- School of Early Childhood Education, Faculty of Education, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece

Introduction: Although peer reflection activities are a frequent choice in teacher education, inconsistencies emerge in existing literature regarding the impact of peer interaction on reflection, the design of peer reflection activities, and the visibility of the social nature of reflection. Considering those inconsistencies, the present review seeks convergence in conceptualizing the social dimension of reflection. It aims to examine how reflection is presented in relation to social interaction in the introduction of research papers that study peer reflection activities in initial teacher education.

Methods: Firstly, we employed a systematic review methodology through which 98 relevant research papers were selected. Then we applied the grounded theory literature review method to seek common themes emerging in the documents of the sample.

Results: Results indicate sociality as an inherent characteristic of the reflection process substantiated in reflection definitions and social learning theoretical frameworks, and at the same time, as an acquired characteristic - a methodological choice to enhance cognitive and emotional processes of reflection. Findings also indicate that the social dimension of reflection is a fluid characteristic, constantly evolving in alignment with the social turn in learning and technology.

Discussion: The point of convergence among researchers is not the acceptance of a dominant direction in conceptualizing of the social dimension of reflection, but rather an implicit acceptance of the "fluidity" of reflection diverse approaches. Operating along a continuum between being "social by choice" and "social by nature", and evolving in response to sociocultural changes, reflection appears to overcome the absence of a consolidated theory framing its social dimension, and to be creatively founded on researchers' need to integrate it with contemporary tools and learning approaches.

1 Introduction

The development of the reflective teacher, who questions and reframes their beliefs and practices, is widely recognized as a critical goal in contemporary teacher education agendas (Rodgers, 2020; Korthagen and Nuijten, 2022). Nowadays, teacher reflection is conceptualized as both an individual and a social process (Sulzer and Dunn, 2019; Hommel et al., 2023) and socially mediated reflection activities that engage student teachers in sharing, negotiating, and co-constructing meanings, are highly recommended (Farrell, 2018). While the individual nature of reflection appeared to dominate the literature for a long time, Beauchamp (2006) argued that a position in favor of the individual or the social nature of reflection is not prolific, as both types are evident and useful. A blend of the two types could serve better the needs. of learners as both individual and social systems are concurrent and interrelated in learning (Volet et al., 2009). Adopting this integrative perspective, we aim to illuminate some aspects of the less visible side of the coin: the social dimension of reflection in teacher education.

According to Collin and Karsenti (2011), the social dimension of teachers' reflective practice emerges with the presence of an “other”. The “other” could be met in the face of peers, mentors, teacher educators and in-service teachers who interact with student teachers (Radović et al., 2021). In the last two decades the role of the experienced “other” has been revisited and expanded beyond the traditional relationship between students and teacher educators or mentors (Le Cornu, 2005). As a result, the potential of peers' reflective interactions has gained considerable attention in teacher education since peers share common experiences, interests and goals (Le Cornu, 2010). Promising prospects of this kind of interactions are also confirmed by empirical data (Smith, 2002; Erdemir and Yeşilçinar, 2021; Jiang and Zheng, 2021; Ahmad, 2024). At the same time, however, some research findings are concerning. Delving deeper into the relevant literature, inconsistencies emerge regarding (i) the impact of peer interaction on students' reflection, (ii) the design of peer reflection activities, and (iii) the perceptions held by researchers on the nature of reflection. Contradictory observations seem to arise repeatedly in these three areas, as discussed in the next section. The conceptual and practical challenges posed by these observations for comprehensively understanding the social nature of teachers' reflection served as the impetus for our study.

1.1 Peer reflection in teacher education: some inconsistencies worth exploring

1.1.1 Promising but also concerning research findings

Empirical research findings demonstrate the enriching role of peer interaction in student teachers' reflection. More specifically, engagement in peer group activities facilitates the progression from the description and the evaluation of an experience to its deconstruction and reframing (Cavanagh and McMaster, 2015; Sydnor et al., 2020). In addition, interaction among peers expands the breadth of topics taken into consideration while reflecting (Shin, 2021), supports the bridging of the theory and practice gap (Harford et al., 2010) and contributes to the reconsideration of their beliefs on teaching and learning (Layen and Hattingh, 2020; Miller et al., 2021). Student teachers themselves report that peers help them to focus on useful directions, gain new perspectives and cherish the emotionally secure places of sharing and the mutual support in which they interact (Crichton and Valdera Gil, 2015; Behizadeh et al., 2019; Hansen and Mendzheritskaya, 2024).

On the other hand, some studies indicate that peer interaction influences the reflection process in ways that do not always align with its anticipated benefits or are fully understood. Even when social interaction enhances reflection, student teachers rarely reach the highest levels of reflection (Wade et al., 2008). In some cases, collaboration may even seem to distract student teachers from the reflective process (Epler et al., 2013). Student teachers may experience joint activities in contradictory ways: they perceive peer interaction as beneficial, but this is not reflected in their practices, as they don't always share their thoughts with others (Elhussain and Khojah, 2020). Similarly, while they note that peers contribute to their reflective thinking, they raise concerns about the time they need to devote to reflective discussions, the quality of the feedback that a peer can provide and the feeling of exposure in front of others (Ratminingsih et al., 2017; Erdemir and Yeşilçinar, 2021).

1.1.2 A commonly implemented but not theoretically well-supported method

The literature suggests that many teacher educators favor socially mediated activities as a methodological approach to engage student teachers in reflective practice. These activities commonly manifest as critical friends offering valuable feedback to each other (Gedera and Fester, 2023; Näykki et al., 2022), groups reflecting together on the co-construction of artifacts (Ekin et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024), or broader learning communities where peers exchange experiences, thoughts, emotions, and support (Deng and Yuen, 2011; Rettig, 2013; Radović et al., 2023). However, as some researchers have observed, there is often an absence of conceptual framing for these methodological choices with consequences on the quality of the reflection. For example, in a critical review, Roskos et al. (2001) observed that, despite the prevalence of social interaction in reflective activities within general teacher education (utilized in ~70% of the research reviewed), a very small percentage of studies substantiated their choice with theoretical evidence. Another, more recent observation that can be drawn from the literature is that the frameworks and models available appear to be prescriptive and stem from distinct theoretical origins and perspectives of reflection, which often results in a wide range of unconnected approaches (Clarà et al., 2019; Watanabe and Tajeddin, 2022), rather than approaches that can converge to crystalize the essence of the social dimension of reflection.

1.1.3 The social side of reflection is seen but at the same time “unseen”

Considering the wide acceptance of socially mediated reflection experiences in teacher education programs, one might anticipate that reflection is widely understood as a social process. Nevertheless, some researchers observe a persistent conception of reflection as a solitary process occurring within individuals' minds (Baer, 2022; Yang and Choi, 2023). Furthermore, empirical research on teachers' social reflection activities is growing unevenly in comparison to the theoretical literature that addresses the social dimension of reflection. Collin and Karsenti (2011) note that in the lack of such theoretical literature, i.e., theoretical models that consider social dimensions of teachers' reflection, the impression that reflection is an individual process persists. Much of the criticism directed toward reflection centers on its conceptualization through the lens of individual cognitive processing, which consequently limits a comprehensive understanding of reflective practice. For example, the emphasis on reflection as a lonely, introspective action, overlooks the vital role “others” play in teachers' professional growth (Carlson, 2019). Moreover, activities that encourage only inwardly driven reflection processes, may lead teachers to process the problems faced with an added emotional bargain as personal failures that other teachers do not encounter and limit perspectives toward the social context that shapes classroom realities (Segall and Gaudelli, 2007). In sum, perceiving reflection as an individual process seems inconsistent with the contemporary view of reflection and with the broad application of socially mediated reflection activities in teacher education.

1.2 Rationale of the study and research question

The above inconsistencies and gaps identified in the literature set significant conceptual and practical challenges to fully understanding and implementing socially mediated reflection activities in teacher education. Acknowledging this issue, the literature stresses the need for further research that will illuminate the points of convergence in the conceptualization of the social dimension of reflection (Collin and Karsenti, 2011; Clarà et al., 2019; Yang and Choi, 2023). Toward this direction, the study presented here aims to extend the understanding of the social nature of reflection through an interpretative approach that inductively explores how researchers in the field describe reflection in association with interaction. More specifically, the following research question was addressed:

• How is reflection presented in relation to social interaction, in research papers that study socially mediated reflection activities in initial teacher education?

2 Methods

To examine how researchers in the field of teacher education perceive reflection in relation to interaction, we employed two distinct and complementary methodologies: the Systematic Literature Review method to systematically select peer reflection research papers, and the Grounded Theory Literature Review Method to analyze them inductively. Grounded theory has been recently combined with systematic reviews. This emerged from researchers' need to employ systematic reviews to study phenomena through exploratory methodologies, rather than confirmatory ones, as traditionally occurs in systematic review methodologies (Luca et al., 2022; Clark et al., 2023). Recognizing this need, Wolfswinkel et al. (2013) developed the Grounded Theory Literature Review Method (GTLR), which we adopted in the present study. It systematically integrates the two methods and their benefits, and it is proposed for studies aiming to create new interpretative models of a phenomenon (ibid.). In addition, we employed the Systematic Literature Review Method to ensure a rigorous, comprehensive and transparent selection of papers studying socially mediated reflection activities in initial teacher education. Toward this direction, we adhered to the guidelines suggested for mixed methods systematic reviews (Lizarondo et al., 2020) of the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris and Munn, 2020). In the following sections, we provide a detailed description of the abovementioned data selection and analysis processes.

