Abstract

While artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming many sectors, its integration into pre-service teacher education in higher education remains limited. This study investigates the iterative development and effects of a concise, two-session educational intervention designed to foster AI literacy among pre-service physics teachers. Following a design-based research approach, the intervention was implemented in two iterations at the University of Cologne (n = 31 across two cohorts). Structured according to the 5E instructional model, the intervention required students to use generative AI tools as didactic instruments to create lesson plans and reflect on their usage. AI literacy was measured using a validated 30-item test, while attitudes toward AI were assessed via a 4-point Likert survey. Results indicate only small, non-significant increases in overall AI literacy, with selective gains observed in competencies explicitly supported by hands-on activities and targeted scaffolding. However, attitudinal measures demonstrated that even brief interventions can strengthen participants’ openness toward AI and their perceived preparedness to use AI tools in teaching. Additionally, the iterative comparison highlighted format-sensitive effects. These findings suggest that while short design-based interventions can selectively activate elements of AI literacy and foster professional confidence, they are insufficient for broader skill Acquisition. Consequently, more sustained, context-rich engagements are likely required to achieve comprehensive and durable AI literacy development in pre-service teacher education.

1 Introduction

The rapid evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has created both opportunities and challenges across various sectors, including education (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). In recent years, research on AI in education has seen significant growth, with Chen et al. (2020) demonstrating a substantial increase in related publications from 2015 onward. However, despite this growing interest, the practical integration of AI into educational contexts remains in its early stages and requires further empirical investigation (Farrokhnia et al., 2024), especially the impact of AI on higher education (Kuleto et al., 2021).

Educational systems are increasingly focused on addressing diverse learning needs and preparing students for future challenges, moving beyond the transmission of factual knowledge toward the development of comprehensive skill sets (Roll and Wylie, 2016). Within this evolving landscape, the concept of AI literacy has emerged as a critical component of modern education. Long and Magerko (2020) define AI literacy as 17 different competencies enabling effective engagement with AI technologies. It involves a thorough understanding of AI concepts, reflective judgment, and ethical sensitivity, empowering individuals to engage thoughtfully with AI and make responsible choices across education, work and everyday life (Chiu, 2025).

For educators, developing AI literacy has become essential as they navigate the integration of these technologies into their teaching practices. As Zawacki-Richter et al. (2019) note, teachers who possess adequate AI literacy are better positioned to make informed pedagogical choices and guide their students in an increasingly technology-driven world. However, research by Bewersdorff et al. (2023) indicates that learners often display limited technical understanding of AI, evidenced by confusion over basic AI definitions and concepts.

This knowledge gap is particularly concerning in teacher education programs, where future educators are being prepared to teach in classrooms that will increasingly incorporate AI technologies. Research by Zhao et al. (2022) suggests that structured training programs could be an effective way to promote AI literacy among educators, enabling them to better implement technological advancements in educational frameworks. Lee and Perret (2022) found that professional development training on technology use increased teachers’ confidence in teaching AI.

Despite potential benefits of AI integration in education, including personalized feedback, tailored instructional materials, and enhanced data analysis capabilities (Chounta et al., 2022), concerns remain regarding accessibility, equity, and the preservation of critical human elements in the educational process (Padma and Rama, 2022; UNESCO, 2021).

Given these challenges, there is a clear need for targeted educational interventions to support pre-service teachers in developing AI literacy. This study investigates the design and iterative refinement of a concise, two-session AI intervention for pre-service physics teachers, developed within a Design-Based Research framework to address the practical challenge of integrating AI literacy into teacher education. Within the educational intervention, students engage in tasks that involve generative AI tools as part of activities to critically analyze and apply AI in teaching contexts.

The study is guided by two research questions:

How does the iterative design of a two-session AI intervention support the development of AI literacy among pre-service physics teachers? (RQ1).

What are pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards AI in education and how does the intervention influence them? (RQ2).

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Design based research (DBR)

DBR serves as a coherent methodology that links theoretical inquiry with educational practice by examining intervention designs (The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003). This approach aims to develop effective, context-sensitive educational interventions through an iterative process that relies on continuous feedback to improve each successive iteration (van Zyl and Karsten, 2022). The methodology unfolds in systematic phases, progressing from initial problem analysis to prototype development, testing, and evaluation, with ongoing refinement of designs based on empirical evidence (van Zyl and Karsten, 2022). DBR involves designing educational interventions and generating insights about their effectiveness while at the same time promoting positive change in learning environments (Minichiello and Caldwell, 2021).

DBR’s applicability is particularly evident in technological interventions (Anderson and Shattuck, 2012), where it generates innovative practices and principles that can be adapted to diverse contexts (The Design-Based Research Collective, 2003). DBR provides a framework for both reporting the problem and its background as well as presenting and evaluating a tested solution (van Zyl and Karsten, 2022). On the other hand, using DBR to develop a concise intervention can take a long time and participants often differ from each iteration to the next (van Zyl and Karsten, 2022).

2.2 The BSCS instructional model

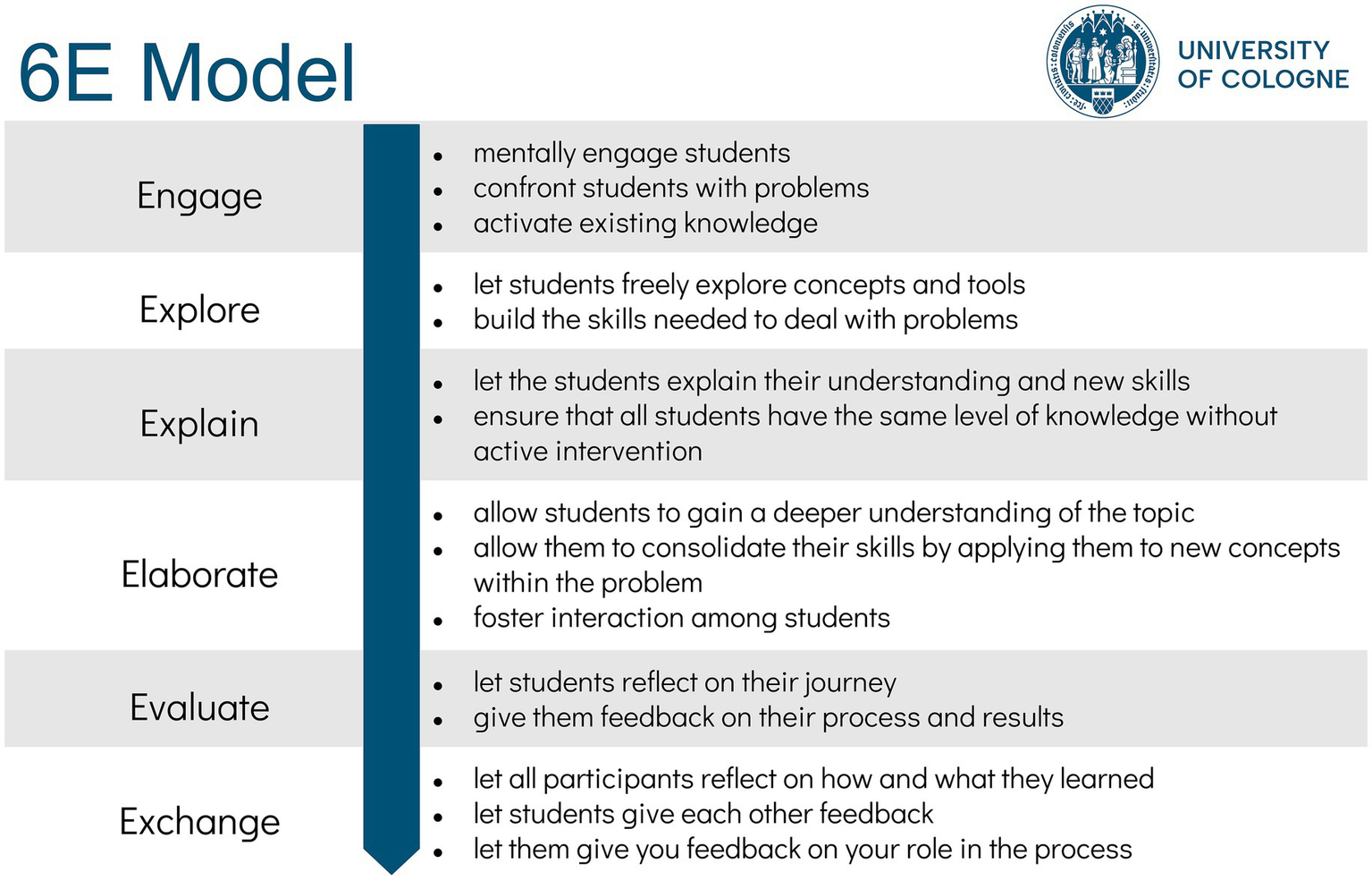

The intervention was designed after the 5E instructional model, which is grounded in constructivist learning theory and consists of the five phases Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, and Evaluate (Bybee, 2009; Bybee et al., 2006; Duran and Duran, 2004). This model provides a structured yet flexible framework (Duran and Duran, 2004) for consolidating knowledge and fostering scientific interest (Bybee et al., 2006). The 5E-framework has been shown to increase teacher confidence (Duran and Duran, 2004) as well but also presents challenges regarding the availability of suitable activities (Namdar and Kucuk, 2018) and time for implementation (Turan, 2021).

Building on this foundation, we adopted an extended version of the model, the 6E-framework, which adds a final Exchange phase to emphasize collaborative reflection. This extension was originally developed and discussed in our earlier work on teacher training in robotics, coding, and artificial intelligence (Henze et al., 2022; Figure 1).

Figure 1

6E model phases and description. Based on the 5E Model from Bybee et al. (2006), extended by Henze et al. (2022).

