- Department of Journalism, Center for Science Communication, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

This study examines what “just” visions underpin how South Africa’s COP26 energy transition deal was framed in news media and Facebook public discourse. At the 2021 Glasgow summit, South Africa secured an $8.5 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) deal to support the decarbonization of its coal-dependent energy system, sparking intense national debate. Energy communication research offers a valuable lens for understanding how such deliberations unfold, highlighting public perceptions and attitudes toward a just energy transition. Yet, attention to justice dimensions in public conversations on energy transitions—particularly in Africa—remains limited, and cross-platform discourse comparisons are rare. Addressing these gaps, we analyzed 53 news publications from 17 South African mainstream media outlets and 743 Facebook comments on posts about the JETP using qualitative frame and network analysis, focusing on justice framing, actor visibility, and temporal orientation. Findings reveal stark asymmetries. Procedural justice appeared prominently in both spaces (58%) but served divergent purposes: media framed it to legitimize state-led pacing, while Facebook emphasized governance failures and systemic distrust. Media narratives privileged elite voices—government, experts, business—with workers and communities receiving only 1% visibility. In contrast, Facebook reflected grassroots perspectives grounded in lived experience and socio-economic precarity. Media discourse was future-focused and optimistic; Facebook was rooted in historical grievances and skepticism. The study discusses implications for South Africa’s energy transition, highlighting discursive power imbalances and their significance for just-transition governance and communication.

1 Background: South Africa’s energy transition in context

South Africa, as the leading industrialized nation in Africa, is also the continent’s largest carbon emitter and ranks among the top 20 global polluters (Hägele et al., 2022). Intensifying extreme weather events and ecological disruptions, locally and globally, have heightened pressure for rapid emissions reductions aligned with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting temperature rise to well below 2 °C (Saier, 2019). Despite recent climate governance milestones—including the establishment of the Presidential Climate Commission and the enactment of the Climate Change Act in 2024 (Climate Action Tracker, 2025)—South Africa’s power infrastructure remains heavily fossil-fuel-dependent (Mirzania et al., 2023). Understanding how narratives about the shift from coal-dependent energy systems toward lower-carbon alternatives, including renewable energy, are constructed and contested in the public sphere is therefore timely and essential. This paper examines how South Africa’s COP26 energy transition deal was framed in two key discursive spaces: mainstream news media and Facebook user comments.

South Africa offers a compelling case for such an investigation, especially within the Global South. As the first recipient of the United Nations-brokered Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) in 2021, the country became a focal point for international climate finance and governance experimentation. Coal provides 94% of South Africa’s primary energy and nearly 70% of its installed generation capacity (IEA, n.d.), making it responsible for about 40% of Africa’s emissions and ranking it 13th globally (The Presidency, 2024). South Africa’s updated nationally determined contribution (NDC) targets a 31% emissions reduction by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2050, goals that require extensive economic, social, and infrastructural shifts. Government estimates place the cost of implementing its just energy transition (JET) program for 2023–2027 at ZAR 1.5 trillion (USD 81 billion) (The Presidency, 2024), making financial and governance dimensions central to public debate.

These challenges unfold against a backdrop of deep social inequality—characterized by 55% poverty, over 30% unemployment, and wealth concentration where the top 10% control 86% of national wealth (The Presidency, 2024). Electricity insecurity (Venter et al., 2025) and a fossil-fuel-dependent trade system further complicate the transition landscape (The Presidency, 2024). Recognizing these socio-economic realities, the government has foregrounded justice, equity, and inclusivity in its transition planning, notably through its 2022 Just Transition Framework (PCC, 2022).

The announcement of the $8.5 billion JETP at COP26 served as a discursive flashpoint, triggering heightened media attention and sparking vigorous public debate (Okoliko and de Wit, 2024). Communication platforms function as arenas where competing interpretations of major policy issues, such as the energy deal, are teased out for their social, political, and economic implications (Brulle et al., 2012). This surge in public interest presents an opportunity to analyze how justice, governance, and energy futures are framed across different segments of South African society. Framing theory offers a useful lens for exploring these discursive dynamics. Rooted in interpretive sociology and media studies, framing refers to the ways people select, emphasize, and interpret aspects of reality (Schäfer and O’Neill, 2017). Brüggemann (2014, p. 63) describes framing as the “selection and salience” of certain issue dimensions to produce coherent interpretive patterns. In the context of energy transitions, different actors contest not only technical aspects but also economic, political, and temporal implications of change.

Although initiatives like the JETP are broadly welcomed as milestones in advancing rapid transitions, scholars caution against overlooking trade-offs and potential “dark sides of accelerated transitions” (Sovacool et al., 2025, p. 15). For instance, research has shown that rapid energy system shifts can exacerbate social inequalities, affecting access and affordability (Taiwo and Tozer, 2025), and creating new vulnerabilities for coal-dependent communities (Mirzania et al., 2023). The growing adoption of rooftop solar by high-income groups has also been shown to reduce municipal revenues, threatening subsidized services for low-income populations (Nkata, 2022). These tensions reinforce the importance of embedding justice considerations into both transition processes and outcomes.

The concept of a just transition (JT) seeks to address such concerns by advocating for equitable and inclusive energy transformations (Zhao and Lo, 2025). This is especially critical in developing countries where energy access remains uneven (Gore et al., 2025), and in contexts like South Africa, where coal underpins livelihoods and revenues (Mirzania et al., 2023).

Despite growing research on energy transitions, several gaps persist. While public understandings of energy transitions are often assessed through self-reported survey data (Crowe and Li, 2020; Baur et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2022; Ali et al., 2023; Arlt et al., 2023) and interviews (Mirzania et al., 2023), which may reflect social desirability biases and miss the social contexts where opinions form, discourse-analytic approaches analyzing naturally occurring communication can capture how opinions are formed and contested in social contexts (Lyytimäki et al., 2018; Labonte and Rowlands, 2021; Kim et al., 2024). Yet even within discourse-analytic approaches, mediated communication—where actors engage in open deliberation outside researcher-controlled settings—remains underexplored. Much of the existing research focuses on specific technologies (Lyytimäki et al., 2018; Mišić and Obydenkova, 2022) or transitions in high-income Western contexts (Arranz et al., 2024; Gore et al., 2025). Comparative analyses across communication platforms remain rare (Brooks et al., 2024), leaving gaps in understanding how platform-specific affordances shape energy discourse. Additionally, justice as a focal point of analysis has only recently gained traction in mediated energy communication literature (Si et al., 2025). This study addresses these gaps by examining how public debate around South Africa’s COP26 JET deal unfolded across mainstream news media and Facebook.

Brüggemann (2014, p. 63) identifies three focal areas of framing in communication research: frame building, frame effects, and frame analysis. Our focus is on frame analysis, which identifies dominant meaning structures within texts. Media framing research has traditionally focused on mainstream outlets (Schäfer and O’Neill, 2017), which are characteristically identified as privileging elite voices—governments, experts, and business actors (Friedland et al., 2006; Okoliko and de Wit, 2021). In response, recent scholarship has highlighted the value of user-generated content and social media as alternative discursive spaces where excluded voices articulate their views and contest dominant framings (Zhou et al., 2008; Rasmussen, 2014; Schäfer, 2016). In response, recent scholarship has highlighted the value of user-generated content and social media as alternative discursive spaces where excluded voices articulate their views and contest dominant framings (Zhou et al., 2008; Rasmussen, 2014; Schäfer, 2016; Labonte and Rowlands, 2021; Arranz et al., 2024). This study aligns with scholarship that conceptualizes the internet as an extension of the public sphere, drawing on Habermas’s vision of coffeehouses and salons as sites for rational-critical debate (Dahlgren, 2005; Rasmussen, 2014; Schäfer, 2016). Digital platforms enhance visibility and participation but also introduce new risks, including echo chambers, misinformation, and algorithmic distortions that may undermine deliberative quality (de Zeeuw, 2024). While Habermas (2006) originally framed traditional media as intermediaries between citizens and the state, he later acknowledged their vulnerability to elite capture—a dynamic that social media’s decentralized, interactive structure seeks to mitigate, albeit with its own limitations (Friedland et al., 2006; Okoliko and de Wit, 2021).

Building on these insights, this study investigates how discourses surrounding South Africa’s COP26 JET deal were constructed across news media and Facebook. We examine how justice perspectives and actor representations varied across these spaces. Employing a partially mixed sequential dominant status design (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2009), we analyzed 53 news publications from 17 local traditional media outlets and 743 Facebook user comments on news posts about the JETP deal using qualitative frame and network analysis. This cross-platform approach seeks to deepen understanding of how differing communicative dynamics shape imaginaries of a just transition.

The paper proceeds as follows: the next section discusses decarbonization and the just transition, situating the discourse on South Africa’s COP26 JET deal within media framing research on transitions. This is followed by a description of materials and methods, results, and a discussion of key implications for energy transition policy and communication.

2 Decarbonization, transition, and media research

Since the Paris Agreement, international climate diplomacy has pushed for more ambitious mitigation efforts to limit temperature rise to well below 2 °C (Koppenborg, 2025). Central to these efforts is accelerated decarbonization (Sovacool et al., 2025)—reducing CO2 emissions from high-emission sectors such as energy and transport. Achieving this requires systemic shifts toward lower-carbon energy sources, including wind, solar, hydro, geothermal energy, energy storage systems, and gas, alongside more sustainable land-use and agricultural practices. Fossil fuels, major sources of emissions, have historically underpinned human civilization since the industrial era and remain dominant in global energy supply (Mirzania et al., 2023). For example, global electricity consumption rose by nearly 1,100 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2024—more than twice the annual average increase over the past decade (IEA, 2025). Despite rapid renewable energy growth, fossil fuels still met two-thirds of global energy demand increases in 2023 (IEA, 2025), highlighting their continued dominance and the enduring policy tension between climate goals and concerns over energy access, affordability, and security.

In South Africa, these tensions are more pronounced due to a domestic energy system heavily reliant on coal, a major source of employment, electricity, and public revenue (Hanto et al., 2022). Recognizing the complex trade-offs, the government has embedded justice into its decarbonization strategy. The concept of a “just transition” (JT) first appeared in the 2011 National Climate Change Response White Paper and coincided with the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Program (REIPPP), which attracted investments in renewables (Hedley et al., 2024). JT has since become prominent in both policy and public discourse, leading to the adoption of the Just Transition Framework in 2022. This Framework aims to integrate social justice principles into systemic change, seeking to cushion vulnerable groups from transition impacts (PCC, 2022).

