- Point-of-Care Testing Center for Teaching and Research, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

Objectives: To develop awareness of benefits of point-of-care testing (POCT) education in schools of public health, to identify learning objectives for teaching POCT, to enable public health professionals and emergency responders to perform evidence-based diagnosis and triage effectively and efficiently at points of need, and to better improve future standards of care for public health practice, including in limited-resource settings and crisis situations.

Methods: We surveyed all U.S. schools of public health, colleges of public health, and public health schools accredited by the Council on Education in Public Health (CEPH). We included accredited public health programs, so that all states offering public health education were represented. We analyzed survey data, public health books, and board certification guidelines. We used PubMed to identify public health curriculum papers, and assessed 2019 CEPH accreditation requirements. We merged POCT knowledge bases to design a new curriculum for teaching public health students and practitioners the principles and practice of POCT.

Results: Public health curricula, certification requirements, and textbooks generally do not include POCT instruction. Only one book, Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience, and one online course on public health preparedness address POCT and public health intervention issues. The topic, POC HIV/HCV ED testing, appeared in one course and POC diagnostics in local clinics, in another. Papers on public health curriculum have not incorporated POCT. No curriculum addresses POCT in isolation units during quarantine, despite evidence that recent Ebola virus disease cases in the U.S. and elsewhere proved unequivocally the need for POCT. The modular learning objectives identified in this paper were customized for public health students. Public health graduates can use boot camps, online credentialing, and self-study to acquire POCT skills.

Conclusions: Enhancing accreditation requirements, academic training, board certification, and field experience will generate public health healthcare professionals who will rely upon evidence-based medical decision making at points of care, including during crises when time is of the essence. A POCT-enabled public health workforce can help prevent and stop outbreaks. Public health-based medical professionals urgently need the skills necessary to perform POCT and prepare America and other nations for threats portending significant adverse medical, economic, social, and cultural impact.

Introduction

Point-of-care testing (POCT) is defined as diagnostic testing at or near the site of care (1). Catastrophic losses from the Ebola virus disease epidemic in West Africa and from other outbreaks, such as MERS-CoV in South Korea, reinforce the need for POCT. Educating public health practitioners to perform POCT directly at points of need will help control outbreaks of highly infectious threats. Avoiding costly pandemics will garner significant return on societal investments in teaching POCT in schools, colleges, and programs of public health. The U.S. and other nations that transiently enacted measures to enhance community resilience for Ebola virus disease during the 2014–16 epidemic and for other threats remain ill prepared. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) funding remains inadequate to support preparation and response in limited-resource regions abroad.

The CDC estimates that an infectious disease outbreak in Southeast Asia could cost the U.S. economy up to $40 billion in export revenue and put almost 1.4 million U.S. jobs at risk (2). The Global Health Security Agenda was launched in 2014 to promote international collaboration among nearly 50 countries to prevent, detect, and quell infectious disease outbreaks. According to one CDC official, “The economic linkages between the U.S. and these global health priority countries illustrate the importance of ensuring that countries have the public health capacities needed to control outbreaks at their source before they become pandemics” (2). However, the CDC may be forced to narrow its countries of operation, real-time surveillance, and early detection, and this, despite the most recent outbreaks of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Public health educators in the U.S. have not met the knowledge and skill levels needed for rapid response at points of care. Communities would be wise to develop countermeasures, such as immediately accessible diagnostic capabilities that enhance resilience in the event of contagion and quarantine, in part to ameliorate civil rights issues by supporting well thought-out and equitable care plans. POC-enabled public health concepts, knowledge, and skills must be codified by updating accreditation and certification requirements to include POCT. To help fill striking gaps discovered by our national survey, we designed multi-purpose curriculum topics and modular learning objectives that can be used to teach students and practitioners of public health the principles and practice of POCT.

Methods and Materials

Research Framework

We adopted a logical, systematic, integrated, and thorough research methodology leading to the POCT curriculum presented here. The research framework supports a harmonized curriculum practical for teaching in developed countries, such as the United States, Europe, and Japan, as well as in limited-resource countries, such as those in Africa and Asia. POCT has significant potential for preventing and limiting outbreaks of infectious diseases where they originate, if public health practitioners become educated in the principles and practice of POCT.

The Council on Education for Public Health (CEPH, https://ceph.org/) accredited (3) 64 schools of public health, colleges of public health, and public health schools (collectively abbreviated “SPHs”), and 117 public health programs (“PHPs”) in 2018 (4). CEPH accreditation lists provided the framework for systematic searches of curricula available online at SPH and PHPs in the U.S., including the District of Colombia. Four states, Delaware, South Dakota, Wyoming, and Vermont, do not have accredited SPH or PHPs. Five CEPH-accredited institutions outside the U.S. in Alberta Mexico, Montreal, Puerto Rico, and Taiwan were omitted.