2.3 Vygotskian principles in educational design

The psychologist Lev Vygotsky conceptualized development as unfolding on two levels. The first represents what an individual learner can accomplish independently, while the second encompasses what the learner can achieve with guidance or support (Leong and Bodrova, 1996). The gap between these two levels is referred to as the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which indicates the range within which learning and development can occur (Pedapati, 2022). This gap bridged through scaffolding provided by teachers or peers (Rigopouli et al., 2025).

In Vygotsky’s view, tools are most effective for learning when they serve multiple purposes rather than being narrowly designed for a single concept (Leong and Bodrova, 1996), therefore AI with its manifold of possibilities could prove to be an effective tool for education. Within Vygotsky’s ZPD, technology-assisted designs, using tools such as an AI chatbot, support learners and teachers in moving beyond their current possibilities (Rigopouli et al., 2025).

2.4 State of AI in education

Recent literature points a steady rise in application of AI in educational context (Mahligawati et al., 2023). Chen et al. (2020) demonstrate a significant increase in research papers on AI in education from 2015 onward, while Roll and Wylie (2016) summarize a growing number of AI developments, refinements and research initiatives. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that the use of AI tools like ChatGPT in education is still at an early stage, highlighting the need for further empirical investigation (Farrokhnia et al., 2024).

While most research on AI in education originates from STEM fields and relies mostly on quantitative methods (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019), recent studies have begun focusing on university contexts regarding ChatGPT-based interventions (Lo, 2023). AI adoption in schools currently happens through individual teachers rather than institutional policies (Vincent-Lancrin and van der Vlies, 2020).

2.5 AI literacy

According to Long and Magerko (2020), AI literacy encompasses the competencies enabling effective engagement with AI technologies both professionally and privately. For educators, developing AI literacy has become essential as they navigate the integration of these technologies into their teaching practices (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). Self-report surveys regarding AI literacy show positive relations between understanding AI, evaluating applications and ethical awareness (Zhao et al., 2022). Hornberger et al. (2023) developed a questionnaire based on Long and Magerko’s (2020) competencies and objectively verifiable knowledge, finding a strong positive relationship between AI literacy and factors such as self-efficacy, interest, and positive attitude toward AI. Research also indicates that AI literacy positively correlates with educational background, suggesting higher levels of education predict greater AI literacy (Zhao et al., 2022). Despite these studies, research shows that learners often display limited technical understanding of AI, evident from confusion over basic AI definitions and concepts (Bewersdorff et al., 2023).

2.6 Teacher education for AI integration

Structured training programs represent a promising approach to promote AI literacy among educators, enabling them to use and implement technological advancements in educational frameworks (Zhao et al., 2022). Such trainings can also help teachers to better estimate their knowledge of AI, as educators who overestimate their knowledge might face difficulties due to misconceptions, while those who underestimate their capabilities may avoid using AI systems despite having adequate skills (Chounta et al., 2022).

Lee and Perret (2022) found that teachers across different backgrounds reported increased confidence in teaching AI after receiving professional training focused on technology utilization. Professional development in this area can enhance educators’ abilities and strengthen students’ learning experiences (Salas-Pilco et al., 2022).

Studies suggest that pre-service teachers can benefit from using ChatGPT in their professional development, showing improved understanding and higher academic achievement (Lo, 2023). However, students lacking knowledge of AI functionality tend to uncritically accept generated responses (Ding et al., 2023), highlighting the need to develop specific AI competencies within teacher education programs (Hornberger et al., 2023).

The integration of AI in educational contexts is viewed positively by teachers, who value it’s potential for providing personalized feedback, creating tailored instructional materials, and analysing student data (Chounta et al., 2022). Generative AI chatbots demonstrate potential for education by supporting the explanation of complex concepts and problem-solving processes (Santos, 2023).

Students similarly find AI-driven tools appealing due to their high interactivity, motivating elements and opportunities for experimentation and simulation (Kuleto et al., 2021). In the context of special needs education, AI additionally offers opportunities for individualized learning (Padma and Rama, 2022).

2.7 Challenges and concerns

Despite these advantages, the incorporation of AI raises important concerns regarding accessibility and equity. Students with diverse barriers, be it disabilities or lack of access, may face significant challenges when using AI-supported tools (Varsik and Vosberg, 2024). Similarly, economically disadvantaged students may face challenges due to restricted access to essential technologies and support (UNESCO, 2021).

Critical reflection remains an important challenge, as research showed that students relying on ChatGPT performed worse in problem-solving tasks compared to peers who relied on search engines (Krupp et al., 2023). ChatGPT users predominantly copied questions and answers directly, indicating limited reflection and critical thinking (Krupp et al., 2023).

A representative study by the Vodafone Foundation (Vodafone Stiftung Deutschland gGmbH, 2023) in Germany found that while respondents generally anticipate significant educational changes through AI, a majority also viewed AI in schools as more of a risk that an opportunity, particularly regarding negative impacts on learning skills and creativity.

Concerns persist about excessive usage of technology, especially among younger learners who may develop dependency and addiction, negatively impacting their physical, emotional and psychological well-being (Padma and Rama, 2022). Additionally, AI currently cannot replace the critical human elements of personal interaction and meaningful teacher-student relationships, which remain integral to effective education (Padma and Rama, 2022). Furthermore, initial enthusiasm associated with AI integration might partly be explained by the novelty effect (Long et al., 2024).

3 Methodology

3.1 Study design

The study followed an experimental pre-post-design to analyze the changes between the pre- and post-test in two consecutive semesters with two different iterations of an intervention to improve AI literacy. In each iteration students completed a two-session intervention, each session lasting 90 min and separated by 1 week (see Description of the intervention for details). Pre- and post-testing allowed to determine whether this short treatment increased objectively measured AI literacy.

Because the attitudes survey was handled differently across the semesters, the design combines cross-sectional and longitudinal elements. In winter 2023/24 only a single survey (n = 14) was taken to establish baseline perceptions of AI after the intervention. In summer 2024 a survey was administered both before and after the intervention (n = 17), allowing attitude change scores parallel to the AI literacy measure. Subsequent sections describe the participant characteristics, instruments and statistical analyses in detail.

3.2 Participants

The study involved pre-service physics teachers enrolled in either the bachelor’s or master’s program of the University of Cologne. Participants represented typical stages of German secondary-school teacher education, which prepares educators to teach students aged approximately ten to eighteen. The pre-service physics teachers who took part in the intervention in winter 2023/2024 were either in the bachelor’s program and in their third to fifth semester, or in the master’s program in their first semester, the participants of the summer 2024 iteration were solely in the bachelor’s program and in their third to fifth semester. Both cohorts were comparable in age distribution and gender composition, reflecting the typical demographic structure of the program. Detailed demographic characteristics of both cohorts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Characteristic | Winter 2023/2024 | Summer 2024 | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 14 (13 matched) | 17 | 31 (30 matched) | ||||

| Gender (m/f) | 7/7 | 10/7 | 17/14 | ||||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 24.6 (7.6) | 23.4 (4.6) | 24 (6.1) | |||

| Median | 22.5 | 22 | 22 | ||||

| Range | 20–50 | 20–40 | 20–50 | ||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Self-assessed AI knowledge | Mean (SD) | 33.4 (23.2) | 48.1 (26.3) | 46.4 (18.6) | 54.4 (24.5) | 41.1 (21.7) | 50.4 (24.7) |

| Median | 20 | 52 | 50 | 57 | 48 | 56.5 | |

| Range | 10–74 | 6–86 | 11–75 | 1–85 | 10–75 | 1–85 | |

Sample description.

3.3 Description of the intervention

The AI intervention was embedded in a mandatory module of the physics teacher education curriculum at the University of Cologne and carried out by members of the research team. This two-session intervention is designed to familiarize pre-service physics teachers with AI tools for classroom use. Following DBR, the intervention was iteratively implemented in two consecutive semesters (winter 2023/24 and summer 2024), with systematic variation in the second iteration due to external constraints. This shift was treated not as a limitation but as a design variation, providing insights into how different instructional formats (in-person vs. self-study) affect learning processes and outcomes.

The structure of both sessions was structured after the 6E instructional framework (Bybee, 2009; Henze et al., 2022), which extends the established 5E model by adding a final Exchange phase for collaborative reflection. The winter semester followed the full 6E cycle, while the summer iteration tested a shortened version without the Exchange phase, thereby allowing DBR-driven comparison of the effects of individual reflection versus collective negotiation.

Table 2 shows the phases and corresponding activities in detail. In the Engage phase, students discussed real-world AI examples and analyzed different AI-generated definitions all written by different generative AI tools—ChatGPT0F1, Perplexity1F2 and Raina2F3, activating prior knowledge and surfacing misconceptions. In the Explore phase, students trained a simple classifier using Google Teachable Machine4, a simple browser-based tool that can be trained in a very short time using simple image or pose classifiers, used as a multipurpose learning tool aligned with Vygotsky’s notion that such tools foster deeper learning (Leong and Bodrova, 1996). The Explain phase was addressed through interactive input on technological foundations, clarifying key concepts and vocabulary.

Table 2

| Session | Phase | Contents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter 23/24 | Summer 24 | ||

| 1 | Engage |

|

|

| Explore |

|

||

| Explain |

|

||

| 2 | Elaborate |

|

|

| Evaluate |

|

|

|

| Exchange |

|

|

|

Oversight of the interventions.

The Elaborate and Evaluate phases provided opportunities for applying and critically assessing AI tools in authentic teacher tasks. Students generated lesson materials on Ohm’s Law with ChatGPT and Perplexity, annotated factual and pedagogical shortcomings, and reflected on AI’s reliability by comparing generated literature lists with real sources. These activities aimed to test and push the limits of each individuals ZPD, as students worked at the boundary of their independent ability, supported by an AI chatbot as well as peer collaboration and scaffolding from the instructors (Rigopouli et al., 2025). The generated lesson plans and working materials were discussed by the students in the winter semester in plenary to illustrate the capabilities and limitations of AI. The purpose was to practice critical evaluation, not the creation of ready-to-teach materials. In the summer semester the evaluation and reflection were made by each student individually based on theoretical knowledge.

