- 1School of Education, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Education, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT, Australia

This systematic review examines the intersection of assessment and equity in education, with a particular focus on educationally disadvantaged students. Despite long-standing claims that assessment can enhance teaching and learning, little is known about assessment practices used in schools to increase educational outcomes for this student cohort. Drawing on international literature, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, we have identified inclusive assessments that support equitable practices, such as culturally responsive assessments, accessible assessments, and effective feedback practices. While these practices have been recognized for their potential to reduce bias and support fairer assessment, their implementation remains inconsistent and fragmented. In addition, our findings indicate that assessment design, assessment processes, teachers' assessment dispositions, knowledge, and skills, and policy influence the enhancement of equitable assessment. A notable gap is identified in the secondary education literature, along with an underrepresentation of studies from non-Anglophone contexts. Overall, our findings suggest the need for a more substantial investment in assessment-focused teacher education and development, as well as the integration of equity principles into policy frameworks. Addressing these gaps is essential to ensuring that assessment becomes a more effective tool for supporting educationally disadvantaged students.

Introduction

As school communities, teachers, and students recover from the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 crisis, concerns regarding equitable participation and achievement have been magnified (Cairney and Kippin, 2022). The term “equity” means different things in different educational contexts. International organizations such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization's (UNESCO, 2020) guide for ensuring inclusion and equity in education advocates for shared understandings in global educational contexts (Ainscow, 2020), but crafting common definitions and characteristics of educational disadvantage has remained difficult to achieve. International scholarly work has demonstrated that equitable education encompasses a range of elements, including inclusivity, power differentials within the classroom, socioeconomic status (SES), disability, ethnicity, nationality, language, culture, religion, sexuality, and race. However, these are valued and prioritized differently across (inter)national, sector, and sociocultural domains. From this review of the scholarly literature and in view of the limited progress made in Australia on lifting outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students, there is a clear warrant to explore the international literature for what is known about equitable assessment approaches. For the purposes of this paper, the terms fair and equitable are used interchangeably and refer to assessment of students who face (often intersecting) educational disadvantage including First Nations peoples (Snow et al., 2021), people living in low socio-economic status backgrounds (Clark, 2014), those who live in regional and remote locations (Charteris, 2015), migrants (including forced migrant) populations (Nortvedt et al., 2020; Triventi et al., 2021), students with out-of-home-care experience (Berger et al., 2023), and students with diagnoses that impact learning (Townend and Brown, 2016). Specifically, we use the terms “fair” and “equitable” interchangeably to refer to assessment practices that aim to reduce barriers and provide meaningful opportunities for students who experience educational disadvantage. This includes, but is not limited to, students from First Nations communities, low socioeconomic backgrounds, regional and remote areas, migrant and refugee populations, students in out-of-home care, and those with learning-impacting diagnoses.

The relationship between equity and assessment from the Australian perspective is examined before examining the international context. It is important to examine the Australian perspective within international literature to ensure that global understandings of educational equity are informed by diverse, context-specific experiences as Australia has made limited progress (Lamb et al., 2014). Australia presents a unique sociocultural and policy landscape, particularly in relation to its Indigenous populations, regional and remote communities, and children in out-of-home care (Perry and Lubienski, 2024). The prominence of assessment practices that incorporate non-dominant languages and culturally contextualized values and knowledge in international literature offers a compelling message for educators in colonial-settler contexts such as Australia. In these settings for example, First Nations Australians continue to face significant educational disadvantage due to systems that are not only rooted in Western and Eurocentric paradigms but have historically marginalized Indigenous ways of teaching and learning (Whatman and Singh, 2015). By incorporating the Australian context, this investigation contributes to a more nuanced and inclusive global discourse, highlighting how national frameworks, histories, and systemic challenges shape educational outcomes. This perspective not only enriches the international literature but also underscores the importance of localized strategies in addressing global issues of equity and inclusion. In 2018, the Commonwealth, States, and Territories in Australia agreed to raise educational outcomes as part of a new funding deal and National School Reform Agreement. A recent review of this Agreement by the Productivity Commission (2022) found that “governments are yet to achieve outcomes for students who have specific educational needs related to their culture, their disability or remoteness” (Productivity Commission, 2022, p. 30). This provides a clear mandate for revisiting issues of educational dis/advantage, including equitable teaching and learning practices that inform assessment practices in schools.

Assessment is a constellation of policies, practices, and values that intersect to provide inequitable conditions (for example, Nayir et al., 2019; Scott et al., 2014). Indeed, there is a rich body of literature that explores how educational dis/advantage intersects with assessment outcomes. In the global context the inherent inequities in standardized testing, particularly for students from minority and marginalized backgrounds whereby the assessments fail to account for the diverse cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic contexts in which students learn, thereby disadvantaging those who do not conform to the dominant culture norms that are embedded in test design and administration (Au, 2019; Sirin and Rogers-Sirin, 2020). For example, standardized tests have been shown to correlate strongly with socioeconomic status (SES), often privileging students from wealthier, predominantly White or Asian backgrounds while disadvantaging Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, and low-income students, which often results in lower standardized test scores, reduced access to advanced coursework, and limited postsecondary opportunities for these groups, hence reinforcing educational inequities (Jimenez and Modaffari, 2021). In Australia, such inequities are reflected in national standardized test scores, such as the Australian National Assessment Program—Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) and the international Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA; Cumming et al., 2012; Klenowski, 2014). It is important to differentiate between national and international assessments, as they serve distinct purposes. National assessments, such as NAPLAN, are often used for accountability and can carry high-stakes consequences for schools and students. In contrast, international large-scale student assessments (ILSAs), such as PISA, are designed to evaluate education systems rather than individual student performance. These assessments are low-stakes for students and do not influence their academic progression or school-level decisions [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2019]. The aim of ILSAs is to provide comparative data on educational outcomes across countries, focusing on group-level achievements rather than individual student results. In the Australian context, these data indicate that students from disadvantaged backgrounds, including, for example, low SES, Indigenous, and “Non-English-Speaking Backgrounds,” have significantly lower performance outcomes in standardized assessments when compared with those students who are not from non-disadvantaged backgrounds (Smith et al., 2018; Triventi et al., 2021). This systematic review explored assessment practices for educationally disadvantaged students, focusing on the use of student-centered assessment, which is considered both effective (Clark, 2014) and equitable (Alonzo, 2020).

Less is known, however, about how equitable participation in all assessments might improve learning outcomes for disadvantaged students in international contexts, and how this might inform assessment practice. This systematic literature review examines the intersection of assessment practices and equity in schools, as there is a clear justification for exploring equitable assessment practices to gain a deeper understanding that supports optimal outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students (Smith et al., 2018; Triventi et al., 2021).

Literature review

Using assessment to improve learning and teaching has strong theoretical and empirical support (Black and Wiliam, 2018; Clark, 2014; Wiliam, 2017). Teachers' assessment knowledge and skills, known as assessment literacy, require them to use a range of assessments to gather student and school data to make highly contextualized, fair, consistent, and trustworthy decisions to support individual students (Alonzo, 2016). The power of assessments used by schools in improving student outcomes lies in their ability to elicit information about students' learning characteristics, needs, knowledge, and skills, and students and teachers use this information to develop learning and teaching strategies to increase student outcomes (Curry et al., 2016).

Less is known, however, about how equitable participation in all assessments might improve learning outcomes for disadvantaged students in international contexts, and how this might inform assessment practice. Learning outcomes refer to the specific knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that students are expected to acquire through educational experiences. They are typically articulated in measurable terms and serve as a guide for curriculum design, teaching strategies, and evaluation methods and according to Prøitz (2010), learning outcomes are increasingly used to shift the focus from teaching inputs to student achievements, emphasizing what learners are expected to know and be able to do at the end of a learning process. In contrast, assessment is the process of measuring the extent to which students have achieved these learning outcomes. It encompasses a variety of tools and techniques, such as tests, projects, and observations, that educators use to evaluate student performance (Alyasin et al., 2023). Whilst learning outcomes define the goals of education, assessment provides the evidence of whether and how those goals have been met (Prøitz, 2010). The alignment between teaching methods, assessment techniques, and learning outcomes is crucial for ensuring that educational practices are effective and equitable. Understanding this distinction is particularly important when considering how assessment practices can be designed to support disadvantaged students. Equitable assessment not only measures learning but can also enhance it by making expectations transparent and providing meaningful feedback. When assessments are inclusive and aligned with well-defined learning outcomes, they have the potential to improve educational equity and inform more responsive teaching strategies (Alonzo et al., 2023).

