- 1School of Psychology, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Education, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

- 3Department of Education, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

The current study sought to investigate the extent to which early childhood educators’ confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy for supporting early self-regulation predicted educator behavior and children’s self-regulation outcomes. Data from a diverse sample of 165 early childhood educators participating in a cluster Randomized Control Trial evaluation of a self-regulation intervention were utilized to evaluate the construct validity, reliability and predictive properties of the Self-Regulation Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-Efficacy scale. Evaluation via traditional (EFA, Cronbach’s Alpha) and modern approaches (Rasch Analysis) yielded a valid and reliable 25-item scale, comprising three distinct yet related subscales (i.e., confidence in knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy). For educators assigned to the intervention group, self-efficacy significantly predicted educators perceived competency to implement the self-regulation intervention as well as their perceptions around the effectiveness of the intervention to enhance children’s self-regulation. For educators assigned to the control group (i.e., practice as usual), educator attitudes longitudinally predicted children’s end-of-year status and change in self-regulation (over 6 months later). Findings from this study suggest the importance of pre-school educators’ beliefs for fostering early self-regulation and highlight a need to further explore the impact of these beliefs with regard to educator engagement with intervention.

Introduction

Compelling evidence for the pivotal role of self-regulation for lifelong outcomes, and its susceptibility to change over and above age-related development, have propelled it to the forefront of contemporary efforts to enhance children’s developmental trajectories (Moffitt et al., 2011; Wass et al., 2012). In terms of enacting self-regulatory change in the early years, the ubiquity of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and critical role of educator practice for shaping children’s outcomes (Melhuish et al., 2015) have seen a proliferation of ECEC-based self-regulation interventions (e.g., Bodrova and Leong, 2007). While such approaches often utilize educators as mediators for enacting child self-regulatory change, no ECEC-based self-regulation intervention studies to date have sought to consider or measure intervention effects on educator characteristics which underpin practice (e.g., educator beliefs); nor have they considered how differing levels of such characteristics (e.g., more positive attitudes) may influence educator engagement in training or effective implementation of intervention endorsed practice. This is likely exacerbated by lack of valid and reliable tools for measuring such characteristics as they relate to supporting early self-regulation. The current study thus sought to construct and evaluate an educator-report questionnaire of confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy for supporting early self-regulation development. Predictive validity analyses were also undertaken to investigate whether and to what extent educator scores on this scale predicted educator’s engagement with and perception of a self-regulation intervention and the self-regulation abilities of children in their care.

Although it is diversely conceptualized in the literature (Burman et al., 2015), self-regulation can be generally defined as encompassing the ability to direct and control cognitive, behavioral, social and emotional processes facilitating goal attainment or desirable outcomes. More specifically, and adhering to strength-based models of self-regulation (to which the authors subscribe; Baumeister and Heatherton, 1996), successful self-regulation requires children to: 1) select a goal; 2) maintain sufficient motivation towards achieving said goal; and, 3) have the capacity to overcome barriers towards achieving goals (whereby “capacity” is underpinned by executive functions; i.e., working memory, cognitive flexibility and inhibition; Hofmann et al., 2012). In the context ECEC-based settings a well-regulated child will be able to, among other things, persist with challenging tasks, sustain attention and resist distraction, engage in prosocial behavior (e.g., share toys, wait their turn) and appropriately manage emotional responses. While these skills develop rapidly across the first 5 years of life, there remains considerable heterogeneity in the development of early self-regulation (Montroy et al., 2016b), with implications for both short and long-term development. Individual differences in early self-regulation are linked with academic performance and social-emotional wellbeing in childhood (Howard and Williams, 2018), as well as health, financial and social outcomes in adulthood (Moffitt et al., 2011). Rather than fixed trajectories, however, longitudinal data supports self-regulation as susceptible to change, with early interventions offering the greatest potential for pronounced and more stable improvements (Wass et al., 2012).

Efforts to mitigate early disparities in self-regulation acknowledge socializing agents such as parents (Sanders and Mazzucchelli, 2013) and early childhood educators (Diamond and Lee, 2011) as key catalysts for child-level change. Given the ubiquity of early childhood education and care (ECEC) experiences and robust evidence of the positive impacts of educator practice (Mashburn et al., 2008), recent efforts have increasingly focused on early childhood educators as mediators for self-regulatory change (Diamond et al., 2019). Much of this research has sought to enhance educators’ ability to support early self-regulation via training that targets factors which influence practice (e.g., knowledge, beliefs and skills; Fukkink and Lont, 2007; Zaslow et al., 2010).

While evaluations of ECEC-based interventions routinely investigate changes in reported or observed educator practice, and the extent to which these indicate program fidelity and influence child-level outcomes (e.g., Barnett et al., 2008); few studies have sought to investigate how intervention efficacy may vary by educator beliefs, through their impact on perceptions of and engagement with the program. Indeed, few tools exist to capture these characteristics, and none specifically in relation to children’s self-regulation. This domain-specificity is important given suggestion that educator beliefs may vary across domains (i.e., self-efficacy for numeracy instruction can differ from self-efficacy for literacy instruction; Gerde et al., 2018). Given the prevalence of ECEC-based self-regulation interventions, investigation of educator beliefs that can influence program engagement, practice and child outcomes is of importance.

Theoretically, educator beliefs have been positioned as central to educator behavior including instructional practice and engagement with training. Applying the principles of Social Learning Theory to receptiveness to “innovations”—which includes, but is not limited to, openness to and implementation of a novel approach—Bandura (2006) suggested the interplay between behavioral, cognitive and environmental factors as contributing to innovation adoption. For instance, Bandura (2001) emphasized the importance of cognitive factors for influencing change in behavior (e.g., individuals are less likely to enact something if they think it is unimportant or ineffective) and influencing interpretations of the environment (e.g., individuals are less likely to enact something if they perceive the environment as lacking the necessary supports). In his research, Bandura (2001) highlights beliefs, including educator attitudes and self-efficacy, as important variables influencing educator behavior. Within other models of educator behavior and child outcomes (e.g., multidimensional models of professional competence; Baumert and Kunter, 2013; Blömeke, 2017; models of effective professional development; Fukkink and Lont, 2007; Zaslow et al., 2010) the integration of both professional knowledge and professional beliefs for enhancing educator practice and outcomes is likewise considered essential. In this context, knowledge and beliefs function in a distinct but complementary manner for influencing behavior.

In terms of beliefs impacting educator behavior, empirical evidence suggests educator perceptions of their own knowledge as influential to both practice and engagement with professional learning. Variability in perceptions of one’s own knowledge has been found to be associated with information-search behaviors as well as assimilation of new information (Park et al., 1988; Radecki and Jaccard, 1995). That is, greater confidence in one’s knowledge—regardless of the accuracy of these perceptions—is associated with lesser motivation to seek out or acquire new information (Radecki and Jaccard, 1995). This is particularly problematic given the low correspondence between genuine and perceived knowledge (Sangster et al., 2013; Hammond, 2015). Further, research suggests those with low confidence in their knowledge, or high recognition of gaps in their knowledge, demonstrate: 1) a better global comprehension of new information; 2) a greater likelihood to downgrade the importance given to old pre-learned information; and, 3) a greater tendency to resolve conflicts between old and new information by giving preference to new information (Park et al., 1988). In education, confidence in knowledge is also linked with instructional practice, yet the exact nature of the relationship between knowledge and receptiveness to intervention remains unclear (Borg, 2001).