2.1 Inclusion/exclusion criteria

2.1.1 Participants: student teachers

The sample of the publications included was predefined to be student teachers enrolled in initial teacher education programs. We considered the initial stage of the teacher education continuum to be crucial, as it lays the foundations for the professional identity and skills that future teachers will develop. Additionally, this stage is where a culture of continuous development regarding teachers' reflective thinking can be significantly reinforced (Collin et al., 2013). The challenge was to identify what constitutes initial teacher education in different countries, periods, educational systems, and socio-cultural contexts. Delving into the relevant literature we identified and included different forms of initial teacher education, avoiding limiting our sample to more common terms like student teachers, preservice teachers, or undergraduate teachers. For example, in some initial teacher education programs student teachers are trained in schools (Musset, 2010) and, are characterized as “in-service teachers” in some of the publications we encountered. We focused on the program type, and not the terms describing the student teachers in the papers. If the type of teacher training program was not clear in the full text, we also checked the official site of the programs to see their entry requirements. The program had to be the entry point to the profession for its participants to be characterized as an initial education program (Musset, 2010). Therefore, we rejected (a) induction programs which were designed to assist new teachers in transitioning into their professional roles, except cases where the induction program was integrated into the initial teacher education program, and (b) professional development programs targeting certified teachers e.g., masters or seminars for certified teachers.

2.1.2 Phenomenon of interest: reflection

The sample also included publications that focused on the reflection of student teachers. The following criteria were used to ensure this requirement: (a) reflection had to be the main object of the publication, and (b) publications had to describe in detail organized reflection activities involving student teachers.

2.1.3 Context: interaction with peers

A prerequisite for the eligibility of publications was that the reflective activities described should involve interaction with peers. Publications were rejected if student teachers interacted with significant others who were not their peers (e.g., teacher educators, supervisors, mentors, and members of the school community where they conducted their practicum).

2.1.4 Publication type: peer-reviewed empirical research

Regarding the type of publications, eligible were considered primary empirical research studies with qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methodological design. Limiting the type of publications in empirical research (excluding theoretical articles, opinion papers, etc.) has the benefit of resulting in comparable articles in terms of their structure. More specifically, the sections of the text from which the data will derive (in this case “introduction”, “literature review” and “conceptual/theoretical framework”) were easy to locate and compare. Furthermore, the publications were restricted to peer-reviewed research, in order to access articles of comparable quality. Lastly, publications with full text in a language other than English were rejected due to the authors' inability to translate them. Although the selection of only English-language articles may increase the risk of bias, studies have shown that including articles in other languages does not significantly affect the results of a systematic review (Moher et al., 2003; Morrison et al., 2012).

2.2 Critical appraisal

For critical appraisal, the methodological guidelines of Hong and Pluye (2019) were followed. The evaluation criteria they proposed apply to publications with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed research designs, aligning with the variety of research designs we included in this review. Following their guidelines, we considered three aspects of quality.

• Reporting quality. It concerns the extent to which the publication provides sufficient and accurate information that allows for transparency and understanding of the research processes presented.

• Methodological quality. It assesses the validity and reliability of the articles under evaluation. For the assessment of methodological quality, we used the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) proposed by the same research team (Hong et al., 2018), which provides five evaluation criteria adapted for different research designs.

• Conceptual quality. It relates to the clarity and depth with which a concept is developed, allowing for a rich and deep understanding of the phenomenon of interest. It is a significant quality criterion in conceptualization reviews. The following criteria were formulated: (i) the concept of reflection should be thoroughly described, (ii) the relationship between reflection and social interaction should be described in a way that allows for deeper understanding, and (iii) socially mediated reflection should be a central subject of the publication.

2.3 Search strategy and data sources

The present systematic review is located at the intersection of three distinct research domains: reflection, initial teacher education, and social interaction.

• Reflection. To identify terms relevant to reflection, pilot searches were conducted in bibliographic databases with the terms reflect, reflection, reflective, and reflectivity. In the results of these searches, additional terms expressing reflection were identified: reflexive and reflexivity. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the relevant literature, all six terms were used as synonymous keywords in the final search.

• Initial teacher education. During pilot searches, we observed that initial teacher education was also described as “preservice teacher education”, “prospective teacher education” or just “teacher education”. The term “teacher education” appeared to encompass all the various types of terms observed. Therefore, it was selected as the search term that would ensure the comprehensive coverage of publications related to initial teacher education.

• Social interaction. The pilot searches performed resulted in a wide variety of terms denoting social interaction. Indicative examples were interaction, critical friends, conversation, dialogue, mentoring, group, collaboration, pairs, and socialization. Considering the wide variety of different terms that we came across, and the difficulty to reliably predefine all the relevant terms, we decided not to use any specific search term concerning social interaction. In later stages, during screening, full-text assessment and critical appraisal assessment, we applied specific criteria so as to include in the final sample only reflection activities that incorporated social interaction. This methodological choice increased the number of the search results but reduced the risk to exclude relevant articles that used more rare terms to describe social interaction.

In sum, two main terms were used in the searching process: “reflection” (reflect OR reflection OR reflective OR reflectivity OR reflexive OR reflexivity) AND “teacher education”. The two terms were pre-specified to be both included in the title or the abstract or the keywords of the publication. Furthermore, the year 1983 was selected as the starting point for the search, because it was the year when Schön's book “The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action” (Schön, 1983) was published. This book can be said to have sparked the interest in the “reflective teacher” and has inspired the infusion of reflection goals and activities in teacher education (Rodgers and Laboskey, 2016). Apart from making reflection more accessible in teacher education, the book also introduced the social dimension of reflection in the teaching profession and the key role of peers: “The teacher's isolation in her classroom works against reflection-in-action. She needs. to communicate her private puzzles and insights, to test them against the views of her peers” (Schön, 1983, p. 333).

Regarding the data sources explored, we used interdisciplinary bibliographic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect), and a database specializing in education science (ERIC). Pilot searches in each of the four databases were performed, to detect the special characteristics of their search engines and then develop the final search command for each database. This procedure was performed with the assistance of a librarian to increase the validity of the process. The final search was conducted in April of 2022, resulting in a total of 24.318 publications deriving from the four databases.

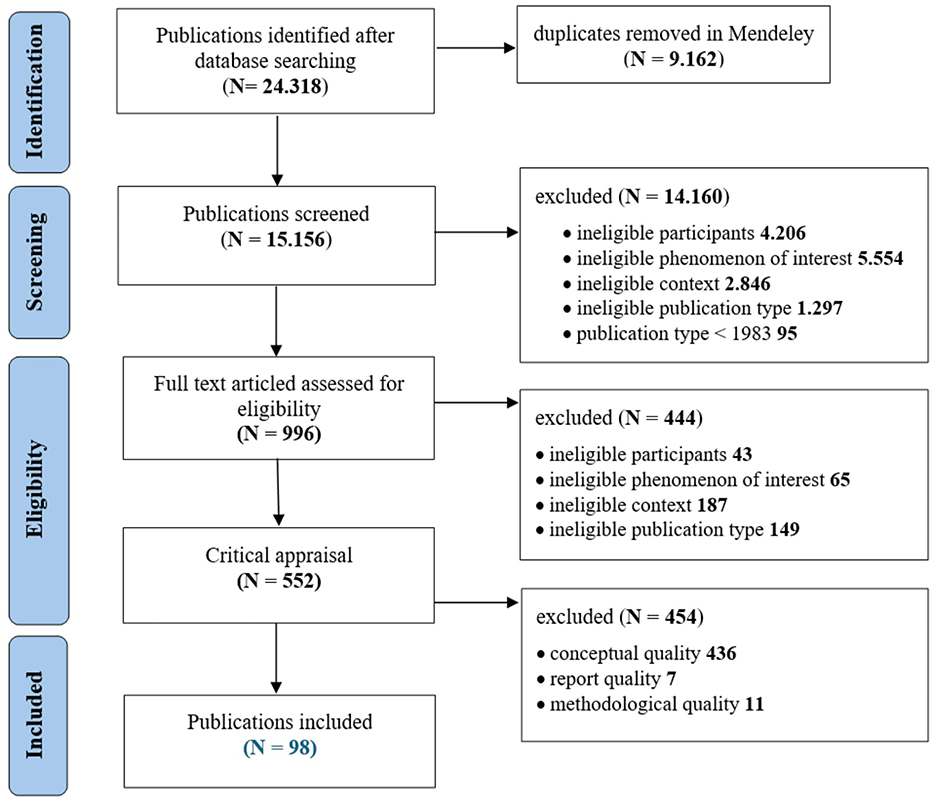

2.4 Study selection process

The 24,318 publications underwent a step-by-step study selection process, depicted in the flowchart (Figure 1). All the references were inserted into the Mendeley reference management software, where duplicates were removed, reducing the publications to 15,156. In the next stage, titles and abstracts were screened to determine if inclusion criteria were met. During this phase, if no exclusion criterion was apparent in the title or abstract, the publication was accepted for a thorough review in the next stage. This methodological choice aimed to ensure that relevant publications were not rejected due to the absence of critical information in the title/abstract. After completing the screening stage, 14,160 publications were excluded, leaving 996 for full-text eligibility evaluation. Of these, 552 publications proceeded to critical appraisal. The majority were excluded based on conceptual quality assessment, resulting in a final sample of 98 publications for our systematic review.

