- 1College of Advanced Studies, Philippine Normal University, Manila, Philippines

- 2Institute of International and Comparative Education, Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 3Comparative Education and Students Critical Leadership Society, Manila, Philippines

- 4College of Teacher Development, Philippine Normal University, Manila, Philippines

- 5Institute of Creative Expression and Human Movement Education (ICHEME), Philippine Normal University, Manila, Philippines

This study investigated the mainstreaming of Gender Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (GEDI) principles into community extension programs carried out by a university as a case study, highlighting the extent of implementation, challenges, and opportunities. A qualitative case study design was employed, utilizing semi-structured interviews with eight faculty members from five campuses at Y University. Data were thematically analyzed to identify key challenges, opportunities, and evaluation measures for GEDI implementation. The findings revealed that metrics such as participation rates, qualitative feedback, and impact assessments serve as indicators of program effectiveness. Challenges include limited familiarity with GEDI, cultural resistance, and resource constraints that hinder effective integration. However, opportunities exist through needs-based assessments, stakeholder collaboration, targeted capacity-building programmes, and sustainability-focused initiatives. This study contributes to the limited research on GEDI integration into community extension programmes in higher education. This highlights the role of extension programs in promoting equity and inclusion and offers insights for improving program design and sustainability. This study was limited to one Teacher Education Institution (Y University) and had a small sample size. Future research should explore diverse institutional settings and develop sustainability metrics for integrating GEDI into community engagement initiatives.

Introduction

Globally, higher education institutions increasingly acknowledge the importance of fostering gender equality, diversity, and inclusion. Gender equality, the cornerstone of development goals, is a critical area in which higher education institutions play a pivotal role. Efforts to advance gender equality include gender-focused training programs, leadership development initiatives, and integrating gender perspectives into the curriculum (Campanini Vilhena et al., 2024; Condron et al., 2023a). These institutions implement various initiatives to create inclusive environments, such as affirmative action policies, diversity training programs, and targeted recruitment strategies (Gururaj et al., 2021; Yahchouchi and Rotabi, 2023). However, despite these initiatives, significant challenges persist. Gendered inequalities remain prevalent, particularly in senior academic positions, and systemic barriers continue to hinder the progress of minority groups (Belluigi et al., 2024).

Research indicates that women are more involved in community service and extension activities than are men (Smith, 2005). Community extension programmes play a vital role in advancing gender equality, diversity, and social inclusion through targeted strategies and initiatives. For example, agricultural extension programs are encouraged to implement gender-sensitive recruitment practices to ensure equitable access to training opportunities for women. These efforts involve addressing deep-seated gender norms and cultural biases that may impede women’s participation (Mudege et al., 2016). In Brazil, higher education institutions have introduced outreach programs to integrate refugees into society, promote education, and reduce inequalities through collaboration with the government and community stakeholders (Finatto et al., 2023a). Additionally, extension programs should adopt a dual-focus approach that targets both internal program planners and external participants. This strategy includes providing implicit bias training for program planners, developing culturally relevant curricula for participants, and fostering the creation of antiracist and inclusive programs (Chazdon et al., 2020). Higher education institutions often encounter political and logistical challenges that impede the establishment of equitable, sustainable community partnerships. These obstacles are particularly pronounced when institutions aim to maintain a genuine commitment to community-guided relationships (Goodman et al., 2023), which is required in a community extension program partnership. In the Philippines, examining GEDI challenges and opportunities in community extension programs can be considered an under-explored domain of interest. In the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Index, the Philippines ranked 92nd out of 167 countries. The country’s progress in SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 5 (Gender Equality) remains concerning, as both are classified under the status of “Significant challenges” and are described as “stagnating” (Sustainable Development Report, 2024). Thus, this study investigated the mainstreaming of GEDI principles into community extension programs carried out by a university as a case study, highlighting the extent of implementation, challenges, and opportunities. This study seeks to answer the following research questions:

1. What are faculty members’ perceptions of the evaluation measures for GEDI implementation in Y University’s Community Extension Programs?

2. What are the key challenges faced by Y University in achieving the GEDI in their community extension programs?

3. What opportunities exist to enhance GEDI integration within community extension programs at Y university?

Literature review

GEDI practices in community extension

Higher education institutions actively implement gender equality training programs for students by incorporating methods such as didactic teaching, collaborative projects, site visits, case studies, and coaching. These initiatives aim to promote gender equality from the start of students’ academic journeys (Condron et al., 2023b). However, significant barriers hinder its successful implementation, despite the increasing emphasis on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) in higher education. This challenge is particularly evident in extension education, where a systematic examination of these barriers is essential to develop effective strategies (Diaz et al., 2023). To advance social inclusion, educators and administrators must recognize the impact of group dynamics and address school practices that may inadvertently segregate students. Proactive measures, including built-in prevention and tailored intervention strategies, are recommended to enhance social inclusion (Juvonen et al., 2019). These efforts underscore the multifaceted approaches that higher education institutions adopt to foster gender equality, diversity, and social inclusion, both within academic settings and through community extension initiatives.

Challenges to achieving GEDI in the community extension program

The implementation of community extension programs in higher education to advance gender equality, diversity, and inclusion encounters several challenges that can be grouped into structural, cultural, and operational barriers. Structural inequities pose significant obstacles, especially for women of color, who face compounded challenges owing to their intersectional identities. These inequities limit their recruitment, retention, and advancement in academic roles (Kincade, 2024). Additionally, many diversity and inclusion policies focus narrowly on single identity categories rather than adopting intersectional approaches, which results in insufficient support for individuals experiencing multiple forms of discrimination, such as those based on gender, race, and social Make it a (Fernandez et al., 2024). Furthermore, community colleges and other institutions often lack adequate resources and tailored support systems, which hinders the effective implementation of gender equity programs (Carll et al., 2023). Despite ongoing efforts to foster inclusion, many universities fail to establish inclusive processes and cultures that provide equal opportunities for all, regardless of gender, ethnicity, or other identities (Siri et al., 2022).

