- 1Social Mobility Lab, College of Public Health and Human Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA

- 2Disability and Social Interaction Lab, School of Psychological Science, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA

- 3College of Communication and Education, Chico State Autism Clinic, California State University, Chico, CA, USA

Physical activity (PA) participation is widely recognized as a critical component of health and development for disabled and non-disabled children. Emergent literature reflects a paradigm shift in the conceptualization of childhood PA as a multi-dimensional construct, encompassing aspects of physical performance, and self-perceived engagement. However, ambiguity remains around how participation as a health construct is integrated into PA research. The primary objective of the present mini-review is to critically examine current conceptual and methodological approaches to evaluating PA participation among disabled children. We conducted a systematic review of contemporary literature (published between 2000 and 2016). Seventeen articles met inclusion criteria, and their research approach was classified into guiding framework, definition of the key construct, and measurement used. The primary guiding framework was the international classification of functioning, disability and health. An explicit definition of PA participation was absent from all studies. Eight studies (47%) operationalized PA and participation as independent constructs. Measurements included traditional performance-based aspects of PA (frequency, duration, and intensity), and alternative participation measures (subjective perception of involvement, inclusion, or enjoyment). Approximately 64% of included articles were published in the past 2 years (2014–2016) indicating a rising interest in the topic of PA participation. Drawing from the broader discussion of participation in the literature, we offer a working definition of PA participation as it pertains to active, health-associated behaviors. Further description of alternative approaches to framing and measuring PA participation are offered to support effective assessment of health status among disabled children.

Introduction

Engagement in moderate to high intensity physical activity (PA) during childhood is advocated for in the promotion of optimal health outcomes and may offset predisposed risk for the development of secondary health conditions experienced by disabled children (1–3). Participation in PA opportunities is a fundamental childhood experience that fosters the psychosocial development of interpersonal skills, self-confidence, and self-efficacy (4). Increased PA participation is a primary goal expressed by parents and professionals for disabled children (5–7). Given our focus on physiological and psychosocial health outcomes, we use the term PA participation in reference to “engagement in a physically demanding movement, sport, game, or recreational play that results in energy expenditure and perceptions of communal involvement” (8, 9).

A consistent understanding of the PA participation construct is necessary for key stakeholders to successfully describe the health status of disabled children. Participation is broadly conceptualized as “involvement in life situations” (10) within psychology and disability related literature, but ambiguity surrounds the intended meaning of the term (8, 9) as a measurable index of health relative to being physically active. Recent efforts to integrate this construct in health literature are exemplified by Kang and colleagues (11). For children who experience physical disabilities, they define optimal recreation and leisure participation as the quality of child–environment interactions reflected in individualized (objective and subjective) physical, social, and self-engagement outcome measures (p. 1735). Kang et al. (11) cautions against inferring poor health from observed differences in frequency and intensity of PA participation between disabled and non-disabled children, without consideration for quality of children’s experiences. Misperceptions about the extent to which a child can participate may result in fewer opportunities or expectations for disabled children and reduce engagement in this health-promoting behavior. Therefore, there is a critical need to further examine health indicators in an inclusive manner. The first step is to reach consensus on how PA participation is effectively discussed and measured as a health indicator for disabled children.

Framing Physical Activity Participation

Physical activity has been traditionally discussed from a medical model framework in which health resides in the individual, represented by the absence of illness and body impairments. In response, PA has routinely been defined as “bodily movements that result in energy expenditure” (12). It is commonly operationalized as the frequency of activity attendance (13–16) or average daily time spent engaged at given intensity levels (e.g., light, moderate-to-vigorous) (17, 18). Subsequent attention has been given to identifying key activity restrictions or anatomical impairments, such as muscle weakness or low motor skill proficiency, to explain the limited PA engagement of disabled children (17, 19).