Pedagogical attitudes are another belief identified as shaping educator practice for support children’s development. For instance, educator endorsement of child-centred learning (i.e., children as ahving shared authority and reciprocity in learning, vs. their passive reception of knowledge and instruction; Hur et al., 2015), is associated with organized classroom structures (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2009) and the promotion of children’s autonomy and decision-making (McMullen et al., 2006)—both of which are associated with enhanced self-regulation. Children who are taught by educators taking a child-centred approach also tend to show enhanced outcomes in both academic (Marcon, 2002) and non-academic domains (Hur et al., 2015). Research also suggests that the alignment of educators’ domain-specific (e.g., self-regulation) attitudes and related training is important for adoption of training-endorsed practice (Schultz et al., 2010; Brackett et al., 2012). In the context of self-regulation and learning teacher attitudes about self-regulated learning have been evidenced as positively correlating with and predicting self-reported practices (i.e., the design of learning environments and implementation of instructional strategies conducive to self-regulated learning; Dignath-van Ewijk and van der Werf, 2012; Steinbach and Stoeger, 2018; Yan, 2018) as well teacher openness to engaging with and implementing professional learning (Steinbach and Stoeger, 2018), although these findings have been mixed (Spruce and Bol, 2015).

Lastly, educators’ pedagogical self-efficacy—beliefs about their capacity to engage in practices that achieve desired instructional outcomes (Bandura, 1977)—are found to influence educator’s willingness and efficacy for implementing endorsed practices. Where educators are confident in their ability to implement instructional practices, research shows they are more likely to do so (Turner et al., 2011). In relation to self-regulation, research finds positive associations between educator self-efficacy and the implementation of practices suggested to be important for self-regulation development (e.g., greater support and responsiveness, establishment of positive classroom climates; Guo et al., 2012). In the context of children’s outcomes, however, there is research to suggest a dyadic relationship between teachers self-efficacy to support self-regulation and the expression of children’s self-regulatory abilities. In considering the effects of children’s behavior on teacher self-efficacy Zee et al. (2016) demonstrated externalized behavior as negatively predicting teacher self-efficacy for supportive practice. Findings also suggested that this associations was further exacerbated by the perceived level of classroom misbehavior. Conversely, the same study also found a positive association between children’s prosocial behavior and teacher self-efficacy to engage in supportive practices. Together these findings suggest triadic reciprocal causation (Bandura, 1986) between teacher self-efficacy, educator behavior and children’s self-regulation and necessitate the need for a scale which allows for the investigation of this within early childhood samples.

This study sought to develop and evaluate a tool for measuring educators’ confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy in relation to fostering young children’s self-regulation. Evaluation of the Self-Regulation Knowledge, Attitudes, and Self-Efficacy (Self-Regulation KASE) scale’s construct validity, reliability and predictive validity were conducted utilizing a sample of educators participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial evaluation of the Preschool Situational Self-Regulation Toolkit (PRSIST) Program (Howard et al., 2020). Baseline data (i.e., prior to intervention) were used to evaluate the construct validity and reliability of the scale. Post-intervention data were used to investigate the predictive validity of the Self-Regulation KASE scale with regard to: children’s self-regulation after a year with control group educators (i.e., to what extent did educators beliefs predict child self-regulation, uninfluenced by intervention); and, educators engagement with and perceptions of the intervention. It was expected that lower levels of educator confidence in knowledge and more positive attitudes and higher self-efficacy would be associated with greater program fidelity, thereby suggesting a greater “readiness for change.” It was further expected that child outcomes would be predicted by these educator beliefs, thereby supporting these factors (as captured by this scale) as correlates of children’s development and outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants for this study were recruited from 52 ECEC services to ensure diversity in geography (75% metropolitan), catchment area SES (socioeconomic deciles 1–10; M = 6.20, SD = 2.48), and statutory government assessment rating (i.e., 44% Exceeding, 50% Meeting, 4% Working Toward, 2% unrated against the National Quality Standard). From these services, consent was obtained for 180 educators working with children in their final pre-school year. Complete Self-Regulation KASE scales were returned by 165 educators (98.8% female), a 91.7% participation rate. Participating educators were diverse in their qualifications (4-years degree, n = 61; 2-years diploma, n = 56; 1-year certificate, n = 41; no formal qualifications, n = 7), positions (Director, n = 9; Room Leader, n = 30; Educators, n = 126), employment status (full-time, n = 99; part-time, n = 47; casual, n = 10, did not report, n = 9), and years of experience (M = 10.41, SD = 7.12; range = 0.17–36.00). On average, respondents were employed in their current workplace for 4.35 years (SD = 3.70; range = 0.00–20.00). Responses to 19 individual items were missing for a small number of participants (n = 6). Rather than estimate these values these cases were listwise delete from each analysis.

Predictive validity of children’s self-regulation was investigated in the control group. This subsample was comprised of 66 early childhood educators (98.5% female), from 24 services, who provided start-of-year Self-Regulation KASE data and were still working in the service at post-test data collection (to ensure sufficient opportunity to impact children’s development). While the initial sample included educators from 26 services, one service was excluded from analyses given all participating educators were no longer working in the service at post-test data collection and the second was excluded as they were unable to recruit child participants. The self-regulation of their 207 control group children (47.8% girls, mean age = 4.99 years, SD = 0.39; range = 3.74–5.88) was assessed an average of 6 months after administration of Self-Regulation KASE scales to educators (M = 203.78 days, SD = 18.76, range 175.50–239.00).

Predictive validity of educators’ program engagement and perceptions was examined with the 56 intervention group educators (100% female), from 24 services. As above, the initial sample included educators from 26 services, however, one service was excluded as participating educators were no longer working in the service at post-test data collection and the other did not participate with the program as they were unable to recruit child participants. Participants again included only those who were still working in the service in the same role at post-test data collection and completed all measures. Given random assignment to groups, characteristics of the intervention and control group participants were consistent with those of the full sample (i.e., educator characteristics, child characteristics, average time from baseline to post-test). Informed, written consent was obtained for all participating educators and from the parents/caregivers of all children from whom data were collected.

Measures

Educator Knowledge, Attitude and Self-Efficacy Scale

The Self-Regulation KASE scale was developed to measure educators’ cognitive beliefs (i.e., perceived confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy) in relation to supporting the development of early self-regulation in ECEC contexts. The content of the Self-Regulation KASE scale was devised and revised following a three-step approach (similar to that outlined by Osterlind, 2006). First, a content review of the topic was conducted to determine aspects important for early self-regulation development. On the basis of this review, 45 items were developed that distributed across three hypothesized subscales: confidence in knowledge of self-regulation and self-regulatory development (16 items); attitudes on the nature and importance of early self-regulation (10 items); and self-efficacy for supporting self-regulation (19 items). To reduce positively skewed responses among participants, items in the attitudes subscale included four reverse-scored items. Scale items were then reviewed by an independent sample of 50 early childhood educators for items’ clarity, comprehension and appropriateness and the items were revised on the basis of this feedback.

The final revised scale consisted of 45 statements distributed across three subscales: confidence in knowledge (e.g., “I understand the range of factors that undermine children’s self-regulation”), attitudes (e.g., “I think educators play an important role in fostering children’s self-regulation”) and self-efficacy (e.g., “I feel confident that I can challenge and extend children’s self-regulation abilities in everyday activities”). Whereas self-report measures routinely adopt Likert scales to indicate subjective interpretations of degree (e.g., strongly agree), frequency (e.g., very often) or accuracy of item statements (e.g., very true), the Self-Regulation KASE scale involves a 0–100 rating (following the direction of Bandura, 2006). This was done for two main reasons: 1) easier interpretability for respondents as a percentage (e.g., “I believe I know ∼X% about this topic;” “I am X% confident I could implement this to positive effect”); and 2) to potentiate sufficient sensitivity to change (whereas even just a one point improvement on a five-point Likert scale requires a substantial real-world change to detect—e.g., from “most of the time” to “all the time”). In the current scale, ratings ranged from 0 to 100 for each item in the confidence in knowledge (from 0 = “no knowledge” to 100 = “know everything”), attitudes (from 0 = “do not agree” to 100 = “fully agree”) and self-efficacy subscales (from 0 = “cannot do” to 100 = “very certain can do”). At the time of the preliminary review (see above) educators reported to the researcher that the scale was intuitive and consistent with how they reflect on knowledge and skill (e.g., “I am 80% confident I can do this”). No respondents who completed the scale in the preliminary review or in the current study reported difficulty using this scale (and there were no anomalous values or patterns indicating issues in understanding), and data showed good range and distribution (Table 2).

