- Research Division, Cambridge University Press & Assessment, Cambridge, United Kingdom

When completing a comparative judgment (CJ) exercise, judges are asked to make holistic decisions about the quality of the work they are comparing. A key consideration is the validity of expert judgements. This article details a study where an aspect of validity, whether or not judges are attending to construct-irrelevant features, was investigated. There are a number of potentially construct-irrelevant features indicated in the assessment literature, and we focused on four features: appearance; handwriting; spelling, punctuation, and grammar (SPaG); and missing response vs. incorrect answer. This study explored this through an empirical experiment supplemented by judge observation and survey. The study was conducted within an awarding organisation. The particular context was within a programme of work trialling, a new method of maintaining examination standards involving the comparative judgement of candidates’ examination responses from the same subject from two different years. Judgements in this context are cognitively demanding, and there is a possibility that judges may attend to superficial features of the responses they are comparing. It is, therefore, important to understand how CJ decisions are made and what they are or are not based on so that we can have confidence in judgements and know that any use of them is valid.

Introduction

The study was conducted within an English awarding organisation, where each year thousands of candidates’ examination scripts1 are scrutinised by trained experts. We often think of marking as the primary activity within this context; however, there are other routine activities that involve a holistic assessment of scripts, namely standard setting (deciding on a cut-score for a grade boundary) and standard maintaining (ensuring the chosen cut-score represents the same standard as previous years). Recently, a programme of work exploring an alternative method for standard maintaining was conducted that used comparative judgment (CJ) of candidates’ examination scripts (henceforth scripts). In the process of trialling this method, a key consideration is the validity of expert judgements. This article details a study where an aspect of validity, whether or not judges are attending to construct-irrelevant features, was investigated. An evaluation of the method itself is beyond the scope of this study and is presented in Benton et al. (2020b,2022).

In a framework for evidencing assessment validity developed by Shaw et al. (2012), one of the central validation questions is “Are the scores/grades dependable measures of the intended constructs?” (p.167). It follows that, for scores to be valid, judgements informing them must also be based on the intended constructs. The emphasis on intended constructs noted here is key for CJ; judges should base their decisions on construct-relevant features and avoid any influence of construct-irrelevant features (Messick, 1989). For example, in the assessment context, judgements influenced by an appropriate use of terminology would be construct-relevant, whereas those based on the neatness of handwriting would not be. CJ is a technique whereby a series of paired or ranked judgements (typically made by multiple judges) is used to generate a measurement scale of artefact quality (Bramley, 2007; Pollitt, 2012a,b). For example, pairs of candidate scripts can be compared in order to judge which script in each pair is the “better” one or packs of scripts can be ranked in order from best to worst. Analysis of these judgements generates an overall rank order of artefacts, in this case, scripts, and a scale of script quality (in logits) is created with each script having a value on this scale. One of the main advantages of CJ is that it requires judges to make relative judgements, which are sometimes considered to be easier to make than absolute judgements, e.g., of an individual script against a mark scheme (Pollitt and Crisp, 2004).

When completing a CJ exercise, judges are asked to make holistic decisions about the quality of the work they are comparing. Judges are not given specific features to focus on; instead, they draw on their experience to make the judgements. In an assessment context, this open holistic nature of the decision is very different from that of a traditional marking decision, which often follows a strict mark scheme. This difference is exacerbated if the judgement increases from an item-based decision to one based on an entire script.

When making holistic decisions, judges can decide what constitutes good quality; in practice, this conceptualisation can vary across judges. If judges are attending to construct-irrelevant features, then this could have implications for validity. In addition, as each script is viewed by multiple judges, the final rank order is determined by the combined decision-making of multiple judges. If judges’ conceptualisations do not cover every relevant dimension of the construct, then this again has implications for validity (van Daal et al., 2019). Thus, the validity of CJ is comprised of both the individual holistic nature of decision-making and the fact that the final rank order is based on a shared consensus or the collective expertise of judges (van Daal et al., 2019). A focus on construct-irrelevant features could impact both of these elements.

In a study investigating written conceptions of mathematical proof, Davies et al. (2021) explored which features judges collectively valued using CJ. One aspect of the study compared the CJ results of two groups of participants, the first comprised a group of expert mathematicians and the second comprised a group of educated non-mathematicians. This enabled divergent validity to be explored, i.e., judgements of the experts were based on mathematical expertise rather than on surface features such as grammar and quality of the writing. They found a modest correlation between the two sets of scores, and non-expert judges failed to produce a reliable scaled rank order for the writing samples. This study suggests that mathematical expertise was key to the task; however, it does not eliminate the possibility that attention was given to construct-irrelevant features.

Turning to assessment, “To date, not much is known about which aspects guide assessors’ decisions when using comparative methods” (Lesterhuis et al., 2018, p.3). Previous research investigating the validity of CJ decision-making has mostly utilised decision statements (Whitehouse, 2012; Lesterhuis et al., 2018; van Daal et al., 2019), and to our knowledge, there is only one experimental study (Bramley, 2009). A discussion of these studies will follow.

Decision statements are post-decision judge reflections “explaining or justifying their choice for one text over the other” (Lesterhuis et al., 2018, p.5), and they help to shed light on the criteria judges use. In a study using decision statements to explore the validity of CJ decision-making in academic writing, van Daal et al. (2019) investigated whether there was full construct representation in the final rank order of essays. They found that, while the full construct was represented overall, representation did vary by judge. In addition, they found that additional construct-relevant dimensions were reported, suggesting that judges were drawing on their expertise. Lesterhuis et al. (2018) found that teachers considered wide ranging and multiple aspects of the text when investigating which aspects are important for teachers when making a CJ decision on argumentative texts. The teachers also paid great attention to more complex higher-order aspects of text quality. Interestingly, not all aspects were covered in each decision, suggesting some construct under-representation. The judges in this study also appeared to be utilising their experience. In a study involving teachers comparing geography essays, Whitehouse (2012) found that decision statements used the language contained in the assessment objectives and mark schemes. The judges would have been familiar with these mark schemes in their roles as teachers or examiners in the subject; Whitehouse speculated that this resulted in the creation of “their own shared construct” (p.12), which they used to make their decisions.

These three studies suggest that judges attended to multiple and varied construct-relevant aspects when making holistic decisions, and that they drew on their experience and shared construct. There are, however, limitations acknowledged by these authors in the use of specific research contexts and whether the method used fully elicited the entire range of aspects actually attended to. In addition, as with all self-report measures, there is a danger that judges may deliberately not report everything (e.g., as they know it is construct-irrelevant) or they may not know or be able to verbalise what they attended to.

Bramley (2009) attempted to circumnavigate these methodological issues by conducting a controlled experiment. He prepared different versions of chemistry scripts, where each pair of scripts differed with respect to only one potentially construct-irrelevant feature. In total, four features were manipulated across 40 pairs of scripts: (i) the quality of written English; (ii) the proportion of missing as opposed to incorrect responses; (iii) the profile of marks in terms of fit to the Rasch model; and (iv) the proportion of marks gained on the subset of questions testing “good chemistry.” These were then ranked by judges as part of a CJ exercise. The CJ script quality measures of the two versions were then compared to assess whether the feature in question influenced judgements. The method was successful in identifying that the largest effects were obtained for the following features: (ii) scripts with missing responses were ranked lower on average than those with incorrect responses and (iv) scripts with a higher proportion of good chemistry items were ranked higher on average than those with a lower proportion.

This Study

This study seeks to build on previous research to further explore judge decision-making, specifically whether or not judges are attending to construct-irrelevant features when making their CJ decisions. We did this by conducting an empirical experiment supplemented by judge observation utilising a think-aloud procedure and a post-task survey. Thus, we combined the objectivity of an experimental study with the richness of judges’ verbalisations and actions and the explicitness of their post hoc reflection. If it was found that judges do pay attention to construct-irrelevant features when making judgements, then this has implications for how we use the results of CJ judgement exercises in this and potentially other contexts.

Standard maintaining, the context for our study, is the process whereby grade boundaries are set such that standards are maintained from 1 year to the next. CJ can be used in standard maintaining to provide information comparing the holistic quality of scripts from a benchmark test (e.g., June 18) with the holistic quality of scripts from a target test (e.g., June 19). Standard maintaining generally involves experts who are senior or experienced examiners. While these experts are used to the concept of holistic judgements, the current method used in England uses it in conjunction with statistical evidence. Making CJ decisions in this context without reference to any statistical or mark data, therefore, will be a novel experience for judges.

The explicit standard maintaining context itself adds another layer of complexity or difficulty to CJ decision-making, in that, it involves scripts from two different years. Judges, therefore, have to make complex comparisons (i) involving two sets of questions and answers and (ii) factoring in potentially differing levels of demand. These comparisons are cognitively demanding; it is, therefore, important to understand how CJ decisions are made and what they are or are not based on so that we can have confidence in the judgements.

The experimental method employed in this study draws on that of Bramley (2009) although set in a standard maintaining context. For this study, we also chose four construct-irrelevant features to investigate; however, all our script modifications were unidirectional (e.g., we always removed text to create missing responses), and we used a mixed-methods design incorporating judge observation with a think-aloud procedure.

