Abstract

Despite growing interest in educational digital leadership and supervision, validated instruments measuring supervisors’ digital competencies for their performance excellence (SDC-PE) remain scarce, particularly in developing nations. This study developed and validated the SDC-PE scale through stakeholder perceptions of 318 principals and teachers across 78 senior high schools in 17 districts of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. The SDC-PE integrates classical supervision theories (Cogan, Goldhammer, Glickman) with ISTE Standards and DigCompEdu 2.2, yielding four dimensions: Strategic digital leadership (SDL), digital culture promotion (DGC), teacher digital development (TDD), and digital learning facilitation (DGL). Confirmatory composite analysis (CCA) using PLS-SEM demonstrated excellent psychometric properties: factor loadings (0.839–0.936), composite reliability (0.933–0.955), AVE (0.776–0.811), and model fit indices exceeding thresholds (CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.960, RMSEA = 0.072). Discriminant validity was confirmed through Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios (<0.85). The SDC-PE provides educational institutions with an empirically validated assessment tool for evaluating supervisor digital competencies, designing targeted professional development.

Introduction

The digital revolution has transformed education globally, with technology enabling flexible, accessible learning that accelerates progress toward SDG 4 (UNESCO, 2025). As 67.5% of the global population is now online (Shetty, 2025), educational leaders must strategically integrate digital tools while cultivating innovative learning environments (McCarthy et al., 2023). Educational supervisors—professionals who bridge policy implementation and classroom practice—play a crucial role in this transformation. Their evolving responsibilities encompass both academic and technological change management while ensuring educational quality and equity (Badawy et al., 2024; Rasdiana et al., 2024). The success of digital integration depends significantly on supervisors’ digital competencies (Atis et al., 2024; Wallace et al., 2023).

Educational supervision provides systematic professional support aimed at improving teaching quality through planning, observation, analysis, and reflective dialogue (Glickman et al., 2013; Goldhammer, 1969). Supervisors function as instructional leaders, professional developers, evaluators, and organizational catalysts, adapting approaches to teachers’ developmental needs (Muttaqin et al., 2023). However, digital transformation has fundamentally altered supervision from face-to-face interactions to hybrid models incorporating virtual observations, digital portfolios, and technology-mediated professional development. Supervisors must now act as digital transformation leaders who guide meaningful technology adoption (Mishra and Koehler, 2006).

Existing research on digital competencies in K-12 education has focused primarily on school principals rather than educational supervisors as government employees. Studies from Malaysia (Ghavifekr and Wong, 2022; Nawawi et al., 2023), Philippines (Hero, 2020), USA (Gonzales, 2020; Sheninger, 2019), Turkey (Karakose et al., 2021, 2024), and other nations examine principals’ digital leadership and its effects on school culture, teacher competencies, and technology integration. This principal-centric focus leaves supervisor-specific digital competencies, particularly for government personnel under Ministry of Education authority—largely unexplored.

In Indonesia, Regulation 4831/B/HK.03.01/2023 emphasizes supervisors’ roles in implementing Merdeka Belajar policies, yet explicit digital competency frameworks for supervisors remain absent. Previous Indonesian studies examined principals’ digital leadership effects on school culture (Rasdiana et al., 2024), e-leadership during COVID-19 (Purnomo et al., 2023; Sunu, 2022), and digital innovation’s impact on school performance (Suharyati et al., 2024). While valuable, these studies did not directly examine required digital competencies for educational supervisors operating across multiple schools.

This study addresses these gaps by proposing the supervisors’ digital competencies scale for performance excellence (SDC-PE). The framework synthesizes classical supervision theories (Cogan, 1972; Glickman, 1996; Goldhammer, 1969; Taylor, 1975) with contemporary digital competency standards from ISTE (2024) and DigCompEdu 2.2 (Vuorikari et al., 2022). The SDC-PE comprises four empirically-grounded dimensions adapted for Indonesian educational supervisors, including strategic digital leadership (SDL), encompassing strategic planning, policy implementation, and technology program facilitation; digital culture promotion (DGC), encompassing digital governance, safety protocols, and literacy promotion across stakeholders; teacher digital development (TDD), consist of systematic capacity-building through training, modeling, and peer collaboration; and digital learning facilitation (DGL), consisted of curriculum integration of digital skills, continuous learning, and future-ready competency development. This framework operates across individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels, with supervisors serving as multi-level change agents. It acknowledges Indonesia’s unique context, including varied technological infrastructure, collaborative cultural values (gotong royong), and Merdeka Belajar policy requirements.

This research significantly contributes to educational supervision literature by: (1) developing a validated supervisor-specific digital competency framework that bridges classical supervision with contemporary digital standards; (2) providing institutions with an empirically-tested assessment tool; (3) supporting policymakers in developing explicit digital competency standards aligned with Law 4831/B/HK.03.01/2023; and (4) establishing foundations for longitudinal impact studies, cross-cultural validation, and intervention effectiveness research in digital educational supervision.

Literature review

Educational supervision and supervisor in the Indonesian context

Supervision in education is a research-based field that supports educators to improve teaching and learning effectiveness, enhance school quality, and promote professional growth (Asdhiani et al., 2020). Teachers receive continuous professional development through supervision conducted by supervisors who follow operational guidance provided by specific models, like the “grow me please” by leveraging their influence to effect positive change (He et al., 2024; Kurniady and Komariah, 2019). It is a process where educators are guided, coached, and supported systematically by supervisors to improve their professional capabilities and performance for student learning effectiveness (Gong et al., 2025; Lorensius et al., 2022). Consequently, a supervisor must actively engage with teachers, observe implemented teaching methods, hold conference meetings, and provide evaluation reports on findings while aligning them to governmental and educational policies as part of this systematic process (Mensah and Boakye-Yiadom, 2019; Prasongmanee et al., 2021).

According to law number 4831/B/HK.03.01/2023 supervisor is a Civil Servant designated by an authorized official with the full responsibility and authority to oversee and assist in enhancing the quality of education at educational institutions. They are working at various levels of the education system, from district education supervisors overseeing schools at the local level, provincial supervisors guiding district supervisors and schools within their jurisdiction, to school-based supervisors focusing on internal school systems to assist teachers and school administrators in implementing educational standards. In this study, we aim to examine district and provincial supervisors and explore the necessary competencies they must possess in the digital age. According to Article 3, supervisors must supervise by following the principle of professional, planned, gradual, collaborative, asymmetric, equitable, and evaluation-based approaches (Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, 2023). Supervisors support school principals and teachers by guiding program planning, curriculum development, implementation strategies, performance evaluation, community building, and educational transformation through data-driven and student-centered approaches (Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, 2023). Essentially, effective communication and collaboration between supervisors and school stakeholders, including principals and educators, are crucial for the success of monitoring and evaluation (Yani et al., 2024).

Educational supervision in the digital age

Traditional educational supervision models, such as the directive supervision model (Taylor, 1975), differentiated model (Glickman et al., 2013), and a collaborative model (Cogan, 1972; Goldhammer, 1969) have been fundamental in shaping the role of the supervisor. However, as digital tools become central to teaching and learning, supervisors are now required to adopt new models that integrate technology and leadership (McCarthy et al., 2023; Tulowitzki et al., 2022). Therefore, the shift from managerial to digital leadership has become a central theme in recent educational leadership frameworks (Atis et al., 2024).

Studies show that many educational supervisors still struggle with integrating technology into their supervision practices. According to Affan (2024), while ISTE Standards for Educational Leaders (ISTE, 2024) emphasize the importance of modeling digital leadership, leaders and/or supervisors are often underprepared to take on these roles due to a lack of training, systemic challenges, and limited digital resources. Esplin et al. (2018) has been previously argued that the digital leadership competencies, as outlined in ISTE standards, are challenging to apply in practice, especially in developing regions where technological infrastructure is limited. Similarly, the resistance to technological change is a significant barrier to effective digital leadership. This resistance is often driven by inadequate professional development and cultural resistance to adopting new technologies (Affan, 2024; Kilcoyne, 2024) and a lack of strategic leadership and organizational support (Pettersson, 2018).

Despite these challenges, integrating digital leadership is critical. ISTE standard (ISTE, 2024) outlines key competencies for educational leaders to guide principals and teachers in adopting and effectively using technology. The need for supervisors to act as visionaries who empower school principals and educators to leverage technology is an urgent requirement (Sağbaş and Alp Erdoğan, 2022), particularly in contexts like Indonesia (Rasdiana et al., 2024). Digital-based supervision offers several significant opportunities for schools, including the ability to conduct supervision activities anytime and anywhere, which helps improve the competencies of principals and educators, and creates a more supportive and contextual digital learning environment (Danial et al., 2022; Ma’ayis and Haq, 2022). Therefore, supervisors must not only manage digital tools but also lead by example, fostering an environment where digital literacy is embraced at every level of the school system (Prasongmanee et al., 2021; Rukanda and Nurhayati, 2023). This involves the supervisors’ capacity to inspire and direct principals and teachers to work together efficiently, cultivating a familial environment that strengthens teacher commitment and devotion to enhancing the digital learning process (Hidayat, 2021).

