- 1Faculty of English, Zhejiang Yuexiu University, Shaoxing, China

- 2Faculty of Education, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 3Population Studies Unit, Faculty of Business and Economics, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

This research explores the influence of the psychological capital of elementary English as a second language (ESL) teachers in Malaysia on their classroom management and the moderation effect of their working experience on the influential relationship between psychological capital and ESL classroom management. A survey conducted with 675 Malaysian elementary teachers took part in this research, with 24 teachers identified by followed up interviewing. From quantitative and qualitative analyses, the results show that psychological capital of elementary ESL teachers has a significant positive influence on classroom management. Teaching experience demonstrates a significant moderation effect in the casual correlation of psychological capital to ESL classroom management. The influence of the psychological capital of novice teachers on their classroom management is better than experienced teachers. Some implications and limitations are put forward.

Introduction

Recent research into classroom management in foreign language teaching is sparse (Wright, 2005; Macías, 2018). Difficulty in establishing and maintaining effective foreign language classroom management is a primary reason for teachers experiencing a reduced commitment to their work, mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and burnout (Berger et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2021). A teacher who displays these mental conditions will negatively affect the learning environment, and it is important to find effective methods of reducing the stresses that teachers are subject to. There is a considerable body of research from a linguistic perspective on teaching ESL (English as a second language), but it includes little examination of the value of the teacher having a positive psychological attitude (Gabryś-Barker and Gałajda, 2016; MacIntyre et al., 2019). The concept of psychological capital (PsyCap) is a basis for developing practical techniques for protecting an individual from stress, negative emotions, and burnout (Liu et al., 2012).

Psychological capital is derived from research into positive psychology and positive organizational behavior. It has been defined as the “positive appraisal of circumstance and probability for success based on motivated effort, and perseverance” (Luthans et al., 2007, p. 550). PsyCap integrates four positive psychological dimensions as variables that form criteria for identifying an individual’s psychological capital: hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism. PsyCap has been shown to influence individual stress management and coping mechanisms and to enable an individual to overcome difficulties and so enjoy a productive life (Avey et al., 2010; Newman et al., 2014; Luthans and Youssef-Morgan, 2017; Adil and Kamal, 2020; Rabenu and Tziner, 2020).

Psychological capital was developed in the context of business management (Luthans and Youssef-Morgan, 2017), but little is known of its effectiveness in an educational context or of any benefits, it may confer in terms of educational outcomes, especially in non-Western educational contexts (Luthans et al., 2006; Datu and Valdez, 2019). Malaysia is considered a collectivist society, and the exploitation of PsyCap is still in its infancy in ESL teaching (Burhanuddin and Ahmad, 2018). The results of this study could provide some evidence on the adaptive role of PsyCap in non-Western socio-cultural society and academic context.

Both training and field experience are required to acquire skills in classroom management (Bosh, 2006). Empirical organizational behavior studies have shown that demographic differences such as age, sex, work experience, and education affect outcome variables (Tsui et al., 1992; Tsui and Gutek, 1999). However, there is an unclear and inconsistent conclusion that teaching experience affects ESL classrooms (Berger et al., 2018; Wolff, 2021). Research focusing on PsyCap in Malaysia is still new, with little evidence highlighting results from this real relationship in education context.

The purpose of the current study was to provide knowledge about teachers’ teaching experiences on the relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management using mixed methods based on job demands-resources theory (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017). A better understanding of the relationship between PsyCap and classroom management will enable Malaysian teachers to improve the provision of positive education (Seligman et al., 2009). Positive psychology (Seligman, 2002) promotes ESL teachers’ inner strengths and helps them thrive in their workplace. This study will clarify how teachers create quality educational environments and thus inform both policy and practice in teacher education.

Literature Review

To theoretically contextualize this research, we draw on the job-demands resource model (JD-R) suggested by Luthans et al. (2016). The JD-R model proposes that job strain is caused by high job demands (such as organizational, social, psychological, and physical) and low resources. The model consists of two processes (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007). The first part is the demand chain, where constant demands wear down employees’ mental and physical health over time and have an impact on motivation, energy levels and burnout (Demerouti et al., 2001). The second part is the resource part of the model, which has the motivational potential to buffer the impact of job demands and the associated undesirable physical and psychological costs. The resources can be split into external (organizational or job) and internal (personal or cognitive) factors (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017). Personal psychological resources are considered to be particularly effective in increasing engagement and improving job performance (Demerouti et al., 2001; Bakker et al., 2003). Accordingly, we propose that ESL teachers with dual needs seek to maintain their resources to improve classroom management and personal well-being. In addition, Luthans et al. (2016) demonstrated the influence of psychological resources in guiding ESL teachers’ classroom management in the form of PsyCap, which provided the basis for this study. More specifically, we looked to examine the relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management to establish whether the findings of Luthans and colleagues extend to Malaysian ESL teachers, as to the researchers’ knowledge, no previous study has been conducted with this sample. In addition, due to the nature and characteristics of ESL teachers, we examine whether the teaching experience acts as a moderating buffer on this relationship.

Psychological Capital and English as a Second Language Classroom Management

Psychological capital has been used to predict employee work performance, attitude, and behavior (Avey et al., 2011). Despite the potential benefits of PsyCap in the organization, little is known about the beneficial effects of PsyCap on positive foreign language educational field and in non-Western academic contexts (Datu and Valdez, 2019). Elementary ESL teachers have rarely been included in studies of PsyCap, and existing literature has shown that the psychological benefits of PsyCap in the general education field. For example, empirical research has shown that teachers with increased PsyCap display more positive work attitudes and improved performance, characteristics that are instantiated by better classroom management (Fu, 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2017), although most of these studies involved teachers from Taiwan.

Some characteristics make the foreign language class different from the general classroom management. Effective foreign language classroom management needs teachers to use the foreign language to teach instructions and methods by creating communication contexts and maximizing student involvement (Borg, 2006). Hence, language, instructional, and behavior management are three of the most important characteristics (Borg, 2006; Akbari and Bolouri, 2015; Katz, 2017). However, few investigations highlight the benefits of PsyCap in foreign language classroom management.

Luthans et al. (2010) demonstrated that the four variables of PsyCap, singly or in combination, were significant predictors of employee work performance (Luthans et al., 2007). Therefore, we decided to use the four variables of psychological capital to indicate the effectiveness of foreign language classroom management. Hope is an attitude of mind or a way of thinking that governs how an individual performs their job (Snyder, 1994). Snyder’s (1994) cognitive model of hope indicated that teachers with high hope tend to perceive themselves as effective problem-solvers who develop multiple strategies to achieve their goals in classroom management. This claim was supported by Kumarakulasingam (2002), who found that foreign language teachers with a high level of hope were associated with low burnout and highly effective class management.

Efficacy is an individual’s perception of and belief in their abilities (Bandura, 1977). Bandura’s social cognition theory includes the view that teacher efficacy positively affects work performance in the classroom. Moafian and Ghanizadeh (2009) found that foreign language teacher efficacy was positively correlated with effective practical instruction and positive classroom management, as did Delale-O’Connor et al. (2017) and Poulou et al. (2019). Similar findings were made for teachers in other countries, such as Venezuela (Chacon, 2005), Australia (Ma and Cavanagh, 2018), and Turkey (Tilfarlioglu and Ulusoy, 2012).

Resilience is the ability to remain positive and bounce back from adversity (Tugade and Fredrickson, 2002). Teacher resilience is a relatively new field of research (Goddard and Foster, 2011). Ergün and Dewaele (2021) found that a resilient teacher can handle power, fulfill teaching goals, and take great enjoyment in the classroom by investigating 174 Italian foreign language teachers. Stavraki and Karagianni (2020), in a quantitative study of 169 Greek English teachers found that teacher resilience was significantly correlated with effective classroom management and class characteristics. Boldrini et al. (2018) interviewed 37 vocational teachers in Switzerland and found that resilience affected their stress and work performance and that they could increase their capacity for resilience through resilient strategies.

