- 1Temple Infant and Child Lab, Department of Psychology, Temple University, Ambler, PA, United States

- 2Language, Literacy and Learning Lab, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, College of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 3Department of Psychology, Rutgers University-Camden, Camden, NJ, United States

- 4Maternity Care Coalition, Philadelphia, PA, United States

- 5Child’s Play, Learning, and Development Lab, College of Education and Human Development, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States

- 6The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, United States

Spanish-speaking families in the United States must often overcome multiple challenges to support their young children’s early language development (e.g., language and cultural barriers, financial stress, limited learning resources, etc.). These challenges highlight the need for early language interventions tailored to the needs of Spanish-speaking families and developed in collaboration with them. For diverse populations, early language interventions which are both translated into the relevant language and culturally responsive are the most effective for improving child outcomes. However, few interventions meet both criteria, demonstrating a need for materials that are accessible across both language and culture. The current study describes the five-phase process of creating a linguistically and culturally relevant Spanish adaptation of Duet, an early language intervention. The adaptation of the Duet intervention modules involved multiple language experts, including Spanish-speaking developmental psychologists, a translation company, and Spanish-speaking caregivers of infants and toddlers. Fourteen caregivers were recruited to participate in two, 3-h focus groups. Input from caregivers was a particularly important step in the adaptation process, as caregivers hold knowledge about everyday experiences with their children. Through this process, the authors aim to shed light onto the importance of collaborating with the community and present a possible framework for others who are adapting interventions.

Introduction

There is an urgent need to address issues of equity and diversity in research. Part of this process requires including more diverse populations to match the cultural, linguistic, racial, and ethnic heterogeneity in the United States (Roberts et al., 2020). Ethnic minority families adopt culture-specific parenting beliefs and engage in learning activities adapted to their ecological context (Melzi et al., 2019; Sperry et al., 2019). However, their unique strengths are often overlooked in the educational system and early interventions (Janes and Kermani, 2001), which frequently employ a “one-size-fits-all” mindset instead of using a within-group framework to develop family centered culturally responsive interventions that meet community needs (Melzi et al., 2019).

Yet the effective implementation of culturally responsive interventions is a challenge in the current education context. Education researchers strive for a system that values a whole child approach (Diamond, 2010; Darling-Hammond et al., 2020). However, the reality is that the current education system values a set of skills (i.e., language, literacy, math) that are important for children to gain in their own right, but narrowly construed under the pressure of high-stakes assessments (Berliner, 2011). Though specific goals may vary, and parents may have additional culturally specific goals (e.g., “bien educados”- or respectful, well-mannered children)- most parents across SES and cultural backgrounds in the United.States, want their children to do well in school to have better long-term career choices (Zeehandelaar and Winkler, 2013; Valant and Newark, 2017). A preponderance of research further demonstrates that early language skills are the best long-term predictors of later academic success (Bleses et al., 2016; Golinkoff et al., 2019; Pace et al., 2019). While there is much within-group variation, on average, children from under-resourced environments have lower-quality language interactions than their moderate- and higher-resourced peers (Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Golinkoff et al., 2019; Sperry et al., 2019). More specifically, children in Spanish-speaking households are disproportionately more likely to live in under-resourced homes, and thereby experience increased risk to their language development (Child Trends Databank, 2021; National Center for Children in Poverty, 2018) and later academic achievement (Reardon and Galindo, 2009). Thus, making it important for researchers to collaborate with within-group caregivers to determine the best ways to support early language development. The current study was designed to address the need for culturally responsive interventions within the larger educational context. It expands on Duet, a preventative early language intervention for caregivers from under-resourced environments. This study describes the steps taken to adapt Duet, originally available only in English, for use with predominantly Spanish-speaking caregivers.

When children engage in more frequent and higher-quality language interactions with caregivers they demonstrate better long-term academic outcomes (Storch and Whitehurst, 2002; Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Pace et al., 2019). Although many studies focus on English-speaking families (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Masek et al., 2021), high-quality, early language interactions also support the communication skills of children from other cultural and linguistic backgrounds. Studies investigating Spanish-speaking mothers’ use of more complex, elaborative language, found that it promoted children’s narrative skills (Luo et al., 2014; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2014; Hammer and Sawyer, 2016; Escobar et al., 2017). Additionally, more frequent back-and-forth conversations in caregiver–child dyads predicted language development in Spanish-speaking children (Adamson et al., 2021). Despite the importance of early communication experiences across backgrounds, questions remain, including: “How do researchers help caregivers create an environment with rich, high-quality early interactions?” and “How do researchers develop intervention materials that are linguistically and culturally responsive?”

Many caregiver-focused, English-language interventions have been developed in the United States (Roberts and Kaiser, 2011; Greenwood et al., 2020; Heidlage et al., 2020). However, few interventions are responsive to bilingual learners (Cycyk et al., 2020; Durán et al., 2016; Larson et al., 2020). Caregiver-implemented naturalistic communication interventions (CI-NCIs) aim to improve interactions that occur between caregivers and children in daily routines. CI-NCIs have been shown to improve children’s language outcomes (Cycyk et al., 2020; Heidlage et al., 2020; Roberts and Kaiser, 2011). One meta-analysis found that CI-NCIs targeting play and routine interactions improved children’s expressive vocabulary with larger effect sizes than interventions targeting only shared reading (i.e., g = 0.50 vs. g = 0.37) (Heidlage et al., 2020). In a recent review, Larson and colleagues (2020) found that interventions that were linguistically and culturally responsive were most effective at improving children’s language skills. Presenting materials in the participants’ native language rendered them linguistically responsive by demonstrating respect and support for children’s communication skills. Similarly, culturally responsive interventions drew on participants’ values, beliefs, practices, and experiences as resources (Larson et al., 2020). When caregivers deem intervention strategies to be socially important, they are more likely to implement them with their children (Janes and Kermani, 2001; Dunst et al., 2016; Hammer and Sawyer, 2016; Melzi et al., 2019). Examples of successful, strengths-based interventions included using children’s drawings to spark conversations between children and parents (Ceasar and Nelson, 2014) and using food as a central theme for language and literacy activities (Levya and Skorb, 2017). These interventions also sought to support children’s growth towards cultural goals held by caregivers and to maintain their ethnic identities while acquiring language and literacy skills needed for success in school (Melzi et al., 2019). Despite the importance of cultural and linguistic adaptation, few studies meet both criteria (Larson et al., 2020). To date, one study met both criteria and was a CI-NCI. However, it was targeted towards caregivers of preschoolers (Cycyk et al., 2020), demonstrating a need for linguistically and culturally responsive CI-NCIs that seek to support the youngest learners. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to linguistically and culturally adapt a CI-NCI for use with Spanish-speaking caregivers of infants and toddlers.

