- 1Teaching and Learning Innovation Center, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

- 2Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Learning Sciences and Assessment, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Introduction: Making student voice heard is crucial for productive feedback. However, this is seldom in practice in the exam-oriented context because students lack opportunities and support to give voice in feedback processes. To bridge the gap, this collaborative action research explored how feedback could be redesigned to invite student voice in a Singapore secondary school.

Methodology: We collaborated with three Social Studies teachers to transform their error-focused practice into dialogic feedback accentuating student voice. Drawing on the Lundy model of participation and self-determination theory, the teachers designed a feedback log to let 48 secondary four (equivalent to Grade 10) learners articulate their voice and psychological needs for competence and relatedness.

Results: Analysis of feedback logs, student focus groups and teacher interviews indicated three main aspects of student voice: (i) grades (numeric feedback) as an indicator to monitor one's goal achievement and exam preparation efforts; (ii) challenges in making feedforward; and (iii) learners' feedback engagement and motivation largely shaped by teacher response.

Discussion: Given the context-dependent nature of tasks in Social Studies, verbal reciprocal exchange would be useful in developing students' higher-order thinking skills for feedforward. Implications for productive feedback designs are discussed, and avenues for future research outlined.

1 Introduction

Feedback is a dialogic process in which students and teachers participate actively in reciprocal exchange to clarify assessment standards, discuss performance gaps, and develop improvement plans for academic regulation (Carless, 2012; Steen-Utheim and Wittek, 2017). An understanding of student voice in dialogic feedback is essential because “without the learner's perspective the crucially important affective and interactional aspects of learners' responses to feedback are likely to be missing” (Hargreaves, 2013, p. 230). By heeding student voice, teachers could diagnose and address learners' needs, increase their learning interest and responsibility, and establish a caring and supportive classroom atmosphere (Plank et al., 2014).

Notwithstanding the importance of student voice, the field lacks a widely accepted definition to guide empirical investigations. Rudduck and McIntyre (2007) see student voice as students' perspective on the things that influence their learning or matter to them in the instructional process. Cook-Sather (2006) defines it as students' say in education-related decision-making where they have “the opportunity to speak one's mind, be heard and counted by others, and, perhaps, to have an influence on outcomes” (p. 362). Though both interpretations indicate varying degrees of engagement, they are not mutually exclusive in examining students' dialogic feedback experiences because productive feedback is predicated on a substantial student role (van der Kleij et al., 2019) whereby students exercise agency to decide the focus of dialogue, convey their perspective, and partner with teachers to construct improvement suggestions (Carless, 2020; Matthews et al., 2023). To take note of this point, we conceptualize student voice in feedback as learners' active involvement in expressing their feedback needs, understanding of feedback, and thoughts about performance improvement.

Feedback practices in exam-oriented societies tend to be teacher-centered and focus on error corrections (Lee and Coniam, 2013; Tay and Lam, 2022). Such orientation restricts student role and voice in feedback processes. Despite Plank et al.'s (2014) call for examining student role in feedback, van der Kleij et al.'s (2019) meta-review indicates that the increasing recognition of dialogic feedback is not accompanied by ample research evidence on how to elicit and strengthen student voice. To bridge the gap, we aim to explore how feedback could be redesigned to invite student voice in a Singapore secondary school. The research questions are shown below. The significance of this paper lies in unpacking student voice in feedback and giving recommendations for redesigning feedback in the exam-oriented context.

RQ1. What is student voice in feedback?

RQ2. How do teachers respond to the student voice?

RQ3. How do students and teachers perceive the effectiveness of the redesigned feedback practice?

2 Student voice in feedback

2.1 Student role in feedback processes

The feedback practices in the high-stakes assessment environment are usually characterized by extensive error corrections, concurrent release of grades and comments, and provision of improvement suggestions (Lee and Coniam, 2013; Tay and Lam, 2022). Though students could ask questions about teacher feedback and seek additional support, teachers are the key driver determining the goal and content of feedback interaction (van der Kleij et al., 2019).

The teacher-centered feedback practice may limit students' role. When the emphasis falls on knowledge acquisition and grades, they may perceive teachers as the authority in assessment and teachers' improvement advice as a short cut to boosting performance (Tan and Wong, 2018). Once they are accustomed to this approach, they may not recognize the need to self-evaluate performance, self-generate feedback and improvement plans. The comprehensive error corrections may also undermine their emotional wellbeing and discourage their engagement with feedback (Lee and Coniam, 2013). Furthermore, not all students could get usable and personalized feedback as teachers do not understand individual learners' needs (Ratnam-Lim and Tan, 2015). In the circumstances, they may find feedback unable to address their needs and thus lose the motivation to engage with it.

To strengthen students' role in dialogic feedback, Winstone et al. (2017) put forward the development of proactive recipience—seeking, interpreting and enacting feedback for academic regulation. At the core of proactive recipience is students' motivation to participate in feedback dialogue (van der Kleij et al., 2019). Three elements are vital for dialogic feedback: (i) unpacking success criteria to enable students' self-evaluation of performance and understanding of teacher feedback; (ii) opportunities for students to articulate expectations and interpretation of feedback; and (iii) teacher response to students' feedback needs (Adie et al., 2018). While the first element is evident in exemplar analysis, explanation of rubrics and checklists (e.g., Lee and Coniam, 2013; Tay and Lam, 2022), there has been a dearth of research looking into students' expression of voice and teachers' response to it.

2.2 Theoretical underpinnings

Our research is theoretically grounded in the Lundy model of participation (Lundy, 2007) and self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2020).

2.2.1 Lundy's model of participation

Lundy's participation model is developed to implement Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). This article stresses children's rights to express views freely in matters influencing them and their views to be given due weight in accordance with their age and maturity (Lundy, 2007). At school, the rights grant young learners who can formulate their own views the autonomy to participate in decision-making during the instructional process. Yet, their level of involvement could be influenced by tokenism (one's views not taken seriously by teachers) and power imbalance (Reynaert et al., 2009). Some in Confucian-heritage settings may eschew expression of voice due to the cultural values, for example deferring to teachers' judgments, favoring collectivism over individualism, and avoiding disclosing one's inadequacies for face-saving (Carless, 2011; Chong and McArthur, 2021). Hence, it is critical for teachers in such settings to highlight the benefits of voice articulation at the outset of feedback processes.

Lundy's (2007) model comprises four elements in upholding children's rights: (i) space (providing a safe and respectful environment and an opportunity for children to express views freely); (ii) voice (facilitating their expression of views); (iii) audience (individuals with decision-making power hear the children's views); and (iv) influence (acting upon their views when appropriate). In the context of feedback, space means students have psychological safety and the opportunity to state their feedback needs and understanding (Johnson et al., 2020). Voice refers to teachers' cognitive and affective scaffolding to aid students' articulation of views, for instance using prompts to guide students' identification of needs (Fletcher, 2018) and developing their confidence in communication (Steen-Utheim and Wittek, 2017). Audience points to the importance of teachers to listen to student voice and taking their voice seriously, and influence involves teachers responding to their voice accordingly (Matthews et al., 2023).

2.2.2 Self-determination theory

While the participation model offers a lens to examine student voice, it does not address learner motivation in feedback processes. SDT fills the gap by emphasizing that students are motivated to learn if their psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness are satisfied (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2020). In relation to feedback, autonomy refers to students' volition to seek feedback and their decision to engage with it for academic regulation. Competence pertains to their feeling of capability in reaching their desired goals. Relatedness concerns their affective connection with teachers and peers, and the care and respect experienced in interaction. To enhance their motivation and psychological wellbeing, teachers could provide autonomy support to meet their psychological needs. This involves (i) giving students choices and opportunities to initiate feedback, (ii) explaining the rationale for feedback practice, (iii) acknowledging their emotions, achievements and improvements with positive feedback, (iv) offering task-related assistance to increase their self-efficacy, and (v) demonstrating empathy, respect and trust in feedback communication (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Zhang et al., 2024).

From the SDT perspective, students may lack intentionality to engage with feedback (amotivation) if they find it not useful to learning, or the given feedback does not satisfy or dents their self-ego. They are intrinsically motivated when they find enjoyment and satisfaction from feedback processes. Between amotivation and intrinsic motivation, they could be extrinsically motivated by external incentives such as grades (numeric feedback), praises or criticisms. Depending on the motive and their way of reaction, they could have different subtypes of extrinsic motivation (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2020): (i) external regulation (motive driven by rewards or punishment); (ii) introjection regulation (motive driven by one's intent to satisfy or protect self-ego); (iii) identified regulation (motive driven by one's perceived importance or value of the behavior); and (iv) integrated motivation (motive driven by the behavior consistent with one's abiding values and interests). For example, grades (external motive) usually impose external regulation and demotivate underachievers because numeric feedback hurts their self-esteem and provides no specific information for performance advancement (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich and Smith, 2009). Nevertheless, students with high achievement orientation could internalize extrinsic motivation and become identified regulated when they use grades to monitor learning progress and modify their study behaviors accordingly for goal fulfillment (Alhadabi and Karpinski, 2019; To et al., 2023a). There are also cases of introjection regulation where students use teacher feedback to confirm their self-evaluation of performance (Mulliner and Tucker, 2015; Pricinote et al., 2021).

