- Graduate School of Education, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, United States

Social media posts in a Facebook group organized around the issue of refusing high-stakes testing in New Jersey were analyzed to understand how individuals and organizations use social media to engage in political protest against educational policies. Facebook posts were categorized by their theme (reasons for opposing high-stakes testing), whether they discussed political protest tactics (both traditional and virtual), and whether they contained web links to other social media sites. Interviews with Test Refusal Movement participants were conducted to supplement the Facebook analysis by providing a more nuanced understanding of how movement participants navigate online affinity spaces and how new forms of protest have transformed but not replaced traditional political protest against policies.

Statement of Purpose

This study analyzes how members and organizations in the Test Refusal Movement in the state of New Jersey in the U.S. used social media to engage in political protest. The national movement against high-stakes testing is a unique historical situation that does not fit neatly into existing theories of social movements or theories of political protest and policymaking. Individuals and organizations across the political spectrum came together to form a coalition (Whittier, 2014; Sagi, 2015) that mobilized around the issue of high-stakes testing. The protest grew in size and intensity at an unexpected rate from 2014 to 2016. Social media played a critical role in the mobilization against high-stakes testing; however, traditional organizations and electoral politics were clearly at the center of the Test Refusal phenomenon, in which students or their parents refused to take the state-mandated tests. This research study argues for theoretical synthesis and expansion of the current literature on political protest and social media in order to capture the complex dynamics of political protest in modern society. Previous research on the Test Refusal Movement fails to fully address the complexity of the motivations for protest and does not adequately explain the wide variation of test refusal rates within the state. This study addresses this gap in the research.

New Jersey was one of the states that did not meet its 95 percent participation goal for state testing in 2016 as required by the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Several studies (e.g., Bennett, 2016; Supovitz et al., 2016) have examined the unique political situation that led to the rapid rise of a Test Refusal Movement in New Jersey. The current study uses systematic grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) to focus on the role of social media in the mobilization of activists and on the growth of and impact of the Test Refusal Movement1.

Through an examination of how individuals and organizations use social media, the study addresses the following research questions:

• What are the motivations and political ideologies of the individuals and organizations in the Test Refusal Movement?

• What strategies and tactics are used by the individuals and organizations in the Test Refusal Movement?

• How do individuals and organizations in the Test Refusal Movement recruit new members, spread its message, and interact with policymakers at the local and state levels?

Mobilization, Political Protest, and Social Media

Sociologists and political scientists have come to recognize the complexity of political action. They have rejected the false dichotomy of institutional politics and non-institutional politics and have recognized that political protest and social movements are an integral part of institutional politics. Political protest occurs in a wide variety of contexts, including political movement organizations, alternative institutions, movements within institutions, cultural challenges, and individual social action (McAdam, 1982; Cohen, 1985; Goodwin et al., 2001; McAdam and Tarrow, 2013; Staggenborg, 2013; Fisher, 2015). Policies transform because of a process of changes in the problem stream, the policy stream, and the political stream, all of which are influenced by individual and organizational political protest (Kingdon, 2010). Network approaches add to this by addressing issues of power and interdependence among organizations as well as interactions among the whole spectrum of actors. These studies examine how leaders participate in networks, how structures (including those that are Internet-based) are related to a social movement's ability to sustain itself, and how organizations share tactics and knowledge.

Many studies (Fenger and Klok, 2001; Diani, 2013; Soule, 2013; Baumer and Van Horn, 2014; Passy and Monsch, 2014; Staggenborg, 2015) look at why people engage in political protest and what factors make protest more likely to have an impact. Research suggests that a diversity of tactics and goals predicts movement success. Movements can have multiple targets including the state and corporations (Armstrong and Bernstein, 2008). People are more likely to protest against the state (or other targets) when they are angered by things they believe are infringing on their rights or when they feel that the government threatens their safety, health, or property (Baumer and Van Horn, 2014). Culturally focused studies of social movements examine the relationships among beliefs, identity, group consciousness, and mobilization. These studies explore through framing and cultural lenses the processes by which symbolic challenges to the dominant culture occur and clarify the relationship between social protest and moral action (Cohen, 1985; Offe, 1985; Touraine, 1985; Goodwin et al., 2001; Taylor, 2013).

Some evidence shows that, in recent years, people have been moving away from traditional political participation and that protest is less frequently based on identity and more frequently based on specific issues (Hutter and Kriesi, 2013). Those who are simultaneously insiders and outsiders (Armstrong and Bernstein, 2008) often initiate change, and disparate groups that do not share a belief system sometimes organize around an issue (Lugg and Robinson, 2009; Staggenborg, 2015). Sometimes organizations and individuals collaborate based on their beliefs about how the system needs to be changed (Lugg, 2001; Friesen, 2015). Often these “strange bedfellows” (i.e., ideologically disparate organizations and individuals) come together to form “event coalitions” focused on a shared goal. These event coalitions converge around particular actions or tactics (Whittier, 2014; Sagi, 2015).

Social media has changed traditional mobilization structures, including how members of movements are recruited, how communication takes place, how members interact, and what type of protest activities members engage in. Social media has increased the speed and interactivity of communication and has transformed the landscape of political protest. Virtual protest can influence institutional politics by creating symbolic change, highlighting economic disparities, identifying targets of blame, and keeping the issues in the news and in the broader political conversation. Social media serves as a tactical tool (a means to disseminate information, coordinate action, and publicize the cause) as well as an emotional conduit (a place to develop identity, share emotions, and symbolically construct a sense of togetherness among activists) (Appadurai, 1996; Shirky, 2011; Amenta, 2012; Castells, 2012; von Stekelenburg and Roggeband, 2013; Wolfson, 2014). The use of social media makes it impossible to separate communication from organization because people mobilize in both virtual and physical space (Gerbaudo, 2012; Schradie, 2014).

Social media sites such as Facebook can create a populist identity and a sense of solidarity, which allows people to develop a common sense of indignation, anger, and frustration as well as a perception of shared victimhood. However, the Internet can also be used by the state or by powerful groups to fight against social movements and shut them down (Castells, 2012; McChesney, 2013). There are large differences among social classes in both the use of technology and the tendency to engage in political protest. Technology may have actually increased the separation among social classes because of the gap between the “information-rich” and the “information-poor” (Gitlin, 1998; Rootes, 2013; Wolfson, 2014). People with more resources tend to feel that they have efficacy and are more likely to mobilize. Fear and lack of discretionary time to engage in protest keep the lower classes from protesting: The state is able to repress them with more success (Earl and Kimport, 2011; Castells, 2012;McChesney, 2013).

Earl and Kimport (2011) argue that the Internet has two types of effects on social protest that are a rupture from previous theorizing and research on social movements. They call the first type of effect, Supersize Effects: The Internet reduces the cost of protest (both time and money), increases the speed in which mobilization occurs (transmission of information and communication), and changes the scale on which mobilization takes place. They call the second type of effect, Theory 2.0 Effects: The Internet has led to fundamental changes in the underlying processes driving participation and organization. In contrast to what has been characteristic of earlier social movements, which organized at in-person meetings and engaged in physical types of protest such as demonstrations, rallies, and sit-ins, we now see a new digital repertoire of e-tactics (organization that occurs without physical co-presence). This can include a range of activities: large-scale e-tactics produced by individuals or small groups; short, sporadic, and episodic campaigns as well as sustained protest; and specific as well as broad targets and goals. Polletta (2011) argues that, even though Earl and Kimport's theory predates the rise of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, it still holds up well, and, in fact, the new social media may foster a new kind of virtual collective identity that may be stronger in some ways than the traditional type.