Opportunities for GEDI integration in the community extension program

Community extension programmes present valuable opportunities to advance gender equality, diversity, and inclusion through various strategies and initiatives to foster an inclusive environment. Tools such as the Welcoming Communities Assessment can help communities evaluate their current inclusivity levels and identify areas for improvement. This assessment focuses on the inclusivity of immigrants, refugees, and people of color, providing a foundation for actionable strategies (Chazdon et al., 2020). Promoting women’s participation in leadership roles in community extension programs is another critical strategy for achieving gender equality. This can be achieved by creating supportive networks, offering training, and implementing policies that enable women to engage in decision-making (Capello et al., 2021; Cassidy, 2017). Higher education institutions also play a pivotal role in promoting inclusion through outreach programs that provide education and support to marginalized groups, including refugees, thereby reducing inequalities and promoting lifelong learning opportunities (Finatto et al., 2023b). Additionally, diversity training and continuous learning opportunities for staff and volunteers can foster respect for diversity and enhance inclusive practices (Shan et al., 2021). Data show that females and African-Americans have higher rates of community service participation, and extension programs can leverage this by targeting these subgroups for volunteer recruitment further to enrich diversity and inclusion in community service activities (Smith, 2005).

Theoretical underpinning

Intersectionality theory serves as an essential analytical framework that examines the interplay between overlapping social identities and systemic structures of oppression, shaping individual experiences, and influencing broader societal dynamics. Originating from the contributions of black feminist scholarship, especially the perspectives of black women who express their unique experiences with racism, sexism, and class-based marginalization, the theory highlights the intertwined characteristics of social hierarchies (Robinson, 2016, 2018). This idea emphasizes the understanding that individuals manage various concurrent social identities such as race, gender, socioeconomic class, and sexuality, which are influenced by and function within established power structures (Few-Demo et al., 2022; Wyatt et al., 2022). The interplay of these identities is further understood through interconnected systems of oppression, which encompass institutionalized racism, patriarchal norms, capitalist exploitation, and various structural inequities that sustain inequality (Robinson, 2018; Wyatt et al., 2022). Furthermore, intersectionality highlights the complex interactions of power and privilege, examining how these elements shape access to societal resources, affect experiences of discrimination, and impact relational dynamics among social groups (Mak, 2025; Sabik, 2021). By highlighting these complexities, this theory offers a detailed perspective for comprehending the intricate dynamics of marginalization and resistance. In this study, we investigated how GEDI concepts are integrated into community extension programs, focusing on a case study at Y University. The extensionist navigates multiple intersectionalities while managing various community extension programs that serve the community, effectively translating theory into practice.

Research context

In the Philippines, community extension programs are commonly referred to as extensions. This term represents one of the primary functions of higher education institutions, alongside research and production. In State Universities and Colleges (SUCs), extension is considered a primary criterion for promotion alongside research, professional development, and instruction (Department of Budget and Management and Commission on Higher Education, 2022). Extension according to policy documents from the Philippine Commission on Higher Education states:

Extension refers to the act of communicating, persuading, and helping specific sectors or target clienteles (as distinguished from those enrolled in formal degree programs and course offerings) to enable them to effectively improve production, community, institutions, and quality of life (CHED Memo No. 8, 2008, p. 2).

The commission mandates that the university adhere to its compliance as part of the accomplishment report. An extension program or project is characterized by a series of activities designed to disseminate knowledge or technology, or to offer services to the community in alignment with the programs available. These community extension programs are carried out not as an academic requirement but as an outreach initiative aimed at enhancing the community’s quality of life (CHED Memo No. 8, 2008; CHED Memo No. 35, 2010).

Moreover, in the Philippine context, community extension programs are diverse and address a wide range of socioeconomic and health needs in local communities. The Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP) implements programs aimed at improving the socioeconomic status of communities by utilizing the education and skills of household members while tackling issues such as unemployment and the prevalence of out-of-school youth (Salud-Payumo et al., 2020). Similarly, the University of the Philippines Mindanao employs the “Livelihood Improvement through Facilitated Extension” (LIFE) Model, which focuses on agricultural entrepreneurship in conflict-vulnerable areas, leading to significant improvements in farmers’ incomes and food security (Sigue et al., 2021). In Central Luzon, Project “Lusog-Linang” emphasizes health capacity building in underserved communities, addressing healthcare accessibility, food security, and environmental sanitation (Sumile et al., 2024). Meanwhile, the College of Teacher Education at Nueva Vizcaya State University (NVSU) runs extension services, such as Projects HELP and KKK (Kumikitang Pangkabuhayan or Livelihood Program) which have effectively engaged both implementers and beneficiaries. However, some challenges, such as irregular consultations, have been noted (Corpuz et al., 2022). Despite these successes, many programs face obstacles related to funding, resource allocation, and the need for sustainable partnerships (Opina-Tan and Hamoy, 2024). Effective community engagement and participation remain critical to the success of these initiatives.

Methodology

Research design

A qualitative case study is conducted to address these issues. Case studies offer deeper knowledge of complex real-life situations than other methodologies (Yin, 2018). Case studies are versatile; therefore, researchers can adapt their approaches. Unlike other qualitative methods, flexibility enables creativity in research design (Merriam, 2010). Case studies legitimize and empower people by stressing their perspectives and experiences. They comprehensively demonstrate organizational conflict and good work (Payne et al., 2007). This case study investigates the mainstreaming of GEDI principles into community extension programs conducted by a university, highlighting the extent of implementation, challenges, and opportunities.