2.3 Pertinent studies and research gaps

To our knowledge, not many studies have explored the connection between feedback design and student voice. From our careful review of literature, we manage to identify three pertinent studies in the school context. The first study is the use of a project planning guide to facilitate primary students' initiation of feedback dialogue (Fletcher, 2018). To prepare them for an English writing project, their teachers discussed the planning guide to help them understand success criteria, set task goals and choose appropriate task strategies. After they had written an initial draft, they self-assessed performance using a checklist, identified their strengths and weaknesses, explained their achievements and problems, and sought feedback. With an understanding of their self-assessment and feedback needs, their teachers gave response in group meetings where students with similar problems could clarify issues and brainstorm strategies with their peers and teachers for subsequent draft enhancement. Through interviews and analysis of their project planning guides and writing samples, Fletcher (2018) ascertained that teacher scaffolding and the self-assessment enabled students' articulation of voice. The interaction in the feedback meetings allowed teachers to customize support and to foster relatedness with students.

The second one is van der Kleij's (2020) Feedback Engagement Enhancement Tool (FEET) to increase secondary school students' engagement with feedback. Throughout a 3-week trial in an English writing class, the students documented four types of information on a FEET booklet in preparation for a summative assignment: (i) all written and oral feedback from teachers, peers and students themselves and the emotions triggered by the feedback; (ii) their interpretation of feedback and statement of feedback needs; (iii) self-developed improvement plans; and (iv) reflections on their improvement actions. Teacher interviews, student focus groups and their FEET booklets showed that acknowledging students' emotions of feedback could encourage their engagement. The FEET tool enhanced students' agentic role and provided a basis for teacher-student feedback exchange, However, only high proficiency students were able to internalize the feedback given, seek additional feedback, and generate an improvement plan. van der Kleij (2020) concluded that more reflective skills training would be useful to aid students in turning external feedback to self-initiated improvement plans.

The third one is the employment of a self-assessment form to enable secondary school students' articulation of targeted performance level and improvement plan (To et al., 2023b). Embedding the feedback practice in the draft-plus-rework design for an oral presentation task, a team of Malay Language teachers explained the rubric, engaged students in audio exemplars of presentation, and arranged reciprocal peer assessment after students' production of initial presentation. Upon reflecting on the peer feedback, they stated their performance goal, aspects to be improved in the enhanced presentation, and improvement plan on the self-assessment form. Following their production of enhanced presentation, the teachers commented on goal achievement, presentation quality, and improvement plan. While the study mainly explored teacher feedback literacy development, the teachers' reflective journals and focus groups revealed that the feedback design gave students autonomy in the assessment process. The rubric explanation, exemplars discussion and teachers' comments on their self-assessment served as useful autonomy support to address their psychological need for competence.

The synthesis of the three studies indicates four feedback design principles for eliciting student voice. First, all the designs grant students some decision-making power, ranging from determining the focus of dialogue (Fletcher, 2018) and devising improvement plans (van der Kleij, 2020; To et al., 2023b). This enhances their feedback responsibility and fulfills their psychological need for autonomy. Second, all have a written artifact to facilitate students' expression of voice, for example the project planning guide (Fletcher, 2018), FEET (van der Kleij, 2020), and self-assessment form (To et al., 2023b). This is important as externalizing one's affect, cognition and metacognition catalyzes academic self-regulation (Nicol and McCallum, 2022) and aids teachers' understanding of learners' needs. Third, all emphasize teacher scaffolding to support students' generation of self-feedback. Such scaffolding encompasses rubric explanation to unpack success criteria (Fletcher, 2018), exemplar analysis to sharpen academic judgment (To et al., 2023b) and training to derive reflective insights from external feedback (van der Kleij, 2020). Fourth, teachers have an opportunity to respond to student voice through feedback meetings (Fletcher, 2018) or written comments (To et al., 2023b). This demonstrates that student voice is taken seriously.

Although the reviewed studies have illustrated the principles for feedback designs, there are still unanswered questions. Since the three studies are contextualized in language subjects, the feedback designs may not fit non-language subjects because of variations in discipline-specific feedback practices (Carless et al., 2023; Quinlan and Pitt, 2021). Moreover, few studies have systematically analyzed student voice and teacher response to it. This warrants scrutiny because teacher response carries potential in influencing students' confidence and volition to seek additional feedback (Plank et al., 2014). Furthermore, scant literature has compared students' and teachers' perceptions of feedback designs. If both parties have shared responsibility in productive feedback, it is essential to examine the differing perceptions so that feedback could be redesigned for mutual benefit.

3 Method

3.1 Research approach

We employed the collaborative action research approach as teachers could be empowered as the change agent to reshape their existing power structure and feedback practice under researchers' support (Burns, 1999). Through school-university collaboration, we could achieve praxis by considering the practicalities of feedback design principles (Banegas et al., 2013). In this study, our teacher participants redesigned, implemented and reflected on the feedback practice. We enlightened them on feedback design principles and examples and facilitated their meaningful reflective dialogue at different time points in the research process.

3.2 Sociocultural context

Our study was situated in Singapore, an exam-oriented society where students' nationwide examination results at the end of primary and secondary education influence their school placement and future career prospects. Unsurprisingly, the high-stakes examinations not only exert intense stress on students and their parents but also influence school-based assessment at all levels by focusing students and teachers on national examination preparation (Tan, 2011). For example, primary school students are taught how to “scaffold” their language compositions with memorized phrases and suggested formats in adherence to scoring rubrics. It is customary for teachers to use drilling or practice tasks to hone students' exam-taking skills and to correct all students' errors to reduce reoccurrence in examinations (Wong et al., 2020).

To mitigate negative washback, the Ministry of Education (MOE) has made strenuous efforts to balance high-stakes summative assessment with more formative use of assessment in schools. In 2008, the MOE introduced “Holistic Assessment” and encouraged primary schools to provide more qualitative feedback for improvement and to design “bite-sized” assessment as an alternative to one-off examinations, with the purpose of reducing assessment stress and test anxiety (Ministry of Education, 2019). However, teachers reported challenges in couching feedback that could be understood and acted upon by students. Designing bite-sized assessment tasks seemed to create more frequent occurrences of assessment and consequently more stress for students and teachers (Ratnam-Lim and Tan, 2015). The study by Deneen et al. (2019) further showed that secondary school teachers seemed to value formative assessment but perceived a lack of assessment literacy and opportunities to practice it. A more recent initiative involved scrapping mid-year examinations at all school levels from 2023 onward (Ministry of Education, 2022). Nevertheless, despite all these initiatives, examination preparation remained important in teaching and learning. Developing a feedback pedagogy suitable for this high-stakes assessment environment becomes the main mission of educators in Singapore.

3.3 School context

This study was conducted as part of our funded research on “a pedagogy of feedback” in the 2023 academic year.1 We adopted criterion sampling (Suri, 2011) for school selection. The three criteria included (i) one of the school development areas relevant to students' feedback engagement; (ii) Principal's support to school-university collaboration; and (iii) teachers' strong commitment to professional development. In the pursuit of excellence and innovation in teaching, the Principal encouraged each subject team to undertake a professional inquiry of their own interest for pedagogical or assessment advancement every year. Upon explaining our research to all Department Heads, the Social Studies team saw an overlap between our project and their professional inquiry and so expressed interest in collaboration.

After communication and coordination work in Term 1, we had regular meetings with the subject team in Term 2 to understand their problems in the original feedback practice and to discuss feedback redesign. To furnish the team with professional support, we explained the importance of attending to student voice, shared the feedback designs of Fletcher (2018), van der Kleij (2020) and To et al. (2023b) and the design principles in Section 2.3, facilitated their reflections on the original practice, and gave advice on the redesign. The meetings were facilitated by the first and third authors who possessed rich experience in feedback research and teacher professional development in the exam-oriented context. The feedback redesign was implemented and evaluated in Term 3. No professional and research activities were performed in Term 4 as the team and students were busy preparing for the school's year-end and nationwide exams.