While it seems clear that social media has had a profound effect on both the modes and outcomes of political protest, one of the challenges in determining the effect of social media is the porous boundaries of the Internet and other social media sites. One way to address the methodological challenge of studying the fluid and dynamic nature of social media is to draw on Gee's (2004) concept of affinity spaces. An affinity space is organized around a common endeavor and allows self-directed, multi-modal, and dynamic participation. Affinity spaces involve many interconnected sites, forms of social media, and discussion platforms. Socializing plays a big role in affinity spaces, and leadership varies within and across portals (Lammers et al., 2012). This article examines the affinity space created by the Test Refusal Movement. This political opposition originated with people across the political spectrum who organized around an issue and protested against multiple targets including local, state, and federal governments, the public education system, and corporations. This article documents the Supersize Effects (the faster, cheaper, and larger scale of political mobilization) as well as the Theory 2.0 Effects (the emergence of fundamentally different types of political mobilization) that occurred during the Test Refusal Movement (Earl and Kimport, 2011).

A History of the Protest Against High-Stakes Testing

Negativity toward high-stakes testing became more widespread after the adoption of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) in 2002. Anti-testing sentiment became even more intense and pervasive with the introduction of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and U. S. President Barack Obama's Race to the Top (RTT) program in 2009, which linked teacher evaluation to high-stakes test scores and greatly increased the focus on and impact of high-stakes testing. It took a few years of implementation of state waivers for NCLB and RTT before the full impact of the programs was apparent to people both inside and outside of the education profession. Although there were scattered protests and boycotts at that time, it was not until 2012 when the depth and breadth of protest began to increase (Schaeffer, 2012). In 2012, FairTest, The National Center for Fair and Open Testing, spearheaded a national resolution protesting high-stakes testing; professors in New York started their own petition against the use of high-stakes test data in the teacher evaluation system; the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) as well as some school boards in various states passed resolutions; and some administrators across the country began to speak out in protest against high-stakes testing. Further, the mainstream media began to cover the protests (Strauss, 2012).

For the next two years, there were small pockets of protest in various parts of the country. However, there was no dramatic change in the intensity of protest until states began implementing the new computer-based CCSS-aligned tests (Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers [PARCC] and Smarter Balanced) that were to be part of the teacher evaluation systems required by RTT. The teacher evaluation system was controversial for many reasons, including the fact that standardized tests, which had been designed to assess student performance, were now being used to measure teacher and school leader performance. In 2014 New York State, which chose to implement its version of PARCC tests a year earlier than most states and which had made test scores 50 percent of teachers' scores, was at the forefront of the Test Refusal Movement. More than 60,000 students across the state refused to take the test that year. Many teachers in New York were outspoken, encouraging parents and students to refuse the test, and the union organized events and a robo-call campaign to encourage test refusal (Strauss, 2015a).

In the following year, most other states across the country introduced the PARCC and Smarter Balanced tests. While some states ended up dropping out of the testing consortiums, most administered the tests in the spring of 2015. Opinion polls showed that, nationwide, 64 percent of people thought that children were subjected to too many standardized tests—this included strong majorities from all major demographic groups as well as diverse political affiliations (Guisbond et al., 2015). The Test Refusal Movement mushroomed, making national news and getting attention from federal and state politicians (Supovitz et al., 2016). Around the country, parents and students organized petitions, rallies, and public forums; students refused to take tests; and teachers demanded testing reform (Guisbond et al., 2015). In New York State, an estimated 20 percent of students refused the state exams (Buckshot, 2015). Estimates for New Jersey averaged 11 percent, with the highest rates of refusals at the high school level and in districts with higher socio-economic status (Supovitz et al., 2016). Across the country, state and local education officials reacted to try to stop the refusals, going so far as to threaten loss of funding and removal of school board members (Strauss, 2015b; Ujifusa, 2015). As states refused to acknowledge the right to “opt-out,” parents asserted their constitutional right to have children refuse the test, and members of the anti-testing movement made a concerted effort to change the language of protest from “opt-out” to “refusal.” The federal government began to threaten states with loss of Title I funding if they did not have 95 percent participation in tests across all subgroups (Buckshot, 2015).

Facing increasing bipartisan opposition to high-stakes testing, the Obama administration called for a cap on assessment that would limit the total amount of classroom instructional time spent on testing to two percent (Zernike, 2015). Teachers' unions declared this a victory: Randi Weingarten, the president of the AFT, was quoted as saying, “Parents, students, educators, your voice matters, and was heard” (Zernike, 2015). A new version of NCLB, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), passed with bipartisan support in the U. S. House of Representatives and the U. S. Senate and was signed into law by President Obama on December 10, 2015 (Klein, 2016). Politicians claimed that ESSA rolled “back the federal footprint of K-12 education” (Klein, 2016, p. 1). ESSA allowed states to determine how much tests should count for accountability purposes and to determine their own “opt-out” laws as well as consequences for schools or districts that have high refusal rates (Klein, 2016, p. 1). However, as the details of ESSA were unveiled, the Test Refusal Movement argued that ESSA did not fundamentally change the problems: The law retained the grades 3–11 annual testing requirements as well as the 95 percent participation requirement. It also allowed states to be more punitive than what was prescribed under NCLB should they choose to do so.

Shortly after the passage of ESSA, the federal government issued a warning letter to 13 states that had “poor” participation in state testing in 2015. The letter asked the states how they planned to address their low local or state participation rates. The federal government threatened that any state that failed to address this issue would lose a portion of its Title I Administrative federal funds. Some states threatened that districts could lose state funds as well (Ujifusa, 2015). States immediately responded but in very different ways. Some states announced that test scores would no longer count toward teacher evaluation metrics while other states threatened districts with low test participation with Corrective Action Plans and loss of funding. Many Test Refusal Movement activists were re-energized by these threats, rallying with statements about how the fight against the evils of the state and corporate interests had just begun. In New Jersey, test refusal activists were particularly angered because Governor Chris Christie, during his 2016 U. S. presidential campaign, claimed that he had abolished Common Core State Standards in New Jersey. In reality, however, the state had made no substantive changes to the standards but had merely renamed them (Supovitz et al., 2016). In addition, the Christie administration strategically waited until summer to have the New Jersey State Board of Education vote to make PARCC a graduation requirement and to announce that test scores would be weighted as 30 percent of some teachers' evaluation scores, an increase from 10 percent (Gewertz, 2016).

The American Civil Liberties Union and the Education Law Center filed a lawsuit against the New Jersey Department of Education (NJDOE) on behalf of students and their families. The lawsuit argued that the state had changed its graduation requirements for the classes of 2016 through 2019 without providing public notice and time to comment, as required by state law. The case was settled in May 2016. The agreement made clear that districts, rather than the state, would review students' portfolios and specified that any student—not just those who did not meet testing thresholds—could use a portfolio process as a graduation pathway (Gewertz, 2016). In 2016, test refusal rates in New Jersey remained high. The New Jersey Department of Education did not release data allowing comparison of 2016 rates to 2015 rates, but many districts reported similar rates of test refusals. In March 2017, a resolution (ACR215) stating that the use of PARCC to fulfill graduation testing requirements was inconsistent with legislative intent (Tat, 2017) was passed in the New Jersey State Assembly. Since then, PARCC critics have been pressuring the New Jersey State Senate to pass a concurrent resolution (SCR132). That resolution has not received a hearing in the Senate Education Committee, but in April 2017 State Senate President Stephen Sweeney and State Senator Teresa Ruiz, chair of the chamber's Education Committee, wrote to state education officials a letter indicating that the use of PARCC as a high school exit exam violated legislative intent and asked the State Board of Education to revise its rules governing graduation testing requirements. State law did not change; however, it does appear that test refusal rates in 2017 may have slightly declined in the grades in which PARCC is still on the record as a graduation requirement.