Optimism is the expectation of a positive outcome of an act or situation; it is thus an attitude, not an ability (Scheier and Carver, 1985). Hoy et al. (2008) established a relationship between teachers’ humanistic classroom behaviors, student-centered teaching, citizenship activity, and optimism. Moghtadaie and Hoveida (2015) investigated 384 teachers in Iran found a significant correlation between teacher optimism and classroom management. Ronald (2016) conducted mixed-method research in Puerto Rico and found that teacher optimism positively influenced both student behavior and classroom management. This result was supported by the work of Jin and Dewaele (2018), who found that foreign language teachers’ optimism reduced foreign language student anxiety in the classroom. In summary, it is clear that the construct PsyCap can improve foreign language classroom management.

Moderating the Effects of Psychological Capital on English as a Second Language Classroom Management

Teacher experience is a key factor in classroom management (Berger et al., 2018) and is a primary concern for both newly trained and experienced teachers (Weinstein, 1996; Stoughton, 2007). However, some studies have found that classroom management poses difficulties only for novice teachers and that experienced teachers can handle complex classroom situations well (Hagger and McIntyre, 2000; Wolff et al., 2014). It is hard to determine if teaching experience affects classroom management in ESL teaching due to unclear and inconsistent results.

There has been little research into adjustment variables related to psychological capital. However, Wiersema and Bantel (1992) suggest that teaching experience might be a factor that moderates the effects of PsyCap on classroom management. Lee et al. (2017) surveyed 400 preschool teachers in Taiwan. They found that years of teaching experience acted as a moderating factor in the critical relationship between PsyCap and teacher commitment to their profession. Wang et al. (2014) found that as teaching experience increased over time, elementary teachers in Taiwan possessed more PsyCap. Mesurado and Laudadío (2019) found that among university teachers in Argentina, more experienced teachers had higher levels of PsyCap and higher levels of teaching engagement than less experienced teachers. There is little literature concerning teaching experience as a moderating factor in the relationship between teacher PsyCap and ESL classroom management. The quantitative finding of Gkonou and Mercer (2017) revealed the variety of past classroom experiences to interpret and respond to current classroom events. Varied teaching experience could shape English teachers’ emotions and decisions in class.

Hypotheses

Our study was designed to test the following hypotheses:

H1: There is a significant relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management.

H2: Teaching experience moderates the relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management.

Materials and Methods

Research Framework

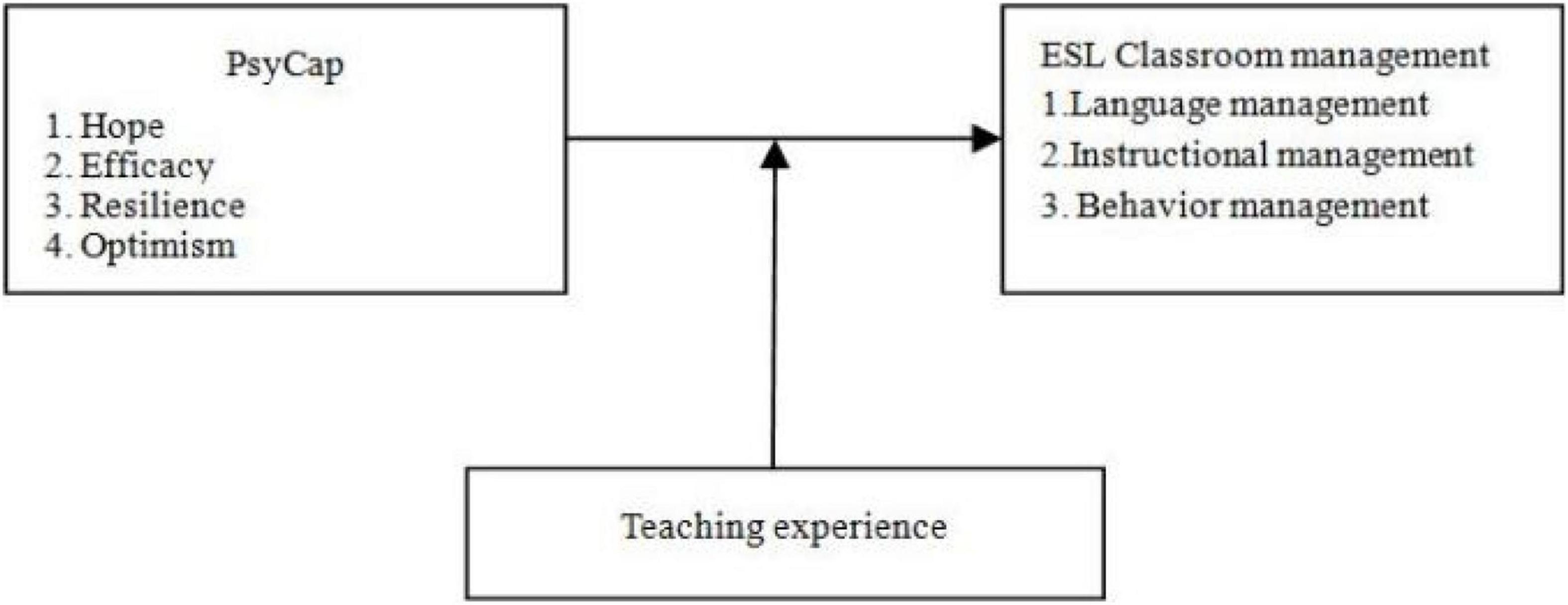

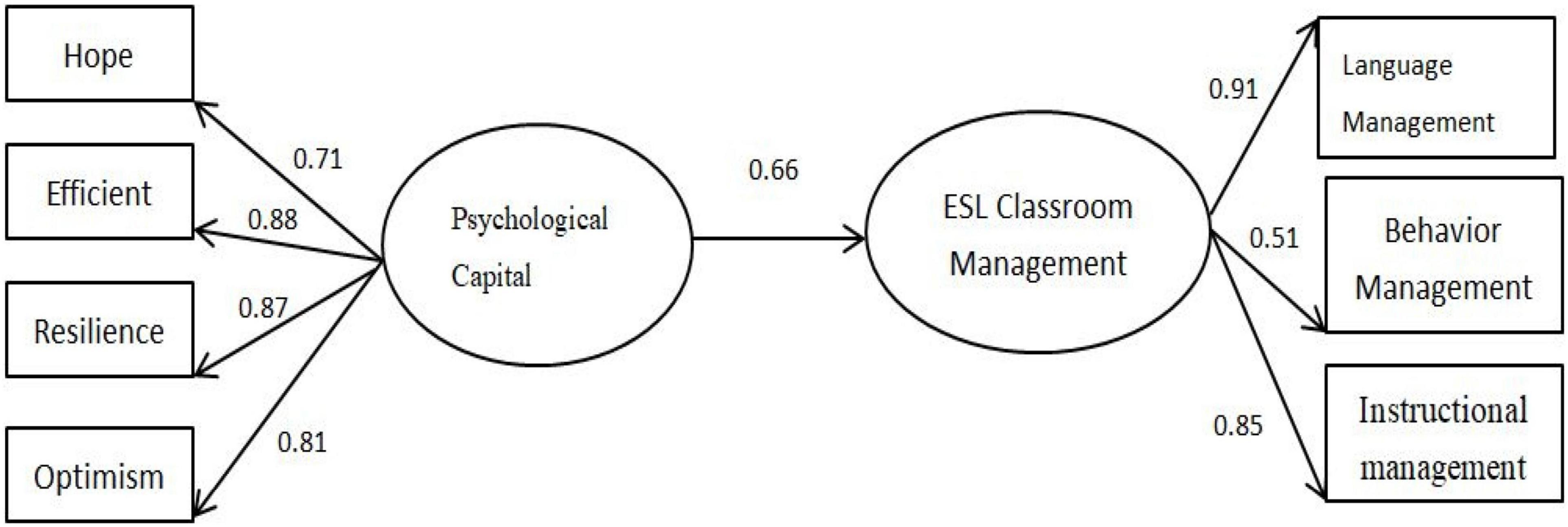

The conceptual framework of our research is shown in Figure 1. We investigated the influence of PsyCap on ESL classroom management and examined the effect of teaching experience on the relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management.