The critical process for optimizing outcomes for individual students is the purposeful use of assessment in establishing “where the students are in their learning, where they need to go, and how best to get there” (Assessment Reform Group, 1999, p. 2). The whole notion of assessment is to use it and the information gathered to support individual students to achieve higher learning outcomes (Black and Wiliam, 2018). One of the recommendations from Black and Wiliam's (1998) seminal work is to use assessment to support low-performing students by identifying the specific support they need. This alludes to using any assessment and assessment data for equitable learning and teaching. This student-centered approach to assessment is evident in the ARG's definition above, where teachers need to work equitably with individual students. Research evidence extensively reports assessment activities that center students in the process to aid more effective learning. Strategies include sharing learning outcomes and success criteria (Clark, 2014), clarifying expectations by using exemplars (Tierney et al., 2011), providing timely and effective feedback (Hattie and Timperley, 2007), engaging in self and peer assessment, using summative assessment for formative purposes (Black, 2017), monitoring learning progress (Yeo et al., 2011), and data-driven decision making (Alonzo, 2020).

More recently, Cipriano et al. (2018), researched how a grading measure in mainstream classrooms could accurately assess students in special education settings. Students in special education settings were considered to have the lowest academic and social outcomes across both general and special education populations, exhibiting characteristics that qualitatively differentiate interactions and outcomes in assessments between teachers and students (Cipriano et al., 2018).

Despite the common understanding that assessment should support individual students, there is evidence that the implementation of assessment does not always improve student learning (Hannigan et al., 2022; Oo et al., 2022; Black and Wiliam, 2018). It is necessary to ensure that the effects of assessment on individual students are more aligned with the student-centered approach to assessment (Baird et al., 2017), wherein the focus is on helping individual students achieve better outcomes rather than only reporting the collective improvement of the cohort. Achieving better student outcomes is where the intersection of assessment and equity becomes critically important, as individual students' learning characteristics and needs become the driving force for using assessment, focusing on ensuring that all students benefit from it. Assessment practices designed to benefit students rely heavily on teacher agency and a deep understanding of individual learners. This involves the use of adaptive expertise, which encompasses the agency and ability to flexibly apply professional knowledge and skills to tailor assessment approaches based on students' unique learning needs, characteristics, required support, and sociocultural backgrounds (Tierney et al., 2011; Loughland and Alonzo, 2019). Such responsiveness enables teachers to design and implement differentiated assessment activities that are both equitable and effective. Supporting teachers to conceptualize assessment through the lens of ensuring equitable learning and teaching may be critical for developing an adaptive disposition associated with effective teaching (Clark, 2014).

Assessment in school

There has been a long history of testing among school students (Copp, 2017) to ultimately prepare them for standardized high school exit exams. Such high-stakes assessments are believed to improve student achievement and post-secondary outcomes (Holme et al., 2010). In response to external pressures to prepare students for high-stakes standardized examinations, including final exit exams, and to enhance the public profile of schools, teachers frequently align their teaching, learning, and both formative and summative in-class assessment practices with the structure and content of these exams. This alignment often results in teaching to the test and replicating the format of high-stakes assessments. Contrary to the accountability function of these high-stakes assessments, they have a significant negative impact on student learning (Glover et al., 2016) and wellbeing (Kerr and Averill, 2021), and also reduce teacher agency (Shepard, 2019). High-stakes tests have been argued to be used as a mechanism to “deny structural, racialized inequalities” (p. 39), and yet it is claimed that they widen inequalities in education (Smith et al., 2018). The participation and success of disadvantaged students in exit exams have been documented. Many different groups of educationally disadvantaged students have lower success outcomes with exit exams (Uretsky and Stone, 2016).

There is evidence that using classroom assessments to inform learning and teaching decisions and guide high-stakes decisions about teacher effectiveness can best meet the external accountability measures (Glover et al., 2016). When teachers use classroom assessment and data to inform instruction, it is suggested that they become reflective, which develops their autonomy and competence, thereby ensuring higher learning outcomes for students (Curry et al., 2016). Thus, classroom assessments are argued to be an important driving force to improve student learning (Black and Wiliam, 2018), which may prepare school students for standardized high-stakes or exit exams to support further study or work.

From this brief review of the scholarly literature, there is a clear justification for exploring the international literature on what is known about equitable assessment practices to improve educational outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students. To this end, we conducted a systematic review of the literature, guided by the following Research Questions (RQs):

RQ1: What assessment practices have made a difference in improving the educational outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students?

RQ2: What does the international literature say about assessment practices used to support educationally disadvantaged students?

RQ3: What factors are reported in the international literature as impacting the effectiveness of assessment practice that improves educational outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students?

Methodology

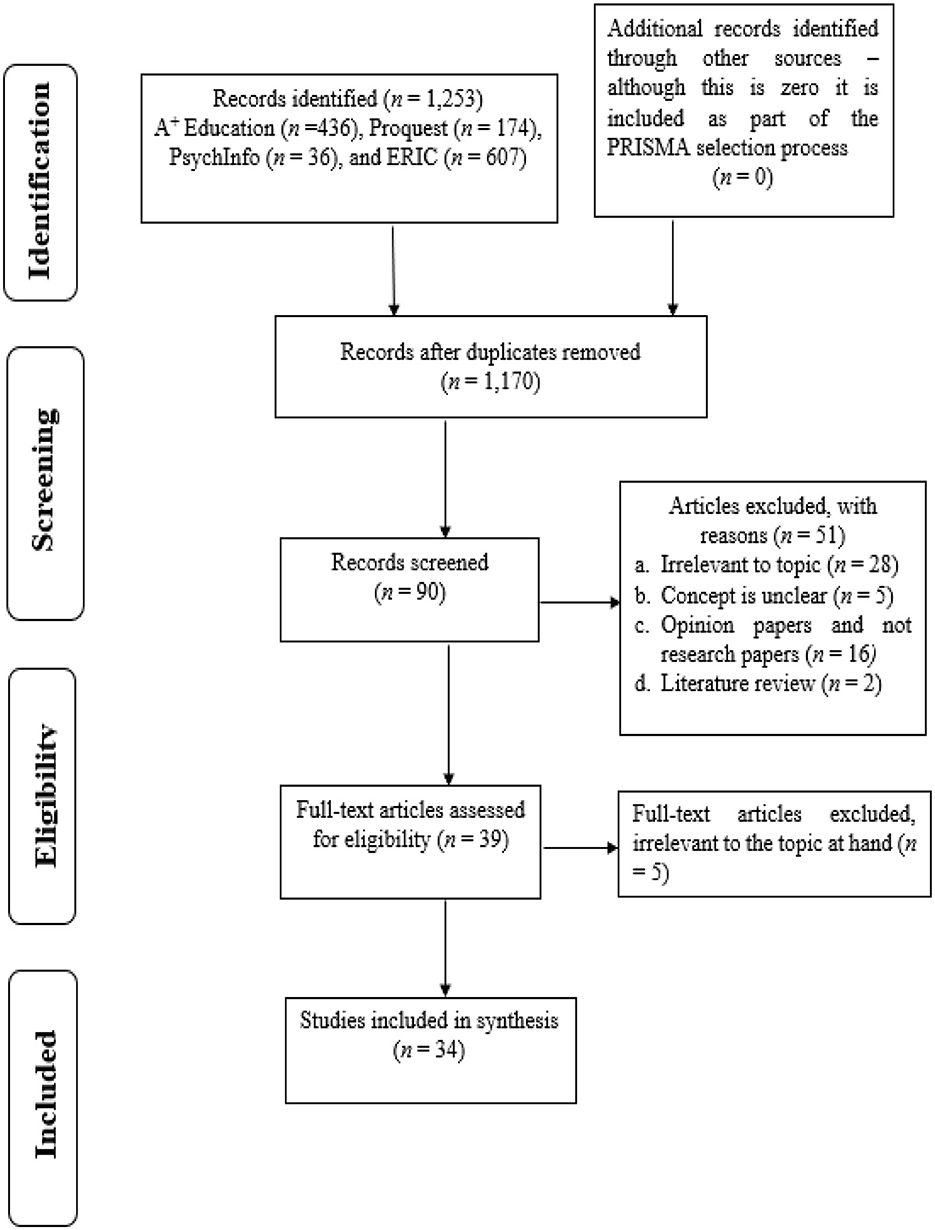

To explore the type of research undertaken into equitable assessment practices with educationally disadvantaged students attending middle and/or secondary schools, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used (Moher et al., 2009). These guidelines provide a framework for identifying peer-reviewed journal publications that report on assessment practices recognized as improving educational outcomes for students identified as being educationally disadvantaged. PRISMA is the widely used basis for reporting literature reviews that follows a series of logical steps, see Figure 1, that involve identifying the research literature from database searches, to screening articles using inclusion and exclusion criteria, to assessing full-text articles for eligibility and coding, and for reporting the final articles included in the review.

