- 1Department of Impulses in Education, ÖZBF, University of Education Stefan Zweig, Salzburg, Austria

- 2Department of Educational Sciences, ÖZBF, University of Education Stefan Zweig, Salzburg, Austria

Introduction: Teachers’ beliefs about their students’ giftedness and talent are relevant to teaching quality and educational processes. Teachers’ beliefs about giftedness have been investigated in mathematics. In our research, we extended this approach to verbal giftedness to examine whether teachers’ beliefs concerning verbal giftedness can be assessed in a manner similar to their talent beliefs in mathematics.

Methods: To this end, we developed and tested a questionnaire to elicit participants’ verbal talent beliefs through a quantitative survey of 207 student teachers.

Results: A six-factor model, similar to the mathematics talent beliefs model, showed good model fit. In the structural model, verbal talent beliefs predicted both student teachers’ growth mindsets and self-efficacy.

Discussion: This questionnaire on verbal talent beliefs can be used in future research projects to optimize teacher education, to better understand educational processes, and facilitate the participation of all students, including gifted students.

1 Introduction

Teachers’ beliefs are particularly important in trying to better understand what influences teachers’ behavior, actions and reactions. They are relevant to the quality of teaching and successful teaching-learning processes, for example by guiding pedagogical actions in the classroom (e.g., Calderhead, 1996; Baumert and Kunter, 2006; Goldin et al., 2009; Fives and Buehl, 2012; König, 2012; Reusser and Pauli, 2014; Rogl, 2022). Teaching and learning quality models therefore include teacher beliefs at a theoretical level. They illustrate complex intercorrelations and influences on student achievement caused by teachers’ beliefs, professional knowledge, cognitive activation in the classroom, constructive support, and classroom management (e.g., Helmke, 2010; Klieme and Rakoczy, 2008; Reusser and Pauli, 2010). Large-scale studies on teaching and teacher professional research [e.g., the Teacher Education and Development Study-Mathematics (TEDS-M), Tatto et al., 2008] have measured teachers’ beliefs to determine their formative function and immediate relevance for the design of instructional situations at a theoretical and empirical level.

Beliefs about giftedness and talent are part of teachers’ beliefs. They are subjective (Hany, 1997) and based on either explicit or implicit theories (Sternberg and Kaufman, 2018). Talent beliefs influence the identification of gifted students, their perceived needs or the offered supportive strategies (e.g., Grosch, 2011; Hany, 1997; Sternberg and Davidson, 2005). The link between giftedness concepts, beliefs and classroom instruction has been emphasized:” In an applied field such as gifted education, practitioners operationalize their beliefs and understandings about giftedness – their definitions – into identification practices, service delivery models, and approaches to classroom instruction” (Olszewski-Kubilius et al., 2015, p. 143).

2 Conceptual background of teachers’ talent beliefs

The question of whether giftedness and talent beliefs resemble scientific models was raised already in the end of 20th century (Hany, 1997) and continues to this day (Sternberg and Kaufman, 2018). Previous studies mostly capture bipolar models (e.g., beliefs about stability and innateness of giftedness versus conceptual change beliefs concerning the learnability of mathematics in the MT21 study, Blömeke et al., 2008b) in contrast to the multidimensional concepts of giftedness postulated in talent development research. Findings on talent beliefs have also predominantly revealed stereotypes about the social behaviors and emotional needs of gifted students, such as the presence of disharmonic hypotheses (Baudson, 2016; Baudson and Preckel, 2013; Preckel et al., 2015) or in individual aspects of talent beliefs, such as static-dynamic bipolarity in the concept of giftedness (e.g., Heller et al., 2001; Laine, 2010; Makel et al., 2015; Russell, 2018; Ziegler and Stöger, 2010). Thus, there is a biased tendency in terms of content in the operationalization of talent beliefs. Furthermore, the questionnaires and instruments used in professional teacher research mostly use single items on giftedness and talent (e.g., the TEDS-M, Laschke and Schmotz, 2013). Instruments developed in talent development research have not been applied domain-specifically but have been formulated only in general terms in relation to talent beliefs or focused only on subtypes (Baudson, 2016; Gagné, 2018; Ziegler and Stöger, 2010). Consequently, there is a need for a more comprehensive theoretical model and for a precise operationalization of these multidimensional talent beliefs.

Rogl, 2022 assessed teachers’ talent beliefs domain-specifically in mathematics and found five of the six estimated dimensions (theoretically derived and empirically supported): domain-specific skills, passion, achievement, determination and internal factors, some of which predicted cognitively activating teaching (with 19% of the variance explained). As teachers’ talent beliefs in mathematics have been shown to be an important construct to explore, we aimed to broaden the approach to other domains, particularly verbal giftedness, to ascertain whether teachers’ talent beliefs about verbal giftedness can be measured similarly to their talent beliefs in mathematics. We chose the domain” verbal” in accordance with the usage of verbal giftedness in recognized model conceptions (e.g., Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent [DGMT], Gagné, 2005; The Munich Model of Giftedness, Heller et al., 2005). Additionally, verbal domains in intelligence tests as well as elaborated didactic models and concepts for language aptitude exist (e.g., Farkas, 2014; Wagner, 2014). Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge the importance of language in the development of cognitive empathy, also known as the theory of mind (ToM), which comprises both cognitive and affective components (e.g., Bigelow et al., 2021). Research findings have also indicated that foreign language aptitude and the ability to learn one’s native language are closely linked (e.g., Skehan, 1998). It is also encouraging to note that educational practice has recently seen a positive shift in the promotion of verbally talented students (e.g., giftedness-promoting manuals in Austria: Austrian Research and Support Center for Gifted and Talented (ÖZBF), 2022; Schmid et al., 2023). These findings have motivated us to delve into the domain of verbal giftedness. In this understanding, verbal giftedness describes the performance-related ability to write, read, communicate (verbally, in body language, vocally) and reflecting on texts and conversations. Verbal giftedness is dynamic and includes not only language-specific and cognitive factors but also depends on various environmental influences such as school environment or extracurricular support. Verbal talents manifest in different ways in terms of performance. Talented students are often enthusiastic about speaking, reading and writing, have a high level of creativity and the ability to abstract and divergent thinking. They pay great attention to well-formedness and correctness both in their own texts and in texts written by others. When composing and creating texts, they sometimes use a wealth of rhetorical devices to present facts in a structured, precise and eloquent manner (e.g., Bertschi-Kaufmann and Gyssler, 2014).