Figure 1. Prisma flowchart diagram of the study selection process (Moher et al., 2010). Flowchart diagram depicting the step-by-step study selection process of the present systematic review: beginning with the identification of studies in bibliographical databases, followed by successive evaluations of the identified studies, resulting in 98 selected publications.

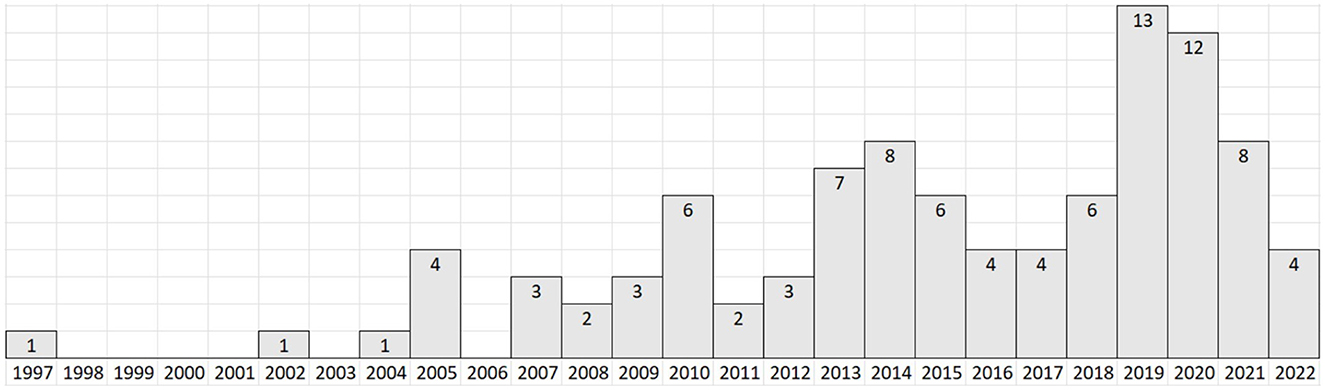

2.5 Sample characteristics

The sample comprised ninety-eight (n = 98) research papers. A complete reference list of the 98 selected publications can be found in the Supplementary material “Reference list of the studies under review”. Most research designs were qualitative (n = 48) and mixed (n = 47), while only three (n = 3) studies employed a quantitative research design. In almost half of the papers examined (46%), participants were less than 20 student teachers, while very few studies (9%) included more than 100 participants. The most popular scientific journals for the publication of the sample papers were the “Teaching and Teacher Education” (n = 8), and the “Reflective Practice” (n = 5). An interesting characteristic of the sample was that even though the search was conducted from 1983 to 2022, the eligible studies expanded in the last two decades (2002–2022), except for a paper published in 1997. Figure 2 depicts the number of studies published per year. As demonstrated below, the publications seem to have doubled over a period of 5 years (2001-2005: 6 studies, 2006–2010: 14 studies, 2011–2015: 26 studies, 2016–2020: 39 studies). This could be attributed to the increasing interest in the specific topic, as well as the increasing number of scientific publications over the years.

Figure 2. Papers of the sample per publication year. Bar graph illustrating the annual distribution of the 98 studies included in this systematic review, showing the total number of publications per year from 1997 to 2022.

2.6 Data extraction and analysis

The data for analysis were traced in the sections of Introduction, Literature Review, and Theoretical/Conceptual Framework of the 98 publications, where researchers presented their rationale and reasoning for studying socially mediated reflection activities. The first author identified and marked the sentences and phrases that described any kind of relationship between reflection and social interaction in the 98 eligible full-text documents imported into Mendeley Reference Management Software. The identified text units of analysis were subsequently transported in a co-authored Google sheet to which both authors had access. Using this tool, we analyzed the data manually, following the guidelines proposed in the Grounded Theory Literature Review Method (Wolfswinkel et al., 2013):

• Open Coding: During open coding, the units of analysis identified in each publication were extracted and reviewed multiple times so as to identify patterns among them and to form the initial codes.

• Axial Coding: The initial codes were organized into broader groups, according to their semantic proximity.

• Selective Coding: Finally, the categories of axial coding were semantically connected to form the main “theory”, the central position of the study, while simultaneously explaining the connections among the distinct categories. In this way, the main “theory” on the relationship between reflection and social interaction can acquire more layers of analysis and move beyond descriptive observations, to more hermeneutical approaches.

The categories formed during open, axial and selective coding, along with representative quotes for the categories of open coding, are displayed in the Supplementary material “Coding process and representative quotes”. The authors collaborated to apply the grounded theory methodology. Initially, one author performed the open coding, identifying key concepts within the data. Following this, both authors engaged in an iterative discussion to review, negotiate, refine, and consolidate the codes, ensuring a shared understanding and coherence in the coding scheme. When disagreements arose, we discussed different interpretations, revisited the original text, and adjusted the coding to better reflect the data. This process continued until we reached a consensus on the emerging categories and their relationships.

3 Results

3.1 Reflection is social by nature

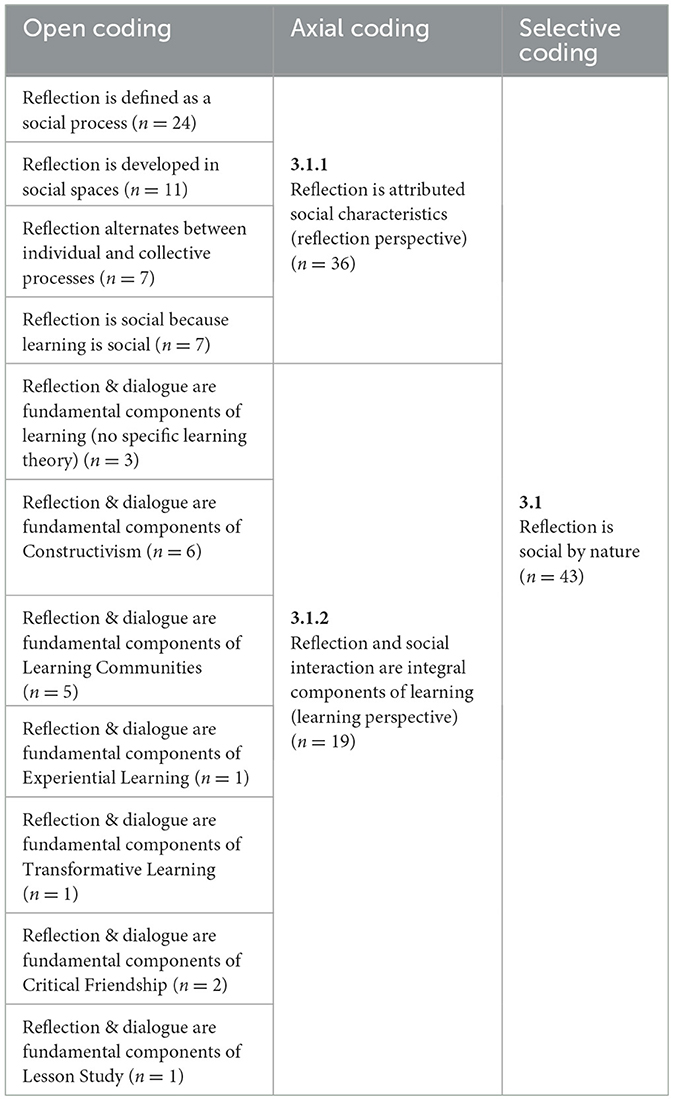

Seeking the ways in which researchers describe the relationship between reflection and social interaction, a recurring pattern in our data was statements indicating that social interaction and reflection are inherently interrelated. In other words, some researchers seem to acknowledge reflection as social by nature. The statements that supported this inference derived from 43 publications of the sample, grouped into two categories (see Table 1), which will be elaborated in the following sections:

• statements that explicitly attributed social characteristics to reflection (the reflection perspective—see Section 3.1.1), and

• statements referencing existing learning theoretical frameworks, that view reflection and social interaction as two essential components of learning (the learning perspective—see Section 3.1.2).

3.1.1 Reflection is attributed social characteristics

The first type of evidence that supports the inherently social nature of reflection was a set of sentences/phrases that explicitly attribute social characteristics to reflection. More specifically, there were statements from thirty-six (n = 36) publications that (a) define reflection as a social process, (b) conceive reflection evolving in nurturing social environments (c) view reflection as an alternation between individual and collective processes, and (d) assume the social nature of reflection drawing from the social nature of learning. A more thorough description of the four groups of statements follows.