Reasons for Mobilization

According to observations at local and state meetings and in the press coverage of the Test Refusal Movement, many government officials and leaders of the testing industry seem to have concluded that teachers' unions were the major factor in promoting and organizing the Test Refusal Movement. Supovitz et al. (2016) point out that the teachers' union in New Jersey (New Jersey Education Association; NJEA) embarked on a multi-million dollar ad campaign against PARCC and established collaborative relationships with parent groups in local districts. Bennett (2016) argues that the implementation of teacher evaluation systems as part of the requirement of states seeking Race to the Top grants spurred teacher unions into action. His article focuses on New York, where teacher unions were quite vocal in encouraging test refusal and urging parents to subvert the new teacher evaluation system. Bennett argues that the combination of the backlash (led by the unions) against teacher evaluation and the backlash against more rigorous standards and tests were the main impetuses for the Test Refusal Movement. As evidence, Bennett points out that states that did not link teacher evaluation to student test scores or that postponed the implementation of new standards and tests did not have high refusal rates. However, by focusing primarily on the role of unions and on the difficulty of the standards and assessments, Bennett's analysis does not explain the wide variation among districts within a single state nor does it account for other motivations and factors that contributed to the movement. Within New Jersey, rates of refusal varied from negligible in some districts to more than 50 percent in some high schools. Data from the NJDOE showed that refusal rates were higher among Whites, in more affluent districts, among high school students, and among students who had not achieved proficient the previous year (Bennett, 2016; Supovitz et al., 2016). Anecdotally, it appeared that test refusal rates were high among special education students as well as among high-achieving high school students. However, rates varied dramatically across demographically similar districts, which showed that these differences alone did not explain this variation.

Research shows that opposition to high-stakes testing accountability systems came from very different constituencies including conservatives who wanted local control and opposed state interference in private life as well as liberals and Democrats who opposed capitalist influences on education. Opponents in the public education realm included education reformers and advocates who were concerned that too much time on testing was skewing the curriculum; teachers and their unions, who believed that these education policies were destroying public education; and ethnic solidarity and urban education reform activists who were fighting for local control of their schools and protesting inequality in society (Schaeffer, 2012; Williams, 2014; Meens and Howe, 2015). In a survey of 1,641 individuals who were recruited from test refusal social media groups, Pizmony-Levy and Saraisky (2016) found a range of political ideologies. In a network analysis of Twitter feed about Common Core, Supovitz et al. (2015) found that reasons for joining the Test Refusal Movement went far beyond the narrow issues cited by policymakers and the testing industry. Their study, as well as several others (e.g., Strauss, 2013; Wang, 2017) found that many concerns of movement activists involved instruction: a narrowing of the curriculum and too much teaching to the test; lost instructional time due to test preparation and test administration; concerns about the Common Core curriculum; and concerns about loss of freedom and creativity for students and teachers. Other issues had to do with the tests themselves: the costs of the tests (including hardware, infrastructure, and additional personnel); the validity and usefulness of the tests; and fear of data mining. Activists also worried about the negative effects on students: increased stress and anxiety; invasions of privacy; and the unfairness of the tests for poor, minority, and special education students. There were also many concerns about how test scores are used: Members of the movement opposed the use of high-stakes testing for student promotion, graduation, placement, and teacher evaluation. Finally, there was considerable anger among movement participants about federal and state overreach into education and about the privatization and corporatization of education.

Refusal Trends and Protest Interactions

Test refusal rates varied considerably across states, across districts, and across grade levels. This is where theories of social movement and political protest help us understand why mobilization was so strong in some places and not in others. Some states had virtually no refusals while 13 states did not meet the 95 percent participation requirement. New York had the most (20 percent) not participating, and New Jersey was second (at well over 10 percent). Supovitz et al. (2016) argue that, in New Jersey, the national context played into a series of state-level events and decisions, which contributed to an environment that produced a strong Test Refusal Movement. First, New Jersey adopted the Common Core State Standards and won a Race to the Top grant (which required linking test scores to teacher evaluation). Second, New Jersey adopted the PARCC test and rushed to move to a computerized test. Third, confusion about graduation requirements increased opposition to the PARCC test. Fourth, Governor Christie ran for U. S. President, publicly opposing Common Core on the national stage while maintaining state support for PARCC and increasing test scores to 30 percent of teacher evaluation scores. Finally, the New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) launched a multi-million dollar advertising campaign against PARCC; formed alliances with parental test refusal groups and anti-standardized test groups; organized and attended anti-PARCC events; and used the tactic of presenting themselves as parents (as opposed to teachers) at events and on social media (Supovitz et al., 2016). However, this state-level political context does not explain the huge variation of test refusal rates across districts in New Jersey. Supovitz et al. (2016) cite the state's confusing messages and uneven responses to districts as possible factors that explain the unevenness of test refusal across districts. However, differences in movement activity and organization within New Jersey have not been systematically examined.

Protest against high-stakes testing involved people and organizations from both the left and the right and from both inside and outside of the public education system coming together to try to change public policy. Media coverage and scholarly analysis of the Test Refusal Movement identified a number of prominent individuals and organizations that were concerned with public education, high-stakes testing, and the teaching profession: FairTest (The National Center for Fair and Open Testing); United Opt Out National, Inc.; Stop Common Core; Save Our Schools; the Badass Teachers (BATs) Association; the New York Allies for Public Education; and Diane Ravitch. In the context of statewide standardized testing, targets of protest included the state and federal governments, corporations (e.g., the testing industry and financers of school privatization), and the local school boards and administrators who were the enforcers of federal and state policies.

According to a survey of movement participants, the most common forms of activism by individuals were refusing the tests, posting information on social media, discussing with other parents, joining web-based distribution lists, signing petitions, contacting elected officials, and attending demonstrations or protests (Pizmony-Levy and Saraisky, 2016). Wang (2017) conducted an analysis of press coverage and documents in order to identify the movement actors in New York State and their opponents and to understand the networks among these organizations. The test refusal teacher organizations and the test refusal parent groups had the highest degree of centrality in the network of the Test Refusal Movement. They had strong coalition ties with each other as well as with parent/teacher associations, test refusal advocacy groups, and test refusal student groups. In contrast, the opponents or targets of the movement had highly fragmented networks, and no coalition ties were found among most of the actors. The opponents of test refusal mainly used negative tactics (e.g., threats, sanctions, punitive regulations) to try to fight the movement.

The Test Refusal Movement's Online Affinity Space

Pizmony-Levy and Saraisky (2016) found that movement participants cited social media as the main source of their mobilization. Supovitz et al. (2016) also acknowledged the role of social media in organizing and disseminating information. Activists whom they interviewed discussed the importance of social media in the success of the movement. Three groups were key players in the New Jersey Test Refusal Movement: Save Our Schools New Jersey, United Opt-Out New Jersey, and Cares about Schools. The Supovitz et al. (2016) analysis of the Twitter activity throughout 2015 of two Test Refusal groups (Save Our Schools New Jersey, New Jersey Opt-Out) and the teachers' union (NJEA) shows that these groups had much higher levels of activity than any pro-testing organizations. The Test Refusal groups and the NJEA showed higher levels of activity in the period leading up to and during PARCC testing, and the groups frequently retweeted each other's messages.

While Supovitz et al. (2016) examined Twitter activity in 2015, this study examines Facebook activity in 2016. The first author's own experiences (as a parent, school board president, and student pursuing a Ph.D. in education) suggested that while Twitter was certainly used by the movement, Facebook was the primary social media site used for communications and protest activity. This could be because of the average age of the activists: They were mostly parents of students in grades 3–11. Some evidence shows that this demographic is much more likely to have a Facebook account rather than a Twitter account: In 2014, 73 percent of 30–49 year olds actively used Facebook as opposed to only 25 percent using Twitter (Duggan et al., 2015).

