Abstract

Introduction:

Traditional approaches to teaching physics often struggle to engage students and to convey abstract concepts such as gas laws in a meaningful way. This challenge is particularly evident for learners accustomed to interactive and technology-mediated environments. Recent advances in embodied cognition and active learning suggest that multi-sensory interaction may enhance engagement and conceptual understanding. Visuo-haptic simulators represent a promising approach by combining visual and tactile feedback to support experiential learning.

Methods:

This study developed a visuo-haptic simulator designed to support the exploration of Boyle's Law through interactive manipulation of pressure and volume variables. The simulator provided real-time visual feedback and proportional haptic resistance to represent changes in gas behavior. Thirty-nine undergraduate engineering students interacted with the simulator in controlled laboratory sessions. A mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate students' perceptions, combining the End-User Computing Satisfaction (EUCS) survey with semi-structured interviews.

Results:

Survey results indicated high levels of satisfaction in the dimensions of accuracy, ease of use, and timeliness, reflecting students' confidence in the simulator's responsiveness and reliability. Qualitative findings revealed strong engagement and motivation, with participants reporting that tactile feedback helped them intuitively understand the inverse relationship between pressure and volume. Some usability challenges related to interface layout were also identified.

Discussion:

The findings suggest that visuo-haptic simulators can promote active engagement and support embodied understanding of abstract physics concepts by linking theoretical relationships to sensory experience. Students perceived the simulator as a valuable complement to traditional instruction and expressed interest in its application to other scientific topics. While learning outcomes were not directly measured, the results highlight the potential of visuo-haptic tools to enhance motivation and experiential learning in physics education. Future work will focus on assessing learning gains in classroom settings and extending the approach to additional thermodynamics concepts.

1 Introduction

Education has undergone a substantial transformation in recent decades, shifting from passive, lecture-oriented practices to more interactive, student-focused strategies (Torralba and Doo, 2020). This shift reflects broader changes in pedagogical theory, the proliferation of digital technologies, and evolving learner expectations. As educational research has demonstrated the significance of engagement in learning outcomes, institutions are increasingly investigating diverse teaching strategies to address students' needs and interests (Fisher et al., 2021). These strategies often aim to move beyond simple knowledge transmission, focusing instead on active participation, collaborative problem-solving, and the authentic application of concepts in real-world contexts.

Physics education, particularly in higher education, presents distinct challenges due to the theoretical nature of its concepts and the mathematical thinking it involves (Lestari et al., 2021). Topics such as thermodynamics and gas laws might appear abstract and unrelated to practical applications for many undergraduate students, making them difficult to comprehend and internalize (Sokrat et al., 2014). The traditional approach, characterized by reliance on textbooks, lectures, and standardized problem sets, has been essential for disseminating knowledge and developing foundational skills. However, such methods may not be sufficient to foster deep conceptual understanding or to sustain student motivation, especially in increasingly diverse classrooms with a range of learning preferences.

The challenge resides not only in presenting the material but also in enabling students to connect abstract principles to tangible experiences (Enyedy et al., 2011). Without this connection, learners may memorize formulas without fully grasping the underlying phenomena. In recent years, educational approaches that integrate theory and practice have gained prominence, aiming to transform learning from a passive reception of information into an active, inquiry-based process. This educational advancement has been supported by findings in cognitive science, which emphasize the role of active engagement and multi-modal interaction in long-term retention and transfer of learning (Lombardi and Shipley, 2021).

Embodied cognition theory offers a particularly relevant framework in this context, suggesting that cognitive processes are directly connected to the body's interactions with the physical environment (Farina, 2021). Rather than viewing thinking as an isolated, purely mental activity, embodied cognition posits that sensory and motor experiences shape how we understand and remember information. This theory aligns closely with active learning approaches in education, emphasizing student engagement through participation, manipulation, and exploration (Michael and Modell, 2003). These approaches allow students to construct their own knowledge by interacting with physical or simulated systems, experimenting with variables, and observing the results of their actions. In STEM subjects, where abstract relationships often require interpretation through multiple representations, such experiential methods can be particularly beneficial (Hernández-de Menéndez et al., 2019; Abrahamson et al., 2020).

As society advances and students become more familiar with technology from an early age, there is a growing demand for new teaching approaches that engage technologically proficient learners (Haleem et al., 2022). Technology now provides educators with a wide array of innovative, interactive learning tools that can support diverse educational objectives and cater to multiple learning styles. These tools can simulate complex phenomena, provide real-time feedback, and offer students opportunities to explore content at their own pace and depth. While many digital tools focus primarily on visual and auditory channels, physics education often demands an additional layer of sensory interaction to make abstract phenomena tangible. In this context, haptic devices stand out for their ability to provide users with tactile feedback, adding a sensory dimension that complements visual and auditory information (Fouad et al., 2023).

Visuo-haptic simulators combine the advantages of visual and tactile interaction in a single learning environment (Cox et al., 2025). They enable students to manipulate variables, such as force or pressure, and to experience the effects through both visual observation and physical sensation. By experimenting with forces, pressures, and visual cues, students can explore concepts actively and develop more robust mental models of complex phenomena (Benes et al., 2024). This dual-sensory engagement can make otherwise abstract relationships more concrete, enhance motivation, and promote a deeper understanding of the subject matter. In physics education, such tools have the potential to bridge the gap between theoretical derivations and experiential learning, providing students not only the opportunity to learn but also the chance to feel the laws of nature in action.

Despite increasing attention to immersive technologies in STEM education, limited research has examined how visuo-haptic simulators can enhance engagement and motivation in learning gas laws, particularly Boyle's Law. To address this gap, this study developed and evaluated a visuo-haptic simulator that integrates tactile and visual feedback to support active learning grounded in embodied cognition. The simulator allows students to manipulate pressure and volume variables, providing an immersive, hands-on experience that connects theoretical concepts to tangible interaction. The objective was to analyze students' perceptions of usability, satisfaction, and motivation when learning through multi-sensory interaction compared with traditional approaches. Accordingly, the following research questions were proposed:

How does the use of visuo-haptic simulators impact students' engagement with complex physics concepts, such as Boyle's Law?

What are students' perceptions of the effectiveness and educational value of visuo-haptic simulators compared to traditional instructional methods?

2 Related work

Haptic feedback technology has been widely explored in education for its ability to provide tactile sensations that enhance conceptual understanding (Novak and Schwan, 2021). This modality complements traditional visual and auditory instruction by engaging learners' kinesthetic channels, which are often underused in conventional classrooms. Beyond replicating real-world sensations, haptic systems can highlight key conceptual relationships and make invisible physical phenomena perceptible. The theoretical basis of visuo-haptic simulators lies in embodied cognition and active learning (McAnally and Wallis, 2022; Yang et al., 2021). These frameworks emphasize that knowledge is built more effectively when students interact physically with learning materials rather than passively observe them. By allowing learners to manipulate variables, experience resistance, and observe outcomes in real-time, visuo-haptic systems help form durable, transferable mental models that connect perception and reasoning.

2.1 Visuo-haptic learning approaches in physics education

In physics education, haptic feedback has been integrated into multiple studies to strengthen understanding of abstract and dynamic phenomena. Early work on embodied experience and kinesthetic learning established its pedagogical value. Han and Black (2011) investigated computer-based simulations for elementary students and found that those receiving both kinesthetic and force feedback achieved better recall and transfer than peers using non-haptic versions. Likewise, Olympiou and Zacharia (2012) showed that combining physical and virtual interaction supported richer representations of light and color concepts compared with single-modality conditions. Extending this evidence, Kontra et al. (2015) demonstrated through neuro-imaging that physical interaction activates motor and somatosensory regions linked to conceptual reasoning, reinforcing that embodied experience deepens scientific understanding.

Subsequent research examined how visuo-haptic systems model mechanical phenomena through interactive simulations. Yuksel et al. (2017) created HapStatics, a friction simulator that lets users feel resistance while manipulating virtual surfaces. Their constructivist design showed that combining visual and tactile cues improved coherence and reasoning. Extending this line, Qi et al. (2020) developed a visuo-haptic simulator for buoyancy, finding that learners using tactile feedback performed significantly better than those using visual feedback alone. Similarly, Hamza-Lup and Goldbach (2021) presented a gamified simulator for the Lorentz force that increased engagement and accuracy through real-time tactile interaction.

Other developments focused on structured frameworks and methodological improvements for designing visuo-haptic environments. Noguez et al. (2021) introduced the VIS-HAPT methodology, a systematic approach for building visuo-haptic learning systems aligned with Education 4.0. This framework reduced development time while improving usability and comprehension in physics simulations. In parallel, Magana and Balachandran (2017) examined haptic feedback in learning electric fields, showing that students used sensations of “push” and “pull” to form intuitive models of attraction, repulsion, and field geometry, emphasizing the role of sensorimotor experience in understanding invisible phenomena.

Researchers have also explored hybrid designs that combine visuo-haptic systems with other technologies to enhance motivation and autonomy. Garcia-Castelan et al. (2024) combined visuo-haptic simulation with generative AI to teach inclined-plane dynamics. Students interacted with a simulator and then used ChatGPT to test and refine their problem-solving skills, leading to higher learning gains and increased engagement. Likewise, Buonocore et al. (2023) investigated embodiment in industrial visuo-haptic training and found that greater perceived embodiment reduced workload and improved efficiency, underscoring how subjective presence influences performance.

Further studies have highlighted the instructional value of visuo-haptic simulations for friction and motion. Neri et al. (2023) applied the VIS-HAPT framework to a 3D simulator of frictional forces, showing that multi-sensory feedback strengthened conceptual grasp and learner satisfaction. Walsh et al. (2020) and Walsh and Magana (2023) analyzed sequencing and feedback modalities, finding that starting instruction with haptic feedback promotes embodied reasoning and that visuo-haptic simulations outperform physical interaction alone.

Together, this body of work demonstrates that combining visual and tactile feedback improves comprehension, engagement, and retention in physics education. Multi-sensory interaction supports the formation of embodied conceptual models that connect theory with tangible experience. However, most studies have focused on topics such as friction, buoyancy, or electromagnetism, leaving gas laws and thermodynamics largely unexplored. This gap motivates the present study, which applies visuo-haptic simulation to Boyle's Law to examine how tactile-visual integration influences engagement and perceived learning in conceptual physics.

2.2 Virtual and immersive environments in STEM learning

Virtual and immersive learning environments play a central role in STEM education by fostering experiential engagement, spatial understanding, and problem-solving. These approaches combine interactive visualization, project-based exploration, and multi-sensory simulation to situate learners in realistic contexts that enhance motivation and conceptual learning. Evidence shows that immersive tools can improve both cognitive and affective outcomes by enabling students to experience phenomena directly rather than observe them passively.

Talafian et al. (2019) examined immersive project-based STEM programs that support identity formation among underrepresented students. Using the Projective Reflection framework in a space-themed program, the authors found that immersive design and hands-on activities strengthened learners' identification with STEM and increased interest in related careers. Similarly, Makransky et al. (2020) reported that virtual reality experiences heightened situational interest and curiosity about science, influencing students' long-term aspirations. Together, these studies highlight the motivational and identity-building potential of immersive contexts in sustaining engagement with science learning.

