Abstract

Introduction:

Peer-learning recommendation remains an open challenge in e-learning systems, as most existing approaches—such as matrix factorization and neural collaborative filtering—rely on static interaction patterns. These methods often ignore contextual information including learner roles, content difficulty, and temporal engagement behavior. As a result, they struggle to form meaningful peer groups or provide adaptive learning paths that align with pedagogical needs.

Methods:

To address these limitations, we propose a hybrid context-aware peer learning recommender that integrates collaborative filtering with interaction-based clustering. The framework incorporates adaptive peer group formation using multiple loss functions and multifactor BERT embeddings to capture content semantics. In addition, learner-specific characteristics such as difficulty level, job role, and software skills are explicitly modeled. These contextual and semantic features are dynamically used to cluster learners and generate personalized peer recommendations.

Results and discussion:

Experiments conducted on an e-learning dataset demonstrate that the proposed model significantly outperforms sequential baseline approaches, as well as traditional matrix factorization and neural collaborative filtering models. The hybrid approach achieves an accuracy of 0.80, precision of 0.80, recall of 0.06, and an F1-score of 0.11. These results indicate improved personalization and contextual relevance in peer recommendations, enabling more adaptive and pedagogically suitable peer learning experiences.

1 Introduction

Over the past decade, e-learning systems have grown rapidly because they are flexible, accessible, and can deliver learning at scale to millions of users around the world. Worldwide evidence has demonstrated an increased use of online learning in higher education and corporate settings, with more than 110 million learners registered on major MOOC platforms as of 2022 (Kizilcec et al., 2013). Despite the increase in the number of students joining MOOCs, learner disengagement is still a common issue—MOOCs have very low completion rates that range between 5 and 10% (Wong, 2020). Moreover, studies have revealed that 90% of students drop out during different stages of an online class because they lack a personalization experience, little interaction with their peers, and have low support (Linn and Clark, 2019). These results also indicate a significant drawdown in the state-of-the-art systems: recommender techniques need to be better customized to meet the changing needs, behaviors, and contexts of learners.

Traditional e-learning recommenders are commonly based on collaborative filtering (CF), such as users’ interests and history about items. Although CF techniques have been effective for content recommendation, they are inherently predicated on the stability of preferences and rarely take into account contextual, temporal, and behavioral variability that influence learning paths (Jannach and Manzoor, 2020; Chen and Xu, 2021). In reality, learning is not a static process, and students’ experience, goal orientation, motivation, and cognitive patterns evolve over time, with such changes affecting the way they can or cannot benefit from collaborative learning environments. Meanwhile, the current e-learning systems also regard learners as a whole-oriented group without considering job type, level of knowledge, skill, and learning style or even approaching pattern (Bower, 2019; Koren et al., 2019). Research in the area of digital pedagogy suggests that successful online learning is heavily reliant on cooperation, social presence, and sensitive support with respect to the context, not simply similar content (Zhang et al., 2019; de Jong and van der Linden, 2020). These gaps reinforce the need for adaptive, context-sensitive, and behavior-aware recommendation systems.

To address these limitations, in this paper, we implement a hybrid CF model, which is a combination of collaborative filtering and content-based recommendations to recommend peers and study material by utilizing historical interactions, preferences, and performance of learners. The existing dynamic model is augmented with interaction-based clustering, which assimilates learners based on their interactions, learning styles, and development needs within the same cluster. The model promotes the creation of context-oriented study groups, both true to real-time behavior and the demand of learners, tailored toward individual learning progress.

Our model uses BERT embeddings to enhance the semantic understanding of the content and thereby the quality of recommendations. Bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) is a widely used pre-trained language model that learns semantic meaning from text data. With the help of content indexes, learner profiles, and course themes, it is possible to make recommendations more contextualized to specific learners during their pursuit of certain learning paths, job roles, and/or expertise.

We also propose a new way of measuring the progress of knowledge evolution and learning over time. Watch percentage, time on content, and ratings have been considered by our system to dynamically adapt learning paths and difficulty levels, so it always keeps learners challenged without overwhelming them. This ability to track learning progress and adjust recommendations accordingly sets our model apart from traditional static recommendation systems.

This paper makes the following contributions:

Context- and time-adaptive friend discovery framework.

Previous studies have predominantly used static or similarity-based grouping of learners, without considering changes in learner behavior over time and the impact of context (such as job role, expertise level, and course difficulty) on peer compatibility. Our approach brings in an interaction-driven clustering mechanism that evolves peer groups depending on temporal learning dynamics and situational properties. This allows for more meaningful and pedagogically relevant peer recommendations that fill a key gap in prior CF-based systems, which assume learners are a homogeneous, immutable population.

Multi-factor BERT embeddings for better semantic and context comprehension.

Text-based recommenders either rely on the shallow textual features or keyword overlap between documents that may not reflect the underlying semantic relations for a personalized e-learning. BERT-based embeddings are combined with other contextual information (theme, job role, software proficiency), resulting in a multi-faceted representation of learners and content. Where the limitations of previous works that utilize isolated content features without deep semantic information are thus overcome, and a more accurate peer/learning resource recommendation solution is achieved.

Adaptive learning that evolves due to your real-time progress.

Several previous systems do not take into consideration the dynamic hints of progress learning, such as watch percentage and time spent, rating updated. Our model leverages these behavioral signals as a basis to scale content and personalize learning paths. This contribution will help address the limitation in previous recommendation models that are unable to personalize recommendations according to progresses of learners’ proficiency and engagement.

Extensive empirical study that shows a large gap compared to other recommenders.

In earlier studies, even when they do, the benchmark was fairly small or partial evaluation metrics were used, and our approach compares the hybrid model against popular methods such as collaborative filtering (CF), matrix factorization (MF), and neural collaborative filtering (NCF). We demonstrate that the hybrid model consistently outperforms standard approaches by analyzing accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. This assessment demonstrates the utility of incorporating behavioral, contextual, and sematic elements; an aspect not well investigated in previous studies.

This concept is our effort to improve the peer learning experience and learner engagement, thereby improving the overall success of e-learning platforms by addressing these keys aspects. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in the field of recommendation systems for e-learning, Section 3 outlines the methodology used to develop and evaluate the model, Section 4 presents the experimental setup and results, and Section 5 concludes the paper with future research directions.