Finally, in the Exchange phase of the winter semester, students engaged in a structured debate, deliberately swapping positions to broaden perspectives. This activity embodied Vygotsky’s emphasis on social negotiation (Leong and Bodrova, 1996). In contrast, the summer iteration omitted this phase, relying instead on written reflections. From a DBR perspective, this allowed to examine whether individual evaluation could substitute for social discourse, thereby producing design insights about the non-substitutable role of collaborative Exchange in fostering critical engagement.

3.4 Instruments

To verify the effectiveness of the respective interventions in terms of increasing AI literacy and changing the attitudes of pre-service teachers toward AI, the research instruments described below were used.

3.4.1 AI literacy

The AI literacy test from Hornberger et al. (2023) serves as a multifaceted evaluation tool designed to measure an individual’s understanding and knowledge of AI reliably across various dimensions with a total of 30 items in 14 areas of competence after Long and Magerko (2020). It assesses participants’ abilities to recognize AI applications, distinguish between human and AI interactions, and comprehend the utilization of AI systems in daily life and specialized fields. The test based on objectively verifiable knowledge and measures best at an average level of AI literacy rather than on a very high or low level (Hornberger et al., 2023).

3.4.2 Emotional-motivational variables

The emotional-motivational dimension of the study was assessed using self-designed self-report questionnaires focused on attitudes toward AI in education. The structure and administration of the survey differed between the two semesters. The attitude questionnaires were specifically designed for this study. Its items reflect key themes, such as teachers competencies, perceived opportunities and risks, and ethical aspects.

In the winter semester 2023/2024, an eight-item cross-sectional survey was administered once to capture a baseline snapshot of students’ attitudes toward AI in educational contexts. The statements addressed key themes such as the importance of AI-related teacher competencies, perceived risks and opportunities, and openness to integrating AI in classroom practice. Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Do not agree at all) to 3 (Fully agree). To test whether item scores deviated significantly from a neutral position, values were compared against a midpoint reference value of 1.5. As this was a one-time measurement, the results serve as a contextual reference only and do not allow for measuring change over time.

Although the attitudinal questionnaire used in this study was self-designed and not based on an existing standardized instrument, its focus on pre-service teachers’ perceptions of AI aligns conceptually with recent work by Ishmuradova et al. (2025). Their study developed and validated a four-factor scale capturing attitudes toward the use of generative AI in science education.

The structural change in the test methodology in the summer semester aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention more precisely and to gain deeper insights into potential changes in students’ attitudes. Therefore, the questionnaire was expanded, including all items from the winter semester, and administered in a pre–post design to assess changes in attitudes over the course of the intervention. The revised version included 20 statements and the same four-point Likert scale (0–3) was used.

3.5 Analysis procedure

All data were collected via a digital survey-tool. Completion time was approximately 14 min per survey. The data analysis was carried out in three steps. First, descriptive statistics were calculated separately for each group at pre- and post-test to obtain an overall performance profile. Statistical analysis was performed at the overall test level and the competency level after Hornberger et al. (2023). The pre–post difference scores for each participant and the overall-level were subjected to a Shapiro–Wilk normality test. The resulting p-value is reported as psw. If the normality assumption held, the change was evaluated with a paired-samples t-test, whose p-value is denoted pt. If normality was violated, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied, reported as pw.

4 Results

4.1 Results RQ1

4.1.1 Iteration-wise descriptive summary

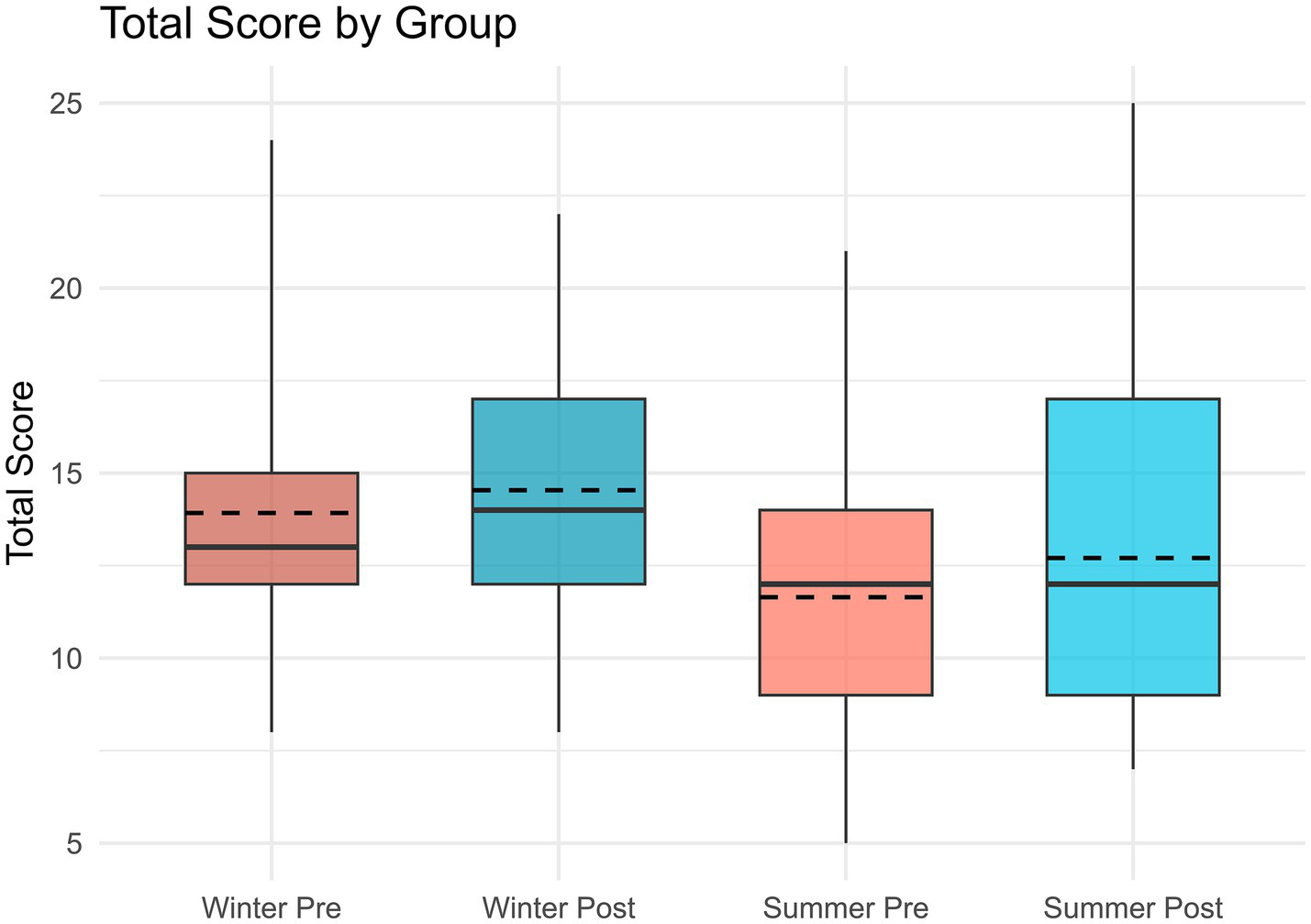

Across both iterations, overall AI literacy scores showed small upward shifts but no substantial changes. In the winter semester, scores ranged from 8 to 24 at pre-test and 8 to 22 at post-test, with the mean increasing slightly from 13.92 (SD 4.68) to 14.54 (SD 3.93) and the median rising from 13 to 14.

In the summer semester, the range broadened from 5 to 21 at pre-test and 7 to 25 at post-test with the mean showing a modest increase from 11.65 (SD 4.46) to 12.71 (SD 5.52) but the median remaining unchanged at 12. Variability in the data remained high in both semesters.

Table 3 summarizes for each of the 16 AI literacy competencies (C01–C17), the pre- and post-test means, medians, and standard deviations in both iterations. The table also shows which items belong to which competency. In the winter semester, competency means ranged between 0.54 and 2.69 (SD 0.00–1.03) at pre-test and 0.54 to 2.54 (SD 0.00–1.05) at post-test. In the summer semester, the corresponding ranges were 0.47 to 2.35 (SD 0.00–1.32) and 0.41 to 2.12 (SD 0.33–1.22).