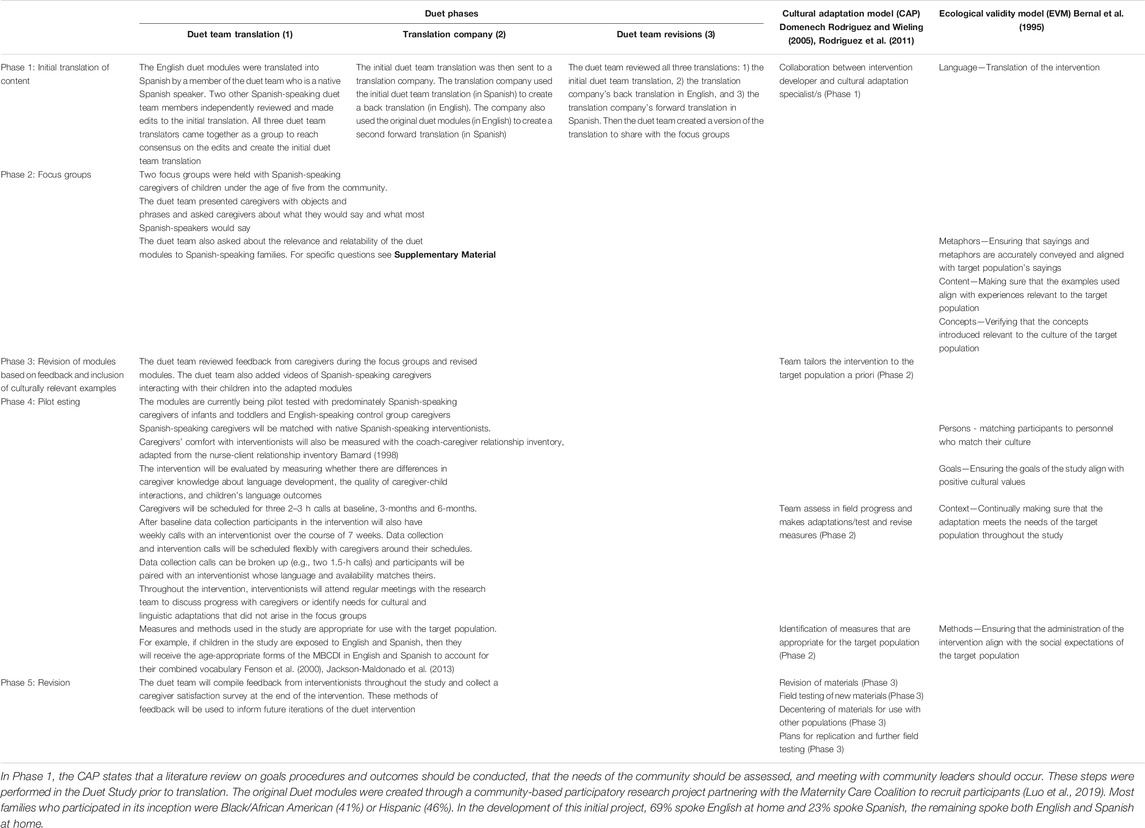

Although there is a clear need for linguistically and culturally responsive early language interventions, there is no set standard for adapting intervention materials. While models exist, guidelines are broad and flexible, resulting in varied levels of adaptation (Bernal et al., 1995; Rodriguez et al., 201l; Sangraula et al., 2020; Stirman et al., 2019). One relevant model is the Cultural Adaptation Process (CAP; Domenech Rodriguez and Wieling, 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2011). CAP has three phases which emphasize stakeholder collaboration, creating and testing an initial cultural adaptation, and revising the adaptation based on feedback. The CAP was intended to be used with the Ecological Validity Model (EVM; Bernal et al., 1995) which contains eight specific areas for consideration when adapting interventions for use with Hispanic families (see Table 1). Both models demonstrate the importance of involving the target population in the development, testing the materials with the target population and the iterative nature of adaptation. The current study sought to create an adapted version of the Duet intervention modules that would be linguistically accurate and culturally responsive across the heterogenous, Spanish-speaking population. Where the other two models included “language” as a step for translation, this study took a deep dive into this aspect of adaptation and aimed to develop modules that would be intelligible across Spanish dialects (e.g., speakers from Puerto Rico, Colombia, etc.). This study discusses the implementation of these general frameworks and specific suggestions for adaptation within each broad category.

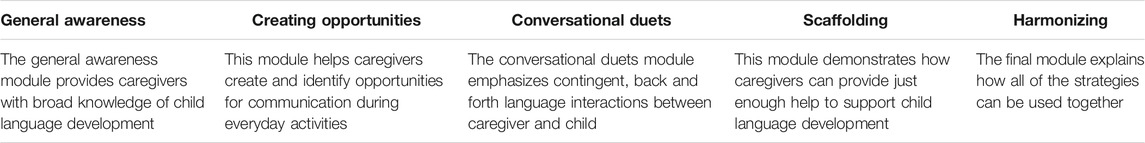

The original Duet modules are a set of early intervention videos created to improve the quality of early caregiver–child language interaction. The modules were created based on developmental science within a community-based participatory research (Shalowitz et al., 2009) framework. Researchers from the Duet team worked with the Maternity Care Coalition (MCC), a local home-visiting program, to identify evidence-based principles of early language interaction, co-construct the Duet goals, and build the modules. Caregivers from the community were also included in this initial step, 23% of whom spoke Spanish predominately (Luo et al., 2019). The modules focus on five key principles: General Awareness, Creating Opportunities, Conversational Duets, Scaffolding, and Harmonizing (see Table 2; Alper et al., under review1; Luo et al., 2019). The six video modules, ranging from 5–30 min each, are narrated by members of a cartoon family (i.e., a mother, father, grandmother, young son, and toddler) who share their own experiences around early language development. This narrative is supplemented by real-life videos of caregivers interacting with their children, to ensure that the modules are representative of the cultural community (Alper et al., under review1; Luo et al., 2019).