Participants and Procedure

Data were collected in Bahasa Melayu from a sample of ESL teachers in elementary schools in Malaysia in a cross-sectional survey using an online questionnaire. The use of a conventional survey method was not feasible due to the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak (Pressley, 2021), so Google survey was used to rapidly collect responses from an extensive and diverse sample, as it was easy for both participants and researchers to use and was more flexible and accurate than other alternatives (Ali et al., 2020). The language of this survey was kept simple, specific and conscious; and back translation was conducted. A pilot study among 56 elementary ESL teachers involved, and the validity of the research instruments was verified (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The online survey remained open from 2021-04-27 to 2021-05-27 and provided both quantitative and qualitative data. All respondents were informed of ethical issues by short, succinct online messages. The confidentiality of each participant and their responses were assured, and our intention to publish subsequent findings from the data was made clear.

In total, 675 usable questionnaires were received from 27 elementary schools in nine different states in Malaysia. Participants were categorized by age: <30 years (n = 224, 33.2%), 30–40 years (n = 209, 31.0%), 41–50 years (n = 179, 26.5%) and >50 years (n = 63, 9.3%); by sex: male (n = 254, 37.63%) and female (n = 421, 62.37%); and by years of teaching experience: ≥5 years (n = 359, 53.19%) and <5 years (n = 316, 46.81%).

Semi-structural individual interviews were subsequently conducted with 24 teachers (12 females and 12 males) from 6 schools in Kuala Lumpur. Twenty-four teachers were interviewed from six schools, ranging in age from 24 to 58 years (12 novice teachers and 12 experienced teachers). The interviews were conducted in Bahasa Melayu to express ideas accurately via Zoom. Each interview lasted for 10–15 minutes and was recorded with participants’ permission.

Measurements

Psychological Capital

The PsyCap of the subjects was measured using the 24 items of the PCQ-24 scale developed by Luthans et al. (2007). Each of the four dimensions (hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism) was measured using six items with a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The PCQ-24 instrument is widely used and has been well validated (Luthans and Youssef-Morgan, 2017; Datu and Valdez, 2019).

English as a Second Language Classroom Management

The 22-item ELT-CMS instrument (Akbari and Bolouri, 2015) was used to quantify classroom management skills. The instrument uses a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) for responses; it measures three dimensions: language (5 items), instructional technique (12 items), and behavior management (5 items). Previous studies have demonstrated the validity and reliability of this instrument (Akbari and Bolouri, 2015; Tasci and Atar, 2016).

Qualitative Items

Interview subjects were asked two qualitative questions: (1) How does PsyCap (hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism) affect your classroom management? and (2) How does your teaching experience affect your PsyCap and classroom management?

Analysis

Quantitative Data

SPSS 23.0 and AMOS 21.0 were used for statistical analysis of the quantitative data. Data were screened and checked for missing data, outliers, multicollinearity, and normality. Mean and standard deviations were used for descriptive analysis. The Pearson r correlation coefficient was used to indicate the strength of the relationship between each dimension of PsyCap and ESL classroom management.

Structural equation models (SEM) were used to test the two hypotheses following the two-step approach Awang (2014) suggested. The first step used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to establish confidence in each measurement model. The second step used SEM to quantify the effect of teaching experience in moderating the relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management. Multi-group analysis to test for the effect of teaching experience was conducted in two steps. The data were partitioned into two groups, experienced teachers and novice teachers. The path of interest was selected for each group to test for differing effects. If the difference in chi-square values between the constrained model and the unconstrained model for each path was >3.84, then there was a moderating effect in the path (Awang, 2014). The structural model was tested using AMOS 21.0. The following statistics were used to indicate the overall fit of the model to the data: χ2/df (≤5.0), p < 0.05, root mean square error of the approximation (RMSEA) (≤0.08), comparative fit index (CFI) (≥0.90), the normed fit index (NFI) (≥0.90) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI) (≥0.90).

Qualitative Data

A thematic analysis approach was adopted for the qualitative analysis (Coleman and Unrau, 2008). It consisted of five steps: (1) transcription, (2) reliability analysis, (3) coding, (4) establishing themes and categories, and (5) writing up and interpreting the results. An inductive data analysis approach (Mackey and Gass, 2005) was used to generate categories, themes, and patterns. The data analysis program Dedoose was used for coding (version 6.1.11)1.

Inter-rater agreement tests of 10% of all verbal data were created using Dedoose (version 6.1.11) to verify the reliability and face validity of the coded data based on the degree of agreement and consistency between two independent coders. Pooled Cohen’s kappa was used to indicate reliability across all coding categories (DeVries et al., 2008). The average of pooled Cohen’s kappa was 0.89. Values for individual tests were in the range of 0.85–0.91, indicating excellent consistency between the two raters (Viera and Garrett, 2005).

Results

Quantitative Findings

Preliminary Analysis

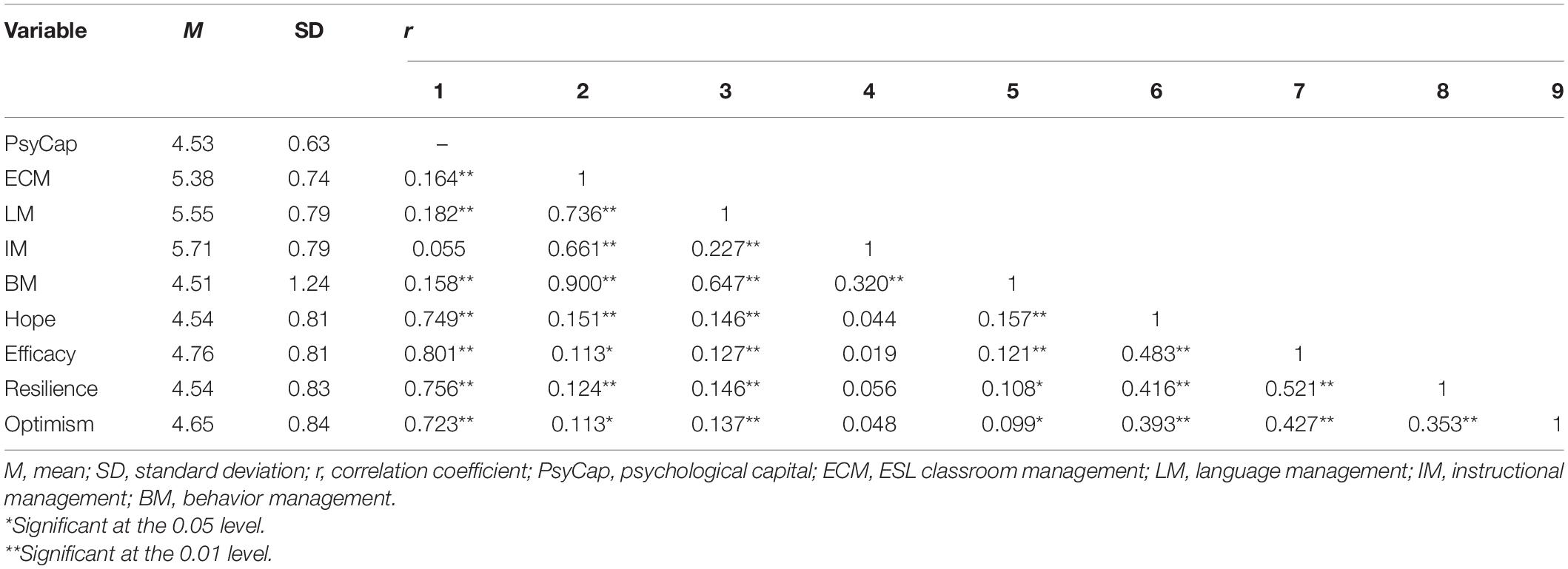

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the responses of ESL teachers to the survey questions (n = 675). Pearson correlation coefficients between the variables are also shown. All correlations were significant but at different levels.