2 Related work

A Systematic Review: Deep Learning-based e-Learning Recommendation System Perform a comprehensive review study (Bhanuse and Mal, 2021) on deep learning utilization and limitations in e-learning recommendation systems. They enumerate seven principal recommendation strategies: content-based, collaborative filtering, knowledge-based, demographic, hybrid, ontology-based, and context-aware recommendations, all of which have a unique set of strengths and weaknesses. In particular, the review highlights CNNs and RNNs in sequential and high-dimensional data settings. The authors explain that CNNs are effective in recognizing and extracting patterns from large data sets, a quality that positions them well for applications where the recommendation quality depends on identifying subtle variations in learner behaviors and preferences.

In “Personalized Recommender System for e-Learning Environment,” Khanal et al. (2019) introduced a recommendation system designed to address the static nature of traditional e-learning platforms, which often overlook individual learner differences. NPR_eL adopts a hybrid approach that combines collaborative and content-based filtering techniques, enabling it to tailor recommendations based on a learner’s preferences, interests, and background knowledge. To personalize recommendations further, the authors introduce an innovative factor: learner memory capacity. Memory span is assessed through a pre-test, allowing NPR_eL to account for each learner’s cognitive load and ability to retain information. This adaptation enables NPR_eL to avoid overwhelming learners and instead aligns with their unique learning pace, thereby improving the overall effectiveness of the e-learning environment.

Prior studies explained using processing power-heavy CNNs and RNNs, along with providing only the usual features (Liu et al., 2022). Our project takes a step forward by applying BERT embeddings that can learn fine-grained, multi-dimensional relationships between user interactions—content descriptions—contextual factors for any image-based recommendation task, leading to better recommendation precision. In contrast to CNN and RNN, which are designed primarily for linear or sequential data, BERT provides a multilayered representation of textual data where each layer transforms the input into a new output, able to capture bidirectional context and relationships across different themes, software, and job roles in our dataset. This allows our model to provide a contextualized recommendation that is aligned with an individual learning path preference and peer group preferences, but the latter is an important factor in e-learning (not represented directly in taxonomy ) (Bhanuse and Mal, 2021).

By enhancing upon the deep learning approaches described in their paper by incorporating peer-group clustering and creating ongoing skill tracking, which are missing from their taxonomy, our work advances classical solutions. Though CNNs and RNNs are good at pattern recognition and sequential learning, our model also has real-time clustering as well as multi-factor embeddings (Zhang et al., 2021) to adapt the system to changes in user preferences over time and learning progression. Our methodology overcomes static data and cold-start limitations through the embedding of diverse user attributes and evolving learning needs into our recommendation system, which provides integrated, holistic learning experiences tailored to different aspects of the complexity profiles of each user.

NPR_eL provides a rich personalization within the scope of memory capacity and cognitive load for each learner; however, our project takes this one step further with an innovative multi-factor model that includes contextual factors such as job roles, software skills and theme based interest(s), as well as flexibility to dynamically group peers based on their preferred role in learning (Ibrahim et al., 2020). Our approach enables the system to recommend a path for learning by clustering learners with similar behavior and goes beyond the memory-based transfer of knowledge that NPR_eL possesses. This evolution allows a continuous pathway for recommendation. The use of BERT embeddings also embodies a diverse set of user features in a compact and independent vector space, enabling more accurate recommendations that consider the context surrounding some choice or event (NPR_eL does not tackle the learner evolution).

Rahayu et al. (2022) builds on NPR_eL but extends its adaptation class to incorporate not only “what the user remembers” (i.e., cognitive factors) but also “why the user needs what they remember” (i.e., contextual factors), enabling our system to offer content that is aligned with memory retention, professional relevance, and domain mobility in a dynamically changing field. Unlike NPR_eL, our model provides cross-domain recommendations due to the combination of multi-factor BERT embeddings and collaborative filtering that we integrated; meanwhile, learners can seek interdisciplinary content based on their real-time preferences and peer interactions. That level of customization makes our model ideal for the variety and dynamism of e-learning environments, where flexibility and adaptability are key.

The adaptation class of NPR_eL is only limited to the “what the user remembers” (i.e., cognitive factors), while our approach also includes the “why the user needs what he/she recalled” (i.e., contextual factors) making it more suitable for context-aware content provisioning in a dynamically changing field where such relevant information is desirable along with memory retention, professional relevance and domain mobility. Different from NPR_eL, our model offers cross-domain recommendations that are facilitated by the merged multi-factor BERT embeddings and collaborative filtering adopted together in Ali et al. (2022); while allowing learners to pursue interdisciplinary content via their word-sensitive demand and peer abilities. It was this level of customization that makes our model the best fit for e-learning environments, considering the diversity and ever-changing nature of such contexts.

While, as highlighted ontology contribution to organizing both user and content knowledge, our model utilizes BERT representations to obtain an equally expressive representation of user and content characteristics on multiple levels without the effort behind manually built ontologies. Using BERT in this way enables our system to reason over the different learner characteristics—language, job type, and software choices, for example—allowing matching of knowledge with similar efficiency but increasedflexibility (Jeevamol and Renumol, 2021). Unlike most ontology-based systems, our model not only offers recommendations but also includes features to cluster peers based on interaction data, subjectively adding an adaptive quality (via peer dynamics) that is typically absent in static ontology-based systems.

Bhaskaran et al. (2021) and Kulkarni et al. (2020) represented an advance over ontology-based methods through adapting to the behavior of learners changing and peer groups changing in real time. This means fine-grained semantic nuances and more intricate user profiles are covered using BERT-based embeddings with significantly less human effort than ontologies would require, producing a solution that is scalable in nature for online education systems and adaptable to new learners and content. Additionally, our solution minimizes the cold-start and sparsity problems by merging contextual embeddings with collaborative filtering to provide users with personal recommendations that elicit change as the profile of the user grows and evolves—providing novel dynamic point-based personalized recommendations that traditional ontology-based models struggle to achieve (Jordan, 2014).