Survey Scope

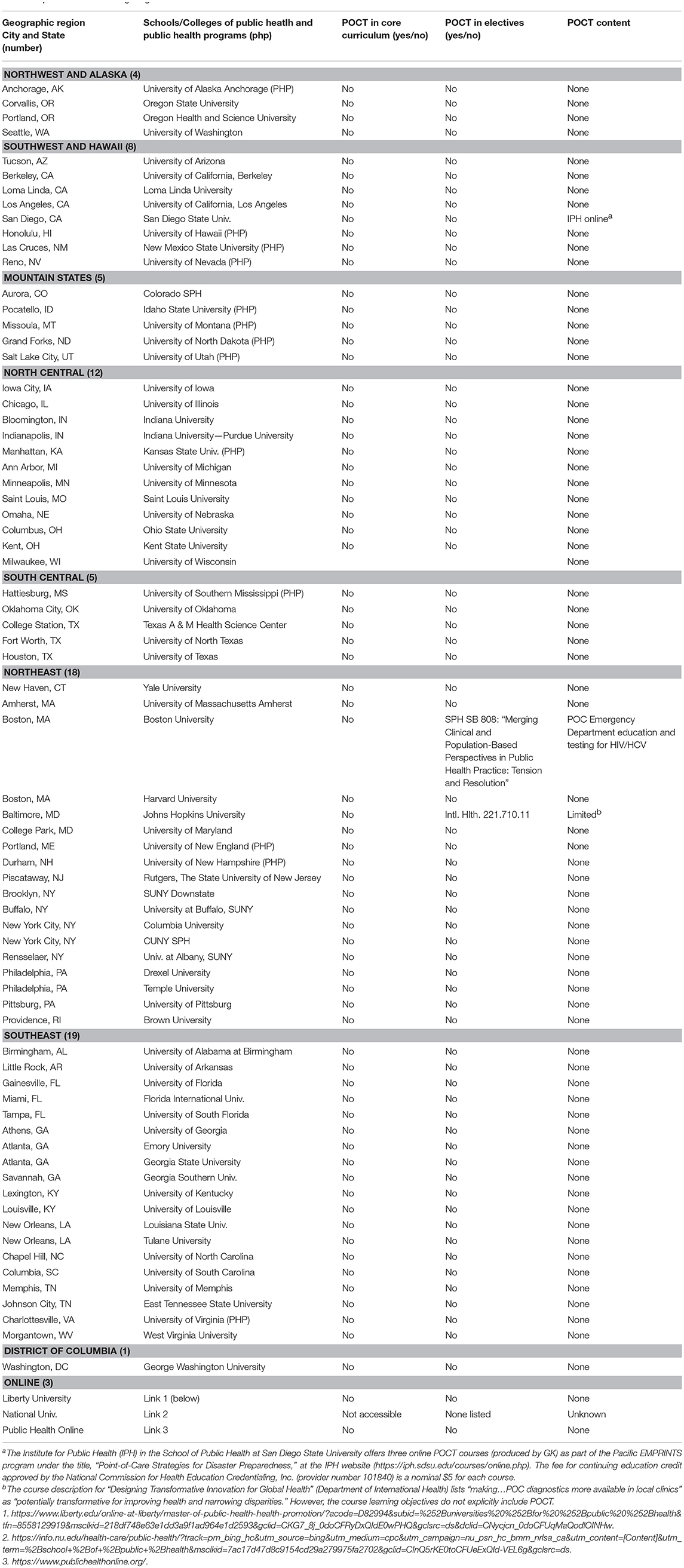

The survey was administered to all schools of public health, colleges of public health, and public health schools (referred to as “SPH”) accredited by the CEPH in the U.S. After removing 5 foreign institutions from the 64 listed by the CEPH, the remaining 59 accredited SPH were contacted successfully (100% inclusive rate) online by accessing their websites, all of which posted current curriculum. These 59 are located in 33 states plus 1 in the District of Columbia. Institutions within individual states number: 5—NY; 4 each—CA and GA; 3 each—FL, MA, PA, and TX; 2 each—IN, KY, LA, MD, OH, OR, and TN; and 1 each—the remaining 19 states excluding DE, SD, VT, and WY, which have no SPHs or PHPs; plus 1 in Washington, DC.

To ensure geographic representation of all states, we included an additional 13 accredited public health programs (referred to as “PHPs”), in order that all states (100% inclusive rate) with public health educational institutions, that is, a total of (50 – 4 =) 46 states in the U.S., were represented. Multiple institutions in states with high populations balanced survey demography naturally. The total number of institutions surveyed was 72. The survey was completed in December, 2018.

Knowledge Bases

Extracted online university bulletins, catalogs, course descriptions, course titles, syllabi, elective descriptions, learning objectives, lists of competencies, program guides, slide presentations, and other publicly available resources were archived and searched for acronyms (e.g., POCT) and key words, such as bedside testing, diagnostic testing, field testing, isolation, molecular diagnostics, pathogen detection, point-of-care testing, and reference laboratory, all compiled in a search dictionary used to assure consistency of researchers.