There are a number of potentially construct-irrelevant features indicated in the assessment literature that could have an impact on marking or judge’s decision-making. The majority of the research is marking-based, and findings have been mixed, with results often dependent on the subject and research context. Modification of some of these features could legitimately lead to a change in mark or script quality measure (henceforth CJ measure) depending on the qualification. We restricted the choice of features to those which should not cause a legitimate change in mark/CJ measure in the qualification used in the study, i.e., these features were not assessed as part of the mark scheme. From these, a number of features were conflated into four categories for use in this study:

• Appearance: crossings out/writing outside the designated area/text insertions.

• Handwriting: the effort required for reading (word-processed scripts were not included).

• Spelling, punctuation, and grammar (SPaG)2.

• Missing: missing response vs. incorrect answer.

Findings from marking research that considered appearance reported that crossings out or responses outside the designated area decreased marker agreement (Black et al., 2011). This was even found for relatively straightforward items; Black et al. (2011) hypothesise “that the additional cognitive load of, say, visually dismissing a crossing-out, is enough to interfere with even simple marking strategies such as matching and scanning and hence increase the demands of the marking task” (p.10). Crisp (2013), in a study of teachers marking assessment coursework, found that two participants reported that features such as presentation and messy work are sometimes noted, where “the latter was thought to give the impression that the student does not care about the work” (p.10). Thus, negative predisposition to a script, in addition to increased cognitive load, may play a role in marking. To our knowledge, appearance has not been explored specifically in CJ tasks; this study investigated whether this feature interferes negatively with the complex demands of the CJ standard maintaining task.

The marking research findings around handwriting have been mixed, in varying contexts, and with few recent studies. Previous studies, described in Meadows and Billington (2005), have found that good handwriting attracted higher grades. This is perhaps because of the additional cognitive load involved in deciphering hard-to-read handwriting, e.g., it might take longer, cause frustration, or create doubt in the mind of the examiner. However, studies involving the United Kingdom examination boards with highly trained examiners and well-developed mark schemes have found no effect of handwriting on grades (Massey, 1983; Baird, 1998). In a second language testing context, Craig (2001) also found no influence of handwriting on test scores. In a study looking at the influence of script features on judgements in standard maintaining (not using CJ), paired comparisons, and rank ordering, Suto and Novakoviæ (2012) found that “no method was influenced to any great extent by handwriting” (p.17). It will be interesting to assess whether handwriting has an influence on highly trained examiners using an unfamiliar method of holistic comparative judgements as in this study.

Spelling, punctuation, and, grammar (SPaG) has been found to influence student marks (Stewart and Grobe, 1979; Chase, 1983). For many qualifications, SPaG is part of the assessment construct; as a result, there has been limited recent research exploring any construct-irrelevant influence in a marking context. However, in a CJ context, Bramley (2009) found that manipulating SPaG in scripts had little influence on CJ measures. Also, in a CJ context, Curcin et al. (2019) found that SPaG was noted by judges, but, in comparison to subject-specific features, they were “considered little” (p.90). It will be beneficial to establish whether judges in this demanding and novel context study are influenced by SPaG.

In terms of missing response vs. incorrect answer, Bramley (2009) found that manipulating this feature in a controlled CJ experiment resulted in scripts with the missing responses being ranked lower on average than those with incorrect answers. Although not statistically significant (possibly because of a large SE), the size of the effect was approximately two marks. In a review of CJ and standard maintaining in an assessment context, Curcin et al. (2019) found that, in English language, missing responses “may have been used to some extent as ‘quick’ differentiators between scripts irrespective of the detailed aspects of performance” (p.89). Within both English language and literature, they found that missing responses influenced participant judgements “sometimes making them easier and sometimes more difficult” (p.94). Experimental modification of this feature will help us determine its effect on CJ standard maintaining decisions.

The results of modifying these four features in this experiment would provide evidence of whether certain construct-irrelevant variables are influencing the judging process. In addition to the CJ measures obtained through the experiment, we also collected information about which features judges were observed to attend to and which they reported attending to when making their judgements. This was obtained via a simplified think-aloud procedure and a questionnaire.

Our research question is given as follows: Are judges influenced by the following construct-irrelevant features when making CJ decisions in a standard maintaining context?

• Appearance.

• Handwriting.

• SPaG.

• Missing response vs. incorrect answer.

Methods

Scripts

The study used a high-stakes school qualification typically sat at age 16 (GCSE). The examination was in Physical Education and was out of 60 marks. The format was a structured answer booklet that contained the questions and spaces for candidates to write their responses. There was a mixture of short answer and mid-length questions. This qualification was chosen because SPaG was not explicitly assessed. As the experiment was conducted in a standard maintaining context, it included scripts from both 2018 and 2019. As the features themselves are quite subjective, it was important for the researchers to establish a shared conceptualisation. Thus, before script selection took place, the researchers, in conjunction with the qualification manager, agreed definitions of the features (detailed in section “Features Defined”).

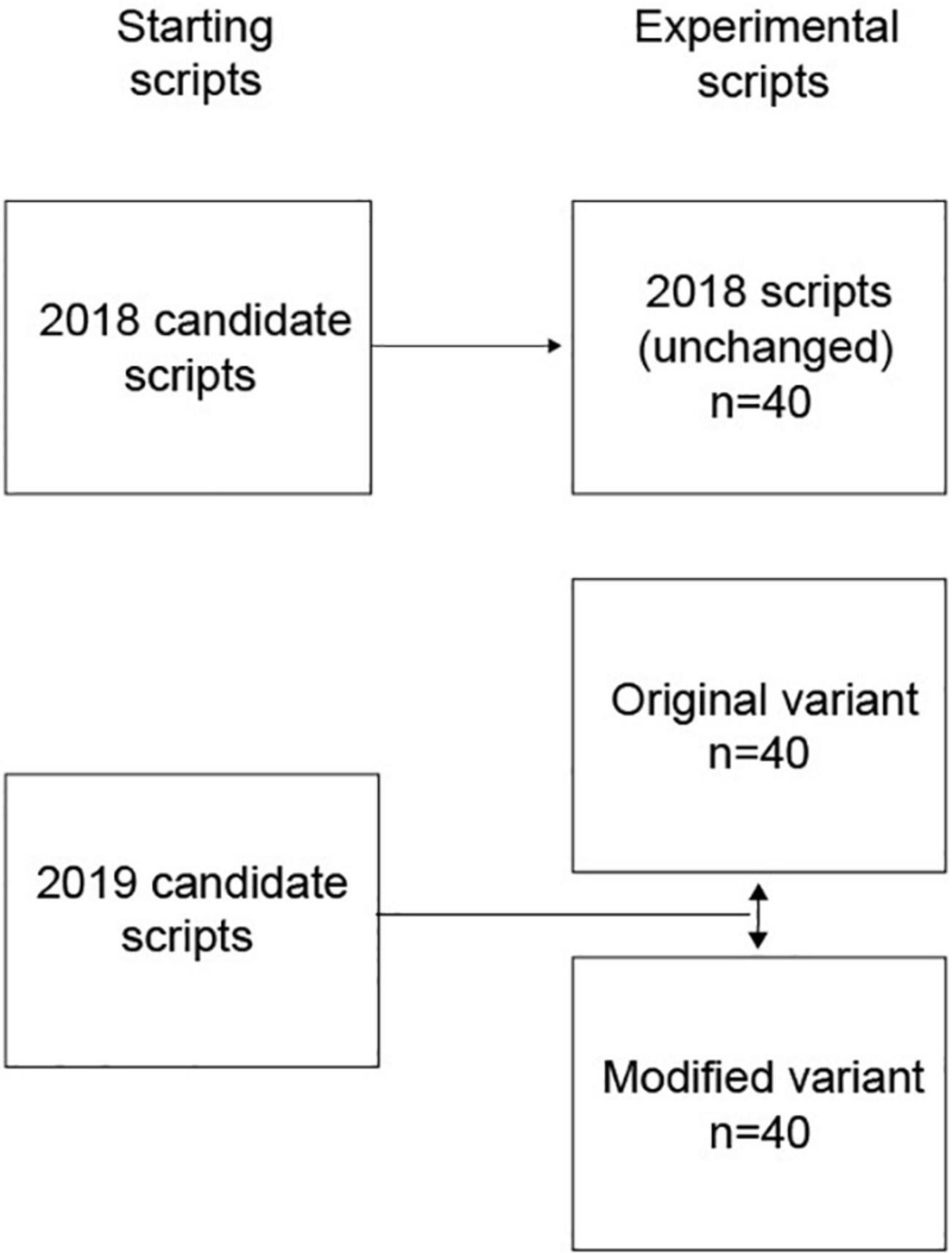

For each year, 40 scripts were used, with one script on each mark point between 11 and 50. For 2018, these were randomly chosen. For 2019, ten scripts that exemplified each of the four features were chosen such that the marks were evenly distributed across the mark range (approximately one script in every five-mark block). Figure 1 illustrates the scripts used in the study and how they relate to the starting scripts.