Validity and Reliability

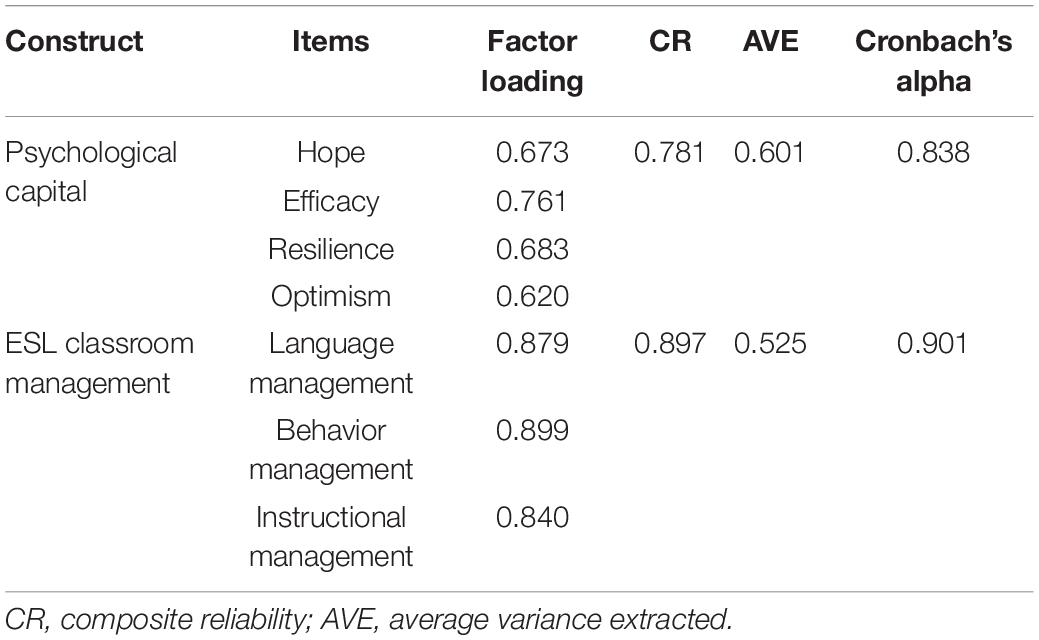

The measurement model was tested for validity and reliability (Table 2). When the constructs of the SEM model have average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) values above their cut-off points (0.5 and 0.7), the construct has convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). CR ranged in value from 0.781 to 0.897, above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al., 2010). AVE and discriminant validity were tested to quantify the construct validity of the measurements (Hair et al., 2014). AVE ranged in value from 0.525 to 0.601, satisfying the criteria for convergent validity given in Cheung and Wang (2017): convergent validity is acceptable if neither AVE nor the standardized factor loadings of all items are significantly <0.50.

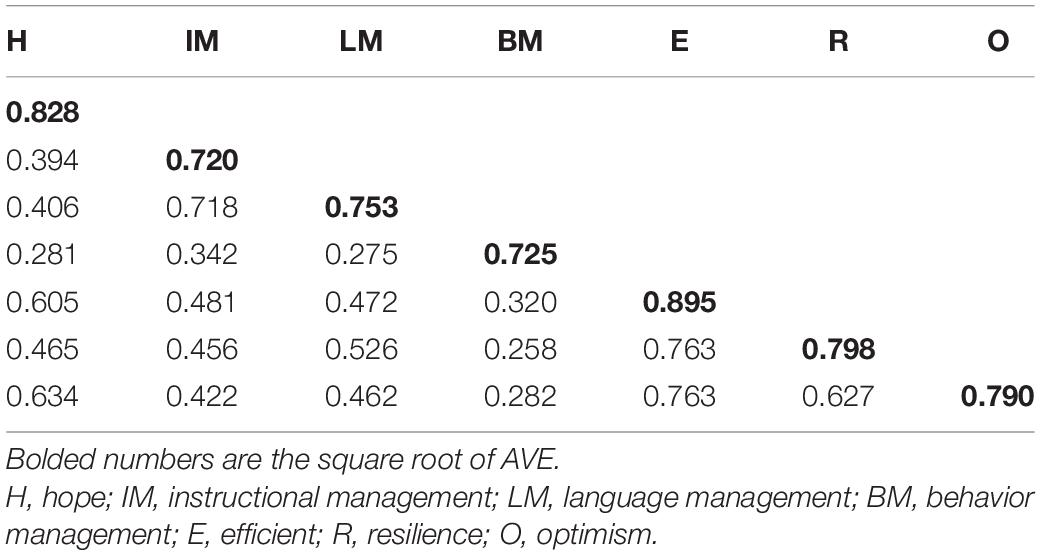

The square root of AVE for each construct was calculated to determine discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Table 3 shows that the square root of AVE (on the diagonal) for each construct was greater than the correlations between it and all other constructs in the model.

Relationship Between Psychological Capital and English as a Second Language Classroom Management

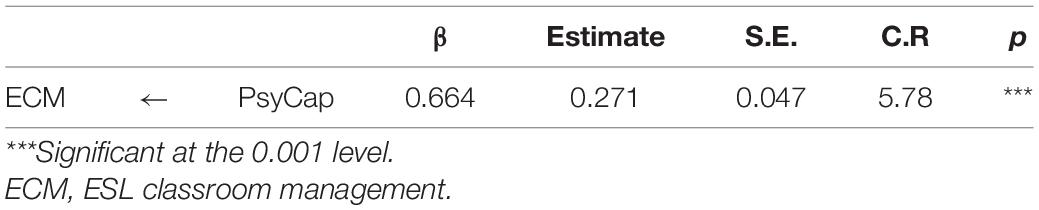

The basic model (Figure 1) was created to determine the influence of PsyCap on ESL classroom management. The SEM model was tested using the maximum-likelihood estimation in Amos 21.0. Figure 2 shows there was a good fit of the model to the data: χ2/(979) = 1.956, p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.045, CFI = 0.936, and GFI = 0.901.

Table 4 shows that PsyCap had a significant positive direct effect on ESL classroom management (β = 0.664,p < 0.001). PsyCap accounted for 44% of the variance in ESL classroom management. The remaining 56% of the variance was unpredictable (R2 = 0.44).

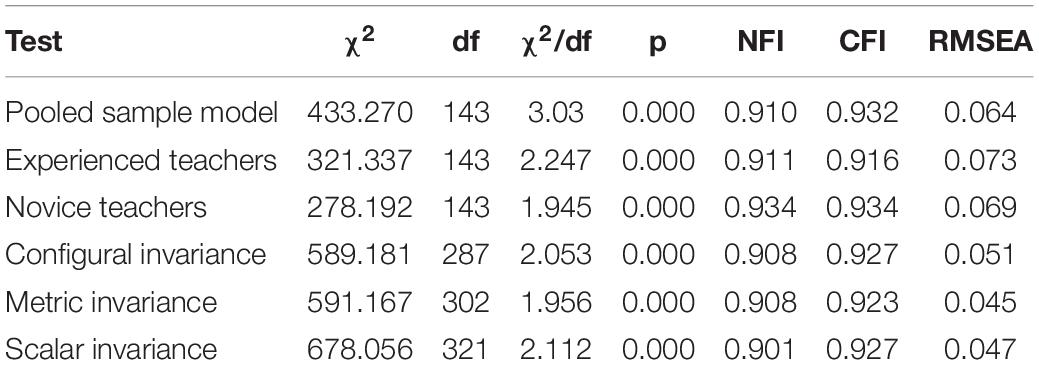

Moderating Effect of Teacher Experience

Hicks (2012) separated experienced teachers from novice teachers by the number of years they had been teaching: novice teachers <5 years classroom management and experienced teachers ≥5 years. We adopted this categorization. Measurement invariance analysis was conducted on six models (Table 5): a pooled sample model, a model for experienced teachers, a model for novice teachers, and models for each configurational invariance, metric invariance, and scalar invariance. The analysis showed acceptable goodness-of-fit for the pooled sample, experienced teachers, and novice teachers models.

