- Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, New York, NY, United States

The rising prevalence of internet pornography consumption among adolescents has created a need for proactive approaches to pornography literacy within sex education. This article aims to both introduce the “Navigating Realities” curriculum and advocate for an expanded approach to pornography literacy education that integrates comprehensive media literacy, critical analysis, and a sex-positive framework. This evidence-informed curriculum was developed based on a literature review on adolescent pornography consumption, its impact on sexual attitudes and behaviors, and documented gaps in existing sex education programs. Methodologically, the curriculum is grounded in backward design, the cultivation theory of mass media, and the triangle of sexual health, rights, and pleasure. Guided by these frameworks, Navigating Realities pursues three overarching aims: (1) promote critical thinking and media literacy, (2) foster healthy relationships, and (3) encourage responsible digital behavior. These aims guide the pedagogical approach, which incorporates a combination of knowledge-based activities, social norms exploration, and skill-building exercises. The curriculum emphasizes the distinction between fantasy and reality in sexual content, body image, consent, and the portrayal of violence, while reinforcing healthy relationship skills and safe digital practices. As a result, “Navigating Realities” serves as a proposed evidence-informed educational framework, tailored to high school students aged 15–18, that supports them in critiquing explicit content. Future applications will include pilot testing and broader implementation, underscoring the need for ongoing research and funding to ensure the effectiveness of comprehensive sex education initiatives.

1 Introduction

With the expansion of the internet, pornography has become easier to access than ever before (Cerniglia and Cimino, 2024; Zoie and Rashid, 2021). Adolescents’ digital media consumption patterns continue to evolve, with increased use of social media platforms and streaming services influencing their perceptions of sex and relationships (Paulus et al., 2024; Cipolletta et al., 2020; Robb and Mann, 2022; Rege, 2022; Vandenbosch and Eggermont, 2015; Rousseau et al., 2017). Although comprehensive prevalence data is limited, available studies indicate that adolescent exposure to pornography is common, with reported figures varying by geography and study design (Robb and Mann, 2022; Cerniglia and Cimino, 2024; Rege, 2022; Gola et al., 2017; Hald, 2006). This exposure often occurs unintentionally or before adolescents have received formal education on safe sexual practices, consent, intimacy, or healthy relationships, leaving them ill-equipped to contextualize the explicit content they encounter (Adarsh and Sahoo, 2023). Moreover, studies suggest that pornography is becoming an increasingly dominant source of sex education, often shaping young people’s attitudes toward sex and relationships (Paulus et al., 2024; Wahl, 2023).

This article introduces the Navigating Realities curriculum and advocates for a comprehensive approach to pornography literacy that integrates media literacy, critical thinking, and a sex-positive framework. The curriculum is evidence-informed and was developed through a review of research on adolescent pornography consumption, its effects on sexual attitudes and behaviors, and persistent gaps in current sex education programs. To support effective implementation and transparency, Navigating Realities includes supplemental materials including full lesson plans, step-by-step activity instructions, facilitator guidance, sample assessments, and monitoring tools. These resources are designed to help educators deliver the curriculum effectively and support evaluation across diverse educational settings.

Rather than isolating pornography as a standalone topic, Navigating Realities situates pornography literacy within a broader framework of media literacy and sexual health. The curriculum acknowledges that pornography influences a range of beliefs and behaviors related to sex, intimacy, and risk-taking. Therefore, alongside lessons on fantasy versus reality, body image, and consent, the curriculum includes practical content on topics such as condom use and STI prevention. These topics are not peripheral, they are essential examples of how pornography often misrepresents safe sex, and how students can learn to challenge and correct those misrepresentations. By bridging critical thinking with practical knowledge, the curriculum prepares students to apply media literacy in ways that directly support their sexual well-being. This integrated approach aims to help students make informed decisions and contextualize sexually explicit media within the broader landscape of real-life sexual health. It ensures that critical media literacy is reinforced through actionable sexual health skills and grounded in a rights-based, sex-positive framework.

Pornography typically fails to depict essential elements of healthy sexual relationships, such as condom use, verbal consent, discussions about boundaries, and STI prevention (Hu et al., 2024). Instead, it often reinforces harmful stereotypes, exaggerated body standards, and depictions of erotic violence (Irizarry et al., 2023; Gola et al., 2017). While some research highlights potential benefits, such as increased sexual awareness, pleasure, and representation of diverse bodies and interests (Jhe et al., 2023), the negative consequences, such as decreased self-esteem and increased aggression, necessitate a critical educational response.

The literature review conducted in preparation for this curriculum identified several critical areas where existing sex education programs fall short in addressing the realities of adolescent pornography exposure:

Digital Media Consumption Patterns: Adolescents are increasingly consuming explicit content across diverse digital contexts. This necessitates adaptable educational approaches that address the role of social media, streaming platforms, and peer-shared media in shaping perceptions of sex and relationships (Paulus et al., 2024; Wahl, 2023; Rege, 2022; Cerniglia and Cimino, 2024; Robb and Mann, 2022; Maas et al., 2022; Cipolletta et al., 2020).

Impact on Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors: Exposure to pornography has been linked to the formation of unrealistic expectations about sex, body image, and relationships. Research highlights both potential negative outcomes, such as decreased sexual satisfaction and increased aggression, and positive aspects, such as enhanced sexual awareness, pleasure, and education (Jhe et al., 2023; Litsou et al., 2021; Robb and Mann, 2022; Rodenhizer and Edwards, 2019; Peter and Valkenburg, 2016; Hu et al., 2024; Healy-Cullen and Morrison, 2023).

Effective Educational Strategies: Evidence suggests that sex education programs that incorporate media literacy, critical thinking, and discussions on consent and healthy relationships may be helpful in mitigating negative impacts and promoting responsible media consumption (Evans-Paulson et al., 2024; Paulus et al., 2024; Maas et al., 2022; Mark et al., 2021; Crabbe and Flood, 2021; Healy-Cullen et al., 2022). Research by Wright and Herbenick (2024) and Robb and Mann (2022) highlights the additional value of parental communication in reducing risks (Atif et al., 2022) associated with pornography exposure, such as condomless sex, underscoring the importance of involving parents as active partners in sexual education which will be addressed later in implementation protocols.

Developmental Considerations: From a developmental perspective, adolescence is characterized by heightened neuroplasticity, evolving impulse control, and a growing sensitivity to social rewards (Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications, 2019; Steinberg, 2010). During this period, teens engage in increased exploration of personal identity and experiment with new social norms. However, teens’ still-maturing cognitive-function can leave them more vulnerable to external influences, such as media portrayals of sexual norms, than adults (Somerville, 2013). By providing a structured framework for critical thinking and media literacy, this curriculum aims to equip adolescents with the skills to navigate these unique developmental vulnerabilities, fostering safer and more informed sexual decision-making.

Together, these findings underscore the need for a curriculum like Navigating Realities, one that addresses the consumption of pornography through the lens of media literacy, promotes healthy relationships, and equips adolescents with the tools to critically analyze and respond to the media they consume.