When using physiological performance outcomes as the single indicator of PA, there is an inherent assumption that functional deficits will inhibit disabled children from becoming “full” participants in community activities or sports teams. Reduced opportunities may limit a child’s exposure to fundamentally important physical, social, and personal experiences for health development. From an equity standpoint, additional qualifiers are needed to describe and appropriately measure PA patterns as a health index across disabled and non-disabled children. This requires a comprehensive discussion of both physical performance and psychosocial aspects of inclusion. For example, measures of self-concept (20), identity (4), and enjoyment (21) need to be considered alongside fitness and motor skill proficiency, to allow for more accurate and sensitive measurement of PA participation improvement among disabled children. Efforts to capture this multi-dimensional health aspect of PA for disabled children use the term “PA participation” [e.g., Ref. (11, 13)].

The term participation gained hold as a health indictor following the introduction of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001 (10). The ICF reflects a shift away from the impairment-based disablement framework toward emphasis on the personal, social, and environmental impacts of disability on health (22). In contrast to the traditional medical model’s focus on individual attributes of health, this contemporary biopsychosocial model takes the perspective that disability occurs at a person-in-environment level. Within this framework, participation describes the extent to which a child is socially engaged in child-relevant life situations, such as organized and school-related sports, games, and recreational play with peers in the community (11, 23).

Ross et al. (23) published a guide for researchers to advance the study of childhood PA participation. Their guide includes three steps: (1) identify a health framework, (2) clearly define outcomes that operationalize PA within the context of a given research project, and (3) select appropriate PA measurements that map back onto the targeted conceptual dimension of health. As an extension of Ross et al. (23), the primary objective of the present mini-review is to critically examine current conceptual and methodological approaches to examining PA participation among disabled children. A systematic review of contemporary literature (published between 2000 and 2016), explicitly investigating PA participation as a health construct for disabled children, was conducted. The operationalized definition of this key construct and implemented measurement practices were evaluated to support our understanding of this phenomenon and inform future research efforts.

Methods

A systematic review of contemporary literature (January 2000–January 2016) was conducted to examine the conceptualization and measurement practices for PA participation among disabled children. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) standard guidelines were followed, as per recommended practice (24). An electronic database search was conducted in February 2016 and detailed in Appendix A in Supplementary Material.

Initial Screening and Inclusion

Given strong links between PA participation and health among disabled children (2, 25), the primary objective of this study was to examine the use of this term in reference to active, health-associated levels of PA. The primary inclusion criterion was the use of the key terms “physical activity, sport, active, or recreation” in combination with “participation” as a measurable construct. Articles were excluded if the term PA referred to children’s leisure or more broadly defined participation outside-of-school or in daily life activities. Three trained research assistants independently screened titles and abstracts using this primary inclusion criteria, in addition to the following: (a) target population included children or youth, mean age ≤18 years, (b) must have included primary data other than case reports, (c) available in English, and (d) published in a peer-review journal. Exclusion criterion included (a) absence of the key words from the title, abstract, or the text body, (b) participants’ mean age was outside the target age range, (c) disabled children were not included as participants, or (d) the term “PA participation” was not used as a measurable outcome.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Articles retained after the initial screening underwent full review by three independent researchers. Data on study characteristics, key term definitions, and related measurement and methodology characteristics were extracted and synthesized. Any ambiguity around how the key term was used in an article was discussed among primary authors. The final data set was reviewed for emergent themes in the guiding framework, definition of key terms and assessment measures. A summary of the search and screening process can be found in Appendix A in Supplementary Material.