Expected supervisor digital competencies

Nowadays, teachers are tasked with preparing students for the 21st century, with digital literacy being a key competency for navigating globalization, which is increasingly characterized by digitalization. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize teachers’ technological professional development (Nguyen and Habók, 2024; Rasdiana et al., 2024). The supervisor, as a mentor, is expected to serve as a bridge to help administrators and teachers with their professional development, enhancing 21st-century competencies by integrating frameworks such as the ISTE Standards for Educational Leaders (ISTE, 2024) and DigCompEdu 2.2 (Vuorikari et al., 2022), which has become a necessity. These frameworks provide clear competencies for educational leaders to guide the digital transformation of schools. This suggests that a supervisor must be proficient in using technology and assist school administrators and teachers in utilizing it to facilitate effective school management, thereby helping students achieve their expected learning outcomes (Althubyani, 2024; Falloon, 2020). This is aligned with Rasdiana et al. (2024) argue that supervisors need to take on more proactive leadership roles, requiring them to move beyond simple administration to become change agents, leading the way in digital pedagogy, data-driven decision-making, and empowering administrators and teachers with digital tools in shaping how technology is implemented across schools. Nevertheless, they need to understand how to make smart choices using data, and learn in ways that fit each teacher and school administrator (Jorge-Vázquez et al., 2021; Sánchez-Cruzado et al., 2021).

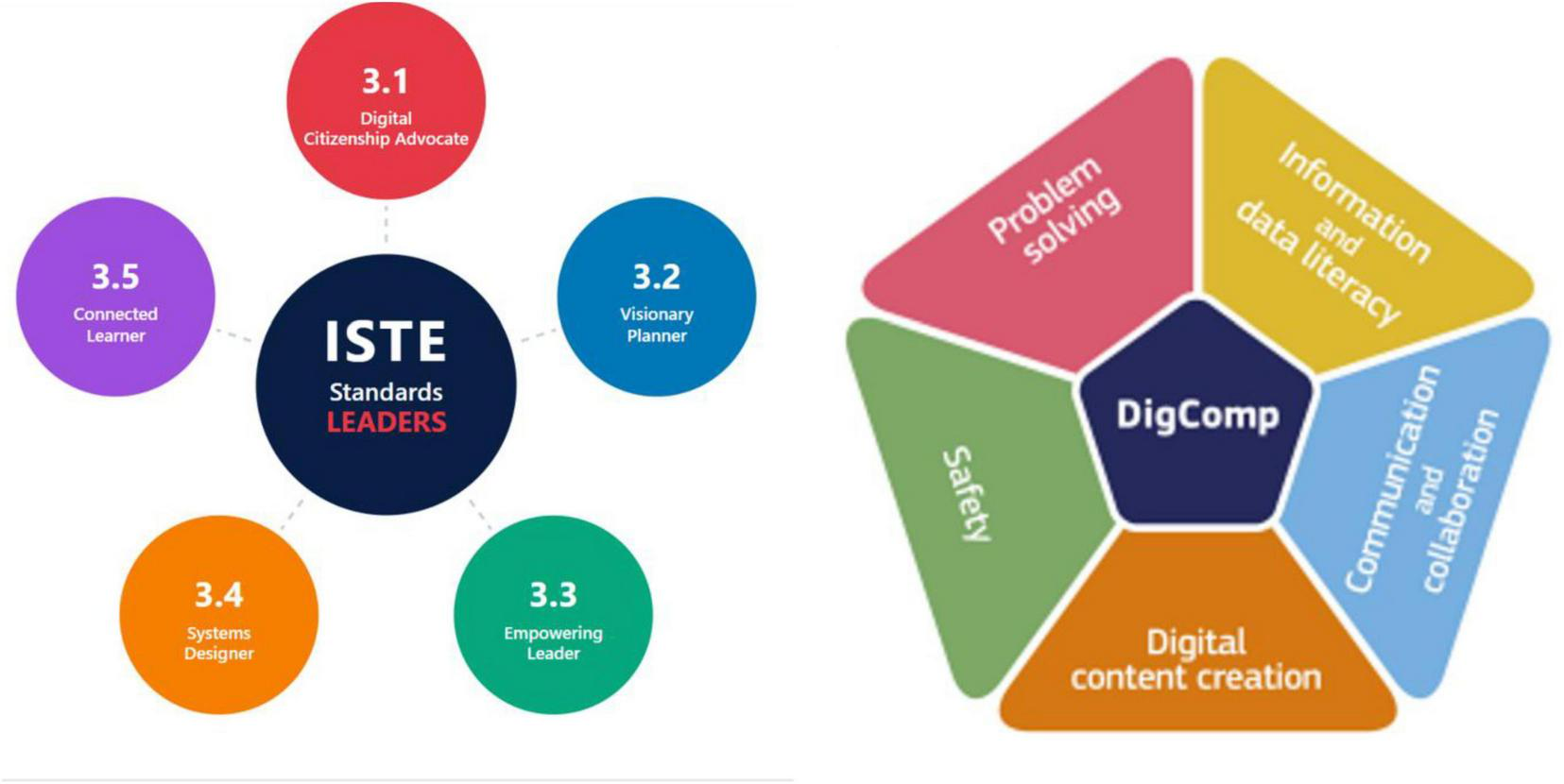

According to ISTE (2024) (see Figure 1 on the left side), leaders are expected to possess several key competencies and roles, including digital citizenship advocate, visionary planner, empowering leader, systems designer, and connected learner. Meanwhile, DigCompEdu 2.2 (Vuorikari et al., 2022) (see Figure 1 on the right side) outlines several indicators, namely information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem-solving. Based on these sources, we classified the expected supervisor digital competencies into four parts: supervisors’ strategic digital leadership (SDL), DGC, TDD, and DGL. As a strategic digital leader, a supervisor serves as a “digital transformation catalyst” who leads, connects, and empowers schools in strategic planning, investment, and implementation of educational technology in accordance with government policies (ISTE, 2024; Prasongmanee et al., 2021; Rasdiana et al., 2024).

FIGURE 1

ISTE standard for leaders (https://iste.org/standards/education-leaders) and DigcompEdu 2.2 framework (https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/oldpage-digcomp/digcomp-framework_en).

Moreover, in digital culture, supervisors establish safe digital practices, model responsible technology use, curate secure educational applications, and promote digital literacy across the entire school community, including administrators, teachers, and students (Hussein et al., 2024; ISTE, 2024). It emphasizes that they are expected to have a clear plan for using technology, helping change how the school works, and encouraging new ideas through digital tools, while being flexible and understanding technology well (Gao and Gao, 2024). This includes supervisor roles in digital safety protocols, models responsible for digital citizenship, curating secure educational applications, and advocating for digital literacy development across all school stakeholders (ISTE, 2024; Vuorikari et al., 2022). Meanwhile, TDD involves supervisors systematically building educators’ technology capacity through direct training, customized professional development, hands-on modeling, peer collaboration facilitation, and digital assessment tool guidance (ISTE, 2024; Vuorikari et al., 2022). In this area, supervisors must help teachers become comfortable with technology, creating safe spaces where administrators and teachers can learn digital skills and use them to make effective school management and learning fun, fair, and personal for each student (Hämäläinen et al., 2021; Navas-Bonilla et al., 2025; Siyam et al., 2025). Finally, digital learning involves supervisors’ roles in ensuring digital skills integration across curricula, maintaining current technology knowledge through continuous learning, helping schools develop future-ready student competencies, and personally modeling lifelong learning in educational technology (Honig and Rainey, 2019; Huet and Casanova, 2022; ISTE, 2024; Norhagen et al., 2024; Vuorikari et al., 2022).

While scholars have explored topics such as digital leadership, teacher development in the digital age, and school culture in the digital era, a notable gap remains in research on the specific competencies that school supervisors need to effectively guide educators and administrators. It’s crucial to understand the digital competencies of supervisors, as these directly impact the quality of supervision and the achievement of school goals. For instance, Prasongmanee et al. (2021) identified three key areas of digital competencies: digital knowledge, digital skills, and self-reliance. However, this focus was more on personal traits and overlooked broader aspects, such as leadership, advocating for digital citizenship, and supporting teacher digital growth. Our study seeks to fill this gap by examining a set of competencies required for effective digital supervision. This study is crucial for enhancing the effectiveness of educational supervision and supporting the broader goals of schools in adapting to the digital era. Ultimately, our findings have the potential to inform policy and practices that empower school leaders to drive innovation and achieve excellence in educational performance.