Table 3

| Competency summarizing items | Item Code | Winter | Summer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| The data is presented in the following form: Mean (SD), Median | |||||

| C01 Recognizing AI | Q1, Q2 | 0.62 (0.65), 1 | 0.54 (0.66), 0 | 0.71 (0.59), 1 | 0.53 (0.51), 1 |

| C02 Understanding Intelligence | Q5, Q6 | 1.54 (0.66), 2 | 1.85 (0.38), 2 | 1.41 (0.71), 2 | 1.18 (0.88), 1 |

| C03 Interdisciplinarity | Q3, Q4 | 0.54 (0.78), 0 | 0.62 (0.77), 0 | 0.59 (0.80), 0 | 1.00 (0.94), 1 |

| C04 General vs. Narrow | Q8, Q9 | 0.85 (0.8), 1 | 1.23 (0.44), 1 | 0.71 (0.69), 1 | 0.88 (0.70), 1 |

| C05 AI’s Strengths & Weaknesses | Q10, Q11 | 0.77 (0.83), 1 | 1.08 (0.76), 1 | 0.76 (0.66), 1 | 0.76 (0.75), 1 |

| C07 Representations | Q12, Q13 | 0.46 (0.52), 0 | 0.54 (0.66), 0 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 | 0.41 (0.62), 0 |

| C08 Decision-Making | Q14, Q15, Q16 | 0.92 (0.76), 1 | 0.92 (0.86), 1 | 0.65 (0.61), 1 | 0.65 (0.79), 0 |

| C09 ML-Steps | Q17, Q18, Q19 | 0.92 (1.12), 1 | 1.00 (0.91), 1 | 0.71 (0.92), 0 | 1.12 (0.93), 1 |

| C10 Human Role in AI | Q20, Q21 | 0.69 (0.63), 1 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.47 (0.72), 0 | 0.53 (0.72), 0 |

| C11 Data Literacy | Q23 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.62 (0.51), 1 | 0.59 (0.51), 1 | 0.65 (0.49), 1 |

| C12 Learning from Data | Q24, Q25 | 1.38 (0.77), 2 | 1.08 (0.76), 1 | 0.71 (0.69), 1 | 1.24 (0.66), 1 |

| C13 Critically Interpreting Data | Q26 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 0.76 (0.44), 1 | 0.76 (0.44), 1 |

| C16 Ethics | Q27–Q31 | 2.69 (1.03), 3 | 2.54 (1.05), 2 | 2.35 (1.32), 2 | 2.12 (1.22), 2 |

| C17 Programmability | Q22 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 0.76 (0.44), 1 | 0.88 (0.33), 1 |

Overview of the descriptive data for both semesters on competency level.

Some competencies demonstrated stability across both semesters, such as C13 Critically Interpreting Data (constant at a mean of 1.0 in winter and 0.76 in summer) and C17 Programmability with stable medians and only little variance. Others showed mixed patterns: C02 Understanding Intelligence increased in winter from mean 1.54 to 1.85 but declined in summer from 1.41 to 1.18, while C12 Learning from Data decreased in winter from mean 1.38 to 1.08 but improved in summer from 0.71 to 1.24. Ethical considerations (C16) remained comparatively high but showed slight decreases from pre- to post-test in both semesters.

Table 4 presents the item-level overview (Q1–Q31). In the winter semester the pre-test means ranged from 0.08 to 1.00 (SD 0.00–0.52) and the post-test means also ranged from 0.08 to 1.00 (SD 0.00–0.5). In the summer semester the pre-test means ranged from 0.12 to 0.82 (SD 0.33–0.51) while the post-test means ranged from 0.06 to 0.88 (SD 0.24–0.51).

Table 4

| Question | Winter | Summer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| The data is presented in the following form: Mean (SD), Median | ||||

| Q1 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.15 (0.38), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 |

| Q2 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.41 (0.51), 0 |

| Q3 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.53 (0.51), 1 |

| Q4 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 |

| Q5 | 0.69 (0.48), 1 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 0.82 (0.39), 1 | 0.65 (0.49), 1 |

| Q6 | 0.85 (0.38), 1 | 0.85 (0.38), 1 | 0.59 (0.51), 1 | 0.53 (0.51), 1 |

| Q8 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.77 (0.44), 1 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.41 (0.51), 0 |

| Q9 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.46 (0.52), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 |

| Q10 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.41 (0.51), 0 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 |

| Q11 | 0.46 (0.52), 0 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.29 (0.47), 0 |

| Q12 | 0.08 (0.28), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 |

| Q13 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.29 (0.47), 0 |

| Q14 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.18 (0.39), 0 |

| Q15 | 0.15 (0.38), 0 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.29 (0.47), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 |

| Q16 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 |

| Q17 | 0.38 (0.48), 0 | 0.08 (0.28), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 |

| Q18 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 | 0.53 (0.51), 1 |

| Q19 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 |

| Q20 | 0.46 (0.52), 0 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.18 (0.39), 0 | 0.35 (0.49), 0 |

| Q21 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.29 (0.49), 0 | 0.18 (0.39), 0 |

| Q22 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 0.76 (0.44), 1 | 0.88 (0.33), 1 |

| Q23 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.62 (0.51), 1 | 0.59 (0.51), 1 | 0.65 (0.49), 1 |

| Q24 | 0.85 (0.38), 1 | 0.62 (0.51), 1 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 | 0.71 (0.47), 1 |

| Q25 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.46 (0.52), 1 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.53 (0.51), 0 |

| Q26 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 1.00 (0.00), 1 | 0.76 (0.44), 1 | 0.76 (0.44), 1 |

| Q27 | 0.38 (0.51), 0 | 0.15 (0.38), 0 | 0.12 (0.33), 0 | 0.06 (0.24), 0 |

| Q28 | 0.46 (0.52), 0 | 0.31 (0.48), 0 | 0.65 (0.49), 1 | 0.65 (0.49), 1 |

| Q29 | 0.92 (0.28), 1 | 0.92 (0.28), 1 | 0.82 (0.39), 1 | 0.71 (0.47), 1 |

| Q30 | 0.23 (0.44), 0 | 0.62 (0.51), 1 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 | 0.47 (0.51), 0 |

| Q31 | 0.69 (0.48), 1 | 0.54 (0.52), 1 | 0.29 (0.47), 0 | 0.24 (0.44), 0 |

Overview of the descriptive data for both semesters on question level.

Robust performance was observed for items such as Q5 (Intelligence of AI), which remained relatively high across both semesters (winter: mean from 0.69 to 1.00; summer mean from 0.82 to 0.65, median stable). Similarly, Q22 (programmability) showed consistent high values in both cohorts. By contrast, items tapping into data literacy and decision-making posed greater challenges: Q12 (knowledge representation) stayed very low in both semesters (mean below 0.23), and Q27 (ethical principles) even declined in summer from a mean of 0.12 to 0.06. Isolated improvements occurred, for example in Q3 (AI systems), which rose slightly in both semesters, and Q30 (risks of AI), which showed a larger pre–post gain in the winter cohort.

4.1.2 Statistical analysis

Inferential tests were conducted to examine whether the observed descriptive tendencies for each of the iterations reached statistical significance. The Shapiro–Wilk tests on the pre–post difference scores confirmed an approximately normal distribution of overall change in both cohorts (p = 0.491 in the winter and p = 0.592 in the summer). Accordingly, paired t-tests were used to evaluate change in total AI literacy score. In both semesters, the mean increase was not statistically significant.

The Shapiro–Wilk tests on competency-level difference scores revealed that only C08 Decision-Making (p = 0.195) met the normality assumption in the summer cohort, all other competencies violated normality. Therefore, a paired t-test was applied for C08 and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for the remaining competencies in each semester.

The statistical analyses shown in Table 5 demonstrate that neither iteration produced significant pre–post gains in total AI literacy scores. In the winter cycle, the overall mean increased slightly but failed to reach statistical significance and a similar pattern emerged in the summer cycle. On the competency level, no significant changes were observed, although individual competencies such as understanding intelligence (C02) and general vs. narrow AI (C04) in the winter semester as well as interdisciplinarity (C03) and learning from data (C12) in the summer semester approached significance in one of the two cycles. At the item level, only Q30 in the winter iteration showed a significant change (p = 0.037).

Table 5

| Level | Winter pw | Summer pw |

|---|---|---|

| Total (t-test) | pt = 0.27461 | pt = 0.29926 |

| C01 | 0.85011 | 0.39295 |

| C02 | 0.07186 | 0.12943 |

| C03 | 0.77283 | 0.06498 |

| C04 | 0.0726 | 0.23304 |

| C05 | 0.12943 | 1 |

| C07 | 0.77283 | 0.77681 |

| C08 | 1 | pt = 1 |

| C09 | 0.78972 | 0.06498 |

| C10 | 0.42371 | 0.77681 |

| C11 | 0.77283 | 0.77283 |

| C12 | 0.24017 | 0.07758 |

| C13 | - | 1 |

| C16 | 0.59407 | 0.34049 |

| C17 | - | 0.48402 |

| Q1 | 0.76559 | 0.12943 |

| Q2 | 1.00000 | 0.76559 |

| Q3 | 0.34578 | 0.23304 |

| Q4 | 1.00000 | 0.07186 |

| Q5 | 0.07186 | 0.23304 |

| Q6 | No Variation | 1.00000 |

| Q8 | 0.14891 | 1.00000 |

| Q9 | 0.42371 | 0.42371 |

| Q10 | 0.23304 | 0.77283 |

| Q11 | 1.00000 | 0.76559 |

| Q12 | 0.34578 | 1.00000 |

| Q13 | 0.76559 | 0.76559 |

| Q14 | 0.34578 | 0.76559 |

| Q15 | 0.42371 | 0.14891 |

| Q16 | 1.00000 | 0.07186 |

| Q17 | 0.14891 | No Variation |

| Q18 | 0.34578 | 0.23304 |

| Q19 | 0.42371 | 0.12943 |

| Q20 | 0.34578 | 0.14891 |

| Q21 | 1.00000 | 0.42371 |

| Q22 | No Variation | 0.48402 |

| Q23 | 0.77283 | 0.77283 |

| Q24 | 0.23304 | 0.12943 |

| Q25 | 0.77283 | 0.07260 |

| Q26 | No Variation | 1.00000 |

| Q27 | 0.23304 | 0.77283 |

| Q28 | 0.34578 | 1.00000 |

| Q29 | 1.00000 | 0.42371 |

| Q30 | 0.03689+ | No Variation |

| Q31 | 0.42371 | 0.76559 |

Results of the Wilcoxon test pw and t-test pt on the total level, competency wide and for each individual question.

Significant results are marked with +.

The item-level analysis shows no normality and no significant changes between pre- and post-test responses (see Table 5). All comparisons, except for Q30 in the winter semester (pw = 0.037), fail to reach statistical significance, indicating that the intervention did not produce notable shifts in participants’ answers.

