- 1Institute for Advanced Studies, Universiti Malaya, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 2Department of Educational Psychology and Counselling, Faculty of Education, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 3Department of Social Administration and Justice, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- 4Nanchang Institute of Science and Technology, Nanchang, China

This study examines how mentor teachers and teacher emotions influence the professional identity and career choices of preservice preschool teachers in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China. A quantitative approach was adopted, with data collected from 230 preservice preschool teachers through validated questionnaires. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to examine the relationships between mentor support, teacher emotions, professional identity, and career choice. Results revealed that mentor support significantly enhanced both professional identity and career decisions, with teacher emotions serving as both mediators and moderators in these relationships. These findings underscore the critical role of mentorship and emotional experiences in shaping career readiness and professional identity, highlighting the need for teacher education programs to integrate emotional support within mentorship frameworks to better prepare preservice teachers for their future roles.

Introduction

The development of professional identity is essential for preservice teachers, influencing their motivation, teaching effectiveness, and long-term commitment to the teaching profession Cai et al. (2022). Among these, mentorship by experienced teachers plays a critical role in guiding preservice teachers during their formative teaching experiences. Mentor teachers offer both practical guidance and emotional support, creating opportunities for reflection on professional growth, which are key to developing professional identity and career aspirations. Recent studies have extended this understanding: Cai et al. (2022) demonstrated that teaching internships enhance professional identity via increased self-efficacy and engagement, while Wang et al. (2025) found that richer internship experiences fostered preservice teachers’ career adaptability (concern, control, curiosity).

Teaching internships play a pivotal role in transforming professional identity by providing preservice teachers with practical experience and enhancing their self-efficacy and engagement (Sökmen, 2021). Wang et al. (2025) found that richer internship experiences significantly improved preservice teachers’ career adaptability-specifically concern, control, and curiosity-over time. Drawing on Lave Communities of Practice theory (Lave, 1991), internships operationalize legitimate peripheral participation, allowing novices to adopt the practices of experienced educators.

This study incorporates the Emotional Labor framework to examine how emotional experiences during mentorship interactions impact career choice and identity development. Although existing research has extensively examined the impact of teaching internships on professional identity, there is limited exploration of the combined roles of mentor teachers and teacher emotions in this process.

Peng et al. (2023) showed that deep acting—genuine emotion regulation—predicts greater teacher well-being and commitment, highlighting the importance of emotional strategies in teacher development. Su et al. (2025) further revealed that preschool teachers’ well-being promotes their emotional labor via enhanced career commitment, with social support strengthening this effect. Simon and Dan (2025) report that kindergarten student-teachers view mentors as both pedagogical and emotional role models, underscoring mentorship’s dual impact in early childhood settings. Bastian et al. (2024) confirmed that mentor emotional support significantly improves preservice teachers’ in-class decision-making skills.

Although existing research has extensively examined the impact of teaching internships on professional identity, there is limited exploration of the combined roles of mentor teachers and teacher emotions in this process. Zhang et al. (2025) demonstrated that effective emotion regulation can alleviate “reality shock” among Chinese ECE interns and support robust identity construction. This study aims to fill this gap by addressing two primary questions:

1. How do mentor teachers influence the professional identity and career choice of preservice preschool teachers?

2. What role do teacher emotions play in mediating and moderating these relationships?

By integrating the Communities of Practice and Emotional Labor frameworks, this research aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying preservice teachers’ professional development.

Research gap

Mentor teachers play a vital role in professional development of preservice teachers by providing guidance, feedback, and emotional support, all of which contribute significantly to the formation of professional identity (Beck and Kosnik, 2000; Izadinia, 2015). Previous research has highlighted the importance of mentorship in teacher education, particularly in enhancing preservice teachers’ practical skill and reflective abilities (Lejonberg and Tiplic, 2016).

However, the specific mechanisms by which mentor teachers influence both professional identity and career choices remain underexplored. Furthermore, while emotions are known to profoundly impact teaching practices, professional satisfaction, and retention (Sutton and Wheatley, 2003), their role in mediating the effects of mentorship on career-related outcomes has often been overlooked. Cai et al. (2022) provided evidence for internships’ mediating role via self-efficacy yet did not integrate mentor emotional support into their model.

In teacher education, mentor teachers often act as “more knowledgeable others” (Vygotsky, 1978), guiding preservice teachers through the identity formation process by offering professional and emotional scaffolding. Beyond technical and pedagogical support, mentors frequently address the emotional demands of teaching, thereby helping preservice teachers navigate the emotional labor inherent in the profession (Kruml and Geddes, 2000). Yet, limited research examines how mentors’ emotional support specifically contributes to preservice teachers’ professional identity development and career decision-making, especially in early childhood education. Simon and Dan (2025) highlighted mentors’ combined pedagogical and emotional roles in kindergarten settings, but quantitative tests of these dual effects remain absent.

Early childhood education is a unique and emotionally demanding field where professional identity and emotional support are closely intertwined. High-quality teaching and educator retention in this field are critically dependent on the emotional resilience and professional confidence of teachers. Despite the importance of these factors, the interplay between mentorship, teacher emotions, professional identity, and career choices in early childhood education remains an underexplored area of research. Su et al. (2025) demonstrated emotional labor’s mediation via career commitment among preschool teachers yet did not examine how mentor guidance triggers this pathway. Zhang et al. (2025) documented that effective emotion regulation reduces interns’ negative effect, but its link to mentor support requires further empirical validation.

To address these gaps, this study integrates Hochschild’s Emotional Labor Theory and Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (1977) to examine how mentor teachers and teacher emotions collectively shape professional identity and career choices (Bandura, 1977). Wang et al. (2025) noted that internship and emotion regulation strategies jointly drive career adaptability, suggesting a need for combined modelling of mentor support and emotional processes. By focusing on the emotional and relational dynamics of mentorship during teaching internships, this research aims to develop a nuanced understanding of the factors that influence the career preparedness and long-term commitment of preservice preschool teachers in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China.

Research objective

This study aims to explore the roles of mentor teachers and teacher emotions in shaping of professional identity and career choices of preservice preschool teachers in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China. Specifically, the objectives of this research are:

1. To examine the direct impact of mentor teachers’ support on the professional identity development and career choices of preservice preschool teachers.

2. To investigate the mediating role of teacher emotions in the relationship between mentor support and professional identity formation.

3. To analyze the moderating effect of teacher emotions on the relationship between professional identity and career choice.

4. To utilize structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the direct and indirect relationships among mentor support, teacher emotions, professional identity, and career choice.

By addressing these objectives, this study provides theoretical and practical insights into how mentorship and emotional experiences during internships influence the professional growth and career trajectories of preservice preschool teachers.

Significance of study

By integrating theoretical frameworks such as Communities of Practice, Emotional Labor Theory, and Social Cognitive Theory, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of how social participation and emotional support influence professional identity formation. The findings have significant implications for designing mentor training programs that address both the professional and emotional needs of preservice teachers, particularly in the context of early childhood education, where emotional labor is a significant component of the profession.

Literature review and hypotheses

The role of mentor teachers in shaping professional identity and career choice

Mentorship has long been recognized as a vital component in the professional development of teachers. Effective mentorship not only provides guidance and support but also plays a crucial role in the development of professional identity (Izadinia, 2016). It strongly influences career decisions, especially early in a teacher’s career (Li et al., 2024). Emotional engagement is critical in teaching, a profession demanding high emotional labor (Kruml and Geddes, 2000). In early childhood education, mentors’ emotional support and instructional guidance contribute significantly to preservice teachers’ professional identity and career choices (Orland-Barak and Wang, 2021). Effective mentorship bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application while building the emotional resilience necessary for teaching (Chen and Gu, 2024).

