Abstract

Introduction:

Researchers examined the effectiveness of a digital mapping project created in partnership with librarians for a history course. The project centered on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the 1948 war, aiming to improve students’ understanding of historical context while developing transferable skills such as critical thinking, research, and technological literacy. This initiative reflects broader trends in higher education that emphasize skill development and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Methods:

To evaluate the project’s impact, a mixed-methods approach was used. Data collection involved pre- and post-surveys and analysis of course assignments. The sample included 17 undergraduate students enrolled in a history course, representing diverse majors such as History, Political Science, and Education. All enrolled students participated, with no exclusion criteria applied.

Results:

Findings show that the digital mapping project greatly enhanced students’ understanding of the historical context, helped develop valuable skills, and boosted engagement compared to traditional assignments. Students’ responses were mainly positive, providing useful feedback for future projects and emphasizing the potential of digital tools in college education.

Discussion:

The results indicate that integrating digital humanities into history courses can create engaging learning experiences and encourage deeper student involvement. These findings add to the growing evidence supporting the use of digital tools in humanities education. However, limitations include the small sample size and dependence on self-reported data, which may impact the ability to generalize the results.

Introduction

Integrating digital tools into educational settings has emerged as a promising strategy for enhancing student engagement and improving learning outcomes. This study examines the implementation of a digital mapping assignment in a history course, with a focus on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the 1948 war. Students were tasked with using mapping software to compare historical maps and analyze changes in specific locations following the war.

Beyond its educational benefits on the topic discussed, this assignment aimed to equip students with transferable skills, including critical thinking, research proficiency, and technological literacy. By incorporating digital humanities into the curriculum, the project sought to prepare students for the challenges of the modern world.

The assignment was designed as part of the Libraries’ Sprints program and constituted a collaborative effort between the course instructor and librarians. This program pairs faculty applicants with a team of librarians who work together on a teaching or research project for one week. This partnership highlights the project’s interdisciplinary nature, demonstrating how it can bridge diverse academic disciplines. Students were encouraged to engage with course material more dynamically and interactively, using digital mapping tools to deepen their understanding of historical events and data. The project aimed to evaluate students’ ability to succeed within the new assignment parameters, assess how the assignment aligns with their other coursework, and understand their expectations for applying the skills learned in the course. The findings are based on pre- and post-surveys, as well as an analysis of students’ assignments.

This study aims to further explore the impact of such assignments on content comprehension and student engagement by assessing student perceptions, evaluating learning outcomes, and identifying how the acquired skills can be applied in other academic or professional contexts. The findings will contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the integration of digital tools in education, particularly within the humanities (Tracy and Hoiem, 2017). This study expands on these trends by exploring how a digital mapping assignment can accomplish these objectives.

Digital mapping tools like Google Earth Pro and ArcGIS are well-known for enhancing spatial literacy and historical understanding by helping students visualize geographic changes over time (Knowles and Amy, 2008; Schindler, 2016; McGinn and Duever, 2018). These tools promote active learning by engaging students in interactive tasks that emphasize analysis and interpretation rather than passive memorization (Mostern and Gainor, 2013). Beyond history education, Google Earth Pro has been effectively applied in various areas, including disaster mitigation and adaptation learning, where its visual and interactive features foster more profound understanding and problem-solving skills (Suharini et al., 2020). Similarly, integrating Google Earth Pro into physical geography courses improves conceptual understanding and technological skills among pedagogy students (Duong, 2024). In library and academic settings, Google Earth and Google Maps are used to support research and information literacy, showing their versatility as educational tools (Dodsworth and Nicholson, 2012).

The goal of this study is to assess the impact of a digital mapping assignment on student learning, engagement, and transferable skills. Specifically, the research explores the following questions:

-

(1)

How does the digital mapping assignment impact students’ understanding of historical content?

-

(2)

How does it improve engagement compared to traditional assignments?

-

(3)

What transferable skills do students report gaining from this digital mapping assignment?

Theoretical framework/literature review

Higher education is a crucial pillar of society; however, recent discussions have raised questions about its purpose and value. The acquisition of skill sets, transferability, and meeting what employers value most are viewed as primary outcomes. This sentiment of seeing higher education as “student-centered” means, in this context, focusing on the need to situate the experience as continuous, from pre-entry expectations and preparation to the anticipation of higher education outcomes, including employment (Assiter, 2017).

There are ambiguities in defining transferable skills (Olesen et al., 2021). Such skills may vary among BA programs (Allan et al., 1995). Some of these skills include personal development, leadership, learning how to learn, communication (both written and oral), working with others, critical thinking, problem-solving, research, numeracy, and the use of information technology (Washer, 2007; Alsaleh, 2020; Elmuti et al., 2005). Examples of how higher education institutions can provide frameworks for students to acquire transferable skills include extracurricular activities, such as participation in clubs and societies (Eccles et al., 2003), or a requirement for a year abroad in modern language degree programs, which enhances cultural awareness and adaptability (Taylor, 1995). Another example is the integration of digital tools into coursework, such as using digital mapping software in history classes to develop technological literacy and critical thinking skills (Knowles and Amy, 2008; Schindler, 2016). Additionally, capstone projects that require students to apply theoretical knowledge to practical, real-world problems also foster transferable skills (Hauhart and Grahe, 2014). This is primarily achieved through research, problem-solving, and collaboration. In this study, transferable skills are abilities that can be directly applied in both academic and professional environments. These include critical thinking, research skills, technological literacy, and team-based problem-solving.

Previous research has consistently demonstrated the positive impact of digital tools on student learning outcomes. Bodenhamer et al. (2010) and Knowles and Amy (2008) highlight the potential of these tools to foster technological literacy, critical thinking skills, and engagement with course material. This study aligns with the broader literature advocating for innovative pedagogical approaches beyond traditional methods (Kuh, 2008). Interdisciplinary collaboration has been identified as a crucial component of effective learning (Henscheid, 2000), and our project underscores its importance by requiring students to use digital tools. Traditional educational methods often prioritize memorization over critical thinking and problem-solving, whereas this study demonstrates the potential of digital assignments to promote more active and engaging forms of learning. Students engaged in problem-solving, research, and critical analysis echoed previous research, which identified these skills as essential outcomes of high-impact educational practices (Choi, 2004).