A related line of research has focused on how immersive and augmented environments improve spatial reasoning and conceptual understanding through 3D interaction. Montalbo (2021) developed an augmented-reality chemistry platform that allowed learners to visualize and manipulate molecular structures, significantly improving spatial reasoning. Acevedo et al. (2024) found that virtual environments for exploring electric fields enhanced conceptual accuracy and engagement. These results are consistent with Chiang and Liu (2023) who showed that extended reality systems with real-time feedback improved concentration and comprehension in engineering education. Together, these findings suggest that immersive visualization facilitates a connection between abstract concepts and perceptual experience, thereby promoting a deeper understanding.

Immersive technologies have also been used as scalable alternatives to traditional laboratories and workshops. Shu and Huang (2021) tested virtual Makerspaces that replaced physical workshops, revealing that VR-based design instruction improved self-efficacy and creativity. In manufacturing education, El-Mounayri et al. (2016) and Rogers et al. (2018) developed the Advanced Virtual Manufacturing Lab, a VR system replicating CNC machining. Both studies showed that students achieved comparable learning outcomes to those from physical training while benefiting from the safety and accessibility. Although usability issues such as motion discomfort persisted, these results support immersive environments as effective complements to hands-on laboratory instruction.

Beyond replicating physical spaces, immersive learning enhances collaboration and embodiment through sensory engagement. Webb et al. (2022) developed a haptic-enabled VR model of a cell membrane that helped students perceive nanoscale interactions, improving visualization and authenticity. In another study, Johnson-Glenberg et al. (2021) compared desktop and embodied VR environments for teaching natural selection, showing that while both improved learning, embodied VR promoted greater presence, enjoyment, and spatial transfer. Zhao et al. (2020) reached similar conclusions in a comparison of virtual and physical field trips, finding equal or higher satisfaction in virtual conditions. Collectively, these studies suggest that embodiment and presence foster affective engagement, turning observation into participation.

Recent research emphasizes that the impact of immersive technologies depends on instructional design more than immersion alone. Lee et al. (2024) found that VR and AR classrooms increased motivation and engagement but produced no significant differences in test performance, suggesting that pedagogical scaffolding remains essential for cognitive gains. Likewise, Buonocore et al. (2023) demonstrated that perceived embodiment influences workload and task efficiency, emphasizing the importance of human factors in immersive learning design.

Overall, research across AR, VR, and XR technologies shows that immersive environments can enhance motivation, engagement, and understanding by combining visualization, manipulation, and feedback. Yet, these systems often emphasize visual immersion while overlooking tactile or kinesthetic interaction as a pathway to conceptual understanding. This limitation underscores the contribution of visuo-haptic systems, which unite both sensory dimensions to promote embodied cognition. The present study extends this line of inquiry by examining how a visuo-haptic simulator for Boyle's Law integrates immersive and tactile feedback to support engagement and intuitive learning in physics.

2.3 Engagement in technology-mediated education

Beyond physics and visuo-haptic learning, research on engagement in technology-mediated education provides insight into how interactivity and feedback sustain motivation and participation. Engagement, typically described through behavioral, cognitive, and emotional dimensions, depends strongly on instructional design, social interaction, and learner autonomy. These perspectives help explain how the multi-sensory interactivity of visuo-haptic simulators can promote active involvement.

Li and Lam (2015) studied engagement in online courses and found that clear structure, instructor presence, and peer support enhance behavioral, cognitive, and emotional participation. The study showed that well-timed schedules and feedback improved behavioral engagement, while intrinsic motivation strengthened cognitive investment. Similarly, Owusu-Agyeman and Larbi-Siaw (2018) reported that self-regulated learning strategies, collaboration, and institutional support foster motivation in higher education, emphasizing that structured interaction promotes active and reflective learning. Together, these studies suggest that digital learning is most effective when it supports reciprocal interaction, autonomy, and connectedness.

Studies during the COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted how interactivity and feedback shape engagement in both synchronous and asynchronous settings. Lau et al. (2022) found that task-based activities with immediate visual feedback improved engagement across all dimensions. Similarly, Yavani (2023) showed that interactive pedagogical actions such as discussions and pair dialogues produced the highest motivation, although infrastructure limitations sometimes hindered participation. Both studies emphasized that technology should be combined with pedagogical creativity to maintain focus and motivation in online learning.

Other research explored how digital platforms and constructivist approaches enhance engagement and self-efficacy. Robillos (2023) demonstrated that combining metacognitive strategies with the FlipGrid platform improved students' speaking confidence and reflection through peer feedback. Bray et al. (2015) integrated Realistic Mathematics Education with the Bridge21 model, finding that project-based digital learning increased engagement and confidence while linking theory with practice. These studies demonstrate that meaningful engagement arises from integrating technology with learner-centered design, rather than relying solely on technology use.

Technological mediation can also drive institutional and cultural change. Brown et al. (2019) analyzed the shift of Russian higher education toward open, participatory, and gamified learning, showing that technology-supported pedagogies enhanced motivation, autonomy, and creativity. Gamification elements correlated with higher enjoyment and strategic thinking, demonstrating that digital interactivity can influence educational culture and policy as well as individual engagement.

Research on mobile and experiential learning illustrates how technology fosters sensory and social engagement in real-world settings. McClain and Zimmerman (2016) found that an iPad-based e-Trailguide promoted observation, gesture, and tactile exploration during outdoor activities, supporting a “heads-up, hands-on” learning approach. Mayer and Schwemmle (2023) extended this to higher education, showing that technology-mediated experiential learning increases accessibility and autonomy but can reduce spontaneous interaction, requiring instructors to act as proactive mentors to sustain motivation. These findings suggest that effective engagement hinges on striking a balance between digital fluency and human connection.

Finally, engagement frameworks have been applied to domain-specific physics education. Mohd Sharif et al. (2021) developed a tangible Boyle's Law apparatus that improved understanding and interest compared to lecture-based teaching, yet lacked digital or haptic interactivity. This highlights a clear gap: while technology-mediated engagement is well established, few studies have examined how combining tactile and visual feedback can enhance engagement with abstract physics concepts.

Overall, prior studies converge on three ideas. First, engagement in technology-mediated education depends on aligning interactivity, feedback, and autonomy. Second, effective engagement requires a balance between technological features and pedagogical goals to sustain attention. Third, sensory and experiential modes promote deeper learning by transforming students from passive observers into active participants. Building on these insights, the present study employs a visuo-haptic simulator that combines interactivity, feedback, and embodiment to foster engagement with Boyle's Law through a direct, multi-sensory experience.

2.4 Contributions of this study

Building on the expanded body of research reviewed above, this study makes three main contributions to the field of visuo-haptic and technology-mediated learning:

Extension of visuo-haptic learning to gas laws: previous research has primarily focused on friction, buoyancy, or electromagnetism. This study introduces a visuo-haptic simulator specifically designed for Boyle's Law, demonstrating that tactile-visual interaction can effectively support comprehension of thermodynamic principles.

Integration of embodied cognition within a multi-sensory, active-learning framework: the simulator combines real-time tactile resistance and visual feedback to transform abstract physical relationships into perceptible experiences, operationalizing embodied cognition through interactive exploration.

Empirical evaluation of user engagement and perceived educational value: using a mixed-method approach, the study provides quantitative and qualitative evidence that visuo-haptic interaction enhances students' engagement, motivation, and satisfaction compared with traditional learning. These findings complement prior studies that emphasized conceptual outcomes but rarely assessed affective and usability dimensions.

Through these contributions, the study aims to expand the scope of visuo-haptic research by situating tactile-visual interactivity within thermodynamics and by linking embodied cognition to engagement theory from technology-mediated education. The study demonstrates that meaningful learning arises not only from sensory realism but from the alignment of interactivity, feedback, and autonomy–principles supported by broader literature on immersive and digital learning environments. By addressing an underexplored domain and integrating empirical evaluation of engagement, this work advances the understanding of how visuo-haptic systems can enrich science education through experiential and motivational pathways.

3 Materials and methods

The study's main objective was to assess students' perceptions of learning with the simulator in comparison to traditional methods. This section describes the materials and methods used to design, develop, and implement the visuo-haptic simulator. A streamlined VIS-HAPT methodology (Noguez et al., 2021) was employed to ensure the accuracy of simulations of physical interactions. The Haptic Device Integration for Unity (HaDIU) framework (Escobar-Castillejos et al., 2020) was used to integrate haptic feedback seamlessly.

3.1 Design of the visuo-haptic learning experience

In physics, abstract concepts may be complex for some students to internalize because they involve relationships that are not directly observable. One such principle is Boyle's Law, which states that for an ideal gas in a closed system at constant temperature, the pressure is inversely proportional to the volume, meaning that the product of pressure and volume remains constant:

This subsection presents the design of a visuo-haptic learning scenario that provides students with an intuitive and engaging way to experience Boyle's Law through both visual representation and tactile interaction.

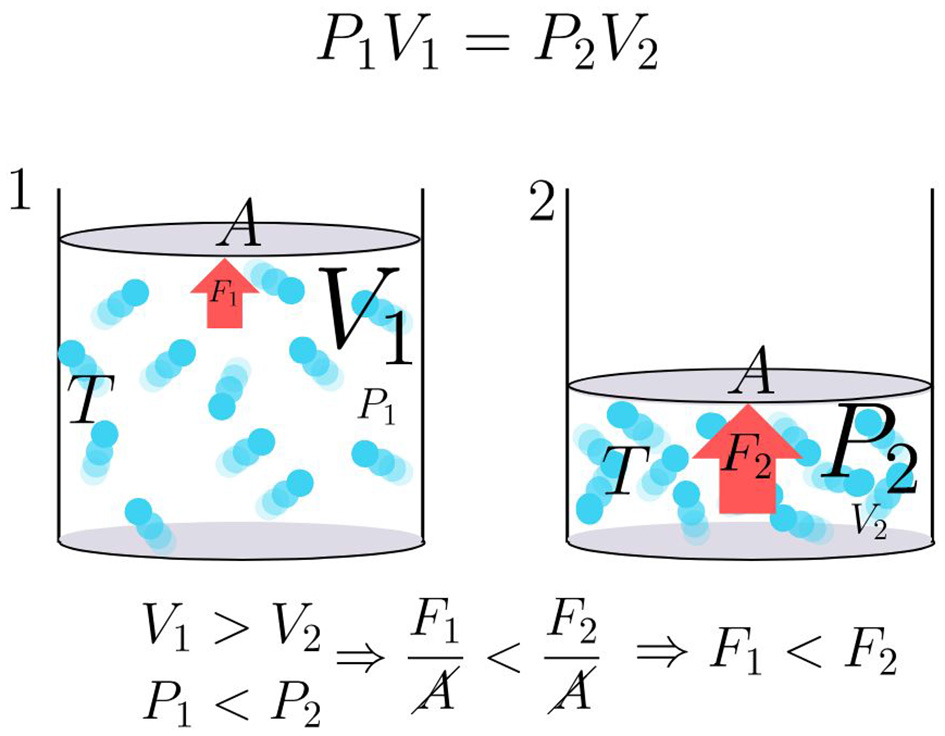

Figure 1 illustrates a simplified model of this phenomenon using a gas confined in a cylinder with a movable piston. This setup provides an accessible way to demonstrate that compression (decreasing the gas volume) increases pressure, while expansion decreases it, all under isothermal conditions.

Figure 1

Illustration of Boyle's law showing the effects of compression on an ideal gas in a closed system: (1) initial state, where the gas occupies a larger volume with a lower pressure; and (2) compressed state, where the reduced volume increases the internal pressure and force exerted on the piston.