2 Program overview

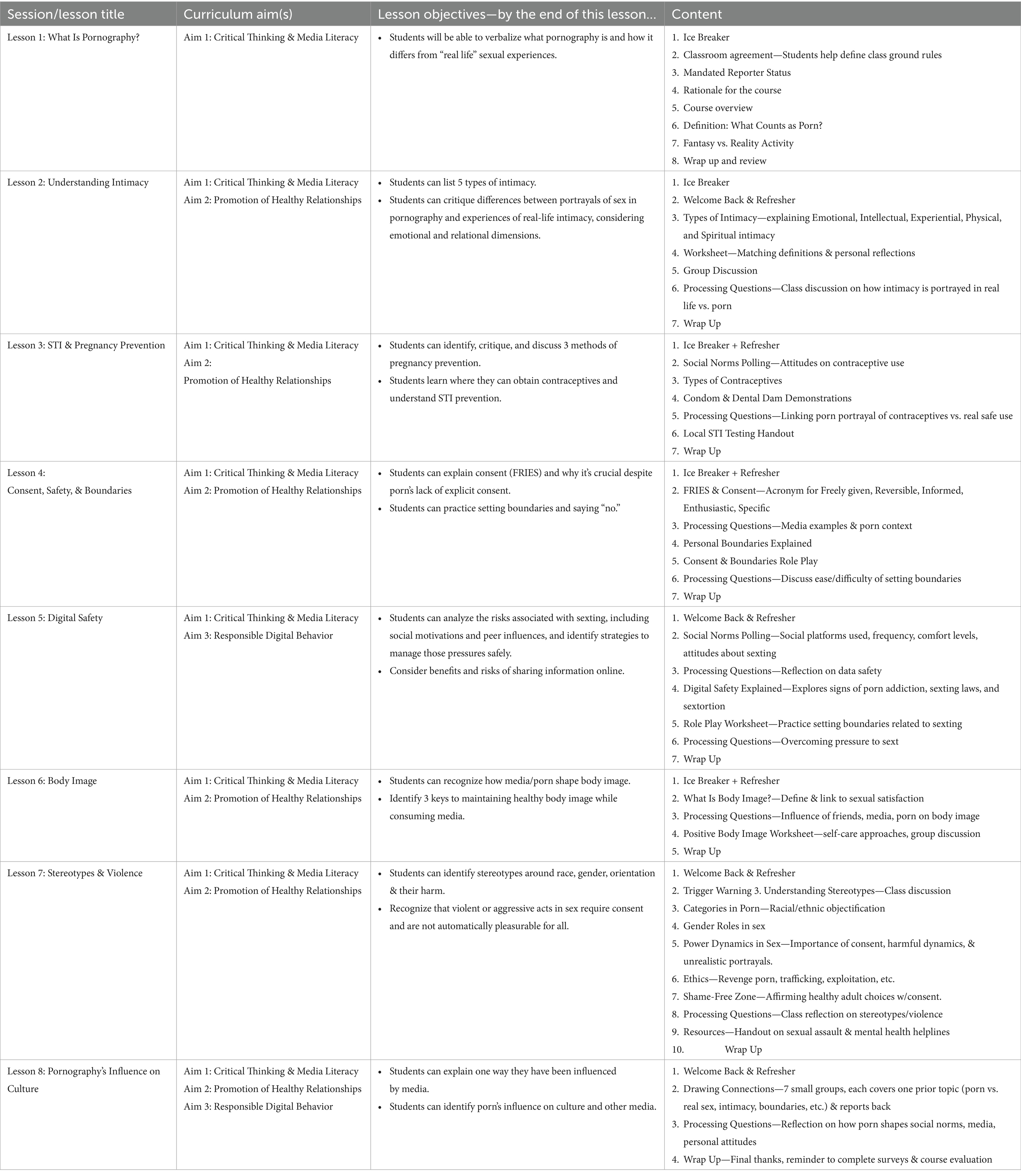

This proposed curriculum is designed to provide critical thinking, media literacy, and contextual analysis skills to support young people in developing healthy sexual practices and understanding their own sexual identities amidst mainstream porn scripts (Biota et al., 2022). The Navigating Realities curriculum is structured around a three-tiered framework for educational design. At the highest level, the curriculum is guided by three overarching program aims: promoting critical thinking and media literacy, fostering healthy relationships, and encouraging responsible digital behavior. These aims reflect the core values and thematic priorities of the curriculum. Each aim is supported by a set of curriculum-level learning objectives, which describe the measurable competencies students are expected to develop over the duration of the program. These course objectives are intended to support student learning across all sessions. Finally, each individual lesson includes its own lesson-level objectives (see Table 1), which are tailored to specific activities and content areas, and collectively map back to the broader course objectives. This three-tiered structure ensures alignment across aims, outcomes, and instructional design, following a backward design approach that builds from intended outcomes to specific teaching strategies and assessments.

The curriculum objectives for each aim are as follows:

Aim 1: Encourage Critical Thinking and Media Literacy

• Curriculum Objectives:

• Evaluate virtual representations of sex in the media by understanding distinctions between fantasy and reality.

• Critically assess the influence of sexual content on their attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions of sex and gender roles.

• Make informed and responsible choices for their sexual wellbeing.

Aim 2: Foster Healthy Relationships

• Curriculum Objectives:

• Proactively foster healthy sexual relationships by utilizing a new understanding of body image, consent, boundaries, violence, and diverse forms of intimacy.

Aim 3: Promote Responsible Digital Behavior

• Curriculum Objectives:

• Knowledgeably navigate legal and social responsibilities associated with digital use, specifically regarding sexting, and seek to consume content that contributes to their sexual health rather than harmful behaviors.

To ensure that each level of the curriculum—aims, course objectives, and lesson objectives—are meaningfully aligned, Navigating Realities is grounded in several established pedagogical and behavioral theories.

This curriculum draws on three complementary frameworks to ensure that every lesson advances its core aims. The pedagogical notion of backward design (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005) starts by identifying the knowledge and skills students should master, then works backward to select instructional methods and assessments that deliver those outcomes. Cultivation theory (Gerbner et al., 2002) explains how repeated exposure to media—especially pornography—shapes beliefs about what is “normal,” underscoring the need for critical media literacy. Finally, sexual-health, rights, and pleasure frameworks (Gruskin et al., 2019) provide a holistic foundation that values well-being, autonomy, and positive sexual experiences. Together, these theories guide the curriculum in helping adolescents distinguish fantasy from reality, critique harmful media messages, and make informed, health-promoting choices in person and in digital spaces. These concepts will be further elaborated in the Theoretical Foundations section of this paper.

This curriculum is currently in the proposal stage and marks an innovative approach to pornography literacy in high school education. While the curriculum’s design is based on sound theoretical foundations and available research, its real-world applicability will be further refined through pilot testing in diverse educational settings. Implementation may face challenges such as teacher discomfort, limited parental or community support, and varying school readiness. Still, given adolescents’ growing exposure to sexualized media, advancing adaptable and evidence-informed education remains essential. Recognizing these barriers enables better planning and engagement, ultimately supporting more effective delivery. Feedback from students, educators, and experts is intended to guide future revisions and ensure the curriculum meets its objectives of fostering critical thinking and healthy sexual practices among adolescents.

While a handful of other pornography literacy programs exist, “Navigating Realities” advances the field by integrating the strengths of previous efforts into a single, cohesive curriculum grounded in a sexual-health approach to media literacy. For example, Boston University Professor Emily Rothman’s curriculum “The Truth About Pornography: A Pornography-Literacy Curriculum for High School Students Designed to Reduce Sexual and Dating Violence” incorporates media literacy through the lens of healthy dating relationships, emphasizing social and psychological impacts of pornography and related sexual norms (Rothman et al., 2020). Delivered through the Start Strong initiative, it includes sessions on media law, gender double standards, and healthy relationships, and has demonstrated measurable effects in reducing students’ reliance on pornography as a source of sexual information.