Results

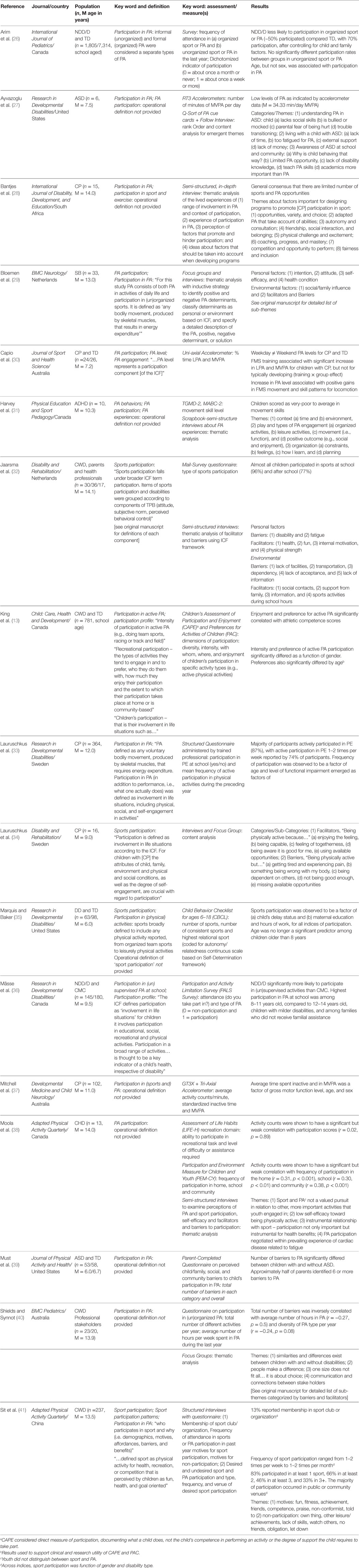

A total of 17 articles were included in this review (13, 26–41). Key study characteristics of the included articles are presented in Table 1. The majority of studies were published within the last 2 years (n = 11, 64% published 2014–2016), and most frequently published in Research in Developmental Disability (27, 33, 35, 36) or Disability and Rehabilitation (32, 34). Articles were primarily published in journals within psychology or medical related fields (e.g., BMC pediatrics, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, Disability and Rehabilitation, Child: Care, Health and Development). Public health and kinesiology journals, although the minority, were also represented in our sample (e.g., Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, Journal of Physical Activity and Health, and Journal of Sport and Health Sciences). There were only one or two articles per year published between 2007 and 2013. Prior to 2007, only one article published in 2002 met inclusion criteria (41). The majority of the research was conducted in Canada (n = 5, 29%) and included participants aged 6–12 years (middle childhood, n = 11, 65%) who were representative of a broadly defined disability population (n = 5, 29%).

Table 1. Key study characteristics of included articles. Includes (1) journal and country of publication; (2) Description of participant population (n = sample size; M = mean age in years of sample); (3) Key word pertaining to physical activity participation used and definition when provided; (4) Assessment and measure(s) used to capture the key construct; and (5) brief summary of associated results.

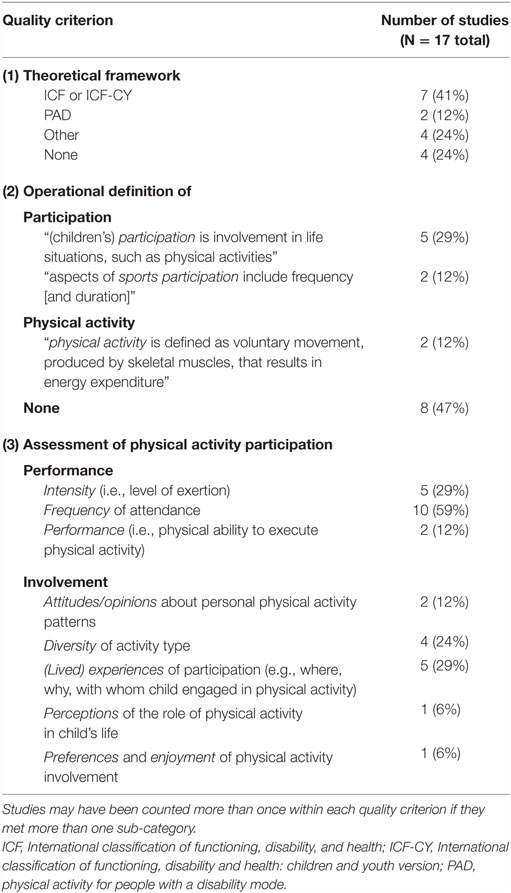

Table 2 summarizes the research approach outlined by the included studies to investigate PA participation. It is organized in accordance with Ross et al.’s (23) guidelines, classifying the approach into (a) the guiding framework, (b) the operational definition of PA participation, and (c) aspects of the measurement tools used to capture this key construct.