In the initial state (Figure 1.1), the piston is positioned higher, and the gas occupies a larger volume V1. The gas molecules are more widely spaced, so the frequency of collisions with the piston surface is lower, resulting in a relatively small pressure P1. This pressure produces a force F1 on the piston, determined by the relationship F = P·A, where A is the cross-sectional area of the piston.

In the second state (Figure 1.2), the piston is pushed downward, reducing the available volume to V2. As the same number of molecules now occupies a smaller space, their density increases, leading to more frequent collisions with the piston surface. This greater collision rate elevates the pressure to P2, thereby increasing the exerted force to F2. Because A is constant, the increase in pressure directly translates into a proportional increase in force, so that F2>F1. This direct cause-and-effect relationship exemplifies the inverse relationship between volume and pressure, enabling learners to connect microscopic particle interactions with macroscopic quantities such as pressure and force.

The visuo-haptic simulator designed for this learning experience extends the explanatory power of the traditional diagram. Students not only observe the compression process visually but also feel the increased resistance on the piston through haptic feedback. This dual-channel engagement strengthens conceptual understanding by linking the abstract inverse relationship between pressure and volume to tangible sensory experience. By situating learners in an active role, the simulation motivates exploration and reinforces comprehension of one of the foundational gas laws in physics.

3.2 Visuo-haptic simulator design and development

The visuo-haptic simulator was developed in Unity 2021.3 LTS (64-bit) and integrated with the HaDIU framework, the latest stable in-house version described in Escobar-Castillejos et al. (2020). The framework enabled communication between the Unity environment and external haptic devices, facilitating real-time bidirectional feedback. The simulator employed Unity's built-in physics engine to accurately model the inverse relationship between gas pressure and volume under isothermal conditions, allowing users to both visualize and physically experience this phenomenon through synchronized visual and tactile feedback.

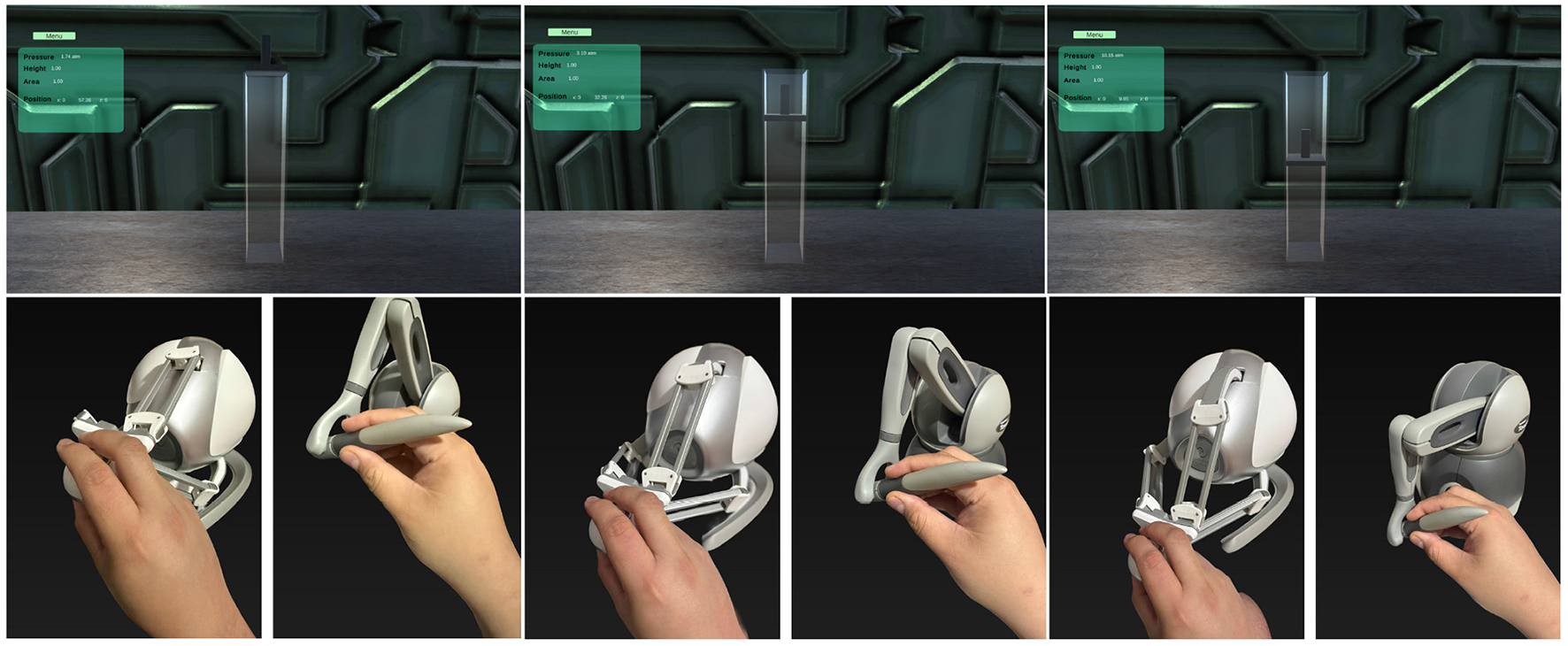

The simulation centers on a virtual piston-cylinder system that users manipulate via a lever connected to the piston. As the lever is pressed downward, the available gas volume decreases, and the system calculates the corresponding pressure changes in real time. The pressure values are displayed numerically and mapped to proportional tactile resistance using the linear function F = P·A, where A represents the piston's cross-sectional area. This relationship ensures that an increase in pressure directly translates into greater force feedback, reinforcing Boyle's Law (P1V1 = P2V2) through embodied interaction (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Visuo-haptic simulator interaction process illustrating piston displacement and corresponding hand movement on the haptic device. As the piston is displaced, the simulator calculates the corresponding pressure values and displays them in real time, while also delivering proportional resistance through the haptic device. This combination of visual and tactile feedback highlights the inverse relationship between pressure and volume.

3.2.1 Technical implementation

The simulator was executed on Windows 11 workstations equipped with Intel Core i7-10700K CPUs, 32 GB RAM, and Nvidia GeForce RTX 3070 GPUs, ensuring stable rendering and low-latency haptic response. Device calibration was performed through the HaDIU configuration module to standardize stiffness coefficients (0.8 N/mm) and force-feedback ranges (0–8 N) across the Novint Falcon and Geomagic Touch systems. Each device was pretested to verify positional accuracy and equivalent resistance under identical pressure conditions, ensuring consistent tactile perception across users.

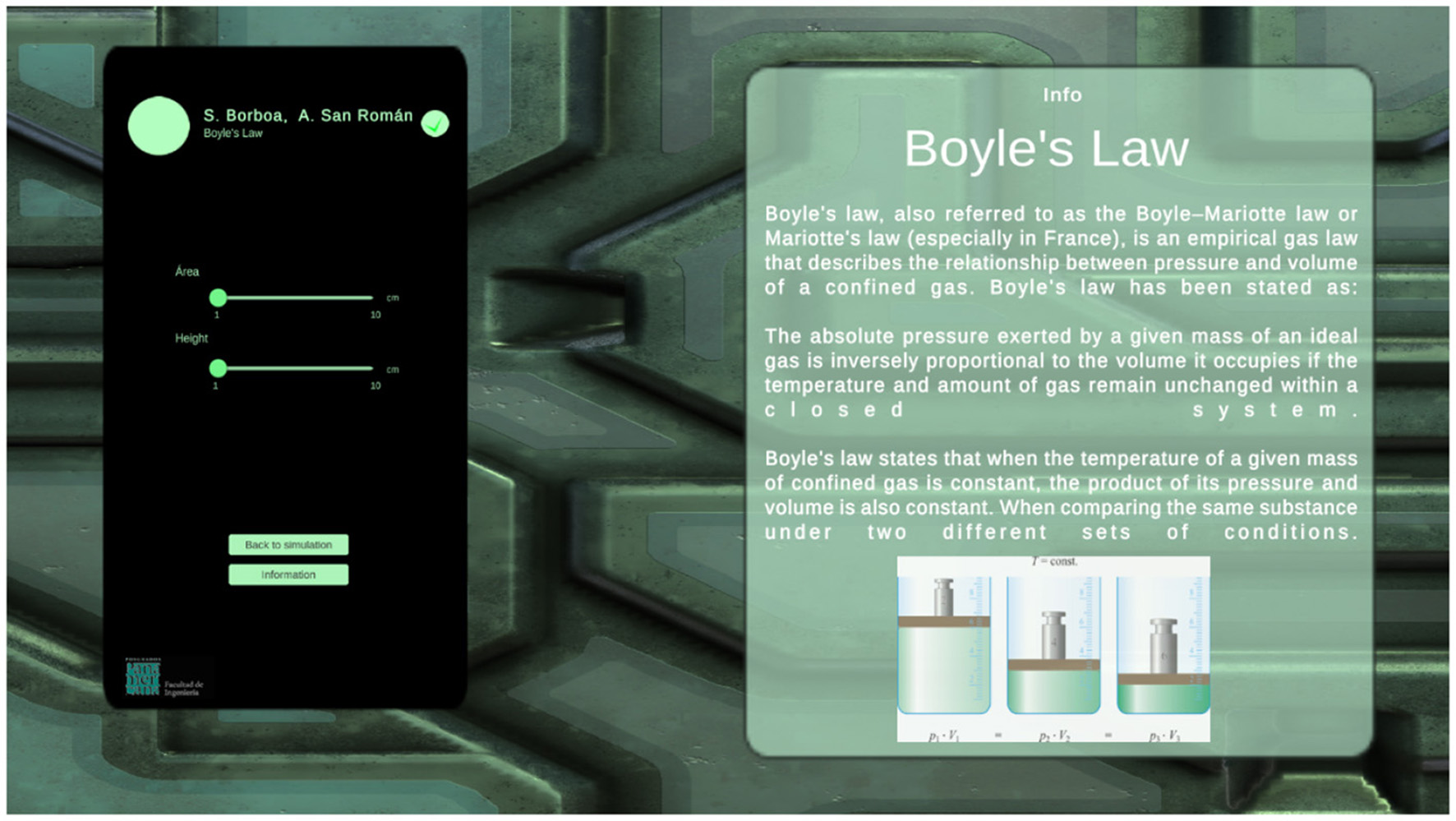

The graphical user interface (GUI) was designed for clarity and usability (Figure 3). Two sliders allow for the adjustment of initial parameters, including cylinder height and area. At the same time, an informational panel provides a concise overview of Boyle's Law, situating the simulation within its theoretical context. A real-time data panel displays pressure, height, and piston position values, allowing students to verify simulated outcomes and cross-check them with theoretical expectations.

Figure 3

Graphical user interface of the visuo-haptic simulator. The GUI includes adjustable parameters, real-time feedback on system variables, and an informational panel on Boyle's Law to support conceptual understanding.

By integrating visual, textual, and haptic modalities, the simulator provides an active, multi-sensory environment in which students can experimentally explore the pressure-volume relationship, transforming abstract gas laws into tangible learning experiences.

3.3 Testing of the visuo-haptic simulator

3.3.1 Measures

To evaluate the effectiveness and user experience of the visuo-haptic simulator, a mixed-methods approach was adopted, combining standardized survey instruments with qualitative interviews. It allowed both quantitative insights into students' satisfaction and qualitative insights into their perceptions, engagement, and challenges.

