- 1The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health, Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, Houston, TX, United States

- 2The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Infectious Disease, Infection Control, and Employee Health, Houston, TX, United States

Introduction: Despite the continuous increase in the incidence of metastatic breast cancer among Syrian and Iraqi refugee women residing in camp settings in Lebanon, mammography and chemotherapy adherence rates remain low due to multiple social, economic, and environmental interfering factors. This in turn led to an alarming increase in breast cancer morbidity and mortality rates among the disadvantaged population.

Methods: Intervention mapping, a systematic approach which guides researchers and public health experts in the development of comprehensive evidence-based interventions (EBIs) was used to plan a health education and health policy intervention to increase breast cancer screening and chemotherapy adherence among Iraqi and Syrian refugee women aged 30 and older who are residing in refugee camps within the Beirut district of Lebanon.

Results: The generation of the logic model during the needs assessment phase was guided by an extensive review of the literature and reports published in peer-reviewed journals or by international/local organizations in the country to determine breast cancer incidence and mortality rates among refugee women of Syrian and Iraqi nationalities. The underlying behavioral and environmental determinants of the disease were identified from qualitative and quantitative studies carried out among the target population and also aided in assessing the sub-behaviors related to the determinants of breast cancer screening and chemotherapy completion as well as factors affecting policy execution to formulate performance objectives. We then developed matrices of change objectives and their respective methods and practical applications for behavior change at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, and societal levels. Both educational components (brochures, flyers) and technological methods (videos disseminated via Whats app and Facebook) will be adopted to apply the different methods selected (modeling, self-reevaluation, consciousness raising, persuasion, and tailoring). We also described the development of the educational and technological tools, in addition to providing future implementers with methods for pre-testing and pilot-testing of individual and environmental prototype components.

Conclusion: The use of intervention mapping in the planning and implementation of holistic health promotion interventions based on information collected from published literature, case reports, and theory can integrate the multiple disciplines of public health to attain the desired behavioral change.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer diagnosed in women globally, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death among females (1, 2). This health concern significantly affects vulnerable populations, particularly refugees, who fled their war-torn countries in search of a safer and healthier life (1). The Middle-Eastern region is currently suffering from the highest rates of breast cancer, especially in countries like Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, which are reported to be the three main host-communities for Syrian refugees, following the 8-year war in Syria that was fueled by the Arab Spring (1, 3, 4). It is estimated that approximately 72% of cancer deaths occur annually in low- and middle- income countries (1, 3, 5). Around 200,000 breast cancer fatalities were recorded in 2015 among Syrian refugees residing in host communities. The high mortality rate was mainly attributed to the lack of effective, affordable, and accessible preventive (screening, clinical diagnosis) and treatment (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, medications) measures (1). In 2018, Lebanon was ranked first among the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region for having the largest influx of Syrian refugees in proportion with its overall national population, 183 refugees per 1,000 Lebanese citizens (3). A report released by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health in 2016 to investigate the impact of refugees from Syria and Iraq on breast cancer incidence rates in Lebanon highlighted an increase of 37.6% in the number of annually reported breast cancer cases. Moreover, in 2015, 41% of patients with breast cancer diagnosed and treated at the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) were Iraqi and Syrian refugees, of whom 24% had metastatic cancer (3). These results represent an increase of 2,821 new cases of breast cancer in Lebanon by 2015 compared to 1,758 cases in 2008. Based on 2015 data from the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health and the AUBMC's database registry, of the total 628 cases treated at AUBMC, 372 were Lebanese and 213 were Iraqi refugees. Over one quarter (28%) of the Lebanese female cases were detected through mammography and 15.3% were metastatic cases at diagnosis. However, among Iraqi refugees, only 4% were screen detected, and 24.4% were diagnosed at stage IV breast cancer (6).

A combination of personal determinants such as low self-efficacy, low knowledge, high perceived barriers, and low perceived susceptibility; and environmental factors such as low awareness of physicians regarding the severity of metastatic breast cancer among refugee women, lack of health literate and culturally competent educational skills, and issues related to the local healthcare system (unavailability of funding for chronic disease screening and treatment for refugees, high costs of medical services, lack of properly educated nurses, and lack of transportation means from camps to hospitals) have been negatively affecting screening and chemotherapy completion rates among the target population (1, 3, 7–16). Aside from the lack of funding allocated by the main refugee organization in the country, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the absence of human right policies at the societal level to protect the integrity of refugees and ensure the equitable receival of urgent medical care by disadvantaged populations amidst prevailing political corruption has worsened mammography and treatment rates by contributing to the stigma associated with e refugee status in the host community (17, 18).

The most salient and changeable personal determinants that adversely affect reported screening and chemotherapy adherence estimates among Syrian and Iraqi refugee women in Lebanon encompass the following: low self-efficacy to perform mammography and complete recommended chemotherapy treatment due to social and religious barriers, lack of knowledge about susceptibility to disease, and high perceived barriers including financial and communication issues with physicians in host communities (7, 8, 10, 15, 16).

In 2006, the Breast Health Global Initiative (BHGI) developed and published resource-stratified breast cancer guidelines to address the quality of care received by breast cancer patients in low and mid-resource countries. Several levels are addressed through these guidelines including awareness and education, prevention, early detection and treatment, and overall healthcare systems and public policy with the goal of aiding countries in the better effective utilization of available resources while working on ameliorating other lacking resources, infrastructure, and human capabilities. These guidelines identified four distinct levels of resource availability (basic, limited, enhanced, maximal), each of which have a cumulative set of recommendations that take into account the nature of the country's regulatory environment, the cancer care workforce, and other intervening societal factors (19, 20). Subsequently, in 2016, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) launched a program that incorporates the BHGI resource stratification guidelines and released the NCCN framework for resource stratification which includes updated definitions for each resource level (3). Despite the availability of internationally recognized resource-stratified guidelines, and the continuous advocacy efforts of global health experts to allocate the needed resources based on these guidelines to provide cancer care for patients in low-income and war zone countries, rarely any interventions have been implemented to address this alarming health issue.

Interventions of this kind are specifically recommended in the Middle East, where the influx of refugees and the ongoing financial crisis have debilitated the healthcare system in host communities at a national and regional scale (1, 3, 19). This article describes the application of Intervention Mapping (IM), a systematic theory- and evidenced approach to health promotion planning, to develop a breast cancer screening education and chemotherapy adherence policy program to promote mammography acceptability and treatment completion among Syrian and Iraqi refugee women residing in camps located in the Beirut district of Lebanon. The intervention focuses on the basic and limited levels of the BHGI framework. The effort was carried out in collaboration with Health Promotion professionals from the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health and Lebanese physician experts who are knowledgeable about the overall health situation of refugees in the country.

Methods

Intervention Mapping

IM is a systematic approach to develop and implement theory- and evidence-based health promotion interventions to tackle health issues from an ecological perspective (20). The IM protocol defines the six steps of IM starting from problem identification to solution generation and implementation. Each step incorporates several tasks that need to be completed to create a product that guides implementation of the subsequent step. Even though all six steps are interlinked, IM is an iterative rather than a linear approach, providing program planners with the opportunity to move back and forth between tasks and steps to make necessary corrections as new knowledge and perspective are gained throughout the ongoing evaluation process. Yet, the process is still considered cumulative, since inattention to the progress of one step can jeopardize the effectiveness and compromise the validity of the entire intervention (21). Many breast cancer screening programs targeting low-income populations in the United States have successfully used IM to guide the different steps of intervention development and implementation (22–25). In this article, we describe the first four steps of the IM process (needs assessment; performance and change objectives; program design; and program production). The PRECEDE model adapted in IM is a comprehensive structure used to evaluate health needs for the purpose of guiding the design and implementation of effective and focused public health programs. It involves the assessment of several community factors including social determinants, epidemiological determinants, as well as behavioral and environmental determinants, which will be carried out throughout the first four steps of intervention mapping (26). In step 1, the PRECEDE model was applied to conduct a comprehensive needs assessment. This step will be based on a review of previous literature and case reports highlighting the emerging need for cancer prevention and treatment measures among refugees in Lebanon. In step 2, the overall behavioral and environmental goals were highlighted, and matrices were developed to combine the health-promoting behaviors, the environmental policy-related factors, and their respective determinants to generate change objectives. During step 3, theory-based behavioral and environmental change methods were selected based on the change objectives to influence the chosen determinants. Finally, we proposed a plan to pre-test the program in step 4.

Theoretical Underpinnings

To focus on the major risk behaviors and environmental barriers influencing the adoption of the health-promoting behavior, the Integrated Behavioral Model constructs were used which encompasses constructs from the most frequently used theories (Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Cognitive Theory, and Health Belief Model) such as: perceived severity, perceived susceptibility, self-efficacy, skills, perceived barriers, and outcome expectations (27). By taking into account these constructs, a better understanding of the determinants related to screening and chemotherapy was established, which in turn enabled a careful selection of theory-based methods to achieve behavioral and environmental change (27).

Results

IM Step 1: Needs Assessment

Recent literature published in 2017 show that the 72% of cancer deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries can be attributed to late diagnosis of the chronic disease followed by the availability of affordable low-quality treatment rather than optimal treatment. In 2015, an estimated 200,000 Syrian refugee cancer patients were reported dead due to deficiencies in first-line treatment and the lack of a sufficient number of specialized physicians in both host countries (Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey) and the countries of origin (Syria and Iraq), which resulted in a loss of therapeutic and survival benefits (1). Recipient countries are not offering refugees residing in camp settings with the basic medical services they are in dire need of as a result of the political unrest and the financial crisis ruling over the region (1, 3, 28). Moreover, UNHCR has no budget guidelines for chronic disease management and treatment as compared to the funds allocated to the control of infectious diseases in unsanitary camp settings (1, 3, 6, 29). Therefore, we focused the intervention on reaching this specific target population (Syrian and Iraqi refugee women residing in Beirut refugee camps in Lebanon) through a collaboration with the main health agents and health institutions in the country who will be part of the planning group.