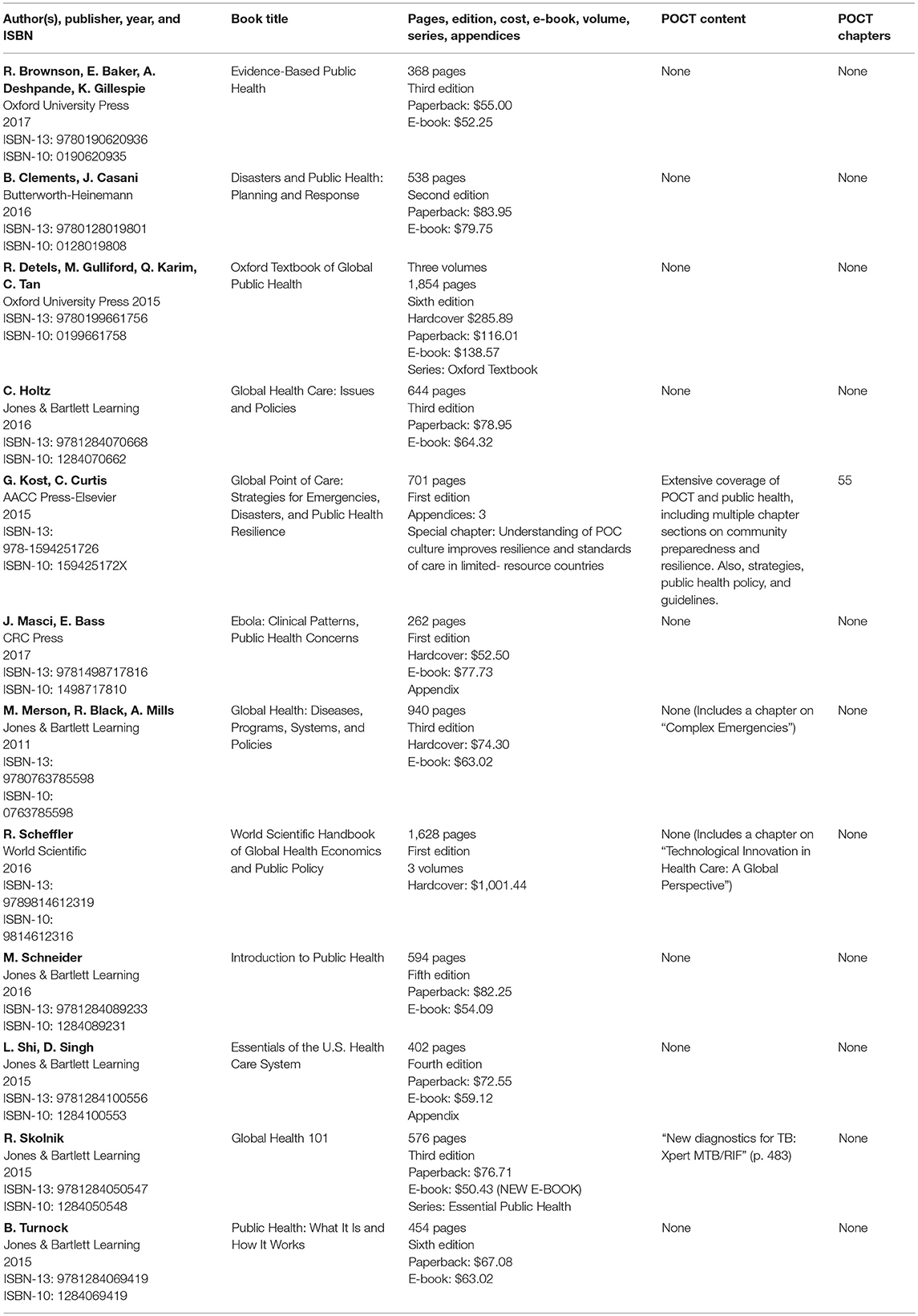

Tables of contents and indices of textbooks and reference books addressing public health issues were identified through Google, Amazon, and other online searches. Twelve highly ranking and relevant books were selected for tabulation. Inclusion criteria comprised Amazon rankings, public health content relevant to POCT, recent publication (2015 and later), and/or emphasis on global health, in view of the impact of POCT worldwide. Foreign language books were excluded.

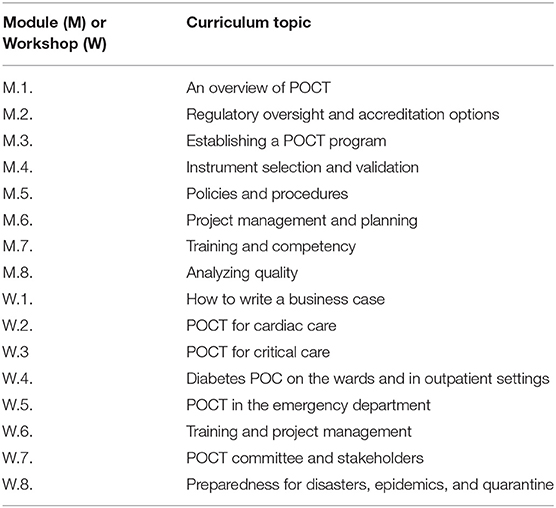

The American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC, www.aacc.org) provided information about POC Coordinator credentialing courses found at https://www.aacc.org/store/certificate-programs/11700/point-of-care-specialist-certificate-program-2018 and https://www.aacc.org/store/certificate-programs/11700/improving-outcomes-through-point-of-care-testing-certificate-program-2018. We also investigated the learning objectives for a “boot camp” (5) intended for new POC operators. We tabulated separately a few representative online programs in public health, although information available at their websites was inadequate or non-existent for the purposes of this national survey.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a 1-h on-demand course in Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments'88 (CLIA) waived testing at https://www.cdc.gov/labtraining/training-courses/ready-set-test.html. Learning objectives are: a) to identify the CLIA requirements for performing waived testing, b) to follow the current manufacturer's instructions for the test, and c) to describe good testing practices to be used while performing waived tests (6, 7). The CDC is a Certified in Public Health (CPH) provider that offers 2.0 CPH recertification credits for completing this course. Although the course is dated, CDC insights were integrated into the public health curriculum we designed. Additionally, the curriculum includes instruction on the classification system (CLIA-waived, moderately complex, and complex) used by the FDA.

Results

Accreditation Requirements and Board Certification

We assessed CEPH accreditation criteria, using the “redline” version published on March 16, 2018 (3). POCT training is not listed among accreditation requirements for public health institutions. The National Board of Public Health Examiners (NBPHE, https://www.nbphe.org/) did not list POC concepts among the Certified Public Health (CPH) content outline (https://s3.amazonaws.com/nbphe-wp-production/app/uploads/2017/05/Content OutlineMay-21-2019.pdf) for 2019 (8).

Professional Associations

The American Public Health Association (https://www.apha.org/) does not list POCT among topics and issues, not even in the “preparedness” category. We checked the Association of Public Health Laboratories and American Society for Microbiology (ASM) at https://www.cdc.gov/labtraining/external-partner-training.html. Neither currently posts POCT curricula, although the ASM and its Academy, in collaboration with the Infectious Disease Society of America, promotes webinars and general education in POC molecular diagnostics.