2.1 Characteristics of teachers’ talent beliefs in this study

Teachers’ talent beliefs in this study are beliefs about giftedness and talent of students. They are affectively loaded, provided with a normative valuation, and based on an individual set of assumption of accuracy. These beliefs nevertheless also represent the person’s knowledge about giftedness. Talent beliefs relate to learning content, learning processes, instructional approaches, learner identity, or the role of the teacher. They guide direct perceptions in classroom and individual settings, or even conceptual thinking when planning supportive tasks, interventions, grouping, and enrichment strategies (Rogl, 2022). These characteristics are based on the definition of teachers’ beliefs by Reusser and Pauli (2014): teachers’ beliefs are affectively driven understandings of teaching-learning processes, learning content, the role of learners and teachers, and the context of education, which provide structure and orientation for professional thinking and action (Reusser and Pauli, 2014). This definition is accepted in the context of German-speaking countries and is repeatedly cited and used (e.g., Steinmann and Oser, 2012; Terhart et al., 2014), however, it is not possible to call it a generally accepted common definition. Talent beliefs serve three important functions (referring to functions of teachers’ beliefs, Fives and Buehl, 2012). First, talent beliefs implicitly filter information and experiences, influencing perceptions and interpretations. They shape the way new information and experiences are categorized and interpreted. Second, in terms of talent belief design situations and tasks, the framing function of beliefs is demonstrated through constructing social reality, interpreting behaviors, and shaping relationships. Third, talent beliefs guide intention and action such that once a situation is defined, the steering function of beliefs begins to guide action. Talent beliefs influence teachers’ goals and guide their efforts towards achieving them. Choices, effort, and persistence influence educators’ quality (Rogl, 2022).

Teachers’ talent beliefs include affective-emotional, normative, and subjective aspects as well as professional knowledge. They are representative of teachers’ knowledge of giftedness and talent development (learning processes, instructional approaches, and the role of teachers).

2.2 Empirical evidence on talent beliefs in prior research

Teachers’ talent beliefs play a rather minor role in the field of educational research, “implicit beliefs about giftedness are currently underexamined “(Makel et al., 2015, p. 203). An international meta-analysis in the research field of giftedness counted 45 quantitative studies (5%) and 28 qualitative studies (9%) on teacher beliefs (Dai et al., 2011). Research on talent beliefs is predominantly concerned with how teacher beliefs influence the nomination of students for specific enrichment programs. The impact of talent beliefs on classroom instruction is rarely studied (Tofel-Grehl and Callahan, 2017).

In synopsis, both qualitative and quantitative studies of talent beliefs consistently reveal theoretical references and characteristic research questions in common (Rogl, 2022): The represented conception of giftedness is mainly multidimensional. Moderator approaches shape this multidimensional view of giftedness with diverse influencing factors (Hany, 1997; Laine, 2010; Russell, 2018), for instance also due to the use and adaptation of Gagné’s (2018) and Nadeau’s items to investigate beliefs about giftedness in several studies (e.g., Gagné, 2018; McCoach and Siegle, 2007; Troxclair, 2013). In terms of the theoretical orientation, studies on stable versus dynamic views of giftedness and talent development are mostly based on the approaches to implicit personality theories (incremental versus entity implicit theory or growth versus fixed mindset; Dweck, 1986, 1999, 2008; Dweck and Leggett, 1988). Mindset research has recently been expanded to examine context- and individual-specific approaches, referred to as “field-specific ability beliefs” (FABs) (e.g., Asbury et al., 2023). FABs capture differences in teachers’ mindsets in different domains (Heyder et al., 2020; Asbury et al., 2023). For instance, math teachers have shown a more fixed mindset compared to German teachers (Heyder et al., 2019). Teachers’ FABs were also associated with students’ motivation and performance in mathematics (Heyder et al., 2019). Research on stereotypes about the gifted and talented mainly draws on the theory of harmony and disharmony hypothesis, to explain the observable contrasting associations of giftedness and talented individuals and their socio-emotional (im)balance (Baudson, 2016; Baudson and Preckel, 2013; Preckel et al., 2015).

Eight main topics of interest emerge in a review of the studies on talent beliefs (Rogl, 2022): questions about the dynamic vs. static view of giftedness (Blömeke et al., 2008b; Dweck, 1999; Hany, 1997; Heller et al., 2001; Laine, 2010; Laine et al., 2016; Makel et al., 2015; Russell, 2018; Ziegler and Stöger, 2010), the innate nature of giftedness (Blömeke et al., 2008b; Russell, 2018), multidimensional concepts of giftedness (Laine, 2010), the environmental dependence of talent development (Hany, 1997; Laine, 2010), the intrapersonal components of giftedness (Laine, 2010), the achievement and performance dimensions of giftedness (Laine et al., 2016), teachers as important external influences (Heller et al., 2001; Russell, 2018), and social–emotional exceptionalities in gifted students (Baudson, 2016; Baudson and Preckel, 2013, 2016; Moon and Brighton, 2008; Preckel et al., 2015).