Preschool Situational Self-Regulation Toolkit Assessment

The PRSIST Assessment (Howard et al., 2019) is an observational measure of early self-regulation whereby children engage in activities and are rated on items relating to their cognitive self-regulation (e.g., “Was the child engaged in the activity throughout its duration?”) and behavioral self-regulation (e.g., “Did the child remain in their seat and rarely fidget?”). The first activity is a group memory card game whereby a group of four children take turns flipping two-cards over at a time to find matching pairs. The number of matching pairs varies by child age (e.g., Eight pairs for 4-year-olds, 14 pairs for 5-year-olds) with each game taking approximately 10 min to complete. The second activity is an individual curiosity boxes activity which takes approximately 5-min to complete. In this activity children are presented with three boxes of increasing size and are asked to guess the contents of each box. To guess, children are instructed to follow four sequential steps and provide a guess after each step, this includes: 1) looking at the box (no touching); 2) gently lifting the box (no shaking); 3) shaking the box; and 4) closing their eyes and feeling the object in the box (no peeking). Rather than accuracy, children’s performance on each of these tasks is scored based on observed behaviors. Specifically, observers rate each item on a seven-point Likert scale, with these scores reflecting the frequency and/or extent of that behavior. Children’s self-regulation was rated at the end of each activity, yielding two self-regulation ratings per child, which were averaged to derive cognitive and behavioral self-regulation indices. For this study the PRSIST Assessment was administered by trained research assistants who had exceeded minimum inter-rater reliability thresholds (i.e., a minimum correlation between ratings greater than r = 0.70 a mean difference in ratings less than 0.75 points and at least 80% of item ratings within one point). Training included the completion of an online training and assessment of rating (www.eytoolbox.com.au) as well as five joint observation and rating sessions alongside a member of the research team using video data. This measure has shown good construct validity, reliability (α ranging from 0.86 to 0.95), and concurrent validity with task-based self-regulation (rs ranging from 0.50 to 0.63) and school readiness measures (rs between 0.66 and 0.75; Howard et al., 2019).

Educator Program Engagement

Educators’ engagement with the program was evaluated in terms of their completion of the online professional development modules. This was captured via log in and tracking functionality of the program website (and confirmed with educator report). A stated requirement of the intervention was the educators’ engagement with the online training modules. Participant engagement was considered as an ordinal construct (i.e., 0 = did not make any attempt to engage with online training, 1 = engaged with less than half of the online training modules; 2 = engaged with more than half of the online training modules; and, 3 = engaged with all of the online training modules).

Educator Program Perceptions

An adaptation of the Teacher Attitudes about Social and Emotional Learning (TASEL; Schultz et al., 2010) questionnaire was administered to intervention group educators at the end of the program, over 6 months later (M = 197.46 days, SD = 18.12, range = 161.50–225.60). The original TASEL questionnaire includes 22-items scored on a six-point Likert scale (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 6 = “strongly agree”) yielding six subscales (for the complete list of items and subscales, see Schultz et al., 2010). This study used only eight relevant items relating to: 1) self-perceived confidence to deliver the program (Competence); and, 2) perceptions of program effectiveness (Effectiveness). The original wording of each item was retained, with “The PRSIST program” identified as the program and “self-regulation” identified as the targeted skill (e.g., “Programs such as the PRSIST program are effective in helping children learn self-regulation skills”).

Procedure

Prior to any data collection, written informed consent was obtained from the centre directors, educators and parents/caregivers of children who participated in this research. Proceeding this, the Self-Regulation KASE scale was distributed to participants electronically (or hard copy via registered post as needed) at the time of baseline data collection, before commencement of the intervention. Completed scales were collected either by research assistants attending the service for child data collection or emailed back electronically. Predictive validity measures (i.e., PRSIST Assessment, TASEL adaptation, engagement metrics) were collected at post-test assessment, per protocols published prior to study commencement (Howard et al., 2020). The average duration between baseline and post-test assessment was 200.62 days (SD = 18.52, Range = 161.50–239.00). Ethics approval for this research was provided by the University of Wollongong’s Human Research Ethics Committee (2017/451).

Plan for Analysis

Construct validity of the Self-Regulation KASE scale was evaluated using exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and internal consistency analyses. Given that traditional analyses overlook other important features of a scale’s function, however, Rasch analyses were also conducted. Rasch analyses permitted the additional evaluation of: whether items discriminated well between those higher and lower in the underlying construct (confidence in knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy), item misfit; whether the scale functioned similarly across respondent characteristics (e.g., educator qualifications), or differential item functioning; whether some items were too highly correlated, or local dependence; and whether each subscale measured a single underlying construct, or unidimensionality. Together, the analyses offer comprehensive and robust evaluation of validity, reliability, and appropriate function of the scale—essential conditions for its use in subsequent research.

To also investigate the predictive validity of educators’ responses to Self-Regulation KASE, linear regression analyses were conducted. Educators’ start-of-year Self-Regulation KASE scores were used to predict, at end-of-year: 1) child self-regulation scores (control group); and, 2) engagement and perceptions of the program (intervention group). To predict end-of-year child outcomes, a room-average of child self-regulation scores were regressed on room-average Self-Regulation KASE scores, given the influence of multiple educators per child, and small and inconsistent numbers of educators per room that precluded multi-level analyses. Further, ordinal logistic regression was also conducted on the intervention group educators’ start-of-year Self-Regulation KASE scores to predict engagement with the professional development training.

