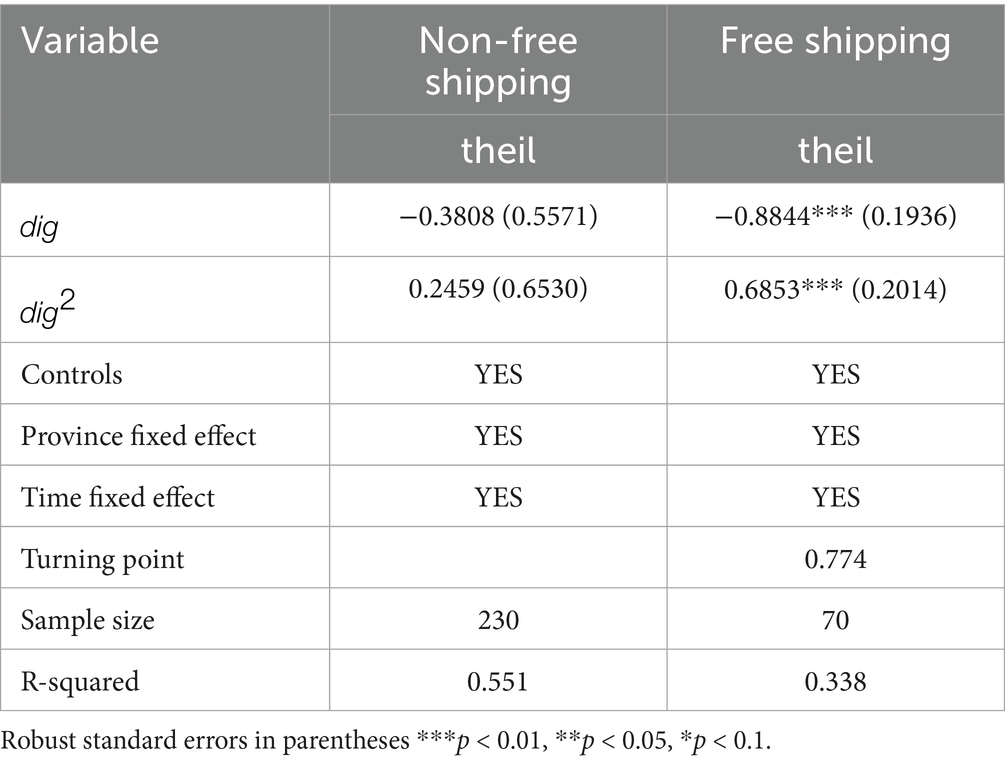

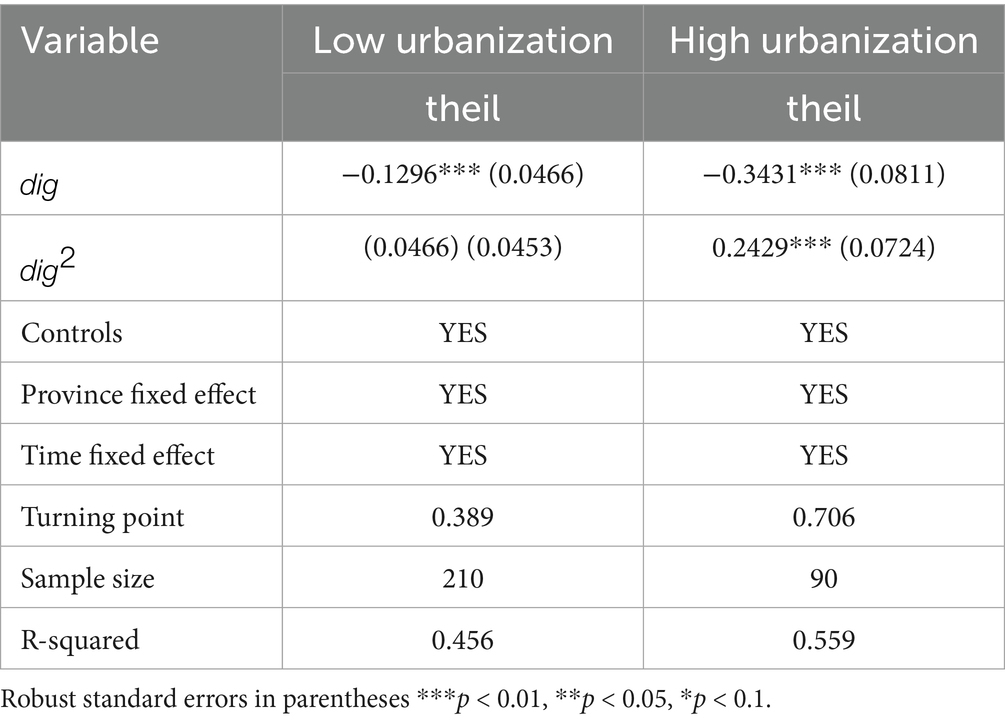

The impact of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality varies significantly across different regions. As discussed in sections 2.3.1 and 2.3.2, rural digital connectivity can greatly help digital commerce enjoy prosperity, leading to an improved rural industrial structure. This, in turn, plays a critical role in reducing urban–rural income inequality. However, in some remote areas where transportation infrastructure is underdeveloped, these regions are often excluded from free shipping zones. Research by Humairoh and Annas (2023) highlights the importance of free shipping in boosting customer satisfaction and overall e-commerce success. Similarly, Guo et al. (2020) used a dynamic game model found that that optimizing free shipping strategies can better meet consumer expectations and improve e-commerce performance. Consequently, in regions outside free shipping zones, the benefits of digital connectivity on digital commerce may be limited.