3.3.1.1 End-user satisfaction survey

The study employed Doll and Torkzadeh (1988)'s End-User Computing Satisfaction (EUCS) survey, an established instrument for assessing user satisfaction with interactive computer systems. This instrument was selected for its comprehensive coverage of factors critical to educational technologies. The EUCS survey evaluates five principal dimensions:

Content: assesses the relevance, precision, and comprehensiveness of the information supplied by the simulator.

Accuracy: evaluates the reliability of the simulator outputs, specifically whether the pressure-volume data and haptic responses reflected Boyle's Law correctly.

Format: examines the clarity of information presentation, including the GUI layout, data visualization, and interpretability of simulation results.

Ease of use: measures the user-friendliness of the simulator, focusing on navigation, interaction with the lever, and intuitiveness of parameter adjustments.

Timeliness: evaluates the responsiveness of the simulator in generating outputs and haptic feedback in real time.

Responses were collected using Google Forms on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated strong dissatisfaction and 5 showed strong satisfaction. Quantitative data were analyzed using Python, leveraging the pandas library for data processing and matplotlib for statistical visualization. This analysis provided descriptive statistics, comparative distributions across dimensions, and graphical summaries of student satisfaction.

3.3.1.2 Qualitative interviews

To complement the EUCS survey, semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with participants to gain a more profound understanding of their engagement with the visuo-haptic simulator. Interviews were particularly valuable for eliciting reflections on experiential learning, identifying potential usability issues, and uncovering perceptions that quantitative scores alone could not capture. The open-ended questions included:

Can you describe your experience using the visuo-haptic simulator to learn about Boyle's Law?

In what ways did the interaction with the simulator help you understand the inverse relationship between pressure and volume?

How engaging did you find the simulator compared to traditional classroom-based learning?

What challenges or difficulties did you encounter while using the simulator, and how did these affect your learning experience?

Do you believe the simulator provided advantages over conventional learning methods, and if so, which were most valuable?

In your opinion, how could visuo-haptic simulators be applied to other areas of physics or to different subjects?

3.3.2 Participants and recruitment

A total of 39 undergraduate engineering students from Universidad Panamericana voluntarily participated between August and November 2024. Participants were enrolled in the engineering program and had taken, or were currently taking, physics-related courses as part of their curriculum. Recruitment was conducted through course announcements and faculty-distributed invitations. Participation was voluntary, with no academic incentives or rewards.

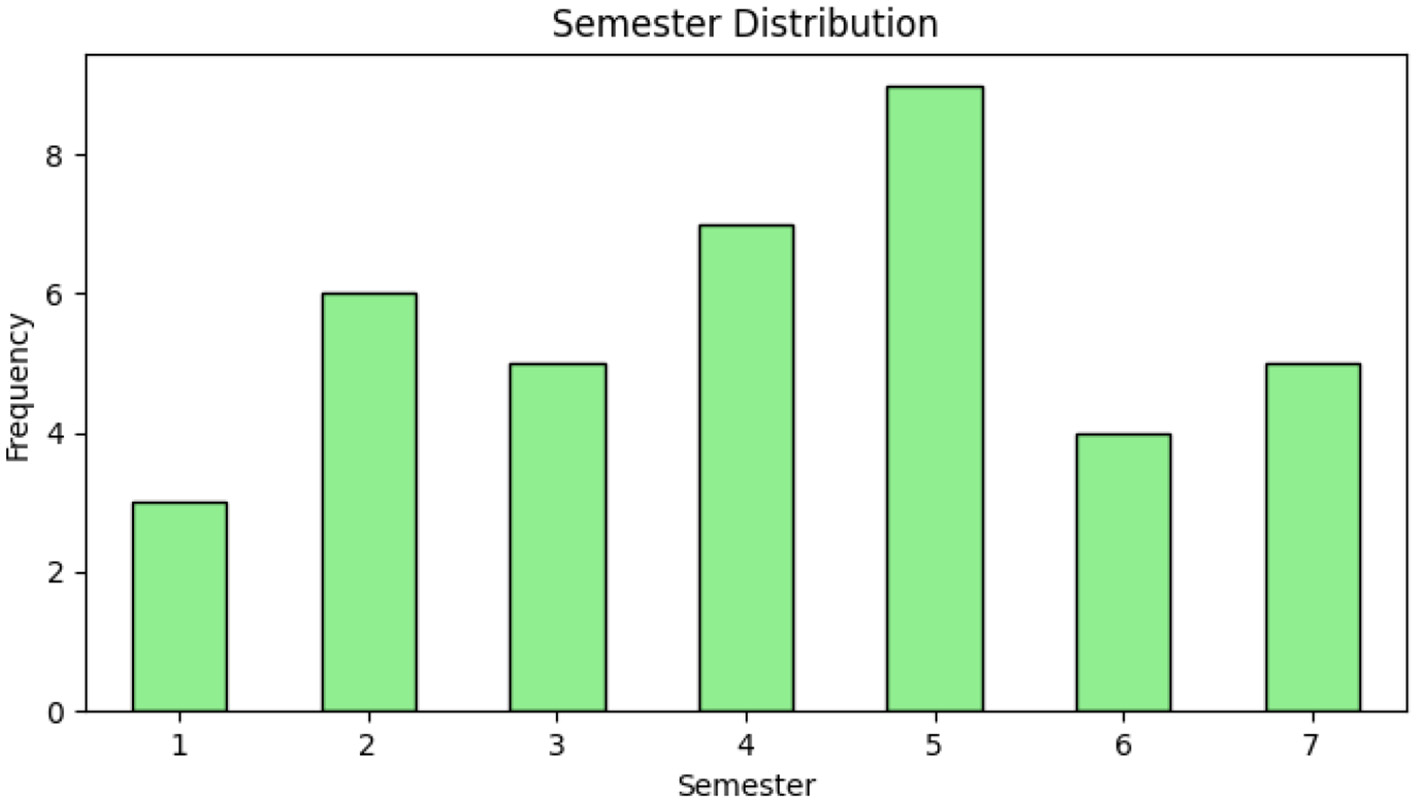

Inclusion criteria required enrollment in the engineering program and the ability to attend one simulator session. Students with prior experience in haptic research were excluded to minimize bias. The final sample included 25 male and 14 female students, with ages ranging from 18 to 22 years (M = 20.1, SD = 1.4). Figure 4 shows the semester distribution, which ranged from the first to the seventh semester. The largest cohort was in the fifth semester (nine students), followed by the fourth (seven students) and the second (six students). This range reflects a progression from early to advanced stages of the engineering program, ensuring diversity in prior physics experience and familiarity with simulation-based learning. Lower-division students (semesters 1–3) were typically 18–19 years old and had completed introductory physics courses, while upper-division students (semesters 4–7) were generally 21–22 years old and had prior laboratory experience with computer-based learning tools.

Figure 4

Semester distribution of participants.

The sample size (n = 39) was determined by equipment and scheduling constraints, as only twelve haptic devices were available per session. This number provided a balance between logistical feasibility and the opportunity to observe diverse user responses across semesters. Because the study was exploratory and focused on perceptions rather than statistical inference, no formal power analysis was conducted. The implications of this sample size are further discussed in the Limitations subsection of the Discussion. Nonetheless, the sample size is consistent with those used in comparable visuo-haptic simulator studies (e.g., Yuksel et al., 2017; Qi et al., 2020).

Additional demographic information, such as GPA, was not collected, as the focus of this study was on students' perceptions of usability, satisfaction, and engagement rather than academic performance. Although drawn from a single institution, participants represented a cross-section of students within the engineering program, offering reasonable variation in prior physics experience and familiarity with technology-enhanced learning environments.

3.3.2.1 Experimental devices and control of variability

Two haptic devices were employed: ten Novint Falcon and two Geomagic Touch systems. Both were calibrated using identical parameters within the HaDIU framework to ensure consistent force feedback ranges and stiffness coefficients. Each simulation was pre-tested for equivalent tactile resistance under identical virtual pressure settings. While both devices delivered comparable perceptual experiences, minor differences in ergonomics and movement range may have influenced users' tactile perception. This variability is acknowledged as a potential confounding factor and is further discussed in the study's limitations.

3.3.2.2 Procedure

Each session followed a structured sequence:

Introduction (10 min). The facilitator welcomed students, explained the objectives of the study, and presented an overview of the visuo-haptic simulator. Instructions on using the GUI, adjusting parameters, and interpreting outputs were provided during a live demonstration.

Initial interaction (5 min). Participants were encouraged to freely explore the simulator, navigating the GUI and experimenting with adjustable variables. This familiarization stage reduced potential usability barriers and allowed students to gain confidence with the device.

Guided exploration (15 min). Participants manipulated the simulator in a structured way to observe Boyle's Law in action. They were guided to note how reducing the piston's height increased pressure and to compare real-time haptic and visual feedback, reinforcing theoretical-experimental connections.

Independent use (20 min). Each student worked individually with the simulator, exploring different scenarios and noting observations. This stage provided ample time for hands-on experimentation, allowing participants to apply concepts independently and reinforce understanding through practice.

Feedback collection (10 min). At the end of each session, students completed the EUCS questionnaire for quantitative feedback. Immediately afterward, individual interviews were conducted with selected participants to reflect on their learning experience, challenges, and perceived advantages of the simulator compared to traditional methods.

3.3.2.3 Interview sampling and qualitative analysis

Following completion of the EUCS survey, participants were invited for interviews using purposive sampling to capture a range of satisfaction levels and perspectives based on survey responses and availability. Interviews were transcribed verbatim from written notes and analyzed using thematic analysis following Kiger and Varpio (2020). Two researchers independently coded transcripts, identified recurring patterns related to engagement, usability, and conceptual understanding, and refined themes through consensus to ensure interpretive validity.

3.3.2.4 Data collection and rationale

By combining the EUCS survey data with qualitative interviews, the evaluation captured both broad patterns of satisfaction and individual perceptions of motivation and usefulness. This mixed-methods approach ensured that findings reflected not only the simulator's usability but also students' attitudes toward its potential to support learning in classroom contexts.

4 Results

The analysis combined quantitative survey data and qualitative thematic coding of interview transcripts to provide a comprehensive view of students' perceptions of the visuo-haptic simulator. Overall, results indicate high satisfaction with usability and responsiveness, as well as positive affective engagement with the learning experience. Qualitative findings complement these patterns by revealing more profound insights into how students experienced interactivity, comprehension, and motivation.