The original Duet modules were developed for families in under-resourced households who received home-visiting services in English. Results from the pilot study were promising (Alper et al., under review1; Luo et al., 2019). This study describes 1) the process of adapting the Duet modules for predominantly Spanish-speaking families and 2) specific recommendations for developing culturally responsive intervention materials.

Methods

Five steps were outlined in the creation of an ecologically valid adaptation of the Duet intervention modules, the most important of which drew upon input from the target community. These steps focused on methods aligned with the CAP (Domenech-Rodriguez and Wieling, 2005; Rodriguez et al., 2011) and EVM guidelines (Bernal et al., 1995). See Table 1 for detailed steps. The authors aimed to gain insight into caregivers’ language use with their children and to gauge the cultural relevance of examples in the Duet modules. Merging these models and frameworks, the following five phases were developed in the adaptation of the Duet modules for use with predominantly Spanish-speaking participants: 1) Initial translation of the content 2) Focus group input and feedback 3) Revision of modules based on community feedback 4) Pilot testing 5) Revision.

Phase 1: Initial Translation of Content

The first phase involved direct translation of the Duet modules. This phase was important in making materials accessible to share with the target population (i.e., predominantly Spanish-speaking caregivers) for feedback. To achieve linguistic equivalence, several stakeholders reviewed the translations. The Duet team members involved in the translation process included a postdoctoral developmental psychologist, a graduate student studying developmental psychology, and a coordinator with a Bachelor of Science focusing on health and development. All three team members were fluent in Spanish, one was a native speaker, the other two held bachelor’s degrees in Spanish language and had lived in Spanish-speaking communities. The Duet team members brought a perspective of content knowledge (i.e., early language development). A translation company provided expertise in Spanish language and grammar.

The English modules were first translated into Spanish by the native speaker on the Duet team. The other two Spanish-speaking team members independently reviewed and edited the initial translation. Then, the three Duet team translators came together to make suggestions and edits as a group. Next, these translated modules were sent to a translation company. The translation company created a back translation into English of the Duet team’s Spanish translation. They also used the original English Duet modules to create a second forward Spanish translation.