Urbanization is another key regional factor influencing the relationship between digital connectivity and income inequality. He (2023) examined the correlation between urbanization and income inequality, finding that urbanization in China has not reduced income inequality as expected. Instead, it has often exacerbated disparities, particularly affecting lower-income groups. This is partly due to the uneven distribution in highly urbanized areas, which creates a scarcity of resources in rural regions. In these situations, rural areas are often required to allocate their limited resources to support urban centers. Despite these challenges, the development of digital connectivity has brought about increased job opportunities, attracted talent to rural areas, and enhanced human capital, contributing to rural revitalization efforts (Dai and Zeng, 2022). The effect of these developments may be more pronounced in highly urbanized regions, where resource distribution is more skewed. This paper further explores the heterogeneous impact of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality, focusing on two factors: the availability of free shipping and the level of urbanization. The non-free-shipping areas1 are selected according to the shipping policies of most internet shops.

4.3.1 Free shipping

Table 7 presents the heterogeneous effects of digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality based on the availability of free shipping. In non-free-shipping areas, the coefficients of digital connectivity and its squared term are both insignificant, indicating that digital connectivity does not significantly influence urban–rural income inequality in these regions. Per-order delivery fees create a last mile cost wedge that raises effective consumer prices and compresses seller margins, reducing order frequency and thinning markets. Under these frictions, better digital connectivity fails to convert into actual transactions, leaving its inequality-reducing effect indistinguishable from zero. Conversely, in areas where free shipping is available, the coefficients for and are both significant. Because platforms or logistics networks internalize last mile costs, participation expands on both the demand and supply sides and the inequality effect of connectivity re-emerge with the same sign pattern as in the benchmark U-shape. This confirms that digital connectivity effectively impacts urban–rural income inequality only in regions where free shipping is accessible.

4.3.2 Urbanization

Table 8 presents the estimation results concerning urbanization. Urbanization is measured as the ratio of urban to rural population and classify provinces within each year into high- and low-urbanization groups using the cross-province median. The coefficients for digital connectivity are significantly negative in both low and highly urbanized areas, indicating that digital connectivity contributes to reducing urban–rural income inequality across all regions. However, this effect is more pronounced in highly urbanized areas. Additionally, the turning point in highly urbanized areas is 0.706, which is considerably higher than in less urbanized regions, suggesting that the impact of digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality is stronger in highly urbanized areas.