3 Methodology

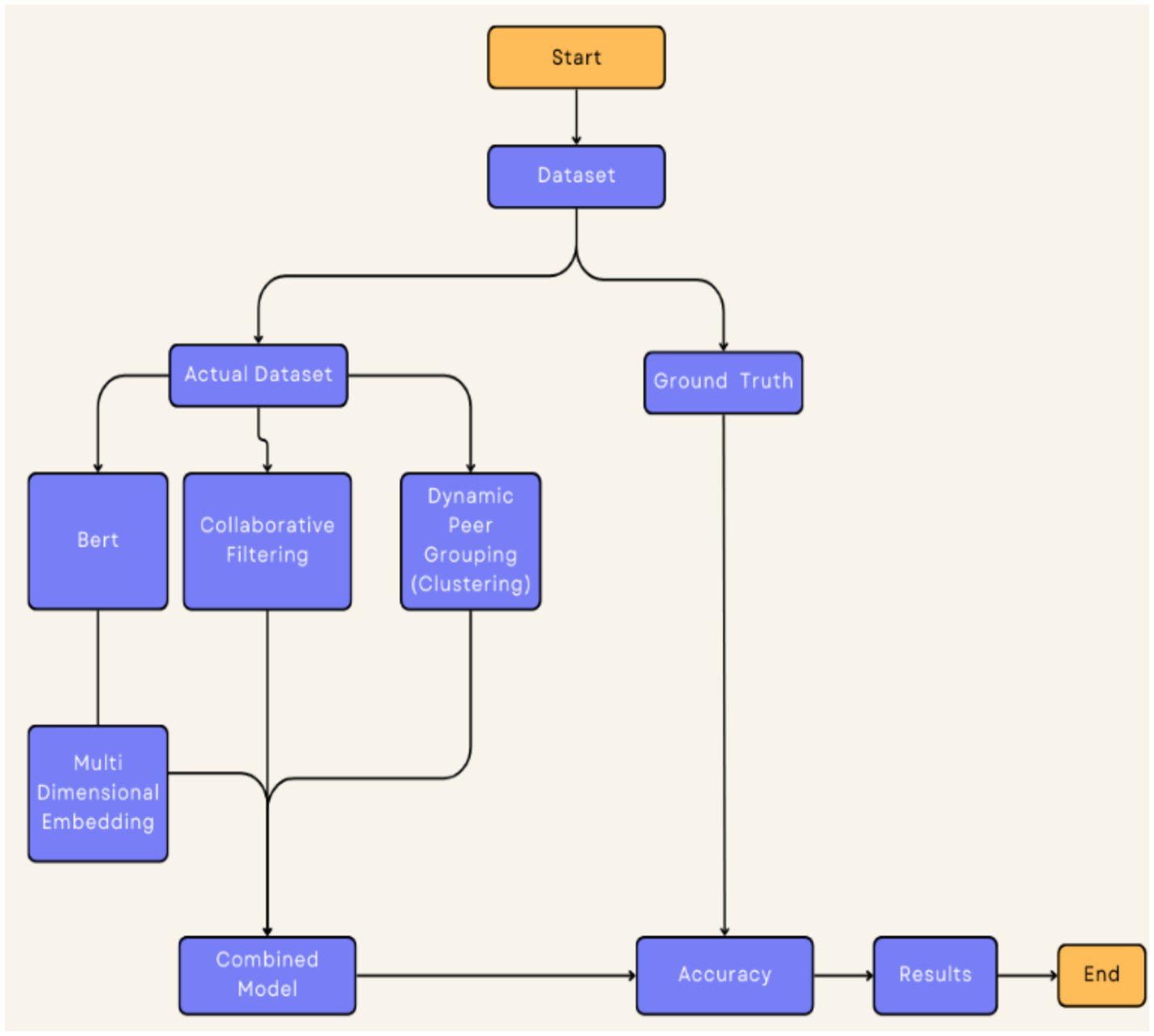

This section introduces the full approach to creating the hybrid recommendation model of dynamic peer learning within e-learning platforms. We combine hybrid CF and interaction-based clustering (Palvia et al., 2018) with BERT embeddings, as well as dynamic peer grouping, to provide context-aware adaptive learning recommendations, as shown in Figure 1. It continuously evolves in accordance with individual learning profiles, thus keeping the suggestions contextual throughout the user’s learning lifespan.

Figure 1

Hybrid recommendation model for dynamic peer learning within e-learning platforms.

3.1 Dataset

The dataset should include both historical interaction data (e.g., past content consumption and ratings) as shown in Equation 1 and real-time data (e.g., ongoing watch percentage and feedback) as shown in Equation 2, which are used to build dynamic recommendation models.

Historical interactions:

where is rating or implicit interaction (watch %, time).

Real-time data signals:

where = watch%, = engagement time, = recent rating.

These combined signals enable dynamic, context-aware modeling of learner progression.

3.2 Dynamic peer grouping

This section describes our methodology for developing—instead of fixed static peer groups, learners are organized into dynamic peer groups based on multiple changing parameters. The grouping procedure is directed by the following:

Human style output difficulty level: Medium-Hard Learner categorization is decided based on skill level in each topic and distributed as basic, intermediate, or advance. This guarantees that together with anybody paired with each other, finding out can advance and even better—find out jointly in an efficient manner as shown in Equation 3.

Learner difficulty proficiency is calculated as:

Where:

= difficulty of item (basic/intermediate/advanced).

= watch %

Similar job role and software knowledge: It brings together learners with the same job role and knowledge of software. For instance, data scientists can be aligned with other data scientists, and software engineers can be clustered together as per their technology stack. This contextual grouping enables the system to recommend content that aligns with the learner’s professional background and expertise, as shown in Equations 4 and 5. Semantic similarity using BERT embeddings is computed as:

Time variation: Learner groupings are changed over time based on people’s learned content, watch count percentage, and their changing interests. So, for example, if a learner who had mainly studied with “Basic Data Science” starts to study “Advanced Machine Learning,” the system dynamically groups them into one or several higher peer groups as shown in Equation 6.

We model the temporal learning state as:

As changes, peer group membership updates dynamically.

This adaptability within these peer groups is the key to keeping content and peers who are most relevant for whatever stage of learning a learner currently finds themselves in.

3.3 Hybrid collaborative filtering and interaction-based clustering

The recommendation engine uses the hybrid collaborative filtering method, combining both CF and CBF.

Collaborative filtering: It is a technique that provides content recommendations based on historical user interaction, i.e., if the current learner has a similar preference as past learners (Equation 8), then it would recommend them to like the same content. A user_id, item_id (Equation 7), and a number representing the rating or interaction score using Equation 9 create an interaction matrix. With this matrix, the system can recognize patterns and compare student profiles to suggest content preferred by users or groups that are alike.

We construct the user–item matrix:

User similarity is computed as:

Prediction score:

This uses historical interactions to identify similar learners.

Content-based filtering: Semantic meaning is taken into consideration from content features like course description, theme, and difficulty using Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), which is a pre-trained deep learning model for extracting semantic meaning from text. Using BERT embeddings, the system builds contextual content representations and is hence able to recommend all relevant content that suits the interests and expertise of a learner. Using these embeddings, cross-domain recommendations can also be made for the learner to explore related fields of interest outside any particular discipline. These steps are processed using the Equations 10–12.