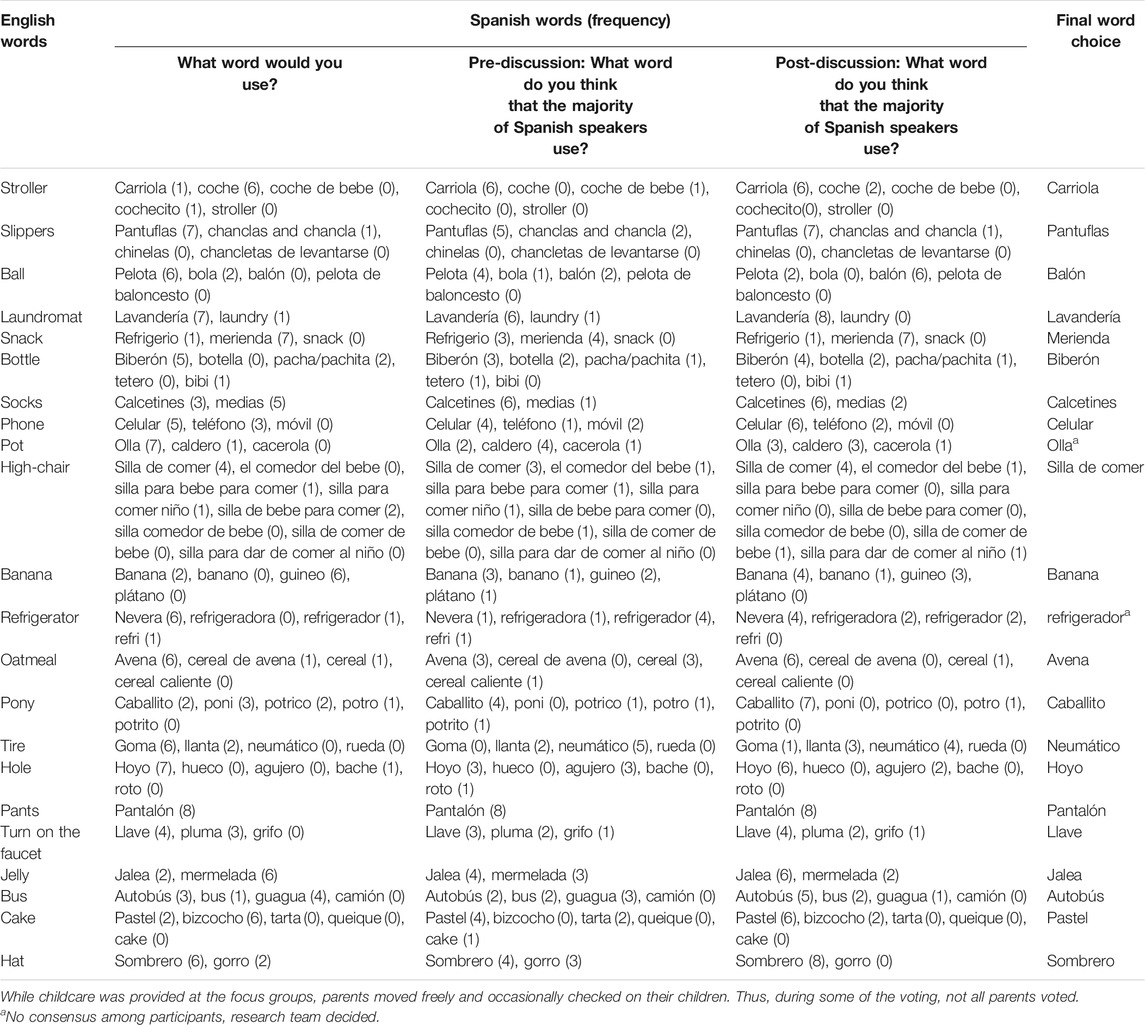

The Duet team jointly reviewed all three versions of the modules, comparing the original English Duet modules to the company’s back translation and the team’s Spanish translation to the company’s forward Spanish translation. If there were differences in translations among the versions, the team selected the translation deemed most intelligible to the majority of Spanish-speakers. During this phase, if there were words or phrases that the team was unable to come to a consensus on, they were flagged to be presented to caregiver focus groups. Likewise, words or phrases that might vary across different Spanish dialects were also catalogued to be presented at focus groups to obtain caregiver feedback. For example, some dialects use “bizcocho” for “cake” while others use “pastel.” Since the Duet team was unable to come to a consensus as to which word was used most widely, the words were flagged to share with caregivers. The next phase in establishing linguistic and cultural equivalence was presenting portions of the updated translation to caregivers in focus groups.

Phase 2: Focus Group Input and Feedback

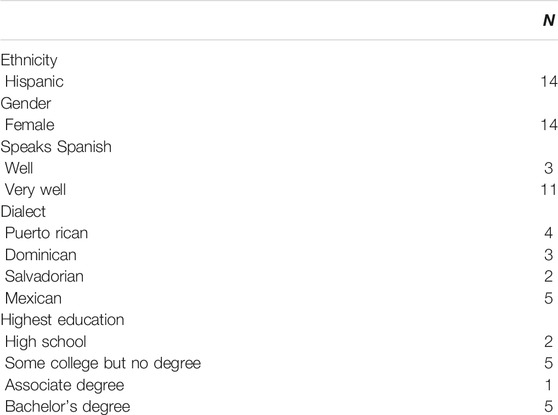

For phase 2, two three-hour-long focus groups were held in the greater Philadelphia area. Focus groups were conducted in Spanish and engaged caregivers interactively with the Duet materials. Caregivers were given questionnaires about their demographic information, language use, and perspectives on early language development. Fourteen Spanish-speaking caregivers were recruited through Duet’s community partner, MCC. The Duet team shared flyers with MCC’s home-visitors who then identified Spanish-speaking clients who had a child between 1 and 5 years of age. All participants identified as female and Hispanic and ranged in age from 25 to 39 years old (M = 30.57, SD = 4.74) (see Table 3 for demographic information). All participants resided in households where the income fell below the 200% federal poverty threshold and all (except one who was pregnant) had at least one child under the age of five. All caregivers had a bachelor’s degree or less. These demographic characteristics were similar to the intended participants for the Duet 2.0 intervention. All participants reported speaking Spanish “well” or “very well.” Most participants reported primarily speaking Spanish at home (n = 11). Research conducted in this study was approved by the Temple University IRB (protocol number: 26195).

First Focus Group

During the first focus group, the Duet team presented pictures of objects and phrases that were flagged in the creation of the final translation draft (e.g., a picture of a cake). The team first asked participants to individually answer, “What word do you use?” and “What word do you think the majority of Spanish-speakers would use?”. Participants were instructed to write down their answers to both questions and turn them in to the researchers. Once answers were turned in, caregivers discussed their responses as a group. This discussion allowed participants to consider other possible words that they may not have generated individually. After the discussion, participants were given an opportunity to change their answer to the second question (i.e., “What word do you think the majority of Spanish-speakers would use?”) on a separate piece of paper.

This format was very engaging, as evidenced by all caregivers actively participating in the discussion. In asking the first question, “What word do you use?”, the team sought to acknowledge each caregiver’s experiences as a native speaker. By asking the second question, the Duet team aimed to both acknowledge each caregiver’s own experiences as members of Spanish-speaking communities and to find consensus on words that were intelligible across dialects.

During this focus group, caregivers were also shown videos from the original Duet modules of parents interacting with their children. These videos occurred across a variety of daily life settings (e.g., toothbrushing, folding clothes, etc.). Caregivers were asked if these settings and interactions were similar to interactions they had with their own children. Parents were also encouraged to share other settings that they thought should be added to the modules.

Second Focus Group

In the second focus group, the Duet team read translations of short caregiver-child interactions that serve as examples in the modules. Caregivers were shown the module slides as Duet team members read a cartoon character’s part. After each example, caregivers were asked, “Does the concept make sense?”. Overall, caregivers reported that the examples from the modules (e.g., interactions during breakfast, in the grocery store, and with books, etc.) were relevant to their daily lives.

Caregivers were asked for feedback about words that young children would use or that a caregiver would use with a young child in Spanish [e.g., “Are the words that Ashley (the cartoon toddler) uses similar to words that your child uses or used at her age?”]. Caregivers who had children between the ages of 12 months and 5 years were specifically recruited to help answer these questions. Responses allowed researchers to determine the appropriateness of the Spanish words used by and with the toddler in the modules. This was important because in some cases, grammatical structures in one language are more difficult to acquire in the other. For example, in English “eat it” is more complex in Spanish “cómetelo” (Domínguez, 2003).

During both focus groups, caregivers were asked to give feedback about words, phrases, and content. The Duet team asked questions like, “Would you say this differently? If so, how?”, “Are there any additional examples you would like us to make or add?” and “Are the Duet modules relevant to your daily life?” Outside of the translations provided, caregivers were encouraged to share any suggestions for translations that would better describe the idea or concept. Caregiver input informed the authors’ word choices and culturally specific examples. For a detailed list of all focus group activities see Supplementary Material.