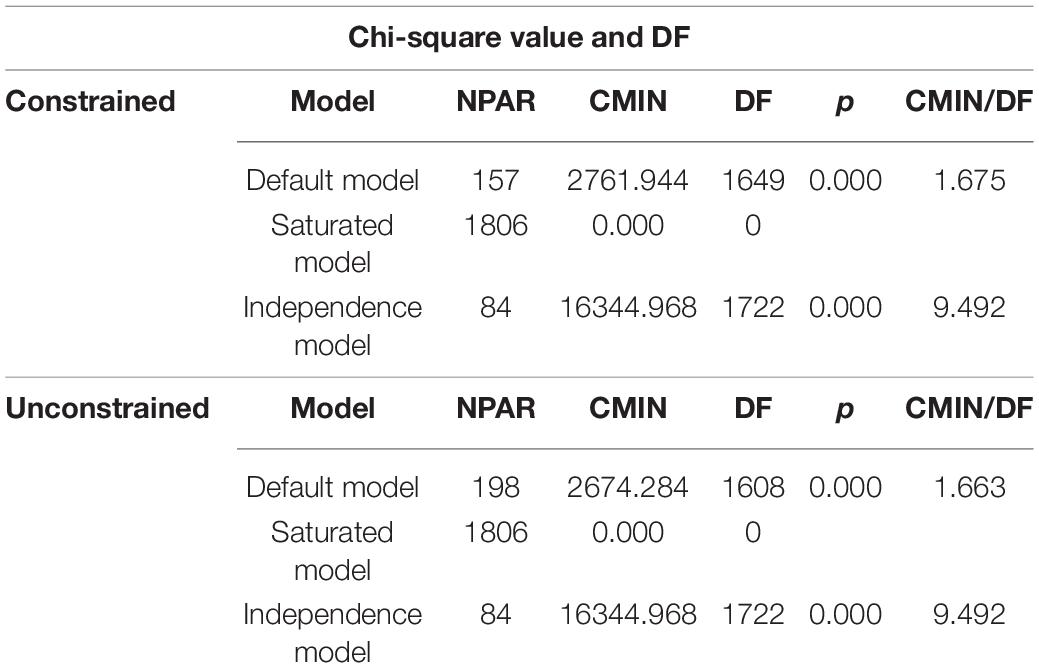

Table 6 shows the differences in chi-square values between the constrained and unconstrained models for path testing. The difference in chi-square values between experienced teachers and novice teachers was 87.660 (2761.944-2674.284), and the difference in degrees of freedom was 41 (1,649-1,608), which is greater than 3.84. The result of the moderation test of teaching experience was significant.

Table 6. The chi-square value and DF for the constrained and unconstrained models for experienced teachers group.

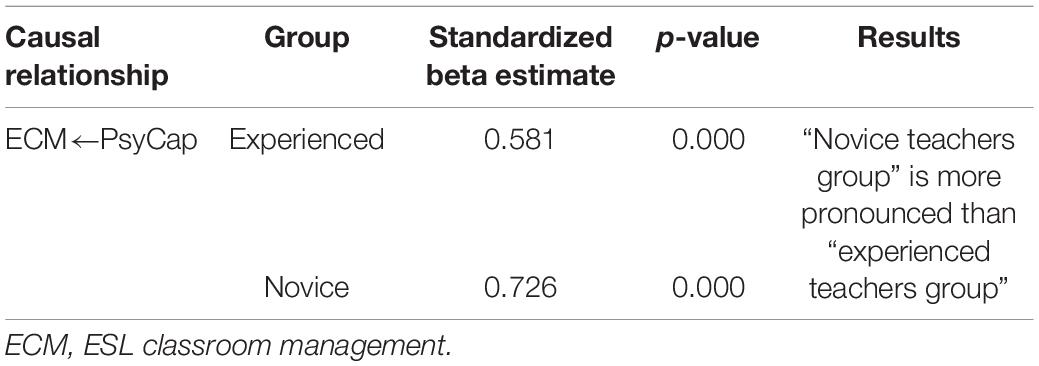

Table 7 shows that the standardized parameter estimates of PsyCap were 0.581 (p = 0.000) for the experienced teachers group and 0.726 (p = 0.000) for the novice teachers group. This result led us to conclude that the effect of PsyCap on ESL classroom management was greater in the novice teachers group than in the experienced teachers group.

Table 7. The effect of ESL teachers’ PsyCap on ESL classroom management for experienced and novice teachers’ groups.

Qualitative Findings

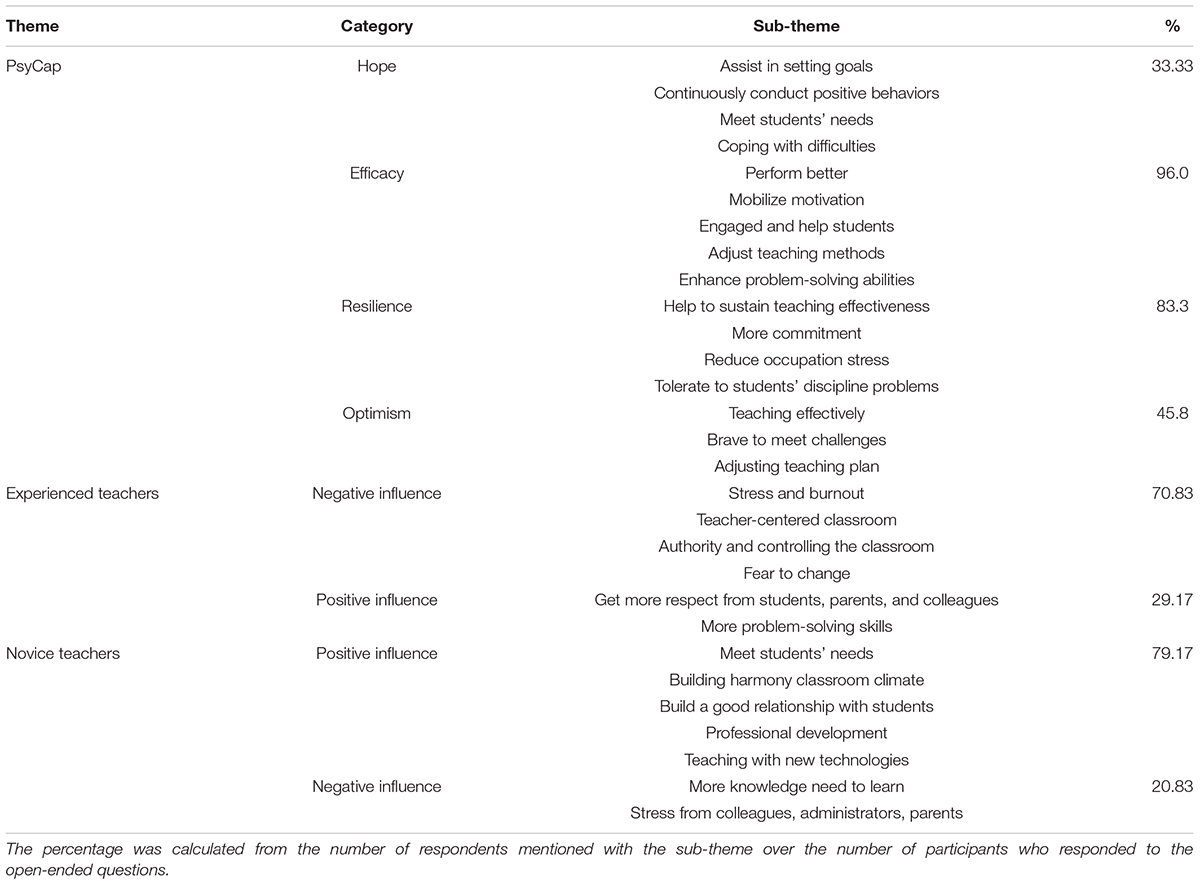

Effects of Psychological Capital on English as a Second Language Classroom Management

The responses to question 1 [How does PsyCap (hope, efficacy, resilience, and optimism) affect your classroom management?] were coded into four categories and 16 sub-themes (Appendix 1).

English as a Second Language Teachers’ Efficacy

Efficacy was the most commonly observed dimension, present in 96% of responses. For example, one teacher stated, “I can help students improve their English achievement. Having these beliefs, I was more likely to plan appropriate language lessons, maintain instructions with difficult students, meet challenges with more persistence, search harder for resources and materials and also take responsibility for their success and failure” (T15). Another respondent wrote, “I believe that students will be better if the students are active in the process of learning. I also keep student-centered teaching strategies to meet the students’ needs, approach challenging tasks, and recover from disappointment” (T17).