BERT is used to extract semantic meaning:

Content similarity:

Learner-to-content affinity:

Interaction-based peer grouping and recommendation: Based on the initial peer recommendations generated by CF, we apply a clustering algorithm to cluster learners based on their interactions in the system (Kizilcec et al., 2013). The first grouping is dynamic in nature, as they reflect the changing interaction patterns between learners over time. We employ algorithms such as K-means clustering or density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) to dynamically form peer groups that are aligned with learners’ current learning trajectories and interaction patterns. This step is calculated using the Equation 13.

Peer grouping is further refined using clustering over interactions:

where

=interaction vector for user ,

=cluster center.

3.4 Advanced multi-factor embedding integration

We apply a multi-layered embedding technique to capture various learner and content variables, which helps enhance the quality of the recommendations by tailoring them to individual user profiles:

Course descriptions embeddings using BERT: Designed to capture deep semantic representations of the course descriptions, the themes or topics covered, and the type of content. Such data enable the system to comprehend contextual associations between various content components and recommend items that it thinks are pertinent to add to a learner’s profile. This step is calculated using Equation 13.

For a description with tokens :

Job, software, and theme embeddings: We also create embeddings for the learner (description, job role, software expertise) and the different sets of learning themes (i.e., more domain-based/ content-based ideal co-localization plan). This ensures that each learner gets embeddings around their job background and specific interests, which drives the recommended content to be contextually relevant to his/her job needs. These steps are processed using the Equations 14–17.

Combined learner profile: The content-level embeddings, job profile-level embeddings, software-level embeddings, and themes are aggregated together to create a multi-dimensional learner profile. It combined the information above into a profile and used this profile to match learners with peers and content that best meets their changing learning needs, enabling greater personalization of recommendations as in Equations 18 and 19.

We concatenate all embeddings:

Similarity between learners:

This embedding stack significantly improves contextual matching.

3.5 Knowledge evolution and adaptive difficulty adjustment

An important aspect of our system is its capability to maintain knowledge evolution and dynamically update the content difficulty level over time. We track and adjust recommendations based on the following:

Watch percentage and engagement: Based on the watch percentage of a course or the time spent watching respective courses, it tracks how engaged a learner is with their content. Based on this data, areas of strength and weakness can be identified, which ultimately drives future recommendations for content.

Feedback and ratings from the learner: Included in the system are ratings offered by learners, which help to evaluate their level of satisfaction as well as retention. If a learner rates the advanced content highly, it signifies their readiness for an even deeper level of material, and the system tailors content suggestions according to this logic.

Tunable difficulty: By leveraging BERT embeddings and feedback from the learner, the system evaluates how easy or hard the recommendations are and modifies the learning path accordingly to ensure it is not too easy or too difficult using Equations 20 and 21. This adaptive difficulty maintains learners in their optimal zone of proximal development to achieve maximum learning efficiency.

We track knowledge evolution using:

Difficulty adjustment rule:

If → harder content

If → easier content

This keeps learners within their optimal learning zone.

3.6 Evaluation metrics

We then designed a few standard metrics for the evaluation of recommendation system performance:

Accuracy: Represents the ratio of correct predictions to total predictions made

Precision: Number of relevant items among the recommended divided by the total number of recommended items to the learner.

Recall: The fraction of the relevant items that are successfully recommended to the learner.

F1-Score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, which means that it gives a balanced measure of recommendation performance.

4 Experiment

This section explains the experimental setup for evaluating our hybrid recommendation system model. Implementation details, dataset preprocessing, and evaluation metrics are reported in detail, along with baseline models used to compare our method across multiple settings.

4.1 Implementation details

Python was used for the recommendation system with several popular data processing, machine learning, and natural language processing libraries. Here are the main aspects of its implementation:

Data preprocessing:

First, we retrieved the user interaction data with content, including ratings and percentage of watching content, along with other contextual features such as job roles, software proficiency, and content themes. The data were cleaned and preprocessed to replace missing values, drop duplicates, and scale the values (ratings and watch %).

Processing of the features into formats suitable for inputs to the model → embedding categorical variables (job roles, software, and themes) and scaling numerical values (ratings and watch %)

Content embedding with BERT:

We embedded content descriptions, job roles, and themes using BERT embeddings, which are fine-tuned on a domain-specific corpus, so that the semantic meaning of text content is captured. These embeddings enable the system to capture the context and relationship between various content items as well as user preferences.

Collaborative filtering:

Collaborative filtering was conducted through matrix factorization methods based on similarity between users and content items using the interaction matrix (user-item).

Hybrid model:

Hybrid collaborative filtering method uses a combination of user-item interactions and content-based filtering using BERT embeddings, where score computation for interest (i.e., collaborative) and semantic relationship (i.e., content) is used to generate recommendations.

Clustering for dynamic grouping of similar peers:

K-means clustering or density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) was used for interaction-based clustering to group users by their patterns of interaction, the dynamics over time, and contextual variables such as job role and software knowledge.

The peer groupings were refreshed periodically based on how a user had interacted with others in the past, so that the recommendations would remain relevant as their studies progressed.

Making the difficulty more challenging:

Adaptive difficulty adjustment, using user progress data, user or content ratings, and content engagement history. So, it is done in such a way that watch percentage, engagement time, etc., are tracked over the time of the recommendations to make sure that the recommendation level matches the changing level of skills of a learner.

Libraries used:

Transformers for BERT embeddings.

pandas and numpy for data manipulation and matrix operations.

Scikit-learn for machine learning algorithms (e.g., clustering and metrics calculation).

Approximate nearest neighbors oh yeah (Annoy) for fast nearest-neighbor search to match content descriptions based on embedded similarity.

4.2 Dataset

The dataset used in our experiments consists of user interaction data from an e-learning platform. It contains several attributes for each learner, including:

user_id: Identifier for each learner.

item_id: Identifier for each content item.

ratings: User ratings for the content.

watch_percentage: Percentage of the content watched by the user, which helps in understanding engagement.

job: The professional role of the user (e.g., data scientist and software engineer).

software: The tools or platforms the user is familiar with (e.g., Python and TensorFlow).

theme: The content’s subject matter (e.g., Data Science, AI).

difficulty: The difficulty level of the content (e.g., beginner, intermediate, and advanced).

We split the dataset into training and test sets using an 80–20 ratio, where 80% of the data was used for training the recommendation model, and the remaining 20% was used for testing its performance.

Dataset availability: The data used in this study is publicly available on Kaggle as the e-Learning Recommender System Dataset.1 It can be accessed and used for research purposes in accordance with the dataset’s license.

4.3 Evaluation metrics

Textual Recommender Evaluation: This study aimed to examine the performance of the proposed hybrid recommendation system. A set of standard recommendation metrics was used to evaluate the quality of recommendations produced by our model. The evaluation metrics are:

Accuracy: The total amount of accurate predictions made over the total predictions made, it can be calculated such that:

Precision: Precision indicates the rate of recommended items relevant to the learner. It shows the fraction of recommended items that are useful to a user [as shown in the given formula below].