Phase 3: Revision of Modules Based on Feedback and Inclusion of Culturally Relevant Examples

During phase 3, the Duet team revised the modules by incorporating videos of Spanish-speaking caregivers interacting with their children and the feedback from the focus groups. Within the Duet modules, there are example videos of real caregivers interacting with their children in everyday activities. The team sought to ensure that the adapted modules contained cultural, ethnic, and linguistic content representative of the target audience. Thus, Spanish-speaking, caregiver-child dyads were recruited to film additional real-life interaction videos. Caregivers who wanted to participate in the videos were asked to interact with their children as they normally would. All caregivers who agreed to be filmed spoke in Spanish with their child/ren. Speaking in Spanish was not a requirement for participation; it was the language that caregivers chose to use with their children. Clips from these interaction videos were added to both the English modules (with English subtitles) and to the Spanish modules.

Data Aggregation

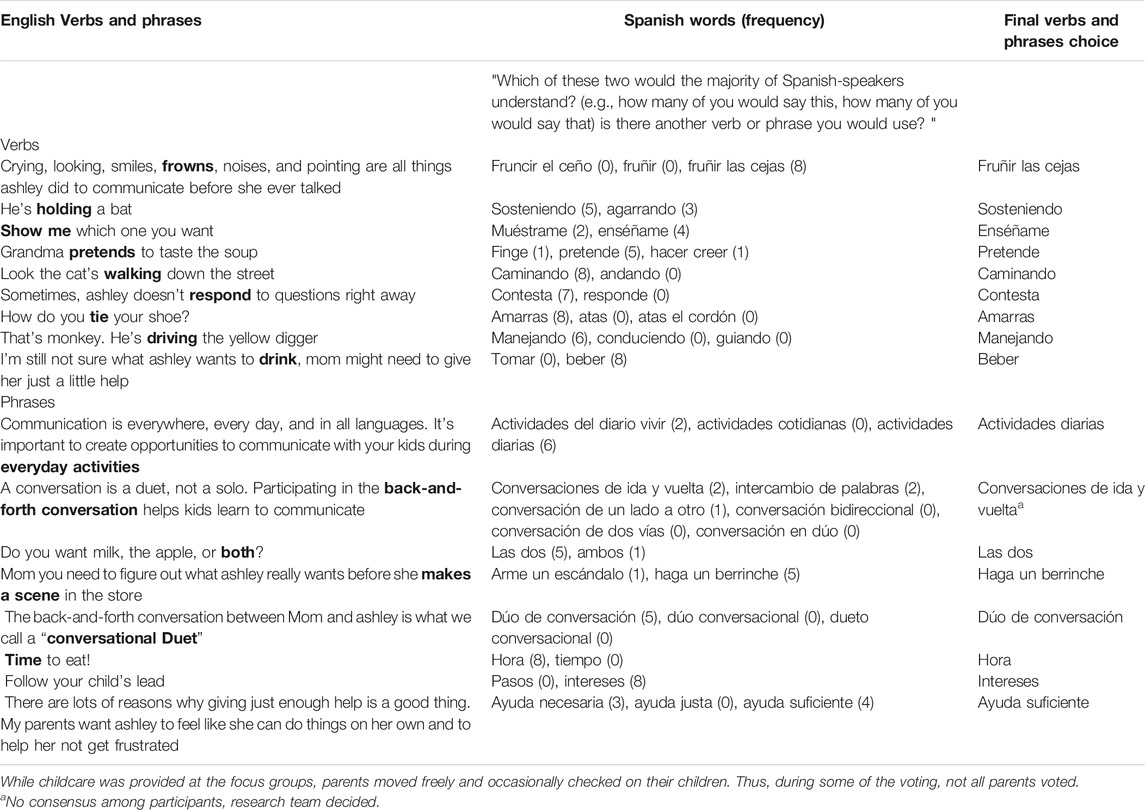

To determine which words to use, the Duet team counted the number of endorsements from the question, “What word do you think the majority of Spanish-speakers would use?” If a word was the most highly endorsed both before and after the discussion, that word was selected for use in the modules (see Tables 4, 5). For example, if participants most frequently wrote the word “balón” for ball before and after the discussion, the word “balón” was used in the modules. If caregivers endorsed different words before and after the discussion, the two most highly endorsed words were discussed among the Duet team members. For example, if before the discussion, caregivers wrote the word “balón” most frequently, but after the discussion wrote “pelota,” Spanish-speaking Duet team members reviewed the focus group recordings and came to a consensus on which word to use based on the discussion between the focus group participants and the research team. Finally, caregiver’s votes from the phrases were tallied and the phrases that were most frequently endorsed were used in the Spanish modules.

Phase 4: Pilot Testing of Modules

The Duet team is currently in the process of phase four, testing whether the English and Spanish versions have similar effects on participants. To do so, English- and Spanish-speaking caregivers are being recruited to participate in the Duet 2.0 intervention, which will deliver the updated English and Spanish modules. Through the intervention, the team aims to improve caregiver knowledge about language development, the quality of caregiver-child interactions, and children’s language outcomes. The intervention will be carried out over seven weeks. Each week, caregivers will watch a Duet module on their own time. After watching the video, caregivers will have a 30 to 60-min call with an assigned language interventionist at the caregiver’s convenience. During the calls, the interventionist will discuss the module with the caregiver and guide them in incorporating the strategies into their daily lives.

This coaching model allows for flexibility in caregivers’ schedules as well as in cultural beliefs and practices. Two of the three interventionists in the study are native Spanish-speakers. Interventionists have been rigorously trained about early language development, including language development for Dual Language Learning children. Trainings will also involve discussions about cultural practices and considerations. Data from the focus groups, namely, caregivers’ perspectives and expectations about early language development, will also be used to inform interventionists’ coaching practices. As the intervention progresses, interventionists will meet biweekly with the research team to share their experiences with coaching families. This community of practice will give interventionists an opportunity to share successes and discuss ways to better address the needs of the families they serve. It will also allow the research team to uncover any need for additional linguistic and cultural adaptations or considerations that were not revealed in the focus groups.