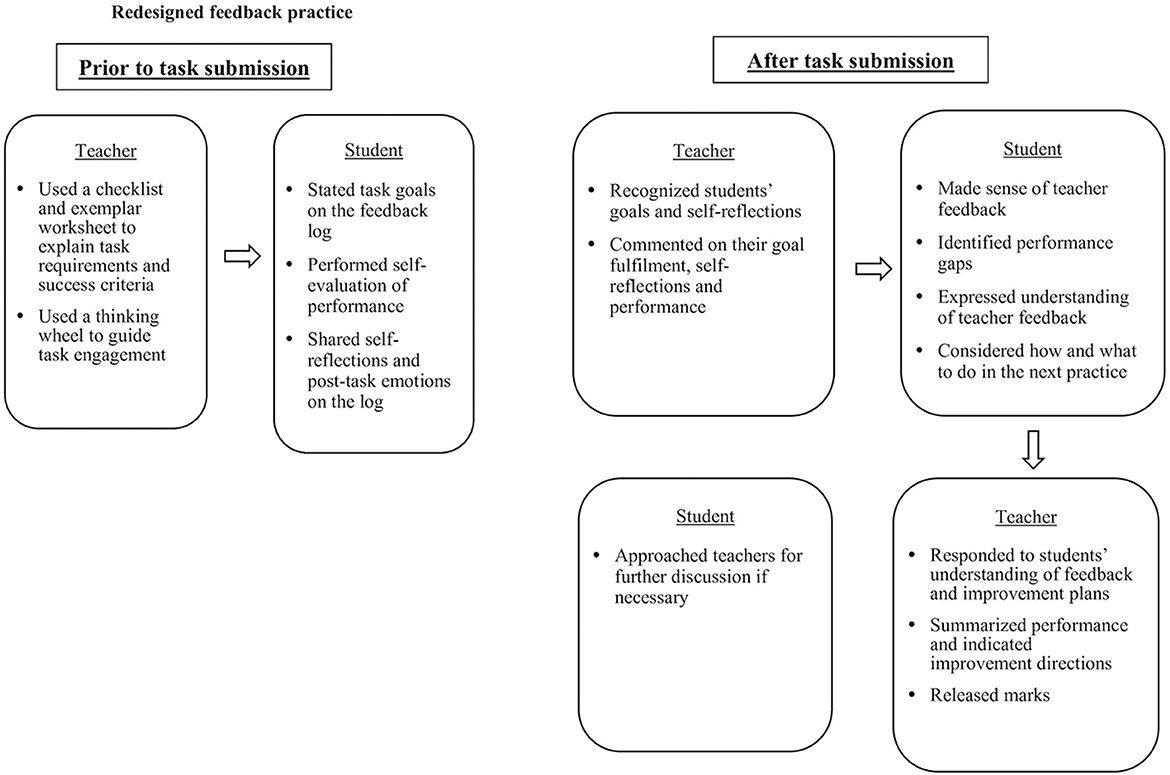

3.4 Participants

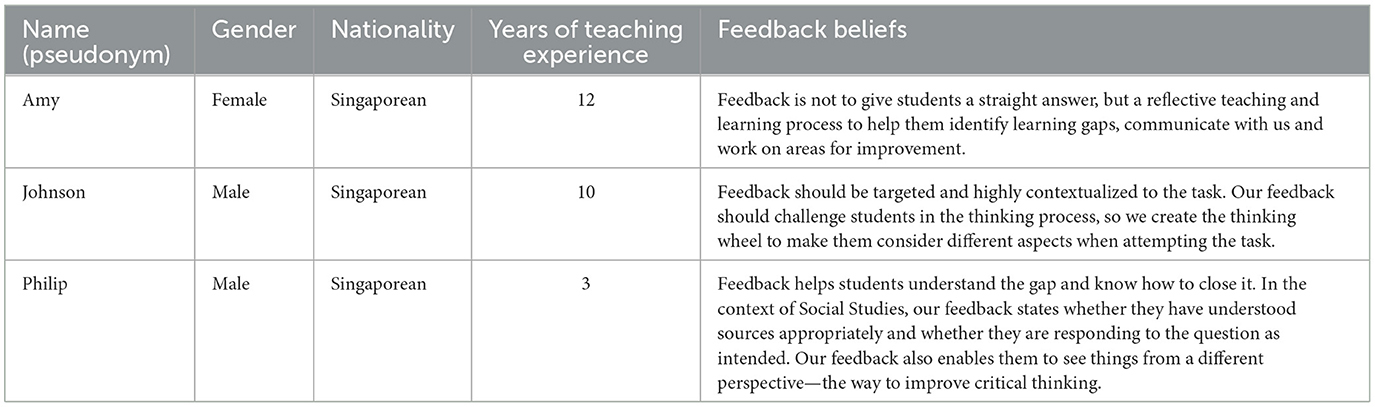

The Social Studies team consisted of three teachers. They had a high level of assessment literacy to improve students' feedback uptake. Table 1 shows each teacher's profile and feedback beliefs. The team decided to reform the feedback practice in Secondary 4 (equivalent to Grade 10) classes as they wished to increase students' feedback uptake before the General Certificate Education Ordinary Level (GCE O-Level) exam at the end of Secondary 5. The feedback redesign was implemented to all six classes (192 students in total, 32 per class on average) in Term 3. They and their parents chose to participate in the study after we had explained the project objective and data collection procedure. Finally, forty-eight students agreed to participate in the study. The non-participants still received teacher feedback under the redesigned practice, but no data were collected from them.

To prepare for the GCE-O Level exam, the students worked diligently and regarded every practice task as an opportunity to advance their subject knowledge and exam-taking skills. They expected to know marks, strengths and weaknesses in performance and improvement suggestions so that they could review their efforts for exam preparation. During Secondary 1–3, they had been trained to self-evaluate performance using a checklist, but they were not required to discuss their self-assessment and understanding of feedback with teachers. So, articulating voice in feedback processes was a novel experience to them.

3.5 Original feedback practice

Prior to this project, the team utilized the teacher-centered, error-focused feedback approach to source-based case study questions (one of the task types in the GCE O-Level exam). For task preparation, the team first used exemplars to illustrate task structure and success criteria and then gave students a checklist for self-assessment. During grading, the team put down marks and written comments on students' task sheets. Since the case study questions assessed analytical, critical thinking and perspective taking skills, the team identified students' problems with skills acquisition and used questions to stimulate in-depth thinking. This was followed by an in-class explanation of students' major problems and recommendations for skills enhancement. The students were not required to revise their work because the team believed that more practice on different topics would be more useful for learning. In case individuals had questions about the task or feedback, they could consult their teachers outside class.

Upon reflection, the team opined that the feedback practice was ineffective due to students' recurring problems in subsequent tasks. The team ascribed their limited feedback uptake to two reasons. First, most students did not understand the skills-focused feedback and thus were unable to generate improvement plans. Second, only high-achieving students sought clarification and discussed improvement suggestions with teachers. The team speculated that this may be due to students' lack of motivation, opportunity or readiness to discuss learning issues with teachers. Without an understanding of individuals' needs, it was hard for the team to provide personalized feedback to scaffold learning. Hence, the team redesigned the practice in order to facilitate their expression of feedback needs and understanding of skills-focused comments and to encourage feedforward.

