- Project Zero, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA, United States

Character education is a priority for many schools and teachers, with several prominent frameworks concerning the philosophy and practice of character and virtues in the field of education. Educators are often prepared to teach character through training programs and professional development. Yet there has been less attention to the possible role of Communities of Practice (COPs) in fostering teacher effectiveness, particularly for the encouragement of character development in adolescents. In a study of a global community of practice, 80 primarily secondary school educators were responsible for implementing a set of at least twelve 45-min lesson plans. The lessons were focused on exploring the meaning of “good work” through the lenses of excellence, ethics, and engagement, with associated character strengths embedded within the curriculum. Educators rated their feelings about whether their students would develop each of the 24 VIA character strengths in a pre-, mid-, and post-survey. They also completed a post-survey rating scale about their experiences in the Community of Practice. Two multilevel models were run to analyze the relationship between these two factors. Results demonstrated that educators who rated their Community of Practice experience highly were also more likely to believe that their students were developing a blend of character strengths from the start. Furthermore, for some additional strengths, educator confidence in students’ development grew significantly over time in a positive association with higher Community of Practice ratings. The findings suggest that Communities of Practice may be an effective format to support educators in developing their confidence and teaching practices for character education.

Introduction

Student growth in strengths such as curiosity and bravery (Peterson and Seligman, 2004) is an important goal of formal education. Across the globe, efforts to describe the skills, competencies, and attributes children will need to thrive and flourish in life are currently a primary focus of education, including the OECD’s global Learning Compass of life skills for collective well-being (OECD, 2019), the U.S.-based CASEL’s framework of social-emotional competencies (CASEL, 2020), or the UK-based Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtue’s four-tier framework of character development (Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham, 2022). Here, we draw on character terminology specifically, given our project’s historical basis in the closely aligned fields of ethical and values-based education (Berkowitz, 2002).

In the United States, character education has emerged as an important priority: nearly two decades ago the U.S. Department of Education (2005) identified character education as a “shared responsibility.” While no federal-level regulations require character education, many U.S. states have passed character education requirements for their schools. Only six states currently do not have any policy that addresses learning devoted to social–emotional or character concerns (Kim, 2023; National Association of State Boards of Education, 2024).

Yet many questions remain about the best ways to foster character strengths, particularly in terms of pedagogical strategies for teachers, who are on the front lines of guiding young people in their development. Training programs for educators often do not provide enrollees with effective character education preparation and have not closed the gap between scholarship and practice (Walker et al., 2015). In order to facilitate greater knowledge-sharing about what works in character education, Communities of Practice (COPs) (Wenger, 1998) between established educators would seem to be a promising method of encouraging learning and increasing participant self-efficacy (e.g., Kelley et al., 2020). However, COPs remain underexplored in relation to character education priorities and outcomes, and there is no current body of evidence suggesting that COPs can support educators in achieving their character goals. In an international COP described herein, which included dozens of teachers and focused on the discussion and improvement of a set of character-related lesson plans, researchers explored whether participating in a Community of Practice may have influenced teachers’ expectations of and confidence in student character strength growth.

Questions regarding the role of education in shaping individuals to be “good,” as people and as citizens, have been debated for millennia. Aristotle’s propositions regarding virtue ethics (Kraut, 2022) have remained influential in Western discourse, particularly regarding the understanding and cultivation of the traits that characterize a good and moral person. Building upon the legacy of Aristotelian thought, a wide body of scholarship has proposed that there are four types of character virtues1 necessary for the development of phronesis, a meta-virtue of practical wisdom to act with good sense. These four categories of virtues are intellectual (for discernment and pursuit of truth or knowledge), moral (for ethical decision-making), civic (for responsible citizenship and the common good), and performance (for enabling the three other categories) (Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham, 2022). Particular virtues have been grouped by Peterson and Civil (2022) within each of the four overarching categories. For example, community awareness and tolerance are civic strengths, while curiosity and reflection are Intellectual strengths.

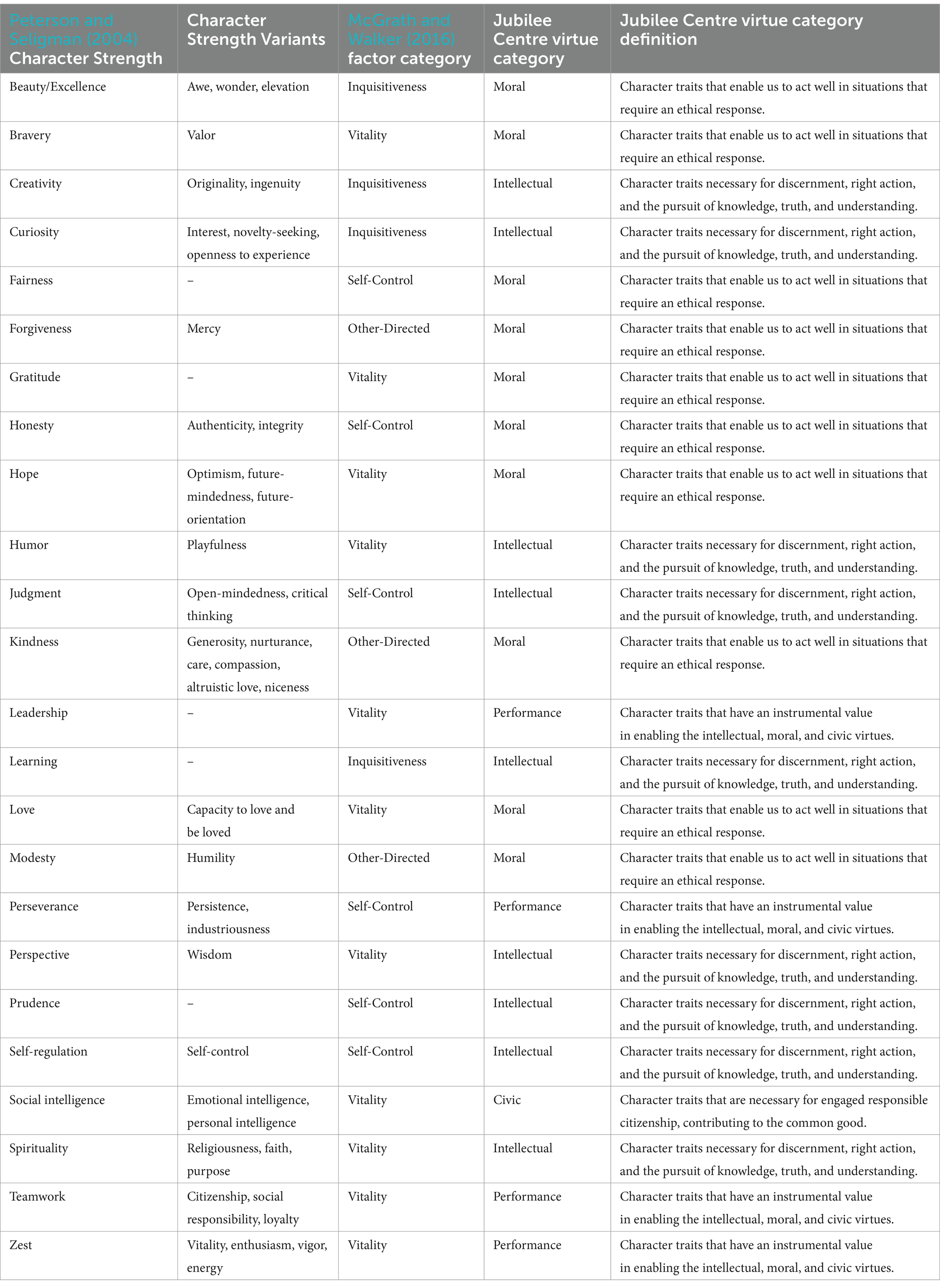

Alternatively, other taxonomies have organized the virtues and character strengths, along with their meta-categories, in ways that may or may not align with the Aristotelian tradition. An influential model is the VIA Character Strengths (VIA Institute on Character, 2024a), which includes 24 items such as fairness, honesty, and leadership (Peterson and Seligman, 2004) that are purported to be common across cultural traditions. The VIA Character Strengths have been developed into a series of widely-used measures in the form of self-report surveys composed of Likert-scale ratings (VIA Institute on Character, 2024b). Multiple studies have attempted to factor analyze the VIA Character Strengths assessments, most often the VIA Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS) (McGrath, 2014). In developing a youth version of the VIA assessment intended for ages 10–17, Park and Peterson (2006) found four overarching factors of character: temperance, intellectual, theological/transcendent, and other-directed. Mapping these factors onto the four categories from the Aristotelean virtues literature, temperance character theoretically pairs with performance virtues, intellectual character with intellectual virtues, theological character with moral virtues, and other-directed character with civic virtues. Subsequent research has continued to complexify the several factors of the VIA character assessments for youth. One relatively recent study proposed four factors of (1) intellectual control/inquisitiveness strengths (such as curiosity and love of learning), (2) behavioral and self-control strengths (such as judgment and perseverance), (3) vitality strengths, defined as those involving engagement in the world (such as gratitude and hope, and (4) other-directed strengths, defined those involving as concern for others over the self (such as forgiveness and modesty) (McGrath and Walker, 2016). For further comparison of the VIA character model from McGrath and Walker (2016) and the Aristotelian model from the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, see Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of Peterson & Seligman (2004) Character Strengths with McGrath and Walker (2016) and Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues Frameworks

The educational experiences and pedagogy that support these virtues and character strengths is termed “character education.” Character education has been defined by Berkowitz et al. (2012) as “the intentional attempt in schools to foster the development of students’ psychological characteristics that motivate and enable them to act in ethical, democratic, and socially effective and productive ways,” a widely-used definition in the field that emphasizes the interpersonal nature of character formation. Character education has long been identified as important priority for many educational systems and schools, especially in the United States (Damon, 2002; Smith, 2013; Watz, 2011). Central features of prototypical character education programs include a school basis, structure, and focus on specific psychological strengths, identity, moral and holistic growth, and development of practical wisdom as a meta-virtue (McGrath, 2018). Additionally, recent scholarship supports the notion that there are developmental differences in the evolution of character strengths and virtues that call for targeted educational interventions and practices with adolescents (Brown et al., 2020).