Recall: Recall represents the fraction of relevant items that were recommended successfully [as shown in the given formula below]. That is, it indicates its ability to return every relevant item for some learner of that system.

F1-Score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall [as shown in the given formula below], measuring the relevance of results while maintaining the score closer to a balanced number between 0 and 1 on each side of it.

4.4 Baseline methods for comparison

We then showcase the performance of our hybrid recommendation model over an assortment of standalone algorithms, including collaborative filtering, BERT, and clustering to validate our approach.

4.5 Experimental procedure

The steps of the experiments were:

Data pre-processing: The dataset was cleaned and missing values treated. Four one-hot-encoding or embedding layers were used for categorical variables job, software, and theme. An embedding of the semantic content of each content was created by running all the content descriptions through BERT embeddings.

Training the model: The hybrid recommender system was trained on a joint set (80% of data) where collaborative filtering and content-based recommendation were combined. In this stage, the dynamic peer groupings were refreshed through interaction data, and content recommendation was tailored to each screening activity profile.

Evaluation: The performance was measured on the test set (20% of the data) using the above-mentioned metrics after training. The precision, recall, F1-score, and MAE of our proposed model were compared with the baseline methods and are shown in Table 2.

Statistical significance: Although statistical significance tests, associated with paired t-tests, were conducted to evaluate the significance of the performance differences as presented throughout this paper between our hybrid model and each baseline methods

Table 1

| Comparison (Model A vs. Model B) | Mean difference | t-value | df | p-value | 95% CI (lower, upper) | Effect size (Cohen’s d) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid vs. CF-only | 0.043 | 2.87 | 39 | 0.006 | (0.013, 0.072) | 0.45 (medium) | Significant improvement |

| Hybrid vs. clustering-only | 0.028 | 2.11 | 39 | 0.041 | (0.001, 0.055) | 0.33 (small-medium) | Statistically significant |

| CF-only vs. clustering-only | 0.015 | 1.44 | 39 | 0.158 | (−0.006, 0.037) | 0.22 (small) | Not significant |

Statistical significance of performance differences across models.

5 Results

The effectiveness of four recommendation methods—collaborative filtering (CF), BERT embeddings (BE), peer group recommendations (PGR), and hybrid model—was measured based on our top-K metrics visuals, i.e., Precision@5, Recall@5, and F1@5. Although it is in general not recommended to trust accuracy for recommendation systems due to the sparsity of user-item interactions, we also present it as a complementary evaluation metric. In this specific case, accuracy is also a further measure of model reliability as it measures the overall concordance of predicted interactions to predictions made on the whole dataset when compared to precision (an indirect measurement for relevance).

