- 1Institute for Global Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 3Aceso Global Health Consultants Pte Limited, Singapore, Singapore

- 4The Migrant Health Research Group, Institute for Infection and Immunity, City St. George’s University of London, London, United Kingdom

- 5Nottingham University NHS Trust, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 6UCL GOS Institute of Child Health, University College London UCL, London, United Kingdom

- 7Collaborative Centre for Inclusion Health, London, United Kingdom

- 8Specialist Children’s and Young People’s Services, East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, United Kingdom

- 9Women and Children First, London, United Kingdom

- 10Department of Behavioural Science and Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 11Children’s Health 0-19 Service, London Borough of Newham, London, United Kingdom

- 12Tower Hamlets GP Care Group, Mile End Hospital, London, United Kingdom

- 13Global Business School for Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Background: The Nurture Early for Optimal Nutrition (NEON) programme was designed to promote equitable early childhood development by educating mothers of South Asian origin in two boroughs (Newham and Tower Hamlets) in East London on optimal feeding, care, and dental hygiene practices. The study found that the adapted Participatory Learning and Action (PLA) approach was highly acceptable and well-received by participants, with improvements in maternal confidence, infant feeding practices, and community engagement. However, gaps in specific feeding skills and challenges such as low attendance and retention rates were noted, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study conducted a cost analysis of the NEON programme and evaluated its financial sustainability.

Methods: We conducted a financial and economic costing from the provider perspective, applying a stepdown procedure to identify costs associated with the development and implementation of the NEON programme. Estimates of total and average costs per mother are presented along with affordability assessments, expressed as a proportion of the borough’s annual child development expenditure. All costs were discounted and reported in 2022 pound sterling and in 2022 international dollars.

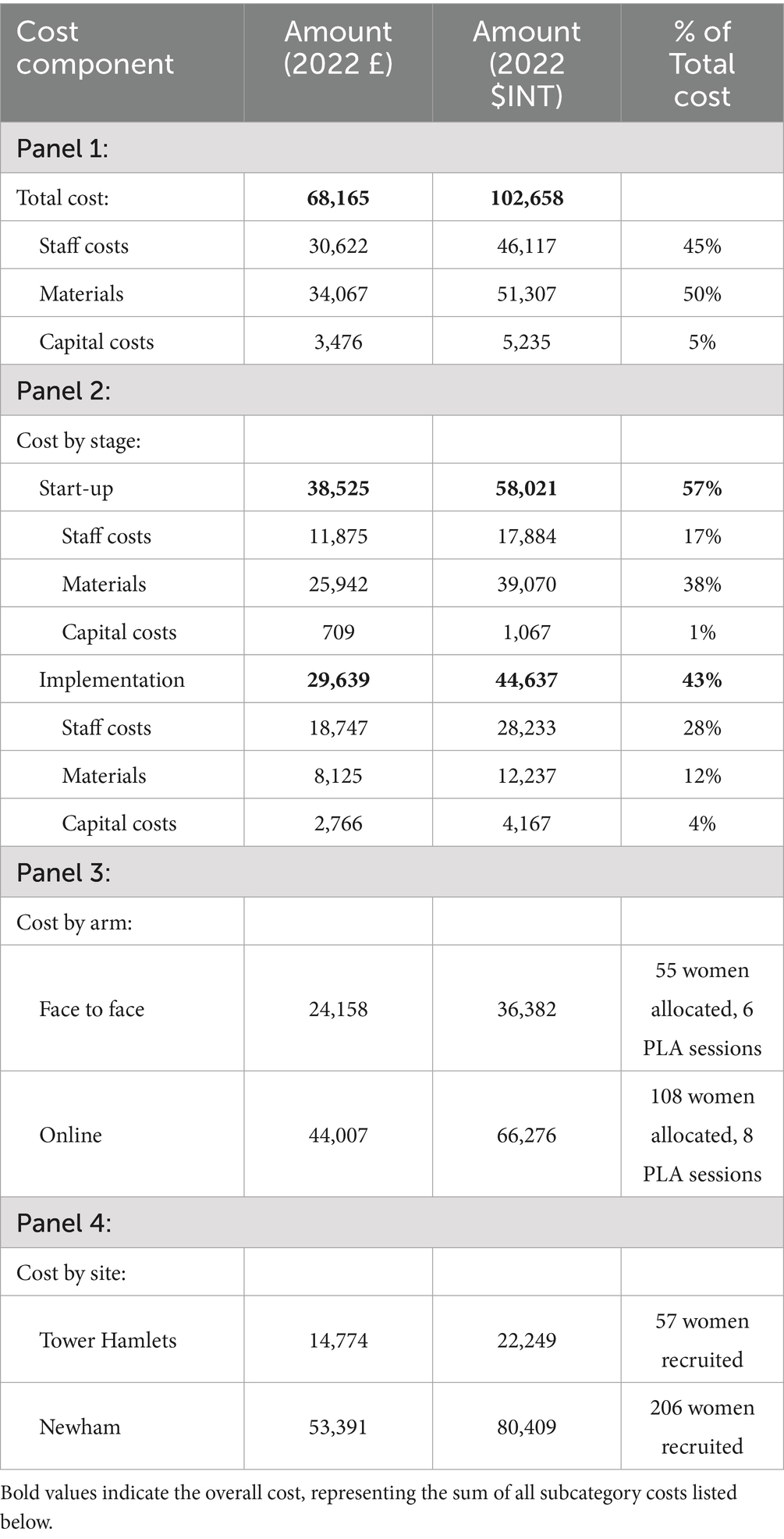

Results: The total cost of NEON design and delivery was £68,165 ($INT 102,658), and the average cost per mother participating in the programme was £439($INT 661) in the face-to face arm and £407($INT 614) in the online arm. The largest contributor to the total cost was materials (50%), including NEON training manuals and intervention toolkits, vouchers for the community facilitators, and overheads, followed by staff costs (45%) and capital investments (5%). The total cost of intervention delivery in Newham accounted for around 0.047% of the borough’s annual child development expenditure, while the total intervention cost in Tower Hamlets was equivalent to 0.003% of its spending on children’s development.