Bandura’s (1977) Social Cognitive Theory further emphasizes the role of observational learning and social interactions in shaping individual attitudes and behaviors (Bandura, 1977). Through mentor interactions, preservice teachers learn effective teaching strategies, professional conduct, and emotional regulation, which strengthen their professional self-concept (Carmi and Tamir, 2023). In other words, mentor teachers serve as role models; their cognitive and emotional strategies help mentees navigate the teaching profession and influence mentees’ career decision-making processes (Burger, 2024).

Empirical studies underscore the importance of mentor support in fostering a positive professional identity and career choice among preservice teachers. Andreasen highlights that mentorship tailored to address both practical and emotional challenges enhances preservice teachers’ confidence and competence (Andreasen, 2023). Similarly, Chen et al. (2023) illustrate that mentors who provide culturally responsive strategies enable preservice teachers to adapt effectively to diverse classroom environments. Strong emotional connections between mentors and mentees create a supportive climate that promotes personal and professional growth (Sigurdardottir and Mork, 2024).

Based on this theoretical and empirical foundation, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Mentor teachers positively influence the professional identity of preservice preschool teachers.

H2: Mentor teachers positively influence the career choice of preservice preschool teachers.

The moderating role of mentor support on teacher emotions

Mentor teachers, through emotional support, help preservice teachers regulate and understand their emotional responses, which in turn influences their professional identity and career choices (Zhang and Jiang, 2023). Emotional Labor Theory suggests that teaching’s emotional demands require effective regulation, which mentor support can facilitate (Kruml and Geddes, 2000). In practice, mentor support provides preservice teachers with the emotional guidance needed to manage challenges and build resilience (Hagenauer et al., 2024).

Research indicates that mentor support is a key factor influencing teacher emotions, which are fundamental to shaping both professional identity and career choice (Zhang and Jiang, 2023). Emotional experiences, whether positive or negative, can significantly affect preservice teachers’ job satisfaction, sense of competence, and long-term career choices. For instance, positive emotions such as enthusiasm and satisfaction foster professional identity development, while negative emotions like stress and frustration can hinder professional growth and lead to career doubts (Moslemi and Habibi, 2019). Mentor teachers who prioritize emotional guidance help mitigate negative emotions, allowing preservice teachers to develop a stronger professional self-concept (Chen et al., 2023). Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Mentor support moderates teacher emotions.

Teacher emotions and their impact on professional identity and career choices

Teacher emotions play a critical role in shaping professional identity and influencing career decisions among preservice teachers. Emotional experiences, whether positive or negative, significantly affect how preservice teachers perceive their roles and responsibilities within the teaching profession (Çetin and Eren, 2022). Positive emotions, such as enthusiasm and satisfaction, are particularly important, as they help to strengthen teachers’ professional identity, increase engagement, and promote perseverance when facing challenges (Chen et al., 2022). Conversely, negative emotions, such as stress and frustration, may lead preservice teachers to question their aptitude for the teaching profession, potentially resulting in career attrition (Moslemi and Habibi, 2019).

In early childhood education, where emotional interactions are fundamental, teacher emotions are deeply intertwined with identity formation and career choice. Positive emotional support, particularly from mentor teachers, can mitigate the effects of negative experiences and foster emotional resilience (Menon, 2020). Mentors who provide emotional and professional guidance create a supportive environment that helps preservice teachers navigate role complexities, thereby enhancing professional identity and long-term career commitment (Zhang and Jiang, 2023).

During internships, emotional satisfaction plays a pivotal role in career decisions. Teachers who experience positive emotional connections with their mentors and peers are more likely to pursue a long-term career in education (Cai et al., 2022). For example, mentorship programs that integrate reflective practices, such as collaborative reflection and peer discussions, can help preservice teachers process their emotional experiences and align them with their professional goals (Chen and Gu, 2024). Emotional resilience gained through such practices not only strengthens professional identity but also influences commitment to the teaching career.

The supports and feedback provided by mentor teachers help preservice teachers navigate the complexities of the teaching profession, fostering a sense of competence and professional self-concept (Stuart and Thurlow, 2000). Mentors also help manage the emotional demands of teaching, fostering a positive professional identity and strengthening commitment to a teaching career (Hagenauer et al., 2024). Zhang and Jiang (2023) argue that emotional connections with mentor teachers help preservice teachers form a clearer sense of their professional self, which influences their career decisions. Chen et al. (2023) add that emotional support from mentors can buffer negative emotional experiences, leading to stronger professional identity and more committed career choices.

Further research shows that such emotional support acts as a buffer against stress, fostering self-efficacy and confidence in preservice teachers (Chen et al., 2022). These findings suggest that emotional support not only enhances professional development but also influences career sustainability in teaching. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Positive teacher emotions enhance the professional identity and career choices of preservice preschool teachers.

Dual roles of teacher emotions in the conceptual model

In the proposed conceptual model, Teacher Emotions play two distinct roles:

Mediator: Mentor support influences teacher emotions, which then affect professional identity formation. According to Emotional Labor Theory and affective-motivational perspectives, mentor behaviors (e.g., constructive feedback, modeling coping strategies, providing psychological safety) affect preservice teachers’ emotional experiences, which in turn foster or hinder professional identity formation (Chen et al., 2023; Kruml and Geddes, 2000; Zhang and Jiang, 2023).

Moderator: A teacher’s emotional state influences how their professional identity translates into career intentions. According to affect-behavior linkage theory, an individual’s current emotional state can amplify or attenuate the effect of their self-concept on behavior: high positive emotions strengthen identity’s impact on career choice, while low or negative emotions weaken it (Cai et al., 2022; Çetin and Eren, 2022; Chen and Gu, 2024).

Based on this model, the following hypotheses are reiterated:

H3: Mentor support moderates teacher emotions.

H4: Positive teacher emotions enhance the professional identity and career choices of preservice preschool teachers.

The impact of teaching internships on professional identity formation

Internships are a crucial phase in teacher education, offering preservice teachers the opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge and develop practical teaching skills in real classroom settings. According to Narayanan et al. (2010), internships are structured as placements where students work within an organization under supervision, sometimes for academic credit. In the context of teacher education, this phase is often referred to as a “teaching practicum” or “student teaching”, depending on the country (Huu Nghia and Tai, 2019).

Teaching internships are recognized for their role in shaping the professional identity of preservice teachers. Westerman (1991) emphasizes that these experiences help preservice teachers transition from theoretical understanding to practical application, bridging the gap between academic preparation and real-world teaching. Internships also provide a platform for preservice teachers to connect with professional educators and explore career development possibilities, aligning their expectations with the realities of the profession (Cohen et al., 2002; Huu Nghia and Tai, 2019).

Internships not only influence professional identity directly but also affect other factors like self-efficacy and learning engagement, which in turn shape professional identity (Burger, 2024). For instance, Burger (2024) found that teaching practice during internships indirectly impacted preservice teachers’ self-efficacy, which is a crucial element in the development of professional identity (Cai et al., 2022; Moslemi and Habibi, 2019). In sum, internships are integral to professional identity formation and should be considered in understanding how preservice teachers develop their professional selves.

Methodology

Research design

This study employs correlational research design to examine relationships between key variables (Wallen and Fraenkel, 2013). We focus on the impact of mentor support on preschool teachers’ professional identity and career choice of preservice preschool teachers. Specifically, mentor support, as an independent variable, encompasses the mentor’s role in providing both instructional guidance and emotional support, which influences the development of professional identity and career choice by shaping teachers’ emotional experience.

To further explore the role of emotions in this process, this study also used teacher emotions as a mediating variable. Teacher emotions refer to various emotional reactions that teachers have during interactions with mentors, such as the acquisition of emotional support, the formation of emotional connections, etc. These emotional experiences will further regulate the relationship between mentor support, professional identity, and career choice. The dependent variables were mentor teachers and teacher emotions. Independent variables were professional identity and career choice.