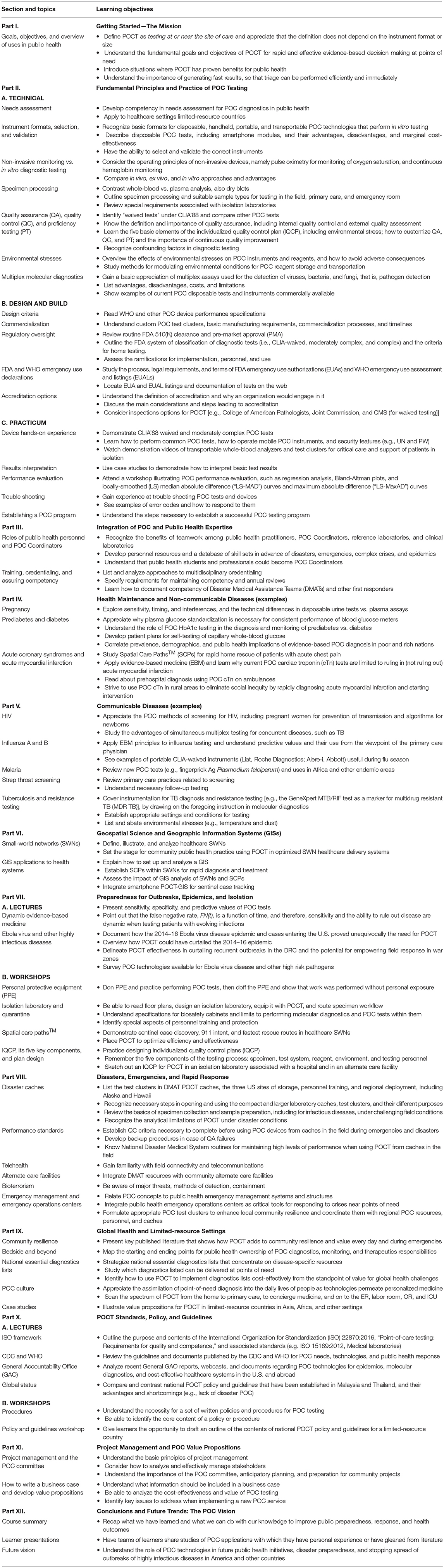

POC Curriculum for Limited-Resource Nations

We drew on essential learning objectives in an original lecture (~500 slides) and workshop (laboratory) professional course for POC operators in limited-resource settings created by Kost et al. (9) in collaborations with a commercial diagnostics company, professional associations, and universities. This course has been taught worldwide (by its creators and other educators) over the past decade, typically in the format of two morning lectures followed by an afternoon hands-on workshop using capillary blood samples and POC devices that generate real-time results. Specifically, the curriculum has been taught and well-received in Canada, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, China, and SE Asia (Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam), in the US for visiting scholars from Brazil, and in other countries.

Monographs

Table 1 lists public health books. Only one, Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience, contributed by 105 authors and produced by the POCT•CTR (10), covers POCT topics relevant to public health and vice-versa, such as biohazards, community preparedness, disaster caches, geographic information systems, global resilience, national guidelines, molecular diagnostics (an extensive seven-chapter section), needs assessment, rapid diagnosis of critically ill patients with life-threatening diseases, POC culture, public health policy, and strategies for enhancing resilience.

Online Training

Topics, learning objectives, and lectures of the AACC online courses for POC operators, often used for credentialing of POC Coordinators who supervise bedside testing programs in U.S. hospitals, were found at the links in Methods. The basic course is recommended first before taking the clinical course. POCT•CTR authors contributed several topics to the second course. Certificates issued upon passing exams are recognized as evidence of competency in POCT. AACC educational programs are accessible for a fee, and hence, their use is limited. Additionally, they may be phased out in lieu of a new national board examination, passage of which will lead to board certification in POCT.

Current Status

Table 2 shows that virtually no SPHs or PHPs curricula address POCT. A few of the course catalogs and bulletins describe limited laboratory training, mainly in bench microbiology. The purpose, design, instrumentation, operation, personnel, and training necessary to implement an isolation laboratory for highly infectious diseases were not mentioned. Community-based public health appeared in several of the curricula without describing the roles of self-testing, primary care POCT, pathogen detection, alternate care facilities, isolation laboratories, or field preparation. There was no discussion of Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMATs) or the contents of their National Disaster Medical System diagnostic instrument caches for use at points of need during crises.

San Diego State University SPH offers online POCT education produced by GK in association with Pacific EMPRINTS at the University of Hawaii (see Table 2). Courses comprise: Part I. Point-of-Care Strategies: Critical Care, Disaster Medicine, and Public Health Preparedness Worldwide, Part II. Point-of-Care Technologies Research Network (NIBIB, NIH), and Part III. Point-of-Care Strategies: Conclusions and Recommendations. These online courses are intended for public health personnel, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, dentists, veterinarians, laboratory managers, medical technologists, and emergency medical services personnel. The courses provide an introduction to POCT, discuss how POCT can be used for decision-making in acute care and rural settings, and summarize lessons have been learned about POCT from recent disasters. They conclude with recommendations for emergency preparedness using integrated POCT technologies. Continuing education credits are offered for these courses.

Public Health Innovation

Based on the survey results, teaching experience, relevant chapters in Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disaster, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience (10) and in A Practical Guide to Global Point-of-Care Testing (11) (the two most current POCT compendiums), and on the several knowledge bases described in Methods, we designed original topic-based learning objectives tailored specifically for public health students and practitioners (Table 3).

This curriculum has been validated through decades of on-site teaching in both developed and limited-resource settings worldwide and has been used, either in whole or in part, for the development of national guidelines by ministries of public health, POC Coordinators who oversee POCT, online teaching, and other facets of professional POCT practice, as summarized in the two major compendiums above (10, 11) and in reference (1).

Discussion

POCT Public Health Curriculum

The curriculum we designed includes Part VIII, “Disaster Preparedness, Emergencies, and Rapid Response,” which heretofore, has never appeared in either public health schools nor in national POCT policy and guidelines (see Part X, Table 3), such as those implemented in Malaysia (12) and Thailand (13). Following Part I. Getting Started—the Mission, an introduction to the course, laboratorians could help teach Part II, particularly technical topics (Part II.A.) and the workshop practicum (Part II.C.). Faculty with field experience in POCT applications could teach “Health Maintenance and Non-communicable Diseases” (Part IV.) and “Communicable Diseases” (Part V.). Recent monographs (10, 11) provide the basic information for instructors and students alike.

Part VI. offers an overview of public health geospatial approaches important when positioning POCT in the community and coordinating it with spatial care paths™ in healthcare small-world networks. Parts VII and VIII are crucial to prepare future generations of interventional public health operatives, such as those working in the global health field covered in Part IX. The last two major didactic sections, Parts X and XI, could be covered in seminars. Faculty can establish their own POCT vision (Part XII) and engage in changing national accreditation standards to produce consistency of knowledge skills. The POCT curriculum for public health can be taught in a one quarter or semester course. Accompanying hands-on laboratories would enhance long-term educational recall.

Needs Fulfillment

No investigators have previously identified the magnitude of the educational gaps revealed by our national survey results. The POC curriculum we designed fills gaps in public health education and attempts to initiate a dialogue leading to availability of POC-enabled public health practitioners worldwide. We found only one educational article intended for “health professional students” (at the University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences), (14) one for “training of nurses,” (15) and one for OB-GYN residents (16) that were relevant to POCT. Another group addressed internet-based interactive education as a potential venue for education, but not specifically public health (17). None of the papers targeted POCT curricula for public health. We believe all students of public health should have the opportunity to learn the principles and practice of POCT, especially those studying community health, epidemiology, or planning, policy, and surveillance, as well as physicians and nurses seeking public health degrees, intending to work in rural or limited-resource settings, or preparing to become first responders for disasters and outbreaks of highly infectious diseases.