Phase 5: Revision

After the translated modules are implemented in the Duet 2.0 intervention, the authors will determine whether the English and Spanish versions of the modules have similar effects on participants. Although the input from caregivers in the focus group was integral in informing the adaptation of the modules, this is an iterative process. The feedback that is received from Spanish-speaking families after the intervention will be incorporated into future delivery of the Duet intervention modules.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to adapt a CI-NCI for use with predominantly Spanish-speaking families and to create a set of guidelines to aid researchers in the cultural and linguistic adaptation of intervention materials. To that end, the current study describes the progress made towards adapting the early intervention modules using a five-phase model. These five steps include: 1) Initial translation of the content 2) Focus group input and feedback 3) Revision of modules based on community feedback 4) Pilot testing and 5) Revision. While many of the steps replicated previous models (Bernal et al., 1995; Domenech Rodriguez and Wieling, 2005), this study paid particular attention to the linguistic adaption as it was designed to be used across multiple dialects of Spanish.

Like previous studies involving CI-NCI adaptation (e.g., Cycyk et al., 2020), this study involved multiple, iterative steps. During the initial translation and focus group phases, the authors included experts in: 1) the content (i.e., the Duet team members), 2) the Spanish language (i.e., the translation company), and 3) the lived experience of raising Spanish-speaking children (i.e., the focus group caregivers). In phase 3, researchers aggregated the essential information caregivers provided about their experiences with language as Spanish-speakers and their experiences with their own children’s language development. Caregivers’ input informed language choices and the cultural appropriateness of interaction examples. Additionally, naturalistic caregiver-child interactions were included in the final version of the Duet modules to expand the linguistic, ethnic, and cultural diversity.

One strength of using CI-NCI models with culturally and linguistically diverse families, is that they do not aim to change routines or day-to-day activities (e.g., adding dialogic reading). They aim to change the interactions that happen during these routines (Cycyk et al., 2020). This model allows families to continue engaging in activities that they normally do (e.g., cooking dinner, doing chores, etc.) but asks them to consider ways to build upon those interactions. CI-NCIs thus encourage caregivers to continue their usual routines while supporting them in their communication practices.

The ongoing phases reflect the need for testing with the target community and the flexibility needed in the iterative adaptation process. In testing the new modules in their entirety with predominantly Spanish-speaking caregivers, the authors will better understand which aspects of the modules have been successfully adapted and what may need further revision. Through the outlined phases, this paper emphasizes the importance of collaborating with community stakeholders in the adaptation process. In addition, it is important to consider culturally specific goals that caregivers have throughout the adaptation process. This is critical to ensure that children not only meet school system expectations but are also successful members of their own cultural communities (Melzi et al., 2019). As the current project moves forward, it will account for these cultural goals and draw upon family funds of knowledge (Gonzalez et al., 2005). This will be done through interventionist—caregiver calls, where interventionists will discuss culturally based activities that caregivers already engage in and additional objectives that caregivers might have for their children.

Adaptation Challenges

The authors set out to adapt the Duet intervention modules for use with predominantly Spanish-speaking caregivers. However, this population is extremely heterogeneous. Incorporating the diversity across dialects and cultures present in the Spanish-speaking world was one of the main challenges. Although the authors recognize that dialects differ within countries, the team made the choice to define dialects as country (or territory in the case of Puerto Rico) of origin. In doing so, the research team included caregivers from as many Spanish-speaking countries or territories as possible. Caregivers in this study represented four of the five most populous groups of Spanish-speaking countries/territories living within the United States (i.e., Mexican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran, and Dominican, but not Cuban; Noe-Bustamante, 2019). These four groups comprise 79% of reported areas of origin in the United States (Noe-Bustamante, 2019).

Additionally, to limit over-sampling of one dialect, the researchers systematically asked participants to identify the word they themselves would use, and the word they believed most Spanish-speakers would understand. Although the speakers were only from a few countries/territories, they differentiated between words they used and words that a broader group of Spanish-speakers would recognize. This was evidenced by the differences in their responses to the two questions and in the resulting discussion.

Other limitations of this study include a small sample size and that all participating caregivers were mothers. Although a small number of caregivers participated in the focus groups this study plans to enroll more participants in the pilot study. Furthermore, all caregivers in the focus groups were mothers. This is a common limitation across developmental studies which often do not include fathers or other caregivers (Parent et al., 2017). However, while other secondary caregivers may be involved in children’s lives, based on participation in the focus groups it may be that mothers tend to be the primary caregivers in the target population.

Conclusion

The current study used a multi-perspective approach to create an adaptation of an early language intervention that was linguistically and culturally appropriate as well as a blueprint for researchers adapting intervention materials. The Duet team made use of their own expertise in the field of early language development, the translation company’s mastery of the Spanish language, and caregiver’s knowledge and life-experience to create modules that are accessible across multiple dialects of Spanish. While there is evidence that researchers translate materials into Spanish (Larson et al., 2020), there is a need to ensure that these materials are also ecologically valid. Despite this need, there are very few studies which describe the successful incorporation of families’ perspectives into the multifaceted translation process. This study sought to describe successful strategies for incorporating caregivers’ perspectives into an early intervention and to inspire researchers to develop both linguistically and culturally valid materials in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Temple University’s Human Research Protection Program (HRPP). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

BR, RA, JJ, LM, RL, MM, RMG, and KH-P contributed to conception and design of the study. BR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BR, RA, JJ, LM, RL, EB, and KH-P wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was funded by the William Penn Foundation, grant #GR-000031281.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Maternity Care Coalition for their help in reaching out to community members. We would also like to give a special thank you to the caregivers who participated in the focus groups for their insight. Finally, we would like to thank the students and members of the Temple Infant and Child Lab and the Language, Literacy, and Learning Lab for their help in collecting and cleaning the data.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.660166/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1Alper, R. M., Luo, R., Mogul, M., Bakeman, R., Adamson, L., Masek, L., et al. (under Review). The Duet Project: An Exploratory Study of a Parent-Implemented Early Language Intervention for Families in Low-Income Households

References

Adamson, L. B., Caughy, M. O. B., Bakeman, R., Rojas, R., Owen, M. T., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., et al. (2021). The Quality of Mother-Toddler Communication Predicts Language and Early Literacy in Mexican American Children from Low-Income Households. Early Child. Res. Q., 56, 167–179. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.03.006

Barnard, K. E. (1998). Developing, Implementing and Documenting Interventions with Parents and Young Children. Zero to Three 18 (4), 23–29.