When individuals believe that they can act in a particular way to achieve a specific goal in a particular situation under certain conditions, they tend to be successful (Bandura, 1997). Teachers with efficacy show skill in incorporating different strategies into their lessons and are more effective than those with a less flexible instructional approach. The higher the efficacy teachers possess, the more they are likely to increase student interest and curiosity in learning and grow students’ cognitive abilities.

English as a Second Language Teachers’ Resilience

Resilience was the second most frequently observed dimension, appearing in 83.3% of responses. An example of resilience is the teacher’s response “In the classroom, students always made me feel anger, but I think I must be more patient and tolerate with my students. I must set an example for my students and not complain” (T24). Resilience in a teacher is the ability to adjust in response to various situations and become a more competent teacher to thrive in their profession rather than simply survive (Fredrickson, 2016).

English as a Second Language Teachers’ Optimism

The third and fourth most commonly observed dimensions were optimism and hope, which were observed in 45.8% and 33.3% of the responses. An example of optimism is in the response, “To be honest, I am optimistic about controlling my class. Although some troubled students made me a headache, I always use some innovative teaching methods to attract them to learn the language—I mean to make the students depth thinking to expect these students to understand my efforts” (T11).

Teachers showed positive expectations and displayed positive work attitudes and effective work behaviors. These attitudes affected their stress levels and helped them to reflect on their teaching methods.

English as a Second Language Teachers’ Hope

An example of hope is given in the response, “I often bothered by students’ discipline problems, particularly when students misbehavior escalated, I will make some plans or adjust my teaching methods know their demands” (T4). Hope is important for teachers because it increases their ability to cope with the stress of classroom management and the demands of students. Teaching is inherently stressful (Montgomery and Rupp, 2005), so teachers face an elevated risk of burnout. Hope can strengthen a teacher’s commitment to their work and help them cope with the challenges faced.

Psychological Capital of Experienced English as a Second Language Teachers

Responses to the second question (How does working experience affect your psychological capital and classroom management?) were classified as experienced or novice. The responses were subdivided into factors that had a negative influence and those that had a positive influence. Of the experienced teachers, 70.83% identified negative influences. One teacher responded, “I have taught English more than 10 years, and just like a teaching machine, repeat and repeat the teaching contents to students day and night. I do not know where is my new hope and directions.” Another teacher responded, “As a more than 12 years ESL teacher, I think I have some authority to tell how to manage and control class, don’t let me change my teaching method, I only want to remain the same” (T1).

In the group of experienced teachers, 29.17% of participants identified factors that were a positive influence. One teacher exemplified this theme by stating, “I can get more respect and understanding from parents, students, and colleagues because I have stayed at this school more than 15 years. They would like to consult me about classroom management issues. I would like to share these with them. I sometimes feel proud of” (T12).

Experienced teachers had less positive attitudes (PsyCap) toward their teaching, although they explicitly enjoyed working authority from parents, students, and colleagues. Stress and burnout might affect their acquisition of PsyCap. Malaysian work culture is such that experienced teachers often gain more power and resources than novice teachers. Experienced teachers have authority and high status in a school and are likely to be unwilling to change their behavior to support societal demands.

Psychological Capital of Novice English as a Second Language Teachers

Of the novice teachers, 79.17% of responses identified factors that were a positive influence. One teacher responded, “I have gained working experience in harsh conditions for 4 years, where there is a lack of sufficient recourse and support, but I think it made me more capable and braver to overcome difficulties. I gave students autonomy in my class, and they treated me like elder sister, they all like me” (T14). Another teacher responded, “Before entering school, the government provides the program (Native Speaker program) to train me how to manage the classroom. I learn a lot of skills and teaching methods from the program. When I enter into the classroom, I do not fear and am very confident to teach my students well” (T23).

Novice teachers identified negative factors found in 20.83% of their responses and were mainly associated with disagreements with administrators and colleagues, which hindered them in developing PsyCap. One teacher responded, “I have always tried to do it by many attempts, and it is our responsibility to create a conducive situation in the teaching processes. However, my colleagues and administrators seem that I need to learn more from experienced teachers, and they do not trust I can make it” (T16).

Psychological capital has a more significant effect in ESL classrooms for novice teachers than experienced teachers. Novice teachers take advantage of their PsyCap to learn and accept new things. PsyCap helps them meet student needs and improve their class management abilities. Novice teachers require training programs that encourage them to improve their professional competency and thereby reduce their anxiety surrounding their language competency. Training and professional development have increased the ability to innovate novice teachers and have enabled them to use new pedagogies such as flipped classrooms, blended learning, Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), micro-courses, and artificial intelligence courses.

Discussion

We investigated the effects of PsyCap on ESL classroom management in elementary teachers in Malaysia using a mixed-methods approach and found that teaching experience was a factor that moderated the effects of PsyCap on ESL classroom management.

Effects of Teacher Psychological Capital on English as a Second Language Classroom Management

Structural equation model analysis showed that PsyCap had a significant positive effect on elementary ESL teacher classroom management. This result supports hypothesis 1, which means that teachers with greater PsyCap put greater effort into classroom management. This finding is consistent with the outcomes of previous studies, such as Avey et al. (2010), Luthans et al. (2010), Fu (2014), and Lee et al. (2017), which all noted that teachers with a high level of PsyCap had a more positive attitude toward their performance at work.

This evidence can be contextualized by theory in line with the JD-R model, illustrating that those with higher PsyCap possess higher levels of internal resources from which to counteract the effects of the dual demands they are experiencing via classroom management. Higher resources are better equipped to overcome the demands faced. Thus, the findings would suggest PsyCap is a psychological resource and positively influences individual work attitudes and work performance. Moreover, higher PsyCap levels predicting higher classroom management is an especially important finding given the developmental capacities of PsyCap (Luthans et al., 2006, 2010, 2014). ESL teachers need to be able to adapt and redirect their plans (hope), have a positive belief that they can succeed (efficacy and optimism) and be resilient to setback (resilience). The current study indicates that ESL teachers who possess the resources to do this will improve their classroom management and teaching. This also provides further evidence to support the need to look at implementing PsyCap development interventions for ESL teachers to maximize their potential in teaching while also safe-guarding their wellbeing from burnout.

This research specifically related to the combined effects of the PsyCap components of hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism. ESL teachers who are more positive in their approach, have the belief to put in the required effort to succeed, persevere toward their goals and are able to overcome any setbacks they faced are in turn better equipped to be less susceptible to burnout. Analysis of the qualitative findings showed that many respondents found that Efficacy was the factor that most influenced teachers in using techniques to improve classroom management. Teachers who had high efficacy viewed themselves as adequate classroom managers who used their management skills to deal with unforeseen classroom situations. They developed caring relationships with students to meet students’ needs and control the classroom environment while fostering student responsibility for learning and engaged students in learning. Thus, administrators and educational policymakers in Malaysia must pay attention to the effects and benefits of PsyCap and provide PsyCap intervention, as described in Luthans et al. (2006), in order to increase awareness of the value of positive psychology in ESL education. For example, administrators could provide constructive feedback and identify those ESL teachers who are lower in PsyCap, therefore, are at a higher risk of burnout. This would enable early intervention to support those teachers in their teaching, which would help in their teaching. Another way is by enhancing PsyCap levels through developmental interventions akin to the one-off 2-hour session by Luthans et al. (2014), as this would increase wellbeing of teachers and reduce burnout. Having lower levels of burnout and more engaged ESL teachers would also be beneficial for education institutes more broadly.

Moderating Effect of Teaching Experience on the Effects of Psychological Capital on Classroom Management

Analysis showed that teaching experience had a significant effect in moderating the relationship between PsyCap and ESL classroom management. This result supports hypothesis 2. Thus, this evidence also strongly supported the JD-R model, where the presence of PsyCap and teaching experience play a vital role in teaching.