Materials and methods

Research design

The current study employed a quantitative design, aiming to confirm the instrument development of supervisor digital competencies development, through the testing of factorial, convergent, discriminant validity, and internal consistency (Oetzel et al., 2015). The reason we chose this design, particularly with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), is aligned with our objective in developing a new measurement instrument and exploring complex relationships among variables (Dami et al., 2025; Purnama et al., 2021), and its suitability for prediction-oriented even with smaller sample sizes (Hair et al., 2021). Besides, according to Afthanorhan (2013) it is also one of the most accurate and appropriate for testing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as well as precise in describing the variance of endogenous latent constructs (dependent variables) in this study (Cardella et al., 2021).

This scale measures perceived supervisor competencies based on observable behaviors as reported by principals and teachers who regularly interact with supervisors during supervision activities. This approach is grounded in 360-degree feedback models commonly used in supervision research (Glickman et al., 2013; Muttaqin et al., 2023), where stakeholder perceptions of leadership behaviors provide valid indicators of competency demonstration. Principals and teachers are uniquely positioned to assess supervisor digital competencies as they directly observe these behaviors during supervision sessions, professional development activities, and technology integration initiatives. Their perceptions reflect supervisors’ demonstrated competencies in authentic educational contexts rather than self-reported abilities.

The sample population for this study comprised school principals and teachers in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, who serve as the primary data sources. We utilized a single-time survey design to capture stakeholder perceptions and provide empirical data from a substantial sample, which enabled robust statistical analysis for scale construction and validation (Hair et al., 2021; Muammar et al., 2025). Therefore, a quantitative survey design using PLS-SEM was the appropriate methodological approach for validating the proposed supervisor digital competencies scale.

Participants and procedures

The population of this study included school principals and teachers actively engaged in supervision practices across senior high schools in the state of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Principals and teachers are the individuals who participate in feedback sessions with supervisors to receive guidance on instructional activities. We further applied the convenience non-probability sampling technique across the population due to pragmatic considerations, ease of access, and our proximity based on geographical closeness and the presence of each regency in the state, as well as the specific time frame we set for data collection. However, we ensured that the selected sample across the schools had properly implemented digital supervision activities (Rasdiana et al., 2024). After conducting data collection, a total of 318 valid respondents were gathered for analysis, showing a high response rate of 71% across 17 out of 24 regencies (approximately 78 schools) (see Table 1), which is considered satisfactory for this psychometric or scale development study (Hair et al., 2021).

TABLE 1

| No. | Districts name | Schools total | Total participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tana Toraja | 4 | 28 |

| 2 | Enrekang | 4 | 24 |

| 3 | Takalar | 3 | 18 |

| 4 | Palopo | 7 | 35 |

| 5 | Bulukumba | 4 | 22 |

| 6 | Bantaeng | 3 | 15 |

| 7 | Luwu | 7 | 32 |

| 8 | Gowa | 6 | 30 |

| 9 | Wajo | 8 | 38 |

| 10 | Pinrang | 7 | 31 |

| 11 | Sidrap | 6 | 26 |

| 12 | Pangkep | 5 | 23 |

| 13 | Selayar | 1 | 7 |

| 14 | Bone | 4 | 19 |

| 15 | Makassar | 4 | 21 |

| 16 | Pare-pare | 4 | 17 |

| 17 | Soppeng | 1 | 6 |

| Total | 78 | 318 | |

Participants’ distribution.

For the demographic characteristics, we also recorded sample information, including educational background, length of employment, and the frequency of supervision, to provide a comprehensive profile of the respondents. This enables a deeper understanding of the diverse experiences and perspectives within the digital supervisory landscape, as well as the robustness of the scale’s validation across various educational settings and cultural contexts. Moreover, the diverse and extensive representation we collected in this study will enhance the ecological validity of the findings and ensure the relevance and applicability of the developed scale instrument to the broad spectrum of digital supervisor competencies.

Between August 4 and September 5, 2025, we conducted the main study, following a pilot study at a school with similar characteristics. We first reached out to the Education government authority in South Sulawesi to request permission for data collection across senior high schools and to inform them of the study’s objectives. After receiving permission, we directed the request to the schools, asking principals and teachers to complete the survey across the state, which was distributed via an online Google Form (directed survey link in Indonesia). The questionnaires were designed to collect primary data from principals and teachers involved in digital supervision activities. Ultimately, 17 out of 24 regencies, representing 78 senior high schools, agreed to participate in the research.

Instruments

In developing the Supervisor’s Digital Competencies Scale, we followed a multi-stage process, beginning with an extensive literature review to identify the most credible and widely used sources on digital competencies in educational supervision, particularly those required for supervisors. We employed a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5) to measure the developed items.

The literature review revealed that the most frequently used sources of dimensions and instruments in this field are the ISTE (2024) Standards for Educational Leaders and DigCompEdu 2.2 (Vuorikari et al., 2022), both of which provide relevant guidelines for digital proficiency, especially in educational contexts. While previous studies have often examined either the ISTE Standards or the DigCompEdu framework alone (e.g., Banoğlu et al., 2023; Rasdiana et al., 2024; Zhong, 2017), and although Prasongmanee et al. (2021) proposed an incomplete framework for supervisors’ digital competencies, the present study uniquely synthesizes both frameworks. This approach offers a more holistic and integrated perspective, encompassing behavioral, leadership, digital knowledge, digital skills, and self-reliance dimensions relevant to educational supervisors. Moreover, while the ISTE Standards focus more on strategic leadership and digital transformation, we argue that it is equally important for supervisors to possess practical and pedagogical digital skills, as outlined in DigCompEdu 2.2, to achieve excellence in supervision processes. Consequently, the scale items were designed to capture these theoretical underpinnings while ensuring contextual relevance to the Indonesian educational landscape.

To ensure strong theoretical grounding, each SDC-PE item was systematically mapped onto established supervision theories and international digital competency frameworks. Table 2 presents this integration matrix, showing how classical supervision principles align with components of the ISTE Standards for Educational Leaders and the DigCompEdu framework.

TABLE 2

| SDC-PE item | Classical supervision principle | ISTE standard component | DigCompEdu 2.2 component | Synthesis rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDL1 | Glickman – systematic planning | Visionary planning | Professional engagement | Aligns strategic foresight with collaborative planning |

| SDL2 | Cogan – collaborative cycle | Connected learning | Communication and collaboration | Connects district–school coordination |

| SDL3 | Taylor – systematic management | Systems Design | Information and data literacy | Links resource allocation to evidence-based decisions |

| SDL4 | Goldhammer – directive alignment | Equity and citizenship advocacy | Professional engagement | Ensures policy-based equitable access |

| DGC1 | Glickman – culture building | Equity and citizenship advocacy | Digital safety | Establishes responsible digital norms |

| DGC2 | Cogan – shared responsibility | Equity and citizenship advocacy | Communication and collaboration | Promotes inclusive and equitable digital access |

| DGC3 | Taylor – quality assurance | Systems design | Digital safety | Ensures safe and appropriate educational app selection |

| DGC4 | Goldhammer – developmental practice | Empowering leadership | Digital content creation | Builds digital literacy across stakeholder groups |

| TDD1 | Cogan – clinical cycle | Empowering leadership | Professional engagement | Provides targeted training based on observation |

| TDD2 | Glickman – differentiated support | Empowering leadership | Professional engagement | Tailors digital training to teacher needs |

| TDD3 | Goldhammer – demonstration | Empowering leadership | Digital content creation | Models effective digital instruction practices |

| TDD4 | Cogan – collegial supervision | Connected learning | Communication and collaboration | Facilitates professional learning communities |

| TDD5 | Glickman – evaluation | Systems design | Problem solving | Integrates digital tools into assessment practices |

| DGL1 | Taylor – systematic curriculum | Visionary planning | Digital content creation | Embeds digital skills meaningfully into the curriculum |

| DGL2 | Glickman – self-improvement | Connected learning | Professional engagement | Encourages lifelong professional digital learning |

| DGL3 | Cogan – future orientation | Visionary planning | Problem solving | Prepares students for emerging digital challenges |

| DGL4 | Goldhammer – reflective practice | Connected learning | Professional engagement | Demonstrates ongoing digital growth and reflection |

Theoretical framework integration matrix.

Table 2 illustrates a three-stage synthesis process integrating classical supervision theories with contemporary digital competency frameworks. First, core supervisory functions from classical literature—planning, observation, feedback, evaluation, and professional development—were identified as the structural foundation. Second, components from the ISTE Standards for Education Leaders and DigCompEdu 2.2 were mapped onto these classical functions to generate items that blend traditional supervision roles with modern digital expectations, such as differentiated support, collaborative learning, and systems design. Third, the framework was adapted to Indonesian supervisory practice through alignment with national policy guidelines and expert consultation to ensure cultural relevance and applicability. This process preserved theoretical rigor while contextualizing digital supervision for Indonesian educational settings. Accordingly, Table 3 presents the specific SDC-PE items distributed based on this theoretical mapping.