South Africa’s JT process has gained international recognition, contributing to its selection as the first beneficiary of an international JETP at COP26. This development has further amplified scholarly attention to JT’s conceptual origins and evolution (Heffron and McCauley, 2018; García-García et al., 2020; Wang and Lo, 2021; Otlhogile and Shirley, 2023; Stark et al., 2023). Stark et al. (2023) trace JT to the American labor movement of the 1970s, where it emerged in response to industrial restructuring. As contemporary energy systems undergo similar transformations, calls for fairness in policy design and implementation have grown, especially among labor unions and vulnerable communities (Della Bosca and Gillespie, 2018; Stark et al., 2023).

Scholars responding to this contemporary challenge draw from justice theory to highlight how transition outcomes can be made more equitable (Heffron and McCauley, 2018; Wang and Lo, 2021; Guevara-Cue, 2025). Although no universal definition exists (Heffron and McCauley, 2018), Stark et al. (2023, p. 1285) describe JT as “a way of linking dimensions of climate action with social fairness.” Scholars commonly focus on three interrelated dimensions: distributional justice (fair allocation of costs and benefits), procedural justice (inclusive participation in decision-making), and recognitional justice (acknowledgment of identities, knowledge systems, and historical injustices) (García-García et al., 2020). Some also propose restorative justice as a fourth dimension, emphasizing historical redress and environmental healing (Mirzania et al., 2023).

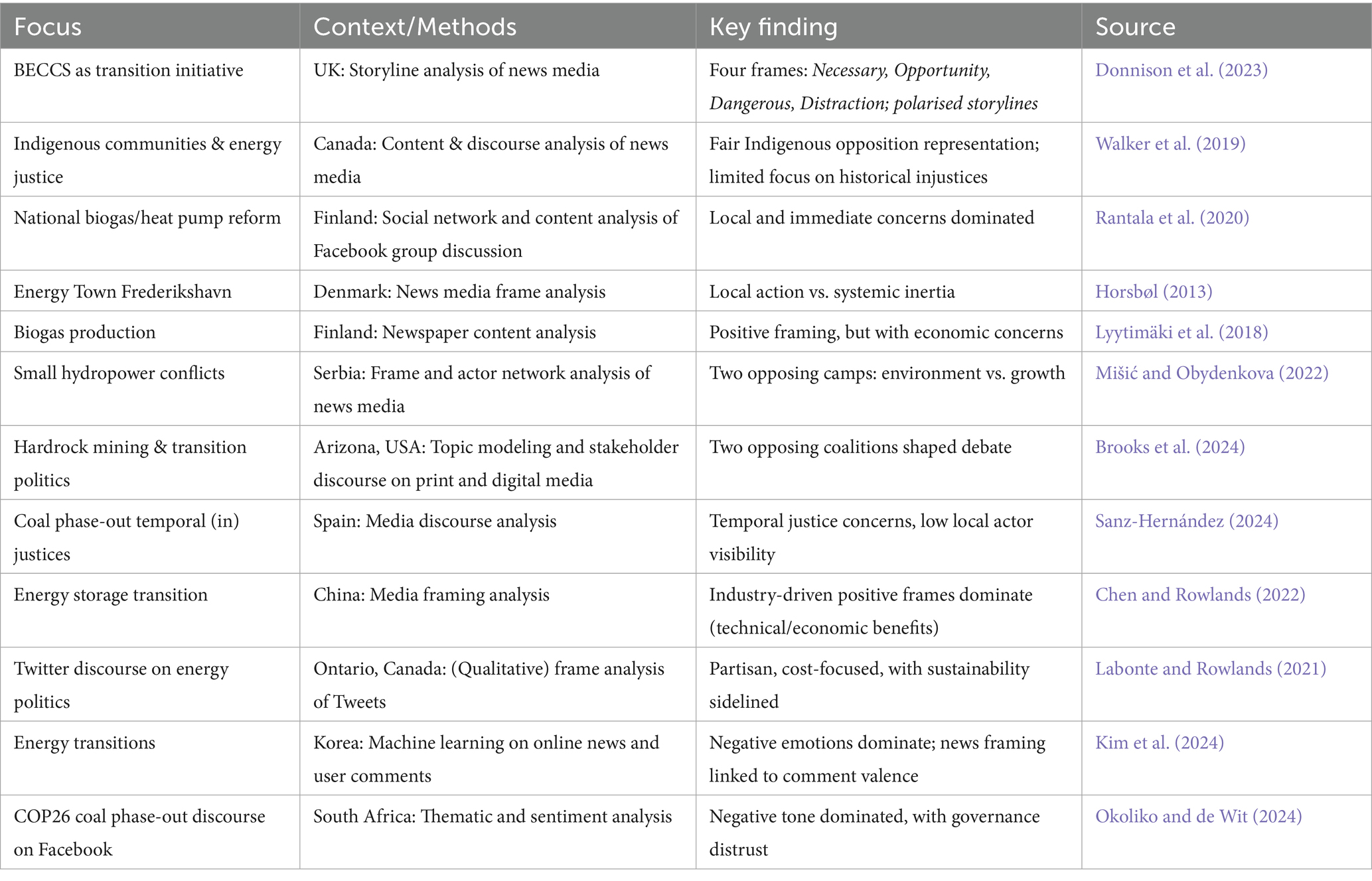

Despite the growing policy and scholarly focus on JT, limited research exists on how JT and decarbonization are framed and contested in mediated public discourse, particularly in the Global South (Patriani and Silva, 2025). Table 1 offers a snapshot of relevant media framing studies on energy transitions from existing literature. These studies highlight patterns of polarization and contestation. These include portrayals of new energy technologies as either essential or risky (Donnison et al., 2023), economic opportunity versus threat (Brooks et al., 2024), and as sites of competing stakeholder coalitions with divergent framings (Mišić and Obydenkova, 2022). Additionally, while traditional media often present positive framings of renewable energy technologies like biogas (Lyytimäki et al., 2018) and energy storage (Chen and Rowlands, 2022), social media platforms often surface more critical public sentiment on transition initiatives. For example, South African Facebook discussions around the COP26 coal phase-out deal reflect deep distrust in governance and negative perceptions of transition narratives (Okoliko and de Wit, 2024). Similarly, in Korea, online comment analysis of energy transition discourse shows that negative emotions, often shaped by news framing, dominate public discourse (Kim et al., 2024). Framing patterns also vary by geography and technology. Finnish media framed biogas positively but raised concerns about its economic viability (Lyytimäki et al., 2018). In Canada, indigenous opposition was fairly represented but historical injustices were underexplored (Walker et al., 2019). In Spain, coal phase-out debates exposed temporal justice concerns and limited local participation (Sanz-Hernández, 2024). In Australia, multiple coalitions divided over support for and against coal energy alternatives were found on X (formally known as Twitter) conversations, with opinions sharply divided over technological preferences (Arranz et al., 2024).

Despite these contributions, notable gaps remain. Much of the research focuses either on traditional (e.g., Berle and Broekel, 2025) or social media in isolation, (e.g., Arranz et al., 2024), with few comparative studies exploring how narratives circulate and are contested across platforms (e.g., Brooks et al., 2024). Moreover, most studies focus on high-income, Western contexts (e.g., Labonte and Rowlands, 2021), overlooking how JT discourses evolve in the Global South, where transitions intersect with energy poverty, fossil dependence, and historical inequalities (Salite et al., 2021).

This study addresses these gaps by examining how South Africa’s COP26 energy transition deal was framed across mainstream news media and Facebook. Specifically, we investigate how frame topics, justice dimensions, actor visibility, and temporal imaginaries manifest across these spaces. This cross-platform approach contributes to the evolving scholarship on just energy transitions and mediated public engagement in the Global South.

We pose four research questions:

1. What dominant frames characterize media versus Facebook discourse on South Africa’s COP26 JET deal?

2. How do procedural, distributive, recognitional, and restorative justice concerns manifest across these discursive spaces?

3. How do different stakeholders connect to specific frames and justice dimensions across media and Facebook discourse networks?

4. How do temporal perspectives differ between institutional and public imaginaries of the energy transition?

3 Methodology

This study employed a “partially mixed sequential dominant status design” (Leech and Onwuegbuzie, 2009, p. 271), integrating qualitative and quantitative methods in distinct phases, with qualitative analysis as the dominant strand. The first phase involved exploring how justice and transition were framed in mainstream media and Facebook discourse on South Africa’s COP26 JETP deal. The second phase applied the emergent frame categories to analyze how justice frames aligned with stakeholder visibility across platforms. This design allowed both deep contextual analysis and structured cross-platform comparisons.

3.1 Materials and sampling

We analyzed two primary data sources: South African mainstream news media articles and Facebook user comments referencing the COP26 energy transition deal. While news media in South Africa play a central role in shaping national narratives (Wasserman and Garman, 2014), they are often criticized for a bias toward elite and institutional narratives (Okoliko and de Wit, 2023), and concentration on wealthy demographics (Suliman, 2018). Including social media data allowed us to examine an alternative discursive space where grassroots commentary and political expression are more visible. Facebook was chosen for its high penetration in South Africa during the study period (Newman et al., 2021).

Sampling followed a two-pronged approach. First, we purposively collected media texts referencing the COP26 energy transition deal, using the LexisNexis database and a previously reported dataset by Okoliko and de Wit (2024). The LexisNexis database was queried by combining the terms COP26, $8.5 billion, energy, transition, and “South Africa” with the AND operator, filtered for newspapers published between November 1, 2021, and January 31, 2022, with source location set to South Africa. This period allowed for sufficient diffusion of news about the COP26 JETP deal. Of the 402 initial records, 90 were retained after removing duplicates and unrelated items through screening in ATLAS.ti (version 2025). The screening involved reading each uploaded file and collecting relevant items into a dedicated document group. Unrelated items excluded included those that discussed other COP26 topics (e.g., climate finance in general) but were not focused on the South Africa’s JETP deal, which is the interest of this paper. The full LexisNexis output report is available at https://doi.org/10.25413/sun.29606471.