5 Further analysis

5.1 Spillover effect analysis

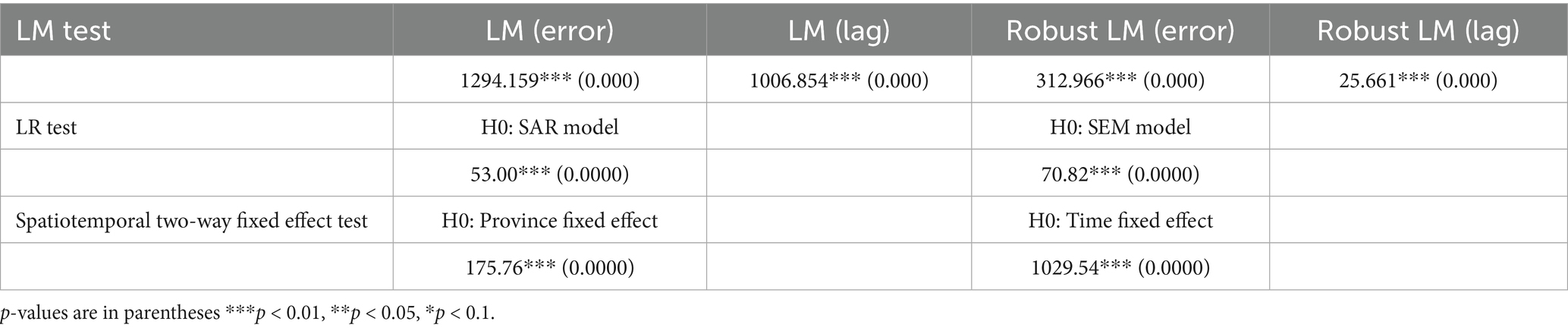

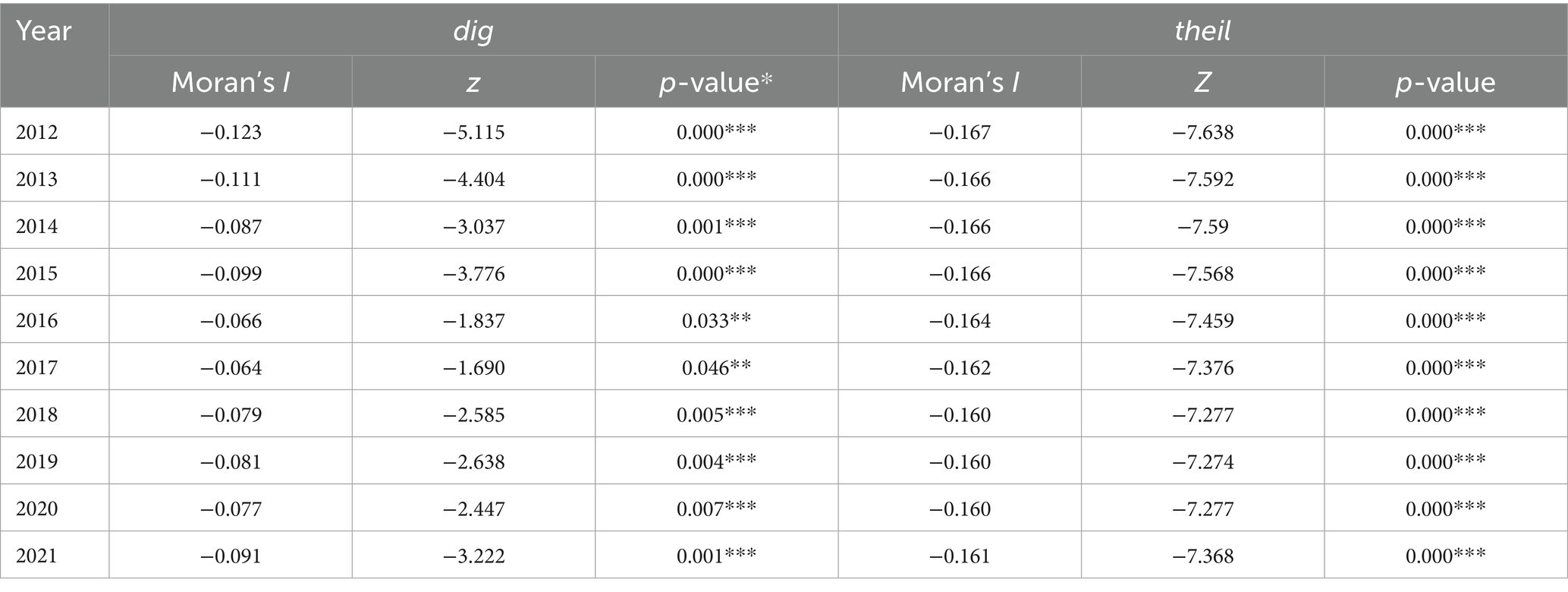

The spatial autocorrelation test was performed prior to the analysis of spillover effects. The global Moran’s I index is employed to estimate the spatial autocorrelation of rural digital connectivity and the urban–rural income inequality in China, as illustrated in Table 9, based on the geographic weight matrix. The Moran’s I index consistently exhibits significant negative values from 2012 to 2021, indicating a clear negative spatial correlation in the rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality of 30 provinces in China. The negative Moran’s I value indicates an uneven distribution of digital connectivity, supporting our previous theoretical analysis of the siphoning effect, where leading rural areas attract resources and opportunities, leaving neighboring rural regions with lower digital connectivity.

Table 9. Spatial autocorrelation test result of rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality.

Table 10 presents the result of the Multiplier (LM) test Likelihood Ratio (LR) test and fixed effect test results. According to Elhorst (2014) SDM model with spatiotemporal double fixed effect is the optimal choice.

Table 11, column (1), presents the SDM estimation, where the coefficients of W*dig and W*dig2 are significant, indicating a strong spatial spillover effect. Columns (2) to (4) provide the decomposition results of the total spatial effects. Concerning the direct effects of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality, the primary coefficient of rural digital connectivity was negative and the squared term was positive. There was a “U-shaped” relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality, which again verified Hypothesis 1. Regarding the spatial spillover effects of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality, the coefficient of rural digital connectivity was positive and its squared term was negative, suggesting an “inverted U-shaped” relationship between rural digital connectivity and urban–rural income inequality, thus confirming Hypothesis 2.

5.2 Mediating effects

In this section, we provide empirical evidence to examine the mechanisms through which rural digital connectivity can reduce urban–rural income disparities. Hypothesis 3, 4 and 5 are tested in the following stages. First, we employ a two-step channel methodology to analyse the channel of industrial structure optimization. Second, digital commerce is examined to be an important mediating factor between digital connectivity and industrial structure. Finally, we reveal that rural industrial convergence has a remarkably mediating effect on the impact of digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality.