This study began by using the platform CrowdTangle to track the Facebook activity of public groups. Of all public Facebook pages of test refusal organizations in the United States, Save Our Schools New Jersey had the highest growth in 2016; Montclair Cares About Schools had the third highest growth. In terms of number of interactions within the Facebook group, Save Our Schools New Jersey was third in the nation; Montclair Cares About Schools was eleventh. For average daily posts, Montclair Cares About Schools was first; Save Our Schools New Jersey was sixth. These numbers are impressive considering the number of test refusal groups across the country. However, looking at public Facebook groups only illuminates the tip of the iceberg. Many of the statewide and local movement Facebook pages were not public.

To gain a better understanding of what was happening, this study examines posts in the Refuse State Standardized Tests New Jersey Facebook group, which was not a public group so does not appear in the CrowdTangle data. At the time of data collection in spring 2016, the group had 10,056 members. This site was selected because, unlike many other large Facebook groups (e.g., Save our Schools New Jersey), it was centered primarily on refusing PARCC and, therefore, provides a more focused lens through which to view the movement. In addition, it was a statewide group, unlike local groups (such as Montclair Cares About Schools) or national groups (such as Moms Against Duncan), so it provides a lens through which to view the Test Refusal Movement across the state of New Jersey. It was a closed group, which made it more likely that activists would feel comfortable posting about specific tactics or plans without alerting their opponents.

Methodology

This study used a mixed methods content analysis approach to understand how social media was associated with the mobilization process, protest tactics, and ideologies of participants in the Test Refusal Movement. The study examined 1,463 posts in the 10,000 + member Refuse State Standardized Tests New Jersey Facebook group that members posted over a 71-day period leading up to and through the 2016 New Jersey PARCC testing window. This represents all the posts during that period but does not include the comments attached to the posts, as some conversations veered off topic and others were deleted by members when debates became heated. This Facebook group was formed by some parents as a support group for people in New Jersey who were considering refusing the PARCC tests for their children. It quickly grew to be a very large and active Facebook group and a center of the Test Refusal Movement online affinity space. Anyone who requested membership, including people from other states, was admitted to the group, and only rarely was a member removed by the administrators (This only seemed to happen if a person posted highly inappropriate or offensive content.). While the Facebook group was “closed,” (according to Facebook's own classification system), in reality it was open to everyone, and people who posted in it did so with the knowledge that more than 10,000 people would be reading their posts.

The first author drew on personal connections in the movement to obtain an additional interview sample of six movement activists and then recruited participants through e-mail requests. The protocol was approved by the IRB Committee of the Rutgers University Office of Research Regulatory affairs (approval number E17-310). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants of this study. During the interviews, the first author identified herself as a parent, a board of education member, as well as a researcher and made it clear that she had significant previous knowledge about PARCC and the Test Refusal Movement. This seemed to help participants be more forthcoming and increased the efficiency of the interviews because participants did not feel the need to explain every aspect of the background and context. Some of the interview questions asked participants to recall events and feelings from the past. The interviewees included two women from urban school districts, three women from suburban school districts, and one woman from a rural school district. One of the districts was affluent, and the others were either middle class or middle/working class. The sample was representative of the leadership of the movement. Most of the leaders of the movement were female, and activists from poor urban and rural districts were under-represented in leadership of the movement. Poorer districts had somewhat lower refusal rates. This may have something to do with the fact that several of the largest urban districts in New Jersey were under state control and faced punitive measures from the state (such as threats of loss of Title I funding, Corrective Action Plans, and other sanctions) if the districts did not participate in testing.

Four interview participants identified as Democrats and two as Independents. Three had participated in political protest about other issues over the years, beginning when they were in college. The other three stated that they had never engaged in any protest or political action until they became involved in the Test Refusal Movement. Two of these three, in fact, expressed disbelief that they had become so outspoken, stating that they had “never done anything like this in my life.” All but one talked extensively about Save Our Schools New Jersey, and three had volunteered as organizers for Save Our Schools New Jersey. There was a strong connection to the teaching profession among a significant number of the participants, although only one mentioned the NJEA or discussed teachers' roles in the Test Refusal Movement. One participant was a high school teacher, and one was a former elementary school teacher currently married to a teacher. Two worked closely with teachers, one as a part-time school social worker and one as a college instructor at a school of education. The other two respondents had no close family or friends who are teachers and did not interact regularly with teachers.

A combination of open coding (Strauss and Corbin, 1990) and deductive coding (Creswell, 2014; Patton, 2015) based on the literature on social movements and social media was used to identify three parent codes for the Facebook posts. Child codes emerged as the posts were categorized according to these three parent codes. The first parent code was Social Protest Tactics, which included child codes for traditional tactics (opting out of tests; organizing, attending, and speaking at local and state meetings; writing to local and state legislators; writing letters to the editor; starting or signing petitions) as well as social media-based forms of tactics (using social media to organize protest events and activities; sharing information on social media; posting or commenting on social media sites; creating and signing online petitions). The second parent code was Links Embedded in the Posts, which included child codes for links to other social media sites such as individual and organization Facebook pages, blogs, websites or Twitter accounts, television and radio coverage, videos, and photos. The third parent code was Theme of the Posts, which included child codes for themes of anti-technology, privacy, special education, English language learners (ELLs), local district reaction/intimidation, education reform, Common Core, harm to children, teachers, teacher evaluation, teachers' unions, state and federal politics, capitalism, testing industry, and privatization of education. The data from the Facebook posts was then triangulated by conducting six semi-structured interviews with leaders in the Test Refusal Movement (Creswell, 2014).

Analysis of Facebook Posts

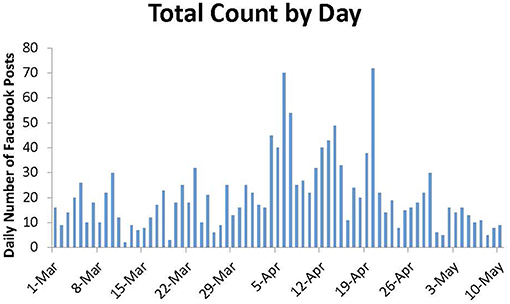

This analysis examines the content of each post but not the content of the comments associated with each post. In spring 2016, activity on the Refuse State Standardized Tests New Jersey Facebook site began to pick up as PARCC testing loomed on the horizon (see Figure 1). An increase in posts coincided with the start of the PARCC testing window. Testing dates varied by district and school, but most districts began their testing during the month of April, which showed the highest levels of activity in the Facebook group. The 2 days with the highest number of posts were April 5 (the date of a New Jersey State Board of Education meeting where many members of the movement protested) and April 20 (the date when the PARCC test platform crashed statewide).

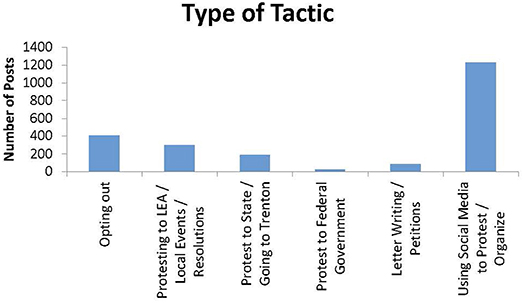

Most of the posts suggested some type of political protest tactics (see Figure 2). Some of these tactics (represented in the first five columns of Figure 2) were traditional forms of protest while others (represented in the sixth column of Figure 2) were new forms of Supersize Effects and Theory 2.0 Effects (Earl and Kimport, 2011) that are made possible by social media. The targets of the protest were identified: a local administration or Board of Education; the New Jersey state administration or elected officials; or the federal administration or elected officials. Posts were coded as follows: Refusing the Test (27.8 percent); Protesting to the Local District or Administration (20.6 percent); Protesting to the State (13.0 percent). Some examples of protest methods at the local and state levels included contacting Board of Education members, calling or writing to legislators, testifying in Trenton, displaying anti-PARCC signs in yards and on cars, and trying to attract media attention. Only two percent of posts were coded as Protesting to the Federal Government. Six percent of all posts referred to letter writing and petitions.