Conclusion: The delivery of NEON is largely within local authorities’ budget for childhood development. The unit cost is expected to decrease when sharing costs are spread across more participants and implementing systems are validated and well developed.

Highlights

• This paper performs a cost analysis to understand the cost implications of running a participatory learning and actions intervention in London.

• This approach allows the incorporation of the local context such as the culture, beliefs, and existing practices, potentially leading to boosted accessibility and acceptability.

• This study deems that the NEON programme on evaluation is a financially sustainable model within the target population.

1 Introduction

Each year, over 240 million children under age 5 worldwide, face significant biological and psychosocial hazards that compromise their developmental potential (1). These hazards include malnutrition, exposure to violence and heavy metal, and inadequate cognitive and social-emotional stimulation (7). The first 5 years of life are crucial for brain development and the formation of caregiver-child attachments, therefore sensitive to early experiences (3). Exposure to adversity during this period has long-term negative impacts on physical and psychosocial health, as well as educational and economic achievements in adulthood (3–7). In monetary terms, the average income loss for adversely impacted children is estimated at 26% per annum (8). Additionally, there are intergenerational consequences as the developmental deficit and income loss perpetuates a cycle of poverty (8). At the same time, intervention during this early period has been shown to yield the greatest benefit for health and development (37). The benefit-cost ratios of such interventions have been estimated as approximately 18:1 for stunting reduction, 4:1 for preschool education, and 3:1 for home visits for underdeveloped children (8). The potential societal benefits far outweigh the costs, making such interventions particularly relevant in high- burden and resource-constrained settings.

While the majority of children at risk are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), these hazards may be generated or exacerbated by socio-cultural practices and economic constraints regardless of the geographic location (4). South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have the highest proportion of children under 5 at risk, at approximately 53 and 66%, respectively, (1). These statistics, along with similar estimates published in 2007 (4) directed a large number of early childhood interventions to these contexts (9). However, minority groups facing similar socio-cultural norms and economic disadvantages in high-income countries have largely been overlooked to date (10).

There is evidence to suggest that a large proportion of the minority ethnic population in the UK, especially those with South Asian heritage, experience significant social and economic disadvantage (11, 12). This may contribute in turn to poorer health outcomes. Children from South Asian families resident in the UK, are susceptible to many of the same developmental risks as young children resident in South Asia, including poorer birth outcomes and nutrition status (13, 14). The causes of these risks in the UK context are complex, including socioeconomic deprivation, discrimination, language barriers, cultural norms, and limited access to health information, among other factors (15). Early childhood interventions tailored specifically to these minority ethnic groups can improve health outcomes in early childhood and may help avert lifelong disparities in health, education, and economic outcomes. Unfortunately, the availability of such interventions is limited and there is a need for additional testing of targeted and effective interventions that can be delivered at low cost (16, 17).

The Nurture Early for Optimal Nutrition (NEON) programme, therefore, was designed to promote equitable early childhood development by educating mothers of South Asian origin in East London on optimal feeding, care, and dental hygiene practices (10). The intervention was delivered via participatory learning and action (PLA) cycles with women’s groups, which involved active participation, learning, and action by community members and mothers to identify and address problems together. Similar interventions in LMICs (18), including Bangladesh (19), Pakistan (20), and India (21), have been shown to be effective and cost-effective in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, improving infant feeding, hygiene, and care practices, finally resulting in enhanced cognitive, language, and motor development outcomes among children participants (22). However, there is limited evidence of their success in disadvantaged areas of high-income countries. Adapting this approach for implementation in South Asian communities in East London, the NEON programme added evidence to the effectiveness and feasibility of PLA in high-income settings. This study conducted a cost analysis of the NEON intervention.

2 Methods

2.1 Study setting and intervention design

The study was conducted in two East London boroughs, Tower Hamlets (TH) and Newham (NH), both of which have large South Asian populations and experience high levels of socio-economic deprivation. According to the most recent census data, these areas exhibit higher levels of unemployment, lower average incomes, and poorer housing conditions compared to the rest of London (10). Furthermore, health indicators such as infant mortality rates, childhood obesity rates, and low breastfeeding rates are significantly higher in these boroughs compared to the London average (23). Early childhood health indicators, including immunisation uptake and access to nutritional support, are also lower in TH and NH, highlighting the need for targeted public health interventions in these communities (5). These socio-economic and health disparities make TH and NH particularly relevant for studying the impact of early childhood interventions.