The Sprints program, as described in greater detail in previous publications (Lach and Rosenblum, 2018; Wiggins et al., 2019), is a library initiative that pairs faculty applicants with a team of librarians for an intensive week of focused work to advance research or teaching projects. Such programs typically conduct regular assessments following a sprint week, evaluating overall satisfaction among both library teams and faculty participants. Faculty sprinters have also been interviewed years later to assess the long-term impact of Sprint participation, discovering that the program fosters scholarly outputs, skills, and personal and professional connections across campus. This long-term impact highlights the enduring value and benefits of our research to the academic community (McBurney et al., 2024).

More generally, there are additional examples of pedagogical collaborations between librarians and faculty, particularly in humanities disciplines. These collaborations introduce more perspectives, experiences, and ideas that can create broader interpretations of what a research assignment can be, including a wider variety of information source types (Murphy, 2019; Wishkoski et al., 2019), increased complexity (Murgu et al., 2021; Wishkoski et al., 2019), and the involvement of students as full participants and designers of the course direction (Murgu et al., 2021; Wishkoski et al., 2019). Further collaboration on teaching in general, and on assignment design in particular, could foster greater student engagement and improve student learning outcomes.

The field of digital humanities offers a lens through which assignment design can yield favorable student learning outcomes and foster fruitful collaborations between librarians and teaching faculty. The spirit of experimentation, the collaborative relationships that can emerge outside traditional knowledge hierarchies, the project-based nature common to most digital humanities outcomes, and the various practical methods of soliciting peer feedback have all been associated with digital humanities work (Bello et al., 2017; Draxler et al., 2012; Fyfe, 2018).

Because most learners are not experts in digital humanities methods and are learning technology as they absorb course material, they can engage more effectively with the materials metacognitively (Fyfe, 2018). This reflexive practice prompts students to reflect on their learning approaches and encourages instructors to model a “transferable project-based model of instruction” (Fyfe, 2018). This practice enables students to develop transferable skills that extend beyond disciplinary content into critical thinking, problem-solving, and other cognitive skills valued by potential employers.

Maps are particularly effective for student-created digital humanities projects. By engaging with historical data in innovative ways through map-based projects (Mostern and Gainor, 2013), learners exhibit greater engagement, enhanced geographic literacy, and a fresh approach to interacting with course material compared to traditionally assigned writing projects (Manke, 2022; Warren, 2016).

This project is well-suited for disciplinary redesign. In Jewish Studies, Israel Studies, Palestine Studies, Middle Eastern Studies, and related fields, instructors have effectively used digital humanities to engage students with the material in innovative ways. They challenge students to grapple with issues such as working with texts in another language and analyzing content related to contested land. Zaagsma (2018) demonstrates how digital humanities projects can introduce students to the critical task of developing solutions for retrieving and analyzing information from dispersed multilingual sources. He raises the critical question of which parts of Jewish heritage are digitized and which stories about the Jewish past can—and cannot—be told using these digital resources. Other projects have also involved working with maps related to Israel and Palestine while documenting all localities in the region (Kokin, 2022). Another example involves digital story mapping to survey how the memory-place relationship is constructed in relation to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict (Özyeşilpınar and Beltran, 2022).

Building on this review, previous research shows that digital tools increase engagement and technological literacy. However, few studies have examined their effects on transferable skills in history courses, especially those focusing on complex topics such as the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. This study fills that gap by investigating how a digital mapping assignment influences students’ development of transferable skills alongside their understanding of content.

Methodology

This study focused on the course taught in the spring 2024 semester. Investigators surveyed students and utilized course assignments to evaluate the effectiveness of the primary assignment, which had been revised through collaboration between the course instructor and a team of librarians in spring 2022.

The changes in the course focused on transforming the manual mapping assignment using PowerPoint into digital mapping using Google Earth Pro (See Supplementary Appendix 1). Each student concentrated on one map sheet of Palestine/Israel and overlaid a map of British Mandatory Palestine from the 1940s, followed by a map of Israel from the 1950s. This enabled students to visually compare the changes before and after the 1948 war. Additionally, students used secondary sources, such as Khalidi (1992), alongside primary sources on demographic data, including those from The Government of Mandatory Palestine (1945) and the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (2019). Students developed their final project as a scaffolded undertaking, making weekly progress, sharing it with peers, and receiving feedback from the instructor.