The sixth column in Figure 2 shows that 84 percent of all posts in the Facebook group were coded as Using Social Media to Engage in Protest, which represent Theory 2.0 Effects. These tactics included online petitions, posting on or liking other social media sites, using social media to organize protest activities, and sharing information in order to mobilize protest.

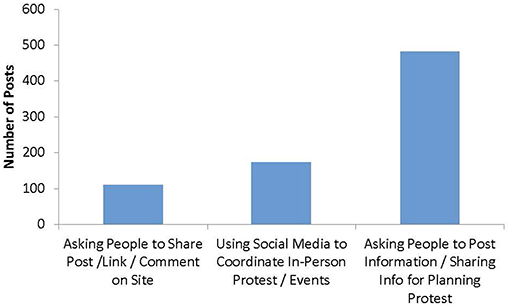

Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the Social Media tactics in column six of Figure 2. Column 1 of Figure 3 represents the 14.4 percent of Social Media tactics that involved asking others to share information, take action, or share links on social media (e.g., instigating Twitter campaigns, sharing links on personal social media sites, leaving comments on websites, or Facebook pages). Column 2 shows that 22.5 percent of posts involved using social media to organize traditional forms of protest (e.g., drumming up attendance at events and meetings, planning in-person protest activities, attracting media coverage). Column 3 represents the 62.9 percent of Social Media tactics that involved asking others to engage in the sharing of information or strategies on social media; to distribute information to others; to help collect facts to use when writing letters or speeches; and to gather information about federal, state, or local targets of the protests.

The data illustrate the two types of effects of social media identified by Earl and Kimport (2011). The speed of growth of the Test Refusal Movement was a perfect example of Supersize Effects. The Internet reduced the cost (both time and money) of protest, increased the speed in which mobilization occurred (transmission of information and communication), and changed the scale on which mobilization took place. Many of the tactics displayed in the Refuse State Standardized Tests New Jersey Facebook group were examples of Theory 2.0 Effects. There was a new digital repertoire of e-tactics, organization that occurred without physical co-presence, large-scale e-tactics produced by individuals or small groups of people, and broad targets and goals.

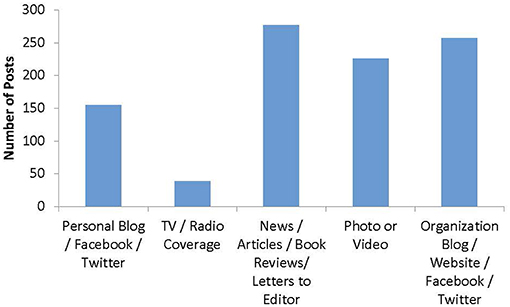

Next, the types of links embedded in those posts were identified: Many posts contained links to websites, videos, pictures, blogs, Twitter accounts, Facebook pages, and other social media (see Figure 4). The fact that 65.2 percent of all the posts in the Facebook group contained links provides strong evidence for the importance of networks in the modern political protest landscape. Of these links, 29 percent were to links of written news including articles, book reviews, and letters to the editor. Often the posts encouraged people to “like” or “dislike” the item in the link, to leave comments about these news items, or to share the items on their own social media sites. Posts containing videos or photos occurred 23.6 percent of the time and, again, often encouraged that these posts be shared. Twenty-seven percent of the links led to an organization's website, Facebook page, or Twitter feed, and 16.2 percent of the links were led to an individual's blog, Facebook page, or Twitter feed. Again, often the intent of the post was to encourage people to engage with these sites by leaving comments or by “liking” or “disliking” the information. Finally, four percent of the links led to television or radio segments. This data illustrates the porous boundaries of the Internet and other social media sites. People engage on multiple sites, and sites are networked and connected in many ways. The Test Refusal Movement clearly created an online affinity space that involved many interconnected sites, forms of social media, and discussion platforms (Gee, 2004; Lammers et al., 2012).

Finally, the posts were categorized according to the Theme of Facebook Post. Given that the name of the Facebook group was Refusing State Standardized Tests New Jersey, it was no surprise that 83.8 percent of the posts were coded as Refusing PARCC: These posts included advice about how to refuse; discussed local district and state reactions to refusals; promoted strategies about how to encourage others to refuse PARCC; and presented concerns about the repercussions of refusing the test.

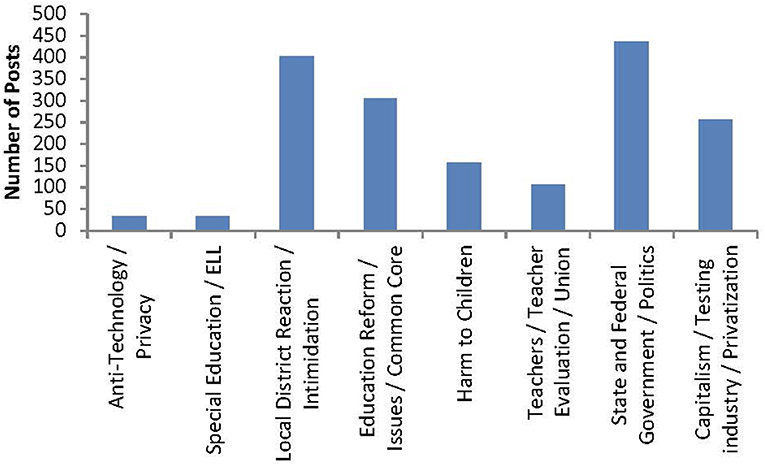

Many other themes emerged from the data (see Figure 5). Thirty percent of the posts were coded as State and Federal Politics. These posts discussed policies and government responses to the Test Refusal movement. Local District and Board of Education Politics (27.5 percent) included discussion of local policies and responses to the Test Refusal Movement. Education Reform posts (20.9 percent) included a range of political and ideological discussions and debates while Corporatization and Privatization of Education posts (17.6 percent) were critical of these trends. Harm to Children posts (10.8 percent) and Harm to Special Education and ELL Students posts (2 percent) were also codes that emerged.

Only 7.2 percent of the posts were coded as Teachers and Unions. This was surprising because much of the media coverage and previous analyses of the Test Refusal Movement focused so strongly on teacher evaluation and pointed to teachers' unions as a primary reason for the emergence and strength of the movement. Only two percent of the posts were coded as Data Mining and Privacy, which seems to debunk the theory that a significant portion of the movement was made up by people who were afraid of the negative effects of technology such as loss of privacy or too much screen time.

Overall, the data show that there are many reasons why people mobilized against high- stakes standardized testing. The data also show that there were many targets of the protest, including the federal and state governments and corporations. While local school district administrations and boards of education were also often a target of protest, many of the posts demonstrated that members of the movement understood that local districts were merely the enforcers of state and federal policies. The posts about education reform prove that members of the movement were aware of the complex nature of the public education system. Many members of the movement were well educated about the economic, political, and cultural contexts in which the battle over the purpose and nature of public education was taking place. The relatively low proportion of posts focused on teachers and unions challenges the assumption that one of the primary motivators was the use of high-stakes testing for teacher evaluation (Bennett, 2016).

Interviews With Members of the Test Refusal Movement

Six semi-structured interviews (see Appendix for interview protocol) provided a more nuanced understanding of the motivations and ideologies of members of the movement. First, the interviews were coded for Social Protest Tactics. All of the respondents had participated extensively in traditional protest tactics. All of them had spoken and written to their local school district administration and to the New Jersey Department of Education to voice their protest against PARCC. All had attended events about PARCC, and five of the six had spoken at these events. Three had helped to plan anti-PARCC events. Five of the six had contacted their legislators, and two had initiated in-person meetings with their legislators. Two had spoken about test refusal on the radio or on television, and three had written letters to the editor or opinion pieces in newspapers. Three of the respondents had testified in Trenton, the state capitol of New Jersey.