The NEON pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial was run from December 2019 to May 2023 to assess the feasibility of a definitive trial (10, 24). A total of 12 clusters, i.e., borough wards, were equally randomised to an online treated arm, a face-to-face treated arm, and a control arm, balancing participant contamination while ensuring optimal representation of the South Asian population in East London, including Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, and Bangladeshi communities (25). To enhance the accessibility and feasibility of the programme, Community Facilitators (CFs) from these ethnic backgrounds, as well as Health Visitors (HVs), General Practitioners (GPs), and midwives at each study ward, were recruited and involved in the development and delivery of the intervention. Recruitment of participants began in May 2022, and implementation started in September 2022; 263 mothers of infants under 24 months from TH and NH were enrolled. Participants in the treated arms received one PLA session every 2 weeks for a duration of 14 weeks and were followed up for 6 months afterwards. They were all provided with an intervention toolkit (24), including:

1. Picture cards detailing recommended feeding, care, and dental hygiene practices,

2. Healthy infant cultural recipes,

3. Participatory Community Asset Maps, and

4. A list of resources and services supporting infant feeding, care, and dental hygiene practices.

The control group received the standard care under the Healthy Child Programme 0–5, commissioned to local authorities, including regular mandatory postnatal visits and optional prenatal visits (10, 26). Single blinding was implemented for participant recruitment and outcome assessment. For detailed information on the study design, intervention packages, and implementation, please refer to the published NEON protocol (10).

2.2 Costing method

We conducted a financial and economic costing from the provider perspective. Cost data were sourced from the expenditure and accounting records of the implementing institutions in a trial-specific data collection Excel-based tool (10). We followed a stepdown procedure (2) to first identify all the costs incurred from the initiation of the intervention development to the completion of evaluation and dissemination. We distinguished between costs associated with start-up and implementation and excluded research costs. Costs associated with recruiting and monitoring the control group were also excluded. The monitoring and evaluation costs were too intricately linked to be separated from the implementation costs. Therefore, they were included as part of the implementation costs, as they are essential for successful programme delivery (27).

Costs were categorised into capital costs and recurrent costs. Capital costs included all goods and services having a useful life of more than 1 year, primarily computers and cameras. Their costs were recorded at their original purchase prices and depreciated at a rate of 20% per year to account for the value consumed during the intervention (28). Recurrent costs consisted of staff costs and materials. Staff costs included salaries for the study team who were responsible for designing and implementing the NEON intervention, which included activities such as coordinating local HVs, GPs, and Midwifery teams, and recruiting participants and CFs. They were valued based on the actual pre-tax salaries remitted. Other goods and services were deemed as materials, including PLA group facilitator manuals, intervention toolkits, rented venues and snacks for PLA meetings, staff training courses, vouchers for CFs, and overheads. These were valued at the original purchasing value. All costs were inflated or deflated to 2022 values. To improve evidence interpretability, discounting beyond inflation adjustment was not applied, as doing so would require further assumptions about the opportunity cost of funds. Results were reported both in 2022 pound sterling (£) and in 2022 international dollars ($INT).

2.3 Base case analysis

We evaluated the efficiency of service delivery by estimating two unit costs - the total cost per beneficiary and the implementation cost per beneficiary for both online and face-to-face arm. The total cost per beneficiary, (i.e., the total cost per mother) was calculated as the total cost divided by the number of participating mothers. The implementation cost per beneficiary (mother) was computed as the total cost per mother excluding fixed start-up costs in order to reflect the marginal cost of recruiting and treating one more participant. We conducted affordability analysis by calculating the total cost of NEON delivery as a percentage of the local authorities’ budget, and report this separately for Newham and Tower Hamlet.

2.4 Sensitivity analysis

We explored variation in service delivery efficiency by performing deterministic one-way sensitivity analysis on the total cost per mother. The base case reflected the best approximation of expected unit cost. Changes in assumptions and parameters, such as the number of effectively treated participants, the appropriate capital cost depreciation rate and the joint cost allocation, were individually assessed against the base case to gauge their influence on service efficiency. Firstly, we used the number of mothers who proceeded to the first PLA meeting as the denominator in the base case. We explored the unit cost variation by using the number of mothers who completed most PLA sessions, reflecting attrition. We also explored using the number of mothers who completed all six PLA meetings and were successfully followed up until the end of the study, under the stricter assumption of only those women being effectively treated. Second, we increased and decreased the capital good depreciation rate by 10 percentage points to account for the different degree of wear and tear of equipment. Third, we introduced variations to the joint cost allocation, varying the proportion of shared staff, capital, and other recurring costs assigned to PLA implementation and other undertakings like monitoring, evaluation, or research. By adjusting the initial allocation up and down by 20 percentage points, we derived a range of unit costs. This adjustment can reflect the shifting importance of various activities in future scale-up trials and replications in different contexts. The former scenarios may require increased monitoring and evaluation efforts, while the latter should put a greater emphasis on research.

3 Results

3.1 Base case

Since NEON was intended to be delivered as a programme in addition to usual practice or care, all the costs incurred were considered incremental costs. The total incremental cost of delivering NEON (Table 1) in two boroughs in East London was £68,165 ($INT 102,658). In Tower Hamlets, the total cost was £14,774 ($INT 22,249) and in Newham, £53,391 ($INT 80,409). In total, the start-up cost of £38,525 ($INT 58,021) accounted for 57% of the total cost, while the implementation cost of 29,639 ($INT 44,637) accounted for the rest of 43% (Table 1- Panel 2). Detailed results of total cost are presented in Table 1.