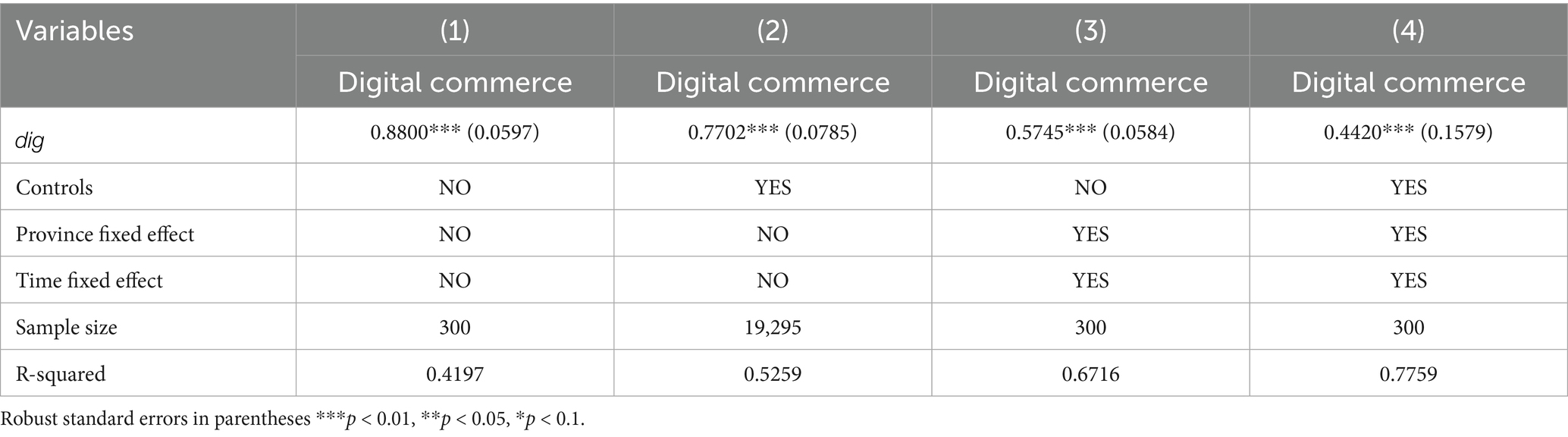

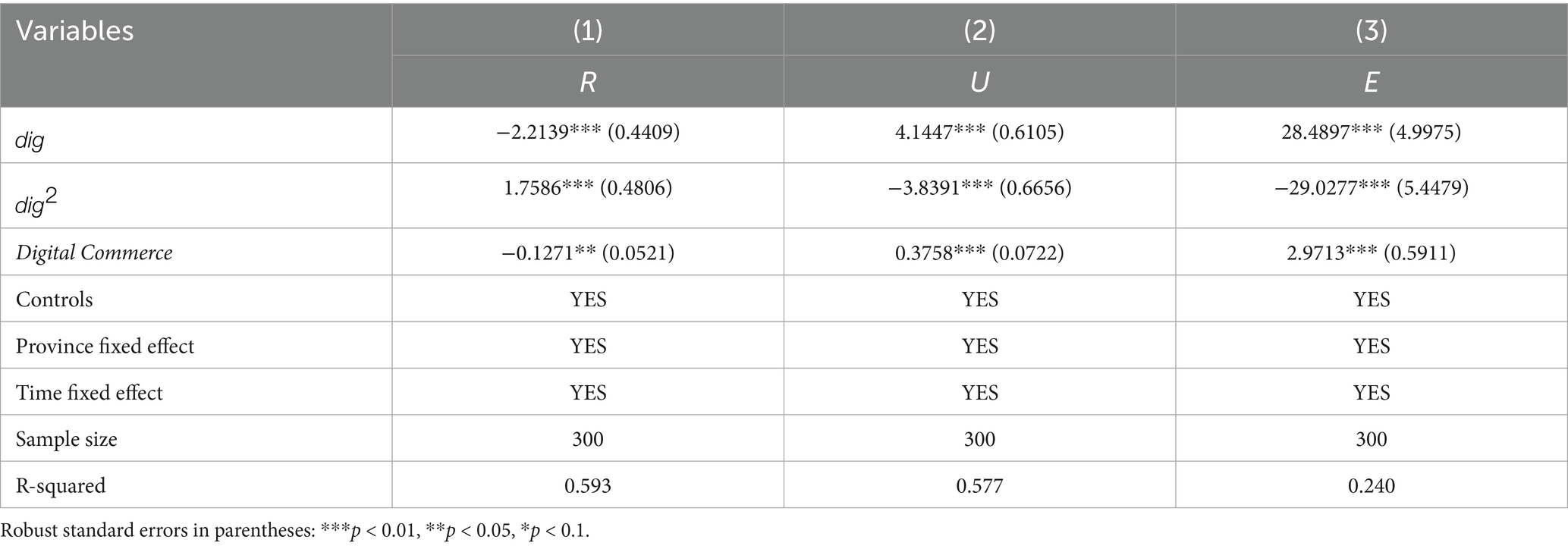

5.2.1 Digital commerce and industrial structure

Through empirical analysis, we have found that digital connectivity could narrow urban–rural income inequality through fostering industrial structures optimization. However, there is still an in-depth mechanism beneath this channel. As is demonstrated in 2.3.2, digital connectivity was expected to refine industrial structure via boosting digital commerce. Here, we present empirical results to support Hypothesis 3.

Table 12 displays that the coefficients of on digital commerce are all significantly positive at the 1% level, which implies that digital connectivity has a positive influence in digital commerce. This finding is consistent with the existing literature (Kimura and Chen, 2017; Chen and Ruddy, 2020; Zang et al., 2023). Table 13 presents the empirical evidence supporting for Hypothesis 4. Specifically, column (1) shows that the coefficient of digital commerce on R is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that digital commerce improved the rationalization of industrial structure. Column (2) and (3) reveals that the coefficients of digital commerce are both significantly positive, which verifies that digital commerce promotes the upgrading and advancing of industrial structure. These results align with the extant literature (Chang et al., 2024; Chu, 2024). Drawing on the above analysis, Hypothesis 4 that digital connectivity can improve industrial structure regarding upgrading and advancing of industrial structure through encouraging digital commerce is validated.

Table 14. Digital connectivity influences urban–rural income inequality through the industrial structure optimization channel.