4.2 Attitudes & motivation (RQ2)

4.2.1 Winter semester

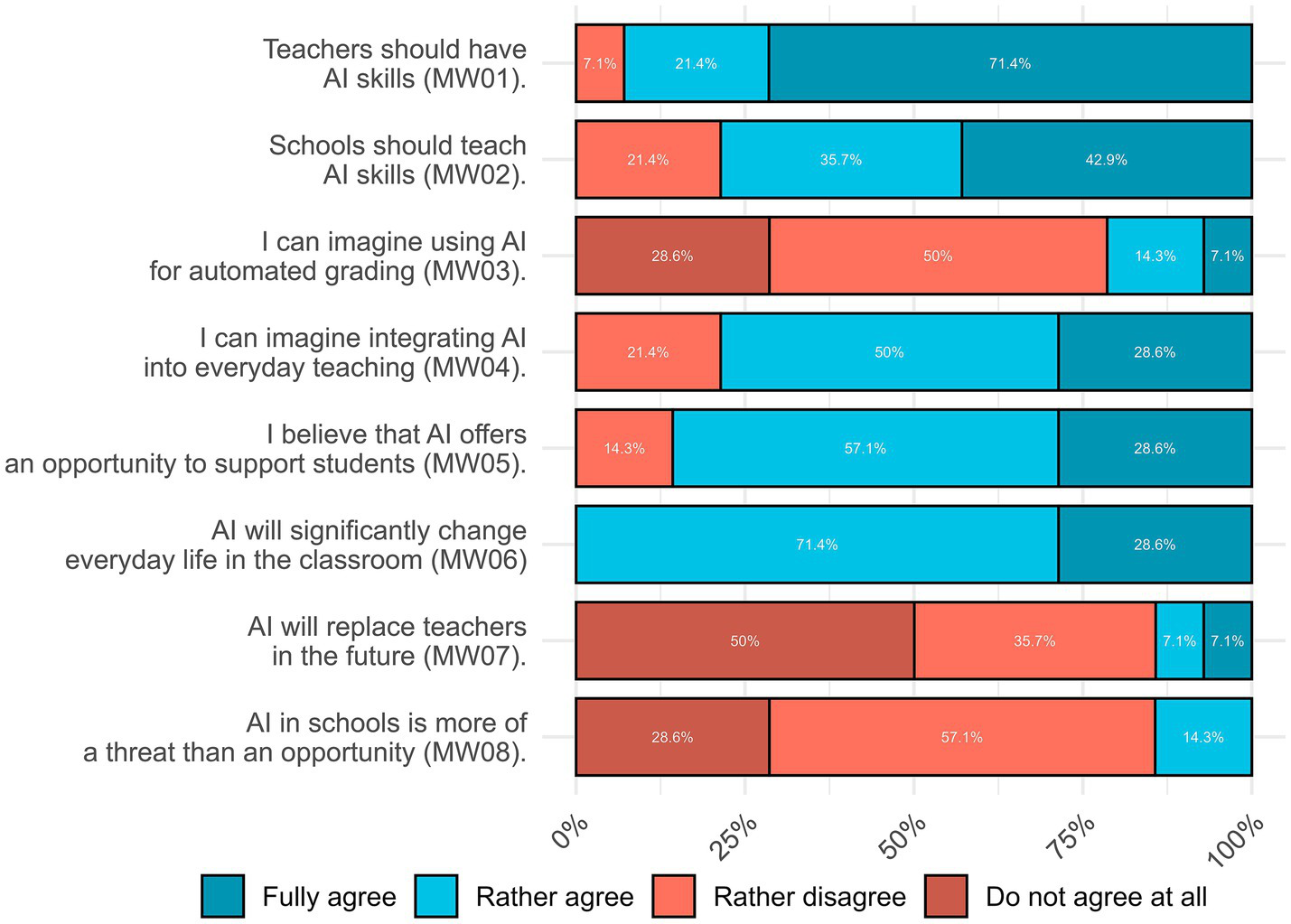

Table 6 presents the item-level descriptive statistics for the eight attitudinal statements. Means ranged from 0.94 to 2.35, medians from 1.0 to 2.0, and standard deviations from 0.44 to 0.90 on the 0–3 agreement scale. The observed values spanned the full range on most items.

Table 6

| Item | Mean | Median | SD | pw |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW01 | 2.35 | 2.00 | 0.47 | 0.239 |

| MW02 | 2.29 | 2.00 | 0.66 | 0.287 |

| MW03 | 1.59 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.0014+ |

| MW04 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.0624 |

| MW05 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 0.0782 |

| MW06 | 2.41 | 2.00 | 0.51 | 0.117 |

| MW07 | 2.24 | 2.00 | 0.66 | 0.0012+ |

| MW08 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.000827+ |

Descriptive statistics for winter-semester attitudes and results of the Wilcoxon test pw.

Significant results are marked with +.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of responses to the attitude statements administered in the winter semester. Most participants agree that teachers should have AI skills (over 90% agree or fully agree), whereas opinions on automated grading (MW03) are divided, with about half disagreeing. Views on AI replacing teachers (MW07) tend strongly toward disagreement, and most reject the notion that AI in schools is more threat than opportunity (MW08).

Figure 2

Comparison of total scores in the winter and summer group, the dashed line shows the mean and the solid line the median.

All eight items violated normality, so the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used throughout. Table 6 shows the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests against the neutral midpoint. The three noticeable statements mentioned above, MW03, MW07 and MW08 displayed significant deviations from neutrality.

4.2.2 Summer semester

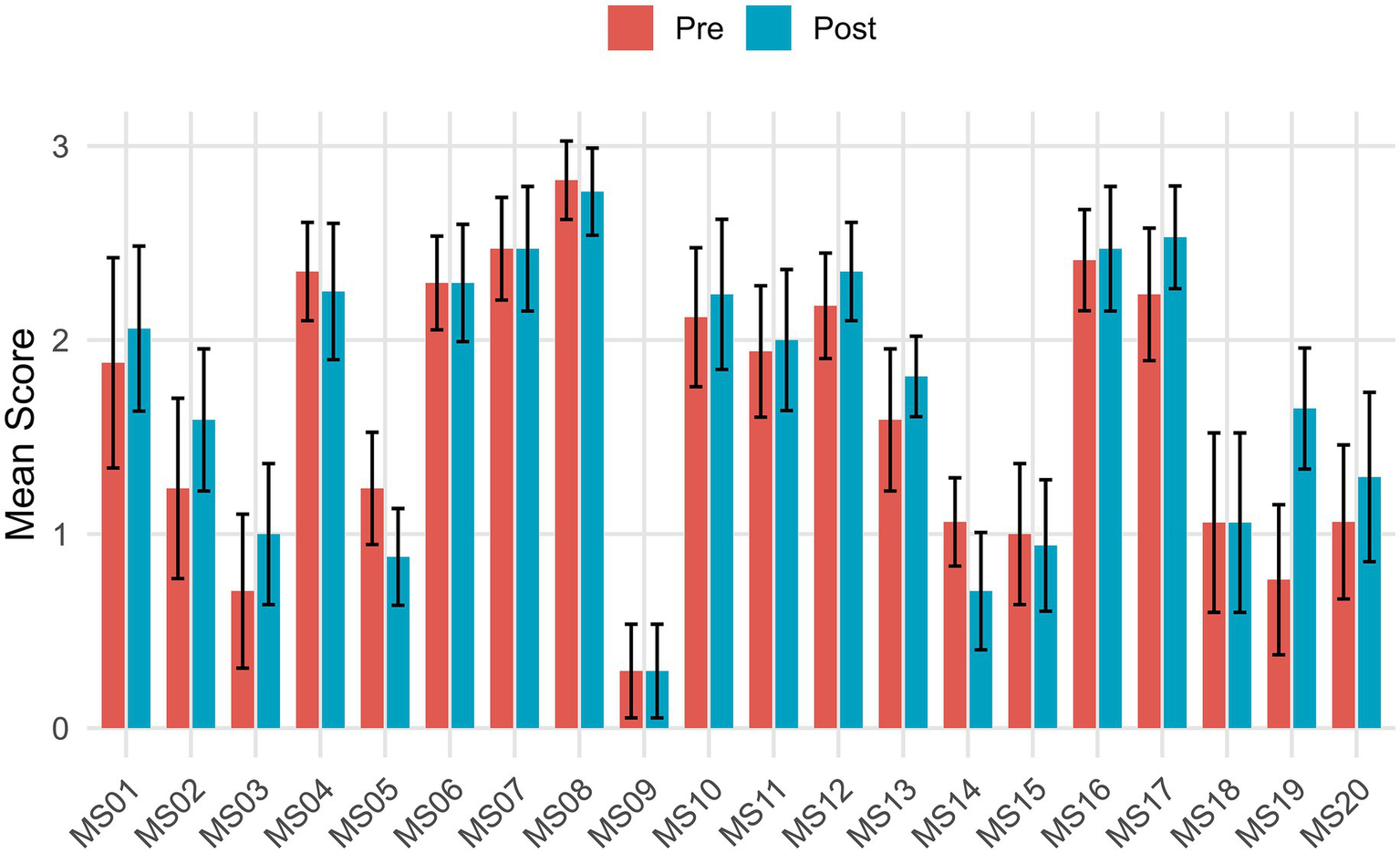

The analysis examined changes in the attitudes and knowledge of the participants regarding AI in the educational field. Participants’ responses show slight shifts in their perceptions and usage of AI from pre- to post-test (see Figure 3). Some items, like regular use of AI in studies (MS01), frequency of AI use in daily life (MS02), and voluntary engagement with AI (MS03) showed small increases in mean scores and either stable or slightly improved medians and standard deviations (see Table 7).