Other programs include “Reality & Risk,” available in Australia since 2009, and the “Healthy Sexuality” initiative in Ireland, both of which provide community-based education on pornography and healthy sexual behavior. Additionally, curricula such as “Your Voice Your View and Our Whole Lives” (OWL), although less focused on pornography specifically, incorporate discussions of sexual media in broader sex ed. frameworks. Davis et al. (2020) also developed “The Gist,” a digital tool designed to enhance pornography literacy among vulnerable youth in Australia (Pappas, 2021).

Building on these contributions, “Navigating Realities” situates pornography literacy within the broader context of digital media consumption, encouraging students to critically assess how various forms of media, including pornography, influence attitudes toward sex, relationships, body image, and self-concept. This holistic and integrative approach enables students to apply critical thinking across diverse media contexts and supports the development of healthy, informed sexual decision-making.

Importantly, “Navigating Realities” is a freely available resource, intended not to replace existing programs but to consolidate effective practices, facilitate educator access, and spark continued innovation in the field. It brings together pedagogical frameworks, evidence-based strategies, and classroom-ready tools in an adaptable, inclusive format. By sharing this curriculum openly, the authors aim to support global dialog and inspire further development in pornography literacy education.

In summary, this paper introduces “Navigating Realities” as a practical and forward-looking curriculum that extends current pornography literacy efforts by uniting them within a comprehensive media literacy and sex-positive framework.

3 Pedagogical framework(s), principles, and application

“Navigating Realities” draws on three main theories, each guiding both the overall curriculum structure and lesson design: Theory of Backward Design, Cultivation Theory of Mass Media, and the Triangle of Sexual Health, Rights, and Pleasure.

3.1 Theory of backward design

The Theory of Backward Design is a curriculum development approach that begins with defining desired learning outcomes and then designing instructional methods to achieve those outcomes (Wiggins and McTighe, 2005). While primarily recognized as a course design process, backward design serves as a foundational framework ensuring that all lessons are aligned with the overarching goals of the curriculum. For example, the overarching aim of encouraging critical thinking and media literacy is supported by curriculum-level objectives such as evaluating virtual representations of sex and distinguishing between fantasy and reality. These competencies are illustrated in Lesson 1, “What is Pornography?,” where students are asked to identify how pornography differs from real-life sexual experiences and reflect on how media shapes their expectations. This lesson-level objective helps students build foundational media literacy while reinforcing the broader aim of critical analysis.

3.2 Cultivation theory of mass media

Cultivation theory posits that repeated exposure to certain media depictions gradually “normalizes” those portrayals and attitudes (Gerbner et al., 2002; Schiavo, 2014). In this curriculum, we encourage students to critically analyze how pornography can influence beliefs about sex, bodies, and relationships over time. Lessons incorporate media-literacy discussions and role-play scenarios prompting students to question whether the norms they see on screen (e.g., minimal use of condoms, exaggerated power dynamics) align with realistic, healthy relationships. For example, in Lesson 1, the “Planet Porn vs. Planet Earth” activity directly confronts the ways pornography might cultivate skewed expectations, challenging students to differentiate between fantasy and reality.

3.3 Triangle of sexual health, rights, and pleasure

The Triangle of Sexual Health, Rights, and Pleasure is a comprehensive framework that ensures sexual education is balanced, empowering, and stigma-free (Gruskin et al., 2019). This triangle emphasizes that sexual health encompasses not only the absence of disease but also the presence of well-being, autonomy, and the pursuit of pleasure. By integrating sexual rights, the curriculum advocates for individuals’ rights to consensual and respectful sexual interactions. The inclusion of pleasure underscores the importance of positive sexual experiences in fostering healthy attitudes and behaviors (Mark et al., 2021). Research indicates that sexual health behaviors are more effectively adopted when they are presented as pleasurable and stigma-free (Be Positive—The Pleasure Project, 2022). In this curriculum, the triangle framework guides the presentation of topics such as consent, body autonomy, and the dismantling of harmful stereotypes. Thus, the curriculum frames topics like masturbation, bodily autonomy, and consent in positive, affirming ways. For example, in Lesson 1, while discussing what pornography is, the lesson affirms self-exploration as a healthy part of sexual development, so long as it is guided by respect, consent, and an understanding of realistic expectations.

Together, these three theoretical frameworks work synergistically to support the curriculum’s core objectives. Backward Design provides a structural roadmap to ensure alignment between learning goals and classroom activities. Cultivation Theory informs the development of media literacy skills by helping students understand how repeated media exposure can shape attitudes and expectations. The Triangle of Sexual Health, Rights, and Pleasure ensures that all content is presented in a sex-positive, empowering, and rights-based manner. Their integration allows students to engage critically with media, reflect on personal values and societal norms, and develop healthy sexual attitudes and behaviors in a cohesive and supportive learning environment.

3.4 Structuring the eight sessions and topic selection

Grounded in foundational health education models, including the Health Belief Model (HBM) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the curriculum is structured into eight 60-min sessions (see Table 1). These sessions target both proximal determinants (e.g., knowledge and skills) and distal determinants (e.g., attitudes, social norms, and self-concept). For instance, HBM concepts like cue to action are incorporated to help students move from knowledge acquisition to actionable behaviors, such as ensuring condom accessibility near the bed (Glanz et al., 2008; Rosenstock et al., 1988). Similarly, TPB constructs such as self-efficacy and perceived behavioral control are embedded to encourage confidence and intention in applying learned behaviors in real-life scenarios (Ajzen, 1991).

This theoretical lens also informs the selection of topics, ensuring content is both age-appropriate and aligned with developmental and time constraints. Many niche topics such as BDSM, fetishes, or animated pornography are not addressed or only mentioned briefly, focusing on consent and respect rather than delving into detailed discussions, ensuring relevance and appropriateness for 9th-grade students. Each lesson provides a foundational understanding of pornography literacy, emphasizing critical media analysis and healthy sexual practices. For detailed instructions on the practical implementation of each session, including step-by-step activity breakdowns, refer to the supplemental materials accompanying this manuscript.

3.5 Operationalizing the framework

The proposed curriculum’s theoretical foundation drives its dual focus on proximal and distal targets:

• Proximal Targets: Factual knowledge (e.g., STI prevention) and skill-building (e.g., condom demonstrations, boundary-setting role plays).

• Distal Targets: Attitudes (e.g., dismantling harmful stereotypes), social norms (e.g., fostering open communication and consent), and self-concept (e.g., promoting body positivity and confidence).

To operationalize these goals:

• HBM concepts such as perceived susceptibility and cue to action are applied to highlight risks associated with uninformed sexual behaviors and to encourage practical preparation, like condom accessibility (Glanz et al., 2008; Rosenstock et al., 1988).

• TPB elements, including subjective norms and behavioral intentions, are integrated into activities like role-plays and group discussions to address peer influences and reinforce positive behavior change (Ajzen, 1991).

Lessons utilize interactive and evidence-informed strategies, including sorting exercises, worksheets, anonymous live polling, and experiential learning discussions. These activities foster engagement and help students internalize both knowledge and behaviors. Sample lesson plans, provided in the supplemental materials, chart each class in 10–20-min increments to facilitate easy pickup and implementation by educators. Sessions are intended to be delivered in person by a trained facilitator in sexuality education for a class size of ideally 15, but up to 25, with minimal technological requirements, such as a whiteboard or projector. When devices for polling are unavailable, traditional methods like paper-based surveys or color-coded cards ensure accessibility and inclusivity.