For the 2019 scripts, original and modified variants were needed. Modifications were made such that, if the modified scripts were re-marked in accordance with the qualification mark scheme, any changes should not result in an increase in mark. With the exception of the missing feature, the modified scripts were a positive variant of the feature in question, e.g., easier to read handwriting, improved SPaG, and neater appearance.

The researchers first detailed amendments that would be needed in the modified variants; for the SPaG and appearance features, these were checked by the qualification manager to ensure they were construct-irrelevant modifications. Forty volunteers were recruited to produce new variants of the 2019 scripts, with one volunteer per script. For SPaG, appearance, and missing features, both an original variant and a modified variant were made of each starting script. The original variant was a faithful reproduction of the starting script, just in the volunteer’s handwriting. The modified variant was identical to the newly created original one apart from the specified modifications. This was to ensure that the only variable of change between the two variants was the feature in question. For the handwriting feature, only a new variant was produced. Again, this was a faithful reproduction of the starting script with no changes other than the handwriting. The researchers checked all the scripts to ensure that the conditions had been met.

Features Defined

Appearance

This feature included crossings out, text insertions, arrows pointing to another bit of text, and writing outside of the designated area. Examination rules for what is and is not marked were adhered to when making modifications. For example, for longer answers, an examiner would ignore any crossed-out text, so it could be removed in the modified variants; where there were text insertions or writing outside of the designated area, these were inserted into the main body of the text or the additional answer space as appropriate.

Handwriting

When defining problematic handwriting, we focused on the overall “effort” that was required to read a script. Thus, we chose scripts that were difficult to read; in practice, some of these scripts, at first glance, looked quite stylish. Writing that looked messy, or even just basic and very unsophisticated, but was easy to read was not included. When faced with a script that is hard to read, it can be hypothesised that an expert may award it a lower mark/rank, purely because the expert cannot establish whether it is correct, i.e., not the handwriting per se. Conversely, such a script may be given benefit of the doubt and get an appropriate or higher mark/rank. It should be noted that in traditional marking, examiners are asked to seek guidance from a senior examiner in cases where they are unable to read a response.

Spelling, Punctuation, and Grammar

Nearly all of the scripts contained some instances of non-standard grammar or punctuation. The scripts with non-standard SPaG tended to either contain many spelling errors, with reasonable punctuation and grammar, or the opposite. Scripts with non-standard spelling had errors in simple words or in words that were clearly taught on the course or that had even been used in the question that was being answered. For example, there were instances of the words “pulmonary” and “reversibility” being spelled in different ways within the same answer. Examples of non-standard grammar were the incorrect use of articles before nouns (e.g., “some gymnast,” “these training programme”), the misuse of “they’re,” “their,” and “there” and of “your” and “you’re.” Punctuation was generally lacking across many of the answers. Many of the scripts selected had limited punctuation. Examples included longer answers that were just one long sentence, apostrophes that were repeatedly used in the wrong place or not used at all, and full stops that were repeatedly used with no following capital letter. All modifications were made with reference to the mark scheme.

Missing

Scripts featuring a relatively high proportion of items that received zero marks but containing no more than two non-response answers were selected. Responses to some of these zero marked items were replaced with a non-response. This was based on the item omit rate calculated from the live examination and on plausibility (e.g., multiple choice answers and answers to the first few questions on the paper were not removed). As a result, these scripts had between six and fourteen non-responses largely depending on their total mark.

Judges

Ten judges were recruited from the examiner pool for the qualification; they were all experienced markers, and, in addition, two had experience of standard maintaining. They were either current or retired teachers of the course leading to the qualification. All the judges, therefore, had knowledge of the assessment objectives of the qualification, and through their marking experience, they would have gained a conceptualisation of what makes a good quality script. The judges were given information about CJ, standard maintaining, instructions on how to do the task, and information about the nature of the study. In order to re-familiarise themselves with the papers, they were given the two question papers and associated mark schemes. They were not presented with grade boundaries, but it should be noted that these are available publicly. The two papers used in this study were actually of a similar level of demand, i.e., had similar grade boundaries.

The decision on the number of judges used in the study was informed from an approximate power calculation based on the number of scripts, the fact that each script would be seen by each judge, and findings from previous CJ activities. The number of scripts used was based on balancing practicality (how many packs of scripts judges could feasibly judge alongside their work commitments, how many volunteers we could recruit to make the modifications, etc.) and sufficiency (having enough scripts to detect a difference).

Research Procedure

The original and modified variant 2019 scripts along with the 2018 scripts were presented to the judges embedded in a CJ standard maintaining exercise. The scripts were organised into packs of four, with each pack containing two 2018 scripts and two 2019 scripts (both original, both modified, or one of each). Packs of four were chosen, as the ranking of a script within a larger pack is more informative than whether it wins or loses a single paired comparison, so potentially, it is more efficient. Thus, in each pack, we had six comparisons rather than one (AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, and CD). The ordering of the four scripts within a pack was random: sometimes the first script in the list would be from 2018 and sometimes from 2019. Script allocation to each pack in terms of original marks was also random; thus, any pack could potentially contain scripts of similar or widely distributed original marks. The scripts and judging plan were loaded onto the in-house software used to conduct the experiment. In total, each judge would rank 20 packs, and they would see all the 2018 scripts but would only see either the modified or the original variant of each of the 2019 scripts.

Judges were presented with packs of four scripts and instructed to “rank these in order from best to worst overall performance.” As the judges were all experienced examination markers of this qualification, they were asked to draw on this knowledge and experience and apply it to their CJ decisions. No additional criteria beyond the mark scheme were provided, although the judges were given additional guidance on how to make holistic judgements. This included information on the importance of making an evaluation of the whole script and using their professional judgement to allow for differences in the questions and the relative difficulty of each test. The judges were aware that we were exploring a new method of conducting standard maintaining and were looking at how they made judgements, but they were unaware of the script modifications. The judges were informed of the script modifications and presented with a summary of the research findings at the end of the study.

The lead author observed each judge for approximately 30 min while they were making their judgements. This observation was conducted on Microsoft Teams, at a time of the judge’s choosing; thus, it could be at the beginning, middle, or end of the judging period. The meeting software allowed the judges to share their screen, thereby allowing the observer to see what they were doing at any given point. This was supplemented by a think-aloud procedure in which the judges verbalised their thoughts while making their judgements. The judges were given the prompt “As you do the CJ task, we would like you to talk aloud about your actions, thoughts, and intentions. Please say anything that comes into your head while doing the task.” To familiarise the judges with thinking aloud, they were given a short practice exercise (counting the number of windows in their house). The observation was recorded with the software, and this produced an automated transcript.

Once the judges had completed their judging, they were invited to complete a short online questionnaire. This gave the judges the opportunity to provide feedback and enabled us to gather additional information on their judging behaviour. In the questionnaire, we specifically asked the judges how they made their decisions.

Analysis

A mixed-methods design was used, which comprised a quantitative element derived from the CJ decision data and a qualitative element derived from the observation and survey responses.

We were interested in judge behaviour and, thus, wanted to check the quality and consistency of the judging. For this, we used the CJ decision data to calculate judge fit statistics, “judge fit is determined with regard to how well their judgements agree with what would be expected given the CJ measures of each script derived from the Bradley–Terry model” (Benton et al., 2020a, p. 10). This method does not use script marks. Typically, fit statistics are examined with a view to assessing whether any judges were misfitting the model to such an extent that they might be affecting judges’ CJ decisions on the estimates of script quality. In some contexts, this might be a reason to exclude their judgements; but here, we were actually interested in the judges’ behaviour, so no judges were removed on the basis of their fit statistics. Although the CJ data was collected as ranks, they were converted into pairs for judge fit analysis (A beats B, A beats C, B beats C, etc.). The fit analysis was completed using the Bradley Terry model (Bradley and Terry, 1952), and standard CJ fit statistics, infit and outfit mean-square statistics, were calculated in R (Wright and Masters, 1990; Linacre, 2002).

The main focus of the quantitative analysis was to establish whether the modified and original variants were judged to be of similar quality. The ranked CJ decision data, collected with the CJ tool, were analysed3 using the Plackett-Luce model (Plackett, 1975). CJ measures were produced; these were based on which other scripts any given script were judged to be better or worse than and were calculated across multiple comparisons. These measures are logit values and are calculated for each script, indicating where a script sits on a constructed scale, which, in this case, was a measure of overall performance. As we were interested in whether the original and modified variants would be judged as being of similar quality, we compared the measures of the two variants. This was conducted by performing a paired t-test, which was calculated for each of the four features. Any significant results from the t-tests would indicate that the judges were attending to a particular construct-irrelevant feature when making their judgements. It should be noted that we treated the estimated CJ measures as error-free values (as we usually do with marks) in order to calculate t-tests; for this reason, their standard errors (SEs) were not utilised. Effect size was calculated using Cohen’s D. Using the slope of regression lines calculated from comparing original marks to CJ measures, an approximate conversion factor of 1 logit equaling 5 marks was used to interpret effect sizes (after Bramley, 2009).

The qualitative element comprised of judge observation and survey. Each of the 10 judges was observed while performing their judging for approximately 30 min. While the verbalisations provide an indication of features being attended to, these features may not necessarily affect the actual decision-making. However, the analysis of the observation data does provide additional context with which to interpret the empirical analyses. It is possible that the behaviour exhibited during the observation did not reflect the rest of the judging; however, given the candid comments made by the judges, the authors suggest that it is unlikely to have been fundamentally different.