Results

Construct Validity: Exploratory Factor Analysis

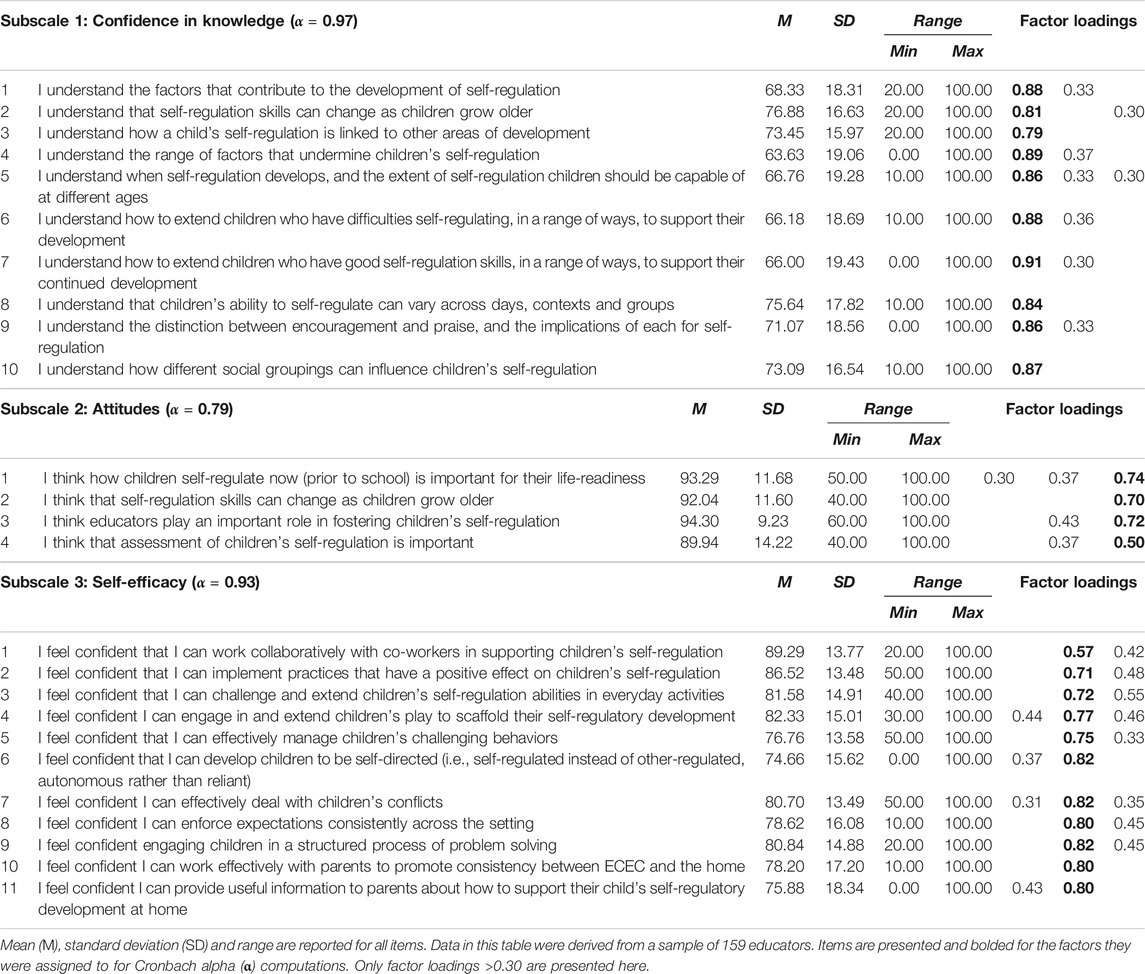

First, separate EFAs were conducted for each item set (confidence in knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy), using maximum likelihood estimation and oblique (direct oblimin) factor rotation as it was expected that items would be correlated. The number of factors extracted was determined by the Guttman-Keiser criterion (eigenvalues > 1; Kaiser, 1960) and inspection of scree plots. Item assignment was determined by factor loadings (>0.30) and theoretical justification (in cases of cross-loadings). In all cases, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values were acceptable (all >0.75) and Bartlett’s tests of sphericity were significant (ps <0.01), indicating that the sample and inter-item correlations were sufficiently large to justify EFA analysis. All items retained in the final scale and their descriptive statistics, factor allocation and factor loadings are provided in Table 1.

Confidence in Knowledge

For the 16 items on confidence in knowledge of self-regulation, examination of eigenvalues and scree plots supported a one-factor structure that explained 74.8% of the variance in educators’ ratings. All items loaded well on this factor. Reliability analysis indicated high internal consistency for confidence in knowledge items (α = 0.98).

Attitudes

For the 10 attitude items, eigenvalues and scree plot supported a three-factor solution that explained 60.7% of the variance in educators’ responses. The first factor can broadly be considered as attitudes around the importance and development of self-regulation, consisting of three items. Although loading most highly on a separate factor, two additional items cross-loaded onto this factor and were conceptually similar, and thus were included in this factor. Reliability analysis indicated high internal consistency amongst these items (α = 0.81). The resultant factor thus includes items around: the importance of early self-regulation; its growth with age; and, educators’ role in supporting its growth. The two other attitudes factors were unreliable (αs = 0.66, 0.44), and thus were not considered for further analysis. To confirm the one-factor structure, a final EFA was conducted on retained items, which yielded a one-factor structure that explained 58.6% of the variance.

Self-Efficacy

For the 19 items on self-efficacy to support children’s self-regulation, eigenvalues suggested a four-factor structure with a strong first factor explaining 56.4% of variance (the second through fourth factor each explained <10%), whereas scree plots suggested a one-factor structure. All factor loadings were >0.39 on the first dominant factor, providing further support for a one factor solution. Reliability analysis indicated high internal consistency amongst these items (α = 0.95), supporting this one-factor solution.

Modern Test Theory Evaluation: Rasch Analysis

The polytomous Rasch model (PRM) with partial credit parameterization was run for all subsequent analyses, using Rasch Unidimensional Measurement Modeling 2030 software (Andrich et al., 2010).

Model Fit

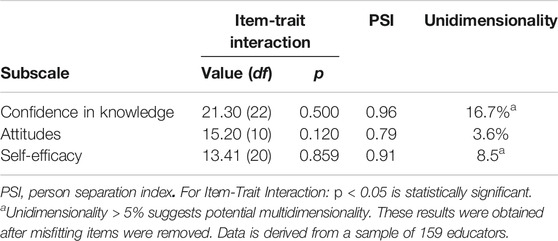

Overall fit of the data to theoretical expectations of the Rasch model is tested by the item-trait interaction Χ2 statistic, whereby the null hypothesis is that the data fit the model. All three subscales indicated good fit to the model (all ps > 0.10; Table 2). The person separation index (PSI), which provides a reliability estimate similar to Cronbach’s alpha, indicated good to excellent reliability (0.79–0.96) for all three scales.