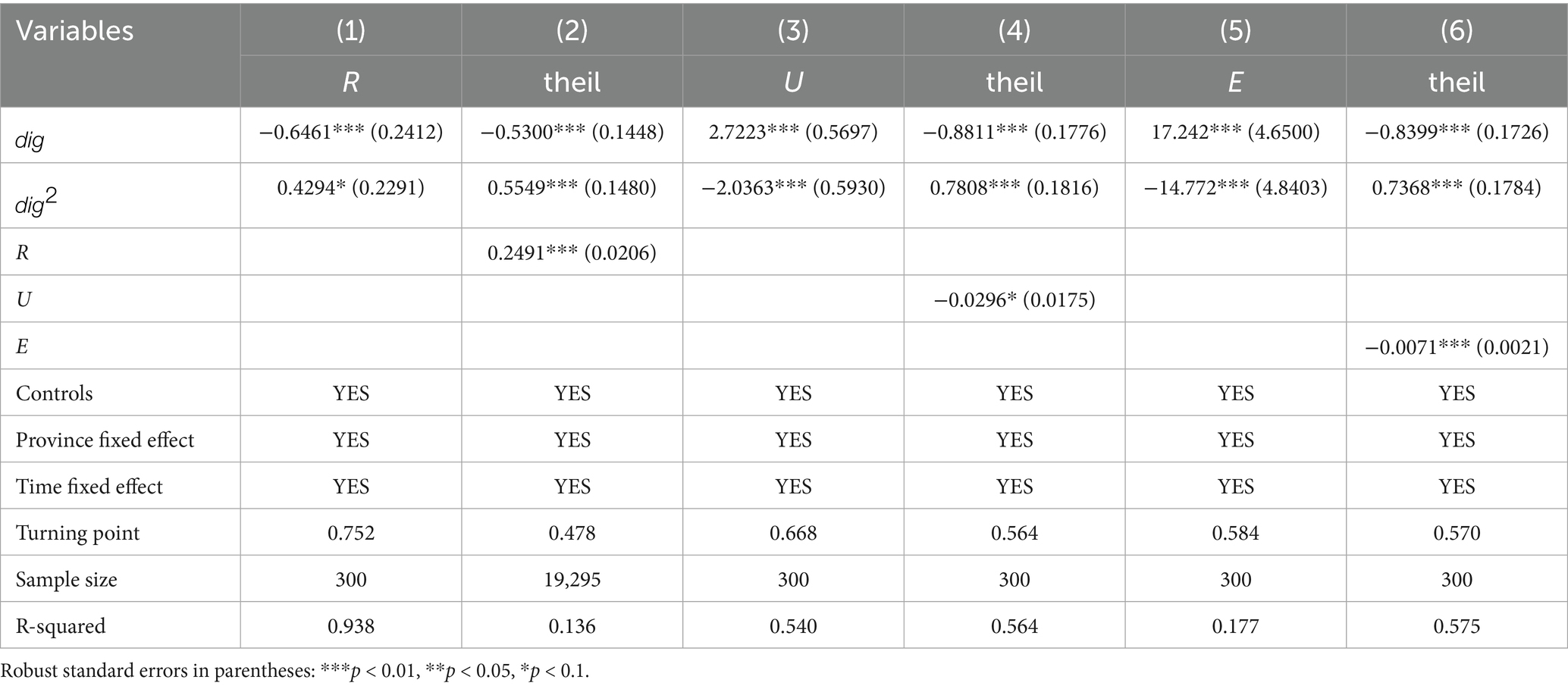

5.2.2 Industrial structure optimization

To test whether rural digital connectivity significantly enhances the optimization of industrial structure, we replace the three variables defined in section 2—rationalization, upgrading index, and advanced index of industrial structure—with urban–rural income inequality as the dependent variable in the basic model. Table 14 presents the fixed effects model estimation results, examining whether digital connectivity reduces urban–rural income inequality by improving industrial structure. In column (1), the coefficient of is −0.6461, statistically significant at the 1% level, and the coefficient of is 0.4294, statistically significant at the 10% level. This implies that when R is smaller than the turning point (0.752), digital connectivity significantly lowers the R and a small R indicates a high level of industrial structure rationalization. Column (2) shows that R has a significant positive impact on urban–rural income inequality, with a coefficient of 0.2491 at the 1% level. These results display that rural digital connectivity narrows the urban–rural income inequality through enhancing industrial structure rationalization. We also identify that industrial structure upgrading and advancing have significant mediating effects. Specifically, in column (3) and (5), the coefficients of are both significantly positive and the coefficients of are both significantly negative, which demonstrates that rural digital connectivity promotes industrial structure upgrading and advancing when U and E are less than turning points. Column (4) and (6) show that the coefficients of U and E are both significantly negative at the 10 and 1% level, respectively. These results indicate that rural digital connectivity narrows the urban–rural income inequality by fostering industrial structure upgrading and advancing. Our findings support Hypothesis 3 and align with the extant research (Hong and Zhang, 2021; Li, 2021; Fan, 2022; Li et al., 2024).