TABLE 3

| Variable with main source | Dimensions/ indicators | Definition operational | Items of instruments | Supporting references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisors’ digital competencies for performance excellence (SDC-PE) (ISTE, 2024; Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, 2023; Vuorikari et al., 2022) | Strategic digital leadership (SDL) | Supervisors’ ability to lead school digitalization through vision, planning, facilitation, and communication. | 1. The supervisor assists schools in developing long-term plans for technology use (SDL1); 2. The supervisor helps connect schools with the education office in implementing educational technology programs (SDL2); 3. The supervisor provides appropriate recommendations for investments in school computer and internet equipment (SDL3); and 4. The supervisor implements government policies on educational technology in supervised schools (SDL4). |

Affan, 2024; Aldawood et al., 2019; Berkovich and Hassan, 2023; Karakose et al., 2023; McCarthy et al., 2022; Rasdiana et al., 2024; Sheninger, 2019 |

| Digital culture (DGC) | Supervisors’ ability in fostering equity, digital citizenship, and ethical online behavior | 1. The supervisor helps schools establish rules for proper internet and social media use (DGC1); 2. The supervisor promotes the fair use of technology for educational purposes (DGC2); 3. The supervisor selects and recommends safe learning applications for teachers and students (DGC3); and 4. The supervisor teaches digital literacy to teachers, students, and parents (DGC4). |

Hussein et al., 2024; Jorge-Vázquez et al., 2021; Litina and Rubene, 2024; Örtegren, 2022; Rasdiana et al., 2024; Sánchez-Cruzado et al., 2021 | |

| Teachers’ digital development (TDD) | Supervisors’ capacity to coach, empower, and assess teachers in developing digital teaching skills. | 1. The supervisor directly trains teachers on how to use technology for teaching (TDD1); 2. The supervisor organizes digital/computer training according to teachers’ needs at school (TDD2); 3. The supervisor demonstrates how to teach with technology through direct examples (TDD3); 4. The supervisor supports teachers in sharing experiences of teaching with technology (TDD4); and 5. The supervisor guides teachers in using applications for digital tests and assessments (TDD5). |

Gao and Gao, 2024; Hämäläinen et al., 2021; Rasdiana et al., 2024 | |

| Digital learning (DGL) | Supervisors’ capacity to ensure the integration of digital skills into curricula, foster digital literacy, and promote lifelong learning. | 1. The supervisor ensures that school subjects include digital skills instruction (DGL1); 2. The supervisor actively participates in the latest educational technology training (DGL2); 3. The supervisor helps schools prepare students with future-oriented technological skills (DGL3); and 4. The supervisor continuously learns new developments in educational technology (DGL4). |

Honig and Rainey, 2019; Huet and Casanova, 2022; Norhagen et al., 2024; Rasdiana et al., 2024 |

Developed instruments for SDC-PE.

Based on the ISTE (2024) and DigCompEdu 2.2 (Vuorikari et al., 2022) standards, we classified the constructs measured in this study into four categories (refer to Table 3): (a) supervisors’ competencies in strategic digital leadership (SDL), (b) DGC, (c) TDD, and (d) DGL (see Table 2). These constructs were then operationalized into several items, e.g., strategic digital leadership (4 items) was developed on the premise that supervisors serve as strategic and transformational leaders in fostering school digitalization through their roles as visionary planners, system designers, digital facilitators, and communicators (Affan, 2024; Aldawood et al., 2019; Berkovich and Hassan, 2023; Karakose et al., 2023; McCarthy et al., 2022; Rasdiana et al., 2024; Sheninger, 2019). Digital culture (4 items) focuses on supervisors’ responsibilities in promoting collaboration, digital citizenship, equity, and advocacy for responsible online behavior (netiquette). This means that supervisors are expected to ensure collaboration, equitable access to digital resources, responsible use of technology, and positive online engagement across supervised schools (Hussein et al., 2024; Jorge-Vázquez et al., 2021; Litina and Rubene, 2024; Rasdiana et al., 2024; Sánchez-Cruzado et al., 2021). Furthermore, TDD (5 items) covers supervisors’ capacity to act as catalysts for teacher learning by coaching, facilitating professional development, directly supporting teachers in developing digital teaching skills, empowering them, and assessing their progress in digital competence (Gao and Gao, 2024; Hämäläinen et al., 2021; Rasdiana et al., 2024). Finally, digital learning (4 items) reflects supervisors’ ability to ensure that digital skills are integrated into the curriculum, promote digital literacy in teaching and content creation, encourage lifelong learning among principals, teachers, and students, and continuously improve their own digital competence (Ng et al., 2023; Norhagen et al., 2024).

Data analysis

Before main analysis, we conducted pretesting at a similar school to confirm instrument validity and reliability (Lewis et al., 2005). This ensured items reflected theoretical constructs while remaining practical and contextually appropriate (Bell et al., 2023). Afterward, we then analyze the actual collected data subjected to robust statistical analysis by utilizing PLS-SEM for the validity and reliability of the proposed framework model, and assess the developed scale psychometry (Hair et al., 2021; Sarstedt et al., 2021). We employed confirmatory composite analysis (CCA) to validate the measurement model, as it is useful for developing new measures (Hair et al., 2020; Schuberth, 2021). In this process, we employed the measurement technique of a second-order or high-order model with a reflective-reflective type (for post-test) that based on our theoretical and empirical considerations. We conceptualize supervisor digital competence as an underlying latent construct that manifests through the four observed dimensions (SDL, DGC, TDD, DGL) rather than being defined by them. This reflective specification is theoretically justified because digital competence causes supervisors to demonstrate these behaviors across dimensions, meaning that supervisors with high digital competence naturally exhibit strategic leadership, promote digital culture, develop teachers digitally, and facilitate digital learning simultaneously. The dimensions co-occur because they represent different manifestations of the same underlying competency rather than independent components that collectively form competence.

The measurement model consisted of the comprehensive assessment of internal consistency (composite reliability), convergent validity [factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE)], and discriminant validity [Fornell-Larcker criterion and HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio)], ensuring the scale’s robustness and accuracy in measuring supervisors’ digital competencies. Following CCA procedures (Hair et al., 2020; Schuberth, 2021), the measurements of this current study are fulfilled based on the threshold of composite reliability (CR) values above 0.7 = reliable (Hair et al., 2021), listed factor loadings values at 0.6 or higher = significant (Dash and Paul, 2021; Sarstedt et al., 2021), a higher AVE generated value than the cutoff of 0.5 = acceptable (Hair et al., 2021), and for the AVE square root (Fornell-Larcker criterion) must be higher than the correlation between the latent variable and all other variables, shows a validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Finally, model adequacy was assessed using absolute fit indices (χ2/df, RMSEA, GFI, SRMR), incremental fit indices (NFI, TLI, CFI), and parsimonious fit index (AGFI), following recommended threshold (Henseler and Sarstedt, 2013). The goodness-of-fit analysis determined whether the conceptualized dimensions of supervisors’ digital competencies were supported by real-world stakeholder data.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 for preliminary validation and descriptive statistics, and SmartPLS version 3.0 (Hair et al., 2020; Schuberth, 2021) for confirmatory composite analysis using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using SPSS, while all measurement model assessments (convergent validity, discriminant validity, internal consistency, and HTMT ratios) were performed using SmartPLS.

Results

Respondent’s demographic profile

The study’s respondents comprised principals, vice principals, and teachers, with teachers making up the vast majority (73.58%) (see Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Profile | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Position | ||

| Principals | 54 | 16.98 |

| Vice principals | 30 | 9.43 |

| Teachers/educators | 234 | 73.58 |

| Education | 318 | |

| Bachelor | 232 | 72.96 |

| Master | 82 | 25.79 |

| Doctor | 4 | 1.26 |

| Length employment | 318 | |

| 0–5 years | 112 | 35.22 |

| 6–10 years | 78 | 24.53 |

| 11–15 years | 86 | 27.04 |

| >15 years | 42 | 13.21 |

| Supervised frequent | ||

| Each month | 145 | 45.60 |

| Every 2–3 months | 78 | 24.53 |

| Each 6 months (semester) | 29 | 9.12 |

| Each year or more | 1 | 0.31 |

| Accidental | 65 | 20.44 |

Demographic of respondents’ profile.

For educational background, most respondents hold bachelor’s (72.96%), while about a quarter have master’s (25.79%), and only 1.26% hold doctoral degrees. Additionally, respondents reported that their experience level is fairly spread out, with over one-third (35.22%) relatively new to the profession (1–5 years), about half have moderate experience (24.53% with 6–10 years, 27.04% with 11–15 years), and only 13.21% respondents are highly experienced veterans (over 15 years). Finally, the frequency of supervision shows that nearly half of the respondents (45.60%) receive supervision monthly, about a quarter (24.53%) are supervised every 2–3 months, and 20.44% receive unplanned supervision. Given these statistics, respondents are considered to have sufficient perceptions about the supervisors’ digital competencies.