Notably, international organizations that influence educational scholarship and policy have often not named character education specifically as a priority, instead tending to focus more on overarching goals of educational access and competency development within target areas. For example, the OECD Learning Compass 2030 (OECD, 2019) has knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values as its four directional cornerstones for the achievement of well-being and a better world, with “core foundations” for learners in literacy and numeracy, data and digital literacy, physical and mental health, and social and emotional skills. The UNESCO Education 2030 Incheon Declaration (UNESCO, 2015) foregrounds “inclusive and equitable quality education” and “lifelong learning opportunities” within the context of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Its vision is driven by a commitment to public access, gender equality, and learning at all ages with recommended implementation strategies by governments, civil society organizations, and other stakeholders. Similarly, the UN’s more recent Report on the 2022 Transforming Education Summit (United Nations, 2023) outlined support for “all learners” and educators, the digital revolution, and investment in educational systems as crucial priorities for the world’s governments. Character education, while unmentioned, is complementary to these goals, as learners are called upon to develop and demonstrate character virtues and strengths like curiosity and kindness that will allow them to contribute to the visions put forth by the OECD and UN bodies as lifelong learners who are able to realize their own well-being and that of their communities. Thus, the scope of this paper most directly addresses character education, which can address the gap between traditions in virtue ethics and modern educational priorities identified by international bodies, offering a lens through which educators can contribute to the achievement of ideals of access, equity, and social skill development in classroom settings.

Multiple well-known frameworks promote research-based guidelines about how to best implement a culture of character within learning environments and institutions. For example, the neo-Aristotelian focused Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues (2017) has proposed that character should be conveyed in ways that are “caught,” “taught,” and “sought” by and for students. Character.org (n.d.), a non-profit advocating for character education that maintains a network of “Schools of Character,” offers 11 Principles for creating a culture of character, including identification of core values, caring attachments and relationships, and the prioritization of intrinsic motivation. The moral psychology-based PRIMED model (Berkowitz, 2021) similarly suggests that character education is successful when it satisfies the six characteristics in its acronym: Priority, Relationship building, Intrinsic motivation, Modeling goodness, Empowering students, and Developmental Pedagogy.

Teachers entering into or already working in the field may or may not be prepared by teacher preparation programs and professional development to integrate character education into their practices. In fact, teacher training programs and accreditation standards may neglect character, virtues, and morality altogether despite the omnipresence of moral signals present in the hidden curriculum of schools (Lapsley and Woodbury, 2016). Even though university-level teacher training programs have not uniformly implemented courses in character education practices, undergraduate training for future teachers may be particularly effective compared to staff development workshops in improving instructional efficacy (Ledford, 2011).

Although uptake is not universal, character-related training programs for in-service teachers are prevalent within American schools today; these include positive psychology programs offered by organizations such as Character Counts! (2024a), Greater Good in Education (2024), and Character Strong (n.d.), which seek to ready teachers to employ certain classroom practices and pedagogy guidelines for effective character education. A number of these programs appear to focus on specific interpersonal, moral, and social–emotional characteristics and dimensions that are often at the forefront of character education movements, including respect and care (Character Counts!, 2024b), kindness (Be Kind People Project, 2024), morality and values (Greater Good Science Center, 2024), and practitioner strategies and role modeling (University of San Diego, 2024). By contrast, programs that deal specifically with intellectual character strengths, such as reflection and critical thinking (Frey, 2022), appear to be less of a focus in character and virtue-related professional development programs for educators. (The curriculum that educators used in this study, which foregrounds slow reflection and critical thinking as skills on a pathway to doing excellent, ethical, and engaging work, may have been particularly desired by educators seeking more of a focus on intellectual character strengths).

Because character-related training often occurs in standalone workshop sequences, courses, or as a component of for-credit educational courses, relatively little research has considered the role of ongoing, long-term Communities of Practice (COPs) in fostering character virtues in educational contexts or for educators’ pedagogical development over time, which is especially true regarding connections between COP participation and impacts on character change in learners (Allman et al., 2024; Tichnor-Wagner, 2022). A COP is defined as a gathering of people “who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015). COPs are similar to Professional Learning Communities (PLCs). While the terms COP and PLC may sometimes be used interchangeably, COPs tend to focus more on grassroots leadership rather than an external facilitator and also on the improvement of practice itself rather than institutional alignment (Blankenship and Ruona, 2007).2 The terms are therefore not interchangeable, but whether a group is called a COP officially or not, and whether membership is formal or informal, a COP is a group that focuses on the intersection of 1) a domain, 2) a practice, and 3) a body of expertise. COPs therefore include three concurrent dimensions: “mutual engagement” in the form of interaction with other members to form a “shared meaning”; joint enterprise, by working together towards common ends; and shared repertoire, the “resources and jargons” that allow participants to interact and learn (Li et al., 2009). Trust and Horrocks (2019) found six features of an effective COP in their work with the Discovery Educator Network of K-12 educators and staff, namely leadership roles (with key functions to motivate others and serve as role models), personalized learning (differing from traditional professional development opportunities), guiding principles (including expectations about behavior), organizational support (such as infrastructure and staff), social learning (sharing expertise between and among others), and purpose (a clear mission aligned with needs).

In education, COPs have been employed for a variety of applications and purposes, including to enable teachers in the development of effective pedagogical practices and to support strengthened student learning outcomes (Brandon and Charlton, 2011; Herbers et al., 2011; Jimenez-Silva and Olson, 2012; Lomos et al., 2011; Smith and Becker, 2021). These studies have often looked at specific COPs within a disciplinary or national context. For example, a study of Malaysian secondary school teachers of English, science, and mathematics found that an online COP was effective at facilitating continuous learning (Khalid et al., 2014), while research with pre-service Turkish teachers in math and science found a positive association between self-efficacy and online COP participation (Ekici, 2018). In addition, a set of studies have demonstrated that educator COPs, including in online modalities, have had an impact on participants’ feelings of confidence or self-efficacy (e.g., Polizzi et al., 2021).

Perceived self-efficacy is defined by Bandura (1994) as “people’s beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance” that influence their lives. In particular, teacher self-efficacy has been defined as a teacher’s belief or judgment of “his or her capabilities to bring about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning” (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). Tschannen-Moran and Hoy’s teaching self-efficacy psychological scale, one of the most used to evaluate the construct, measures whether a teacher feels that they can differentiate instructional strategies, manage their classroom, and engage their students (Morris et al., 2017; Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). Extant research has demonstrated that teachers high in teacher self-efficacy tend to be more open to new teaching ideas and methods (Hussain and Khan, 2022; Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998; Zee and Koomen, 2016). Moreover, although a significant body of work has explored the relationship between teacher self-efficacy and positive student outcomes (Kim and Seo, 2018; Klassen and Tze, 2014; Künsting et al., 2016; Zee and Koomen, 2016), literature remains mixed regarding these potential positive associations (Jerrim et al., 2023; Lauermann and ten Hagen, 2021; Shahzad and Naureen, 2017; Mojavezi and Tamiz, 2012; Tai et al., 2012).

Relatedly to educator self-efficacy, teachers’ beliefs and expectations related to their students has also been the subject of study. There is a large extant body of work regarding teachers’ expectations or beliefs in their students’ abilities and outcomes (de Boer et al., 2018; Jacobs and Harvey, 2010; Rubie-Davies, 2010; Rubie-Davies et al., 2011). For example, the “Pygmalion” effect, better known as the self-fulfilling prophecy, has been established in education (Rosenthal and Jacobson, 1992), wherein teachers who were induced to have higher expectations for their students in turn had students who achieved greater academic growth, regardless of initial levels of student achievement. Importantly for the current study, research has shown that there is a positive correlation between teacher self-efficacy and teachers’ expectations for their students (Rodriguez, 2014). Kim et al. (2023) found a positive correlation between teacher efficacy and teacher expectations in a sample of Korean educators, particularly when accounting for teachers’ beliefs about the efficacy of their students’ parents. To date, only a small body of research has explored the relationship between teacher efficacy and teacher belief or expectations (Summers et al., 2017; Warren, 2002).

Current debates surrounding the role of teacher self-efficacy in promoting positive outcomes indicate a need for deeper analysis of this relationship, particularly within the context of educators participating within COPs who may derive various forms of support and reinforcement from such a group of peers. As character education frameworks (e.g., PRIMED) call for character to become a shared priority within faculties and schools, COPs are structures that would appear to benefit educators in directing them towards common goals by establishing connections with one another using the “shared repertoire” of character scholarship and taking part in social learning together (Li et al., 2009). COP learning may in this way allow educators to better hone and implement their character education goals and pedagogical routines via social learning. Morris et al. (2017) observed that a major category of efficacy-relevant experiences involved social persuasion, the type of learning that COPs may facilitate. In one study, Yoon and Armour (2017) reported on a COP among physical education teachers in South Korea who were implementing a new national curriculum with the aim of transferable character development. While the community structure aided teachers in their own learning about teaching in practice, evidence was limited regarding impact on students’ transferable character growth and skills, which remains an area for further exploration regarding the features of COPs that may support not only educator participant learning but student learning in turn. Long-running programs, such as those out of the University of St. Louis’s Center for Character and Citizenship (Dabdoub et al., 2023), as well as university programs have prepared school leaders to build cultures of character in their schools. However, studies of the effectiveness of these programs are not yet published, nor do some of them function as sustained COPs that could expect to have a long-term impact on teachers’ group learning and expertise once they are in the field, which requires individual commitment (Mak and Pun, 2015).

The present study seeks to add to understanding about how COPs may influence teachers’ feelings of effectiveness in fostering character outcomes in students. The core research questions of this study included:

1. What associations may be present between educators’ quality of participation in a COP focused on character education and their expectations of the growth of their students’ character strengths?

2. Which character strengths do educators believe their pedagogy most influences when teaching a curriculum designed to foster character strengths in students?

The COP in this study was comprised of a diverse group of worldwide educators who implemented a set of lesson plans in their classrooms during the course of one academic year. Members contributed two sources of data analyzed in this paper. First, teachers were surveyed regarding their expectations of student change in character strengths three times over the course of one academic year. While teacher self-efficacy in their teaching abilities was therefore not directly measured, expectation of students’ development of character strengths may serve as one indicator of teachers’ perceived self-efficacy in their classrooms. Second, teachers rated their COP experience at the conclusion of the academic year. The implications of this study have wide applicability for people working on COPs in education and in other sectors. In particular, researchers seeking to further understand the relationship between involvement in a sustained community focused on character-related topics and teacher expectations of outcomes may be particularly interested in this work.