3.1.1.1 Reflection is defined as a social process (n = 24)

Various social adjectives were used to describe the social nature of reflection. Reflection was characterized as a social (Behizadeh et al., 2019; Bener and Yildiz 2019; Lee and Choi, 2013), dialogic/dialogical (Clegg et al., 2005; Gutiérrez et al., 2019), collegial (Jones and Ryan, 2014), communal (McGarr et al., 2019), collaborative (Barnes and Gillis, 2015; Behizadeh et al., 2019; Gutiérrez et al., 2019), communicative (Park, 2015) and interactive (Aparicio Landa et al., 2021) process. These statements attributed social properties to the reflection process. Additional statements suggesting that reflection is a social process derived from fifteen publications (n = 15) that presented definitions of reflection which explicitly highlighted social interaction as a structural component of the reflection concept. In some of these cases, authors quoted and discussed known definitions in reflection research, for example “Farrell (2015) defined the reflective practice as “a cognitive process accompanied by a set of attitudes in which teachers systematically collect data about their practice, and while engaging in a dialogue with others use the data to make informed decisions about their practice” (p. 123)” (Almusharraf, 2020, p. 549), In other cases, authors of the sample introduced their own definitions of reflection, that included the social element, by synthesizing existing reflection literature: e.g., “Reflection is multivalent in nature and includes dimensions such as the awareness of different stakeholders' voices, be they peers or students (Greenwalt, 2008), or the examination of problems from different perspectives (Rodman, 2010), which is promoted by collaborative and partnership working (Parsons and Stephenson, 2005)” (Lamb et al., 2012, p. 23). All the above definitions highlight a pattern regarding how researchers conceptualize reflection in relation to social interaction: sociality is a defining characteristic of reflection.

3.1.1.2 Reflection is developed in social spaces (n = 11)

Eleven publications stated that reflection evolves in nurturing social environments. In this category, we included statements that highlighted the importance of structuring reflective activities within environments where student teachers can effectively interact e.g., “In order for teachers to develop reflexivity it is important to include dialogue, collaboration, and the establishment of trusting relationships (Warin et al. 2006, p. 243)” (Siry and Martin, 2014, p. 8). Some statements assigned in this category also emphasized the need for a combination of social and individual reflection activities in teacher education, e.g., “The two key components of reflective learning in terms of student participation—individual engagement and collaborative involvement—have to be properly reflected in a learning process to some degree (Balafoutas et al., 2003; Ryberg and Larsen, 2008)” (Park, 2015, p. 392).

3.1.1.3 Reflection alternates between individual and collective processes (n = 7)

The statements included in this category, stress the fluidity of reflection moving inwards and outwards of the self e.g., “…a complex and fluid process of moving inward (personal and biographical dimensions) and outward, (institutional, cultural, and political contexts of teaching)…” (Carlson, 2019, p. 2). A publication (Granberg, 2010) quoted Tsang (2007), who describes reflection as a process beginning with an internal dialogue, which then triggers an “external” dialogue during interaction with others, and subsequently returns to reinforce the initial internal dialogue: “Tsang claims that before students can confront their ideas with other students, they need to take part in an internal dialogue to process individual understandings and experiences. As a next step, they will interact in an external dialogue, sharing ideas and perspectives that can either be acknowledged or challenged, and will then return to an internal dialogue” (Granberg, 2010, p. 348). While Tsang defines reflection as a process involving an alternation between introspection and extrospection, Gillespie (2007), quoted by Liu (2014), acknowledges this “cognitive shift” between the two worlds (individual and collective) and adds an additional element to the process. This element is internalization, which refers to the evaluation and comparison of the ideas of the “other” with the individual's pre-existing ideas before assimilation: “Self-reflection arises ‘through internalizing the perspective that the other has upon self, followed by self taking the perspective of other upon self' (Gillespie, 2007, p. 682)” (Liu, 2014, p. 41). The “social” is actively integrated into the “self”.

3.1.1.4 Reflection is social because learning is social (n = 7)

The statements assigned in this category, presented reflection as a learning process that directly inherits attributes from learning, specifically here its social attributes. An indicative example was found in the publication of Chuang (2010), which assumes that cognition and reflection probably share common mechanisms, one of which is growth through social interactions: “Vygotsky's theoretical framework suggests that social interaction plays a fundamental role in the development of cognition (Vygotsky 1978). Increase in social interaction will ultimately promote an individual's reflective practice…” (p. 213). Another example is included in the paper of Ruan and Beach (2005), where authors contested the idea of reflection as an individual process, based on the premise that learning is social: “… teacher educators have a tendency to treat reflection as a personal and private act. This phenomenon contradicts what we know about the social nature of learning” (p. 65). The statements of this category suggest that reflection is in constant dialogue with learning and incorporates learning principles like the social mediation of meaning construction. In other words, if learning is social, then reflection must be social.

3.1.2 Reflection and social interaction are both integral components of learning

Sentences and phrases from 19 publications (n = 19) stated that reflection and social interaction are two integral components of learning. Those statements either explicitly supported this premise e.g., “Dialogue and reflection are considered the critical factors in a ‘meaning making' process” (Liu et al., 2014, p. 41), or were extended references to learning frameworks that interrelate reflection and social interaction under the constructivism umbrella:

• Constructivism Theory (n = 6): learning under the social constructivism paradigm unfolds during individual (internal negotiation) and collective (social negotiation) enactments of reflection (Park, 2015; Deng and Yuen, 2009, 2011; Wach, 2015; Kalsoom et al., 2022; Murphy et al., 2021).

• Learning Communities Model (n = 5): in Communities of Practice (Daniel et al., 2013; Hawkins and Park Rogers, 2016), as well as in Communities of Inquiry (Redmond, 2014; Morales et al., 2016; Enochsson, 2018), learning is constructed through dialogue and reflection.

• Experiential Learning Model (n = 1): the model of Experiential Learning (Kolb, 2017) referenced in the publication of Aparicio Landa et al. (2021), proposes that learning takes place in interaction with others through four cyclical stages: experiencing, reflecting, abstracting, and acting.

• Transformative Learning Theory (n = 1): critical reflection and discourse are considered the premises of Mezirow (1997) theory of Transformative Learning (Addleman et al. 2014).

• Critical Friendship Model (n = 2): Critical Friendship is based on systematic reflection (Carlson, 2019) and Critical Colleagueship supports deeper reflection (Behizadeh et al., 2019).

• Lesson Study Method (n = 1): Lesson study is a collaborative method widely used in teacher learning, which includes stages of collective reflection (Jain and Brown, 2022).

In all the above theoretical frameworks, reflection and social interaction are connected under the construct of learning.

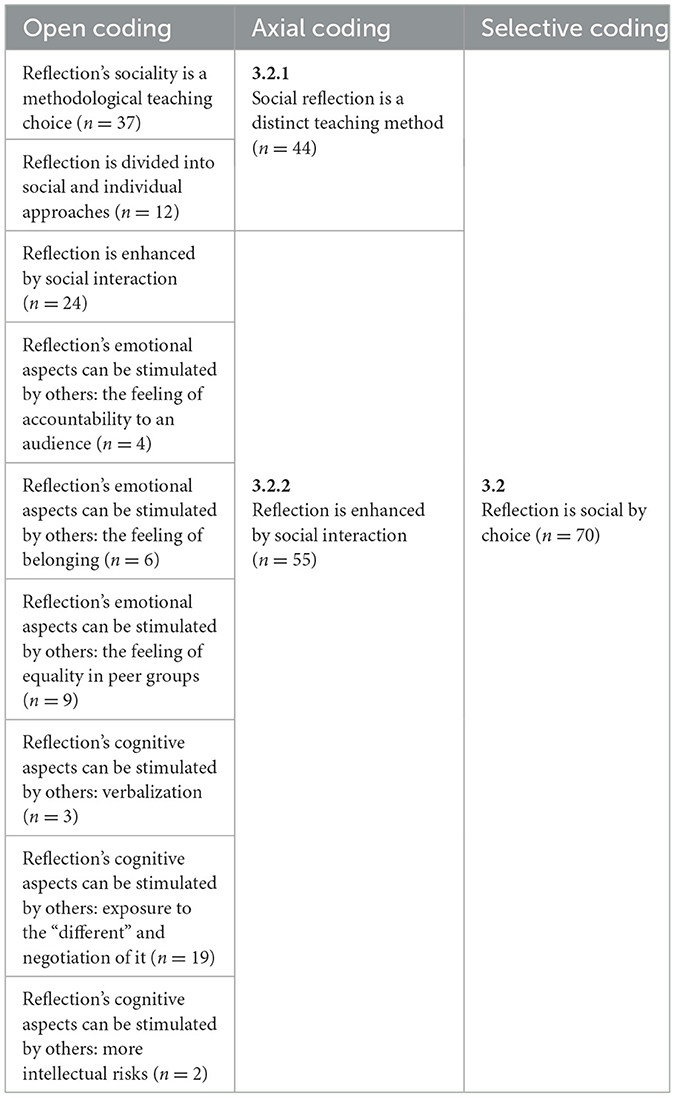

3.2 Reflection is social by choice

Beyond the statements that present sociality as an inherent aspect of reflection (Section 3.1), the data also provided evidence of sociality as a strategic, intentional, methodological choice to enhance reflection (n = 70). Sociality as a methodological choice in reflection emerges through

• statements that portray socially mediated reflection as a discrete reflection method (see Section 3.2.1), and

• statements that describe the beneficial impact of infusing social interaction experiences into reflection activities (see Section 3.2.2).

