Abstract

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, its applications in medicine have grown increasingly widespread. In particular, AI has shown significant potential within residency education. This review examines current uses of AI in residency training, focusing on innovative educational models, curriculum design, outcome assessment, and existing challenges. By analyzing recent research across medical specialties, the discussion explores the role of AI in personalized learning, examination assistance, and clinical decision support. Furthermore, future strategies for integrating AI into residency education are proposed. This article aims to provide a comprehensive theoretical and practical reference for medical educators and policymakers, supporting the scientific application and continued development of AI in residency training.

1 Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming healthcare, reshaping both patient care and medical education. Within this context, residency training has emerged as a particularly promising area for AI integration. AI-driven tools now offer innovative solutions that enhance educational efficiency and address long-standing challenges in residency programs.

Residency training serves as a critical bridge between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice. However, it continues to face several key hurdles, including the overwhelming volume of medical knowledge, limited faculty resources, and outdated teaching methods. This “knowledge explosion” requires innovative educational strategies. AI can help alleviate these burdens through personalized learning pathways, optimized content delivery, and real-time performance feedback.

AI offers significant opportunities across three key areas of residency training: knowledge acquisition, skill development, and assessment. Specifically, it enables tailored content for self-paced learning, AI-enhanced simulations with real-time performance feedback, and adaptive testing with analytical insights. However, these advancements come with challenges. Data privacy concerns, regulatory requirements, potential algorithmic bias, and the need to ensure AI complements—rather than replaces—traditional teaching must all be carefully addressed. Educators are therefore tasked with critically evaluating the effectiveness of AI tools before integration.

The thoughtful incorporation of AI into residency training holds the potential to enhance medical education by delivering more personalized and efficient learning experiences. This review examines current AI applications, evaluates their effectiveness, and explores both challenges and future directions. Through this approach, the review seeks to inform and advance the ongoing dialogue on the role of AI in shaping the future of medical training.

2 Current application of AI in residency education

2.1 AI applications in different specialties

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into medical education has sparked considerable interest, particularly within residency training. In dermatology, generative AI platforms such as ChatGPT are being utilized to assist residents in preparing for board exams. For instance, a recent study reported that ChatGPT achieved 67% accuracy on 370 simulated European Board of Interventional Radiology questions (Ebel et al., 2024), demonstrating its potential to generate medical knowledge and provide immediate feedback. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. These include reduced performance on complex questions, reliance on potentially outdated data that may exclude current guidelines, and an inability to replace traditional teaching methods—AI should instead serve as a supplementary tool. In dermatology, nuanced clinical decisions still require human oversight. Therefore, careful integration of AI into the curriculum is essential to ensure the comprehensive competency development of residents.

In cardiovascular medicine, AI is enhancing education, remote monitoring, and credentialing processes. By analyzing large cardiac datasets, AI applications improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes. For example, algorithms assist in interpreting electrocardiograms and echocardiograms, offering real-time feedback to trainees as they develop diagnostic skills (Nahm et al., 2025). AI-powered remote monitoring enables the continuous assessment of cardiovascular patients, facilitating timely interventions while also serving as an educational resource for residents in patient management. Furthermore, credentialing processes benefit from automated systems that evaluate physician performance and streamline board certification reviews. Despite these advances, challenges persist, including the need for robust clinical validation of AI tools and their effective integration into educational frameworks. While the field is shifting toward more personalized and efficient training, balancing technological innovation with foundational medical education principles remains crucial.

Radiology education is advancing through the integration of artificial intelligence, with training programs actively assessing its effectiveness. Recent studies highlight the implementation of AI-focused workshops and certificate courses designed for radiology residents, aimed at enhancing their understanding of AI’s clinical applications (Finkelstein et al., 2024). These educational initiatives typically combine didactic lectures, case-based discussions, and hands-on programming exercises to build both foundational knowledge and practical AI skills. Evaluations of such programs have demonstrated positive outcomes, including increased participant confidence in AI concepts and improved diagnostic capabilities following training (Hu et al., 2023). The success of these courses depends on several factors: relevance of the curriculum to clinical practice, seamless integration of AI tools into existing workflows, and ongoing support for residents as they navigate the complexities of AI.

Given the rapid pace of technological advancement, there is growing resident demand for continued AI education. This requires radiology programs to adapt proactively by developing targeted educational frameworks. Such frameworks must prepare radiologists to utilize AI tools effectively while upholding established standards of patient care.

2.2 AI-assisted knowledge acquisition and learning tools

Large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT are transforming medical education, particularly within residency training. They offer personalized learning pathways, instant access to medical knowledge, and realistic clinical scenario simulation. A key benefit lies in their ability to deliver tailored educational content that addresses individual learner needs. For example, one study demonstrated that custom GPT models achieved 83.6% accuracy in clinical knowledge delivery, significantly outperforming general AI models (Pu et al., 2025). This capacity for customization not only enhances learning effectiveness but also boosts engagement by allowing interactions aligned with individual resident learning styles. However, significant challenges remain, including concerns over the accuracy of AI-generated information, the risk of misinformation, and ethical considerations for clinical application.

Notably, AI systems can occasionally produce erroneous outputs or “hallucinations.” Consequently, medical educators must emphasize critical thinking and train residents to rigorously evaluate AI-generated content (Morosky et al., 2025).

Domain-specific GPT customization enhances both knowledge acquisition accuracy and resident satisfaction. Research shows that residents using custom GPT models report higher satisfaction compared to those relying on traditional methods, with notable gains in learning independence and confidence (Pu et al., 2025). By creating interactive and responsive learning environments, AI effectively complements existing educational frameworks.

However, this integration requires thoughtful curricular design to balance AI-driven tools with traditional teaching methods. Although AI supports knowledge acquisition, fostering critical thinking and clinical reasoning—skills essential to patient care—remains vital. As medical education continues to evolve, the role of AI in knowledge acquisition is likely to expand. Ongoing research and adaptive strategies will therefore be necessary to realize its full potential.

AI-assisted learning tools, particularly those based on LLMs, present significant opportunities to enhance clinical knowledge acquisition among residents. By delivering personalized, accurate, and timely information, these systems can improve both educational outcomes and learner independence.

However, integrating AI into medical education requires addressing several challenges, including concerns about information accuracy, ethical considerations, and the need for critical evaluation of AI-generated content. By successfully managing these issues, educators can effectively leverage AI to create dynamic and effective learning environments that prepare future physicians for evolving clinical demands.