Editorial Leadership

A search using the website of the American Journal of Public Health (https://ajph.aphapublications.org/) returned no articles when using the term “point-of-care testing,” although “testing,” per se, appeared frequently, mainly with “HIV.” Similar results were found when searching the websites of the journal, BioMed Central Public Health (https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/) and Public Health, which yielded only two articles, neither focused on POCT, per se. A PubMed search for “public health curriculum” produced 178 papers, none of which addressed POCT or related topics. Conversely, when PubMed recovered POCT papers, none addressed public health curriculum. We recommend that editors of public health journals initiate dialogue, produce focus issues, and encourage education in POCT.

Accreditation Standards

POCT was not among the criteria that CEPH lists for accreditation (3), nor is it included in the NCEPH content for CPH Certification (8), as we recommend it should be (below). Therefore, absence of POCT instruction from the curricula for public health schools, colleges, and programs is not surprising. A direct approach for maturing the POC paradigm within the field of public health would be to revise accreditation requirements and include POCT explicitly in tables of contents and course descriptions for SPHs and PHPs. Some respite is offered to current public health practitioners through the free lectures and a training center described next.

Free Access

The POCT•CTR offers over three dozen online instructional YouTube videos at https://www.youtube.com/user/POCTCTR/videos (accessed January, 2019). Additional academic speakers who address regional POC Coordinator groups can be found among the webinars offered by Whitehat Communications (https://whitehatcom.com/). San Diego State University SPH offers online POCT education with credit for nominal fees, as noted above. These resources, if tapped properly and collaboratively by public health institutions and societies, would be useful for education targeting public health issues. Extensive free instruction has been conducted over the past decade in lectures and workshops provided by one author (GK) and colleagues worldwide using the curriculum developed for limited-resource nations (9). Table 4 summarizes the topics. This experience was integrated into the recommended public health curriculum presented earlier in Table 3.

Training Center Opportunity

We suggest contacting the International Center for Point-of-Care Testing (http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/point-of-care/) (accessed January, 2019) at Flinders University in South Australia directed by Professor Mark Shephard. Center leadership has described valuable information (18–21) on their unique training program, which as far as we know, is the only one of its kind in the world producing Master and Doctor of Philosophy graduates in POCT. Although this training program focuses mainly on POC solutions to health problems in rural Australia, chapters in the recent book (11) edited by its founder, Dr. Shephard, and chapters on POC preparedness for highly infectious diseases and disasters (22, 23) fed forward to augment our knowledge bases used to design the POCT curriculum for public health (Table 3).

Limitations

The survey was web-based, so it is possible that POCT content was missed during the discovery phase, if taught, disseminated, or demonstrated in classes or electives that were not explicitly listed or investigated as search targets. Not all public health educational programs, per se (identified by “PHP” in Table 2), were included in the survey, but on the other hand, 100% of 59 U.S. schools of public health, colleges of public health, and public health schools accredited by the CEPH were accessed and assessed successfully, and 100% of the states in the U.S. with public health educational programs were represented. We focused the survey on the U.S. However, POCT has enabled national response and preparedness in developing countries and can be useful in public health institutions worldwide (10).

Conclusions

Establishing a Global Vision

Survey results identified one of the main root cause problems in the U.S., namely, accreditation requirements omit POCT. Our vision of future public health entails POCT-equipped practitioners moving to points of need with mobile diagnostic tools that will help stop outbreaks quickly, maintain isolation efficiently, and manage quarantine equitably. Mobile testing, rapid diagnosis, and rational triage will help thwart contagion arriving from abroad. Public health practice in general will benefit from well-trained personnel capable of administering POCT both in the community and primary care, and as needed, during disasters, complex emergencies, and national crises. POCT is growing exponentially on a global scale, so the public health field should embrace it to advance public health practice at points of need.