The Okoliko and de Wit (2024) dataset originally contained 3,980 Facebook comments responding to 31 news posts from South African media outlets about the COP26 JETP deal. We identified 20 additional news articles from these posts that were not captured in the LexisNexis dataset, excluding nine that were unavailable or duplicates. This brought the combined media corpus to 110 items. For the Facebook comments corpus, we removed non-substantive entries (e.g., single-word comments such as “True” or “Exactly”) to ensure relevance, resulting in 3,715 usable comments. The dataset was extracted via ExportComments.com, a widely used online tool for obtaining publicly visible social media comments in Excel format compatible with ATLAS.ti (Wawrzuta et al., 2021; Schröter, 2022). To ensure feasibility of qualitative analysis, we adopted a pragmatic subsampling approach (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2007; Teddlie and Tashakkori, 2009), randomly selecting 22 news articles and 743 Facebook comments (approximately 20% of the total), proportionally drawn from all sources. This approach also justified the exclusion of duplicates from the LexisNexis dataset, as our primary strategy was qualitative—aimed at producing a manageable yet analytically rich dataset. Additionally, we analyzed all 31 Facebook post captions as part of the media dataset, treating them as formal media framing. Our dataset is described in detail and accessible at XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX. The analyzed media publications were drawn from 17 local news outlets, namely: Business Day, Cape Argus, Cape Times, Daily Dispatch, Daily Maverick, Daily News, Eyewitness News (EWN), Independent Online (IOL), Insider Sunday, News24, Pretoria News, Sowetan, Sunday Times, The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), eNews Channel Africa (eNCA), Times Live, and Briefly – South African News (see the breakdown in the Supplementary material, Section 1).

3.2 Analytical approaches

We distinguish between three interrelated concepts that guide our analysis. Foremost is framing, which refers to the selection and salience of specific issue dimensions to produce interpretive patterns (Entman, 1993; Brüggemann, 2014). In this context, frames are interpretive structures that highlight certain aspects of reality while downplaying others, guiding how issues are understood and discussed (Pan and Kosicki, 1993). They operate at multiple levels, from individual cognition to media texts, and are central to agenda-setting and meaning-making in public discourse (Vliegenthart and van Zoonen, 2011). Frames are our core analytical unit – we systematically coded how justice dimensions were invoked in relation to the JETP deal to shape understanding.

Second are narratives, which denote coherent interpretive storylines that cluster multiple frames into broader meaning-making patterns (van Hulst et al., 2025). Narratives provide coherence, assign roles and functions (e.g., supportive to a cause, villain), and often carry persuasive power, especially in shaping attitudes and behaviors. While full narrative analysis typically examines complete storyline structures with characters, plots, and morals (Crow and Lawlor, 2016), we focus on narrative function—how frames cluster to support, oppose, or critically interrogate the JETP deal. This enables us to identify how specific frame combinations serve to influence attitudinal interpretations (e.g., supporting, opposing, or critically assessing the JETP).

Lastly, we use discourse to refer to the broader communicative space and socially situated meaning-making practices within which frames and narratives circulate—a context of social practice that inherently embeds power relations (Fairclough, 2013). Our usage is sociological, focusing on how the institutionalized practices afforded by each platform investigated shape discursive outcomes (van Hulst et al., 2025). Thus, our analytical approach acknowledges that patterns of meaning are nested within hierarchical structures: frames constitute the lower-order units of analysis (specific interpretive moves), narratives represent higher-order patterns (clustered frames forming coherent storylines), and discourse denotes the macro-level context (platform-specific communicative ecosystems such as media discourse versus Facebook discourse).

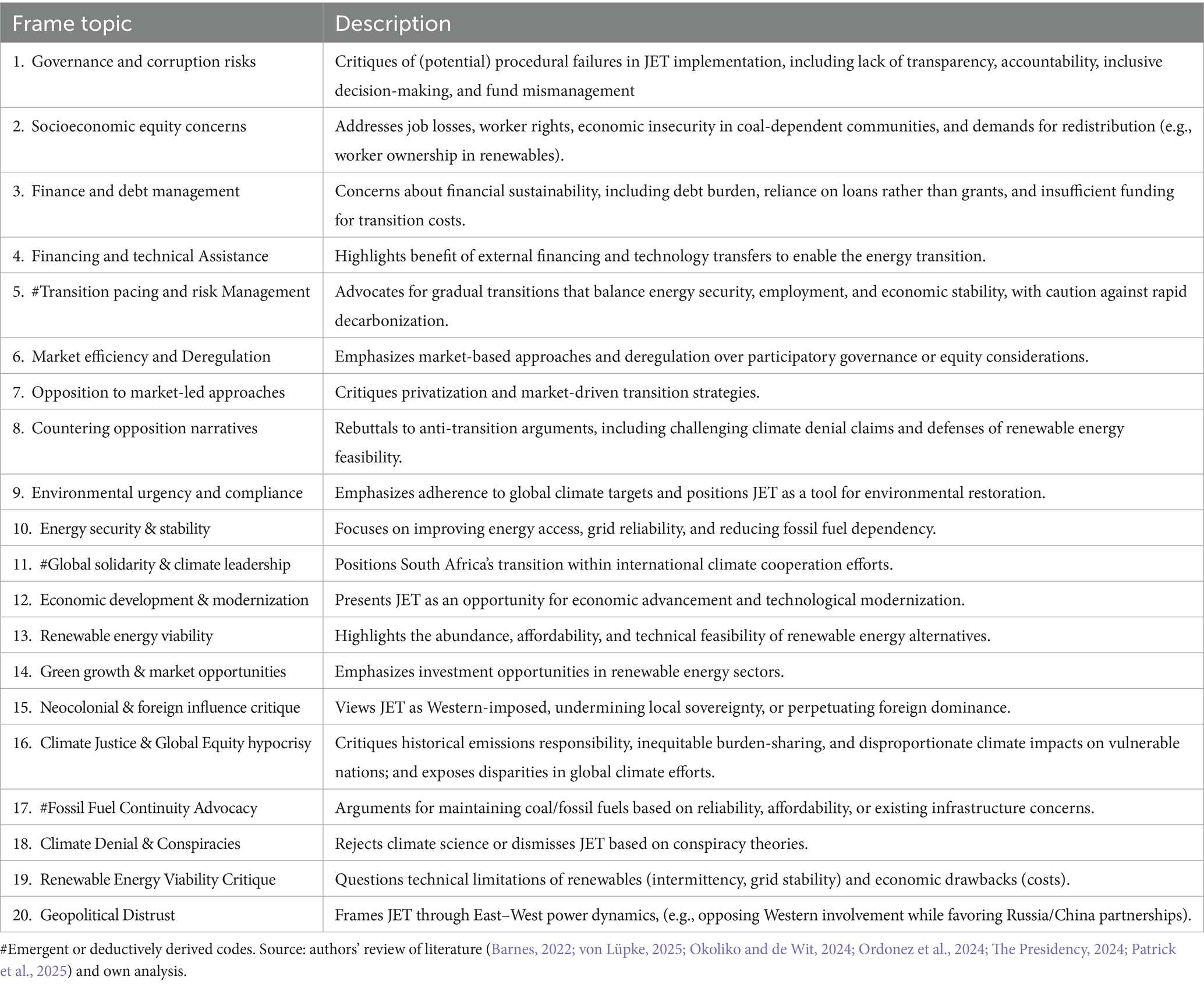

Following our research questions, analysis focused on four areas: (1) identifying frames, (2) mapping justice dimensions, (3) linking actors to frames and justice categories, and (4) analyzing temporal orientation across platforms. We conducted an issue-specific framing analysis (de Vreese, 2005), focusing on how justice-related arguments were articulated in the JETP discourse. Unlike generic framing typologies, this approach allowed detailed investigation of transition-specific frames (e.g., socioeconomic equity concerns, environmental urgency and compliance). Each media article, Facebook post caption, and comment was treated as a discrete unit of analysis. Using Brüggemann’s (2014, p. 75) concept of a “cultural frame repository,” we generated an initial list of frame topics based on prior South African energy transition research and similar studies. Table 2 presents the final frame typology, combining deductive codes from the literature with inductive codes emerging during analysis (marked with #).

Frames were then aligned with the four justice dimensions, following the iterative process:

• Procedural justice: Concerns about participation, transparency, and governance accountability (e.g., corruption, exclusionary decision-making) (Singh, 2023; Stark et al., 2023).

• Distributive justice: Fair distribution of costs and benefits, such as job impacts, debt, and energy access (Mirzania et al., 2023).

• Recognition justice: acknowledgement of identities, especially of marginalized voices, sovereignty, and local knowledge (Abram et al., 2022).

• Restorative justice: Addressing historical and ecological harms, including climate responsibility and reparation claims (Abram et al., 2022; PCC, 2022).

Our approach aligns with the common practice of categorizing frames by functional elements like those outlined by Entman (1993)—problem definitions, causal interpretations, moral evaluations, and treatment recommendations (Matthes and Kohring, 2008). However, given our focus on justice orientation, we clustered frames around the JET pillars and further categorized them by narrative functions: supporting the deal (e.g., environmental urgency), opposing the deal (e.g., neocolonial critique), or critically interrogating it (e.g., governance risks), following a similar approach used in Okoliko and de Wit (2024).

We also coded for stakeholder visibility. For the media dataset, we identified actors referenced or quoted in each text—government officials, Eskom representatives, experts, eNGOs, business actors, workers, and communities. Editorial pieces or journalist-driven interpretations were coded as “media.” Facebook comments were treated as expressions from a loosely bounded “networked public” (Friedland et al., 2006), given the lack of demographic identifiers.

To explore the relational dynamics between justice frames and stakeholder groups, we constructed a code co-occurrence matrix in ATLAS.ti and exported outputs to Gephi for network analysis. This process enabled visualization of stakeholder-frame associations and provided structural insight into discursive power dynamics operating across both platforms. The general co-occurrence operator was applied to capture all possible co-occurrence scenarios, including overlapping segments and cases where one quotation was contained within another. However, to prevent inflation of co-occurrence counts, we used the Cluster Quotations option in ATLAS.ti to register only the engagement of a larger quotation rather than counting each nested quotation separately (ATLAS.ti 25 Windows – User Manual, 2025). This approach was particularly suitable for our dataset, where larger text segments often contained multiple justice-related arguments made by the same actor. The resulting data tables for the combined, media-only, and Facebook-only co-occurrence datasets from ATLAS.ti, which served as input files for the Gephi network visualization, are presented in the Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Network analysis was selected as a complementary analytical approach because it enables systematic visualization of relational patterns between stakeholders and justice frames that qualitative coding alone cannot reveal. Specifically, network methods allow us to: (1) identify which actors are most central to justice discourse, (2) detect clusters of associated frames and stakeholders, and (3) compare structural differences in how elite versus grassroots voices engage with justice dimensions across platforms. For our purpose, we used Gephi, a widely used open-source software platform for interactive network visualization and analysis (Bastian et al., 2009).