3 Innovation in AI-driven medical education models

3.1 AI-assisted and AI-integrated educational paradigms

Medical education is evolving from traditional, linear knowledge transfer toward AI-assisted personalized learning. Traditional models often rely on uniform knowledge delivery, which may not accommodate varied learning styles or paces, creating potential gaps—especially in complex, rapidly advancing fields like medicine. In contrast, AI-assisted education employs data analytics and machine learning to tailor learning experiences. This approach enhances engagement by allowing learners to progress at their own pace, focusing on individual weaknesses while reinforcing strengths. For instance, AI systems can analyze resident assessment results and recommend targeted educational resources, thereby fostering more efficient and adaptive learning environments.

Such personalized training better prepares future physicians for the complexities of modern medical practice, where individualized patient care is increasingly essential (Xu et al., 2024).

AI also enhances learner autonomy, motivation, and confidence. By delivering immediate feedback and adaptive learning pathways, it empowers residents to take greater control of their education—a feature especially valuable in residency, given its significant time and cognitive demands. Through interactive case studies and simulations, AI-driven platforms enable self-directed practice in clinical decision-making within a risk-free environment. This exposure to varied scenarios helps build confidence and improves real-world preparedness.

Furthermore, AI integration can increase learner motivation. By visually displaying progress through data dashboards and incorporating elements of gamification, AI makes the educational experience more engaging and personally rewarding (Qian et al., 2022).

Beyond individual learning, AI fosters collaborative educational environments by connecting residents around shared learning goals. Through the use of performance data, platforms can intelligently match residents into study groups, thereby enhancing peer collaboration and knowledge sharing. This process mirrors the interdisciplinary teamwork that is essential to patient care.

As residents interact with peers and mentors on AI-enhanced platforms, they also cultivate crucial communication and teamwork skills. These competencies are fundamental for effective performance in clinical practice (Swed et al., 2022).

The transformative potential of AI extends to broader educational frameworks. As healthcare increasingly adopts AI technologies, medical curricula must incorporate training on ethical AI use, data interpretation, and the integration of these tools into clinical practice. Such training ensures that future physicians act not merely as consumers of AI, but as critical thinkers capable of evaluating the effectiveness and appropriateness of these tools.

By embracing AI-assisted educational models, residency programs can better prepare trainees for future healthcare challenges. This proactive approach has the potential to improve both patient outcomes and the overall quality of healthcare delivery (Zech et al., 2024).

3.2 Integration of remote education and virtual reality technology

Remote education and the integration of virtual reality (VR) are transforming resident training. Technologies such as VR, augmented reality (AR), and 3D printing create immersive, interactive learning environments that traditional methods cannot provide. A key educational role of VR is the simulation of complex clinical scenarios, allowing residents to practice procedures safely, without risk to real patients. Studies show VR simulations effectively prepare residents for high-stakes situations like resuscitation and surgery by replicating real-life stress and urgency (Chang et al., 2021). AR further supports hands-on training by overlaying digital information onto physical environments. This enhances spatial awareness and anatomical understanding during procedural practice (Bettati and Fei, 2023). Together, these technologies strengthen residents’ practical skills while fostering the critical thinking and decision-making abilities essential for clinical practice.

The integration of AI with immersive technologies significantly enhances training effectiveness. AI analyzes performance data from VR simulations to deliver personalized feedback and create adaptive learning pathways, targeting individual weaknesses while reinforcing strengths. For example, AI algorithms can track the time taken for critical actions during simulated procedures, pinpointing specific areas that require further practice (Ralevski et al., 2024). Immersive technologies, in turn, increase scenario realism, thereby improving learner engagement and memory retention—both essential for effective knowledge acquisition (Feinmesser et al., 2023). Together, this fusion of AI and immersive tools optimizes skill development and better prepares residents for the complexities of a technology-driven healthcare environment.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of remote education, underscoring its potential to bridge training gaps. As in-person opportunities became limited, residency programs increasingly turned to VR and remote simulations to maintain educational continuity (Mu et al., 2024). This shift not only demonstrated the feasibility of remote training but also validated its effectiveness, paving the way for hybrid educational models that blend virtual and in-person experiences.

The flexibility of remote education allows residents to train across different locations, improving accessibility while accommodating diverse learning needs and styles (Ogundiya et al., 2024). As medical education continues to evolve, the integration of VR, AR, and AI is expected to play a central role in shaping residency training. These technologies will help equip future physicians with the skills needed to navigate a rapidly changing healthcare landscape.

In conclusion, remote education and virtual reality represent significant advances in resident training. By utilizing immersive simulations and AI-driven feedback, these technologies enhance clinical skills and professional competencies, ultimately improving patient care.

As both remote platforms and VR continue to develop, their integration into medical education will become increasingly sophisticated. This evolution promises to unlock new opportunities for experiential learning and professional development across the field of medicine.

4 The role of AI in residency exams and assessments

4.1 Comparison of AI model performance in medical examinations

Advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly models like ChatGPT, are transforming medical education and assessment. Comparative studies evaluating different versions of ChatGPT on medical examinations highlight the potential of AI as a supplementary training tool. For example, an assessment of ChatGPT-3.5 and ChatGPT-4.0 on the Polish Final Medical Examination revealed that ChatGPT-4.0 achieved an accuracy of 77.55%, surpassing the 56% passing threshold and significantly outperforming ChatGPT-3.5, which scored 50.51% (Jaworski et al., 2024). This demonstrates notable improvements in capability across iterations.

ChatGPT-4.0 performed consistently across various medical disciplines, reflecting a strong grasp of diverse clinical domains. However, its tendency to express high confidence in answers—regardless of their accuracy—raises questions regarding its appropriate role in formal assessment. Current data suggest that while AI can support knowledge retention and application, it still lags behind human test-takers in tasks requiring complex clinical reasoning (Jaworski et al., 2024).

Comparisons between AI and human residents on examinations reveal significant potential for educational enhancement. In the Canadian In-Training Examination, ChatGPT-4.0 achieved a score of 88.7%, surpassing emergency medicine trainees at all postgraduate levels—the highest of whom scored 70.1% (Suwała et al., 2024). This demonstrates AI’s value as a tailored resource for learning and self-assessment.

Nevertheless, AI cannot replace the nuanced understanding and clinical judgment developed by human practitioners through years of training and experience.

The implications of the exam performance of AI extend beyond scores, offering insight into knowledge mastery. Strong performance by models suggests their effectiveness as study aids, capable of providing immediate feedback and personalized learning to help residents identify weaknesses and focus their efforts (Almehairi et al., 2025). The integration of AI into training may thus foster interactive environments for practice and revision, ultimately enhancing exam preparedness.

In conclusion, AI models such as ChatGPT demonstrate significant potential to enhance medical education and assessment. Although they have outperformed human examinees in certain contexts, their integration must be approached with caution. AI should serve as a complementary resource within traditional educational frameworks—not as a replacement for human expertise and judgment.