Materials’ costs contributed to half (50%) of the total costs, followed by staff costs (45%). The capital costs were minimal (5%) in comparison, and were mainly attributed to the electronic equipment required for advocacy, monitoring, and evaluation (Table 1-Panel 1). The costs incurred in these different categories during the start-up and implementation periods are presented in more detail in Table 1- panel 2.

Of the 263 women recruited, 186 met the inclusion criteria and provided consent to participate. Among these, 55 were allocated to the face-to-face arm, 108 to the online arm, and 23 to the control arm. By the end of the study, dropout rates were 11, 20, and 22% in the three arms, respectively. The number of PLA sessions was adjusted according to participant numbers: six sessions were conducted in the face-to-face arm, eight in the online arm, and none in the control arm. The total costs, including start-up, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation, were £24,158 (INT$36,382) for the face-to-face arm, £44,007 (INT$66,276) for the online arm, and £7,827 (INT$11,787) for the control arm. However, costs incurred in the control arm were excluded from the total programme cost.

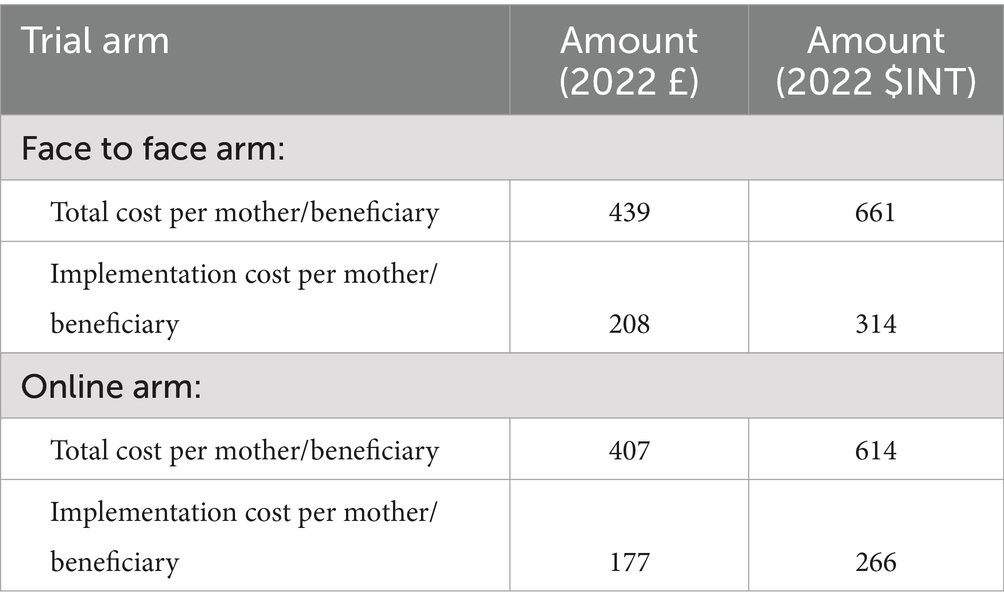

We estimated the cost per beneficiary on an intention-to-treat basis, using the allocated number of participants, as most costs, including start-up costs (57%), staff and capital costs during the implementation stage (32%) (Table 1- Panel 2) had already been incurred by that stage. The average cost per mother was estimated to be £439($INT 661) in the face-to face arm and £407($INT 614) in the online arm (Table 2). Excluding the fixed start-up costs, the implementation cost per mother reduced to £208 ($INT 314) for the face-to-face arm and £177($INT 266) for the online arm. This implies that recruiting an additional participant, engaging her in PLA women’s groups, and following up on behaviour change and child health outcomes would require an additional INT$314 in the face-to-face arm and INT$266 in the online arm (Table 2).

In Newham, the total cost of NEON delivery was estimated to account for approximately 0.047% of the borough’s expenditure on children’s development during the 2020–21 fiscal year (29). Scaling up the intervention to cover all 10,967 children under the age of 2 in this borough, assuming one caregiver per child, the cost share would rise to roughly 0.491% if implemented face-to-face and 0.418% if implemented online. In Tower Hamlets, the total cost was equivalent to about 0.003% of Tower Hamlets’ spending on children’s development during the same period (30).