Figure 3

Participants perspectives on AI in education, indicating levels of agreement across various statements.

Table 7

| Statement | Mean | SD | Median | Wilcoxon pw | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| MS01 | 1.88 | 2.06 | 1.05 | 0.83 | 2 | 2 | 0.233 |

| MS02 | 1.24 | 1.59 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 1 | 2 | 0.048+ |

| MS03 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 1 | 1 | 0.110 |

| MS04 | 2.35 | 2.25 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 2 | 2 | 0.484 |

| MS05 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 1 | 1 | 0.095 |

| MS06 | 2.29 | 2.29 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 2 | 2 | 1.000 |

| MS07 | 2.47 | 2.47 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 2 | 3 | 1.000 |

| MS08 | 2.82 | 2.76 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 3 | 3 | 0.766 |

| MS09 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| MS10 | 2.12 | 2.24 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 2 | 2 | 0.572 |

| MS11 | 1.94 | 2.00 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 2 | 2 | 0.821 |

| MS12 | 2.18 | 2.35 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 2 | 2 | 0.345 |

| MS13 | 1.59 | 1.81 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 2 | 2 | 0.129 |

| MS14 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.59 | 1 | 1 | 0.089 |

| MS15 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 1 | 1 | 0.850 |

| MS16 | 2.41 | 2.47 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 2 | 3 | 0.766 |

| MS17 | 2.24 | 2.53 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 2 | 3 | 0.089 |

| MS18 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

| MS19 | 0.76 | 1.65 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 1 | 2 | 0.004+ |

| MS20 | 1.06 | 1.29 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 1 | 1 | 0.182 |

Descriptive statistics and results of the Normality-test psw and the Wilcoxon test pw.

Significant results are marked with +.

Shapiro–Wilk tests on each item’s pre-post change score showed that none of the motivational change scores met the normality assumption. Accordingly, all item-level pre–post comparisons were conducted with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Table 7 shows certain areas, like the belief that AI will significantly change everyday teaching (MS04) or the notion that AI in schools is more of a threat than an opportunity (MS05), displayed minimal fluctuations in means and varying adjustments in standard deviations, without major directional changes. A few items, such as the importance of teacher training on AI (MS11, MS16) or integrating AI into everyday teaching (MS17), showed small but not significant positive shifts in mean and median values (see Table 7). Table 7 further displays significant changes only occurred regarding the feeling of being prepared to integrate AI into their own teaching (MS19) and using AI regularly in their everyday life (MS02).

5 Discussion

5.1 AI literacy (RQ1)

The winter and summer iterations represent two successive cycles, each providing insights into the stability and adaptability of the intervention design under varying conditions. These conditions are namely a full 6E circle after Henze et al. (2022) in the first iteration in winter 2023/2024 or a 5E circle with self-study elements after Bybee et al. (2006).

At the competency level, covering all AI literacy competencies by Hornberger et al. (2023) after Long and Magerko (2020), the pre-post comparisons yielded no statistically significant changes in either iteration. Nevertheless, the overall trend and consistency of these changes provide insights into how effective the intervention was and how the instructional design contributed to its impact.

The mean scores for the competencies Recognizing AI (C01) and Ethics (C16) declined slightly in both iterations, likely reflecting cognitive recalibration as participants reassessed assumptions after comparing AI-generated definitions and encountering complexities like hallucinated outputs. This aligns with findings by Bewersdorff et al. (2023), who observed confusion among learners over basic AI concepts, and Zhao et al. (2022), who argue that understanding AI’s ethical implications requires more than surface-level familiarity. These topics require abstraction and comparison, which benefit from social interaction. Without sufficient scaffolding, learners may (falsely) question prior knowledge, leading to declining values. In winter, debate and collective reflection in the Exchange-Phase appeared to slightly stabilize understanding, whereas in summer, the absence of exchange limited reflection to the individual level may have fostered uncertainty.

The competencies Decision-Making (C08) and Critically Interpreting Data (C13) remained unchanged, indicating competencies without explicit instructional focus are unlikely to develop. Despite exercises with Teachable Machine, the transfer from simple, self-trained models to larger AI systems appeared unsuccessful or partial. This means that simply using basic tools like Teachable Machine is apparently not enough for the transfer to more complex AI systems. None of the phases of the 5E or 6E model addressed these skills directly and in depth in any of the iterations. The lack of specific tasks may have led to stagnation. Since skills do not develop automatically without being explicitly promoted, this highlights a specific area for improvement in the next iteration.

Other competencies showed divergent trends: Understanding Intelligence (C02) increased in winter but declined in summer, likely due to instructor-led scaffolding versus self-study format, even though the basic definitions and content regarding AI was transmitted in the same way. AI’s Strengths & Weaknesses (C05) improved slightly in winter but remained unchanged in summer, again underscoring the value of peer dialogue. Representations (C07) increased slightly in winter but decreased in summer, suggesting that collaborative exploration in person supported deeper engagement than self-study. From a Vygotskian perspective, the absence of peer interaction and teacher scaffolding in summer limited movement beyond the zone of proximal development (Leong and Bodrova, 1996). These skills appear particularly dependent on the Exchange phase, and their decline in summer highlights the sensitivity of such competencies to format variations.

The Human Role in AI (C10) decreased in winter but increased in summer, with independent work possibly prompting deeper reflection on educational uses of AI. Learning from Data (C12) dropped in winter but rose in summer, suggesting that self-guided critique enhanced understanding despite limited instruction. Programmability (C17) remained unchanged in winter, likely due to a ceiling effect while increasing slightly in summer. Overall, these trends indicate that while the intervention activated selective knowledge, its effectiveness varied by content and format. The self-study setting appeared to support individual reflection on teachers’ roles (C10) and data critique (C12), while the winter format emphasized collective error analysis. Thus, certain competencies (C10, C12) may benefit more from individual engagement.

Four competencies showed positive development across both iterations: Interdisciplinarity (C03) increased, especially in summer, as participants connected AI to educational contexts. The competencies General vs. Narrow (C04) and Machine-Learning-Steps (C09) improved in both groups likely due to specific instructional focus using concrete examples. Data Literacy (C11) showed slight gains in both groups, possibly from critically assessing AI-generated outputs. Participants were apparently able to build on prior knowledge and exceed their ZPD through scaffolding. Here, Explore (practical tools such as Teachable Machine), Explain (technical concepts) and Elaborate (lesson plan with AI) worked synergistically. Even in the summer, in the self-study format of the Elaborate phase, the tasks were sufficient to achieve progress. This stability indicates robust design elements such as contextually embedded learning effectively support foundational AI literacy regardless of format.

The only statistically significant item-level change occurred in winter for Q30 (ethical implications of predictive policing), suggesting themes intersecting with ethical, societal, or real-world controversies may resonate more strongly with learners, prompting them to reassess their stance more readily than with purely technical or conceptual content. Without Exchange phase in the summer, this effect was missing, so there was no change. The comparison of the iterations shows that ethical content requires collective discussion.

Several knowledge items exhibited either complete stability or no measurable variation across the two iterations (e.g., Q6, Q22, Q26 in winter and Q17, Q30 in summer; see Table 5). This can either be explained with ceiling effects, items such as Q22 and Q26 in the winter were already answered correctly by all participants in the pre-test. When prior knowledge is already high, even effective instruction produces limited statistical movement. Secondly, conceptual and ethical complexity may explain the results of items such as Q30 (predictive policing). In the winter iteration, this question showed significant improvement, while in the summer’s self-study format, it showed no variation. This contrast underscores that socially mediated reasoning and collective discourse seem to have been critical for addressing morally or societally charged content. Without opportunities for peer negotiation and instructor scaffolding, participants may have lacked the dialogic space needed to compare ethical standpoints and reconstruct their understanding. From a design-based research perspective, such non-changes are informative because they expose where the intervention’s reach was limited. Rather than representing a null result, they indicate the boundaries of current design effectiveness.

In winter, questions initially answered correctly by all participants (Q22, Q26) remained stable, while some low-baseline items (Q12, Q30) showed increased means, suggesting that topics previously less understood benefitted to a degree from the intervention. In summer, slight mean increases emerged in items that started lower (Q19, Q20, Q24), though improvements were not statistically significant. The summer’s self-study format may have limited engagement compared to winter’s face-to-face sessions. The fact that participants still displayed considerable variability in their responses indicates that learners internalized the material unevenly. While some individuals may have deepened their comprehension, others remained uncertain or unconvinced. Together, these findings illustrate that while certain competencies and items can be reinforced through individual reflection, more complex or abstract elements require structured scaffolding and collective engagement within the 6E framework to foster consistent development.

Although all differences between the two iterations are interpreted towards scaffolding and social negotiation, this remains theoretical. No qualitative process data were collected that could directly show how scaffolding or peer interaction affected the participants. However, the quantitative pattern of competency change developed only when peer discussion was available and is consistent with Vygotskian accounts of scaffolded learning. Therefore, the link between scaffolding and observed effects should be understood as a theory-based inference grounded in established learning principles rather than a directly measured causal mechanism.

These trends show short interventions can activate selective elements of AI literacy when grounded in hands-on experience and critical evaluation. This resonates with Long and Magerko (2020), who emphasize the importance of hands-on, reflective learning in developing AI literacy, while Zhao et al. (2022) identified a positive correlation between hands-on AI applications and an improved understanding of AI ethics.

However, as Viberg et al. (2023) noted, professional development should focus on enhancing fundamental AI knowledge rather than comprehensive technical methodologies. Therefore, short-term interventions may be insufficient for fostering comprehensive AI literacy, underscoring the need for repeated, context-rich engagements to address misconceptions, as Lin et al. (2022) suggested.