Data sources and literature search

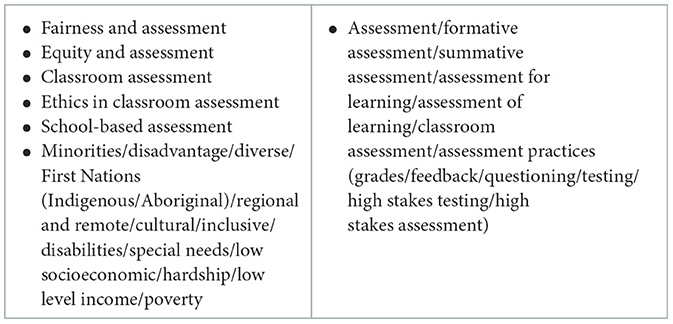

To undertake the literature search, the following databases were selected: A+ Education, ProQuest, PsycINFO, and Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC). As the literature search was based on the discipline of education, these databases were selected because they contain a large number of education journals held by university libraries. The notions of fairness and equity are broad in the body of international literature, and an examination of many possible search terms for the systematic literature review was required to best capture the scope of fairness, inequity, and disadvantaged students. As the language of educational disadvantage varies across countries, the search terms used reflect an appreciation of this linguistic diversity and therefore the search is comprehensive rather than exhaustive.

The combination of keywords included in Table 1.

Initially, studies were extracted using the combinations of these key search terms. There were no restrictions (e.g., qualitative, quantitative) regarding the design of studies; therefore, all types of scientific and naturalistic studies were included. In addition to database searches, hand-searching was conducted to identify further relevant studies. This process included perusing the key journal pages and checking references of identified articles, then removing duplicates from the list. Finally, opinion articles and literature reviews were removed as the focus was on empirical research articles, which removed 1,170 papers.

Selection criteria

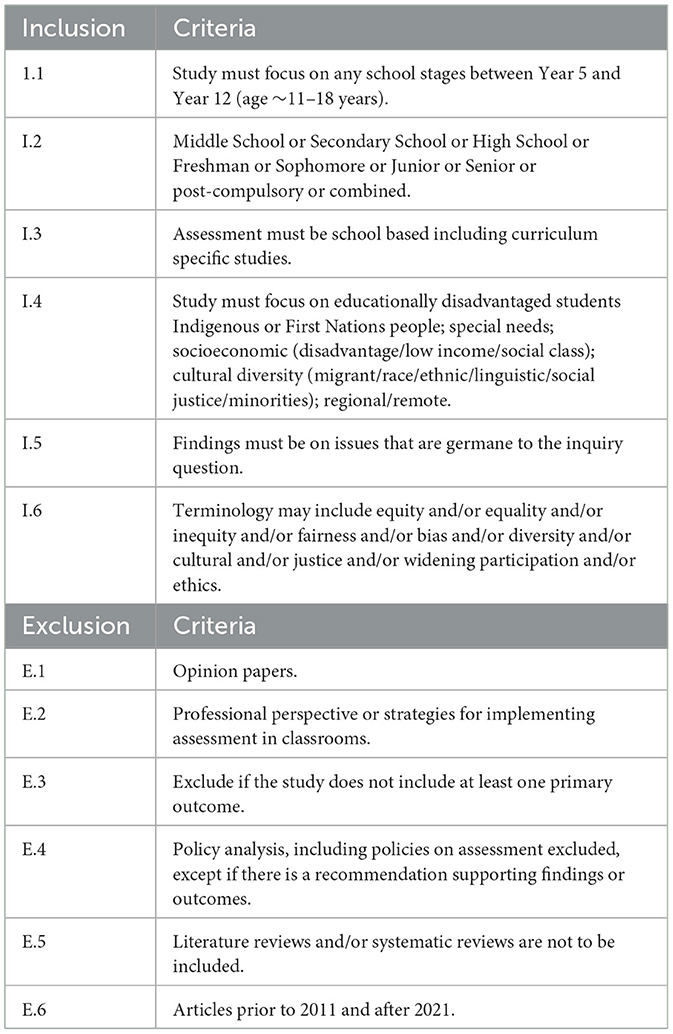

The titles and abstracts of articles extracted from the four databases were read and the inclusion/exclusion criteria in Table 2 were applied. All articles included were peer-reviewed articles.

Once the searches of articles from 2012 to 2020 were complete, the identified studies were exported to an Excel document in order of year published, capturing the following descriptive information: Year; Publication Details; Author/s; Article Title; Abstract; Aim of the Study; Keywords. We also captured details such as terminology, country context, educational context, data source, research design, subject domain, data collection, sample size, assessment, factors influencing assessment to increase student outcomes, outcomes reported, recommendations, and inclusion.

The lead author read the papers and applied the criteria, and only 90 papers were deemed relevant. For rigor, two members of the research team (authors 2 and 3) also independently read all of the individual articles and assessed their relevance to the aims of the literature review. The whole research team discussed the inclusions in terms of their fit and papers that did not relate to the focus of inquiry were excluded for final analysis and synthesis.

Approach to synthesis

We undertook three stages of thematic synthesis, as proposed by Thomas and Harden (2008): (i) coding text: the line-by-line coding; (ii) developing “descriptive” themes; and (iii) generating analytical themes. The descriptive and analytical themes developed by three members of the research team (authors 1, 2, and 3) and were then checked by the 4th author. To ensure rigor and consistency, the coding began with three research team members independently coding 20 of the same two articles and later comparing the results of their coding. They then worked in pairs to review the remaining articles and author 4, then independently checked all articles for analysis and themes. Any inconsistencies were discussed over a maximum of five iterations to reach consensus.

Approach to analysis and presentation of findings

The final 34 articles were analyzed using an inductive coding paradigm, employing three levels of coding to generate themes around core categories (Strauss and Corbin, 1998): open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. The sub-themes informed the three assessment practices that are presented in the findings: first, inclusive assessment design and feedback practices; second, school approaches to assessment; and third, approaches to grading. The data was then addressed through the lens of the research questions in the discussion section and apportioned to a theme based on the main theme of the article, as listed in Table 2 in the Appendix.

Findings

These findings are derived from our analysis of the 34 publications that explored participation in assessment, which directly or indirectly influence learning outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students.

Inclusive assessment design and feedback practices

This section answers our Research Question 1: What assessment practices have made a difference in improving the educational outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students?

Social justice notions of accessibility are a key theme in the literature. For instance, (Murillo and Hidalgo 2017) report that students believed fair assessment should involve diversification of tests, qualitative assessment and include student effort and attitudes. Perceptions of fair assessment can enhance outcomes for students, but lower performance outcomes remain unresolved when comparing disadvantaged students with those from non-disadvantaged backgrounds (Triventi et al., 2021). Three subthemes were identified within the theme of assessment design and practice: culturally responsive assessment, accessibility, and feedback.