The script recordings and auto-generated transcripts of the judge’s observations were loaded into qualitative analysis software. First, parts of the transcripts where the judges spoke about their decision-making or features they attended to were cleaned and corrected. Then, a targeted thematic analysis was conducted that involved coding across the four experimental features and other potentially construct-irrelevant features. As this was a simple coding exercise, looking at the presence or absence of mentions of the four features and any other potential construct-irrelevant feature, we involved only one researcher in the analysis, and no inter-rater coding reliability exercise was carried out. In order to maximise the accuracy of the data, the coding was completed in two stages; (1) when viewing the full recordings and (2) on a separate occasion through keyword analysis of the transcripts (using the text analysis tools available in the software). Responses to the post-task questionnaire were analysed along similar themes. When reporting the findings, all quotes are written in italics; those from the observations are written verbatim, and for those from the survey responses, spelling was corrected and punctuation was added to improve readability.

Pre-analysis Results

Before discussing the main findings, the judge fit statistics and information about the reliability of the CJ exercise are provided below.

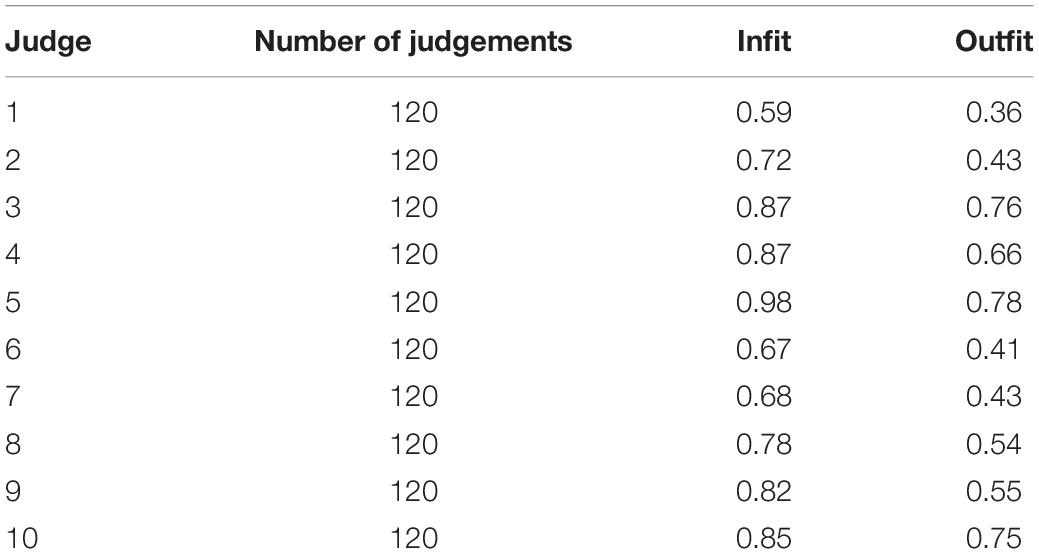

Judge Statistics

The infit values (Table 1) were all within an acceptable range [0.5–1.5 as stated by Linacre (2002)]. The outfit values for judges 1, 2, 6, and 7 were below 0.5, suggesting that the observations were too predictable. As stated previously, this analysis was performed to examine judge behaviour; the analysis suggested that the judges were not misfitting the model to such an extent that they were affecting the estimates of script quality.

Comparative Judgment Script Measures

The Scale Separation Reliability was 0.8, indicating that the logit scale produced from the judgements could be considered reliable given the number of comparisons per script (30 comparisons per script for the 2018 scripts and 15 for the 2019 scripts). For high-stakes and summative assessments, a value of 0.9 is often considered desirable [cited in Verhavert et al. (2019)]. However, in a meta-analysis of CJ studies, Verhavert et al. (2019) found that this was achieved when there was a greater number of comparisons per script (26–37 comparisons).

The CJ measures are the logit values on this scale and indicate the relative overall judged performance of each script. When original candidate marks were compared to the CJ measures using Pearson’s correlation, there was a strong relationship for the 2018 scripts [r(38) = 0.92, p < 0.01], indicating that candidate rank orders were similar for marking and the CJ judgements. The relationship is weaker for the 2019 scripts. The 2018 scripts were picked randomly, whereas the 2019 scripts were picked to exemplify certain characteristics and so could be considered “trickier” scripts to mark. This could explain the slightly weaker relationship between marks and measures and perhaps indicate that, for trickier scripts, there may be less similarity between marking and CJ. That the modified relationship [r(38) = 0.83, p < 0.01] was slightly weaker than the original [r(38) = 0.86, p < 0.01], which might indicate that the modifications are having an effect.