Table 2. Number of included articles reporting steps of research approach classified as (1) Theoretical guiding framework, (2) Operational definition of key construct – participation and/or physical activity, and (3) Assessment used to measure physical activity participation along a performance and/or involvement dimension.

The WHO-ICF (10), or the corresponding 2007 children’s version [ICF-CY; (42)], was the primary guiding framework used (n = 8, 47%) (13, 29, 30, 32–34, 36, 37). The Physical Activity for Persons with Disability (PAD) framework, a PA-specific rendition of the ICF, was utilized in two articles (29, 40). Alternative frameworks included the Social–ecological model (39), Systems Theory (27), Theory of Planned Behavior (32), and Sports Participation Theory (41). An operational definition of PA participation was not explicitly provided within any of the included literature. Instead, when an operational definition was provided, participation and PA were presented as independent constructs. Participation was defined by approximately one-third of the studies (n = 5, 29%) as the “involvement in life situations, … such as physical activity” (13, 33–36) – a direct quote from the WHO-ICF framework [(10), p. 10] – or stated that “sports [physical activity] participation falls under the broader ICF term ‘participation’” (32). Two studies noted “aspects of sports participation include frequency, duration, and social (or subjective) experiences” (35, 36). PA was operationally defined by only two studies, with both referencing Caspersen’s [(12), p. 126] 1985’s definition: “voluntary movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure” (29, 33). Nearly half of the studies did not provide an operational definition of either participation or PA (n = 8, 47%).

In accordance with Ross et al.’s (23) taxonomy of PA measurement, 10 studies (59%) used traditional performance-based measures of PA. This included outcomes of percent time in moderate-to-vigorous PA [i.e., intensity; (30)], number of PA opportunities attended in the last 6 months or year [i.e., frequency; (26, 33, 35, 36)], or physical ability to execute PA tasks [i.e., motor performance; (31)]. Three studies used an accelerometer to capture this data, whereas the remaining eight studies used PA-oriented surveys, daily logs, or interviews.

Physical activity was measured along an alternative involvement dimension of participation within 14 studies (82%). Assessments used included the Children’s Activity, Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) measure (13), the Child Behavior Checklist [CBCL; (35)], and the Participation and Activity Limitation Survey [PALS; (36)]. Emergent themes from questionnaires and interviews included questions of children’s experiences during PA (e.g., where, why, and with whom; 29% of studies), the number of different types of PA opportunities they attended (i.e., diversity; 29% of studies), and their attitudes or opinions about personal PA (12% of studies) and their perceptions or level of enjoyment during PA (12% of studies). Of the 13 studies that used an involvement-oriented measure of PA participation, seven (41%) concurrently assessed PA participation with a performance-oriented measure and either referred to the ICF/ICF-CY or explicitly defined participation as a health construct.

Included studies were primarily descriptive research designs and aimed to (a) describe the perceptions and experiences of PA participation among disabled children and key stakeholders (13, 27–29, 31–34, 38, 41), (b) identify barriers and facilitators to PA participation (28, 29, 31, 34, 35), and/or (c) compare PA participation across groups of disabled children and in relation to non-disabled peers (13, 26, 30, 35, 36, 39). Key outcomes associated with these aims are presented in Table 1.

Discussion

The primary objective of this mini-review is to critically examine current conceptual and methodological approaches to examining PA participation as an index of health among disabled children. The spike in publications inclusive of this term in 2015 indicates a growing interest in this phenomenon. As anticipated, discussion of PA participation is predominately occurring within fields of psychology and medical rehabilitation research [e.g., Ref. (8, 9, 11)]. The descriptive nature of the included studies, aimed at identifying what PA participation looks like and what it means to disabled children, indicates our understanding of this construct as an index of health is still in its early stages.