Research locale and participants

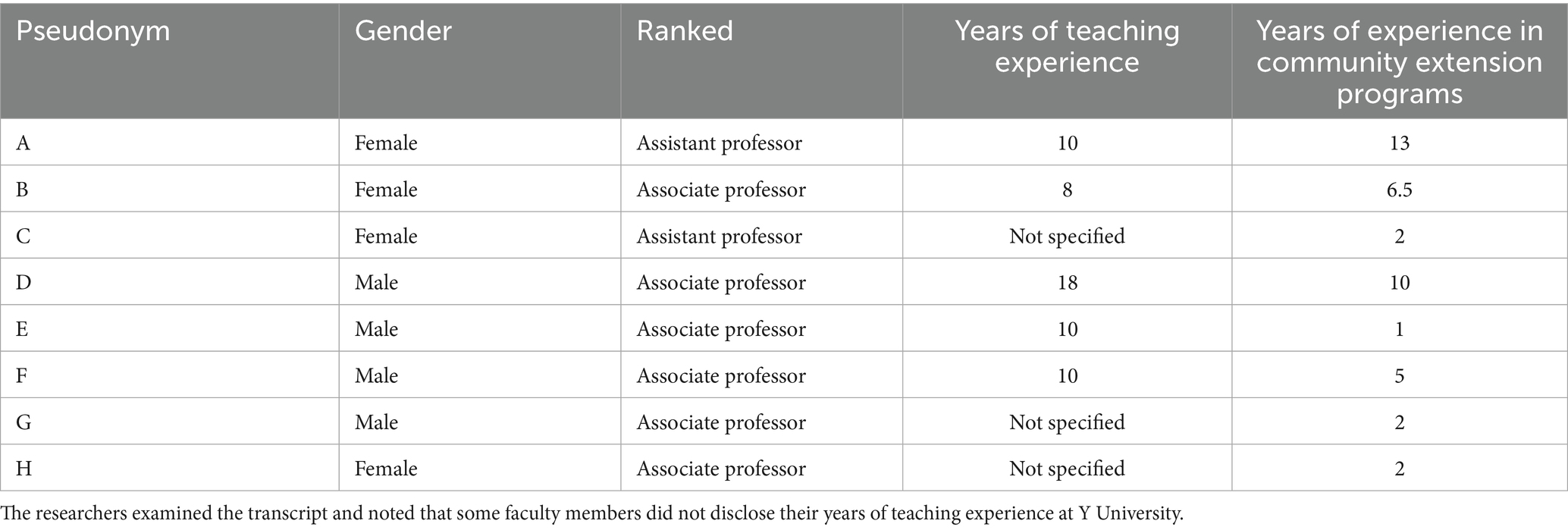

This study was conducted across five campuses at the Y University. Y University has multiple campuses and satellite campuses across the Philippines. The study invited eight faculty members working in a community extension program at five campuses of Y University. Participants were identified as those invited to participate in the interviews. The only requirement for selection was that faculty members participate directly in the university’s extension program. The participants were tenured faculty members holding academic positions ranging from assistant professors (n = 2) to associate professors (n = 6), aged 30–45 years (Table 1).

The researchers peer-reviewed the interview questions with three extension program professionals and an evaluation specialist from the same TEI. The validated semi-structured interview guide was evaluated by two TEI faculty members who administered extension programs to improve the questions and data collection. The semi-structured interview guide asked five main questions regarding community extension, program evaluation, GEDI, implementation challenges, and opportunities.

Data collection and analysis

Before data collection, the first author’s university approved this study (REC code 01262023–037). All participants provided written informed consent and were informed of the study goals and the interview method. Due to the participants’ busy schedules and the challenge of organizing multiple interviews and follow-ups, in-depth online interviews were conducted. Each session lasted between 45 and 60 min. All audio and transcription data were securely saved on the researchers’ devices. Integration themes were identified using an inductive thematic analysis of the interview data. Semi-structured interview guide themes included GEDI component concepts, extension operation success criteria, and new trends or concerns. The researchers wrote the report clearly and precisely, using advanced grammar and language-enhancing technology.