Studies on teachers’ talent beliefs cover the following two subject-areas of beliefs (Rogl, 2022): epistemological beliefs about the structure and nature of teachers’ talent beliefs (Blömeke et al., 2008a; Heller et al., 2001; Laine et al., 2016; Russell, 2018) and their person-based beliefs about gifted students (Baudson and Preckel, 2013, 2016; Carman, 2011; Moon and Brighton, 2008; Troxclair, 2013).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Research question of the present study

As teachers’ talent beliefs guide their perceptions and actions in the classroom, they are relevant constructs to address. Little research has specifically explored teachers’ talent beliefs or measured them using empirically sound instruments. Rogl (2022) assessed teachers’ beliefs about mathematical talent. However, assessment has not been developed in other domains. Thus, we developed an instrument for assessing verbal talent beliefs based on the theoretical literature on high verbal abilities (e.g., Carroll, 1990; Bertschi-Kaufmann and Gyssler, 2014; Carroll and Sapon, 1959; Farkas, 2014; Laudenberg and Spiegel, 2020; Wagner, 2014; Wen and Skehan, 2011) and the model used in mathematics (Rogl, 2022). In this study, we aimed to address the following research questions:

• Is it possible to measure talent beliefs in the verbal domain, as in mathematics, with an adapted version of the previous mathematics talent beliefs questionnaire (Rogl, 2022)?

• Is the factor structure for verbal talent beliefs similar to mathematics?

• Is it possible to predict growth mindset (Rammstedt et al., 2022; Research Data Center at the Institute for Quality Development in Education, 2019) and teacher self-efficacy (Schwarzer and Schmitz, 2002) by verbal talent beliefs?

3.2 Procedure

We developed the questionnaire items in accordance with the talent beliefs questionnaire in mathematics (Rogl, 2022) but modified to apply to the verbal domain instead of mathematics. Several optimization and modification stages were involved, including: a discussion about the items with five target group members (i.e., teachers) for content validity; cognitive interviews involving thinking aloud, inquiry, and paraphrasing with four professionals in teacher education specialized in linguistic domains for construct validation; and a quantitative survey with student teachers for testing the factor structure and convergent validity, the results of which are presented in this study. We recruited student teachers who completed the questionnaire through university courses. Participation in the study was voluntary. As an incentive, participants could win five vouchers of 50€ each from a local bookstore.

3.3 Sample

In the survey to test the factor structure and convergent validity of the newly developed verbal talent beliefs questionnaire, 207 student teachers for secondary school from two Austrian1 universities participated. In total, 68% were female, 1% were diverse, 28% were male, and 3% did not specify their sex. In addition to studying at university, 5% had already worked as teachers. The majority had just begun their study program; 82% were first-semester students. The mean age of the participants was M = 22.01 years [standard deviation (SD) = 5.96, Min = 18, Max = 50]. When asked where their beliefs about verbal talent stemmed from, they agreed most with the item: experiences in my own schooldays (M = 79.16, SD = 20.96, on a scale ranging from 0 to 100). They tended not to select: experiences from educational science courses (M = 38.64, SD = 30.10), experiences from subject didactic courses (M = 37.49, SD = 29.73), and experiences from internships (M = 29.21, SD = 32.19), which was not surprising because most of the participating student teachers had just started their studies.

3.4 Instruments

The survey was administered online via the software LimeSurvey. It consisted of the newly developed verbal talent beliefs questionnaire, four items concerning where their beliefs about verbal talents stem from (with results obtained as previously noted), a growth vs. fixed mindset scale, a teacher self-efficacy scale, demographic data, and the mathematics talent beliefs questionnaire (Rogl, 2022) that was not the subject of this study.