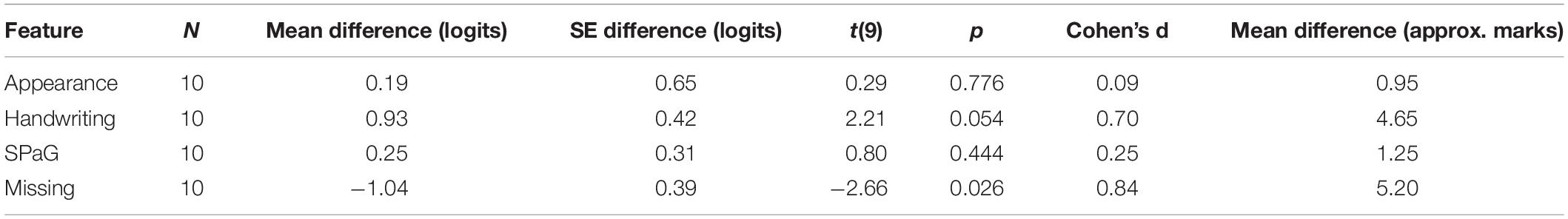

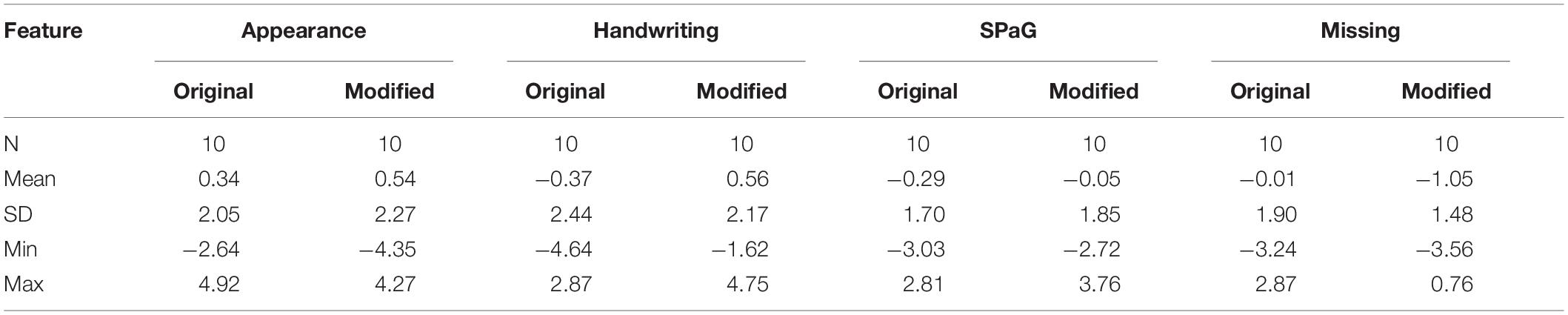

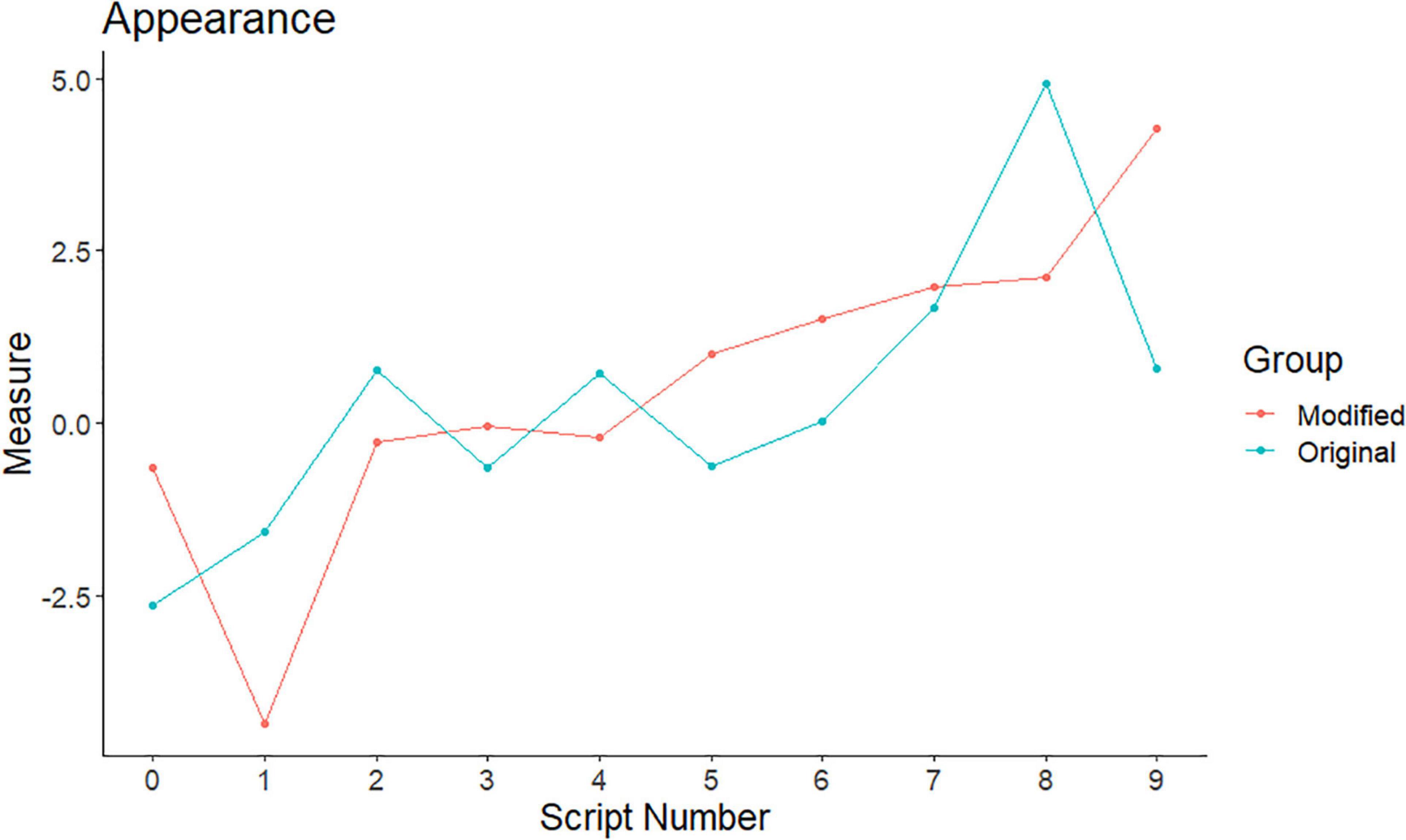

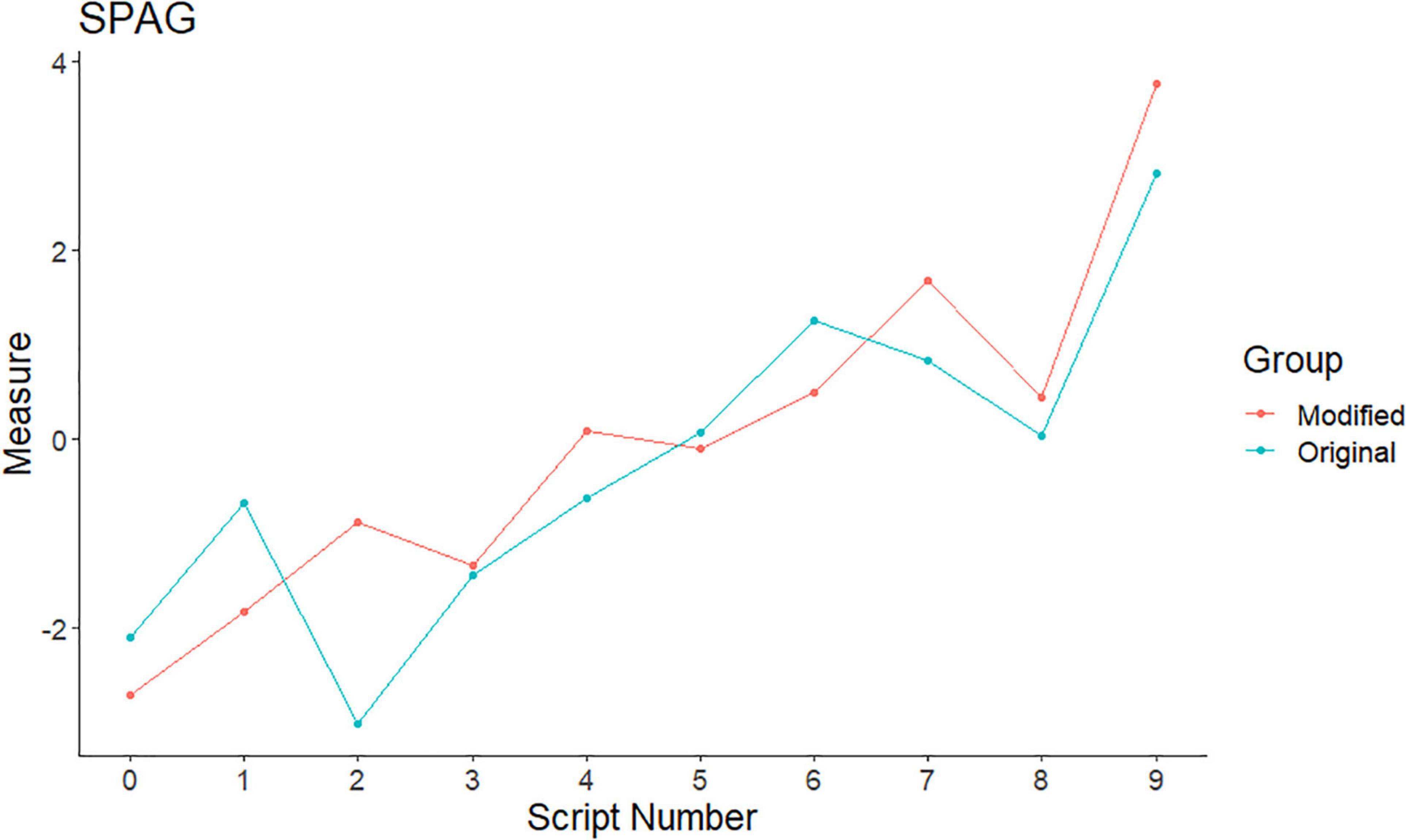

Findings

We examined the CJ measures of the four features under consideration. The descriptive statistics are shown in Table 2, and the paired t-test results for each feature are shown in Table 3.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the comparative judgment (CJ) measures for each of the four features.