Here, the relationship between reflection and social interaction can be described in the following way: reflection can potentially embrace social teaching methods for greater effectiveness, reflection “chooses” to be social to its advantage. Presenting socially mediated reflection as an autonomous method among others implies that a teacher educator can choose to use or not to use it: the infusion of social interaction in reflection activities is a matter of choice. Table 2 demonstrates the coding process employed to reach the inference that “Reflection is social by choice”.

3.2.1 Social reflection is a distinct teaching method

In 44 publications (n = 44), the authors included statements that presented social interaction as a distinct reflection method that teacher educators can use. Those statements (a) present various reflection methods, among which the “social reflection” method, and (b) clearly distinguish reflection methods into social and individual approaches. These two types of statements elaborated below, reinforce the conceptualization of socially mediated reflection as an “autonomous” method and, therefore, an available methodological choice for teacher educators.

3.2.1.1 Reflection's sociality is a methodological teaching choice (n = 37)

In five publications (n = 5), the authors described a variety of available methods to promote reflection, among which are social methods of teaching. An indicative example can be found in the publication of Çimen and Çakmak (2020), where nine reflection methods were referred, including social methods: “According to Çubukçu (2011, p. 307), teachers can use diary-keeping, concept maps, mind maps, asking questions, self-questioning, self-assessment, negotiated learning, learning essays, and reflective discussions to promote reflective thinking” (Çimen and Çakmak, 2020, p. 933, emphasis added). Statements like this imply that teacher educators consider socially mediated reflection as one of the options among a wide range of reflection techniques in their arsenal. This distinct methodological teaching option was also described by different terms in the publications of our sample: mostly as “collaborative reflection” (n = 20), “collective reflection” (n = 8), “peer-reflection” (n = 8), and more rarely as “dialogic reflection” (Hepple, 2012; Stefanski et al., 2018), “social reflection” (Lord and Lomicka, 2007; Schechter and Michalsky, 2014), “co-reflection” (Fund, 2010), “joint reflection” (Krutka et al., 2014), “socially-mediated reflection” (Park, 2015), “group reflection” (Hawkins and Park Rogers, 2016), “shared reflection” (Redmond, 2014), “communal reflection” (Mantle, 2019) and “socio-cultural reflection” (Yuan and Mak, 2018). The above terms sometimes (n = 13) coexisted in a single publication and were used interchangeably, maybe stressing the fluidity of their use.

3.2.1.2 Reflection is divided into social and individual approaches (n = 12)

Another category formed the statements that stressed even more the conception of socially mediated reflection as a distinct method, by dividing reflection approaches into individual and social ones. Authors used (a) comparative expressions e.g., “collaborative rather than individualistic approach to reflection… (Rettig, 2013, p. 40), (b) disjunctive propositions e.g., ‘Individuals can engage in reflection independently or with others…' (Shin, 2021, p. 372), or (c) contrasting sentences e.g., Individual reflection, a staple of most field experiences, serves as the key for unlocking the reflective understandings resulting from field experiences (Ohana 2004). Collaborative reflection on field experiences, on the other hand, provides…” (Subramaniam, 2013, p. 1857). Some of the authors who distinguished reflection in social and individual approaches, also argued that both approaches are useful and should be combined in teacher education (Fund, 2010; Tanet al., 2010; Krutka et al., 2014; Cavanagh and McMaster, 2015; Barry and Caravan, 2020; Williams, 2020). Especially Fund (2010) grounded its study in this belief and incorporated both forms of reflection acknowledging student teachers' potential preference toward one or the other reflection style “… researchers differentiate between student-teachers with an internal orientation (those preferring reflection), and those with an external orientation who rely mostly on support, advice and guidance from outside sources. With this in mind, we integrated guidance toward both orientations in our feedback study. Better to meet the needs. of internally oriented students, we provided for written reflections while also providing externally oriented guidance (i.e., feedback on these reflections) for those who rely more on this type of guidance” (Fund, 2010, p. 682).

3.2.2 Reflection is enhanced by social interaction

The second category of statements that reinforces the position of reflection being “social by choice”, derived from statements that present social interaction as an available option to enhance reflection. A comprehensive picture of the effectiveness of social interaction in reflection exceeds. the scope of this specific review. However, authors' statements that relate social interaction with deeper reflection in fifty-five (n = 55) publications could not go unnoticed concerning our research question. These papers seemed to present social interaction as a promising method to enhance student teachers' reflection, e.g., “Many teacher educators believe that the optimal means for encouraging critically reflective thinking in teachers is through communities of peers engaged in dialogue about educational issues and dilemmas” (Wade et al., 2008, p. 399). In 31 out of the 55 papers, authors also used evidence-informed arguments on the effectiveness of social interaction in reflection, through statements that describe how “others” stimulate emotional and cognitive engagement in reflection. The connection between reflection and social interaction outlined by these authors seems to be that reflection is enhanced when enacted in interaction with others.

3.2.2.1 Reflection's emotional aspects can be stimulated by others (n = 17)

In 17 publications we traced statements denoting that social interaction enhances emotional engagement in reflection. The statements assigned in this group indicate that socially mediated reflection incites the following feelings:

• The feeling of accountability to an audience (n = 4). When reflecting with “others” the thoughts have a recipient, an audience that will receive them, someone to address to, an accountable “other”. The sense of the presence of one or more people who “await” to receive the reflector's thoughts enhances the motive to reflect. It encourages reciprocity and intensifies persistence to continue engaging in the reflective process, increasing the frequency, prolonging, and maintaining the reflective process (Clegg et al., 2005; Fund, 2010; Cavanagh and McMaster, 2015; Gonen, 2016).

• The feeling of belonging (n = 6). Interaction with others during reflection can create a supportive network of individuals who encourage each other (Allas et al., 2017). Involvement in such a supportive community validates each member's experience as significant (Clegg et al., 2005) and alleviates emotional pressure (Lassila et al., 2017). While individual reflection may lead to a sense of isolation, a community of individuals reflecting collaboratively reduces these feelings (Nguyen and Ngo, 2018; Carlson, 2019) and encourages a sense of belonging to a broader community (Ong et al., 2020).

• The feeling of being equal (n = 9). Interaction with peers during reflection seems to invoke the positive feeling of being equal. The exposure of reflective thoughts to peers reduces feelings of vulnerability compared to exposing them directly to persons with authority like professors (Kaplan et al., 2007). This way, the threat is reduced (Almusharraf, 2020), and a framework of security is provided (Lord and Lomicka, 2007), allowing the reflective process to unfold in a non-threatening atmosphere (Gonen, 2016). Peers share a common communication code, status, and similar experiences which encourage a sense of equality, upon which they can form a safe environment to reflect (Barnes and Gillis, 2015; Allas et al., 2017; Straková and Cimermanová, 2018; Choo et al., 2019; Yüksel and Başaran, 2020).

3.2.2.2 Reflection's cognitive aspects can be stimulated by others (n = 20)

Twenty publications included statements that explain why social interaction enhances cognitive engagement in reflection. Three reasons were detected:

• Verbalization (n = 3). When communicating a thought to another person “the individual makes choices: what to include, what to leave out, where to place extra description, why highlight a particular point and so on” (Mantle, 2019, p. 5). This process is known as verbalization and is an important way of enhancing the quality of reflection, encouraging individuals to further analyze the context, the causes, and the connections of their thoughts and articulate arguments (McMahon, 1997; Tuma and Šaffková, 2012).

• Exposure to the “different” and negotiation of it (n = 19). During interaction with “others” individuals encounter different perspectives that scaffold and expand their ways of understanding beyond personal experiences (Harford and MacRuairc, 2008; Min et al., 2020; Williams, 2020; Shin, 2021). Exposure to diverse perspectives can transform problematic long-held beliefs of student teachers, and lead to new meanings and practices (Clegg et al., 2005; Lee and Choi, 2013; Allas et al., 2017; Clegg et al., 2019; Almusharraf, 2020; Çimen and Çakmak, 2020). Moreover, diversity within the dynamics of a group can lead to deep reflection activating the strengths of each member and enabling them to complement one another and cover each other's weaknesses (Nguyen and Ngo, 2018). Diversity seems to enrich reflection, nevertheless, this does not seem to happen automatically when exposed to diverse viewpoints. It is necessary to activate a mechanism of “challenge” to the different so that the reflective individual moves beyond their perspective and compares it with others (Clarà et al., 2019; Körkkö, 2021). If different viewpoints are merely presented without prompting fruitful questioning or exploration, they do not advance reflection. Assumptions need to be questioned, critical questions to be posed, and cognitive conflicts to be provoked in order to consciously examine the subjective and objective aspects of a situation through substantial negotiation (Lamb et al., 2012; Krutka et al., 2014; Barnes and Gillis, 2015; Straková and Cimermanová, 2018; McGarr et al., 2019).

• More intellectual risks (n = 2). Even though traced only in two publications of the sample, the statement that those who reflect in interaction with others take more intellectual risks (Carlson, 2019; Yüksel and Başaran, 2020) is an interesting one. In fact, Carlson (2019) further explained that individual methods of reflection amplify the emotional risks, while social approaches encourage the intellectual risks: “While private journals (…) have been shown to compel personal/emotional risks, other more public formats (…) have been found to authorize students to take more intellectual/logical risks (Foster, 2015)” (Carlson, 2019, p. 1).