Culturally responsive assessment

The first subtheme centered on culturally responsive assessment, highlighting how standard assessments often lack cultural fairness for students from marginalized backgrounds. The term culturally responsive assessments is used interchangeably for the purposes of this article with culturally fair assessments, as to be fair, the assessment must be responsive (Abedi, 2020). Culturally fair assessments must minimize linguistic and cultural biases to ensure validity for diverse student populations, take into account the cultural backgrounds and needs of students from non-dominant cultures. The studies in this review indicate that teachers, schools, and school districts need to consider the non-dominant cultures within their context and use culturally relevant practices to bridge the inequities evident in the research on educationally disadvantaged students.

Culturally fair assessment using equitable assessment and design practices in the United States (Mark et al., 2020) were found to be necessary for cultural minority students (students from the non-dominant culture) to have opportunity to enhance academic outcomes (Tomlinson and Jarvis, 2014) and included, for example, assessments in the non-dominant language of the culture, or locally designed assessments that reflect the understanding and practices of the non-dominant culture (Kang and Furtak, 2021). This notion was supported by Canadian research, which found that culturally fair assessment was also supported through learning and classroom interactions that provide deeper understandings, leading to enhanced student outcomes (Rasooli et al., 2018). Snow et al. (2021) explored culturally responsive assessment in Inuit Nunangat, Canada, with teachers, students, administrators, and Elders who collectively highlighted the challenges and achievements in developing culturally responsive and fair assessment practices that reflected Indigenous culture and values. Findings indicated that the shift from Eurocentric to Inuit-centric assessments enhanced success and engagement outcomes for educationally disadvantaged Inuit students. The study also recommended developing lessons, workbooks, and assessments with support from Inuit Elders, encouraging regular attendance, allowing flexible submission dates, and incorporating alternative assessments that reflect Inuit culture (Snow et al., 2021).

Exploring the notion of culturally fair assessment with migrant students in Austria, Ireland, Norway, and Turkey, Nayir et al. (2019) found that, despite a significant promotion to support diversity in schools, assessment for culturally diverse students was inadequate due to lack of knowledge by educators, bias, and, in most cases, professional development was required, as these all contribute to educators' understanding around supporting diversity (Mark et al., 2020). Building upon this work in a Canadian study, Parekh et al. (2021) found that, in a study of 7,648 students, inequities existed in the reporting of learning skills, particularly for students from cultural minorities and educationally disadvantaged groups. Inequities were due to implicit bias within teacher-generated assessments (which were assessments created by the teachers) as a result of dominant culture bias. Newkirk-Turner and Johnson (2018) presented findings from the United States highlighting linguistic and content bias in Curriculum-Based Language Assessment (CBLA) used to evaluate mathematical abilities in EAL/D students. For instance, some assessments included culturally specific language, culturally specific knowledge (such as culturally specific games or scenarios) or idioms unfamiliar to these students, and referenced experiences not commonly shared across diverse cultural backgrounds, thereby disadvantaging them despite their mathematical competence. The findings indicated that the assessments had linguistic and content bias that did not accurately reflect the true mathematical abilities of EAL/D students.

Accessibility

Accessibility, the second sub-theme emerging within the first theme, focused on students' equitable access to assessment. Access includes the demonstration of knowledge and skills, or the [in]equitable opportunities to demonstrate knowledge and skills. As assessment can often drive learning approaches, as Acar-Erdol and Yildizli (2018) found in a study in Turkey, traditional assessments that do cater for educationally advantaged students (such as those students from the dominant culture, native language speakers, are able-bodied, come from more wealthy SES contexts, and from a home that values education) are often favored to measure growth despite the disservice to educationally disadvantaged students. Modell and Gerdin (2021) explored Swedish students' experiences and perceptions of the accessibility of physical education assessment. Findings indicated that assessment was shaped more by the norms and values of competitive club sports rather than those outlined by the equity-based policies, emphasizing the disadvantage that “non-athletic” students would face in this subject. In an Indonesian study, student perspectives of fairness in assessment highlighted the need for transparency, educational adjustments for individuals and the pursuit of accuracy with marking across large-scale summative assessments (Nurhayati and Herman, 2020).

Focusing on disability, Rasooli et al. (2021) found that equitable access to the curriculum is essential for fair assessment in Australia. Similarly, Herzog-Punzenberger et al. (2020) reported findings from Austria, Ireland, Norway, and Turkey, highlighting the importance of accessibility for students who are non-native speakers, particularly in culturally diverse classrooms. The primary barrier to accessibility was the language used in both instruction and assessment, which often hindered students' ability to engage fully. In many cases, teachers responded with individualized, ad hoc strategies to accommodate the diverse needs of their students. In addition to language, Dupont (2018) found that formative assessment played a crucial role in ensuring fair and equitable access to the curriculum for French middle school students with specific learning disorders in reading. The use of didactic workstations, designed to clarify teaching content and support formative assessment practices, enhanced learning accessibility by fostering a greater sense of equity and inclusion.

The relevance of equitable access and the importance of linking both formative assessment (used to adapt instruction for improved outcomes), and summative assessment (used to assign grades or outcomes) was emphasized in Shepard's (2019) research. Rather than promoting coherence in assessment through the alignment of approaches such as culturally relevant pedagogy, standards-based instruction, technology, and assessment, which are often viewed as complementary and supportive of teachers' understanding of student learning, Shepard (2019) argued that standardized testing can undermine the learning-focused aims of formative assessment. She instead suggested that coherence should be achieved through teaching practices that are responsive to the specific educational context, which can help mitigate some of the negative effects that grading has on student learning. Graham et al. (2018) argued that assessment design practices in Australia can unintentionally create barriers for students with disabilities. For example, they noted that rigid assessment formats often fail to accommodate students with diverse cognitive or physical needs, such as requiring handwritten responses from students with motor impairments. In the Canadian context, Tierney (2014) highlighted similar concerns around equity and access, emphasizing the importance of offering multiple ways for students to demonstrate their learning. This included alternatives like oral presentations or project-based tasks, which can be more inclusive than traditional written exams. Murillo and Hidalgo (2017), examining the Spanish context, also found that equitable assessment should provide varied opportunities for students to show what they know, particularly in linguistically and culturally diverse classrooms. Applying a social justice lens, Klenowski (2014) focused on First Nations students in Australia and advocated for assessments that are culturally inclusive and unbiased. She emphasized the value of incorporating community knowledge and oral storytelling as valid forms of assessment.

Scott et al. (2014) recommended differentiated assessment practices to support educationally disadvantaged students. Their research showed that modifying assessment tasks, such as simplifying language or allowing extended time, can significantly improve outcomes for students with learning difficulties. However, most of the articles reviewed recommend professional learning for teachers as necessary to increase accessibility and, therefore, equity for minority students. Additionally, in Canada, Marynowski et al. (2019) found that one of the key principles to support teachers with fair assessment is the close proximity of and active support by school leadership, alongside collaboration with colleagues, to create and implement accessible assessment practices.

Feedback

Feedback emerged as the third and smallest sub-theme. This concept encompasses various forms of feedback, including student-led, formative and summative feedback, and feedback used to inform instructional planning. A study conducted in New Zealand found that student-led feedback, where students actively engaged in formative feedback processes, enhanced self-regulation and academic achievement, particularly in low socioeconomic contexts. These outcomes were measured using peer- and self-assessment strategies (Harris et al., 2015; Holme et al., 2010). Building on this work, Charteris (2015) further explored the experiences of educationally disadvantaged students in New Zealand and found that students perceived peer, group, and self-assessment as mechanisms that increased their sense of agency and contributed to improved academic outcomes. These findings align with those of Nortvedt et al. (2020), who also emphasized the value of student agency in assessment. In response to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Barana et al. (2021) investigated the use of automated, interactive feedback in mathematics. Their findings indicated that automated, interactive feedback was particularly effective in enhancing engagement and academic performance among educationally disadvantaged students. Although this contrasts with earlier research on feedback (e.g., Charteris, 2015; Harris et al., 2015), the unique context of pandemic-related disruptions in schools may explain these differences.

Insights about equitable assessment practices

This section answers our Research Question 2: What does the international literature say about assessment practices used to support educationally disadvantaged students?

Two broader themes emerged: school-based assessment and approaches to grading. Each of these themes is discussed below.

School-based assessment

The theme of school-based assessment was dominant in seven of the publications. Three main strategies that emerged within the approaches of school-based assessment were assessment measures, assessment systems within school contexts, and modes of assessment. Each will be considered within the frame of assessment for educationally disadvantaged students.

