- Department of French, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

This study investigates social identity as a potential psychological variable in second language education. Despite the fact that school plays a critical role in the formation of social identity for students, social identity has yet to be studied across educational contexts. Thus, this study investigates social identity differences across three groups of learners enrolled in French as a second language programs in Ontario, Canada: core French, extended French and French immersion, to determine whether students’ membership in a particular language program influences their social identity. Sixty high school students registered in these programs completed a validated measure of social identity (i.e., Ingroup Identification Questionnaire) and answered several open-ended questions about student dynamics within and between French programs. Results confirm that there are statistically significant differences in social identity between all programs. Findings suggest that French immersion students have the highest level of social identity associated with their French program, followed by extended French and lastly, by core French students. This corresponds to the amount of class time that students spend in program-specific classes with their same-program peers. Qualitative findings suggest that French immersion and extended French students are aware of ingroup-behavior, experience a bond with their same-program peers and, in some cases, perceive a division with students enrolled in other programs, while the same is not true for core French students. These dynamics between students enrolled in different French programs provide further evidence for the formation of education program-based social identities. This is one of the few studies to measure social identity in educational settings and the first study to compare the social identities of second language learners. Its findings may be used to help future studies examine group-level behaviors resulting from social identity in various educational contexts and support social identity as a psychological variable that merits further attention in education research.

Introduction

This study seeks to introduce a new psychological variable, namely social identity, to studies of second language (L2) acquisition that may account for variability across learner groups. This variable refers to individuals’ self-identifications with social groups across various social contexts (e.g., Reay, 2010; Reicher et al., 2010; Ehala, 2018) and has potential implications for group-level perceptions, attitudes and behaviors (Hogg, 2018). While social identity has been largely studied in the field of social psychology, typically focusing on ethnicity, gender, social class and sexuality identities, it has rarely been examined in education-related contexts and has never been considered in L2 acquisition. That being said, it is widely accepted that school plays a critical role in the formation of a context-specific social identity, as students create an image for themselves to be perceived by both teachers and other students (Reay, 2010). Furthermore, L2 acquisition is a field that is strongly marked by interlearner variability (e.g., Dörnyei, 2009).

To explore whether social identity may be a relevant factor in the L2 acquisition of classroom learners, we investigate the strength of individuals’ social identities associated with their L2 education group. This is not typically done in studies of social psychology, which primarily focus on the role of social identity in established macro-scale societal groups (e.g., gender, ethnicity) and thus, do not require a measure of social identity as individuals either fit the inclusionary criteria or they do not. More recently, studies have begun to use questionnaires to evaluate individuals’ level of identification (i.e., ingroup identification; Cameron, 2004) with a larger variety of social groups (e.g., crowds, corporate organizations, electorates; Reicher et al., 2010). Accordingly, the present study will make use of a validated questionnaire to assess the strength of individuals’ self-categorizations in L2 education-related social groups to investigate potential differences in social identity due to learning context.

The current study explores whether high school students associate themselves with particular social groups based on their language learning program. We compare the strength of the social identity of students enrolled in different French as a second language (FSL) programs in Canadian high schools. These students were selected as the populations of study due to their learner profiles: these are students of similar ages and backgrounds, enrolled in the same schools, whose educational contexts vary only by the French program in which they are enrolled. This will allow us to determine whether students in certain high school programs have higher levels of social identity than others. This work will provide an important first step for studies investigating social identity as a factor in language education. Such findings would also offer significant insights in the field of education more generally and may encourage the investigation of social identity as a potential underlying influence on classroom and language learning as social identity has the potential to serve as an explanation for group-level phenomena.

Social Identity: Background

Social identity refers to an individual’s identification with a particular social group paired with the emotional significance that they ascribe to that group and results in a shared sense of belonging between members of the same social group (Reicher et al., 2010). According to Hogg et al. (2004), a social group consists of two or more people who “identify themselves in the same way and have the same definition of who they are, what attributes they have and how they relate to and differ from specific outgroups” (p. 251). Other studies of social group membership propose that individuals within a social group must be bonded in some way (Royce, 2007), typically by individuals’ real-word experiences (Ehala, 2018). Therefore, individual relationships are required for the formation and internalization of social identity (Dunbar, 1993) and direct, ongoing social interaction between members is crucial for social identity formation (Moreland and Levine, 2003). We would thus expect groups like sports teams, immediate family, workers in the same office and students in the same class to constitute social groups due to their interaction and shared real-world experience (Royce, 2007).

Social groups have shown to reinforce individuals’ self-enhancement and self-esteem (Rubin and Hewstone, 1998; Hogg et al., 2004). Indeed, ingroup membership (i.e., social identity) may alleviate individuals’ feelings of uncertainty about themselves and their identity, thereby increasing their self-esteem (Hogg, 2012). Moreover, individuals promote their own group membership as they amplify the positive qualities of their ingroup over the outgroup which leads to feelings of superiority over non-members (i.e., positive distinctiveness; Brewer, 1991; Leonardelli et al., 2010). This also allows individuals to take on the prestige and value of groups to which they belong (Hogg, 2018).

The Social Identity Perspective

The social identity perspective has become the dominant framework for studies of group processes in psychology due to its generality and potential applications to numerous fields of study (Dumont and Louw, 2009). It is composed of Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1979) and Self-categorization Theory (SCT; Turner et al., 1987) which offer insights into the formation of social groups. SIT is a psychological framework that allows for the investigation of how individuals define themselves as members of a social group and the potential implications of social group membership on group-level perceptions, attitudes, behaviors, and communication. This theory suggests that all individuals categorize themselves into meaningful social groups, which results in group-level behaviors (Jenkins, 2014). At the core of SIT is the notion that individuals have any number of self-constructed personal and social identities, the former being based on personal attributes and intimate relationships (e.g., mother, friend), while the latter are based on common attributes with people who share a social category (e.g., players on a soccer team, students in the same program).

To expand on how social categorizations of the self and others are formed, Turner et al. (1987) put forward SCT. This theory maintains that individuals are organized into social groups based on the notions of accessibility and fit. Accessibility of a particular social group is determined by its perceptual salience and perceived importance, which are increased if the group has prior meaning or significance (i.e., if it was already recognizable). The second notion, fit, is based on the shared similarities of social group members and their perceived differences with outgroup members (Hogg et al., 2004). According to SCT, only one of an individual’s identities may be psychologically active at a particular moment in time and individuals identify with their most salient group membership for the given social context (Reicher et al., 2010). For example, although a student may have very strong religious, gender and ethnic identities, in the context of a classroom, their most salient social identity may be that of a student.

Hogg (2012) explains that according to the social identity perspective, social groups are internalized as group prototypes (i.e., a collection of attributes that capture group-level similarities and outgroup differences) which lead individuals to perceive increased cohesion and structure within their social groups and to accentuate their own similarities to the ingroup protype if the identities are salient. These prototypes can have implications for group-level phenomena, as individuals create group norms such as behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes (Hogg, 2018) which become synonymous with group prototypes (Turner, 1991). Group members then begin to conform to the ingroup norms, that is, they assimilate to the prototype (Turner, 1985; Turner and Oakes, 1989; Abrams and Hogg, 1990). Generally, prototypical behaviors of ingroup membership serve two primary purposes: they (i) identify members of the ingroup and (ii) differentiate members of the outgroup, particularly if the difference between these groups is socially prominent (e.g., Abrams et al., 1990). Thus, we should observe distinct behaviors between related social groups with strong oppositions.

Social Identity in Educational Contexts

Social identity may prove to be particularly salient in classroom contexts due to institutional and program organization as well as factors pertaining to adolescence such as self-esteem and social importance. School presents the first occasions in which individuals engage and deal with public context and social differences (Reay, 2010). Researchers maintain that the organized network of recognizable roles (Jenkins, 2014), the practical knowledge about social positions (MacKinnon and Heise, 2010) and relationships with teachers and their peers (Perry, 2002) within school contexts help students develop a sense of self and identity. Secondary students in particular are at a key stage in their development of identity (McLeod, 2000) as these students are still developing both their personal and social identities, both implicitly and explicitly, and, as such, these processes are on-going. During this period, individuals experience a decline in self-esteem, possibly due to (i) the emotional, physical and hormonal changes that accompany the adolescent experience (McLeod, 2000) and (ii) their greater awareness of the discrepancy between the personal qualities and attributes that they have and those that they would like to possess (Harter, 2012). Harter (2012) discovered that, during the period of middle adolescence (i.e., ages 14–16), individuals’ relationship self-esteem with their classmates is the most predictive factor of their global self-esteem. A possible explanation for this is that students value their social identity above their personal identity, even in situations that focus on the individual (Reay, 2010). Therefore, if a student has high relationship self-esteem, it may increase the individual’s global self-esteem. As such, adolescent students may place greater emotional significance on their social identities than other individuals. Despite these factors, studies of social identity do not consider classroom factors such as institutional practices, composition of the peer group or social interaction between students and teachers (Reay, 2010). As such, the present study investigates the social identity of high school students enrolled in three distinct FSL programs. We propose that students’ FSL programs will serve as social categorizations delimited by the educational contexts. These programs classify students into established categories which increases the likelihood that individuals’ social identity will become consequential (Jenkins, 2014). Thus, we hypothesize that students may assign weight to their FSL program categorization and internalize their membership in a specific FSL program as a social identity.

Canadian French as a Second Language Programs

In Canada, French and English have equal status as official languages. Thus, elementary and secondary students in Anglophone communities must complete a minimum number of hours of French instruction. This study compares the social identity of students enrolled in three FSL programs–core French, extended French and French immersion–offered by the Ministry of Education in Ontario. These formal language learning programs are offered in English-majority communities and are open to all students. In these programs, students take French classes with their same-program peers and they do not typically use French outside of class time (Genesee, 1978). The same teachers are typically the instructors for all FSL programs offered by a given school.

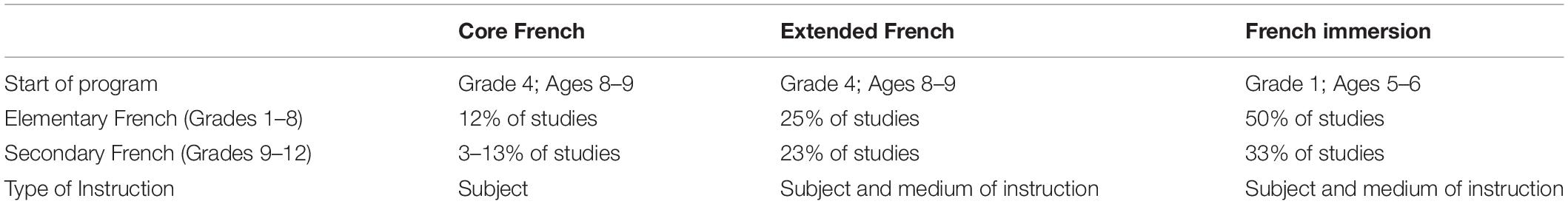

The differences between these programs are first and foremost related to French instruction. First, there are differences in the age at which the programs begin: French immersion programs begin in Grade 11 while core French and extended French programs both begin in Grade 4. Once the program begins, students only take classes with students in their FSL cohort until the end of elementary school. It is only in high school (beginning in Grade 9) that students of all FSL programs begin to take courses with students outside of their FSL cohort. Second, there are major differences in the proportion of studies that students complete in French; with students in core French programs completing the smallest proportion of their studies in French, followed by students in extended French programs and lastly, by French immersion students who complete the largest proportion of their studies in French (see Table 1 for details). In addition to differences in the amount of French instruction, there are also differences in the type of French instruction. For core French students, all FSL class time corresponds to French language classes in which students study French as an academic subject. While both extended French and French immersion students also take French as a subject throughout their education, these programs also use the French language as a medium of instruction for other academic subjects (e.g., science, geography, history). Overall, French immersion students begin their program at the youngest age and complete the largest proportion of their studies in French. Core and extended French students begin their programs at the same time (Grade 4); however, extended French students have a greater exposure to French than core French students through an increased proportion of French studies and exposure to a variety of academic subjects taught in French. A summary of these differences is presented in Table 1. The differences in French instruction across FSL programs may give certain groups of students more time to associate themselves with their FSL group and to assign importance to their FSL membership. Thus, we may observe that the strength of students’ social identities correlates with the time spent in the FSL classroom.

In addition to differences in French instruction, there are some dissimilarities between programs which may influence students’ identification with their particular program and their peers. First, it should be noted that parents must choose to register their children in extended French and French immersion programs at the time of registration (Grade 1 for French immersion; Grade 4 for extended French) as they offer supplementary French in addition to the amount of French instruction mandated by the Canadian government. Moreover, French immersion and extended French programs are not typically offered in the same schools, whereas many public schools will offer core French and one of either French immersion or extended French programs. Contrarily, core French programs provide the required amount of French instruction to students and do not require additional registration. These differences may lead to a greater awareness of the labels of “French immersion” or “extended French” for students registered in those programs than to the label of “core French” for the program’s students.

Moreover, the differences in FSL program structure mean that students spend more time with their same-program peers than other students throughout their education. This may lead to perceived divisions between programs either (1) physically due to differences in schedules and FSL courses or (2) socially due to the development of friendships and increased familiarity between members of the same program. In both cases, students’ time spent with their same-program peers may contribute to the formation of social identity; through distancing themselves from the outgroup and increasing the emotional significance of the ingroup, respectively. According to SIT, this may in turn increase students’ self-esteem and social importance derived from their FSL program membership. If so, we would expect French immersion students’ FSL experience, followed by that of extended French students, to be most strongly affected by their FSL peer group because these learners spend the most time within their FSL cohorts throughout their education.

While differences in (1) French instruction; (2) program registration, and (3) program structure do exist between these FSL programs, students enrolled in these programs are largely similar: they are the same age; they attend the same schools; they take the same courses; and they are taught by the same teachers. This provides an interesting context for the current investigation, as differences in social identity between groups should be linked to program-level differences. We thus propose that high school students in each of the three distinct FSL programs will have internalized their position in their FSL program as a social categorization based on the school context. According to SIT, because these FSL categorizations distinguish related social groups with clear demarcations, members of these FSL social groups may be characterized by distinct behaviors (e.g., attitudes, behaviors, perspectives) as students attempt to create positive distinctiveness or distinguish themselves from members of other FSL programs.

Current Study

The current study surveyed learners enrolled in three different high school FSL programs: core French, extended French and French immersion to determine whether differences between these programs influence students’ social identities associated with their FSL group membership. This section begins by presenting the two primary research questions investigated along with their corresponding hypotheses. Next, it introduces the participant groups of study. Lastly, it describes the data collection protocols.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The first research question is related to our assumption that students enrolled in different FSL programs have different levels of social identity associated with their FSL group membership due to differences across the programs of study. It seeks to test the hypothesis that there will be differences in the strength of individuals’ social identities associated with their FSL program membership based on the program in which they are enrolled—core French, extended French or French immersion. We predict that students enrolled in these programs will indeed report differences in social identity due to program-level differences in French instruction, registration and structure (Hypothesis 1). Such differences could contribute to any number of program-specific social dynamics as they may influence the development of friendships and familiarity between students enrolled in the same program as well as feelings of self-esteem and positive distinctiveness derived from students’ particular program. Specifically, we predict that French immersion students will report the highest level of social identity of the three FSL groups, followed by extended French students and lastly, by core French students (Hypothesis 2). In line with the definition of social identity put forward by SIT, French immersion programs should provide students with the greatest (1) knowledge of their social group, through purposeful registration in the program as well as time spent in the FSL classroom and (2) emotional significance of the social group, as they spend the greatest amount of time in the FSL classroom with their same-program peers and the least amount of time with students outside their FSL program which may contribute to increased familiarity and cohesion within the FSL ingroup.

The second research question is more exploratory in nature and seeks to provide insight into how the structural differences between programs (e.g., amount and type of French instruction, age at program onset) may influence the social dynamics within and across FSL programs in the same school. These findings will provide insight into whether students in certain programs are more likely to identify with members of their ingroup or differentiate themselves from members of the outgroup. Here, we hypothesize that French immersion students’ comments, followed by those of the extended French students, will reflect a greater awareness of an FSL social group and a greater emotional investment in their FSL program membership than core French students because of differences in program structure (see Table 1) and time spent with their same-program peers (Hypothesis 3). We would expect that comments from student groups reporting higher levels of social identity would reflect self-esteem derived from the program as well as positive distinctiveness through attempts to distinguish themselves from the other FSL groups by amplifying the positive characteristics of the ingroup and perhaps, criticizing characteristics of the outgroups. The analysis of within- and between-program social dynamics will provide greater insight into students’ relationships which may, in turn, help account for any observed differences in social identity between FSL programs.

Participants Groups

This study includes data from 60 Grade 12 high school students enrolled in one of three FSL programs: core French (n = 17; 16 females, 3 males; mean age: 17.4 years), extended French (n = 19; 7 females, 9 males; mean age: 17.6 years) and French immersion (n = 24; 15 females, 9 males; mean age: 17.3 years).2 Participants were recruited at public high schools in the Greater Toronto, Ontario Area. They were asked to participate voluntarily and were compensated $5 CDN for their participation. All participants completed the entirety of their elementary and secondary studies in Ontario, Canada and reported having first learned French in an educational context.

Ingroup Identification Questionnaire

The section presents the measure of social identity selected for the present study. As we are inscribing our work within the social identity perspective, we must consider individuals’ social identities to be part of their self-concepts (Tajfel, 1978) and consider SIT’s two-pronged definition of social identity as both “the knowledge of [one’s] membership in a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel, 1978, p. 63). Accordingly, for the current study, we selected the multicomponent ingroup identification questionnaire developed by Leach et al. (2008; see Appendix) to measure participants’ self-categorization as members of their high school French program. In line with the social identity perspective, this measure of ingroup identification (i.e., social identity) targets both (1) the knowledge of group membership as well as (2) the value and emotional significance of said membership along two constructs: group-level self-definition and group-level self-investment. The former equates to individuals’ definition for their place in society through self-categorizations and is assessed with questions targeting: (1) individual self-stereotyping, that is, the degree to which individuals perceive themselves as similar to, and having things in common with, average ingroup members (e.g., “I have a lot in common with the average [Ingroup] person.”) and (2) ingroup homogeneity or the degree to which individuals view their entire ingroup as sharing commonalities that make the group relatively homogeneous (e.g., “[Ingroup] people have a lot in common with each other.”). The latter reflects individuals’ emotional investment and subjective salience of the social group by targeting: (1) satisfaction, defined as an individual’s positive feelings about group membership (e.g., “I think that [Ingroup] have a lot to be proud of.”); (2) solidarity, or an individual’s degree of psychological and behavioral commitment to the ingroup (e.g., “I feel committed to [Ingroup].”); and (3) centrality, the degree of salience and importance of an individual’s ingroup membership (e.g., “The fact that I am [Ingroup] is an important part of my identity.”).

As there has been little agreement about how social identity should be conceptualized and measured, Leach et al. (2008) conducted several studies to validate their ingroup identification questionnaire as a measure of social identity. The authors first used confirmatory factor analysis to validate the proposed two-construct model of social identity consisting of (1) group-level self-definition and (2) group-level self-investment across three social identities (national, supranational, and university). Next, they demonstrated the construct validity of the components of each construct by examining their correlations with established measures of ingroup identification (e.g., Luhtanen and Crocker, 1992; Sellers et al., 1998; Ellemers et al., 1999; Jackson, 2002; Cameron, 2004). Lastly the authors, established the predictive validity of the questionnaire results on intergroup orientations (e.g., perceived differences between groups). Results were more consistent with the ingroup identification questionnaire than with any measure of social identity previously described in the research.

The questionnaire consisted of fourteen Likert scale items assessed along a 7-point scale that ranged from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” Items were made to refer specifically to students’ FSL program as the ingroup of interest (e.g., Original statement: “I have a lot in common with the average [Ingroup] person.”; revised: “I have a lot in common with the average person in my French program.”). Each item related to one of the two constructs: (i) group-level self-definition which measured the degree to which individuals associated themselves with their FSL ingroup (e.g., four questions including I have a lot in common with many students in my French program) or (ii) group-level self-investment which targeted the emotional and psychological significance of individuals’ FSL group membership (e.g., 10 questions such as I feel a bond with students in my French program).

Data Collection Protocol

Data were collected via an online survey created using the tool eSurv.org. First, participants completed a questionnaire targeting basic biographical data (e.g., age, province where they attended school) as well as their language learning backgrounds (e.g., where they first learned French) to assure that participants met the inclusionary criteria. Next, participants completed the adapted version of the Leach et al. (2008) ingroup identification questionnaire described above to evaluate their ingroup identification associated with their FSL program membership. Lastly, participants were asked three open-ended questions targeting their FSL program experience. Participants were first asked to answer “Yes,” “No,” or “I am not sure” to each of the three questions (e.g., Do you feel like students in your French program formed or acted like a group in any way?). They were then given the opportunity to support their response with a long answer. These questions sought to investigate possible ingroup attitudes or behaviors of students within and outside their FSL program that may provide insight into students’ social identities. The survey took approximately 12 min to complete.

Results

This section begins by reporting the results of the ingroup identification questionnaire: first, for the group-level self-definition construct, followed by the results for the group-level self-investment construct. We then present the results of the open-ended questions. Throughout the results sections we will use the acronyms CF (i.e., core French), EF (i.e., extended French) and FI (i.e., French immersion) to avoid repetition of the three labels.

Ingroup Identification Questionnaire

Group-Level Self-Definition

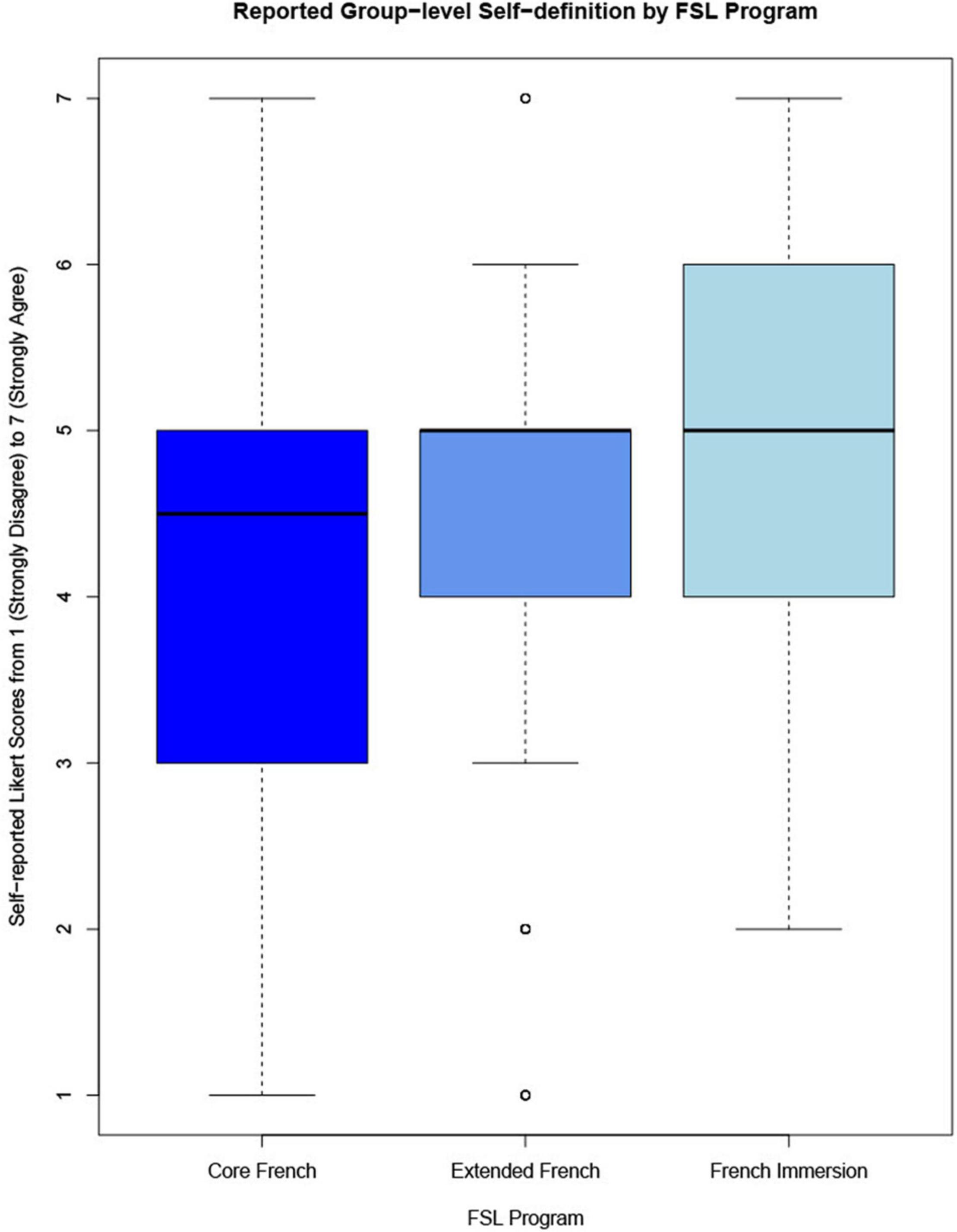

Recall that group-level self-definition reflects the degree to which individuals define themselves as members of a particular ingroup. In the case of our French learners, we hypothesized that the three student groups would report different levels of social identity due to the differences across FSL programs (i.e., instruction, registration, structure; Hypothesis 1). We further predicted that FI students would report the highest levels of social identity as we expected this group to have the greatest knowledge of their social group due to the combination of earliest age at onset of the program and purposeful registration in said program as well as most time spent in the FSL classroom and least amount of time spent with students outside their program of all FSL groups (Hypothesis 2). The results of the group-level self-definition construct (α = 0.85) for the three student groups are displayed in Figure 1. This boxplot displays the reported Likert scores from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree) for participants in CF, EF, and FI programs.

Figure 1. Reported likert scores for questions 11–14 targeting group-level self-definition by FSL program.

When reporting agreement with questionnaire items associated with group-level self-definition, CF students reported a median Likert score of 4.5,3 the lowest of the three groups. EF and FI students both reported a median Likert score of 5 (Somewhat agree). Results of a Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared test revealed that there were statistically significant differences between at least two of the groups (p = 0.01). Dunn’s multiple comparison test then determined that, while the results of the EF group did not statistically differ from either the CF (p = 0.34) or the FI group (p = 0.10), the differences in median scores between CF and FI groups were statistically significant (p = 0.015). The score most often reported for questions targeting self-definition was 5 (Somewhat agree) for both CF (N = 20) and EF (N = 31) participants, whereas the mode for the FI participants was slightly higher at 6 (Agree; N = 37). Figure 1 depicts visible differences in the distribution of scores between all groups. Overall, we see that, along with higher median scores, FI, followed by EF scores tend toward higher levels of agreement than CF scores. Indeed, 71% of FI students reported a level of agreement from 5 (Somewhat agree) to 7 (Strongly agree). In comparison, 64% of EF and 50% of CF participants reported such levels of agreement. Additionally, the scores of the EF student group were the most homogeneous overall, with scores that were concentrated between 4 (Neither agree nor disagree) and 5 (Somewhat agree), despite the presence of a few outliers.

Group-Level Self-Investment

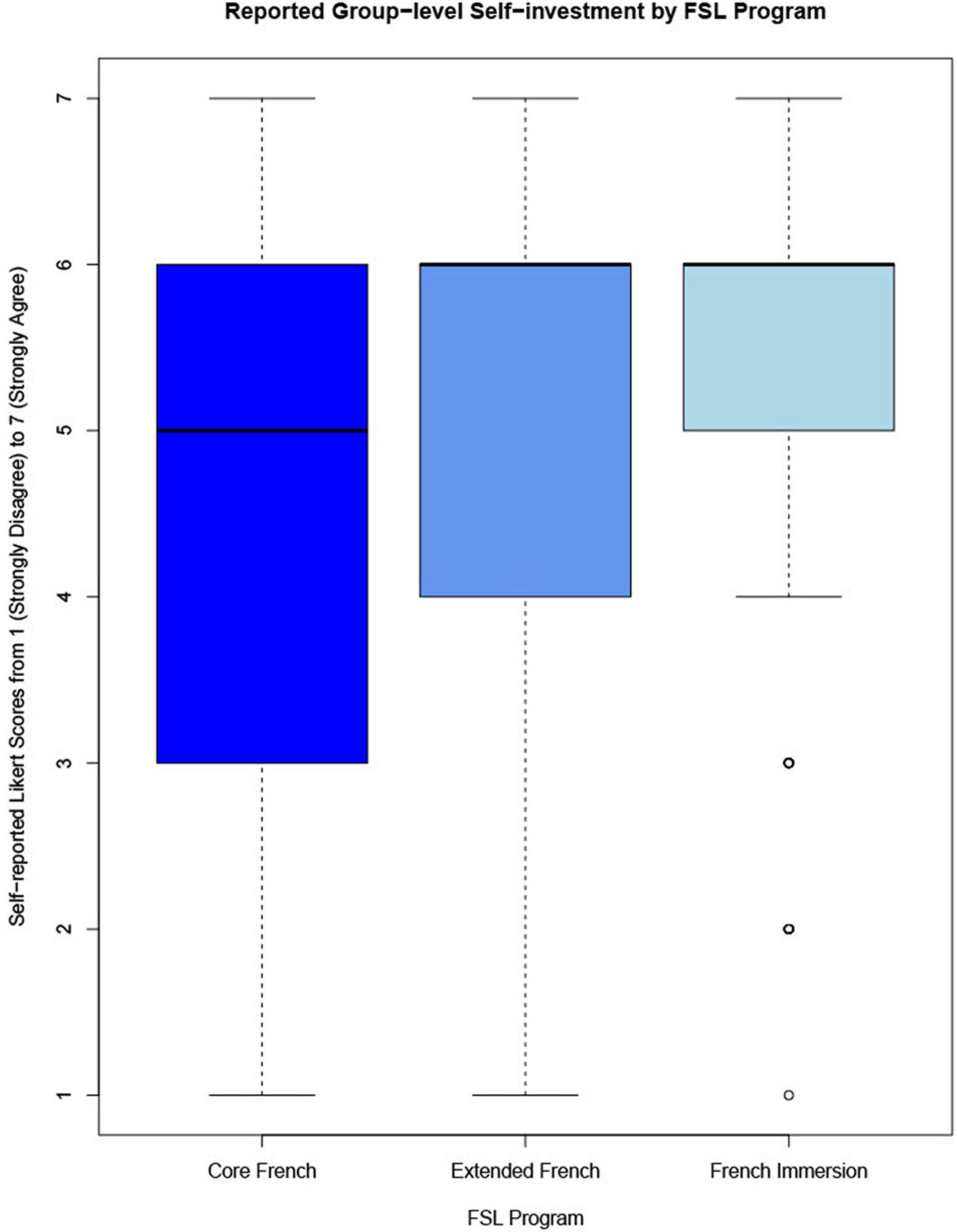

The group-level self-investment dimension reflects individuals’ psychological and emotional connection to their ingroup. Recall that we predicted that the three student groups would report differences in social identity (Hypothesis 1) with FI students reporting the highest levels of social identity, followed by EF students and lastly, by CF students (Hypothesis 2). With respect to differences in emotional connection to the ingroup, we predicted that French immersion students would have the greatest amount of familiarity and solidity with their same-program peers because they spend the greatest amount of time in the FSL classroom of the three FSL groups. Figure 2 presents the reported Likert scores for the questions targeting the self-investment construct (α = 0.91) for all student groups.

Figure 2. Reported likert scores for questions 1–10 targeting group-level self-identification by FSL program.

As with the group-level self-definition results, CF students reported the lowest level of agreement with group-level self-investment items with a median score of 5 (Somewhat agree). Once again, the EF and the FI students reported identical median scores of 6 (Agree), higher than that of the CF students. A Kruskal–Wallis chi-squared test signaled that there were statistically significant between-group differences (p < 0.001) and a Dunn multiple comparison test confirmed that differences in the median scores of all groups were statistically significant from one another (all differences p < 0.001). The dispersion of these results shows that the FI participants reported the most homogenous levels of agreement for this construct with scores ranging from 5 (Somewhat agree) to 6 (Agree). With the participants from both CF and EF groups, there was much more variability in the results with scores ranging from 3 (Somewhat disagree) to 6 (Agree) for CF participants and 4 (Neither agree nor disagree) to 6 (Agree) for EF participants.

Open-Ended Questions

In addition to the quantitative data obtained through the social identity questionnaire, we obtained supplementary qualitative data to support our analyses. This section presents the multiple-choice responses for each of the three questions as well as a representative selection of participant comments.

Question 1: Do/Did You Feel Like Students in Your French Program Formed or Acted Like a Group in Any Way? Explain

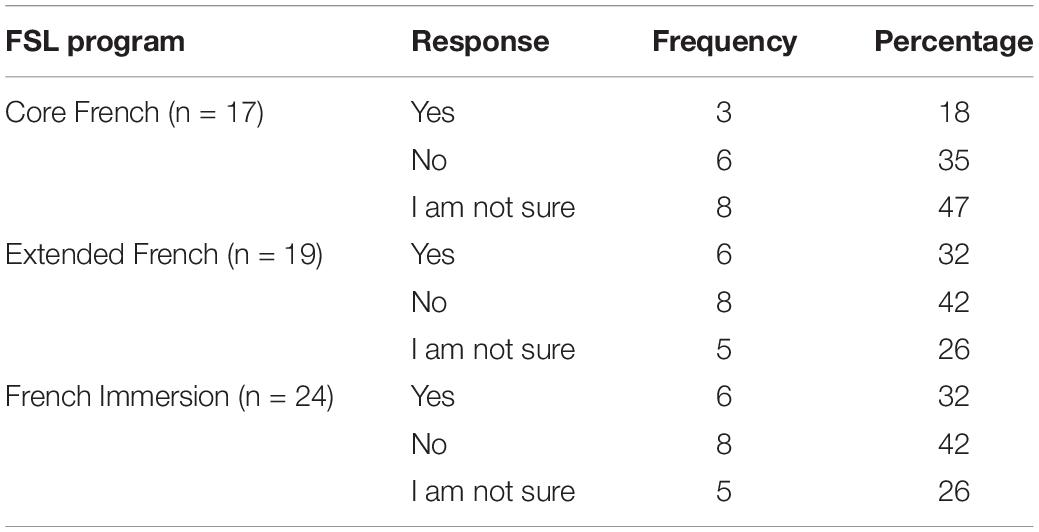

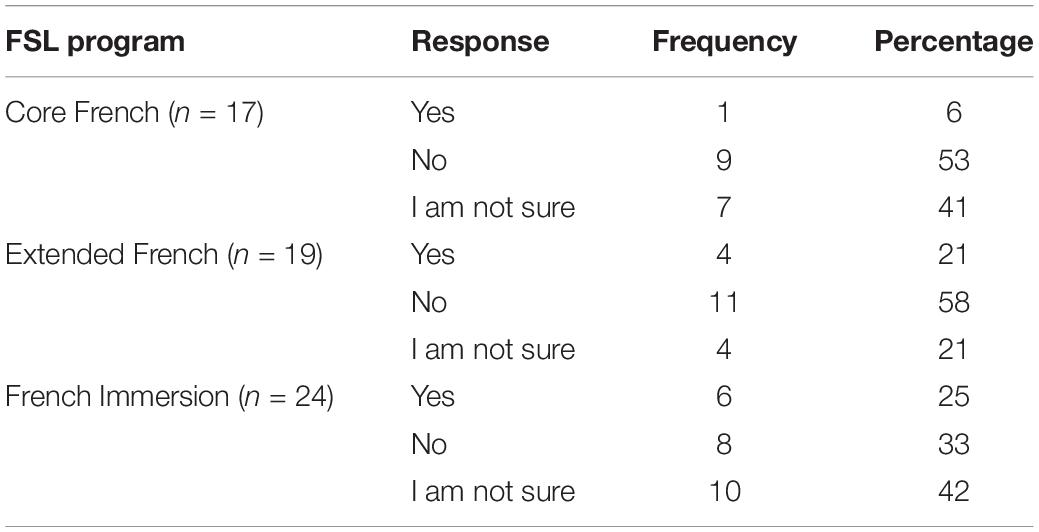

This question was selected to explore whether participants perceived the formation of an ingroup within their FSL program. Recall that SIT proposes that one aspect of social identity is the emotional significance of one’s social group membership. This question also seeks to target whether students perceive increased cohesion and similarities between the members of their own FSL group, which may reflect that students have internalized their FSL social group as a prototype. Table 2 provides participants’ multiple-choice responses to this question.

Table 2. Distribution of multiple-choice responses for question 1: Do you feel like students in your French program formed or acted like a group in any way?

As can be seen in Table 2, FI students reported the highest level (67%) of agreement with this statement, followed by EF participants (32%) then CF participants (18%). FI also had the lowest number of students respond “No” to this question with 8%, while EF and CF students reported higher negative response levels, with 42 and 35%, respectively. The percentage of students who reported uncertainty for this question was also relatively high for all groups, particularly for CF participants. A chi-square test (p < 0.001) confirmed that, according to Wei and Hu’s (2019) benchmark system,4 there was a medium level of association (Cramér’s V = 0.33) between students’ FSL program and their response to Question 1. A post hoc pairwise comparison determined that the FI responses differed statistically from both the CF (p = 0.018) and the EF (p = 0.031) groups, while there were no statistically significant differences between the CF and the EF groups (p = 0.39).

Several patterns emerge from participants’ explanations for their answers. Various individuals commented that students in their program formed a group because of a “bond.” For example, one FI student noted that “we had an exclusive bond that kids who weren’t in our program could not duplicate” (FI05). Another explained:

Most of the students in my high school immersion program have been in the same class/group since elementary school. We have created a strong bond and usually gravitate toward each other when in a group setting (or, for example, when we are placed in courses with a mix between [French immersion] and English students). (FI24).

A similar comment was also made by an EF student who said, “we had a special bond because we spent years together” (EF15). Notably, only students in FI and EF programs shared this sentiment—there was no mention of a bond or similar relationship in the CF responses.

Comments from the FI and EF participants suggest that size and duration of their FSL programs may contribute to a feeling of familiarity with their fellow group members and may encourage potential group behaviors. One participant described their FI program as “the exact same group for every class in French. Throughout the years this brought us closer together and although not everybody still talks to each other, the French program definitely formed many close friendships” (FI01). These ideas were echoed by other FI students (FI04, FI13, and FI23) who noted that students share many classes over the years and, because of this, feel “more accustomed to being around each other” (FI10) than other students. One EF participant also noted, “we’ve all been in school for so long and have many similar classes, it’s easy to remain friends” (EF19). The above comments reflect students’ perceptions that the program contributes to their friendships and familiarity with other students in their same FSL program.

A second factor that appears to further strengthen the bond between students enrolled in both FI and EF programs is a divide with so-called ‘‘English’’ (i.e., core French) students.5 Students in both of these programs noted this divide and cited it as the reason that “we were only usually friends with those in our group” (FI15) and that “French program students are usually in separate friend groups than those in the English classes” (EF10). There were also several notes that may indicate that this divide was purposeful. For example, one EF participant noted that “we always participated in activities together and did not allow English students to join” (EF11) and a FI participant said that “[we] were more inclined to differentiate ourselves from the English students because we were mocked by them” (FI09). These statements reflect that FI and EF participants categorized their same-program peers as members of their ingroup and students outside their FSL program as members of an outgroup.

The same cannot be said for students enrolled in CF programs who largely did not report that students in their program formed or acted like a group. Moreover, the majority of them did not provide an explanation for their response. No CF student mentioned a divide with students in any other FSL program. In fact, the only comment from a CF participant that supported the notion of a CF group stated that “since we are learning about French, we have something in common and therefore use each other’s help to learn the second language and get better at it” (CF09). This comment made reference to the shared goal of language learning as opposed to social group dynamics and was the only comment of this type from any speaker. This may reflect that CF students are less aware of group behavior within their program and instead perceive their FSL program as a means for learning French, attributing less social value to their program than do FI or EF students.

Question 2: Do/Did Students in Your French Program Act Differently From Other Students in Your Same Secondary School? Explain

This question was included to explore whether participants categorize groups of “us” and “them” between their FSL ingroup and students enrolled in other French programs at their same school and whether they associate any prototypical behaviors with either the in- or outgroup. Table 3 presents participants’ responses to this question. No statistical differences were found between the FSL groups (p = 0.26). In terms of absolute differences, FI participants had the largest proportion of “Yes” responses with 25%, followed by EF with 21% and lastly, by CF participants with 6%. FI had the lowest number of “No” responses with 33% followed by 53% of CF and 58% of EF participants.

Table 3. Distribution of multiple-choice responses for question 2: Do students in your French program act differently from other students in your same secondary school?

To explain their response to this question, participants tended to identify individual differences as distinguishing characteristics of different FSL groups; associating greater motivation, particularly academic motivation, and confidence with their FSL ingroup as compared to their peers outside their FSL program. For example, when describing their own FSL ingroup, FI students said that they were “more school centered” (FI02), “more confident” (FI11), “more motivated and [that they] work a bit harder” (FI13). Similarly, EF participants labeled their ingroup as “more school oriented” (EF15), “more outgoing” (EF13) and “on the more ambitious side when it comes to academic goals” (EF02). Interestingly, one FI participant also noted that “sometimes French [immersion] students feel superiority because they know how to speak French when others don’t and even if others learn, French [immersion] students will always have more experience” (FI07). This pattern of attributing positive characteristics to the ingroup over the outgroup was only observed in FI and EF participants. In contrast, the only comment by a CF participant served to negate the existence of behavioral differences between groups with the statement: “French is thought of as a subject one is taking. People don’t think they’re better or worse for taking French” (CF03). This contrasts strongly with the comments of FI and EF participants who indicated that students in these programs may derive positive self-esteem and feelings of superiority from their FSL group membership.

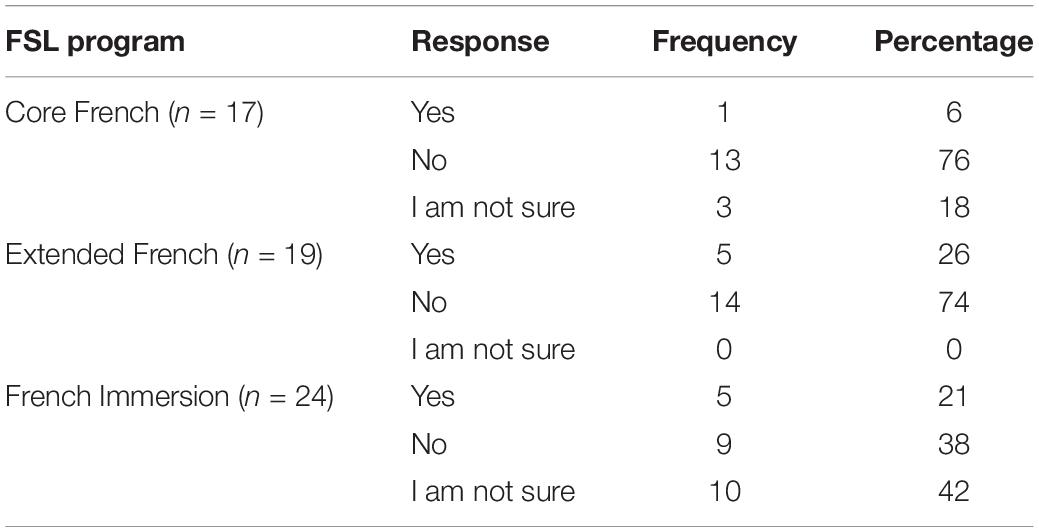

Question 3: Are/Were Students in French Programs Separated From Other Students in the Same School? Explain

This question was motivated by the notion that the program structure may lead students to perceive division between students of different FSL programs whether it be strictly physical (e.g., schedules, classes) or social (e.g., friend groups, familiarity, attitudes). Table 4 presents the percentage of responses to this question for each FSL group. EF reported the highest proportion of “Yes” responses with 26%, followed by FI with 21% and lastly, by CF with 6% of respondents. A chi-squared test found that there were statistically significant between-group differences (p = 0.006) exceeding Wei and Hu’s (2019) medium effect size benchmark (Cramér’s V = 0.34). Specifically, differences between the EF and the FI groups’ responses reached statistical significance (p = 0.015) while differences between the CF and the EF (p = 0.06) participant groups and the CF and the FI (p = 0.06) participant groups did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4. Distribution of multiple-choice responses for question 3: Are students in French programs separated from other students in the same school?

When commenting on a perceived division between students enrolled in different FSL programs, participants from all programs (CF14, EF08, EF15, FI02, FI05, and FI17) noted that students take different courses based on their program. There were also several participants from both EF and FI programs that repeated the notion of a separation with the “English” students, some of whom explained that a divide had existed in either elementary or middle school, but that it did not extend into high school. For example, EF participants noted that “in elementary school there was a great separation between extended French students and regular English students” (EF06) and “in middle school, there was a large divide between the core French and extended French students. In high school, this divide does not exist” (EF02). FI participants had similar comments, remarking: “in elementary yes, but in high school not so much because people start to care less about that divide” (FI15) and:

Yes, there was always a divide with the French students and English students. The French kids were always together so they felt like a group and the kids not in French immersion thought the French kids thought they were better than them. (FI23)

As they did when answering Questions 1 and 2, the CF participants’ responses patterned differently from those of the EF and the FI participants. No CF student explicitly described a separation, with one participant noting only that “They are a part of everything.” (CF03) which, though slightly ambiguous, seems to negate a potential separation and indicate that they perceive the FSL groups at their school to be integrated.

Discussion

In the field of applied linguistics, studies of individual differences often focus on non-psychological variables including L2 motivation (e.g., Masgoret and Gardener, 2003), aptitude (e.g., Li, 2016) and anxiety (e.g., Dewaele et al., 2017) while psychological variables remain under-studied. Researchers have begun to call for more systematic research into such factors in order to enhance the psychological profiles of language learners and generate pedagogical implications (e.g., Comanaru and Dewaele, 2015; Wei et al., 2020). Accordingly, the present study applies the work of Leach et al. (2008) to education research and contributes to our understanding of Canadian FSL learners as a population of study.

The results of our ingroup questionnaire confirm Hypothesis 1. There were statistically significant program-level differences in strength of reported social identity associated with FSL program membership. The results of the group-level self-definition construct (i.e., shared common identity) revealed differences between two out of the three FSL groups: core French and French immersion. For this construct, French immersion students reported higher levels of self-definition than the core French students, indicating that French immersion students perceive a shared ingroup identity more strongly than core French students. The results of the extended French group did not differ statistically from either group. Unlike the group-level self-definition results, the results of the group-level self-investment dimension, which reflects individuals’ emotional and psychological connection to their FSL ingroup, yielded statistically significant differences between all FSL student groups. Thus, confirming Hypothesis 1—there are differences in social identity across FSL programs, particularly as it concerns the emotional significance of the FSL programs to their ingroup members.

Moreover, the ingroup identification questionnaire provides evidence to confirm Hypothesis 2, which predicted that French immersion students would identify most strongly with their FSL group membership, followed by extended French students and then, by core French students. Indeed, French immersion students reported the highest ingroup identification scores overall, followed by extended French students and lastly, by core French students. This pattern was particularly clear with respect to the group-level self-investment results. This is perhaps unsurprising, as the primary differences between FSL programs (e.g., French instruction, time spent in the FSL classroom with FSL peers) seem to be more related to students’ emotional and psychological connection to the program (i.e., group-level self-investment) than to students’ awareness of the program and their particular FSL label (i.e., group-level self-definition). For example, as French immersion students spend more time in the FSL classroom, they have more time to build familiarity with their same-program peers and to create their FSL identities. This increased time spent with students in their program and separation from students outside their program may lead to stronger internal ingroup-outgroup categorizations, which may result in higher emotional attachment to the ingroup than students in other FSL programs.

Although the current study cannot attribute causation for the differences in reported social identity across programs to any singular factor, the responses to the open-ended qualitative questions do provide insights into the experience of different FSL programs and the dynamics between students of various programs. Indeed, the explanations for students’ multiple-choice answers reveal similar themes in the responses of French immersion and extended French students. These FSL groups were more likely to agree that students in their FSL program acted like a group (Question 1) and were separated from students in other FSL programs (Question 3) than their core French counterparts. The notions of group bonds (Question 1) and behavior (Question 2) also seem to be most recognizable to these students, who describe boundaries between members of their own FSL group and non-members, particularly core French students whom they refer to as ‘‘English’’ students. This distinction reveals that the participants have internalized and appropriated the label ‘‘French’’ to their own identity and seem to derive self-enhancement and positive self-esteem from it. This provides evidence for the existence of French immersion and extended French social groups. Future studies could expand on the factors underlying the reported social identity differences between FSL programs to determine how specific ingroup-outgroup social dynamics contribute to the formation of social identities among these high school populations. Moreover, it would be interesting to investigate potential hierarchies6 or oppositions between programs that may contribute to these dynamics.

Concerning methodological improvements, our suggestions are twofold. First, we suggest the inclusion of a measure of L2 performance. This would allow us to determine whether there is an association between social identity and linguistic variables. Although associations between speech and school- (Eckert, 1989, 2008) and classroom-based social groups (Nardy et al., 2014) have been observed in first language research, associations between social identity and L2 speech remain unexplored. Second, we propose that an increase in the size and scope of the study would allow for more in-depth analyses. The inclusion of a larger age range of participants with a larger sample size would allow for the consideration of group characteristics. Future studies could investigate whether factors such as age or gender influence the social identity of high school learners. Additionally, we would like to note that while the questionnaire was administered to participants online and that this provided greater flexibility and accessibility for participants, it also presented some limitations (Wilson and Dewaele, 2010). As individuals’ social identities become psychologically active based on the social context at a particular moment in time (Reicher et al., 2010), it is possible that the FSL program-based social identities may have been more salient if students were in an FSL context (e.g., the FSL classroom) at the time of testing.

Conclusion

There are few studies in social psychology that examine the strength of individuals’ social identity with respect to a particular social group. Among these studies, education-based social groups have rarely been investigated and, to date, no research has compared the strength of program-related social identities of students in the same schools who are otherwise comparable. The present study extended an existing questionnaire, the ingroup identification questionnaire (Leach et al., 2008), to a new population of study, FSL classroom learners, to investigate social identity within L2 educational contexts. It is clear, that high school FSL programs do lead to the formation of distinct social groups as students categorize one another into ingroup and outgroup members. Different student groups do, indeed, report varying levels of social identity with their FSL program ingroup, with French immersion students reporting the highest levels of ingroup identification with their FSL membership as compared to extended or core French students. Such findings could be the result of numerous factors underlying the structure of these unique programs such as time spent in the FSL classroom and the development of friendships, confidence and familiarity with their same-program peers. Furthermore, student comments reveal that, in accordance with SIT, individuals who identify more strongly with their FSL program report identification with their ingroup and comparison and differentiation with members of the outgroup. These patterns seem to correspond particularly to the emotional connection that individuals associate with their ingroup indicating that this makes up an important part of students’ educational experience.

First, this study contributes to our knowledge of the dynamics within and between FSL programs in Ontario, Canada. We see that there is, indeed, comparison and dissociation between members of opposing programs. The results of the open-ended questions provided insight into students’ perceptions of their L2 programs—an element that is often missing from L2 acquisition and education studies. This insight into how students feel regarding their L2 peer groups is of particular interest and may provide a new area of consideration for L2 teachers and researchers. Second, such findings indicate that social identity could in fact serve as a new variable in L2 acquisition and that its potential implications for L2 learners merit further investigation. Social identity could serve as an important reflection of various aspects of language education programs that contribute to the strength of individuals’ association with their L2 ingroup. Future studies might investigate group-level behaviors in L2 education programs. This will expand our knowledge of individual and group-level differences in L2 acquisition as well as studies of social identity more generally. There are many potential avenues of research to explore, such as potential relationships between social identity and specific group-level attitudes (e.g., toward teachers, education, language learning), motivations and linguistic behaviors (e.g., grammatical, morphological, phonetic) in L2 acquisition.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found online in the APA’s repository on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/df9xb/?view_only=8673ba51c2e14f9aa69503aab6798b2a.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Social Sciences, Humanities & Education Research Ethics Board, University of Toronto. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.874287/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ The age equivalences for students at the beginning of the school year (i.e., September) for the Ontario grade levels mentioned here are as follows: Grade 1: Ages 5–6, Grade 4: Ages 8–9, Grade 8: Ages 12–13, Grade 9: Ages 13–14, Grade 10: Ages 14–15, Grade 11: Ages 15–16, Grade 12: Ages 16–17.

- ^ The disproportionate female-to-male ratio of participants in the current study, particularly among Core French students, is reflective of student enrollment in Ontario FSL programs at the secondary level, where female students are slightly overrepresented (Sinay, 2015).

- ^ Our analysis treats Likert scale data as ordinal data because this is the prescribed method by most available statistical resources (e.g., Allen and Seaman, 2007; Boone and Boone, 2012; Mangiafico, 2016).

- ^ As this study is survey-based, we determined Wei and Hu’s (2018) benchmark system to be most appropriate for our analyses.

- ^ The fact that core French students are referred to as the “English” students may further serve as a means of distancing them from French immersion and extended French groups.

- ^ The investigation of potential hierarchies was inspired by participant comments suggesting that students in one FSL group mocked (FI09), excluded (EF11), or thought themselves superior to (FI07) students registered in other FSL programs.

References

Abrams, D., and Hogg, M. A. (1990). Social identification, self-categorization and social influence. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1, 195–228. doi: 10.1080/14792779108401862

Abrams, D., Wetherell, M. S., Cochrane, S., Hogg, M. A., and Turner, J. C. (1990). Knowing what to think by knowing who you are: Self-categorization and the nature of norm formation, conformity, and group polarization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 29, 97–119. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1990.tb00892.x

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 17, 475–482. doi: 10.1177/0146167291175001

Comanaru, R.-S., and Dewaele, J.-M. (2015). A bright future for interdisciplinary multilingualism research. Int. J. Multicult. 12, 404–418. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2015.1071016

Dewaele, J.-M., Witney, J., Saito, K., and Dewaele, L. (2017). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: The effect of teacher and learner variables. Lang. Teach. Res. 22, 676–697. doi: 10.1177/1362168817692161

Dumont, K., and Louw, J. (2009). A citation analysis of Henri Tajfel’s work on intergroup relations. Int. J. Psychol. 44, 46–59. doi: 10.1080/00207590701390933

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size, and language in humans. Brain Behav. Sci. 16, 681–735. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x00032325

Eckert, P. (1989). Jocks And Burnouts: Social Categories And Identity In The High School. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Eckert, P. (2008). Variation and the indexical field. J. Sociolinguistics 12, 453–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2008.00374.x

Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., and Ouwerkerk, J. W. (1999). Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 29, 371–389. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(199903/05)29:2/3<371::aid-ejsp932>3.0.co;2-u

Genesee, F. (1978). A longitudinal evaluation of an early immersion school program. Can. J. Educ. 3, 31–50. doi: 10.2307/1494684

Harter, S. (2012). “Emerging self-processes during childhood and adolescence,” in Handbook Of Self And Identity, eds M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 680–716.

Hogg, M. A. (2012). “Social identity and the psychology of groups,” in Handbook Of Self And Identity, 2nd Edn, eds M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 502–519.

Hogg, M. A. (2018). “Social identity theory,” in Contemporary Social Psychology Theories, ed. P. J. Burke (Redwood: Stanford University Press), 112–138.

Hogg, M. A., Abrams, D., Otten, S., and Hinkle, S. (2004). The social identity perspective: Intergroup relations, self-conception, and small groups. Small Group Res. 35, 246–276. doi: 10.1177/1046496404263424

Jackson, J. W. (2002). Intergroup attitudes as a function of different dimensions of group identification and perceived intergroup conflict. Self Identity 1, 11–33. doi: 10.1080/152988602317232777

Jenkins, R. (2014). “Groups and categories,” in Social Identity, 4th Edn, ed. R. Jenskins (Milton Park: Routledge), 104–119. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511897177.008

Leach, C. W., Zomeren, M. V., Zebel, S., Vlick, M. L. W., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., et al. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical (multicomponent) model of in-group identification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 95, 144–165. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144

Leonardelli, G. J., Pickett, C. L., and Brewer, M. B. (2010). Optimal Distinctiveness Theory: A framework for social identity, soc ial cognition and intergroup relations. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 43, 65–115.

Li, S. (2016). The construct validity of language aptitude: A meta-analysis. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 38, 801–842. doi: 10.1017/s027226311500042x

Luhtanen, R., and Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personal. Soc. Psychol Bul. 18, 302–318. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000258

MacKinnon, N. J., and Heise, D. R. (2010). “Language and social institutions,” in Self, Identity and Social Institutions (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 19–48.

Mangiafico, S. S. (2016). Summary and Analysis of Extension Program Evaluation in R (Version 1.18.8). Available online at: https://rcompanion.org/handbook/ (accessed April 29, 2022).

Masgoret, A.-M., and Gardener, R. C. (2003). Attitudes, motivation, and second language learning: A meta-analysis of studies conducted by Gardener and associates. Lang. Learn. 53, 167–210. doi: 10.1111/1467-9922.00227

McLeod, J. (2000). Subjectivity and schooling in a longitudinal study of secondary students. Br. J. Sociology Educ. 21, 501–521. doi: 10.1080/713655367

Moreland, R. L., and Levine, J. M. (2003). “Group composition: Explaining similarities and differences among group members,” in The Sage Handbook Of Social Psychology, eds M. A. Hogg and J. Cooper (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 367–380.

Nardy, A., Chevrot, J.-P., and Barbu, S. (2014). Sociolinguistic convergence and social interactions within a group of preschoolers: A longitudinal study. Lang. Var. Chang. 26, 273–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954394514000131

Perry, P. (2002). Shades Of White: White Kids And Racial Identities In High School. Durham: Duke University Press.

Reay, D. (2010). “Identity making in schools and classrooms,” in The Sage Handbook Of Identities, eds M. Wetherell and C. T. Mohanty (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 277–294. doi: 10.4135/9781446200889.n16

Reicher, S., Spears, R., and Haslam, S. A. (2010). “The social identity approach in social psychology,” in The Sage Handbook Of Identities, eds M. Wetherell and C. T. Mohanty (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 45–62.

Royce, A. S. Jr. (2007). “Characteristics of groups,” in Encyclopedia Of Social Psychology, eds R. F. Baumeister and K. D. Vohs (Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications), 399–401.

Rubin, M., and Hewstone, M. (1998). Social identity theory’s self-esteem hypothesis: A review and some suggestions for clarification. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2, 40–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_3

Sellers, R. M., Smith, M. A., Shelton, J. N., Rowley, S. A. J., and Chavous, T. M. (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American identity. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2, 18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2

Sinay, E. (2015). Research Brief On The Characteristics Of Students In The French As A Second Language Programs At The Toronto District School Board. Research Report No. 14/15-27. Toronto: Toronto District School Board.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology Of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin and S. Worchel (Pacific Grove: Brooks-Cole), 33–47.

Turner, J. C. (1985). “Social categorization and the self-concept: A social cognitive theory of group behaviour,” in Advances In Group Processes: Theory And Research, ed. E. J. Lawler (Stamford, CT: JAI Press).

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering The Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Turner, J. C., and Oakes, P. J. (1989). “Self-categorization and social influence,” in The Psychology Of Group Influence, ed. P. B. Paulus (Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 233–275.

Wei, R., and Hu, Y. (2019). Exploring the relationship between multilingualism and tolerance of ambiguity: A survey study from and EFL context. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 22, 1209–1219. doi: 10.1017/s1366728918000998

Wei, R., Liu, H., and Wang, S. (2020). Exploring L2 grit in the Chinese EFL context. System 93:102295. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102295

Keywords: social identity, second language acquisition, French, education, psychological variable, questionnaire, identity

Citation: Walton H (2022) Investigating a New Psychological Variable in Second Language Acquisition: Comparing Social Identity Across Canadian French Education Programs. Front. Educ. 7:874287. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.874287

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 12 May 2022.

Edited by:

Anna Mystkowska-Wiertelak, University of Wrocław, PolandReviewed by:

Peijian Paul Sun, Zhejiang University, ChinaRining (Tony) Wei, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, China

Roberto Di Paolo, IMT School for Advanced Studies Lucca, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Walton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hilary Walton, aGlsYXJ5LndhbHRvbkBtYWlsLnV0b3JvbnRvLmNh

Hilary Walton

Hilary Walton