3.6 Redesigned feedback practice

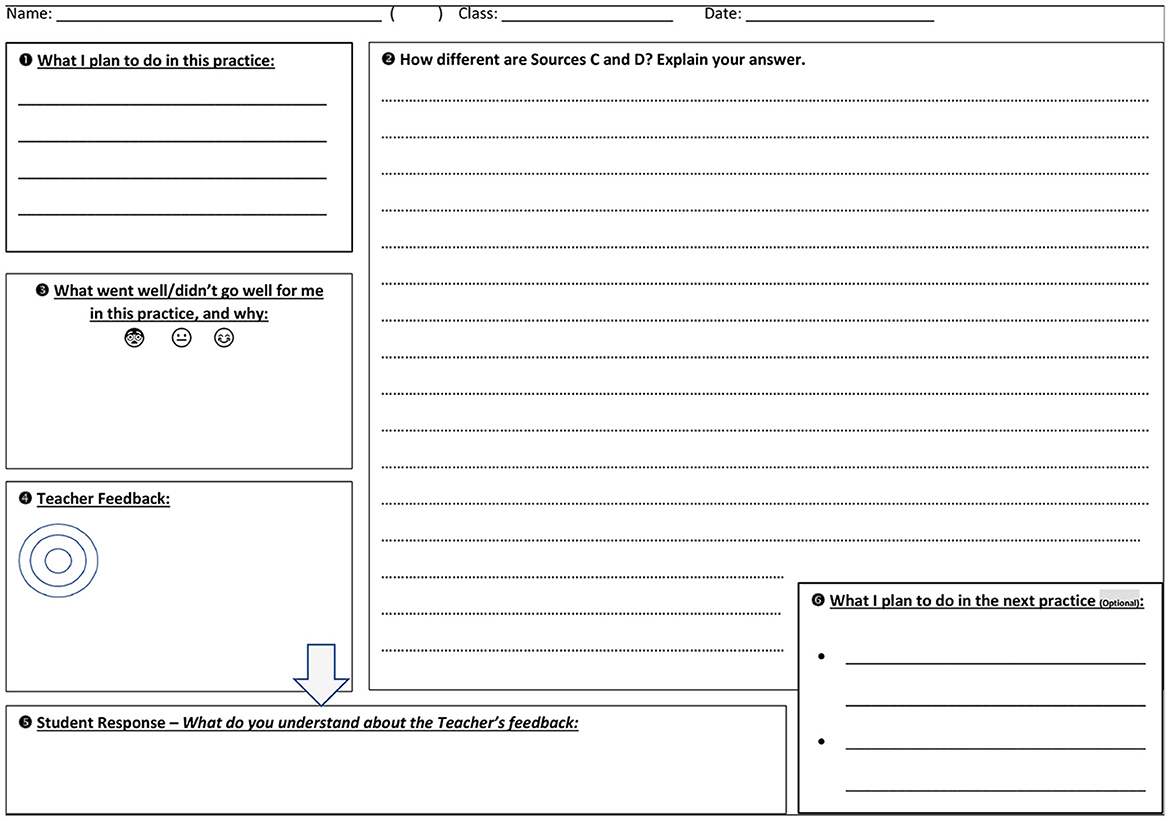

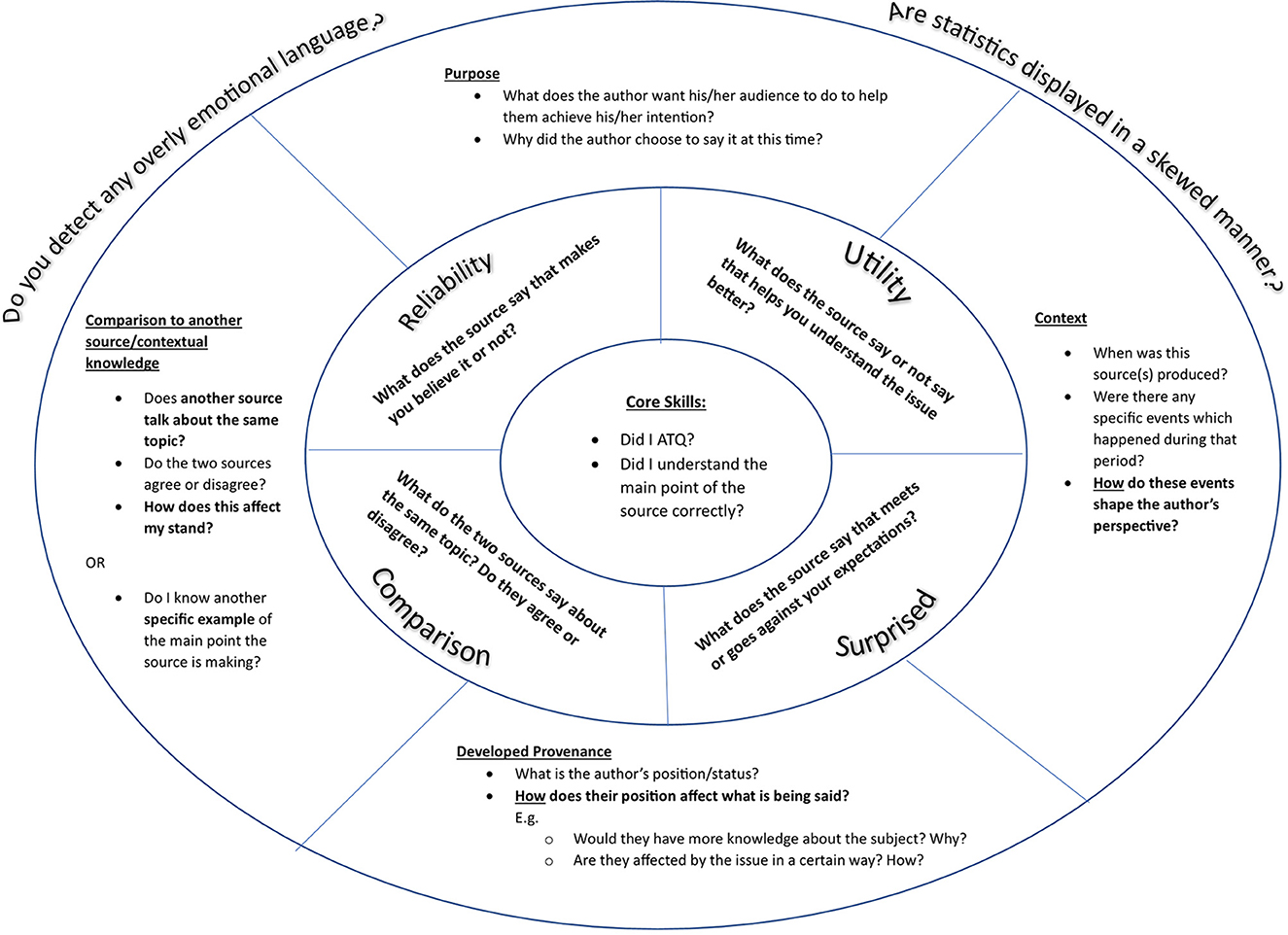

Taking the second design principle in Section 2.3, the team developed two written artifacts for the feedback redesign: (i) a feedback log (Figure 1) to enable students' articulation of voice; and (ii) a thinking wheel (Figure 2) to help them recognize the higher-order thinking skills expected of the task. In the redesigned practice, the students had the opportunity to express voice before and after task submission. Figure 3 depicts the involvement of teachers and students in feedback processes.

Prior to task submission, the teachers applied the third design principle and scaffolded students' goal setting and self-reflections with two strategies. First, the class discussion of a checklist and an exemplar worksheet helped students unpack success criteria, appreciate quality work, and use the criteria for self-evaluation. Second, the teachers explained how the thinking wheel could guide task engagement and how making one's goals and self-reflections explicit could improve feedback interaction. After individual students had stated task goals in Section 1 of the log and had completed the task in Section 2, they self-assessed performance in Section 3. The sharing of goals, post-task thoughts and emotions was crucial as this granted students the autonomy to initiate feedback dialogue and to express their psychological needs for competence and relatedness. This also aided their teachers in understanding individuals' and needs and personalizing feedback accordingly.

After task submission, the teachers read individual students' task response, commented on their performance and goal fulfillment, and responded to their reflections in Section 4 (the fourth design principle). The teachers put a tick on concentric circles (a miniature thinking wheel) to indicate whether the given comments related to core skills (inner ring), analysis of source content (middle ring) or routes to critical thinking (outer ring). In view of the impact of marks on emotions (Hattie and Timperley, 2007), the teachers withheld students' results to make students engage with the feedback. Following the receipt of the comments, the students underwent four cognitive and metacognitive processes: (i) making sense of teacher feedback on goal fulfillment, self-reflections and performance; (ii) identifying their own performance gaps; (iii) putting down their understanding of teacher feedback in Section 5; and (iv) outlining what to do in the next practice for feedforward in Section 6. This was another opportunity for them to articulate voice.

The drafting of the improvement plan was not mandatory because the teachers foresaw that not all students were able to describe their plan in writing. For those producing an improvement plan, the teachers would comment on its appropriacy. For those without a plan, teacher suggestions would be given. In the subsequent lesson, the teachers summarized students' key strengths and weaknesses, indicated improvement directions, and released their marks. They could approach their teachers to clarify comments or continue the discussion of improvement plans outside class.

3.7 Data collection

Our data collection methods included documentation of feedback logs, student focus group discussions (FGDs) and semi-structured teacher interviews.

We collected feedback logs at the end of Term 3 to analyze student voice in feedback processes. We adopted this method because documentation enabled us to gather data without intervening feedback interaction and to corroborate evidence from FGDs and teacher interviews (Bowen, 2009). As shown in Figure 1, the feedback log offered students space to articulate task goals and self-reflections, express understanding of teacher feedback, and state their plan for the next task. The log also documented individuals' task response and teacher comments on their self-assessment and performance. There was no word limit for student voice, so they could freely expound their views in English. To protect their anonymity, upon collecting the scanned copies of the logs, we removed individuals' identification information and assigned a pseudonym for each student.

We conducted FGDs to explore students' cognitive and emotional experiences of feedback and their perceived effectiveness of the feedback redesign. This cost-effective method allowed us to dig into diverse students' perspectives of the redesigned practice. The group dynamics among students could stimulate new thoughts and reduce researchers' influence during data collection (Lederman, 1990). In the final week of Term 3, 12 students in three FGDs (three in each FGD) shared their interpretation of teacher feedback and opinions about the feedback redesign. During the FGDs, the first and second authors showed individuals' feedback logs and invited them to explain their thoughts and feelings in feedback processes. We then facilitated a discussion of how the redesigned practice had shaped their feedback uptake and what factors came into play. All FGDs were carried out in English and recorded for analysis. Each took ~45 min. Appendix A lists the FGD questions.

We carried out two interviews to understand the team's development of the feedback redesign and facilitate reflections. The first interview was conducted at the outset of Term 2 to delve into individual teachers' feedback beliefs, the original feedback practice and problems encountered. This helped us understand the team's professional development needs and offer necessary support. The second one was performed after the implementation of the feedback redesign. We asked the team to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the feedback redesign, challenges in responding to student voice, and possible ways to improve the redesigned practice. To compare student and teacher perspectives, we then invited them to convey their views on the themes emerged from the FGDs, for example understanding of given feedback, provision of marks, and development of improvement plan. Both interviews were done in English and recorded for analysis. The first one lasted for 40 min, and the second one 70 min. Appendix B shows the interview questions.

3.8 Data analysis

To answer the research questions, we drew on Braun and Clarke's (2006) thematic analysis methods to analyze the feedback log, FGD and interview data. Since limited research has systematically studied student voice in feedback, our analysis was mainly inductive.