Further research remains necessary to examine the long-term impact of AI in medical training and to develop methods that effectively leverage the strengths of both AI and human educators (see Figure 1).

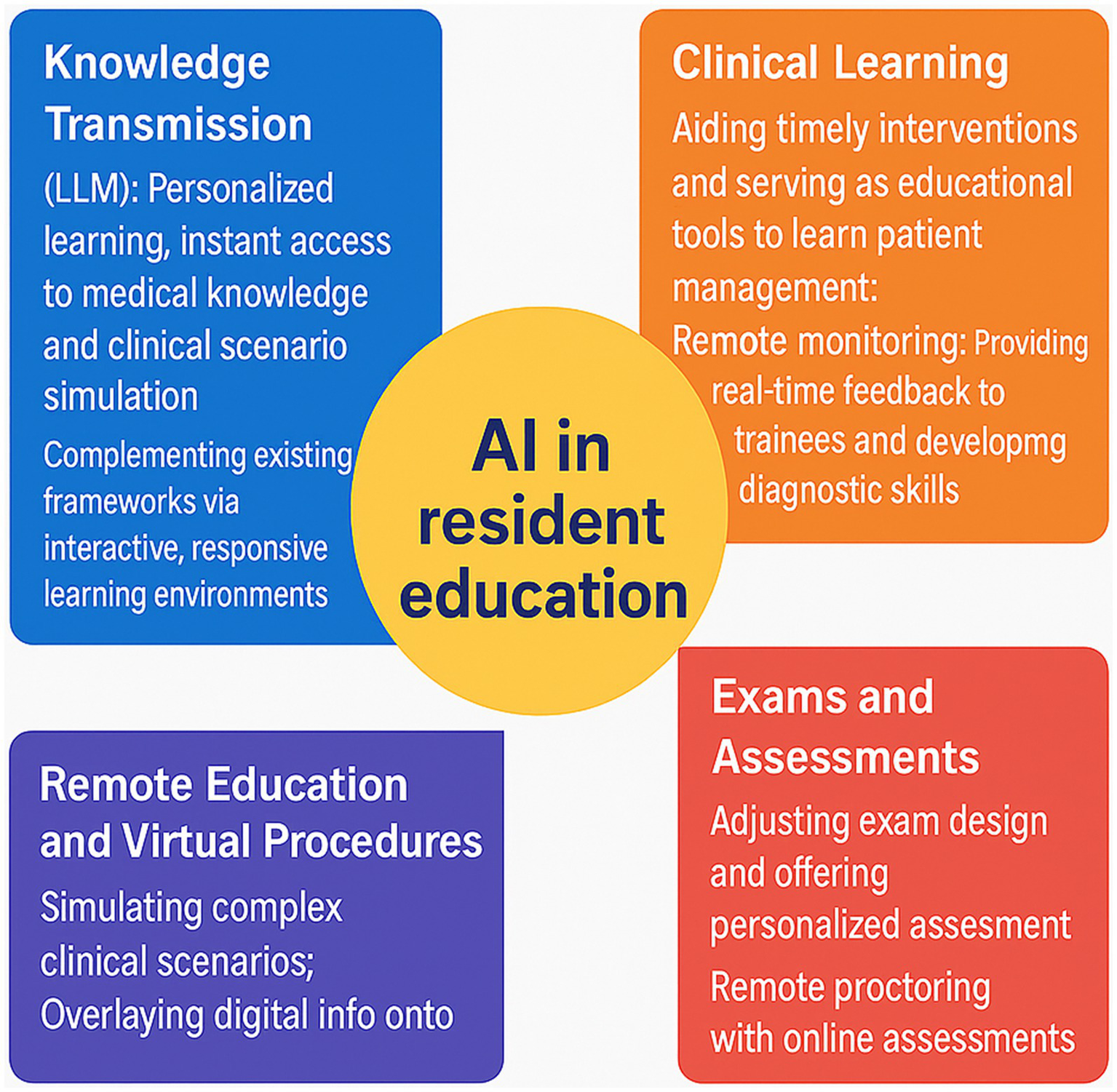

Figure 1

The role of artificial intelligence in medical residency training.

4.2 AI-assisted exam design and remote proctoring

The integration of AI is transforming the design and administration of medical exams for residency training. It encompasses areas such as question bank generation, intelligent scoring, and academic integrity monitoring, all aimed at enhancing the assessment process. Current trends show a growing reliance on AI tools to develop diverse, adaptive question banks that align closely with curricular learning objectives. AI systems analyze extensive educational content to generate questions that assess knowledge, critical thinking, and problem-solving—skills essential for future physicians. By adapting in real time and adjusting difficulty according to examinee performance, these systems enable a personalized approach to assessment that extends beyond traditional methods.

AI-driven intelligent scoring streamlines the grading process, reducing faculty workload while maintaining accuracy and fairness. Machine learning algorithms can assess resident responses and provide immediate feedback, which is crucial for ongoing skill development. By analyzing response patterns, these systems also help identify areas of common misunderstanding, enabling educators to implement targeted improvements in teaching (Gencer and Gencer, 2024). This continuous feedback loop not only enhances individual learning but also supports the ongoing relevance and effectiveness of the curriculum.

AI plays a key role in upholding academic integrity through remote proctoring, especially as online assessments become more common. These monitoring systems utilize facial recognition, behavior analysis, and environmental scanning to detect suspicious activities that may indicate cheating (Cotobal Rodeles et al., 2024). By safeguarding the credibility of high-stakes medical exams, AI helps preserve the value of certification and licensure. Furthermore, secure remote proctoring expands access to quality education for residents across diverse geographical locations, supporting flexible and equitable training opportunities.

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain. Issues such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the risk of over-reliance on technology must be addressed to ensure equitable and fair assessments. Sustained dialogue among educators, technologists, and policymakers is essential to establish clear guidelines for the responsible use of AI in medical education (Robbin et al., 2025). Ultimately, balancing technological innovation with ethical considerations will be key to enhancing the education of future physicians.

In conclusion, the integration of AI into exam design and remote proctoring is shifting medical education toward more efficient, personalized, and secure assessment practices. By revolutionizing examinations, AI has the potential to improve both learning outcomes and academic integrity. To fully harness these capabilities while addressing implementation challenges, ongoing research and interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential in residency training.

5 AI education content design and curriculum development

5.1 AI-related core knowledge and skills framework

The integration of AI into medical education requires a structured curriculum framework. This framework should combine foundational knowledge in machine learning and data science with practical clinical applications, in order to develop the AI competencies needed for effective practice. A postgraduate family medicine study outlined five core curriculum elements—need, purpose, objectives, content, and organization/implementation—which provide a systematic approach for integrating AI training and addressing the growing need for physician AI fluency (Tolentino et al., 2025). Teaching should blend theoretical concepts with hands-on clinical applications, such as AI-assisted diagnostics, patient management tools, and predictive analytics. This approach helps learners understand the practical roles AI plays in modern medicine and prepares them for its thoughtful use in clinical settings.