Sample of the study

This study involved 230 preservice preschool teachers from Nanchang, Jiangxi Province. Of these, 95.7% (N = 220) were female and 4.3% (N = 10) were male. Stratified random sampling was employed to ensure representation across private institutions offering early childhood education. From the ten universities in Nanchang with preschool-education major, we selected the four private institutions relevant to our research focus. These four universities together enroll 547 preservice preschool teachers. Following Creswell and Creswell (2017), stratified sampling was used to improve representativeness and reduce sampling error when the population can be divided into distinct subgroups. Accordingly, preservice teachers were divided into four strata based on their institution, and within each stratum participants were randomly selected to ensure that each private university was proportionally represented (Etikan and Bala, 2017).

A prior sample-size calculation based on Krejcie (1970) indicated that 226 respondents would be sufficient for our analyses; we ultimately collected 230 valid responses, yielding a 99.5% response rate. Ethical approval was granted by the University Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC). All participants provided informed consent, remained anonymous, and retained the right to withdraw at any time. Questionnaires were administered in Chinese.

Measurement instruments and translation procedures

The study employed four established instruments to assess key variables: mentor support, teacher emotions, professional identity, and career choice. All scales were adapted from previous research and measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree).

Mentor support

Adapted from Galamay-Cachola et al. (2018), this scale measures the perceived support from mentor teachers during the internship. This questionnaire had 10 items, α = 0.843; two dimensions: Instructional Practice (6 items; loadings: 0.691–0.899) and Values & Reflection Support (4 items; loadings: 0.740–0.850).

Teacher emotions

Adapted from Frenzel et al. (2010) and Hascher and Hagenauer (2016), this scale measures the emotional experiences of preservice teachers during their teaching internships. This questionnaire had 15 items, α = 0.886; four dimensions: Positive Emotions (5; 0.680–0.896), Emotional Fluctuation (4; 0.832–0.902), Teaching Performance Impact (3; 0.516–0.849), Negative Emotions (3; 0.585–0.866).

Professional identity

Adapted from Liu and Keating (2022), this scale assesses the professional identity of preservice teachers. This questionnaire had 15 items, α = 0.879; three dimensions: Intrinsic Value (7; 0.564–0.864), Career Future (4; 0.511–0.841), Social Status (4; 0.623–0.700).

Career choice

Adapted from Richardson and Watt (2006), this questionnaire explores factors influencing the career decisions of preservice teachers. This questionnaire had 14 items, α = 0.853; three dimensions: Intrinsic Motivation & Fit (7; 0.568–0.792), Career Conditions & Inspiration (4; 0.588–0.818), Social Encouragement (3; 0.585–0.878).

All items were originally developed in English and underwent a rigorous translation and cultural adaptation process. A forward–backward translation method was used: two bilingual researchers independently translated the scales into Chinese, followed by back-translation by two additional bilingual experts. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion to ensure conceptual and semantic equivalence. A pilot study with 30 preservice preschool teachers was conducted to assess clarity, readability, and cultural appropriateness.

Construct validity was supported via Principal Component Analysis (Varimax rotation) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (χ2/df ≈ 3.3, CFI ≈ 0.93, RMSEA ≈ 0.09–0.10), indicating satisfactory measurement properties. Measurement Instruments questionnaire is provided in Supplementary material.

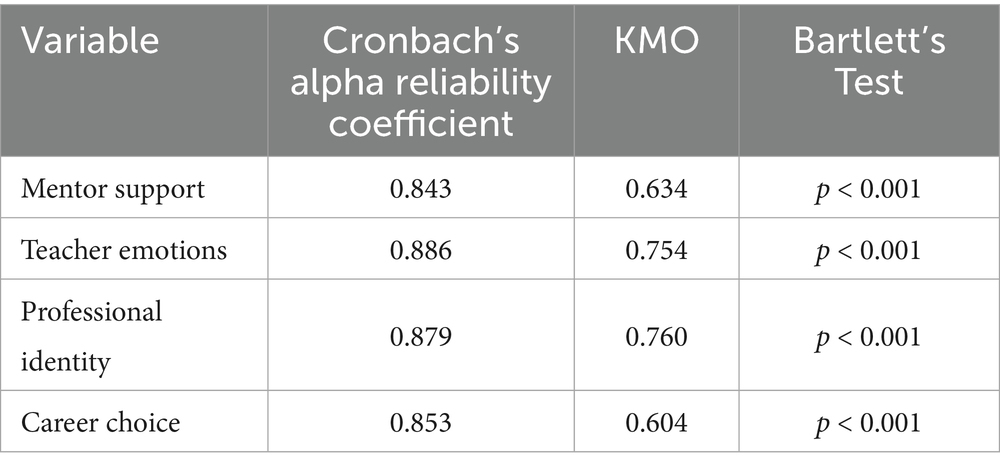

Pilot study data analysis

A pilot study was conducted to test the reliability and validity of the questionnaire before formal data collection. A total of 30 valid responses were collected, and reliability and validity analyses were performed for each dimension by SPSS. The results are as follows Table 1:

In summary, the pilot study results demonstrate that the questionnaire has good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.8) and appropriate validity (KMO > 0.6, Bartlett’s test significantly). Given the preliminary nature of the pilot study, the KMO and Bartlett’s Test were used solely to assess the data’s suitability for factor analysis, not to perform a full-scale EFA. The small sample (N = 30) was intended only to confirm the reliability of the scales and identify potential issues before the main study. These findings indicate that the questionnaire is a reliable tool for measuring the constructions of this study, providing a solid foundation for formal data collection.

Data analysis

Sub-dimensional regression analysis

Firstly, based on SPSS Principal Component Analysis (PCA, Varimax rotation), two sub-dimension factor scores for ‘Instructor Support’ (Instructional Practice, Values & Reflection Support) and four sub-dimension factor scores for ‘Teacher Emotions’ (Positive Emotions, Emotional Fluctuation, Teaching Performance Impact, and Negative Emotions) were extracted and analyzed. The factor scores were saved as new variables. Then, a linear regression analysis was conducted on the following three outcome variables: ProfessionalIdentity_Total, CareerChoice_Total and TeacherEmotions_Total. The two sub-dimension factor scores were used as the dependent variables, respectively, in order to compare the relative impacts among the sub-dimensions.

Structural equation modelling (SEM)

A four-latent-variable structural equation model (SEM) was constructed using AMOS 24 to test hypotheses H1–H4. The fit of the measurement model was assessed using χ2/df, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. The significance of the path coefficients in the structural model was evaluated using z-statistics and p-value tests (Hu and Bentler, 1999). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS and AMOS version 24. Mediating effects were assessed using the percentile bootstrap method (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

Results

Descriptive statistics and reliability and validity

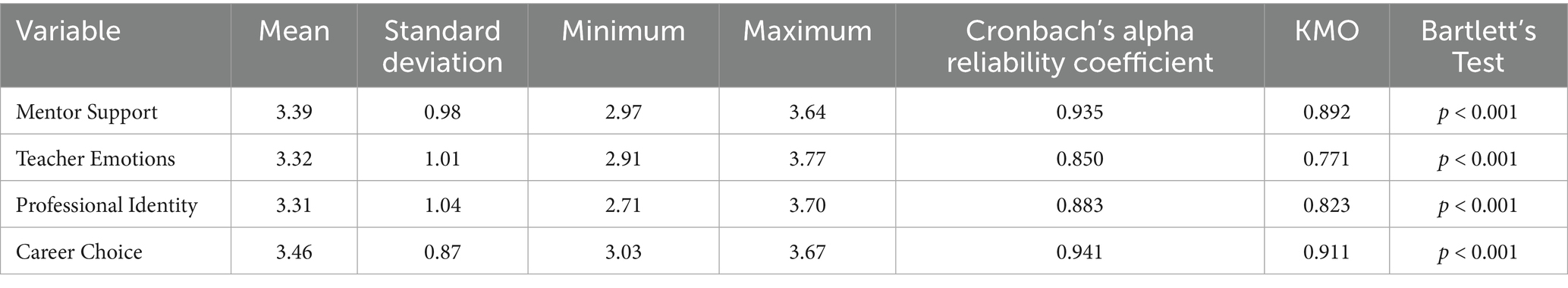

Present basic descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and demographic breakdowns of the sample. Before conducting the structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis, basic descriptive statistics were calculated to provide an overview of the data collected by SPSS. These statistics include means, standard deviations, and frequency distributions for the key variables in the study: mentor teacher support, teacher emotions, professional identity, and career choice. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the 230 preservice preschool teachers surveyed.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between variables under study. The mean scores for mentor support and career choice are higher than the medians, indicating generally positive perceptions in these areas. However, the mean scores for teacher emotions and professional identity are lower than the median, suggesting greater variability in these dimensions. Overall, the bivariate correlations align with our expectations, showing significant relationships between all variables.