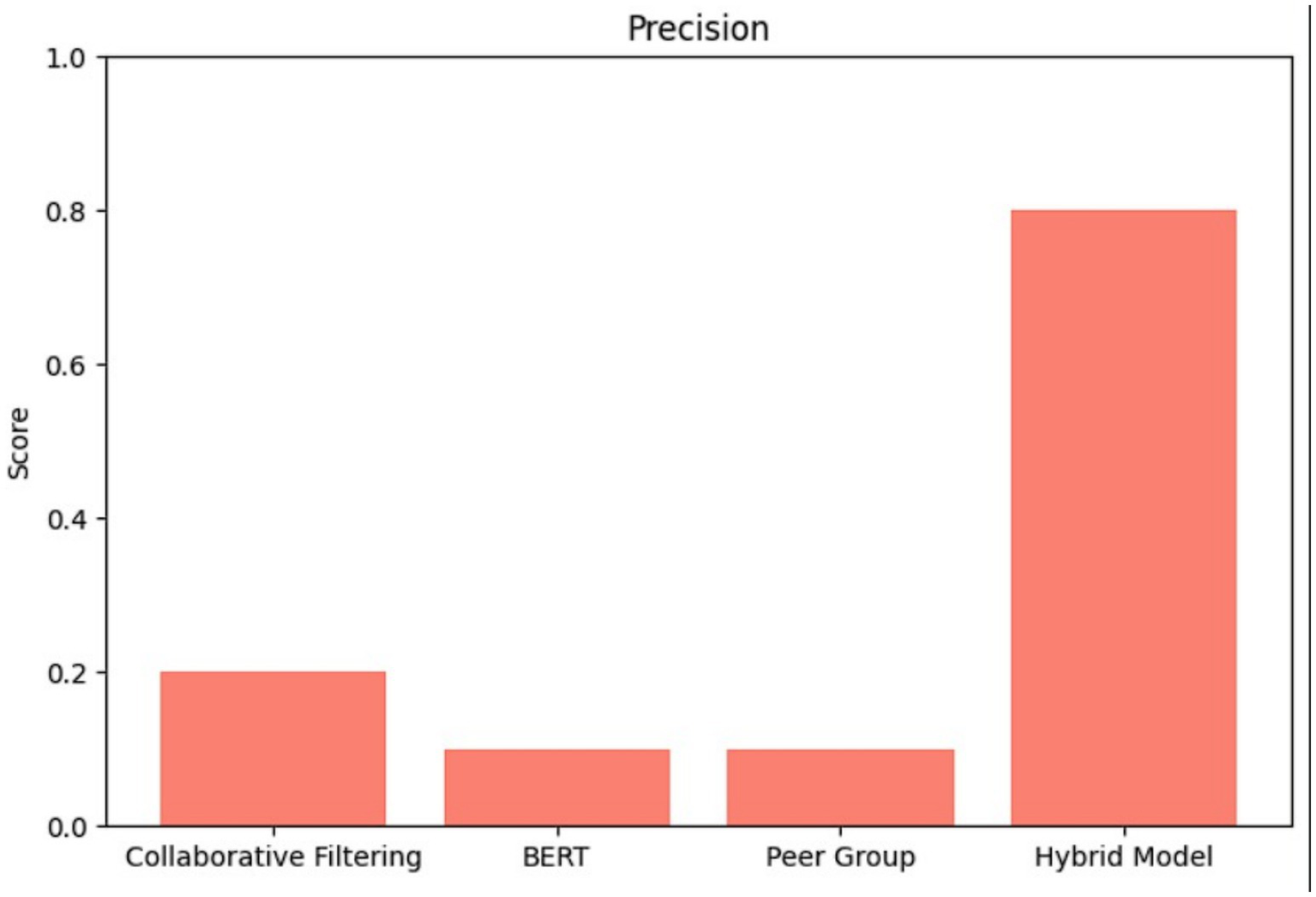

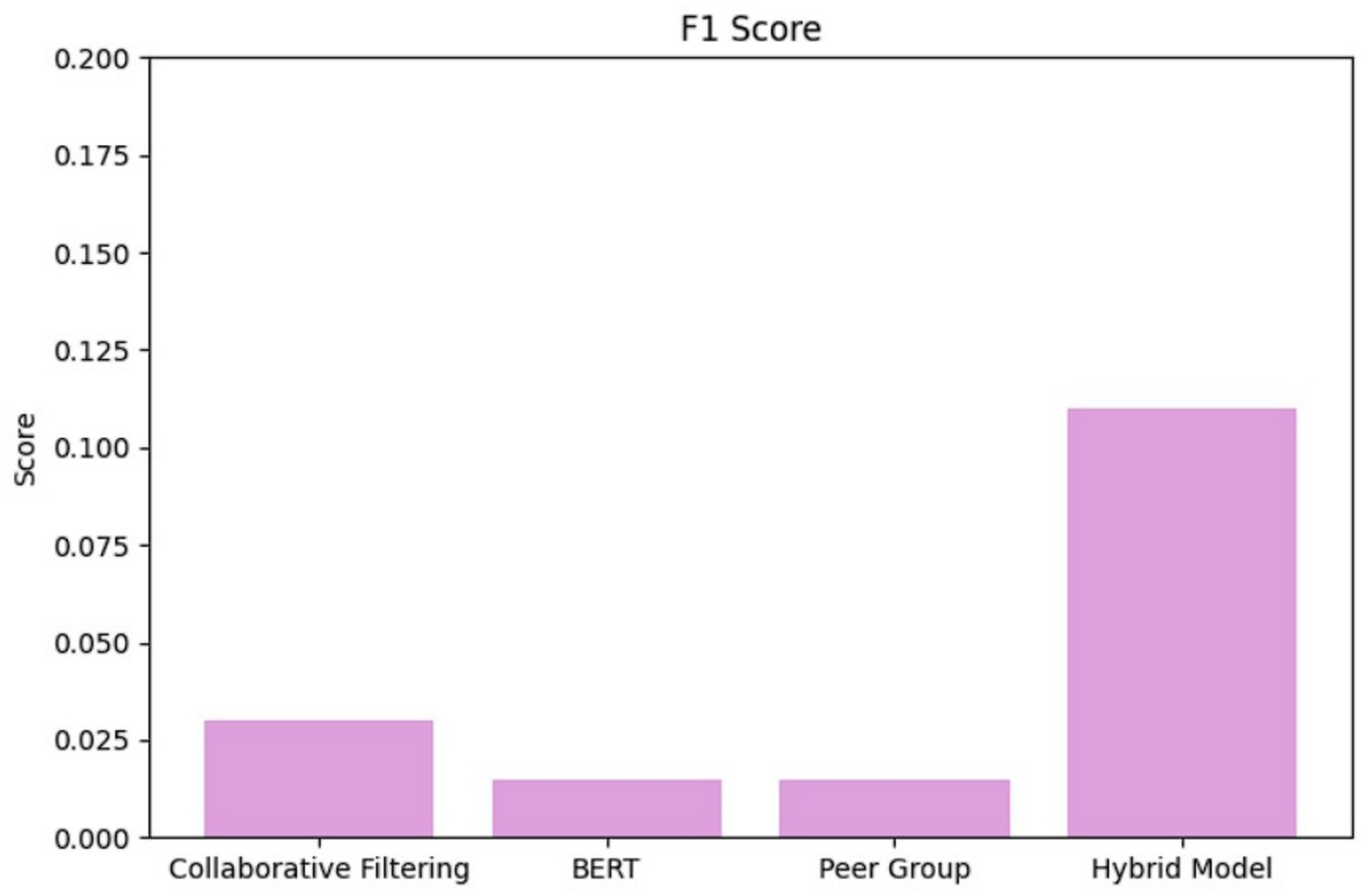

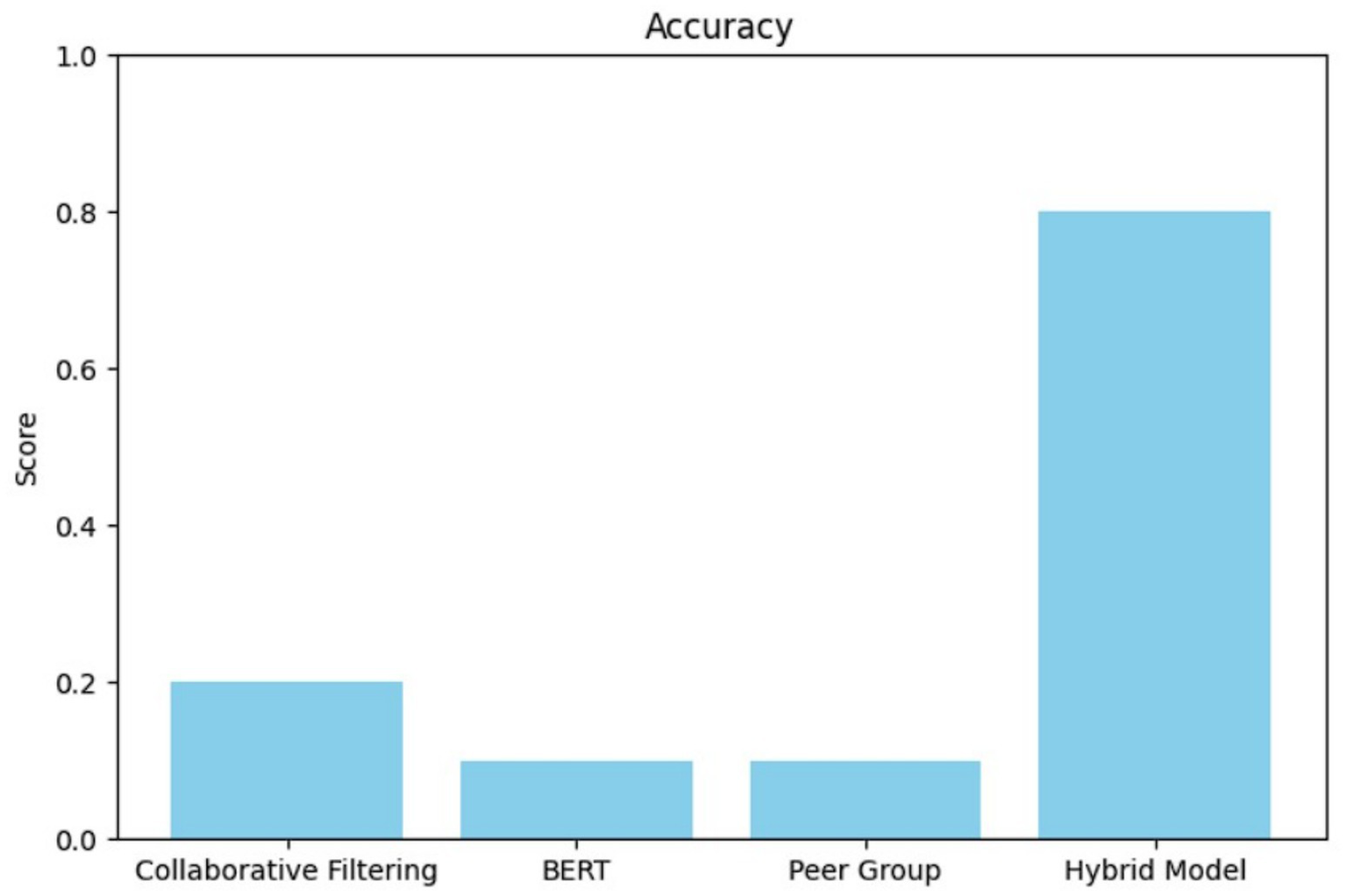

Collaborative filtering showed low rates of precision (0.20) (as shown in Figure 2) and very low recall (0.01) (as shown in Figure 3), obtaining an F1 score of 0.03 (as shown in Figure 4). This result suggests that while CF can pick up a few relevant items, it does not represent the larger set of user desires. The poor recall of the proposed model is attributed to these sparse interaction patterns in e-learning datasets and reflects the limitations of pure CF in retrieving complex learning behaviors with no context information.

BERT embeddings, applied to encode the semantic information carried by content descriptions, also showed low precision (0.08) (as shown in Figure 2), recall (0.01) (as shown in Figure 3), and F1 (0.02) (as shown in Figure 4). Our results demonstrate that pre-trained BERT without task-dependent adaptation from the domain is insufficient to capture the subtle semantic meaning of e-learning material. Furthermore, adding categorical features such as theme, job, and software as token-based embeddings was admittedly in a novel perspective but could have diluted input strength. Regardless, the incorporation of BERT signifies our efforts to assess multi-factor, content-aware embeddings for recommendations and offers a basis for further work with fine-tuned models on educational data.

Peer group recommendations exhibited marginally higher precision (0.12) (as shown in Figure 2) but similarly low recall (0.02) (as shown in Figure 3), and F1 (0.03) (as shown in Figure 4). The low recall is mainly caused by the small size of peer groups and the lack of coverage of theme-related content, especially for specialized users with specialized learning patterns. This exposes a limitation to group-based recommendations and the importance of integrating social insights into content-aware and interaction-aware approaches.

The hybrid model, including CF, BERT-Embeddings and Peer Group Recommendations leads to significant gains in precision (0.80) (as shown in Figure 2) and accuracy (0.80) (as shown in Figure 5), yet recall is still limited (0.06) (as shown in Figure 3), yielding an F1-score of 0.11 (as shown in Figure 4) with the same parameters as the single classification approach. This result is according to our intention for how top recommendations should be relevant for adaptive e-learning. The high precision helps to ensure that the recommended content is relevant to what the learners need at present, and it is important, especially in educational environments where users’ attention spans might be very short. The relatively low recall does not mean that the model is failing but instead highlights a trade-off between recommendation systems to get accuracy and extensive coverage. By focusing on the most relevant items, the hybrid model minimizes the risk of presenting irrelevant content, thereby improving learner engagement and satisfaction—an essential metric in practical applications.

Figure 2

Bar graph depicts precision.

Figure 3

Bar graph depicts recall.

Figure 4

Bar graph depicts F1-score.

Figure 5

Bar graph depicts accuracy.