Materials and methods

Study background

The COP we describe is a component of a multi-year research project in which participants implemented at least 12 of a set of 16 lesson plans, organized into four thematic units, within their classrooms. The lessons are focused on a framework of “good work” developed by The Good Project, a research initiative at the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s Project Zero. Based on extensive qualitative interviews of professionals across 10 domains beginning in the mid-1990s, “good work” involves three elements: excellence (technical proficiency), ethics (social responsibility and attention to consequences), and engagement (meaning or purpose) (Gardner et al., 2002; Gardner, 2010). The lessons, developed between 2019 and 2021 with a secondary school student audience in mind, cover the components of “good work” and related concepts, including explorations of values, competing and overlapping responsibilities, and alignment and misalignments between group perspectives (The Good Project, 2024a,b). Each lesson is structured for a recommended time period of 45 min and typically involves an introduction to an idea, an interactive discussion, and personal application exercises and prompts.3

In developing the materials, learning principles including perspective-taking and metacognitive reflection were incorporated to ensure students have opportunities for personal growth. For example, students build a portfolio of artifacts generated during the learning journey and complete a series of four self-assessments concerning their achievement of specific learning goals. The theory of change underpinning the lessons is that students will develop their conceptions of how to do “good work” in ways that are aligned with character and virtue strengths, including how to act with integrity, attention to personal principles, and a commitment to social wellbeing of proximal and distant others (The Good Project, 2024a,b). For instance, in Lesson 3.2, students have the opportunity to consider their values in practice, including real-life instances in which they have acted in accordance with their values, and to then explore how values intersect with the concept of engagement by considering a dilemma narrative. Ideally, by taking part in the lesson plans activities, students will develop skills and repertoires to be able to do “good work” in their present and future lives and to flourish in their futures, individually and collectively. The Good Project’s curriculum most aligns with the principles from character frameworks that emphasize the development of intrinsic motivation, empowerment, and development of a set of core values (Character.org, n.d.; Berkowitz, 2021). Note that this paper does not take into consideration student-centered results.

Educator participants in the research project were invited to fulfill three distinct roles across the duration of their involvement: (1) subjects of data collection (e.g., by completing surveys); (2) facilitators of data collection (e.g., by distributing surveys to their students for completion); and (3) members of the COP (e.g., by attending synchronous meetings). Educators were identified via an open recruitment process involving both paid and free social media posts on multiple platforms (Facebook and Twitter/X), website posts (on The Good Project’s website homepage), and network outreach. Educators willing to take part in the project were screened for inclusion eligibility and required to certify in advance that they could reasonably expect to be able to complete the required research procedures, including remaining active in the COP by attending monthly meetings and regularly posting on the Slack communication platform where the COP was launched. Members were required to attend or to comment asynchronously on the video recordings of the COP meetings for at least 8 of the 10 meetings, as well as to check the Slack platform on a weekly basis for announcements and exchange of ideas. Optional professional development sessions were also provided for COP members by The Good Project research team regarding particular core concepts covered in the lesson plans that were being implemented. The COP began in August 2022 to coincide with the start of the 2022–2023 academic school year in the United States. Due to the global nature of the COP membership, all activities were conducted virtually. Technological barriers to entry were low for educators, as all had some experience using virtual meeting and discussion technologies during the COVID pandemic.

Over the course of the 2022–2023 academic school year, COP members were expected to be present at monthly, 1-hour gatherings of the full group, which were held synchronously on Zoom. These meetings were initially led largely by the research team and later by COP members themselves and involved presentations of core concepts and ideas (e.g., modeling of a lesson plan) as well as discussion time for attendees to connect in small breakout groups. Members who were unable to attend live versions of these meetings were required to participate in asynchronous discussions in corresponding Slack channels by completing discussion posts.

In between monthly meetings, Slack announcements and conversation occurred organically and as directed by the study team. Monthly discussion prompts were announced in order to stimulate discussion and sharing of ideas. Nine of the COP members were designated as “Champions” who were responsible for overseeing contributions and discussion within the Slack community, including acting as a resource to other members and for monitoring progress in the research process. Champions also oversaw virtual “study groups” of approximately 10 COP members each. The study groups functioned as more intimate discussion and bonding spaces than would be possible in full-group conversation. In return for their investment of time, COP members and Champions received a stipend at the conclusion of the academic year if they had fulfilled the requirements of participation.

The described COP functioned in ways that fulfilled the dimensions of effective COPs described in the literature, including a defined focus on a domain (character education and the future of work), centrality on a practice (pedagogy in educational environments with students), and a body of expertise (cultivating virtues around the achievement of “good work”) (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015). The COP facilitated consistent interactions between members aimed at common goals for student outcomes and the use of a common vocabulary (Li et al., 2009). This particular COP also built upon Trust and Horrocks (2019) COP features via the assignment of leadership roles, ability for participants to receive personalized advice, a set of guiding principles and expectations for participation, a support staff in the form of The Good Project research team, social learning via shared experiences, and definition of a clear mission. These elements distinguished the COP from other types of working groups.

Sample

Members of the COP were diverse in terms of the grades that they taught, the types of schools that they were within, and their geographic locations. Between August 2022 and June 2023, The Good Project’s COP was made up of approximately 80 self-selected educators total, 64 of whom were still considered active members by the conclusion of the period. The 64 educators represented 30 separate schools and institutions (although two overarching school networks were represented by three schools each). Below is a breakdown of geographic and grade composition of the membership.

• Countries Represented: Albania (5 teachers), Canada (1), Colombia (2), Croatia (2), Guatemala (1), India (22), Jordan (1), Mexico (1), Nigeria (1), Poland (5), Romania (1), South Africa (5), Spain (4), Turkey (7), United Arab Emirates (1), United States (5)

• Grade Levels Represented: Middle School (4), Secondary School (53), University (7)

All study procedures were conducted in English, as teacher participants were required to certify their and their students’ proficiency in the English language. Schools represented by the educators in the study included both public/state-run and private institutions. Due to inconsistencies between national systems and gaps in knowledge about schools’ admissions processes, we do not provide a breakdown of the exact number of private and public schools here. Educators had a range of teaching experience, with the majority having been teachers for at least 5 years.

Participants in the research completed an informed consent process. All teachers in the COP who were members of the research completed a consent form that documented their agreement to take part in research procedures. Participants contributed their data on surveys in identifiable format using their name for tracking and matching purposes over the three survey time points. Data was then anonymized and analyzed. The research was subject to review by the Harvard University Committee on the Use of Human Subjects and data safety review and was compliant with the European Economic Area’s GDPR data safety standards.

Methods

The mixed-methods research project used a convergent parallel theoretical tradition in which qualitative and quantitative data are collected and analyzed separately at the same time, with results compared to draw conclusions (Creswell, 2014). Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2013) was used for qualitative data. In particular, the quantitative methods and data presented in this paper are meant to provide insight into the observable statistical relationship that may exist between COP experiences and member beliefs about their teaching practice. While these methods may not be able to provide a nuanced portrait of the interpersonal learning and subsequent emergent impacts of the COP, the current paper focuses on one dimension of the COP that the quantitative data supports may have been important for their teaching practice.

Participants completed a series of data collection and community involvement procedures, which, as noted, COP members were responsible for completing, facilitating, or participating in across the 2022–2023 school year (Note that the findings in this paper are based on Year 1 of the COP research activities; the COP and research activities continued into the 2023–2024 school year, during which data collection procedures differed slightly). For this paper, the following procedures are salient, involving teacher-level data4:

• A pre-survey, midpoint survey, and post-survey at the beginning, middle, and end of their engagement with the lesson plans. These surveys were intended to take approximately 20 min to complete and included both closed and open-ended questions regarding familiarity with the lesson concepts, typical classroom experiences, ratings of the study experience, character strength development questions, and demographic indicators. Survey questions were both self-developed by the research team and based upon preexisting measures from the literature (See Tables 2, 3 for a description of the measures relevant to this paper).

• Attendance at 1-hour monthly community meetings.

• Regular commentary and participation in conversations taking place on the Slack platform where the COP was hosted.