4.1 End-user satisfaction survey results

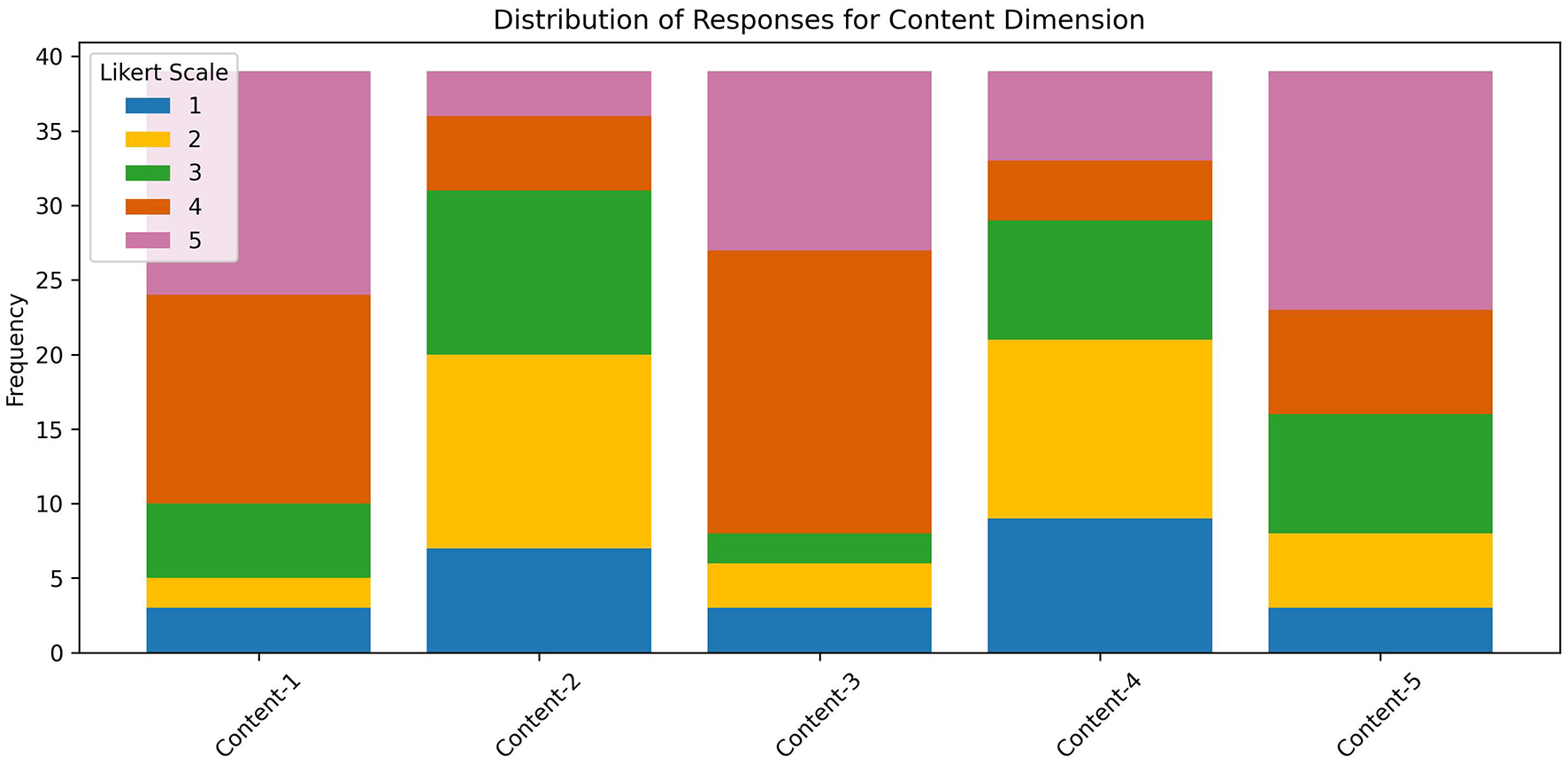

The content dimension received an average score of 3.35, indicating an acceptable level of satisfaction with the simulator's relevance, precision, and comprehensiveness (Figure 5). Although students found the content helpful, several suggested that expanding the explanations and providing additional supporting information could offer a richer conceptual context. This indicates that while the simulator effectively conveys Boyle's Law, it may benefit from supplementary guidance or more detailed annotations.

Figure 5

Distribution of responses for the content dimension.

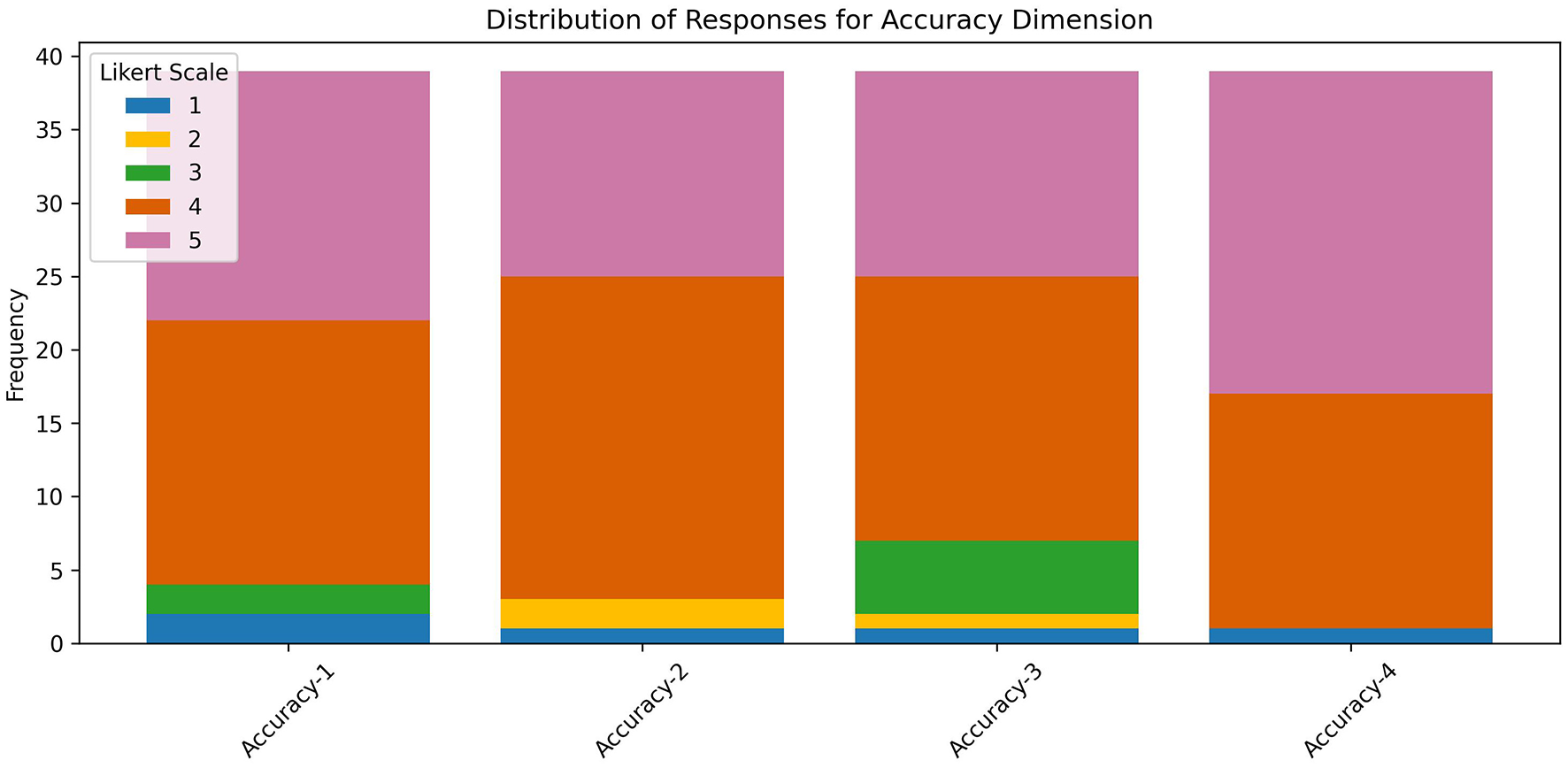

The accuracy dimension averaged 4.26, indicating strong confidence in the simulator's ability to provide reliable outputs (Figure 6). Students consistently perceived that the displayed values and haptic responses aligned with Boyle's Law. This high rating reflects the trustworthiness of the mathematical model and the physical interactions, a crucial factor for educational tools where conceptual accuracy is central to learning outcomes.

Figure 6

Distribution of responses for the accuracy dimension.

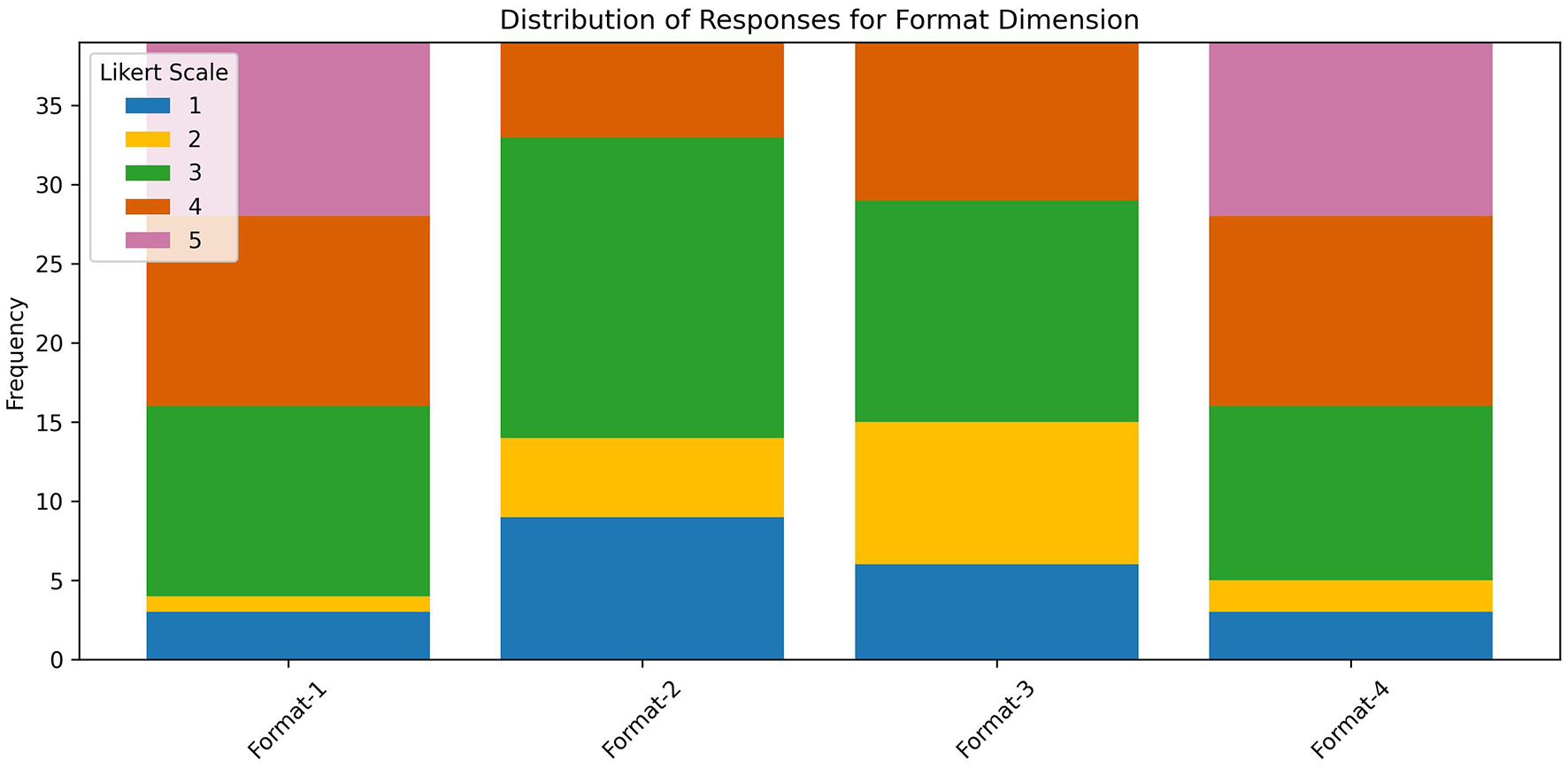

The format dimension, related to the structuring and clarity of information, attained an average score of 3.16 (Figure 7), the lowest among the five dimensions. This finding suggests that some students experienced difficulties with the interface's visual layout. Open comments suggested that dense text blocks and the 3D navigation posed challenges. Enhancing visual hierarchy, spacing, and navigation cues could substantially improve students' perception of the simulator's usability.