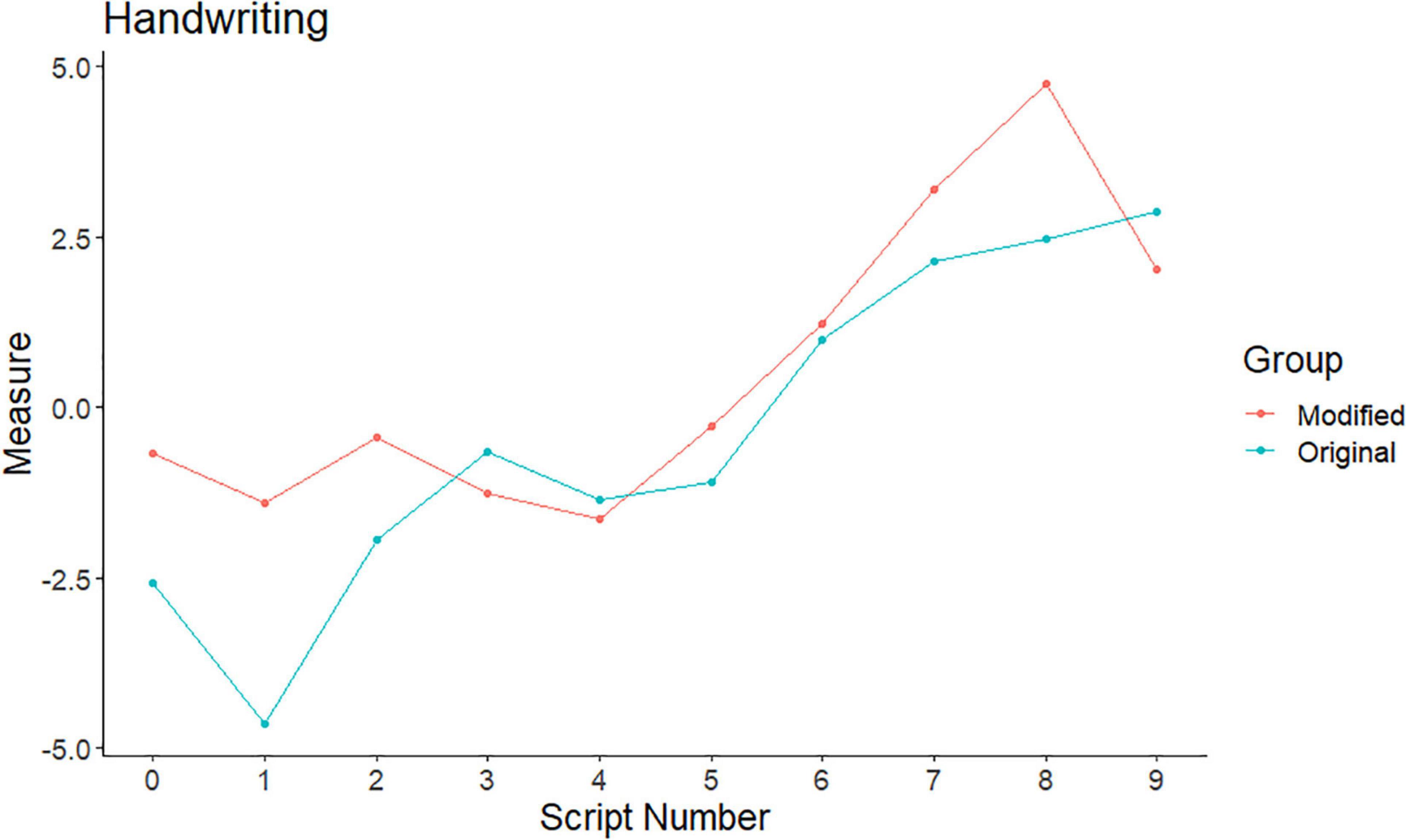

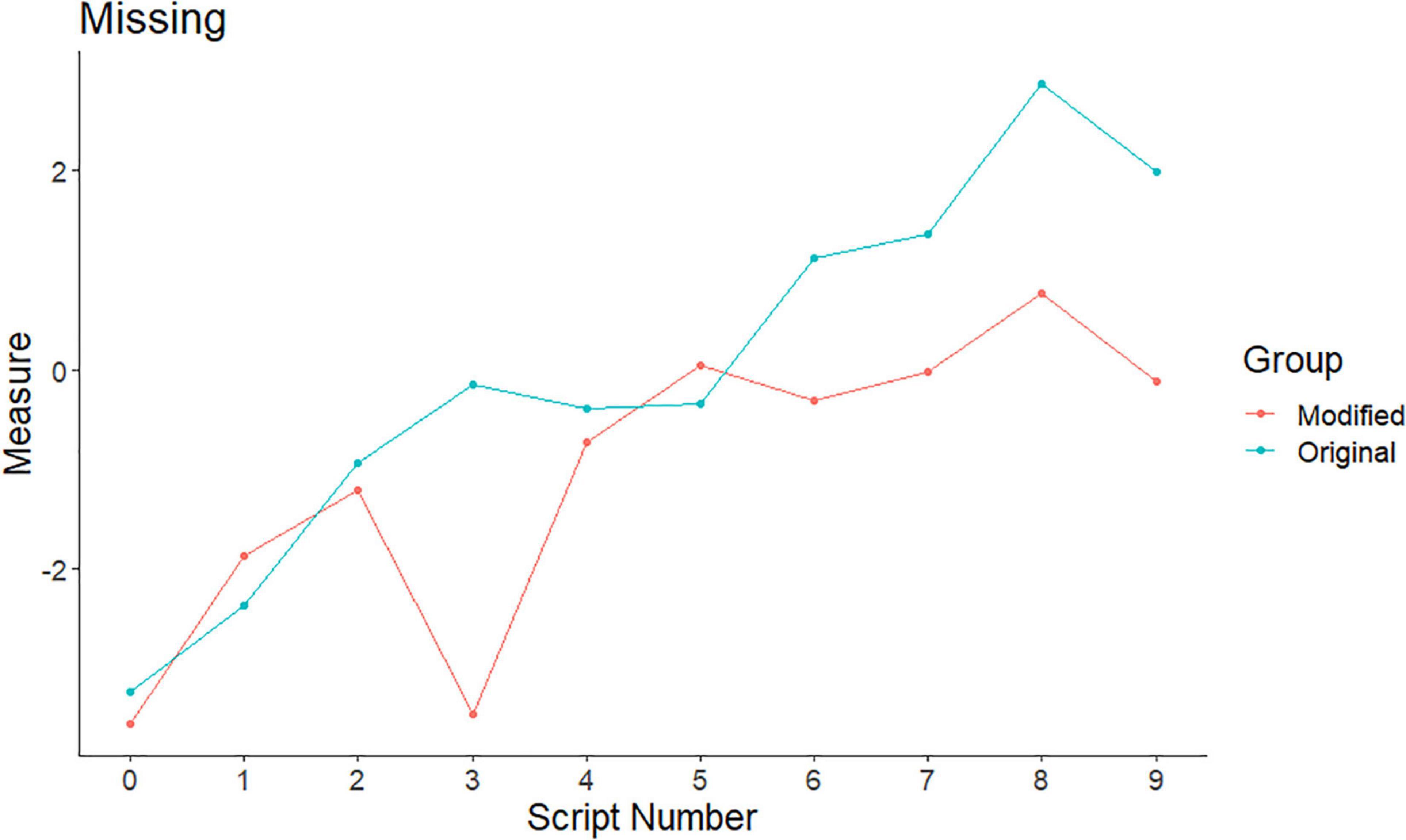

For each feature, the CJ measures of each variant were plotted against a script (Figures 2–5). Script numbers are listed on the x-axis; these range from 0 to 1, where 0 is the script with the lowest candidate mark and 9 is the script with the highest mark. As the scripts were chosen to be evenly spread across the mark scheme, we would expect the lines to go upward from left to right. They show whether any differences in measures between the two variants were consistent across the mark range.

Figure 2. Comparative judgment (CJ) measures for the original and modified script variants: appearance.

Figure 4. CJ measures for the original and modified script variants: spelling, punctuation, and grammar (SpaG).

Of the four features under consideration, the judges differed in whether they mentioned them during the observation (see Table 4). Since the observation was a “snapshot” of their judging, the presence or absence (rather than a count) of each feature was recorded. Only two judges (4 and 8) did not mention any of the four features during the observation. Handwriting, spelling, and missing responses were all reported in the survey responses. Appearance was not directly mentioned, but one participant mentioned “presentation.” We will now examine each feature in turn.

Appearance

The descriptive statistics in Table 3 show that, for the appearance feature, the mean CJ measures were quite similar for both the original (M = 0.34, SD = 2.05) and the modified (M = 0.54, SD = 2.27) variants. The range of measures was greater for the modified variant. The difference in mean measures was not significant [t(9) = 0.29, p = 0.776, d = 0.09], and in terms of approximate marks, the mean difference was less than one.

From Figure 2, we can see that the lines for the original and modified variants cross each other multiple times. This indicates that the modified CJ measure was higher for some of the scripts and the original variant was for others.

During the observation, half of the judges made reference to appearance features. The judges varied in how they expressed their comments, but they tended to be an observation or an aside that offered little explicit indication of whether this feature had influenced their judgements. Examples of appearance-specific comments included:

Few little crossings out, but things have been rewritten so that’s OK (Judge 10).

Again, lots of crossings out and rewriting things (Judge 10).

Things at the side, little arrows on it (Judge 10).

The crossing out in it doesn’t help in terms of seeing a students work (Judge 5).

You can see there straight away on the, [sic] on the first page we’ve got a crossing out (Judge 9).

Taken together, the results suggest that the judges were not unduly influenced by script appearance; this is in contrast to the findings of Black et al. (2011) in a marking study. Some of the papers in this experiment could be considered very messy, so it is an encouraging sign that the judges were not influenced by this.

Handwriting

For handwriting, the mean difference in measures was just under one logit (0.93), indicating that, on average, scripts with improved handwriting [modified variant (M = 0.56, SD = 2.17)] had higher CJ measures than the original variant (M = −0.37, SD = 2.44). This result was borderline significant [t(9) = 2.21, p = 0.054, d = 0.70]. The approximate effect of this was a mean difference in the marks of nearly five marks (4.65).

From Figure 3, we can see some defined trends. The modified scripts often had higher measures than the original scripts, particularly at the lower end of the script range. Where the modified scripts had lower measures, the difference was small.

Six of the judges made comments about handwriting; these were both positive and negative. The positive ones tended to describe being positively disposed to the writing, whereas the negative comments tended to be about not being able to read something and so not knowing if an answer was correct. Comments included:

Looking at this I can see it very clearly. The writing is lovely, which does help a marker (Judge 1).

The handwriting is clear. It helps with, with, with, with [sic] the handwriting. Sometimes you can’t, [sic] you can’t decipher what they say, in which therefore ultimately hampers the marks (Judge 5).

I can’t read that. I think it might say hamstrings (Judge 9).

I’m also looking at the actual writing itself. I have had a couple of them where the actual writing has been so bad, I couldn’t actually read it despite going over it again and again (Judge 10).

Just as an aside as well, not probably nothing to do with it. Sometimes you get put off by kids’ writing. Or if it’s really neat, yes, you, it can be quite positive towards especially on this when you are doing like reading through a paper. Whereas if I find if I’m doing all question ones [this refers to marking practice] and all questions twos you’ve not necessarily got that prejudice quite as obviously. Sometimes you gotta be careful with that, really, read kids marks (Judge 2).

Interestingly, in the survey two judges acknowledged handwriting as a potential issue that they tried to ignore:

… I tried to ignore quality of handwriting.

I did not focus on this when making my judgements, however, one area that could have had an impact was a students’ handwriting….

The results suggest that the judges are influenced both positively and negatively by handwriting when making CJ judgements. Not being able to read an answer both increases the cognitive load and genuinely hampers the judges decision-making capability, so it is understandable if this causes problems. Being positively disposed toward a paper is of particular concern, as it is less tangible and so harder to correct. Recent research findings on marking have not found an effect of handwriting (Massey, 1983; Baird, 1998), so it was notable and concerning that a borderline effect was found in this context where it was hidden in a holistic judgement and, therefore, non-traceable.