The respondents engaged in a number of social media tactics. All of the respondents said that they had used social media to conduct research on high-stakes testing and education issues, and all had used social media to share this information. All had joined at least one test refusal Facebook group, while four participants had started their own local Facebook group. Three respondents had posted comments on their opponents' social media sites. Four had participated in online petitions and surveys about test refusal. Only one had posted videos of her own protest activities, however, many had re-posted others' videos and photos.

The respondents stressed the importance of social media in the mobilization process. Several said that the Test Refusal Movement was one of the only reasons they used social media. As one respondent said:

I have a very tumultuous relationship with social media … I only got active on it when I got involved in this [the Test Refusal Movement] … I don't like it for personal use. I created an account that I only use for my activism where I do not share any personal stuff … but Facebook is an excellent way to connect with others and communicate.

Another stated, “The only social media I use is Facebook. I actually just got my first Smartphone. But I have been managing the local Facebook group for PARCC refusal for a couple years, using my computer.” Additionally, one participant said, “I was so upset that I wound up speaking at a local Board meeting, and that's when I started a parent group here, on Facebook.” Another stated the following:

I started following Save Our Schools NJ on Facebook…many of us have started local groups to educate people about Save Our Schools. Ours has about 3,000 people…it was started to connect with the community so we could have conversations about education policy.

All of the interview subjects reported that their membership in online communities was a critical factor in sustaining their involvement in the Test Refusal Movement as well as expanding their interest into the larger arena of education reform. An interesting note is that all six respondents used Facebook to communicate and strategize while only one used Twitter, which supports the argument that Facebook was the primary mode of communication for the movement. As one respondent noted, “I am not comfortable with Twitter, I don't know what happens when you post. But Facebook was just like a very user friendly thing for me,” another claimed, “Without Facebook, PARCC refusal would not even be something we are organized around.” All six activists stressed the information sharing and networking that occurred in Facebook groups. The following quotes are examples:

• “I got to know a lot of people in different districts on Facebook.”

• “I have a pretty big network on Facebook, and I shared all this stuff with them.”

• “We put signs on our lawn … and I posted pictures of the signs on Facebook.”

• “Across social media, I would talk to friends and they would be like, yeah, the same thing is happening here.”

Finally, one respondent shared the following:

What was very useful on social media was people would post direct links to the Department of Education's website so you could see the directive that was going out to districts … and then we would know why all of a sudden people in districts across the state all got letters from their superintendents about PARCC that were pretty much the same. Lots of this kind of information sharing went on.

The interview participants discussed their reasons for refusing PARCC and for getting involved in the movement. The interviews, like the Facebook data, confirmed that there were many reasons that led to political mobilization. All six respondents felt strongly that high-stakes testing harms children. One said, “It filled my child with anxiety…it was horrible…a child shouldn't be put through that…it's an evil thing.” Another claimed, “We would hear about kids that were melting down completely…some people would say my kid today just about had a breakdown.” Yet another asked, “My kid is under enough pressure, why would I have him take a test just for the sake of it?” Three specifically discussed how PARCC disproportionately harmed special education and ELL students. As one expressed, “We spent years trying to build his self-confidence, and I felt like it would be such a bad experience for him that it just wasn't worth that sacrifice.”

All but one of the activists also spoke about harm through the lens of educational inequality, making the argument that high-stakes testing increases inequality because it disproportionally harms poor districts. One said bluntly:

[While] all kids are smart…poor kids no longer buy into the bullshit…what is there in it for them to do well on this test? If they don't do well on this test it is like giving the middle finger to the U.S. government or to the state.

Another respondent clearly articulated the idea that high-stakes testing:

is creating a two-tier system of education—one system, the public schools, where children are being robotically taught to pass tests and another system, private schools, with more project-based learning, creative autonomy, learning leadership skills. This sets up a system where you have a working class and a power class.

The majority of the respondents repeatedly mentioned the fact that the PARCC test had not been validated and did not provide useful information to teachers or parents. One respondent stated, “I researched the test, I know what a good test is, and this test is not appropriate…I was horrified thinking about my kids taking this test.” All six respondents opposed the use of PARCC as a graduation requirement. Several made arguments along the lines that, “the PARCC test has not been validated so it is not a legitimate way to decide whether or not kids can graduate.” All of the respondents felt that there was too much testing and that PARCC led to increased test preparation and the loss of creativity in the curriculum. One stated, “It creates such a narrow focus in public education, and I just think it is incredibly dangerous.”

Only three of the participants mentioned the use of PARCC for teacher evaluation, making offhand comments that were not the focus of their interviews. One said, “The notion that my child's test score is going to somehow impact this teacher and their tracking, to me, just seems ridiculous.” Another said, “I don't think it should be linked to teacher evaluations,” and a third said, “Teachers feel like they have to test prep because some of their evaluation is going to be based on the scores.” All six respondents said they had gotten involved in the movement in order to protest government over-reach in the public education system. Three said they opposed the fact that corporations are making a profit from high-stakes testing. One respondent said, “Make no mistake about what PARCC is and whose pockets it lines up,” and another pointed out that, “We have written off tax earnings from [Pearson] by giving them basically rent-free accommodations in New Jersey.” Only one person mentioned concerns about student privacy and data mining; Others complained about the financial cost of PARCC for districts, saying, “It's a lot of money to spend to find out what we already know, that there are rich districts that are doing better and poor districts that are doing terribly.”

Perhaps the most interesting theme that emerged from all six interviews was that the activists' feelings and worldviews had changed dramatically over the several years that they were involved in the Test Refusal Movement. Many of them said that at the beginning, when they first started researching PARCC and thinking about refusing, they felt fear and frustration. Illustrative quotes include: “Parents and teachers felt oppressed by PARCC and felt anxious,” and, “Sometimes it felt crazy or radical to not do what you are supposed to do.” One respondent said that “PARCC was the first time that I felt compelled to talk to our Board of Ed…I literally cried, it was so stressful and intimidating.” Despite these feelings, they felt determined to take a stand; none mentioned that they had ever second-guessed their decision to refuse the test. This determination shows in statements such as: “I just knew from the beginning that PARCC and these policies are not good for kids and that I was going to not only refuse but also actively work against those policies.”

As time went on, movement activists reported that their emotions became stronger, and feelings of fear and frustration were replaced by anger, empowerment, and pride. As one said, “The state is doing everything it can to push the test…and talk parents into it and try to scare them…but you can't scare me because I did my research.” Another said:

What brought me to the point I'm at today is honestly [Governor] Chris Christie…I have never been more horrified and disgusted by any person…it is obvious the state was giving districts their marching orders…you better squash this down.

Members of the Test Refusal Movement explained their activism with statements such as, “My kids' education is suffering because of this [PARCC], and if I don't push back, nobody is going to do it for me,” and, “I have always taught my kids that if you feel strongly about something you should do something about it,” and, “People have come to realize over time that it is not a radical thing, it is for a specific purpose…to protect the schools and our schools' ability to make decisions about what is right for them.” Several used the term, empowerment, with one saying that “we posted videos of ourselves testifying because we thought it would be empowering to other parents.” They spoke frequently about how their participation in the online affinity space increased their sense of power, community, and political engagement.

All of the activists described a transformation in their views on the public education system and their reasons for participating in the movement. They talked about a shift from concerns about their own children to larger concerns about social justice. As one conveyed:

In the beginning it was about protecting my kid from feeling like a failure and feeling overwhelmed…now it has nothing to do with her but about getting all kids the education they deserve…and fighting policies that are not fair.