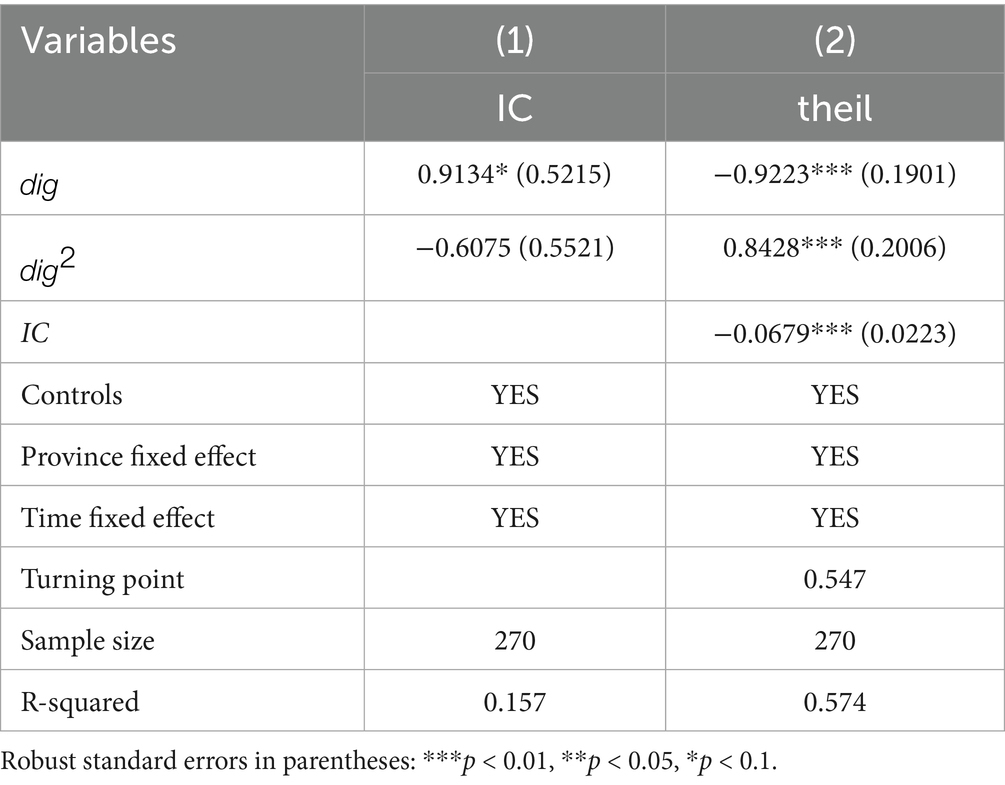

5.2.3 Industrial convergence

Beyond industrial structure optimization, rural industrial convergence serves as another significant channel for reducing the urban–rural income gap. In column (1) of Table 15, the estimated coefficient for is significantly positive at the 10% level, indicating that a 1 increase in rural digital connectivity led to an increase of 0.9134 in rural industrial convergence. However, the estimated coefficient of is insignificant, which implies that the quadratic relation does not exist between digital connectivity and industrial convergence. Column (2) of Table 15 shows that the coefficient of industrial convergence is significantly negative at the 1% level, with an estimation of −0.0679, demonstrating that the promotion of industrial convergence could narrow the urban–rural income inequality. Regarding aforementioned analysis, we conclude that rural digital connectivity narrows urban–rural income inequality through accelerating industrial convergence in rural areas, which supports Hypothesis 5.

Table 15. Digital connectivity influences urban–rural income inequality through the rural industrial convergence.

6 Conclusion and policy implications

Employing the Chinese provincial data on urban–rural income inequality and rural digital connectivity spanning from 2012 to 2021, this paper explores the effect of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality. The findings offer several notable insights and policy recommendations.

Firstly, the effect of rural digital connectivity on the urban–rural income gap is U shaped. The channel analysis reveals that rural digital connectivity refines industrial structure optimization by stimulating digital commerce, thereby narrowing the urban–rural income inequality. Policy should therefore be phased around the turning point. In regions below the turning point, priority should be given to closing infrastructure gaps in broadband and mobile base stations and pairing these actions with device subsidies for low-income rural households and tiered digital-skills training that progresses from basic literacy to e-commerce operations. In addition, rural last-mile feasibility should be enhanced through county pick-up and return stations and village access nodes. In parallel, expand digital financial inclusion to accelerating effective participation in digital supply chains (Xu et al., 2025a). In regions at or above the turning point, emphasis should shift from expanding capacity to improving use to guard against re-polarization. This requires strengthening upstream segments through cold-chain logistics, product standardization, and traceability, while simultaneously guiding platform economies and digital industries to create county-level jobs in operations, warehousing, and customer services.

Secondly, rural industrial convergence is also a main channel to narrow urban–rural income inequality, though it is more complex to achieve. The local government had better inspire this from different perspectives. In the first place, local government should energetically develop infrastructures, including transportation networks and digital infrastructure, enabling the growth of high-tech industries and facilitating industrial convergence. Moreover, tax incentives and subsidies are also can attract industries and encourage investment in rural areas. Specifically, the government should priorly encourage the development of agro-processing industries that add value to local agricultural products, creating jobs and stimulating demand for agricultural products, benefiting rural economies. In addition, education and skill training for the local labor force is substantial in the process of industrial convergence. Vocational training center are called for establishment to equip local workforce with needed skills.

Thirdly, it cannot be neglected that the influence of rural digital connectivity on neighboring provinces shows an “inverted U-shaped” characteristic, demonstrating a significant spatial spillover effect of “promotion to suppression” on urban–rural income inequality. This can be attributed to the “Siphon Effect,” where highly digitalized areas, with more advantages in resources, like infrastructure, beneficial policies and financial support, attract industries, skilled workers, and investments away from less developed regions. To alleviate this negative spatial effect, the government should refine factor-mobility mechanisms linking data, capital, and talent, thereby promoting coordination between county-level e-commerce and rural services to reduce resource inequalities across regions (Shi et al., 2025).

Fourthly, the heterogeneous analysis reveals that the suppression effect of rural digital connectivity on urban–rural income inequality is more significant in highly urbanized areas with free shipping services. To ensure and enhance the effectiveness of rural digital connectivity and further narrow urban–rural income inequality, the government should promote urbanization nationwide and facilitate the development of transportation in remote areas to encourage digital commerce.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: China Statistical Yearbook: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/Statisticaldata/yearbook/; China Rural Statistical Yearbook: https://cnki.istiz.org.cn/CSYDMirror/area/Yearbook/Single/N2025020018?z=D19; Peking University’s Index of Digital Financial Inclusion: https://idf.pku.edu.cn/zsbz/77bjdxszjryjzx515313.htm; China Urban Statistical Yearbook: https://cnki.istiz.org.cn/CSYDMirror/area/Yearbook/Single/N2025020156?z=D19; Provincial Statistical Yearbooks: http://www.tjnjw.com/niandu/diqunianjian-2024.html; Digital Commerce (AliResearch): http://www.aliresearch.com/indices/idrcc.

Author contributions

ZZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Non-free-shipping areas: Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, Guangxi, Hainan, Gansu and Ningxia. Note that some shops offer free shipping to some of these areas, like Ningxia, Guangxi, Gansu and Hainan. While there is no free shipping at all in Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai and Inner Mongolia.

References

Alcorta, L., Haraguchi, N., and Rezonja, G. (2013). “Industrial structural change, growth patterns, and industrial policy” in The industrial policy revolution II: Africa in the 21st century. Eds. J. E. Stiglitz, J. Y. Lin and E. Patel. (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 457–491.

Chan, K. W., and Wei, Y. (2021). “Two systems in one country: the origin, functions, and mechanisms of the rural-urban dual system in China” in Urban China reframed. Eds. W.-S. Tang and K. W. Chan. (Routledge), 82–114.

Chang, X., Yang, Z., and Abdullah, (2024). Digital economy, innovation factor allocation and industrial structure transformation—a case study of the Yangtze River Delta city cluster in China. PLoS One 19:e0300788.