Pretest validation of instruments: SPSS analysis

Before proceeding with the actual analysis, we performed prerequisite pilot testing to ensure that the developed instruments are valid and reliable for further examination.

Table 5 indicates that the instrument has good psychometric properties and is suitable for further examination. This can be shown from factor loadings values above 0.60, indicating the appropriate construct (Hair et al., 2021); communality (ranged from 595 to 0.845 > 0.50), confirming that each item shares sufficient variance with other items in the factor, indicating good construct validity (Kaiser, 1974); KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) (0.908 > 0.50), implying that the data is suitable for further factor analysis (Kaiser, 1970); the variance coefficients all above 50% increased progressively from 71.53% to 100% showing how much of the total variance each factor accounts for when items are added sequentially (Hair et al., 2021); and finally Anti-image Correlations (ranged from 0.822 to 0.989 > 0.50), implying strong sampling adequacy for each item (Hutcheson, 1999). Therefore, the survey is reliable and valid, with all 17 items retained for final analysis, allowing us to move forward confidently with additional samples for the main study.

TABLE 5

| n = 57 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items code | Factor loading (>0.60) | Communality (>0.50) | KMO (>0.50) | Variance (>50%) | Anti-image correlations (>0.50) |

| SDC-PE1 | 0.826 | 0.825 | 0.908 | 71.531 | 0.833a |

| SDC-PE2 | 0.840 | 0.782 | 77.511 | 0.822a | |

| SDC-PE3 | 0.829 | 0.845 | 82.628 | 0.919a | |

| SDC-PE4 | 0.716 | 0.826 | 86.163 | 0.928a | |

| SDC-PE5 | 0.710 | 0.750 | 88.484 | 0.989a | |

| SDC-PE6 | 0.691 | 0.673 | 90.386 | 0.930a | |

| SDC-PE7 | 0.624 | 0.744 | 92.000 | 0.923a | |

| SDC-PE8 | 0.629 | 0.785 | 93.470 | 0.869a | |

| SDC-PE9 | 0.777 | 0.767 | 94.779 | 0.956a | |

| SDC-PE10 | 0.824 | 0.837 | 95.910 | 0.922a | |

| SDC-PE11 | 0.814 | 0.833 | 96.853 | 0.874a | |

| SDC-PE12 | 0.807 | 0.801 | 97.706 | 0.952a | |

| SDC-PE13 | 0.778 | 0.784 | 98.416 | 0.894a | |

| SDC-PE14 | 0.736 | 0.821 | 98.933 | 0.943a | |

| SDC-PE15 | 0.661 | 0.595 | 99.410 | 0.913a | |

| SDC-PE16 | 0.812 | 0.752 | 99.805 | 0.857a | |

| SDC-PE17 | 0.778 | 0.757 | 100.000 | 0.922a | |

Pilot testing SPSS v.25 of the developed instruments.

aThe value shows the suitability of each item for factor analysis.

Perception of respondents

To measure the level of respondents’ perceptions of supervisors’ digital competencies, we analyzed the responses to the developed items using a Likert scale ranging from the lowest score (1) to the highest score (5), corresponding to “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The analysis was then followed by applying the percentage method to measure the relationships between variables.

Based on respondents’ evaluations (see Table 6) of 17 developed items measuring supervisors’ digital competencies across four indicators—strategic digital leadership (SDL), DGC, TDD, and DGL—the average score obtained was 4.09 out of 5.00 with a standard deviation of 0.70. This indicates that supervisors demonstrate high levels of digital competencies, with consistent perceptions among respondents as reflected by the low standard deviation. Furthermore, 45.28% of respondents rated supervisors’ digital competencies as “high,” while 42.25% perceived them as “very high,” with a combined total of 87.73% providing favorable assessments.

TABLE 6

| Category | Range | Mean (M)/SD | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | 1.00–1.8 | 4.09 | 3 | 0.94 |

| Low | 1.81–2.6 | 13 | 4.09 | |

| Moderate | 2.61–3.4 | 23 | 7.23 | |

| High | 3.41–4.2 | 144 | 45.28 | |

| Very high | 4.21–5.0 | 135 | 42.45 | |

| Average | 318 | 100.00 | ||

| Standard deviation | 0.70 | |||

| Total |

Frequency, average, and standard deviation distribution of SDC-PE.

Post-test confirmatory factor analysis: PLS-SEM

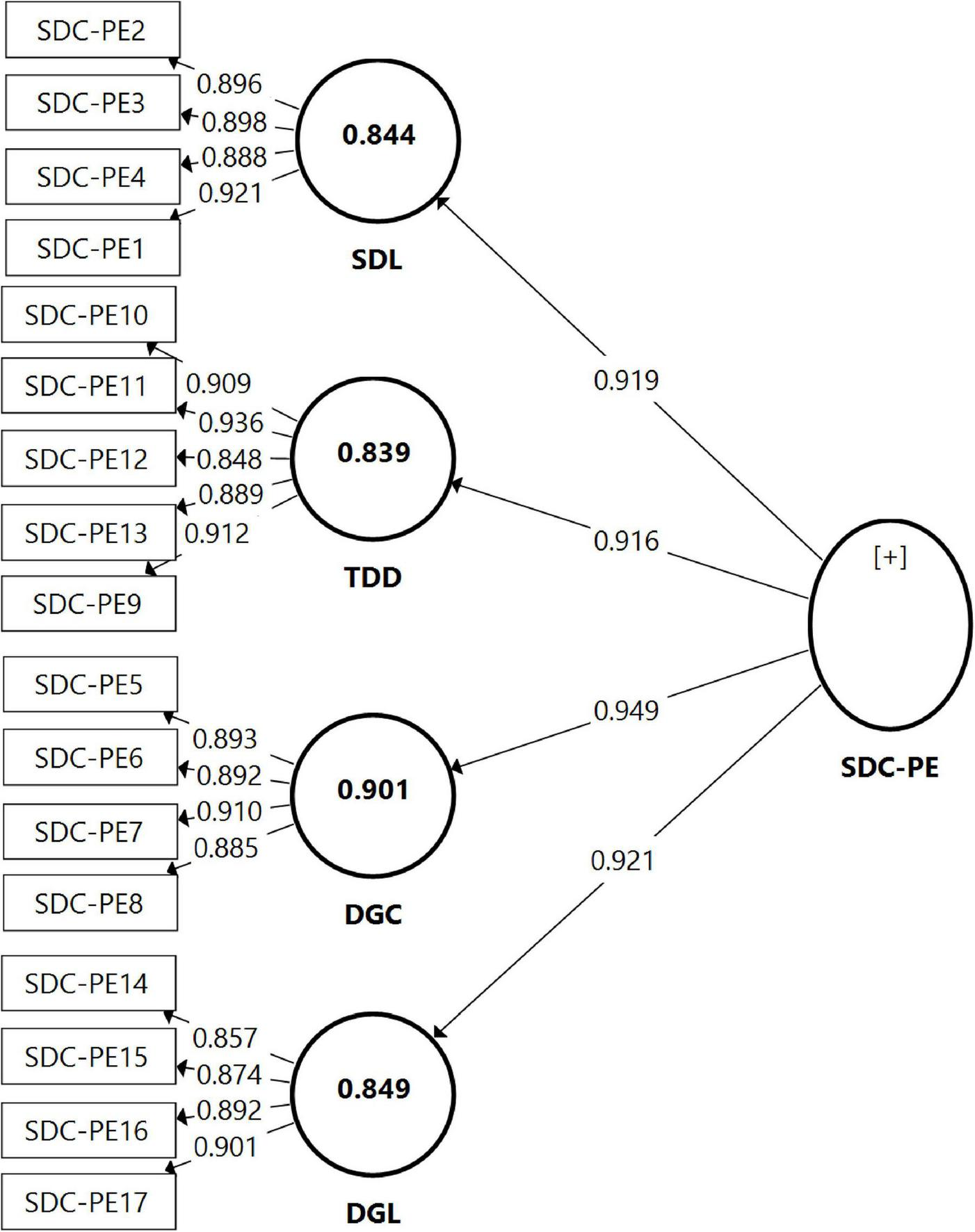

According to the statistical results, the developed scale instrument for measuring supervisors’ digital competencies in this study is valid and reliable, consisting of four constructs: strategic digital leadership, DGC, TDD, and DGL. This is evidenced by the statistical values of goodness-of-fit across eight assessed criteria—Chi-square/df (χ2/df), RMSEA, GFI, SRMR, NFI, TLI, CFI, and AGFI (see Table 7)—all of which met the threshold values, indicating that the established model fits the empirical data. The four measured variables also showed acceptable values for convergent validity and internal consistency (see Figure 2 and Table 8). These results demonstrate that all outer loading indicator values are greater than 0.60; all composite reliability (CR) values exceed the 0.70 threshold; and all average variance extracted (AVE) values are greater than 0.50. Therefore, it can be concluded that both the first- and second-order indicators of supervisors’ digital competencies are valid.