AI training must be tailored to specific medical specialties. For example, ophthalmology residency programs have implemented AI-driven frameworks that personalize training through deep learning models. These models allocate clinical cases based on individual resident performance and learning history, thereby improving educational outcomes and ensuring exposure to relevant, specialty-specific scenarios (Muntean et al., 2023). Furthermore, AI tools can help address clinical uncertainty by enhancing data collection and analysis to support decision-making (Alli et al., 2024). It is therefore essential for residency programs to align AI education with the distinct requirements of each specialty. Doing so ensures that trainees achieve mastery of both the technologies and their practical clinical applications.

Post-pandemic medical education increasingly emphasizes technology-integrated teaching. The shift toward online learning and competency-based models has accelerated the integration of AI (Lewandrowski et al., 2023). Web-based platforms now offer interactive clinical reasoning training, delivering real-time feedback and adaptive learning pathways to create more engaging educational environments. To fully realize the personalized learning potential of AI, adaptable frameworks for core medical knowledge must be developed alongside these technological tools.

In conclusion, robust AI curricula are essential for resident training across all specialties. By focusing on foundational knowledge, practical application, and specialty-tailored approaches, these programs prepare physicians for modern healthcare. Ongoing research into effective educational frameworks will help ensure clinicians master relevant AI technologies, ultimately enhancing patient care.

5.2 Comparison of curriculum implementation models

AI education within residency programs is commonly delivered through either long-term lecture series or short-term workshops. This was evaluated in the AI-RADS curriculum, which compared a 7-month lecture series with a 1-day workshop. The long-term series, consisting of bi-weekly lectures and journal clubs, achieved a satisfaction score of 9.8/10. Participants demonstrated progressive improvement in their understanding of AI concepts across sessions (Lindqwister et al., 2022). The short-term workshop also performed well, scoring 4.3/5 and increasing participants’ perceived comprehension. These findings indicate that both formats are effective, though the extended lecture series may support deeper and more gradual learning for AI beginners, enabling more sustained knowledge assimilation.

Blended learning, which combines online and in-person instruction, is increasingly regarded as a best practice in AI education. It offers the flexibility of self-paced learning while retaining the value of face-to-face interaction. Online resources effectively supplement traditional teaching, supporting the review of complex topics and enabling interactive formats such as virtual simulations and case discussions.

The AIFM-ed family medicine framework, for example, combined structured online content with hands-on training, which enhanced learning and prepared residents for an AI-integrated healthcare environment. To maximize outcomes, blended learning requires careful instructional design that meaningfully connects online and in-person components. This approach equips future physicians with the necessary AI-related clinical skills.

6 The educational value of AI in clinical decision support

6.1 AI-assisted clinical decision-making training

AI enhances resident training through the use of decision support systems and simulations. For example, Aifred—a clinical decision support system (CDSS)—applies artificial intelligence to assist physicians in selecting treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD). By analyzing patient characteristics, Aifred estimates the probability of remission for different treatment options, and in one evaluation, 60% of 20 psychiatrists found it useful for guiding treatment selection and predicting outcomes (Tanguay-Sela et al., 2022). Additional studies involving ChatGPT-4.0 revealed that while specialists still outperformed AI in diagnostic accuracy, the AI provided more comprehensive clinical responses than residents did. This suggests AI can effectively supplement trainee clinical reasoning during the learning process.

AI simulations enhance skill training by creating dynamic learning environments. For instance, compared to traditional methods, AI-supported history-taking exercises increase engagement through adaptive pacing and real-time feedback.

While tools like ChatGPT can aid clinical decision-making, overreliance on AI may reduce opportunities for critical thinking development (Jeyaraman et al., 2023). Therefore, balancing AI-based methods with traditional educational approaches remains essential to foster robust clinical reasoning.

6.2 Cultivating AI literacy and critical thinking

As AI becomes increasingly integrated into medicine, residents must develop the ability to critically evaluate AI-generated medical information. This includes understanding its inherent limitations and potential biases, which can influence clinical decisions. Tools like ChatGPT, while valuable for rapid knowledge access and scenario generation, carry a risk of disseminating inaccuracies (Kuchyn et al., 2024). Residents therefore need training to assess the quality of AI output. They should recognize these tools as supplementary aids, not infallible replacements for human expertise, and verify AI-generated suggestions against established clinical guidelines. Moreover, because AI models can be trained on biased datasets, education should include the ethical implications for healthcare equity (Schwartzstein, 2024). Equipping residents with robust evaluation frameworks will empower them to make informed, patient-safe decisions in an AI-augmented clinical environment.

Data privacy and security represent critical priorities in AI education. Residents require training in the ethical use of data, covering principles such as informed consent and confidentiality, as well as awareness of potential legal consequences. Over-reliance on AI also poses a risk of eroding trainees’ critical thinking skills (Berbenyuk et al., 2024). Integrating AI literacy with deliberate critical-thinking instruction addresses the evolving needs of modern healthcare. Residency programs should prioritize these competencies to adequately prepare physicians for safe and effective practice in an AI-driven clinical environment.

7 Challenges and limitations of AI technology in residency education

7.1 Limitations of technology and delays in knowledge updates

The integration of AI into medical education and residency training presents significant opportunities, yet it also has clear limitations. While current AI models can process vast amounts of data and generate useful insights, they lack the nuanced understanding that comes from years of clinical experience. This is particularly evident in advanced, specialized areas of medicine.

Additionally, the rapid evolution of medical knowledge poses a challenge for AI systems, which typically rely on static, non-real-time databases. As a result, the knowledge imparted by AI may not always align with the latest clinical guidelines or best practices. This misalignment could potentially compromise the quality of resident training if not carefully addressed (Cotobal Rodeles et al., 2024).

In addition to limits in advanced clinical knowledge, AI knowledge bases are often slow to update and may not reflect current medical practices. Medicine continuously evolves with new research, treatments, and guidelines, but AI systems can lag in incorporating these changes, potentially exposing trainees to outdated information. This delay is especially critical in fast-advancing specialties such as oncology and cardiology, where timely, evidence-based practice is essential (Smith and Vendrame, 2023). Furthermore, traditional educational models that emphasize rote memorization are poorly suited to address the complexities AI aims to support. Consequently, educational frameworks must be redesigned to thoughtfully integrate AI-assisted learning with hands-on experiential training (Lindqwister et al., 2022).