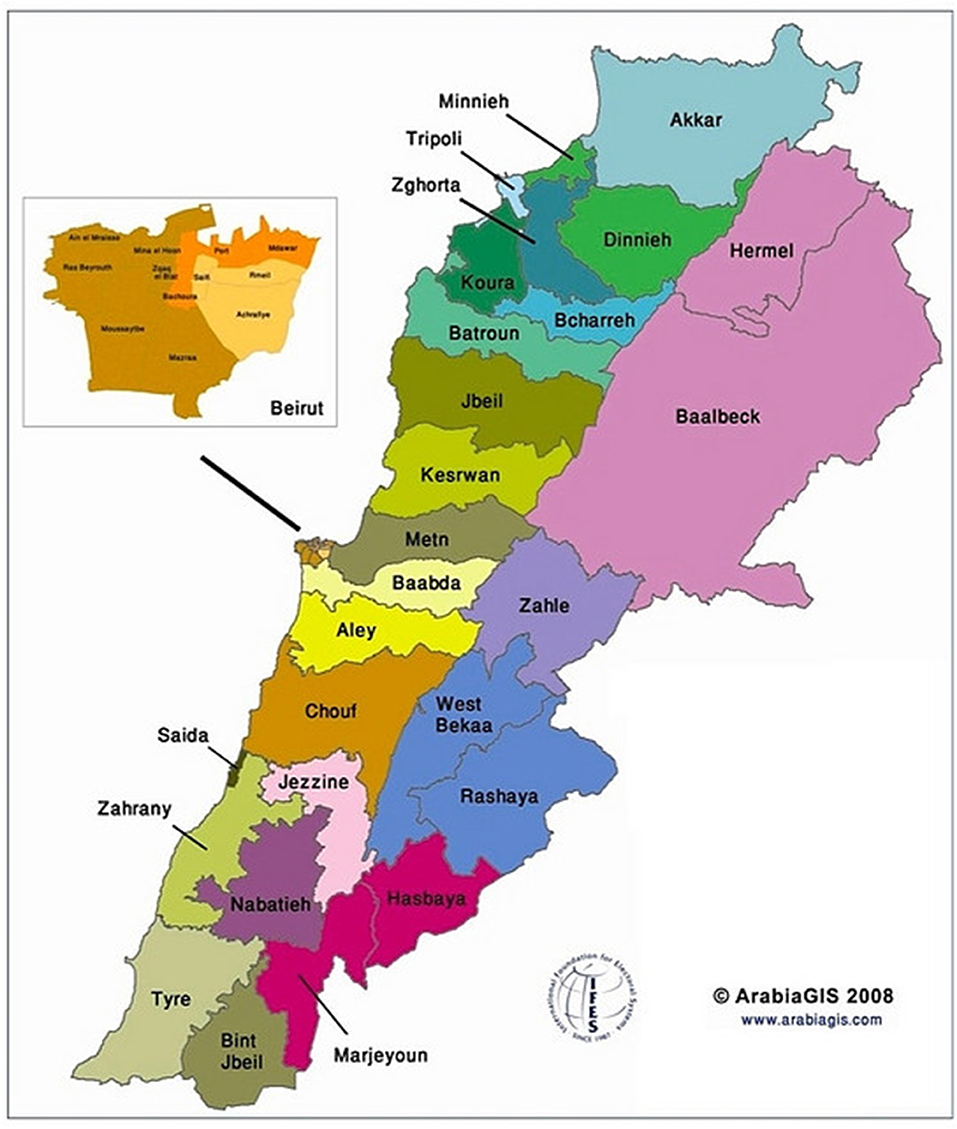

An estimated 338,915 of Syrian refugees in Lebanon reside in refugee camps located in the Beqaa governorate of the country compared to a total of 249,110 Syrian refugees who are living in the Beirut district camps. Around 6,100 Iraqi refugees were reported to be dispersed across these two regions of Lebanon (30–32). The Beirut Governorate encompasses only one district, the city of Beirut; therefore, for the sake of Beirut, the terms “governorate” and “district” can be used interchangeably. As for Beqaa, the governorate incorporates three different districts: Zahle, Rashaya, and West Beqaa, and one of the UNHCR local offices is situated in Zahle. The Zahle district is considered a focal point for data collection purposes (32–34) (Figure 1). In terms of geography, the distance between the Beqaa and Beirut governorates is 39.99 miles (64.36 km), which takes approximately an hour and 5 min to travel from one district to another (35). In 2018, UNHCR disclosed in its response plan for the Lebanese crisis for the time period 2017–2020 that displaced Syrians in Akkar, Baalbek, and Beqaa suffer mostly from economic, social, and health-related barriers, where four out of five individuals fail to satisfy their daily basic needs (32, 36). The Primary Health Care Center (PHC) distribution rate in Beqaa is 6% in contrast to 10% in Beirut, while two public hospitals are available in each of the governorates (37, 38). The reason behind the selection of Beirut governorate as the location for the implementation of the intervention is the greater availability of PHCs and the high allocation of funds to the Rafic Hariri University Hospital, one of the two public hospitals in the area, which renders this medical institution as a main establishment for the receival of medical services among Lebanese citizens and Syrian refugees (39). Moreover, the Beirut governorate includes a single city compared to the three districts in Beqaa, which makes it logistically easier to carry out the intervention in terms of accessing the refugees (localized in one district rather than three) (34). Following the expected success of the intervention, we project a greater dissemination of the project to the remaining refugee camp settings in Lebanon.

Diverse stakeholders will be part of the planning group to ensure a representative sample of the eclectic political, health, social, religious, and economic sectors related to the health problem. Program developers and funders consist of health professionals (oncologist, radiologist, psychologist, behavioral scientists, epidemiologists), translators, interpreters, and community leaders, who will aid in planning and implementing the different tasks leading to an effective health intervention that targets breast cancer while integrating all social, religious, cultural, communication, and behavioral aspects in program design and delivery. Potential sponsors include medical equipment (new available screening technologies) and pharmaceutical companies (chemotherapy drugs); therefore, representatives from such corporations will also be members of the planning group. Lebanon is a highly politicized country, which renders the inclusion and involvement of diverse governmental sectors a necessity for the long-term success of the proposed program. Various governmental departments (Ministry of Public Health, Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Higher Education, & Ministry of Public Works and Transport) are in direct competition for funding measures due to financial and resource constraints that are associated with religious and political issues in the country (40). Hence, collaboration across departments must be secured to ensure effective management of funds to develop and implement a new health promotion intervention that can be maintained over time to satisfy the rising needs of disadvantaged population groups within the Lebanese society (41). Local institutions (American University of Beirut-Global Health Institute and the Lebanese Breast Cancer Foundation) who are known to be active planners and implementers of national health-related campaigns can act as both sponsors and developers. Sponsorships and grants are expected to be provided by the multiple sponsors to aid MOPH and the designated UNHCR departments in policy execution both before and after the policy is officially implemented since the legal and political structure of the intervention is crucial for its long-term sustainability. In case the policy execution takes longer than expected, other local and international institutions will be asked to contribute financially to ensure the long-term sustainability of the intervention. The team of health professionals (physicians, public health workers, and nurses) who will be carrying out the intervention, will collaborate and coordinate efforts with the board of directors of public hospitals and primary healthcare centers since the main program objectives involve the assurance of affordable, accessible, and quality screening measures (mammography) along with subsidized treatment (chemotherapy and medications) which will be available for refugee women in these public healthcare establishments. Finally, refugee women representatives, who have successfully battled breast cancer, are suffering from breast cancer, and who are not impacted by breast cancer, will be involved as part of the planning group since their perspectives and opinions are invaluable to the success of the program.

Since limited empirical data is available on Syrian and Iraqi refugee having breast cancer in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, a thorough and extensive review of case reports, theoretical literature, and firsthand data was carried out to identify the main factors prohibiting the target population from screening and proper chemotherapy treatment. The database search was guided by the previously mentioned constructs of the Integrated Behavioral Model to determine behavioral and environmental determinants for change.

Personal Determinants and Environmental Factors From Descriptive and Experimental Studies

In 2011, Saadi et al. carried out a qualitative study among a group of Iraqi refugee women who have immigrated to the United States to examine their perspectives on preventive care and their perceived barriers to breast cancer screening. At the personal level, the main emerging themes included: reliance on God to prevent illness; preventing disease as a function of nutrition and cleanliness not doctors; fear of pain during mammography; and fear of receiving a cancer diagnosis. On the other hand, the environmental level included accessibility (testing centers far away), quality (low-quality care in war-zone countries), and availability (limited number of physicians to provide needed care) problems (42). Being part of the Muslim religion and having extremely conservative beliefs were also noted as a barrier since mammography is regarded as inappropriate because prevention efforts are considered anti- fatalism or acting against “God's will” (15, 40). A more recent descriptive cross-sectional study carried out by Al Qadire et al. (7) among Syrian refugee women in Jordan used the Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) as a tool to look at awareness of cancer symptoms, anticipated delay, and barriers to seeking help. The main reported concerns at the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels were the lack of awareness about cancer symptoms; low knowledge about cancer risk factors; fear of the unknown; worrying about what the doctor might say; being too scared or embarrassed; and difficulty talking to the doctor or wasting his time. Other major environmental factors include the lack of insurance coverage to cover the cost of medical care; safety concerns; and settlement difficulties (7). To address these recurring themes and issues prohibiting effective access to quality breast cancer screening and chemotherapy, some interventions have been carried out in developed and developing countries to look at the impact of education on behavior change. In New York City, a single session education program delivered through a mobile mammography unit targeting immigrant and refugee women in the area led to significant improvements in breast cancer knowledge and mammography completion. The study highlighted the importance of designing such programs in community-based settings to show social support as well as the need to have health literate and culturally competent interpreters as part of the team to ensure an accurate and successful communication process (8). Another quasi-experimental study based on the Health Belief Model was implemented in Iran to look at the effect of education on the behavior of breast cancer screening in women. The pre- and post-tests administered in the form of a researcher-made questionnaire three months before and after four teaching sessions showed remarkable improvements in knowledge, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and cues to action (10). Both descriptive and experimental studies showed consistency in personal and environmental determinants. The identified determinants will be targeted in the following intervention plan at four different levels of the socioecological model: intrapersonal (refugee women); interpersonal (physicians), organizational (UNHCR), and societal (UNHCR & MOPH).

Delivery Vehicle Preferences for Educational Intervention Components based on Usability of Technological Devices Among Syrian Refugees

Shioiri-Clark (43), a design innovation manager for the International Rescue Committee (IRC), shared her experience when trying to develop an application to promote healthy child development among Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. Nearly every household in camps had access to at least one smartphone since it is the only communication method refugees are able to use to contact their family members in Syria (33). However, when the IRC team tried to deliver digital health-promoting activities and messages through Whats app, Facebook, and an Android mobile application that Syrian refugee parents had to download, only the former two methods were effective. When pilot testing the app, it was seen that many parents only used their phones to satisfy specific functions. They had no interest in downloading an app to use for one particular purpose and that would take time for them to learn how to successfully navigate. The majority of Syrian refugees used their phones for phone calls or for news updates via Facebook. Moreover, one of the barriers to focusing the intervention on an app was the low literacy level of the targeted parents. However, when health promoting videos teaching parents how to carry out activities to improve their children's health status were uploaded on Whats app groups and Facebook, parents were really excited to carry out the activities since they connected with other refugees featured in the video and were also themselves featured in future videos to share their own success stories. An additional positive outcome resulting from this intervention was the new connections formed between different households as they all supported each other to improve their children's health (43). One of the main components that will be used to deliver health messages to refugee women and their families is an awareness and action-oriented video. The delivery vehicles for this video are the two mobile applications “Whats app” and “Facebook” rather than TVs or radios since satellite connection might be limited in camps (further information in step 4).

IM Step 2: Program Objectives

After conducting the needs assessment based on a thorough review of the literature, the overall behavioral outcome was defined as “Syrian and Iraqi refugee women residing in camps located in Beirut, Lebanon will perform a mammogram once a year if aged between 30 and 55 and once every 2 years if aged 55 and above. The age range mentioned is different than that set by the American Cancer Society (annual mammograms for women aged between 40 and 54 and biennial mammograms for women aged 55 and above) since the age standardized incidence rate for breast cancer at diagnosis among Arab women in the MENA region (usually 27–30 years old and above) was one fourth to one third that of Western women (44). Hence, screening at an earlier age for breast cancer is recommended in Lebanon (45). Mammography plays a crucial role in decreasing metastatic breast cancer incidence and prevalence rates by detecting the disease at an earlier and less advanced stage compared to clinical diagnosis. For instance, the study carried out by Ekeh et al. (46) showed that low-income patients were more likely to respond positively to treatment when diagnosed with stage II carcinoma by a mammography evaluation compared to individuals whose breast cancer was detected clinically at a more aggressive stage of the disease. Furthermore, increased uptake of mammography was identified as the underlying reason for the improved cancer-related morbidity and mortality rates reported in the U.S over the past two decades. This assumption was further supported by the American Cancer Society, which highlighted a 34% decrease in breast cancer death rates between 1990 and 2010 due to the widespread availability of screening measures across the country (47). One of the main performance objectives was having Syrian and Iraqi refugee women in Lebanon perform self-examination for early detection of nodules starting at age 25. The fulfillment of suitable self-examination procedures can contribute to the early detection of the disease. Over 40% of verified breast cancer cases were detected by the patient primarily after reporting to their physician that a lump or nodule was forming in their upper chest in either both or one of their breasts (48). This behavioral outcome is also related to the BHGI resource stratification guidelines which integrate awareness, breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), and mammography as primary modalities for the early diagnosis of the disease in low-income countries. Increasing knowledge among the target population along with BSE and CBE measures can reduce the burden of late stage breast cancer detection (3, 20).

As for the primary environmental outcome, it aims to increase UNHCR support for refugee women to receive early detection (screening and self-examination) and treatment (chemotherapy, radiology) measures (organizational level). Refugee women are constantly struggling to access quality treatment at an affordable rate, especially those residing in camps located in developing countries such as Lebanon, since these nations themselves are incapable of meeting the healthcare needs of their own citizens. El Saghir et al. (3) reported that the UNHCR office in Lebanon is facing an 83% deficit in funds, particularly in financial and monetary aid allocated to the provision of medical services to refugees. Furthermore, (49) highlighted that restricted access to preventive services due to high medical expenditures, lack of insurance, and poor infrastructure contributed to worsening breast and cervical cancer screening rates in 15 developing countries. Therefore, the assistance of UNHCR through resource-stratified guidelines could aid in decreasing the alarming metastatic breast cancer incidence rates among refugee populations in third world countries. Access to subsidized or free screening procedures in health maintenance organizations and primary healthcare centers increased willingness and conformance to screening recommendations among low-income women compared to those who did not obtain similar advantages and financial help (50).