TABLE 7

| Criterion | Index value | Level of acceptance | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit indices | |||

| Chi-square/df (χ2/df) | 2.635 | ≤3.00 | Good fit |

| Root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) | 0.072 | ≤0.08 | Good fit |

| Goodness of fit index (GFI) | 0.908 | ≥0.90 | Good fit |

| Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) | 0.046 | ≤0.08 | Good fit |

| Incremental fit indices | |||

| Normed fit index (NFI) | 0.927 | ≥0.90 | Good fit |

| Tucker Lewis index (TLI) | 0.960 | ≥0.90 | Good fit |

| Comparative fit index (CFI) | 0.968 | ≥0.90 | Good fit |

| Parsimonious fit index | |||

| Adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) | 0.870 | ≥0.80 | Good fit |

Goodness of established model analysis of SDC-PE.

FIGURE 2

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of SDC-PE using PLS-SEM.

TABLE 8

| Construct | Code | Outer loading | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First order | ||||

| SDC-PE1 | SDL1 | 0.921 | 0.942 | 0.801 |

| SDC-PE2 | SDL2 | 0.896 | ||

| SDC-PE3 | SDL3 | 0.898 | ||

| SDC-PE4 | SDL4 | 0.888 | ||

| SDC-PE5 | DGC1 | 0.893 | 0.933 | 0.776 |

| SDC-PE6 | DGC2 | 0.892 | ||

| SDC-PE7 | DGC3 | 0.910 | ||

| SDC-PE8 | DGC4 | 0.885 | ||

| SDC-PE9 | TDD1 | 0.912 | 0.945 | 0.811 |

| SDC-PE10 | TDD2 | 0.909 | ||

| SDC-PE11 | TDD3 | 0.936 | ||

| SDC-PE12 | TDD4 | 0.848 | ||

| SDC-PE13 | TDD5 | 0.889 | ||

| SDC-PE14 | DGL1 | 0.857 | 0.955 | 0.808 |

| SDC-PE15 | DGL2 | 0.874 | ||

| SDC-PE16 | DGL3 | 0.892 | ||

| SDC-PE17 | DGL4 | 0.901 | ||

| Second order | ||||

| SDC-PE | SDL | 0.844 | 0.974 | 0.685 |

| DGC | 0.901 | |||

| TDD | 0.839 | |||

| DGL | 0.849 |

Convergent validity and internal consistency of SDC-PE.

To address potential common method variance concerns arising from single-source, cross-sectional data collection, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003). All 17 items were entered into an unrotated exploratory factor analysis. The results revealed that the first factor accounted for 38.4% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold that would indicate substantial common method bias. This suggests that common method variance is not a critical concern in this dataset.

Table 9 shows the validity test of the AVE square root, demonstrating that the four measured dimensions of supervisors’ digital competencies are higher than the correlations between each dimension and all other dimensions, with values ranging from 0.881 to 0.901. Therefore, there is no issue with discriminant validity, as each measured area represents a distinct construct where each indicator is unique, even though they are related to one another.

TABLE 9

| Variables | DGC | DGL | SDL | TDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGC | 0.895 | |||

| DGL | 0.827 | 0.881 | ||

| SDL | 0.879 | 0.805 | 0.901 | |

| TDD | 0.818 | 0.799 | 0.741 | 0.899 |

Discriminant validity: Fornell-Larcker criterion of SDC-PE.

The bold indicate that each construct has good discriminant validity. The bold value should be higher than the values in the same row and column.

Table 10 further presents the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) demonstrates that all HTMT values range from 0.666 to 0.789, which are well below the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015) and the liberal threshold of 0.90 (Gold et al., 2001). The lowest value of 0.666 between SDL and TDD indicates strong discriminant validity, while the highest value of 0.789 between DGC and SDL, though showing some conceptual overlap, remains within acceptable limits. These results confirm that DGC, DGL, strategic digital leadership (SDL), and TDD are empirically distinct constructs, each capturing unique aspects of supervisor digital competencies.

TABLE 10

| Variables | DGC | DGL | SDL | TDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGC | ||||

| DGL | 0.734 | |||

| SDL | 0.789 | 0.717 | ||

| TDD | 0.733 | 0.712 | 0.666 |

Discriminant validity: HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio) of SDC-PE.

Table 7 demonstrates excellent model fit across all evaluation criteria. The absolute fit indices show the model accurately reproduces the observed data, with Chi-square/df (2.635), RMSEA (0.072), GFI (0.908), and SRMR (0.046) all meeting their respective thresholds. The incremental fit indices (NFI = 0.927, TLI = 0.960, CFI = 0.968) are particularly strong, indicating the model performs substantially better than a baseline model. The parsimonious fit index (AGFI = 0.870) confirms the good fit isn’t due to over-parameterization. These results demonstrate strong structural validity, indicating that the theoretically proposed dimensions of supervisors’ digital competencies for performance excellence are empirically supported by stakeholder perceptions.

Discussion

This study successfully developed and validated the SDC-PE scale, establishing a robust framework for assessing educational supervisors’ digital competencies. The SDC-PE’s second-order factor structure reveals meaningful insights about digital competence manifestation. Digital culture promotion (DGC) exhibited the strongest loading, suggesting that creating supportive digital environments represents the most direct expression of underlying digital competence. This aligns with Indonesian cultural values emphasizing community harmony (gotong royong) and collective responsibility, where supervisors must prioritize establishing safe, inclusive digital spaces before advancing complex initiatives. Conversely, TDD, while strong, showed relatively lower loading, reflecting this dimension’s complexity required both digital expertise and pedagogical knowledge, interpersonal skills, and contextual understanding of individual teacher needs.

Strategic digital leadership, including all four indicators demonstrated strong validity, confirming supervisors must function as transformational digital leaders who systematically plan technology integration, coordinate between districts and schools, allocate resources evidence-based, and implement government policies (Affan, 2024; Karakose and Tülübaş, 2023; Sheninger, 2019). Therefore, education authorities should establish quarterly digital strategic planning sessions where supervisors collaborate with district technology coordinators and school principals to develop 3-year technology roadmaps aligned with national Merdeka Belajar policies. Assessment rubrics should evaluate supervisors’ strategic planning documentation and policy translation effectiveness.

Digital culture promotion further shows strong psychometric properties that confirm supervisors’ critical role in fostering collaborative digital environments encompassing digital citizenship, equitable access, responsible technology use, and stakeholder digital literacy (Litina and Rubene, 2024; Sánchez-Cruzado et al., 2021). The emphasis on comprehensive community digital literacy, extending beyond teachers to students and parents that reflects supervisors’ holistic transformation approach. In this sense, develop district-level digital citizenship frameworks with specific protocols for social media use, online safety, and digital equity is crucial. Supervisors should conduct bi-annual digital culture audits using standardized checklists assessing schools’ digital citizenship practices, safety protocols, and stakeholder literacy levels.

Teacher digital development with the five indicators validate supervisors’ role as systematic capacity builders through direct training, customized professional development, instructional modeling, peer collaboration facilitation, and assessment guidance (Hämäläinen et al., 2021; Rasdiana et al., 2024). This dimension addresses significant variation in teachers’ digital skills while bridging gaps between recognizing technology’s importance and achieving actual implementation competence. Henceforth, it is crucial to implement differentiated professional development pathways based on teacher digital readiness levels (novice, developing, proficient, expert). Supervisors should maintain digital competency portfolios for each supervised school, documenting teacher growth, training participation, and technology integration progress. Besides, supervisors, further required to establish peer mentoring networks where digitally proficient teachers support colleagues under supervisor facilitation.

Digital learning facilitation consisted of four indicators emphasized supervisors’ forward-thinking perspectives, ensuring curricular digital skills integration, maintaining current technology knowledge, preparing students for future technological demands, and modeling lifelong learning (Honig and Rainey, 2019; Norhagen et al., 2024). This dimension positions supervisors as both learners and leaders who engage in self-directed learning and peer collaboration rather than relying solely on formal training. Therefore, it is important to create provincial supervisor learning communities that meet monthly (virtually or in-person) to share emerging technologies, curricular integration strategies, and implementation challenges. In this scenario, supervisors should be able to complete annual digital learning portfolios documenting technology exploration, course completion, or conference participation, as well as establish “innovation schools” where supervisors pilot new digital learning approaches before scaling district-wide.

This study advances previous work through rigorous scale development incorporating content validation (representativeness, importance, clarity), confirmatory analysis demonstrating strong model-data fit, and comprehensive validity assessment (convergent, discriminant, common method bias). The goodness-of-fit analysis confirms the theoretical framework aligns with empirical reality in Indonesian educational contexts, addressing cultural adaptation challenges identified in international digital supervision research (Esplin et al., 2018; Pettersson, 2018).