Results

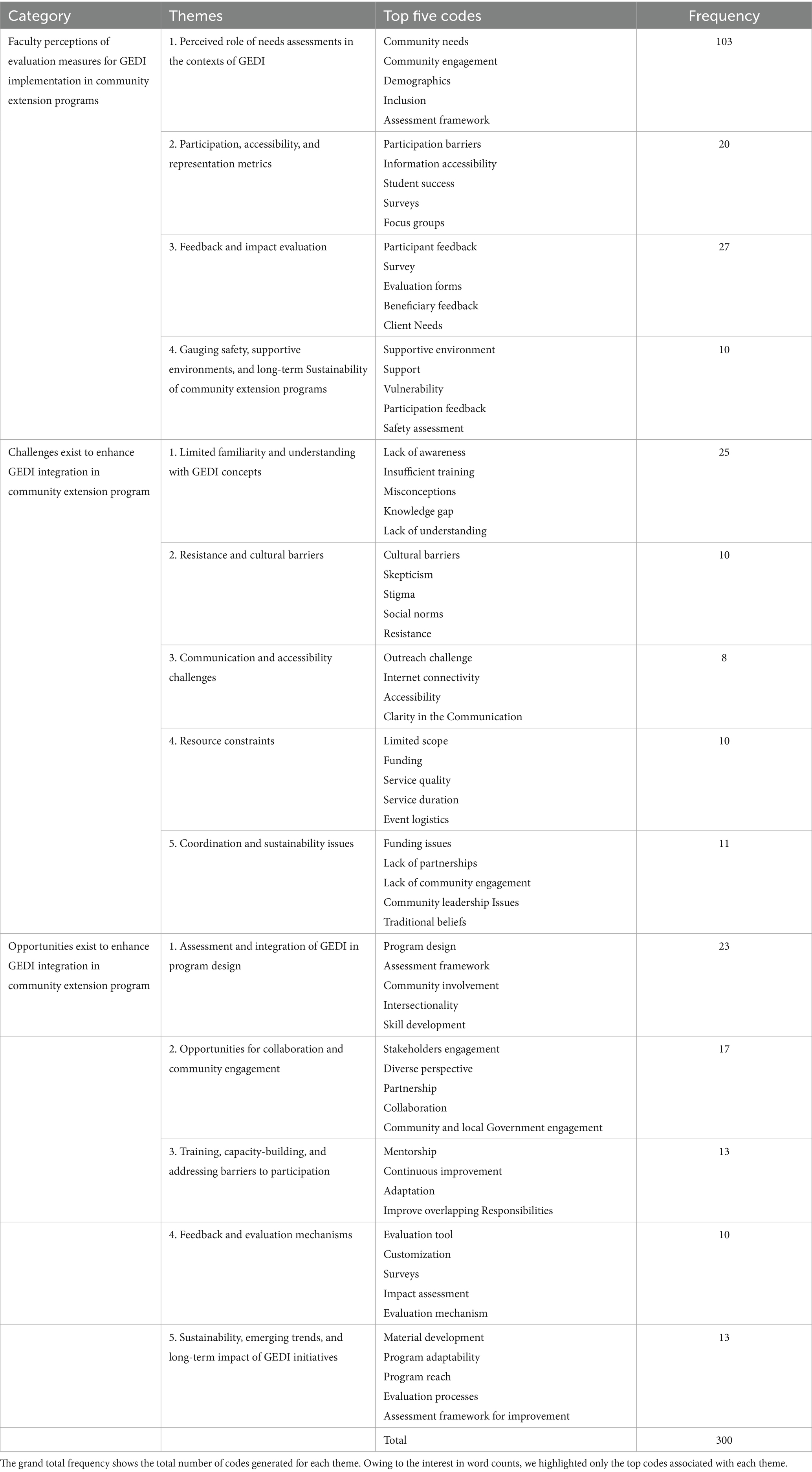

Table 2 provides a summary of the themes, codes, and frequencies associated with the evaluation, challenges, and opportunities to integrate the GEDI into the community extension program. The evaluation of success places a significant emphasis on community needs assessment (103 codes), highlighting the focus on tailoring programs to marginalized groups. Participation metrics (20 codes) and feedback (27 codes) further underscored the necessity of equitable engagement. Additionally, creating a safe and supportive environment (10 codes) and assessing long-term sustainability have emerged as critical, yet less frequently cited, components of program effectiveness.

Regarding challenges, systemic barriers, such as limited familiarity with GEDI concepts (25 codes) and cultural resistance (10 codes), reflect gaps in awareness and issues related to social norms. Communication barriers (8 codes), including language differences and accessibility issues for persons with disabilities, and resource constraints (10 codes), such as funding shortages, were noted. Coordination and sustainability challenges (11 codes), including a lack of partnership and community engagement, further complicate program continuity (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of themes on evaluation, challenges and opportunities of community extension programs.

Opportunities focus on integrating the GEDI program design (23 codes) with emphasis on intersectionality and skill development. Stakeholder collaboration (17 codes), particularly with local governments and non-governmental organizations, is crucial for resource mobilization and relevance. Training and capacity building (13 codes) address knowledge gaps, whereas feedback mechanisms (10 codes) and sustainability strategies (13 codes), such as an adaptability framework and material development, aim to ensure lasting impacts.

What are faculty members’ perceptions of the evaluation measures for GEDI implementation in Y University’s Community Extension Programs?

Perceived role of needs assessments in the contexts of GEDI

Conducting thorough needs assessments is essential for identifying the community’s specific needs regarding the GEDI. This ensures that programs are tailored to address the unique challenges faced by marginalized groups and that their voices are heard. Assessing the level of awareness and understanding of the GEDI concepts among community members is essential for evaluating the effectiveness of educational initiatives. Some professors shared the following points:

We still really need to conduct a needs analysis, interim evaluations or assessments, and an impact analysis.

There should already be a GEDI (Gender Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion) component in our needs assessment to address their needs effectively.

We should consider safety and wellbeing by measuring the extent to which the program creates a safe and supportive environment.

Participation, accessibility, and representation metrics

Measuring the level of participation and representation of diverse groups in community extension activities is crucial for evaluating program inclusivity. This includes assessing whether marginalized groups are adequately represented and engaged. Evaluating the accessibility of program locations, materials, and activities is crucial to ensure that all community members, including those with disabilities, can participate fully.

Were there many participants? Was the representation equal?

We need to assess the rate of representation and participation.

We also need to assess the accessibility of program locations, materials, and activities.

Feedback and impact evaluation

Gathering both quantitative and qualitative feedback from participants and evaluating the impact of community extension programs on their lives are vital for understanding the effectiveness of GEDI initiatives. This feedback could inform future program improvements and adaptations. Similarly, evaluating the impact of community extension programs on the lives of participants, particularly in terms of empowerment and social change, is a key indicator of success.

By getting qualitative feedback, we can determine insights into lived experiences.

It is important to have qualitative questions so that students can express what they really want to say.

This qualitative feedback can contribute to assessing the impact and effectiveness.

Gauging safety, supportive environments, and long-term sustainability of community extension programs

Measuring the extent to which programmes create a safe and supportive environment for all participants is essential for fostering inclusion and preventing harassment or discrimination. This includes assessing the overall wellbeing of participants before, during, and after the execution of programs in the community. Likewise, to ensure that GEDI initiatives have enduring effects, assessing the long-term sustainability of programs is vital, as ongoing support and engagement from community members help maintain interest and participation. Some of the participants mentioned:

We should consider safety and wellbeing by measuring the extent to which the program creates a safe and supportive environment.

Success is very evident when GEDI initiatives create lasting impacts that endure beyond the lifespan of the program.

We need to monitor the use of inclusive language and communication strategies.

What are the key challenges faced by Y University in achieving the GEDI in their community extension programs?

Limited familiarity and understanding with GEDI concepts

A significant barrier is the limited familiarity and understanding of the GEDI concepts among extension workers and community members. This limitation can lead to resistance to change and hinder effective integration. Likewise, extension workers may not receive adequate training on GEDI principles, affecting their ability to effectively implement inclusive practices. Participants shared the following:

As I mentioned, familiarity with these various constructs is one of the challenges.