The secondary environmental outcome will enhance physicians' communication skills with refugee women to emphasize the importance of screening and recommend affordable treatment measures (interpersonal level). A physician-patient relationship that is trustworthy and respectful in nature is a valuable asset in decreasing metastatic breast cancer cases since it enhances the willingness of the targeted population group to regard their doctors as reliable sources of information and conform to the recommended health-actions. Therefore, if the physician allocates only limited time for the purpose of explaining the crucial necessity to conform to the recommended preventive and treatment measures using lay terms or emphasizing the importance of completing the chemotherapy treatment if diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, vulnerable populations are not likely to perform their annual/biannual mammography and adhere to their prescribed treatments as depicted by international guidelines. Physicians should accommodate their explanation based on the educational level of the refugee women since some women can hold a university degree while others dropped out of school at an earlier age. A study carried out by Ekeh et al. (12) showed that among 625 low-income females in Jordan who had access to free mammography vouchers after successfully participating in home-based breast cancer awareness sessions led by health literate and culturally competent health experts, 73% were reported to seek screening services, mainly mammography, in nearby primary health centers. Knowledge about the vitality of screening and self-examination in enhancing treatment and recovery options was seen to improve significantly as a result of the fulfillment of sequential awareness and communication sessions between the target population and the team of health professionals. Follow-up visits increased compliance to the recommended prevention measures (12). El Saghir et al. (19) emphasized the importance of the role of the primary care providers in responding to the healthcare burden brought upon an increasing cancer population in low- and middle-income countries. By developing training curricula in cancer etiology, prevention, and early detection, along with improving communication skills with the disadvantaged population, increased effectiveness of care provided to the patients will be attained (19).

The tertiary environmental outcome will entail a collaboration between UNHCR and the Lebanese MOPH to work on formulating a policy to subsidize by 75% chemotherapy fees for refugee women in dire need of treatment. According to the basic and limited levels of the BHGI guidelines, preoperative chemotherapy with AC (Adriamycin and Cytoxan), EC (Epirubicin and cyclophosphamide), FAC (fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide) or CMF (cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil) should be offered to breast cancer patients in low-resource settings with a minimum of 75% reach and a target of 90% (3, 20). However, the lack of policies in the country to protect the basic human rights of refugees such as accessing healthcare services at a reasonable price in the country's medical establishments renders it nearly impossible to treat chronic diseases such as breast cancer (17, 18). Therefore, the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health should join efforts with UNHCR and advocate for the implementation of a policy which increases the allocation of funds for breast cancer chemotherapy that should be mainly provided by the Ministry which acts as the primary healthcare reference for the target population (50% of funds) and supplemented by the international agency (25% of funds). This will allow the UNHCR to focus on diverse health and social issues affecting the refugee population in Lebanon. According to a global policy analysis of resource-stratified metastatic breast cancer policy development conducted across 16 countries having diverse geographic areas, socioeconomic statuses, and healthcare systems, the implementation of policies was successful in the adoption of national cancer control programs for metastatic breast cancer. However, gaps including absence of specialized physicians, inadequate public awareness, lack of efficient care delivery, and limited accessibility to required treatment highlight the need for advocacy efforts and promising models to support policy adoption and widespread adaptation across the key health sectors in these countries. Holistic interventions are needed that tackle several levels of the socioecological model at once to ensure long-term sustainability of programs (51).