Chen, C. (2016). The impact of foreign direct investment on urban-rural income inequality: evidence from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 8, 480–497. doi: 10.1108/CAER-09-2015-0124

Chen, C., Li, S., and Tian, Y. (2021). Integration of three industries in rural China and its provincial comparative analysis. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 37, 326–334.

Chen, D., and Ma, Y. (2022). Effect of industrial structure on urban–rural income inequality in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 14, 547–566. doi: 10.1108/CAER-05-2021-0096

Chen, L., and Ruddy, L. 2020 Improving digital connectivity: Policy priority for ASEAN digital transformation. Working papers PB-2020-07, economic research institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA)

Chu, J. (2024). The impact of digital economy development on China's industrial structure upgrading—an empirical analysis based on provincial panel data. Int. Bus. Econ. Stud. n. pag

Dai, Y., and Zeng, S. (2022). Effect of digital economy development on rural-urban income disparity: evidence from China. Proc. Bus. Econ. Stud. 5, 102–109. doi: 10.26689/pbes.v5i5.4415

Deng, X., Huang, M., and Peng, R. (2024). The impact of digital economy on rural revitalization: evidence from Guangdong. Heliyon 10, e28216–e28216. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28216

Devasmita, J. E. N. A. (2018). Economic integration and income convergence in the EU and the ASEAN. J. Econ. Libr. 5, 1–11.

Dong, Y., Luo, W., and Zhang, X. (2024). Information and communication technology diffusion and the urban–rural income gap in China. Pac. Econ. Rev. 29, 159–186. doi: 10.1111/1468-0106.12433

Elhorst, J. P. (2014). Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 37, 389–405. doi: 10.1177/0160017612452429

Fan, G. (2022). “Domestic study on digital economy, industrial upgrading and economic development” in 2022 6th Annual International Conference on Data Science and Business Analytics (ICDSBA) (Changsha, China), 212–218.

Gan, C., Zheng, R., and Yu, D. (2011). An empirical study on the effects of industrial structure on economic growth and fluctuations in China. Econ. Res. J. 46, 4–16+31. [in Chinese]

Guo, R., Ma, X., and Shi, T. (2020). “Research on the impact of consumers’ time sensitivity on E-commerce free shipping strategy” in 2020 Chinese Control and Decision Conference (CCDC), 4204–4209.

Guo, B., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Liang, C., Feng, Y., and Hu, F. (2023). Impact of the digital economy on high-quality urban economic development: evidence from Chinese cities. Econ. Model. 120:106194. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2023.106194

He, S. (2023). The effect of urbanization on income inequality. Adv. Econ. Manage. Polit. Sci. 23, 1–6. doi: 10.54254/2754-1169/23/20230337

Hong, M., and Zhang, W. (2021). Industrial structure upgrading, urbanization and urban-rural income disparity: evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 28, 1321–1326. doi: 10.1080/13504851.2020.1813244

Hu, X., Wan, G., Yang, C., and Zhang, A. (2023). Inequality and the middle-income trap. J. Int. Dev. 35, 1684–1710. doi: 10.1002/jid.3747

Humairoh, H., and Annas, M. (2023). E-commerce platform: free shipping promotion moderation on customer satisfaction. Int. J. Adv. Multidiscip. 1, 423–435.

Jiang, Q., Li, Y., and Si, H. (2022). Digital economy development and the urban–rural income gap: intensifying or reducing. Land 11:1980. doi: 10.3390/land11111980

Kakwani, N., Wang, X., Xue, N., and Zhan, P. (2022). Growth and common prosperity in China. China World Economy 30, 28–57. doi: 10.1111/cwe.12401

Kimura, F., and Chen, L. 2017 To enhance E-commerce enabling connectivity in Asia. Working papers PB-2017-01, economic research institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA)

Li, Y. (2021). The influence of the development of digital economy on the upgrading of China’s industrial structure. E3S Web Conf. 235:03062. doi: 10.1051/e3sconf/202123503062

Li, Z., Bai, T., Qian, J., and Wu, H. (2024). The digital revolution's environmental paradox: exploring the synergistic effects of pollution and carbon reduction via industrial metamorphosis and displacement. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 206:123528. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123528

Li, Z., Zhou, Q., and Wang, K. (2024). The impact of the digital economy on industrial structure upgrading in resource-based cities: evidence from China. PLoS One 19:e0298694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0298694

Lind, J. T., and Mehlum, H. (2010). With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 72, 109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.2009.00569.x

Lu, Z., Gou, D., Wu, Q., and Feng, H. (2025). Does the rural digital economy promote shared prosperity among farmers? Evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1649753. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1649753

Lynn, T., Rosati, P., Conway, E., Curran, D., Fox, G., and O’Gorman, C. (2022). “Infrastructure for digital connectivity” in Digital towns: Accelerating and measuring the digital transformation of rural societies and economies (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 109–132.

Lyu, J., Li, L., Liu, Y., and Deng, Q. (2025). Promoting common prosperity: how do digital capability and financial literacy matter? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 97:103779. doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2024.103779

Ma, X., Wang, F., Chen, J., and Zhang, Y. (2018). The income gap between urban and rural residents in China: since 1978. Comput. Econ. 52, 1153–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10614-017-9759-4

Park, S. (2017). Digital inequalities in rural Australia: a double jeopardy of remoteness and social exclusion. J. Rural. Stud. 54, 399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.018

Peng, Z., and Dan, T. (2023). Digital dividend or digital divide? Digital economy and urban-rural income inequality in China. Telecommun. Policy 47, 102616–102616.