3.2 Sensitivity analysis

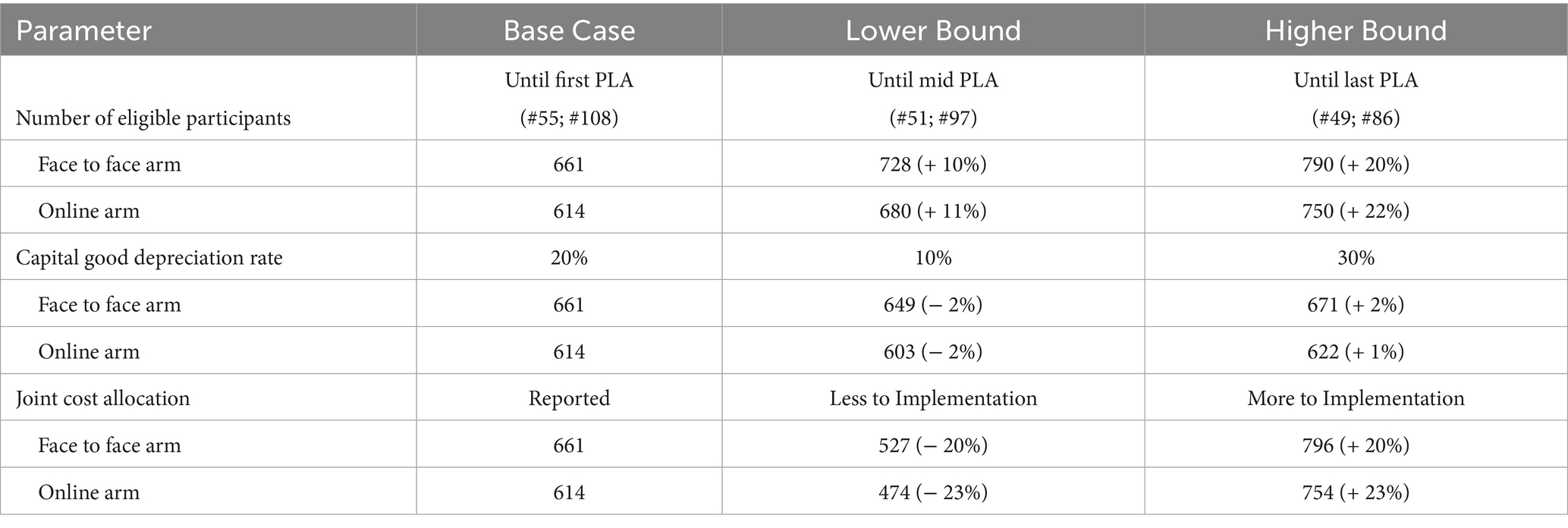

The sensitivity analyses for the total cost per mother are presented in Table 3. The total cost per mother was moderately sensitive to the number of participants (i.e., coverage), increasing by about 10% when calculated for those remaining at mid-PLA sessions (51 in the face-to-face arm and 97 in the online arm) and by about 20% when restricted to the 135 mothers who completed the study (Table 3).

The total cost per mother was largely insensitive to variations in the depreciation rate of capital goods, as capital expenses represented a small proportion of the overall cost. Specifically, as the depreciation rate increased from 10 to 30%, the average cost per mother rose by around 3–4% (Table 3).

Furthermore, the unit cost was notably sensitive to the joint cost allocation. Increasing or decreasing the allocation to implementation activities by 20 percentage points resulted in a corresponding change of just over ±20% in the total cost per mother.

4 Discussion

This study aims to assess the costs and affordability of NEON – an early childhood intervention delivered via PLA cycles with women’s groups to improve South Asian infants’ health in London. The intervention cost £68,165 ($INT 102,658) in total, equivalent to less than 0.1% of child development annual spending of local authorities. The average cost per mother was estimated to be £439($INT 661) in the face-to face arm and £407($INT 614) in the online arm, while the marginal cost of recruiting one additional participant, excluding fixed start-up costs, was £208 ($INT 314) for the face-to-face arm and £177($INT 266) for the online arm. The total cost of covering all children under the age of 2 in each borough was estimated at approximately 0.4–0.5% of the borough’s annual child development expenditure.

Precise health outcome measurement, such as DALYs and QALYs, was beyond the scope of this pilot feasibility randomised controlled trial; nevertheless, we observed substantial intermediate behavioural changes. Compared with the control arm, children in the intervention arms showed large increases in food responsiveness (from 29 to 72%) and food enjoyment, alongside reductions in emotional overeating (from 15 to 5%). Parental feeding practices also improved: emotional feeding decreased from 20 to 11% and instrumental feeding from 65 to 38%. Video analyses further identified a reduction in force-feeding behaviours. No significant differences were observed in children’s BMI z-scores, likely attributable to the limited six-month follow-up period (31).

PLA with women’s groups aimed at improving early childhood health has been found to be highly cost-effective across a range of outcomes in resource constrained settings. The cost-effectiveness of a community mobilisation intervention through women’s groups to improve maternal and neonatal care was estimated at $79 per disability-adjusted life year averted in Malawi (MaiKhanda trial) (32), $220 to $393 per year of life lost averted in rural Bangladesh (33), and $14 per cognitive development score gained in rural Viet Nam (38). However, few studies have assessed the cost-effectiveness of PLA with women’s groups in enhancing early childhood nutrition (21, 34, 35). A nutrition-focused intervention targeting children under 2 years of age in Pakistan significantly improved weight-for-height z-scores, cognitive, language, and motor development, but did not provide formal cost-effectiveness estimates (20). Similarly, a community-based strategy in India promoting infant feeding, hygiene, care, and stimulation that demonstrated an improvement in length-for-age z-score was associated with a cost of $302 per woman enrolled (21). No evaluations of costs or cost-effectiveness of PLA with women’s groups aimed at improving early childhood health and development have been conducted in the UK or equivalent high-income settings. To our knowledge, this study is the first to generate evidence in this setting; we hope our findings inform future early childhood nutrition interventions via community-led PLA in both LMICs and high-income countries.

The incremental start-up cost ($INT 58,021), accounting for more than half of the total cost, is expected to be lower for future replicated or scaled-up interventions. Much of the groundwork, including evidence-based implementation strategies (15), staff training, and community partnership establishment, has already been explored and streamlined. Insights, methodologies, and resources from previous projects can facilitate smoother project initiation, reduce trial-and-error phases, and optimise resource allocation, therefore reducing start-up efforts.