Berliner, D. (2011). Rational Responses to High Stakes Testing: The Case of Curriculum Narrowing and the Harm that Follows. Cambridge J. Educ. 41 (3), 287–302. doi:10.1080/0305764x.2011.607151

Bernal, G., Bonilla, J., and Bellido, C. (1995). Ecological Validity and Cultural Sensitivity for Outcome Research: Issues for the Cultural Adaptation and Development of Psychosocial Treatments with Hispanics. J. Abnorm Child. Psychol. 23 (1), 67–82. doi:10.1007/BF01447045

Bleses, D., Makransky, G., Dale, P. S., Højen, A., and Ari, B. A. (2016). Early Productive Vocabulary Predicts Academic Achievement 10 Years Later. Appl. Psycholinguistics 37 (6), 1461–1476. doi:10.1017/s0142716416000060

Caesar, L. G., and Nelson, N. W. (2014). Parental Involvement in Language and Literacy Acquisition: A Bilingual Journaling Approach. Child. Lang. Teach. Ther. 30 (3), 317–336. doi:10.1177/0265659013513028

Child Trends Databank (2019). Dual Language Learners. Retrieved from: https//www.childtrends.org/indicators/dual-language-learners. (Accessed January 25, 2021)

Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., and Osher, D. (2020). Implications for Educational Practice of the Science of Learning and Development. Appl. Develop. Sci. 24 (2), 1–40. doi:10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791

Diamond, A. (2010). The Evidence Base for Improving School Outcomes by Addressing the Whole Child and by Addressing Skills and Attitudes, Not Just Content. Early Educ. Dev. 21 (5), 780–793. doi:10.1080/10409289.2010.514522

Domenech Rodríguez, M. M., Baumann, A. A., and Schwartz, A. L. (2011). Cultural Adaptation of an Evidence Based Intervention: From Theory to Practice in a Latino/a Community Context. Am. J. Community Psychol. 47 (1-2), 170–186. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4

Domenech-Rodriguez, M., and Wieling, E. (2005). “Developing Culturally Appropriate, Evidence- Based Treatments for Interventions with Ethnic Minority Populations,” in Voices Of Color: First-Person Accounts of Ethnic Minority Therapists. Editors M. Rastogi, and E. Wieling (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 313–333.

Domínguez, L. (2003). Interpreting Reference in the Early Acquisition of Spanishclitics. Linguistic Theory and Language Development in Hispanic Languages: Papers from the 5th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium and the 4th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese. Editors S. Montrul, and F. O. Francisco (Somerville, United States:Cascadilla Press), 212–228.

Dunst, C. J., Raab, M., and Hamby, D. W. (2016). Interest-based Everyday Child Language Learning. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología 36 (4), 153–161. doi:10.1016/j.rlfa.2016.07.003

Durán, L. K., Hartzheim, D., Lund, E. M., Simonsmeier, V., and Kohlmeier, T. L. (2016). Bilingual and Home Language Interventions with Young Dual Language Learners: A Research Synthesis. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 47 (4), 347–371. doi:10.1044/2016_LSHSS-15-0030

Escobar, K., Melzi, G., and Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2017). Mother and Child Narrative Elaborations during Booksharing in Low-Income Mexican-American Dyads. Inf. Child. Dev. 26 (6), e2029. doi:10.1002/icd.2029

Fenson, L., Pethick., S., Renda, C., Cox, J. L., Dale, P. S., and Reznick, J. S. (2000). Short-form Versions of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories. Appl. Psycholinguistics 21, 95–116. doi:10.1017/s0142716400001053

Golinkoff, R. M., Hoff, E., Rowe, M. L., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Language Matters: Denying the Existence of the 30-million-word gap Has Serious Consequences. Child. Dev. 90 (3), 985–992. doi:10.1111/cdev.13128

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L., and Amanti, C. (2005). Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices Inhouseholds, Communities, and Classrooms. New York: Routledge.

Greenwood, C. R., Schnitz, A. G., Carta, J. J., Wallisch, A., and Irvin, D. W. (2020). A Systematic Review of Language Intervention Research with Low-Income Families: A Word gap Prevention Perspective. Early Child. Res. Q. 50, 230–245. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.04.001

Hammer, C. S., and Sawyer, B. (2016). Effects of a Culturally Responsive Interactive Book-reading Intervention on the Language Abilities of Preschool Dual Language Learners: A Pilot Study. NHSA Dialog 19 (2) .

Heidlage, J. K., Cunningham, J. E., Kaiser, A. P., Trivette, C. M., Barton, E. E., Frey, J. R., et al. (2020). The Effects of Parent-Implemented Language Interventions on Child Linguistic Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Early Child. Res. Q. 50, 6–23. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.006

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Adamson, L. B., Bakeman, R., Owen, M. T., Golinkoff, R. M., Pace, A., et al. (2015). The Contribution of Early Communication Quality to Low-Income Children's Language Success. Psychol. Sci. 26 (7), 1071–1083. doi:10.1177/0956797615581493

Huttenlocher, J., Waterfall, H., Vasilyeva, M., Vevea, J., and Hedges, L. V. (2010). Sources of Variability in Children's Language Growth. Cogn. Psychol. 61 (4), 343–365. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2010.08.002

Jackson-Maldonado, D., Marchman, V. A., and Fernald, L. C. H. (2013). Short-form Versions of the Spanish MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories. Appl. Psycholinguistics 34 (4), 837–868. doi:10.1017/s0142716412000045

Janes, H., and Kermani, H. (2001). Caregivers' story reading to Young Children in Family Literacyprograms: Pleasure or Punishment? J. Adolesc. Adult Literacy 44 (5), 458–466.