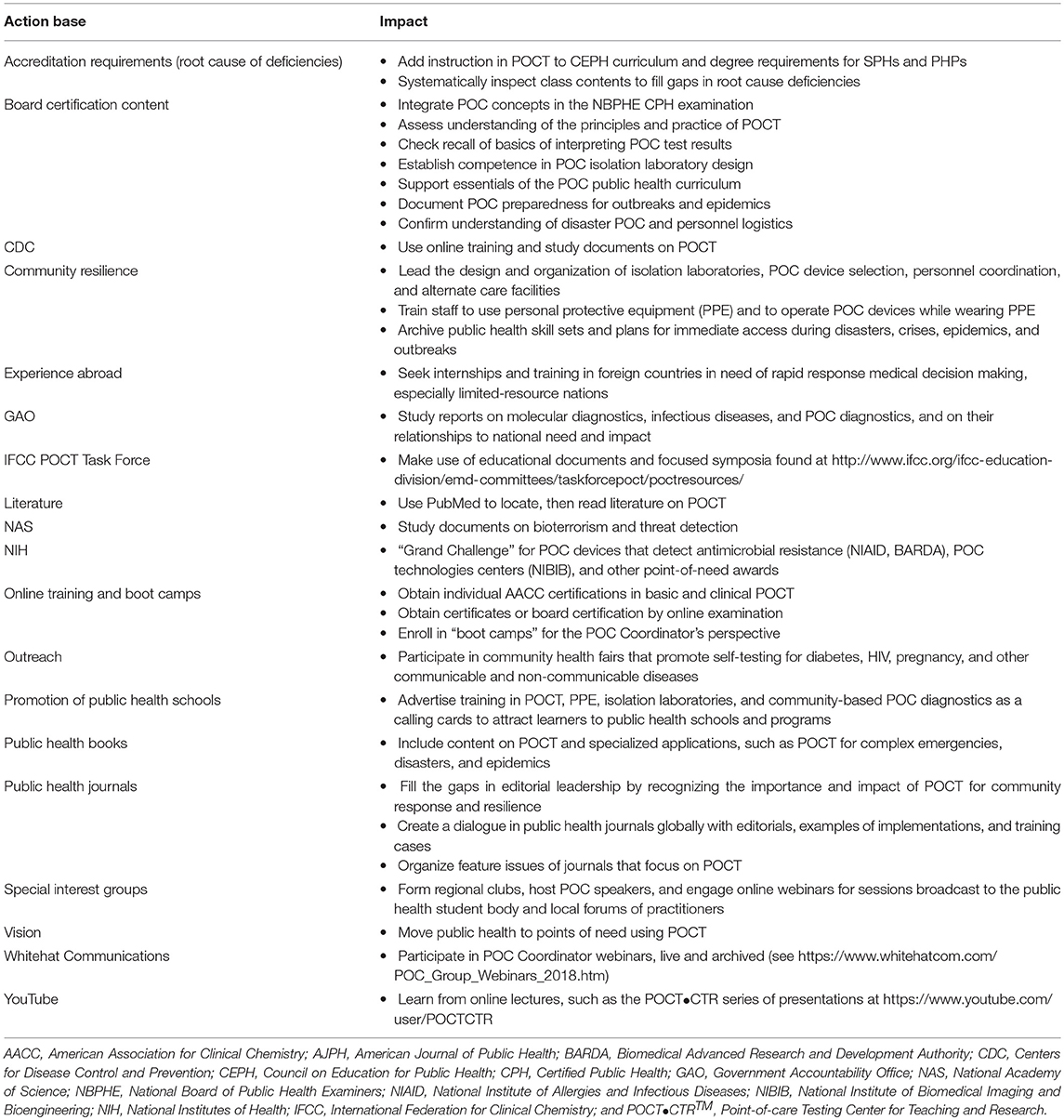

Enabling Spatial Care Paths™

Table 5 summarizes several potential pathways of future progress that embrace rapidly evolving technologies and mold POC culture (24–27). Public health practitioners who serve communities and their medical constituencies, can do so directly with POCT, rather than indirectly and slowly following unnecessarily circuitous referrals to regional laboratories. Spatial Care Paths™ (28–30) can be designed to solve specific public health problems and meet demands during infectious disease outbreaks, such as the 2018 Ebola virus disease recurrence in Central Africa.

Acting Urgently

The American Academy of Microbiologists recommends, “Ensure that public health surveillance of infectious diseases is maintained with POC testing” (31). Some, such as pathologists, have been labeled “invisible,” that is, not providing adequate leadership, when it comes to, “Modern, affordable pathology and laboratory medicine systems…essential to achieve the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals for health in low-income and middle-income countries” (32–34). Academic leaders in China see such strong need for POCT, that they and the author (GK) have proposed a new field, “Point of Careology,” with its own dedicated professional staff. Calls for action originate from urgent needs. If SPH and PHPs start now, then given the lag in attaining and matriculating MPH and PhD degrees, the public health workforce will emerge better trained in POCT, hopefully, not too late.

Public Health Implications

Benefitting From Integrated Expertise

Enhanced public health education will promote cross-talk among medical specialties and help disperse knowledge necessary for rapid response and immediate decision making, especially to prepare hard hit regions like West Africa for new outbreaks of highly infectious threats. Management of the Ebola virus disease cases that appeared in the U.S. proved unequivocally the need for POCT and trained operators familiar with professional protective equipment, isolation laboratory designs, containment protocols, and suitable POC technologies (22, 28–30). Besides remedying educational deficits, public health leadership should engage in research regarding POCT optimization for isolation, mobile facilities, and the community.

Additionally, POCT for infectious diseases represents a means for pharmacists and public health professionals to collaboratively combat antibiotic resistance and improve community health (35, 36). While in need of POC education and curricula (37), which could be adapted from Tables 3 and 4, pharmacists appear amenable to using POC tests (38), including in low- and middle-income settings (39). Future research should assess the potential for nurses, physician assistants, and other professionals to become part of POC-enabled teams.

Enhancing Accreditation and Certification Requirements

Public health leaders and the CEPH could create a consensus strategy for incremental assimilation beginning with a POCT course and accompanying hands-on workshop. National board exams are intended to protect the public from non-competency. The NBPHE should update CPH certification content consistent with future progress in education. Public health professionals could take the board certification exam possibly to be offered by the American Association for Clinical Chemistry. Becoming board certified will help produce consistent POCT performance and obviate surprising neglect of POCT evident, for example, even in a recent re-design (40) of public health school curriculum.

Improving Standards of Care

POCT-trained public health practitioners will better prepare society for crises, while also delivering diagnoses and primary treatment directly to people in need. Distributed POC knowledge will help answer calls for action in the U.S. and abroad. The technology of diagnostics is changing rapidly, supported by progress in information technology, network analysis (41), geospatial sciences (42), and molecular diagnostics (43).

Like the rapid evolution and adoption of smartphones, POCT has become ubiquitous worldwide during the past decade and will continue to expand its horizons. In fact, several modular diagnostic tests (e.g., glucose, HbA1c, and infectious diseases) are in the commercial pipeline or already appearing for implementation on smartphone platforms, with which most, if not all, public health practitioners are familiar. Smartphones provide excellent connectivity and networking options of value to communicating test results and geospatially tracking sentinel patient cases.

Two recent books, Essentials of Public Health Preparedness and Emergency Management (44) and Public Health Emergency Preparedness: A Practical Approach for the Real World (45), position public health practitioners as first responders and promote them in that key role. However, neither book includes sections on POCT, training for it, or didactic curriculum. Neither addresses related topics, such as selecting POC devices for isolators or isolation units in support of critically ill patients with highly infectious diseases, although on p. 183 of reference 45 a brief case study by C. Standley about the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Guinea lauds POCT as a technological advance that “contributed significantly” to slow contagion. Clearly, a sturdier educational bridge should constructed to connect the point of care and public health fields.

Therefore, to improve standards of care in public health, public health educational institutions in the U.S. would be well-advised to integrate and teach POCT in formal accredited curricula and share teaching experiences with other countries, especially those at risk (46) from highly infectious diseases.