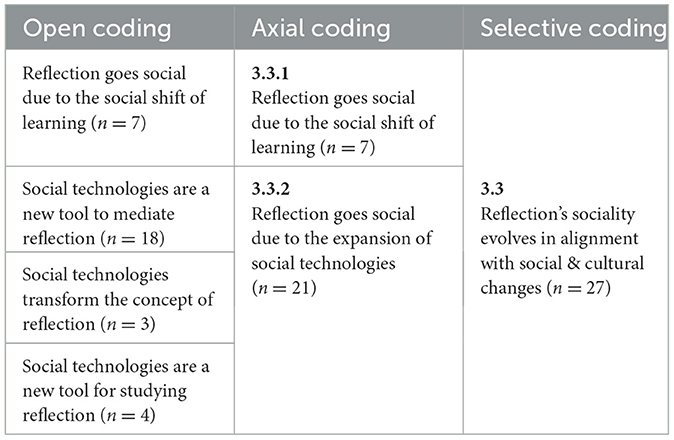

3.3 Reflection's sociality evolves in alignment with the social “turn” in learning and technology

The last category of statements includes sentences and phrases that discuss reflection and social interaction with references to the changing landscape in which this relationship occurs. Thus, reflection was presented in twenty-seven (n = 27) publications as an evolving concept that progressively acquired social characteristics, due to changes at social and cultural levels. More specifically, data analysis indicates that several researchers have highlighted the increasing visibility of the social aspect of reflection, and attributed it to the shift in social learning (3.3.1) and/or the expansion of social technologies (3.3.2) (see Table 3).

3.3.1 Reflection goes social due to the social shift of learning

Some publications of the sample (n = 7), written in the last two decades, stated that reflection has shifted toward social orientations because our views of learning have changed toward collective meaning-making processes that incorporate principles of collaborative learning and peer discourse e.g., “As the socio-cultural perspective on learning has developed, the notions of learning and reflection have broadened in context, involving not only our individual minds, but also our social and cultural environments” (Granberg, 2010, p. 348). Some authors noticed that reflection gradually adopts the contemporary learning principles that underlie teacher education like peer mentoring “the shift toward prospective teachers' collaborative learning and peer discourse resonates with emerging conceptualizations of mentoring as a collegial learning relationship instead of hierarchical (top-down, one-way) learning relationship” (Le Cornu and Ewing, 2008)” (Schechter and Michalsky, 2014, p. 4), the view of emotions as a social experience: “…historically, emotions have been cast as internal, situated within a person (Burrow, 2000). Thus, our study fills a gap in reflection research, because reflection in teacher education has largely been cast as a personal emotive experience rather than social” (Falter and Barnes, 2020, pp. 68, 69), or the emergence of social constructivism: “Relatively recently, the concept of collaborative or collective reflection has received more attention (Daniel et al., 2013; McCullagh, 2012) because it is aligned with the social construction view of learning” (Kalsoom et al., 2022, p. 165).

3.3.2 Reflection goes social due to the expansion of social technologies

The last category of statements, found in articles published after 2004, implies that the rise of social technologies has influenced and expanded the teaching methods, the conceptualizations and the research tools of reflection in teacher education (n = 21).

3.3.2.1 Social technologies are a new tool to mediate reflection (n = 18)

Authors frequently argued that technologically mediated communication has arisen as a popular, new, social method to mediate reflection e.g., “The rise of social media services has offered new possibilities for the creation of affinity spaces where participatory cultures of collaborative reflection might thrive” (Krutka et al., 2014, p. 85).

3.3.2.2 Social technologies transform the concept of reflection (n = 3)

Some authors of our sample inquired on whether this increasing use of social technologies by teacher educators for the purposes of reflection, has changed the nature of reflection itself: “These studies pointed to the trend of increased regular exposure to technology during the methodology training of FL teachers, which in turn may require us to reconsider our traditional notions of reflective practices (…) given the available technologies, we propose a recharacterization of reflective practices in teacher training programs in order to incorporate both individual and social compo” (Lord and Lomicka, 2007, p. 517). When reflecting together, student teachers may develop roles and behaviors that could not emerge in more traditional, individual activities (Too, 2013; Kalk et al., 2019), expanding the conceptualizations of reflection.

3.3.2.3 Social technologies are a new tool for studying reflection (n = 4)

The social reflection practices developed in online collective environments reveal new connections between reflection and social interaction. The process of reflection is externalized to others and documented on electronic platforms, which “can be a source of information about student learning (Dos and Demir, 2013), making it possible for us to assess reflection (Chaumba, 2015)” (Kalk et al., 2019, p. 1). In the same vein, new research variables emerge in online communication environments, enhancing the understanding of the social nature of reflection: “…level of student online interactivity is one of the key variables affecting the integration of reflective learning processes” (Park, 2015, p. 391).

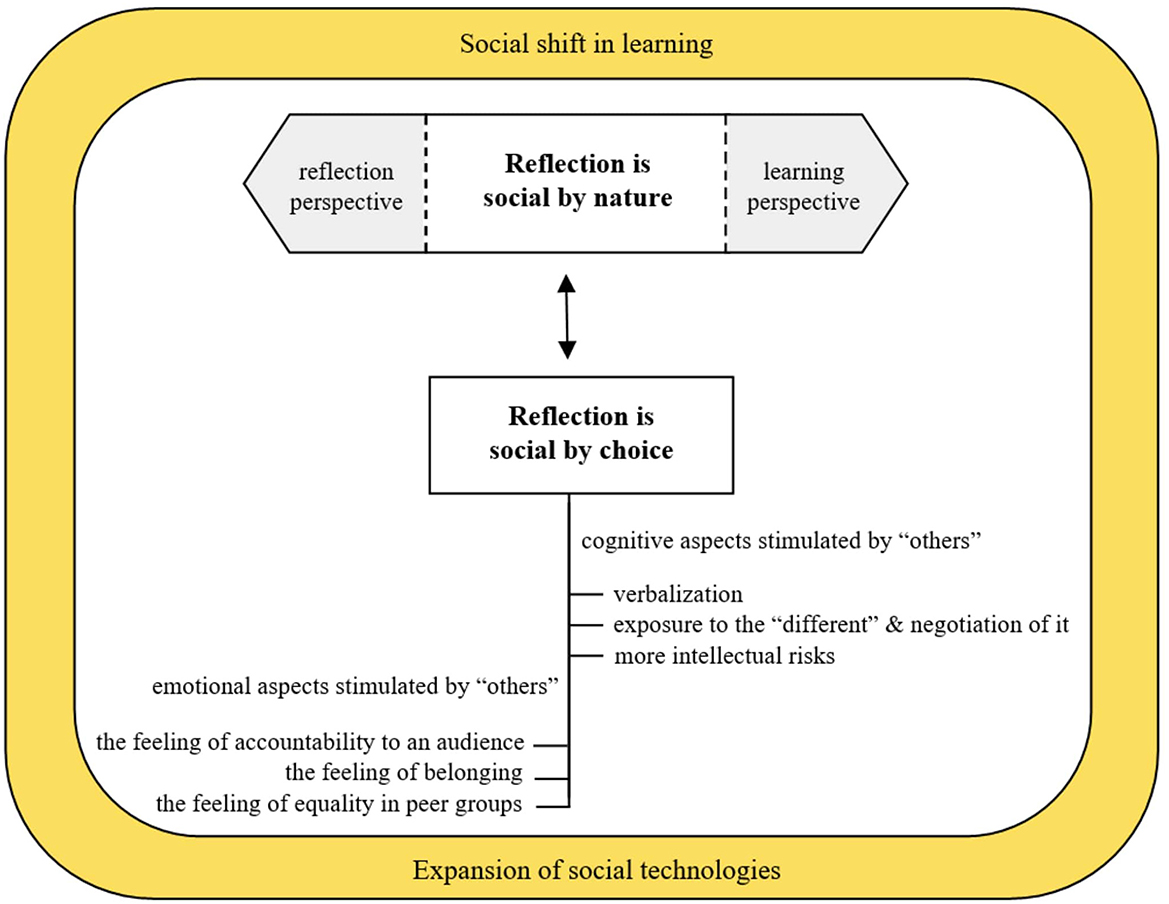

3.4 Convergence of the categories into a unified scheme

To be able to see all the above in a coherent whole, we attempted to converge the categories of statements that emerged into a unified scheme. Figure 3 represents a unified hermeneutical scheme of all the positions raised in the results of this review on how reflection is presented in relation to social interaction.

Figure 3. The social nature of reflection in teacher education research. Scheme portraying the connections among the categories that emerged through grounded theory analysis—a visual representation of results' central position.

The first broad category of statements identified in response to our research question is that reflection is “social by nature” (Section 3.1). This inference emerged through statements that explicitly attribute social characteristics to reflection (Section 3.1.1), and statements that define reflection and social interaction as two integral components of learning, implying tacit connections of reflection and social interaction working in synergy during learning (3.1.2). We could characterize the first group of statements as the “reflection perspective” (Section 3.1.1), and the second group as the “learning perspective” (Section 3.1.2), both of which seem to introduce a different route to theoretically substantiate the social nature of reflection (see Figure 3).