5.2 Attitudes and motivation (RQ2)

5.2.1 Winter semester

For the emotional-motivational measures, the winter semester survey showed statistically significant deviations from neutrality in three items, specifically regarding the use of AI for automated grading (MW03), concerns about AI replacing teachers (MW07), and perceptions of AI as more of a threat than opportunity (MW08).

Hesitancy toward applying AI directly for automated grading (MW03) indicates deeper concerns about trusting AI with important evaluative tasks, reflecting broader apprehensions about delegating core pedagogical decisions to AI and highlighting the need for ethical AI training that fosters trust while retaining teacher agency. The concern that AI might eventually replace teachers (MW07) highlights a slight apprehension that automation could undermine the role of human educators, but most of the students (85.7%) think AI will not replace teachers. Similarly, the view that AI in schools poses more of a threat than an opportunity (MW08) reveals the students do not fully agree with that. Together, these two results highlight that while participants accept the necessity for AI competencies and foresee positive changes, they draw a clear line at ceding core pedagogical functions to machines. The participants’ perspectives underscore the importance of integrating ethical considerations and human-centered approaches into AI literacy programs, like Zhao et al. (2022) as well as Padma and Rama (2022) also proposed.

Even though not significantly different from the neutral point, the participants showed pronounced agreement that teachers should possess AI skills (MW01) and that schools should explicitly integrate AI into their curricula (MW02), although the intensity of that support and the exact nature of integrating AI into curricula may still be subject to individual interpretation, highlighting the importance of developing contextually relevant AI educational resources. This aligns with Zhao et al. (2022), who emphasize the critical role teacher preparedness plays in the effective adoption of AI technologies. The support for teacher training reflects a general awareness among future educators of AI’s relevance in modern educational settings.

A moderate, however not statistically significant level of agreement that AI could be integrated into everyday teaching (MW04) complements the earlier findings. Although students generally view AI usage as favourable, the variability in the answers highlights that comfort with large-scale AI utilization may still be developing. Similarly, the idea that AI offers an opportunity to support students (MW05) was met with agreement, again reflecting a positive perspective. The belief that AI will significantly change everyday classroom life (MW06) is widely accepted, but the absence of statistical significance suggests that, while change is anticipated, the participants are not consistently convinced about the scale of this transformation. This indicates that, although they acknowledge AI’s potential impact, they remain cautious about predicting the range and speed at which these changes will happen.

From a Vygotskian perspective, attitudes toward automated grading (MW03) may lay outside participants’ ZPD, as the lack of trust in AI required intensive scaffolding and collective negotiation. Within the 5E/6E framework the absence of the Exchange phase in summer therefore likely limited opportunities to address such fears, whereas in winter, the available discussion space may have supported collective processing of concerns. Within a DBR perspective, this iteration underscores that sensitive issues such as automated assessment must be deliberately addressed in the design of interventions.

Concerns about AI replacing teachers (MW07) and the perception of AI as a threat rather than an opportunity (MW08) similarly point to the value of peer interaction. Vygotskian theory suggests that social contexts helped participants learn through dialogue (Leong and Bodrova, 1996). The Exchange phase in winter appears to have provided conditions for perspective-taking, whereas in summer, the lack of such peer dialogue may have reduced opportunities to resolve cognitive conflict. From a DBR standpoint, these results argue for the inclusion of structured debate elements in future iterations to ensure controversial topics are productively explored.

By contrast, the high baseline agreement that teachers should acquire AI skills (MW01) and that AI should be integrated into curricula (MW02) indicates that these items already fell within the learners’ ZPD. Here, the Engage and Explain phases were sufficient to reinforce existing beliefs, without requiring additional elaboration or exchange. Therefore, such stable convictions can be treated as anchors, while future interventions should focus on more fragile or contested areas of belief and practice.

5.2.2 Summer semester

The results from the summer semester group show that even a relatively brief intervention can influence participants’ perceptions, knowledge, and confidence in engaging with AI within educational settings, albeit to a small extent. The pre-post comparison revealed statistically significant shifts in two items. Students reported feeling significantly more prepared to integrate AI into their teaching practices (MS19) and demonstrated an increased use of AI in daily life (MS02) (see Table 7). These findings indicate the intervention’s effect on perceived pedagogical readiness and practical AI engagement. The MS02 increase suggests learners began viewing AI as a tool integrated into everyday routines or recognizing AI more often, while MS19 captures increased professional confidence. These shifts demonstrate that task-based exposure to AI systems can bridge the gap between conceptual understanding and applied confidence, resonating with the emphasis of Zhao et al. (2022) on direct interaction to foster self-efficacy. These improvements occurred despite the self-study format, suggesting autonomous exploration with authentic tasks can yield self-perceived competence gains. The self-reflective task structure encouraged participants to critically appraise AI for teaching needs, enhancing both usage behaviour and pedagogical preparedness, indicating even short, professionally relevant interventions can stimulate meaningful change in personal and instructional domains of AI readiness.

Other attitudinal items showed minor, non-significant variations (see Figure 4; Table 7). Slight gains in voluntarily educating oneself about AI (MS03) suggest rising intrinsic motivation as participants discover AI’s relevance, with Zhao et al. (2022) noting motivation as key to improving AI literacy. The data shows agreement that schools should teach AI competencies (MS07), reflecting recognition of AI literacy’s growing importance in curricula, as supported by Hornberger et al. (2023).

Figure 4

Pre-post comparison of means with 95%-confidence interval as error bars.

Beliefs about AI’s impact on everyday teaching (MS04) slightly receded, indicating stronger anticipation of fundamental change, while items regarding teacher involvement in AI tool decisions (MS12) and AI fostering independent learning (MS13) showed small improvements. Chounta et al. (2022) emphasize educators’ role as mediators in AI adoption. The stable mean for AI supporting students (MS06) and small increase in AI promoting classroom diversity and inclusion (MS10) highlight participants’ recognition of AI’s potential to address equity challenges, aligning with Lin et al. (2022). This stability reflects participants’ sustained confidence in AI’s supportive classroom role, with recent studies highlighting personalized learning pathways (Chounta et al., 2022) enhancing inclusivity (Zhao et al., 2022). While initial enthusiasm may decrease as participants gain more realistic understanding, dimensions like teacher agency and student autonomy gain traction as participants consider practical aspects of AI integration.

Results show a small decline in perceived risk of AI in schools (MS05), suggesting a gradual reduction of concerns rather than excitement. The stable but very low perception of AI replacing teachers (MS09) contrasts with participants’ readiness to accept teacher training (MS11, MS16) and teacher involvement in AI decisions (MS12). The strong agreement that teachers should possess AI competencies (MS08) underscores the necessity for educators to navigate AI integration, with Zhao et al. (2022) highlighting that equipping teachers with AI skills is critical.

Items showing small increases in mean values, such as prioritizing teacher training (MS16) and integrating AI into everyday teaching (MS17), also saw improved medians and reduced variability, suggesting participants are becoming more consistent in these positions. Participants favor a future where educators remain central figures who leverage AI to enhance instruction rather than give up control (Chounta et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2022).

While certain perceptions advanced, attitudes toward automated grading (MS18) and institutional support for AI use (MS20) showed minimal change at relatively low levels, suggesting resistance to short-term interventions. MS18 showing no changes suggests that ethical or high-stakes educational decisions are not easily reconsidered through brief, individual reflection, but seem to require collective negotiation and contextualized experience. Even when participants recognise AI’s potential benefits, they tend to maintain clear boundaries regarding professional autonomy. Also, topics of items linked to institutional or policy-level constructs were not explicitly addressed in the learning activities and depend largely on perceived external structures. Chounta et al. (2022) similarly report teachers would prefer using AI to help with grading rather than fully automated grading. Views on transparency of data protection policies (MS14) remained low, while belief that parents should be involved in AI classroom decisions (MS15) maintained high agreement levels with slight increases post-intervention.

From a Vygotskian perspective, significant gains in AI use in daily life (MS02) and preparedness for teaching (MS19) indicate that the intervention may have directly engaged the learners’ ZPD: independent, authentic tasks seem to be able to foster a sense of competence. Within the 5E/6E model, the self-reflective Evaluate phase appears to have supported this development, demonstrating that even without peer exchange, individual reflection can drive perceived readiness. Smaller gains in voluntary engagement (MS03), teacher training (MS11, MS16), and integration into everyday teaching (MS17) underline that intrinsic motivation and professional awareness can be strengthened when learners generate their own teaching materials and apply concepts practically. Declines in expectations about AI fundamentally transforming teaching (MS04) suggest cognitive recalibration, as initial enthusiasm seems to be tempered by realistic engagement. By contrast, persistent low means for abstract or sensitive issues such as automated grading (MS18), data protection (MS14), and institutional support (MS20) indicate that without scaffolding and structured peer dialogue, these items remain difficult to shift. The absence of an Exchange phase in the summer group likely limited collective negotiation around such contested topics.

5.3 Broader implications

The iterative design of the two-session intervention provided selective but limited support for the development of AI literacy among pre-service physics teachers. Across both iterations, total literacy scores showed small, non-significant increases, indicating that short interventions can activate specific competencies but are insufficient for comprehensive progress. Competencies with direct instructional focus and hands-on activities displayed consistent gains in both iterations. By contrast, competencies without targeted scaffolding remained stable, while ethically or conceptually demanding areas sometimes declined, suggesting cognitive recalibration in the absence of sustained guidance.

Given the sample size of n = 31 from a single program and the design-based, two-iteration context, the results should be interpreted primarily as context-specific insights rather than universally generalizable causal effects. Effect estimates are exploratory and sensitive to sampling error and the value of the present study lies in the design principles it surfaces for this setting.

Nevertheless, the iterative DBR design highlighted the role of instructional format in this context. The winter semester, which included collective Exchange and in-person scaffolding, supported competencies that rely on social negotiation and teaching. In contrast, the summer self-study version promoted more individual reflection, with small gains in competencies such as learning from data or the human role in AI but failed to sustain progress in socially embedded competencies.