Author Contributions

GK designed the research, completed Tables 1 and 2, compiled Tables 3–5, analyzed results, and wrote the paper. Three student researchers (AZ, LZ, IV) a) contributed and updated Table 1 and validated Table 2 by double checking all SPH/PHP websites, b) reviewed and helped correct the manuscript prior to publication, and c) approved it in its final form.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The senior author is grateful to the creative students who participate in the POCT•CTR and contribute substantially to knowledge in point of care. This work was supported by the Point-of-Care Testing Center for Teaching and Research™ (POCT•CTR) and by GK, its Director. Neil Gunman at PSI (https://www.psionline.com/) provided valuable information about national board certification, job analysis, competency tests, and psychometrics. We thank Joyce Arregui, Manager of Professional Education at the American Association for Clinical Chemistry (www.AACC.org), for supplying information on AACC online courses and conferences; Dr. Kem Sachaie of the Center for Educational Effectiveness at UC Davis for valuable suggestions; and Professor Ann Sakaguchi of the University of Hawaii for critiquing the paper. Tables are provided courtesy and permission of Knowledge Optimization™, Davis, California.

References

1. Kost GJ, Editor. Principles and Practice of Point-of-care Testing. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. (2002). p. 654.

2. Kuehn B. Global outbreaks threaten U.S. economy. JAMA. (2018) 319:1191. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.2595

3. Council on Education for Public Health. Accreditation Criteria–2016 revised criteria, March 16, 2018 Red Line Version. Schools of Public Health and Public Health Programs. Silver Springs, MD: CEPH (2018). p. 50. Available online at: https://ceph.org/assets/2016.Criteria.redline.3-16-18.pdf (accessed July, 2018).

4. Council on Education for Public Health. Schools of Public Health. Available online at: https://ceph.org/about/org-info/who-we-accredit/accredited/. Public Health Programs. Available online at: https://ceph.org/about/org-info/who-we-accredit/accredited/#programs. Accreditation Lists (accessed July, 2018).

5. Halverson K, Wyler LA, Skala K, Mumford J. Perfecting Point-of-Care Testing. AACC boot camp to highlight competency assessment, communications, connectivity for improved program efficiency, better outcomes. Portland, Oregon, American Association for Clinical Chemistry (2018). Available online at: https://www.aacc.org/publications/cln/cln-stat/2018/september/20/perfecting-point-of-care-testing (Accessed January, 2019).

6. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Ready? Set? Test! Patient testing is important. Get the right results. Atlanta, GA (2011). p. 56. Available online at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/clia/Resources/WaivedTests/pdf/15_255581-A_Stang_RST_Booklet_508Final.pdf and accompanying training course with Public Health 2.0 recertification credits. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/labtraining/training-courses/ready-set-test.html (accessed July, 2018).

7. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. To test or not to test? Considerations for waived testing. Atlanta, GA (2012). p. 60. Available online at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/clia/Resources/WaivedTests/pdf/15_255581-B_WaivedTestingBooklet_508%20Final.pdf (Accessed July, 2018).

8. National Board of Public Health Examiners (NBPHE, https://www.nbphe.org/). CPH Content Outline 2019. Silver Springs, MD: CEPH. (2018). p. 4. Available online at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/nbphe-wp-production/app/uploads/2017/05/ContentOutlineMay-21-2019.pdf (Accessed July, 2018).

9. Kost GJ, Delany C, Gentile NL, Longley A. Point-of-care course for limited-resource countries. A global resource: lecture, combined, interactive, and spatial modules and workshops. Davis, CA: POCT•CTR. 2011–18.

10. Kost GJ, Editor, Curtis CM, Associate Editor. Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience. Washington DC: AACC Press-Elsevier (2015). p. 702.

11. Shephard M, Editor. A Practical Guide to Global Point-of-care Testing. Australia: CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) (2016). p. 471.

12. The Point of Care Testing Steering Committee. National Point of Care Testing Policy and Guidelines. Putrajaya: Ministry of Health Malaysia Medical Development Division (2012). p. 57. Available online at: http://moh.gov.my/images/gallery/Garispanduan/National_Point_of_Care_Testing.pdf (accessed July, 2018)

13. Ministry of Public Health. Thailand's National Guidelines for Point-of-care Testing (POCT). Bangkok: MOPH (2015). p. 50. Available online at: http://blqs.dmsc.moph.go.th/assets/Userfile/POCTguideline.pdf. (Accessed January, 2019).

14. Mavenyengwa RT, Nyamayaro T. Developing a curriculum for health professional students on point of care testing for medical diagnosis. Int J Med Educ. (2016) 7:265–6. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5780.a9cd

15. Liikanen E, Lehto L. Training of nurses in point-of-care testing: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. (2013) 22:2244–52. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12235

16. Lerner V, Mcvoy L, Aguero-Rosenfeld M, Rapkiewicz A, Winkel A. Clinical laboratory medicine—understanding point-of-care testing and provider-performed microscopy in clinical practice: case-based curriculum for OBGYN and pathology residents. MedEdPORTAL (2015) 11:10109.doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10109

17. Knapp H, Chan K, Anaya HD, Goetz MB. Interactive internet-based clinical education: an efficient and cost-savings approach to point-of-care test training. Telemed J E Health. (2011) 5:335–40. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0187

18. Shephard MDS, Mazzachi BC, Shephard AK, Burgoyne T, Dufek A, Kit JA, et al. Point-of-care testing in Aboriginal hands—a model for chronic disease prevention and management in indigenous Australia. Point Care (2006) 5:168–76. doi: 10.1097/01.poc.0000243983.38385.9b

19. Shephard M, Halls H, Motta L. New postgraduate academic qualification for point-of-care coordinators. Point Care (2012) 11:173–5. doi: 10.1097/POC.0b013e318265e6fe

20. Shephard DSM, Halls HJ, Motta LA. Chapter 30 Online point-of-care coordinator graduate certificate program for global point-of-care testing. In: Kost GJ, Curtis CM, editors. Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience. Washington, DC: AACC Press-Elsevier (2015). p. 341–6.

21. Shephard MDS, Spaeth B, Motta LA, Shephard A. Chapter 48 Point-of-care testing in Australia: Practical advantages and benefits of community resilience for improving outcomes. In: Kost GJ, Curtis CM, editors. Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience. Washington DC: AACC Press-Elsevier (2015). p. 3527–35.

22. Kost GJ. Point-of-care testing for Ebola and other highly infectious threats: principles, practice, and strategies for stopping outbreaks. In: Shephard M, editor. A Practical Guide to Global Point-of-care Testing. Australia: CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) (2016). p. 291–305.