Moreover, as the intervention coverage increases, economies of scale may further reduce the unit cost. In community-based women’s groups, higher coverage allows for the distribution of fixed costs, such as those for training, coordination, group facilitation and overheads, across a larger number of participants, thereby lowering the cost per unit of service delivered. A similar intervention conducted in rural India on a larger scale (1,253 women covered) estimated their average cost per mother to be INT$ 302 (21). Though the main drivers of the cost gap are differences in price and cost of living, economies of scale also play a significant part.

However, it should be noted that economies of scale may lose their effectiveness as coverage expands to include the majority of the population. Reaching traditionally underserved and marginalised groups often requires additional effort (36). Those groups typically face greater barriers to accessing the programme due to their socioeconomic status, geographical location, disability, or other factors. Ensuring their inclusion may necessitate extra actions, resources, and strategies beyond those required for more privileged or accessible populations. Research on scaling up nutrition interventions has shown that when coverage expands to 80% of the target population, the unit cost remains relatively stable. However, as the effort shifts to reach the remaining 10%—pushing coverage from 80 to 90%—the unit cost can increase three to four times compared to earlier stages of the scale-up (ibid).

Integrating new interventions into existing services can ease implementation challenges and reduce overall costs. However, maintaining service coverage and quality, and controlling costs, in subsequent replications may prove challenging (8, 18, 19). The NEON intervention, implemented via PLA women’s groups, was founded on a community-led model that integrated into the regular care delivery systems of local communities. This approach allowed the incorporation of the local context, such as the culture, beliefs, and existing practices, leading to boosted accessibility and acceptability (8, 19). Nevertheless, the extensity and quality of service delivery could be largely dependent on the capabilities of the local health system (8). In contexts with limited resources and weaker public health infrastructures, marginalised populations may remain underserved, which could undermine the central goal of promoting equitable early childhood development. Moreover, integrating new interventions into established health systems may impose additional workloads on health workers, potentially affecting their well-being, performance, and the overall quality of care they provide (23). By leveraging existing personnel and public resources, the NEON intervention obviated the need for recruiting specialised staff and procuring relevant resources and reserved potential to be efficiently replicated on a larger scale. However, replications in less resourced contexts may incur additional costs to address these systemic challenges.

Costs are also sensitive to contextual factors, such as local price levels and logistical considerations. For example, staff salaries, which account for 45% of the total cost, could be lower if the interventions were expanded or replicated in regions with lower average salaries than London. Additionally, nearly half of the total cost was allocated to monitoring and evaluation. In this trial, extensive efforts were made to ensure proper implementation and to conduct frequent, detailed assessments at each stage, which contributed significantly to the overall costs. In the future, once the intervention validity is established and a proven implementation system is in place, these monitoring efforts could be scaled back, leading to further cost reductions.

The total cost was also inflated due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The overall trial duration has been extended to accommodate interruptions caused by lockdowns and sick leaves (31). Stringent infection prevention and control measures have been implemented, such as enhanced cleaning and disinfection protocols, increased use of PPE, and modifications to facility layouts. These situations increased the operational costs. But we expect the increase would not be significant since we carried out remote working and online PLA meetings.

5 Conclusion

The delivery of NEON largely falls within local authorities’ budgets for childhood development. The unit cost is sensitive to both the level of coverage and the joint cost allocation across activities. It is anticipated that the unit cost will further decrease as the intervention scales up, with costs being spread across a larger number of participants and monitoring and evaluation efforts being reduced once validated and well-developed implementation systems are established.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they contain sensitive information that could compromise participant confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Logan Manikam, bG9nYW4ubWFuaWthbS4xMEB1Y2wuYWMudWs=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by UCL Research Ethics Committee [Ethics ID 17269/001]. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Group members of the NEON Steering Team collaborators

In addition to the authors, members of the NEON steering team consist of Prof Atul Singhal, Prof Mitch Blair, Dr. Sonia Ahmed, Amelie Gonguet, Gary Wooten, Dr. Ian Warwick, Vaikuntanath Kakarla, Phoebe Kalungi, Prof Richard Watt, Prof Audrey Prost, Dr. Edward Fottrell, Ashlee Teakle, Keri McCrickerd, Dr. Rana Conway, Professor Lisa Dikomitis, Mari Toomse- Smith, Scott Elliot, Julia Thomas, Aeilish Geldenhuys, Chris Gedge, Kristin Bash, Dr. Dianna Smith, Kate Questa, Dr. Megan Blake, Prof Gary Tse, Dr. Queenie Law Pui Sze, Gavin Talbot, Dr. Chiong Yee Keow, Dr. Angela Trude, Prof Lindsay Forbes, Dr. Nazanin Zand, Lakmini Shah and Yeqing Zhang.

Author contributions

YZ: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. PP: Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Writing – review & editing. KK: Writing – review & editing. DF: Writing – review & editing. ML: Writing – review & editing. MH: Writing – review & editing. JD: Writing – review & editing. CL: Writing – review & editing. KW-M: Writing – review & editing. CI: Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing. PK: Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing. LM: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. NB: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. LM and PP are funded via a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Advanced Fellowship (Ref: NIHR300020) to undertake the Pilot Feasibility Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial of the NEON programme in East London. ML was funded by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames. This work is also supported by the NIHR GOSH BRC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the South Asian community facilitators in the NEON Intervention and community members of the London Boroughs of Tower Hamlet and Newham for their important contribution and engagement to this research project. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the NEON Core Team, Steering Team and all health experts who contributed to this study. We would like to thank the Women & Children First Charity and First Steps Nutrition Trust for their valuable contributions and guidance throughout the study. Steering team members had an opportunity to critically review results and contribute to the process of finalising this paper. The authors would like to thank the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Academy and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames for funding the NEON study. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest

PP, SC, KK, DF, LM were employed by Aceso Global Health Consultants Pte Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed in the publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the sponsor (UCL), funder (NIHR), study partners (Tower Hamlets GP Care Group, London Borough of Newham Council).