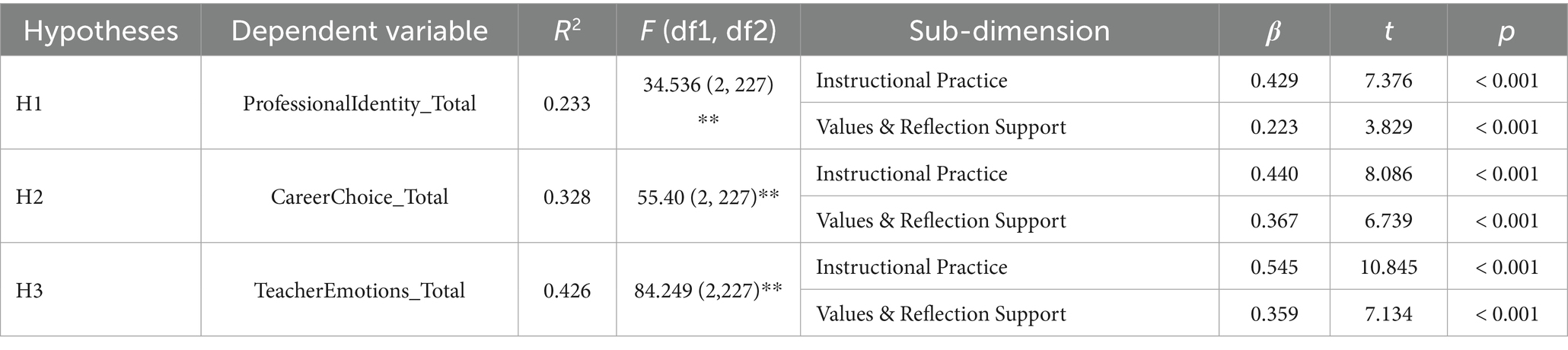

Results of sub-dimension regression and ANOVA

Regression Analysis of the Instructor Support Sub-Dimension on Hypotheses 1–3 We utilized Instructional Practice and Values & Reflection Support as independent variables to predict ProfessionalIdentity_Total, CareerChoice_Total, and TeacherEmotions_Total, respectively. R2: the proportion of variance explained by the model; F: ANOVA overall test, “**” in the table means p < 0.001; β: standardized regression coefficient, reflecting the relative influence of sub-dimensions. Table 3 summarizes the regression coefficients, the coefficient of determination (R2), and the ANOVA results.

Table 3. Summarizes the regression coefficients, the coefficient of determination (R2), and the ANOVA results.

As shown in Table 3, the impact of Instructional Practice on the three outcomes is significant and more pronounced than that of Values and Reflection Support. This indicates that the instructors’ actual teaching actions are more effective than their values and reflective support.

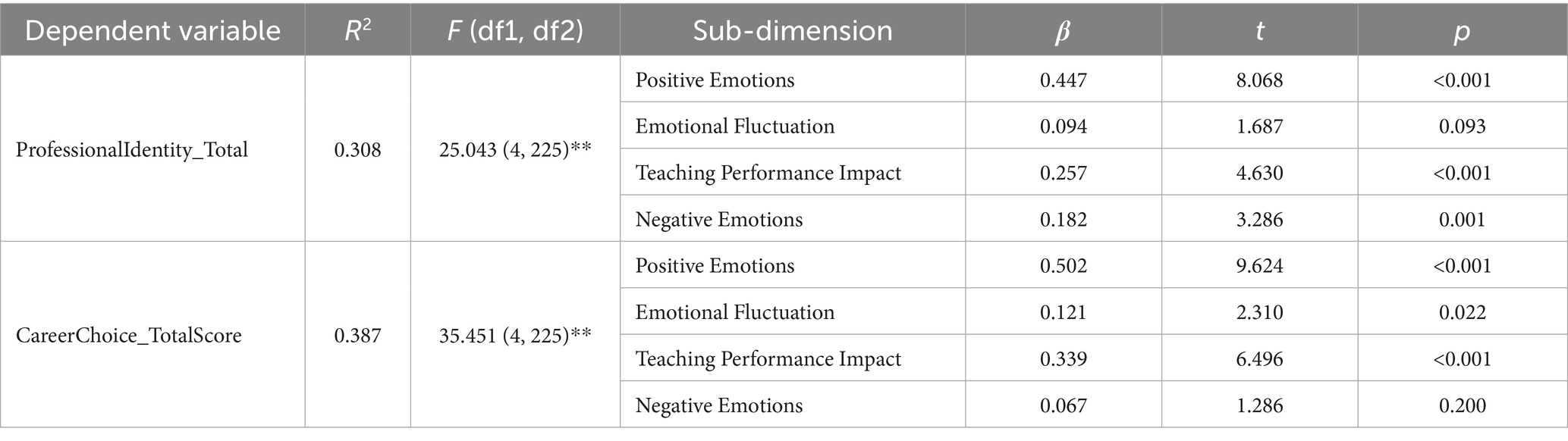

Regression analysis of teacher emotion sub-dimensions on hypothesis 4

Next, the factor scores of the four sub-dimensions of teacher emotion were utilized as independent variables to predict ProfessionalIdentity_TotalScore and CareerChoice_TotalScore, respectively (see Table 4).

As shown in Table 4, Emotional fluctuation did not have a significant impact on career identity and career choice (p = 0.093, 0.200). However, positive emotions and teaching performance both had significant positive effects on these two outcome variables.