The quantitative analysis implies that PsyCap of novice ESL teachers increased their classroom management abilities to a level that made them superior to experienced teachers in this respect. However, it is surprising that the role of teaching experience was not replicated in relation to classroom management, which means more teaching experience is not equal to better classroom management. This result is consistent with the findings of Wang et al. (2014), Lee et al. (2017), and Mesurado and Laudadío (2019). However, the result drawn from this study is different from Weinstein (1996) and Stoughton (2007). Analysis of the qualitative data showed that novice teachers could create a classroom environment in which students were comfortable, set achievement goals that inspired student learning, and resolve a range of classroom problems. In creating a harmonious classroom environment and fostering good relationships with students, teachers increase their PsyCap and earn respect from students and parents who recognize their achievements. This approach promotes shared responsibility for classroom control and the development of classroom norms (Cakiroglu et al., 2005). Another reason is professional training, which is also vital to developing teacher PsyCap and classroom management skills. Novice teachers tend to integrate advanced pedagogical techniques into their ESL teaching to create an environment where students feel comfortable and confident when interacting with other students and teachers. Novice teachers in this study reported that the Native Speaker program inaugurated by the Malaysian government had a positive effect because it promoted positive values in teachers, increased their self-efficacy, promoted positive perception of the teaching profession, and inspired teachers to increase their PsyCap. These benefits can transform a teacher who has developed a teacher-centered classroom into better developed professionally, has more positive interactions with their students, and can minimize the adverse effects of any classroom management issues (Jin and Jun Zhang, 2018).

Qualitative responses indicated that experienced teachers often expect their students to follow classroom rules and principles already in place. They believe that a teacher has full responsibility for student learning, and so they focus on student behaviors to quickly redirect negative behavior to positive behavior and use established behavioral management techniques (Swanson et al., 1990). As teachers become more experienced, they become more controlling in both behavioral and instructional management. This rapidly leads them into conflicts with students and can destroy previously good teacher-student relationships as teachers attempt to pursue their own goals that may conflict with student goals and maintain formal authority in the classroom. This behavior also increases teacher stress and reduces their PsyCap; it reduces classroom activity and discourages teachers from interacting with students.

Analysis of the sub-themes in qualitative responses showed that experienced teachers become part of an existing culture that dictates the way things are done. In contrast to many Western countries, Malaysia is a country that prizes social conformity, so experienced teachers must constantly ensure they meet existing cultural norms and are thus reluctant to implement newly learned strategies (Johnson and Kardos, 2002). Without hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism, they lose the courage to make changes. This situation results in teachers becoming automata who follow everyday routines and lack self-reflection and think little about how they teach or what they are teaching.

Therefore, policymakers and school administrators in Malaysia must consider PsyCap as crucial to teaching ESL effectively and create programs that develop PsyCap. Equally, experienced teachers should demand training to improve their PsyCap and other practical professional skills. Schools must also work to create consistently harmonious school environments that help teachers to overcome their limitations.

Conclusion

Psychological capital is a concept that has only recently been introduced into ESL teaching in Malaysia. This study shows that teaching experience is a factor that cannot be ignored because it moderates the relationship between PsyCap and classroom management for elementary ESL teachers in Malaysia.

One limitation of this study is that only elementary ESL teachers in Malaysia were subjects, so the results might differ if pre-elementary and high school teachers or college and university lecturers had been included. Another limitation is that data were collected at a single point in time. Future longitudinal experimental studies may facilitate more comprehensive causal analysis. Finally, due to COVID-19 and the Malaysia movement control order, the data used in this study were collected through an online survey; future research might consider a greater variety of epistemological and methodological techniques, such as classroom observation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The study involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Education Department of University of Malaya and Education Department of Zhejiang Province, China (2017SCG387). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

YW designed, collected, and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. HT and SLL edited the draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Language and Culture Research Institute of Zhejiang Yuexiu University (2019WGYYWH01).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Adil, A., and Kamal, A. (2020). Authentic leadership and psychological capital in job demands-resources model among Pakistani university teachers. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 23, 734–754. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2019.1580772

Akbari, R., and Bolouri, M. (2015). Development and validation of an ELT based classroom management questionnaire. J. Linguist. Lang. Res. 4, 113–129. doi: 10.1080/03054980701614978

Ali, S. H., Foreman, J., Capasso, A., Jones, A. M., Tozan, Y., and DiClemente, R. J. (2020). Social media as a recruitment platform for a nationwide online survey of COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, and practices in the United States: methodology and feasibility analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 20:116. doi: 10.1186/sl2874-020-01011-0

Avey, J. B., Luthans, F., and Youssef, C. M. (2010). The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 36, 430–452. doi: 10.1177/0149206308329961

Avey, J. B., Reichard, R. J., Luthans, F., and Mhatre, K. H. (2011). Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 22, 127–152. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20070

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). Dual processes at work in a centre: an application of the job-demands-resources model. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 12, 393–417. doi: 10.1080/13594320344000165

Bakker, A., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: state of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010069

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol. Rev. 84, 191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191

Berger, J. L., Girardet, C., Vaudroz, C., and Crahay, M. (2018). Teaching experience, teachers’ beliefs, and self-reported classroom management practices: a coherent network. SAGE OPEN 8, 1–12.

Boldrini, E., Sappa, V., and Aprea, C. (2018). Which difficulties and resoures do vocational teachers’ resilience in Switzerland. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 25, 125–141. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1520086

Burhanuddin, N. A. N., and Ahmad, N. A. (2018). Psychological capital and well-being among Malaysian Teacher. Can. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 14, 163–168. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147308

Cakiroglu, J., Cakiroglu, E., and Boone, W. (2005). Pre-service teacher self-efficacy beliefs regarding science teaching: a comparison of pre-service teachers in Turkey and the USA. Sci. Educ. 14, 31–40.

Chacon, C. T. (2005). Teachers’ perceived efficacy among English as a foreign language teachers in middle school in Venezuela. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.01.001

Cheung, G. W., and Wang, C. (2017). Current Approaches for Assessing Convergent and Discriminant Validity with SEM: Issue and Solutions. Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management.

Coleman, H., and Unrau, Y. A. (2008). “Qualitative data analysis,” in Social Work Research and Evaluation Foundations for Evidence-Based Practice, 8th Edn, eds R. M. Grinnell and Jr. Y. A. Unrau (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 370–386.

Datu, J. A. D., and Valdez, J. P. M. (2019). Psychological capital is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction and school belongingness. Sch. Psychol. Int. 40, 331–346. doi: 10.1177/0143034319838011

Delale-O’Connor, L. A., Alvarez, A. J., Murray, I. E., and Milner, H. R. (2017). Self-efficacy beliefs, classroom management, and the cradle-to-prison pipeline. Theory Pract. 56, 178–186. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2017.1336038

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 86, 49–52.

DeVries, H., Elliott, M. N., Kanouse, D. E., and Teleki, S. S. (2008). Using pooled kappa to summarize interrater agreement across many items. Field Methods 20, 272–282. doi: 10.1177/1525822x08317166

Ergün, P. A., and Dewaele, J. M. (2021). Do well-being and resilience predict the Foreign Language teaching enjoyment of teachers of Italian? System 99:102506. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102506

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Fredrickson, B. L. (2016). “The eudaimonics of positive emotions,” in Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-Being, ed. J. Vitterso (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 183–190. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-42445-3_12

Fu, C. S. (2014). An exploration of the relationship between psychological capital and the emotional labor of Taiwanese preschool teachers. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. 7, 226–246.

Gabryś-Barker, D., and Gałajda, D. (2016). Positive Psychology Perspectives on Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Gkonou, C., and Mercer, S. (2017). ). Understanding Emotional and Social Intelligence among English Language Teachers. London: British Council.

Goddard, J., and Foster, R. (2011). The experiences of neophyte teachers: a critical constructivist assessment. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 349–365. doi: 10.1016/s0742-051x(00)00062-7

Hagger, H., and McIntyre, D. (2000). What can research tell us about teacher education? Oxf. Rev. Educ. 26, 483–495. doi: 10.1080/713688546

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edn. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2014). A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Hicks, S. D. (2012). Self-Efficacy and Classroom Management: A Correlation Study Regarding the Factors that Influence Classroom Management. Doctoral dissertation. Lynchburg, VA: Liberty University.