In Gephi (version 0.10.1202301172018), we imported the co-occurrence data as an undirected weighted network. Nodes represented either stakeholder categories or justice dimensions, and edges represented their co-occurrence within the same text segments. Edge weights corresponded to co-occurrence frequency – that is, the number of times a particular actor-justice dimension co-occur in the coded data. These weights were stored as floating-point values (float data type) to preserve the numerical strength of associations. Edge thickness in visualizations was scaled proportionally to these weights, making more frequent associations visually prominent. Our network analysis employed a bipartite (two-mode) network structure, where actor nodes connect only to justice dimension nodes, not to other actors. This structure directly models our research question: which actors engage with which justice concerns? Bipartite networks are particularly suited to frame-actor analysis because they preserve the conceptual distinction between social actors and discursive frames while revealing their associational patterns (Borgatti and Everett, 1997). A detailed description of the complete Gephi analytical workflow is provided in the Supplementary material for full transparency and replicability.

It is important to state that our network analysis approach is descriptive and exploratory rather than inferential. Following mixed methods integration practices (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2007), we use network visualization and centrality metrics to systematically map, compare, and interpret structural patterns emerging from qualitative frame analysis. Consequently, the network metrics discussed below serve as comparative descriptive statistics—analogous to frequencies and distributions in content analysis—that enable cross-platform structural comparison. We do not employ statistical significance testing, as our research questions concern pattern identification and interpretation rather than hypothesis testing or causal inference (Freeman, 1978; Borgatti et al., 2025).

Other centrality measures reported here included (Majeed et al., 2020; Borgatti et al., 2025):

• Degree centrality: Frequency of direct connections, identifying which actors or justice dimensions were most frequently invoked together in discourse. Higher degree indicates broader engagement across justice concerns (for actors) or wider stakeholder invocation (for justice dimensions). Nodes with higher betweenness mediate between different discursive clusters.

• Betweenness centrality: Identifies nodes serving as bridges within the network and is calculated as the proportion of shortest paths passing through each node, indicating a node’s role as a bridge connecting other nodes.

• Eigenvector centrality: Weights node importance by the centrality of its connections, distinguishing nodes with many peripheral connections from those embedded in central discourse clusters. High eigenvector centrality indicates connection to other high-centrality nodes.

Gephi calculates normalized centrality values based on network size and structure, enabling within-network comparison of relative positions. Since absolute centrality scores are not directly comparable across networks of different sizes (Freeman, 1978), our interpretation focuses on: (1) relative rankings within each network (which actors are most/least central), (2) structural patterns (distributed vs. concentrated centrality), and (3) qualitative differences (which justice dimensions connect to which actor clusters). We do not compare absolute scores across platforms but rather interpret what centrality distributions reveal about each platform’s discursive organization.

3.3 Rigor and trustworthiness

We undertook several strategies to ensure analytical rigor across both qualitative and network analysis components. All coding in ATLAS.ti (2025) was performed by the first author through iterative rounds, which means that other credibility strategies rather than intercoder reliability metrics, were employed (Saldaña, 2013, p. 35; Cypress, 2017). Our comprehensive rigor and trustworthiness strategies included: (1) collaborative validation, where codebook definitions, coding decisions, and emergent categories were reviewed by all authors throughout analysis (Saldaña, 2013); (2) comprehensive audit trail, including the availability of complete ATLAS.ti project bundle with all codes, quotations, memos, and comments (Cypress, 2017); (3) iterative coding cycles with constant comparison to ensure internal consistency (Saldaña, 2013); (4) rich descriptive detail of processes and inclusion of validating quotations, enabling reader assessment of interpretive credibility (Morse, 2015); and (5) triangulation through two data sources (media and Facebook), mixed methods (qualitative and network analysis), and frame-stakeholder comparisons (Morse, 2015).

For network analysis, we ensured rigor through: (1) systematic co-occurrence extraction using ATLAS.ti’s query functions with the Cluster Quotations option to prevent artificial inflation from nested segments (ATLAS.ti 25 Windows – User Manual, 2025); (2) algorithmic consistency, where centrality metrics were calculated using Gephi’s standard, validated algorithms with documented parameters, eliminating researcher subjectivity in pattern identification (Bastian et al., 2009); (3) complete replication package, including ATLAS.ti project files, co-occurrence matrices, and Gephi project files, enabling independent verification of every analytical step (Barusch et al., 2011); and (4) cross-platform triangulation, analyzing three datasets (combined, media-only, Facebook-only) with identical procedures to validate patterns through comparison. This combination of iterative qualitative analysis, collaborative validation, algorithmic pattern detection, and transparent documentation meets established standards for rigor and trustworthiness in both qualitative and mixed methods research (Levitt et al., 2018).

4 Findings: discursive disparities and convergences

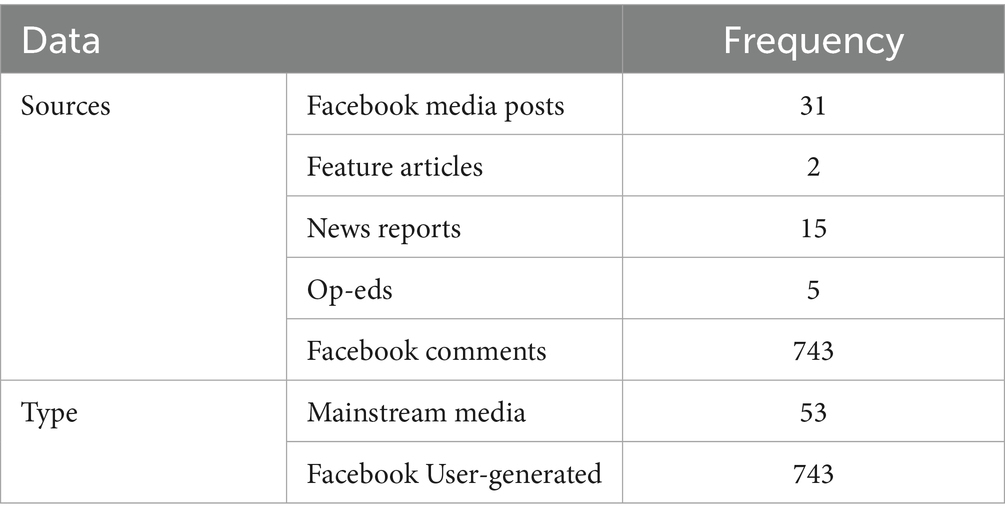

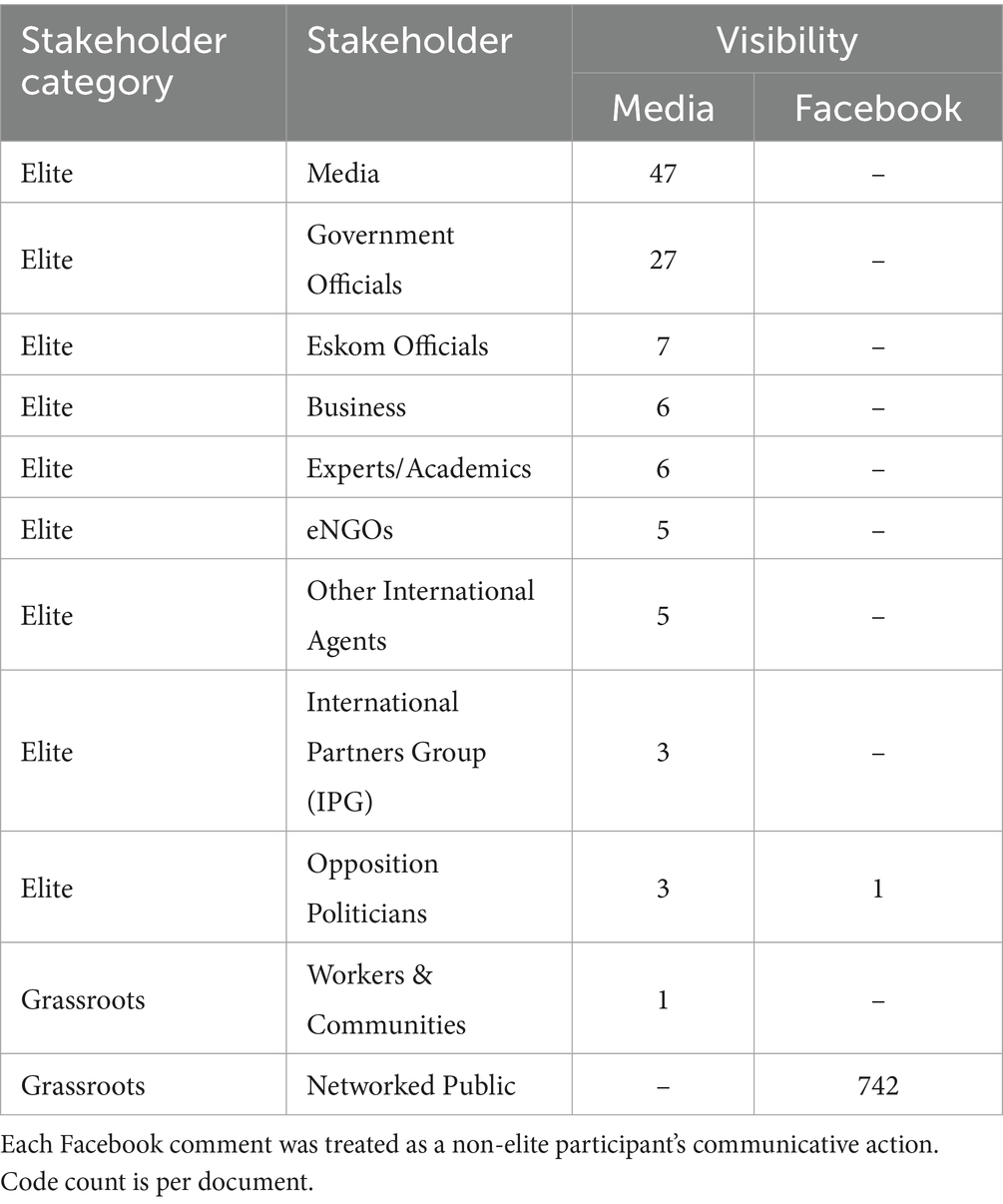

We analyzed 53 news media publications and 743 Facebook comments on the COP26 energy transition deal. Although Facebook entries outnumbered media items, differences in length and narrative style moderated this imbalance, as Facebook comments typically ranged from a phrase to a few sentences. Table 3 shows the distribution by type and genre.