We need to ensure that extensionists have full knowledge of GEDI before entering the community.

Resistance and cultural barriers

Cultural attitudes and resistance to change are significant barriers to accepting and implementing GEDI. Established social norms can discourage participation and hinder progress toward gender equality and inclusion. Change often results in resistance, especially when stakeholders have established ways of doing things. This resistance could impede the adoption of new practices that promote gender equality and inclusion. Some professors noted the following:

Any form of change will meet some level of resistance since most of the stakeholders have already constructed their own way of doing things.

Some community members may not recognize the importance of GEDI.

There is a need to orient them about GEDI before we proceed.

Communication and accessibility challenges

Language barriers and varying literacy levels among community members create significant challenges in assessing needs and effectively implementing programs. Accessibility issues also pose significant concerns, particularly for disabled individuals. The participants pointed out that physical accessibility, such as transportation and venue suitability, often prevents full participation. Moreover, inadequate needs assessments that specifically address GEDI components can lead to programs that do not fully meet the needs of marginalized groups. Remarkable comments from the participants

There is a language barrier and literacy issues among our beneficiaries.

Finding an appropriate extension activities venue/location that is accessible, especially for Persons with Disability (PWD) participants, can be difficult.

If there are no means to transport people with disabilities, they cannot participate.

Resource constraints

Budgetary limitations and the availability of resources for training materials and venues are critical challenges restricting the scope and effectiveness of GEDI initiatives. Without adequate funding and resources, implementing comprehensive programs is difficult. The lack of comprehensive needs assessments that specifically address GEDI components can lead to programs that do not fully meet the needs of marginalized groups. Participants shared the following:

We need to look for another resource or funding.

Budgetary concerns specific to training materials and customized training venues

Financial aspects are crucial for the successful implementation of GEDI initiatives.

Coordination and sustainability issues

Coordinating schedules among various stakeholders, including community members and local government units, can be challenging and can lead to difficulties in planning and executing extension activities. Likewise, ensuring the sustainability of GEDI initiatives is vital for creating lasting effects on the community. As such, ongoing support and engagement from community members are necessary to maintain interest in and participation in extension activities. The participants believed that

Success is evident when GEDI initiatives create lasting impacts.

We need to maintain their interest while delivering the program.

What opportunities exist to enhance GEDI integration within community extension programs at Y University?

Assessment and integration of GEDI in program design

Conducting comprehensive needs assessments and integrating GEDI components into program design are essential for ensuring that community extension activities are relevant and inclusive. This approach allows for the identification of specific needs and tailoring of programs to address the unique challenges faced by marginalized groups. Integrating GEDI components into the design of community extension programs ensures that all activities are inclusive and equitable, thus addressing the specific needs of diverse groups. Some professors commented the following:

It is necessary to conduct needs analysis, interim evaluations or assessments, and impact analysis.

There should already be a component of the GEDI in our needs assessment so that we can effectively address their needs.

We can ensure that all our activities align with gender equality if they are firmly anchored, of course, on the needs assessment

Opportunities for collaboration and community engagement

Collaborating with local organizations and stakeholders enhances the reach and impact of GEDI initiatives. Engaging with community members provides additional resources, support, and insights that are crucial for implementing inclusive programs. Leveraging the existing resources and expertise within an institution can enhance the effectiveness of GEDI initiatives. Collaborating with faculty members with specialized knowledge can lead to more impactful programs. Participants shared the following:

We look for another partner, which is Keystone, to help us facilitate and assess the participants.

Collaboration with barangay officials is essential.

We need to work collaboratively, not just the university but even the LGU and other agencies.

Training, capacity-building, and addressing barriers to participation

Providing training and capacity-building initiatives for extension workers on GEDI principles is vital for equipping them with the knowledge and skills necessary to effectively implement inclusive practices. These learning opportunities can further enhance students’ understanding and ability to address the needs of diverse community members. By identifying and addressing barriers to participation, such as language and accessibility issues, all community members are provided opportunities to engage in community extension activities. The participants noted the following.

Capability training and thorough consultation are needed.

We need to provide appropriate training programs for extension workers.

Training is essential to ensure that extensionists have full knowledge of GEDI.

Feedback and evaluation mechanisms

Establishing mechanisms for gathering qualitative feedback from participants and stakeholders is essential for assessing the impact and effectiveness of the GEDI initiatives. This feedback provides valuable insights into the lived experiences of community members and program improvements. Ensuring that community extension programs create safe and supportive environments for all participants is vital to fostering inclusion and preventing harassment or discrimination. Some professors believe that:

By getting qualitative feedback, we can determine insights into lived experiences.

This qualitative feedback can contribute to assessing the impact and effectiveness.

We need to monitor the use of inclusive language and communication strategies.

Sustainability, emerging trends, and long-term impact of GEDI initiatives

Ensuring the sustainability of GEDI initiatives is crucial for creating lasting effects on the community. Ongoing support and engagement from community members are necessary to maintain interest in and participation in extension activities. Participants noted the importance of considering emerging trends in the GEDI in the design of assessment frameworks, such as the inclusion of marginalized groups. This reflects growing awareness of the need to broaden the scope of GEDI initiatives. Participants shared the following:

Success is evident when GEDI initiatives create lasting impacts.

We need to maintain their interest while delivering the program.

The transformation is to make our partners self-directed.

Discussion

This case study investigates the mainstreaming of GEDI principles into community extension programs conducted by Y University, highlighting the extent of implementation, challenges, and opportunities.