23. Shephard M, Arbon P, Kost GJ. Chapter 31 Point-of-care testing for disaster management. In: Shephard M, editor. A Practical Guide to Global Point-of-care Testing. Australia. CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) (2016). p. 378–92.

24. Kost GJ, Ferguson WJ, Kost LE. Principles of point of care culture, the spatial care path, and enabling community and global resilience. e-JIFCC (2014) 25:134–53.

25. Kost GJ, Ferguson WJ. Spatial Care Paths™ strengthen links in the chain of global resilience: Disaster caches, prediabetes, Ebola virus disease, and the future of point of care. Point Care (2015) 15:43–58. doi: 10.1097/POC.0000000000000080

26. Kost GJ, Zhou Y, Katip P. Chapter 43 Understanding of point-of-care culture improves resilience and standards of care in limited-resource countries. In: Kost GJ, Curtis CM, editors. Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience. Washington, DC: AACC Press-Elsevier (2015). p. 471–90.

27. Kost GJ, Zhou Y, Katip P. Point of care culture survey Appendix 3. In: Kost GJ, Curtis CM, editors. Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience. Washington DC: AACC Press-Elsevier (2015). p. 663–82.

28. Kost GJ, Ferguson WJ, Truong A-T, Prom D, Hoe J, Banpavichit A, et al. The ebola spatial care path™: lessons learned from stopping outbreaks. Clin Lab International. (2015) 39:6–14. Available online at: https://www.clinlabint.com/fileadmin/user_upload/3._CLI_June_2015_FINAL.pdf (Accessed January, 2019).

29. Kost GJ, Ferguson W, Truong AT, Hoe J, Prom D, Banpavichit A, et al. Molecular detection and point-of-care testing in Ebola virus disease and other threats: a new global public health framework to stop outbreaks. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. (2015) 15:1245–59. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1079776

30. Kost GJ, Ferguson WJ, Hoe J, Truong AT, Banpavichit A, Kongpila S. The Ebola Spatial Care Path: Accelerating point-of-care diagnosis, decision making, and community resilience in outbreaks. Amer J Disaster Medicine. (2015) 10:121–43. doi: 10.5055/ajdm.2015.0196

31. American Academy of Microbiology,. Changing Diagnostic Paradigms for Microbiology. Washington DC: AAM (2017). p. 28. Available online at: https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/Changing_Diagnostic_Paradigms_for_Microbiology.pdf (Accessed January, 2019).

32. Wilson ML, Fleming KA, Kuti MA, Looi LM, Lago N, Ru K. Access to pathology and laboratory medicine services: a crucial gap. Pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries 1. Lancet (2018) 391:1927–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30458-6

33. Sayed S, Cherniak W, Lawler M, Tan SY, Sadr WE, Wolf N, et al. Improving pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries: roadmap to solutions. Pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries 2. Lancet. (2018) 391:1939–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30459-8

34. Horton S, Sullivan R, Flanigan J, Fleming KA, Kuti MA, Looi LM, et al. Delivering modern, high-quality, affordable pathology and laboratory medicine to low-income and middle-income countries: a call to action. Pathology and laboratory medicine in low-income and middle-income countries 3. Lancet. (2018) 391:1953–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30460-4

35. Gubbins PO, Klepser ME, Adams AJ, Jacobs DM, Percival KM, Tallman GB. Potential for pharmacy-public health collaborations using pharmacy-based point-of-care testing services for infectious diseases. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2017) 23:593–600. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000482

36. Bishop C, Yacoob Z, Knobloch MJ, Safdar N. Community pharmacy interventions to improve antibiotic stewardship and implications for pharmacy education: a narrative overview. Res Social Adm Pharm. (2018). [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.09.017

37. Kehrer JP, James DE. The role of pharmacists and pharmacy education in point-of-care testing. Am J Pharm Educ. (2016) 80:129. doi: 10.5688/ajpe808129

38. Casserlie LM, Mager NA. Pharmacists' perceptions of advancing public health priorities through medication therapy management. Pharm Pract (Granada) (2016) 14:792. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2016.03.792

39. Saldarriaga EM, Vodicka E, La Rosa S, Valderrama M, Garcia PJ. Point-of-care testing for anemia, diabetes, and hypertension: a pharmacy-based model in Lima, Peru. Ann Glob Health (2017) 83:394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.03.514

40. Begg MD, Fried LP, Glover JW, Delva M, Wiggin M, Hooper L, et al. Columbia public heath core curriculum: short-term impact. Amer J Public Health (2015) 105:7–13. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302879

41. Kost GJ. Chapter 49 Using small-world networks to optimize preparedness, response, and resilience. In: Kost GJ, Curtis CM, editors. Global Point of Care: Strategies for Disasters, Emergencies, and Public Health Resilience. Washington, DC: AACC Press-Elsevier (2015). p. 539–68.

42. Ferguson WJ, Kemp K, Kost G. Using a geographic information system to enhance patient access to point-of-care diagnostics in a limited resource setting. Int J Health Geogr. (2016) 15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12942-016-0037-9

43. Kost GJ. Molecular and point-of-care diagnostics for ebola and new threats: national POCT policy and guidelines will stop epidemics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. (2018) 18:657–673. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2018.1491793

44. Katz R, Banaski JA. Essentials of Public Health Preparedness and Management. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning (2019). p. 210.

45. McKinney S, Papke ME. Public Health Emergency Preparedness: A Practical Approach for the Real World. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning (2019). p. 195.

Keywords: point-of-care testing, curriculum, accreditation, public health, preparedness, standards of care, points of need, epidemic

Citation: Kost GJ, Zadran A, Zadran L and Ventura I (2019) Point-Of-Care Testing Curriculum and Accreditation for Public Health—Enabling Preparedness, Response, and Higher Standards of Care at Points of Need. Front. Public Health 6:385. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00385

Received: 03 July 2018; Accepted: 24 December 2018;

Published: 29 January 2019.

Edited by:

Will R. Ross, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, United StatesReviewed by:

Allison Mari Dering-Anderson, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United StatesPradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, India

Copyright © 2019 Kost, Zadran, Zadran and Ventura. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gerald J. Kost, Z2prb3N0QHVjZGF2aXMuZWR1

Gerald J. Kost

Gerald J. Kost A. Zadran

A. Zadran