4.1 Dominant frames in media vs. Facebook

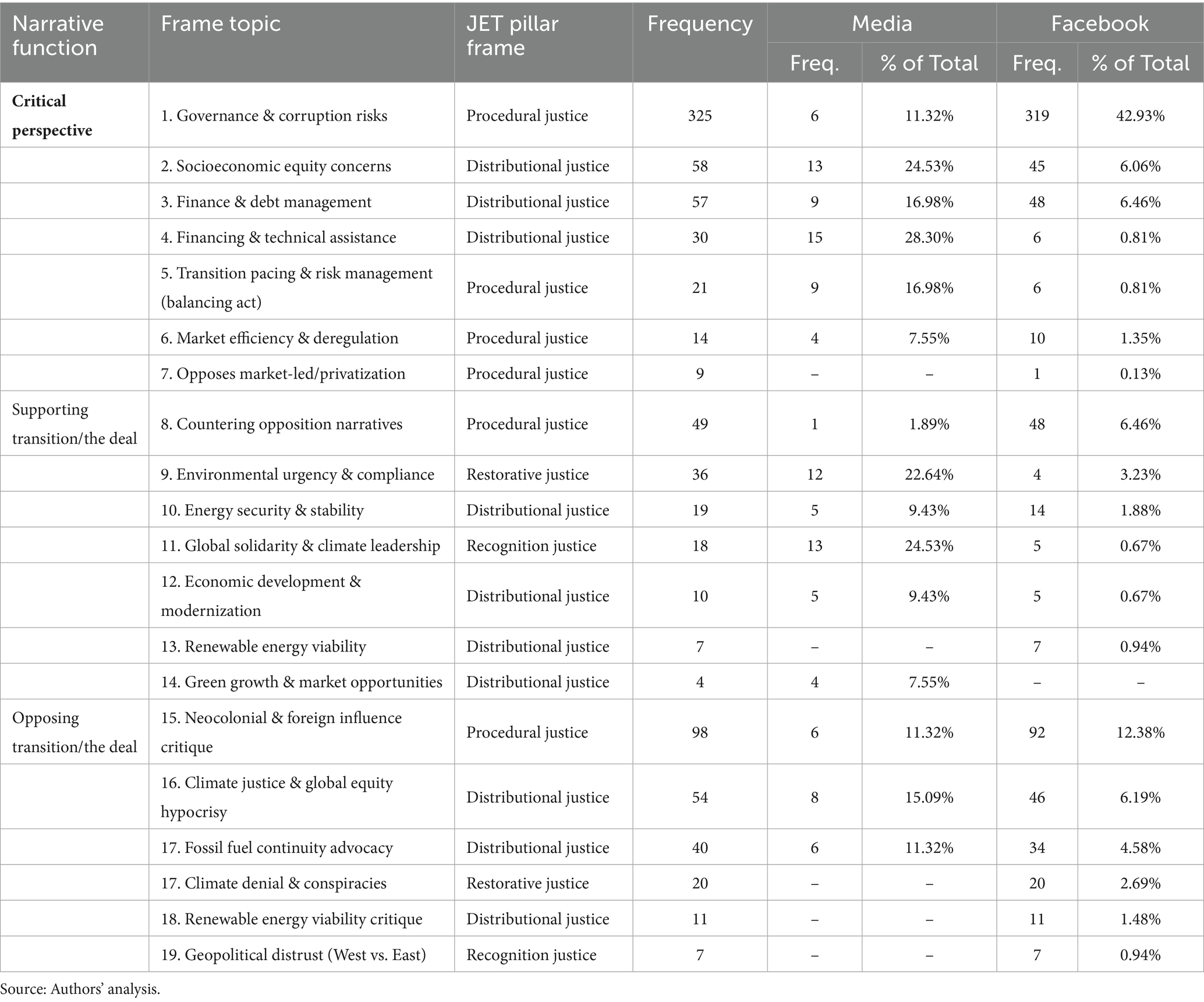

Our analysis identified 19 frame topics, grouped into three narrative functions: critical perspectives, support for the deal, and opposition to the deal. Table 4 summarizes their frequency across both platforms, highlighting discursive asymmetries and their alignment with the four JET pillars.

4.1.1 Critical narrative

This narrative cluster include frame topics such as governance and corruption risks, socioeconomic equity, finance and debt management, and transition pacing, accounted for a majority of Facebook frames (over 50%) but were less prominent in media content. Governance and corruption risks were the most frequent Facebook frame (43%) but appeared in only six media articles. For example, a Facebook user voiced concern that “the money will never ritch [reach] its destination it will be stolen (sic)” (Comment on eNCAnews Facebook post, November 2021), framing the deal as another opportunity for misappropriation.

4.1.2 Supportive narrative

Media discourse was more inclined toward supportive frames, especially on global solidarity and climate leadership (24.53% of media frames), and environmental urgency and compliance (22.64%). These framed the JETP as international cooperation and national leadership in climate action. For example, one article quoted President Ramaphosa describing the deal as a “watershed moment” of climate cooperation promising “energy security,” jobs and “investment” for South Africa (Cape Times, 2021, November 10).

4.1.3 Oppositional narrative

The oppositional narrative was shared across platforms but covered broader topics on Facebook. Both spaces featured neocolonial critiques (98 mentions), climate justice hypocrisy (54), and fossil fuel advocacy (40). A notable example was a ministerial warning against “a repeat of the structural adjustment regimes” that underdeveloped the continent (Dludla, 2021b), reflecting sovereignty concerns over external influence. Facebook added climate denial, renewable viability concerns, and geopolitical distrust.

4.2 Comparative patterns between discursive spaces

A key divergence between the two platforms lies in stakeholder visibility. Media coverage was dominated by elite actors: journalists (47 mentions), government officials (27), Eskom (7), business leaders (6), and experts (6). Workers and communities appeared only in one publication. In contrast, Facebook reflected 743 distinct user-generated voices, offering a broader grassroots perspective (see Table 5).

The news media framing dominated by institutional voices also centered the state, promoting a controlled, state-led pacing of the transition narrative. For example, the pacing of transition was framed as a matter of strategic discretion, as one government minister put it:

Africa should be allowed to manage its transition away systematically and not rush a switch to renewable energy sources. “I am not saying coal forever. I am saying let’s manage our transition step by step rather than being emotional” (Dludla, 2021a).

This advocacy for a paced transition reflects confidence in state institutions to manage the process. Facebook users challenged this narrative, highlighting governance failures and systemic distrust, as indicated by the heavy emphasis on governance and corruption risks (42.93%) in Facebook discourse. For instance, a user commenting on an eNCA post about the JETP deal remarked:

It means we will still be burning coal in 25 years time (sic), because all this money will be disappearing as soon as it hits South African soil (Comment on eNCAnews Facebook post, November 2021).

Consequently, the divergence between the two platforms reveals a discursive gap between state-led optimism and public disillusionment.

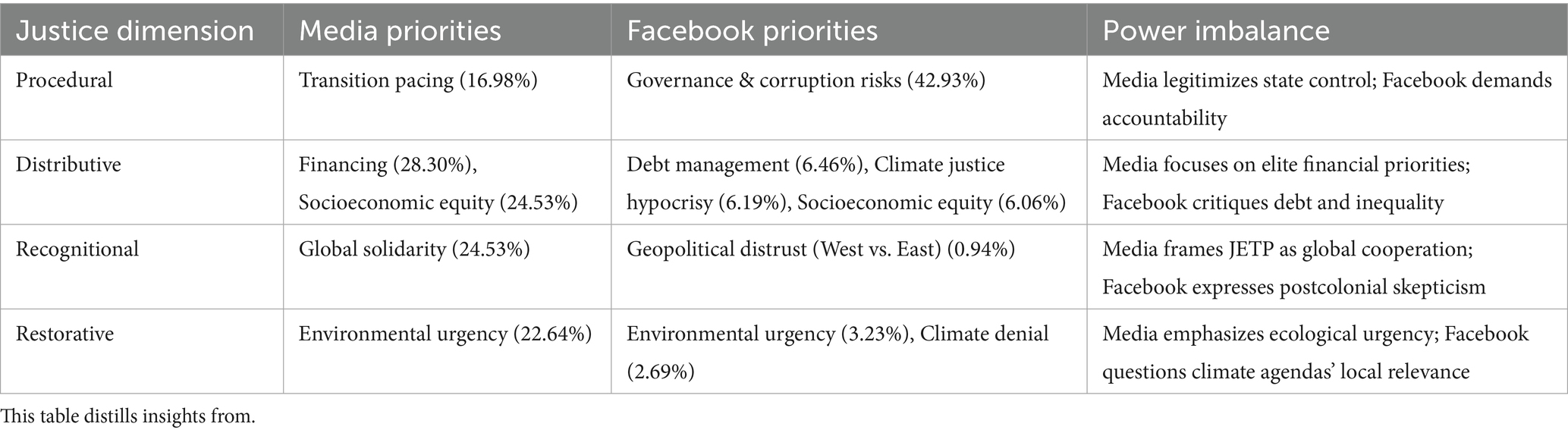

4.3 Justice dimensions and power imbalances

Mapping frames to JET pillars revealed that procedural justice dominated (58.2%), followed by distributive (32.7%), restorative (6.3%), and recognitional justice (2.8%). Table 6 compares how each platform addressed justice concerns, highlighting asymmetries.

Table 6. Representation of key frames across the four justice dimensions, showcasing power differential.

Justice framing across the two platforms revealed sharp contrasts in how the four JET pillars were embedded in narratives. Procedural justice dominated both spaces but with different emphases: media narratives framed transition pacing (17%) as a strategic, state-led process, while Facebook users focused overwhelmingly on governance and corruption risks (43%), demanding transparency and questioning state integrity.

Distributive justice followed, with the media highlighting finance and economic modernization, often in less concrete policy terms and with a focus on attracting funding and sectoral allocation. For instance, the then head of the government-owned utility company, André de Ruyter, remarked:

“The funds allocated would assist Eskom with the Just Energy Transition Partnership [to support South Africa’s decarbonization efforts]. The loan will also allow us to introduce electric vehicles and the hydrogen economy in the country” (Ndaba, 2021).

In contrast, Facebook comments critiqued debt burdens and socio-economic inequities, often anchoring arguments in lived experience. For instance, a netizen responding to another commenter on Facebook who had asked about who will pay for the loans said:

…your kids and your grandkids will pay for this. This is so sad ☺ (Comment on IOL News Facebook post, November 2021).

Others raised concerns regarding potential impacts on jobs and livelihood, as exemplified in the comment below:

No we don't support that idea why they push this agenda. Why we must(sic) be told by foreign countries to run our country. For now we don't need Nuclear power bcs(sic) many people will loose(sic) jobs. Starting from mines, trucks drivers who are transporting(sic) coal, Eskom workers, mine workers (sic). Noooo(sic) we say (Comment on eNCAnews Facebook post, November 2021).