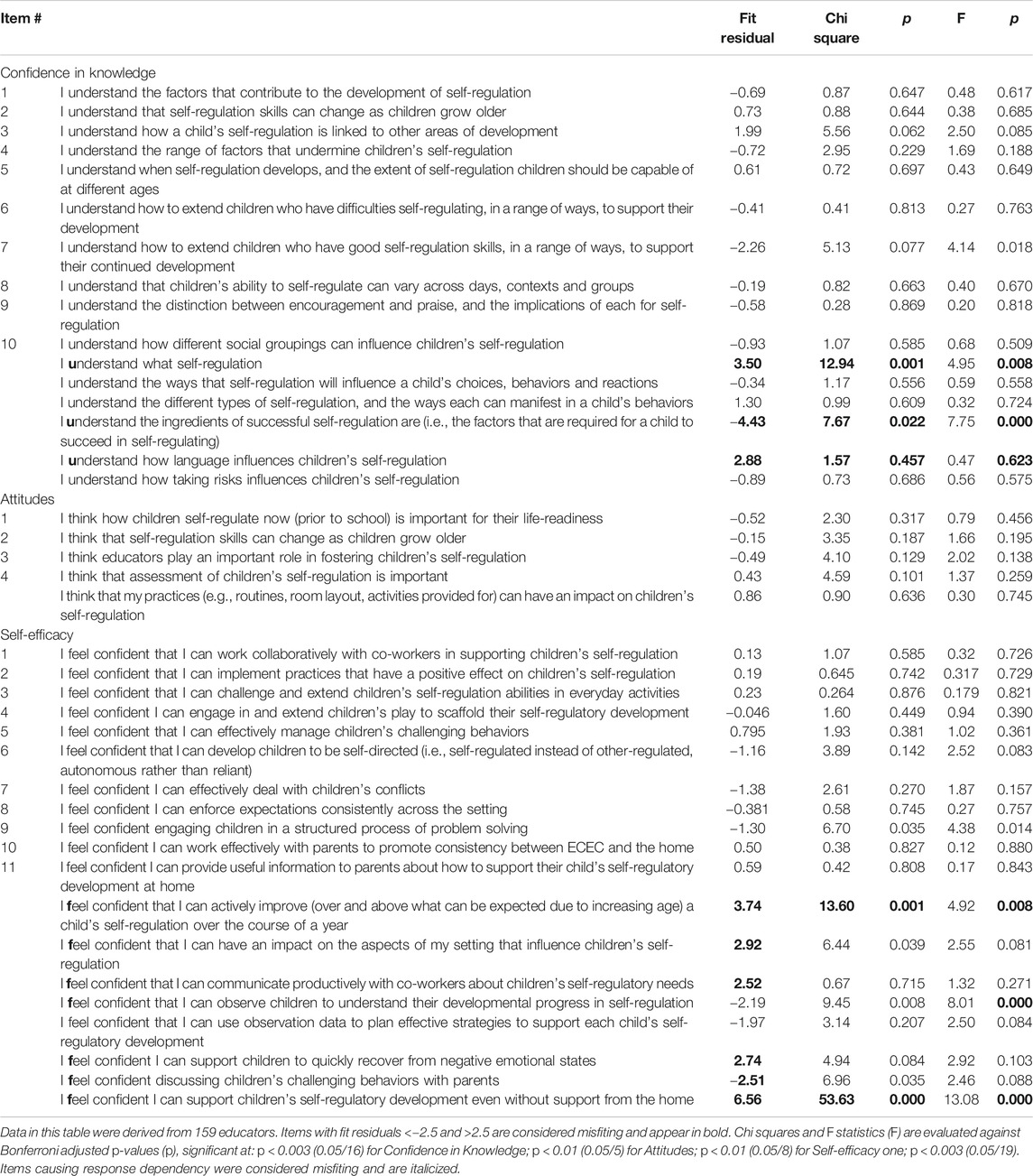

Item Fit

Each item was examined to determine whether they discriminated well between those higher and lower in the underlying construct (e.g., confidence in knowledge). Item misfit is detected by: 1) fit residuals that exceed the acceptable ranges (i.e., <−2.50 or >2.50); 2) significant chi square and F statistics, whereby the null hypothesis is that an item fits the Rasch model (i.e., p < 0.05 indicates misfit); and 3) graphically through each item’s characteristic curves (ICCs), which plots the item’s raw data against the theoretical model estimates. Inspection of fit statistics and ICCs indicated misfit in three items of the confidence in knowledge subscale: I understand what self-regulation is, fit residual = 3.50, Χ2 = 12.94, p < 0.002, F = 4.95, p < 0.009; I understand the ingredients of successful self-regulation are (i.e., the factors that are required for a child to succeed in self-regulating), fit residual = −4.43, Χ2 = 7.67, p <0.03, F = 7.75, p < 0.001; I understand how language influences children’s self-regulation, fit residual = 2.88, Χ2 = 1.57, p = 0.46, F = 0.47, p = 0.623). In the Self-Efficacy subscale, misfit was detected in seven items: I feel confident that I can actively improve (over and above what can be expected due to increasing age) a child’s self-regulation over the course of a year, fit residual = 3.74, Χ2 = 13.60, p < 0.002; F = 4.92, p < 0.009; I feel confident that I can have an impact on the aspects of my setting that influence children’s self-regulation, fit residual = 3.17; I feel confident that I can communicate productively with co-workers about children’s self-regulatory needs, fit residual = 3.17, I feel confident I can observe children to understand their developmental progress in self-regulation, F = 8.01, p < 0.001; I feel confident I can support children to quickly recover from negative emotional states, fit residual = 2.74; I feel confident discussing children’s challenging behaviors with parents, fit residual = 2.51; I feel confident I can support children’s self-regulatory development even without support from the home, fit residual = 6.56, Χ2 = 53.63, p < 0.001; F = 13.08, p < 0.001. For a summary of fit and misfit statistics see Table 3. Misfitting items were removed due to these issues of misfit and, on further reflection on the scale items, conceptual misalignment with remaining items. All other subscales indicated appropriate item fit.

Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

DIF was conducted to evaluate whether the scale functioned similarly across respondent characteristics (e.g., educator experience). That is, DIF evaluates whether two or more groups of individuals with differing characteristics (e.g., recent graduates, mid-service professionals, long-service professionals) with the same levels of the trait respond differently to certain items. Ideally, measurement scales should be sample independent, and significant DIF can indicate misfit to the Rasch model. We evaluated DIF as a function of: 1) educator qualification; and 2) number of years in the sector. DIF was found for one item in the Attitudes subscale: I think that my practices (e.g., routines, room layout, activities provided for) can have an impact on children’s self-regulation (F = 7.78, p < 0.001). This item was removed from the scale due to its differential item functioning.

Test of Local Dependence

An important assumption of the Rasch model is that how a person responds to one item should not affect their response on any other. In order to test this assumption a principal components analysis (PCA) is run on standardized residuals (the “left over” components after the variance associated with the construct under measure is extracted from the data; Tennant and Conaghan, 2007). The residual correlation matrix revealed that in the confidence in knowledge subscale, four pairs of items were highly correlated (r > 0.30): I understand the ways that self-regulation will influence a child’s choices, behaviors and reactions with Item 3 (r = 0.48); I understand the different types of self-regulation, and the ways each can manifest in a child’s behaviors with Item 4 and Item 5 (rs = 0.31 and 0.32); and I understand how taking risks influences children’s self-regulation with Item 10 (r = 0.32). In Self-Efficacy, the residuals were highly correlated for Item 4 with I feel confident that I can use observation data to plan effective strategies to support each child’s self-regulatory development (r = 0.47); and Item 9 with I feel confident discussing children’s challenging behaviors with parents (r = 0.33). The italicized items above were removed on the basis of retaining the stronger item (e.g., had less effect on subscale reliability, most conceptually aligned), which resolved these response dependency issues and significantly improved fit statistics (from p = 0.29 to p = 0.86 of the item trait interaction Χ2). The decision was made to retain item 9 over I feel confident discussing children’s challenging behaviors with parents, given the latter was problematic in terms of item misfit.

Unidimensionality

Final analyses evaluated whether resultant subscales measured a single underlying construct. When a small number of cases are significantly different from each other (<5% of the total sample) this is taken as evidence of the scale’s unidimensional structure. Smith’s (2002) t-tests at the 5% level indicated that subscale for Attitudes (3.6%) had a unidimensional structure. The self-efficacy (8.5%) and confidence in knowledge (16.7%) subscales indicated some evidence of violation of unidimensionality assumptions (Table 2), suggesting these subscales may have been tapping into more than one common dimension. A final EFA was conducted on the Rasch-reduced scale to further examine this possibility.

Final EFA on Rasch-Reduced Scale

A final EFA was run on all retained scale items. Again, the KMO statistic indicated sufficient sampling, KMO = 0.91, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant X2(300) = 3,482, p < 0.01. Eigenvalues and scree plots supported a three-factor structure—such that all items loaded on their anticipated confidence in knowledge, attitudes or self-efficacy subscale—that explained 69.1% of the variance. Item allocations and factor loadings are presented in Table 1.

Correlations Between Subscales

Correlation analyses were used to investigate the relationship between the three subscales after item removal. Results suggest that correlations between all subscales were statistically significant (ps < 0.01). Analysis showed moderate associations between attitudes and self-efficacy (r = 0.49) and weaker associations for confidence in knowledge with attitudes (r = 0.25) and with self-efficacy (r = 0.39).

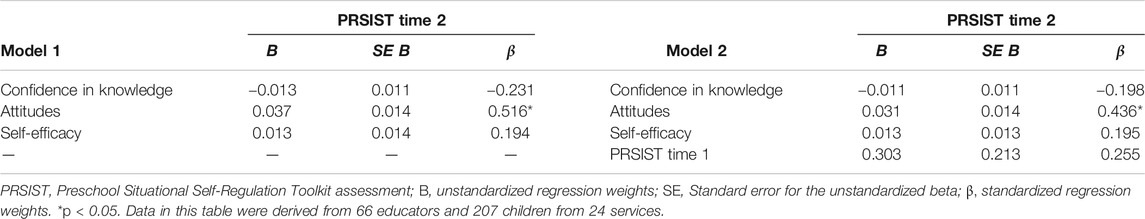

Prediction of Child Outcomes: Linear Regression

To extend evidence for the validity of the scale in relation to its associations with educators’ actual behaviors and child outcomes, two linear regressions were undertaken. In the control group subsample, when all predictor variables were analyzed together educator attitudes at the start of the year significantly predicted children’s end-of-year self-regulation scores, F (3, 20) = 4.39, p = 0.016, R2 = 0.40, β = 0.52, p = 0.017, as well as change in children’s self-regulation scores across the year (i.e., evaluated by inclusion of children’s baseline self-regulation as a covariate), F (4, 19) = 3.97, p = 0.017, R2 = 0.46, β = 0.44, p = 0.045. Neither confidence in knowledge nor self-efficacy significantly predicted children’s self-regulation outcomes. All predictor standardized beta (β) weights and p values are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Predictors of children’s scores on the Preschool Situational Self-Regulation Toolkit (PRSIST) Assessment.