The 6E instructional structure provided an effective scaffold, particularly through Explore, Elaborate, and Evaluate, which enabled hands-on practice and critical engagement with AI tools. However, the absence of the Exchange phase in the summer iteration limited opportunities for collaborative reflection, diminishing development in ethical and conceptual dimensions. The DBR framework proved valuable for uncovering design-sensitive effects, such as gains in some areas regardless of format, but also format-dependent differences that emphasize the importance of social interaction, scaffolding, and iterative refinement.

The stable results observed across both iterations offer valuable insights for interpreting the boundaries of the current design. Rather than signaling ineffectiveness, the non-change outcomes highlight where learning may require greater depth, scaffolding and time. Ethical and policy-related constructs such as data protection, automated grading, or predictive policing appear particularly dependent on dialogic engagement and contextualized examples, suggesting that future iterations should extend opportunities for collaborative reasoning and adapt item difficulty to capture incremental growth.

Beyond the physics context, these findings also hold relevance for other subject areas in teacher education. The 6E framework, particularly the Exchange phase, can be adapted to foster AI literacy in disciplines such as mathematics, languages, or the social sciences. Collaborative reflection and peer negotiation could support subject-specific objectives, help evaluate AI-generated problem solutions, essays, or data visualizations, and address ethical and pedagogical challenges.

Similar patterns have been reported in other teacher-education contexts. For instance, early-childhood education students valued ChatGPT for lesson planning but highlighted the need to critically evaluate its outputs critically (Nikolopoulou, 2024). These parallels suggest that the 6E framework may serve as a transferable scaffold for supporting AI literacy development across disciplines beyond physics.

Ishmuradova et al. (2025) identified clusters ranging from enthusiastic to skeptical among pre-service science teachers when analyzing perceptions of generative AI. The present study’s finding of simultaneous optimism and critical caution among physics pre-service teachers mirrors this broader tendency, suggesting that the ambivalence toward generative AI is not domain-specific but characteristic of teacher education.

Taken together, the findings indicate that iterative, design-based interventions grounded in the 6E model and Vygotskian principles can selectively foster AI literacy. However, to achieve broader and more sustained development, interventions require repeated engagements, explicit scaffolding for complex competencies, and dedicated space for collaborative reflection.

Regarding RQ2, pre-service teachers across both semesters demonstrated a consistent perspective that embraces AI as a pedagogical tool while establishing boundaries against delegating core teaching functions to automated systems. This manifested in resistance to automated grading despite general openness to AI integration,

The significant increase in participants’ perceived readiness to integrate AI into teaching (MS19) alongside increased daily AI use (MS02) demonstrates that even brief interventions can bridge the gap between abstract knowledge and practical application confidence. This transformation represents a crucial step in preparing future teachers for AI-enhanced educational environments.

6 Implications and limitations

This study offers insights into the challenges and opportunities of integrating AI literacy into teacher training programs, while also highlighting several methodological and contextual limitations. First, the sample is small and drawn from a single teacher-education program, which limits statistical power and external validity. Accordingly, findings should be treated as context-bound design principles rather than generalizable causal effects. Future studies should aim for larger, more diverse participant pools across multiple teacher education programs to enhance generalizability and statistical power.

The findings emphasize the importance of embedding AI literacy as a component of teacher education, with a focus on sustained and iterative learning. Although the lack of significant changes in most survey items suggests that the interventions had limited measurable impact, the single significant result in the winter semester indicates that targeted areas of AI literacy can be positively influenced through focused instructional efforts.

The short-term nature of the intervention points to the need for more sustained efforts. Future research should implement longitudinal programs spanning multiple sessions with structured follow-up activities. Researchers might consider establishing communities of practice where participants can continue developing their AI skills beyond formal interventions.

The study’s limitations reveal areas for improvement in future research and practice. The lack of sensitivity in certain survey items, evidenced by no variability in several knowledge questions, suggests a need for revised and more targeted assessments. Furthermore, the reliance on quantitative methods alone may have restricted the ability to capture shifts in understanding or attitudes. Incorporating qualitative approaches could provide a more comprehensive picture of participants’ experiences and the intervention’s impact. Pre-existing knowledge and attitudes toward AI may have influenced the results, underscoring the importance of using pre-assessments to tailor interventions to initial competency levels. Future interventions could implement adaptive learning environments that respond to participants’ knowledge and provide personalized learning experiences. Researchers should also consider controlling for technology self-efficacy and prior AI exposure as potential confounding variables in their analyses. Moreover, the proposed link between scaffolding and performance differences is inferred rather than directly observed, therefore subsequent DBR iterations should combine quantitative results with qualitative process data to substantiate this mechanism.

7 Conclusion

The study was conducted in two iterations, one in the winter semester 2023/2024 and one in the summer semester 2024. The iterative design of the two-session AI intervention provided selective but limited support for developing AI literacy among pre-service physics teachers. Across both iterations, total literacy scores showed only small, non-significant increases, suggesting that short interventions can activate specific competencies but are insufficient for comprehensive progress. Competencies with explicit instructional focus and hands-on activities displayed consistent gains, while those lacking targeted scaffolding remained stable, and ethically or conceptually demanding areas sometimes declined, indicating cognitive recalibration in the absence of sustained guidance.

Future designs should therefore strengthen scaffolding for complex competencies through structured peer discussions and systematically embed ethics. The 6E model proved effective through all original 5E phases, but the Exchange phase seems to be essential. Its absence in summer reduced socially negotiated learning, underscoring the need to secure space for collaborative reflection even in self-study contexts. Balancing peer dialogue with opportunities for individual reflection may best support diverse learning processes.

The DBR approach revealed format-sensitive effects, such as in-person scaffolding and exchange supported socially embedded competencies, while self-study fostered individual reflection on data use and the human role in AI. Large individual differences further suggest that differentiated tasks of varying complexity are needed to meet learners at different points in their ZPD. Iterative refinement should now test hybrid formats, extend hands-on engagement beyond simple models, and evaluate longitudinal effects across multiple sessions.

Taken together, these findings highlight that iterative, design-based interventions grounded in Vygotskian principles can selectively foster AI literacy. To achieve broader and more sustainable development, however, repeated engagements, explicit scaffolding, and collaborative reflection remain indispensable.

Future research should explore more extensive interventions that provide repeated, contextualized engagements with AI in educational settings. By enhancing AI literacy in pre-service teacher education through sustained, professionally relevant interventions, teacher education programs can better prepare future educators to navigate AI-enhanced educational environments with both critical awareness and practical competence.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was not required for this study, as the data collected were anonymized, and the survey did not involve sensitive or health-related topics. Participants were not exposed to any risk or burden, and the information gathered was and is not personally identifiable. Additionally, the survey was conducted solely for research purposes related to general study conditions, without any impact on participants’ academic assessment, rights, or well-being. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SB-G: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The ComeMINT project is funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research as part of the BMBF funding line ‘Competence Centers for digital and digitally supported teaching in schools and continuing education in the STEM Field’, funding code 01JA23M06G.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. This manuscript was linguistically developed and revised for better readability using OpenAI ChatGPT 4o, Anthropic Claude 3.7 Sonnet and the translation tool DeepL.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1707534/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^ https://chat.openai.com/ (registration required).

2.^ https://www.perplexity.ai/

3.^ https://app.magicschool.ai/raina (registration required).

References

1

Anderson T. Shattuck J. (2012). Design-based research. Educ. Res.41, 16–25. doi: 10.3102/0013189X11428813

2

Bewersdorff A. Zhai X. Roberts J. Nerdel C. (2023). Myths, mis- and preconceptions of artificial intelligence: a review of the literature. Comp. Educ. Artif. Intellig.4:100143. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100143,

3

Bybee R. (2009). The BSCS 5E instructional model and 21st century skills: A commissioned paper prepared for a workshop on exploring the intersection of science education and the development of 21st century skills

4

Bybee R. Taylor J. Gardner A. Van Scotter P. Carlson Powell J. Westbrook A. et al . (2006). The BSCS 5E instructional model: origins and effectiveness. Available online at: https://media.bscs.org/bscsmw/5es/bscs_5e_full_report.pdf (Accessed November 10, 2021).

5

Chen L. Chen P. Lin Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence in education: a review. IEEE Access8, 75264–75278. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988510

6

Chiu T. K. F. (2025). AI literacy and competency: definitions, frameworks, development and future research directions. Interact. Learn. Environ.33, 3225–3229. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2025.2514372

7

Chounta I.-A. Bardone E. Raudsep A. Pedaste M. (2022). Exploring teachers’ perceptions of artificial intelligence as a tool to support their practice in Estonian K-12 education. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ.32, 725–755. doi: 10.1007/s40593-021-00243-5

8

Ding L. Li T. Jiang S. Gapud A. (2023). Students’ perceptions of using ChatGPT in a physics class as a virtual tutor. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ.20. doi: 10.1186/s41239-023-00434-1

9

Duran L. B. Duran E. (2004). The 5E instructional model: a learning cycle approach for inquiry-based science teaching. Sci. Educ. Rev.5, 49–58. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1058007.pdf

10

Farrokhnia M. Banihashem S. K. Noroozi O. Wals A. (2024). A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: implications for educational practice and research. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int.61, 460–474. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2023.2195846

11

Henze J. Schatz C. Malik S. Bresges A. (2022). How might we raise interest in robotics, coding, artificial intelligence, STEAM and sustainable development in university and on-the-job teacher training?Front. Educ.7:872637. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.872637

12

Hornberger M. Bewersdorff A. Nerdel C. (2023). What do university students know about artificial intelligence? Development and validation of an AI literacy test. Comp. Educ. Artif. Intellig.5:100165. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100165,

13