Prieger, J. E. (2013). The broadband digital divide and the economic benefits of mobile broadband for rural areas. Telecommun. Policy 37, 483–502. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2012.11.003

Qiu, L., Zhong, S., and Sun, B. (2021b). Blessing or curse? The effect of broadband internet on China’s inter-city income inequality. Econ. Anal. Policy 72, 626–650. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2021.10.013

Qiu, L., Zhong, S., Sun, B., Song, Y., and Chen, X. (2021a). Is internet penetration narrowing the rural–urban income inequality? A cross-regional study of China. Qual. Quant. 55, 1795–1814. doi: 10.1007/s11135-020-01081-8

Shi, L., Zhao, J., Du, X., Tao, Y., Lei, T., Xu, M., et al. (2025). Achieving sustainable green agriculture: analyze the enabling role of data elements in agricultural carbon reduction. Front. Earth Sci. 13:1618999.

Song, Z., Wang, C., and Bergmann, L. (2020). China’s prefectural digital divide: spatial analysis and multivariate determinants of ICT diffusion. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 52:102072. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102072

Tang, L., and Sun, S. (2022). Fiscal incentives, financial support for agriculture, and urban-rural inequality. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 80:102057. doi: 10.1016/j.irfa.2022.102057

Townsend, L., Sathiaseelan, A., Fairhurst, G., and Wallace, C. (2013). Enhanced broadband access as a solution to the social and economic problems of the rural digital divide. Local Econ. 28, 580–595. doi: 10.1177/0269094213496974

Velaga, N. R., Beecroft, M., Nelson, J. D., Corsar, D., and Edwards, P. (2012). Transport poverty meets the digital divide: accessibility and connectivity in rural communities. J. Transp. Geogr. 21, 102–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.12.005

Wang, X., Li, M., He, T., Li, K., Wang, S., and Zhao, H. (2024). Regional population and social welfare from the perspective of sustainability: evaluation indicator, level measurement, and interaction mechanism. PLoS One 19:e0296517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0296517

Wang, M., and Liu, J. (2025). Deciphering the digital divide: the heterogeneous and nonlinear influence of digital economy on urban-rural income inequality in China. Appl. Econ. 57, 4861–4881. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2024.2364101

Wang, Y., Peng, Q., Jin, C., Ren, J., Fu, Y., and Yue, X. (2023). Whether the digital economy will successfully encourage the integration of urban and rural development: a case study in China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 21, 13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cjpre.2023.03.002

Wang, M., Yin, Z., Pang, S., and Li, Z. (2021). Does internet development affect urban-rural income gap in China? An empirical investigation at provincial level. Inf. Dev. 39, 107–122. doi: 10.1177/02666669211035484

Wu, L., Sun, L., Qi, P., Ren, X., and Sun, X. (2021). Energy endowment, industrial structure upgrading, and CO2 emissions in China: revisiting resource curse in the context of carbon emissions. Resour. Policy 74:102329. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102329

Xia, H., Yu, H., Wang, S., and Yang, H. (2024). Digital economy and the urban–rural income gap: impact, mechanisms, and spatial heterogeneity. J. Innov. Knowl. 9:100505. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2024.100505

Xiong, X., Wang, Y., Liu, B., He, W., and Yu, X. (2023). The impact of green finance on the optimization of industrial structure: evidence from China. PLoS One 18:e0289844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289844

Xu, M., Lu, Z., Wang, X., and Hou, G. (2025b). The impact of land transfer on food security: the mediating role of environmental regulation and green technology innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1538589. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1538589

Xu, M., Shi, L., Zhao, J., Zhang, Y., Lei, T., and Shen, Y. (2025a). Achieving agricultural sustainability: analyzing the impact of digital financial inclusion on agricultural green total factor productivity. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 8:1515207. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2024.1515207

Xu, Y., and Tao, J. (2024). Digital dividend or digital divide? – Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 57, 5033–5048. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2024.2387366

Yi, J., Dai, S., Li, L., and Cheng, J. (2024). How does digital economy development affect renewable energy innovation? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 192:114221. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2023.114221

Zang, Y., Hu, S., Zhou, B., Lv, L., and Sui, X. (2023). Entrepreneurship and the formation mechanism of Taobao villages: implications for sustainable development in rural areas. J. Rural. Stud. 100:103030. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2023.103030

Zhang, D., Ma, X., Zhang, J., and Deng, Q. (2019). Can consumption drive industrial upgrades? Evidence from Chinese household and firm matching data. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 56, 409–426. doi: 10.1080/1540496X.2019.1610878

Zhou, Q. (2024). Does the digital economy promote the consumption structure upgrading of urban residents? Evidence from Chinese cities. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 69, 543–551. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2024.04.001

Zhou, X., Wang, Y., and Han, M. (2025). Bridging the digital divide: how does rural digitalization promote rural common prosperity? Front. Earth Sci. 13:1591924. doi: 10.3389/feart.2025.1591924

Zhou, S., Yang, X., and Liao, Z. (2022). A study of industrial convergence in the context of digital economy based on scientific computing visualization. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2022/4025875

Appendix 1

Step 1, Normalization. For positive indicators,

For negative indicators,

Where denote the raw value of indicator for province in year

Step 2, Entropy computation. Define the indicator share

The entropy of indicator is computed as:

The information diversity is: , the higher the value of , the greater the impact of indicator

Step 3, the weights of indicator are computed as:

The composite index for province in year is

Keywords: rural digital connectivity, urban–rural income inequality, spatial analysis, digital commerce, rural common prosperity

Citation: Zhang Z and Lu Y (2025) Digital technology-driven rural common prosperity: a case study of China narrowing the income gap between urban and rural areas. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 9:1725607. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2025.1725607

Edited by:

Tingting Bai, Yangzhou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Houjian Li, Sichuan Agricultural University, ChinaMing Xu, Southwest University of Political Science & Law, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yimin Lu, bHV5bTA0MDRAZ21haWwuY29t

Zimo Zhang

Zimo Zhang Yimin Lu

Yimin Lu