Abstract

Introduction:

Traditional teaching methods have been central to education systems worldwide. Still, digital innovation in higher education has transformed how education is delivered, introducing new teaching models and enhancing school management processes. However, most Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) face numerous limitations in effectively adopting digital systems, although these challenges are often context-specific.

Methods:

To gain a deeper understanding of the scope and limitations of digitalization in higher education institutions, we conducted a comparative analysis of existing digital ecosystems across developed and developing countries.

Results:

We introduced a three-layer framework for digitalization comprising institutional strategies, technological tools, and pedagogical methods. These layers are further divided into several components that support innovation. Using data from multiple sources, we identified several current drivers of the adoption of digital innovation in universities, including student expectations and needs, technological advances, strategic leadership, and the rise of hybrid learning models. Additionally, we compared the rate of digitalization in HEIs between developed and developing countries; our findings indicated that innovation proceeds more smoothly and is easier to manage in developed nations. We highlighted strategies for scalable and sustainable innovation through successful case studies from well-known universities. To tackle systemic challenges in digitalization, their impacts, potential solutions, and levels of implementation, we employed a priority matrix approach. This approach showed that most challenges are quick wins when addressed and have a substantial impact on digitalization.

Discussion:

This study emphasizes the importance of adaptive, inclusive, and strategic approaches that promote equity and encourage the adoption of global learning ecosystems by comparing digital innovation in developed and developing countries.

1 Introduction

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, several universities worldwide have adopted the E-Systems and other distance learning platforms. This innovation has shaped Higher Education Institutes (HEIs), upgrading both teaching methods and school administration (Deroncele-Acosta et al., 2023), and offers flexible and accessible learning options, allowing students to work independently (Santiago et al., 2021). Today, these innovations are supported by modern technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) (Okunlaya et al., 2022), learning analytics (Mah, 2016), cloud computing (Kryukov and Gorin, 2017), and immersive environments such as virtual and augmented reality (Kryukov and Gorin, 2017). Digitalization in HEIs plays a crucial role in organizing educational content, facilitating communication between teachers and students, managing the learner experience, and tracking progress and assessment (Bradley, 2021). Examples of learning management systems currently used include Canvas, Blackboard, and Moodle, while Zoom and Microsoft Teams are used as virtual classrooms. Other AI-powered tutoring systems and virtual reality have also enabled personal experience of Open educational resources (OERs), and massive open online courses (MOOCs) (Mishra, 2017; Rulinawaty et al., 2023).

Digitalization in HEIs has often been framed in theoretical frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), which emphasizes two main key factors: perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), shaping users' attitude, intentions, and ultimately their actual technological use (Natasia et al., 2022). The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) explains that teachers effectively integrate technology into teaching by balancing content knowledge (CK), pedagogical knowledge (PK), and technological knowledge (TK) (Schmidt et al., 2009). Also, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) that identifies reasons of digitalization in four key constructs: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions (Chakraborty and Al Rashdi, 2018). While these theories address essential dimensions of digitalization, they only address issues dealing with individual or classroom-level interactions. The greatest requirements of digital innovation in HEIs are frameworks that extend to involving institutional change, organizational culture, and systemic resilience. For instance, concepts focusing on ensuring fair access to infrastructure and professionalism to sustain innovation in both developing and developed countries (Gull et al., 2024). Positioning digitalization in HEIs within these concepts bridges the gap between established adoption models and transformation-oriented frameworks. Also, it provides a deeper understanding of how HEIs in both contexts navigate through challenges of equity and institutional changes.