The SDC-PE framework directly supports implementation of Indonesia’s Merdeka Belajar (Independent Learning) policy as mandated by Law 4831/B/HK.03.01/2023. The policy’s emphasis on flexibility, innovation, and learner-centered approaches requires supervisors who can facilitate rather than prescribe technology integration. Strategic digital leadership enables supervisors to guide schools in developing contextualized digital strategies aligned with Merdeka Belajar principles of curricular autonomy and differentiated instruction. Digital culture promotion fosters the collaborative, safe learning environments essential for student-centered digital learning. Teacher digital development (TDD) empowers educators to become facilitators of independent learning rather than traditional knowledge transmitters, supporting Merdeka Belajar’s shift toward constructivist pedagogies. Digital learning facilitation ensures curricular integration of digital skills necessary for students to become autonomous learners capable of navigating Indonesia’s digital economy. By operationalizing these competencies, the SDC-PE transforms the policy’s abstract goals into measurable supervisor behaviors, enabling education authorities to systematically develop supervisory capacity aligned with national educational transformation objectives.

The current SDC-PE addresses important gaps in existing digital competency assessment frameworks. Prior instruments have primarily focused on school principals within single-institution contexts. Zhong’s (2017) Technology Leadership Assessment (TLA) and Sheninger’s (2019) Digital Leadership Self-Assessment (DLSA) emphasize vision-setting and technology integration for building-level leaders but do not address the multi-school coordination, policy implementation, and cross-institutional facilitation functions central to governmental supervisors. Prasongmanee et al.’s (2021) framework for supervisors in Thailand proposed three competency areas—digital knowledge, skills, and self-reliance, but prioritized individual technical proficiency over leadership dimensions and lacked rigorous psychometric validation through confirmatory factor analysis or comprehensive validity assessment. While the present framework advances this literature by integrating both leadership-oriented competencies (SDL, DGC) and pedagogical support functions (TDD, DGL) within a unified, validated model. The SDC-PE specifically addresses governmental supervisors operating across multiple schools as policy-practice intermediaries, which is a role requiring distinct competencies beyond scaled-up principal leadership. Therefore, current rigorous validation through PLS-SEM demonstrates excellent psychometric properties across all assessed criteria, surpassing validation rigor reported in prior supervisor competency research. Furthermore, unlike previous research focusing on school principals operating within single institutions (AlAjmi, 2022; Rasdiana et al., 2024; Yuting et al., 2022), the SDC-PE addresses government personnel functioning across multiple schools as policy-practice intermediaries. While the framework synthesizes international standards (ISTE, DigCompEdu 2.2) with classical supervision theories, creating a theoretically-grounded yet contextually-relevant instrument for Indonesian educational settings while maintaining potential for cross-cultural adaptation.

The emergence and manifestation of the four SDC-PE dimensions reflect Indonesia’s unique socio-cultural educational context, particularly shaped by gotong royong values and the Merdeka Belajar policy framework, where supervisors prioritize establishing inclusive, collaborative digital environments before advancing individual technical skills, contrasting with Western frameworks emphasizing individual innovation (Sheninger, 2019). This cultural orientation manifests through facilitating teacher learning communities rather than training individuals, operationalizing flexible policy implementation and contextualized technology adaptation, while maintaining the cultural duality of collaborative partnership alongside authoritative expertise that principals and teachers expect from supervisors. Indonesia’s varied technological infrastructure further shapes the framework’s emphasis on digital equity and contextually adaptive training, reflecting supervisors’ understanding of “appropriate technology” adapted to diverse infrastructure realities, highlighting that effective digital supervision competencies are culturally-situated leadership practices rather than culturally-neutral technical skills. This positioning establishes the SDC-PE as the new psychometrically-validated, supervisor-specific digital competency assessment tool suitable for professional development planning and performance evaluation in multi-school governmental contexts.

To facilitate practical application, the SDC-PE yields dimensional scores (mean of items within SDL, DGC, TDD, DGL) and an overall composite score (mean of all 17 items), with interpretive benchmarks guiding professional development decisions: scores above 4.20 indicate exemplary competencies warranting recognition and mentorship roles; scores between 3.40 and 4.20 suggest strong competencies ready for advanced responsibilities with selective development; scores between 2.60 and 3.40 require comprehensive professional development programs; and scores below 2.60 necessitate intensive interventions with structured support. Practitioners should analyze dimensional profiles to identify specific strengths and weaknesses, with unbalanced profiles (dimensional variance exceeding 0.50 points) indicating targeted intervention needs—for example, supervisors strong in TDD but weak in strategic digital leadership require leadership development programs focusing on strategic planning and policy implementation, while those excelling in strategic vision but limited in culture-building need intensive training in DGC and collaborative teacher development strategies. Longitudinal tracking through baseline, progress (6–12 months), and annual assessments enables monitoring growth targets, with realistic expectations of 0.20–0.40 point increases annually and 0.50–0.70 point increases following intensive interventions, while aggregated data at district levels identifies systemic competency gaps, informs strategic resource allocation, enables cross-district benchmarking, and evaluates policy effectiveness, though scores must be interpreted developmentally rather than punitively, considering infrastructural constraints and regional digital maturity while maintaining confidentiality and supplementing high-stakes decisions with direct observation and self-assessment.

While the sample of 318 respondents from 17 districts with 71% response rate is adequate for scale development, several factors limit generalizability. Convenience sampling and restriction to South Sulawesi province may not represent all Indonesian contexts. Regional variations in technological infrastructure, cultural values, and supervision practices across Indonesia’s diverse archipelago require consideration. Focus on senior high schools excludes junior high and elementary contexts where supervisor roles may differ. Validation studies in other provinces, educational levels, and international contexts are necessary before claiming universal applicability. However, theoretical grounding in international frameworks (ISTE, DigCompEdu) suggests potential transferability of empirical examination in the international context.

Theoretical implications

This research integrates classical supervision theories (Glickman, Cogan, Goldhammer, Taylor) with ISTE Standards and DigCompEdu 2.2. The SDC-PE demonstrates how Glickman’s differentiated supervision applies to technology-mediated practices through ISTE’s empowering leadership and DigCompEdu’s professional engagement. Cogan and Goldhammer’s clinical supervision cycles extend to digital environments via ISTE’s visionary planning and DigCompEdu’s communication domains. Taylor’s systematic approaches integrate through ISTE’s digital citizenship advocacy and DigCompEdu’s safety competencies. The framework further extends Mishra and Koehler’s (2006) TPACK to supervisor meta-competencies combining strategic orientation with operational skills. Future research should consider technology acceptance models and organizational change theories (Davis, 1985; Kotter, 2012), as digital supervision adoption requires addressing implementation challenges when integrating strategic leadership with operational competencies. Not all supervisors demonstrate equal readiness for combining classical supervision with contemporary digital competencies, yet willingness often emerges from understanding their evolving role as bridges between traditional excellence and technological demands.

Practical implications

The SDC-PE provides Indonesian educational stakeholders with a validated framework that not only enables systematic, evidence-based supervisor competency evaluations, but also offers concrete implementation strategies across system levels. District and provincial authorities can use SDC-PE results to guide quarterly digital-leadership planning sessions, develop 3-year technology roadmaps aligned with Merdeka Belajar, and incorporate digital leadership rubrics and competency portfolios into supervisor performance evaluations. To strengthen digital culture, authorities can establish district digital-citizenship frameworks, conduct bi-annual culture audits, and recognize supervisors who demonstrate inclusive digital-environment leadership. For teacher development, the SDC-PE supports differentiated digital-readiness pathways, requires supervisors to maintain school-level competency portfolios, and encourages peer-mentoring networks facilitated by supervisors. Digital-learning facilitation can be enhanced through monthly provincial supervisor learning communities, annual digital-learning portfolios, and “innovation schools” that pilot new approaches before district-wide scaling. Aligned with Law 4831/B/HK.03.01/2023, the SDC-PE translates national digital-transformation goals into measurable standards for supervisor certification, performance evaluation, career advancement, and strategic deployment. Education authorities can embed SDC-PE assessments into recruitment and placement processes, ensuring that digitally competent supervisors are assigned to schools requiring transformational leadership. This comprehensive framework provides actionable, context-appropriate guidance for authentic implementation across Indonesian education systems, as well as similar context across the globe.