3.6 Holistic and inclusive approach

This proposed curriculum prioritizes a consistent, coherent educational experience. HBM and TPB principles guide the curriculum design, ensuring alignment with established health education frameworks. By addressing critical determinants of behavior, the curriculum encourages deep critical thinking and informed sexual health practices.

A central theme throughout is affirming individual identity, needs, boundaries, and sexuality without shame. Lessons encourage introspection, challenge dominant media narratives, and connect to overarching goals like critical media literacy, healthy relationships, and safe digital behavior. Role-play scenarios with gender-neutral names and activities that confront stereotypes (Balén et al., 2024) create a safe, inclusive, and sex-positive learning environment.

For pilot testing, feedback will be sought from a diverse group of students to ensure cultural and contextual relevance, further strengthening the curriculum’s inclusivity and applicability.

4 Learning environment (setting, students, faculty); learning objectives; pedagogical format

4.1 Setting

The proposed curriculum is designed for 9th-grade students but can be adapted for high school students aged 15–18. We anticipate that this program might initially be picked up progressive educational settings (e.g., Montessori, Quaker, or charter schools), recognizing their greater flexibility in policies related to comprehensive sex education. We cite this as a limitation of this topic area. However, we have also structured the curriculum to facilitate broader applicability across diverse educational environments, including public or government schools. For instance, government schools may face stricter regulatory constraints and limited resources that could hinder initial implementation. To overcome these types of barriers, we have tried to put forth a design that is easy to modify, ensuring that it remains relevant and accessible regardless of administrative restrictions or resource limitations (see below for example adaptations). Activities involving digital tools, such as online polling, can be adapted to traditional methods like whiteboard discussions or paper-based exercises, ensuring curriculum accessibility irrespective of technology availability.

4.1.1 Resource adaptations

• In schools with limited technology or budgets, activities involving online polling can be replaced by whiteboard discussions, paper-based surveys, or color-coded cards to gage student opinions and encourage participation.

• For more conservative communities, discussions can focus on general media-literacy principles and healthy relationship skills, with references to pornography kept as conceptual (e.g., “media depicting sexual content”) rather than detailed descriptions. For example, in Lesson 1’s “Planet Earth vs. Planet Porn” activity, facilitators can modify examples to better align with their community’s norms and rename the activity to focus on “sexualized media and movies,” ensuring the curriculum remains accessible and appropriate for diverse educational settings.

• Where strict parental consent protocols are required, educators may begin with topics like digital safety, boundaries, and media stereotypes before delving into sensitive issues to build trust and demonstrate the curriculum’s educational value.

4.1.2 Core objectives in all contexts

Regardless of the school’s particular constraints or level of openness to discussing pornography, the curriculum’s main goals, critical thinking, media literacy, and healthy sexual practices, remain broadly relevant. Because each lesson is theoretically grounded yet easily customizable, educators can adjust discussions and contextual examples to suit local cultural expectations while still achieving the intended learning outcomes.

4.1.3 Cultural adaptation and fidelity

To maintain effectiveness when adapting the curriculum for diverse cultural contexts, each lesson’s core objectives—critical thinking, media literacy, and responsible sexual health—must remain intact. Specific examples, language, and classroom activities should be modified to reflect local norms, but educators are encouraged to preserve the underlying pedagogical principles (e.g., maintaining a non-judgmental learning environment and emphasizing student-centered discussions) that uphold the curriculum’s effectiveness.

Specific adaptation strategies include:

• Language and Terminology: Adjust terminology related to sexuality and relationships to align with local comfort levels and social norms, replacing explicit terms with more neutral or conceptual language (e.g., using “intimacy,” “relationships,” or “personal boundaries”).

• Culturally Relevant Examples and Scenarios: Use scenarios reflecting local relationship dynamics, such as arranged marriages, dating expectations, and familial roles. Select media examples from popular local films, TV shows, or advertisements to illustrate points about media literacy and relationships.

• Consent and Boundaries: Adapt consent activities to match local customs or traditions around personal space and social interactions, emphasizing universal themes like mutual respect, bodily autonomy, and clear communication rather than context-specific dating norms.

• Visual and Teaching Materials: Choose visuals and materials representative of the cultural diversity within the classroom, avoiding content that could reinforce stereotypes or cause unintended offense.

• Local Values and Social Norms: Articulate the curriculum’s alignment with local community values such as respect, family cohesion, and personal responsibility. In settings where dominant religious or moral values shape views on sexuality, educators can frame lessons using universally accepted principles such as safety, consent, and human dignity. Rather than directly conflicting with local beliefs, this approach fosters inclusion by emphasizing shared values. It helps avoid tokenism by promoting genuine engagement and cultural relevance, while still upholding the curriculum’s core objectives.

4.2 Students

This curriculum is primarily designed for 9th-grade students but could be adapted for high school students aged 15–18. Adolescents in this age range are at a pivotal developmental stage where introducing media literacy and critical thinking becomes essential (Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications, 2019). However, we recognize that research, including the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (UNESCO, 2018), suggests that younger adolescents (e.g., 6 or 7th graders) may benefit from age-appropriate interventions tailored to their earlier exposure to pornography and other digital media. Future iterations of the curriculum could adapt content to meet the cognitive and emotional maturity of younger age groups while maintaining its foundational goals.

For 9th graders, this curriculum aligns with their developmental transition from concrete to abstract thinking, supporting their ability to analyze complex media messages and explore nuanced topics like consent, body image, and media literacy. At this stage, adolescents are also beginning to form values and beliefs regarding sexual health, often influenced by peer dynamics and social norms (Ford et al., 2017). Peer pressure and societal expectations, particularly around relationships and sexuality, play a significant role in shaping their attitudes and behaviors (Steinberg, 2010; UNESCO, 2018). Their health goals include managing their physical and emotional well-being, yet these external influences can complicate decision-making. The curriculum addresses these dynamics by fostering critical thinking and self-reflection, enabling students to navigate these influences with confidence and informed decision-making.

For younger adolescents, curriculum adaptations would emphasize foundational concepts, such as recognizing healthy relationships and understanding digital boundaries, in line with age-appropriate engagement levels outlined by the UNESCO International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education (UNESCO, 2018). By tailoring content to developmental readiness, the curriculum can effectively build foundational skills earlier while ensuring relevance and accessibility for diverse educational contexts.

This learner-centered approach acknowledges the unique needs, values, and influences of students, providing a holistic framework for sexual education that supports critical media literacy and healthy relationships.

4.3 Faculty

The facilitator, whether internal or external, should have expertise in comprehensive sexuality education and be trained in the curriculum’s content, underlying theoretical frameworks (e.g., backward design, cultivation theory), age-appropriate pedagogy, and strategies for fostering open, respectful discussions on sensitive topics. While an external facilitator may support consistency in delivery, an internal educator with established relationships may foster greater student engagement. Given the mixed findings on facilitator effectiveness, this decision should be made based on available resources, school context, and educator capacity during the implementation stage of this proposed curriculum. If an external facilitator is not feasible, schools are encouraged to reach out to the authors, who are deeply passionate about this topic, have led facilitator trainings in the past, and are willing to offer guidance or support meetings as schools consider implementation.