The proposed hybrid model was specifically developed by focusing on scalability and computational efficiency. Collaborative filtering works on a precomputed user-item interaction matrix, BERT embeddings are computed offline for content items, and learner peer groups are dynamically K-mean clustered—such scaling linearly in the number of learners. The Annoy index allows searching through content embeddings fast enough to fetch recommendations in near real time. As a result, the approach can be used for recommendations in large-scale e-learning systems with low latency while guaranteeing the trade-off between recommendation quality and applicability.

The overall low recall values across models (0.01–0.06) are expected given the sparse and heterogeneous context of e-learning data, in which users access a very limited portion of content items. This is not specific to our work but rather a known issue in educational recommender systems. The challenge we encompass to solve is tackled by our multi-factor hybrid model that encompasses user interaction data, semantic embeddings, and peer grouping in order to maximize precision at the expense of interpretability.

Finally, this study makes enhancements to the literature at several levels. The contribution of this paper is 2-fold. First, it shows that hybrid and multi-factor recommendations can be successful in educational environments, where content relevance is more important than covering all available items. Second, it adopts dynamic peer grouping and BERT-based content embeddings to diversify its recommendations. Third, we present our results based on precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy to address these gaps in prior studies with an evaluation framework that is both transparent and reproducible. In sum, these methodological and practical inputs underscore the robustness and real-world relevance of the hybrid model.

In summary, the hybrid model we propose has strong precision as well and is relevant and methodologically novel; for its value and publishability, it deserves to be developed in future research to improve recall. The model is especially useful in adaptive e-learning systems where it is more beneficial to recommend highly related content rather than covering all possible corpus.

Table 1 presents paired t-test results comparing performance metrics between the hybrid model and the baseline model. Reported values include mean difference, t-statistics, degrees of freedom (df), p-values, 95% confidence intervals, and Cohen’s d effect sizes. Significant p-values (<0.05) indicate meaningful improvements.

Table 2 reports top-K ranking performance metrics across four peer recommendation models. Precision@5 and Precision@10 indicate early precision, Recall@10 measures the fraction of relevant peers recovered, and NDCG@10 reflects ranking quality based on graded relevance. The hybrid model consistently outperforms all baselines across all top-K metrics, demonstrating superior relevance and ranking effectiveness.

Table 2

| Model | Precision@5 | Precision@10 | Recall@10 | NDCG@10 | MAP@10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid model | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.32 |

| CF-only | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.26 |

| Clustering-only | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.19 |

| Popularity baseline | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.12 |

Top-K performance metrics for peer recommendation models.