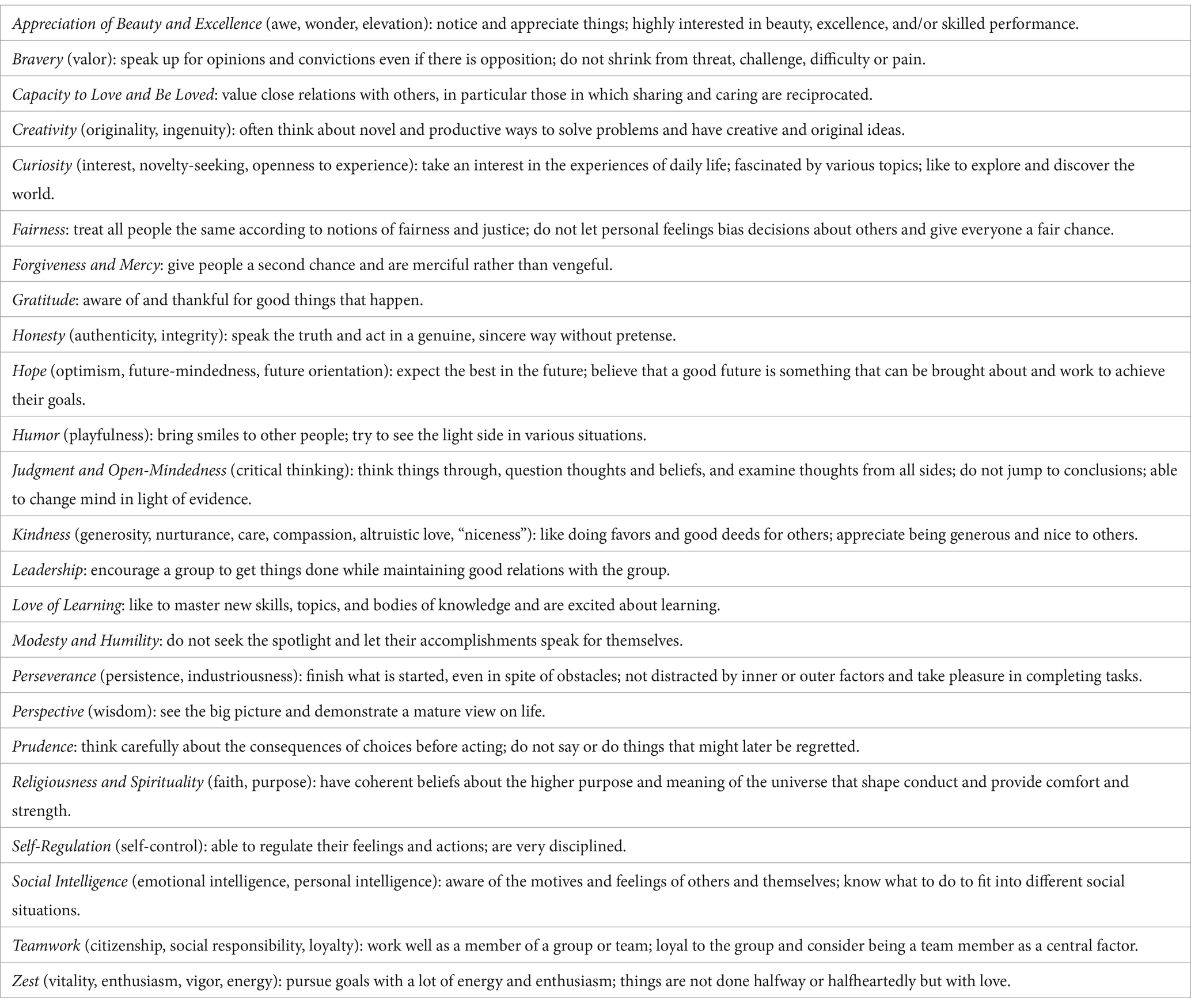

All pre-, mid-, and post-surveys included a set of character strength scale questions. The list of character strengths adapted from the Character Strengths Rating Form (CRSF) (Ruch et al., 2014), which is based on the 24 character strengths classification by Peterson and Seligman (2004), used as the basis of the VIA Character Strengths assessments. A one-sentence definition of each character strength, adapted by the researchers, was provided for each item. Teacher participants were asked to rate each character strength according to the degree of how “likely it is that you [will develop/developed] each characteristic in your students this year.” Questions were represented on a sliding scale of 0 to 10, with a score of 0 representing “very unlikely” and 10 representing “very likely.” The list of character strengths and their one-sentence definitions is displayed in Table 2. Cronbach’s alphas for the scale equaled 0.98 for the pre-survey, 0.97 for the mid-year survey, and 0.98 for the post-survey.

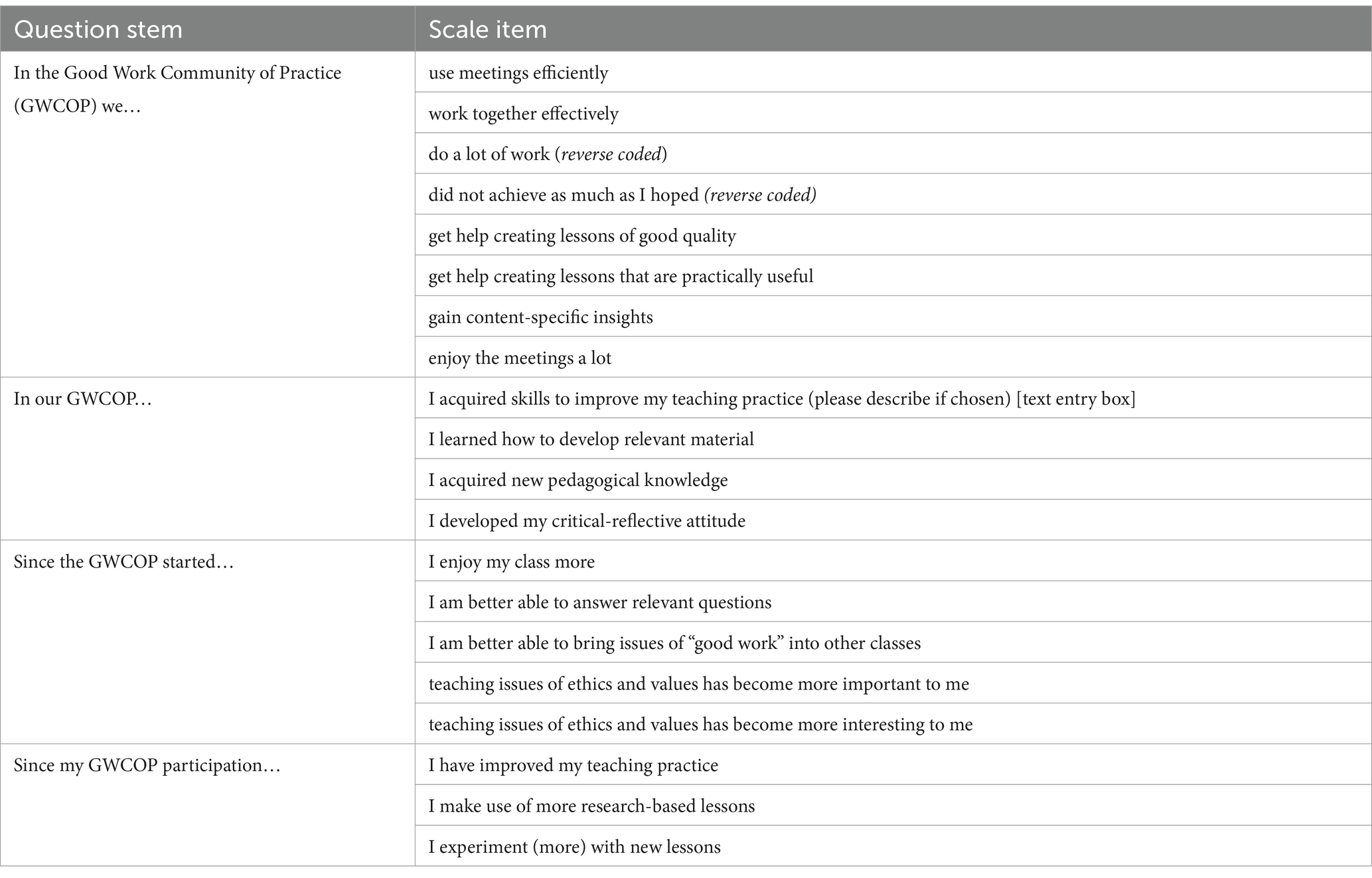

The post-survey completed by teachers, administered once they had completed at least 12 of the 16 lessons with their students, also contained a set of 20 sliding scale items that asked respondents to rate their interactions and experiences within the COP. This COP rating scale, self-developed by the research team, demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.97. Each item was rated on a sliding scale of 0 to 10, with a score of 0 representing “strongly disagree” and 10 representing “strongly agree.” The full set of items that comprised the COP rating set is displayed in Table 3.

Data analysis

A null model was run in order to establish the most appropriate analytic strategy. The equation is represented as follows:

In the model, represents the average character strength score across teachers. represents the random intercept for an individual teacher, which here indicates a particular teacher’s average deviation from the average character strength score. represents the leftover residual variance, capturing the difference between a teacher’s actual score versus their predicted score based on the model. The intraclass coefficients (ICC) for these models ranged from 0.04 for one model to 0.61, suggesting the need to account for nesting in the data (Robson and Prevalin, 2016).

Given the nested nature of the data (time, the individual Level 1 variables, nested within teachers, the group Level 2 variables), two multilevel models (Snijders and Bosker, 2011) were used to analyze the relationship across time between: (a) teachers’ pre-, mid-, and post-survey longitudinal data regarding the character strengths that they expected their students to have developed through the lesson plans, as the dependent variable; and (b) teachers’ post-survey responses (n = 75)5 to the COP rating questions, as the independent variable. The COP rating scale results, initially at a mean of 7.49 on a 10-point scale (SD = 1.98) for all participants, were mean-centered at a value of 0 for ease of interpretation (See Supplementary Table S1 for the raw mean and SD values for each COP rating scale item).

The first model estimated the relationship between educator attitudes towards COP engagement and expectations of student character growth in each of the particular 24 character dimensions that were measured. The multilevel modeling equation can be represented as follows in Model 1:

In this equation, represents the average mean of the character strength of interest across all teachers when time = 0 (the value assigned to the pre-survey) and at the mean-centered score of 0 for meanCOPscore. The slope represents the average effect of time across all teachers on their expectations for each character strength outcome (in other words, the magnitude of change in each strength over time), holding the mean COP score constant. The slope represents the average effect of being in the COP on teachers’ expectations of their students’ character change and can be interpreted as the magnitude of change in each character strength across all teachers based on each 1-point difference in the mean COP rating, holding survey time-point constant. represents the random intercept for an individual teacher, which here indicates a particular teacher’s baseline deviation from the average character strength score. represents the leftover residual variance, capturing the difference between a teacher’s actual score at one time point versus the predicted score based on the model (Snijders and Bosker, 2011).