Hoy, A. W., Hoy, W. K., and Kurz, N. (2008). Teacher’s academic optimism: the development and test of a new construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 821–834. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2007.08.004

Jin, J., Mercer, S., Babic, S., and Mairitsch, A. (2021). “Understanding the ecology of foreign language teacher wellbeing,” in Positive Psychology in Second and Foreign Language Education. Second Language Learning and Teaching, eds K. Budzińska and O. Majchrzak (Cham: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-3-030

Jin, Y. X., and Dewaele, J. M. (2018). The effect of positive orientation and perceived social support on foreign language classroom anxiety. System 74, 149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.01.002

Jin, Y. X., and Jun Zhang, L. (2018). The dimensions of foreign language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign language achievement. Int. J. Biling Educ. Biling 24, 948–962. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1526253

Katz, A. (2017). “The argument for developing teachers’ classroom english proficiency,” in The Intervention: The Design of the English-for-Teaching Course, developing classroom English Competence: Learning from Vietnam Experience, eds D. Freeman and L. L. Drean (Phnom Penh: IDP Education (Cambodia) Ltd.), 1–7. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.2020120

Kumarakulasingam, T. M. (2002). Relationships Between Classroom Management, Teacher Stress, Teacher Burnout, and Teachers’ Levels of Hope. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansa Psychology and research in education.

Lee, H. M., Chou, M. J., Chin, C. H., and Wu, H. T. (2017). The relationship between psychological capital and professional commitment of preschool teachers: the moderating role of working years. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 5, 891–900. doi: 10.13189/UJER.2017.050521

Liu, L., Chang, Y., Fu, J., Wang, J., and Wang, L. (2012). The mediating role of psychological capital on the association between occupational stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese physicians: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 12:219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-219

Luthans, B. C., Luthans, K. W., and Avey, J. B. (2014). Building the leaders of tomorrow: the development of academic psychological capital. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 21, 191–199. doi: 10.1177/1548051813517003

Luthans, F., and Youssef-Morgan, C. M. (2017). Psychological capital: an evidence-based positive approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 4, 339–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113324

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., and Peterson, S. (2010). The development and resulting performance impact of positive psychological capital. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 21, 41–67. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.20034

Luthans, F., Avey, J. B., Avolio, B. J., Norman, S. M., and Combs, G. M. (2006). Psychological capital development: toward a micro-intervention. J. Organ. Behav. 27, 387–393. doi: 10.1002/job.373

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., and Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 60, 541–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570

Luthans, K. W., Luthans, B. C., and Palmer, N. F. (2016). A positive approach to management education: the relationship between academic PsyCap and student engagement. J. Manag. Dev. 35, 1098–1118. doi: 10.1108/jmd-06-2015-0091

Ma, K., and Cavanagh, M. S. (2018). Classroom ready? Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy for their first professional experience placement. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 134–151. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v43n7.8

Macías, D. F. (2018). Classroom management in foreign language education: an exploratory review. Profile: issues in teachers’. Prof. Dev. 20, 153–166. doi: 10.15446/profile.v20n1.60001

MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (2019). Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: theory, practice and research. Mod. Lang. J. 103, 262–274. doi: 10.1111/modl.12544

Mackey, A., and Gass, S. M. (2005). Second Language Research: Methodology and Design. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mesurado, B., and Laudadío, J. (2019). Teaching experience, psychological capital and work engagement. their relationship with burnout on university teachers. Propós. Represent. 7, 12–40. doi: 10.20511/pyr2019.v7n3.327

Moafian, F., and Ghanizadeh, A. (2009). The relationship between Iranian EFL teachers’ emotional intelligence and their self-efficacy in language institutes. System 37, 708–718. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2009.09.014

Moghtadaie, L., and Hoveida, R. (2015). Relationship between academic optimism and classroom management styles of teachers–case study: elementary school teachers in Isfahan. Int. Educ. Stud. 11, 184–192. doi: 10.5539/ies.v8n11p184

Montgomery, C., and Rupp, A. (2005). A meta-analysis for exploring the diverse causes and effects of stress in teachers. Can. J. Educ. 28, 461–488. doi: 10.2307/4126479

Newman, A., Ucbasaran, D., Zhu, F., and Hirst, G. (2014). Psychological capital: a review and synthesis. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 120–138. doi: 10.1002/job.1916

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 875–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Poulou, M. S., Reddy, L. A., and Dudek, C. M. (2019). Relation of teacher self-efficacy and classroom practices: a preliminary investigation. Sch. Psychol. Int. 40, 25–48. doi: 10.1177/0143034318798045

Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 50, 325–327. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211004138

Rabenu, E., and Tziner, A. (2020). Applying psychological capital to senior management development a “must” and not “nice to have”. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 15, 62–66. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v15n2p62

Ronald, B. (2016). Teacher Self-Efficacy, Dispositional Optimism, Resiliency, and Student Behaviour Management in the High School Classroom in Puerto RICO: ProQuest Number: 10149242. Ph.D. thesis. San Juan, PR: University of Puerto Rico.

Scheier, M. F., and Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol 4, 219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219

Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., and Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxf. Rev Educ 35, 293–311. doi: 10.1080/03054980902934563

Snyder, C. R. (1994). The Psychology of Hope: You Can Get there from Here. New York, NY: Free Press.

Stavraki, C., and Karagianni, E. (2020). Exploring Greek EFL teachers’ resilience. J. Psychol. Lang Learn. 2, 142–179. doi: 10.52598/jpll/2/1/7

Stoughton, E. H. (2007). “How Will I Get Them to Behave?”: pre service teachers reflect on classroom management. Teach. Teach. Educ 23, 1024–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.05.001

Swanson, H. L., O’Conner, J. E., and Cooney, J. B. (1990). An information processing analysis of expert and novice teachers’ problem solving. Am. Educ. Res. J. 27, 533–556. doi: 10.3102/00028312027003533

Tasci, G., and Atar, B. (2016). Developing a scale for perceptions of competency in teaching quality. Univ. J. Educ. Res. 4, 878–885. doi: 10.13189/ujer.2016.040425

Tilfarlioglu, F. Y., and Ulusoy, S. (2012). Teachers’ self-efficacy and classroom management skills in EFL classrooms. Electron. J. Educ. Sci. 1, 37–57.

Tsui, A. S., and Gutek, B. (1999). Demographic Differences in Organizations: Current Research and Future Directions. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Tsui, A. S., Egan, T. D., and O’Reilly, C. A. (1992). Being different: relational demography and organizational attachment. Admin. Sci. Q. 37, 549–579. doi: 10.2307/2393472

Tugade, M. M., and Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). “Positive emotions and emotional intelligence,” in The Wisdom of Feelings, eds L. Feldman Barrett and P. Salovey (New York, NY: Guilford), 319–340.

Viera, A. J., and Garrett, J. M. (2005). Understanding interobserver agreement: the Kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 37, 360–363.

Wang, J. H., Chen, Y. T., and Hsu, M. H. (2014). A case study on psychological capital and teaching effectiveness in elementary schools. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 6, 331–337. doi: 10.7763/IJET.2014.V6.722

Weinstein, C. S. (1996). Secondary Classroom Management: Lessons from Research and Practice. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Wiersema, M. F., and Bantel, K. A. (1992). Top management team demography and corporate strategic change. Acad. Manag. J. 35, 91–121. doi: 10.2307/256474

Wolff, C. E. (2021). Classroom management scripts: a theoretical model contrasting expert and novice teachers’ knowledge and awareness of classroom events. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 131–148. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09542-0

Wolff, C. E., van den Bogert, N., Jarodzka, H., and Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2014). Keeping an eye on learning: differences between expert and novice teachers’ representations of classroom management events. J. Teach. Educ. 66, 68–85. doi: 10.1177/0022487114549810

Appendix

Keywords: PsyCap, teaching experience, Malaysia, ESL, elementary teachers

Citation: Wu Y, The HT and Lai SL (2022) Psychological Capital and English as a Second Language Classroom Management in Malaysia: The Moderating Effect of Teaching Experience. Front. Educ. 7:678639. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.678639

Received: 10 March 2021; Accepted: 04 April 2022;

Published: 27 April 2022.

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas, United StatesReviewed by:

Anisa Cheung, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaHarwati Hashim, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2022 Wu, The and Lai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Wu, ZWRsaWx5OTI3QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Yong Wu

Yong Wu Hery Tanto The2

Hery Tanto The2 Siow Li Lai

Siow Li Lai