Figure 7

Distribution of responses for the format dimension.

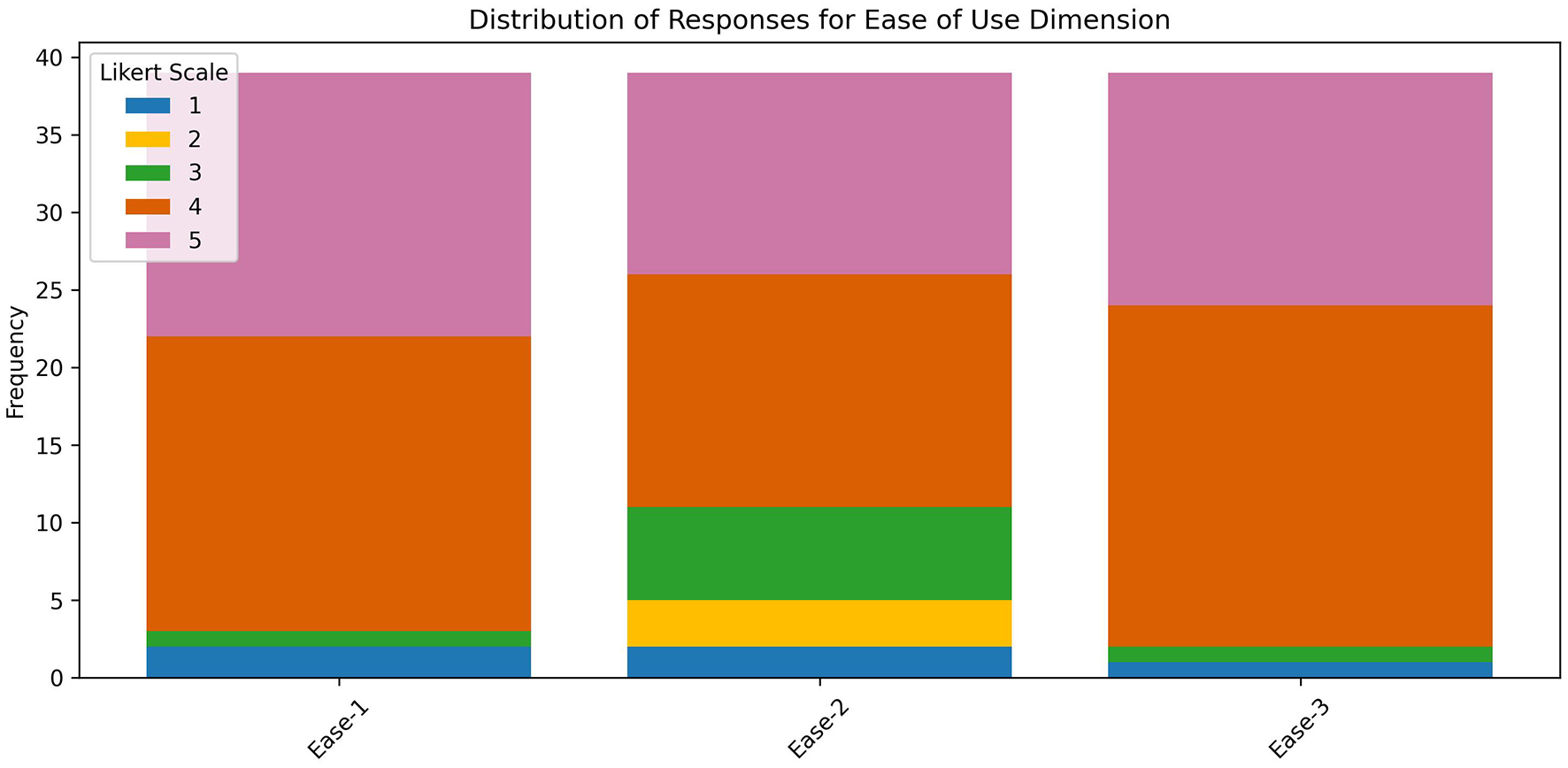

The ease of use dimension scored an average of 4.14, showing that students generally found the simulator intuitive (Figure 8). Most participants reported minimal difficulty in adjusting parameters and interpreting outputs after the brief introduction phase. This suggests that the simulator achieved a balance between functionality and simplicity, making it accessible even for students with limited experience in haptic technologies.

Figure 8

Distribution of responses for the ease of use dimension.

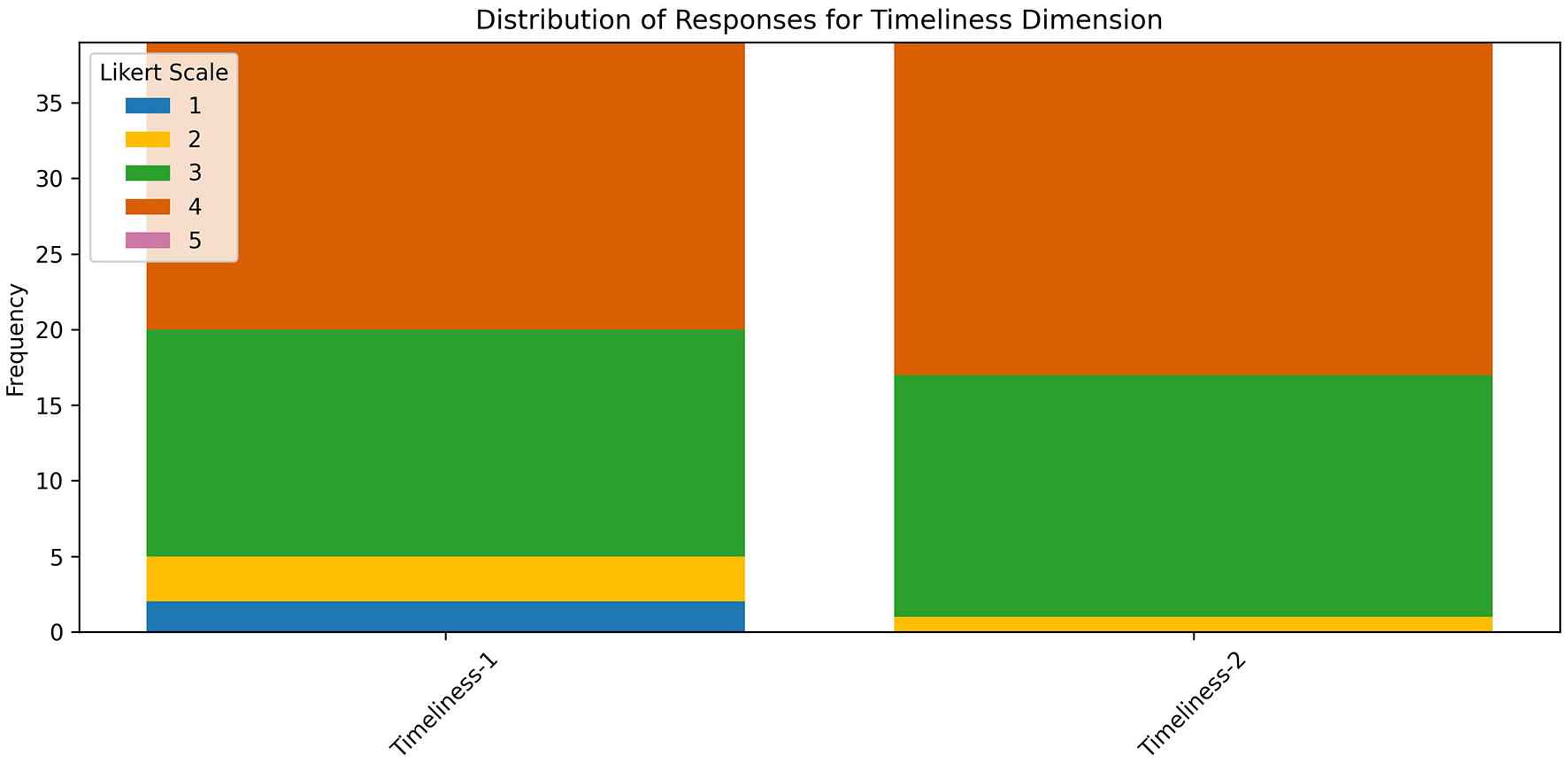

The highest average score was attained in the timeliness dimension, with a mean of 4.40 (Figure 9). Students particularly valued the immediacy of visual updates and haptic responses when manipulating the piston. The real-time feedback helped sustain engagement and supported experiential learning by linking cause and effect in real time.

Figure 9

Distribution of responses for the timeliness dimension.

4.2 Thematic analysis of interviews

Semi-structured interviews were analyzed using a reflexive thematic analysis approach following Kiger and Varpio (2020). Two researchers independently reviewed all transcripts, conducted open coding, and iteratively grouped codes into themes that reflected recurring patterns in participants' experiences. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussions to enhance interpretive validity. This process yielded four major themes: (1) Engagement and Enjoyment, (2) Usability and Interface Design, (3) Conceptual Understanding and Embodied Learning, and (4) Perceived Educational Value and Transferability. Table 1 summarizes these themes with representative quotations.

Table 1

| Theme | Illustrative student comments |

|---|---|

| Engagement and enjoyment | “It was fun and felt like a game, but I was actually learning something.” “I stayed interested the whole time because I could see and feel the pressure changing.” |

| Usability and interface design | “The controls were intuitive after a few minutes.” “Some buttons and text were small; a short tutorial would help new users.” |

| Conceptual understanding and embodied learning | “Feeling the resistance made the concept of pressure-volume easier to grasp.” “When I moved the piston and felt it get harder to push, I understood what the formula really means.” |

| Perceived educational value and transferability | “This tool could help in other topics like thermodynamics or chemistry.” “It's a good complement to theory because you can experiment safely and repeat as much as you want.” |

Main themes identified through thematic analysis of interviews.

4.3 Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings

The convergence between survey and interview data reinforced the reliability of the results. High scores in the accuracy, ease of use, and timeliness dimensions corresponded with qualitative reports describing the simulator as “precise,” “responsive,” and “easy to use.” Conversely, the lower score in the format dimension aligned with comments about dense on-screen information and the need for more precise guidance.

Students' remarks consistently reflected greater motivation and curiosity when using the simulator than during traditional instruction. The tactile interaction was frequently cited as a distinctive feature that made the learning process more memorable and intuitive. Participants also expressed interest in broader applications of visuo-haptic tools to other physics topics, emphasizing their potential to transform abstract equations into interactive, exploratory experiences.

4.4 Summary of key patterns

Across both data sources, four recurrent patterns emerged:

High affective engagement: students described the experience as enjoyable and motivating.

Positive usability perceptions: most participants found the simulator intuitive after minimal guidance.

Enhanced conceptual linkage: tactile feedback helped connect theoretical relationships to sensory experience.

Transferability potential: students envisioned using visuo-haptic simulators in other STEM subjects.