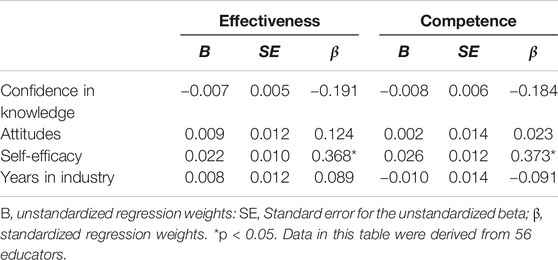

Prediction of Perceived Program Effectiveness and Competency to Implement: Linear Regression

Linear regression analyses were undertaken to examine the relationship between educators’ confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy and: 1) educator perceptions about the potential efficacy of self-regulation intervention programs like the PRSIST program; and 2) educators’ perceived competency to implement the PRSIST program, controlling for years of experience. When all predictor variables were analyzed together only the self-efficacy subscale was a significant predictor of educators’ perceptions of self-regulation program effectiveness, F (4, 51) = 2.69, p = 0.041, R2 = 0.17, β = 0.37, p = 0.037, and their perceived competence to implement the PRSIST program, F (4, 51) = 2.19, p = 0.084, R2 = 0.15, β = 0.37, p = 0.037. Confidence in knowledge and attitudes were not significant predictors for either outcome variable (although attitudes was a significant predictor of perceived effectiveness when considered independently, F (2, 53) = 2.58, p = 0.085, R2 = 0.09 β = 0.30, p = 0.029). All predictor standardized beta (β) weights and p values are reported in Table 5.

TABLE 5. Predictors of educators’ perceptions of program effectiveness and competence to implement the PRSIST program.

Prediction of Educator Engagement: Ordinal Logistic Regression

Finally, to investigate the extent to which Self-Regulation KASE ratings predicted educators’ actual engagement with the PRSIST program, an ordinal logistic regression was run using participation in the online professional development modules as the outcome variable. Results indicated that none of the subscales significantly predicted educator engagement in the online professional development training when analyzed together, χ2(3) = 4.20, p = 0.241: confidence in knowledge, B = −0.001, SE = 0.015, p = 0.971 (95% CI: −0.03 to 0.03); attitudes, B = 0.048, SE = 0.037, p = 0.196 (95% CI: −0.03 to 0.12); and self-efficacy, B = 0.014, SE = 0.029, p = 0.644 (95% CI: −0.04 to 0.07).

While these results indicated no significant prediction of educator beliefs on their engagement with the intervention, there was a priori theoretical reason to expect that these beliefs may be influential to educators’ instigation of an intervention. Follow-up binary logistic regressions thus regressed child self-regulation outcomes on educators’ instigation of the intervention (0 = did not commence, 1 = any to complete engagement). Results indicated both attitudes, χ2(1) = 6.94, p = 0.008, OR = 1.09 (95% CI: 1.02–1.17), p = 0.015, and self-efficacy, χ2(1) = 4.80, p = 0.028, OR = 1.06 (95% CI: 1.00–1.12), p = 0.035, significantly predicted whether educators instigated engagement with online professional development, however, confidence in knowledge was not a significant predictor, χ2(1) = 2.24, p = 0.134, OR = 1.02 (95% CI: 0.99–1.06).

Discussion

The current study sought to develop and evaluate a new self-report measure of early childhood educators’ confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy for supporting children’s self-regulation development. Evaluation of the Self-Regulation KASE scale supported a 25-item scale yielding three distinct—yet related—reliable subscales: confidence in knowledge about self-regulation (10 items); attitudes around the importance and development of self-regulation (four items); and self-efficacy to support self-regulation development (11 items). Predictive validity was also demonstrated. For participants engaging in routine practice, educators’ attitudes at baseline significantly predicted children’s end-of-year status and change in self-regulation, more than 6 months later. For educators engaged in a practice-based self-regulation intervention, self-efficacy at baseline predicted educator perceptions around the effectiveness of the program and their confidence to implement it. In contrast to other scales for assessing educators’ cognitive beliefs in relation to child development, this scale provides: insights specifically related to child self-regulation; integration of multiple important factors influencing educators’ practice and readiness for change; and predictive validity evidence supporting this. While further use of this scale should be evaluated among different and broader samples of early childhood educators, the triangulation of validity evidence supports the integrity and practical utility of the Self-Regulation KASE scale.

Results indicated a valid and reliable four-item attitude subscale, capturing aspects related to the importance and development of early self-regulation. While educator attitudes around self-regulation were generally positive (e.g., early self-regulation is important; educators can have an impact on children’s self-regulation), this was not universally the case and variability in responses predicted children’s end-of-year self-regulation status and change for those engaging in routine practice. This is consistent with suggestions that educators’ attitudes towards children’s learning differentially predict adopted practices (McMullen et al., 2006) and the developmental outcomes of children in their care (Youn, 2016). Replication of this finding in the current study, in relation to self-regulation, suggests the valid and sensitive capture of educators’ self-regulation attitudes using this scale.

For those engaging in a professional practice intervention, contrary to expectations (Bandura, 2006) educator attitudes at the commencement of the study were not significantly associated with their program perceptions (i.e., program effectiveness and competence to implement) or engagement with the professional development training (Steinbach and Stoeger, 2018). Given the positive association between attitudes and self-efficacy (Savolainen et al., 2012; Özokcu, 2018), and their moderate correlation in these data, it may be that when analyzed concurrently self-efficacy serves as a stronger, more-direct predictor of educators’ program perceptions and engagement. Attitudes, by contrast, might have a more indirect role in this regard (e.g., attitudes influencing information search behaviors and self-efficacy). Alternatively, it may be that other factors related to the individual (e.g., educator burnout) or the organization (e.g., perceived curricula or managerial support) play a moderating role (Ransford et al., 2009). When analyzing engagement as a binary construct, however, educators attitudes did predict whether educators made any initial attempts to engage with the program (irrespective of whether they completed it). This finding is consistent with the literature which suggests cognitive beliefs such as attitudes to be important for intentions to engage with professional learning (Demir, 2010; Dunn et al., 2018). It is important for future research to investigate the nature of this relationship between educator attitudes, behavior and children’s self-regulation outcomes.

Consistent with suggestions in the literature (Deforest and Hughes, 1992), educators’ self-efficacy was the stronger predictor of perceptions of effectiveness of the self-regulation intervention and their competence to implement it. While perceptions of a program and its probability of success are likely to be important precursors to engagement with said program, findings from this study did not support a significant association between educator self-efficacy and variable engagement with the program. When analyzing engagement as a binary construct, however, self-efficacy did predict whether educators made any initial attempts to engage with the program (irrespective of whether they completed it). Rationalizing this finding, engagement with the intervention may have been moderated by contextual factors (e.g., time, managerial support, accessibility of resources) or educator perceptions regarding the novelty of content (i.e., whether or not it contained already acquired information). Nevertheless, the above findings in conjunction with evidence for the variability of self-efficacy across content areas (i.e., self-efficacy differs across mathematics and literacy instruction; Gerde et al., 2018) highlights the necessity for measurement of domain-specific self-efficacy where currently it is often measured as a general construct (e.g., the Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale; Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2001). The validation of a reliable scale for measuring educators’ self-efficacy to support self-regulation development is thus potentially useful for appraising readiness for change in ECEC-based self-regulation interventions.

While research supports the facilitative role of educator self-efficacy for children’s outcomes—a finding which was non-significant in the current study—it may be that other factors moderated the strength of this association. For instance, despite educator confidence to support self-regulatory development, structural aspects within the ECEC setting (e.g., time, allocation of resources, managerial support) may have inhibited the enaction of such practice. In the instance that educators did enact practice supportive of self-regulatory development, confounding variables related to the child (e.g., sleep, stress, language abilities; Blaire, 2010; Bohlmann et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2017), the home learning environment (e.g., parental instruction; Williams and Berthelsen, 2017) or peers (Montroy et al., 2016a) may have exerted a stronger influence on children’s self-regulatory development. Despite a non-significant finding in these data, the development and validation of a scale measuring educators self-efficacy specifically with regard to supporting early self-regulation potentiates further investigation of the suggested relationship between self-efficacy, enacted practice and children’s self-regulatory outcomes (e.g., Guo et al., 2012).