We found two patterns for how researchers approached the conceptualization of PA participation. The first approach framed PA as a context in which participation occurs. Articles using this approach started with the WHO-ICF/ICF-CY definition of participation – “involvement in life situations” [(10), p. 5]. This was followed by the identification of PA as an important context in which children participate. For example:

The [ICF] defines participation as involvement in life situations and for children it involves participation in educational, social, recreational and [PA] [(36), p. 2246]

…children’s participation – that is their involvement in life situations such as personal maintenance, mobility, social relationship, home life and education. Existing measures vary in scope, with some focusing on children’s [PA], others on play, and some including school-based activities [(13), p. 29]

This approach contextualizes health behaviors within specific, child-relevant settings. While it provides a descriptive profile of what, where, with whom, and how often children engage in PA, it does not directly map these behaviors onto health outcomes. For example, Sit et al. (41) concluded that the number of sports disabled children attended was associated with their degree of functional impairment. There are challenges, however, with translating this to a scale of health, because we know little about the children’s physical and psychosocial experiences while engaged in sport. Similarly, differences in frequency or intensity between age groups, gender, or disability status (13, 26, 33, 35–37, 41) are difficult to use as a direct comparison of health status across groups. For example, children of varying disability status may report low PA intensity due to physical impairments but equitable perceptions of communal involvement (43). However, this approach offers an important first look at the factors and mechanisms associated with PA participation that may be unique to disabled children.

The second approach framed PA as a multi-dimensional construct, with participation included as one of its dimensions. Compared to the first approach, PA served more directly as an index of physical and psychosocial health. It was described in terms of both performance outcomes (frequency and intensity of physical involvement in PA) and participation outcomes (social experiences, perceptions of inclusions or engagement, enjoyment). For example:

For this study, [PA] consists of both [PA] in activities of daily life, such as (hand) biking to school or active play, and participation in (un)organized sports. It is defined as any bodily movement, produced by skeletal muscles, that results in energy expenditure [(29), p. 2]

…empirical attention toward different aspects of sports participation (e.g., frequency and social nature of sport) should be expanded upon for a more comprehensive understanding of sports participation difference [between children with and without disabilities] [(35), p. 46]

This approach provides a foundation for mapping descriptive measures of PA participation to health status for disabled children. The connection between PA participation behaviors and health status is made transparent by the use of qualifiers. For example, Capio et al. (30) measured PA participation level (i.e., intensity) as an index of physical function and cardiovascular health. Harvey et al. (31) measured movement skill level as an index of PA participation competence or performance. King et al. (13) and Mâsse et al. (36) measured PA participation profiles to capture more global psychosocial experiences of children (enjoyment, perceptions of inclusion, satisfaction). From this framework, subsequent research can begin to translate descriptive PA participation behaviors onto scales of health. This effort would facilitate the identification of “levels” and “experiences” that put children at risk for poor health outcomes throughout life. It would further inform key aspects of PA participation that need to be supported throughout childhood to promote healthy development.

Drawing from the broader discussion of participation in the literature (8–11, 23, 44–48), we offer a working definition of PA participation as it pertains to active, health-associated behaviors:

Physical activity participation describes “experiences in physically demanding movement, sport, game, or recreational play that results in energy expenditure and perceptions of communal involvement.”

It can be qualified by:

(1) Level: frequency of attendance and intensity of physical exertion [e.g., Ref. (23, 48)].

(2) Quality of experience: self-perceived feelings of social inclusion, enjoyment, self-efficacy, and satisfaction [e.g., Ref. (47)].

(3) Overall profile: extent to which a child’s level of participation matches their expectation for a quality experience [e.g., Ref. (11, 43)].

Our emphasis on qualifiers aligns with contemporary works advocating that “participating in a sport activity for a child with a disability cannot be restricted to health and physical outcomes because participation does not only refer to taking part in an activity, particularly for children with disabilities” [(20), p. 748]. The predominant use of interviews in the studies reviewed suggests that self-report is the preferred method for capturing PA participation profiles of disabled children.