Although the adoption of digital platforms may vary between developed and developing countries, specifically, in developed countries, these technological advancements are more adaptable, enabling informed decision-making through data analysis and educational experiences (Skenderi and Skenderi, 2023). While in developing countries, HEIs often lack consistent access to technology due to socio-economic limitations, limited infrastructure, digital illiteracy, and insufficient funding (Alenezi, 2023). Additionally, developing countries face persisting constraints, including poverty, gender inequality, and language barriers hinder the full participation of developing nations in the digital economy (Imran, 2023). Suggesting that digital innovation in higher education in developed countries is more organized and achievable compared to that of developing countries (Imran, 2023). Although a lot has been shown relating to these studies, for instance, Bond et al. have shown a comparative study in digital innovation, and revealed that in developed and developing countries, different drivers motivate digital adoption in students; where in developed countries these are mainly to enhance personal learning experience, while in developing countries they are more linked to fundamental goals of increasing access (Bond et al., 2019). Traxler (2018) have also shown that developed and developing countries often adopt technologies based on contextual constraints and priorities, where developed countries adopt high technology for exploring learning management systems like Canvas or Moodle. While developing countries prioritize more accessible technologies, such as mobile learning (m-learning), they use basic applications like WhatsApp and Telegram.

A comprehensive understanding of digital technologies remains inadequate; thus, approaches to digital adoption between developed and developing countries, the impact of digital innovation on teaching quality and student learning outcomes, and key drivers of digital innovation between developed and developing countries still require clarification. This highlights the urgent need to bridge global perspectives and promote the adoption of technology in various educational contexts. This study seeks to compare the different approaches to digital innovation in HEIs in developed and developing countries. Answering key questions regarding key drivers of digital innovation, their differences, and solution implementations. Additionally, it addresses the challenges and solutions to digital innovation implementation by analyzing crucial case studies of successful digital projects, particularly those in developing regions. To conduct this comprehensive research, we adopted the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) criteria in a systematic literature review (SLR) (Schiavenato and Chu, 2021) with added features, defined below:

Population: Universities (Globally-universities only) in developed and developing countries

Intervention: Adoption of digital innovation strategies and technologies

Comparisons: Drivers, implementation, and outcomes across developed and developing countries.

Outcomes: Identification and analysis of key drivers influencing digital innovation adoption.

Timing: Literature reviews published between 2000 and 2025

Setting: Institutions, including and limited to public and private universities

Language: Publications in English for consistency and accessibility in analysis.