Despite a documented tendency for respondents to overestimate their knowledge (Epstein et al., 1984), there are also findings that confidence in knowledge is influential to consequent behaviors (Radecki and Jaccard, 1995; Borg, 2001; Sanchez, 2014). This scale captured variability amongst educator responses of their confidence in knowledge; however, this did not predict educators’ perceptions of, or engagement with, the program, or children’s self-regulation outcomes. Indeed, there is a prevailing lack of clarity around the specific nature of this purported relationship. On the one hand, low confidence in knowledge has been associated with implementation of shallower learning experiences (e.g., lecturing vs. interactive child-centred approaches) and the avoidance of direct instruction and spontaneous or impromptu teaching (Borg, 2001, Borg, 2005). On the other hand, studies examining confidence in knowledge in grammar instruction have reported a negative relationship between confidence in grammar knowledge and incidence of grammar instruction (Pahissa and Tragant, 2009). While the exact nature of the relationship between confidence in knowledge and learning/instructional practice is unclear, the current scale provides a means from which to further investigate these issues.

Limitations and Future Directions

Following from these comprehensive analyses (i.e., EFA, Rasch) and triangulation of results (i.e., predictive validity) to evaluate this scale, future research should seek to confirm the structure and function of the scale through confirmatory factor analysis with different and broader samples of educators. While the high proportion of females in this sample (98.8%) is reflective of the sector, future research should seek to explore potential gender differences in terms of the scale’s function. Given the good range in distribution afforded by the 0–100 scale and extending the utility of the scale, future research should also seek to investigate the extent to which self-report ratings on this scale are susceptible to change (i.e., after time) to examine the viability of this scale as measure of change for self-regulation interventions targeting educator characteristics and instructional practice.

Conclusion

Results from this study demonstrate support for the viability of this educator-report questionnaire of their confidence in knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy around supporting early self-regulation development. The scale showed converging evidence of construct reliability and predictive validity, which potentiates theoretical, empirical and intervention research for exploring early childhood educators’ roles in generating change in children’s self-regulation (and under what conditions this occurs). Given the importance of self-regulation for children’s short- and long-term outcomes, and the significant role of early education in influencing this development, this scale is an important facilitator for understanding those characteristics that are likely to underpin the engagement, learning and practices of educators in relation to fostering children’s early self-regulation.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset for this article is not publicly available because ethics approval was not sought or granted for such use. Requests to access the dataset should be directed to EV at ZXY5OTNAdW93bWFpbC5lZHUuYXUu

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Wollongong (2017/451). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants directly or by their legal guardian/next of kin where required.

Author Contributions

EV instigated the study, designed the scale, managed data collection and entry, contributed to analysis and led writing of the manuscript. CN-H contributed to conceptualization of the study and scale, and to drafting of the manuscript. JE led data analysis and contributed to drafting of the manuscript. KC contributed to drafting of the manuscript. SH contributed to conceptualization of the study, design of the scale, oversaw data collection and analysis, and contributed to drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award grant (No.: DE170100412).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Andrich, D., Sheridan, B., and Luo, G. (2010). RUMM2030: a windows program for the Rasch unidimensional measurement model. Perth, WA: RUMM Laboratory.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84 (2), 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychol. 3 (3), 265–299. doi:10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03

Bandura, A. (2006). “On integrating social cognitive and social diffusion theories,” in Communication of innovations: a journey with Ev Rogers. Editors A. Singhal, and J. W. Dearing, 111–135.

Barnett, W. S., Jung, K., Yarosz, D. J., Thomas, J., Hornbeck, A., Stechuk, R., et al. (2008). Educational effects of the Tools of the Mind curriculum: a randomized trial. Early Child. Res. Q. 23 (3), 299–313. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.03.001

Baumeister, R. F., and Heatherton, T. F. (1996). Self-regulation failure: an overview. Psychol. Inq. 7 (1), 1–15. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0701_1

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2013). “The COACTIV model of teachers’ professional competence,” in Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers. Results from the COACTIV project. Editors M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, and M. Neubrand (Boston, MA: Springer) 25–48.

Blair, C. (2010). Stress and the development of self-regulation in context. Child Dev. Perspect. 4 (3), 181–188. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00145.x

Blömeke, S. (2017). “Modelling teachers’ professional competence as a multi-dimensional construct,” in Pedagogical knowledge and the changing nature of the teaching profession. Editor S. Guerriero (Paris: Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing) 119–135.

Bodrova, E., and Leong, D. (2007). Tools of the mind: the Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. 2nd Edn. Columbus, OH: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Bohlmann, N. L., Maier, M. F., and Palacios, N. (2015). Bidirectionality in self-regulation and expressive vocabulary: comparisons between monolingual and dual language learners in preschool. Child Dev. 86 (4), 1094–1111. doi:10.1111/cdev.12375

Borg, S. (2001). Self-perception and practice in teaching grammar. ELT J. 55 (1), 21–29. doi:10.1093/elt/55.1.21

Borg, S. (2005). “Experience, knowledge about language and classroom practice in teaching grammar,” in Applied linguistics and language teacher education. Editor N. Bartels, 325–340.

Brackett, M. A., Reyes, M. R., Rivers, S. E., Elbertson, N. A., and Salovey, P. (2012). Assessing teachers’ beliefs about social and emotional learning. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 30 (3), 219–236. doi:10.1177/0734282911424879

Burman, J. T., Green, C. D., and Shanker, S. (2015). On the meanings of self-regulation: digital humanities in service of conceptual clarity. Child Dev. 86 (5), 1507–1521. doi:10.1111/cdev.12395

Deforest, P. A., and Hughes, J. N. (1992). Effect of teacher involvement and teacher self-efficacy on ratings of consultant effectiveness and intervention acceptability. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 3 (4), 301–316. doi:10.1207/s1532768xjepc0304_2

Demir, K. (2010). Predictors of internet use for the professional development of teachers: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Teach. Dev. 14 (1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/13664531003696535

Diamond, A., and Lee, K. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science 333 (6045), 959–964. doi:10.1126/science.1204529

Diamond, A., Lee, C., Senften, P., Lam, A., and Abbott, D. (2019). Randomized control trial of Tools of the Mind: marked benefits to kindergarten children and their teachers. PloS One 14 (9), e0222447. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222447

Dignath-van Ewijk, C., and van der Werf, G. (2012). What teachers think about self-regulated learning: investigating teacher beliefs and teacher behavior of enhancing students’ self-regulation. Educ. Res. Int. 2012, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2012/741713

Dunn, R., Hattie, J., and Bowles, T. (2018). Using the “Theory of Planned Behavior” to explore teachers’ intentions to engage in ongoing teacher professional learning. Stud. Educ. Eval. 59, 288–294. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.10.001

Epstein, W., Glenberg, A. M., and Bradley, M. M. (1984). Coactivation and comprehension: contribution of text variables to the illusion of knowing. Mem. Cognit. 12 (4), 355–360. doi:10.3758/BF03198295

Fukkink, R. G., and Lont, A. (2007). Does training matter? A meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Child. Res. Q. 22 (3), 294–311. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.04.005

Gerde, H. K., Pierce, S. J., Lee, K., and Van Egeren, L. A. (2018). Early childhood educators’ self-efficacy in science, math, and literacy instruction and science practice in the classroom. Early Educ. Dev. 29 (1), 70–90. doi:10.1080/10409289.2017.1360127

Guo, Y., Connor, C. M., Yang, Y., Roehrig, A. D., and Morrison, F. J. (2012). The effects of teacher qualification, teacher self-efficacy, and classroom practices on fifth graders' literacy outcomes. Elem. Sch. J. 113 (1), 3–24. doi:10.1086/665816

Hammond, L. (2015). Early childhood educators’ perceived and actual metalinguistic knowledge, beliefs and enacted practice about teaching early reading. Aust. J. Learn. Difficulties 20 (2), 113–128. doi:10.1080/19404158.2015.1023208

Hofmann, W., Schmeichel, B. J., and Baddeley, A. D. (2012). Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends Cognit. Sci. 16 (3), 174–180. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.006

Howard, S. J., Neilsen-Hewett, C., de Rosnay, M., Vasseleu, E., and Melhuish, E. (2019). Evaluating the viability of a structured observational approach to assessing early self-regulation. Early Child. Res. Q. 48 (3), 186–197. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.03.003

Howard, S. J., Vasseleu, E., Batterham, M., and Neilsen-Hewett, C. (2020). Everyday practices and activities to improve pre-school self-regulation: cluster RCT evaluation of the PRSIST program. Front. Psychol. 11, 137. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00137

Howard, S. J., and Williams, K. E. (2018). Early self-regulation, early self-regulatory change, and their longitudinal relations to adolescents’ academic, health, and mental well-being outcomes. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 39 (6), 489–496. doi:10.1097/DBP.0000000000000578

Hur, E., Buettner, C. K., and Jeon, L. (2015). The association between teachers’ child-centered beliefs and children’s academic achievement: the indirect effect of children’s behavioral self-regulation. Child Youth Care Forum. 44 (2), 309–325. doi:10.1007/s10566-014-9283-9

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 20 (1), 141–151. doi:10.1177/001316446002000116

Marcon, R. A. (2002). Moving up the grades: relationship between preschool model and later school success. Early Child. Res. Pract. 4 (1), 25.