Spelling, Punctuation, and Grammar

For SPaG, the mean CJ measures were quite similar for both the original (M = −0.29, SD = 1.70) and modified (M = −0.05, SD = 1.85) variants. The difference in mean measures was not significant [t(9) = 0.80, p = 0.444, d = 0.25], and the mean difference in approximate marks was just over one.

Figure 4 shows that the measures were very close together for both features; only script 2 showed any sizeable difference (inspection of script 2 revealed no obvious reason for this). Again, the scripts varied as to whether the original or the modified variant had a higher measure. Four of the judges made comments on spelling, punctuation, or grammar and were not mentioned. Comments include: “Phalanges, even though spelt wrong, is the correct answer” and “It’s poor spelling.”

SPaG appears to have very little influence on the judges’ behaviour. This is encouraging, as it should not feature in the judgement of this paper. This is in line with other recent CJ studies (Bramley, 2009; Curcin et al., 2019) and, together, presents strong evidence that SPaG does not affect CJ judgements.

Missing

For missing, the mean difference in measures was just under one logit (−1.04), indicating that, on average, the original variant scripts (M = −0.01, SD = 1.90) had higher CJ measures than those where incorrect answers were replaced with a non-response (modified variant M = −1.05, SD = 1.48). The difference in mean CJ measures was significant [t(9) = −2.66, p = 0.026, d = 0.84]. The approximate effect of this was a mean difference in marks of just over five marks (5.2).

Figure 5 shows that the differences in measures were quite pronounced, particularly at the higher mark range. Interestingly, a closer examination of the judgements on scripts 4 and 5 (where the measures are closer together) shows that the judges were split in their opinions, whereas for script 3 and scripts 6–9, the judges were in agreement.

Seven of the judges made comments about missing answers, some were an observation, some were about balancing the missing responses to the quality of other answers, and some were comments on several people leaving out a certain answer. Comments included:

Some missing responses, not many (Judge 9).

I think this paper has a few more missing responses (Judge 9).

Far too many questions being missed out, so looking like what has been done, been answered is not actually that bad (Judge 10).

Just wanna check it against B though cos even though they have missed a lot of questions out what has been answered is pretty good (Judge 10).

They filled everything in, but the quality isn’t there (Judge 5).

OK, even though there are mistakes, but there are some questions are missed. They are actually answering to more detail (Judge 6).

There’s gaps once again, is a big gap in knowledge there, which means, OK, we’re going to be lowered down again in terms of ranking (Judge 5).

Decided to leave that blank and they’re not alone there (Judge 3).

The challenge caused by balancing unattempted questions with the quality of the rest of the scripts and the further inspection required were also reported in the survey responses.

This evidence indicates that having missing answers, as opposed to incorrect answers, does influence the judges. In line with previous research (Bramley, 2009; Curcin et al., 2019), the missing responses appear to have a negative effect on CJ measures, suggesting that the judges were more negatively predisposed to a missing answer than an incorrect one. This is of concern, again because the holistic context makes it a hidden bias. It was encouraging, however, to see some of the judges acknowledging that, although there were missing answers, they should balance that with the content of what else was in the paper.

Other Potentially Construct-Irrelevant Features

When making their judgements, the judges mentioned a number of different features. The majority of these were ones we might expect and were relevant to the construct or marking practice, e.g., whether the question was answered, the use of terminology or keywords, the use of supporting examples, giving the benefit of doubt, the vagueness of answers, and a candidate’s level. The survey responses corroborated this. Construct-relevant strategies cited in the survey were “number of correct answers,” “knowledge,” “the level of detail,” “use of technical language,” and the use of “practical examples.”

However, two features were mentioned, both in the think-aloud procedure and the survey responses, that could potentially be considered as construct-irrelevant; the use of exam technique and whether the candidates wrote in sentences. Both features were considered positive. Judges 4, 9, and 10 referred to “examination technique” which included things like underlining or ticking keywords in the question and writing down acronyms, e.g., “So we’ve got a bit of a plan up here with […] circling and underlining key points, which is what I like. This candidate’s obviously thinking about their response.” Only one judge (10) made reference to candidates writing in sentences and did this multiple times e.g., “They have tried to write in sentences, which is good.” It is encouraging that no other potentially construct-irrelevant features were mentioned in the observations or surveys, which hopefully implies that they were not being attended to.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study sought to explore judges’ decision-making in CJ, specifically to focus on one aspect of the validity of these judgements: whether judges were attending to construct-irrelevant features. As noted earlier, the validity of CJ is comprised of both the holistic nature of decision-making and a shared consensus of judges. Focus on construct-irrelevant features could impact both of these elements.

The study was conducted within an awarding organisation; the particular context was set within a series of studies trialling a new method of maintaining examination standards involving CJ. Judgements in this context are cognitively demanding, and there is a possibility that judges may attend to superficial features of the responses they are comparing. Our research question was as follows: Are judges influenced by the following construct-irrelevant features when making CJ decisions in a standard maintaining context?

• Appearance.

• Handwriting.

• SPaG.

• Missing response vs. incorrect answer.

We investigated this using a mixed-method design, triangulating the results from a quantitative element formed from an empirical experiment and a qualitative element formed from judge observations and survey responses. We found that the different sources of evidence collected in the study supported each other and painted a consistent picture.

The appearance and SPaG features did not appear to affect judges’ decision-making. For SPaG, this is in line with other recent CJ studies (Bramley, 2009; Curcin et al., 2019) despite some of the judges mentioning spelling in their observation/survey responses. For appearance, this had not been investigated in a CJ context; however, in a marking study, Black et al. (2011) found that appearance features did interfere with marking strategies. This study suggested that this interference was not strong enough to affect judging outcomes in this context. For both features, this is a positive outcome particularly given that the scripts were either very untidy or had many SPaG errors.

However, handwriting (to some extent) and missing responses vs. incorrect answers did appear to affect judges’ decision-making. For handwriting, this was particularly for scripts at the lower end of the mark range. Recent research findings on marking have not found an effect of handwriting, so it is notable and concerning that a borderline effect was found in this context where it was hidden in a holistic judgement and, therefore, non-traceable. However, the scripts used were difficult to read, so the influence of this feature may be restricted to these extreme cases.

For missing responses, the effect was found at the mid- to high-end of the mark range. This is in line with previous research (Bramley, 2009; Curcin et al., 2019). This is of concern, again, because the holistic context makes it a hidden bias. Why judges should be more negatively influenced by a missing response than an incorrect answer is an interesting question. When viewing a script, the presence of missing responses is immediately apparent to a judge and, thus, could be treated as a quick differentiator of quality. A number of “gaps” in a script may suggest gaps in a student’s knowledge, perhaps more so than a number of incorrect answers. There may be some influence of an incorrect answer suggesting that the students had tried to answer. These explanations are speculative and would need investigation.

Both handwriting and missing responses were directly mentioned by the judges, and some of the judges offered strategies to reduce any influence. In the case of handwriting, the strategy was to try and ignore it; in the case of missing responses, it was to attempt to balance the missing responses and content. In CJ, unlike marking, there is no audit trail of decision-making, so the influence of these features is not apparent and cannot be corrected after the event. Thus, judges attending to superficial or construct-irrelevant features are a threat to the validity of the CJ standard maintaining process and could compromise outcomes. In this context, however, there is scope to mitigate any effect.

Practical solutions for standard maintaining would be to (i) avoid using scripts with lots of missing responses or with hard-to-read handwriting or (ii) confirm that the scripts selected are representative of all scripts on the same mark in these respects. Scripts with many missing responses could be identified programmatically; however, handwriting would require visual inspection.

The observation and survey data indicated that the majority of the features attended to were based on construct-relevant features, e.g., whether a question was answered, the use of terminology or keywords, the use of supporting examples, etc. We found that the judges generally did not attend to other construct-irrelevant features, which is reassuring. Two other features were mentioned: (i) the examination technique, the presence of which was seen as a positive, and (ii) writing in sentences, which was noted as something to look for. The use of either was not widespread.

As noted earlier, in holistic decision-making, judges decide what constitutes good quality, and this conceptualisation determines their rank order of the scripts. The “use of CJ is built on the claim that rooting the final rank order in the shared consensus across judges adds to its validity” (van Daal et al., 2019, p. 3). This shared consensus is more than agreement; it is about a “shared conceptualisation” of what they are judging as the “judges’ collective expertise defines the final rank order” (p.3). The judge statistics indicated that the judges did achieve consensus, but was it an appropriate consensus? Consensus is good if an appropriate range of aspects are considered, but less so if judges focus on a narrow range of, or incorrect, features.

In our experiment, we observed the judges, so we know what features and strategies they reportedly attended to, which, typically, we would not do. While we anticipate that the judges will use their knowledge of the assessment and their marking experience to make their judgements (Whitehouse, 2012), the use of CJ does place a lot of faith in the judges judging how we expect or would like them to. Without adequate training, we cannot make this assumption, particularly in the standard maintaining scenario where we are expecting the judges to set aside their many years of marking practice and potentially apply a new technique.