Assessment measures

The first concept, assessment measures, encompassed formative assessment along with other evaluative approaches. Kang and Furtak (2021) recommended that school-based assessment shift its focus from formalized tasks to classroom-based activities, particularly to better support educationally disadvantaged students. However, they also noted that teachers need greater support in designing and implementing formative assessments effectively to address equity more comprehensively. One study by Rahman et al. (2021), after working with Year 8 mathematics classes in 12 secondary schools, found that school-based assessment included insufficient formative assessment to adequately inform learning outcomes for disadvantaged students. Findings indicated that formative assessment was not implemented in schools for several reasons, such as teachers' negative attitudes, perceived large workloads, lack of recognition of results in public examinations, and the lack of transparency to ensure equity (Rahman et al., 2021). Chen et al. (2012) conducted a similar study with Grade 8 mathematics teachers exploring discourse-based formative assessment to bridge socioeconomic equity gaps between schools. Findings accentuated the qualitative differences between high and low SES classrooms, the former being diligent about formative assessment and pressing for deeper understanding, and the latter focused more on rote learning.

Assessment systems within school contexts

The second facet of this theme that emerged was the significance of the type of assessment system adopted in a school context. Barrance (2019) investigated how a national assessment system should be controlled within schools. Survey results from 1600 students indicated that the high focus on authentic authorship by students neglected other aspects of fairness such as accessibility and consideration of “best work.” The use of internal assessment with the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), found that the assessment environment, which varies in different contexts, had implications for [in]equity (Barrance, 2019). Coles-Richie and Charles (2011) considered the “westernization” of assessment systems that did not align with equitable assessment in rural schools. Inequity within a national assessment system, particularly affecting Indigenous students, was addressed in part by teachers combining their contextual knowledge with authentic assessment (Coles-Richie and Charles, 2011). Therefore, to cater for educationally disadvantaged students, particularly within larger systems, it is recommended that the focus is diversified to include, alongside the notion of “best work,” the environmental context (such as being urban/dominant-culture centric assessment), and contextual knowledge.

Modes of assessment

The third sub-theme that emerged was the modalities of assessment used with disadvantaged students, which included multimodal assessment that uses a variety of technologies. Stevens and Van Houtte (2011) explored adaptations of modalities of assessment within multicultural secondary schools, and findings indicated that all teachers adapted their expectations and assessment approaches in line with the perceived ability of the students due to the scarce allocation of resources. Many teachers believed they were unable to adjust assessment practices in line with ability and interests, and that disadvantaged students would, therefore, obtain a lower status qualification. However, some teachers perceived that they could adjust assessments to a lower standard that would meet other criteria, reflecting “attitude to learning” rather than ability, and in which disadvantaged students would experience more success. This approach, however, raises fairness and reliability issues. Cumming et al. (2012) looked at how a multimodal focus on assessment in Australia could provide more opportunities for feedback from students to each other, alongside their teacher feedback, to enhance engagement. Findings indicated that when multimodal technology is implemented (the student engagement with technology, virtual worlds and other modal literacies), the learning is greater, and that the needs of educationally disadvantaged students are more often met.

Approaches to grading

Grades have long-term consequences for students and influence self-concept and educational outcomes (Rowan and Townend, 2016). When considering the literature around grading, different practices made a noteworthy contribution to the results. The notion of fairness in grading and the interpretation of achievement is questioned as a universally equitable process (Tierney et al., 2011). Additionally, the use of learning theory is explored to enhance the effectiveness of assessment practices, and the co-design of assessments is examined for its impact on the outcomes of minority students (Kang and Furtak, 2021).

Fairness in grading

Tierney et al. (2011) reviewed how secondary teachers determine students' grades within a standards-based system (one that has a centrally developed curriculum and a common grade outcome). Findings indicated that teachers were influenced by their notions of fairness and, as a result, grades were often based on work completion rather than non-achievement factors such as attitude to learning, leading to inconsistent grading practices. Although this study (Tierney et al., 2011) did not aim to address the issue of “fairness,” it emerged that “fairness” in grading was central for teachers despite misunderstandings and incorrect assumptions, and that teachers would benefit from professional development that includes guidance that focuses on assessment principles. Yeo et al. (2011) also investigated how teacher bias around student background (special education, gender, and income) influenced grading in a study of students from Grades 3 to 6. Findings indicated that for those disadvantaged students who were identified as such through one of the three categories (special education, gender, and income), gender was particularly influential in that male students had higher grading estimates.

Tierney et al.'s (2011) empirical research to determine how teachers awarded grades, offered six recommendations to support teachers to better understand essential principles of assessment so that educationally disadvantaged students benefit. Firstly, results from multiple assessments should be carefully weighted and calculated to reflect learning expectations and encapsulate achievement. Secondly, teachers should create clearer definitions to communicate the expectations of assessment for increased consistency. Thirdly, principles for assessment (generally accepted but abstract guidelines for what should be done) should be enshrined in policy so that optimal consistency can be achieved. Fourthly, adequate professional development and guidance to support teachers' development of professional judgment should be regularly provided. Fifth, teachers should use multiple student progress measures to address special education status and gender bias (see Yeo et al., 2011). Finally, teachers of students who are educationally disadvantaged as a result of diagnoses should use an assessment tool that is specific for special education populations and is used to provide equity in grading for these educationally disadvantaged students (see also Cipriano et al., 2018). An example of such an assessment tool is the “RELATE Tool for Special Education Classroom Observation” which was developed to evaluate the quality of instruction and learning environments in special education settings and supports equity in grading by offering structured, reliable observations that account for the unique needs of students with disabilities. For instance, it allows educators to assess classroom interactions, instructional strategies, and student engagement in ways that are tailored to the diverse learning profiles found in special education classrooms (Cipriano et al., 2018).

Factors impacting the effectiveness of assessment

This section answers our Research Question 3: What factors are reported in the international literature as impacting the effectiveness of assessment practice that improves educational outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students?

From our review of the literature, five broad factors or themes emerge that appear to influence the use of assessment for improving the educational outcomes of disadvantaged students, each accompanied by recommendations to ensure fairness. These include assessment design, assessment processes, teachers' assessment dispositions, knowledge and skills, and policy.

Assessment design

Any assessment must be designed to provide students with opportunities to demonstrate their learning (Kang and Furtak, 2021). A one-size-fits-all design does not capture individual students' learning, ideas, and experiences. Assessment should be culturally and linguistically appropriate for a more valid assessment of diverse students (Newkirk-Turner and Johnson, 2018). This requires adapting the curriculum resources to make them familiar to students and then developing a culturally congruent assessment (Coles-Richie and Charles, 2011).

One way to ensure effective assessment design is by aligning assessment practices with learning theory (Kang and Furtak, 2021). Assessments must be equity-driven assessments (Mark et al., 2020), focusing on supporting individual students and providing greater access and support for disadvantaged students. Accessible assessment needs to consider not only accessible design elements but also learners' experiences, which is central to the definition of fair assessment. Assessment tasks are invitations to students to demonstrate their mastery of new understandings; however, these invitations must be evaluated in terms of the affordances they provide for different learners and whether learners can transform those affordances into action (e.g., Baird et al., 2017; Graham et al., 2018).

Assessment processes

The way assessments are implemented influences their effectiveness, which highlights the importance of procedural fairness by ensuring accessibility for students with disability (Rasooli et al., 2021), as free as possible from potential bias (Parekh et al., 2021), transparent, and consistent (Nurhayati and Herman, 2020). Dialogic approaches are also valued in the literature, with interactive and guided feedback found to better support disadvantaged students (Barana et al., 2021). Through dialogue, students can ask for clarification, and teachers have better ways of assessing if students have understood the feedback given. Relatedly, Charteris (2015) found that students find peer and group assessment easier than self-assessment. Through a dialogic approach to feedback, students can judge their learning (self-assessment). Students' engagement in peer assessment conversations activates each other's learning. In addition, refining in-the-moment questioning techniques to elicit students' understanding of the content taught and providing immediate feedback is effective in raising student outcomes (Chen et al., 2012).