A multilevel model was run based on the first model but with the inclusion of an interaction term between time and meanCOPscore, represented as follows in Model 2:

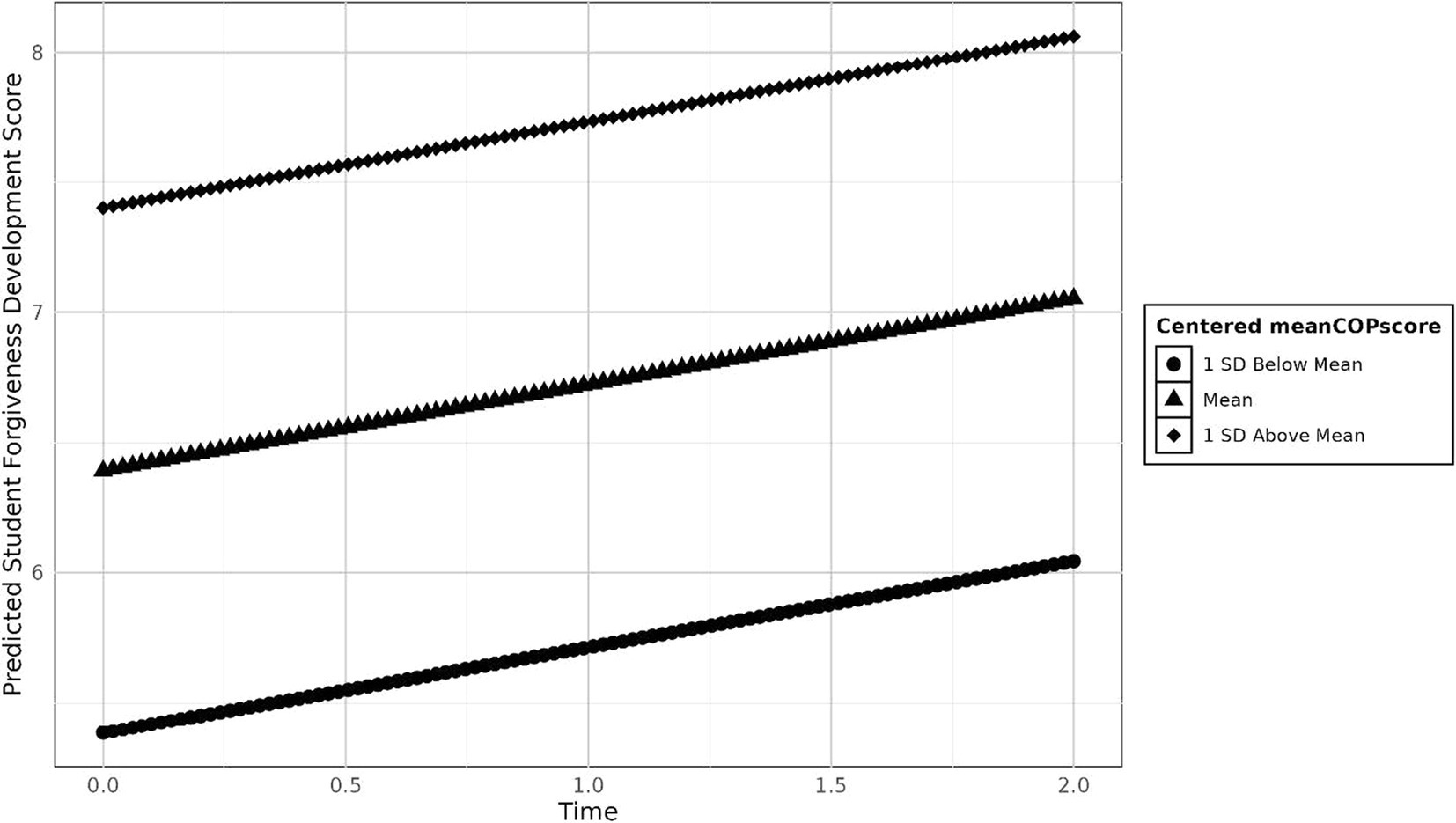

In this equation, the slope represents the interactive effect of time and meanCOPscore together on each character strength of interest; it can be interpreted as the degree to which each character strength was estimated to grow in students at different rates over time based on meanCOPscore. In other words, tells us the differential in the rate of change in educators’ expectations of student character growth over time based on each 1-point difference in time and each 1-point difference in mean COP score. In Figure 1, we explore this interaction by representing a group who scored “high” on their COP ratings (one standard deviation above the mean score) and another group who scored “low” on their COP ratings (one standard deviation below the mean score). Positive slopes signify a growing gap in expectations of student character development across the three survey time points between higher and lower COP raters. Likelihood ratio tests were conducted to determine whether Model 1 or Model 2 was a better fit for the data for each character strength (Robson and Prevalin, 2016). For each character strength, this test assessed whether the more complex Model 2 better explained the variations in the character strengths data than the simpler Model 1. When significant, the test indicated that Model 2 was a significantly better fit for the data.

Results

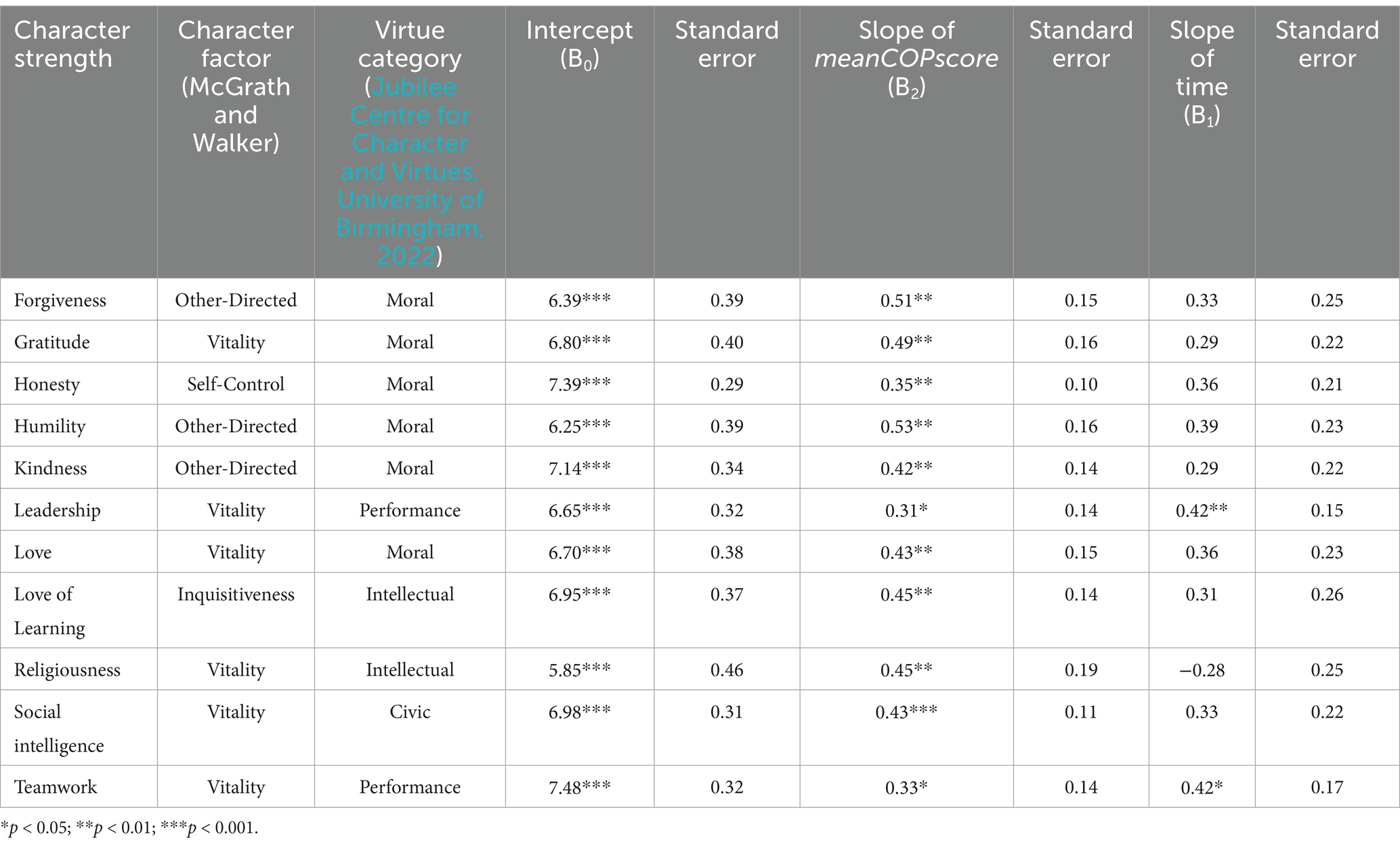

For the character strengths listed in Table 4, Model 1 was the best fit based on likelihood ratio testing, and , the slope of meanCOPscore in Model 1, was statistically significant (For the full list of results for all character strengths using Model 1, see Supplementary Table S2). This indicates that teachers who rated their experience in the COP more highly had higher expectations of their students’ growth in these character strengths on the pre-survey. Moreover, the relationship between these teachers’ COP ratings and their expectations of each character strength’s development were uniformly positive across time. Each strength is listed in the table with two categorizations. First, we include its overarching character factor as found by McGrath and Walker (2016) in their factor analysis of the VIA-Youth. Second, we include each strength’s expected virtue category from the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues framework (Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham, 2022).

Table 4. Character strengths that displayed significant relationships between COP ratings and expectations of student character growth.

For example, the results for Forgiveness (an other-directed character strength and moral virtue) demonstrate an initial estimated score of 6.39 (p < 0.001) on a 0–10 scale in terms of how likely educators believed it was that students were developing this strength through the lesson plans. The slope for meanCOPscore indicates that for every 1-point difference in educator COP ratings (on a 0–10 scale), the average expected Forgiveness development in students is estimated to be 0.51 higher (p < 0.01). In other words, educators who reported their involvement in the COP more favorably than their peers tended to believe more strongly that their students would develop the character strength of Forgiveness, with a magnitude 0.51 points greater for every 1-point increase in COP positivity. The slope of time is not significant; overall, accounting for COP scores, the data does not support that educators changed their ratings of Forgiveness development across the pre-, mid-, and post-surveys. However, teachers who started with higher confidence in student development of Forgiveness also tended to stay high.