Testing hypotheses with individual SEM models

Model fit analysis

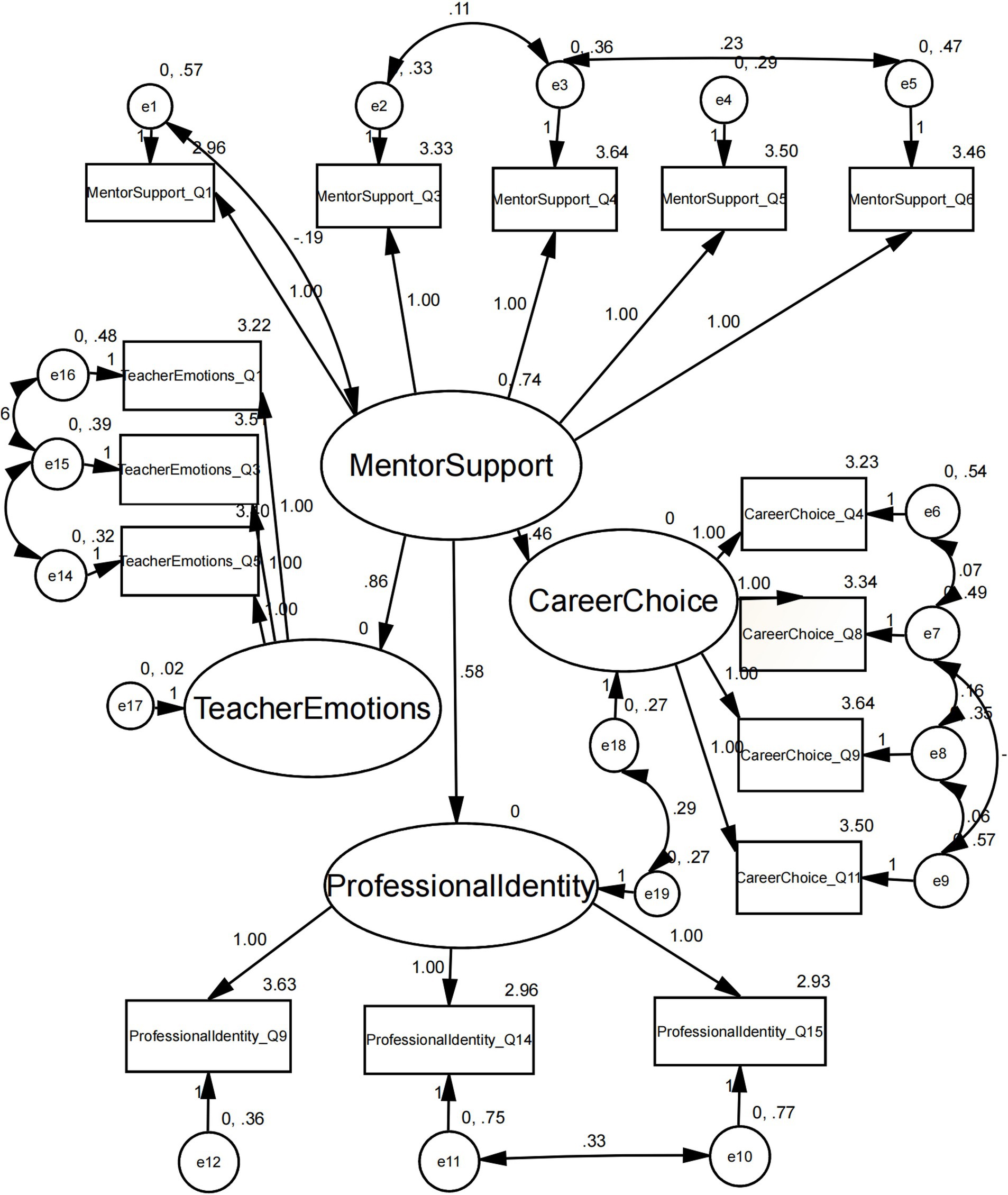

Figure 1 presents the SEM model for Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3:

Figure 1. Structural equation model testing hypotheses 1–3. Standardized path coefficients are shown. All paths were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Mentor teachers positively influence the professional identity of preservice preschool teachers. The path coefficient from mentor support to professional identity is 0.58, suggesting that mentor teachers have a significant positive impact on the professional identity of preservice teachers.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Mentor teachers positively influence the career choice of preservice preschool teachers. The path coefficient from mentor support to career choice is 0.46, indicating that mentor teachers also have a significant positive effect on the career choice of preservice teachers.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Mentor support moderates teacher emotions. Mentor support’s moderating role in teacher emotions is quite significant, with a path coefficient of 0.86. This indicates that mentor support has a strong moderating effect on teacher emotions.

Overall, these indices indicate an acceptable model fit, supporting the hypothesized positive effects of mentor support on professional identity, career choice, and its moderating role on teacher emotions.

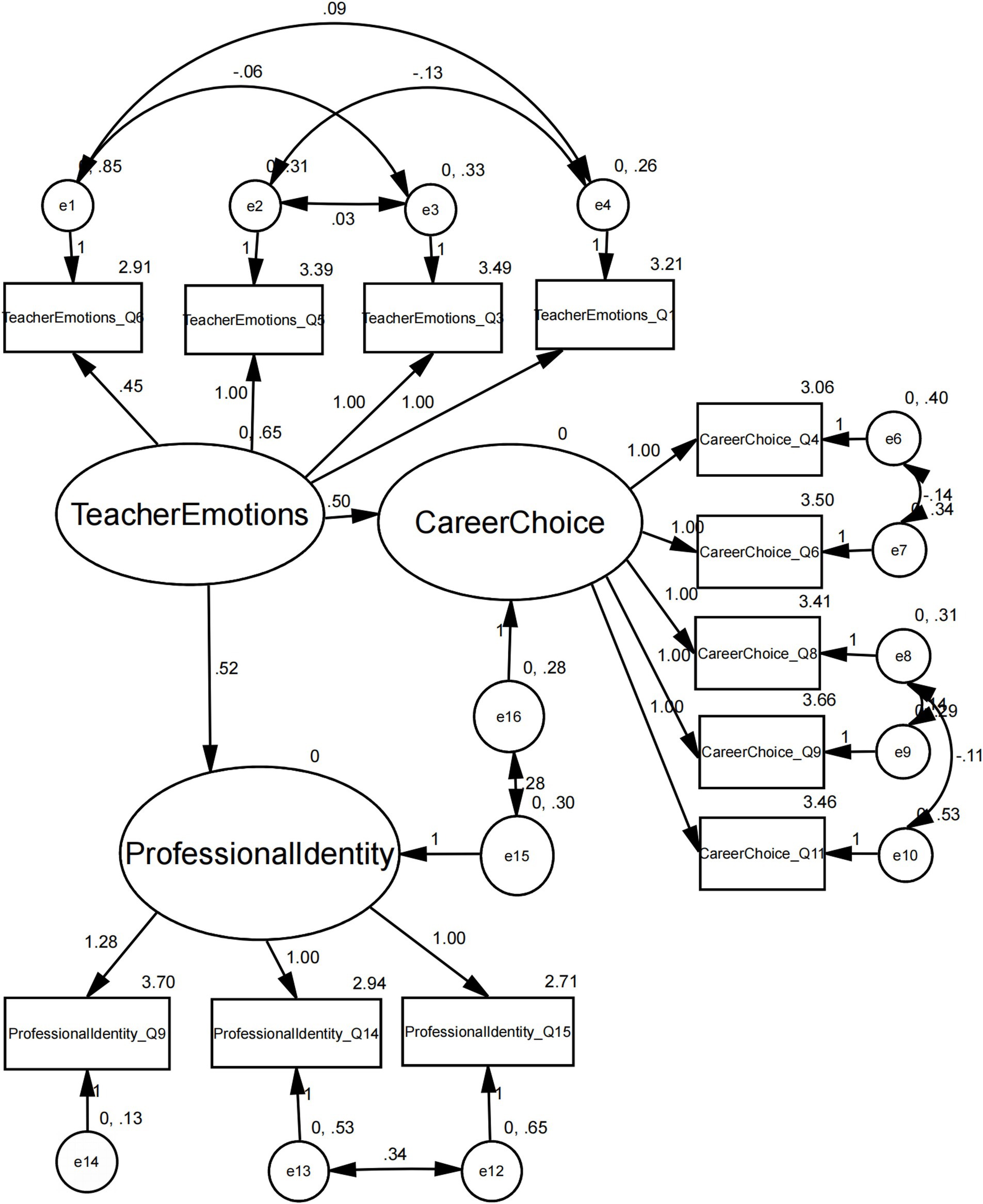

Figure 2 presents the SEM model for Hypothesis 4, which examines the moderating effect of teacher emotions on the link from professional identity to career choice. Results show that teacher emotions → professional identity has a path coefficient of 0.52 (SE = 0.068, CR = 7.643, p < 0.001), and teacher emotions → career choice has a path coefficient of 0.50 (SE = 0.057, CR = 8.810, p < 0.001), both indicating significant positive effects.

Figure 2. Structural equation model testing hypotheses 4. Standardized path coefficients are shown. All paths were statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Fit indices for this model were: CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.888, SRMR = 0.061, and RMSEA = 0.101 (90% CI [0.093, 0.109]). While CFI > 0.90 and SRMR < 0.08 meet standard benchmarks, and TLI is only slightly below 0.90, the RMSEA of 0.101 exceeds the ideal cutoff of 0.08 and therefore warrants further discussion.

Although RMSEA is one of the most widely reported fit indices, it is particularly sensitive to degrees of freedom and sample size. With a moderate sample (N = 230) and the inclusion of an interaction term (ProfessionalIdentity × TeacherEmotions), the model’s degrees of freedom decrease, which can inflate RMSEA values (Kenny et al., 2015). Moreover, complex relationships in models with limited freedom often lead RMSEA to overestimate misfit (Shi et al., 2019).