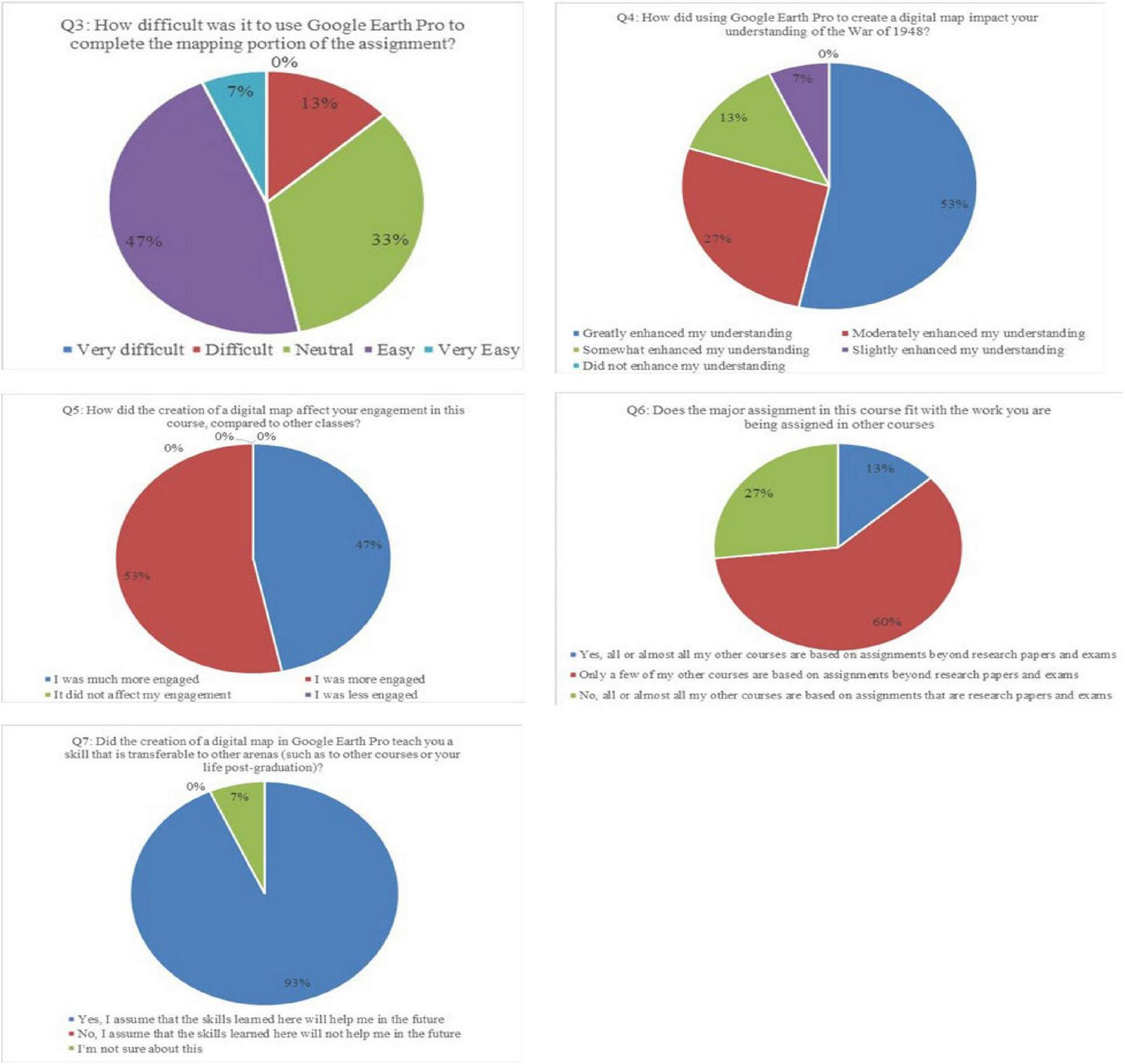

The two researchers who were not affiliated with the course distributed the surveys after a class period while the course instructor was out of the room. The pre-assignment survey was conducted during the fourth week of spring classes, and the post-assignment survey was administered in the fifteenth week of classes. Students completed the surveys on paper and later entered the anonymized responses into a shared spreadsheet for the research team. Closed-ended survey responses were tabulated, and the findings were presented in charts in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Results from the post-survey. N = 15.

Research design, sample, and procedure

This study used a single-group pre–post mixed-methods design. Quantitative data were gathered through pre- and post-assignment surveys, while qualitative data comprised student reflections embedded in scaffolded assignments throughout the semester. Data was compiled and examined using Microsoft Excel.

The sample included 17 undergraduate students enrolled in the course (n = 17), of whom 15 completed both pre- and/or post-surveys (n = 15). The class included nine males and eight females, with students aged 18–22, spanning from first to fourth year in college. All enrolled students were eligible to participate; no exclusion criteria were applied. Although survey analyses reflect n = 15 respondents, assignment-based analyses include all students (17). The survey questions are listed in Supplementary Appendices 4, 5.

Qualitative reflections were collected at four points: Week 7 (peer review, part 1), Week 8 (difficulty/question post), Week 11 (peer review, part 2), and Week 16 (final map project). The instructor employed detailed prompts and rubrics to guide students’ work on each assignment (see examples in Supplementary Appendices 2, 3). The course instructor evaluated the effectiveness of students’ work using the rubrics provided for grading.

Quantitative data analysis focused on survey data. They were summarized with descriptive statistics. A table of pre- and post-distributions for each closed-ended item is included as Supplementary Tables 1, 2, supplementing the visualization shown in Figure 1. Qualitative data analysis was conducted using an open-coding approach; two researchers independently coded the reflective responses, created a preliminary codebook, and reconciled the codes through discussion. Initial codes (e.g., curiosity, locational context, technology frustrations, maps as authored artifacts, discrepant sources, overlay reveals change) were grouped into five themes: (1) curiosity; (2) importance of location to historical events; (3) challenges; (4) maps provide limited evidence/maps are not facts; and (5) mapping/mapping software reveals interesting insights. Sample quotations and theme frequencies are provided to show relevance. Intercoder agreement was assessed via consensus; statistics are not reported due to the brief and varied responses. Joint analysis connected higher engagement ratings to themes of curiosity and metacognitive discussion of mapping choices; similarly, students’ reports of skill development matched reflections on source triangulation and the critical reading of maps as authored artifacts.

Our mixed-methods approach to this research is based on established scholarship. For open coding, we followed the process outlined by Khandkar (2009). For pre- and post-surveys of a single group, as in our case, we adhered to studies by McClurg et al. (2015).

This study followed ethical research standards. Participation was voluntary, and students were informed that their responses would remain anonymous and would not impact their course grades. They had the option to opt out. Surveys were administered by researchers not affiliated with the course while the instructor was absent to reduce bias. The study was reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Findings

The complete responses to the pre-survey are listed in Supplementary Table 1, while the post-survey results are in Supplementary Table 2. The students represented a diverse range of disciplines, with seven majoring in History, three in Secondary Education, and the remaining five in Political Science, Accounting, Behavioral Neuroscience, Global and International Studies, and Jewish Studies. An additional student, who participated in the post-survey but not in the pre-survey, indicated that their major area of study was Anthropology. One student was a first-year, five were in their second year, eight were in their third year, and one was in their fourth year.

Coding of the students’ assignments

Throughout the semester, students were asked to engage with their peers’ work at specific moments during the project. These reflections aimed to provide peer review and enable students to reflect on and apply the lessons they have learned to their own coursework. Using the open coding method mentioned above, the researchers reviewed the writing for themes and identified several threads that ran through most of the commentary. The coding process revealed that students were engaged with the course material and the technical elements at a metacognitive level, which we suggest would not have been as clearly demonstrated outside a digital humanities project. We identified five themes from the open coding: (1) curiosity, (2) the importance of location to historical events, (3) challenges, (4) maps provide limited evidence/maps are not facts, and (5) mapping/mapping software reveals interesting things.