Others said, “Now I'm less worried about my own kids than about the kids in Newark (an urban, high minority, high poverty district)…it [PARCC] is going to have huge implications for our poorest districts.” They felt that it was their duty to inform others about these injustices:

• “There was some sort of shenanigans that was being pulled over on parents…that we were expected to simply be disinterested and unaware…we needed to let people know about this.”

• “I tried to reach the Asian community, which I am part of, to tell them you don't need to sit back idly and have your children's education compromised.”

• “My personal philosophy has been, I want to reach the people who are not informed, or the people who are on the fence.”

The theme of social justice came up in many of the interviews. Some illustrative quotes include:

• “I am a social worker, and my code of ethics tells me I have to speak out against injustice.”

• “Being a democratic citizen means that you stand up for others and participate.”

• “I think my activism is truly fueled by my seeing the injustice and the inequity in our public schools.”

One respondent stated proudly, “Now I am like a social justice advocate!” They frequently credited their transformation to the personal relationships that they developed in the movement's affinity space. One concluded that “the best part that came out of this is that I got to learn more about education and got to know people in urban districts and it turned me into an activist!”

Conclusion

This mixed methods study synthesizes and expands on existing theories and presents a nuanced perspective on how social media tactics supplement and intensify traditional protest tactics. By using two sources of data to examine the experiences and ideologies of members of the Test Refusal Movement, this research promotes a deeper understanding of the reasons for the unexpected emergence of the fight against high-stakes testing. This analysis of the Test Refusal Movement identifies many of the complex components of political protest in our post-industrial neoliberal society. Protest against high-stakes testing was a situation in which people and organizations from various political backgrounds and from both inside and outside of the public education system came together around a common issue and tried to change public policy (Lugg and Robinson, 2009; Hutter and Kriesi, 2013; Whittier, 2014; Friesen, 2015; Sagi, 2015; Staggenborg, 2015). The protest was conducted through institutional and non-institutional tactics and political streams (McAdam, 1982; Cohen, 1985; Goodwin et al., 2001; McAdam and Tarrow, 2013; Staggenborg, 2013; Fisher, 2015). Targets of the protest included the government (federal, state and local), corporations (the testing industry and financers of school privatization), and local school boards and administrators (the enforcers of federal and state policies) (Armstrong and Bernstein, 2008; McAdam and Tarrow, 2013; Staggenborg, 2013).

The protest against high-stakes testing presents a unique opportunity to apply a synthesis of the research and theories on social movements and political protest as well as to examine the role that social media plays in this process. The Test Refusal Movement organized its members and engaged in protest in physical space (through personal relationships, local events and organizations, and traditional forms of protest) as well as virtual space (through social media, electronic sharing of information, online petitions and campaigns, and other virtual tactics) (Appadurai, 1996; Earl and Kimport, 2011; Shirky, 2011; Amenta, 2012; Castells, 2012; Gerbaudo, 2012; von Stekelenburg and Roggeband, 2013; Schradie, 2014; Wolfson, 2014). The movement created an affinity space (Gee, 2004; Lammers et al., 2012) that involved many interconnected sites, forms of social media, and discussion platforms. Social media contributed to a type of political mobilization that had not been seen before in the public education system in the United States. Supersize Effects were evident: the movement mobilized so quickly and at such as large scale that Federal, state, and local officials as well as the testing industry were completely surprised and unprepared as to how to respond to the Refusal Movement. Theory 2.0 Effects were also present: in contrast to what has been characteristic of earlier social movements, the Test Refusal Movement engaged in a repertoire of e-tactics (organization that occurs without physical co-presence), using social media to recruit members, engage in digital protest, disseminate information and communicate and organize traditional in-person types of protest (Earl and Kimport, 2011).

An important finding is that mobilization did not occur evenly across districts. Evidence shows that refusal rates were highest in affluent districts and lowest in poor districts (Supovitz et al., 2016). The data from this study shows that political activism also varied across districts. Part of this could be explained by the fact that poorer parents have less time and energy to spend on political activism or online on social media, and may have fewer social connections outside of their community. But it is clear that the state and elites can more easily suppress the protest of less powerful groups (Castells, 2012; McChesney, 2013). This contributes to the explanation for why the Test Refusal Movement was more successful in affluent towns. Evidence suggests that because the stakes were higher in poor school districts, parents, and teachers were less likely to engage in social protest. These repressive tactics included threats of loss of funding, threats to teachers and administrators who supported the Test Refusal Movement, threats of school closings, and threats to parents that their children could be at risk for grade retention, remedial classes, or other punitive measures if they refused state-mandated standardized tests. Just the fact that the state threatened loss of Title I funding to districts that did not meet the 95% testing participation requirement had a much larger impact on poor districts.

Although many of the Facebook comments suggest that the participants on social media tended to come from more affluent districts, the study did not collect direct evidence about the background of those who posted. Future research that collected and analyzed demographic characteristics of protest participants could illuminate the interrelationships among participatory actions, social class, and engagement with particular issues.

Rumors of teachers being sanctioned for speaking out against the teacher evaluation system or against standardized testing appeared to be less common in affluent districts. In fact, several superintendents and teachers in affluent New Jersey districts were vocal supporters of the Test Refusal Movement, and some suburban districts made refusing the PARCC simple by sharing a link to a refusal form on their district websites. Meanwhile in other districts, parents who attempted to have their students refuse PARCC were called in for unpleasant meetings with administrators, threatened with consequences, and in some cases reported that their children were being “bullied” into taking the test.

The mobilization of activists involved a complicated process by which individuals experienced emotional and ideological engagement around many issues including concerns about the well-being of their own children, beliefs about the purpose of public education, and issues of social justice. Participation in the affinity space was not just a place for the likeminded to organize but a space that was actually transformative to the participants. It is clear that social media has changed the process by which consciousness raising and political mobilization occur.

This study's findings suggest that while social media tactics were critical to mobilization and organization, traditional forms of political action were not simply replaced by the new forms but were also changed by them. It is important to note that while the respondents frequently mentioned the role of social media, it was often in the context of using social media to communicate and strategize about traditional forms of protest. The movement used social media to recruit new movement members, to organize in-person events, to share information about how to engage in traditional forms of protest, and to garner public attention for the movement. While the findings in this study are based on interviews with only six participants, their accounts support the evidence from the online affinity space in the Refuse State Standardized Tests New Jersey Facebook group.

Ethics Statement

The protocol was approved by the IRB Committee of the Rutgers University Office of Research Regulatory affairs (approval number E17-310). During the interviews, the first author identified herself as a parent, a Board of Education member, as well as a researcher and made it clear that she had significant previous knowledge about PARCC and the Test Refusal Movement.

Author Contributions

RM and DG contributed to the conception and design of the study. RM organized the data collection and analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. DG contributed to revisions of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2019.00055/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Despite the fact that most media coverage and research refer to the Opt-Out Movement, we choose to refer to the movement as the Test Refusal Movement. The term, Refuse, has been adopted by individuals and organizations in the movement in order to make the distinction between Opting Out of high-stakes testing (which many state laws do not allow) and Refusing the tests (which is the legal right of parents).

References

Amenta, E. (2012). The Potential Political Consequences of Occupy Wall Street. Available online at: https://mobilizingideas.wordpress.com/2012/01/02/the-potential-political-consequences-of-occupy-wall-street/ (accessed October 17, 2015).