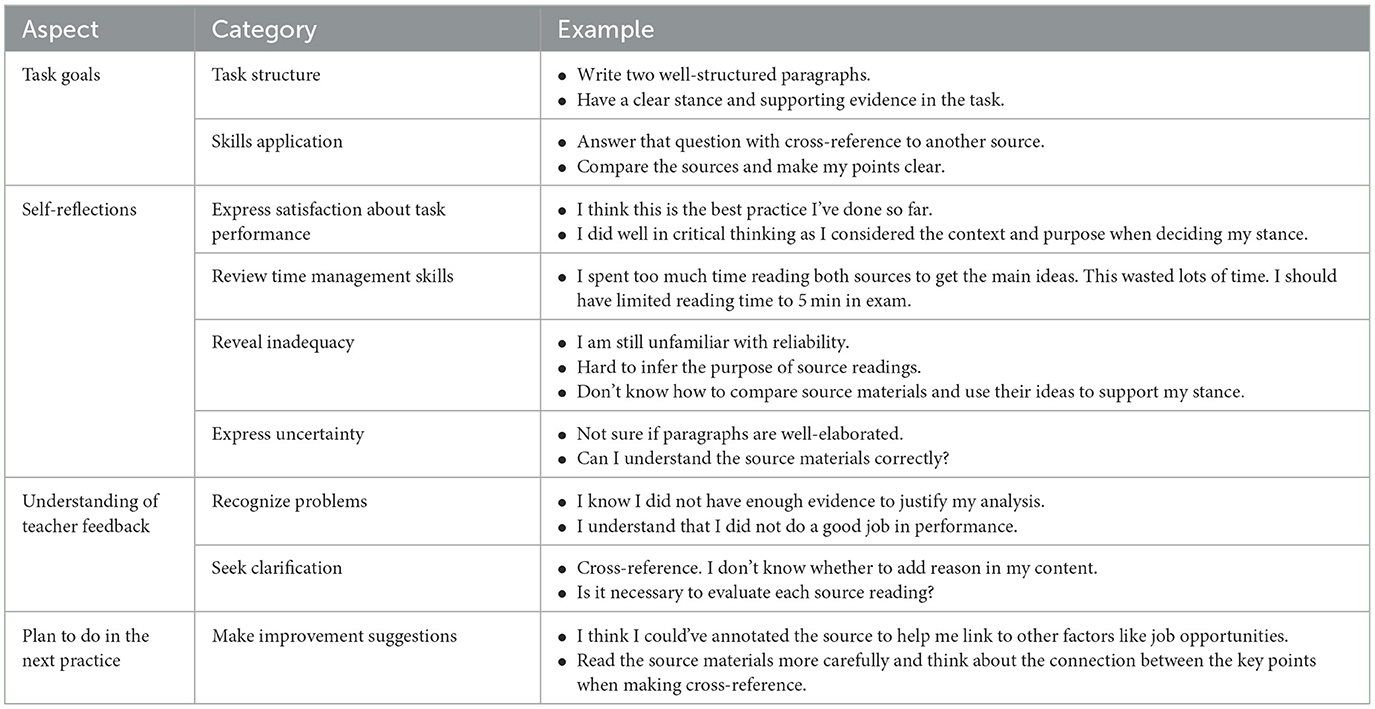

To analyze the feedback logs, the first author examined each student's goal, self-reflections, understanding of teacher feedback and plan for the next task. Then, she performed in vivo coding, and combined similar codes into themes. For instance, the self-reflection statement “I am still unfamiliar with reliability” was coded as “unfamiliar with reliability,” and another statement “It was difficult to understand the major argument of Source C” as “difficult to understand source materials.” Both codes were subsumed under the theme “reveal inadequacy.” Following iterative reviews of the themes by the other authors, we confirmed nine themes under four aspects of student voice. For data display, we compiled Table 2 in Section 4.1 to showcase all the themes and their illustrative examples. The main challenge in analysis involved categorizing teacher response to student voice because the response varied according to individual learners' goals, performance and other factors. To capture the complexity of reciprocal exchange, we identified three feedback vignettes to depict student-teacher interaction in a combination of circumstances.

To analyze the FGD and interview data, the second author read the transcripts, extracted quotes pertinent to student voice and the perceived effectiveness of the feedback redesign. Then, she reexamined the identified chunks, labeled them with in vivo codes, and grouped codes with similar meanings into themes. Afterward, the first author reviewed the set of candidate themes iteratively to check for data relevancy. In case of alternative interpretation, all authors reread the data, clarified our views, and reached consensus through discussion.

For data triangulation, we juxtaposed the data from the feedback logs, FGDs and interviews to look for data patterns emerged from the findings. We also compared students' and teachers' perceptions of the feedback redesign on a role-ordered matrix (Miles and Huberman, 1994) for a comprehensive examination of opinions. When spotting dissimilarities, we contemplated the possible factors for the differences. Any nuanced understanding about student voice in feedback was recorded on a theoretical memo (Urquhart, 2013) to aid our generation of significant insights.

3.9 Research ethics and trustworthiness

Prior to data collection, we obtained ethical clearance from National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University2 and Singapore Ministry of Education. We also gained consent for data use for research and publication from the Principal, Social Studies teachers, students and their parents. Students were informed that their decision to participate in the study would not influence their assessment results. They could choose to withdraw from the study anytime without any consequences. Pseudonyms were used when we reported individuals' experiences and views in the feedback vignettes and quotes.

To enhance the trustworthiness of the study, we observed credibility, transferability and managing subjectivity in analyzing and reporting the findings. We maintained credibility by triangulating the data from different sources to see whether the feedback design was implemented in the way described by the participants. We also explored the effectiveness of the redesigned practice from students' and teachers' perspectives. For transferability, we heeded Nunan and Bailey's (2009) advice to help readers see the connection between our findings and their situated context. This was achieved through a ‘thick description' (Merriam, 1998) of the sociocultural and school settings in Sections 3.2 and 3.3, a detailed explanation of the original and redesigned feedback practices in Sections 3.5 and 3.6, and our discussion of findings in relation to other studies. We managed subjectivity by confining our involvement to professional development support and facilitation of teachers' reflections. We also developed researchers' reflexivity by keeping a theoretical memo (Urquhart, 2013) to note down unexpected discovery and perspectives in contrast with our presumptions. Through interrogating the discrepancies, we strived to depict an objective picture of the phenomenon under investigation.

4 Findings

We organize the findings according to the research questions. We first report student voice in feedback, followed by teacher response to it and both parties' perceived effectiveness of the redesigned practice.

4.1 Student voice in feedback

Student voice is presented in four aspects: (i) Task goals; (ii) self-reflections; (iii) understanding of teacher feedback; and (iv) plan to do in the next practice. Table 2 exemplifies their voice in each aspect. Pertinent FGD findings are reported to cast light on students' experiences.

All the 48 student participants completed the section on task goals. Their goals mainly pertained to the structure and skills required of their practice task. When asked about why they focused on task structure and skills application in the FGDs, they mentioned that their performance in the GCE O-Level exam would be graded according to these categories, and they learnt about these requirements from the pre-task discussion. From the discussion of the checklist and exemplar worksheet, they realized that a well-written task response should contain a clear stance substantiated by evidence from source readings. The thinking wheel reminded them of the higher-order thinking skills expected of the task. Two points could be inferred from the data. First, positive washback was evident when the scaffolding increased their understanding of task and exam requirements. Second, their deep understanding enabled the setting of mastery goals (goals motivated by one's intent to self-improve or grow; Dweck, 1988). In line with Shen et al. (2024), their goal-setting behavior was highly associated with their exam preparation efforts in the high-stakes assessment environment.

Concerning self-reflections, all students expressed their post-task feelings and thoughts on the feedback logs. We observed a range of student voice. Some learners expressed pride in task performance and shared their achievements with teachers. We interpreted this as the evidence for students' psychological need for competence. Other learners reviewed time management skills, revealed inadequacies, and expressed uncertainty. The data seemed to imply that they felt psychologically safe to discuss their learning problems and to seek academic assistance.

Twenty-four students articulated understanding of teacher feedback. Their voice fell into two categories: (i) recognizing problems; and (ii) seeking clarification of teacher feedback. A closer look of their voice showed that they mainly agreed with teacher's judgment but did not generate internal feedback. This aligned with van der Kleij's (2020) observation about students' interpretation of feedback. There was one exceptional case where a student shared how she viewed her time management issue after reading the teacher comment. This case is further unpacked in Vignette B in Section 4.2. For those who chose not to respond to teacher feedback, we uncovered two reasons from the FGDs. First, they preferred a verbal discussion as it was hard to communicate their thoughts in writing. Second, a student (Harry) did not see the need for making response as he believed sharing his thoughts about the feedback would not raise his grades.

In consistent with van der Kleij's (2020) study, only a few students (12 in our study) outlined a concrete plan to do in the next practice. From the FGDs, we found three reasons why the majority of the students left this section blank. First, some failed to come up with suggestions to improve their work. Second, some valued teachers' suggestions more due to the expert role in subject knowledge. This was exemplified by Dave's quote “rather than trialing different methods on my own, following teachers' suggestions would be the straightforward way to improve performance.” Third, some doubted the transferability of improvement strategies from the current to the next task because task content and skill set varied according to topics. This point is further elaborated in Section 4.3.3.