First, the theme of curiosity, shown by a desire to know more or conduct further research, appeared most frequently. Comments ranged from the broadly curious, e.g., “It was exciting to read through your project as our maps are so close yet have several differences at the same time. I would love to know more about life at the localities in your map sheet,” to the geographically specific: “There was also Nahlawi farm on the 1943 map sheet which does not appear on the 1954 map sheet, so I am curious to see what happened to it and the people who used to work there.”

The researchers were impressed by the level of detail in most examples. Recalling Mostern and Gainor (2013), students consistently engaged with historical data at a level of detail that would have been difficult to replicate in a research paper, given the limited availability of historical data in other research formats, according to the student researchers’ experiences. Another student noted, “This is so important to see history in real life!! I love doing online research, and with the help of Google Earth, the answers to my questions are at my fingertips, which is so amazing to see. I loved doing the work for this portion of the project and cannot wait to learn even more.” This kind of genuine enthusiasm suggests that the research skills honed over the semester might persist beyond the classroom.

Second, regarding the importance of location in historical events, students often noted how viewing a map enhanced their understanding of the context surrounding specific events. Some mentioned that certain areas remained untouched by war in a visually identifiable way: “I think it is really interesting that you have so many localities on your map that remained after the war, seeing as our maps are right next to each other, and mine is the opposite. It is cool to see how similar areas are so different!” By considering factors beyond mere proximity that may have impacted the outcomes, students engage in deeper analysis of causation and move toward critical thinking, as demonstrated in their final project output.

Similarly, students were able to identify situations where the map provided little information, noting, “One difficulty I had while preparing the map sheet was the fact that most of it was a sea, so I didn’t have that many localities. Moreover, the ones that I did find didn’t really change during the war, so there will not be a lot to research.” Since students could compare their work during peer engagement, they were not limited if their areas were relatively unaffected. However, they could still reflect on what factors may have led to these differences.

Third, students not only reflected on their successes, but they also shared the challenges they faced, even when they had not been asked to write about them. These spontaneous reflections provided important insights into the inherent difficulties and limitations of the assignment design.

As with many college digital humanities projects, participants expressed some frustrations with technological challenges: “I’m struggling with feeling like I have the map placement off,” and “I think the technology is interesting but sometimes can be frustrating and take an extended period to finish or execute.” While a learning curve is expected when adapting to new technology, instructors need to consider the amount of time required to learn new material versus the time needed to master a new tool. In this case, as discussed below, the researchers believe that the time spent learning the tool resulted in the acquisition of important, transferable skills. At the same time, the feedback provided by students is taken seriously and will be considered in future iterations.

Fourth, a strong thread running through student reflections was the quality of maps as data or as examples of “facts,” demonstrating a level of critical thinking that complicated the notion of “correctness” in interesting ways. One student intelligently stated, “Maps are such a valuable source, but its [sic] important to keep in mind that maps have authors! Those authors can include or exclude whatever they choose. I am really interested to see what the authors of the 1948 map may have left out.” This aligns with Alsaleh’s (2020) emphasis on teaching critical thinking as a core competency in higher education. The ability to question the neutrality of visual data suggests that the assignment fostered analytical habits beyond rote memorization. Another student noted, “My map and our readings tell a different story about my localities. Being able to compare and contrast these sources teaches students a great deal about the importance of considering multiple sources and not taking any source at face value. History requires in-depth research of many perspectives, which is exactly what this project is doing.”

Students, recognizing the limitations of the maps, demonstrated a higher level of critical thinking, creativity, and peer-to-peer sharing of ideas. For instance, one student shared: “Tying into my research, something that I am finding very different to do is finding information on my localities. Some of the major ones are very easy to find information on, yet the smaller ones, specifically the ruins, are harder to find any concrete details about.” According to Zaagsma (2018), this familiar refrain enabled the instructor to explain why these details might be difficult to locate. Similarly, one student said, “I am having a rather difficult time finding information on some of the towns from 1932, some of them don’t exist under the spelling on my map, and some use different spellings after the official inclusion into Israel,” leading to another student adding, “I found this really interesting website that tells the stories and details about depopulated cities in Palestine that might help to see if any of yours are there (and I’ll link it below for you in the Haifa district!!). I would also maybe research and find out more about the roads, as they might be interesting to see if they have any stories that connect to the war.” These moments of difficulty translated into teachable moments about the limitations of historical data, the sociopolitical causes, the ability of technology to illustrate while still having drawbacks, and the opportunity for further research beyond the assignment and into the final project.

The fifth item highlights how mapping software reveals interesting insights. The first iteration of this project involved students physically cutting out maps and rearranging them into a PowerPoint presentation for their showcase. Transitioning to a digital tool, class participants expressed overall satisfaction with using Google Earth to complete the project, pinpointing specific strengths that contributed to their learning: “For this project particularly, the ability to overlay the two map sheets onto a present-day model of the area gave me a unique ability to study them in a way I never would have been able to by simply viewing them one at a time;” and “The use of Google Earth in this project felt much more engaging than a simple paper, having a hands-on approach while memorizing the terrain and surroundings of Eretz Israel has made my understanding of the region much clearer and has allowed for a more in-depth comprehension of the conflict.”

This clearly demonstrates the multimodal learning that occurs when working on digital humanities projects. Data becomes three-dimensional, and the gaps become more pronounced, inspiring both curiosity and frustration in turn. Historical research can, at times, risk reducing the human toll to mere figures. However, a project like this, as explained by one student, brings the research to life: “I think that when people read a description of the various battles and the advancements of a military force, its [sic] hard to visualize the cultural and human impact that such events have. So, using mapping projects like this helps visualize the impact it had geographically, of course, but also see how a given area has developed into cities full of people, as well as how cities and towns have entirely vanished.”