Nevertheless, the convergence of multiple indices—including a strong CFI, acceptable TLI, and low SRMR—indicates that Figure 2 effectively captures the core theoretical mechanism. All path coefficients were statistically significant and aligned with theoretical expectations, reinforcing the model’s validity.

In sum, although RMSEA = 0.101 exceeds the conventional threshold, such values are not uncommon in complex SEMs involving moderation. We interpret this as evidence of a reasonable rather than perfect fit.

Discussion and conclusion

Mentor teachers and professional identity

Hypothesis 1 (H1) analysis showed that mentor teachers significantly influence the professional identity of preservice preschool teachers. The path coefficient between mentor support and professional identity was found to be 0.58, indicating a moderate to strong positive effect. The regression analysis (Table 3) indicates that Instructional Practice (β = 0.429, p < 0.001) has a significantly stronger impact on professional identity than Values & Reflection Support (β = 0.223, p < 0.001). This model accounts for a variance of R2 = 0.233. Previous literature has also highlighted that mentors’ behaviors, such as classroom demonstrations and hands-on guidance, are more effective in enhancing the professional belonging and self-efficacy of student teachers compared to merely providing ideological support (Liu and Onwuegbuzie, 2012). This finding aligns with existing literature emphasizing the crucial role of mentor teachers in shaping professional identity (Izadinia, 2016).

Therefore, teacher education programs should prioritize the development of mentors’ “learning by doing” guidance skills. This approach encourages mentors to strengthen the professional identity and teaching confidence of intern teachers through collaborative lesson planning and demonstration teaching. Mentor teachers offer guidance, model effective teaching behaviors, and provide feedback, which can positively influence how preservice teachers view themselves as educators. This process, often referred to as socialization, helps to reinforce professional norms and values that are essential to developing a coherent professional identity. Given the significant path coefficient in the SEM model, it can be concluded that the role of mentor teachers should be prioritized in teacher education programs to foster a supportive environment for identity development.

Mentor teachers and career choice

In line with Hypothesis 2 (H2), the SEM results demonstrate that mentor teachers also exert a significant positive influence on career choice, with a path coefficient of 0.46. The regression results (Table 3) indicate that Instructional Practice (β = 0.440, p < 0.001) has a more significant impact on career choice than Values & Reflection Support (β = 0.367, p < 0.001), with an R2 value of 0.328. This finding aligns with the study conducted by Ben-Amram and Davidovitch (2024), which revealed that specific guidance and feedback provided by mentors during field teaching assist intern teachers in developing a clearer understanding of their career paths, thereby enhancing their long-term commitment to the teaching profession.

Educational administrators and policymakers should implement systematic mentor training programs that focus on improving mentors’ skills in providing classroom practice guidance, thereby strengthening and enhancing the professional commitment of intern teachers. This suggests that mentor support is crucial in guiding preservice preschool teachers toward making informed and confident career decisions. The relationship between mentor teachers and career choice is grounded in the notion that mentors provide both emotional and professional guidance that helps students navigate the challenges of the teaching profession (Ben-Amram and Davidovitch, 2024).

Mentors often serve as role models, demonstrating not only the day-to-day responsibilities of the job but also the personal satisfaction and rewards that come with teaching. This can be particularly influential for preservice teachers, who may still be exploring their professional aspirations. The positive influence of mentors in shaping career choices is in line with the growing body of research suggesting that mentoring relationships are fundamental in reinforcing career trajectories, particularly in fields like education, where personal fulfillment is closely tied to professional success.

By providing career guidance, mentors help preservice teachers gain clarity on the long-term benefits and challenges associated with the profession, which can solidify their commitment to their chosen career path. Thus, mentor teachers play a pivotal role not just in the development of teaching skills but also in solidifying career goals.

Mentor support and teacher emotions

Hypothesis 3 (H3) posited that mentor support moderates teacher emotions, and the SEM results corroborate this hypothesis. The path coefficient for mentor support’s moderating effect on teacher emotions was found to be 0.86, which is a substantial coefficient, indicating that mentor support plays a significant role in regulating and supporting the emotional well-being of preservice teachers. Regarding H3, the impact of mentor support on the sub-dimensions of teacher emotions is also uneven (Table 3). Instructional Practice (β = 0.545, p < 0.001) has a significantly stronger positive regulatory effect on teacher emotions compared to Values & Reflection Support (β = 0.359, p < 0.001), with R2 = 0.426. This finding supports the emphasis of Diab and Green (2024), which suggests that mentors, through their companionship and demonstration in real classroom situations, can more effectively assist interns in developing emotional regulation skills and mitigating teaching stress. Based on this, normal universities and preschool education institutions should incorporate the roles of mentors in “immersive” guidance activities, such as situational simulations and co-teaching, into the mentor evaluation and assessment system to enhance the effectiveness of their emotional support.

This finding is consistent with prior research that highlights the importance of mentor support in helping teachers cope with the emotional challenges of the profession (Diab and Green, 2024). Teacher emotions are often influenced by the demands of the teaching profession, especially during the early stages of a teacher’s career. The emotional strain can stem from various sources such as classroom management, student relationships, and the pressures of achieving professional expectations. Mentors provide a crucial buffer against these stressors by offering advice, emotional support, and reassurance, which helps teachers develop emotional resilience. The strong path coefficient indicates that mentor support is a key factor in fostering positive emotional development among preservice teachers, enhancing their capacity to handle the emotional demands of the profession.

Positive teacher emotions as professional identity and career choices mediators

Finally, Hypothesis 4 (H4) examined the role of teacher emotions as mediators between mentor support and both professional identity and career choice. The SEM analysis revealed that positive teacher emotions significantly enhance both professional identity (β = 0.516) and career choice (β = 0.500), indicating that teacher emotions serve as a key mediator in these relationships. In the regression analysis of Hypothesis 4 (Table 4), we found that Positive Emotions (β = 0.447, p < 0.001) and Teaching Performance Impact (β = 0.257, p < 0.001) have a significant positive effect on professional identity, while Emotional Fluctuation has an insignificant effect (β = −0.094, p = 0.093), with R2 = 0.308. In terms of career choice, Positive Emotions (β = 0.502, p < 0.001) and Teaching Performance Impact (β = 0.339, p < 0.001) are also significant, whereas the effects of Emotional Fluctuation and Negative Emotions are weaker or insignificant (β = −0.121, p = 0.022; β = −0.067, p = 0.200), with R2 = 0.387.

These results indicate that positive emotions (such as satisfaction and confidence) are key mediators connecting mentor support with professional identity and career choice, while the effects of emotional fluctuation and negative emotions are limited. Similar to the findings of Zhang et al. (2016), this study further verifies the central role of positive emotions in the construction of teacher identity and the formation of career intentions. Educational programs should incorporate elements that promote positive emotional experiences in mentor training and curriculum design, such as “successful teaching sharing” and “emotional reflection journals,” to enhance the quality of career development for trainee teachers.

Teacher emotions are not only influenced by direct experiences with students or the classroom environment but also by the emotional support they receive from mentors. Positive emotions, such as enthusiasm and confidence, can enhance one’s commitment to the profession and solidify their professional identity, thereby increasing the likelihood of sustained career engagement. The significance of this mediator role emphasizes the need for a holistic approach in teacher education that goes beyond technical skill development to include emotional support and identity formation. By fostering positive emotions through mentor support, teacher education programs can enhance the overall professional development of preservice teachers, ensuring they are better equipped for the emotional and professional challenges of the teaching profession.