Teachers' dispositions, knowledge, and skills

Teachers' understandings of, and dispositions toward the principles of effective assessment (Rahman et al., 2021) and positionality in the classroom (Parekh et al., 2021) are important factors in ensuring the effectiveness of their assessment practices. In addition, teachers' understandings of the role of fair and balanced assessment practices for enhancing student learning at their school are critical for implementing equity-driven assessment practices (Marynowski et al., 2019). Teachers need to modify these concepts not only to make appropriate adjustments but to enhance opportunities and outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students based on their individual needs (Rasooli et al., 2021).

By teachers adapting assessment and grading procedures, educationally disadvantaged students can be better supported to demonstrate their competencies and to experience success (Herzog-Punzenberger et al., 2020). Teachers need support to recognize the factors that influence students' learning (Acar-Erdol and Yildizli, 2018), including the influence of social factors, such as the influence of a negative peer group, lack of family support, or immigration (Stevens and Van Houtte, 2011). This may involve some advocacy as Coles-Richie and Charles (2011) have argued.

Policy

Positioning assessment policy as a key aspect in curriculum implementation promotes the role of assessment in supporting student learning (Nayir et al., 2019). As Herzog-Punzenberger et al. (2020) found, school policies greatly influence teacher implementation of culturally responsive assessments. These findings advocate for better informed policy practices that enable self-regulation versus practices that rely on extrinsic motivation (Shepard, 2019). Policymakers need to understand that assessment for accountability does not support learning and teaching. In addition, policymakers need to provide a supporting mechanism for teachers to understand the policies. The intent behind assessment policies may only become evident when teachers understand the underlying philosophy; otherwise, they may continue to rely on outdated practices, as demonstrated in the empirical work of Tierney et al. (2011).

Discussion

Researchers have long argued that the use of assessment can improve learning and teaching (Black and Wiliam, 2018; Clark, 2014; Wiliam, 2017). However, equitable assessment practices for educationally disadvantaged students to enhance outcomes remain, to some extent, unresolved, and lower performance outcomes are evident when compared with those from non-disadvantaged backgrounds (Triventi et al., 2021). This systematic review of the literature highlights some insights into the intersections between equity and assessment. However, this relationship is not always explicitly addressed in the framing and writing of research.

This review highlights the commonalities across assessment practices, starting with increased attention to culturally responsive approaches to assessment, especially for First Nations peoples (Coles-Richie and Charles, 2011; Klenowski, 2014; Snow et al., 2021) and with culturally and linguistically minoritized students (Nayir et al., 2019; Parekh et al., 2021; Triventi et al., 2021). That such assessment practices (such as non-dominant culture languages used in assessment, and culturally contextualized values and knowledges incorporated into assessments), are prominent in the international literature speaks powerfully to educators in colonial-settler contexts like Australia, where First Nations Australians are significantly disadvantaged by education systems that are not only western/euro-centric but have actively marginalized Indigenous ways of teaching and learning (Whatman and Singh, 2015). Given the trajectory of colonial-settler countries without a treaty with their Indigenous citizens, like Australia, these international findings about culturally responsive practices to teaching and assessment are not new in the literature; however, they remain largely unaddressed (Whatman and Singh, 2015).

Further facets of the inclusive assessment theme illustrate the utilitarian value of adopting accessible and diverse practices across a range of national and school contexts and subject areas. Such accommodations, which encompass effective teaching and learning practices, student wellbeing, student voice, assessment knowledge, pedagogical rationality, and stakeholders' attitudes around inclusion, “that relate to inclusion, special needs, exceptionalities (e.g., giftedness), as well as, for all students in the classroom” (Scott et al., 2014, p. 53), offer insights around strengthening advocacy for more equitable assessment and flexibility (Scott et al., 2014; Marynowski et al., 2019). Deliberately designing assessment and supports to be inclusive of students who sit outside of normative classifications (“native”-born/language speaker; able-bodied; materially stable; from a family that understands and values education) may assist in removing assumptions and implicit biases, resulting in practicable differentiation to the benefit of all students as a result of individual learning needs being addressed (Tierney et al., 2011). This approach is also supported by several national and international policies on inclusive education (UNESCO, 2020).

Student factors that influence the effectiveness of assessment include the clarity of student responsibilities and fulfillment of expectations (Dupont, 2018); a positive disposition toward using assessment to support their learning (Murillo and Hidalgo, 2017); and perceptions of fair assessment practices. When students feel that they are fairly treated with respect and sensitivity, especially if they are experiencing difficulties that require modifications, they perform better (Scott et al., 2014).

Other assessment practices that emerged as significant for equitable assessment foreground the agency of individuals (teachers, school leaders) and school culture to shift perceptions about what equitable assessment can do to enhance learning outcomes for educationally disadvantaged students. The significance of school-based assessment practices lies in how educators' understandings of the purpose and value of assessment shape the messages schools convey and the ways they implement assessment. These practices can pose challenges to equity, particularly when assessment regimes are externally imposed rather than developed within local contexts. Barrance's (2019) analysis of the internally graded component of the English General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) exam highlights the difficulties in achieving equitable assessment at scale. At another level, teachers' understandings, practices, and modes of assessment can have significant implications for equitable engagement, particularly when it comes to grading. Issues relating to teachers' understandings of “what counts” (Tierney et al., 2011), teachers' understandings of cohort-specific needs (Cipriano et al., 2018), and teacher bias (Yeo et al., 2011) are all shown to impact equitable assessment practices.

Where strategies (RQ2) exist, or recommendations are made, certain caveats need to be made. The effectiveness and transferability of the identified assessment practices (RQ1) depend on the context (RQ3). These practices are situated, therefore not “one-size-fits-all” and are wholly reliant on safe conditions (appropriate policies, developed equitable assessment culture, clear leadership) and resources (principally time, training, and processes and protocols that can be shared and refined) being available. For instance, as Rahman et al. (2021) research indicates, that without sufficient buy-in from teachers (stymied by workload constraints, negativity, and a lack of valuing or recognition), equitable assessment can get dropped in the “too-hard basket.” Moreover, while clear and repeated connections are made to social justice imperatives for engaging with equitable assessment (Tierney, 2014; Klenowski, 2014; Murillo and Hidalgo, 2017), and an appreciation of the need to understand the diverse needs of our school cohorts (Newkirk-Turner and Johnson, 2018), these alone cannot ensure the uptake, nor the effectiveness of the assessment practices and strategies discussed in response to RQs 1 and 2.

What is not clear from this review but is clear from our observations of working with schoolteachers in the Australian context, is that teachers enact assessment practice inconsistently and in situ, often without adequate training or support, and are therefore effectively interpreting national/state/department/school policies at “the chalk face” (Graham et al., 2018). This situation is entirely unacceptable and demonstrates a clear lack of oversight at higher levels (international, national, and state; Shepard, 2019; Rahman et al., 2021). What is evidently needed to facilitate effective and equitable assessment that addresses issues of educational disadvantage is clear policy, school autonomy to make cohort-specific decisions, consistent leadership, regular opportunities for professional development, and clear guidelines, as indicated by the lack of research identified in this review.

Establishing a school assessment culture is important for the effectiveness of assessment practice. Coles-Richie and Charles (2011) emphasize the development of a community of learners where teachers develop a shared consciousness through readings and dialogues about decolonizing educational policies that fail disadvantaged students. At the classroom level, establishing classroom norms, also known as a didactical contract, enables students to become central participants in the assessment process (Nortvedt et al., 2020), thereby providing a constructive and supportive classroom environment (Nurhayati and Herman, 2020). This classroom environment empowers them to take an active role in their learning. Contextual factors that negatively influence the effectiveness of assessment include heavy workloads, large class sizes, extensive syllabus content, and misalignment between classroom assessment practices and national examinations (Rahman et al., 2021).

Support from school leaders plays a vital role in fostering a positive school culture and is critical for implementing effective assessment practices. This support is especially important in creating safe environments where teachers feel encouraged to experiment with assessment strategies that best support disadvantaged students (Marynowski et al., 2019). Additionally, teachers benefit from school leaders who actively monitor and guide assessment practices, helping to identify areas where teachers may need further support (Rahman et al., 2021).