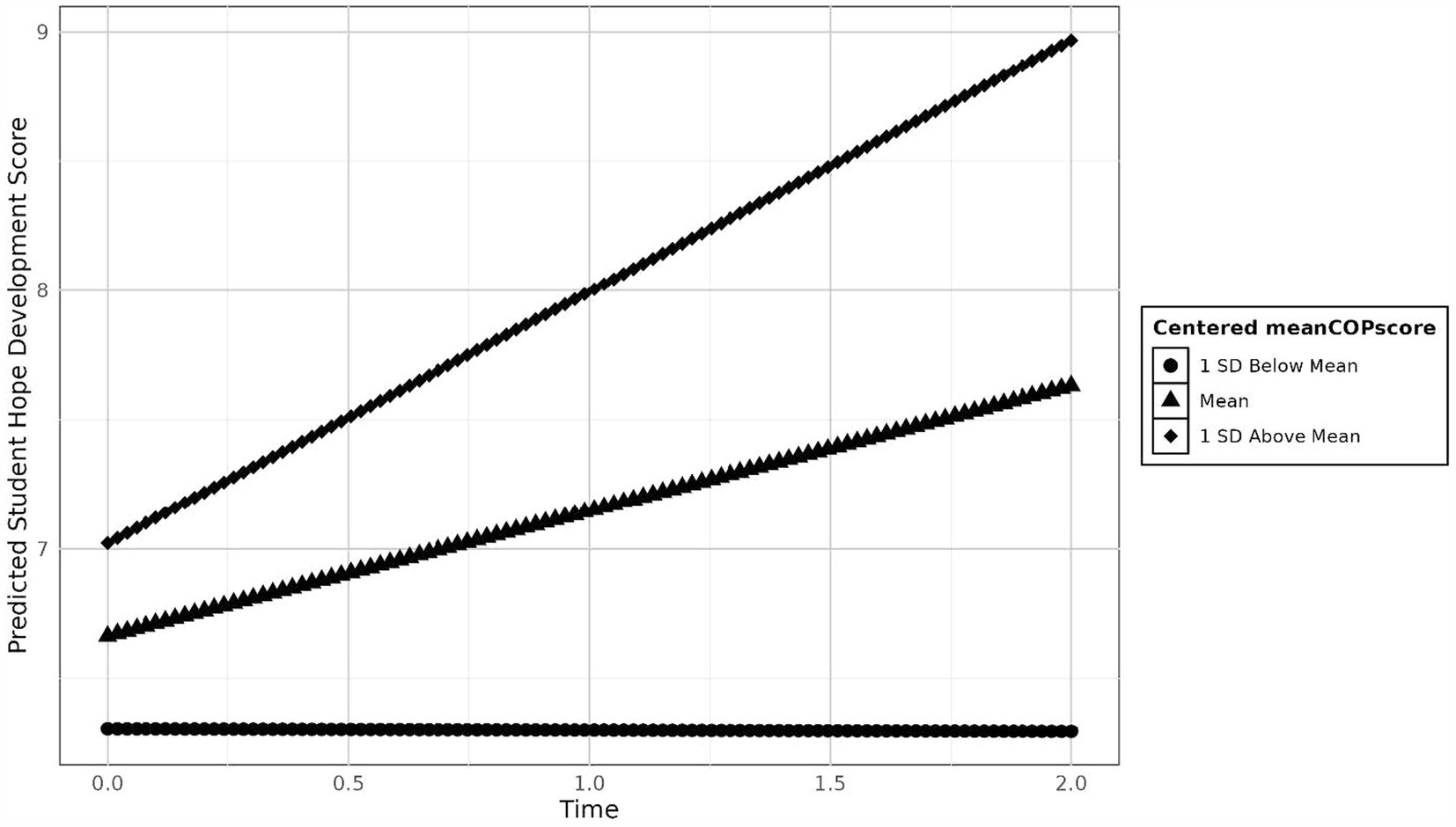

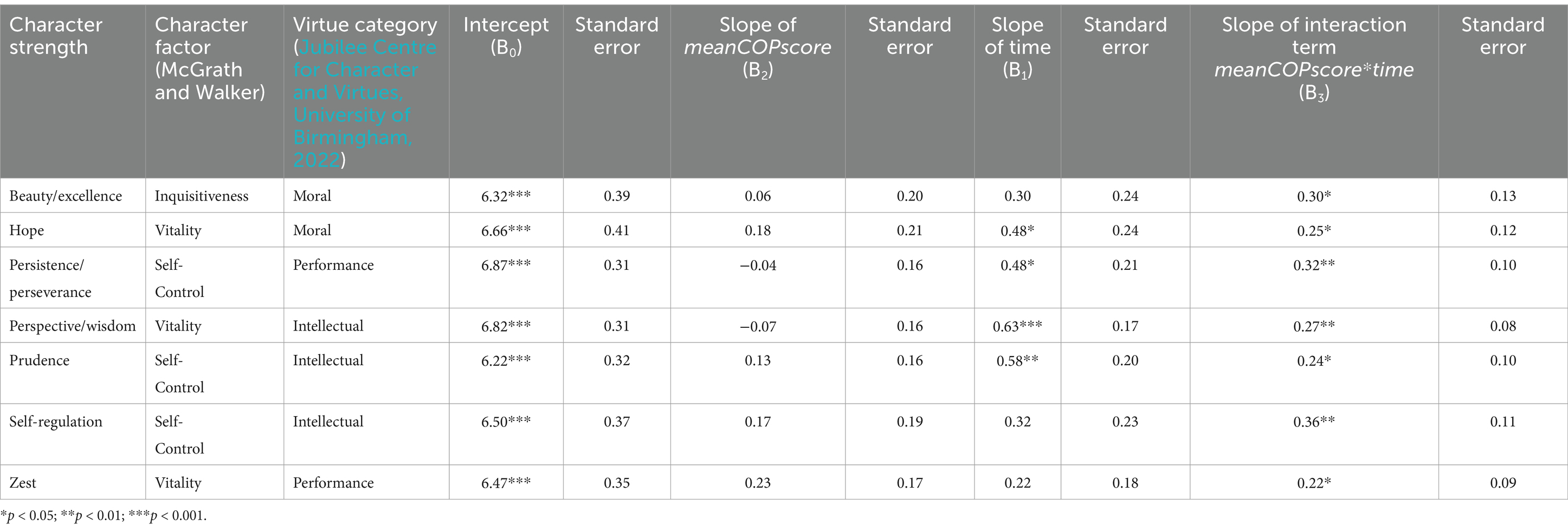

Next, using Model 2, , the slope of the interaction term time*meanCOPscore, is statistically significant for the character strengths displayed in Table 5 (For the full list of results for all character strengths using Model 2, see Supplementary Table S3). In these cases, teachers who rated the COP highly grew significantly more in their confidence that students were developing the specified character strengths over time, compared to their peers who rated the COP less highly.

Table 5. Character strengths that high COP raters were significantly more confident of growing in students than low COP raters.

For example, the results for Hope estimate an initial score of 6.66 (p < 0.001) on a 0–10 scale of educator confidence in the lesson plans developing this strength in their students. The slope of meanCOPscore is not significant; the overall mean COP ratings of the full educator group do not demonstrably influence expectations of student Hope growth. The slope of time is significant, with growth in expectation ratings of student development of Hope rising by an estimate of 0.48 (p < 0.05) points between each survey time point. The inclusion of the interaction term complexifies these results. We can assume two groups, one standard deviation above (a higher group) and one standard deviation below (a lower group) the mean centered COP score. To understand the full interaction effect, we can use these two groups and substitute appropriate values within Model 2 with the full interaction equation:

For the higher group, the values would be as follows:

At times 1, 2, and 3, Hope expectation scores for the higher group would therefore equal to 7.01, 7.99, and 8.97, respectively.

For the lower group, the values would be as follows:

At times 1, 2, and 3, Hope expectation scores for the lower group would equal 6.30, 6.29, and 6.27, respectively.

In other words, higher COP raters were increasingly more confident regarding their student character development expectations for the character strengths that had a significant interaction term in Model 2, with all estimated slope values being positive. The graph for Hope is displayed in Figure 2, with the middle line representing the estimated mean of the entire sample, along with estimates for individuals 1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean rating score.

Discussion

Instead of a uniform effect of COP ratings on all teachers’ expectations of student character growth, Model 2 suggests that the COP likely had a reinforcing or compounding effect on educators’ attitudes towards some aspects of character. For the seven strengths listed in Table 5, including Persistence/Perseverance, Prudence, and Self-Regulation, COP members who rated their experience highly were able to outpace their lower-rating peers in their confidence regarding student growth. By contrast, educators who believed the COP was less effective did not achieve the same levels of assuredness in these strengths, resulting in an increasingly prominent gap between high and low COP raters.

Given these results, it is possible that COP members who were particularly enthusiastic about their learning, as indicated by their own responses to the COP ratings, were able to reap benefits from one another that translated to more rapidly growing sense of self-efficacy in bringing about certain outcomes related to student learning (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001). In this case, educators may have developed greater self-efficacy concerning their ability to implement the lessons and to convey information about particular character and virtues to students. Throughout Year 1 of the COP, engaged participants had numerous opportunities to connect with one another, including in synchronous and asynchronous meetings and discussions on Zoom and Slack. Teachers who reported that they benefited from COP learnings therefore may have been able to learn certain knowledge or skills from other teachers and to then implement the lessons with greater self-assurance. The learnings developed through the COP, particularly related to pedagogy, lesson planning, and new knowledge that the COP rating items addressed, may have made educators more confident in their ability to cultivate certain strengths in their students.

In this respect, the results align with the vision of Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner (2015) that a COP must not only include a domain and a community but also a practice that involves the development of “shared repertoires” through “sustained interaction” and often involves “growing confidence.” Low COP raters were not able to develop these shared repertoires and did not feel as strongly that their membership was affecting their practice. The results also align with research supporting the ability of COPs generally to encourage educator self-efficacy in teaching abilities (Tam, 2015; Voelkel and Chrispeels, 2017; Zonoubi et al., 2017).

In comparison, the results of Model 1 suggest that for some strengths, educators’ attitudes were already differentiated from one another prior to their engagement in the COP. For the strengths listed in Table 4, which included Honesty, Love, and Social Intelligence, higher COP raters entered the community already more confident that students would develop these strengths. They then remained more confident than lower COP raters over time. Multiple explanations are possible to explain this trend. For example, it may be that higher COP raters were educators who were already quite involved in their classrooms and therefore believed strongly in their students’ development or had perhaps already been aware of certain character programs referenced above (e.g., Character.org). Institutionally, they may have had school cultures that supported particular character strengths (e.g., as is likely the case for participants from International Baccalaureate schools) (International Baccalaureate Organization, 2015). Alternatively, they may have been the members who were particularly convinced from the beginning that the COP was going to help them develop these particular strengths and sought out the COP for this reason, resulting in self-selection bias amongst this group.