Pre and post-surveys

In the pre-survey, students identified various transferable skills they expected to gain from this course. Examples included research skills like evaluating primary and secondary sources to assess accuracy and bias. In terms of research skills, other students highlighted the importance of critical analysis and critical thinking. Another area, though not clearly articulated by some students, was the significance of communicating with others about complex issues, particularly the specifics of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Additionally, another student mentioned reading and writing skills.

In the pre-survey, students identified examples of assignments from other courses, beyond writing research papers, as part of their overall coursework. Of the 15 students who participated in this survey, six reported primarily having experience with research papers or similar assignments. The others listed a range of examples. One example was writing in the first person about a historical period or recreating a historical event, such as a personal letter. Other students had been assigned tasks that involved creating new content, like recording a podcast, writing a grant proposal, or delivering a speech. A few students had worked on analyzing primary and secondary sources, including graphs, or utilizing a GIS map.

In the post-survey, we asked students to answer 9 questions, including 2 that were repeated from the pre-survey regarding their year in college and their major area of study. The third question asked students to rate, “How difficult was it to use Google Earth Pro to complete the mapping portion of the assignment?” The results in Figure 1 indicate that most students found it easy or very easy (47% and 7%, respectively) to use Google Earth Pro to complete the mapping portion of the assignment. Only 13% thought it was difficult. A supermajority of the students indicated that using the digital tool to create a digital map greatly or moderately enhanced their understanding of the war of 1948 (53% and 27%, respectively). Only 7% thought that it slightly enhanced their understanding.

Furthermore, students agreed that the digital map had a positive impact on their engagement in this course compared to other classes. Forty-seven percent indicated they were much more engaged, while fifty-three percent reported they were more engaged. None reported being less or much less engaged.

When asked how this major assignment relates to the work assigned in their other courses, most students (60%) indicated that only a few of their courses involved assignments beyond traditional research papers and exams.

Finally, to connect our findings on transferable skills, the last question asked students to indicate whether creating a digital map in Google Earth Pro had taught them a transferable skill applicable to other areas, such as other courses or their lives after graduation. Ninety-three percent of the students (all but one student) responded positively, indicating that they believe the skills learned here will assist them in the future.

The post-survey findings indicate that students found utilizing Google Earth Pro to create digital maps both manageable and beneficial. The tool improved their understanding of the subject matter and increased their engagement compared to traditional assignments. Although most of their other courses relied on research papers and exams, students acknowledged the value of a diverse range of assignment types. They appreciated the opportunity to develop transferable skills. This indicates a potential for incorporating more diverse digital tools and creative assignments into the curriculum to foster deeper learning and engagement.

Pre-survey responses indicated that most students expected to develop transferable skills, often described qualitatively (e.g., critical thinking, research). At the same time, post-survey results show that 93% of students reported acquiring transferable skills applicable beyond the course. This suggests alignment with Washer’s (2007) framework for skill development in higher education. Regarding prior experience, only 40% of students had completed assignments other than research papers before taking this course. After the digital mapping assignment in this course, all students reported increased engagement compared to other courses, with 47% saying they were “much more engaged” and 53% saying they were “more engaged.”

The last two questions of the post-survey were open-ended. The first of these asked students about the most important thing they learned from the digital map assignment. Students’ responses can be grouped into five themes: (1) visualizing the impact of war; (2) the importance of geography in a historical context; (3) enhanced research skills; (4) technological proficiency; and (5) emotional and motivational effects.

First, many students emphasized the importance of visualizing historical events, especially the 1948 war, through digital maps. One student said, “I was able to visualize the impact that the war actually had. I was also able to learn that there were changes that occurred before or after the war (not a result of the war of 1948).” Another echoed this sentiment by stating, “I learned visually the effects of the 1948 war.” The visual representations provided by digital maps helped students grasp the profound changes and their human impact more effectively than textual descriptions alone.

Second, understanding the geographical aspects of historical conflicts was another key learning outcome. Students recognized the critical importance of geography in shaping conflicts and historical narratives. One student noted, “Learning how important geography is to the development of conflict.” This recognition highlights the importance of spatial analysis in historical research and how geography can impact historical events and their outcomes.

Third, the assignment improved students’ research skills. Many students reported learning to cross-reference sources and not accept data unexamined. For instance, a student remarked, “I learned not to take data at face value. Looking at the map, I was able to see things that did not match with sources I read, and it made me delve deeper.” Another student emphasized the importance of the research skills gained from the assignment, stating, “The research skills this assignment has taught me are the most valuable takeaway personally […].” These skills are essential for academic growth and for preparing for future research endeavors.

Fourth, the assignment also fostered technological proficiency, primarily through the use of tools such as Google Earth Pro. Several students mentioned learning how to use Google Earth Pro and developing mapping skills. One student shared, “How to use Google Earth and mapping skills,” while another noted, “Cross-referencing other sources for info spanning several decades. Also, how to use Google Pro Earth, though it was just the satellite overview.” This proficiency is valuable for historical research and has various applications in their academic and professional careers.

Fifth, students’ reflections highlighted the assignment’s emotional and motivational impact. Many students found it poignant to witness the war’s effects on people. One student said, “The most important thing I learned was about how much these towns and people were affected due to the war. It was very moving to see and made me want to learn more.” This emotional engagement can cultivate a deeper interest in historical studies and a commitment to understanding and researching complex historical events.

In conclusion, the digital map assignment offered a diverse learning experience for students, deepening their understanding of the 1948 war through visual tools, highlighting the significance of geography, and enhancing their research and technological skills. Furthermore, the emotional impact of visualizing historical events has inspired students to delve into and better understand history’s complexities. The assignment has provided students with valuable skills and insights that will benefit their academic and professional journeys.

The final open-ended question, question 9 in the survey, asked students to list any additional comments or suggestions. Many students expressed that the class and final project provided an exceptional learning experience. One student stated, “I love this class and this final project has been an awesome research opportunity!” Another echoed this sentiment, “None, this was a wonderful assignment that I enjoyed working on.” The overall enthusiasm for the project highlights its effectiveness in engaging students and enhancing their learning.