4.3.1 Implementation protocols

4.3.1.1 Teacher training

As noted in the faculty section above, facilitators should be trained not only in the curriculum’s specific content and lesson plans but also in the theoretical foundations that underpin the program, such as backward design, cultivation theory, and the sexual health–rights–pleasure framework. This ensures facilitators understand not just what to teach, but why and how it supports adolescent learning. In addition, facilitators should understand developmental considerations (e.g., impulse control, identity formation, and neuroplasticity), best practices for fostering inclusive and trauma-informed classrooms, and strategies for navigating emotionally charged discussions (Balén et al., 2024).

Facilitators should be trained to recognize and respond to student disclosures in accordance with school or district policy and to manage classroom discussions in ways that minimize shame and stigma. Competencies include building trust, managing pushback or discomfort, and framing complex media-literacy concepts in age-appropriate language.

Educators will be advised not to take personal stances on controversial issues; instead, they facilitate open, respectful dialog. Absolutely no explicit or sexualized material should be shown in class. All content must be age-appropriate and conceptual, focusing on discussion, role-play, and media literacy (See online supplemental material for more details).

Supplemental materials provide a facilitator guide with lesson-delivery strategies and implementation considerations. These resources reinforce—but do not replace—formal training. Required competencies should be in place before lesson delivery, whether acquired through prior education, up-skilling, external workshops, or consultation with the curriculum developers, who have extensive experience supporting teacher training for similar programs.

By combining pedagogical preparation, theoretical grounding, and classroom readiness, this training protocol supports curriculum fidelity, enhances educator confidence, and promotes positive student engagement.

4.3.1.2 Parent engagement

• Mandatory Consent & Pre-Course Meetings: Prior to initiating the proposed curriculum, an information session should be held so parents and guardians can learn about lesson plan content, ask questions, and provide permission.

• Ongoing Communication: Parents will be notified before lessons involving more sensitive topics (e.g., sexual violence) via email or school portals, ensuring they remain fully informed of the curriculum’s scope.

• Engaging Parents in Polarized Environments: Research indicates that effective strategies for engaging parents in environments with polarized views include transparent communication, informational workshops, and collaborative meetings (Epstein, 2018; Aventin et al., 2020; Best practices for family engagement in sex education implementation, 2025). Transparent communication involves clearly outlining the curriculum’s objectives and benefits, addressing potential concerns proactively. Informational workshops can educate parents about the importance of pornography literacy and its role in promoting sexual health and safety. Collaborative meetings foster a sense of partnership between educators and parents, allowing for mutual understanding and support. Additionally, framing the curriculum around shared values such as student well-being and informed decision-making can help bridge differing perspectives and gain broader acceptance.

4.3.1.3 Risk management and ethical considerations

4.3.1.3.1 Safe and supportive environment

Activities in the proposed curriculum are explicitly designed to be shame-free, sex-positive, and respectful, maintaining students’ comfort and privacy. Facilitators should clearly communicate the boundaries of classroom confidentiality and mandated reporting requirements, emphasizing that teachers are safe adults to confide in privately, but certain disclosures—such as indications of harm to self or others—must be reported according to school policies. Facilitators must remain vigilant about students’ emotional maturity, redirecting or reframing discussions that become overly personal or inappropriate (Cavener and Lonbay, 2022).

4.3.1.3.2 Managing sensitive discussions and private disclosures

Facilitators must follow school or district guidelines regarding mandated reporting if students privately disclose situations of harm, abuse, or trauma (Department of Education, 2024). Resources for ‘Supporting Survivors of Sexual Assault’ are included on page 57 of supplemental materials and can be shared with students. Clear referral pathways to school counselors, mental health services, or external resources should be established before curriculum implementation. Facilitators should periodically remind students about available school counselors and supportive resources, especially when challenging or sensitive topics are discussed. If students approach facilitators privately to disclose personal concerns or distress, facilitators should document these disclosures appropriately and immediately connect the student with the appropriate support services or guardians (Child abuse prevention and treatment act (CAPTA), 2023; Department of Education, 2024).

4.3.1.3.3 Contingency and communication plans

If a student experiences serious emotional distress related to course content, facilitators should promptly contact parents or guardians and share mental health resources for local mental health care providers, support groups, or helplines (988, Trevor Project, RAINN). Students must regularly be reminded that, while the classroom aims to be a safe, nonjudgmental space, certain disclosures made privately to facilitators may require additional action to ensure student safety and wellbeing (Child abuse prevention and treatment act (CAPTA), 2023; Department of Education, 2024).

4.4 Lesson objectives

Each lesson in Navigating Realities is guided by one or more lesson-level objectives, which translate the broader curriculum goals into specific, actionable learning outcomes for students. These objectives are intentionally designed to align with the curriculum-level objectives, and by extension, the overarching aims of the program.

Whereas program aims articulate the curriculum’s high-level goals and curriculum objectives define the broader competencies students are expected to develop over the course, lesson objectives operate at the classroom level. They outline what students should know, do, or reflect upon during or by the end of a particular session. These objectives are used to inform pedagogical choices, structure learning activities, and support ongoing assessment.

Table 1 outlines how each lesson’s objective maps back to one or more of the overarching aims. This alignment ensures a consistent and structured learning progression, reinforcing the backward design model that underpins the curriculum’s development.

For ease of reference, the aims and curriculum objectives are:

Aim 1: Encourage Critical Thinking and Media Literacy

• Curriculum Objectives:

• Evaluate virtual representations of sex in the media by understanding distinctions between fantasy and reality.

• Critically assess the influence of sexual content on their attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions of sex and gender roles.

• Make informed and responsible choices for their sexual wellbeing.

Aim 2: Foster Healthy Relationships

• Curriculum Objectives:

• Proactively foster healthy sexual relationships by utilizing a new understanding of body image, consent, boundaries, violence, and diverse forms of intimacy.

Aim 3: Promote Responsible Digital Behavior

• Curriculum Objectives:

• Knowledgeably navigate legal and social responsibilities associated with digital use, specifically regarding sexting, and seek to consume content that contributes to their sexual health rather than harmful behaviors.

4.5 Pedagogical format

The curriculum consists of eight 60-min sessions that employ a range of instructional strategies to support diverse learning styles and engagement:

• Knowledge-Based Activities: These include sorting exercises, worksheets, and experiential learning cycle discussions to help students build a foundational understanding of key concepts.

• Exploration of Social Norms and Self-Concept: Activities such as anonymous live polling, guided discussions, and role-play scenarios encourage students to explore different perspectives, challenge social norms, and reflect on their own beliefs and self-image.

• Skill-Building Exercises: Hands-on demonstrations and practice sessions are designed to help students develop practical skills for making informed decisions and practicing healthy behaviors.

Table 1 provides an at-a-glance summary of each session, including its overarching aims, lesson specific objectives, and chronological activities. Detailed instructions for the practical implementation of specific activities, including sample lesson plans, are available in the supplemental materials accompanying this manuscript. While this table offers brief learning objectives, the full lesson plans include in-depth discussion prompts, role-plays, and reflection activities designed to foster analytical, ethical, and value-based reasoning.

4.5.1 Expanded session content and assessment strategies

• Session Structure: Each session begins with an icebreaker to engage learners and transitions into targeted activities that align with the day’s learning objectives. The session concludes with processing discussion questions to reinforce critical insights. These questions are designed to move students beyond factual recall and into value-based reasoning, encouraging them to apply concepts in ethically and socially relevant ways.

• Lesson Outlines: Summaries of the eight sessions (e.g., What Is Pornography? Understanding Intimacy, Consent & Boundaries) are included in Supplementary Materials, providing detailed lesson aims, step-by-step activities, and timing guidelines.