The findings indicate that success can be gauged by evaluating needs, participation levels, and the representation of marginalized groups, along with the inclusivity of program environments. Feedback, impact evaluation, and sustainability metrics provide valuable insights into the program effectiveness and long-term outcomes. This study confirmed that Claude Bennett’s hierarchy of evidence remains relevant for assessing effectiveness (Bennett, 1975; Rockwell and Bennett, 2004). However, the findings also underscore the importance of incorporating sustainability metrics to include the GEDI in community extension programs. Universities have adopted the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment, and Rating System (STARS), a comprehensive framework designed to evaluate sustainability performance in higher education institutions. STARS enables institutional comparisons by offering universally applicable metrics (Lang, 2015; Maragakis et al., 2017). Another essential tool for measuring sustainability is sustainability indicators. A proposed set of 57 indicators allows for the assessment of sustainable performance across various areas within higher education institutions, including the academic community, administrative staff, operations and services, teaching, research, and extension programs (Da Silva and De Azevedo Almeida, 2019). Together, these tools provide a robust approach for understanding and enhancing sustainability efforts in higher education.

Key challenges include limited familiarity with GEDI principles, cultural resistance, and accessibility issues, which hinder participation and effectiveness. Resource constraints and coordination challenges further complicate the implementation of GEDI-focused programmes. As noted by Samuel et al. (2024) and Siri et al. (2022), many institutions and individuals may not fully grasp the importance and benefits of gender equality, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), leading to the resistance or superficial application of EDI policies. Ineffective communication strategies exacerbate this issue because unclear or inconsistent messaging can impede the dissemination and acceptance of EDI practices. To ensure that all stakeholders understand and actively support EDI initiatives, communication must be clear, consistent, and inclusive (Siri et al., 2022; Yahchouchi and Rotabi, 2023). Furthermore, the success of EDI efforts is often undermined by poor coordination among departments and stakeholders within an institution. This fragmentation results in inconsistent and ineffective policy implementation, thereby diminishing the overall impact (Aksay Aksezer et al., 2023; Siri et al., 2022). Additionally, declining budget revenues and limited resources are common issues that restrict the scope and impact of extension programmes (Filinson and Raimondo, 2019; Kale Monk et al., 2019).

Another interesting finding of the study is that the opportunities for the GEDI to enter community extension programs lie in conducting comprehensive needs assessments, fostering stakeholder collaboration, and providing targeted training for extensionists. Feedback mechanisms and a focus on sustainability drive continuous improvement and foster long-term impacts. Chazdon et al. (2020) highlighted that tools like the Welcoming Communities Assessment are crucial for evaluating a community’s readiness for inclusion, offering a foundational understanding of inclusivity for immigrants, refugees, and people of color. For example, there is an urgent need for gender-responsive policies, as demonstrated by Fiji’s approach to nutrition and health-related strategies, which can be adapted to other contexts to ensure that gender considerations are both actionable and inclusive (McKenzie et al., 2022). Another example is the use of the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) model, which enhances engagement and inclusivity by positioning community participants as peer experts, thereby sharing power and authority in collaborative efforts (Goodman et al., 2023). Programs that focus on capacity building through grassroots participation and practical education training initiatives have shown moderate success in improving community knowledge, attitudes, and lifestyles (Llenares and Deocaris, 2018). Furthermore, actively involving community members in feedback processes ensures that extension programs remain responsive to their needs and adapt to greater inclusivity and effectiveness (Salud-Payumo et al., 2020).

Implications for policy and practice

The following measures are suggested to improve the integration of the GEDI into community extension initiatives.

• Enhance needs assessment and program design: conducting GEDI-oriented needs assessments to identify underrepresented population issues. These evaluations can be used to create inclusive activities that meet the needs of all community members, ensuring accessibility and engagement.

• Enhance capacity and deliver training: implement GEDI-specific training for professors and extension staff. Give them skills to implement inclusive practices and foster community collaboration.

• Facilitate stakeholder collaboration: partners with local governments, community leaders, and NGOs to develop and implement programs. This technique mobilizes resources and aligns programmes with local needs.

• Implement comprehensive monitoring and evaluation frameworks: set GEDI-specific indicators to evaluate program efficacy. Measures such as participation rates, community involvement, and lasting benefits to marginalized groups to improve program processes.

• Promote sustainability and continuous impact: develop sustainable programs that improve local circumstances to continue GEDI independently. Utilizing emerging trends and novel methods to meet local needs.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. One significant limitation is the reliance on data from a small group of faculty members at a single university with five campuses in the Philippines. Consequently, future researchers might consider broadening the scope to include other universities to determine whether the experiences highlighted in the findings are consistent. Additionally, future research should focus on developing sustainability metrics for GEDI integration in community extension programs, extending the study to various institutional contexts, and examining the long-term impacts of GEDI initiatives in community programs. Therefore, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to all state universities and colleges in the Philippines.

Conclusion

This study investigated the challenges and opportunities faced by the GEDI principles in community extension programs in higher education. Based on the findings, the community extension programs at Y University demonstrated moderate success in integrating GEDI through needs assessment, participation metrics, and impact evaluation, but faced sustainability gaps. Challenges include limited familiarity with the GEDI, cultural resistance, and resource constraints. Opportunities for improvement lie in integrating GEDI program design, stakeholder collaboration, and capacity-building initiatives. Future studies should focus on developing a sustainable metric specifically for GEDI in community extension programs to help scholars and practitioners better implement programs aligned with gender equality, diversity, and inclusion.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Philippine Normal University Research Ethics Committee (PNU-REC) under REC Code 01262023-037. Informed consent was obtained, and participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were ensured. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

RR-H: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ACB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ABB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. IZ: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Resources. ZB: Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft. JB: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft. MB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. CD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors take full responsibility for using Grammarly and Quillbot solely for language correction in this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aksay Aksezer, E., Demiryontar, B., Dorrity, C., and Mescoli, E. (2023). International student experiences in three superdiverse higher education institutions: institutional policies and intersectionalities. Soc. Sci. 12:544. doi: 10.3390/socsci12100544

Belluigi, D. Z., Arday, J., and O’Keeffe, J. (2024). Data snapshots of the access and participation of ‘women’ academics in UK universities: questioning continued gendered, racialised and geopolitical inequalities. Br. Educ. Res. J. 50, 2684–2711. doi: 10.1002/berj.4047

Campanini Vilhena, F., Bencivenga, R., López Belloso, M., Leone, C., and Celeste Taramasso, A. (2024). Participatory strategies to integrate gender+ into teaching and research. Int. Conf. Gender Res. 7, 71–78. doi: 10.34190/icgr.7.1.2233

Capello, M. A., Robinson-Marras, C., Dubay, K., Tulsidas, H., and Griffiths, C. (2021). “Progressing the UN SDGs: focusing on women and diversity in resource management brings benefits to all,” in SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, D031S047R005.