4.2 Teacher response to student voice

To examine how teacher response would shape students' feedback engagement, we identify three feedback vignettes to depict the reciprocal interaction. These vignettes are selected because they feature different kinds of student involvement in feedback processes.

4.2.1 Vignette A

Lucy was a learner with high self-efficacy and a solid understanding of success criteria. She always performed well in Social Studies. Before undertaking the task, she set the goal “Write a well-elaborated paragraph with cross-reference.” After task engagement, she felt satisfied with her performance and wrote “I think this is the best practice I've done so far.” for self-reflections. When assessing her work, Philip (Lucy's teacher) thought she did a good job. He praised her with the comment “Well done! You did it! I'm really glad to see you achieve this on your own! Grow in confidence. You can do it.” He put a tick in the outer ring of the mini thinking wheel to indicate her strengths in comparing sources and developing provenance. Lucy did not write anything for understanding of feedback and plan for the next task. Philip did not put down any suggestions either as her work was of excellent quality. The interaction ended at this point.

Vignette A was a straightforward case of how a teacher responded to a student's psychological need for competence. Taking pride in task performance, Lucy shared her joy in the self-reflections with the intention of getting Philip's recognition. His positive feedback and encouragement confirmed her achievement. The dialogue was not further developed as Lucy's need was fulfilled and there was little room for further improvement. Neither Lucy nor Philip initiated another round of feedback conversation.

4.2.2 Vignette B

Lavender cared about her performance in the practice task because she believed the task helped her prepare for the GCE O-Level exam. As an average ability learner, she would like to advance her performance. She set her goal as “Write 2 comparison paragraphs and make reference to other sources,” which was one level higher than her current one. During self-reflections, she recognized her weakness in time management and wrote “I spent too much time reading both sources to get the main ideas. This wasted lots of time. I should have limited reading time to 5 min in exam.” To soothe her, Amy (Lavender's teacher) replied “No need to pressure yourself this way. Perhaps you could use the question to frame your thoughts and references.” Reflecting on the given suggestion, Lavender realized her issue and came up with a plan to reduce reading time. Amy thought Lavender's plan was viable and encouraged her to apply the strategy in the next practice.

Vignette B demonstrated how a teacher provided a student with relational and competence support. Lavender was not satisfied with her time management skills and worried that this problem would affect her exam performance. In response to her self-reflections, Amy consoled her and suggested a strategy to improve time management. With Amy's care and concrete suggestion, Lavender felt more confident to tackle her problem and could devise an improvement plan. In the FGD, Lavender said she felt respected and supported when her voice was heard by her teacher. This engendered her confidence in acting on teacher feedback. This scenario showed the importance of teacher's emotional support to students' uptake of feedback (cf. Steen-Utheim and Wittek, 2017).

4.2.3 Vignette C

Elizabeth lacked confidence in higher-order thinking skills and needed support in making inference. On the feedback log, she put down “Write a paragraph that shows inference” for task goal. For self-reflections, she explained how she had made inference in the practice task and expressed her uncertainty about quality of performance, hoping to get confirmation from her teacher. When grading her work, Johnson (Elizabeth's teacher) ticked the sentences in relation to inference but did not write any comments to address her concern. He instead threw the questions “What is the author context?” and “How does the context influence the author's stance?” to stimulate her thinking about making cross-reference. After receiving the feedback, she did not respond to it and did not make the plan for the next task. For suggestions, Johnson wrote comments to advise her to consider the outer ring of the thinking wheel and the relationship between the key points of the source material and the author's context. There was no further conversation between both parties.

Vignette C exemplified a case where a student believed her voice was not heard. Elizabeth would like to know how well she could make inference, so she described how she achieved the goal in the self-reflections and expected teacher feedback on her goal accomplishment. However, she felt her need for competence unfulfilled as Johnson did not directly comment on her inferencing skills and raised questions to stimulate her thinking about cross-referencing instead. In the FGD, she expressed disappointment about the teacher response, so she did not write anything in return. In fact, Johnson addressed Elizabeth's need through ticks, but this was not the way she had expected. If he had confirmed her mastery of inferencing skills first, this would have instilled her confidence and encouraged her further participation.

4.3 Perceived effectiveness of the redesigned feedback practice

To explore the perceived effectiveness of the redesigned practice, we compare students' and teachers' perspectives on three main aspects of feedback communication (setting ground for reciprocal exchange; ways to communicate feedback; making feedforward).

4.3.1 Setting ground for reciprocal exchange

Both students and teachers believed that stating task goals and self-reflections effectively primed them for the feedback dialogue. The following quotes convey students' views.

At first, I was clueless why I had to do reflections. The teacher said we would not receive any feedback unless we told her how we thought of our work. Later, I figured out that we played a role if we wished to get useful feedback. (Dave, student FGD 3)

This arrangement helped teacher understand me better. When I answered the question wrongly, he could understand what I wanted to do and what hindered me from doing so. He could base the feedback on it. I feel like I have some say of the feedback content, so I expect his reply to my self-reflections. (Pete, student FGD 1)

Making one's goals and self-reflections explicit strengthened students' role in feedback and encouraged their participation. Through unpacking cognitive process to teachers, they realized that disclosure of self-assessment enabled teachers to understand their learning needs and customize feedback accordingly. This gave them a sense of autonomy and motivated them to engage with teacher feedback in the subsequent stage.

Echoing the students' opinions, the teachers expressed the following.

Different from our previous practice, we could now understand their thoughts and emotions. This is a good opportunity to develop communication and rapport with individual students. (Philip, teacher interview 2)

This practice helped us narrow feedback focus and provide personalized support. For students weak in paragraph structure, we highlighted the missing part and referred them to the exemplar. For those who already met the baseline, we used the thinking wheel to further develop their thinking. (Johnson, teacher interview 2)

Their self-reflections tell us their level of confidence when attempting the question. This is very important to me. If I know they are not so ready, I would walk them through the challenges. (Amy, teacher interview 2)

The teachers opined that an understanding of learners' goals and self-reflections facilitated feedback provision. The redesigned practice increased their knowledge of individual students' cognition and affect during task engagement. This offered them valuable input to personalize feedback, differentiate learning support, and foster relatedness with students.

4.3.2 How to communicate feedback

In juxtaposing both parties' perspectives, we discovered that students and teachers held differing expectations about the best way to communicate feedback. One of the differences lay in the importance of making acknowledgment.

I did not write anything for the response as the feedback was not related to my goal ‘Write a paragraph that shows inference'. Except for ticks and underlining, the teacher did not mention my inferencing skills. I want to know whether I performed well. (Elizabeth, student FGD 3)

If students could achieve their goal, I would put a tick. My comments prompt them to think about the parts requiring further efforts. Social Studies is a thinking subject. I would train them to see things from a different perspective. This skill could be applied in other tasks. (Johnson, teacher interview 2)

Both quotes point to the value of giving acknowledgment in feedback processes. Elizabeth, whose experience depicted in Vignette C, expected her teacher to begin the dialogue with written comments to acknowledge her competence. This may reflect the view of learners without a strong academic foundation because they need a confidence booster before delving into areas for improvement (Mulliner and Tucker, 2015; Pricinote et al., 2021). However, Johnson valued the development of thinking skills more as this was the discipline-specific feature of Social Studies. Though he ticked some sentences, Elizabeth interpreted this as not taking her voice seriously.

Another point of divergence involved the provision of marks. The quotes detail both parties' perspectives.

We do not state marks because some students would not read our feedback if they are okay with the marks. For a 7-mark question, some getting 5 may think they are good enough and do not bother about the missing points. However, the missing points are related to critical thinking. It would be more beneficial if they digest the feedback before getting the marks. (Amy, teacher interview 2)

I am not quite sure about my performance. I prefer teacher ticking the grids on a rubric and putting down marks and comments on my work. Marks tell me how far I am away from the target. Comments tell me the problems and how to do better. I get feedback in practice exercises in History and English. (Patrick, student FGD 3)

Similar to Irwin et al. (2013), Amy withheld marks because she thought the concurrent release of marks and comments would discourage students from upgrading performance if they were complacent with the results. However,_Patrick asserted the complementarity of both components in communicating performance gap. His view coincided with the students in the studies of Alhadabi and Karpinski (2019) and To et al. (2023a). Rather than seeing low marks in practice tasks as a demotivator, they regarded numeric feedback as an indicator of their learning progress.

4.3.3. Making feedforward

Since only a handful of students had outlined their plan for the next practice, we looked into their hurdles in this part of feedback processes. Two main themes emerged from the data: (i) lack of instant teacher support; and (ii) difficulties in setting a plan for future tasks. We delineate the first theme in the following.