Another aspect that impacts teachers' preparation is the initial teacher education curriculum. Advancing teacher assessment knowledge requires embedding assessment practices in teacher education programs (Scott et al., 2014). Besides generic understandings, principles, and practices of using assessment to support learning, teachers need to develop theoretical knowledge and practical skills for equitable teaching and assessment processes (Modell and Gerdin, 2021).

Conclusion

Despite strong policy commitments to both equity and assessment, this review reveals a notable lack of empirical research on equitable assessment practices over the past decade. This was a surprising finding given the long-term research evidence that has repeatedly identified the educational underperformance of certain groups of students, as identified in this article. This review has also highlighted a significant gap in the research literature, particularly regarding assessment practices among secondary education students. Given the significance of assessment in the learning and teaching cycle, it is concerning that more research has not focused on this area, and that the education sectors themselves have not funded or requested a closer examination of the issues.

For students from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, those with disabilities, and others facing educational disadvantage, equitable assessment requires a more inclusive and responsive approach to classroom practice. This review revealed a concerning gap: inadequate teacher understanding of assessment may partly explain the limited implementation of equitable practices identified in the literature. Although policy documents frequently emphasize the importance of assessment, there appears to be insufficient attention to how these policies are enacted in both research and practice. Greater emphasis is needed on developing and disseminating recommended assessment strategies that promote fairness and inclusivity. Adjusting assessment practices to better support educationally disadvantaged students in demonstrating their knowledge and skills is long overdue. To address this, assessment should be a stronger focus throughout all stages of teacher development, including initial teacher education and ongoing professional learning. Professional bodies such as the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) could play a key role in embedding equitable assessment practices into national teaching standards and accreditation processes.

In terms of the international scope of this review, several limitations must be acknowledged. A clear geographic trend emerged, with the majority of studies originating from Anglophone countries—specifically the United States (8 of 34), Canada (6), Australia (3), and New Zealand (2). Only four studies were identified from Asian countries (Taiwan, Bangladesh, Iran, and Indonesia), and none from Africa or Latin America. This trend may indicate that the intersection of assessment and equity is under-researched in non-Anglophone contexts. However, it may also reflect a limitation of the review itself, as only English-language articles were included. This language restriction may have introduced a bias toward Anglocentric perspectives, potentially overlooking valuable insights from other cultural and educational contexts. Future reviews should consider including non-English literature and expanding database searches to capture a more globally representative understanding of equitable assessment.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1536485/full#supplementary-material

References

Abedi, J. (2020). The validity argument for assessments of English learners: a conceptual framework. Educ. Measure. Iss. Prac. 39, 20–30. doi: 10.1111/emip.12267

Acar-Erdol, T., and Yildizli, H. (2018). Classroom assessment practices of teachers in Turkey. Int. J. Instruct. 11:587. doi: 10.12973/iji.2018.11340a

Ainscow, M. (2020). Inclusion and equity in education: making sense of global challenges. Prospects 49, 123–134. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09506-w

Alonzo, D. (2016). Development and Application of a Teacher Assessment for Learning (AfL) Literacy Tool. Sydney, NSW: University of New South Wales. Available online at: http://unsworks.unsw.edu.au/fapi/datastream/unsworks:38345/SOURCE02?view=true

Alonzo, D. (2020). “Teacher education and professional development in Industry 4.0: The case for building a strong assessment literacy,” in Teacher Education and Professional Development in Industry 4.0, eds. Ashadi, J. Priyana, Basikin, A. Triastuti, and N. H. P. S. Putro (Taylor & Francis Group).

Alonzo, D., Baker, S., Knipe, S., and Bottrell, C. (2023). A scoping study relating Australian secondary schooling, educational disadvantage and assessment for learning'. Issues Educ. Res. 33, 874–896. Available online at: http://www.iier.org.au/iier33/alonzo.pdf

Alyasin, A., Nasser, R., El Hajj, M., and Harb, H. (2023). Assessing learning outcomes in higher education: from practice to systematization. TEM J. 12, 1593–1604. doi: 10.18421/TEM123-41

Assessment Reform Group. (1999). Assessment for Learning: Beyond the Black Box. Available online at: https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/beyond_blackbox.pd (Accessed August 2, 2023).

Au, W. (2019). High-stakes testing and curricular control: a qualitative metasynthesis. Educ. Policy 33, 423–446. doi: 10.1177/0895904817691844

Baird, J.-A., Andrich, D., Hopfenbeck, T. N., and Stobart, G. (2017). Assessment and learning: fields apart? Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Prac. 24, 317–350. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2017.1319337

Barana, A., Marchisio, M., and Sacchet, M. (2021). Interactive feedback for learning mathematics in a digital learning environment. Educ. Sci. 11:279. doi: 10.3390/educsci11060279

Barrance, R. (2019). The fairness of internal assessment in the GCSE: the value of students' accounts. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Prac. 26, 563–583. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2019.1619514

Berger, E., Baidawi, S., D'Souza, L., Mendes, P., Morris, S., Bollinger, J., et al. (2023). Educational experiences and needs of students in out-of-home care: a Delphi study. Euro. J. Psychol. Educ. 39, 689–710. doi: 10.1007/s10212-023-00714-4

Black, P. (2017). “Assessment in science education,” in Science Education: An International Course Companion, eds. K. S. Taber and B. Akpan (Rotterdam: SensePublishers), 295–309. doi: 10.1007/978-94-6300-749-8_22

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. Principles Policies Prac. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assess. Educ. Principles Policies Prac. 25, 551–575. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2018.1441807

Cairney, P., and Kippin, S. (2022). The future of education equity policy in a COVID-19 world: a qualitative systematic review of lessons from education policymaking. Open Res. Europe 1:78. doi: 10.12688/openreseurope.13834.2

Charteris, J. (2015). Learner agency and assessment for learning in a regional New Zealand high school. Aust. Int. J. Rural Educ. 25, 2–13. doi: 10.47381/aijre.v25i2.12

Chen, C., Crockett, M. D., Namikawa, T., Zilimu, J. A., and Lee, S. H. (2012). Eight grade mathematics teachers' formative assessment practices in SES-different classrooms: a Taiwan study. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 10, 553–579. doi: 10.1007/s10763-011-9299-7

Cipriano, C., Barnes, T. N., Bertoli, M. C., and Rivers, S. E. (2018). Applying the classroom assessment scoring system in classrooms serving students with emotional and behavioural disorders. Emot. Behav. Difficult. 23, 343–360. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2018.1461454

Clark, I. (2014). Equitable learning outcomes: supporting economically and culturally disadvantaged students in ‘formative learning environments'. Improv. Sch. 17, 116–126. doi: 10.1177/1365480213519182

Coles-Richie, M., and Charles, W. (2011). Indigenizing assessment using community funds of knowledge: a critical action research study. J. Am. Indian Educ. 50, 26–41. doi: 10.1353/jaie.2011.a798457

Copp, D. T. (2017). Policy incentives in Canadian large-scale assessment: how policy levers influence teacher decisions about instructional change. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 25:115. doi: 10.14507/epaa.25.3299

Cumming, J., Kimber, K., and Wyatt-Smith, C. (2012). Enacting policy, curriculum and teacher conceptualisations of multimodal literacy and English in assessment and accountability. English Aust. 47, 9–18.

Curry, K. A., Mwavita, M., Holter, A., and Harris, E. (2016). Getting assessment right at the classroom level: using formative assessment for decision making. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 28, 89–104. doi: 10.1007/s11092-015-9226-5

Dupont, P. (2018). Assessing adolescent reading comprehension in a French middle school: performance and beliefs about knowledge. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 30–61. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v43n7.3

Glover, T., Reddy, L., Kettler, R., Kunz, A., and Lekwa, A. (2016). Improving high-stakes decisions via formative assessment, professional development, and comprehensive educator evaluation: the school system improvement project. Teach. Coll. Rec. 118, 1–26.