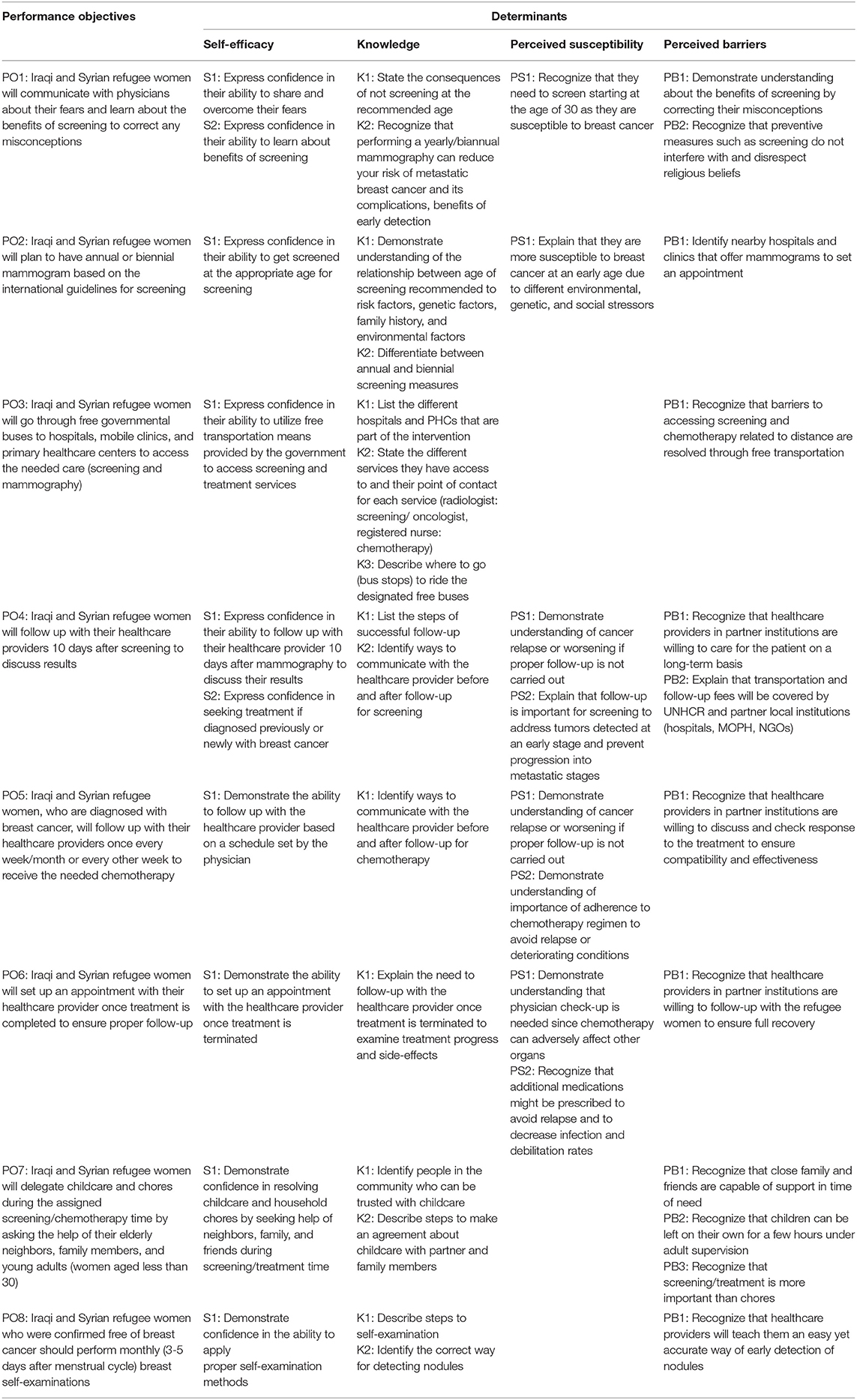

Performance Objectives and Change Objectives

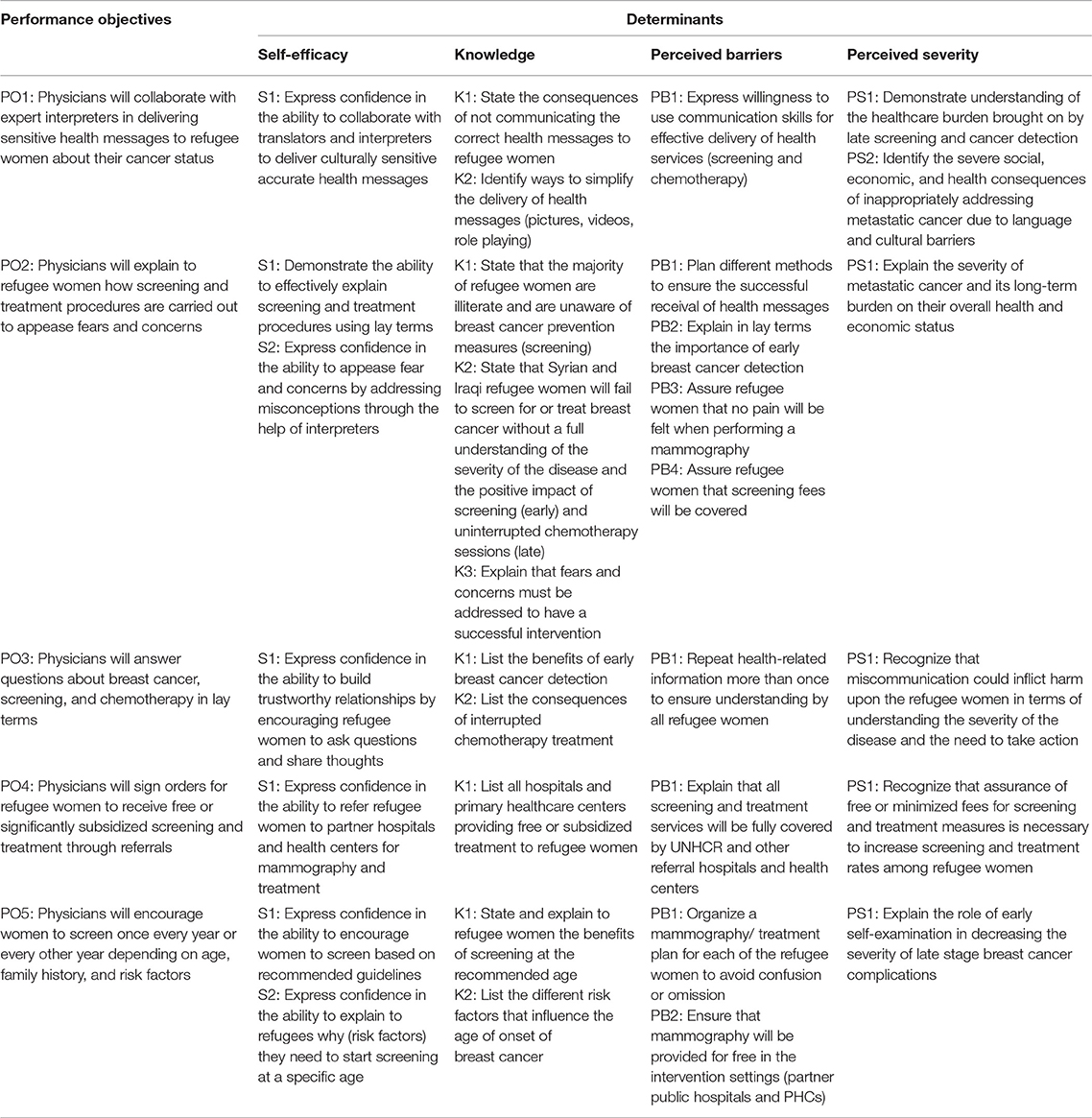

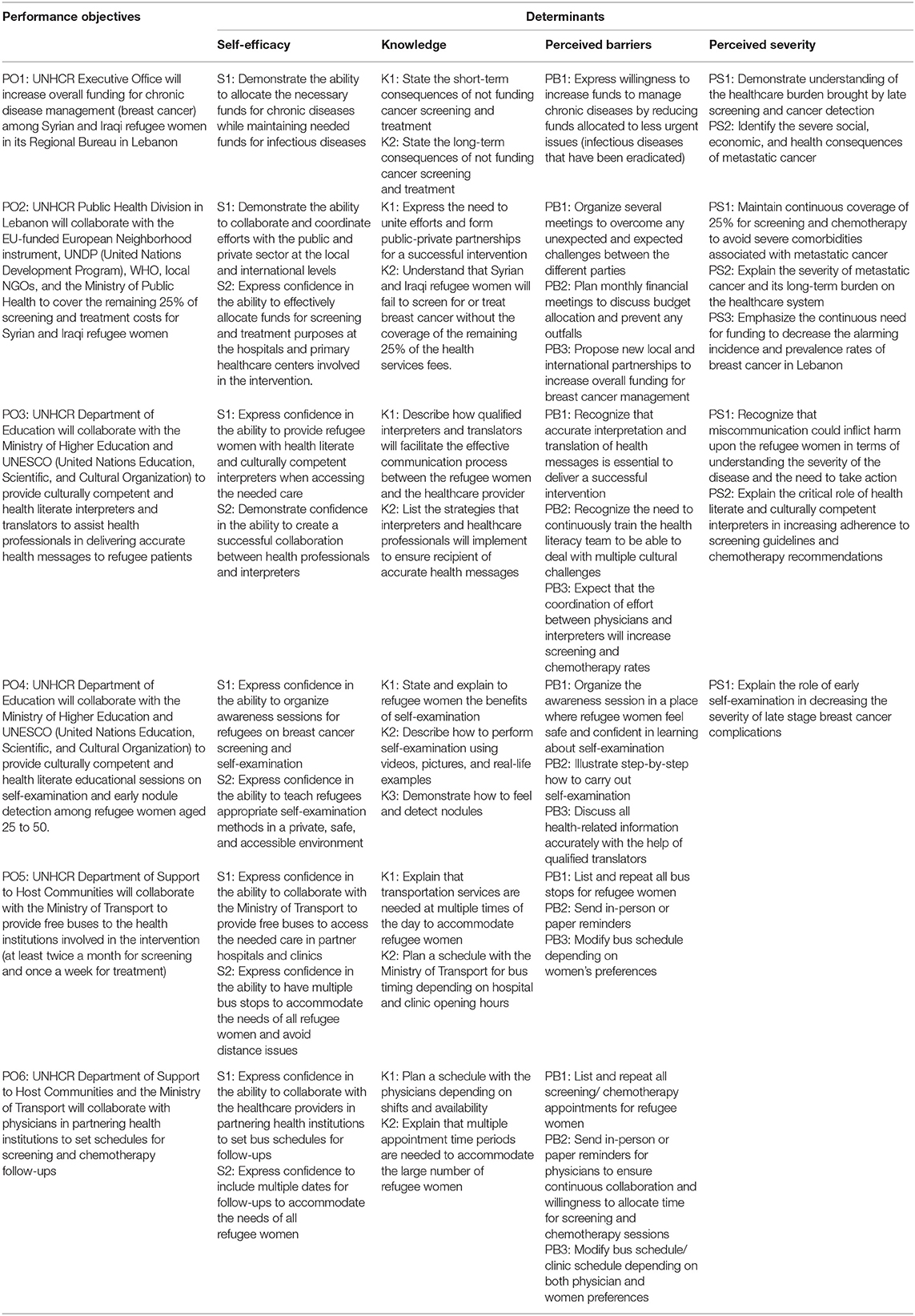

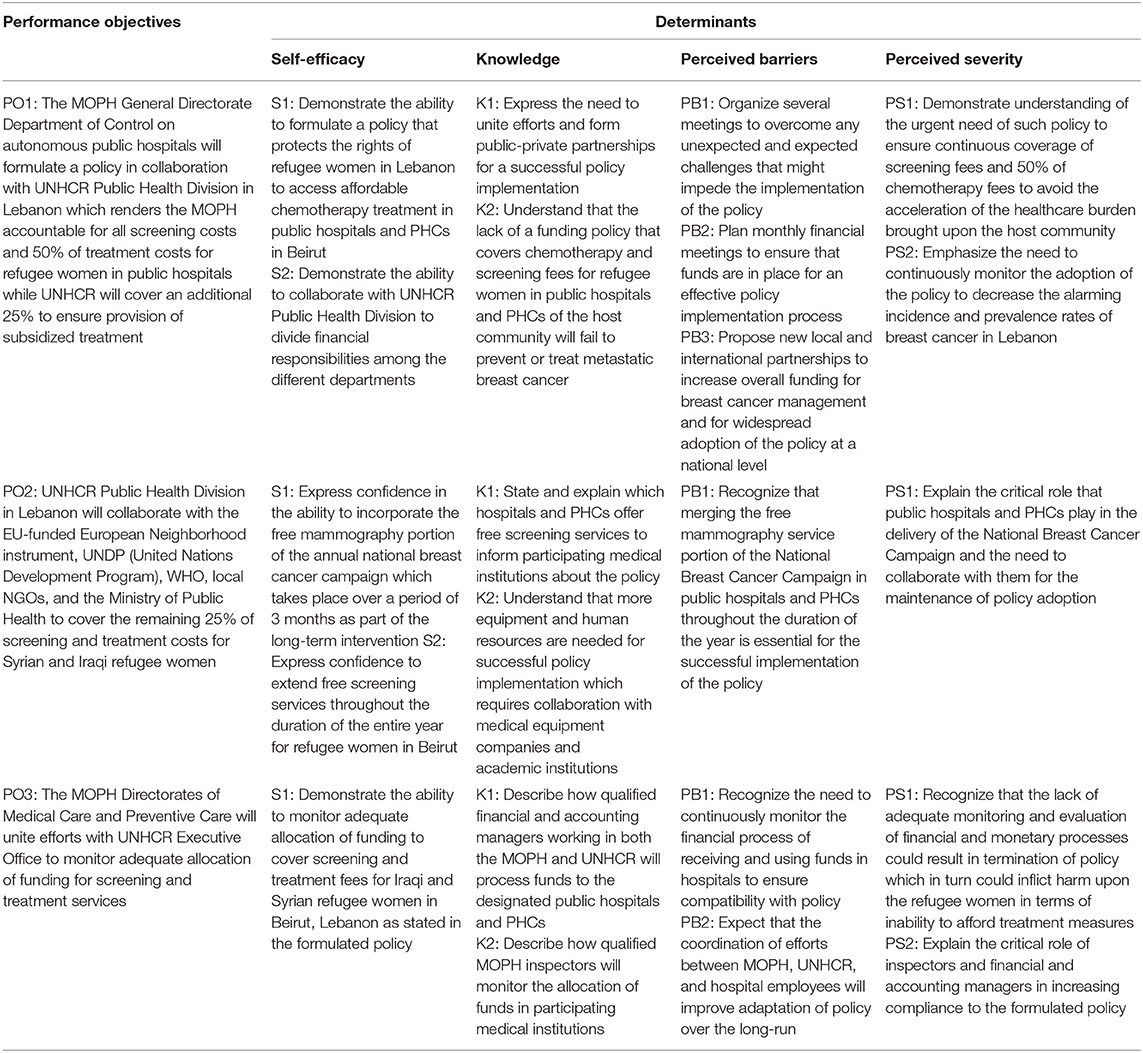

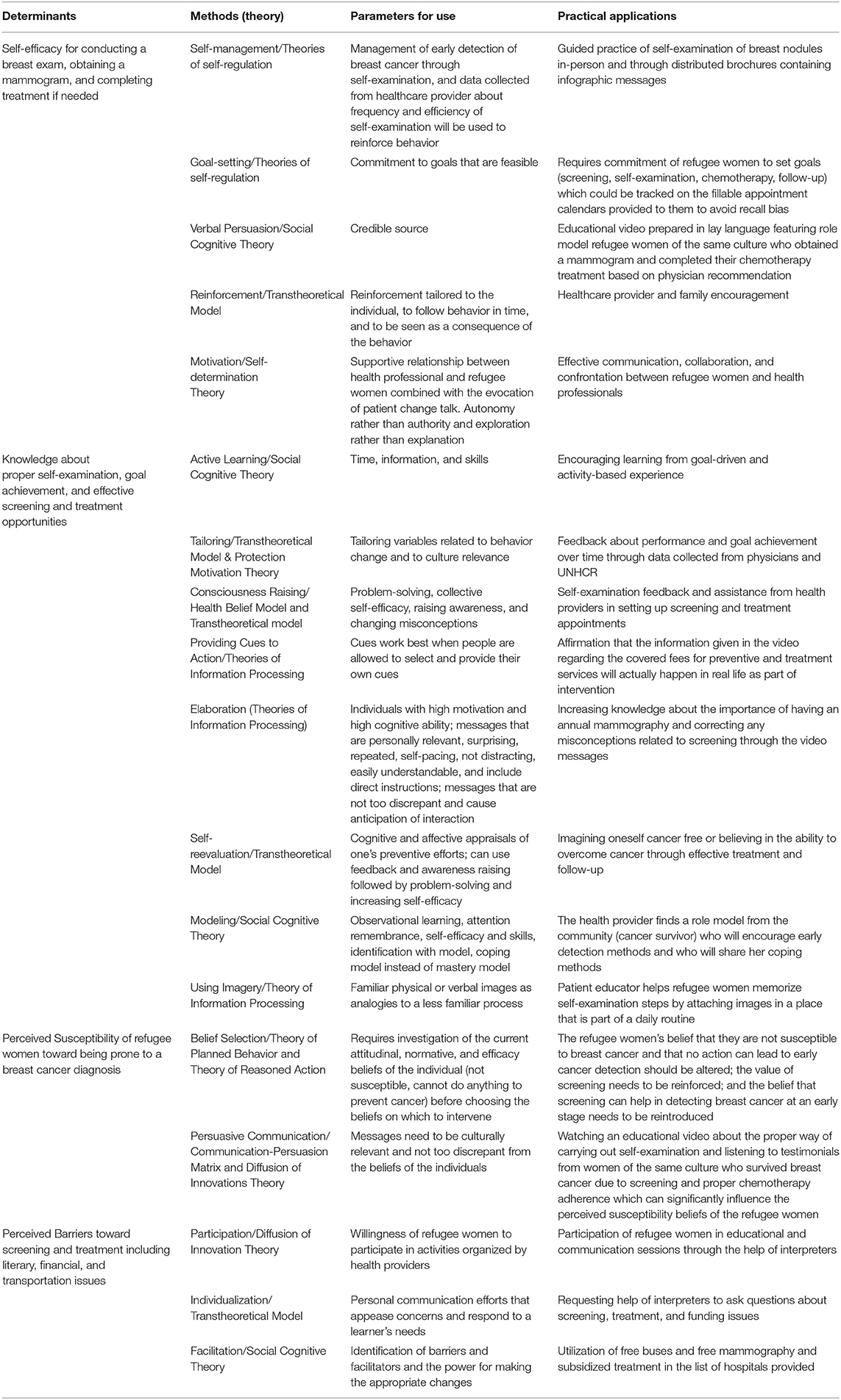

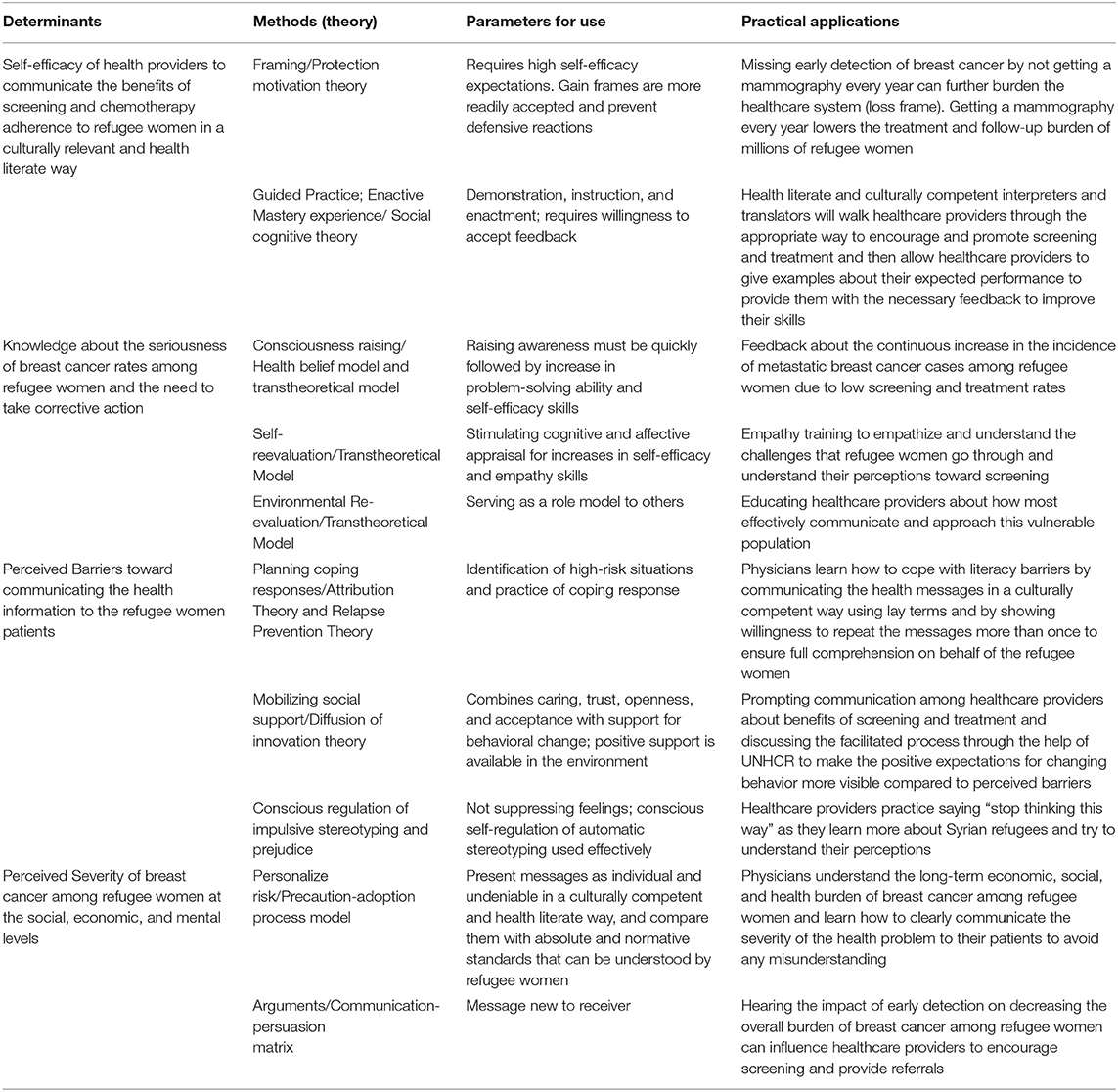

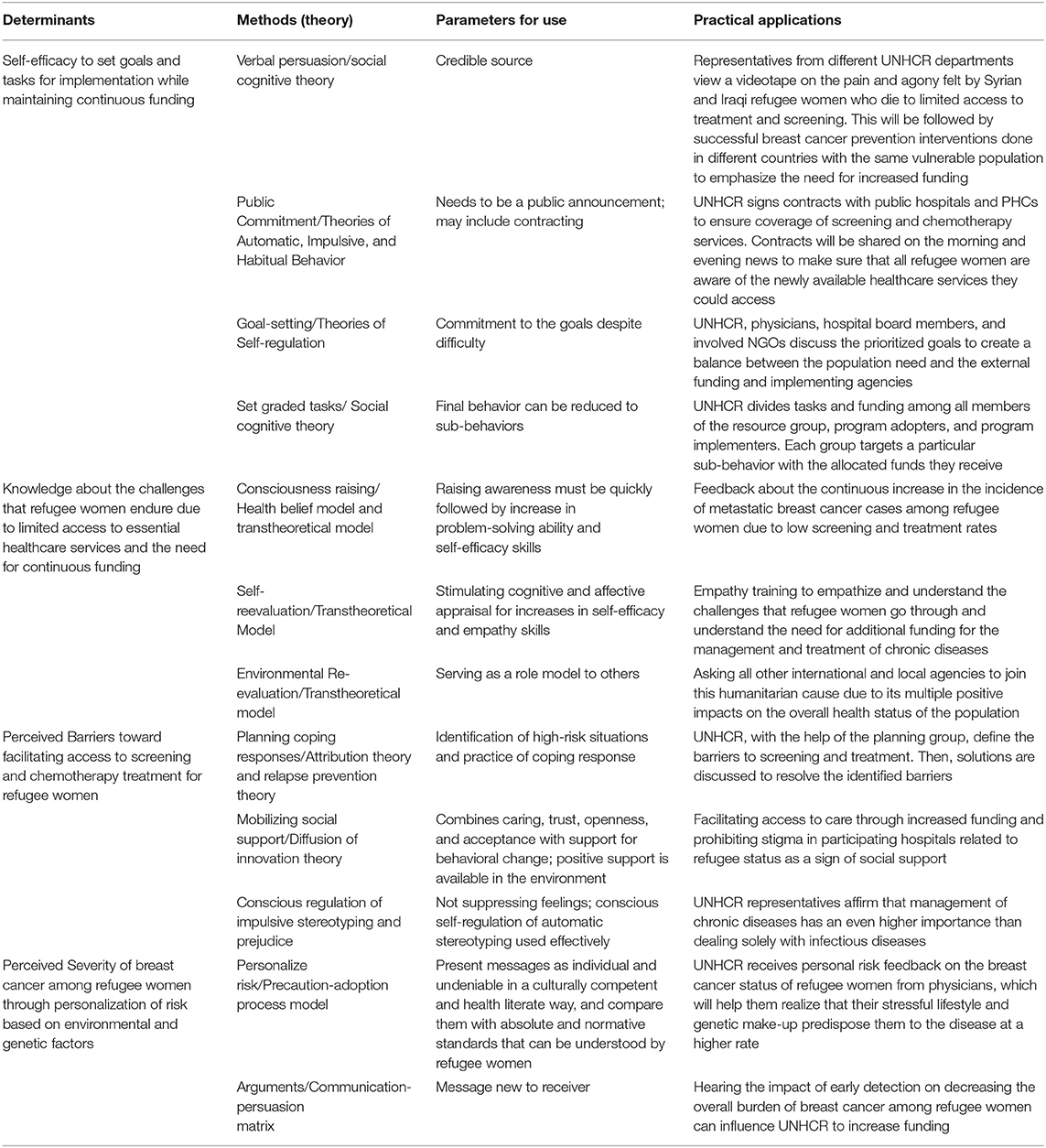

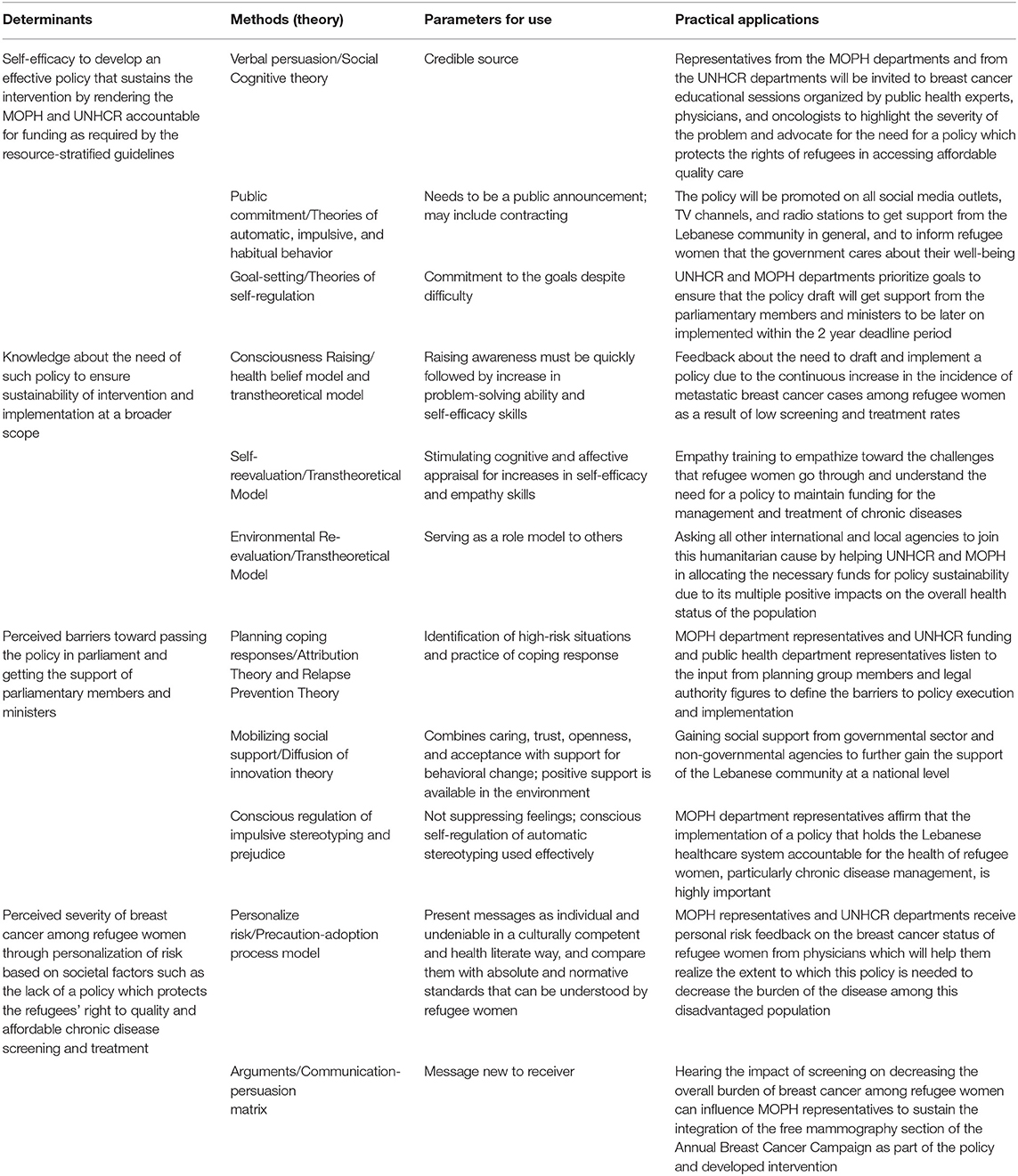

Performance objectives (POs) are developed by program planners for behavioral and environmental outcomes to ensure that the participants are performing at a criterion level that enhances the success of the developed intervention (21). The anticipated behavioral and environmental outcomes were further subdivided into POs. Matrices of change objectives (COs) were formulated for each of the identified behavioral and environmental outcomes. COs are considered to operate as a blueprint of the theoretical design rationale since they act as active ingredients of the intervention (52). Tables 1A–D list the POs of the different agents involved in this intervention (refugee women, physicians, UNHCR, and MOPH) along with their respective change objectives.

Table 1A. Performance Objectives for the Individual Behavioral Outcome: Syrian and Iraqi refugee women in Lebanon will undergo a mammogram once a year if aged between 30 and 55 and once every 2 years if aged 55 and above.

Table 1B. Performance Objectives for the Interpersonal Environmental Outcome: Physicians communicate with refugee women about importance of screening and recommend affordable treatment measures.

Table 1C. Performance Objectives for the Organizational Environmental Outcome: UNHCR will support refugee women in receiving early detection (screening and self-examination) and treatment (chemotherapy) measures.

Table 1D. Performance Objectives for the Societal Environmental Outcome: The Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) will formulate a policy that provides full coverage of screening services and 75% coverage of chemotherapy treatment for Syrian and Iraqi refugee women with breast cancer in Beirut, Lebanon.

IM Step 3: Program Design

The initial task of step 3 entails brainstorming ideas for a program theme, major intervention components, scope, and sequence. The end product is a draft plan that outlines the anticipated multilevel intervention.

Program Components

The main barriers to mammography screening and accessing quality chemotherapy treatment among Syrian and Iraqi refugee women with breast cancer in Lebanon are mainly financial, social, and educational. El Saghir et al. (3) and (1) emphasized the need to increase monetary aid allocated for chronic diseases, patient education, education of representatives of international organizations about the burden of breast cancer and its impact on this vulnerable population, assurance of consistent physician consultations and follow-up, along with aligning referrals with subsidized