References

1. Lu, C, Black, MM, and Richter, LM. Risk of poor development in young children in low-income and middle-income countries: an estimation and analysis at the global, regional, and country level. Lancet Glob Health. (2016) 4:e916–22. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30266-2

2. Conteh, L, and Walker, D. Cost and unit cost calculations using step-down accounting. Health Policy Plan. (2004) 19:127–35. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh015

3. Black, MM, Walker, SP, Fernald, LC, Andersen, CT, DiGirolamo, AM, Lu, C, et al. Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. (2017) 389:77–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7

4. Grantham-McGregor, S, Cheung, YB, Cueto, S, Glewwe, P, Richter, L, and Strupp, B. Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet. (2007) 369:60–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4

5. Black, MM, and Hurley, KM. Investment in early childhood development. Lancet. (2014) 384:1244–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60607-3

6. Victora, CG, Adair, L, Fall, C, Hallal, PC, Martorell, R, Richter, L, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet. (2008) 371:340–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4

7. Walker, SP, Wachs, TD, Gardner, JM, Lozoff, B, Wasserman, GA, Pollitt, E, et al. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. (2007) 369:145–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2

8. Richter, LM, Daelmans, B, Lombardi, J, Heymann, J, Boo, FL, Behrman, JR, et al. Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet. (2017) 389:103–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31698-1

9. Evans, DK, Jakiela, P, and Knauer, HA. The impact of early childhood interventions on mothers. Science. (2021) 372:794–6. doi: 10.1126/science.abg0132

10. Manikam, L, Allaham, S, Patil, P, Naman, M, Ong, ZL, Demel, IC, et al. Nurture early for optimal nutrition (NEON) participatory learning and action women’s groups to improve infant feeding and practices in south Asian infants: pilot randomised trial study protocol. BMJ Open. (2023). 13:e063885. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063885

11. Evandrou, M, Falkingham, J, Feng, Z, and Vlachantoni, A. Ethnic inequalities in limiting health and self-reported health in later life revisited. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2016) 70:653–62. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206074

12. Brown, MS. Religion and economic activity in the south Asian population. Ethnic Racial Stud. (2000) 23:1035–61. doi: 10.1080/014198700750018405

13. Nongmaithem, SS, Beaumont, RN, Dedaniya, A, Wood, AR, Ogunkolade, B-W, Hassan, Z, et al. Babies of south Asian and European ancestry show similar associations with genetic risk score for birth weight despite the smaller size of south Asian newborns. Diabetes. (2022) 71:821–36. doi: 10.2337/db21-0479

14. Stanfield, KM, Wells, JC, Fewtrell, MS, Frost, C, and Leon, DA. Differences in body composition between infants of south Asian and European ancestry: the London mother and baby study. Int J Epidemiol. (2012) 41:1409–18. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys139

15. Lakhanpaul, M, Benton, L, Lloyd-Houldey, O, Manikam, L, Rosenthal, DM, Allaham, S, et al. Nurture early for optimal nutrition (NEON) programme: qualitative study of drivers of infant feeding and care practices in a British-Bangladeshi population. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e035347. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035347

16. Wardle, J, Sanderson, S, Guthrie, CA, Rapoport, L, and Plomin, R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obes Res. (2002) 10:453–62. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.63

17. Greater London Authority. Early years interventions to address health inequalities in London - the economic case [Internet]. (2011). Available online at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/gla_migrate_files_destination/Early%20Years%20report%20OPT.pdf.Accessed 14 July 2023.

18. Prost, A, Colbourn, T, Seward, N, Azad, K, Coomarasamy, A, Copas, A, et al. Women's groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2013) 381:1736–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60685-6

19. Younes, L, Houweling, TA, Azad, K, Kuddus, A, Shaha, S, Haq, B, et al. The effect of participatory women's groups on infant feeding and child health knowledge, behaviour and outcomes in rural Bangladesh: a controlled before-and-after study. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2015) 69:374–81. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204271

20. Yousafzai, AK, Rasheed, MA, Rizvi, A, Armstrong, R, and Bhutta, ZA. Effect of integrated responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions in the lady health worker programme in Pakistan on child development, growth, and health outcomes: a cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. Lancet. (2014) 384:1282–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60455-4

21. Nair, N, Tripathy, P, Sachdev, HS, Pradhan, H, Bhattacharyya, S, Gope, R, et al. Effect of participatory women's groups and counselling through home visits on children's linear growth in rural eastern India (CARING trial): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. (2017) 5:e1004–16. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30339-X

22. Pulkki-Brännström, A-M, Haghparast-Bidgoli, H, Batura, N, Colbourn, T, Azad, K, Banda, F, et al. Participatory learning and action cycles with women’s groups to prevent neonatal death in low-resource settings: a multi-country comparison of cost-effectiveness and affordability. Health Policy Plann. (2020) 35:1280–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa081