Future efforts are needed to translate our working definition of PA participation into inclusive assessments that map onto indices of health in childhood. Framing PA as a context in which participation occurs was the necessary first step in understanding PA as a dynamic health experience. When framed in this way, we effectively say that PA occurs in life situations (which is self-evident) and is a kind of participation (i.e., we are physically active by participating in PA). The use of participation thereby serves as a filler word and is not, in and of itself, representing a measurable health behavior. We therefore recommend, that moving forward, researchers adopt the term PA engagement when referring to PA as a context for participation and measuring physiological behaviors and outcomes (i.e., energy exertion, attendance frequency), synonymous with traditional discussion of PA levels (49, 50). PA participation can then serve to represent a broader health experience associated with dynamic child-environment interaction (i.e., self-perceived feelings of social inclusion, enjoyment, self-efficacy, and satisfaction). Differentiating PA engagement and PA participation consistently within health-related fields, and approaching PA participation as a measurable construct are further required to support effective assessment of the health status among disabled children.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conceptualization and development of this mini-review were made by the primary authors (SR, KB, SL, and LC). HT and JF made substantial contributions to the acquisition and synthesis of data. The manuscript was initially drafted by SR, with all authors contributing to the interpretation of results, development of the written manuscript. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00187

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives for 2020: Phase 1 Report Recommendation for the Framework and Format of Healthy People 2020 [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008). Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/PhaseI_0.pdf

2. Fowler EG, Kolobe TH, Damiano DL, Thorpe DE, Morgan DW, Brunstrom JE, et al. Promotion of physical fitness and prevention of secondary conditions for children with cerebral palsy: section on pediatrics research summit proceedings. Phys Ther (2007) 87(11):1495–510. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060116

3. Rimmer JH. Health promotion for people with disabilities: the emerging paradigm shift from disability prevention to prevention of secondary conditions. Phys Ther (1999) 79(5):495–502.

4. Taub D, Greer K. Physical activity as a normalizing experience for school-age children with physical disabilities: implications for legitimation of social identity and enhancement of social ties. J Sport Soc Issues (2000) 24(4):395–414. doi:10.1177/0193723500244007

5. Chiarello L, Palisano R, Maggs J, Orlin M, Almasri N, Kang LJ, et al. Family priorities for activity and participation of children and youth with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther (2010) 90(9):1254–64. doi:10.2522/ptj.20090388

6. Damiano DL. Activity, activity, activity: rethinking our physical therapy approach to cerebral palsy. Phys Ther (2006) 86(11):1534–40. doi:10.2522/ptj.20050397

7. Murphy NA, Carbone PS; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities. Promoting the participation of children with disabilities in sports, recreation, and physical activities. Pediatrics (2008) 121(5):1057–61. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-0566

8. Coster W, Khentani MA. Measuring participation of children with disabilities: issues and challenges. Disabil Rehabil (2008) 30(8):639–48. doi:10.1080/09638280701400375

9. Granlund M. Participation – challenges in conceptualization, measurement and intervention. Child Care Health Dev (2013) 39(4):470–3. doi:10.1111/cch.12080

10. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization (2001).

11. Kang L, Palisano RJ, King GA, Chirarello LA. A multidimensional model of optimal participation of children with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil (2014) 36(20):1735–41. doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.863392

12. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep (1985) 100(2):126–31.

13. King GA, Law M, King S, Hanna S, Kertoy M, Rosenbaum P. Measuring children’s participation in recreation and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC. Child Care Health Dev (2007) 33(1):28–39. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00613.x

14. Law M, King G, King S, Kertoy M, Hurley P, Rosenbaum P, et al. Patterns of participation in recreational and leisure activities among children with complex physical disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol (2006) 48(5):337–42. doi:10.1017/S0012162206000740

15. Maher CA, Williams MT, Olds T, Lane AE. Physical and sedentary activity in adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol (2007) 49(6):450–7. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00450.x