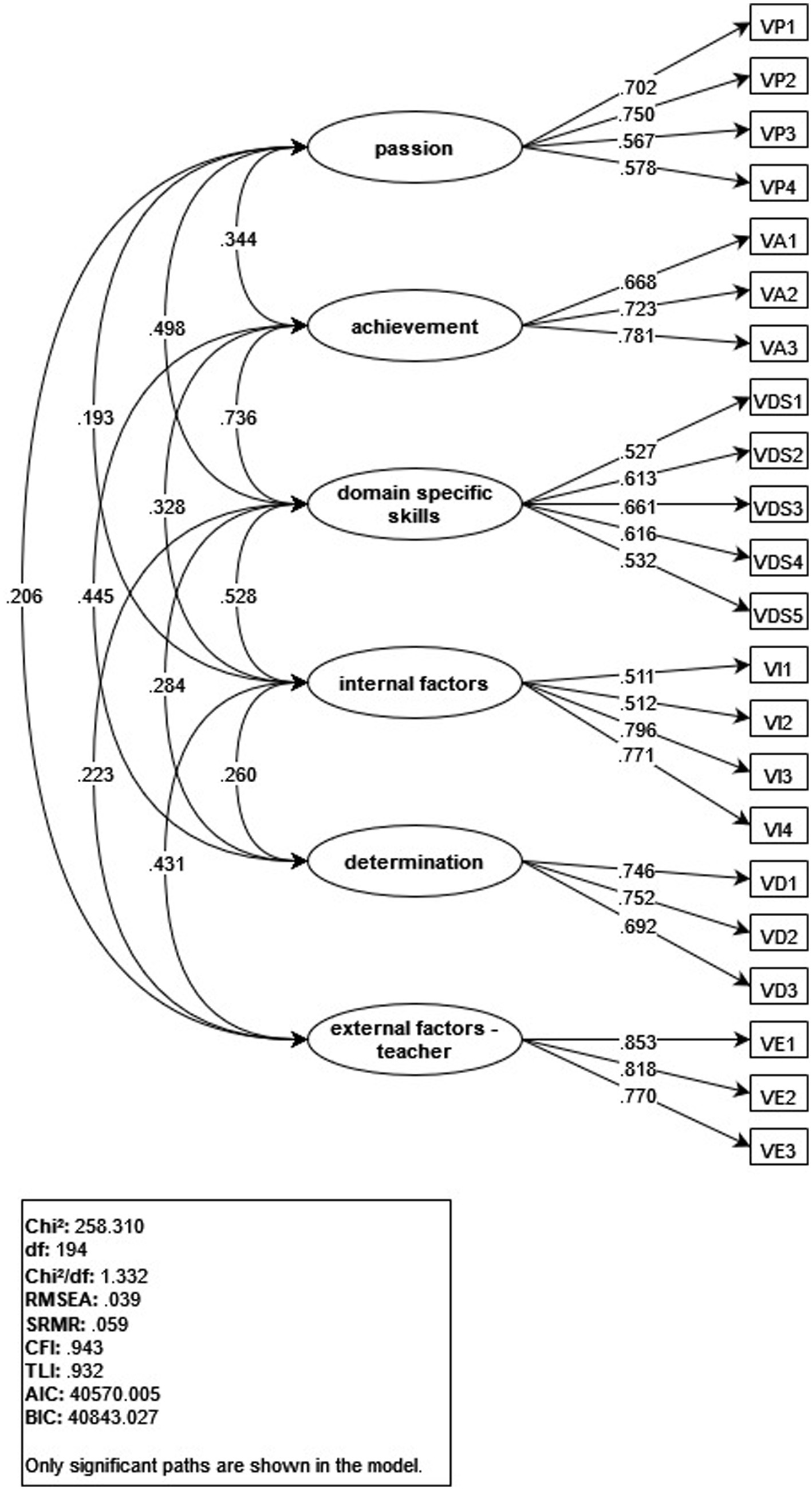

3.4.1 Verbal talent beliefs questionnaire

All items were adapted from the talent beliefs questionnaire (Rogl, 2022) and pretested for content and construct validity, as previously described. The questionnaire, in its final version – after eliminating items with factor loadings <0.5 or items that cross-loaded on various factors – consisted of 22 items with factor loadings on six scales: passion (4 items, α = 0.742, e.g., I am convinced that verbally gifted students read with enthusiasm), achievement (3 items, α = 0.752, e.g., I am convinced that verbal giftedness is visible through excellence in language lessons), domain-specific skills (5 items, α = 0.720, e.g., I am convinced that verbally gifted students are characterized by brilliant rhetoric), internal factors (4 items, α = 0.745, e.g., I am convinced that students’ verbal giftedness benefits from a high ability to concentrate), determination (3 items, α = 0.773, e.g., I am convinced that verbal giftedness is innate), and external factors – teacher (3 items, α = 0.852, e.g., I am convinced that students’ verbal giftedness benefits from my enthusiasm for languages as a teacher). The first five scales were similar to those used in the mathematics talent beliefs questionnaire. We used items in randomized order with the same introductions. The German version of the questionnaire, which has been tested, and the English translation, which has not yet been tested, can be found in the Supplementary material.

3.4.2 Growth vs. fixed mindsets

To measure student teachers’ growth or fixed mindsets, we used an adapted version of the 3-item growth-mindset scales (Rammstedt et al., 2022; Research Data Center at the Institute for Quality Development in Education, 2019), with all three items focused on a fixed mindset concerning intelligence, expressed as follows: I have a certain intelligence and there’s not much I can do about it. Responses were obtained on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from “not true” to “exactly right.” To compute a growth-mindset score, the items had to be inverted. In our study the internal consistency was α = 0.80.

3.4.3 Teacher self-efficacy

We assessed teacher self-efficacy using the 8-item scale of Schwarzer and Schmitz (2002), with an example item being: I know that I can teach even the most problematic students the material relevant to the exam. Responses were also obtained on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from “not true” to “exactly right.” Item 7, which was phrased negatively, was recoded. In this study, the internal consistency of the teacher self-efficacy scale was α = 0.61.

3.5 Analyses

We used MPlus 8.10 to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and test convergent validity in a structural equation model predicting student teachers’ growth mindsets and teacher self-efficacy based on their verbal talent beliefs. We expected small to medium regression coefficients based on theoretical assumptions about similar, albeit different, constructs, namely, beliefs and self-efficacy (Matheis et al., 2017) and growth/fixed mindsets concerning intelligence and giftedness (Ziegler and Stöger, 2010).

Multiple linear regression was used to estimate model parameters and goodness-of-fit in the CFA as well as the structural equation model, with root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ≤ 0.08, comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.95, and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.95 (Brown, 2015; Hu and Bentler, 1999) indicating adequate fit. Additionally, the chi-square/df ratio ≤ 3 rule was used (Kline, 2016). Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-squared difference tests were used for model comparisons.

4 Results

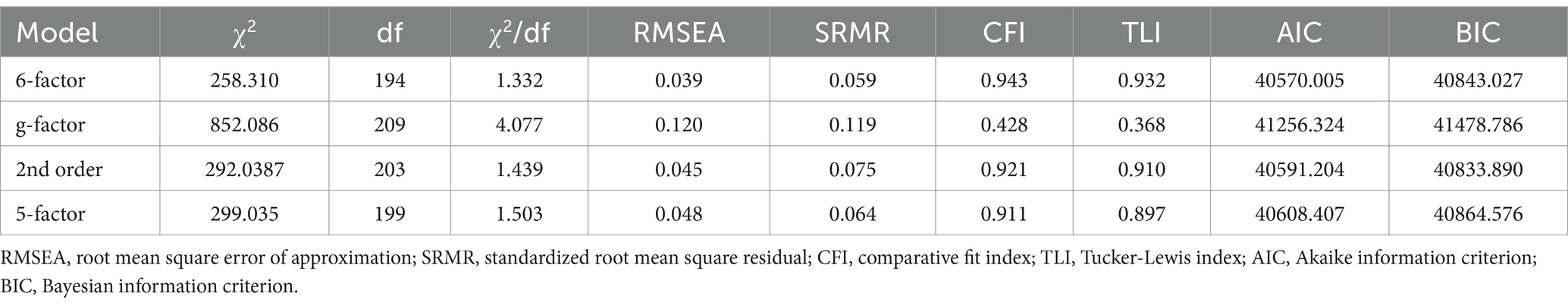

We identified a six-factor model for teachers’ talent beliefs in the verbal domain with adequate model fit (χ2/df = 1.332; RMSEA = 0.039; SRMR = 0.059; CFI = 0.943; TLI = 0.932) and correlated factors in accordance with the model applied in mathematics (passion, achievement, domain-specific skills, internal factors and determination), but also with the addition of a sixth factor, external factors – teacher concerning teachers’ influence on students’ verbal talents. The model fitted the empirical data better than a g-factor model (χ2 = 486.382, df = 15, p = 0.000), as well as a second-order (χ2 = 20.027, df = 9, p = 0.018) and a five-factor model that combined achievement and domain-specific skills to one factor because of their high correlation (χ2 = 23.843, df = 5, p = 0.000). The six-factor model is illustrated in Figure 1. Table 1 presents an overview of the model comparisons.