Limitations and future research

This study acknowledges several limitations that provide direction for future research. The research was conducted exclusively within South Sulawesi, Indonesia, using convenience sampling and a cross-sectional design, which limits generalizability to other contexts and prevents examination of competency development over time. Additionally, relying on principals’ and teachers’ perceptions rather than direct observation may introduce response bias that does not accurately reflect actual supervisor digital behaviors. Future research should address these constraints through longitudinal studies tracking competency development and educational outcomes over time, cross-cultural validation across different Indonesian provinces and international contexts, mixed-methods approaches incorporating direct observation and qualitative interviews, intervention studies testing professional development program effectiveness, and comparative research examining differences between traditional and digitally competent supervisors on organizational outcomes. This study did not include a formal expert panel review for content validity prior to pilot testing. Additionally, while items were systematically derived from established theoretical frameworks (ISTE Standards and DigCompEdu 2.2) and adapted to Indonesian contexts, the absence of structured expert validation represents a methodological limitation. Future validation studies should incorporate formal content validity procedures with expert panels to strengthen the theoretical foundation of the SDC-PE scale. Moreover, research investigating the relationship between supervisor digital competencies and emerging educational technologies, artificial intelligence integration, and post-pandemic educational models would ensure the framework’s continued relevance in rapidly evolving digital educational landscapes while strengthening external validity and providing deeper insights into how digital supervision competencies manifest in authentic educational practice.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed and validated the supervisor’s digital competencies scale for performance excellence (SDC-PE), establishing a framework that addresses the critical gap in digital supervision research within Indonesian educational contexts. The validated instrument comprises four empirically-grounded dimensions—strategic digital leadership, digital culture, teacher digital development, and digital learning—that synthesize classical supervision theories from Cogan, Goldhammer, Glickman, and Taylor with contemporary digital competency frameworks from ISTE Standards and DigCompEdu 2.2, creating the supervisor-specific digital competency model that operates across individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels. The findings reveal that educational stakeholders perceive digital competencies in supervisors as essential rather than supplementary, supporting a paradigm shift from traditional supervision to digital transformation leadership, where supervisors function as multi-level change agents who simultaneously serve as strategic visionaries, cultural promoters, professional developers, and continuous learners. Practically, the SDC-PE scale provides Indonesian educational institutions with an evidence-based assessment tool for systematic competency evaluation, targeted professional development, and strategic personnel decisions while operationalizing Law 4831/B/HK.03.01/2023 through measurable digital competency standards that directly support Merdeka Belajar policy implementation. By enabling supervisors to function as facilitators of flexible, learner-centered, technology-enhanced education, the SDC-PE framework bridges the gap between national policy aspirations and local educational practice, ensuring that Indonesia’s digital educational transformation advances equitably across diverse regional contexts.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Negeri Makassar. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ArA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. RR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FE: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RN: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely would like to thank Indonesian Education Scholarship (BPI), Center for Higher Education Funding and Assessment (PPAPT), and Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) from the Ministry of Finance Republic Indonesia for granting the scholarship and supporting this research and all the participants involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. AI-based tools were used solely to enhance language clarity, grammar, and readability. All conceptual content, data analysis, and interpretations were developed entirely by the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Affan M. (2024). Requirements for digital leadership implementation in Indonesian.J. Educ. Hum. Sci.33165–186. 10.33193/jeahs.33.2024.464

2

Afthanorhan W. M. (2013). A comparison of partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and covariance based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) for confirmatory factor analysis.Int. J. Eng. Sci. Innov. Technol.2198–205.

3

AlAjmi M. K. (2022). The impact of digital leadership on teachers’ technology integration during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kuwait.Int. J. Educ. Res.112:101928. 10.1016/j.ijer.2022.101928

4

Aldawood H. Alhejaili A. Alabadi M. Alharbi O. Skinner G. (2019). “Integrating digital leadership in an educational supervision context: a critical appraisal,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Applications, (Portugal), 1–7. 10.1109/CEAP.2019.8883484

5

Aldighrir W. M. (2024). Impact of AI ethics on school administrators’ decision-making: The role of sustainable leadership behaviors and diversity management skills.Curr. Psychol.4332451–32469. 10.1007/s12144-024-06862-0

6

Alshammary F. M. Alhalafawy W. S. (2023). Digital platforms and the improvement of learning outcomes: Evidence extracted from meta-analysis.Sustainability15:1305. 10.3390/su15021305

7

Althubyani A. R. (2024). Digital competence of teachers and the factors affecting Their competence level: A nationwide mixed-methods study.Sustainability16:2796. 10.3390/su16072796

8

Anwar S. Saraih U. N. (2024). Digital leadership in the digital era of education: Enhancing knowledge sharing and emotional intelligence.Int. J. Educ. Manag.38, 1581–1611. 10.1108/IJEM-11-2023-0540

9

Asdhiani Y. Saptono A. Komarudin . (2020). Profesional supervision model: Development of clinical supervision instruments for teachers of islamic education through a multi-faceted rasch model.KnE Soc. Sci.2020323–333. 10.18502/kss.v4i14.7890

10

Atis E. Norrmén-Smith J. Cappelle F. Van Ghobashy D. (2024). Leadership in the digital transformation of education: What does it mean in practice?.GBE Transforming Education. Available online at: https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/leadership-digital-transformation-education-what-does-it-mean-practice

11

Avolio B. Kahai S. Dodge G. (2001). E-leadership: Implications for theory, research, and practice.Leadersh. Quart.11615–668. 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00062-X

12

Badawy H. R. I. Al Ali F. M. Khan A. G. Y. Dashti S. H. G. H. Al Katheeri S. A. (2024). “Transforming education through technology and school leadership,” in Cutting-edge innovations in teaching, leadership, technology, and assessment, edsAbdallahA. K.AlkaabiA. M.Al-RiyamiR. (Palmdale: IGI Global Scientific Publishing), 182–194. 10.4018/979-8-3693-0880-6.ch013

13

Banoğlu K. Vanderlinde R. Çetin M. Aesaert K. (2023). Role of school principals’ technology leadership practices in building a learning organization culture in public K-12 schools.J. School Leadersh.3366–91. 10.1177/10526846221134010

14

Bell E. Bryman A. Harley B. (2023). Business research methods.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 10.1093/hebz/9780198869443.001.0001

15

Berkovich I. Hassan T. (2023). Principals’ digital transformational leadership, teachers’ commitment, and school effectiveness.Educ. Inquiry16177–194. 10.1080/20004508.2023.2173705

16

Brown B. Jacobsen M. (2016). Principals’ technology leadership.J. School Leadersh.26811–836. 10.1177/105268461602600504

17

Cardella G. M. Hernández-Sánchez B. R. Sánchez-García J. C. (2021). Development and validation of a scale to evaluate students’ future impact perception related to the coronavirus pandemic (C-19FIPS).PLoS One16:e0260248. 10.1371/journal.pone.0260248

18

Cogan M. L. (1972). Clinical supervision.Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

19

Dami Z. A. Pardede R. J. Ingunau T. M. E. Isu R. J. Sekoni R. P. Lopo F. L. (2025). Development and validation of a servant leadership scale in indonesian christian higher education: Pretest and post-test.Christian High. Educ.2454–82. 10.1080/15363759.2024.2390866

20

Danial A. Mumu M. Nurjamil D. (2022). Model supervisi akademik berbasis digital oleh kepala sekolah dalam meningkatkan profesionalisme guru PAUD.J. FKIP UNMA81514–1521. 10.31949/educatio.v8i4.3922

21

Dash G. Paul J. (2021). CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting.Technol. Forecasting Soc. Change173:121092. 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

22

Davis F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results.Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

23

Esplin N. L. Stewart C. Thurston T. N. (2018). Technology leadership perceptions of utah elementary school principals.J. Res. Technol. Educ.50305–317. 10.1080/15391523.2018.1487351

24

Falloon G. (2020). From digital literacy to digital competence: The teacher digital competency (TDC) framework.Educ. Technol. Res. Dev.682449–2472. 10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4

25

Fornell C. Larcker D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error.J. Mark. Res.1839–50. 10.1177/002224378101800104

26

Gao P. Gao Y. (2024). How does digital leadership foster employee innovative behavior: A cognitive–affective processing system perspective.Behav. Sci.14:362. 10.3390/bs14050362

27

Ghavifekr S. Wong S. Y. (2022). Technology leadership in Malaysian schools: The way forward to education 4.0 – ICT utilization and digital transformation.Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag.131–18. 10.4018/IJABIM.20220701.oa3

28

Glickman C. D. (1996). Supervision as instructional leadership.Arlington, VA: ASCD.

29

Glickman C. D. Gordon S. P. Gordon J. M. R. (2013). The basic guide to supervision and instructional leadership.London: Pearson Education Inc.

30

Gold A. H. Malhotra A. Segars A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst.18, 185–214. 10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

31

Goldhammer R. (1969). Clinical supervision: Special methods for the supervision of teachers.Holt: Rinehart and Winston.

32

Gong W. Xu C. Ye J. (2025). Good or bad visits? An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of supervised college teachers in Central China.Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun.121–10. 10.1057/s41599-025-05655-5

33

Gonzales M. M. (2020). School technology leadership vision and challenges: Perspectives from American school administrators.Int. J. Educ. Manag.34697–708. 10.1108/IJEM-02-2019-0075

34