In terms of the specific character/virtue categories that were associated with COP ratings, it appears that the COP may have been most effective at cultivating or perpetuating a belief in the ability of teachers to encourage Vitality character strengths in McGrath and Walker’s (2016) factor analysis. Out of the 11 Vitality strengths, which include Religiousness and Leadership, only Bravery and Humor did not display any statistically significant relationship to either of the two models. Thus, teachers who highly rated the COP either entered strong (Model 1) or became stronger (Model 2) in their beliefs about students developing these character strengths. Because the lesson plans that teachers were implementing included a strong ethical component, including grappling with dilemmas, it may be that the COP was able to attract teachers who were already or were then convinced to reinforce ideas about the importance of students engaging beyond themselves with the wider world. The use of dilemmas in education has a long and wide history of allowing students to grapple with real-world situations and future possibilities (Power et al., 1989; Bateman, 2015; Flanagan, 2019). As educators taught students using dilemma scenarios throughout the lesson plans, these world-engagement strengths were then perhaps prominent for highly engaged COP members in how they believed they communicated with their students.

For Model 2, the significant character outcomes (Beauty/Excellence, Hope, Persistence/Perseverance, Perspective/Wisdom, Prudence, Self-regulation, Zest) are notably tied to particular aspects of the curricular materials. The lesson plans themselves incorporate excellence, perspective-taking (with elements of social responsibility and ethical decision-making), and zest as a feeling of activation or enthusiasm. COP members who learned from the community likely believed they were developing expertise through social learning in the shared domain focus of the COP that could be shared with their students in these topics that together represent the component elements of “good work.” The Hope, Persistence, Prudence, and Self-regulation outcomes may indicate a collection of skills related to students’ ability to integrate discussions from the lesson plans with positivity, grit, and careful study.

Importantly, the VIA character strengths, McGrath and Walker’s character factor analysis, and the Jubilee Centre’s virtue taxonomy do not always neatly mirror one another, complicating the manner in which character strengths in general may be grouped (including in our own tables and appendices). For example, several of the VIA strengths, such as Hope and Religiousness, resist easy categorization as Moral, Civic, Intellectual, or Performance virtues. Additionally, the six character categories that continue to be used by the VIA assessments (Wisdom, Courage, Humanity, Justice, Temperance, and Transcendence) (VIA Institute on Character, 2024a) do not resonate with McGrath and Walker’s factors (Vitality, Self-Control, Inquisitiveness, Other-Directed). More research and scholarship are needed in order to place the various and competing character strengths and virtues frameworks in closer conversation with one another and attempt to synthesize them into a coherent meta-taxonomy.

Despite the difficulties of definitive characterization of each of the measured strengths, the results further indicate that an educator COP can be an effective mechanism of encouraging deeper self-efficacy or confidence among teachers in their practice, which in the case of this particular COP concerned their ability to teach specific character strengths to their students (see Table 5). Previous research appears not to have addressed whether these findings may be unique to COPs focused on character development themselves or whether such growth in perceived self-efficacy of teaching character would be common to educator COPs with other missions or thematic foci. Additional investigations of character-related outcomes associated with COP experiences are needed of both COPs that do and do not explicitly address character education. However, this study may indicate that COPs in character education have the potential to allow educators to refine their pedagogy, particularly when incorporating elements such as collaborative reflection, practical application solutions, and peer-to-peer support in both synchronous and asynchronous formats.

In sum, this study is important because COP participation and enjoyment has not previously been shown to amount to significant difference in teacher expectations of student character growth. The comparison between low and high COP raters that the data affords, and their difference in confidence development, allows us to speculate that educator COPs focused on character are likely to be an effective method of promoting character development in students. As the research team considers additional data collected during this study, the hope is that survey data from students may present similar trends in character strength growth, which may help to further confirm or raise deeper questions about the patterns of expected character development received from educators.

Limitations

This study includes several important limitations that may affect interpretation and the wide applicability or validity of the results. First, this study is correlational in nature and therefore cannot make any claims about the causal nature of The Good Project’s COP and its impact on teachers’ expectations for their students’ character growth. Although our results suggest that a character-focused COP may have a measurable impact on teachers’ expectations of specific elements of student character growth, further research is needed to tease apart the causal impact of COPs on teacher motivation, expectations, and beliefs. Certainly, it is possible that COPs not focused on character could potentially demonstrate similar outcomes. Furthermore, additional research is needed regarding any potential benefits to students or classroom practice as a result of these impacts on educator participants in the absence of direct measures of student outcomes in this paper.

Second, the sample of educators involved in the study were entirely self-selected, and therefore many of them were already interested in the teaching of character prior to joining the study. As acknowledged in our discussion of Model 1, the results may therefore be skewed, reflecting an existing willingness to learn about and teach character among the participants that was not fostered by the COP.

Third, the character strengths that were found to be significantly related to COP scores did not display a pattern that was always readily interpretable in relation to the concepts from the lesson plans. Strengths like love and religiousness were not foci of the COP, but results showed a significant connection between confidence in student development of these strengths and the COP ratings. The reason why these character traits in particular were significant may be due to a variety of pre-existing confounding factors that were not accounted for within the models, especially across such diverse settings and types of students as were included in the sample. For example, it is possible that educators teaching at schools with a religious component were more positive about the COP’s perceived alignment with their school missions and gave their experience higher ratings, resulting in an association between that particular character strength and COP scores. The use of quantitative methodologies in this study allowed us to examine growth in teachers’ expectations over time but also limited our ability to fully delve into teachers’ deeper conceptualizations of different character strengths.

Fourth, the COP rating scale was self-developed by the researchers and had not been extensively validated to ensure that it is a true reflection of participant experiences within the COP. Although we did test the scale for internal reliability, more analysis would be needed to ensure that the measure is valid and reliable within multiple contexts and populations.

Finally, while the research that led to the creation of The Good Project’s lesson plans was based in the United States, the COP included an international group of educators who were situated in very different contexts. The American research team recognizes their positionality means that there may be “blind spots” in the methodology and the interpretation of the results.

Conclusion

While encouraging, the results of this study point to a need for more attention to be devoted to teacher preparation in character education through COPs, which appear to continue to be under-utilized amongst practicing educators. Greater use of community learning in the form of COPs or other similar structures such as PLCs (Vescio et al., 2008) may help to close the gap between scholarship about virtues and character and their implementation in the teacher practice and policy within education (Walker et al., 2015). Through collective learning environments focused on pedagogical practice and student development, it may be possible that character can not only be “caught,” “taught,” and “sought” (Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, 2017) for students but for educators as well. Additionally, further research is needed to clarify the potential that educator self-efficacy developed within a COP context will have a demonstrable effect on student experiences or outcomes. The authors of this paper will be investigating this question in future publications. Future qualitative and quantitative research studies may confirm the hypothesis that COPs have a causal influence on educator member’s self-efficacy concerning their ability to impact the character development of their students.

Data availability statement

The raw anonymized and quantitative data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Harvard University Committee on the Use of Human Subjects. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Project administration, Writing – review & editing. HG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was generously supported by a grant from The John Templeton Foundation’s Character through Community initiative. The authors are grateful for their support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1466295/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Throughout this paper, the term “virtues” is used when drawing upon scholarship from the Aristotelian tradition, while “character strengths” is used when drawing upon the psychological tradition. In general, the wider umbrella of both virtues and character strengths is simply referred to as “strengths” in this paper.

2. ^Note that some of the literature drawn on throughout this paper includes references to PLCs rather than COPs, in cases in which the PLC functions similarly to a COP.

3. ^For more information about The Good Project’s resources, see thegoodproject.org.

4. ^In addition to the bulleted list, teachers were also responsible for: submitting post-lesson mini-surveys and collecting post-lesson mini-surveys from their students; recording one class period in which the lessons were taught; and sharing student work generated during the lessons.

5. ^Note that this number is higher than the amount of teachers counted as “official” members of the COP (n = 64) due to drop-outs that occurred along the way, with n = 75 representing the total number of participants who had at least one survey represented in the data at the pre-, mid-, and/or post-survey.

References

Allman, K. R., Maranges, H. M., Whiting, E., Park, R., and Lamb, M. (2024). Exploring character in community: faculty development in university-level communities of practice. J. Coll. Charact. 25, 221–238. doi: 10.1080/2194587X.2024.2348993

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy in Encyclopedia of human behavior (vol. 4). ed. V. S. Ramachaudran, New York: Academic Press. 71–81.

Bateman, D. (2015). Ethical dilemmas: teaching futures in schools. Futures 71, 122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2014.10.001

Be Kind People Project. (2024). Character education. Available at: https://thebekindpeopleproject.org/programs/character-education/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Berkowitz, M. W. (2021). PRIMED for character education: Six design principles for school improvement : London, Routledge.

Berkowitz, M. W., Althof, W., and Bier, M. C. (2012). “The practice of pro-social education” in The handbook of prosocial education: Volume 1. eds. P. Brown, M. Corrigan, and A. Higgins-D’Alessandro, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 71–90.

Berkowitz, M. W. (2002). “The science of character education” in Bringing in a new era in character education. ed. W. Damon, Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. 43–63.

Blankenship, S. S., and Ruona, W. E. A. (2007). Professional learning communities: a comparison of models, literature review. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504776.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Brandon, T., and Charlton, J. (2011). The lessons learned from developing an inclusive learning and teaching community of practice. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 15, 165–178. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2010.496214

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Brown, M., Blanchard, T., and McGrath, R. E. (2020). Differences in self-reported character strengths across adolescence. J. Adolesc. 79, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.12.008

CASEL. (2020). CASEL’s SEL Framework. Available at: https://casel.org/casel-sel-framework-11-2020/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Character Counts! (2024a). Professional development workshops. Available at: https://charactercounts.org/workshops/(Accessed June 1, 2024).

Character Counts! (2024b). The six pillars of character. Available at: https://charactercounts.org/six-pillars-of-character/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Character.org. (n.d.). 11 principles. Available at: https://character.org/11-principles-overview/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Character Strong. (n.d.). Professional learning. Available at: https://characterstrong.com/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dabdoub, J. P., Salgado, D., Bernal, A., Berkowitz, M. W., and Salaverría, A. R. (2023). Redesigning schools for effective character education through leadership: the case of PRIMED institute and vLACE. J. Moral Educ. 53, 558–574. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2023.2254510

Damon, W. (Ed.) (2002). Bringing in a new era in character education. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University.

de Boer, H., Timmermans, A. C., and van der Werf, M. P. C. (2018). The effects of teacher expectation interventions on teachers’ expectations and student achievement: narrative review and meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Eval. 24, 180–200. doi: 10.1080/13803611.2018.1550834

Ekici, D. I. (2018). Development of pre-service teachers’ teaching self-efficacy beliefs through an online community of practice. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 19, 27–40. doi: 10.1007/s12564-017-9511-8

Flanagan, L. (2019). What students gain from learning ethics in school. KQED. Available at: https://www.kqed.org/mindshift/53701/what-students-gain-from-learning-ethics-in-school (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Frey, J. (2022). Jubilee for character education. Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Available at: https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/jubilee-character-education (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Gardner, H. (ed.). (2010). Good work: Theory and Practice. Available at: https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/GoodWork-Theory_and_Practice-with_covers.pdf

Gardner, H. E., Csikszentmihalyi, M., and Damon, W. (2002). Good work: When excellence and ethics meet. London: Basic Books.