It is recommended that judges have training on making CJ decisions that involves practice, feedback, and discussion. Training on awareness of construct-irrelevant features could be introduced. However, it would need to be implemented cautiously and tested to ensure that judges do not overcompensate and cause problems in the other direction. In terms of future research activities, it is recommended that researchers meet with judges before a study to explain the rationale and ensure that judges know what is expected of them. Practice activities would also be useful. For CJ more generally, while previous research (e.g., Heldsinger and Humphry, 2010; Tarricone and Newhouse, 2016) has cited the small amount of training needed as one of the advantages of CJ; this study shows that it might be time to revisit the topic.

As training was a key recommendation, it would be valuable to both replicate this study and explore these findings further in studies where training on how to make holistic decisions was given to judges. As appearance and SPaG seemed not to influence judges, research attention could be directed to handwriting and missing responses, and this would give more freedom in qualification selection as papers that directly assessed SPaG could be included.

While this study was set in a specific standard maintaining context involving cognitively demanding judgements, there are applications to a wider CJ context. Particularly, the lack of influence of SPaG and appearance features – that these were shown not to have an effect in this highly demanding context should be reassuring for other assessment contexts in which these features do not form part of the assessment construct. For handwriting and missing responses, where the option exists to include/exclude scripts, hard-to-read scripts or scripts with missing responses, could be avoided.

Before concluding, it is important to note some limitations of the study. First, the number of scripts in each feature category was quite small at only 10, meaning the power to detect a difference between the variants was quite low. However, despite this, differences were detected. Second, the scripts were selected or constructed to exemplify particular features so they could be considered to be less typical or perhaps “problematic.” Thus, these results hold for stronger instances of the features in question, and a less striking instance of the feature may have less or no effect.

This study contributes to existing research, both on which aspects guide judges’ decisions when using CJ and on the impact of judges attending to construct-irrelevant features. In summary, the study did reveal some concerns regarding the validity of using CJ as a method of standard maintaining. This was with respect to judges focusing on superficial, construct-irrelevant features, namely, handwriting and missing responses. These findings are not necessarily a threat to the use of CJ in standard maintaining, as with careful consideration of the scripts and appropriate training, these can potentially be overcome.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because open access consent was not obtained. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to LC, THVjeS5jaGFtYmVyc0BjYW1icmlkZ2Uub3Jn.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

LC and EC contributed to conception, design, and set up of the study. LC performed the statistical and qualitative analysis and wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the 40 volunteers who rewrote the candidate scripts.

Footnotes

- ^ Examination script is the term used to denote a candidate’s question responses contained in answer sheets or an answer booklet.

- ^ SPaG is part of the assessed construct for some qualifications but not for the qualification used for this study.

- ^ This can be done using the R package Plackett-Luce (Turner et al., 2020).

References

Baird, J. A. (1998). What’s in a name? Experiments with blind marking in a-level examinations. Educ. Res. 40, 191–202. doi: 10.1080/0013188980400207

Benton, T., Cunningham, E., Hughes, S., and Leech, T. (2020a). Comparing the Simplified Pairs Method of Standard Maintaining to Statistical Equating Cambridge Assessment Research Report. Cambridge: Cambridge Assessment.

Benton, T., Leech, T., and Hughes, S. (2020b). Does Comparative Judgement of Scripts Provide an Effective Means of Maintaining Standards in Mathematics? Cambridge Assessment Research Report. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benton, T., Gill, T., Hughes, S., and Leech, T. (2022). A Summary of OCR’s Pilots of the use of Comparative Judgement in Setting Grade Boundaries. Research Matters: A Cambridge University Press & Assessment Publication, 33. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10–30.

Black, B., Suto, I., and Bramley, T. (2011). The interrelations of features of questions, mark schemes and examinee responses and their impact upon marker agreement. Assess. Educ. 18, 295–318. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2011.555328

Bradley, R. A., and Terry, M. E. (1952). Rank analysis of incomplete block designs: I. The method of paired comparisons. Biometrika 39, 324–345. doi: 10.2307/2334029

Bramley, T. (2007). “Paired comparison methods,” in Techniques for Monitoring the Comparability of Examination Standards, eds P. Newton, J. Baird, H. Goldstein, H. Patrick, and P. Tymms (London: QCA), 246–300.

Bramley, T. (2009). “The effect of manipulating features of examinees’ scripts on their perceived quality,” in Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association for Educational Assessment–Europe (AEA-Europe), Malta.

Chase, C. I. (1983). Essay test scores and reading difficulty. J. Educ. Meas. 20, 293–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3984.1983.tb00207.x

Craig, D. A. (2001). Handwriting Legibility and Word-Processing in Assessing Rater Reliability. Master’s thesis. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois.

Crisp, V. (2013). Criteria, comparison and past experiences: how do teachers make judgements when marking coursework? Assess. Educ. 20, 127–144. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2012.741059

Curcin, M., Howard, E., Sully, K., and Black, B. (2019). Improving Awarding: 2018/2019 Pilots. Coventry: Ofqual.

Davies, B., Alcock, L., and Jones, I. (2021). What do mathematicians mean by proof? A comparative-judgement study of students’ and mathematicians’ views. J. Math. Behav. 61:100824. doi: 10.1016/j.jmathb.2020.100824

Heldsinger, S., and Humphry, S. (2010). Using the method of pairwise comparison to obtain reliable teacher assessments. Aust. Educ. Res. 37, 1–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03216919

Lesterhuis, M., van Daal, T., Van Gasse, R., Coertjens, L., Donche, V., and De Maeyer, S. (2018). When teachers compare argumentative texts. Decisions informed by multiple complex aspects of text quality. L1 Educ. Stud. Lang. Lit. 18, 1–22. doi: 10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.01.02

Linacre, J. M. (2002). What do infit and outfit, mean-square and standardized mean? Rasch Meas. Trans. 16:878.

Massey, A. (1983). The effects of handwriting and other incidental variables on GCE ‘A’ level marks in English literature. Educ. Rev. 35, 45–50. doi: 10.1080/0013191830350105

Meadows, M., and Billington, L. (2005). A Review of the Literature on Marking Reliability. London: National Assessment Agency.

Messick, S. (1989). Meaning and values in test validation: the science and ethics of assessment. Educ. Res. 18, 5–11. doi: 10.3102/0013189X018002005

Plackett, R. L. (1975). The analysis of permutations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 24, 193–202. doi: 10.2307/2346567

Pollitt, A. (2012b). The method of adaptive comparative judgement. Assess. Educ. 19, 281–300. doi: 10.1080/0969594x.2012.665354

Pollitt, A., and Crisp, V. (2004). “Could comparative judgements of script quality replace traditional marking and improve the validity of exam questions?,” in Proceedings of the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Manchester.

Shaw, S., Crisp, V., and Johnson, N. (2012). A framework for evidencing assessment validity in large-scale, high-stakes international examinations. Assess. Educ. 19, 159–176. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2011.563356

Stewart, M. F., and Grobe, C. H. (1979). Syntactic maturity, mechanics of writing, and teachers’ quality ratings. Res. Teac. English 13, 207–215.

Suto, I., and Novaković, N. (2012). An exploration of the examination script features that most influence expert judgements in three methods of evaluating script quality. Assess. Educ. 19, 301–320. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2011.592971

Tarricone, P., and Newhouse, C. P. (2016). Using comparative judgement and online technologies in the assessment and measurement of creative performance and capability. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 13:16. doi: 10.1186/s41239-016-0018-x

Turner, H. L., van Etten, J., Firth, D., and Kosmidis, I. (2020). Modelling rankings in R: the plackett-luce package. Comput. Stat. 35, 1027–1057. doi: 10.1007/s00180-020-00959-3

van Daal, T., Lesterhuis, M., Coertjens, L., Donche, V., and De Maeyer, S. (2019). Validity of comparative judgement to assess academic writing: examining implications of its holistic character and building on a shared consensus. Assess. Educ. 26, 59–74. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2016.1253542

Verhavert, S., Bouwer, R., Donche, V., and De Maeyer, S. (2019). A meta-analysis on the reliability of comparative judgement. Assess. Educ. 26, 541–562. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1602027

Whitehouse, C. (2012). Testing the Validity of Judgements about Geography Essays Using the Adaptive Comparative Judgement Method. Manchester: AQA Centre for Education Research and Policy.

Keywords: comparative judgment, standard maintaining, construct-irrelevance, validity, assessment

Citation: Chambers L and Cunningham E (2022) Exploring the Validity of Comparative Judgement: Do Judges Attend to Construct-Irrelevant Features? Front. Educ. 7:802392. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.802392

Received: 26 October 2021; Accepted: 14 March 2022;

Published: 27 April 2022.

Edited by:

Marije Lesterhuis, Spaarne Gasthuis, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Niall Seery, Athlone Institute of Technology, IrelandBen Davies, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Chambers and Cunningham. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucy Chambers, THVjeS5DaGFtYmVyc0BDYW1icmlkZ2Uub3Jn

Lucy Chambers

Lucy Chambers Euan Cunningham

Euan Cunningham