• Assessment:

• Formative Checks: Quick anonymous polls and reflective prompts gage ongoing comprehension and comfort levels, giving facilitators immediate feedback on student progress or distress.

• Pre-/Post-Lesson Quizzes: Brief quizzes measure shifts in knowledge on topics such as STI prevention or critical media literacy.

• Post-Session Reflections: Students can complete short written reflections or group debriefs to articulate what they learned and identify any lingering questions.

• Summative Evaluations: The curriculum includes a pre−/post-test survey for the entire course, capturing changes in attitudes, knowledge, and self-efficacy. Focus groups or interviews may also be conducted to explore more nuanced outcomes and potential improvements.

• Teacher Reflection: Facilitators complete session logs to reflect on lesson delivery, student engagement, and areas needing adaptation. This promotes continuous improvement in teaching practice.

• Long-Term Outcomes: Although not formally included in this version, future pilots are encouraged to incorporate longer-term follow-ups such as student portfolios, behavioral surveys, or re-assessment of attitudes and practices weeks or months after program completion to evaluate sustained impact.

Activities are intentionally varied and strategically sequenced to ensure that learning is dynamic and comprehensive. By alternating between knowledge-building, reflection of social norms and self-concept, and skill development, the curriculum provides a balanced approach that addresses both understanding and application, fostering deeper engagement with the material.

This curriculum is structured around eight lessons designed to build critical thinking, media literacy, and healthy sexual practices. The lessons are adaptable to different classroom settings, ensuring the curriculum is flexible and applicable to a wide range of educational environments.

To support educators in implementing the curriculum effectively, detailed lesson plans, including specific assessment tools and implementation guidelines, will be provided as supplemental material. These resources are designed to be practical and adaptable to fit the unique needs of various classroom contexts while maintaining the curriculum’s core objectives.

5 Results to date/need for pilot implementation and assessment

The “Navigating Realities” curriculum is the result of extensive literature review and analysis of existing sexual health education programs. It was developed by applying various educational theories and a media literacy framework to create a comprehensive approach to pornography literacy and sexual health for high school students. The curriculum draws on theories such as backward design, cultivation theory of mass media, and the triangle of sexual health, rights, and pleasure to provide a well-rounded educational experience that emphasizes critical thinking and responsible media consumption.

While this curriculum has not yet undergone pilot testing and the pre- and post-test questions still require formal validation, it is designed to reflect an innovative educational approach that will combine critical media literacy with sexual health education. The open and comprehensive framework of the curriculum addresses multiple aspects of sexual health, such as body image, consent, and healthy relationships, and integrates these topics within the context of media literacy.

Moving forward, the next steps include plans for pilot testing the curriculum in selected educational settings to gather data on its effectiveness and to refine the pre- and post-test evaluation tools. This iterative process will help ensure that the curriculum meets the diverse needs of students and is adaptable to different educational environments.

To prepare for pilot implementation, we have outlined two complementary processes: (1) content validation and (2) assessment-tool development. A structured expert-review process, including professionals in adolescent psychology, sexual-health education, and media literacy, will confirm developmental appropriateness, cultural sensitivity, and pedagogical coherence. Student feedback elicited through think-aloud sessions will further assess clarity, engagement, and relevance.

Alongside this review, draft assessment instruments, including pre/post-tests to measure knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions, have been developed and are included in the supplemental materials. Brief session-level reflection prompts and course-evaluation forms have likewise been drafted to capture real-time impressions of lesson quality and classroom climate. All tools will be refined during pilot testing to ensure reliability and validity.

To monitor real-time implementation challenges, the pilot will also include teacher logs and student debriefs, along with protocols for managing sensitive discussions or student disclosures in alignment with school policy.

Findings from the pilot, both quantitative (e.g., score gains) and qualitative (e.g., student quotations), will feed directly into the Evaluation and Monitoring Protocol described in Section 6. These efforts will support broader dissemination and ensure the curriculum can be effectively implemented across diverse educational environments.

5.1 Evaluation and monitoring protocol

To thoroughly assess effectiveness, monitor implementation challenges, and address potential adverse effects, a three-tiered evaluation approach will be used.

5.1.1 Outcome evaluation—pre/post-test design

Educators administer a pre/post-test to capture changes in students’ knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and self-efficacy in critically evaluating media. These questionnaires address themes such as critical thinking and media literacy, sexual health and relationships, digital safety, and the impact of pornography on sexual expectations. This evaluation is grounded in the Health Belief Model (Glanz et al., 2008), the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), Social Learning Theory (Bandura and National Inst of Mental Health, 1986), and Cultivation Theory (Gerbner et al., 2002).

5.1.2 Process evaluation—session-level feedback

At the conclusion of each lesson, students complete a brief course-evaluation form to rate content clarity, engagement, and instructional delivery. Trained facilitators maintain instructor logs to track classroom dynamics and flag emerging issues. Post-session debriefs provide opportunities to identify and respond to student concerns in real time. Should evidence of distress or well-being concerns arise, facilitators follow mandated-reporting protocols and connect students to appropriate support services.

5.1.3 Implementation monitoring—teacher & fidelity logs

Teachers document timing, adherence to lesson plans, and any adaptations made, allowing researchers to assess implementation fidelity and identify logistical barriers.

This layered framework, addressing both intended outcomes and unintended consequences, ensures data-driven refinements and promotes the welfare of all participants. Evaluation findings will be interpreted through a theoretical lens aligned with adolescent-development research (Steinberg, 2010) and evidence-based porn-literacy models (Rothman et al., 2020).

Regular evaluation cycles are recommended to inform curriculum adaptations, including lesson pacing, content modifications, and instructional strategies. By explicitly linking each data stream to decision-making points, the protocol supports an iterative improvement process that remains responsive to student needs, cultural contexts, and educator capabilities.

6 Discussion on practical implications, objectives, and lessons learned

This paper aims to both introduce the “Navigating Realities” curriculum and advocate a unique approach to pornography literacy education through comprehensive media literacy, critical thinking, and a sex-positive framework. The curriculum’s practical implications are profound, as it equips students with the critical tools needed to navigate the complex realities of pornography and sexual media in a digital age. The curriculum’s significance lies in its potential to support young people in navigating pornography in a way that supports sexual health. A broader goal is to foster healthier relationships with oneself and others by addressing pornography’s portrayal of bodies, consent, and violence within sexual or dating relationships. Moreover, this course addresses intersectional issues related to stereotypes, recognizing the impact of pornography on perpetuating cycles of inequality and violence. Given the inevitability of adolescent exposure to explicit content, proactive educational interventions are necessary despite potential resistance.

Integrating pornography literacy into broader sexual health education addresses a significant gap in traditional sex education, which often overlooks the influence of digital media on adolescents’ perceptions of sex, relationships, and body image. However, implementing a sex-positive, rights-based approach such as this may face political and cultural barriers. Educational institutions may encounter policy restrictions and varied administrative support, particularly in conservative districts, while communities with differing values might resist open discussions about sexuality and pleasure.

To overcome potential implementation challenges, the curriculum is designed with flexibility to align with existing sex education standards and accommodate limited class time. Teachers may initially experience discomfort addressing sensitive topics or face pushback from stakeholders. Therefore, comprehensive teacher training, ongoing support resources, and strategies for engaging parents should be provided to ensure effective and culturally sensitive implementation.