Recognition justice featured mainly in media discussions, which invoked global solidarity to position South Africa as a Global South climate leader within international partnership. This is evidenced by the excerpt below:

US President Joe Biden said the partnership was evidence that the Group of 7 countries are living up to their pledges to assist the developing world on climate-related matters. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said the agreement was a "global first and could become a template on how to support just transition around the world (Paton, 2021).

Facebook users, however, framed the JETP as neocolonial imposition, reflecting postcolonial skepticisms, as evident in the comment below:

It very unfair, their countries are 'major powers' today because they exploited our resources, suddenly Africa is going towards self-determination and its ppl [people]are talking of opening the borders and trade within Africa, the same former colonialists who hv limited access to Africa are telling us we cannot utilize our resources? I get their environmental stance but why is it that the development trajectory must always come from our former oppressors, can Africa trust them to create global socio-economic policies to the benefit of Africa or each time they create policies it is to the detriment of African growth and development. Africa is the richest continent in terms of resources but has the most under-utilized as well, we have actually never really benefitted in our resources as much as the "outsiders" have, a move from a nat[ural] resources based economy will leave Africa at the bottom of the barrel, we do not have the capital or technology to shift from resource based economies, we are still recuperating from the division and colonialism they subjected us to. As the biggest polluters they must go the green way, we need a few more decades nathi[ural] to recover (Comment on SABC News Facebook post, November 2021).

Restorative justice was least visible but still showed platform divergence: media emphasized environmental urgency and climate commitments, while Facebook commenters expressed doubt about global climate targets, with some invoking climate denial. For instance, news media framed the JETP as an instrument for South Africa to “achieve the ambitious goals set out in its updated nationally determined contribution emissions goals” (Paton, 2021). In contrast, a commenter on Facebook remarked that “no such thing as climate change its all a lie [sic] (Comment on Briefly - South African News Facebook post, November 2021).

In reflecting platform differences, our analysis shows that justice framing is not only about what values are invoked but how they are interpreted and by whom. In the next section, we unpack this connection between the framing and the social actors.

4.4 Stakeholder-justice dimensions network

We used code co-occurrence analysis in ATLAS.ti and network mapping in Gephi to visualize stakeholder–justice dimension connections. The analysis confirmed the dominance of procedural justice (520 actor co-occurrences) and distributive justice (286), with restorative (61) and recognition justice (27) far less frequent. Stakeholder prominence varied by platform. Facebook’s networked public emerged as the most visible actor (728 co-occurrences), primarily linked to procedural (474) and distributive justice (198). Government officials followed (61 co-occurrences), mainly associated with distributive (36) and procedural justice (20). Media actors ranked third (45), reinforcing institutional narratives through strong links to distributive justice (28).

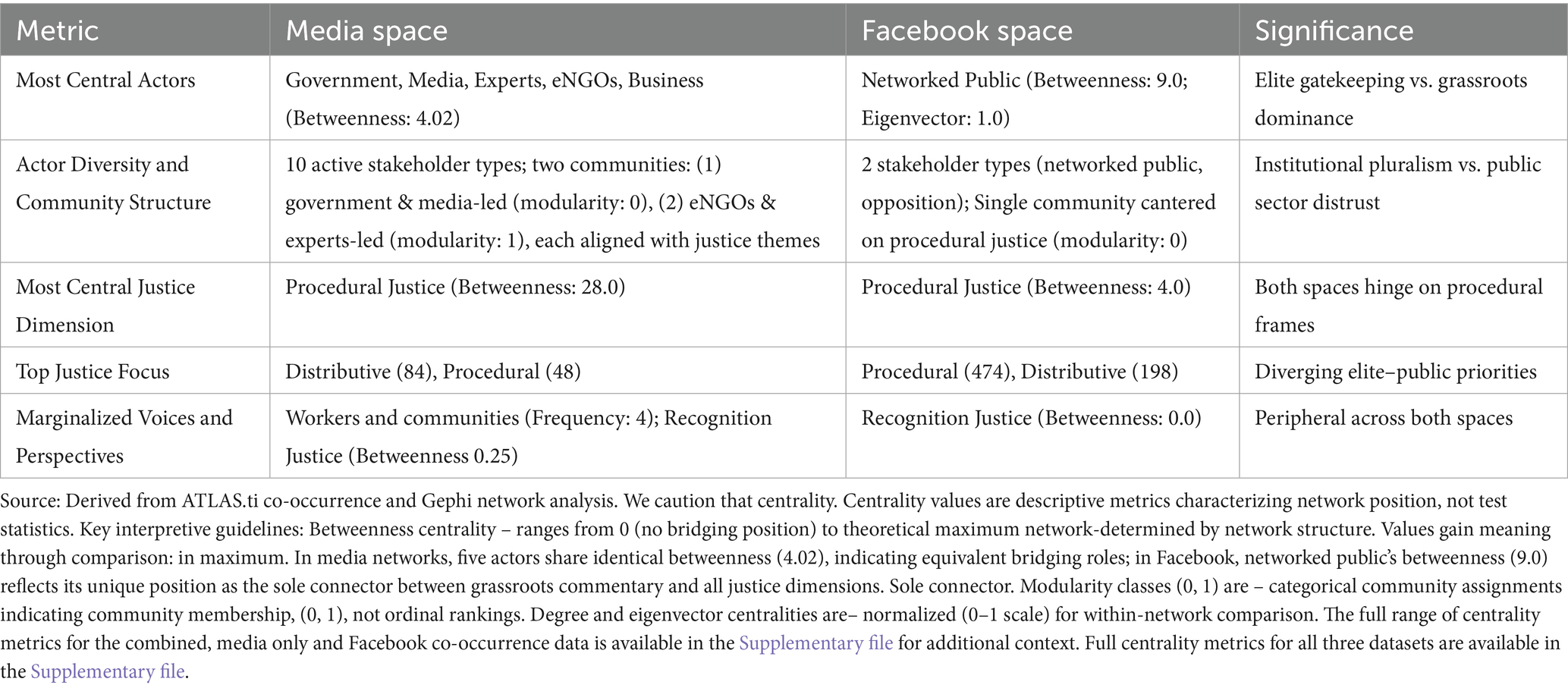

Gephi network visualizations (see Supplementary Figures 3–5) revealed clear platform differences (see Table 7 for metrics). Facebook’s network was structurally unified (modularity = 0), forming a single community centered on procedural justice, reflecting focused concerns with governance processes. In contrast, the media network was structurally differentiated, with multiple central actors—government, media, experts, eNGOs, and business—sharing identical betweenness centrality scores (4.02), suggesting a more plural but institutionally gatekept discourse. High eigenvector centrality (0.71) underscored elite actors’ embeddedness within the media space. Modularity analysis identified two media clusters: one centered on government and media (linked to procedural and distributive justice), the other around experts and eNGOs (linked to restorative and recognition justice). While distributive justice appeared most frequently in media content, procedural justice emerged as the key bridging frame across both platforms (1.00 eigenvector centrality for media and combined datasets, 0.63 in Facebook). Recognition justice remained peripheral (Betweenness: 9.75), mostly tied to international partners and government. Workers and affected communities were largely absent from the media network, indicating limited inclusion of directly impacted voices.

4.5 Temporal imaginaries

Temporal orientation further differentiated media and Facebook discourse. News narratives, especially those quoting government sources, framed the deal as a long-term investment in energy transformation and economic modernization. This future-oriented framing was often celebratory, emphasizing planning, institutional strategy, and developmental ambition. For example, Business Day described the deal as “one of the most eye-catching successes of COP26” (Denene, 2022), portraying it as a pathway to green industrialization.

In contrast, Facebook discourse was rooted in past grievances and present struggles. Commenters expressed deep skepticism toward future promises, frequently citing historical governance failures as grounds for distrust. One user remarked: “my biggest concern is all that will just disappear in a month as it happened to 500b” (Comment on eNCAnews Facebook post, November 2021), referencing past public fund mismanagement. Others highlighted coal’s role in their livelihoods: “What would happen to miners in Emalahleni? … those guys are my source of income” (Comment on eNCAnews Facebook post, November 2021). While both platforms acknowledged socio-economic concerns, the media used them to justify gradual implementation, whereas Facebook users invoked them to question the deal’s legitimacy and urgency. These divergent temporal imaginaries reflect broader discursive power asymmetries—where elite actors project future-focused optimism, and grassroots voices foreground lived experience, historical grievance, and economic precarity.

5 Discussion

Our comparative analysis of news media and Facebook discourse on South Africa’s COP26 JET deal reveals both convergence and divergence in how just transitions are imagined, contested, and narrated in institutional and grassroots discourse. Five interlinked themes emerged, which we discuss below: governance and trust tensions, economic justice and distribution, historical context versus global climate imperatives, stakeholder representation, and temporal perspectives.

Both media and Facebook foregrounded procedural justice, reflecting its centrality across platforms and in network patterns. This convergence suggests shared recognition of governance processes as crucial to transition success. However, while literature often frames procedural justice around participation and inclusion (Barnes, 2022; Diezmartínez et al., 2025; Radtke, 2025), our findings show divergent imaginaries of governance in the South African context. Media discourse presented procedural justice primarily through transition pacing, legitimizing state-led, gradual strategies framed as pragmatic and economically cautious. In contrast, Facebook discourse was saturated with distrust and criticism, centered on governance failures and elite capture. Over 40% of Facebook frames referenced corruption risks, often linking the JETP deal to past governance scandals, including COVID-19 fund mismanagement (Naudé and Cameron, 2021). This tension illustrates competing constructions of legitimacy: institutional actors appeal to planning and control, while grassroots voices demand accountability and responsiveness, reinforcing broader patterns of elite–public disconnect in South Africa’s governance landscape (Okoliko and de Wit, 2024). While transition pacing is widely recognized as the most viable pathway for Africa, given “the multiple challenges of energy security, economic growth, and affordable access” (Nsafon et al., 2023, p. 1), our findings underscore that its success hinges on addressing deep-seated governance concerns. Failure to confront issues of accountability, corruption, and public trust could undermine even the most carefully planned state-led strategies.

Distributive justice emerged as the second most prominent concern, echoing findings from Akrofi et al. (2024) on widespread distributive concerns related to transitions across 11 African countries. However, priorities diverged across platforms. Media narratives focused on international financing (28.3%), portraying it as essential for transition success. Facebook users, by contrast, raised debt management concerns (6.5%), questioning how new financial inflows might exacerbate inequality and future repayment burdens. Media texts framed distributive justice in sectoral terms—debating resource allocation between Eskom and emerging industries—while Facebook comments stressed community-level vulnerabilities, such as job losses and the fate of coal-dependent towns like Emalahleni. Energy security appeared in both spaces but was used differently: the media to support phased implementation, Facebook to question the deal’s urgency and relevance. These patterns highlight the need for distributive planning that moves beyond technocratic framings and addresses grassroots concerns (Akrofi et al., 2024). It also draws attention to the principle of “leaving no one behind” in energy transition, which arguably accounts for concerns of fossil-fuel producing nations and groups most vulnerable to transition (Ediger, 2025, p. 2).