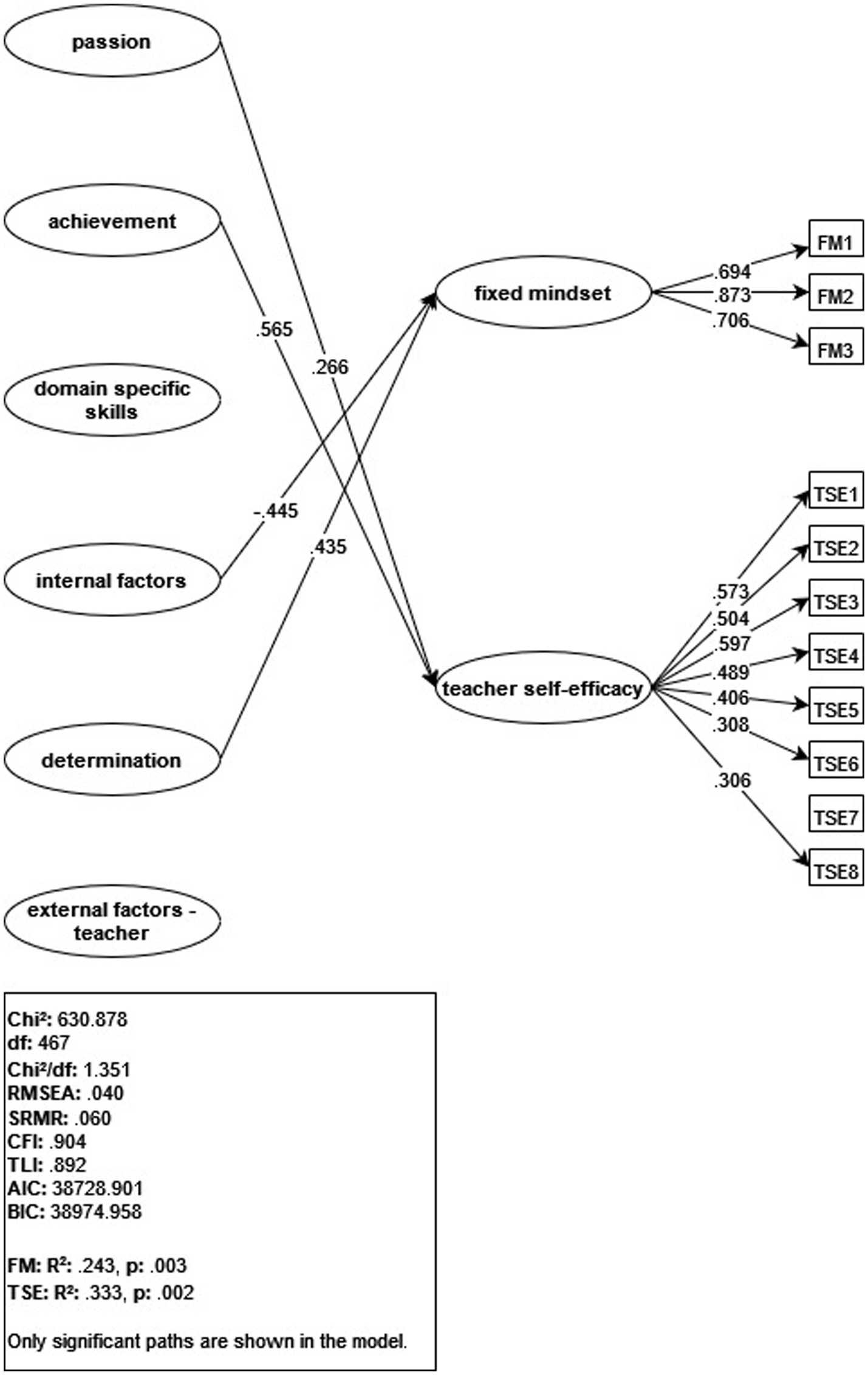

In the structural equation model, student teachers’ talent beliefs in the domain of verbal giftedness predicted their fixed mindset and self-efficacy (χ2/df = 1.351; RMSEA = 0.040; SRMR = 0.060; CFI = 0.904; TLI = 0.892), explaining 24% of the variance of student teachers’ growth mindset (R2 = 0.243, p = 0.003) and 33% of their self-efficacy (R2 = 0.33, p = 0.002). However, only two of the verbal talent beliefs factors were found to be predictive in a statistically significant way for each of the criteria, namely, internal factors (β = −0.445, p = 0.007) and determination (β = 0.435, p = 0.000) for the student teachers’ fixed mindset and passion (β = 0.266, p = 0.024) and achievement (β = 0.565, p = 0.016) for their self-efficacy. The β-coefficients speak in favor of medium effects. The structural equation model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Structural equation model of teachers’ talent beliefs about verbal giftedness predicting their fixed mindset and teacher self-efficacy.