Key lessons from developing this curriculum highlight the importance of addressing sensitive topics in a supportive, non-judgmental environment. Providing safe spaces for open discussion allows students to reflect on personal values and societal norms. The curriculum deliberately avoids fear-based messaging, favoring evidence-informed strategies that affirm pleasure, consent, and healthy relationships. Parental involvement is recognized as essential, as families play a pivotal role in shaping adolescents’ attitudes toward sexuality and media. Engaging parents early helps build transparency, alleviates concerns, and reinforces the curriculum’s values at home.

Overall, “Navigating Realities” offers an innovative, comprehensive approach to adolescent sexual health education that emphasizes critical media literacy, healthy relationships, and positive sexual rights and pleasure. As the curriculum continues to evolve, ongoing evaluation and adaptation will ensure its continued relevance, effectiveness, and inclusivity across diverse educational settings.

7 Acknowledgment of conceptual, methodological, environmental, and material constraints

Implementing this curriculum faces several challenges that need to be carefully addressed to ensure its effectiveness:

• Content Validation Constraints: The curriculum has not yet undergone expert validation by professionals in adolescent psychology, sexual health education, or media literacy. While it draws from peer-reviewed literature and pedagogical theory, further refinement will require systematic input from external experts to ensure content accuracy, developmental appropriateness, and alignment with established standards. Plans for expert consultation during pilot testing are outlined in Section 5.

• Assessment Tool Limitations: The proposed pre- and post-test measures, while informed by theoretical frameworks, have not yet been validated. These tools were developed based on constructs from the Health Belief Model, Theory of Planned Behavior, and related frameworks but require piloting to confirm their reliability and validity. This represents a critical area for future development.

• Conceptual Constraints: Striking a balance between providing comprehensive sexual education, including pornography literacy, and respecting societal and cultural sensitivities around these topics remains a significant challenge. Educators must navigate diverse values and beliefs while delivering age-appropriate content that promotes informed decision-making and healthy behaviors. Additionally, the curriculum is designed with a sex-positive and rights-based approach, which may conflict with cultural or familial norms in certain conservative or religious communities. This underlying pedagogical philosophy assumes openness to discussions about sexual health and media, which may not align with all audiences. These assumptions require further testing and adaptation to ensure relevance and acceptability.

• Methodological Constraints: The curriculum needs to be adaptable to various educational settings, student demographics, and learning styles. This requires flexibility in instructional design, allowing educators to modify activities and discussions to fit the unique needs of different classrooms while maintaining core objectives.

• Environmental Constraints: Variability in access to resources and differing levels of parental support and consent can impact the delivery and reception of the curriculum. Engaging parents and gaining their buy-in is crucial for successful implementation. Schools must also consider potential resistance and develop strategies for fostering open communication with families. Additionally, adaptations, such as replacing examples with culturally relevant examples, conceptually framing sensitive content, and sequencing lessons to build parental trust, have been incorporated to expand the curriculum’s applicability. However, schools willing to implement a pornography literacy curriculum are likely to be more progressive or reform oriented. This represents an inherent limitation of the topic area at this stage.

• Material Constraints: Limited availability of digital devices and technological resources for interactive activities, such as anonymous polling, may hinder the full implementation of the curriculum’s design. However, activities can be adapted to use no technology, instead using a whiteboard and open discussion.

Despite these challenges, the curriculum marks a critical step toward addressing the realities of adolescent exposure to pornography and fostering healthier sexual practices through a comprehensive educational approach. Developed with available resources and current research, it acknowledges that expert input is essential for refining effectiveness and age-appropriateness. To that end, the next steps include piloting the curriculum, soliciting expert and educator feedback, and revising accordingly to align with best practices in sexual health education.

To ensure fidelity, a trained facilitator, external or internal with relevant experience, will conduct all sessions. Pre- and post-tests will assess knowledge gains and inform continuous improvements. Pilot testing will also guide decisions on long-term implementation and potential adaptation for broader use.

If the curriculum proves effective, a comprehensive training course will be developed to support educator onboarding and scale-up. As interest in pornography literacy education expands, the curriculum may be adapted for older students, such as those in college, ensuring age-appropriate and contextually relevant content.

One recognized limitation is the variability in student knowledge, cultural norms, and engagement levels across schools. These factors may influence discussions, perceptions of social norms, and curriculum relevance. The current design assumes a baseline willingness to discuss sexual health, which may not hold in all communities. These challenges highlight the importance of ongoing feedback and iterative refinement to ensure cultural inclusivity and accessibility.

These limitations underscore the need for a robust pilot phase involving both expert review and classroom testing. Publishing this proposed curriculum provides an opportunity to initiate broader conversations and collaboration in an underdeveloped area of adolescent health education. However, its full effectiveness, inclusivity, and scalability will depend on future validation, iterative refinement, and stakeholder feedback.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1509262/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA SHEET 1 | Navigating realities: full curriculum toolkit.

References

Adarsh, H., and Sahoo, S. (2023). Pornography and its impact on adolescent/teenage sexuality. J. Psychosexual Health 5, 35–39. doi: 10.1177/26318318231153984

Atif, H., Peck, L., Connolly, M., Endres, K., Musser, L., Shalaby, M., et al. (2022). The impact of role models, mentors, and heroes on academic and social outcomes in adolescents. Cureus 14, 2–11. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27349

Aventin, Á., Gough, A., McShane, T., Gillespie, K., O'Hare, L., Young, H., et al. (2020). Engaging parents in digital sexual and reproductive health education: evidence from the JACK trial. Reprod. Health 17:132. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-00975-y

Balén, Z., Pliskin, E., Cook, E., Manlove, J., Steiner, R., Cervantes, M., et al. (2024). Strategies to develop an LGBTQIA+-inclusive adolescent sexual health program evaluation. Front. Reprod. Health 6:1327980. doi: 10.3389/frph.2024.1327980

Bandura, A., and National Inst of Mental Health. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

‘Be Positive—The Pleasure Project’ (2022). Be positive: core to all the pleasure principles is being sex-positive. Available online at: https://thepleasureproject.org/the-pleasure-principles/be-positive/# (Accessed: 12 September 2024).

Best practices for family engagement in sex education implementation. (2025). Available online at: https://www.wisetoolkit.org/sites/default/files/Best%20Practices%20for%20Family%20Engagement_formatted.pdf

Biota, I., Dosil-Santamaria, M., Mondragon, N. I., and Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N. (2022). Analyzing university students’ perceptions regarding mainstream pornography and its link to SDG5. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:8055. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19138055

Cavener, J., and Lonbay, S. (2022). Enhancing ‘best practice’ in trauma-informed social work education: insights from a study exploring educator and student experiences. Soc. Work. Educ. 43, 317–338. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2022.2091128

Cerniglia, L., and Cimino, S. (2024). Pornography consumption in pre−/early adolescents: a study on the links with emotion regulation and internalizing/externalizing symptoms. Curr. Psychol. 43, 27414–27422. doi: 10.1007/s12144-024-06380-z

Child abuse prevention and treatment act (CAPTA). (2023). Available online at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/attachment_c_capta.pdf (Accessed April 3, 2025)

Cipolletta, S., Malighetti, C., Cenedese, C., and Spoto, A. (2020). How can adolescents benefit from the use of social networks? The iGeneration on Instagram. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:6952. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17196952

Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications (2019) in The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. eds. R. J. Bonnie and E. P. Backes (Washington, D.C: National Academies Press).