medical services with the purpose of observing positive significant changes in mammography rates and proper treatment adherence and chemotherapy completion. Hence, the long-term sustainability and success of the intervention in attaining the desired behavior change is dependent on several levels of the socioecological model including the intrapersonal (refugee women), interpersonal (physicians), organizational (UNHCR), and societal (MOPH) levels. At the individual behavioral level, Syrian and Iraqi refugee women residing in camps in the Beirut District of Lebanon will participate in an initial awareness campaign designed to promote the self-management of screening and treatment behaviors to help women overcome their fears and correct their misconceptions which prevent them from engaging in essential health-related actions (1, 3, 8, 15). The campaign will be followed by educational sessions on breast self-examination using role modeling techniques, in addition to informational sessions that will address the multiple ways refugee women can access the required care at the participating hospitals and primary health centers through free governmental transportation measures based on a previously set bus schedule that satisfies the preferences of both the refugee women and the physicians (53). Both types of sessions will be organized within the refugee camp setting and delivered by primary care physicians and specialized oncologists with the help of public health workers, community leaders, and interpreters and translators to assure the transmission of clear and culturally competent health and logistics information (54). An emphasis on the value of follow-up sessions and its powerful impact on the recovery process will be incorporated in the educational sessions. Refugee women will also be provided the opportunity to ask the on-site healthcare experts and educators about any concerns or uncertainties they have regarding their health status or the information they obtained throughout the progress of the program (1, 8, 15, 19, 46, 47, 47).

Environmental restructuring is a vital intervention component that needs to be achieved to ensure that the targeted behavior change will be maintained. At the physician level, change will consist of mandatory online trainings for physicians and public health workers to acquire culturally competent and health literate ways to effectively and clearly communicate with refugee women about the importance of undertaking mammography and completing their chemotherapy treatment. The online version of the trainings is more cost-effective and more feasible to physicians as they can complete the required sessions depending on their availability. Follow-up appointments will be integrated as part of a social support system for all refugee women to allow physicians to address re-emerging concerns and worries after screening or chemotherapy sessions (1, 12, 15, 19, 55).