I have a rough idea, but describing what I plan to do seems not very practical. I think talking about my plan and hearing what the teacher says would be more useful. (Judy, student FGD 2)

Verbal discussion may help. I would approach teachers to figure out the direction through asking questions and analyzing their answers. This works for me, but I know others seldom talk to teachers outside class. (Annabelle, student FGD 1)

Both students highlighted the importance of developing an improvement plan via verbal exchange with teachers. Particularly, the instantaneous response from teachers was crucial in promoting deep thinking (Alexander, 2020) and advancing their zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978). Nevertheless, as mentioned by Annabelle and the subject team in Section 3.5, most students were not proactive in discussing improvement plans with teachers outside class. This raised two concerns: (i) the appropriate form of dialogue to aid students in making feedforward; (ii) the need for reserving curriculum time to engage students in verbal discussion of improvement plans.

The second theme related to the cognitive demands in setting a task plan. A student and a teacher explicated the challenges as follows.

To set the plan, I need to know the task, think whether I attempted similar type of question before, recall my previous task experience and consider if the feedback helps. If I do not know what the next practice is, it is hard to do so. (Pinky, student FGD 3)

For Social Studies, even if two questions assess the same set of skills, the response should be contextualized to the topic and source. So, what is learnt from this task may not be fully applicable to the next. This is different from Math. When you see a certain kind of question, you can apply the formula to solve it. (Johnson, teacher interview 2)

The above quotes pointed to two difficulties in making feed-forward in Social Studies. First, since the content and skills requirements in case study questions varied according to topics, students needed to discern the contextual differences between questions, to recall their prior task experiences, and to think how they could apply previous feedback for task planning. The cognitive skills involved were akin to the three steps in the transfer process (recognize, recall, apply; Barnett and Ceci, 2002). However, the redesigned feedback practice did not equip students for the transfer. This issue was brought up for discussion in the teacher interview 2. To support students' transfer of feedback insights, the subject team planned to explicate such cognitive processes during in-class explanation of problems and suggestions, and to design a series of practice tasks allowing students' refinement of thinking skills. Second, the disciplinary nature of Social Studies posed another challenge for making feedforward. Due to the uniqueness of case study questions, it seemed essential for students to develop not only the skills but also a critical understanding of topics and source materials in transferring skills from one task to another. However, such training had not been offered to students.

5 Discussion

5.1 Student voice in feedback processes

This study explores student voice in feedback processes in the exam-oriented context with the aim of informing productive feedback designs. What distinguishes ours from other learner-centered feedback research (e.g., Fletcher, 2018; To et al., 2023a; van der Kleij, 2020) is the dissection of student voice and teacher response to it and the examination of student voice from the self-determination perspective. From the findings, we ascertain student voice in three main aspects: (i) grades (numeric feedback) as an indicator to monitor goal achievement and exam preparation efforts; (ii) challenges in making feedforward; and (iii) learners' feedback engagement and motivation largely shaped by teacher response.

Our findings lend a fresh perspective to the concurrent release of grades and comments. Previous assessment literature (e.g., Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich and Smith, 2009) warns us about the negative impact of grades on students' feedback engagement. This led the Social Studies teachers in our study to withhold marks in order to enhance students' engagement with feedback (cf. Irwin et al., 2013). However, our student participants did not quite appreciate this approach. Consistent with those in Alhadabi and Karpinski (2019) and To et al. (2023a), they believed that marks complemented comments in aiding exam preparation: the former indicated the discrepancy between their current and desired performance levels; the latter gave them specific suggestions to reach the desired goal. Unpacking this case from the self-determination lens, we speculate that this group of upper secondary school students may have internalized extrinsic motivation, have seen marks (external motive) as a regulation tool, and have enacted identified regulation. Inferred from the data, enabling students to set mastery goals and fostering their achievement orientation seem to support their internalization of extrinsic motivation.

Similar to van der Kleij's (2020) discovery, few students in our study devised a plan to make feedforward. While van der Kleij (2020) ascribes this issue to lack of reflective skills training, our analysis of student voice revealed other possible causes. On epistemic grounds, some students such as Judy may be reluctant to produce an improvement plan due to the perception that suggestions from the knowledge expert (teachers) would be more effective for exam preparation (Tan and Wong, 2018). On cognitive grounds, the feedback design in the study may overlook students' obstacles in making feedforward. Explained by Pinky in Section 4.3.3, translating teacher feedback into improvement acts required her recognition, recall and application of previous task, and feedback experiences to make far transfer (Barnett and Ceci, 2002). These higher-order thinking skills appear to be the discipline-specific feature of Social Studies, given the context-dependent nature of tasks in this subject.

The feedback vignettes in Section 4.2 provide corroborating evidence for Plank et al.'s (2014) proposition that teacher response to student voice could influence students' feedback engagement and motivation. Depicted in Vignette B, the teacher's consolation and suggestion fulfills Lavender's psychological needs for relatedness and competence, respectively. This allows her to appreciate the value of feedback dialogue and thus increases her volition to engage with feedback. In contrast, the unfulfillment of Elizabeth's competence need in Vignette C weakens her interest in feedback participation, leading to amotivation. Her case also demonstrates the significance of confidence building when interacting with less capable learners. Echoing the viewpoint of Mulliner and Tucker (2015) and Pricinote et al. (2021), low self-efficacious learners would feel psychologically safe to participate in feedback processes if they could gain confidence at the outset of dialogue.

5.2 Implications for feedback designs

Drawing on this study and pertinent literature, we derive insights into orchestrating productive feedback designs. Given the importance of understanding student voice (Plank et al., 2014), teachers could develop feedback tools, for example the feedback log or the project planning guide (Fletcher, 2018), to ascertain students' goals, task-related emotions, self-reflections and interpretation of comments. Doing so not only grants students' autonomy to articulate their psychological needs for competence and relatedness (Ryan and Deci, 2017, 2020) but also helps teachers recognize individual learners' needs and customize learning support. It is noteworthy that students accustomed to the teacher-centered approach may fail to identify their own feedback needs (Boud and Molloy, 2013). Hence, it is advisable for teachers to enhance students' knowledge of success criteria and self-reflection skills through discussion of rubrics, exemplars and checklists (Fletcher, 2018) or peer assessment (To et al., 2023b). Some students may not see the value of self-disclosure or may be hesitant to reveal feelings and thoughts. This could be tackled by an explanation of the benefits of self-disclosure and the establishment of a psychologically safe atmosphere to encourage students' articulation of voice (Steen-Utheim and Wittek, 2017; Johnson et al., 2020).

In addition to ascertaining student voice, teacher response to the voice plays a pivotal role in determining the effectiveness of feedback designs (Lundy, 2007; Plank et al., 2014). Since their voice varies according to individuals' proficiency level, self-efficacy, teacher-learner relationship and other factors (Winstone et al., 2017), it is imperative for teachers to have a thorough understanding of individual learners and be flexible in making response. While a written reply to recognize achievements may suffice for capable learners (Vignette A), low self-efficacious learners may benefit more from verbal exchange to build confidence in judgment making before discussing performance gaps and brainstorming suggestions (Vignette C). To support this type of learners, teachers could consider adopting Fletcher's (2018) practice, engaging students with similar needs in feedback consultation meetings during lessons.

A controversy over feedback practices in exam-oriented settings centers on the timing of grade release—whether students should receive grades and comments simultaneously. Our position is that educators should take account of students' emotional maturity, learning orientations and academic experiences in decision making. If students are achievement-oriented and resilient to negative emotions, they could regard unsatisfactory results as an opportunity to readjust learning efforts (also known as attention deployment strategy, see Harley et al.'s (2019) emotion regulation model for details). Given the circumstances, the concurrent release of grades and comments may not hamper their engagement with feedback but contribute to self-regulated learning. However, for younger kids who are unable to cope with negative affect, educators had better provide them with comments and guide them to reflect on the given information prior to grade release (cf. Irwin et al., 2013). Along with the adaptive release of grades, educators are highly encouraged to strengthen students' emotion regulation through discussing the meaningful use of grades and comments for academic regulation, developing their resilience to negative feedback (To, 2016), and nurturing their growth mindset through classroom interaction (Ramani et al., 2019).

Supporting students to make feedforward is significant for feedback designs. From this study, we learn that simply understanding students' difficulties in feedback uptake is far from adequate to support feedforward. What seems useful would be the employment of discipline-specific strategies to enable students' transfer of cognitive skills and feedback insights. While language teachers may adopt the draft-plus-rework design to create opportunity for feedforward (e.g., Fletcher, 2018; To et al., 2023b), this may not suit Social Studies teachers due to the context-dependent nature of case study questions and the emphasis of higher-order thinking skills. Informed by the findings in Section 4.3.3, it would be more beneficial to engage students in reciprocal verbal exchange where dialogic feedback could stimulate their thinking, aid their analysis of task context, and expand their zone of proximal development (Alexander, 2020; Vygotsky, 1978). This may imply the need to revisit the existing subject curriculum to find lesson time for meaningful feedback dialogue.