The students’ comments emphasize the importance of instructor involvement in fostering student success and satisfaction with the project. Additionally, the students were pleased with the project’s timing and structure. One student found it beneficial that the project was scheduled to end before the end of the semester, stating, “The project was very cool! It was helpful that we did it before finals.” This highlights how thoughtful assignment structuring can reduce stress and enhance student performance, which is in line with the active learning benefits described by Kuh (2008).

Finally, despite the generally positive feedback, students also provided constructive suggestions for improvement. One suggestion was to provide additional resources to support the project’s technical aspects. A student recommended, “A video tutorial to reference for Google Earth use would be nice.” This indicates that while students found the project valuable, they identified further opportunities to enhance the learning experience with supplementary instructional materials.

The feedback from students regarding the final project in this class reveals a highly positive learning experience characterized by engaging content, effective timing, and helpful instructor support, which resonate with Zeedan (2024), who emphasizes the role of inclusive and experiential learning environments in fostering student engagement and success in courses about Israel and Palestine. Students appreciated the opportunity for in-depth research and the guidance provided by the instructor. However, they also suggested including additional resources to enhance the project’s effectiveness further. The project successfully facilitated student learning and engagement, with minor improvements recommended to optimize future iterations.

Discussion

This study examined the implementation of a digital mapping assignment in a history course, focusing on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the 1948 war. The findings suggest that this innovative approach can serve as an effective pedagogical tool for enhancing student engagement, understanding, and the development of transferable skills.

The study revealed several key findings. Students reported an increase in their understanding of the war of 1948 through the use of a digital mapping tool. The digital assignment achieved higher student engagement than traditional methods. Students acquired valuable transferable skills, including research proficiency, critical thinking, and technological literacy. Finally, most students expressed positive feedback and satisfaction with the assignment.

The most notable contribution of this study is demonstrating how digital mapping in a history class enhances technological literacy. Our findings align with previous research, such as Bodenhamer et al. (2010) and Knowles and Amy (2008), which emphasize the potential of digital tools to improve students’ proficiency in handling complex software, including Google Earth Pro, and integrating technology into their academic work. We showed that by engaging with this digital tool, students could analyze historical data spatially and visually, which not only fostered technological proficiency but also equipped them with transferable skills applicable beyond the course. Furthermore, this study supports the growing body of literature advocating for innovative pedagogical approaches beyond traditional methods (Kuh, 2008).

One probable reason for the reported increase in engagement is the assignment’s multimodal nature. Unlike traditional research papers, the digital mapping project required students to interact with historical data in visual and spatial ways. This hands-on approach lets learners overlay maps, identify patterns, and explore contested spaces in ways that text alone cannot convey. Such active learning strategies match high-impact practices that encourage curiosity and metacognitive reflection, as evidenced by students’ comments about discovering “hidden stories” and “visualizing the human impact of war.”

As Olesen et al. (2021) note, there are ambiguities in defining transferable skills, which can vary between BA programs (Allan et al., 1995). Our study aligns with this understanding, demonstrating that digital mapping assignments can foster transferable skills, including critical thinking, problem-solving, and technological literacy. Consistent with the research of Knowles and Amy (2008) and Schindler (2016), we found that using digital tools in history classes effectively equips students with these essential skills. Furthermore, the assignment’s problem-solving and collaborative nature, as highlighted by Hauhart and Grahe (2014), provides valuable opportunities for students to develop their research skills.

Moreover, this study demonstrates the impact of digital assignments on fostering critical thinking and research skills. As Choi (2004) noted, high-impact educational practices, such as problem-solving, research, and critical analysis, encourage deeper student engagement with the material. In this study, we showed that students exhibited a high level of engagement with historical maps, analyzing the differences between pre- and post-1948 maps of Palestine/Israel and critically assessing historical data. This supports the argument that digital assignments can potentially transform students from passive recipients of information into active learners capable of conducting independent research and drawing conclusions from multiple sources, even in a history class.

Additionally, this research highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration as students interact with diverse data sources and digital tools. This aligns with the literature on innovative pedagogical approaches, which highlights the value of interdisciplinary methods in enhancing student learning (Henscheid, 2000). By working with historical texts, primary demographic data, and technological tools, students in this class learned to examine complex historical and political issues from diverse perspectives, fostering collaboration and critical analysis.

This study contributes to ongoing discussions in the field of digital humanities, particularly regarding the management of multilingual and contested content. Similar to Zaagsma’s (2018) discussion on Jewish Studies, this project confronted the challenges of representation and accessibility as students engaged with historical data in English, Arabic, and Hebrew, while also addressing the complexities of mapping contested territories. By exploring similar questions about accessibility and representation, this project adds to ongoing conversations about the limitations and possibilities of digital humanities in preserving and presenting complex historical narratives.

The challenges students reported with technology, such as aligning map layers, underscore the importance of scaffolding in digital humanities pedagogy. This observation supports Tracy and Hoiem’s (2017) argument that structured guidance and iterative feedback are essential for the successful integration of digital tools in humanities courses. Addressing these challenges through tutorials and peer support could further enhance engagement and skill acquisition in future iterations.

Integrating collaboration between librarians and faculty is another significant contribution, echoing Murphy’s (2019) findings that such partnerships can enrich the design and execution of research assignments. As demonstrated in the Sprints program (Lach and Rosenblum, 2018; Wiggins et al., 2019), librarians can assist faculty in revamping assignments and supporting students. This study’s collaboration with librarians during sprints week provided a model for successful interdisciplinary partnerships in educational settings. Librarians not only helped the instructor revamp the assignment but also provided direct support to students with the project’s technical aspects. This collaboration ensured that students gained technical skills and developed research methodologies that enhanced their engagement with the course material, aligning with the long-term benefits of Sprints participation identified by McBurney et al. (2024).