A further theme was the tension between local historical contexts and universal climate narratives. Since the Paris Agreement, climate policy has adopted a moral framing built on urgency, solidarity, and collective responsibility (Ordonez et al., 2024; Koppenborg, 2025). South Africa’s JETP reflects this, with media framing the deal as a climate diplomacy success and symbol of international cooperation. Yet, Facebook commentary revealed deep skepticism toward these framings, often invoking neocolonial critique. Users viewed international partnerships as extensions of historical patterns of dependency and control. While such dissent appeared occasionally in media—mainly as quoted dissenting voices or within transition pacing frames—it was central in Facebook discourse. This reflects enduring postcolonial sensibilities and highlights how historical injustices shape public reception of international climate deals. These findings align with research on the geopolitical dimensions of energy partnerships and contested global justice framings (Stark et al., 2023; von Lüpke, 2025). Without acknowledging this historical baggage, framing strategies risk alienating already distrustful publics.

Stakeholder visibility patterns further illustrate the asymmetry in discursive power. Media coverage overwhelmingly featured elite voices—government, experts, Eskom, and business—while workers, communities, and civil society remained marginal or absent. Even eNGOs, often vocal in global just transition debates, appeared infrequently. Facebook, by contrast, served as a space for grassroots engagement, offering user-generated commentary grounded in lived realities. Although demographic details of users were unavailable, their perspectives foregrounded everyday concerns absent from institutional narratives. These disparities reflect structural constraints in media production, where journalistic norms and political-economic pressures privilege official sources (Horsbøl, 2013; Mbamalu, 2020; Okoliko and de Wit, 2023). Facebook discourse partially redressed this imbalance but direct influence on formal policymaking remains relatively unknown. This nuance invites considering multiple communication channels to engage different stakeholders, ensuring diverse voices inform decision-making (Benites-Lazaro et al., 2018).

Finally, contrasting temporal imaginaries emerged. Media narratives, shaped by institutional actors, projected a future-oriented vision, describing the JETP as a milestone on South Africa’s path to green development. Terms like “watershed moment,” “climate leadership,” and “investment opportunity” signaled optimism and strategic transformation. Facebook discourse, however, was rooted in past failures and present hardships. Users referenced corruption scandals, unmet promises, and economic precarity to question the credibility of future-focused claims. Many highlighted immediate survival concerns—such as job loss and energy insecurity—underscoring how temporal framing often mirrors power dynamics: those with institutional access project the future; those excluded invoke the past. As Sanz-Hernández (2024) observes, how communities perceive their past and present shapes their future imaginaries. In South Africa, the disconnect between elite visions of green growth and the lived experiences of ordinary citizens risks undermining policy legitimacy. Similar narrative mismatch is documented for the Netherlands case with regard to how energy future imaginaries are constructed in policy documents versus by ordinary citizens (Haarbosch et al., 2021), suggesting a lack of grassroots inclusion in the policymaking process. A truly just transition would require bridging these temporal narratives to address not only future aspirations but also past harms and present needs.

6 Conclusion

This study compared how South Africa’s COP26 just energy transition deal was framed across news media and Facebook discourse, focusing on frame topics, justice dimensions, actor visibility, and temporal imaginaries. Grounded in the premise that different platforms shape meaning-making in distinct ways, the findings affirmed expectations of divergence while also revealing key areas of convergence.

Both platforms centered procedural justice, yet with contrasting emphases. Mainstream media, reflecting institutional voices, framed it through the lens of strategic pacing and state-led control. Facebook users, by contrast, highlighted governance failures and systemic mistrust. Similar divergences appeared in stakeholder representation—where elite actors dominated media coverage, and grassroots concerns surfaced through user-generated commentary—and in temporal framing, with media projecting future-oriented optimism and Facebook foregrounding historical grievances and present-day struggles.

This study contributes to the growing body of justice-focused energy communication research, offering one of the few cross-platform analyses of media and social media framing. The inclusion of Facebook provides a more grounded understanding of how ordinary citizens engage with transition discourse, extending beyond the traditional focus on print media in the broader climate change communication literature (Schäfer and Schlichting, 2014; Comfort and Park, 2018; Okoliko and de Wit, 2020). The findings affirm the relevance of platform-specific framings for communication campaigns and policymaking, especially in contexts where inclusive governance and broad-based legitimacy are essential to a just transition.

Several implications emerge. First, the prominence of procedural justice—particularly concerns about corruption and transparency—underscores the urgency of participatory and accountable processes to rebuild public trust. Second, skepticism about international financing highlights the need for funding models that are not only transparent but also aligned with local development priorities and sensitive to historical contexts like colonial legacies. Third, the marginal visibility of workers and communities in mainstream media points to the importance of institutionalizing mechanisms that center affected voices. Social media, especially Facebook, emerges as an informal but valuable feedback space and should be considered within broader communication strategies, particularly in light of the increasing calls for energy democracy (Burke, 2018; Delina, 2018). Lastly, contrasting temporal imaginaries suggest the need for temporally inclusive policymaking—that is, one that integrates historical awareness, addresses immediate socio-economic concerns, and co-produces future visions with local communities.

This study has limits. It focused on two platforms and excluded others—such as WhatsApp, TikTok, YouTube, and community radio—that may reflect different publics, languages, or discursive styles. Future research exploring these diverse platforms can provide additional insights and could complement the largely qualitative (small sample) and interpretive approaches adopted in this research. The analysis also captured a specific moment around COP26; longitudinal studies of just energy transition discourse could explore how narratives evolve through implementation. Finally, future research could extend this work to other JETP countries or African contexts, advancing comparative insights into justice discourse in the Global South.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: SUNScholarData, available at: https://doi.org/10.25413/sun.29606471. Additionally, the ATLAS.ti project bundle containing all data management files (documents, codes, quotations and memos) and the Gephi project file are available via the same link.

Ethics statement

This study did not involve animals or direct human participation; all materials analysed were sourced from publicly accessible media platforms, including Facebook comments. Ethical approval was obtained from the Social, Behavioral and Education Research Ethics Committee (REC: SBE 34478) of Stellenbosch University, which classified the study as low risk. Informed consent was therefore not required. No demographic data were collected or used, and personal identifiers in quoted material were removed to ensure anonymity. This also means that quoted materials are cited in-text only, without inclusion in the reference list, to protect the anonymity of individuals.

Author contributions

DAO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MI: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the NRF South African Research Chair in Science Communication, Stellenbosch University.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and reviewers for their valuable comments and constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. For language editing to improve grammar and clarity. The name of the generative AI used is ChatGPT-3.5 (OpenAI).

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2025.1671160/full#supplementary-material

References

Abram, S., Atkins, E., Dietzel, A., Jenkins, K., Kiamba, L., Kirshner, J., et al. (2022). Just transition: a whole-systems approach to decarbonisation. Clim. Pol. 22, 1033–1049. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2108365

Akrofi, M. M., McLellan, B. C., and Okitasari, M. (2024). Characterizing ‘injustices’ in clean energy transitions in Africa. Energy Sustain. Dev. 83:101546. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2024.101546

Ali, A., Esposito, L., and Gatto, A. (2023). Energy transition and public behavior in Italy: a structural equation modeling. Resour. Policy 85:103945. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103945

Arlt, D., Schumann, C., and Wolling, J. (2023). What does the public know about technological solutions for achieving carbon neutrality? Citizens’ knowledge of energy transition and the role of media. Front. Commun. 8:5603. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1005603

Arranz, A. M., Askland, H. H., Box, Y., and Scurr, I. (2024). United in criticism: the discursive politics and coalitions of Australian energy debates on social media. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 108:102591. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2022.102591

ATLAS.ti. ti Scientific Software Development GmbH (2025). ATLAS.ti (Version 25.0.1.32924) [Computer software]. https://atlasti.com

ATLAS.ti 25 Windows – User Manual (2025). Code Co-Occurrence Table. ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH. Available online at: https://manuals.atlasti.com/Win/en/manual/CodeCooccurrence/CodeCooccurrenceTable.html?highlight=Cluster%20Quotations#code-co-occurrence-table-ribbon (Accessed October 7, 2025).

Barnes, J. (2022). Divergent desires for the just transition in South Africa: an assemblage analysis. Polit. Geogr. 97:102655. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102655

Barusch, A., Gringeri, C., and George, M. (2011). Rigor in qualitative social work research: a review of strategies used in published articles. Soc. Work. Res. 35, 11–19. doi: 10.1093/swr/35.1.11

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., and Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 3, 361–362. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v3i1.13937

Baur, D., Emmerich, P., Baumann, M. J., and Weil, M. (2022). Assessing the social acceptance of key technologies for the German energy transition. Energy Sustain. Soc. 12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13705-021-00329-x

Benites-Lazaro, L. L., Giatti, L., and Giarolla, A. (2018). Topic modeling method for analyzing social actor discourses on climate change, energy and food security. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 45, 318–330. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.07.031

Berle, E. C., and Broekel, T. (2025). Spinning stories: Wind turbines and local narrative landscapes in Germany. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 211:123892. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2024.123892

Borgatti, S. P., and Everett, M. G. (1997). Network analysis of 2-mode data. Soc. Networks 19, 243–269. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(96)00301-2

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., Johnson, J. C., and Agneessens, F. (2025). Analyzing social networks. London: SAGE Publications.

Brooks, C. F., Juanals, B., and Minel, J.-L. (2024). Environmental debates in the media: the case of Hardrock mining in Arizona and energy transition dilemmas. SAGE Open 14:67847. doi: 10.1177/21582440241267847

Brüggemann, M. (2014). Between frame setting and frame sending: how journalists contribute to news frames. Commun. Theory 24, 61–82. doi: 10.1111/comt.12027

Brulle, R. J., Carmichael, J., and Jenkins, J. C. (2012). Shifting public opinion on climate change: an empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S., 2002–2010. Clim. Chang. 114, 169–188. doi: 10.1007/s10584-012-0403-y

Burke, M. J. (2018). Shared yet contested: energy democracy counter-narratives. Front. Commun. 3:22. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00022

Cape Times (2021). Ramaphosa, world leaders announce pact to back switch to low-carbon economy. Cape Times.

Chen, Y., and Rowlands, I. H. (2022). The socio-political context of energy storage transition: insights from a media analysis of Chinese newspapers. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 84:102348. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102348

Climate Action Tracker (2025). South Africa. Available online at: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/south-africa/ (Accessed June 27, 2025).