Crabbe, M., and Flood, M. (2021). School-based education to address pornography’s influence on young people: a proposed practice framework. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 16, 1–37. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2020.1856744

Davis, A., Wright, C., Murphy, S., Dietze, P., Temple-Smith, M., Hellard, M., et al. (2020). A digital pornography literacy resource co-designed with vulnerable Young people: development of the gist. J. Med. Internet Res. 22:e15964. doi: 10.2196/15964

Department of Education (2024) Policies and procedures for mandated reporting. Readiness and emergency management for schools. Available online at: https://rems.ed.gov/ASM_Chapter2_Reporting.aspx (Accessed April 3, 2025)

Epstein, J. L. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. New York: Routledge. Available online at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780429494673/school-family-community-partnerships-joyce-epstein

Evans-Paulson, R., Dodson, C. V., and Scull, T. M. (2024). Critical media attitudes as a buffer against the harmful effects of pornography on beliefs about sexual and dating violence. Sex Educ. 24, 799–815. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2023.2241133

Ford, J. V., Ivankovich, M. B., Douglas, J. M., Hook, E. W., Barclay, L., Elders, J., et al. (2017). The need to promote sexual health in America: a new vision for public health action. Sex. Transm. Dis. 44, 579–585. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000660

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., Signorielli, N., and Shanahan, J. (2002). “Growing up with television: cultivation processes” in Media effects: Advances in theory and research. eds. J. Bryant and D. Zillmann. 2nd ed (Hillsdale, NJ: Routledge), 43–67.

Glanz, K., Rimer, B. K., and Viswanath, K. (2008). Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. San Fransisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Gola, M., Wordecha, M., Sescousse, G., Lew-Starowicz, M., Kossowski, B., Wypych, M., et al. (2017). Can pornography be addictive? An fMRI study of men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 2021–2031. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.78

Gruskin, S., Yadav, V., Castellanos-Usigli, A., Khizanishvili, G., and Kismödi, E. (2019). Sexual health, sexual rights, and sexual pleasure: meaningfully engaging the perfect triangle. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 27, 29–40. doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1593787

Hald, G. M. (2006). Gender Differences in Pornography Consumption among Young Heterosexual Danish Adults. Archives of Sexual Behav. 35, 577–585. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9064-0

Healy-Cullen, S., and Morison, T. (2023). “Porn literacy education: a critique” in The Palgrave encyclopedia of sexuality education. ed. M. L. Rasmussen (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 1–13.

Healy-Cullen, S., Taylor, J. E., Morison, T., and Ross, K. (2022). Using Q-methodology to explore stakeholder views about porn literacy education. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy, 19, 549–561. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00570-1

Hu, Z., Sun, H., Liang, H., Cao, W., Hee, J. Y., Yan, Y., et al. (2024). Pornography consumption, sexual attitude, and Condomless sex in China. Health Commun. 39, 73–82. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2156738

Irizarry, R., Gallaher, H., Samuel, S., Soares, J., and Villela, J. (2023). How the rise of problematic pornography consumption and the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a decrease in physical sexual interactions and relationships and an increase in addictive behaviors and cluster B personality traits: a meta-analysis. Cureus 15, 1–4. doi: 10.7759/cureus.40539

Jhe, G. B., Addison, J., Lin, J., and Pluhar, E. (2023). Pornography use among adolescents and the role of primary care. Family Med. Community Health 11:e001776. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2022-001776

Litsou, K., Byron, P., McKee, A., and Ingham, R. (2021). Learning from pornography: results of a mixed methods systematic review. Sex Educ. 21, 236–252. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1786362

Maas, M. K., Gal, T., Cary, K. M., and Greer, K. (2022). Popular culture and pornography education to improve the efficacy of secondary school staff response to student sexual harassment. American J. Sexuality Educ. 17, 435–457. doi: 10.1080/15546128.2022.2076757

Mark, K., Corona-Vargas, E., and Cruz, M. (2021). Integrating sexual pleasure for quality & inclusive comprehensive sexuality education. Int. J. Sex. Health 33, 555–564. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2021.1921894

Pappas, S. (2021). Teaching porn literacy. Monit. Psychol. 52:54. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/03/teaching-porn-literacy

Paulus, F. W., Nouri, F., Ohmann, S., Möhler, E., and Popow, C. (2024). The impact of internet pornography on children and adolescents: a systematic review. L'Encephale 50, 649–662. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2023.12.004

Peter, J., and Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). Adolescents and pornography: a review of 20 years of research. J. Sex Res. 53, 509–531. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1143441

Rege, K. P. (2022) Internet pornography: awareness among adolescents and youth (13-26 years) Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kamini-Rege/publication/368507427_INTERNET_PORNOGRAPHY_AWARENESS_AMONG_ADOLESCENTS_AND_YOUTH_13-26_YEARS/links/63eda9cf2958d64a5cd33421/INTERNET-PORNOGRAPHY-AWARENESS-AMONG-ADOLESCENTS-AND-YOUTH-13-26-YEARS.pdf (Accessed April 3, 2025)

Robb, M. B., and Mann, S. (2022). 2022 teens and pornography. Common Sense Media. Available online at: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/research/report/2022-teens-and-pornography-final-web.pdf (Accessed April 3, 2025)

Rodenhizer, K. A. E., and Edwards, K. M. (2019). The impacts of sexual media exposure on adolescent and emerging adults’ dating and sexual violence attitudes and behaviors: a critical review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 20, 439–452. doi: 10.1177/1524838017717745

Rosenstock, I. M., Strecher, V. J., and Becker, M. H. (1988). Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ. Q. 15, 175–183.

Rothman, E. F., Daley, N., and Alder, J. (2020). A pornography literacy program for adolescents. Am. J. Public Health 110, 154–156. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305468

Rousseau, A., Beyens, I., Eggermont, S., and Vandenbosch, L. (2017). The dual role of media internalization in adolescent sexual behavior. Arch. Sex. Behav. 46, 1685–1697. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0902-4

Schiavo, R. (2014). Health communication: From theory to practice. Second Edn. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Somerville, L. H. (2013). The teenage brain: sensitivity to social evaluation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 121–127. doi: 10.1177/0963721413476512

Steinberg, L. (2010). A behavioral scientist looks at the science of adolescent brain development. Brain Cogn. 72, 160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.11.003

UNESCO (2018). International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Vandenbosch, L., and Eggermont, S. (2015). The role of mass media in adolescents' sexual behaviors: exploring the explanatory value of the three-step self-objectification process. Arch. Sex. Behav. 44, 729–742. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0292-4

Wahl, D. W. (2023). Pornographic turning points in the life course: uses of pornography in sexual self-development. Porn Stud. 12:17. doi: 10.1080/23268743.2023.2262475

Wiggins, G., and McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development ASCD. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 19,140–142.

Wright, P. J., and Herbenick, D. (2024). Adolescent pornography exposure, condom use, and the moderating role of parental sexual health communication: replication in a U.S. probability sample. Health Commun. 40, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2024.2386215

Keywords: pornography literacy, sex education, media literacy, adolescent sexual health, comprehensive education, curriculum

Citation: Balliet ME and Ford JV (2025) Navigating realities: a pornography literacy and sexual health curriculum for high school students. Front. Educ. 10:1509262. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1509262

Edited by:

Gaia Zori, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher M. Fisher, Victoria University, AustraliaJennifer Power, La Trobe University, Australia

Riza Hayati Ifroh, Northeast Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Balliet and Ford. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margot E. Balliet, bWI1MDIwQGN1bWMuY29sdW1iaWEuZWR1

Margot E. Balliet

Margot E. Balliet Jessie V. Ford

Jessie V. Ford