At the organizational and societal levels, change will encompass the introduction of a new budget plan that calls for an increase in annual funds allotted to the management of chronic diseases. The new financial plan will be settled once the administrators and coordinators of several UNHCR-based departments and MOPH departments have arranged meetings with hospital board of directors, governmental representatives, and physicians working in participating public hospitals and PHCs to discuss the refugee camp environment. They will review findings from surveys completed within the refugee camps as well as the guidelines and protocols that should be developed for change to ensure that a collaborative approach has been adopted to establish a final budget plan that satisfies all involved sectors. The surveys, conducted by the planning group, will assess the refugee camp environment in terms of available resources, influential leaders in the camps, readiness of refugee women to participate in the intervention, along with potential barriers that might be encountered. This will help to identify any urgent barriers that need to be addressed prior to program implementation. The final budget plan will act as the foundation of the newly formulated policy which holds the MOPH fully accountable for screening services and holds both the MOPH (50%) and UNHCR (25%) accountable for the provision of subsidized chemotherapy fees as recommended by the resource-stratified guidelines (3, 20). The organizational strategic approach to change which incorporates leadership skills, future goals, and effective collaboration is considered to be an evidence-based practice for long-term change (56, 57). To raise awareness of the severity of metastatic breast cancer among refugee women in Lebanon and highlight the necessity of targeting the underlying and interfering factors (restricted funding, lack of awareness, limited access to quality treatment, no proper follow-up measures, fear), UNHCR and MOPH representatives will be invited to attend informational and orientation sessions prepared by a team of oncologists, physicians, community leaders, public health workers, and interpreters to fortify understanding of the obligation to deal with this particular health issue (1, 15, 16, 19, 30, 49, 50, 55, 58).

Newspapers, Public Service Announcements (PSAs), billboards, flyers, radio, and TV channels will be adopted as reinforcing channels and vehicles to increase attainment of the positive health behaviors. These media tools will be used to inform refugee women about the opportunity to participate in a multi-level intervention that will enable them to access the needed medical and preventive services either for free or at a significantly subsidized prize (for chronic chemotherapy treatment). The widespread promotion of the intervention will lead to the desired health outcomes, along with an accurate delivery of direct messages that are tailored to account for cultural and linguistic barriers (21). The mentioned methods will be used due to their success in reaching the Lebanese population during the annual breast cancer campaigns. The WHO has been supporting the annual national breast cancer campaigns since 2008 due to their remarkable success and their effective outreach efforts which has increased by more than 60% since the initial launch of the campaign (59). In 2014, one of the main barriers identified for the lack of interest of some women in seeking a mammography was the lack of support of family members. Therefore, the media campaign (flyers, videos, and billboards) was modified to portray women with their children and husbands to encourage family members to remind their wives/aunts/mothers to make a screening appointment. In 2016, fear was identified as an additional factor affecting screening rates among women. This lead the MOPH health promotion experts to think about creative outlets that could grab the attention of the Lebanese population at large. The Breast Cancer Pink Ribbon was then made in Lebanon's largest sports stadium using over 8,000 pink balls and was recorded in the World Academy record as the largest ribbon ever created (60, 61). A rise from 9,879 completed screenings in 2016 to a total of 21,752 was attributed to the success of the campaign which empowered women and their families to fight against breast cancer by taking the necessary preventive measures (37). By adapting a similar information environment and tailoring it to account for the culture of refugee women, the behavioral outcome is more likely to be successfully attained (54).

Program Theme

The program's theme will focus on empowering refugee women to screen for breast cancer and to seek treatment as recommended by their physicians. “My Right, My Fight” (Arabic-  ) is the chosen slogan for the intervention. “My Right” refers to the fact that Lebanon has no policy protecting the basic human rights of refugees such as accessing healthcare services at a reasonable price in the country's medical establishments (17). “My Fight” has to do with the actual empowerment act, which aims to encourage women to perform annual mammography and complete their chemotherapy treatment fully, if needed.

) is the chosen slogan for the intervention. “My Right” refers to the fact that Lebanon has no policy protecting the basic human rights of refugees such as accessing healthcare services at a reasonable price in the country's medical establishments (17). “My Fight” has to do with the actual empowerment act, which aims to encourage women to perform annual mammography and complete their chemotherapy treatment fully, if needed.

Program Scope and Sequence

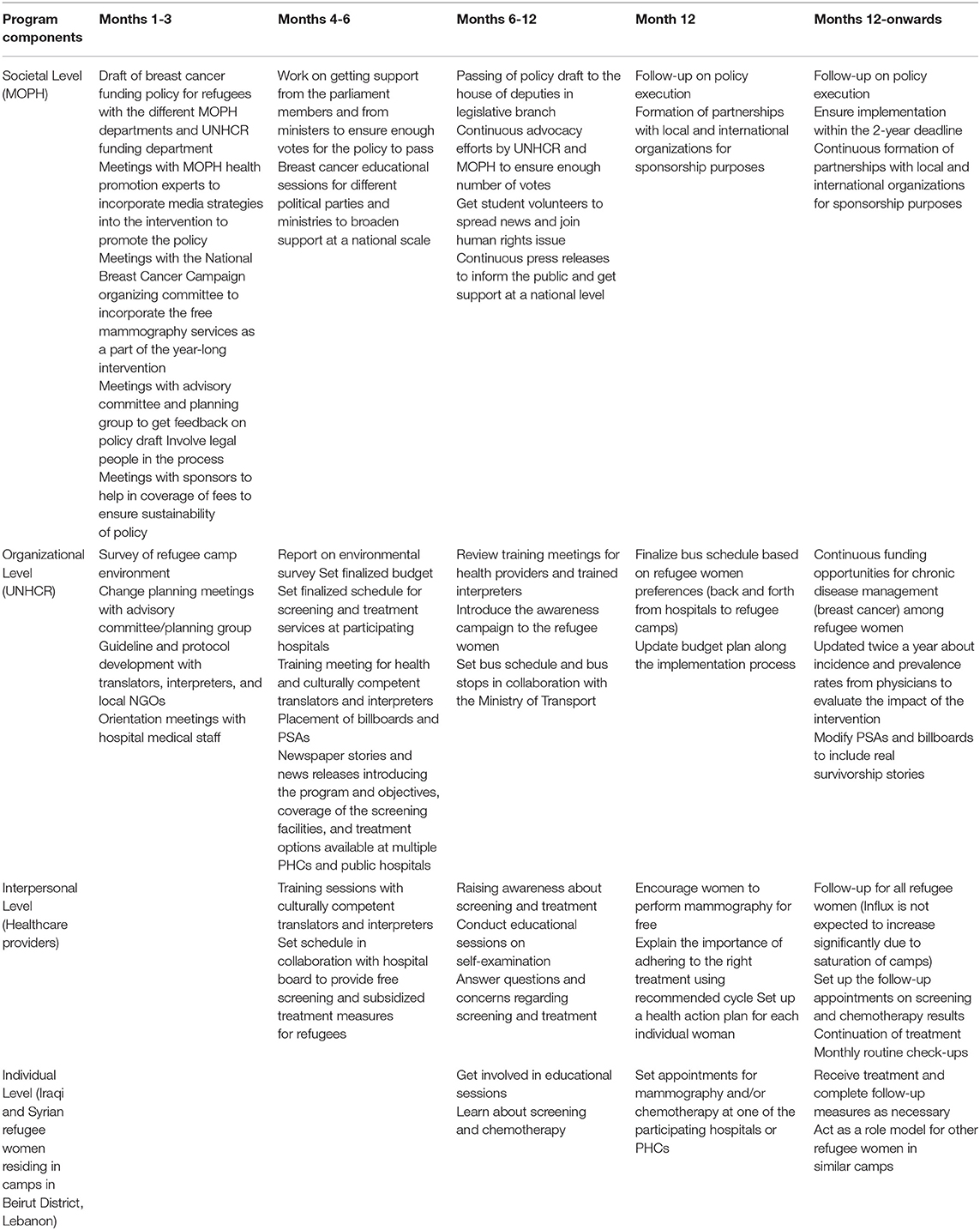

Table 2 provides a general overview of the program's intended scope and sequence. Note that the scope and sequence of the intervention might be modified depending on the willingness of the politicians to cooperate and the overall stability of the country. All activity time periods will be adjusted accordingly.

Table 2. Scope and Sequence in Months (Note that some components might take longer than expected due to political tension and instability in the country).

Theoretical Methods and Practical Applications

According to Bartholomew Eldredge et al. (21), theory-based change methods are general procedures aiming to influence determinants of behavioral and environmental outcomes. As for practical applications, they consist of real-life examples of how these methods will be delivered to the target population. However, researchers should make sure that these applications are culturally relevant to the context in which the intervention takes place (62). Parameters for use provide guidance to the health promotion program planners when applying these change methods by helping them take into account the diverse characteristics of the environment they are targeting (21).

Change methods at the individual level include active learning, modeling, verbal persuasion, facilitation (Social Cognitive Theory), tailoring, reinforcement, consciousness raising (Transtheoretical model), self-management, and goal-setting (Theories of Self-regulation). The main purpose behind these selected methods is to emphasize the severity of the disease for refugee women while highlighting the importance of screening and chemotherapy adherence in reducing the burden of breast cancer. The methods will be implemented in a supportive environment that eliminates anticipated structural and monetary barriers, in addition to providing hope for the target population by hearing success stories from refugee women survivors. At the interpersonal level, methods include framing (Protection Motivation theory), consciousness raising, self-reevaluation, environmental reevaluation (Transtheoretical model), mobilizing social support (Diffusion of Innovation theory), and personalizing risk (Precaution-Adoption process model). These strategies aim to influence healthcare providers by highlighting the alarming incidence and prevalence rates of breast cancer among the refugee population and stressing their role in improving the burden on the healthcare system through the development of effective health literate and culturally competent communication skills to educate the refugee population about prevention and treatment measures available to them in the country. By advocating for empathy and understanding when dealing with refugee women through the chosen methods, physicians are more likely to allocate their time to provide free mammography, subsidized treatment, and appropriate follow-up as depicted in the intervention plan. For the organizational level, verbal persuasion, setting graded tasks (Social Cognitive Theory), consciousness raising, self-reevaluation, environmental reevaluation (Transtheoretical model), arguments (Communication-Persuasion matrix), and planning coping responses (Attribution Theory and Relapse Prevention Theory) were some of the chosen methods to encourage UNHCR representatives to increase funding for breast cancer chronic disease management and adhere to the policy once implemented. These methods will also increase awareness about the severity of the disease and reduce the perceived barriers that might render them hesitant toward adopting and maintaining implementation of the intervention. Similar methods will be adapted at the societal level to allow the MOPH department representatives to acquire the skills needed to develop an effective policy draft to ensure the sustainability of funding, increase knowledge about the necessity of such a policy to alleviate the burden of breast cancer among refugee women, decrease perceived barriers including the complicated process of passing the policy in parliament, and increase perceived severity of breast cancer among refugee women to enhance motivation to advocate for the execution of the proposed policy. Tables 3A–D display examples of theoretical methods for determinants selected in Step 2 of IM. Parameters for effective implementation were identified for each method (column 3). The following tables can be considered as the blueprint of the intervention where all COs will be covered by the planned program.

Table 3A. Selected Methods, Parameters for Use, and Practical Applications for the Determinants of the Behavioral Outcome “Syrian and Iraqi refugee women in Beirut District of Lebanon will undergo a mammogram once a year if aged between 30 and 55 and once every two years if aged 55 and above”.

Table 3B. Selected Methods, Parameters for Use, and Practical Applications for the Determinants of the Interpersonal Environmental Outcome “Physicians communicate with refugee women about importance of screening and recommend affordable treatment measures.”

Table 3C. Selected Methods, Parameters for Use, and Practical Applications for the Determinants of the Organizational Environmental Outcome “UNHCR will support refugee women in receiving early detection (screening and self-examination) and treatment (chemotherapy, radiology) measures.”

Table 3D. Selected Methods, Parameters for Use, and Practical Applications for the Determinants of the Societal Environmental Outcome “MOPH will support refugee women in receiving early detection (screening and self-examination) and treatment (chemotherapy, radiology) measures by drafting and implementing a policy which renders the MOPH and UNHCR both accountable to provide the necessary services.”

IM Step 4: Program Materials and Educational Components

Step 4 focuses on how the program materials will be created, organized, pretested, and produced based on the matrix of change objectives, the methods, and practical applications previously identified. Taking into account Shioiri-Clark's (43) findings about preferences of refugee populations in receiving educational material, the video series, brochures, bus schedule handouts, appointment calendars, and follow-up material will be developed after involving a multidisciplinary team of experts to pitch-in the generation of drafts. The educational instruments will also integrate the resource-stratified guideline recommendations which stress the need to provide assessments of levels of evidence and thorough details which in turn reflect upon the rationale for the guideline options listed. All materials are culturally relevant and health literate to accommodate for the religious beliefs and educational levels of the refugee population (60, 61).