Larson, A. L., Cycyk, L. M., Carta, J. J., Hammer, C. S., Baralt, M., Uchikoshi, Y., et al. (2020). A Systematic Review of Language-Focused Interventions for Young Children from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds. Early Child. Res. Q. 50, 157–178. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.06.001

Leyva, D., and Skorb, L. (2017). Food for Thought: Family Food Routines and Literacy in Latino Kindergarteners. J. Appl. Develop. Psychol. 52, 80–90. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2017.07.001

Luo, R., Alper, R. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Mogul, M., Chen, Y., Masek, L. R., et al. (2019). Community-Based, Caregiver-Implemented Early Language Intervention in High-Risk Families: Lessons Learned. Prog. Community Health Partnersh 13 (3), 283–291. doi:10.1353/cpr.2019.0056

Luo, R., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Kuchirko, Y., F. Ng, F., and Liang, E. (2014). Mother-Child Book-Sharing and Children's Storytelling Skills in Ethnically Diverse, Low-Income Families. Inf. Child. Dev. 23 (4), 402–425. doi:10.1002/icd.1841

Masek, L. R., Paterson, S. J., Golinkoff, R. M., Bakeman, R., Adamson, L. B., Owen, M. T., et al. (2021). Beyond Talk: Contributions of Quantity and Quality of Communication to Language success across Socioeconomic Strata. Infancy 26 (1), 123–147. doi:10.1111/infa.12378

Melzi, G., Schick, A. R., and Scarola, L. (2019). “Literacy Interventions that Promote home-to-schoollinks for Ethnoculturally Diverse Families of Young Children,” in Ethnocultural Diversity and the Home-to-School Link. Editors C. M. McWayne, F. Doucet, and S. M. Sheridan (Cham: Springer), 123–143. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-14957-4_8,

National Center for Children in Poverty (2018). United States Demographics of Poor Children. Available at: http://www.nccp.org/profiles/US_profile_7.html (Accessed January 3, 2021).

Noe-Bustamante, L. (2019). Key Facts about UNITED STATES Hispanics and Their Diverse Heritage. PewResearch Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/16/key-facts-about-u-s-hispanics/ (Accessed November 19, 2020).

Pace, A., Alper, R., Burchinal, M. R., Golinkoff, R. M., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2019). Measuring success: Within and Cross-Domain Predictors of Academic and Social Trajectories in Elementary School. Early Child. Res. Q. 46, 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.001

Parent, J., Forehand, R., Pomerantz, H., Peisch, V., Seehuus, M., Reardon, S. F., et al. (2017). Father Participation in Child Psychopathology researchThe Hispanic-White Achievement gap in Math and reading in the Elementary Grades. J. Abnorm Child. Psycholamerican Educ. Res. J. 4546 (73), 1259853–1270891. doi:10.1007/s10802-016-0254-5

Reardon, S. F., and Galindo, C. (2009). The Hispanic-White achievement gap in math and reading in the elementary grades. American Education Research Journal, 46(3), 853–891.doi:10.1007/s10802-016-0254-5

Roberts, M. Y., and Kaiser, A. P. (2011). The Effectiveness of Parent-Implemented Language Interventions: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Speech-Language Pathol. 20, 180. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055)

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., and Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial Inequality in Psychological Research: Trends of the Past and Recommendations for the Future. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 15, 1295–1309. doi:10.1177/1745691620927709

Sangraula, M., Kohrt, B. A., Ghimire, R., Shrestha, P., Luitel, N. P., Van't Hof, E., et al. (2020). Development of a Systematic Framework for Cultural Adaptation and Contextualization of Evidence-Based Psychological Interventions. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-40265/v1

Shalowitz, M. U., Isacco, A., Barquin, N., Clark-Kauffman, E., Delger, P., Nelson, D., et al. (2009). Community-based Participatory Research: a Review of the Literature with Strategies for Community Engagement. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 30 (4), 350–361. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b0ef14

Sperry, D. E., Sperry, L. L., and Miller, P. J. (2019). Reexamining the Verbal Environments of Children from Different Socioeconomic Backgrounds. Child. Dev. 90 (4), 1303–1318. doi:10.1111/cdev.13072

Storch, S. A., and Whitehurst, G. J. (2002). Oral Language and Code-Related Precursors to reading: Evidence from a Longitudinal Structural Model. Dev. Psychol. 38 (6), 934–947. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.6.934

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Song, L., Luo, R., Kuchirko, Y., Kahana-Kalman, R., Yoshikawa, H., et al. (2014). Children's Vocabulary Growth in English and Spanish across Early Development and Associations with School Readiness Skills. Develop. Neuropsychol. 39 (2), 69–87. doi:10.1080/87565641.2013.827198

Valant, J., and Newark, D. (2017). My Kids, Your Kids, Our Kids: What Parents and the Public Want from Schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. 119 (11), 1–34 .

Wiltsey Stirman, S., Baumann, A. A., and Miller, C. J. (2019). The FRAME: an Expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-Based Interventions. Implement Sci. 14 (1), 58–10. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y

Zeehandelaar, D., and Winkler, A. M. (2013). “What Parents Want: Education Preferences and Trade- Offs,” in A National Survey of K-12 Parents. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED598700.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2020)

Keywords: language intervention, linguistically and culturally diverse, cultural adaptation, community based participatory reaserch, bilingual language acquisition

Citation: Rumper BM, Alper RM, Jaen JC, Masek LR, Luo R, Blinkoff E, Mogul M, Golinkoff RM and Hirsh-Pasek K (2021) Beyond Translation: Caregiver Collaboration in Adapting an Early Language Intervention. Front. Educ. 6:660166. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.660166

Received: 28 January 2021; Accepted: 02 June 2021;

Published: 17 June 2021.

Edited by:

Priya Shimpi, Mills College, United StatesReviewed by:

Simona De Stasio, Libera Università Maria SS. Assunta, ItalyShakila Dada, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Copyright © 2021 Rumper, Alper, Jaen, Masek, Luo, Blinkoff, Mogul, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brooke M. Rumper, YnJvb2tlLnJ1bXBlckB0ZW1wbGUuZWR1

Brooke M. Rumper

Brooke M. Rumper Rebecca M. Alper2

Rebecca M. Alper2 Rufan Luo

Rufan Luo Elias Blinkoff

Elias Blinkoff Roberta Michnick Golinkoff

Roberta Michnick Golinkoff Kathy Hirsh-Pasek

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek