Abstract

In recent years, the widespread adoption of social media has immersed users in content dominated by conventional beauty ideals and the relentless pursuit of perfection. This pervasive influence has significantly altered the perceptual landscape for young individuals, particularly pre-adolescents and adolescents, shaping their self-evaluations and contributing to distorted notions of beauty. The virtual realm, saturated with carefully curated and idealized images promoting unattainable beauty standards, has intensified concerns about body image. This study aims to comprehensively examine the intricate interplay between social media use and the body image of preadolescents and adolescents. Through a meticulous systematic review of 16 studies, a consistent consensus emerges, highlighting a noteworthy correlation between key variables such as the duration of social media usage, problematic engagement patterns, specific activities within these platforms, and heightened levels of body dissatisfaction.

1 Introduction

Body image constitutes a multifaceted construct, encompassing four fundamental dimensions: the individual’s perception of one’s physical appearance, the emotional experiences tied to their corporeal self the cognitive beliefs and attitudes regarding the body (Cash and Smolak, 2012). Disruptions in one’s body perception can substantially impact psychological well-being (Tomas-Aragones and Marron, 2014). Extensive research underscores the substantial influence of socio-cultural factors in developing body dissatisfaction (Cafri et al., 2005). Negative body image can originate from various sources, including familial influences, peer interactions, media representations, and societal pressures (Shen et al., 2022), ultimately influencing self-esteem, competence, and social functioning (Hosseini and Padhy, 2023).

In recent years, the rapid proliferation of social media has exposed an ever-expanding user base to content that promotes conventional beauty standards, places a premium on thinness, and celebrates flawlessness. Consequently, body dissatisfaction can arise from internalizing these appearance ideals and struggling to conform to media-propagated beauty standards (Jiotsa et al., 2021). Individuals who invest more time on social media platforms find themselves inundated with feedback related to their physical appearance (De Vries et al., 2016). Social media platforms provide young individuals with continuous appraisals of their physical appearance through comments and “likes” (De Vries et al., 2019). Online communities, often characterized by shared interests, ideologies, or lifestyles, can substantially contribute to constructing an individual’s identity, values, and beliefs. In some cases, these online communities can exert a more pronounced influence than one’s physical social circles (Lüders et al., 2022). These dynamics can significantly impact self-perception, potentially leading to body dissatisfaction and disorders in the formation of the self-image. The continuous exposure to seemingly perfect lives and experiences portrayed on social media can foster feelings of inadequacy and envy, affecting an individual’s self-esteem and overall well-being (Samari et al., 2022). Furthermore, pursuing online validation in the form of likes and positive comments can instigate a dependence on external validation, linking one’s sense of self-worth to online approval (Chen and Sharma, 2015; Papaioannou et al., 2021). A critical aspect of social networks is their interactivity, which empowers users to engage in content creation and curation actively. This interactivity enables individuals to actively shape their online presentation and self-perception (Dwivedi et al., 2022).

This issue is particularly pertinent during preadolescence, which marks a transitional period characterized by the anticipation of the forthcoming puberty phase. Preadolescence is recognized as a vulnerable developmental stage that heightens the susceptibility to various issues, including eating disorders, social anxiety, and depression (Khan and Avan, 2020). As preteens anticipate the onset of puberty and the accompanying bodily changes, they often experience heightened sensitivity and self-consciousness regarding their appearance. The formation of preteens’ body image commences during this developmental phase, and the constant comparisons with beauty ideals promoted by social media can substantially influence their body satisfaction. Numerous studies have consistently revealed the prevalence of body dissatisfaction among both girls and boys during preadolescence. This phenomenon is exemplified in the research conducted by Mccabe and Ricciardelli (2005). For instance, investigations have indicated that around 50% of preadolescents aged 8 to 11, irrespective of gender, desire a thinner physique, as demonstrated by findings from Dunn et al. (2010) and Truby and Paxton (2008). Sociocultural factors exert a substantial influence on the shaping of preadolescents’ body image, and it is crucial to acknowledge that, in the digital age, social media plays a prominent role within this sphere of influence (Aparicio-Martinez et al., 2019). In the digital landscape, preadolescents are exposed to many images promoting stereotyped beauty ideals. These platforms often present individuals who epitomize flawless beauty while adhering to unrealistic standards. Consequently, this exposure encourages heightened self-scrutiny and fosters an overwhelming desire to conform to these elusive ideals, sometimes leading preadolescents to fear judgment and rejection based on their physical appearance (MacCallum and Widdows, 2018). Young people often encounter curated and edited photos of their peers on social media, leading to social comparisons with idealized images. This can increase the perceived gap between their ideal and actual appearance, leading to body dissatisfaction (Scully et al., 2020).

Moreover, exposure to idealized images of unknown, same-aged peers on social media can have similar effects. Research shows that adolescent girls exposed to edited Instagram photos of peers may experience worse body image, particularly if they tend to engage in social comparisons. These comparisons may occur with recognizing that the portrayed images are realistic representations of their peers (Kleemans et al., 2018).

In defiance of age restrictions imposed on numerous platforms, preadolescents consistently devise strategies to gain unauthorized access to social networks, exposing themselves to content that may not align with their developmental needs. Despite being underestimated and seldom investigated, this phenomenon underscores the imperative for thorough examination and understanding, as it poses potential risks to their cognitive and emotional well-being. In the case of adolescents, scientific research is more extensive, primarily due to its recognized critical nature and the legal accessibility of social media platforms for this age group. Adolescence is considered a pivotal developmental stage (Dorn and Biro, 2011), which has led to a wealth of studies exploring the influence of social media on adolescents (De Vries et al., 2016; Ho et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2019; Boursier et al., 2020). Additionally, legal regulations typically permit adolescents to access and engage with social media, contributing to a more substantial body of research in this age group.

The implementation of educational initiatives focused on cultivating a positive body image, fostering resilience, and promoting the safe and age-appropriate use of social media emerges as a potential solution to mitigate the adverse effects of early exposure to beauty standards and the potential exacerbation of body dissatisfaction during this crucial phase of development (Thai et al., 2024). It is vital to address this issue comprehensively, considering the internal and external factors contributing to body image perceptions and well-being, to create a more supportive and empowering environment for the younger generation. The aim of this review is to examine whether social media usage affects the body image of young individuals. Additionally, we seek to identify current gaps in the scientific literature to propose new, more inclusive research perspectives. Through a comprehensive analysis of existing studies, we aim to shed light on the intricate relationship between social media engagement and body image concerns among youth. By addressing the limitations of current research and proposing novel avenues for inquiry, we endeavor to contribute to a deeper understanding of this complex phenomenon and inform future research endeavors in a manner that promotes inclusivity and relevance.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategies

The present systematic review aims to analyze and discuss studies investigating the impact of social networks on the body image of pre-adolescents and adolescents, adhering to the rigorous and transparent methodology outlined in the PRISMA guidelines (2020) (Page et al., 2021).

The search for relevant literature was conducted between June and September 2023, utilizing three prominent scientific databases: Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed. The search strategy employed a combination of keywords, including “body image,” “social networks,” and “preadolescents/adolescents” (as detailed in Table 1). To ensure a comprehensive examination of the available material, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established, encompassing the evaluation of titles, abstracts, and full-text content of all identified records.

Table 1

| Social media | Body image | Pre-adolescents, adolescents |

|---|---|---|

| Social network | Body image | Pre-adolescents |

| Social media | Body perception | Preadolescents |

| Social network use | Body pressure | Preteens |

| Social media use | Body ideals | Pre-teens |

| Feed | Body dissatisfaction | Young |

| Post | Body size perception | Adolescents |

| Share | Body representation | Teenagers |

| Tag | Body focused | |

| Social network account | Body concern | |

| Chat | Body distortion | |

| Follower | Body shame | |

| Social platform | Body esteem |

Search terms used in all databases.

“Body image” OR “body perception” OR “body pressure” OR “body ideals” OR “body dissatisfaction” OR “body size perception” OR “body representation” OR “body focused” OR “body concern” OR “body distortion” OR “body shame” OR “body esteem” AND “social network” OR “social media” OR “social network use” OR “social media use” OR “feed” OR “post” OR “share” OR “tag” OR “social network account” OR “chat” OR “follower” OR “social platform” AND “pre-adolescents” OR “preadolescents” OR “preteens” OR “pre-teens” OR “young” OR “adolescents” OR “teenagers”.

Inclusion criteria were designed to encompass cross-sectional and longitudinal studies employing quantitative methods that specifically delved into the relationship between social networks and body image among pre-adolescents and adolescents. These studies focused on body image as their primary outcome and involved participants falling within the pre-adolescent and adolescent age range. Exclusion criteria were applied to filter out review articles, meta-analyses, studies where the sample’s mean age exceeded 19 years, studies not written in the English language, editorials, commentaries, case studies, protocol studies, conference proceedings, books, book chapters, and theses.

The screening process for studies followed a hierarchical approach, involving assessments based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, beginning with the title, then the abstract, and finally the full text. Papers were incorporated into the review only if they satisfied the specified inclusion criteria. The data extraction process encompassed critical information such as author(s), publication year, study location, objectives, research design, sample characteristics, and methodological details. Particular emphasis was placed on primary outcome measures pertaining to body image, including the instruments used for measurement, along with a comprehensive description of the concept of body image. Furthermore, effect sizes associated with body image outcomes were calculated and documented. Key discussion points and any identified limitations were also systematically recorded.

2.2 Qualitative assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018) was employed to assess the evaluation procedure’s quality. The MMAT process encompassed several stages, including (1) addressing screening questions that evaluate the clarity and efficacy of the research inquiries; (2) classifying the research design; and (3) filling out a checklist for each research design category to assess pertinent quality attributes. The scoring for each criterion involved assigning a score of 1 for presence and 0 for absence. Discrepancies in quality assessments between the reviewers primarily pertained to how the findings were related to researchers’ influence and the sampling strategy of quantitative data. These discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Subsequently, a quality score for each article was calculated by dividing the total points scored by the total points possible. Each article was categorized as weak (≤0.50), moderate-weak (0.51 to 0.65), moderate-strong (0.66 to 0.79), or strong (≥0.80) in terms of study quality.

3 Results

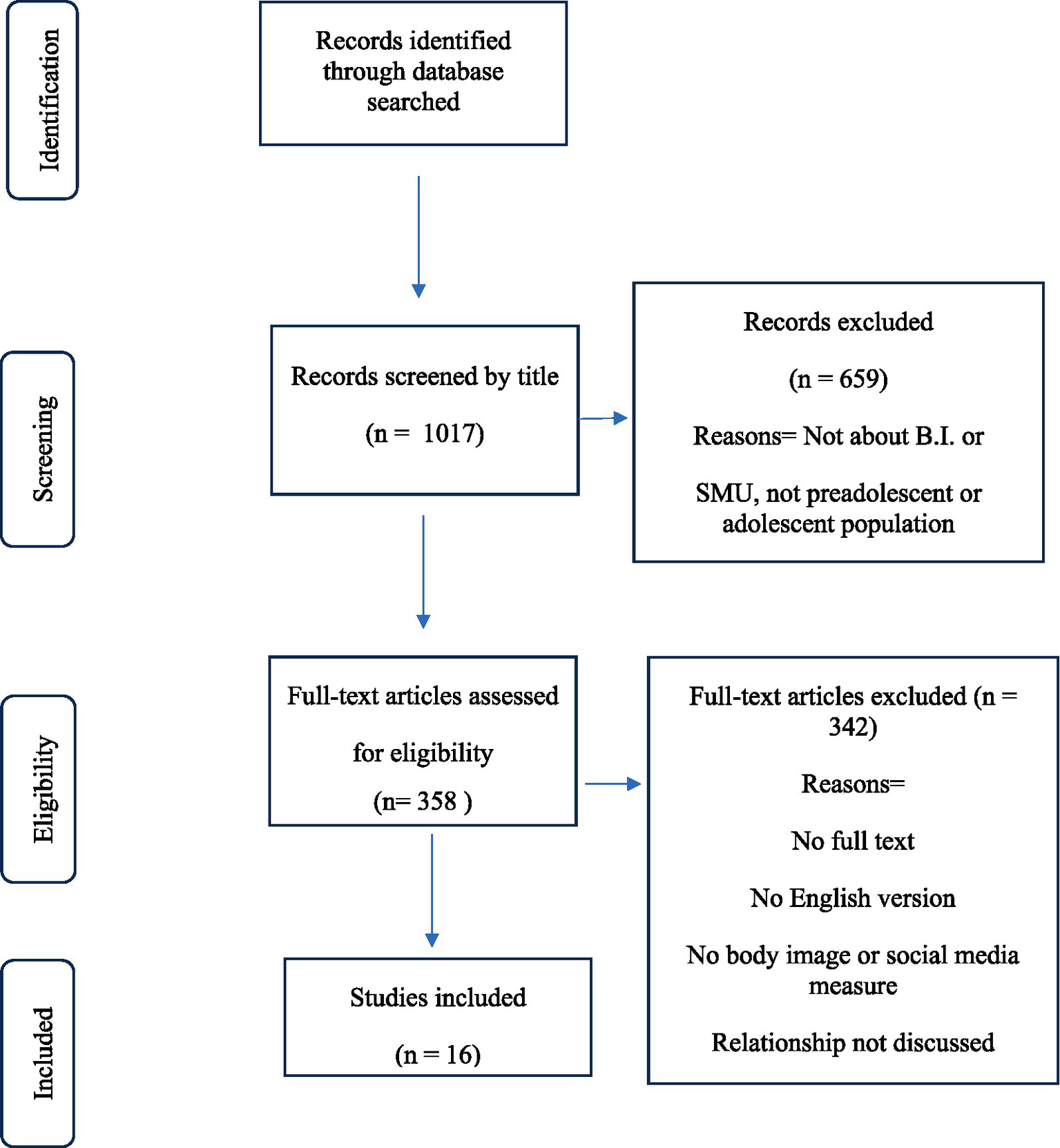

The database search identified a total of 3,023 studies; after removing duplicates, 1,017 studies were selected for screening. Out of the total records, 659 were excluded based on the title or abstract. Following the full-text review, 16 studies were included in the review (Figure 1). A summary of the included study is presented in Table 2.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature review and paper inclusion pathways.

Table 2

| First author/year | Country | Participants | Mean age | Social media evaluation | Body image evaluation | Major outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boursier et al. (2020) | Italy | 693 (55% Females) |

16 | - Time spent on social networks - Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale 2 |

- Objectified Body Consciousness Scale - Body Image Control in Photos-Revised |

The study revealed that appearance control beliefs played a negatively predictive role in influencing control over body image in photos. Additionally, Body Image Control in Photos (BICP) was identified as a mediator in the negative impact of appearance control beliefs on problematic Social Networking Site (SNS) use among girls. This research contributes to the understanding of the impact of appearance control beliefs on problematic SNS use, providing insights into predictive and protective factors in this context. |

| Chang et al. (2019) | China | 303 Females | 14.22 | - Selfie practices | - Physical Comparison Scale - Body Esteem Scale - Direction of appearance comparison |

The study explored the dual roles of young girls as both selfie observers and presenters on social media, examining the dynamics of their selfie practices, peer comparisons, and self-evaluation of body esteem. The findings revealed that photo browsing (observers) and photo posting (presenters) were directly linked to girls’ body esteem, but in opposite directions. Photo browsing showed a negative association with body esteem, while photo posting showed a positive association. Peer appearance comparisons were identified as full mediators in the relationships between photo browsing and body esteem, as well as between photo editing and body esteem. |

| Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan (2023) | Turkey | 1,667 (60% Female) | 16.3 | - Social Media Addiction Scale for Adolescents - Appearance Related Social Media Consciousness Scale |

Body Image Scale | The study determined that being female, increasing the time spent on the internet, sharing pictures frequently, using filters on pictures and being uncomfortable with the sharing of unfiltered pictures, and spending the most time on social media sites were strong predictors of Appearance Related Social Media Consciousness Scale, Social Media Addiction Scale for Adolescents and Body Image Scale scores. |

| De Vries et al. (2014) | Netherlands | 604 (51% Females) | 14.7 | Frequency of checking Hyves.nl | Appearance investment Desire to undergo cosmetic surgery |

Social networks use predicted desire to undergo cosmetic surgery indirectly via increased appearance investment Gender did not moderate findings |

| De Vries et al. (2016) | Netherlands | 604 (51% Female) |

14.7 | Frequency of checking Hyves.nl | - Peer Appearance-Related Feedback - Body Areas Satisfaction Scale a subscale of the Multidimensional Body Self – Relations Questionnaire |

social network site use predicted increased body dissatisfaction and increased peer influence on body image in the form of receiving peer appearance-related feedback. Peer appearance-related feedback did not predict body dissatisfaction and thus did not mediate the effect of social network site use on body dissatisfaction. Gender did not moderate the findings. Hence, social network sites can play an adverse role in the body image of both adolescent boys and girls. |

| Digennaro and Iannaccone (2023) | Italy | 2,378 (47.2% Females) |

12.02 | - Instagram Image Activity Scale(IIAS) - Instagram Appearance Comparison Scale—IACS |

- Italian Body Image State Scale (BISS) | The study investigated the impact of social media use, dualism (separation between real and virtual identities), and physical activity levels on body satisfaction in male and female pre-teens. Results showed that physical activity positively influenced body satisfaction in both genders, while dualism negatively affected body satisfaction in females. The findings suggest that engaging in offline activities may counteract the negative consequences of beauty ideals promoted by image-centric social media platforms among pre-teens. |

| Martinac Dorčić et al. (2023) | Croatia | 354 (78.9% Females) |

18.49 | - Time spent on social networks | The Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults | Females use social media more than Males. The results showed that identity dimensions, social media use, and social comparison explained a significant proportion of the variance in body image satisfaction. |

| Fardouly et al. (2020) | Australia | 528 (49,1% Females) |

11.19 | -Social media use - Social media activities |

Appearance and Weight subscales of the Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults | Users of YouTube, Instagram, and Snapchat reported more body image concerns and eating pathology than non-users, but did not differ on depressive symptoms or social anxiety. Appearance investment uniquely predicted depressive symptoms. Appearance comparisons uniquely predicted all aspects of mental health, with some associations stronger for females than males |

| Ferguson et al. (2014) | United States | 237 Females | 15.7 | Frequency of checking various social networks per day | Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults | Social networks (SNS) use not related to body dissatisfaction or eating disorders SNS use contributed to later peer competition |

| Ho et al. (2016) | China | 1,059 (46.5% Females) | 14.74 | Level of attention to the Internet in terms of social networks, blogs, forums, videos, entertainment/celebrity news/gossip websites or blogs, gaming, and social news/entertainment sites with user-generated content; The average number of hours per day that they spent on their favorite SNS in the past week |

Two adapted subscales from the Eating Disorders Inventory (EDI) that assess body image attitudes | This study, applying social comparison theory, investigated how adolescents’ engagement in comparisons with friends and celebrities on social network sites (SNSs) affects (a) body image dissatisfaction (BID) and (b) the drive to be thin (DT) or muscular (DM). The survey, involving 1,059 adolescents in Singapore, revealed that SNS use was linked to adolescents’ BID. Specifically, social comparison with friends on SNSs was significantly associated with BID, DT, and DM. Gender differences were noted, with social comparison with celebrities being linked to BID and DT among female adolescents, and celebrity involvement associated with male BID. The study discusses theoretical and practical implications. |

| Kaewpradub et al. (2017) | Thailand | 620 (60.3% females) | 15.7 | Media and Internet use behavior questionnaires | The Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults: Thai version (BESAA) | Using the internet and social networks for content related to body image and eating behaviors, was negatively associated with body image satisfaction but positively associated with inappropriate eating attitudes/behaviors, binging, purging, use of laxatives/diuretics and drive for muscularity with respect to behaviors and attitudes, and was associated with eating behaviors that carried a risk for obesity. |

| Meier and Gray (2014) | United States | 103 Females | 15.2 | - Time spent on Facebook per day - Frequency of Facebook appearance-related exposure |

- Physical Appearance comparisons Scale - Drive for thinness from Eating Disorder Inventory -Internalization of Appearance Questionnaire for Adolescents |

Elevated appearance exposure, but not overall FB usage, was significantly correlated with weight dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, thin ideal internalization, and self-objectification |

| Mesce et al. (2022) | Italy | 204 (118 Female) |

15.88 | - Bergen Instagram Addiction Scale - Internet Addiction Test - Youth Self Report |

Body Image Concern Inventory | The results of the present study demonstrated the existence of a correlation between social media addiction and Body image concerns: this correlation was significant, positive, and moderate for both the total sample and the gender and age subgroups. |

| Sagrera et al. (2022) | USA | 5,070 (49.52% Females) |

16.00 | - Type of platforms used - Time spent on social media daily |

Questions about body image issues | Results showed females were more likely to use social media and report Body Image Issues compared to males, while both sexes reported BII with increasing time spent on social media. A diversity of platforms were associated with increased body image issues among social media users compared to non-users: Pinterest, Reddit, Snapchat, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube |

| Tiggemann and Slater (2014) | Australia | 189 Females | 11.5 | - Questions about Internet usage - Sociocultural Internalization of Media Ideals Scale |

- Sociocultural Internalization of Media Ideals Scale - Body Surveillance Scale of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale—Youth - Body Esteem Scale for Children of Mendelson and White |

All forms of media exposure were significantly correlated with some aspect of body image concerns. Total internet exposure was significantly correlated with all four measures of body image concern. |

| Brajdić Vuković et al. (2018) | Croatia | 211 Females | 16.14 | Questions about Internet usage | Objectified Body Consciousness Scale for Adolescents | Body-surveillance was significantly associated with time spent using SNS. While higher SNS use and the number of same-sex confidants were positively related to body-surveillance among female adolescents, BMI scores and self-esteem were negatively associated with the outcome. |

Summary of articles.

3.1 Qualitative assessment

The MMMT (Hong et al., 2018) assessed six studies as moderate quality (Ferguson et al., 2014; Meier and Gray, 2014; Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018; Mesce et al., 2022; Sagrera et al., 2022) and ten studies as strong quality (De Vries et al., 2014, 2016; Ho et al., 2016; Kaewpradub et al., 2017; Chang et al., 2019; Boursier et al., 2020; Fardouly et al., 2020; Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023). Overall, the selected studies set out their research aims and methodologies clearly. Data were collected from participants aged between 9 and 19 years old. Most studies have a clear statement of findings and addressed factors-related limitations. Table 3 shows the studies assessed by each criterion.

Table 3

| Authors (Year) | Sampling strategy relevant to objectives | Sample representativeness | Measurements appropriate | Acceptable response rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boursier et al. (2020) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Chang et al. (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| De Vries et al. (2014) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| De Vries et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Digennaro and Iannaccone (2023) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Martinac Dorčić et al. (2023) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fardouly et al. (2020) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ferguson et al. (2014) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ho et al. (2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kaewpradub et al. (2017) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Meier and Gray (2014) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mesce et al. (2022) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sagrera et al. (2022) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Tiggemann and Slater (2014) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Brajdić Vuković et al. (2018) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

MMAT (1 = meet criteria; 0 = did not meet criteria).

3.2 Overview of findings

A significant portion of the studies (n = 13) centered on adolescents, with a relatively more minor number concentrating on preadolescents (n = 3). The ages of the participants ranged from 9 to 19 years old. Sample sizes ranged between 5,070 (Sagrera et al., 2022) and 103 (Meier and Gray, 2014). The study samples primarily originated from Europe (n = 7) (De Vries et al., 2014, 2016; Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018; Boursier et al., 2020; Mesce et al., 2022; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023) while a minority were sourced from North America (n = 3) (Ferguson et al., 2014; Meier and Gray, 2014; Sagrera et al., 2022), China (n = 2) (Ho et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2019), Australia (n = 2) (Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Fardouly et al., 2020), Thailand (n = 1) (Kaewpradub et al., 2017), and Turkey (n = 1) (Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023).

Most of the studies incorporated males and females in the research (n = 11) (De Vries et al., 2014, 2016; Ho et al., 2016; Kaewpradub et al., 2017; Boursier et al., 2020; Fardouly et al., 2020; Mesce et al., 2022; Sagrera et al., 2022; Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023), although studies were conducted exclusively with female participants (n = 5) (Ferguson et al., 2014; Meier and Gray, 2014; Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2019). In all the studies, traditional gender binary classifications were employed; none of them included non-binary or gender-fluid individuals.

All studies aim to contribute to a better understanding of how modern media and social networking platforms influence preadolescents’ and adolescents’ body image concerns and the pursuit of idealized body shapes while considering potential gender differences in these processes. The objectives of the studies included in this review can be divided into different categories. First, studies have examined the relationship between social media exposure and preadolescents/adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction (BID) by assessing how social media use and exposure to idealized body images contribute to BID (Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Kaewpradub et al., 2017; Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018; Boursier et al., 2020; Fardouly et al., 2020; Mesce et al., 2022; Sagrera et al., 2022). Second, studies have focused on how social comparison processes on social networking sites (SNSs) impact adolescents’ BID and their drive to achieve ideal body types, including thinness and muscularity (Meier and Gray, 2014; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023). The third category of studies investigated the relationship between self-objectification, particularly focusing on appearance control beliefs and body image control in photos, and problematic use of social networking sites (SNSs) among preadolescents/adolescents (Chang et al., 2019; Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023). The fourth category of studies explored the role of peers and celebrities in the body objectification process associated with online social networking use among preadolescents/adolescents (De Vries et al., 2014, 2016; Ferguson et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2016).

Most studies in this review utilized cross-sectional research designs, primarily relying on self-report survey methods (n = 13) (Meier and Gray, 2014; Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Ho et al., 2016; Kaewpradub et al., 2017; Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2019; Boursier et al., 2020; Fardouly et al., 2020; Mesce et al., 2022; Sagrera et al., 2022; Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023). A minority of the investigations employed a longitudinal research framework (De Vries et al., 2014, 2016; Ferguson et al., 2014). All the records included in this review exclusively consisted of quantitative data.

The overarching findings from these studies consistently demonstrated a significant correlation between social network usage and body image. The analysis identified three key dimensions relevant to the use of social networks: the time spent on online platforms, the types of activities conducted on social networks, and the likelihood of developing an addiction to social media. Concerning the time allocated to social networks, a positive association was observed in (Tiggemann and Slater, 2014) study, wherein extended usage of platforms such as MySpace and Facebook was linked to body surveillance and the internalization of slender body ideals. Complementing this finding (Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018), research further substantiated the significant correlation between adolescent girls’ duration of social network engagement and their inclination toward body surveillance.

Furthermore, in De Vries et al. (2014) study, it was hypothesized that a heightened frequency of social network usage would lead to increased body dissatisfaction. The study’s results validated this conjecture.

Within the scope of this review, three studies delved into specific activities conducted on social networks. Ho et al. (2016) study explored the impact of exposure to diverse content disseminated on social networks, particularly its implications for body image. Using the social comparison theory, this investigation examined the relationship between self-comparisons with peers and celebrities on social networks and their respective effects on body dissatisfaction. The study’s findings revealed that comparing oneself to peers exhibited a considerably stronger association with body dissatisfaction and the desire for a thin and muscular physique than comparing oneself to celebrities. In Meier and Gray (2014) the aim was exploring the relationship between Facebook (FB) use and body image among adolescent girls. The results, based on descriptive statistics and correlations, revealed that FB appearance exposure was positively correlated with internalization of the thin ideal, self-objectification, and drive for thinness, and negatively correlated with weight satisfaction, even when controlling for Body Mass Index (BMI). However, no significant correlations were found for total FB use or total Internet use with body image variables. When comparing FB users and non-FB users, significant differences were found in age, self-objectification, and physical appearance comparisons, with FB users scoring higher. The study suggests that the amount of time allocated to photo activity on FB, rather than total usage time, is associated with greater body image disturbance among adolescent girls. The findings highlight the importance of considering specific FB features in research and suggest practical implications for parents, clinicians, and prevention programs. The study acknowledges limitations, such as a predominantly Caucasian and middle socioeconomic status sample, correlational design, and self-report data. Overall, the research contributes to understanding the impact of social media use on adolescent body image.

Additionally, even seemingly innocuous activities like using filters and specialized applications to alter one’s physical appearance have shown the potential to negatively affect body satisfaction, as evidenced by the findings in (Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023).

Chang et al. (2019) conducted a study that investigated the influence of photo posting on social networks within a cohort of adolescent girls, revealing a statistically significant positive association between photo posting and body esteem. In this study, three types of selfie-related activities on Instagram were examined. “Browsing” involved girls viewing other people’s Instagram photos, measured by the frequency of checking Instagram and browsing peers’ posts. “Posting” referred to girls sharing selfies on Instagram, quantified by the number of selfies posted weekly. “Editing” focused on the preparation process before posting, involving the use of apps or multiple shots to modify or enhance self-images. Peer appearance comparisons were assessed through three items measuring the frequency of comparing physical appearance, clothing, and figure to peers on a 5-point scale. The direction of appearance comparisons was gaged by respondents’ self-ratings compared to close female friends and female peers on Instagram, with a scale indicating perceived superiority or inferiority. The items for each construct demonstrated reliability in their respective scales. Another salient variable under scrutiny pertains to the proclivity for dependency on social networks and the problematic utilization of these platforms. The collective findings from these investigations delineate a notable positive correlation between social media addiction and body image concerns, transcending gender distinctions (Mesce et al., 2022). Furthermore, a positive correlation was established between the propensity of adolescents to manipulate their body image in photographs and their problematic engagement with social networks (Boursier et al., 2020).

3.3 Studies with a focus on preadolescents

A restricted number of studies have explored the impact of social media on preadolescents (Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Fardouly et al., 2020; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023) possibly constrained by legal restrictions that hinder access or registration on these platforms. Despite these limitations, preadolescents persist in circumventing such restrictions and gaining unauthorized access. Among the limited studies scrutinized, which exclusively focused on preadolescents, it was revealed that using these platforms significantly influences their body satisfaction.

Digennaro and Iannaccone (2023) examined social media behavior among preadolescents, finding that most were active users of platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat. Males tended to have more public profiles, and both genders expressed moderate satisfaction with their physical appearance. Females showed higher consideration for altering their appearance with beauty filters, indicating a greater distinction between their virtual and real selves.

Fardouly et al. (2020) explored social media usage, body satisfaction, and mental health among preteens. While a majority had social media accounts, differences existed in platform preferences between genders. Users of YouTube and Instagram reported lower body satisfaction, while those on Instagram and Snapchat reported more eating pathology. No significant differences were found in depressive or social anxiety symptoms between users and non-users.

Tiggemann and Slater (2014) investigated media consumption patterns of preadolescent girls and their correlation with body image concerns. It revealed that internet exposure, particularly on Facebook and MySpace, was associated with negative body image concerns such as internalization, body surveillance, and dieting. Facebook users scored higher on these concerns compared to non-users, with internalization of the thin ideal playing a mediating role.

The three studies examined social media behavior among preadolescents, encompassing platforms used, time spent, and activities undertaken. They collectively recognize the potential influence of social media on body perception, with Digennaro and Iannaccone (2023) highlighting gender disparities in platform usage, while Fardouly et al. (2020) and Tiggemann and Slater (2014) underscore associations between social media use and mental health. Specifically, Fardouly et al. (2020) find that platforms like YouTube and Instagram correlate with diminished body satisfaction and increased eating pathology among preadolescents, while Tiggemann and Slater (2014) observe Facebook use linked to negative body image concerns such as internalization, body surveillance, and dieting, with gender differences evident in the outcomes.

3.4 Gender differences

In the comprehensive review, five studies focused on examining the impact of social media use on the body image of female samples. However, recognizing the active engagement of preadolescent and adolescent boys in social media platforms, most articles specifically delved into exploring gender differences. Significant gender differences emerged concerning various aspects of social media behavior and body image concerns among preadolescents and adolescents.

The research by Boursier et al. (2020) shed light on the observation that girls tend to exhibit higher rates of appearance control beliefs than boys. This distinction in gender extends beyond mere usage patterns and includes multifaceted aspects such as body image perceptions, mood regulation, and specific behaviors related to social networking sites. Notably, Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan (2023) found that female adolescents demonstrated elevated levels of appearance-related social media consciousness, social media addiction, and negative body image perceptions in comparison to their male counterparts. These gender differences manifest in various behaviors, encompassing internet usage, picture sharing, and the utilization of image-altering filters.

De Vries et al. (2016) findings further corroborate these observations, indicating that girls visit social networking sites more frequently than boys, and consequently, they exhibit higher levels of body dissatisfaction. These findings support the hypothesis that heightened use of social media sites predicts increased body dissatisfaction, underscoring the gender-specific impact of online social interactions on body image concerns.

The studies conducted by Martinac Dorčić et al. (2023) and Fardouly et al. (2020) both reaffirm the trend that girls tend to frequent social network sites more often than boys and express less satisfaction with their weight. However, Martinac Dorčić et al.’s (2023) study did not reveal significant gender differences in social comparison and body image satisfaction.

Fardouly et al. (2020) not only reinforced the gender disparities in social media use but also underscored the intricate relationships between online behaviors and mental health outcomes among adolescents. Notably, girls were found to actively engage more in identity exploration on social media compared to boys.

Kaewpradub et al. (2017) study provided additional insights, revealing that male participants spent significantly more time using media, while female participants, on average, dedicated more time to the internet and social media, particularly in consuming content related to body image or eating attitudes/behaviors. In Sagrera’s study, females emerged as about four times more likely than their male counterparts to report experiencing body image issues.

Digennaro and Iannaccone (2023) found that females spend more time on social media platforms than males. Boys and girls showed differences in activities related to body image on social media platforms, including taking selfies, modifying selfies before sharing, sending pictures for approval, removing tags, and removing pictures based on likes. Differences in thoughts about altering real-life appearance with beauty filters and sharing content without filters are observed between males and females.

3.5 Type of social network

In addition to examining usage time, several studies have delineated distinctions among different social network platforms. In the study conducted by Sagrera et al. (2022), a distinction is made between Highly Visual Social Media (HVSM) and other platforms (Non-HVSM). HVSM includes Instagram, Snapchat, Pinterest, YouTube, and TikTok, while the other group primarily consists of Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit. The study hypothesis posited that HVSM platforms are more strongly associated with Body Image Issues (BII) compared to non-HVSM platforms.

Pinterest, Snapchat, TikTok, and YouTube displayed statistically significant differences in self-reported BII, with percentages of 35.4, 73.7, 58.4, and 79.9%, all with p-values less than 0.001. Non-HVSM platforms, including Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter, also exhibited associations with self-reported BII, with percentages of 25.1% (p = 0.037), 12.2% (p < 0.001), and 31.7% (p < 0.001), respectively. However, Instagram did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in self-reported BII usage (84.6%, p = 0.13).

Pinterest had the highest odds of self-reporting BII (OR = 2.66, 95% CI = 2.26–3.12, p < 0.001), followed by TikTok (OR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.74–2.31, p < 0.001), Snapchat (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.33–1.81, p < 0.001), and YouTube (OR = 1.51, 95% CI = 1.27–1.80, p < 0.001). Non-HVSM platforms like Facebook and Twitter showed lower odds of self-reporting BII but remained statistically significant (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.01–1.40, p = 0.038; OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.15–1.57, p < 0.001). Instagram did not show a statistically significant association with self-reported BII in this sample (OR = 1.16; 95% CI = 0.95–1.42; p = 0.133). Not using social media was protective against self-reporting BII (OR = 0.65, 95% CI = 0.45–0.94, p < 0.021).

When stratified by gender, HVSM predictors showed increased odds of reporting BII in females and males who used Pinterest, YouTube, and TikTok. Snapchat was statistically significant for females (OR = 1.30, p < 0.05) but not for males (OR = 1.31, p = 0.09) in association with BII reporting.

While the use of HVSM was more likely to result in reports of BII, the data did not establish a definitive association between HVSM and increased BII. Various social media platforms, both HVSM and non-HVSM, showed a statistically significant increase in BII among participants. All predictors remained statistically significant after adjustment for sex differences, with Pinterest and Reddit being among the strongest contributors to BII. However, Reddit’s contribution, despite being statistically significant, maybe less meaningful due to its low usage percentage in the study population.

In Tiggemann and Slater (2014), 14.3% reported having a MySpace profile, and spending an average of 34.1 min daily. For Facebook users (42.6%), the average daily usage was 1.5 h. MySpace users had fewer friends (58.2) than Facebook users (131.1). Correlations between media exposure and body image concerns were significant, with total Internet exposure correlating with all body image measures.

Further analysis revealed that Facebook users scored higher on internalization, body surveillance, and dieting, and lower on body esteem than non-users. The time spent on Facebook daily was positively correlated with internalization, body surveillance, and dieting, and negatively correlated with body esteem. In Fardouly et al. (2020), about 66.7% of participants had at least one social media account, with an average of 2.35 accounts per user. There were no significant sex differences in the number of social media accounts. The most popular platforms were YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Google+, and Pinterest. Males were likelier to have accounts on YouTube and Google+, while females were likelier to have accounts on Pinterest, Tumblr, and Musical.ly. The study focused on three popular platforms (YouTube, Instagram, and Snapchat) and found that Instagram users were slightly older. Users of YouTube and Instagram reported less body satisfaction, and users of Instagram and Snapchat reported more eating pathology compared to non-users. In the study conducted by Chang et al. (2019), exclusive attention was directed solely toward the social media platform Instagram. In various studies (Boursier et al., 2020; Mesce et al., 2022; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023), the primary social networks used, and the time spent on each of them have been reported. However, the type of social media platform has yet to be compared with the body image variable.

3.6 Body image measures

The majority of body image assessments were conducted using Likert scale questionnaires such as the Body Image Concern Inventory (BICI) (Littleton et al., 2005), the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale–Youth (Lindberg et al., 2011), the Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (Mendelson et al., 2001), the Body Areas Satisfaction Scale, a subscale of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (Thomas, n.d.), the Italian Body Image State Scale (Cheli, 2016). In the studies, various terms have been used to refer to body image such as body perception, body satisfaction, body surveillance, and body esteem. Mesce et al. (2022) study utilized the Body Image Concern Inventory (BICI) (Littleton et al., 2005) to assess dysmorphic preoccupation. Fardouly et al. (2020) study assessed body satisfaction using the Appearance and Weight subscales of the Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (Mendelson et al., 2001), also employed in the studies of Tiggemann and Slater (2014), Martinac Dorčić et al. (2023), Ferguson et al. (2014), Kaewpradub et al. (2017), and Chang et al. (2019).

The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (Lindberg et al., 2011) was used in three studies (Tiggemann and Slater, 2014; Brajdić Vuković et al., 2018; Boursier et al., 2020), albeit with variations of the same version. Two studies (Meier and Gray, 2014; Chang et al., 2019) focused on appearance-related social comparisons using an adapted version of the Physical Appearance Comparison Scale (Thompson et al., 1991). These divergent approaches to measuring body image across the various studies underscore the complexity of the subject matter and pose a challenge when it comes to generalizing the data. The variations in measurement tools and terminologies make it difficult to draw universal conclusions and emphasize the need for careful consideration and contextualization of the findings.

4 Discussion

The emerging findings in the review align with those of previous works on the topic (Modrzejewska et al., 2022; Revranche et al., 2022). Most studies (n = 15) have found a correlation among the variables under consideration: the time spent using social networks, the problematic usage of these platforms, the type of activities conducted on social media, and body dissatisfaction. However, in Ferguson et al. (2014) study, the correlation between social media use and the body image of the sample was not identified, distinguishing it from the other studies. While exploring the impact of social networks on body image in preadolescents and adolescents, it is important to note certain considerations that can further enhance the depth and accuracy of research in this area.

4.1 Gender considerations

Firstly, it is noteworthy that a substantial proportion of existing studies focus on female groups, while studies involving male groups are relatively limited. This gender imbalance suggests a potential bias in the current body of knowledge and highlights the need for more research encompassing diverse gender perspectives. Furthermore, despite the majority of analyzed studies reporting differences between males and females, demonstrating that females are more likely to experience body dissatisfaction (De Vries et al., 2016; Boursier et al., 2020; Fardouly et al., 2020; Sagrera et al., 2022; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023), it cannot be conclusively considered solely a female issue. Understanding how social media affects the body image of both genders is essential, as it might reveal distinct vulnerabilities and coping mechanisms. Furthermore, as we delve deeper into the study of body image and its relationship with social media, it’s imperative to recognize and include individuals who do not conform to conventional gender categories, which are traditionally defined as male and female. The experiences and challenges faced by individuals outside these traditional gender binaries also play a crucial role in understanding how social media influences body image perceptions. Neglecting this aspect would be a significant oversight, as it is essential to gain insights into the diverse and nuanced ways in which social media can impact the body image of all individuals, regardless of their gender identity.

4.2 Age considerations

A pivotal consideration in delving into body image research lies in the meticulous examination of age categories utilized across various studies. Oftentimes, researchers employ overarching age classifications like ‘adolescents’ or ‘preadolescents’ to categorize their participants. While these broad groupings yield valuable insights into developmental trends, they may inadvertently overlook the intricate nuances inherent in age-related experiences. A potential enhancement in the research methodology entails adopting more granular age categories to capture the diverse spectrum of developmental stages.

By refining age classifications, researchers can dissect the multifaceted landscape of body image concerns and social media dynamics across distinct developmental periods. This could involve delineating the broad categories of ‘preadolescence’ and ‘adolescence’ into finer-grained segments, such as early preadolescence, late preadolescence, early adolescence, mid-adolescence, and late adolescence. Each of these delineations corresponds to distinct developmental milestones and socio-emotional challenges, offering a comprehensive lens through which to explore the interplay between body image perceptions and social media engagement.

Moreover, by zooming in on specific age cohorts, researchers can uncover age-specific trends, vulnerabilities, and protective factors that may otherwise remain obscured within broader age groupings. For instance, early preadolescents may grapple with body image concerns stemming from peer comparison, while late adolescents may confront pressures related to body ideals perpetuated by social media influencers. By dissecting these age-specific nuances, researchers can tailor interventions and prevention strategies to address the unique needs of different age groups effectively.

In essence, embracing a more nuanced approach to age categorization in body image research empowers researchers to unearth a deeper understanding of the developmental trajectories and contextual factors shaping individuals’ body image perceptions and experiences with social media.

4.3 Culture and ethnicity considerations

In understanding the dynamics of body image among preadolescents and adolescents, it is imperative to recognize the profound influence of culture and ethnicity. The experience of body image is not universal but rather deeply intertwined with cultural and ethnic contexts (Swami et al., 2010). As such, research endeavors must adopt a more systematic approach in considering these variables to ensure the relevance and applicability of findings across diverse populations.

Across various cultural and ethnic backgrounds, distinct norms and beauty ideals emerge, significantly shaping young individuals’ perceptions of their bodies (Frederick et al., 2007). These norms are often reinforced and perpetuated through various societal mechanisms, including media representations, family dynamics, and peer interactions (Akan and Grilo, 1995). In the digital age, social media platforms serve as potent mediums through which cultural beauty standards are disseminated, influencing how adolescents perceive and evaluate their own bodies.

Addressing the diversity inherent in cultural and ethnic backgrounds is paramount for cultivating a comprehensive understanding of body image dynamics among youth. By acknowledging and integrating these diverse perspectives into research frameworks, scholars can uncover the nuanced ways in which cultural norms intersect with social media influences to impact body image perceptions.

Furthermore, efforts to promote positive body image and mitigate negative outcomes must be culturally sensitive and tailored to the specific needs and contexts of different cultural and ethnic groups. This necessitates a nuanced approach that considers not only the broader societal influences but also the individual and collective experiences of young individuals within their cultural and ethnic communities.

Moving forward, future research endeavors should prioritize the exploration of cultural and ethnic variations in body image experiences among preadolescents and adolescents. Longitudinal studies that examine how these experiences evolve over time within different cultural contexts can offer valuable insights into the complex interplay between culture, ethnicity, and body image. Additionally, intervention strategies aimed at fostering positive body image should be culturally informed and responsive to the unique needs of diverse cultural and ethnic groups, ultimately contributing to more inclusive and effective approaches to promoting body positivity among youth.

4.4 Measurements considerations

The complexity of measuring time spent on social networks is compounded by the diverse focus of studies within this domain. While some investigations emphasize the quantification of time (Boursier et al., 2020; Sagrera et al., 2022; Martinac Dorčić et al., 2023), others delve into specific activities conducted on social media (Chang et al., 2019; Fardouly et al., 2020; Digennaro and Iannaccone, 2023), and others explore tendencies toward social media addiction (Mesce et al., 2022; Çimke and Yıldırım Gürkan, 2023). Moreover, the selection of platforms under scrutiny varies among studies, further complicating efforts to consolidate findings. This divergence in measured variables underscores the challenge of harmonizing results, as different studies assess disparate aspects of social media usage. Consequently, the interpretation and generalization of findings become intricate tasks. Regarding the measurement of body image, the majority of studies utilized subscales of larger scales (Lindberg et al., 2011; Cash, 2015). It is worth noting that tools to measure body dissatisfaction are also varied and assess different facets of body image. This variation in measurement approaches highlights the complexity of the topic and presents challenges in generalizing findings. The differences in measurement tools and terminology hinder the ability to draw broad conclusions and underscore the importance of carefully interpreting and contextualizing study results. Researchers should strive for consistency and clarity in measurement methods to facilitate meaningful comparisons and interpretation of findings across studies.

4.5 Limitations and prospects for future research

Our investigation aimed to shed light on the various tools employed in these studies, with particular attention to distinct methodologies used across different research endeavors. This research delved into studies involving preadolescents, offering unique insights into this specific demographic. Additionally, we conducted a detailed analysis of the effects of diverse social media platforms, providing a comprehensive examination of their implications. Several strengths characterize our study. Firstly, we meticulously highlighted variations among studies, emphasizing divergent patterns in social network usage and their consequent effects on body image. Secondly, our examination of the tools utilized by different studies adds a layer of complexity to our findings, contributing to a nuanced understanding of the subject. Furthermore, our specific focus on studies involving preadolescents fills a crucial gap in the existing literature, offering valuable insights into this age group. Lastly, our in-depth analyses of the effects of various social media platforms contribute to the richness of our research. Future research endeavors could explore longitudinal studies to track changes in social media usage and body image perceptions over time. Additionally, comparative studies examining cultural differences in social media impacts on body image could provide valuable insights into the role of cultural factors in shaping body image experiences. Moreover, qualitative investigations delving into individuals’ subjective experiences with social media and body image could offer richer insights into the underlying mechanisms at play. Finally, considering the evolving nature of social media platforms, ongoing research efforts could focus on developing interventions aimed at promoting positive body image in the digital age.

However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations within our study. The quality of our findings is contingent upon the methodological rigor of the primary studies included. Methodological weaknesses or limitations in these primary studies may impact the robustness of our conclusions. Additionally, our selection of studies may be subject to bias, and the exclusion of certain studies could potentially influence the overall outcomes. Furthermore, the rapidly evolving nature of social media trends may limit the temporal relevance of our conclusions, and the heterogeneity among primary studies introduces challenges in data synthesis, potentially contributing to uncertainties in our findings.

5 Conclusion

The findings underscore the significance of incorporating sex and gender considerations into body image research, emphasizing the need for balanced representation across genders. Additionally, there is a clear call for more nuanced age categorizations to capture the diverse developmental stages effectively. Moreover, the influence of culture and ethnicity on body image perceptions via social media emerges as a crucial area for investigation, highlighting the importance of cultural sensitivity in research. Lastly, the standardization of measurement tools and methodologies is crucial for facilitating meaningful comparisons across studies and advancing our understanding of this complex relationship. These insights provide valuable directions for future research endeavors in this field. As the role of social media in young individuals’ lives continues to evolve and grow, researchers must embrace these considerations to ensure their studies provide insights that can inform effective interventions and support for preadolescents and adolescents navigating the complex landscape of body image in the digital age. Also, fostering a more inclusive and diverse research approach will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic, with more universally applicable findings.

Statements

Author contributions

SD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AT: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Akan G. E. Grilo C. M. (1995). Sociocultural influences on eating attitudes and behaviors, body image, and psychological functioning: a comparison of African-American, Asian-American, and Caucasian college women. Int. J. Eat. Disord.18, 181–187. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199509)18:2<181::AID-EAT2260180211>3.0.CO;2-M

2

Aparicio-Martinez P. Perea-Moreno A. J. Martinez-Jimenez M. P. Redel-Macías M. D. Pagliari C. Vaquero-Abellan M. (2019). Social media, thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes: an exploratory analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health16:4177. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214177

3

Boursier V. Gioia F. Griffiths M. D. (2020). Objectified body consciousness, body image control in photos, and problematic social networking: the role of appearance control beliefs. Front. Psychol.11:147. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00147

4

Brajdić Vuković M. Lucić M. Štulhofer A. (2018). Internet use associated body-surveillance among female adolescents: assessing the role of peer networks. Sex. Cult.22, 521–540. doi: 10.1007/s12119-017-9480-4

5

Cafri G. Yamamiya Y. Brannick M. Thompson J. K. (2005). The influence of sociocultural factors on body image: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract.12, 421–433. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpi053

6

Cash T. F. (2015). “Multidimensional body–self relations questionnaire (MBSRQ)” in Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. ed. WadeT. (Berlin: Springer Singapore), 1–4.

7

Cash T. F. Smolak L. (2012). Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention2nd Edn.. New York: Guilford Press.

8

Chang L. Li P. Loh R. S. M. Chua T. H. H. (2019). A study of Singapore adolescent girls’ selfie practices, peer appearance comparisons, and body esteem on Instagram. Body Image29, 90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.03.005

9

Cheli S. (2016). Body image scale (BIS)–Italian Version.

10

Chen R. Sharma S. K. (2015). Learning and self-disclosure behavior on social networking sites: the case of Facebook users. Eur. J. Inf. Syst.24, 93–106. doi: 10.1057/ejis.2013.31

11

Çimke S. Yıldırım Gürkan D. (2023). Factors affecting body image perception, social media addiction, and social media consciousness regarding physical appearance in adolescents. J. Pediatr. Nurs.2023, 73, e197–e203. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2023.09.010

12

De Vries D. A. Peter J. De Graaf H. Nikken P. (2016). Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: testing a mediation model. J. Youth Adolesc.45, 211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0266-4

13

De Vries D. A. Peter J. Nikken P. De Graaf H. (2014). The effect of social network site use on appearance investment and desire for cosmetic surgery among adolescent boys and girls. Sex Roles71, 283–295. doi: 10.1007/s11199-014-0412-6

14

De Vries D. A. Vossen H. G. M. Van der Kolk-van der Boom P. (2019). Social media and body dissatisfaction: investigating the attenuating role of positive parent–adolescent relationships. J. Youth Adolesc.48, 527–536. doi: 10.1007/s10964-018-0956-9

15

Digennaro S. Iannaccone A. (2023). Check your likes but move your body! How the use of social media is influencing pre-teens body and the role of active lifestyles. Sustain. For.15:3046. doi: 10.3390/su15043046

16

Dorn L. D. Biro F. M. (2011). Puberty and its measurement: a decade in review. J. Res. Adolesc.21, 180–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00722.x

17

Dunn B. D. Galton H. C. Morgan R. Evans D. Oliver C. Meyer M. et al . (2010). Listening to your heart: how Interoception shapes emotion experience and intuitive decision making. Psychol. Sci.21, 1835–1844. doi: 10.1177/0956797610389191

18

Dwivedi Y. K. Hughes L. Baabdullah A. M. Ribeiro-Navarrete S. Giannakis M. Al-Debei M. M. et al . (2022). Metaverse beyond the hype: multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag.66:102542. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2022.102542

19

Fardouly J. Magson N. R. Rapee R. M. Johnco C. J. Oar E. L. (2020). The use of social media by Australian preadolescents and its links with mental health. J. Clin. Psychol.76, 1304–1326. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22936

20

Ferguson C. J. Muñoz M. E. Garza A. Galindo M. (2014). Concurrent and prospective analyses of peer, television and social media influences on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms and life satisfaction in adolescent girls. J. Youth Adolesc.43, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9898-9

21

Frederick D. A. Forbes G. B. Grigorian K. E. Jarcho J. M. (2007). The UCLA body project I: gender and ethnic differences in self-objectification and body satisfaction among 2,206 undergraduates. Sex Roles57, 317–327. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9251-z

22

Ho S. S. Lee E. W. J. Liao Y. (2016). Social network sites, friends, and celebrities: the roles of social comparison and celebrity involvement in adolescents’ body image dissatisfaction. Soc. Med. Soc.2:66421. doi: 10.1177/2056305116664216

23

Hong Q. N. Fàbregues S. Bartlett G. Boardman F. Cargo M. Dagenais P. et al . (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf.34, 285–291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

24

Hosseini S. A. Padhy R. K. (2023). Body image distortion. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing.

25

Jiotsa B. Naccache B. Duval M. Rocher B. Grall-Bronnec M. (2021). Social media use and body image disorders: association between frequency of comparing One’s own physical appearance to that of people being followed on social media and body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18:2880. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062880

26

Kaewpradub N. Kiatrungrit K. Hongsanguansri S. Pavasuthipaisit C. (2017). Association among internet usage, body image and eating behaviors of secondary school students. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry29, 208–217. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216092

27

Khan B. Avan B. I. (2020). Behavioral problems in preadolescence: does gender matter?PsyCh J9, 583–596. doi: 10.1002/pchj.347

28

Kleemans M. Daalmans S. Carbaat I. Anschütz D. (2018). Picture perfect: the direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychol.21, 93–110. doi: 10.1080/15213269.2016.1257392

29

Lindberg S. M. Shibley Hyde J. McKinley N. M. (2011). Objectified body consciousness scale for youth. APA PsycTests.

30

Littleton H. L. Axsom D. Pury C. L. S. (2005). Development of the body image concern inventory. Behav. Res. Ther.43, 229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.006

31

Lüders A. Dinkelberg A. Quayle M. (2022). Becoming “us” in digital spaces: how online users creatively and strategically exploit social media affordances to build up social identity. Acta Psychol.228:103643. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103643

32

MacCallum F. Widdows H. (2018). Altered images: understanding the influence of unrealistic images and beauty aspirations. Health Care Anal.26, 235–245. doi: 10.1007/s10728-016-0327-1

33

Martinac Dorčić T. Smojver-Ažić S. Božić I. Malkoč I. (2023). Effects of social media social comparisons and identity processes on body image satisfaction in late adolescence. Eur. J. Psychol.19, 220–231. doi: 10.5964/ejop.9885

34

Mccabe M. Ricciardelli L. (2005). A longitudinal study of body image and strategies to lose weight and increase muscles among children. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol.26, 559–577. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2005.06.007

35

Meier E. P. Gray J. (2014). Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw.17, 199–206. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2013.0305

36

Mendelson B. K. Mendelson M. J. White D. R. (2001). Body-esteem scale for adolescents and adults. J. Pers. Assess.76, 90–106. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7601_6

37

Mesce M. Cerniglia L. Cimino S. (2022). Body image concerns: the impact of digital technologies and psychopathological risks in a normative sample of adolescents. Behav Sci12:255. doi: 10.3390/bs12080255

38

Modrzejewska A. Czepczor-Bernat K. Modrzejewska J. Roszkowska A. Zembura M. Matusik P. (2022). #childhoodobesity – a brief literature review of the role of social media in body image shaping and eating patterns among children and adolescents. Front. Pediatr.10:993460. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.993460

39

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al . (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJn71:71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

40

Papaioannou T. Tsohou A. Karyda M. (2021). Forming digital identities in social networks: the role of privacy concerns and self-esteem. Inf. Comput. Secur.29, 240–262. doi: 10.1108/ICS-01-2020-0003

41

Revranche M. Biscond M. Husky M. M. (2022). Lien entre usage des réseaux sociaux et image corporelle chez les adolescents: Une revue systématique de la littérature. L'Encéphale48, 206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2021.08.006

42

Sagrera C. E. Magner J. Temple J. Lawrence R. Magner T. J. Avila-Quintero V. J. et al . (2022). Social media use and body image issues among adolescents in a vulnerable Louisiana community. Front. Psych.13:1001336. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1001336

43

Samari E. Chang S. Seow E. Chua Y. C. Subramaniam M. Van Dam R. M. et al . (2022). A qualitative study on negative experiences of social media use and harm reduction strategies among youths in a multi-ethnic Asian society. PLoS One17:e0277928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277928

44

Scully C. McLaughlin J. Fitzgerald A. (2020). The relationship between adverse childhood experiences, family functioning, and mental health problems among children and adolescents: a systematic review. J. Fam. Ther.42, 291–316. doi: 10.1111/1467-6427.12263

45

Shen J. Chen J. Tang X. Bao S. (2022). The effects of media and peers on negative body image among Chinese college students: a chained indirect influence model of appearance comparison and internalization of the thin ideal. J. Eat. Disord.10:49. doi: 10.1186/s40337-022-00575-0

46

Swami V. Frederick D. A. Aavik T. Alcalay L. Allik J. Anderson D. et al . (2010). The attractive female body weight and female body dissatisfaction in 26 countries across 10 world regions: results of the international body project I. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull.36, 309–325. doi: 10.1177/0146167209359702

47

Thai H. Davis C. G. Mahboob W. Perry S. Adams A. Goldfield G. S. (2024). Reducing social media use improves appearance and weight esteem in youth with emotional distress. Psychol Pop. Media13, 162–169. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000460

48

Thomas F. Cash: Body image assessments: MBSRQ. (n.d.). Available at:http://www.body-images.com/assessments/mbsrq.html (Accessed December 13, 2023).

49

Thompson J. Heinberg L. Tantleff-Dunn S. (1991). The physical appearance comparison scale. Behav. Ther.14:174.

50

Tiggemann M. Slater A. (2014). NetTweens: the internet and body image concerns in Preteenage girls. J. Early Adolesc.34, 606–620. doi: 10.1177/0272431613501083

51

Tomas-Aragones L. Marron S. (2014). Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Dermato Venereol.1:368. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2368

52

Truby H. Paxton S. J. (2008). The Children’s body image scale: reliability and use with international standards for body mass index. Br. J. Clin. Psychol.47, 119–124. doi: 10.1348/014466507X251261

Summary

Keywords

social networks, body image, preadolescence, adolescence, literature review

Citation

Digennaro S and Tescione A (2024) Scrolls and self-perception, navigating the link between social networks and body dissatisfaction in preadolescents and adolescents: a systematic review. Front. Educ. 9:1390583. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1390583

Received

23 February 2024

Accepted

04 April 2024

Published

15 April 2024

Volume

9 - 2024

Edited by

Yurena Alonso, University of Zaragoza, Spain

Reviewed by

Rosendo Berengüí, Catholic University San Antonio of Murcia, Spain

Filiz Adana, Adnan Menderes University, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Digennaro and Tescione.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessia Tescione, alessia.tescione@unicas.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.