The original goals of the faculty member from sprint week were: (1) Digitize the assignment: Instead of students working on individual PowerPoint presentations with cut-and-paste maps, the entire class will collaboratively create interactive maps; (2) Investigate and identify suitable digital tools: Explore potential software options and choose the best tool for the project; (3) Prepare the assignment for the following fall semester: Create the necessary materials and resources for students to complete the assignment; (4) Seek library assistance: Obtain help from the library to find historical maps and conduct research on the topic; (5) Produce two examples: Create two sample research projects on different regions to demonstrate the expected outcomes to students; (6) Enhance student learning, engagement, and transferable skills: Improve the final assignment to foster an engaging learning environment that equips students with transferable skills essential for future academic and professional endeavors. All these goals were achieved, and the assessment results demonstrate the success of the collaborative changes implemented during sprint week.

Examining how these findings apply to other historical contexts and fields could also provide valuable insights. Future studies should investigate the challenges of utilizing digital tools, particularly in educational settings with limited resources. Although this project successfully used Google Earth Pro, which is provided free to users, further research is needed to address barriers to the adoption of digital tools in institutions with limited technical infrastructure. Overcoming these challenges will make digital humanities methods more accessible. It is also important to investigate differences in students’ learning styles and preferences in future research, as well as how these factors affect their engagement with the digital mapping assignment. This could provide a more detailed understanding of how digital tools can be tailored to meet the diverse needs of all learners. Since the study focused solely on a history course, its findings may not be fully applicable to other fields where digital tools may work differently.

This study’s findings reinforce Fyfe’s (2018) argument that digital humanities projects promote metacognitive engagement by requiring students to reflect on both the content and the methods. Students’ recognition that “maps have authors” demonstrates critical thinking about source bias, a skill highlighted by Alsaleh (2020) as essential for academic and professional success. Additionally, the positive response to multimodal learning supports Schindler’s (2016) claim that spatial literacy improves understanding in historical studies.

In conclusion, this study reaffirms the value of integrating digital tools, such as digital mapping, into higher education curricula. These tools enhance student engagement and equip students with essential transferable skills, including technological proficiency, critical thinking, and research capabilities. This project contributes to ongoing discussions about the future of digital humanities in education by fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and engaging with complex and contested content. Future research should continue to investigate the long-term effects of these innovations and expand their application across diverse disciplines and cultural contexts.

These findings fill a gap identified in the theoretical framework. While earlier research highlights the advantages of digital tools for engagement and technological literacy, few studies explore their role in developing transferable skills within history courses on complex topics such as the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Our results indicate that digital mapping assignments can foster critical thinking and research skills by requiring students to triangulate sources and question the authority of maps as historical evidence. This broadens the discussion from mere engagement to skill development that is applicable across academic and professional settings.

The study offers practical insights into design of future courses. Initially, scaffolding was essential for handling the technical learning curve and keeping students motivated. Next, recommending video tutorials underscores the importance of additional resources to reduce frustration and maximize the benefits of digital tools. Lastly, adding collaborative activities—like peer review and shared troubleshooting—can further increase engagement and promote deeper learning. These approaches can inform the development of similar assignments in other humanities courses, helping to balance content mastery with the development of transferable skills.

Despite these strengths, the study also has limitations. One limitation is the relatively small sample size of 17 students in a single class, which may restrict generalizability to other educational contexts. Additionally, while the survey results indicate positive responses, the study relies on self-reported data, which may be prone to bias. Future research is needed to explore the long-term impact of digital mapping assignments on student learning outcomes by tracking students over a more extended period, assessing their learning outcomes and engagement, and investigating the retention of knowledge and skills acquired.

Another limitation relates to the technical requirements of the learning media used. Google Earth Pro requires sufficient computer processing power and stable internet access to display high-resolution maps and overlays. While most students used personal laptops, differences in hardware specifications and internet speeds may have hindered students’ experiences (e.g., difficulty aligning map layers or delays in loading imagery). These factors could affect the perceived ease of use and the time needed to complete the assignment. Future versions should provide access to campus computer labs with high-speed internet and create offline resources or tutorials to address these challenges.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Dumpert, Jennifer Lauren Brewer, The University of Kansas. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1718028/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Allan S. Blount G. Dodd T. Johnstone S. Joyce P. Walcott V. et al (1995). “The use and value of profiling on a BA Business Studies placement,” in Transferable Skills in Higher Education, ed.AlisonA. (London: Kogan Page), 68–81.

2

Alsaleh N. J. (2020). Teaching critical thinking skills: literature review.Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol.1921–39.

3

Assiter A. (2017). Transferable Skills in Higher Education.London: Routledge.

4

Bello L. Dickerson M. Hogarth M. Sanders A. (2017). “Librarians doing DH: a team and project-based approach to digital humanities in the library,” in The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship, edsBodenhamerD. J.JohnC.TrevorM. H. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 2010.

5

Bodenhamer D. J. Corrigan J. Harris T. M. (eds). (2010). The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship. Indiana University Press.

6

Central Bureau of Statistics (2019). Population - Statistical Abstract of Israel 2019- No.70.Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics.

7

Choi H. (2004). The effects of PBL (Problem-Based Learning) on the metacognition, critical thinking, and problem-solving process of nursing students.J. Korean Acad. Nurs.34712–721. 10.4040/jkan.2004.34.5.712

8

Dodsworth E. Nicholson A. (2012). Academic uses of Google earth and google maps in a library setting.Informat. Technol. Lib.31102–117. 10.6017/ital.v31i2.1848

9

Draxler B. Hsieh H. Dudley N. Winet J. (2012). Undergraduate peer learning and public digital humanities research.E-learning Digit. Media9284–297. 10.2304/elea.2012.9.3.284

10

Duong P. T. (2024). Solutions to improving Google Earth, Earth Pro, and Maps application in teaching Physical Geography to Geography Pedagogy students, Dong Thap University. Dong Thap University.Dong Thap Univ. J. Sci.1355–67. 10.52714/dthu.13.3.2024.1248

11

Eccles J. S. Bonnie L. B. Margaret S. James H. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development.J. Soc. Issues59865–889. 10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x

12

Elmuti D. William M. Michael A. (2005). Does education have a role in developing leadership skills?”.Manage. Decis.431018–1031. 10.1108/00251740510610017

13

Fyfe P. (2018). Reading, making, and metacognition: teaching digital humanities for transfer.Digit. Human. Q.121–12.