At the same time, the social attribute of reflection is presented as a methodological choice of teacher educators to enhance reflection (Section 3.2). This “social by choice” conception of reflection is derived from statements that view socially mediated reflection as a distinct method of reflection (Section 3.2.1), with unique characteristics that enrich and encourage the reflection process emotionally and cognitively (Section 3.2.2). Nevertheless, the analysis of the 98 publications indicated that the “social by nature” and the “social by choice” positions are not mutually exclusive but coexist in 28 publications. This fluidity between them is portrayed with a bidirectional arrow between them in Figure 3. Finally, all these conceptualizations are framed by the sociocultural context in which they evolve (Section 3.3). Educators' focus on the social learning perspective (3.3.1), as well as the expansion of social technologies that offer new tools to mediate and study reflection (3.3.2), result in the increasing visibility of reflection's sociality and frame it (depicted as the square frame of Figure 3).

4 Discussion

This interpretative systematic review sought to detect how researchers present the social dimension of reflection in teacher education. A grounded theory analysis of the introductory sections of 98 research papers that study peer-mediated reflection activities in teacher education, indicated that researchers described reflection's sociality in ways that may seem contradictory at first sight: sociality was presented as an inherent characteristic of the reflection process substantiated in reflection definitions and social learning theoretical frameworks (reflection is social by nature), and at the same time, as an acquired characteristic, purposefully infused in reflection activities by teacher educators to methodize them more effectively (reflection is social by choice). Furthermore, the publications examined displayed two key aspects that shape the relationship of reflection and social interaction: the interrelation of reflection with learning, and the affordances of social technologies through which reflection is conducted and studied. In the following paragraphs, we discuss further these findings.

4.1 Reflection is social by nature and by choice

Researchers of our sample presented sociality most often as a methodological choice to trigger emotional and cognitive aspects of the reflection process (social by choice), rather than as a defining characteristic of reflection (social by nature). The prevalence of methodological rather than conceptual concerns in researchers' discussions, could be related to an implicit acceptance of the social nature of reflection that doesn't evoke further conceptualization discussions. Another reason for this observation could be the absence of theoretical framing for the social dimension of reflection. In the absence of theoretical framing (Collin and Karsenti, 2011; Watanabe and Tajeddin, 2022), researchers may be more prone to overlooking the grounding of the social nature of reflection in a theoretical base, often shifting their focus directly to applications and empirical data that support the methodological choice of incorporating social interaction into teachers' reflective experiences. In other words, the prevalence of reflection as “social by choice”, may be due to the lack of “social by nature” arguments in the bibliography, and not a preference of authors over one position or the other.

The assumption that authors do not hold a strict position toward reflection's sociality “by nature” or “by choice”, is reinforced by the finding that these two positions coexist in the rationale of the authors in merely 1/3 of the papers studied. Reflection in these papers can be viewed as both social by nature and by choice. Seeking for convergence in the conceptualizations of the authors of our sample, we could say that researchers often seem to embrace both positions and dare to employ and explore the social dimension of reflection despite the lack of theoretical frameworks in the field. This could be interpreted as an implicit agreement on the social nature of reflection, where its practical use takes precedence over an immediate exploration of its theoretical origins. Maybe the reflection concept in general, not only its social dimension, follows this pattern. After decades of study, researchers are coming to an agreement that reflection may never be strictly defined in theory, as it is (and probably will remain) an open, multifaced and differently interpreted concept (Watanabe and Tajeddin, 2022). The fact that reflection is used as an established term in society, education, and particularly in teacher education, without being precisely defined, may indicate, that its significance surpasses the lack of a universal definition. Similarly, the social nature of reflection, which is considered an integral part of it to this day, seems to be accepted and important, even though it is not fully understood, without this detracting from its value.

4.2 Reflection is co-depended to learning's social nature

Another interesting observation stemming from the results is that the concept of learning may play a key role in understanding the social dimension of reflection, given the different groups of statements observed highlighting the social attributes that learning and reflection share. In some of these cases, learning was presented to directly transfer social attributes to reflection. In other statements, reflection was portrayed with a more dynamic role, working in synergy with social interaction to promote learning. The emphasis on learning upon which researchers ground the sociality of reflection could be explained considering the origins of the reflection concept. Dewey (1910/1978) introduced reflection in order to understand human thinking and learning processes. Reflection was “invented” for the sake of learning. Therefore, turning to learning theories seems to be a valid and rational path through which researchers could illuminate some aspects of reflection's sociality and theoretically frame it.

On the other hand, overemphasizing learning, especially in statements in which learning “just” transfers social properties to reflection, may oversee the role of reflection's special characteristics that shape its sociality. Reflection's conceptualization through learning theories is essential to also include reflection theory and return to inform the latter. The inference that reflection is social because learning is social has face validity but may lead to taking reflection's sociality as granted, without further exploration, perpetuating its conceptualization ambiguities discussed in the introduction of this paper. Reflection is a learning-bound concept, but learning is a reflection-bound concept as well (Al Mahmud, 2013). If we are to explore reflection's sociality through learning, which many authors proved to do, we have to ensure that both reflection and learning are explored in their own right, acknowledging their distinct yet interconnected nature. This involves critically examining the nuances of how reflection shapes and is shaped by social learning processes, rather than assuming a one-way influence from learning to reflection.

4.3 Reflection's sociality is dynamically evolving

Some authors of the sample indicated that sociality is a dynamically evolving characteristic of reflection, influenced by the social turn in learning and technology. This finding could be interpreted in combination with the timeline in which the studies of the sample were distributed. Although the bibliographic search dates back to 1983, the first publication traced to study thoroughly the social dimension of reflection in our sample was published in 1997. After this study, we observed an increasing number of relevant studies, mostly after 2005. In the late ‘90s, the “social environment” perspective in learning was spreading (Tennant, 1997), along with the rise of constructivism (Ashworth et al., 2004) which embraced the social perspective as co-construction of meaning through inquiry and negotiation (Merriam et al., 2007). Al Mahmud (2013) assumes that these characteristics of constructivism set the ground for the emergence of the reflective thinking school. Reflection, in turn, offered constructivism-specific tools and strategies to develop. This reciprocal relationship of reflection with constructivism may have led to the expansion of both simultaneously, at the end of the twentieth century (ibid.).

Considering the above, the finding that the social aspect of reflection has historically evolved in alignment with the social turn in learning appears to be supported by the literature. Similarly, the findings suggest that this sociality of reflection was prompted by the emergence of social technologies. The year 2005 was verified as the year when the burst of publications of our sample was observed, coinciding with the year after the social web technologies were established with the term Web 2.0 in 2004 (O'Reilly, 2009) denoting their wide recognition. Some authors of the sample suggested that the social technologies wave increased the visibility of reflection's sociality, by multiplying the array of tools that teacher educators possess to mediate and study collective reflection activities. Some of them also believed that this subsequently transformed the very nature of reflection toward a more interactional and extroverted direction and permitted new reflection practices to emerge. The arguments of the authors seem rational, considering that technology is not a passive medium, its use affects and alters the way we interact and think (Turkle, 2005). Overall, it appears that reflection gradually evolved toward more social paths from the beginning of the twenty-first century and afterward, adapting to the “social era”. Besides, every concept evolves semantically (Wei et al., 2018), aligning with the values, culture, and practices of each historical period, and so did reflection. The evolution of Dewey's thinking on reflection from an individual process (Dewey, 1978) to a process occurring in a social context (Dewey, 1986), is a notable example of this evolving process (Prawat, 2000).

4.4 Limitations

First, we need to address the limitations concerning the grounded theory method employed. Grounded theory includes interpretative processes, which attribute a subjective perspective to the development of any conceptual framework. This subjectivity is recognized by the literature. However, it is also argued that embracing subjectivity and allowing the researcher's values to influence the creation of meaning has a strong scientific value, and can capture the nuanced, multidimensional aspects of human behavior (Charmaz, 2006). We also need to acknowledge that regarding the critical appraisal criteria, especially the conceptual quality criterion, our methodology may have favored recent publications due to broader trends in how teacher reflection is historically framed in academic literature. Nevertheless, these criteria ensured that all included articles—regardless of publication date—provided sufficient conceptual clarity on reflection and social interaction. Finally, we recognize that narrowing our choices in English language studies and focusing solely on the initial teacher education field instead of all the stages of the teacher education continuum, may have influenced the scope of our findings. Future research could complement this work by extending the review in induction and in-service teacher education activities, as well as in publications of non-English literature.

4.5 Conclusion

The main finding of this study is that reflection in teacher education appears to operate along a dynamic continuum between being “social by choice” and “social by nature”, shaped by evolving social learning theories and social technologies. In other words, although some reflection processes may require solitude and therefore private reflection tools, social interaction will always be part of conceptualizing and implementing reflection.