23. Muller, AE, Hafstad, EV, Himmels, JPW, Smedslund, G, Flottorp, S, Stensland, SØ, et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. (2020) 293:113441. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113441

24. Manikam, L, Allaham, S, Demel, IC, Bello, UA, Naman, M, Heys, M, et al. Developing a community facilitator-led participatory learning and action women's group intervention to improve infant feeding, care and dental hygiene practices in south Asian infants: NEON programme. Health Expect. (2022) 25:2416–30. doi: 10.1111/hex.13557

25. Crawford Shearer, NB, Fleury, JD, and Belyea, M. An innovative approach to recruiting homebound older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs. (2010) 3:11–8. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20091029-01

26. National Children’s Bureau. Briefing for the children and young people’s voluntary sector [Internet]. (2016). Available online at: https://www.ncb.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/files/Local%2520Authorities%2520Role%2520In%2520Public%2520Health.pdf.Accessed 9 August 2023.

27. Batura, N, Pulkki-Brännström, A-M, Agrawal, P, Bagra, A, Haghparast-Bidgoli, H, Bozzani, F, et al. Collecting and analysing cost data for complex public health trials: reflections on practice. Glob Health Action. (2014) 7:23257. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23257

28. Vassall, A, Sweeney, S, Kahn, J, Gomez Guillen, G, Bollinger, L, Marseille, E, et al., Reference case for estimating the costs of global health services and interventions. Global Health Cost Consortium. (2017) Project Report. Available online at: https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/4653001

29. The London Borough of Newham. The Statement of Accounts in 2020/2021. (2021). Available online at: https://www.newham.gov.uk/downloads/file/3834/final-signed-audit-opinion-version. Accessed 9 August 2023.

30. The London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The Statement of Accounts in 2020–21. (2021). Available online at: https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/lgnl/council_and_democracy/council_budgets_and_spending/annual_accounts.aspx. Accessed 9 August 2023.

31. Manikam, L, Patil, P, El Khatib, T, Chakraborty, S, Hiley, DD, Fujita, S, et al. Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial-Nurture Early for Optimal Nutrition (NEON) Study: Community facilitator led participatory learning and action (PLA) women’s groups to improve infant feeding, care and dental hygiene practices in South Asian infants aged < 2 years in East London medRxiv. (2024) 2024–03. doi: 10.1101/2024.03.07.24303745

32. Colbourn, T, Pulkki-Brännström, AM, Nambiar, B, Kim, S, Bondo, A, Banda, L, et al. Cost-effectiveness and affordability of community mobilisation through women’s groups and quality improvement in health facilities (Mai Khanda trial) in Malawi. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. (2015) 13:1. doi: 10.1186/s12962-014-0028-2

33. Fottrell, E, Azad, K, Kuddus, A, Younes, L, Shaha, S, Nahar, T, et al. The effect of increased coverage of participatory women’s groups on neonatal mortality in Bangladesh: a cluster randomised trial. JAMA Pediatr. (2013) 167:816–25. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2534

34. Batura, N, Hill, Z, Haghparast-Bidgoli, H, Lingam, R, Colbourn, T, Kim, S, et al. Highlighting the evidence gap: how cost-effective are interventions to improve early childhood nutrition and development? Health Policy Plan. (2015) 30:813–21. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu055

35. Britto, PR, Singh, M, Dua, T, Kaur, R, and Yousafzai, AK. What implementation evidence matters: scaling-up nurturing interventions that promote early childhood development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2018) 1419:5–16. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13720

36. Engle, PL, Fernald, LC, Alderman, H, Behrman, J, O'Gara, C, Yousafzai, A, et al. Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. (2011) 378:1339–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60889-1

37. Britto, PR, Lye, SJ, Proulx, K, Yousafzai, AK, Matthews, SG, Vaivada, T, et al. Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet. (2017) 389:91–102. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31390-3

Keywords: participatory learning and action women’s groups, early childhood development, costs, affordability, nutritional intervention

Citation: Zhang Y, Patil P, Chaudhary S, Kondhare KD, Faijue DD, Lakhanpaul M, Heys M, Drazdzewska J, Llewellyn CH, Webb-Martin K, Irish C, Archibong M, Gilmour J, Kalungi P, Skordis J, Manikam L, Batura N and the NEON Steering Team (2025) Economic evaluation: costing participatory learning and action cycles with women’s groups to improve feeding, care and dental hygiene for South Asian infants in London. Front. Public Health. 13:1601990. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1601990

Edited by:

Qi Zhang, Old Dominion University, United StatesReviewed by:

Caroline Dusabe, Save the Children Australia, AustraliaChipo Chitereka, University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Patil, Chaudhary, Kondhare, Faijue, Lakhanpaul, Heys, Drazdzewska, Llewellyn, Webb-Martin, Irish, Archibong, Gilmour, Kalungi, Skordis, Manikam, Batura and the NEON Steering Team. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Logan Manikam, bG9nYW4ubWFuaWthbS4xMEB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

†These authors share first authorship

‡These authors share senior authorship

Yeqing Zhang

Yeqing Zhang Priyanka Patil2,3†

Priyanka Patil2,3† Darlington David Faijue

Darlington David Faijue Michelle Heys

Michelle Heys Joanna Drazdzewska

Joanna Drazdzewska Clare H. Llewellyn

Clare H. Llewellyn Jolene Skordis

Jolene Skordis Logan Manikam

Logan Manikam Neha Batura

Neha Batura