Graham, L. J., Tancredi, H., Willis, J., and McGraw, K. (2018). Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment. Aust. Educ. Res. 45, 103–124. doi: 10.1007/s13384-018-0266-y

Hannigan, C., Alonzo, D., and Oo, C. Z. (2022). Student assessment literacy: indicators and domains from the literature. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Prac. 1–23. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2022.2121911

Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., and Harnett, J. A. (2015). Analysis of New Zealand primary and secondary student peer- and self-assessment comments: applying Hattie and Timperley's feedback model. Assess. Educ. Principles Policies Prac. 22, 265–281. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2014.976541

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Herzog-Punzenberger, B., Altrichter, H., Brown, M., Burns, D., Nortvedt, G. A., Skedsmo, G., et al. (2020). Teachers responding to cultural diversity: case studies on assessment practices, challenges, and experiences in secondary schools in Austria, Ireland, Norway, and Turkey. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 32, 395–424. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09330-y

Holme, J. J., Richards, M. P., Jimerson, J. B., and Cohen, R. W. (2010). Assessing the effects of high school exit examinations. Rev. Educ. Res. 80, 476–526. doi: 10.3102/0034654310383147

Jimenez, L., and Modaffari, J. (2021). Future of Testing in Education: Effective and Equitable Assessment Systems Center for American Progress. Available online at: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/future-testing-education-effective-equitable-assessment-systems/ (Accessed July 12, 2022).

Kang, H., and Furtak, E. M. (2021). Learning theory, classroom assessment, and equity. Educ. Measure. Iss. Prac. 40, 73–82. doi: 10.1111/emip.12423

Kerr, B. G., and Averill, R. M. (2021). Contextualising assessment within Aotearoa New Zealand: drawing from mātauranga Māori. AlterNative Int. J. Indigenous Peoples 17, 236–245. doi: 10.1177/11771801211016450

Klenowski, V. (2014). Towards fairer assessment. Aust. Educ. Res. 41, 445–470. doi: 10.1007/s13384-013-0132-x

Lamb, S., Glover, S., and Walstab, A. (2014). Educational Disadvantage and Regional and Rural Schools. Melbourne, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). Available online at: https://www.acer.org/files/Glover.pdf (Accessed August 1, 2023).

Loughland, T., and Alonzo, D. (2019). Teacher adaptive practices: A key factor in teachers' implementation of assessment for learning. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 44. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2019v44n7.2

Mark, S. L., Tretter, T., Eckels, L., and Strite, A. (2020). An equity lens on science education reform-driven classroom-embedded assessments. Action Teach. Educ. 42, 405–421. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2020.1756527

Marynowski, R., Mombourquette, C., and Slomp, D. (2019). Using highly effective student assessment practices as the impetus for school change: a bioecological case study. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 18, 117–137. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2017.1384497

Modell, N., and Gerdin, G. (2021). ‘But in PEH it still feels extra unfair': Students' experiences of equitable assessment and grading practices in physical education and health (PEH). Sport Educ. Soc. 27, 1047–1060. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2021.1965565

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and PRISMA Group* (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Murillo, F. J., and Hidalgo, N. (2017). Students' conceptions about a fair assessment of their learning. Stud. Educ. Eval. 53, 10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.01.001

Nayir, F., Brown, M., Burns, D., O'Hara, J., McNamara, G., Nortvedt, G., et al. (2019). Assessment with and for migration background students-cases from Europe. Euras. J. Educ. Res. 79:39. doi: 10.14689/ejer.2019.79.3

Newkirk-Turner, B. L., and Johnson, V. E. (2018). Curriculum-based language assessment with culturally and linguistically diverse students in the context of mathematics. Lang. Speech Hearing Serv. Sch. 49, 189–196. doi: 10.1044/2017_LSHSS-17-0050

Nortvedt, G. A., Wiese, E., Brown, M., Burns, D., McNamara, G., O'Hara, J., et al. (2020). Aiding culturally responsive assessment in schools in a globalising world. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 32, 5–27. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09316-w

Nurhayati, S., and Herman, T. (2020). Student perspective on fairness of assessment in mathematics classroom. J. Phys. Confer. Ser. 1469:12155. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1469/1/012155

Oo, C. Z., Alonzo, D., and Asih, R. (2022). Acquisition of teacher assessment literacy by pre-service teachers: A review of practices and program designs. Issues in Educational Research 32, 352–373. Available online at: http://www.iier.org.au/iier32/oo.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/f8d7880d-en

Parekh, G., Brown, R. S., and Zheng, S. (2021). Learning skills, system equity, and implicit bias within Ontario, Canada. Educ. Policy 35, 395–421. doi: 10.1177/0895904818813303

Perry, L. B., and Lubienski, C. (2024). Equity in Australian education: Still a work in progress. Aust. Educ. Res. doi: 10.1007/s13384-024-00630-4 [Epub ahead of print].

Productivity Commission (2022). Review of the National School Reform Agreement, Interim Report. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

Prøitz, T. S. (2010). Learning outcomes: What are they? Who defines them? When and where are they defined? Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 22, 119–137. doi: 10.1007/s11092-010-9097-8

Rahman, K. A., Hasan, M. K., Namaziandost, E., and Ibna Seraj, P. M. (2021). Implementing a formative assessment model at the secondary schools: attitudes and challenges. Lang. Test. Asia 11, 1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40468-021-00136-3

Rasooli, A., Razmjoee, M., Cumming, J., Dickson, E., and Webster, A. (2021). Conceptualising a fairness framework for assessment adjusted practices for students with disability: an empirical study. Assess. Educ. Principles Policies Prac. 28, 301–321. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2021.1932736

Rasooli, A., Zandi, H., and DeLuca, C. (2018). Re-conceptualizing classroom assessment fairness: a systematic meta-ethnography of assessment literature and beyond. Stud. Educ. Eval. 56, 164–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.12.008

Rowan, L., and Townend, G. (2016). Early career teachers' beliefs about their preparedness to teach: Implications for the professional development of teachers working with gifted and twice-exceptional students. Cogent Educ. 3:1242458. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2016.1242458

Scott, S., Webber, C. F., Lupart, J. L., Aitken, N., and Scott, D. E. (2014). Fair and equitable assessment practices for all students. Assess. Educ. Principles Policies Prac. 21, 52–70. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2013.776943

Shepard, L. A. (2019). Classroom assessment to support teaching and learning. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 683, 183–200. doi: 10.1177/0002716219843818

Sirin, S. R., and Rogers-Sirin, L. (2020). Culturally responsive measurement in education: addressing test bias and fairness. Educ. Measure. Iss. Prac. 39, 24–35. doi: 10.1111/emip.12359

Smith, C., Parr, N., and Muhidin, S. (2018). Mapping schools' NAPLAN results: a spatial inequality of school outcomes in Australia. Geograph. Res. 57, 133–150. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12317

Snow, K., Miller, T., and O'Gorman, M. (2021). Strategies for culturally responsive assessment adopted by educators in Inuit Nunangat. Diaspora Indigenous Minority Educ. 15, 61–76. doi: 10.1080/15595692.2020.1786366

Stevens, P. A. J., and Van Houtte, M. (2011). Adapting to the system or the student? Exploring teacher adaptations to disadvantaged students in an English and a Belgian secondary school. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 33, 59–75. doi: 10.3102/0162373710377112

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed. Sage Publications.

Thomas, J., and Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tierney, R. D. (2014). Fairness as a multifaceted quality in classroom assessment. Stud. Educ. Eval. 43, 55–69. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.12.003

Tierney, R. D., Simon, M., and Charland, J. (2011). Being fair: teachers' interpretations of principles for standards-based grading. Educ. Forum 75, 210–227. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2011.577669

Tomlinson, C. A., and Jarvis, J. M. (2014). Case studies of success. J. Educ. Gifted 37, 191–219. doi: 10.1177/0162353214540826

Townend, G., and Brown, R. (2016). Exploring a sociocultural approach to understanding academic self-concept in twice-exceptional students. Int. J. Educ. Res. 80, 217–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2016.07.006

Triventi, M., Vlach, E., and Pini, E. (2021). Understanding why immigrant children underperform: evidence from Italian compulsory education. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 2305–2323. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1935656

UNESCO. (2020). Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education - All Means All. UNESCO Publishing. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718 (Accessed April 8, 2023).

Uretsky, M. C., and Stone, S. (2016). Factors associated with high school exit exam outcomes among homeless high school students. Child. Sch. 38, 91–98. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdw007

Whatman, S., and Singh, P. (2015). Constructing health and physical education curriculum for indigenous girls in a remote Australian community. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 20, 215–230. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2013.868874