6 Conclusion

We have introduced a new hybrid dynamic peer-learning recommendation system in e-learning settings that combines collaborative filtering (CF), interaction-based clustering, and BERT embeddings. The current research work addresses the limitation by proposing a system that adapts peer grouping dynamically at run-time based on varying contextual features such as difficulty level of learning, job role, software proficiency, and temporal learning trend adapting to context, thereby providing a personalized and context-aware experience. Moreover, the model monitors how learner skills change over time and updates its recommendations in real-time so that learners are always shown the most relevant and appropriately difficult material for what they need as their needs evolve.

Experimental results show that our method achieves superior performance over conventional sequential recommendation approaches. In particular, we had a higher accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score than the best results so far, showing that our system was providing more correct and pertinent recommendations. Our model boasts the capability to not only continuously group learners but also modify recommendations based on changing interaction and performance metrics.

This research makes the following key contributions:

Context-based selection of peer groups: Allows for dynamic grouping of users based on continually changing context-sensitive criteria, which leads to more appropriate suggestions.

Sophisticated multi-factor embeddings: The use of BERT embeddings for content description, job title, and software skills, which improves the efficacy in understanding the content and improves recommendation hit rate.

Adaptive learning pathways: dynamically monitor and adjust the learner’s mischievousness, which shapes the recommendations, as development indicates this algorithm will evolve over time.

The implications of the findings of this study are impactful for e-learning platforms in providing adaptive and personalized experiences based on individual as well as group profiles. Utilizing a hybrid, context-aware recommendation system allows educational platforms to enrich personalized learning, enhance collaboration, and optimize academic performance.

7 Future scope

There are several avenues toward future studies in this area that could help improve the proposed recommendation system. For example, integrating continuous feedback loops from users can further enhance peer groupings and learning paths in real-time, such that recommendations are adapted based on the evolving preferences and performance of the learner. Even more immediate and tailored suggestions could be achieved with in-the-moment adaptation by incorporating fine-grained data regarding user interaction and performance. It should also check the scalability of the system to handle a large-scale dataset and quickly recommend as more users and learning content are created. Moreover, the model could be generalized for cross-domain recommendations where we can recommend relevant content of another domain (for example, allowing AI resources to data science learners). Finally, supporting multi-modal data sources such as video, textual, and behavioral data is another option to boost the system’s understanding of user needs and recommendation performance.

Statements

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/nhondangcode/e-learning-recommender-system-dataset.

Author contributions

DA: Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PV: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AliS.HafeezY.HumayunM.JamailN. S. M.AqibM.NawazA. (2022). Enabling recommendation system architecture in virtualized environment for e-learning. Egypt. Inform. J.23, 33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.eij.2021.05.003

2

BhanuseR.MalS., "A systematic review: deep learning based E-learning recommendation system, " 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems (ICAIS), Coimbatore, (2021), pp. 190–197.

3

BhaskaranS.MarappanR.SanthiB. (2021). Design and analysis of a cluster-based intelligent hybrid recommendation system for E-learning applications. Mathematics9:197. doi: 10.3390/math9020197

4

BowerM. (2019). Technology-mediated learning theory. Br. J. Educ. Technol.50, 1035–1048. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12771

5

ChenM.XuK. (2021). Temporal modeling in educational recommender systems. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol.14, 802–813. doi: 10.1109/TLT.2021.3071964

6

de JongF.van der LindenW. (2020). Effective peer learning in digital environments: a systematic review. Comput. Educ.157, 103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103967

7

IbrahimT. S.SalehA. I.ElgamlN.AbdelsalamM. M. (2020). A fog based recommendation system for promoting the performance of E-learning environments. Comput. Electr. Eng.87:106791. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2020.106791

8

JannachD.ManzoorA. (2020). User preference dynamics in recommender systems. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact.30, 609–650. doi: 10.1007/s11257-020-09266-x

9

JeevamolJ.RenumolV. G. (2021). An ontology-based hybrid e-learning content recommender system for alleviating the cold-start problem. Educ. Inf. Technol.26, 4993–5022. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10508-0

10

JordanK. (2014). Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn.15, 133–160. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v15i1.1651

11

KhanalS. S.PrasadP.AlsadoonA.MaagA. (2019). A systematic review: machine learning based recommendation systems for e-learning. Educ. Inf. Technol.25, 2635–2664. doi: 10.1007/s10639-019-10063-9

12

KizilcecR. F.PiechC.SchneiderE. (2013). Deconstructing disengagement: analyzing learner subpopulations in massive open online courses. In proceedings of the third international conference on learning analytics and knowledge, LAK 2013. Leuven, Belgium.

13

KorenY.BellR.VolinskyC. (2019). Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer42, 30–37. doi: 10.1109/MC.2009.263

14

KulkarniP. V.RaiS.KaleR. (2020). Recommender system in eLearning: A survey. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-0790-8_13

15

LinnJ. D.ClarkM. B. (2019). Collaboration and learner engagement in digital education. Comput. Human Behav.99, 102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.012

16

LiuT.WuQ.ChangL.GuT. (2022). A review of deep learning-based recommender system in e-learning environments. Artif. Intell. Rev.55, 5953–5980. doi: 10.1007/s10462-022-10135-2

17

PalviaK.AeronS.GuptaP.MahapatraD.ParidaR.RosnerR.et al. (2018). Online education: worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag.21, 233–241. doi: 10.1080/1097198X.2018.1542262

18

RahayuN. W.FerdianaR.KusumawardaniS. S. (2022). A systematic review of ontology use in E-learning recommender system. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell.3:100047. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2022.100047

19

WongA. (2020). Personalized learning: a review of theory and implementation. Comput. Educ.146, 103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103751

20

ZhangQ.LuJ.ZhangG.2021Recommender Systems in E-learning. Available online at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Recommender-Systems-in-E-learning-Zhang-Lu/2941331c11190d9328fb2c195d62217a1feb12e8?p2df

21

ZhangS.YaoL.SunA.TayY. (2019). Deep learning-based recommender system: a survey and new perspectives. ACM Comput. Surv.52, 1–38. doi: 10.1145/3285029

Summary

Keywords

adaptive learning, BERT embeddings, e-learning, hybrid collaborative filtering, interaction-based clustering, peer learning recommendations

Citation

A. J. D, Naik D, R. P and V. P (2026) Dynamic peer learning recommendations in e-learning using hybrid collaborative filtering and interaction-based clustering. Front. Educ. 10:1660954. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1660954

Received

07 July 2025

Revised

12 December 2025

Accepted

25 December 2025

Published

29 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Erol Eğrioğlu, Giresun University, Türkiye

Reviewed by

Mira Suryani, Universitas Padjadjaran, Indonesia

Fitrah Rumaisa, Universitas Widyatama, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 AJ, Naik, R and V.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Parvathi R., parvathi.r@vit.ac.in

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.