2 Materials and methodology

2.1 Data extraction and categorization

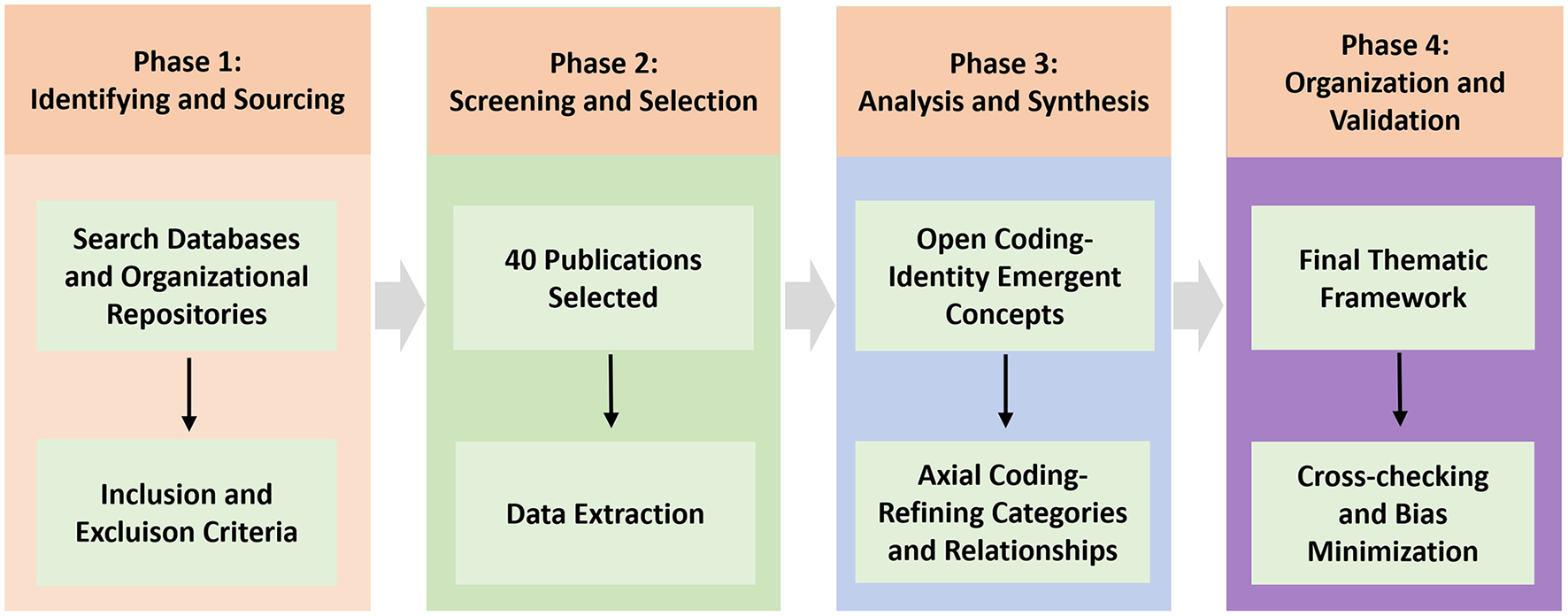

To have a clearer comparison of digital innovation adoption in developed and developing countries, this study adopted a systematic approach to data extraction and synthesis. A total of forty publications were considered, sourced from peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2025, policy reports, and datasets from International organizations, including UNESCO and the World Bank (Figure 1 and Supplementary File 1). Specifically, forty sources were selected to reflect the breadth and comparative scope of the topic, capturing diverse perspectives across developed and developing countries (Supplementary File 1). These sources were identified through targeted searches using key terms such as digital innovation, AI integration, HEIs, e-learning, and digital transformation. For the inclusion criteria, studies including a direct address of digital innovation with HEIs (universities only) were considered, focusing on developed, developing countries, or both contexts, and were published in English. Regarding the data sources, the eligible sources considered were those providing empirical or policy-relevant insights. Excluded studies were those lacking the higher education context, without empirical or policy relevance, and without digital innovation as a central theme.

Figure 1

A flow chart of the systematic data acquisition methodology. The process initiates with the identification and sourcing of literature from databases and organizational reports, followed by a screening phase against strict inclusion/exclusion criteria to select the final 40 applications. The analysis phase involves qualitative open and axial coding, ending in a final thematic framework of four categories, with cross-checking to ensure clarity.

Following data extraction, the data were subjected to qualitative analysis, and coding was done systematically. Open coding was first used to capture emergent concepts, followed by axial coding, which was employed to refine categories and establish relationships across contexts. This process ensured analysis beyond categorization and toward precise patterns and contrasts. Finally, the data were categorized into four: institutional strategy and management, technological tools and platforms, pedagogical methods, and barriers to innovation (Figure 1 and Supplementary File 1). Noteworthy, data extraction and thematic coding were done primarily by the lead researcher, with decisions cross-checked by a second reviewer to minimize bias and ensure consistency.

2.2 Case study selection

To select the global universities with standard digital innovation features, we used the registered datasets, including the Web of Science Clarivate database (https://ir.clarivate.com/news-events/press-releases/news-details/2025/Clarivate-identifies-top-50-universities-powering-global-innovation/default.aspx) and Derwent World Patents. The Methodology of consideration was based on the relationship between academic research and patented industrial technologies. In this research, universities were considered exclusively, excluding academic and research institutes. While this choice may emphasize more positive outcomes, potential bias was mitigated through comparative inclusion of diverse contexts and systematic coding of both successes and challenges. In addition, to have a workable framework, the focus of selection was narrowed to patents and research in digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, blockchain, and Internet of Things (IoT). The identified institutes were then ranked based on the number of citations they received in the Web of Science, with the top 20 selected.