16. Palisano RJ, Copeland WP, Galuppi BE. Performance of physical activities by adolescents with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther (2007) 87(1):77–87. doi:10.2522/ptj.20060089

17. Capio CM, Sit CHP, Abernethy B, Masters RSW. Fundamental movement skills and physical activity among children with and without cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil (2012) 33(4):1235–41. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.02.020

18. Zwier JN, van Schie PE, Becher JG, Smits D-W, Gorter JW, Dallmeijer AJ. Physical activity in young children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil (2010) 32(18):1501–8. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.497017

19. Rimmer JH. Use of the ICF in identifying factors that impact participation in physical activity/rehabilitation among people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil (2006) 28(17):1087–95. doi:10.1080/09638280500493860

20. Dursun OB, Erhan SE, Ibiş EÖ, Esin IS, Keleş S, Şirinkan A, et al. The effect of ice skating on psychological well-being and sleep quality of children with visual or hearing impairment. Disabil Rehabil (2015) 37(9):783–9. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.942002

21. King G, Law M, Hurley P. The enjoyment of formal and informal recreation and leisure activities: a comparison of school-aged children with and without physical disabilities. Int J Disabil Dev Educ (2009) 56(2):109–30. doi:10.1080/10349120902868558

22. Jette AM. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health: ICF. Phys Ther (2006) 86(5):726–34.

23. Ross SM, Case L, Leung W. Aligning physical activity measures with the international classification of functioning, disability and health framework for childhood disability. Quest (2016):1–15. doi:10.1080/00336297.2016.1145128

24. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

25. Johnson CC. The benefits of physical activity for youth with developmental disabilities: a systematic review. Am J Health Promot (2009) 23(3):157–67. doi:10.4278/ajhp.070930103

26. Arim RG, Findlay LC, Kohen DE. Participation in physical activity for children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Int J Pediatr (2012) 2012:e460384. doi:10.1155/2012/460384

27. Ayvazoglu NR, Kozub FM, Butera G, Murray MJ. Determinants and challenges in physical activity participation in families with children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders from a family systems perspective. Res Dev Disabil (2015) 47:93–105. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.015

28. Bantjes J, Swartz L, Conchar L, Derman W. Developing programmes to promote participation in sport among adolescents with disabilities: perceptions expressed by a group of south African adolescents with cerebral palsy. Int J Disabil Dev Educ (2015) 62(3):288–302. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2015.1020924

29. Bloemen MAT, Verschuren O, van Mechelen C, Borst HE, de Leeuw AJ, van der Hoef M, et al. Personal and environmental factors to consider when aiming to improve participation in physical activity in children with spina bifida: a qualitative study. BMC Neurol (2015) 15:11. doi:10.1186/s12883-015-0265-9

30. Capio CM, Sit CHP, Eguia KF, Abernethy B, Masters RSW. Fundamental movement skills training to promote physical activity in children with and without disability: a pilot study. J Sport Health Sci (2015) 4(3):235–43. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2014.08.001

31. Harvey W, Wilkinson S, Pressé C, Joober R, Grizenko N. Children say the darndest things: physical activity and children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy (2014) 19(2):205–20. doi:10.1080/17408989.2012.754000

32. Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, De Blécourt ACE, Geertzen JHB, Dekker R. Barriers and facilitators of sports in children with physical disabilities: a mixed-method study. Disabil Rehabil (2015) 37(18):1617–23. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.972587

33. Lauruschkus K, Westbom L, Hallström I, Wagner P, Nordmark E. Physical activity in a total population of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil (2013) 34(1):157–67. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.005

34. Lauruschkus K, Nordmark E, Hallström I. “It’s fun, but?…” Children with cerebral palsy and their experiences of participation in physical activities. Disabil Rehabil (2015) 37(4):283–9. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.915348

35. Marquis WA, Baker BL. Sports participation of children with or without developmental delay: prediction from child and family factors. Res Dev Disabil (2015) 37:45–54. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.028

36. Mâsse LC, Miller AR, Shen J, Schiariti V, Roxborough L. Comparing participation in activities among children with disabilities. Res Dev Disabil (2012) 33(6):2245–54. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.002