Description of Program Components

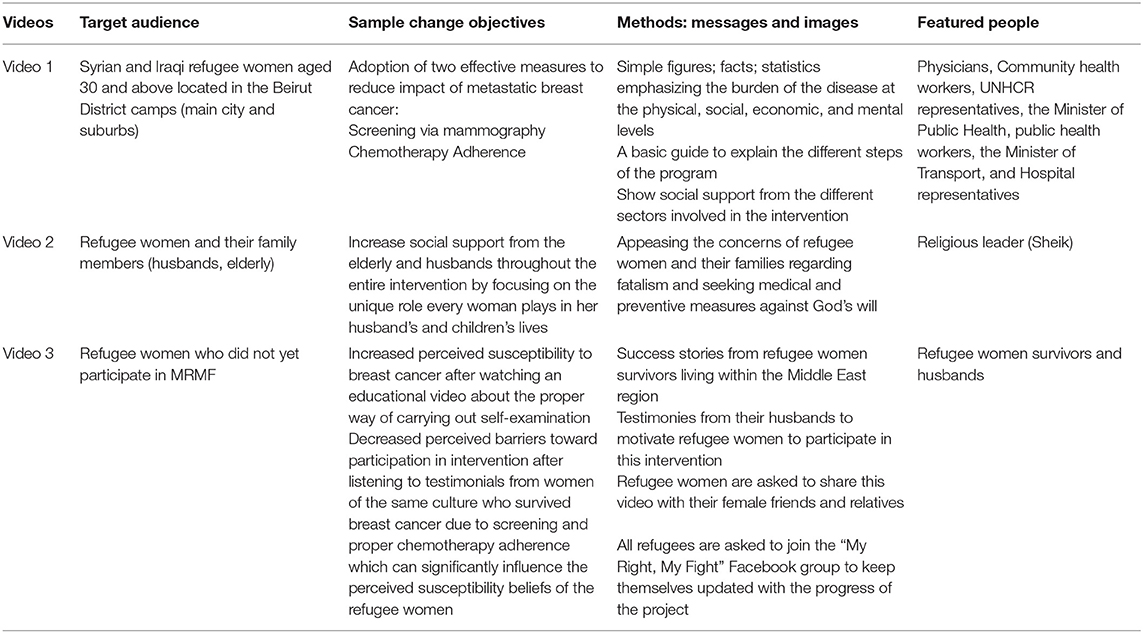

The “My Right, My Fight” video series are tailored components that accommodate for health literacy and cultural competence by providing the target audience (refugee women and their families) with basic health information using the Arabic language to disseminate figures, facts, and imagery. The target audience is Syrian and Iraqi refugee women (aged 25 and above) located in the Beirut District camps (main city and suburbs). However, since family support plays a crucial part in the cultural norms and traditions of this community, the videos will be disseminated to the two most commonly used phone applications (Whats app groups and Facebook pages) by refugee women and their husbands (60, 61). The main aim behind these videos is to introduce the target audience to the overall intervention and the severity of the addressed health problem. Three videos will be broadcast across the different social media outlets. A detailed description of each of the video's target audience, sample change objectives, methods (messages and images), and featured people is included in Table 4. Monthly videos of participants will be featured with their families, and continuous awareness public service announcements (PSAs) will be uploaded to answer concerns about screening and chemotherapy (eg., fear of pain, cost, detecting the unknown). These videos will also be shared on morning TV shows to further encourage women to join the fight and claim their right to lead a healthy lifestyle. The methods applied for the videos' change objectives incorporate cues to action and reinforcement through affirmation of covered fees by the credible people included in the video, modeling by religious leaders to appease concerns regarding disrespecting religious beliefs, modeling regarding transportation issues by involving the Minister of Transport who will explain the bus schedule and bus stops that will be set up later on through a collaboration between refugee women and healthcare providers, and elaboration to increase knowledge and correct misconceptions about screening. The producers for this program material consist of a team of graphic designers, health educators, oncologists, translators, interpreters, religious leaders, and community health workers. The involvement of an eclectic team in the design and implementation process will ensure a successful delivery of the tailored health messages. Contracts and budgets will be set between graphic designers and the main funding agencies. Public health professionals, community health workers, and physicians will follow up on the progress of the video production processes to ensure that the initial ideas, sketches, and other proposed visual suggestions are compatible with the culture and values of the target audience on one hand and are effectively transmitting the health messages on the other hand.

In addition to the described video series, billboards that promote the theme, “My Right, My Fight,” will be designed and will target refugee women and their husbands to grab their attention and increase their knowledge, perceived susceptibility, and perceived severity of the health problem, in addition to empowering them to take action by increasing their self-efficacy to engage in screening and treatment measures. The planning group will also design a brochure to be distributed to the refugee women during the educational sessions. The brochure will include an infographic portraying images and messages with information about breast cancer, breast cancer self-examination, and clinical breast examination, steps to follow to reach bus stops, a list of participating hospitals and PHCs (directions and a phone number for reference will be included), fillable appointment calendars to avoid recall bias, and guidelines that should be adhered to for proper follow-up completion. The brochure will also be disseminated on Whats App and Facebook to ensure maximum reach.

Interviews, nominal group technique sessions, and trainings will be held for physicians, public health professionals, community health workers, translators, and interpreters to ensure a detailed understanding of the intervention objectives and to assure the integration of cultural competence and health literacy factors when coming in contact with the target population. These techniques aim to target the self-efficacy of physicians to improve their communication skills with refugee women after undergoing health literacy and cultural competency trainings with expert anthropologists and professional interpreters; their knowledge about the seriousness of breast cancer rates among the disadvantaged population through nominal group techniques in the presence of multiple facilitators who are knowledgeable about the field of refugee health; in addition to addressing their perceived barriers and perceived severity through individual and group interviews to overcome any challenges that might hinder the success of the program. Program planners and the team of producers (graphic designers, video editors, health educators) will organize weekly meetings to certify that all intervention steps are progressing positively and to make any alterations based on the feedback received from focus groups or from the health workers during the preliminary phases of the intervention.

Cultural Issues

One of the most essential factors to consider throughout all the steps of intervention mapping is cultural relevance. Cultural issues that need to be addressed specifically when designing the proposed program components pertain to two cultural dimensions: deep structure and surface structure. Deep structure consists of culture factors that influence the behaviors of the target population such as family relationships, religion and ethnic identity, level of acculturation, individuality vs. collectivity, and medical perceptions. In this case, deep structure includes religious and cultural beliefs of Syrian and Iraqi refugees since most of them come from a conservative Muslim background. Seeking screening and treatment measures might be regarded as disrespecting “God's will” or fatalism. Another deep structure factor is family relationships since women tend to seek their husband's approval in matters affecting their personal lives such as medical decisions (15). The level of acculturation and their ethnic identity is also an important factor since many Syrian refugees feel neglected by the Lebanese government and population and are discriminated against when seeking aid in any form (1, 3). For surface structure, this involves the no less important but more superficial cultural aspects of a community such as language, mode of communication, and inclusion of familiar people (21). The intervention will be delivered using the Arabic language; however, translators and interpreters need to make sure that the dialect of the Syrian and Iraqi refugees is taken into consideration to avoid any misunderstanding when delivering the health messages.

Increasing Cultural Relevance

To increase cultural relevance for the deep structure factors, a religious leader will be included in one of the videos (Sheik) to explain the importance of seeking preventive and medical care and to appease concerns regarding going against God's will if the refugee women agreed to participate in the intervention. Several representatives from the different involved organizations and institutions are featured in the first video to increase credibility and ensure social support from both the private and public sector in improving access to the needed care for the refugees. The Minister of Transport, the Minister of Public Health, the Head of UNHCR Public Health Division, a religious leader, refugee women breast cancer survivors and their supportive husbands, and a team of public health professionals, community health workers, and physicians will be featured in the video series to emphasize the importance of this intervention in alleviating the burden of the disease. The inclusion of all sectors and actors will encourage refugee women and their husbands to be part of the intervention as they feel wanted rather than neglected by their host community. Both translators and interpreters will be part of the video development to guarantee an effective delivery of health messages in Arabic and avoid any unintentional offensive wording that could affect the credibility of the entire intervention. Informed consent will be taken from all involved parties prior to the development of this interactive media tool.

Methods for Pre-testing and Pilot-Testing of Individual and Environmental Prototype Components

Concept testing

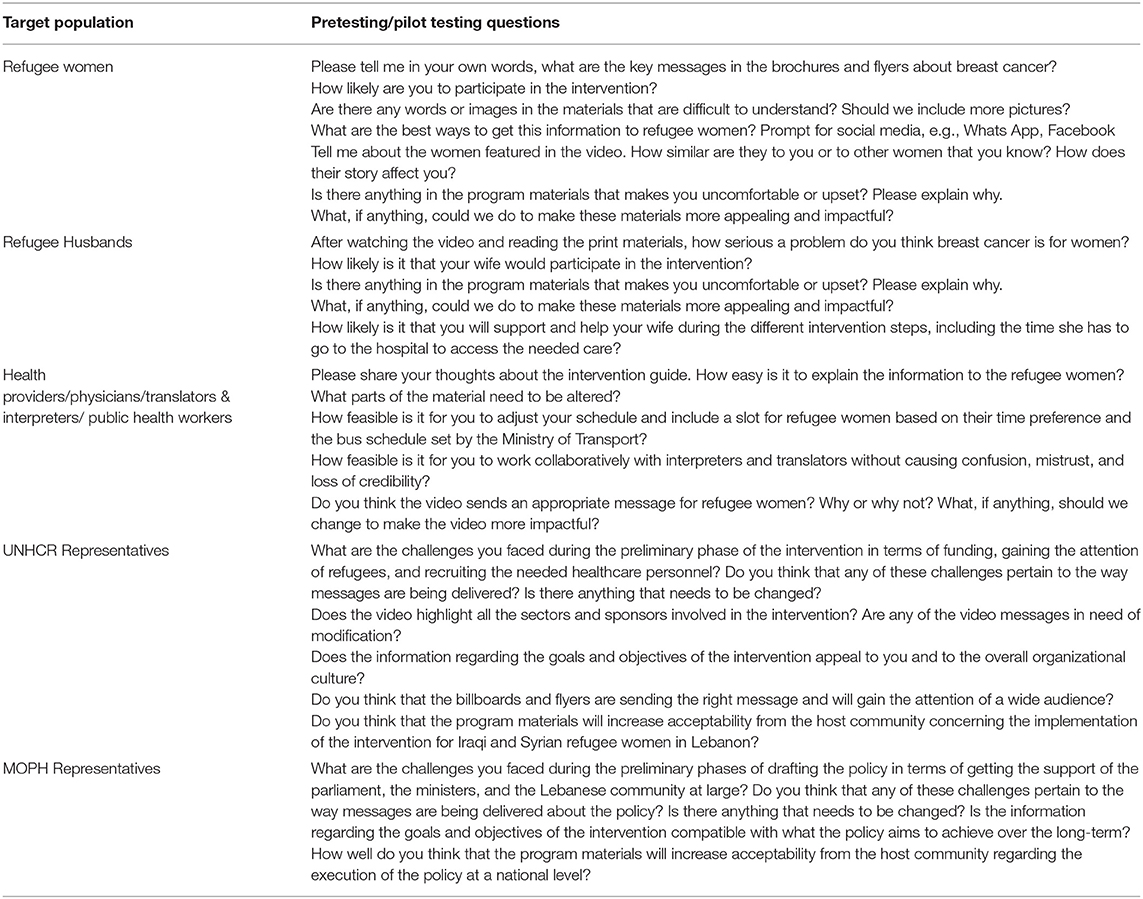

Concept testing consists of testing key phrases and visuals that emphasize the main ideas of the designed project. Since this intervention plan has been developed primarily based on available literature, it will be essential to conduct concept testing during the development phases of the intervention. To test the images and messages proposed for the videos, billboards, and brochures, focus groups (6–10 members each) will be formulated in camp settings to assess how the target population understands the tailored messages. This feedback will inform any recommended revisions. The focus groups will be formed with the help of public health professionals working with UNHCR since they are deemed credible by the refugee population in camps and their leaders, also known as the Shawishes, and thus will enhance participation in the progress of intervention preparation and implementation by helping in the identification of women who are suffering from breast cancer or who are related to someone diagnosed with the disease. Credibility of organizations from the refugees' perspective is associated with the provision of basic assistance and humanitarian aid. Participation is on a voluntary basis, and women will be informed about the purpose of the discussion and the aim of the intervention in improving their overall health. Additionally, two different versions of the brochure will be tested to see whether refugee women were more comfortable in learning through visuals rather than words and vice-versa. Husbands will be included in separate focus groups to see whether videos and billboards were effective in increasing household-based social support.