These themes provide a coherent interpretation of how multi-sensory interaction supports engagement, understanding, and perceived educational value in technology-mediated physics learning.

5 Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the visuo-haptic simulator for understanding Boyle's Law was positively received by students and promoted strong engagement with a traditionally abstract concept. The combination of tactile and visual components appears to have benefited both the intuitive grasp of theoretical relationships and students' motivation to interact with the material. Participants consistently described the experience as interactive, entertaining, and more engaging than conventional approaches, indicating that the simulator supported a transition from passive observation to active exploration. This finding aligns with broader discussions in educational technology, emphasizing the importance of immersion, interactivity, and experiential engagement as essential components for meaningful learning experiences.

One of the central contributions of the simulator lies in its capacity to render abstract physical principles into tangible interactions. The simulator allowed participants to manipulate the piston and observe pressure changes in real-time. This corresponds with the principles of embodied cognition, which suggest that learning is strengthened when abstract concepts are anchored in sensory and motor experiences. This approach differs from conventional didactic instruction, in which students may memorize formulas without developing an intuitive understanding of the concepts. Although this study did not directly measure learning outcomes, participants' responses suggest that multi-sensory interaction could increase curiosity and perceived comprehension of complex scientific relationships.

The motivational aspect is equally significant. Participants' preference for the simulator over traditional methods suggests that interactive, technology-enhanced environments may encourage more positive attitudes toward physics, a discipline often perceived as challenging. Engagement is essential for maintaining interest in STEM fields, and tools such as this simulator may help counteract disengagement by fostering motivation and enjoyment. The tactile dimension, in particular, introduced an element of playfulness and exploration into the learning process, reinforcing the notion that affective experiences can enhance willingness to learn. Previous research on haptic interfaces in education has reported similar outcomes, indicating that touch-based interactivity can enhance curiosity and promote sustained attention. The present study extends these observations by situating haptic learning within the context of gas laws.

5.1 Comparison with prior studies

The engagement outcomes observed in this study align with previous research demonstrating that interactivity and multi-sensory feedback play central roles in promoting active learning. Similar to Qi et al. (2020) and Walsh and Magana (2023), students in this study emphasized the experiential value of physically feeling the pressure-volume relationship, suggesting that the synchronization of tactile and visual feedback reinforces intuitive understanding of abstract concepts. Both prior studies reported that combining haptic and visual cues improved motivation and conceptual clarity–findings consistent with the high engagement and satisfaction reported here. However, while those investigations focused on buoyancy and friction, the present work extends visuo-haptic learning to gas laws, providing empirical evidence that multi-sensory interaction can facilitate understanding in thermodynamics, a topic largely unexplored through haptic simulation.

Beyond visuo-haptic contexts, the findings also resonate with research on engagement in technology-mediated and immersive learning environments. Consistent with Lau et al. (2022), interactive structures and immediate feedback emerged as major drivers of motivation and sustained attention. These dynamics parallel the behavioral, cognitive, and affective engagement mechanisms described by Li and Lam (2015) and Owusu-Agyeman and Larbi-Siaw (2018), where learner autonomy and reciprocal feedback loops enhance participation and persistence. In this study, tactile resistance and real-time visual updates served comparable functions, creating a responsive dialogue between the learner and system that sustained curiosity and focus.

Comparable trends have been observed in immersive and virtual reality studies (e.g., Talafian et al., 2019; Shu and Huang, 2021; Johnson-Glenberg et al., 2021), where experiential design and sensory presence foster engagement and self-efficacy. The present study reinforces these observations while demonstrating that similar benefits can be achieved through localized visuo-haptic interaction without the infrastructural demands of large-scale immersive setups. This distinction highlights the scalability and accessibility of visuo-haptic tools for classroom implementation, particularly in resource-limited educational environments.

These comparisons position the present study as a bridge between three domains: (1) visuo-haptic learning focused on embodied cognition, (2) immersive and extended-reality research emphasizing presence and spatial interaction, and (3) engagement studies examining feedback and autonomy in digital education. By integrating these perspectives, the study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of how tactile-visual feedback can simultaneously support conceptual, motivational, and experiential dimensions of learning in physics education.

5.2 Design and usability considerations

Despite these strengths, several areas for improvement became evident. The relatively lower ratings in the format dimension indicate that the simulator's visual presentation and interface design could be optimized. Some students reported difficulty quickly interpreting information when the layout appeared dense. Such findings underscore the importance of applying usability principles in educational tool design, where clarity and simplicity are crucial to prevent cognitive overload. Addressing these concerns in future iterations could involve restructuring the display to emphasize key variables, using color coding, or integrating progressive disclosure to minimize distractions. Additionally, qualitative feedback suggested that including a short tutorial or guided walkthrough would improve accessibility for first-time users. These recommendations emphasize the importance of considering not only core functionality but also the broader user experience, encompassing onboarding and learner guidance.

5.3 Perceived educational value and future applications

Another notable outcome of the study is the students' expressed interest in extending the use of visuo-haptic simulators beyond Boyle's Law. Participants suggested potential applications in chemistry and other areas of physics where abstract or counterintuitive concepts pose challenges to understanding. This feedback underscores the approach's versatility and its potential to support learning across disciplines. While the present study did not evaluate the educational impact or learning gains, students perceived the simulator as a valuable complement to classroom instruction, which could facilitate knowledge exploration and conceptual visualization. Extending visuo-haptic simulations across scientific domains could promote a broader pedagogical shift toward experiential, embodied learning in science.

5.4 Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the study employed a convenience sample limited to a single institution and a modest cohort (n = 39), primarily determined by laboratory capacity and equipment availability. Consequently, the findings may not generalize to larger or more diverse populations. Second, two types of haptic devices (Novint Falcon and Geomagic Touch) were used. Despite standard calibration, subtle differences in mechanical response could have influenced tactile perception, introducing a potential confounding variable. Future research should employ a uniform hardware setup or statistically control for device type to ensure consistency. Third, qualitative interviews involved purposive sampling, which may have introduced selection bias toward more communicative participants. Finally, the evaluation focused on satisfaction, motivation, and perceived usefulness rather than measured learning outcomes. Subsequent studies should include pre- and post-test designs or control groups to assess actual learning gains and retention. They should use mixed-method triangulation with larger, more diverse samples to strengthen validity.

5.5 Broader implications

The favorable reception of the visuo-haptic simulator suggests that integrating multi-sensory experiences into science education can help bridge the gap between abstract theory and tangible experience. As educational contexts increasingly adopt digital tools, interactive and embodied technologies have the potential to enrich students' engagement with scientific concepts. Moving forward, interdisciplinary collaboration among educators, designers, and engineers will be essential to refine visuo-haptic tools, integrate instructional scaffolds, and expand the range of scientific phenomena that can be represented haptically. With continued development and empirical evaluation, such tools hold promise for enhancing motivation and supporting more meaningful, experiential approaches to science learning.

6 Conclusions

This study explored the potential of a visuo-haptic simulator to enhance students' engagement and understanding of Boyle's Law. By integrating tactile and visual feedback, the simulator provided an interactive environment that encouraged intuitive exploration of the pressure-volume relationship. Rather than assessing learning outcomes directly, the study focused on students' perceptions of satisfaction, usability, and the simulator's perceived value in supporting classroom learning. Survey and interview results indicated high satisfaction in dimensions such as accuracy, ease of use, and responsiveness, underscoring the simulator's effectiveness as a motivational and experiential learning tool.

Feedback also revealed areas for refinement, particularly simplifying the graphical interface and providing a guided tutorial for first-time users. Participants expressed interest in applying visuo-haptic simulators to other topics, suggesting their potential for broader adoption across STEM disciplines.

Future research should focus on measuring learning outcomes and assessing long-term effects. Studies involving larger and more diverse participant groups, ideally in authentic classroom settings, would enable stronger comparisons between visuo-haptic and traditional teaching methods. Incorporating pre- and post-test assessments, transfer-of-knowledge evaluations, and control groups will provide deeper insights into how embodied, multi-sensory interaction supports conceptual understanding. Expanding hardware availability and ensuring consistent device performance will also be necessary for scaling to classroom-level deployment.

Advancing visuo-haptic learning will require interdisciplinary collaboration among educators, designers, and engineers. Continued refinement of interface design, pedagogical scaffolding, and content alignment will help ensure the effective integration of this approach into STEM curricula. While this study focused on students' perceptions and motivational responses, its findings highlight the potential of visuo-haptic tools as engaging and pedagogically supportive resources for experiential science learning.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it was deemed “research without risk,” and the research intervention poses a risk comparable to that of a standard classroom environment. Moreover, because the visuo-haptic simulator was not invasive, the rights of the experimental students were respected in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

SM-I: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software. OL-F: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Visualization. LB-G: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Formal analysis, Supervision. DaiE-C: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Resources, Methodology. DavE-C: Investigation, Software, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was funded by the Fondo Fomento a la Investigación 2024 Grant (UP-CI-2024-MX-22-ING) of Universidad Panamericana.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Vicerrectoría General de Investigación, the Engineering Faculty, the NexEd Hub Research Group, and the Computing Department of Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used an AI tool to improve the grammar, style, and clarity of some sentences and paragraphs after initial human drafting. The author(s) verified all output for factual accuracy and scientific integrity, and the model was not used to generate paragraphs, summaries, display charts or tables, or analyze or interpret data. The model used was ChatGPT, based on GPT-5, the vendor is OpenAI, over the web app (chat.openai.com).

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AbrahamsonD.NathanM. J.Williams-PierceC.WalkingtonC.OttmarE. R.SotoH.et al. (2020). The future of embodied design for mathematics teaching and learning. Front. Educ. 5:147. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00147

2

AcevedoP.MaganaA. J.WalshY.WillH.BenesB.MousasC.et al. (2024). Embodied immersive virtual reality to enhance the conceptual understanding of charged particles: a qualitative study. Comput. Educ. X Real. 5:100075. doi: 10.1016/j.cexr.2024.100075

3

BenesB.MaganaA. J.Gonzalez-NucamendiA.García-CastelánR. M. G.Robledo-RellaV.Escobar-CastillejosD.et al. (2024). Enhancing buoyant force learning through a visuo-haptic environment: a case study. Front. Robot. AI11:1276027. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2024.1276027

4

BrayA.OldhamE.TangneyB. (2015). “Technology-mediated realistic mathematics education and the bridge21 model: a teaching experiment,” in Proceedings of the Ninth Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, Proceedings of the Ninth Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, eds. K. Krainer, and N. Vondrová (Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Education and ERME), 2487–2493.

5

BrownK.LarionovaV.StepanovaN.LallyV. (2019). Re-imagining the pedagogical paradigm within a technology mediated learning environment. Open Educ. Stud. 1, 138–145. doi: 10.1515/edu-2019-0009

6

BuonocoreS.MassaF.GironimoG. (2023). “Does the embodiment influence the success of visuo-haptic learning?” in Application of Emerging Technologies. AHFE (2023) International Conference, Volume 115 of AHFE Open Access, eds. T. Ahram, and W. Karwowski (San Francisco, CA: sAHFE International), 1–11. doi: 10.54941/ahfe1004350

7

ChiangY.-C.LiuS.-C. (2023). The effects of extended reality technologies in stem education on students' learning response and performance. J. Baltic Sci. Educ. 22, 568–578. doi: 10.33225/jbse/23.22.568

8

CoxM. J.LoucaC.BarberS.Haywood-HullJ.HallisseyB.WithersD.et al. (2025). “Virtual haptic simulators: diversifying the technologies to enhance teaching and learning in higher education,” in Digitally Transformed Education: Are We There Yet? Eds. M. Leahy, and C. Reffay (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 100–110. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-88744-4_10

9

DollW. J.TorkzadehG. (1988). The measurement of end-user computing satisfaction. MIS Q. 12, 259–274. doi: 10.2307/248851

10

El-MounayriH. A.RogersC.FernandezE.SatterwhiteJ. C. (2016). “Assessment of stem e-learning in an immersive virtual reality (VR) environment,” in Proceedings of the 2016 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition (New Orleans, LA), 1–9.