37. Mitchell LE, Ziviani J, Boyd RN. Characteristics associated with physical activity among independently ambulant children and adolescents with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol (2014) 57(2):167–74. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12560

38. Moola FJ, Faulkner GEJ, Kirsh JA, Schneiderman JE. Developing physical activity interventions for youth with cystic fibrosis and congenital heart disease: learning from their parents. Psychol Sport Exerc (2011) 12(6):599–608. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.07.001

39. Must A, Phillips S, Curtin C, Bandini L. Barriers to physical activity in children with autism spectrum disorders: relationship to physical activity and screen time. J Phys Act Health (2015) 12(4):529–34. doi:10.1123/jpah.2013-0271

40. Shields N, Synnot A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr (2016) 16:9. doi:10.1186/s12887-016-0544-7

41. Sit CH, Lindner KJ, Sherrill C. Sport participation of Hong Kong Chinese children with disabilities in special schools. Adapt Phys Activ Q (2002) 19(4):453–71.

42. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Children & Youth Version: ICF-CY. Geneva: WHO Press (2007).

43. King G, Petrenchik T, Dewit D, McDougall J, Hurley P, Law M. Out-of-school time activity participation profiles of children with physical disabilities: a cluster analysis. Child Care Health Dev (2010) 36(5):726–41. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01089.x

44. van der Ploeg HP, van der Beek AJ, van der Woude LHV, van Mechelen W. Physical activity for people with disabilities: a conceptual model. Sports Med (2004) 34(10):639–49. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434100-00002

45. Badley EM. Enhancing the conceptual clarity of the activity and participation components of the international classification of functioning, disability, and health. Soc Sci Med (2008) 66(11):2335–45. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.026

46. Eriksson L, Granlund M. Conceptions of participation in students with disabilities and persons in their close environment. J Dev Phys Disabil (2004) 16(3):229–45. doi:10.1023/B:JODD.0000032299.31588.fd

47. Granlund M, Arvidsson P, Niia A, Bjorck-Akesson E, Simeonsson R, Maxwell G, et al. Differentiating activity and participation of children and youth with disability in Sweden: a third qualifier in the international classification of functioning, disability and health for children and youth? Am J Phys Med Rehabil (2012) 91(2 Suppl):S84–96. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31823d5376

48. Phillips R, Hogan A. Recreational participation and the development of social competence in preschool aged children with disabilities: a cross-sectional study. Disabil Rehabil (2015) 37(11):981–9. doi:10.3109/09638288.2014.949355

49. Dollman J, Okely AD, Hardy L, Timperio A, Salmon J, Hills AP. A hitchhiker’s guide to assessing young people’s physical activity: deciding what method to use. J Sci Med Sport (2009) 12(5):518–25. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2008.09.007

Keywords: assessment, disability, international classification of functioning disability and health, participation, physical activity, recreation and sport, systematic review

Citation: Ross SM, Bogart KR, Logan SW, Case L, Fine J and Thompson H (2016) Physical Activity Participation of Disabled Children: A Systematic Review of Conceptual and Methodological Approaches in Health Research. Front. Public Health 4:187. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00187

Received: 30 April 2016; Accepted: 23 August 2016;

Published: 05 September 2016

Edited by:

Frederick Robert Carrick, Bedfordshire Centre for Mental Health Research in Association with University of Cambridge, UKReviewed by:

Kenn Konstabel, National Institute for Health Development, EstoniaLinda Mullin Elkins, Life University, USA

Stefan Alexander Jackowski, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Copyright: © 2016 Ross, Bogart, Logan, Case, Fine and Thompson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samantha Mae Ross, cm9zc3NAb3JlZ29uc3RhdGUuZWR1

Samantha Mae Ross

Samantha Mae Ross Kathleen R. Bogart

Kathleen R. Bogart Samuel W. Logan

Samuel W. Logan Layne Case

Layne Case Jeremiah Fine1

Jeremiah Fine1