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., et al. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Dev. 79 (3), 732–749. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x

McMullen, M. B., Elicker, J., Goetze, G., Huang, H. H., Lee, S. M., Mathers, C., et al. (2006). Using collaborative assessment to examine the relationship between self-reported beliefs and the documentable practices of preschool teachers. Early Child. Educ. J. 34 (1), 81–91. doi:10.1007/s10643-006-0081-3

Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Ariescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., et al. (2015). A review of research on the effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) upon child development. CARE project; curriculum quality analysis and impact review of European ECEC. Available at: https://ecec-care.org/fileadmin/careproject/Publications/reports/new_version_CARE_WP4_D4_1_Review_on_the_effects_of_ECEC.pdf. (Accessed September 10, 2020).

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108 (7), 2693–2698. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010076108

Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., and Skibbe, L. E. (2016a). The effect of peers’ self-regulation on preschooler’s self-regulation and literacy growth. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 46, 73–83. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2016.09.00

Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., Skibbe, L. E., McClelland, M. M., and Morrison, F. J. (2016b). The development of self-regulation across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 52 (11), 1744–1762. doi:10.1037/dev0000159

Osterlind, S. J. (2006). Modern measurement: theory, principles, and applications of mental appraisal. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Özokcu, O. (2018). The relationship between teacher attitude and self-efficacy for inclusive practices in Turkey. J. Edu. Train. 6 (3), 6–12. doi:10.11114/jets.v6i3.3034

Pahissa, I., and Tragant, E. (2009). Grammar and the non-native secondary school teacher in Catalonia. Lang. Aware. 18 (1), 47–60. doi:10.1080/09658410802307931

Park, C. W., Gardner, M. P., and Thukral, V. K. (1988). Self-perceived knowledge: some effects on information processing for a choice task. Am. J. Psychol. 101 (3), 401–424. doi:10.2307/1423087

Radecki, C., and Jaccard, J. (1995). Perceptions of knowledge, actual knowledge, and information search behaviour. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 31 (2), 107–138. doi:10.1006/jesp.1995.1006

Ransford, C. R., Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Small, M., and Jacobson, L. (2009). The role of teachers’ psychological experiences and perceptions of curriculum supports on the implementation of a social and emotional learning curriculum. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 38 (4), 510–532. Available at: http://www.nasponline.org/publications/spr/spr384index.aspx (Accessed January 10, 2020).

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Curby, T. W., Grimm, K. J., Nathanson, L., and Brock, L. L. (2009). The contribution of children’s self-regulation and classroom quality to children’s adaptive behaviors in the kindergarten classroom. Dev. Psychol. 45 (4), 958–972. doi:10.1037/a0015861

Sanchez, H. S. (2014). The impact of self‐perceived subject matter knowledge on pedagogical decisions in EFL grammar teaching practices. Language Awareness 23 (3), 220–233. doi:10.1080/09658416.2012.742908

Sanders, M. R., and Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2013). The promotion of self-regulation through parenting interventions. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 16 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10567-013-0129-z

Sangster, P., Anderson, C., and O’Hara, P. (2013). Perceived and actual levels of knowledge about language amongst primary and secondary student teachers: do they know what they think they know? Lang. Aware. 22 (4), 293–319. doi:10.1080/09658416.2012.722643

Savolainen, H., Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., and Malinen, O.-P. (2012). Understanding teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy in inclusive education: implications for pre-service and in-service teacher education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 27 (1), 51–68. doi:10.1080/08856257.2011.613603

Schultz, D., Ambike, A., Stapleton, L. M., Domitrovich, C. E., Schaeffer, C. M., and Bartels, B. (2010). Development of a questionnaire assessing teacher perceived support for and attitudes about social and emotional learning. Early Educ. Dev. 21 (6), 865–885. doi:10.1080/10409280903305708

Spruce, R., and Bol, L. (2015). Teacher beliefs, knowledge, and practice of self-regulated learning. Metacogn. Learn. 10 (2), 245–277. doi:10.1007/s11409-014-9124-0

Steinbach, J., and Stoeger, H. (2018). Development of the teacher attitudes towards self-regulated learning scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 34 (3), 193–205. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000322

Tennant, A., and Conaghan, P. G. (2007). The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: what is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Care Res. 57 (8), 1358–1362. doi:10.1002/art.23108

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17 (7), 783–805. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Turner, K. M. T., Nicholson, J. M., and Sanders, M. R. (2011). The role of practitioner self-efficacy, training, program and workplace factors on the implementation of an evidence-based parenting intervention in primary care. J. Prim. Prev. 32 (2), 95–112. doi:10.1007/s10935-011-0240-1

Wass, S. V., Scerif, G., and Johnson, M. H. (2012). Training attentional control and working memory—is younger, better? Dev. Rev. 32 (4), 360–387. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2012.07.001

Williams, K. E., and Berthelsen, D. (2017). The development of prosocial behavior in early childhood: contributions of early parenting and self-regulation. Int. J. Early Child. 49 (1), 73–94. doi:10.1007/s13158-017-0185-5

Williams, K. E., Berthelsen, D., Walker, S., and Nicholson, J. M. (2017). A developmental cascade model of behavioral sleep problems and emotional and attentional self-regulation across early childhood. Behav. Sleep Med. 15 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/15402002.2015.1065410

Yan, Z. (2018). How teachers’ beliefs and demographic variables impact on self-regulated learning instruction. Educ. Stud. 44 (5), 564–577. doi:10.1080/03055698.2017.1382331

Youn, M. (2016). Learning more than expected: the influence of teachers’ attitudes on children’s learning outcomes. Early Child. Dev. Care. 186 (4), 578–595. doi:10.1080/03004430.2015.1046856

Zaslow, M., Tout, K., Halle, T., Whittaker, J. V., Lavelle, B., and Trends, C. US Department of Education. Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, US Department of Education (2010). “Toward the identification of features of effective professional development for early childhood educators. Literature review,” in Office of planning, evaluation and policy development. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED527140.pdf.

Keywords: early childhood educator, knowledge, attitudes, self-regulation, self-efficacy, measurement

Citation: Vasseleu E, Neilsen-Hewett C, Ehrich J, Cliff K and Howard SJ (2021) Educator Beliefs Around Supporting Early Self-Regulation: Development and Evaluation of the Self-Regulation Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-Efficacy Scale. Front. Educ. 6:621320. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.621320

Received: 26 October 2020; Accepted: 05 January 2021;

Published: 11 February 2021.

Edited by:

Ghaleb Hamad Alnahdi, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Zi Yan, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong KongLin-Ju Kang, Chang Gung University, Taiwan

José Carlos Núñez, Universidad de Oviedo Mieres, Spain

Copyright © 2021 Vasseleu, Neilsen-Hewett, Ehrich, Cliff and Howard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elena Vasseleu, ZXY5OTNAdW93bWFpbC5lZHUuYXU=

Elena Vasseleu

Elena Vasseleu Cathrine Neilsen-Hewett

Cathrine Neilsen-Hewett John Ehrich

John Ehrich Ken Cliff2

Ken Cliff2 Steven James Howard

Steven James Howard