The absence of standardized AI education underscores the need for a cohesive framework that ensures all trainees receive adequate and consistent exposure to AI concepts. As AI becomes further embedded in medical education, proactively addressing these limitations, including delays in knowledge updates, will be vital to maximizing its benefits for future healthcare professionals (Yılmaz et al., 2023).

7.2 Insufficient educational resources and faculty training

The integration of AI into medical education, particularly in residency training, faces significant barriers. These include a shortage of specialized AI courses and a lack of faculty equipped to teach them. Although AI plays an increasingly important role in healthcare, particularly in areas such as diagnostic imaging and clinical decision-making, most residency programs still lack formal curricula that cover AI concepts, tools, and medical applications.

Studies show that while medical professionals are generally aware of AI, many lack practical knowledge. For instance, few residents report having received any formal AI training (Xu et al., 2024). Compounding this issue, faculty themselves often lack adequate training in AI, which further limits the exposure of residents and hinders the effective clinical use of these technologies. Therefore, institutions must prioritize developing structured AI curricula and providing faculty with the training needed to teach AI effectively.

The limited time and energy residents can devote to learning further exacerbate these challenges. Residency training is intensely demanding, characterized by long hours and significant emotional and physical burdens. This leaves little capacity for mastering complex AI concepts, which often require both medical and technical foundations. Additionally, many residents enter training without prior exposure to computer science or data analytics (Lindqwister et al., 2022). Under such time constraints and cognitive load, engagement with AI education may diminish, perpetuating the underutilization of these tools.

Current AI education in residency programs thus faces several key obstacles: a scarcity of specialized courses, insufficiently prepared faculty, and the constrained learning capacity of trainees. To move forward, institutions must prioritize the development of structured AI curricula and invest in faculty training. Doing so is essential to equip future physicians with the AI competencies needed for modern healthcare.

8 Ethical, legal, and regulatory issues in AI education

8.1 Data privacy and security risks

The integration of AI into medical education, particularly within residency training, raises significant concerns regarding patient data protection. AI systems depend on extensive datasets, which heightens the risk of privacy breaches. In educational settings, AI tools that analyze patient data for training purposes may inadvertently expose sensitive information if not properly managed.

A study examining ethical dilemmas in AI noted that while many trainees are aware of privacy risks, some view them as justifiable under specific circumstances (Al-Ani et al., 2024). This presents a paradox: the educational advantages of AI could potentially compromise patient confidentiality. Moreover, medical students and residents often receive little formal training in data privacy, leaving them inadequately prepared to understand how AI impacts the security of personal health information.

To address this, institutions must prioritize ethical AI education that equips future healthcare providers with the knowledge and skills necessary to protect data privacy and security.

Beyond data privacy risks, regulatory frameworks play a critical role in shaping the ethical use of AI in medical education. Various jurisdictions have established guidelines governing AI in healthcare, often emphasizing informed consent, data ownership, and accountability. However, the rapid pace of AI innovation frequently outstrips regulatory updates, resulting in legal and ethical gaps. Many professionals express concern that existing rules inadequately address emerging AI challenges, such as algorithmic bias and the transparency of automated decisions (Hasan et al., 2024). As AI becomes more embedded in medical education, institutions must ensure that their curricula align with current regulations while also advocating for policies that proactively address AI ethics. Doing so will not only enhance resident education but also promote greater accountability in future clinical practice.

Therefore, medical training programs should teach both the technical aspects of AI and the ethical frameworks guiding its use. This dual focus will help cultivate ethical awareness and critical thinking, ensuring that AI ultimately enhances—rather than undermines—the quality of patient care.

8.2 Risks of AI misleading and responsibility attribution

The integration of AI into medical education, particularly within residency training, presents both significant opportunities and notable challenges. A primary concern is the risk of educational misguidance due to AI-generated inaccuracies. AI systems can produce erroneous or “careless” outputs, disseminating incorrect medical information that may undermine resident training. For instance, a recent study highlighted that AI models, including certain chatbots, may generate responses that appear plausible but are factually inaccurate, potentially misleading trainees (Wachter et al., 2024). Such errors could lead residents to misunderstand clinical practices or treatments, ultimately affecting patient care. In severe cases, reliance on flawed AI content could contribute to inappropriate clinical decisions and compromise patient safety. Therefore, institutions must establish robust oversight mechanisms. These should include regular auditing of AI outputs, mandatory review by human experts, and clear guidelines governing the appropriate use of AI in educational settings.

Responsibility within AI-assisted education presents another layer of complexity. Both residents and institutions may face legal and ethical implications when relying on AI-generated content. If AI misinformation contributes to adverse outcomes, attributing liability becomes contentious: some may place responsibility on developers for algorithmic flaws, while others argue that practitioners should be held accountable (Wang et al., 2023). Clear guidelines and legal frameworks are therefore needed to define the respective roles and obligations of all parties involved. Residency programs must actively educate trainees about the limitations of AI, emphasizing that these tools are meant to augment—not replace—critical thinking and clinical judgment. By fostering a culture of accountability and continuous learning, programs can help ensure residents use AI safely and effectively in their practice.

In conclusion, residency programs must educate trainees on the limitations of AI, emphasizing its role as an aid to critical thinking rather than a replacement for it. Collaborative efforts among educators, developers, and regulators are needed to establish clear oversight standards. This will help ensure that AI enhances, rather than undermines, the quality of medical education.

9 Perceptions and attitudes of residents towards AI education

9.1 Differences in attitudes across regions and specialties

Physician attitudes toward AI in medical practice vary significantly by region and specialty. A study in Saudi Arabia found that while most physicians viewed AI positively, only 12.3% reported using it routinely, indicating a notable gap between perception and adoption (Sandougah et al., 2025). In contrast, a Syrian study revealed that although 70% of respondents were aware of AI, merely 23.7% understood its medical applications—a disparity that may reflect cultural or educational differences between regions (Swed et al., 2022). Experience with AI appears to influence acceptance: residents and assistant professors tend to engage more actively with the technology compared to medical undergraduates. Attitudes are also affected by professional burnout, with some stressed residents expressing concern that AI may diminish their role or threaten job security.

Ethical concerns are a significant barrier to AI acceptance. For instance, pharmacy students have expressed concerns regarding patient data privacy, risks of data hacking, and potential job displacement due to AI integration (Hasan et al., 2025). These issues can slow adoption, especially in regions with less developed regulatory frameworks. Targeted education that directly addresses these ethical considerations could help foster more positive perceptions. By understanding the distinct regional and specialty-based differences in attitudes, educators can design tailored programs that build essential AI skills while reinforcing the principle that AI should complement, rather than replace, human clinical care.