Greater Good in Education. (2024). The basics of character education mini-course. Available at: https://ggie.berkeley.edu/course/the-basics-of-character-education-mini-course/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Greater Good Science Center. (2024). The basics of character education for educators: course outcomes. Available at: https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/what_we_do/event/the_basics_of_character_education#tab-outcomes (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Herbers, M. S., Antelo, A., Ettling, D., and Buck, M. A. (2011). Improving teaching through a Community of Practice. J. Transform. Educ. 9, 89–108. doi: 10.1177/1541344611430688

Hussain, M. S., and Khan, S. A. (2022). Self-efficacy of teachers: A review of the literature. Jamshedpur Rev. Res. 50, 110–116.

International Baccalaureate Organization. (2015). The IB continuum of international education. Available at: https://www.ibo.org/globalassets/new-structure/brochures-and-infographics/pdfs/ib-continuum-brochure-en.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Jacobs, N., and Harvey, D. (2010). The extent to which teacher attitudes and expectations predict academic achievement of final year students. Educ. Stud. 36, 195–206. doi: 10.1080/03055690903162374

Jerrim, J., Sims, S., and Oliver, M. (2023). Teacher self-efficacy and pupil achievement: much ado about nothing? International evidence from TIMSS. Teach. Teach. 29, 220–240. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2022.2159365

Jimenez-Silva, M., and Olson, K. (2012). A community of practice in teacher education: insights and perceptions. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 24, 335–348.

Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues (2017). A framework for character education in schools. Available at: https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/The-Jubilee-Centre-Framework-for-Character-Education-in-Schools.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues, University of Birmingham. (2022). The Jubilee Centre framework for character education in schools (third edition). Available at: https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Framework-for-Character-Education-2.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Kelley, T. R., Knowes, J. G., Holland, J. D., and Han, J. (2020). Increasing high school teachers self-efficacy for integrated STEM instruction through a collaborative community of practice. Int. J. STEM Educ. 7, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40594-020-00211-w

Khalid, F., Joyes, G., Ellison, L., and Daud, M. D. (2014). Factors influencing teachers’ level of participation in online communities. Int. Educ. Stud. 7, 23–32. doi: 10.5539/ies.v7n13p23

Kim, K. R., and Seo, E. H. (2018). The relationship between teacher efficacy and students’ academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 46, 529–540. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6554

Kim, R. (2023). Under the law: a case for social and emotional learning. Phi Delta Kappan 105, 62–63. doi: 10.1177/00317217231212016

Kim, Y. A., Kim, J., and Jo, Y.-J. (2023). Teacher efficacy and expectations of minority children: the mediating role of teachers’ beliefs about minority parents’ efficacy. Int. J. Educ. Res. 120:102190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102190

Klassen, R. M., and Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Kraut, R. (2022). “Aristotle’s ethics” in The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. eds. E. N. Zalta and U. Nodelman. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/aristotle-ethics/

Künsting, J., Neuber, V., and Lipowsky, F. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy as a long-term predictor of instructional quality in the classroom. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 31, 299–322. doi: 10.1007/s10212-015-0272-7

Lapsley, D., and Woodbury, R. (2016). Moral-character development for teacher education. Action Teach. Educ. 38, 194–206. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2016.1194785

Lauermann, F., and ten Hagen, I. (2021). Do teachers’ perceived teaching competence and self-efficacy affect students’ academic outcomes? A closer look at student-reported classroom processes and outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 56, 265–282. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2021.1991355

Ledford, A. T. (2011). Professional development for character education: an evaluation of teachers’ sense of efficacy for character education. Scholar Pract. Q. 5, 256–273.

Li, L. C., Grimshaw, J. M., Nielsen, C., Judd, M., Coyte, P. C., and Graham, I. D. (2009). Evolution of Wenger’s concept of community of practice. Implement. Sci. 4, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-11

Lomos, C., Hofman, R. H., and Bosker, R. J. (2011). Professional communities and student achievement – a meta-analysis. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 22, 121–148. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2010.550467

Mak, B., and Pun, S. H. (2015). Cultivating a teacher community of practice for sustainable professional development: beyond planned efforts. Teach. Teach. 21, 4–21. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.928120

McGrath, R. E. (2014). Scale- and item-level factor analyses of the VIA inventory of strengths. Assessment 21, 4–14. doi: 10.1177/1073191112450612

McGrath, R. E. (2018). What is character education? Development of a prototype. J. Charact. Educ. 14, 23–35.

McGrath, R., and Walker, D. I. (2016). Factor structure of character strengths in youth: consistency across ages and measures. J. Moral Educ. 45, 400–418. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2016.1213709

Mojavezi, A., and Tamiz, M. P. (2012). The impact of teacher self-efficacy on the students’ motivation and achievement. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2, 483–491. doi: 10.4304/tpls.2.3.483-491

Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., and Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the sources of teaching self-efficacy: A critical review of emerging literature. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 29, 795–833.

National Association of State Boards of Education. (2024). Social-emotional learning or character development. State Policy Database. Available at: https://statepolicies.nasbe.org/health/categories/social-emotional-climate/social-emotional-learning-or-character-development (Accessed June 1, 2024).

OECD. (2019). OECD future of education and skills 2030 concept note. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/projects/edu/education-2040/concept-notes/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_concept_note.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Park, N., and Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among adolescents: the development and validation of the values in action inventory of strengths for youth. J. Adolesc. 29, 891–909. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.011

Peterson, A., and Civil, D. (2022). Schools, civic virtues and the good citizen: Research report. University of Birmingham, Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtues. Available at: https://www.jubileecentre.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/SchoolsCivicVirtueandtheGoodCitizen_ResearchReport_Accessible.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC, USA. American Psychological Association/New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press.

Polizzi, S. J., Zhu, Y., Reid, J. W., Ofem, B., Salisbury, S., Beeth, M., et al. (2021). Science and mathematics teacher communities of practice: social influences on discipline-based identify and self-efficacy beliefs. Int. J. STEM Educ. 8, 1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40594-021-00275-2

Power, F. C., Higgins, A., and Kohlberg, L. (1989). Lawrence Kohlberg’s approach to moral education. New York, NY, USA : Columbia University Press.

Robson, K., and Prevalin, D. (2016). Multilevel modeling in plain language. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Limited.

Rodriguez, C. M. (2014). The relationship between teacher expectations and teacher self-efficacy as it pertains to student success. The Claremont Graduate University.

Rosenthal, R., and Jacobson, L. (1992). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils\u0027 intellectual development. Irvington Publishers.

Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2010). Teacher expectations and perceptions of student attributes: is there a relationship? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 121–135. doi: 10.1348/000709909X466334

Rubie-Davies, C. M., Flint, A., and McDonald, L. G. (2011). Teacher beliefs, teacher characteristics, and school contextual factors: what are the relationships? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 270–288. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02025.x

Ruch, W., Martínez-Martí, M. L., Proyer, R. T., and Harzer, C. (2014). The character strengths rating form (CSRF): development and initial assessment of a 24-item rating scale to assess character strengths. Personal. Individ. Differ. 68, 53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.042

Shahzad, K., and Naureen, S. (2017). Impact of teacher self-efficacy on secondary school students’ academic achievement. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 4, 48–72. doi: 10.22555/joeed.v4i1.1050

Smith, B. H. (2013). School-based character education in the United States. Child. Educ. 89, 350–355. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2013.850921

Smith, C., and Becker, S. (2021). Using communities of practice to facilitate technology integration among K-12 educators: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 29, 559–583.

Snijders, T. A., and Bosker, R. (2011). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Summers, J. J., Davis, H. A., and Hoy, A. W. (2017). The effects of teachers\u0027 efficacy beliefs on students\u0027 perceptions of teacher relationship quality. Learn. Individ. Differ. 53, 17–25.

Tai, D. W. S., Hu, Y.-C., Wang, R., and Chen, J.-L. (2012). What is the impact of teacher self-efficacy on the student learning outcome? 3rd WIETE Annual Conference on Engineering and Technology Education.

Tam, A. C. F. (2015). The role of a professional learning community in teacher change: a perspective from beliefs and practices. Teach. Teach. 21, 22–43. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.928122

The Good Project. (2024a). Lesson plans: Introduction. Available at: https://www.thegoodproject.org/lessonintro

The Good Project. (2024b). Theory of change. Available at: https://www.thegoodproject.org/theory-of-change

Tichnor-Wagner, A. (2022). Accelerating character education learning through a networked approach: insights from the Kern Partners for character and educational leadership. J. Educ. 202, 198–207. doi: 10.1177/00220574211026902

Trust, T., and Horrocks, B. (2019). Six key elements identified in an active and thriving blended Community of Practice. TechTrends 63, 108–115. doi: 10.1007/s11528-018-0265-x

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive concept. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805.

Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk Hoy, A., and Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 68, 202–248.

UNESCO. (2015). Incheon declaration and framework for action for the implementation of sustainable development goal 4. Available at: https://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/education-2030-incheon-framework-for-action-implementation-of-sdg4-2016-en_2.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

United Nations. (2023). Report on the 2022 transitioning education summit. Available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/report_on_the_2022_transforming_education_summit.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024).

University of San Diego. (2024). Character education development certificate. Available at: https://pce.sandiego.edu/certificates/character-education-development-certificate/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

U.S. Department of Education. (2005). Character education…our shared responsibility. Available at: https://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/character/brochure.html (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Vescio, V., Ross, D., and Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 24, 80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004

VIA Institute on Character. (2024a). The 24 character strengths. Available at: https://www.viacharacter.org/character-strengths (Accessed June 1, 2024).