Carll, E., Litzler, E., Achenbach, G., Binowski, N., Brawner, C. E., and Ward, J. L. H. (2023). “Community college computing programs’ unique contexts for promoting gender equity,” in 2023 Collaborative Network for Computing and Engineering Diversity (CoNECD).

Chazdon, S., Hawker, J., Hayes, B., Linscheid, N., O’Brien, N., and Spanier, T. (2020). Assessing community readiness to engage in diversity and inclusion efforts. J. Ext. 58, 1–7. doi: 10.34068/joe.58.06.24

CHED Memo No. 35. (2010). Accomplishment and submission of the self-survey forms of state universities and colleges (SUCs) leveling. Commission on Higher Education. Available online at: https://ched.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CMO-No.35-s2010.pdf

CHED Memo No. 8. (2008). Guidelines for the CHED outstanding extension program award. Commission on Higher Education. Available online at: https://ched.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CMO-No.08-s2008.pdf (Accessed November 14, 2024).

Condron, C., Power, M., Mathew, M., and Lucey, S. M. (2023). Gender equality training for students in higher education: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Res. Protocols 12:e44584. doi: 10.2196/44584

Corpuz, D. A., Time, M. J. C., and Afalla, B. T. (2022). Empowering the community through the extension services of a teacher education institution in the Philippines. Cogent Educ. 9:2149225. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2149225

Da Silva, G. S., and De Azevedo Almeida, L. (2019). Sustainability indicators for higher education institutions: a proposal based on the literature review. Rev. Gestão Ambient. Sustent. 8, 123–144. doi: 10.5585/geas.v8i1.13767

Department of Budget and Management and Commission on Higher Education. (2022). Joint Circular No. 3 series of 2022. Available online at: https://www.dbm.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/Issuances/2022/Joint-Circular/DBM-JC-No-3-s-2022-9th-cycle-NBC-461-with-Annexes.pdf

Diaz, J., Gusto, C., Narine, L., Jayaratne, K. S. U., and Silvert, C. (2023). Toward diversity, equity, and inclusion outreach and engagement in extension education: expert consensus on barriers and strategies. J. Ext. 61:21. doi: 10.34068/joe.61.01.21

Fernandez, D., Orazzo, E., Fry, E., McMain, A., Ryan, M. K., Wong, C. Y., et al. (2024). Gender and social class inequalities in higher education: intersectional reflections on a workshop experience. Front. Psychol. 14:1235065. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1235065

Few-Demo, A. L., Hunter, A. G., and Muruthi, B. A. (2022). “Intersectionality theory: a critical theory to push family science forward” in Of fam. Theor. And methodol: A dyn. Approach. ed. Sourceb (Cham: Springer), 433–452.

Filinson, R., and Raimondo, M. (2019). Promoting age-friendliness: one college’s “town and gown” approach to fostering community-based and campus-wide initiatives for inclusiveness. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 40, 307–321. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2019.1579715

Finatto, C. P., Aguiar Dutra, A. R., Gomes Da Silva, C., Nunes, N. A., and Guerra, J. B. S. O. D. A. (2023). The role of universities in the inclusion of refugees in higher education and in society from the perspective of the SDGS. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 24, 742–761. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-07-2021-0275

Goodman, H. P., Yow, R., Standberry-Wallace, M., Dekom, R., Harper, M., Nieto Gomez, A., et al. (2023). Perspectives from community partnerships in three diverse higher education contexts. Gateways Int. J. Community Res. Engagem. 16:8693. doi: 10.5130/ijcre.v16i2.8693

Gururaj, S., Somers, P., Fry, J., Watson, D., Cicero, F., Morosini, M., et al. (2021). Affirmative action policy: inclusion, exclusion, and the global public good. Policy Futures Educ. 19, 63–83. doi: 10.1177/1478210320940139

Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., and Smith, D. S. (2019). Promoting social inclusion in educational settings: challenges and opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 54, 250–270. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645

Kale Monk, J., Benson, J. J., and Bordere, T. C. (2019). Public scholarship: a tool for strengthening relationships across extension, campus, and community. J. Ext. 57:9. doi: 10.34068/joe.57.03.09

Kincade, L. L. (2024). “A social-ecological model for racially diverse women in higher education: organizational support and affirmative action” in Advances in higher education and professional development. ed. R. A. Abu-Lughod (London: IGI Global), 87–112.

Lang, T. (2015). Campus sustainability initiatives and performance: do they correlate? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 16, 474–490. doi: 10.1108/IJSHE-01-2014-0009

Llenares, I. I., and Deocaris, C. C. (2018). Measuring the impact of an academe community extension program in the Philippines. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 15, 35–55. doi: 10.32890/mjli2018.15.1.2

Mak, C. (2025). “Intersectionality” in Issues of Equity: Key concepts in qualitative methods. ed. J. C. Báez (New York, NY: Taylor and Francis), 87–90.

Maragakis, A., Van Den Dobbelsteen, A., and Erlenbach, A. (2017). Analysis of STARS as a sustainability assessment system universally usable in higher education. A+BE Architect. Built Environ. 3, 69–83.