Key findings

Differential effects of mentor support subdimensions (H1–H3)

Instructional Practice exerted a significantly stronger influence than Values & Reflection Support across all three outcomes (see Table 1). Specifically, the coefficients were βIP = 0.429 compared to βVRS = 0.223 for professional identity (R2 = 0.233), βIP = 0.440 versus βVRS = 0.367 for career choice (R2 = 0.328), and βIP = 0.545 in contrast to βVRS = 0.359 for teacher emotions (R2 = 0.426). This aligns with the findings of Liu and Onwuegbuzie (2012), who discovered that hands-on mentoring behaviors, such as co-teaching and providing feedback, have a greater impact on preservice teachers’ self-efficacy and professional identity than solely reflective or value-based support.

Overall Effects of Mentor Support (H1–H3). In the SEM, mentor support was found to positively predict professional identity (β = 0.58, p < 0.001), career choice (β = 0.46, p < 0.001), and teacher emotions (β = 0.86, p < 0.001). These results replicate previous findings regarding the crucial role of mentorship in teacher development (Diab and Green, 2024; Izadinia, 2016).

Positive emotions and performance impact as key mediators (H4)

Among the four teacher-emotion subscales, Positive Emotions (β = 0.447, p < 0.001) and Teaching Performance Impact (β = 0.257, p < 0.001) significantly contributed to the explanation of professional identity (R2 = 0.308) and career choice (R2 = 0.387). Emotional fluctuations and negative emotions were found to be non-significant or weak predictors (β = −0.094, p = 0.093; β = −0.121, p = 0.022; β = −0.067, p = 0.200). This suggests that fostering positive emotional experiences during internships is more critical for shaping identity and career intentions than merely reducing stress or variability. This finding corroborates the work of Zhang et al. (2016), which emphasizes the primacy of positive affect in teacher professional development.

Explained Variance and Model Fit. Our combined regression and SEM approach explained between 23 and 43% of the variance in outcomes, which is considered a substantial effect in educational research (Schmidt and Bohannon, 1988). The SEM measurements and structural models exhibited an acceptable fit (Model 1: χ2/df = 3.446, CFI = 0.929, RMSEA = 0.090; Model 2: χ2/df = 3.272, CFI = 0.933, RMSEA = 0.100), further validating the robustness of these relationships.

Implications for educational practice

Teacher education programs should adopt an integrated mentorship model that combines hands-on instructional coaching (e.g., co-planning, modeling, in-class feedback) with structured emotional support (e.g., reflective debriefs, emotion-regulation workshops), since our findings show that practical mentor behaviors drive preservice teachers’ professional identity, career intentions, and emotional resilience more powerfully than value-based guidance alone (Liu and Onwuegbuzie, 2012). By formalizing mentor selection and training standards to include both pedagogical expertise and affective scaffolding, teacher preparation can better equip interns for the dual challenges of classroom practice and emotional well-being.

Conclusion

This study advances our understanding of how mentor support and teacher emotions jointly shape preservice preschool teachers’ professional identity and career trajectories. By combining SEM and detailed sub-dimension analyses, we found that hands-on Instructional Practice by mentors drives interns’ identity formation, career choice, and emotional adjustment far more powerfully than value-modeling or reflective support alone. Moreover, positive emotional experiences—fueled by mentor interaction—serve as pivotal mediators, reinforcing both identity and career intentions.

These findings call for a holistic mentorship paradigm in teacher education—one that marries rigorous pedagogical coaching with structured emotional scaffolding. Such an approach promises to cultivate not only competent but also emotionally resilient educators, better prepared for the complex demands of modern classrooms. Future research should explore longitudinal impacts of hybrid mentorship models and examine how factors like self-efficacy or school culture interact with mentor support and emotions to shape long-term teacher retention and efficacy.

Limitations and future research

This study offers valuable insights into how mentor support and teacher emotions shape professional identity and career choices among preservice preschool teachers, yet several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our sample was drawn exclusively from preservice preschool teachers in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, which, while allowing detailed exploration of local mentorship dynamics, may limit the applicability of findings to other regions or cultural contexts. Future research should adopt multi-site, stratified sampling across diverse geographic and educational settings to enhance external validity (Simon and Dan, 2025; Su et al., 2025).

In addition, the cross-sectional design and reliance on a single-occasion self-report questionnaire introduce potential common method bias; we did not implement procedural controls (such as temporal separation or varied response formats) nor perform statistical checks (e.g., Harman’s single-factor test or marker variable analysis), and we lacked triangulation through interviews, observations, or third-party reports. Subsequent studies could integrate multi-source data—such as mentor evaluations, classroom observations, or physiological measures—to triangulate emotional and identity outcomes (Bastian et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2023).

Finally, although this research focused on teacher emotions as both mediator and moderator, other psychological and contextual factors—such as self-efficacy, resilience, or school climate—were not included, and the moderation model’s RMSEA slightly exceeded conventional thresholds, suggesting room for measurement refinement. Moreover, our models explained only 23.3% of the variance in professional identity and 32.8% in career choice, leaving a substantial proportion of unexplained variance; future work should examine additional predictors, for example preservice teachers’ personality traits, school support structures, or psychological capital (Peng et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025).

Future research should aim to enhance both the rigor and generalizability of this model. Scholars are encouraged to recruit more diverse samples across different geographic and cultural settings and to adopt longitudinal or experimental designs that can unravel causal mechanisms and long-term effects of mentorship and emotional experiences. To mitigate common method bias, mixed-method approaches—combining questionnaires with interviews, observations, or multi-wave data collection—are recommended. Incorporating additional mediators and moderators, as well as refining measurement instruments (for example by revising scale items or allowing theoretically justifiable error covariances), will further strengthen model fit. Employing Bayesian SEM techniques or expanding sample size may also help address elevated RMSEA values in complex moderation models.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee (UMREC) University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XYZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HA: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LYQ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. 1. Language refinement and grammar correction in the final stages of manuscript preparation. 2. Guidance on data analysis interpretation for clarification of certain statistical procedures. The manuscript's content, structure, data collection, and analysis were primarily conducted and completed by the author(s), ensuring full intellectual ownership and academic integrity.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1569062/full#supplementary-material

References

Andreasen, J. K. (2023). School-based mentor teachers as boundary-crossers in an initial teacher education partnership. Teach. Teach. Educ. 122:103960. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103960

Bastian, A., König, J., Weyers, J., Siller, H.-S., and Kaiser, G. (2024). Effects of teaching internships on preservice teachers’ noticing in secondary mathematics education. Front. Educ. 9:1360315. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1360315

Beck, C., and Kosnik, C. (2000). Associate teachers in pre-service education: clarifying and enhancing their role. J. Educ. Teach. 26, 207–224. doi: 10.1080/713676888

Ben-Amram, M., and Davidovitch, N. (2024). Novice teachers and mentor teachers: from a traditional model to a holistic mentoring model in the postmodern era. Educ. Sci. 14:143. doi: 10.3390/educsci14020143

Burger, J. (2024). Constructivist and transmissive mentoring: effects on teacher self-efficacy, emotional management, and the role of novices’ initial beliefs. J. Teach. Educ. 75, 107–121. doi: 10.1177/00224871231185371

Cai, Z., Zhu, J., and Tian, S. (2022). Preservice teachers’ teaching internship affects professional identity: self-efficacy and learning engagement as mediators. Front. Psychol. 13:1070763. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1070763

Carmi, T., and Tamir, E. (2023). An emerging taxonomy explaining mentor-teachers’ role in student-teachers’ practicum: what they do and to what end? Teach. Teach. Educ. 128:104121. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104121

Çetin, G., and Eren, A. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ achievement goal orientations, teacher identity, and sense of personal responsibility: the moderated mediating effects of emotions about teaching. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 21, 245–283. doi: 10.1007/s10671-021-09303-y

Chen, C., and Gu, X. (2024). Understanding the development of professional identity in Chinese preservice preschool teachers: a longitudinal study. Early Child. Educ. J. 53, 1291–1301. doi: 10.1007/s10643-024-01723-8

Chen, Y., He, H., and Yang, Y. (2023). Effects of social support on professional identity of secondary vocational students major in preschool nursery teacher program: a chain mediating model of psychological adjustment and school belonging. Sustainability 15:5134. doi: 10.3390/su15065134

Chen, Z., Sun, Y., and Jia, Z. (2022). A study of student-teachers' emotional experiences and their development of professional identities. Front. Psychol. 12:810146. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.810146

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2002). Research methods in education. (5th ed.). London: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Diab, A., and Green, E. (2024). Cultivating resilience and success: support systems for novice teachers in diverse contexts. Educ. Sci. 14:711. doi: 10.3390/educsci14070711

Etikan, I., and Bala, K. (2017). Sampling and sampling methods. Biometr. Biostat. Int. J. 5:00149. doi: 10.15406/bbij.2017.05.00149

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., and Goetz, T. (2010). Achievement emotions questionnaire for teachers (AEQ-teacher)-user’s manual. Munich: University of Munich: Department of Psychology.