9.2 Expectations and needs of educators and residents

Educators and residents hold mixed perspectives on AI in medical education—support is often tempered by concern. While educators acknowledge AI’s potential to enhance teaching, many doubt the readiness of current programs to integrate it effectively. A common worry is that technological progress may outpace curriculum development, leaving faculty ill-equipped to guide trainees.

A study in medical genetics highlighted this disconnect, revealing a gap between the perceived importance of AI and comfort of educators in applying it, which suggests many feel underprepared to teach AI-related content (French et al., 2023). Educators also emphasize the need to incorporate ethical training, particularly in areas such as patient safety and data privacy, into AI education.

Residents express a strong preference for practical AI education. While they recognize the potential benefits of AI for clinical workflows, diagnosis, and patient outcomes, many report feeling unprepared due to insufficient training. A survey revealed enthusiasm for AI-enhanced education, but noted a lack of adequate learning resources (Arranz-García et al., 2025). Residents prefer interactive training formats, such as workshops, simulations, and expert-led collaborations, to effectively master the role of AI in patient care. This includes learning how to interpret AI-generated data and integrate AI-supported insights into clinical decision-making.

These dual perspectives underscore the need for structured AI curricula that address both educator preparedness and resident training demands. Collaboration among educators, AI specialists, and clinical practitioners is essential to develop adaptable and relevant programs. Equipping both educators and trainees with essential AI skills will help ensure a more innovative and patient-centered future for medical practice.

10 Future predictions of AI in medical residency training

10.1 Personalized and adaptive learning systems

The integration of AI into medical education, especially within residency training, enables the development of personalized and adaptive learning systems. These systems tailor education to the individual needs of trainees by customizing learning paths based on each resident’s style, pace, and knowledge gaps. Such personalization is particularly valuable in medicine, where required competencies can vary widely among learners.

AI also provides real-time feedback, offering residents immediate performance assessments and allowing them to adjust their learning strategies accordingly. For instance, by analyzing a resident’s interactions with educational materials, AI can generate targeted recommendations for further study or practice. This approach not only deepens understanding of complex medical concepts but also encourages greater ownership of the learning process—an essential quality for developing competent and confident healthcare professionals (Shiga et al., 2022).

Big data and learning analytics further enhance the outcomes of residency training. AI aggregates and analyzes extensive data on learner performance, identifying patterns and trends that inform instructional design and curriculum development. This data-driven approach enables educators to pinpoint areas where residents commonly struggle and to address these needs proactively.

For example, learning analytics can reveal topics that are consistently challenging, prompting educators to enrich related materials or provide additional instructional support. The insights gained from such analytics also support the continuous improvement of training programs, helping ensure that medical education remains relevant and effective for both trainees and healthcare systems.

By combining personalized learning with robust data analytics, residency programs can simultaneously improve individual learning experiences and elevate the overall quality of medical education. This integrated approach ultimately contributes to better patient care (Awuku, 2025).

AI-driven personalized and adaptive learning represents a significant advance in residency training. By customizing education through technology and leveraging data analytics to inform instruction, educators can create more effective and responsive training environments. This approach empowers residents to take greater ownership of their learning while preparing them to navigate a rapidly evolving healthcare landscape. As these technologies continue to mature, they are likely to further transform medical education, making it more efficient, engaging, and effective in developing skilled and adaptable healthcare professionals (Li et al., 2022).

10.2 Multimodal AI, real-time learning analytics, and cross-disciplinary collaborations

The future of medical residency training will be profoundly reshaped by the synergistic integration of multimodal AI, real-time learning analytics, and cross-disciplinary collaborations, addressing long-standing challenges in clinical skill acquisition, personalized training, and workflow efficiency (Saroha, 2025). Multimodal AI, which integrates visual, textual, and haptic data, will revolutionize immersive clinical simulations by generating hyper-realistic virtual patient scenarios that mimic complex pathological conditions and dynamic clinical interactions. Unlike current single-modal simulations, these advanced systems will enable residents to practice diagnostic reasoning, procedural skills, and patient communication simultaneously, with AI-driven feedback that adapts to individual performance nuances. For instance, in surgical residency, multimodal AI could combine 3D anatomical modeling, real-time motion tracking, and natural language processing to provide comprehensive guidance on surgical technique and patient counseling, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical practice.

Real-time learning analytics will further personalize residency training by leveraging continuous data collection from simulation platforms, electronic health records (EHRs), and wearable devices (Narayanan et al., 2023). AI algorithms will analyze residents’ learning behaviors, clinical decision-making patterns, and procedural proficiency in real time, generating dynamic learning dashboards that identify knowledge gaps and optimize training pathways. This data-driven approach will replace static assessment methods, allowing program directors to tailor curricula to individual needs—for example, intensifying training on high-risk, low-exposure procedures for residents who demonstrate deficiencies—and reducing the risk of skill decay through timely, targeted interventions. Additionally, real-time analytics will enhance patient safety by flagging potential errors in clinical decision-making before they impact patient care, fostering a proactive learning environment centered on continuous improvement.

Cross-disciplinary collaborations, facilitated by AI, will break down silos between medical specialties and technical fields, creating integrated training ecosystems. Collaborations between clinicians, data scientists, engineers, and educational technologists will drive the co-development of AI tools tailored to residency training needs, such as modular AI agent frameworks that support complex, iterative clinical tasks beyond the capabilities of single-turn chatbots. These partnerships will also enable the integration of AI into interprofessional education, preparing residents to work effectively with AI specialists and other healthcare professionals in interdisciplinary clinical teams (Bohler et al., 2024). Ultimately, the convergence of these AI-driven innovations will transform residency training from a time-based, standardized model to a competency-focused, adaptive system that equips future physicians with the skills to thrive in an AI-augmented healthcare landscape.

11 Conclusion

The integration of AI into residency education is transforming medical training, enhancing knowledge efficiency, personalizing learning, and supporting clinical decision-making. Current AI applications show significant promise, yet multifaceted challenges must be resolved to realize their full potential.

Substantial implementation hurdles remain. These include the technical need for algorithms trained on robust medical data, unequal access to resources that can create disparities in AI learning, and ethical concerns related to data privacy, algorithmic bias, and over-reliance on technology in clinical decisions. Additionally, regulatory frameworks for AI in medical education are still underdeveloped.

Interdisciplinary collaboration among computer scientists, medical educators, and healthcare policymakers is essential for holistic AI integration. Equally important is investment in faculty training and resource development. Educators must acquire the skills to teach AI concepts effectively, enabling residents to become critical thinkers who can evaluate the clinical utility of AI tools. This focus will improve training quality and cultivate a generation of AI-adept physicians.