McKenzie, B. L., Waqa, G., Mounsey, S., Johnson, C., Woodward, M., Buse, K., et al. (2022). Incorporating a gender lens into nutrition and health-related policies in Fiji: analysis of policies and stakeholder perspectives. Int. J. Equity Health 21:1745. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01745-x

Merriam, S. B. (2010). “Qualitative case studies” in International encyclopedia of education. eds. P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw (Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd), 456–462.

Mudege, N. N., Chevo, T., Nyekanyeka, T., Kapalasa, E., and Demo, P. (2016). Gender norms and access to extension services and training among potato farmers in Dedza and Ntcheu in Malawi. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 22, 291–305. doi: 10.1080/1389224X.2015.1038282

Opina-Tan, L. A., and Hamoy, G. L. (2024). Taking on the challenge: a case study on a community health club for noncommunicable disease control. Acta Med. Philipp. 58:8101. doi: 10.47895/amp.v58i13.8101

Payne, S., Field, D., Rolls, L., Hawker, S., and Kerr, C. (2007). Case study research methods in end-of-life care: reflections on three studies. J. Adv. Nurs. 58, 236–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04215.x

Robinson, Z. F. (2016). “Intersectionality” in Handbook of Contemporary Sociological Theory. eds. D. N. Kluttz, N. Fligstein, and S. Abrutyn (Cham: Springer Science and Business Media B.V), 477–499.

Robinson, Z. F. (2018). “Intersectionality and gender theory” in Handbook of Contemporary Sociological Theory. eds. D. N. Kluttz, N. Fligstein, and S. Abrutyn (Cham: Springer Science and Business Media B.V), 69–80.

Rockwell, K., and Bennett, C. (2004). Targeting outcomes of programs: a hierarchy for targeting outcomes and evaluating their achievement outcomes and evaluating their achievement. Lincoln: University of Nebraska - Lincoln.

Sabik, N. J. (2021). The intersectionality toolbox: a resource for teaching and applying an intersectional lens in public health. Front. Public Health 9:772301. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.772301

Salud-Payumo, C., Monsura, M. P., Magpantay, M., Sanguyo, E., and Guillo, A. C. (2020). Socioeconomic profiling of communities surrounding polytechnic University of the Philippines as basis of extension programs. Ann. Trop. Med. Public Health 23:231328. doi: 10.36295/ASRO.2020.231328

Samuel, H. S., Etim, E. E., Shinggu, J. P., Nweke-Maraizu, U., and Bako, B. (2024). “Diversity and inclusion in higher education” in Building Resiliency in Higher Education: Globalization, Digital Skills, and Student Wellness: Globalization, Digital Skills, and Student Wellness. ed. M. Kayyali (New York, NY: IGI Global), 239–248.

Shan, H., Cheng, A., Peikazadi, N., and Kim, Y. (2021). Fostering diversity work as a process of lifelong learning: a partnership case study with an immigrant services organisation. Int. Rev. Educ. 67, 771–790. doi: 10.1007/s11159-021-09929-3

Sigue, K. S., Bayogan, E. V., Lozada, H. P., Fuentes, A. Y., Orbeta, M. O., and Ignacio, J. D. (2021). Roles of site facilitators in improving farm income by vegetable growing in South Cotabato and Maguindanao, Philippines using the livelihood improvement through facilitated extension (LIFE) model. Acta Hortic. 1312, 531–538. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2021.1312.75

Siri, A., Leone, C., and Bencivenga, R. (2022). Equality, diversity, and inclusion strategies adopted in a European university Alliance to facilitate the higher education-to-work transition. Societies 12:140. doi: 10.3390/soc12050140

Smith, T. J. (2005). Ethnic and gender differences in community service participation among working adults. J. Ext. 43, 85–97. Available at: https://open.clemson.edu/joe/vol43/iss2/10

Sumile, P. D., Rn, E. F. R., Delos Santos, M. A. E., Rn, J. V. T., Hernandez, M., Rn, M. A. A., et al. (2024). “Lusog-Linang”: utilizing community-engaged research towards capacity building in health of an underserved community. Acta Med. Philipp. 58, 93–102. doi: 10.47895/amp.v58i12.9472

Sustainable Development Report. (2024). Philippines. Available online at: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/map

Wyatt, T. R., Johnson, M., and Zaidi, Z. (2022). Intersectionality: a means for centering power and oppression in research. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 27, 863–875. doi: 10.1007/s10459-022-10110-0

Yahchouchi, G., and Rotabi, S. (2023). “Inclusion and diversity” in Governance in higher education. eds. N. Azoury and G. Yahchouchi (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 33–59.

Keywords: community extension, gender equality, diversity, inclusion, sustainability, higher education, Philippines

Citation: Raton-Hibanada R, Castulo NJ, de Vera JL, Bituin AC, Barcelona AB, Zanoria IOB, Bedural ZL, Bailon JV, Buenaventura MLD and Dellomos CO (2025) Examining gender equality, diversity, and inclusion: a case study of the challenges and opportunities in community extension programs in a select philippine university. Front. Educ. 10:1583997. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1583997

Edited by:

Linda Alexander, Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH), United StatesReviewed by:

Francis Thaise A. Cimene, University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, PhilippinesRanjita Islam, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Roger Rennekamp, Cooperative Extension, United States

Copyright © 2025 Raton-Hibanada, Castulo, de Vera, Bituin, Barcelona, Zanoria, Bedural, Bailon, Buenaventura and Dellomos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nilo Jayoma Castulo, bmlsb2Nhc3R1bG9AbWFpbC5ibnUuZWR1LmNu

Rowena Raton-Hibanada

Rowena Raton-Hibanada Nilo Jayoma Castulo

Nilo Jayoma Castulo Jayson L. de Vera

Jayson L. de Vera Analyn C. Bituin1,4

Analyn C. Bituin1,4 Iona Ofelia B. Zanoria

Iona Ofelia B. Zanoria James V. Bailon

James V. Bailon Ma. Laarni D. Buenaventura

Ma. Laarni D. Buenaventura