Teacher educators are encouraged to embrace the fluidity of the social dimension of reflection and to develop flexible, adaptive models of reflection that cater to their students' needs. Furthermore, the influence of social technologies on reflective practice suggests that teacher education activities could employ online communication tools to facilitate opportunities for meaningful collaborative reflection. The social dimension of reflection appears to herald an era that fosters creativity and interconnections with other educational tools. However, any such experimentation needs to consider reflection's distinct characteristics and be theoretically supported.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MT: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The publication of this article was financially supported by the Hellenic Scientific Association of Information and Communication Technologies in Education (ETPE), through the award of the Meni Tsitouridou scholarship.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Dr. Maria Birbili, Dr. Anastasia Kalogiannidou, and PhD researcher Maria Tsaroucha for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions on earlier versions of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1521473/full#supplementary-material

References

Ahmad, M. F. B. (2024). Exploring video use in student teachers' collaborative reflection: an action research project. TESOL J. 15:3. doi: 10.1002/tesj.813

Al Mahmud, A. (2013). Constructivism and reflectivism as the logical counterparts in TESOL: learning theory versus teaching methodology. TEFLIN J. 24, 237–257. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v24i2/237-257

Aromataris, E., and Munn, Z., (eds.). (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

Ashworth, F., Brennan, G., Egan, K., Hamilton, R., and Sáenz, O. (2004). Learning theories and higher education. Level 3 3, 1–16. doi: 10.21427/D7S43V

Baer, A. (2022). Perspective-taking and perspectival expansions: a reflection and an invitation. Commun. Inf. Liter. 16, 38–41. doi: 10.15760/comminfolit.2022.16.1.4

Beauchamp, C. (2006). Understanding reflection in teaching: A framework for analyzing the literature [dissertation]. McGiII University, Canada.

Behizadeh, N., Thomas, C., and Behm Cross, S. (2019). Reframing for social justice: the influence of critical friendship groups on preservice teachers' reflective practice. J. Teach. Educ. 70, 280–296. doi: 10.1177/0022487117737306

Carlson, J. R. (2019). “How am I going to handle the situation?” The Role (s) of Reflective Practice and Critical Friend Groups in Secondary Teacher Education. Int. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 13:1. doi: 10.20429/ijsotl.2019.130112

Cavanagh, M., and McMaster, H. (2015). A professional experience learning community for secondary mathematics: developing pre-service teachers' reflective practice. Math. Educ. Res. J. 27, 471–490. doi: 10.1007/s13394-015-0145-z

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Clarà, M., Mauri, T., Colomina, R., and Onrubia, J. (2019). Supporting collaborative reflection in teacher education: a case study. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 175–191. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1576626

Clark, W. R., Clark, L. A., Williams, R. I., and Raffo, D. M. (2025). Using a systematic literature review to clarify ambiguous construct definitions: identifying a leader credibility definitional model. Manag. Rev. Q. 183–217. doi: 10.1007/s11301-023-00378-w

Collin, S., and Karsenti, T. (2011). The collective dimension of reflective practice: the how and why. Reflect. Pract. 12, 569–581. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2011.590346

Collin, S., Karsenti, T., and Komis, V. (2013). Reflective practice in initial teacher training: critiques and perspectives. Reflect. Pract. Int. Multidiscip. Perspect. 14, 104–117. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2012.732935

Crichton, H., and Valdera Gil, F. (2015). Student teachers' perceptions of feedback as an aid to reflection for developing effective practice in the classroom. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 38, 512–524. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2015.1056911

Deng, L., and Yuen, A. H. (2011). Towards a framework for educational affordances of blogs. Comput. Educ. 56, 441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.09.005

Dewey, J. (1978). “How we think” in John Dewey: The middle works, 1899-1924, vol. 6, ed. J. A. Boydston. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1910), 177–356.

Dewey, J. (1986). “How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process” in John Dewey: The later works, 1925-1953, vol. 8, ed J. A. Boydston. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1933), 105–352.

Ekin, S., Balaman, U., and Badem-Korkmaz, F. (2021). Tracking telecollaborative tasks through design, feedback, implementation, and reflection processes in pre-service language teacher education. Appl. Linguist. Rev. 15, 31–60. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2020-0147

Elhussain, S., and Khojah, A. (2020). Collaborative reflection on shared journal writing to foster EFL teacher CPD. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 15, 271–281. doi: 10.18844/cjes.v15i2.4598

Epler, C. M., Drape, T. A., Broyles, T. W., and Rudd, R. D. (2013). The influence of collaborative reflection and think-aloud protocols on pre-service teachers' reflection: a mixed methods approach. J. Agricult. Educ. 54, 47–59. doi: 10.5032/jae.2013.01047

Erdemir, N., and Yeşilçinar, S. (2021). Reflective practices in micro teaching from the perspective of preservice teachers: teacher feedback, peer feedback and self-reflection. Reflect. Pract. 22, 766–781. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.1968818

Farrell, T. S. (2018). “Reflective practice for language teachers” in The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching, ed J. I. Liontas (John Wiley and Sons), 1–6.

Gedera, D. S., and Fester, A. M. (2023). Integrating eportfolios to facilitate collaborative learning and reflection in an EAP context. Teach. English Technol. 23, 108–122. doi: 10.56297/BKAM1691/VZBA3686

Gillespie, A. (2007). “The social basis of self-reflection,” in The Cambridge Handbook of Sociocultural Psychology, eds. J. Valsiner and A. Rosa (Cambridge: Cambridge University), 678–691. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511611162.037

Gonen, S. (2016). A study on reflective reciprocal peer coaching for pre-service teachers: change in reflectivity. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 4, 211–225. doi: 10.11114/jets.v4i7.1452

Hansen, M., and Mendzheritskaya, J. (2024). Reflecting team–a structured method for peer reflection on challenges in teaching. Reflect. Pract. 25, 164–177. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2024.2305887

Harford, J., MacRuairc, G., and McCartan, D. (2010). Lights, camera, reflection: using peer video to promote reflective dialogue among student teachers. Teach. Dev. 14, 57–68. doi: 10.1080/13664531003696592

Hommel, M., Fürstenau, B., and Mulder, R. H. (2023). Reflection at work - A conceptual model and the meaning of its components in the domain of VET teachers. Front. Psychol. 13:923888. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.923888

Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., et al. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 34, 285–291. doi: 10.3233/EFI-180221

Hong, Q. N., and Pluye, P. (2019). A conceptual framework for critical appraisal in systematic mixed studies reviews. J Mixed Methods Res. 13, 446–460. doi: 10.1177/1558689818770058

Jiang, Y., and Zheng, C. (2021). New methods to support effective collaborative reflection among kindergarten teachers: an action research approach. Early Childhood Educ. J. 49, 247–258. doi: 10.1007/s10643-020-01064-2

Kolb, A., and Kolb, D. (2017). The Experiential Educator. Principles and Practices of Experiential Learning. Kaunakakai, HI: EBLS Press.

Korthagen, F., and Nuijten, E. (2022). The Power of Reflection in Teacher Education and Professional Development: Strategies for In-Depth Teacher Learning. New York: Routledge.

Layen, S., and Hattingh, L. (2020). Supporting students' development through collaborative reflection: Interrogating cultural practices and perceptions of good practice in the context of a field trip. Early Years. 40, 306–318. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2018.1432572

Le Cornu, R. (2005). Peer mentoring: Engaging pre-service teachers in mentoring one another. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 13, 355–366. doi: 10.1080/13611260500105592

Le Cornu, R. (2010). Changing roles, relationships and responsibilities in changing times. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Educ. 38, 195–206. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2010.493298

Lizarondo, L., Stern, C., Carrier, J., Godfrey, C., Rieger, K., Salmond, S., et al. (2020). “Chapter 8: Mixed methods systematic reviews” in JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, eds. E. Aromataris, C. Lockwood, K. Porritt, B. Pilla, Z. Jordan. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed March 3, 2025).

Luca, M., Nuttall, J., Emilion, J., and Postings, T. (2022). Systematic review and grounded theory as a mixed method to develop a framework for counselling skills competencies. Counsell. Psychother. Res. 22, 98–107. doi: 10.1002/capr.12430

Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., and Baumgartner, L. M. (2007). Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons/Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: theory to practice. New Dir. Adult Cont. Educ. 74, 5–12.

Miller, L. R., Nelson, F. P., and Phillips, E. L. (2021). Exploring critical reflection in a virtual learning community in teacher education. Reflect. Pract. 22, 363–380. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2021.1893165

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and Prisma Group. (2010). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 8, 336–341.

Moher, D., Pham, B., Lawson, M. L., and Klassen, T. P. (2003). The inclusion of reports of randomised trials published in languages other than English in systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess. 7, 1–90. doi: 10.3310/hta7410

Morrison, A., Polisena, J., Husereau, D., Moulton, K., Clark, M., Fiander, et al. (2012). The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J. Technol. Assess Health Care. 28, 138–144. doi: 10.1017/S0266462312000086

Musset, P. (2010). Initial teacher education and continuing training policies in a comparative perspective: Current practices in OECD countries and a literature review on potential effects. ECD Education Working Papers (Paris: OECD), 48

Näykki, P., Laitinen-Väänänen, S., and Burns, E. (2022). Student teachers' video-assisted collaborative reflections of socio-emotional experiences during teaching practicum. Front. Educ. 7:846567. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.846567