Galamay-Cachola, S., Aduca, C. M., and Calauagan, F. (2018). Mentoring experiences, issues, and concerns in the student-teaching program: towards a proposed mentoring program in teacher education. IAFOR J. Educ. 6, 7–24. doi: 10.22492/ije.6.3.01

Hagenauer, G., Raufelder, D., Ivanova, M., Bach, A., and Ittner, D. (2024). The quality of social relationships with students, mentor teachers and fellow student teachers and their role in the development of student teachers’ emotions in the practicum. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 39, 4067–4089. doi: 10.1007/s10212-024-00847-0

Hascher, T., and Hagenauer, G. (2016). Openness to theory and its importance for pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy, emotions, and classroom behaviour in the teaching practicum. Int. J. Educ. Res. 77, 15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2016.02.003

Hu, L. t., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Huu Nghia, T. L., and Tai, H. N. (2019). Preservice teachers’ experiences with internship-related challenges in regional schools and their career intention: implications for teacher education programs. J. Early Childhood Teach. Educ. 40, 159–176. doi: 10.1080/10901027.2018.1536902

Izadinia, M. (2015). A closer look at the role of mentor teachers in shaping preservice teachers' professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 52, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.08.003

Izadinia, M. (2016). Student teachers’ and mentor teachers’ perceptions and expectations of a mentoring relationship: do they match or clash? Prof. Dev. Educ. 42, 387–402. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.994136

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., and McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociol. Methods Res. 44, 486–507. doi: 10.1177/0049124114543236

Krejcie, R. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 30, 607–610. doi: 10.1177/001316447003000308

Kruml, S. M., and Geddes, D. (2000). Exploring the dimensions of emotional labor: the heart of Hochschild’s work. Manag. Commun. Q. 14, 8–49. doi: 10.1177/0893318900141002

Lave, J. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Lejonberg, E., and Tiplic, D. (2016). Clear mentoring: contributing to mentees’ professional self-confidence and intention to stay in their job. Mentor. Tutor. 24, 290–305. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2016.1252110

Li, H., Xu, J., Luo, Y., and Wang, C. (2024). The role of teachers’ direct and emotional mentoring in shaping undergraduates’ research aspirations: a social cognitive career theory perspective. Int. J. Mentoring Coaching Educ. 14, 123–142. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-07-2023-0064

Liu, J., and Keating, X. D. (2022). Development of the pre-service physical education teachers' teacher identity scale. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 28, 186–204. doi: 10.1177/1356336X211028832

Liu, S., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2012). Chinese teachers’ work stress and their turnover intention. Int. J. Educ. Res. 53, 160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.006

Menon, D. (2020). Influence of the sources of science teaching self-efficacy in preservice elementary teachers’ identity development. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 31, 460–481. doi: 10.1080/1046560X.2020.1718863

Moslemi, N., and Habibi, P. (2019). The relationship among Iranian EFL teachers’ professional identity, self-efficacy and critical thinking skills. How 26, 107–128. doi: 10.19183/how.26.1.483

Narayanan, V. K., Olk, P. M., and Fukami, C. V. (2010). Determinants of internship effectiveness: an exploratory model. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 9, 61–80. doi: 10.5465/amle.9.1.zqr61

Orland-Barak, L., and Wang, J. (2021). Teacher mentoring in service of preservice teachers’ learning to teach: conceptual bases, characteristics, and challenges for teacher education reform. J. Teach. Educ. 72, 86–99. doi: 10.1177/0022487119894230

Peng, W., Liu, Y., and Peng, J.-E. (2023). Feeling and acting in classroom teaching: the relationships between teachers’ emotional labor, commitment, and well-being. System 116:103093. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2023.103093

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Richardson, P. W., and Watt, H. M. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 34, 27–56. doi: 10.1080/13598660500480290

Schmidt, S. R., and Bohannon, J. N. (1988). In defense of the flashbulb-memory hypothesis: a comment on McCloskey, Wible, and Cohen. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 117, 332–335.

Shi, D., Lee, T., and Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2019). Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 79, 310–334. doi: 10.1177/0013164418783530

Sigurdardottir, I., and Mork, S. (2024). Developing preschool teacher graduate students’ professional identity with action research: connecting theory and practice. Educ. Action Res. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2024.2349536

Simon, E., and Dan, A. (2025). Mentoring processes in kindergarten student teachers’ training. Early Years. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09575146.2025.2479036

Sökmen, Y. (2021). The role of self-efficacy in the relationship between the learning environment and student engagement. Educ. Stud. 47, 19–37. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2019.1665986

Stuart, C., and Thurlow, D. (2000). Making it their own: preservice teachers' experiences, beliefs, and classroom practices. J. Teach. Educ. 51, 113–121. doi: 10.1177/002248710005100205

Su, X., Yu, D., Yu, Y., and Lian, R. (2025). Well-being and emotional labor for preschool teachers: the mediation of career commitment and the moderation of social support. PLoS One 20:e0318027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0318027

Sutton, R. E., and Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers' emotions and teaching: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 15, 327–358. doi: 10.1023/A:1026131715856

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Vol. 86). Cambridge: Harvard university press.

Wallen, N. E., and Fraenkel, J. R. (2013). Educational research: A guide to the process. New York, NY: Routledge.

Wang, H., Ruan, Q., Liu, X., Long, H., Guo, Z., Wang, Y., et al. (2025). Longitudinal development of career adaptability in pre-service teachers: the impact of internship experiences and emotion regulation strategies. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 12, 1–13. doi: 10.1057/s41599-025-04966-x

Westerman, D. A. (1991). Expert and novice teacher decision making. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 292–305. doi: 10.1177/002248719104200407

Zhang, L., Chen, Y., Zhong, W., and Jiang, L. (2025). Becoming a teacher, coexisting with emotions: a follow-up study on emotion regulation of ECE student teachers in teaching internship context in China. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s40299-025-00992-0

Zhang, Y., Hawk, S. T., Zhang, X., and Zhao, H. (2016). Chinese preservice teachers’ professional identity links with education program performance: the roles of task value belief and learning motivations. Front. Psychol. 7:573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00573

Keywords: mentor teachers, teacher emotions, professional identity, career choice, preservice teachers, preschool education

Citation: Zhang X, Abdul Rahman MNB, Abd Wahab HB and Qiu L (2025) How mentor teachers and emotions influence professional identity and career decisions of preservice preschool teachers. Front. Educ. 10:1569062. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1569062

Edited by:

Nuur Wachid Abdul Majid, Indonesia University of Education, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Hafiziani Eka Putri, Indonesia University of Education, IndonesiaChanponna Chea, National Institute of Education, Cambodia

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Abdul Rahman, Abd Wahab and Qiu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohd Nazri Bin Abdul Rahman, bW9oZG5henJpX2FyQHVtLmVkdS5teQ==

†ORCID: Haris Bin Abd Wahab, orcid.org/0000-0001-9834-3797

Xinyue Zhang

Xinyue Zhang Mohd Nazri Bin Abdul Rahman

Mohd Nazri Bin Abdul Rahman Haris Bin Abd Wahab3†

Haris Bin Abd Wahab3†