In conclusion, AI in residency education offers considerable promise amid inherent complexity. By addressing existing challenges through standardization, interdisciplinary cooperation, and robust educator preparation, programs can achieve meaningful AI integration. Such progress can modernize training, improve patient outcomes, and prepare future physicians for an evolving healthcare landscape. Ultimately, success will depend on balancing the embrace of AI’s potential with vigilant attention to its ethical and practical implications in medical education.

Statements

Author contributions

HZ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. KQ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. JW: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. CZ: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication. The project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82302331, U22A20352) and the grants of National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2023YFC2413500).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Al-AniA.RayyanA.MaswadehA.SultanH.AlhammouriA.AsfourH.et al. (2024). Evaluating the understanding of the ethical and moral challenges of big data and AI among Jordanian medical students, physicians in training, and senior practitioners: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Ethics25:18. doi: 10.1186/s12910-024-01008-0,

2

AlliS. R.HossainS. Q.DasS.UpshurR. (2024). The potential of artificial intelligence tools for reducing uncertainty in medicine and directions for medical education. JMIR Med. Educ.10:e51446. doi: 10.2196/51446,

3

AlmehairiN.ClarkG.DavisS. (2025). How well does GPT-4 perform on an emergency medicine board exam? A comparative assessment. CJEM27, 969–973. doi: 10.1007/s43678-025-00951-0,

4

Arranz-GarcíaO.GarcíaM. D. R.Alonso-SecadesV. (2025). Perceptions, strategies, and challenges of teachers in the integration of artificial intelligence in primary education: a systematic review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res.24. doi: 10.28945/5458

5

AwukuM. (2025). Beyond residency: 'the imperative of lifelong learning in medical practice'. Med. Teach.47, 748–750. doi: 10.1080/0142159x.2024.2337243,

6

BerbenyukA.PowellL.ZaryN. (2024). Feasibility and educational value of clinical cases generated using large language models. Stud. Health Technol. Inform.316, 1524–1528. doi: 10.3233/shti240705,

7

BettatiPFeiB. (2023). An augmented reality system with advanced user interfaces for image-guided intervention applications. Proceedings of SPIE--the International Society for Optical Engineering12466.

8

BohlerF.AggarwalN.PetersG.TaranikantiV. (2024). Future implications of artificial intelligence in medical education. Cureus16:e51859. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51859,

9

ChangT. P.HollingerT.DolbyT.ShermanJ. M. (2021). Development and considerations for virtual reality simulations for resuscitation training and stress inoculation. Simul. Healthc.16, e219–e226. doi: 10.1097/sih.0000000000000521,

10

Cotobal RodelesS.Martín SánchezF. J.Martínez-SellesM. (2024). Characteristics of the new internal resident physicians from Madrid region, their opinions regarding family and community medicine. Semergen50:102295. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2024.102295,

11

EbelS.EhrengutC.DeneckeT.GößmannH.BeeskowA. B. (2024). GPT-4o’s competency in answering the simulated written European Board of Interventional Radiology exam compared to a medical student and experts in Germany and its ability to generate exam items on interventional radiology: a descriptive study. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof.21:21. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2024.21.21,

12

FeinmesserG.YogevD.GoldbergT.ParmetY.IllouzS.VazgovskyO.et al. (2023). Virtual reality-based training and pre-operative planning for head and neck sentinel lymph node biopsy. Am. J. Otolaryngol.44:103976. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2023.103976,

13

FinkelsteinM.LudwigK.KamathA.HaltonK. P.MendelsonD. S. (2024). The impact of an artificial intelligence certificate program on radiology resident education. Acad. Radiol.31, 4709–4714. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2024.05.041,

14

FrenchE. L.KaderL.YoungE. E.FontesJ. D. (2023). Physician perception of the importance of medical genetics and genomics in medical education and clinical practice. Med. Educ. Online28:2143920. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2022.2143920,

15

GencerG.GencerK. (2024). A comparative analysis of ChatGPT and medical faculty graduates in medical specialization exams: uncovering the potential of artificial intelligence in medical education. Cureus16:e66517. doi: 10.7759/cureus.66517,

16

HasanH. E.JaberD.KhabourO. F.AlzoubiK. H. (2024). Perspectives of pharmacy students on ethical issues related to artificial intelligence: a comprehensive survey study. Res. Square. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-4302115/v1

17

HasanH. E.JaberD.KhabourO. F.AlzoubiK. H. (2025). Pharmacy students' perceptions of artificial intelligence integration in pharmacy practice: ethical challenges in multiple countries of the MENA region. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn.17:102397. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2025.102397,

18

HuR.RizwanA.HuZ.LiT.ChungA. D.KwanB. Y. M. (2023). An artificial intelligence training workshop for diagnostic radiology residents. Radiol. Artif. Intell.5:e220170. doi: 10.1148/ryai.220170,

19

JaworskiA.JasińskiD.JaworskiW.HopA.JanekA.SławińskaB.et al. (2024). Comparison of the performance of artificial intelligence versus medical professionals in the polish final medical examination. Cureus16:e66011. doi: 10.7759/cureus.66011,

20

JeyaramanM.KS. P.JeyaramanN.NallakumarasamyA.YadavS.BondiliS. K. (2023). ChatGPT in medical education and research: a boon or a bane?Cureus15:e44316. doi: 10.7759/cureus.44316,

21

KuchynI. L.LymarL. V.BielkaK. Y.StorozhukK. V.KolomiietsT. V. (2024). New training, new attitudes: non-clinical components in Ukrainian medical PHDs training (regarding critical thinking, academic integrity and artificial intelligence use). Wiad. Lek.77, 665–669. doi: 10.36740/WLek202404108,

22

LewandrowskiK. U.ElfarJ. C.LiZ. M.BurkhardtB. W.LorioM. P.WinklerP. A.et al. (2023). The changing environment in postgraduate education in orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery and its impact on technology-driven targeted interventional and surgical pain management: perspectives from Europe, Latin America, Asia, and the United States. J. Pers. Med.13. doi: 10.3390/jpm13050852,

23

LiL.RayJ. M.BathgateM.KulpW.CronJ.HuotS. J.et al. (2022). Implementation of simulation-based health systems science modules for resident physicians. BMC Med. Educ.22:584. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03627-w,

24

LindqwisterA. L.HassanpourS.LevyJ.SinJ. M. (2022). AI-RADS: successes and challenges of a novel artificial intelligence curriculum for radiologists across different delivery formats. Front. Med. Technol.4:1007708. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2022.1007708,

25

MoroskyC. M.Baecher-LindL.ChenK. T.FlemingA.SimsS. M.MorganH. K.et al. (2025). Practical applications of artificial intelligence chatbots in obstetrics and gynecology medical education. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.233, 4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2025.04.021,