To concept test training manuals, physicians, public health professionals, and community health workers will be invited to review the training materials and provide feedback on their effectiveness and acceptability. These trained individuals are employees within the different institutions who act as stakeholders in the development and implementation of the intervention.

Readability testing

This pretesting method aims to determine the educational and literacy levels of the target population to design the program materials accordingly. For the sake of this intervention, we will be tailoring the International Adult Literacy Survey to Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Lebanon. This tool is made up of 10 items that were originally developed to determine the literacy level of adult immigrants coming into the U.S (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d). The readability of the informational brochures, bus schedules, appointment calendars, and follow-up material provided by the physicians will all be tailored to the educational level of the majority of Iraqi and Syrian refugees in the targeted camps.

Message execution

This form of testing seeks to assure that the program materials and messages are relevant, culturally acceptable, and comprehensible by the target population. Brochures, billboards, and video assessments will be shared with groups of refugee women and their husbands by organizing focus group sessions and interviews with community health workers and translators. However, prior to the distribution of the intervention items to refugees, the program planners, interpreters, translators, and the team of producers will make sure that the written messages incorporate a cultural perspective to ensure effective communication through the selected delivery vehicles and will include the concept of decentering in translation to justify the choice of words selected in the foreign language to convene the desired health message. The presentation of medical terminology in the program materials will be simplified to promote processing of information and allow for improved understanding of the benefits of screening and the diagnosis and treatment processes of breast cancer. The design of the print material will be reviewed to sustain compatibility between the intervention objectives and the delivery vehicles and to avoid any unnecessary diversions. As for the videos, the scripts and storyboards will be edited before the pre-testing and pilot testing phase to ensure that all elements of the design document are met and that both the planning team and production team are on the same page. Table 5 includes example questions that will be asked during the pretesting/pilot testing phase.

Impact

A questionnaire evaluating each of the determinants targeted by the different intervention components will be distributed to refugee women during focus group sessions and preliminary phases of the intervention to assess the impact of program change methods. The collected data will give us an idea if any corrective actions need to be taken for the selected change methods.

Adoption/implementation characteristics

The purpose of this final step is to predict any potential problems with implementation. To determine the perceptions of implementers toward complexity, trialability, observability, and relative advantage of materials, separate focus groups will be conducted for the different sectors involved in the intervention including the intrapersonal (refugee women), interpersonal (physicians), organizational (UNHCR), and societal levels (MOPH) along with the other members of the planning group. To evaluate trial implementation, the research team will collect qualitative data through observation and ethnographic techniques regarding how well the refugee women are responding to the print and media material, how the communication process is going between physicians and target populations while having interpreters and translators as a third party mediator, how well the coordination of events and the funding of services is happening at the organizational level, how smoothly the policy execution process is going, and how motivated refugee women are to participate in all steps of the intervention after adequately understanding the impact of the problem through culturally relevant and health literate communication processes. Information tracking the evolution of the policy process and the passing of the draft in parliament will also be updated continuously to detect and deal with unexpected and expected challenges at an early stage. The data will then be shared with all members of the planning group to carry out the necessary changes.

Discussion

This article delineates an intervention plan to increase breast cancer screening and chemotherapy adherence among Syrian and Iraqi refugee women residing in refugee camps in Beirut. It also provides future public health workers and research experts with an intervention plan for a concerning health issue in Lebanon that is disproportionately affecting disadvantaged populations in the country, specifically refugees. High incidence and prevalence rates of metastatic breast cancer among Iraqi and Syrian refugee women should be urgently addressed in camp settings since the limited funds allocated for the management of chronic diseases among asylum seekers in Lebanon renders the diagnosis of breast cancer at an early stage currently impossible (3, 11, 17). Therefore, implementing a health promotion intervention using the intervention mapping approach can integrate the multiple disciplines of public health to increase the adoption of the targeted health behaviors (mammography, chemotherapy adherence, proper follow-up measures) and subsequently reduce the overall financial, social, and health burden of the disease which not only inadvertently impacts refugee populations but also the host community at large (1, 3, 6, 11). Since the intervention has not yet been implemented, IM Steps 5 (Designing an Implementation Plan) and 6 (Creating an Evaluation Plan) will be described seperately after completion of the program. The rationale behind using IM is the integration of both the theoretical aspects of health promotion along with the evidence and new data from the literature to find sustainable solutions that address the personal and environmental determinants using a socioecological perspective. IM was also helpful in selecting the most effective theory-based change methods and appropriate practical applications, in addition to clarifying multiple factors that should be taken into consideration when designing and creating educational program components.

The developed “My Right, My Fight” (MRMF) program targeted one primary behavioral and three environmental outcomes which were deemed most effective in addressing high rates of breast cancer. Both mammography and self-examination of nodules contribute to the early detection of cases and to increasing positive response rates to treatment (46–48). The interpersonal and organizational environmental outcomes will play a crucial role in ensuring the overall success of the intervention and in attainment of the desired health behaviors (63). Having UNHCR support diagnostic and treatment measures through an increase in the allocation of funds for refugee chronic disease management and creation of supportive and trustworthy patient-physician relationships which take into account the cultural norms of the refugee population will be an essential factor in ensuring the sustainability of the program and the targeted health outcomes based on previous research studies and intervention projects (12, 19, 49, 50). Moreover, the creation and execution of a comprehensive policy at the societal level which protects the rights of refugees in accessing chronic disease screening and treatment services and encompasses the options as depicted by the internationally recognized resource-stratified guidelines is also a major key factor in determining the long-term success of the intervention (3, 20, 51, 63).

This intervention was based on a culturally competent and health literate approach to emphasize respect and acknowledgment of the refugee women's norms and perceptions. The different steps of IM integrated within “My Right, My Fight” will take into account cultural sensitivity to increase the credibility of the program and to foster high retention rates along the entire process (1, 19, 21).

Limitations

Due to the limited quantitative studies available about this particular topic, the following intervention has been based mostly on the needs assessment carried out by looking at qualitative research studies targeting refugee populations in Lebanon and the surrounding Middle Eastern region. Despite it being mainly theoretical, we believe that the application of the IM approach to our developed intervention will greatly contribute to the effectiveness of “My Right, My Fight” (MRMF) since this plan acts as a guide for a team of multidisciplinary health experts working with refugee populations in third world countries (52, 64). The incorporation of the resource-stratified guidelines adds credibility and elevates the chances of success and sustainability as emphasized in the literature (3, 20, 51). However, due to the political instability reigning over the Middle East region including Lebanon, many challenges (expected and unexpected) can take their toll on the advancement and fulfillment of the program, especially in terms of allocation of funds on a long-term basis (65). Additional external sponsors will be needed, and a collaboration of the different local and international agencies will impart the support needed for the continued adoption and implementation of the program.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Author Contributions

LS and CM: development of the program plan and manuscript development and primary writers. JF: critical review of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Sahloul E, Salem R, Alrez W, Alkarim T, Sukari A, Maziak W, et al. Cancer care at times of crisis & war: the syrian example. Am Soc Clin Oncol. (2017) 3:338–345. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.006189

2. Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer in women: burden and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2017) 26:444–57. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0858

3. El Saghir NS, de Celis ESP, Fares JE, Sullivan R. Cancer care for refugees and displaced populations: middle east conflicts and global natural disasters. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. (2018) 38:433–438. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_201365

4. Goktas B, Yilmaz S, Gonenc MI, Akbulut Y, Sozuer A. Cancer incidence among syrian refugees in Turkey, 2012–2015. J Int Migr Integration. (2018) 19:253–8. doi: 10.1007/s12134-018-0549-1

5. Tfayli A, Temraz S, Abou Mrad R, Shamseddine A. Breast cancer in low- and middle-income countries: an emerging and challenging epidemic. J Oncol. (2010) 2010:490631. doi: 10.1155/2010/490631

6. El Saghir NS, Daouk S, Saroufim R, Moukalled N, Ghosn N, Assi H, et al. Rise of metastatic breast cancer incidence in lebanon: effect of refugees and displaced people from syria and patients from War-Torn Iraq. The Breast. (2017) 36:19–76. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(17)30759-2

7. Al Qadire M. Cancer awareness and barriers to seeking medical help among Syrian refugees in Jordan: a baseline study. J Cancer Educ. (2017) 34:19–25. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1260-1

8. Gondek M, Shogan M, Saad-Harfouche FG, Rodriguez EM, Erwin DO, Griswold K, et al. Engaging Immigrant and Refugee Women in Breast Health Education. J Cancer Educ. (2015) 30:593–8. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0751-6

9. Holmes D. Chronic disease care crisis for Lebanon's Syrian refugees. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2015) 3:103. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70196-2

10. Masoudiyekta L, Dashtbozorgi B, Gheibizadeh M, et al. Applying the health belief model in predicting breast cancer screening behavior of women. Jundishapur J Chronic Dis Care. (2015) 4:e30234. doi: 10.17795/jjcdc-30234

11. Spiegel P, Khalifa A, Mateen FJ. Cancer in refugees in Jordan and Syria between 2009 and 2012: challenges and the way forward in humanitarian emergencies. Lancet Oncol. (2014) 15:290–7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70067-1

12. Taha H, Nystrom L, Al-Qutob R, Berggren V, Esmaily H, Wahlström R. Home visits to improve breast health knowledge and screening practices in a less privileged area in Jordan. BMC Public Health. (2014) 14:428. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-428

13. UNHCR. Refugee Cancer Patients Go Untreated for Lack of Funds, Warns the UN Refugee Agency. Press Releases. (2014). Retrieved from: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/press/2014/5/537f413a6/refugee-cancer-patients-untreated-lack-funds-warns-un-refugee-agency.html (accessed April 02, 2019).

14. Percac-Lima S, Ashburner JM, Bond B, Oo SA, Atlas SJ. Decreasing disparities in breast cancer screening in refugee women using culturally tailored patient navigation. J General Int Med. (2013) 28:1463–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2491-4

15. Saadi A, Bond B, Percac-Lima S. Perspectives on preventive health care and barriers to breast cancer screening among Iraqi women refugees. J Immigr Minor Health. (2011) 14:633–9. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9520-3

16. Vahabi M, Lofters A, Kumar M, Glazier RH. Breast cancer screening disparities among urban immigrants: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:679. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2050-5

17. Yahya M. Policy Framework for Refugees in Lebanon and Jordan. Unheard Voices. (2018). Retrieved from: https://carnegie-mec.org/2018/04/16/policy-framework-for-refugees-in-lebanon-and-jordan-pub-76058 (accessed April 02, 2019).

18. Saliba I. Refugee Law and Policy: Lebanon. Library of Congress. (2016). Retrieved from: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/refugee-law/lebanon.php (accessed April 02, 2019).

19. El Saghir NS, El Tomb PA, Carlson RW. Breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in low- and mid-resource settings: the role of resource-stratified clinical practice guidelines. Current Breast Cancer Reports. (2018) 10:187–95. doi: 10.1007/s12609-018-0287-6

20. Anderson BO, Yip CH, Smith RA, Shyyan R, Sener SF, Eniu A, et al. Guideline implementation for breast healthcare in low-income and middle-income countries: overview of the Breast Health Global Initiative Global Summit 2007. Cancer. (2008). 113 (Suppl. 8):2221–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23844

21. Bartholomew Eldregde LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernàndez ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach 4th ed (2016). Hoboken NJ: Wiley.

22. Fernández ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, Williams J, Saavedra-Embesi M, Chan W, et al. Effectiveness of Cultivando la Salud: a breast and cervical cancer screening promotion program for low-income Hispanic women. Am J Pub Health. (2009) 99:936–43. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136713

23. Fernandez ME, Gonzales A, Tortolero-Luna G, Partida S, Kay Bartholomew L. Using intervention mapping to develop a breast and cervical cancer screening program for hispanic farmworkers: cultivando la salud. SAGE J. (2005) 6:394–404. doi: 10.1177/1524839905278810

24. Fernández-Esquer ME, Espinoza P, Ramirez AG, McAlister AL. Repeated Pap smear screening among Mexican-American women. Health Educ Res. (2003) 18:477–87. doi: 10.1093/her/cyf037

25. Serra YA, Colon-Lopez V, Savas LS, Vernon SW, Fernández-Espada N, Vélez C, et al. Using intervention mapping to develop health education components to increase colorectal cancer screening in Puerto Rico. Front Public Health. (2017) 5:324. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00324

26. Crosby R, Noar S. PRECEDE-PROCEED. Rural health promotion and disease prevention toolkit. J Public Health Dent. (2011). 71:S7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00235.x

27. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass (2008).

28. Kazour F, Zahreddine NR, Maragel MG, Almustafa MA, Soufia M, Haddad R, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in a sample of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. J Compr Psychiatry. (2017) 72:41–47 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.09.007