5.3 Limitations and future research

This study has three limitations. First, our discovery of student voice is far from comprehensive since the sample is confined to a small group of upper secondary school learners in a Singapore school. Those in junior secondary with less exam pressure may have different expectations and perspectives on feedback. Future research could compare student voice in various academic contexts and identify the factors influencing their opinions. Second, the feedback redesign for Social Studies may not be suitable for languages, mathematics and other subjects as feedback practices are shaped by the discipline-specific features in pedagogy and assessment (Carless et al., 2023; Quinlan and Pitt, 2021). It would be fruitful for researchers to explore the feedback characteristics of various subjects so that insights into discipline-specific feedback designs could be gleaned. Third, due to the school's exam preparation work in Term 4, we could not conduct a follow-up investigation to see if the inclusion of verbal dialogue would improve students' understanding and uptake of feedback. This issue could have been circumvented if we had factored in the school's exam preparation period when planning for data collection. It would be beneficial for researchers to have forward planning with participating schools to ensure data collection work for two consecutive terms.

6 Conclusion

Engaging students in feedback is challenging when learners' needs and voice are unknown to teachers. To tackle this issue, this paper has discussed how teachers could identify and address student voice in feedback processes. In collaboration with the Social Studies subject team, we developed a feedback log for students to express their competence and relational needs during feedback processes. From the findings, we have learnt that this feedback tool grants students autonomy to articulate task goals, emotions, and self-reflections. However, the centrality of dialogic feedback lies in teachers' fulfillment of learners' needs through verbal reciprocal exchange to develop their confidence in judgment making and higher-order thinking skills for feedforward.

Provided that one size does not fit all, we do not intend to present our feedback design as the solution to the feedback conundrum. By delineating the subject team's considerations and student voice in feedback processes, we wish to provide researchers and practitioners with insights so that they could design their own feedback practice to identify and meet their students' needs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Nanyang Technological University, Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s), and minor(s) legal guardian/next of kin, for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KT: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research work was supported by NIE Planning Grant, Singapore Ministry of Education (Project Title: Developing a Pedagogy of Feedback; Grant Number: PG 15/22 THKK).

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Principal, Social Studies Professional Development Team and student participants of Edgefield Secondary School for their unswerving support to our project and sharing their perspectives with us.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^In Singapore, there are four school terms in a year (Term 1: early January to mid-March; Term 2: mid-March to late May; Term 3; late June to early September; Term 4: mid-September to late November). Each term lasts for ~10 teaching weeks.

2. ^All the authors worked at National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University when the research was undertaken.

References

Adie, L., van der Kleij, F., and Cumming, J. (2018). The development and application of coding frameworks to explore dialogic feedback interactions and self-regulated learning. Br. Educ. Res. J. 44, 704–723. doi: 10.1002/berj.3463

Alhadabi, A., and Karpinski, A. (2019). Grit, self-efficacy, achievement orientation goals, and academic performance in university students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 519–535. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1679202

Banegas, D., Pavese, A., Velazquez, A., and Velez, S. M. (2013). Teacher professional development through collaborative action research: impact on foreign English language teaching and learning. Educ. Action Res. 21, 185–201. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2013.789717

Barnett, S. M., and Ceci, S. J. (2002). When and where do we apply what we learn?: a taxonomy for far transfer. Psychol. Bull. 128, 612–637. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.612

Boud, D., and Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 38, 698–712. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual. Res. J. 9, 27–40. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative Action Research for English Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carless, D. (2011). From Testing to Productive Student Learning: Implementing Formative Assessment in Confucian-Heritage Settings. New York, NY: Routledge.

Carless, D. (2012). “Trust and its role in facilitating dialogic feedback,” in Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding and Doing it Well, eds. D. Boud, and E. Molloy (London: Routledge), 90–103.

Carless, D. (2020). Longitudinal perspectives on students' experiences of feedback: a need for teacher–student partnerships. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 39, 425–438. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2019.1684455

Carless, D., To, J., Kwan, C., and Kwok, J. (2023). Disciplinary perspectives on feedback processes: towards signature feedback practices. Teach. Higher Educ. 28, 1158–1172. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1863355

Chong, D. Y. K., and McArthur, J. (2021). Assessment for learning in a Confucian-influenced culture: beyond the summative/formative binary. Teach. Higher Educ. 28, 1395–1411. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1892057

Cook-Sather, A. (2006). Sound, presence, and power: ‘student voice' in educational research and reform. Curriculum Inquiry 36, 359–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2006.00363.x

Deneen, C. C., Fulmer, G. W., Brown, G. T., Tan, K. H. K., Leong, W. S., and Tay, H. Y. (2019). value, practice and proficiency: Teachers' complex relationship with assessment for learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 80, 39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.12.022

Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54, 5–12. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5

Fletcher, A. K. (2018). Help seeking: agentic learners initiating feedback. Educ. Rev. 70, 389–408. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2017.1340871

Hargreaves, E. (2013). Inquiring into children's experiences of teacher feedback: reconceptualising assessment for learning. Oxford Rev. Educ. 39, 229–246. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2013.787922

Harley, J. M., Pekrun, R., Taxer, J. L., and Gross, J. J. (2019). Emotion regulation in achievement situations: An integrated model. Educ. Psychol. 54, 106–126. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1587297

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Irwin, B., Hepplestone, S., Holden, G., Parkin, H. J., and Thorpe, L. (2013). Engaging students with feedback through adaptive release. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 50, 51–61. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2012.748333

Johnson, C. E., Keating, J. L., and Molloy, E. K. (2020). Psychological safety in feedback: what does it look like and how can educators work with learners to foster it?. Med. Educ. 54, 559–570. doi: 10.1111/medu.14154

Lederman, L. C. (1990). Assessing educational effectiveness: the focus group interview as a technique for data collection. Commun. Educ. 38, 117–127. doi: 10.1080/03634529009378794

Lee, I., and Coniam, D. (2013). Introducing assessment for learning for EFL writing in an assessment of learning examination-driven system in Hong Kong. J. Second Lang. Writing 22, 34–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2012.11.003

Lipnevich, A. A., and Smith, J. K. (2009). Effects of differential feedback on students' examination performance. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 15, 319–333. doi: 10.1037/a0017841

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice' is not enough: conceptualising article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 927–942. doi: 10.1080/01411920701657033

Matthews, K. E., Tai, J., Enright, E., Carless, D., Rafferty, C., and Winstone, N. (2023). Transgressing the boundaries of ‘students as partners' and ‘feedback' discourse communities to advance democratic education. Teach. Higher Educ. 28, 1503–1517. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1903854

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A, M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Ministry of Education (2019). Report of the Primary Education Review and Implementation Committee. Avaialble at: https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/index.php/2009/report-primary-education-review-and-implementation-peri-committee-5141 (accessed April 23, 2025).

Ministry of Education (2022). Removal of Mid-year Exams Will Help Nurture Joy for Learning. Avaialble at: https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/forum-letter-replies/20220317-removal-of-mid-year-exams-will-help-nurture-joy-for-learning (accessed October 14, 2024).

Mulliner, E., and Tucker, M. (2015). Feedback on feedback practice: perceptions of students and academics' Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 42, 266–288. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1103365

Nicol, D., and McCallum, S. (2022). Making internal feedback explicit: exploiting the multiple comparisons that occur during peer review. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 47, 424–433. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1924620

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory Res. Educ. 7, 133–144. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104318

Nunan, D., and Bailey, K. M. (2009). Exploring Second Language Classroom Research: A Comprehensive Guide. Boston, MA: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Plank, C., Dixon, H., and Ward, G. (2014). Student voices about the role feedback plays in the enhancement of their learning. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 98–110. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n9.8

Pricinote, S., Pereira, E., Costa, N., and Fernandes, M. (2021). The meaning of feedback: medical students' view. Rev. Brasil. Educação Méd. 45:e139. doi: 10.1590/1981-5271v45.3-20200517.ing

Quinlan, K. M., and Pitt, E. (2021). Towards signature assessment and feedback practices: a taxonomy of discipline-specific elements of assessment for learning. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Prac. 28, 191–207. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2021.1930447

Ramani, S., Könings, K. D., Ginsburg, S., and van der Vleuten, C. P. (2019). Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med. Teach. 41, 625–631. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432850

Ratnam-Lim, C. T. L., and Tan, K. H. K. (2015). Large-scale implementation of formative assessment practices in an examination-oriented culture. Assess. Educ. Principles Policy Prac. 22, 61–78. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2014.1001319

Reynaert, D., Bouverne-de-Bie, M., and Vandevelde, S. (2009). A review of children's rights literature since the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Childhood 16, 518–534. doi: 10.1177/0907568209344270

Rudduck, J., and McIntyre, D. (2007). Improving Learning Through Consulting Pupils. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203935323

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Publishing. doi: 10.1521/978.14625/28806

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61:101860. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Shen, B., Lin, Z., and Xing, W. (2024). Chinese English-as-a-foreign-language learners' directed motivational currents for high-stakes English exam preparation. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 35, 436–456. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12629

Steen-Utheim, A., and Wittek, A. L. (2017). Dialogic feedback and potentialities for student learning. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 15, 18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.06.002

Suri, H. (2011). Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 11, 63–75. doi: 10.3316/QRJ1102063

Tan, K. (2011). Assessment for learning reform in Singapore–quality, sustainable or threshold?. Assess. Reform Educ. Policy Prac. 75–87. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0729-0_6