Comfort, S. E., and Park, Y. E. (2018). On the field of environmental communication: a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. Environ. Commun. 12, 862–875. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2018.1514315

Crow, D. A., and Lawlor, A. (2016). Media in the policy process: using framing and narratives to understand policy influences. Rev. Policy Res. 33, 472–491. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12187

Crowe, J. A., and Li, R. (2020). Is the just transition socially accepted? Energy history, place, and support for coal and solar in Illinois, Texas, and Vermont. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 59:101309. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101309

Cypress, B. S. (2017). Rigor or reliability and validity in qualitative research: perspectives, strategies, reconceptualization, and recommendations. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 36, 253–263. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000253

Dahlgren, P. (2005). The internet, public spheres, and political communication: dispersion and deliberation. Polit. Commun. 22, 147–162. doi: 10.1080/10584600590933160

de Vreese, C. (2005). News framing: theory and typology. Informat. Design J. 13, 51–62. doi: 10.1075/idjdd.13.1.06vre

de Zeeuw, D. (2024). Post-truth conspiracism and the pseudo-public sphere. Front. Commun. 9:4363. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1384363

Delina, L. L. (2018). Can energy democracy thrive in a non-democracy? Front. Environ. Sci. 6:5. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2018.00005

Della Bosca, H., and Gillespie, J. (2018). The coal story: generational coal mining communities and strategies of energy transition in Australia. Energy Policy 120, 734–740. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.032

Diezmartínez, C. V., Sovacool, B. K., and Short Gianotti, A. G. (2025). Conflicted climate futures: climate justice imaginaries as tools for policy evaluation in cities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 120:103886. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2024.103886

Dludla, S. (2021a). Government unites on just energy transition partnership in bid to reduce carbon emissions. Pretoria News 9.

Donnison, C. L., Trdlicova, K., Mohr, A., and Taylor, G. (2023). A net-zero storyline for success? News media analysis of the social legitimacy of bioenergy with carbon capture and storage in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 102:103153. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2023.103153

Ediger, V. Ş. (2025). Leaving no one behind: just energy transition of fossil fuel-producing countries. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:6594. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1536594

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Fairclough, N. (2013). Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Freeman, L. C. (1978). Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Networks 1, 215–239. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7

Friedland, L. A., Hove, T., and Rojas, H. (2006). The networked public sphere. Javn. Public 13, 5–26. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2006.11008922

García-García, P., Carpintero, Ó., and Buendía, L. (2020). Just energy transitions to low carbon economies: a review of the concept and its effects on labour and income. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 70:101664. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101664

Gore, C. D., MacLean, L. M., Brass, J. N., Baldwin, E., Mitullah, W. V., and Porisky, A. (2025). Distributional justice and rapid green energy transitions: citizen experiences in Kenya. Environ. Res. Lett. 20:064025. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/add27d

Guevara-Cue, G. (2025). Climate justice: a view from the Latin American context. Environ. Sci. Pol. 171:104156. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2025.104156

Haarbosch, S. W., Kaufmann, M., and Veenman, S. (2021). A mismatch in future narratives? A comparative analysis between energy futures in policy and of citizens. Front. Sustain. Cities 3:4162. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2021.654162

Habermas, J. (2006). Political communication in media society: does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Commun. Theory 16, 411–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00280.x

Hägele, R., Iacobuţă, G. I., and Tops, J. (2022). Addressing climate goals and the SDGs through a just energy transition? Empirical evidence from Germany and South Africa. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 19, 85–120. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2022.2108459

Hanto, J., Schroth, A., Krawielicki, L., Oei, P.-Y., and Burton, J. (2022). South Africa’s energy transition – unraveling its political economy. Energy Sustain. Dev. 69, 164–178. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2022.06.006

Hedley, N., Smillie, S., Mzolo, S., van der Merwe, J., and Grant, L. (2024). The Road to a Just Energy Transition in South Africa. The Outlier. Available online at: https://roadtojet.theoutlier.co.za (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Heffron, R. J., and McCauley, D. (2018). What is the ‘Just Transition’? Geoforum 88, 74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.016

Horsbøl, A. (2013). Energy transition in and by the local media. The Public Emergence of an ‘Energy Town.’. Nordicom Rev. 19–34. doi: 10.2478/nor-2013-0051

IEA (2025). Global energy review 2025. IEA. Available online at: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025/coal (Accessed April 25, 2025).

IEA (n.d.). South Africa - Countries & Regions. International Energy Agency. Available online at: https://www.iea.org/countries/south-africa (Accessed May 1, 2025).

Kim, B., Yang, S., and Kim, H. (2024). Voices of transitions: Korea’s online news media and user comments on the energy transition. Energy Policy 187:114020. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2024.114020

Koppenborg, F. (2025). Phase-out clubs: an effective tool for global climate governance? Environ. Politics 1, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2025.2483070

Labonte, D., and Rowlands, I. H. (2021). Tweets and transitions: exploring Twitter-based political discourse regarding energy and electricity in Ontario, Canada. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 72:101870. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101870

Leech, N. L., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2009). A typology of mixed methods research designs. Qual. Quant. 43, 265–275. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., and Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. Am. Psychol. 73, 26–46. doi: 10.1037/amp0000151

Lyytimäki, J., Nygrén, N. A., Pulkka, A., and Rantala, S. (2018). Energy transition looming behind the headlines? Newspaper coverage of biogas production in Finland. Energy Sustain. Soc. 8:15. doi: 10.1186/s13705-018-0158-z

Majeed, S., Uzair, M., Qamar, U., and Farooq, A. (2020). “Social Network Analysis Visualization Tools: A Comparative Review” in 2020 IEEE 23rd International Multitopic Conference (INMIC), 1–6. doi: 10.1109/INMIC50486.2020.9318162

Matthes, J., and Kohring, M. (2008). The content analysis of media frames: toward improving reliability and validity. J. Commun. 58, 258–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

Mbamalu, M. (2020). Newspaper coverage of renewable energy in Nigeria: frames, themes, and actors. SAGE Open 10:2158244020926192. doi: 10.1177/2158244020926192

Mirzania, P., Gordon, J. A., Balta-Ozkan, N., Sayan, R. C., and Marais, L. (2023). Barriers to powering past coal: implications for a just energy transition in South Africa. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 101:103122. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2023.103122

Mišić, M., and Obydenkova, A. (2022). Environmental conflict, renewable energy, or both? Public opinion on small hydropower plants in Serbia. Post-Commun. Econ. 34, 684–713. doi: 10.1080/14631377.2021.1943928

Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical Analysis of Strategies for Determining Rigor in Qualitative Inquiry. Qual. Health Res. 25, 1212–1222. doi: 10.1177/1049732315588501

Naudé, W., and Cameron, M. (2021). Failing to pull together: South Africa’s troubled response to COVID-19. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 15, 219–235. doi: 10.1108/TG-09-2020-0276

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Schulz, A., Andı, S., Robertson, C. T., and Nielsen, R. K. (2021). Reuters institute digital news report 2021, 73. Available online at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2021 (Accessed July 5, 2021).

Nkata, Z. (2022). Towards “just” energy transitions in unequal societies: an actor-centric analysis of South Africa’s evolving electricity sector. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Nsafon, B. E. K., Same, N. N., Yakub, A. O., Chaulagain, D., Kumar, N. M., and Huh, J.-S. (2023). The justice and policy implications of clean energy transition in Africa. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:9391. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1089391

Okoliko, D. A., and de Wit, M. P. (2020). Media(ted) climate change in Africa and public engagement: a systematic review of relevant literature. Afr. J. Stud. 41, 65–83. doi: 10.1080/23743670.2020.1770114

Okoliko, D. A., and de Wit, M. P. (2021). From “communicating” to “engagement”: Afro-relationality as a conceptual framework for climate change communication in Africa. J. Media Ethics 36, 36–50. doi: 10.1080/23736992.2020.1856666

Okoliko, D. A., and de Wit, M. P. (2023). Climate Change, the Journalists and “the Engaged”: Reflections from South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya. Journal. Pract. 19, 581–608. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2023.2200744

Okoliko, D. A., and de Wit, M. P. (2024). Exploring transition tensions in public opinion on the COP26 coal phase-out deal for South Africa as expressed on Facebook. Environ. Commun. 18, 1124–1146. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2024.2353081

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Leech, N. L. (2007). A call for qualitative power analyses. Qual. Quant. 41, 105–121. doi: 10.1007/s11135-005-1098-1

Ordonez, J. A., Vandyck, T., Keramidas, K., Garaffa, R., and Weitzel, M. (2024). Just energy transition partnerships and the future of coal. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 1026–1029. doi: 10.1038/s41558-024-02086-z

Otlhogile, M., and Shirley, R. (2023). The evolving just transition: definitions, context, and practical insights for Africa. Environ. Res.: Infrastruct. Sustain. 3:013001. doi: 10.1088/2634-4505/ac9a69

Pan, Z., and Kosicki, G. (1993). Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit. Commun. 10, 55–75. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

Patriani, T. Y., and Silva, E. C. d. M. (2025). Between narratives and climate justice: Globo and UOL’s coverage of activism at the COPs. Ambient. Soc. 28:e00093. doi: 10.1590/1809-4422asoc00932vu28l3oa

Patrick, S. M., Shirinde, J., Kgarosi, K., Makinthisa, T., Euripidou, R., and Munnik, V. (2025). Just energy transition from coal in South Africa: a scoping review. Environ. Sci. Pol. 167:104044. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2025.104044

PCC (2022). A Framework for a Just Transition in South Africa. Presidential Climate Commission. Available online at: https://www.climatecommission.org.za/just-transition-framework (Accessed April 25, 2025).

Radtke, J. (2025). Understanding the complexity of governing energy transitions: introducing an integrated approach of policy and transition perspectives. Environ. Policy Gov. 35, 595–614. doi: 10.1002/eet.2158

Rantala, S., Toikka, A., Pulkka, A., and Lyytimäki, J. (2020). Energetic voices on social media? Strategic niche management and Finnish Facebook debate on biogas and heat pumps. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 62:101362. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2019.101362

Rasmussen, T. (2014). Internet and the political public sphere. Sociol. Compass 8, 1315–1329. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12228

Saier, A. (2019). Governments Prepare to Respond to Calls for Greater Climate Ambition at Bonn Conference. United Nations Climate Change. Available at: https://unfccc.int/news/governments-prepare-to-respond-to-calls-for-greater-climate-ambition-at-bonn-conference (Accessed June 13, 2019).