11

EnyedyN.DanishJ.DelacruzG.KumarM.GentileS. (2011). “Play and augmented reality in learning physics: the spases project,” in Connecting Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning to Policy and Practice: CSCL2011 Conference Proceedings. Volume I–Long Papers, eds. H. Spada, G. Stahl, N. Miyake, and N. Law (Hong Kong: International Society of the Learning Sciences), 216–223.

12

Escobar-CastillejosD.NoguezJ.Cárdenas-OvandoR. A.NeriL.Gonzalez-NucamendiA.Robledo-RellaV.et al. (2020). Using game engines for visuo-haptic learning simulations. Appl. Sci. 10:4553. doi: 10.3390/app10134553

13

FarinaM. (2021). Embodied cognition: dimensions, domains and applications. Adapt. Behav. 29, 73–88. doi: 10.1177/1059712320912963

14

FisherR.PerényiA.BirdthistleN. (2021). The positive relationship between flipped and blended learning and student engagement, performance and satisfaction. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 22, 97–113. doi: 10.1177/1469787418801702

15

FouadM.MansourT.NabilT. (2023). Use of haptic devices in education: a review. Suez Canal Eng. Energy Environ. Sci. 1, 18–22. doi: 10.21608/sceee.2023.279487

16

Garcia-CastelanR.González-NucamendiA.Neri-VitelaL.Robledo-RellaV.NoguezJ. (2024). “Chatgpt hand in hand with a visuo-haptic simulator for a block on an inclined in an introductory engineering physics course,” in ICERI2024 Proceedings, 17th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (Palma: IATED), 1783–1790. doi: 10.21125/iceri.2024.0517

17

HaleemA.JavaidM.QadriM. A.SumanR. (2022). Understanding the role of digital technologies in education: a review. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 3, 275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.susoc.2022.05.004

18

Hamza-LupF. G.GoldbachI. R. (2021). Multimodal, visuo-haptic games for abstract theory instruction: grabbing charged particles. J. Multimodal User Interfaces15, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12193-020-00327-x

19

HanI.BlackJ. B. (2011). Incorporating haptic feedback in simulation for learning physics. Comput. Educ. 57, 2281–2290. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.06.012

20

Hernández-de MenéndezM.Vallejo GuevaraA.Tudón MartínezJ. C.Hernández AlcántaraD.Morales-MenendezR. (2019). Active learning in engineering education. a review of fundamentals, best practices and experiences. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 13, 909–922. doi: 10.1007/s12008-019-00557-8

21

Johnson-GlenbergM. C.BartolomeaH.KalinaE. (2021). Platform is not destiny: embodied learning effects comparing 2d desktop to 3d virtual reality stem experiences. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 37, 1263–1284. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12567

22

KigerM. E.VarpioL. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

23

KontraC.LyonsD. J.FischerS. M.BeilockS. L. (2015). Physical experience enhances science learning. Psychol. Sci. 26, 737–749. doi: 10.1177/0956797615569355

24

LauZ. J.Verdez-SchollerM.-O.TrajanovskaT.JacobW. (2022). Examining learners' engagement and barriers to interaction during synchronous teaching throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Innov. Partnersh. Change8, 1–12.

25

LeeT.WenY.ChanM. Y.AzamA. B.LooiC. K.TaibS.et al. (2024). Investigation of virtual & augmented reality classroom learning environments in university stem education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 32, 2617–2632. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2022.2155838

26

LestariSyafril, S.LatifahS.EngkizarE.DamriD.AsrilZ.et al. (2021). Hybrid learning on problem-solving abiities in physics learning: a literature review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1796:012021. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1796/1/012021

27

LiK. C.LamH. (2015). Student engagement in a technology-mediated distance learning course. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 10, 172–191. doi: 10.1504/IJSS.2015.072445

28

LombardiD.ShipleyT. A. (2021). The curious construct of active learning. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest22, 8–43. doi: 10.1177/1529100620973974

29

MaganaA.BalachandranS. (2017). Unpacking students' conceptualizations through haptic feedback. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 33, 513–531. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12198

30

MakranskyG.PetersenG. B.KlingenbergS. (2020). Can an immersive virtual reality simulation increase students' interest and career aspirations in science?Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 2079–2097. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12954

31

MayerS.SchwemmleM. (2023). Teaching university students through technology-mediated experiential learning: educators' perspectives and roles. Comput. Educ207:104923. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104923

32

McAnallyK.WallisG. (2022). Visual-haptic integration, action and embodiment in virtual reality. Psychol. Res. 86, 1847–1857. doi: 10.1007/s00426-021-01613-3

33

McClainL. R.ZimmermanH. T. (2016). Technology-mediated engagement with nature: sensory and social engagement with the outdoors supported through an e-trailguide. Int. J. Sci. Educ. B, 6, 385–399. doi: 10.1080/21548455.2016.1148827

34

MichaelJ. A.ModellH. I. (2003). Active Learning in College and Science Classrooms: A Working Model Helping the Learner to Learn. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. doi: 10.4324/9781410609212

35

Mohd SharifS.BasiranM. F.AmonN. (2021). Innovation in teaching methodology: level of student acceptance of ‘boyles law apparatus' teaching aids in thermodynamics course. ANP J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2, 46–54. doi: 10.53797/anpjssh.v2i1.6.2021

36

MontalboS. M. (2021). es2mart teaching and learning material in chemistry: enhancing spatial skills thru augmented reality technology. Palawan Sci. 13, 14–30. doi: 10.69721/TPS.J.2021.13.1.02

37

NeriL.Robledo-RellaV.NoguezJ.García-CastelánR. M.Gonzalez-NucamendiA. (2023). “Enhanced 3D visuo-haptic simulators to understand the nature of friction forces,” in 2023 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (College Station, TX: IEEE), 1–8. doi: 10.1109/FIE58773.2023.10343372

38

NoguezJ.NeriL.Robledo-RellaV.García-CastelánR. M. G.Gonzalez-NucamendiA.Escobar-CastillejosD.et al. (2021). VIS-HAPT: a methodology proposal to develop visuo-haptic environments in education 4.0. Future Internet13:255. doi: 10.3390/fi13100255

39

NovakM.SchwanS. (2021). Does touching real objects affect learning?Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 637–665. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09551-z

40

OlympiouG.ZachariaZ. C. (2012). Blending physical and virtual manipulatives: an effort to improve students' conceptual understanding through science laboratory experimentation. Sci. Educ. 96, 21–47. doi: 10.1002/sce.20463

41

Owusu-AgyemanY.Larbi-SiawO. (2018). Exploring the factors that enhance student-content interaction in a technology-mediated learning environment. Cogent. Educ. 5:1456780. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2018.1456780

42

QiK.BorlandD.WilliamsN. L.JacksonE.MinogueJ.PeckT. C.et al. (2020). “Augmenting physics education with haptic and visual feedback,” in 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW) (Atlanta, GA: IEEE), 439–443. doi: 10.1109/VRW50115.2020.00093

43

RobillosR. J. (2023). Improving students' speaking performance and communication engagement through technology-mediated pedagogical approach. Int. J. Instr. 16, 551–572. doi: 10.29333/iji.2023.16131a

44

RogersC.El-MounaryiH.WasfyT.SatterwhiteJ. (2018). Assessment of stem e-learning in an immersive virtual reality (VR) environment. ASEE Comput. Educ. J. 8, 1–9.

45

ShuY.HuangT.-C. (2021). Identifying the potential roles of virtual reality and stem in maker education. J. Educ. Res. 114, 108–118. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2021.1887067

46

SokratH.TamaniS.MoutaabbidM.RadidM. (2014). Difficulties of students from the faculty of science with regard to understanding the concepts of chemical thermodynamics. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 116, 368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.223

47

TalafianH.MoyM. K.WoodardM. A.FosterA. N. (2019). Stem identity exploration through an immersive learning environment. J. STEM Educ. Res. 2, 105–127. doi: 10.1007/s41979-019-00018-7

48

TorralbaK. D.DooL. (2020). Active learning strategies to improve progression from knowledge to action. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 46, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2019.09.001

49

WalshY.MaganaA. J. (2023). Learning statics through physical manipulative tools and visuohaptic simulations: the effect of visual and haptic feedback. Electronics12:1659. doi: 10.3390/electronics12071659

50

WalshY.MaganaA. J.FengS. (2020). Investigating students' explanations about friction concepts after interacting with a visuohaptic simulation with two different sequenced approaches. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 29, 443–458. doi: 10.1007/s10956-020-09829-5

51

WebbM.TraceyM.HarwinW.TokatliO.HwangF.JohnsonR.et al. (2022). Haptic-enabled collaborative learning in virtual reality for schools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 937–960. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10639-4

52

YangT.-H.KimJ. R.JinH.GilH.KooJ.-H.KimH. J.et al. (2021). Recent advances and opportunities of active materials for haptic technologies in virtual and augmented reality. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31:2008831. doi: 10.1002/adfm.202170292

53

YavaniZ. (2023). Online technology-mediated classroom: how technology and pedagogy are mutually executed. Indones. J. Cyber Educ. 1, 49–50.

54

YukselT.WalshY.KrsV.BenesB.NgambekiI. B.BergerE. J.et al. (2017). “Exploration of affordances of visuo-haptic simulations to learn the concept of friction,” in 2017 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (Indianapolis, IN: IEEE), 1–9. doi: 10.1109/FIE.2017.8190471

55

ZhaoJ. LaFemina, P.CarrJ.SajjadiP.WallgrünJ. O.KlippelA. (2020). “Learning in the field: comparison of desktop, immersive virtual reality, and actual field trips for place-based stem education,” in 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR) (Atlanta, GA: IEEE), 893–902. doi: 10.1109/VR46266.2020.00012

Summary

Keywords

visuo-haptic simulators, embodied cognition, active learning, student engagement, ideal gases, physics education, educational innovation, higher education

Citation

Montes-Isunza S, Lozada-Flores O, Berumen-Glinz LA, Escobar-Castillejos D and Escobar-Castillejos D (2026) Integrating visuo-haptic simulators for active learning to explore the concept of Boyle's Law. Front. Educ. 10:1687152. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1687152

Received

16 August 2025

Revised

07 November 2025

Accepted

30 November 2025

Published

08 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Abusufiyan Shaikh, Anjuman-I-Islam's Kalsekar Technical Campus, India

Reviewed by

Christos Mousas, Purdue University, United States

Wright Jacob, King's College London, United Kingdom

Shirin Hajahmadi, University of Bologna, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Montes-Isunza, Lozada-Flores, Berumen-Glinz, Escobar-Castillejos and Escobar-Castillejos.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Escobar-Castillejos, descobarc@up.edu.mx

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.