Armstrong, E. A., and Bernstein, M. (2008). Culture, politics, and institutions: a multi-institutional politics approach to social movements. Sociol. Theory 26, 74–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00319.x

Baumer, D. C., and Van Horn, C. E. (2014). Politics and Public Policy: Strategic Actors and Policy Domains, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Bennett, R. E. (2016). Opt Out: An Examination of Issues (ETS Research Report ETS RR−16-13). Prinecton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Buckshot, S. M. (2015, April 14). NYS Opt-out Movement Grows; Tens of Thousands—Maybe More—Expected to Skip Tests. Syracuse News. Available online at: https://www.syracuse.com/news/index.ssf/2015/04/opt-out_movement_grows_across_state_thousands_of_students_expected_to_refuse_tes.html (accessed January 15, 2016).

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Cohen, J. L. (1985). Strategy or identity: new theoretical paradigms and contemporary social movements. Social Res. 52, 663–716.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Diani, M. (2013). “Organizational fields and social movement dynamics,” in The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, eds J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Raggeband, and B. Klandermans. (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 145–168.

Duggan, M., Ellison, N. B., Lampe, C., Lenhart, A., and Madden, M. (2015). Demographics of Key Social Networking Platforms. Available online at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/01/09/demographics-of-key-social-networking-platforms-2/ (accessed November 3, 2017).

Earl, J., and Kimport, K. (2011). Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Fenger, M., and Klok, P.-J. (2001). Interdependency, beliefs, and coalition behavior: a contribution to the advocacy coalition framework. Policy Stud. 34, 157–170. doi: 10.1023/A:1010330511419.

Fisher, D. R. (2015). The Problem With Research on Activism. Available online at: https://mobilizingideas.wordpress.com/2015/09/02/the-problem-with-research-on-activism/ (accessed January 26, 2016).

Friesen, M. (2015). Birds of a Feather Flock Together…But Not How You Might Think. Available online at: https://mobilizingideas.wordpress.com/2015/10/05/birds-of-a-feather-flock-together-but-not-how-you-might-think/ (accessed January 26, 2016).

Gee, J. P. (2004). Situated Language and Learning: A Critique of Traditional Schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism. London: Pluto Press.

Gewertz, C. (2016). New Jersey Settles Lawsuit Over Graduation Requirements. Education Week. Available online at: http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/high_school_and_beyond/2016/05/New_Jersey_settles_lawsuit_graduation_rules.html (accessed May 9, 2016).

Gitlin, T. (1998). “Public Sphere or Public Sphericules?” in Media, Ritual and Identity, eds T. Liebes, and J. Curran (London: Routledge), 168–175.

Goodwin, J., Jasper, J. M., and Polletta, F. (2001). “Introduction: why emotions matter,” in Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, eds J. Goodwin, J. M. Jasper, and F. Polletta (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 1–24.

Guisbond, L., Neill, M., and Schaeffer, B. (2015). Testing Reform Victories 2015: Growing Grassroots Movement Rolls Back Testing Overkill (A Report by The National Center for Fair & Open Testing). Boston: FairTest. Available online at: http://www.fairtest.org/sites/default/files/2015-Resistance-Wins-Report-Final.pdf (accessed December 5, 2015).

Hutter, S., and Kriesi, H. (2013). “Movements of the left, movements of the right reconsidered,” in The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, eds J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Raggeband, and B. Klandermans (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 281–298.

Klein, R. (2016, April 9). Are White Parents the Only Ones Who Hate Standardized Testing? The Huffington Post. Available online at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/standardized-test-opt-out_us_57043d53e4b0a506064d8127 (accessed February 10, 2017).

Lammers, J. C., Curwood, J. S., and Magnifico, A. M. (2012). Toward an affinity space methodology: considerations for literacy research. English Teach. 11, 44–58. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ973940 (accessed November 20, 2015).

Lugg, C. A. (2001). The christian right: a cultivated collection of interest groups. Edu. Policy 15, 41–57. doi: 10.1177/0895904801015001003

Lugg, C. A., and Robinson, M. N. (2009). Religion, advocacy coalitions, and the politics of U.S. Public Schooling. Edu. Policy 23, 242–266. doi: 10.1177/0895904808328527.

McAdam, D. (1982). Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930–1970. 2nd Edn. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

McAdam, D., and Tarrow, S. (2013). “Social movements and elections: toward a broader understanding of the political context of contention,” in The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, eds J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Raggeband, and B. Klandermans. (Minneapolis, MA: University of Minnesota Press, 325–346.

McChesney, R. W. (2013). Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy. New York, NY: The New Press.

Meens, D. E., and Howe, K. R. (2015). NCLB and its wake: bad news for democracy. Teachers College Rec. 117:060302. Available online at: http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=17878 (accessed March 3, 2016).

Offe, C. (1985). New social movements: challenging the boundaries of institutional poltics. Social Res. 52, 817–868.

Passy, F., and Monsch, G.-A. (2014). Do social networks really matter in contentious politics? Social Movement Stud. 13, 22–47. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2013.863146

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Pizmony-Levy, O., and Saraisky, N. G. (2016). Who Opts Out and Why? Results From a National Survey on Opting Out of Standardized Tests (Research Report). New York, NY: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Polletta, F. (2011). Maybe you're better off not holding hands and singing We Shall Overcome. Available online at: https://mobilizingideas.wordpress.com/category/essay-dialogues/digital-media-in-activism/ (accessed January 26, 2016).

Rootes, C. (2013). “Discussion: mobilization and the changing and persistent dynamics of political participation,” in The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, eds J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Raggeband, and B. Klandermans (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 299–310.

Sagi, R. (2015). Diverse Coalitions: Reconciling Disparate Ideologies and Incongruent Collective Identities. Available online at: https://mobilizingideas.wordpress.com/2015/11/03/diverse-coalitions-reconciling-disparate-ideologies-and-incongruent-collective-identities/.

Schaeffer, B. (2012). Resistance to High-stakes Testing Spreads. Available online at: http://www.fairtest.org/resistance-high-stakes-testing-spreads (accessed November 29, 2015).

Schradie, J. (2014). Bringing the organization back in: social media and social movements. Berkeley J. Sociol. Available online at: http://berkeleyjournal.org/2014/11/bringing-the-organization-back-in-social-media-and-social-movements/ (accessed March 7, 2016).

Shirky, C. (2011). The political power of social media: technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs 90, 28–41. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25800379 (accessed March 10, 2016).

Soule, S. A. (2013). “Bringing organizational studies back into social movement scholarship,” in The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, eds J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Raggeband, and B. Klandermans (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 107–123.

Staggenborg, S. (2013). “Organization and community in social movements,” in The Future of Social Movement Research: Dynamics, Mechanisms, and Processes, eds J. Van Stekelenburg, C. Raggeband, and B. Klandermans (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 125–144.

Staggenborg, S. (2015). Building Coalitions and Movements. Available online at: https://mobilizingideas.wordpress.com/2015/11/03/building-coalitions-and-movements/ (accessed January 26, 2016).

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Strauss, V. (2012). High-Stakes Testing Protests Spreading. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/post/high-stakes-testing-protests-spreading/2012/05/30/gJQA6OQX0U__blog.html?noredirect=on&utm__term=.92d792916bb3 (accessed May 30, 2012).

Strauss, V. (2013). Arne Duncan: ‘White suburban moms' upset that Common Core shows their kids aren't ‘brilliant.' The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2013/11/16/arne-duncan-white-surburban-moms-upset-that-common-core-shows-their-kids-arent-brilliant/?utm__term=.de7a36657795 (accessed November 16, 2013).

Strauss, V. (2015a). As Testing Opt-out Movement Grows, So Does Pushback From Schools. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/03/27/as-testing-opt-out-movement-grows-so-does-pushback-from-schools/?utm__term=.fd84e1ccbd80 (accessed March 27, 2015).

Strauss, V. (2015b). Are Government Officials Trying to Intimidate Parents Who Resist Testing. The Washington Post. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/05/02/are-government-officials-trying-to-intimidate-parents-who-resist-testing/?utm_term = .96c97f2b42de (accessed May 2, 2015).