5 Discussion

In this study, we developed and tested the questionnaire on talent beliefs in the domain of verbal giftedness, which is now currently available for future research. The scales and items are provided in the Supplementary material. In addition to the German version, the English version of the questionnaire, which has not yet been tested, is attached. We recommend that the questionnaire be validated in other languages. The results of our research show that talent beliefs and growth mindsets share similarities, albeit being two different constructs. We found that student teachers’ talent beliefs about verbal giftedness can be measured using an adapted questionnaire previously developed and applied to measure teachers’ talent beliefs about mathematics (Rogl, 2022), with one additional factor.

However, the questionnaire has only been tested with student teachers, although we assume that it also fits in-service teachers, analogous to the mathematics questionnaire (Rogl, 2022). At this point in time, we are not able to generalize the results to in-service teachers. However, we will test generalizability in a currently running study with in-service teachers. Another limiting factor of the results is that all measures are self-report, which inherently are prone to socially desirable answers. Thus, we cannot exclude that student teachers responded according to what they consider as socially desirable. Nonetheless, self-reports seem to be the method of choice to measure beliefs. In terms of limitations, the teacher self-efficacy scale shows an internal consistency that is acceptable but can also be seen as questionable with α = 0.61. Since we use the established and tested scale from Schwarzer and Schmitz (2002), for which the authors report internal consistencies between α = 0.76 and α = 0.82 for different points of measurement, we decided to use it for analyses regardless.

One of the major contributions of this study is the demonstration that teachers’ beliefs about verbal giftedness are multidimensional. Unlike previous studies of talent beliefs, which have often focused on bipolar models that distinguish between beliefs about stability and innateness versus beliefs about learnability, our six-factor model is consistent with theoretical conceptions of giftedness and talent that encompass multiple dimensions. Due to the multidimensional nature of teachers’ beliefs about verbal giftedness, the instrument covers distinct aspects of the construct which in turn predict mindset and self-efficacy in different strengths.

These findings may prompt future research on various aspects of this topic. It would be interesting to investigate whether teachers’ talent beliefs are domain-specific; that is, whether they differ intra-individually depending on the domain, as well as determine whether verbal talent beliefs differ between student teachers and in-service teachers. As shown in Rogl (2022), some dimensions of teachers’ talent beliefs in mathematics predict cognitively activating teaching. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to determine whether teachers’ talent beliefs in the verbal giftedness domain are predictive of classroom performance.

Future research results could provide further insights and have important implications for teacher training and professionalization. An essential aspect concerning teacher education would be that by examining and reflecting on one’s own beliefs about giftedness, misconceptions can be avoided and verbally gifted students can be supported appropriately through suitable tasks that foster giftedness (e.g., verbal giftedness-promoting manuals in Austria: Austrian Research and Support Center for Gifted and Talented (ÖZBF), 2022; Schmid et al., 2023). In addition, our questionnaire is intended to raise awareness of the verbal domain. Ideally, good science communication can also sensitize policy makers to the necessity of especially supporting verbally gifted students in future educational projects.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because data protection regulations. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2lsa2Uucm9nbEBwaHNhbHpidXJnLmF0.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because it was a voluntary questionnaire survey without discriminatory or questionable content. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. To optimize the participation in the questionnaire survey book vouchers (value 250 Euro) were raffled off. The vouchers and the publication are financed by the project budget of the Austrian Research and Support Center for Gifted and Talented (ÖZBF) (nationwide focus at the University of education Salzburg, Austria).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1513424/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Ziegler et al. (2013) provide information on the well-established history of gifted education in German-speaking Europe. A detailed overview of the specific processes and educational pathways, particularly in Austria, can be found in the work of Hinterplattner and Sabitzer (2022); Jöstl et al. (2023).

References

Asbury, K., Roloff, J., Carstensen, B., Guill, K., and Klusmann, U. (2023). Investigating preservice teachers’ field-specific ability beliefs: do they believe innate talent is essential for success in their subject? Teach. Teach. Educ. 136:104367. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104367

Austrian Research and Support Center for Gifted and Talented (ÖZBF) (Ed.) (2022). Wege in der Begabungsförderung im Fach Englisch. Begabungsförderliche Methoden im Englischunterricht. 2nd ed. Salzburg: Pädagogische Hochschule Salzburg Stefan Zweig.

Baudson, T. G. (2016). The mad genius stereotype: still alive and well. Front. Psychol. 7, 1–20. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00368

Baudson, T. G., and Preckel, F. (2013). Teachers’ implicit personality theories about the gifted: an experimental approach. Sch. Psychol. Q. 28, 37–46. doi: 10.1037/spq0000011

Baudson, T. G., and Preckel, F. (2016). Teachers’ conceptions of gifted and average-ability students on achievement-relevant dimensions. Gift. Child Q. 60, 212–225. doi: 10.1177/0016986216647115

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2006). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Z. Erzieh. 9, 469–520. doi: 10.1007/s11618-006-0165-2

Bertschi-Kaufmann, A., and Gyssler, A. (2014). “Sprachbegabung, Lesekompetenz und ihre Förderung in der Schulpraxis” in Handbuch Entwicklungspsychologie des Talents. ed. M. Stamm (Bern: Hans Huber), 487–496.

Bigelow, F. J., Clark, G. M., Lum, J. A. G., and Enticott, P. G. (2021). The mediating effect of language on the development of cognitive and affective theory of mind. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 209:105158. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105158

Blömeke, S., Kaiser, G., and Lehmann, R. (Eds.) (2008a). Professionelle Kompetenz angehender Lehrerinnen und Lehrer. Wissen, Überzeugungen und Lerngelegenheiten deutscher Mathematikstudierender und -referendare – Erste Ergebnisse zur Wirksamkeit der Lehrerausbildung. Münster: Waxmann.

Blömeke, S., Müller, C., Felbrich, A., and Kaiser, G. (2008b). “Epistemologische Überzeugungen in Mathematik” in Professionelle Kompetenz angehender Lehrerinnen und Lehrer. Wissen, Überzeugungen und Lerngelegenheiten deutscher Mathematikstudierender und -referendare – Erste Ergebnisse zur Wirksamkeit der Lehrerausbildung. eds. S. Blömeke, G. Kaiser, and R. Lehmann (Münster: Waxmann), 219–246.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press.