14

Hauhart R. C. Grahe J. E. (2014). Designing and Teaching Undergraduate Capstone Courses.Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

15

Henscheid J. M. (2000). Professing the Disciplines: An Analysis of Senior Seminars and Capstone Courses.Columbia: University of South Carolina.

16

Khalidi W. (1992). All that remains: The Palestinian villages occupied and depopulated by Israel in 1948.Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies.

17

Khandkar S. H. (2009). Open Coding.Calgary, AB: University of Calgary.

18

Knowles A. K. Amy H. (2008). Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS are Changing Historical Scholarship.Redlands, CA: ESRI, Inc.

19

Kokin D. S. (2022). “Introducing ‘Kol ha-Nekudot’/’All the Points’/’Kull al-Nuqaţ’: Interactive, Online Mapping of the Israeli-Palestinian Region (1840–Present)”.Stud. Digit. Hist. Hermeneut.169–186.

20

Kuh G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices.Peer Rev.1030–31.

21

Lach P. R. Rosenblum B. (2018). “Sprinting toward faculty engagement: adopting project management approaches to build library–faculty relationships,” in Project Management in the Library Workplace, edsDaughertyA. L.HinesS. (Bradford: Emerald Publishing Limited), 89–114. 10.1108/S0732-067120180000038002

22

Manke J. (2022). “Digital mapping technology and the war of the sicilian vespers: using new methods to better understand old problems,” in Mapping Pre-Modern Sicily: Maritime Violence, Cultural Exchange, and Imagination in the Mediterranean, edsTaiE. S.ReyersonK. L. (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 245–268. 10.1007/978-3-031-04915-6_14

23

McBurney J. Brown S. J. Gyendina M. Hunt S. Orozco R. Peper M. et al (2024). A Supernova that Sparks in Every Direction”: A Long-Term Assessment of the Research Sprints Faculty Engagement Program.Chicago, IL: American Library Association

24

McClurg C. Powelson S. Lang E. Aghajafari F. Edworthy S. (2015). Evaluating effectiveness of small group information literacy instruction for Undergraduate Medical Education students using a pre- and post-survey study design.Health Inform. Lib. J.32120–130. 10.1111/hir.12098

25

McGinn E. Duever M. (2018). Building maps: GIS and student engagement.Lib. Hi Tech News359–12. 10.1108/LHTN-12-2017-0089

26

Mostern R. Gainor E. (2013). Traveling the silk road on a virtual globe: pedagogy, technology and evaluation for spatial history.Digit. Human. Q.7:2.

27

Murgu C. Dancigers M. Solloway E. (2021). Design sprints and direct experimentation: digital humanities+ music pedagogy at a small liberal arts college.Notes77561–585. 10.1353/not.2021.0043

28

Murphy M. (2019). On the same page: collaborative research assignment design with graduate teaching assistants.Refer. Serv. Rev.47343–358. 10.1108/RSR-04-2019-0027

29

Olesen K. B. Christensen M. K. Dyhrberg O’Neill L. (2021). What do we mean by ’transferable skills”? A literature review of how the concept is conceptualized in undergraduate health sciences education.High. Educ. Skills Work-Based Learn.11616–634. 10.1108/HESWBL-01-2020-0012

30

Özyeşilpınar E. Beltran D. Q. (2022). Digital story-mapping.Methods Methodol. Res. Digit. Writ. Rhetoric1111–133. 10.2196/60810

31

Schindler R. K. (2016). Teaching spatial literacy in the classical studies curriculum.Digit. Human. Q.101–10.

32

Suharini E. Ariyadi M. H. Kurniawan E. (2020). Google Earth Pro as a learning media for mitigation and adaptation of landslide disasters.Int. J. Inform. Educ. Technol.10820–825. 10.18178/ijiet.2020.10.11.1464

33

Taylor D. (1995). “Profiling the year abroad in modern language degrees,” in Transferable Skills in Higher Education, ed.AlisonA. (London: Kogan Page).

34

The Government of Mandatory Palestine (1945). Village Statistics, British Mandatory Palestine.Jerusalem: The Government of Mandatory Palestine.

35

Tracy D. G. Hoiem E. M. (2017). Scaffolding and play approaches to digital humanities pedagogy: assessment and iteration in topically-driven courses.Digit. Human. Q.11.

36

Warren M. J. C. (2016). Teaching with technology: using digital humanities to engage student learning.Teach. Theol. Relig.19309–319. 10.1111/teth.12343

37

Washer P. (2007). Revisiting key skills: a practical framework for higher education.Qual. High. Educ.1357–67. 10.1080/13538320701272755

38

Wiggins B. Hunt S. L. McBurney J. Younger K. Peper M. Brown S. et al (2019). Research sprints: a new model of support.J. Acad. Librariansh.45420–422. 10.1016/j.acalib.2019.01.008

39

Wishkoski R. Lundstrom K. Davis E. (2019). Faculty teaching and librarian-facilitated assignment design.Portal1995–126. 10.1353/pla.2019.0006

40

Zaagsma G. (2018). # DHJewish–Jewish Studies in the digital age.Medaon – Magazin für jüdisches Leben Forschung und Bildung121–11.

41

Zeedan R. (2024). College student engagement and success through inclusive learning environment and experiential learning in courses about Israel and Palestine.Front. Educ.9:1497045. 10.3389/feduc.2024.1497045

Summary

Keywords

1948 war, digital humanities, digital mapping, history courses, Israel Studies, Palestine Studies, student engagement, Google Earth

Citation

Zeedan R, Bishop Simmons S and Peper M (2026) Evaluating the impact of a digital mapping assignment on student learning, engagement, and transferable skills. Front. Educ. 10:1718028. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1718028

Received

03 October 2025

Revised

12 November 2025

Accepted

22 December 2025

Published

23 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Aiedah Khalek, Monash University Malaysia, Malaysia

Reviewed by

Enrique H. Riquelme, Temuco Catholic University, Chile

Zainur Rasyid Ridlo, University of Jember, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Zeedan, Bishop Simmons and Peper.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rami Zeedan, rzeedan@ku.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.