26

MuY.YangX.GuoF.YeG.LuY.ZhangY.et al. (2024). Colonoscopy training on virtual-reality simulators or physical model simulators: a randomized controlled trial. J. Surg. Educ.81, 1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2024.07.020,

27

MunteanG. A.GrozaA.MargineanA.SlavescuR. R.SteiuM. G.MunteanV.et al. (2023). Artificial intelligence for personalised ophthalmology residency training. J. Clin. Med.12:1825. doi: 10.3390/jcm12051825,

28

NahmW. J.SohailN.BurshteinJ.GoldustM.TsoukasM. (2025). Artificial intelligence in dermatology: a comprehensive review of approved applications, clinical implementation, and future directions. Int. J. Dermatol.64, 1568–1583. doi: 10.1111/ijd.17847,

29

NarayananS.RamakrishnanR.DurairajE.DasA. (2023). Artificial intelligence revolutionizing the field of medical education. Cureus15:e49604. doi: 10.7759/cureus.49604,

30

OgundiyaO.RahmanT. J.Valnarov-BoulterI.YoungT. M. (2024). Looking Back on digital medical education over the last 25 years and looking to the future: narrative review. J. Med. Internet Res.26:e60312. doi: 10.2196/60312,

31

PuJ.HongJ.YuQ.YuP.TianJ.HeY.et al. (2025). Accuracy, satisfaction, and impact of custom GPT in acquiring clinical knowledge: potential for AI-assisted medical education. Med. Teach.47, 1502–1508. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2025.2458808,

32

QianX.JingyingH.XianS.YuqingZ.LiliW.BaoruiC.et al. (2022). The effectiveness of artificial intelligence-based automated grading and training system in education of manual detection of diabetic retinopathy. Front. Public Health10:1025271. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1025271,

33

RalevskiA.TaiyabN.NossalM.MicoL.PiekosS. N.HadlockJ. (2024). Using large language models to annotate complex cases of social determinants of health in longitudinal clinical records. medRxiv27:24306380. doi: 10.1101/2024.04.25.24306380,

34

RobbinM. L.FetzerD. T.TesslerF. N.ChongW. K.LockhartM. E. (2025). Achieving and maintaining excellence: a roadmap for ultrasound practices. Radiol. Clin. North Am.63, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2024.07.007,

35

SandougahK.AlsywinaN.AlghamdiH. K.AlrobayanF.AlshaghathirahF. M.AlomranK. (2025). Assessment of the knowledge, attitude, and practice of artificial intelligence (AI) among radiologists, physicians, and surgeons in Saudi Arabia. Cureus17:e79180. doi: 10.7759/cureus.79180,

36

SarohaS. (2025). Artificial intelligence in medical education: promise, pitfalls, and practical pathways. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract.16, 1039–1046. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S523255,

37

SchwartzsteinR. M. (2024). Clinical reasoning and artificial intelligence: can AI really think?Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc.134, 133–145.

38

ShigaT.HifumiT.HagiwaraY.OtaniN.TanakaH.NakanoM.et al. (2022). Career satisfaction among acute care resident physicians in Japan. Acute Med. Surg.9:e779. doi: 10.1002/ams2.779,

39

SmithC. M.VendrameM. (2023). Perspective: a resident's role in promoting safe machine-learning tools in sleep medicine. J. Clin. Sleep Med.19, 1985–1987. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.10724,

40

SuwałaS.SzulcP.GuzowskiC.KamińskaB.DorobiałaJ.WojciechowskaK.et al. (2024). ChatGPT-3.5 passes Poland's medical final examination-is it possible for ChatGPT to become a doctor in Poland?SAGE Open Med.12:20503121241257777. doi: 10.1177/20503121241257777,

41

SwedS.AlibrahimH.ElkalagiN. K. H.NasifM. N.RaisM. A.NashwanA. J.et al. (2022). Knowledge, attitude, and practice of artificial intelligence among doctors and medical students in Syria: a cross-sectional online survey. Front. Artif. Intell.5:1011524. doi: 10.3389/frai.2022.1011524,

42

Tanguay-SelaM.BenrimohD.PopescuC.PerezT.RollinsC.SnookE.et al. (2022). Evaluating the perceived utility of an artificial intelligence-powered clinical decision support system for depression treatment using a simulation center. Psychiatry Res.308:114336. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114336,

43

TolentinoR.Hersson-EderyF.YaffeM.Abbasgholizadeh-RahimiS. (2025). AIFM-ed curriculum framework for postgraduate family medicine education on artificial intelligence: mixed methods study. JMIR Med. Educ.11:e66828. doi: 10.2196/66828,

44

WachterS.MittelstadtB.RussellC. (2024). Do large language models have a legal duty to tell the truth?R. Soc. Open Sci.11:240197. doi: 10.1098/rsos.240197,

45

WangC.LiuS.YangH.GuoJ.WuY.LiuJ. (2023). Ethical considerations of using ChatGPT in health care. J. Med. Internet Res.25:e48009. doi: 10.2196/48009,

46

XuY.JiangZ.TingD. S. W.KowA. W. C.BelloF.CarJ.et al. (2024). Medical education and physician training in the era of artificial intelligence. Singapore Med. J.65, 159–166. doi: 10.4103/singaporemedj.SMJ-2023-203,

47

YılmazT.CeyhanŞ.AkyönŞ. H.YılmazT. E. (2023). Enhancing primary Care for Nursing Home Patients with an artificial intelligence-aided rational drug use web assistant. J. Clin. Med.12. doi: 10.3390/jcm12206549,

48

ZechJ. R.EzumaC. O.PatelS.EdwardsC. R.PosnerR.HannonE.et al. (2024). Artificial intelligence improves resident detection of pediatric and young adult upper extremity fractures. Skeletal Radiol.53, 2643–2651. doi: 10.1007/s00256-024-04698-0,

Summary

Keywords

AI-assisted learning, artificial intelligence, clinical decision support, innovative educational models, residency education

Citation

Zhang H, Qian K, Wang J and Zheng C (2026) The current status and future prospects of artificial intelligence education in residency training. Front. Educ. 10:1713676. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1713676

Received

26 September 2025

Revised

16 December 2025

Accepted

25 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Maha Khemaja, University of Sousse, Tunisia

Reviewed by

Ting Wang, American Board of Family Medicine, United States

Shuai Wang, Southern Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zhang, Qian, Wang and Zheng.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jing Wang, xhwangjing@hust.edu.cn; Chuansheng Zheng, hqzcsxh@sina.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

ORCID: Hongsen Zhang, orcid.org/0000-0003-1962-5310; Kun Qian, orcid.org/0000-0002-5944-8227; Jing Wang, orcid.org/0000-0001-7223-2909; Chuansheng Zheng, orcid.org/0000-0002-2435-1417

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.