Calderhead, J. (1996). “Teachers: beliefs and knowledge” in Handbook of research on educational psychology. eds. D. Berliner and R. Calfee (New York: Macmillan), 709–725.

Carman, C. A. (2011). Stereotypes of giftedness in current and future educators. J. Educ. Gift. 34, 790–812. doi: 10.1177/0162353211417340

Carroll, J. B. (1990). “Cognitive abilities in foreign language aptitude: then and now” in Language in education: Theory and practice 74. Language aptitude reconsidered. eds. T. S. Parry and C. W. Stansfield (Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice Hall), 11–27.

Carroll, J. B., and Sapon, S. M. (Eds.) (1959). Modern language aptitude test. San Antonio, TX, US: Psychological Corporation.

Dai, D. Y., Swanson, J. A., and Cheng, H. (2011). State of research on giftedness and gifted education: a survey of empirical studies published during 1998–2010 (April). Gift. Child Q. 55, 126–138. doi: 10.1177/0016986210397831

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 41, 1040–1048. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040

Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: their role in motivation, personality and development. New York: Psychology Press.

Dweck, C. S., and Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95, 256–273. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Farkas, K. (2014). “Fachdidaktik Deutsch Teil I: Sprachdidaktik: Auf der Suche nach Sprachgenies – und den besten Lehrpersonen” in Professionelle Begabtenförderung: Fachdidaktik und Begabtenförderung ed. (iPEGE – International Panel of Experts for Gifted Education), (Salzburg: ÖZBF), 77–99.

Fives, H., and Buehl, M. M. (2012). “Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: what are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us?” in APA educational psychology handbook, Vol 2: individual differences and cultural and contextual factors. eds. K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, and M. Zeidner (Washington, D.C. American Psychological Association), 471–499.

Gagné, F. (2005). “From gifts to talents: the DMGT as a developmental model” in Conceptions of giftedness. eds. R. J. Sternberg and J. E. Davidson (New York: Cambridge University Press), 98–119.

Gagné, F. (2018). Attitudes toward gifted education: retrospective and prospective update. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 60, 403–428.

Goldin, G. A., Rösken, B., and Törner, G. (2009). “Beliefs – no longer a hidden variable in mathematical teaching and learning process” in Beliefs and attitudes in mathematics education. New research results. eds. J. Maaß and W. Schlöglmann (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 1–18.

Hany, E. A. (1997). Modeling Teachers' judgment of giftedness: a methodological inquiry of biased judgment. High Abil. Stud. 8, 159–178. doi: 10.1080/1359813970080203

Heller, K. A., Finsterwald, M., and Ziegler, A. (2001). Implicit theories of German mathematics and physics teachers on gender specific giftedness and motivation. Psychol. Beitr. 43, 172–189.

Heller, K. A., Perleth, C., and Lim, T. K. (2005). “The Munich model of giftedness designed to identify and promote gifted students” in Conceptions of giftedness. eds. R. J. Sternberg and J. E. Davidson (New York: Cambridge University Press), 147–170.

Helmke, A. (2010). “Unterrichtsqualität und Lehrerprofessionalität” in Diagnose, Evaluation und Verbesserung des Unterrichts (Seelze: Klett-Kallmeyer).

Heyder, A., Steinmayr, R., and Kessels, U. (2019). Do teachers’ beliefs about math aptitude and brilliance explain gender differences in children’s math ability self-concept? Front. Educ. 4:34. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00034

Heyder, A., Weidinger, A. F., Cimpian, A., and Steinmayr, R. (2020). Teachers’ belief that math requires innate ability predicts lower intrinsic motivation among low-achieving students. Learn Instr. 65, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101220

Hinterplattner, S., and Sabitzer, B. (2022). “Potentials and challenges in new honors programs: honors education in Austria” in Honors education around the world. ed. G. Harper (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholar Publishing), 122–128.

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jöstl, G., Hinterplattner, S., and Rogl, S. (2023). Talent development programs for secondary schools: implementation and evaluation of a model school. Educ. Sci. 13:1172. doi: 10.3390/educsci13121172

Klieme, E., and Rakoczy, K. (2008). Empirische Unterrichtsforschung und Fachdidaktik. Outcome-orientierte Messung und Prozessqualität des Unterrichts. Z. Pädagog. 54, 222–237. doi: 10.25656/01:4348

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

König, J. (Ed.) (2012). Teachers' pedagogical beliefs. Definition and operationalisation, connections to knowledge and performance, development and change. Münster: Waxmann.

Laine, S. (2010). The Finnish public discussion of giftedness and gifted children. High Abil. Stud. 21, 63–76. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2010.488092

Laine, S., Kuusisto, E., and Tirri, K. (2016). Finnish teachers’ conceptions of giftedness. J. Educ. Gift. 39, 151–167. doi: 10.1177/0162353216640936

Laschke, C., and Schmotz, C. (2013). “Erfassung der Überzeugungen” in Teacher education and development study: Learning to teach mathematics (TEDS–M): Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente. eds. C. Laschke and S. Blömeke (Münster: Waxmann), 324–334.

Laudenberg, B., and Spiegel, C. (2020). Förderung sprachlicher Expertise am Beispiel des Schreibens und Kommunizierens Lehren & Lernen (Baden-Württemberg: Zeitschrift für Schule und Innovation aus). 8/9:22–26.

Makel, M. C., Snyder, K. E., Thomas, C., Malone, P. S., and Putallaz, M. (2015). Gifted students implicit beliefs about intelligence and giftedness. Gift. Child Q. 59, 203–212. doi: 10.1177/0016986215599057

Matheis, S., Kronborg, L., Schmitt, M., and Preckel, F. (2017). Threat or challenge? Teacher beliefs about gifted students and their relationship to teacher motivation. Gift. Talented Int. 32, 134–160. doi: 10.1080/15332276.2018.1537685

McCoach, D. B., and Siegle, D. (2007). What predicts Teachers' attitudes toward the gifted? Gift. Child Q. 51, 246–254. doi: 10.1177/0016986207302719

Moon, T. R., and Brighton, C. M. (2008). Primary Teachers' conceptions of giftedness. J. Educ. Gift. 31, 447–480. doi: 10.4219/jeg-2008-793

Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Subotnik, R. F., and Worrell, F. C. (2015). Conceptualizations of giftedness and the development of talent: implications for counselors. J. Couns. Dev. 93, 143–152. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00190.x

Preckel, F., Baudson, T. G., Krolak-Schwerdt, S., and Glock, S. (2015). Gifted and maladjusted? Implicit attitudes and automatic associations related to gifted children. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52, 1160–1184. doi: 10.3102/0002831215596413

Rammstedt, B., Grüning, D. J., and Lechner, C. M. (2022). Measuring growth mindset: validation of a three-item and a single-item scale in adolescents and adults. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 40, 84–95. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000735

Research Data Center at the Institute for Quality Development in Education (2019). Stereotype Threat: Skalenhandbuch zur Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente. Berlin: IQB - Institute for Educational Quality Improvement.

Reusser, K., and Pauli, C. (2010). “Unterrichtsgestaltung und Unterrichtsqualität – Ergebnisse einer internationalen und schweizerischen Videostudie zum Mathematikunterricht: Einleitung und Überblick” in Unterrichtsgestaltung und Unterrichtsqualität: Ergebnisse einer internationalen und schweizerischen Videostudie zum Mathematikunterricht. eds. K. Reusser, C. Pauli, and M. Waldis (Münster: Waxmann), 9–32.

Reusser, K., and Pauli, C. (2014). “Berufsbezogene Überzeugungen von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern” in Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf. eds. E. Terhart, H. Bennewitz, and M. Rothland (Münster: Waxmann), 642–661.

Rogl, S. (2022). Begabungsüberzeugungen und ihr Einfluss auf kognitiv herausfordernden Unterricht. Münster: Waxmann.

Russell, J. L. (2018). High school teachers’ perceptions of giftedness, gifted education, and talent development. J. Adv. Acad. 29, 275–303. doi: 10.1177/1932202X18775658

Schmid, F., Bögl, E., Gürtler, B., Schwendinger, S., Kempter, U., Müller, M., et al. (2023). “Wege in der Begabungsförderung im Fach Deutsch” in Begabungsförderliche Methoden im Deutschunterricht. 2nd ed (Salzburg: Pädagogische Hochschule Salzburg Stefan Zweig).

Schwarzer, R., and Schmitz, G. S. (2002). “WirkLehr: Skala Lehrer-Selbstwirksamkeit [Verfahrensdokumentation, Autorenbeschreibung und Fragebogen]” in Open Test Archive (Trier: Leibniz-Institut für Psychologie, ZPID).

Steinmann, S., and Oser, F. (2012). Prägen Lehrerausbildende die Beliefs der angehenden Primarlehrpersonen? Shared Beliefs als Wirkungsgröße in der Lehrerausbildung. Z. Pädagog. 58, 441–459. doi: 10.25656/01:10388

Sternberg, R. J., and Davidson, J. E. (Eds.) (2005). Conceptions of giftedness. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sternberg, R. J., and Kaufman, S. B. (2018). “Theories and conceptions of giftedness” in Handbook of giftedness in children: Psychoeducational theory, research, and best practices. ed. S. I. Pfeiffer (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 29–47.

Tatto, M. T., Schwille, J., Senk, S. L., Ingvarson, L., Peck, R., and Rowley, G. (2008). Teacher education and development study in mathematics (TEDS-M): Policy, practice, and readiness to teach primary and secondary mathematics: Conceptual framework. East Lansing, MI: Teacher Education and Development International Study Center, College of Education, Michigan State University.

Terhart, E., Bennewitz, H., and Rothland, M. (Eds.) (2014). Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf. Münster: Waxmann.

Tofel-Grehl, C., and Callahan, C. M. (2017). STEM high schools teachers’ belief regarding STEM student giftedness. Gift. Child Q. 61, 40–51. doi: 10.1177/0016986216673712

Troxclair, D. A. (2013). Preservice teacher attitudes toward giftedness. Roeper Rev. 35, 58–64. doi: 10.1080/02783193.2013.740603

Wagner, T. (2014). “Fachdidaktik Englisch” in Professionelle Begabtenförderung: Fachdidaktik und Begabtenförderung ed. iPEGE – International Panel of Experts for Gifted Education (Salzburg: ÖZBF), 111–129.

Wen, Z., and Skehan, P. (2011). A new perspective on foreign language aptitude research: building and supporting a case for ‘working memory as language aptitude’. Ilha Do Desterro J. English Lang. Lit. Eng. Cult. Stud. 15–44. doi: 10.5007/2175-8026.2011n60p015

Ziegler, A., and Stöger, H. (2010). Research on a modified framework of implicit personality theories. Learn. Individ. Differ. 20, 318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2010.01.007

Keywords: talent, verbal, giftedness, mindset, teachers’ beliefs, instrument development, teachers’ talent beliefs, verbal giftedness

Citation: Rogl S, Hamader KC and Klug J (2025) Teachers’ talent beliefs in the domain of verbal giftedness—the questionnaire. Front. Educ. 10:1513424. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1513424

Edited by:

Laura Sara Agrati, University of Bergamo, ItalyReviewed by:

Sergei Abramovich, State University of New York at Potsdam, United StatesAlberto Rocha, Higher Institute of Educational Sciences of the Douro, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Rogl, Hamader and Klug. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Silke Rogl, c2lsa2Uucm9nbEBwaHNhbHpidXJnLmF0

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Silke Rogl

Silke Rogl Kathrin Claudia Hamader

Kathrin Claudia Hamader Julia Klug

Julia Klug