2.3 Comparative adoption model analysis

To analyse the drivers of digital innovation across developed and developing countries, an analytical approach was considered, integrating bibliometric, thematic content analysis, and case study comparisons. Data obtained in Section 2.1 (Supplementary File 1) were considered for analysis. Additionally, 10 developed and developing countries were considered for comparisons, sourced from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP; https://hdr.undp.org) and the World Bank—Country Development Updates (2025) (https://data.worldbank.org) and the Brookings Institution—Global Development Program (https://www.brookings.edu). These are listed in Supplementary Table S1. For case studies, at most six universities were considered, with three universities in each group (developed or developing country). For validation and reliability of these studies, cross verification was performed using multiple data sources. To present this analysis, a technology adoption curve (TAC) was utilized, presenting a dual-pathway model between developed and developing countries.

2.4 Data analysis and priority matrix construction

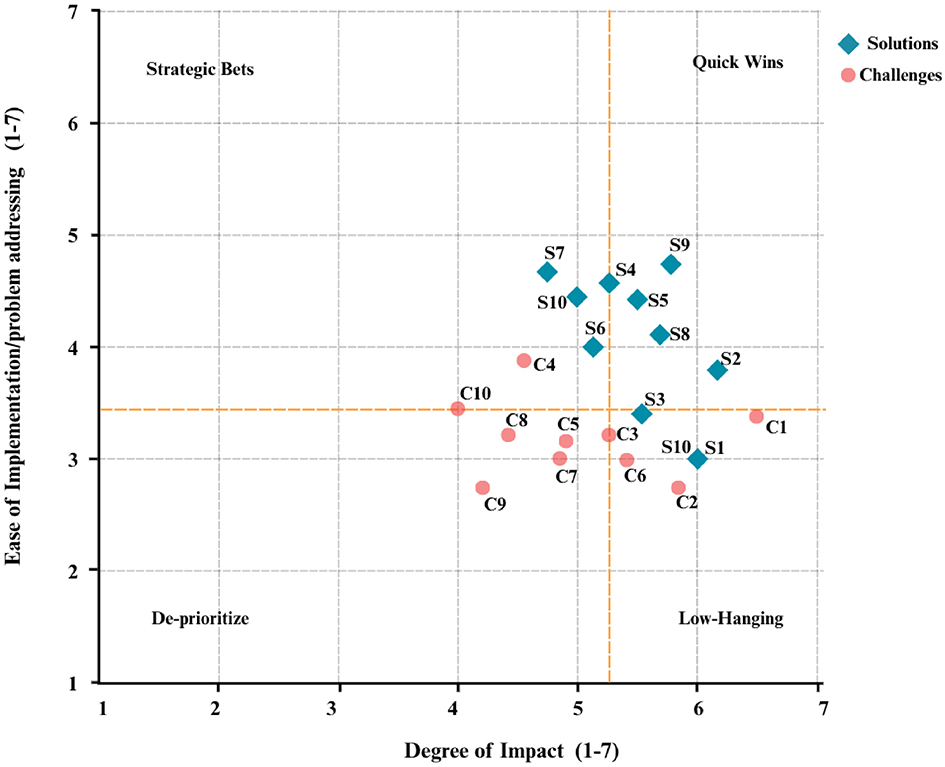

A priority matrix was used to analyze the main challenges to digital innovation and evaluate the feasibility of the proposed solutions. Data were collected as described in Section 2.1 to understand digital innovation in both developed and developing countries. The matrix mapped the degree of impact against ease of implementation, providing support for evidence-based decision-making in strategy and operations. The initial list of 10 challenges and solutions was compiled from the data collected (refer to data above; Supplementary File 1). This draft list was thoroughly refined until consensus was reached on terminology and item inclusion. For the rating process, each challenge and solution was rated on a scale of 1 to 7 (1 being the lowest, seven the highest). The data were processed and standardized, and median scores were calculated for each challenge and solution. Interquartile ranges (IQRs) were computed for descriptive purposes (Supplementary Table S2). All points of intersection (POI) were classified into four quadrants: (1) quick wins (high impact and high ease); (2) strategic bets (high impact, low ease); (3) low-hanging fruit (low impact, high ease); and (4) deprioritize (low impact and low ease). The figure was generated using Python 3.10 and Matplotlib 3.8.

3 Results

3.1 Model for strategic digital innovation

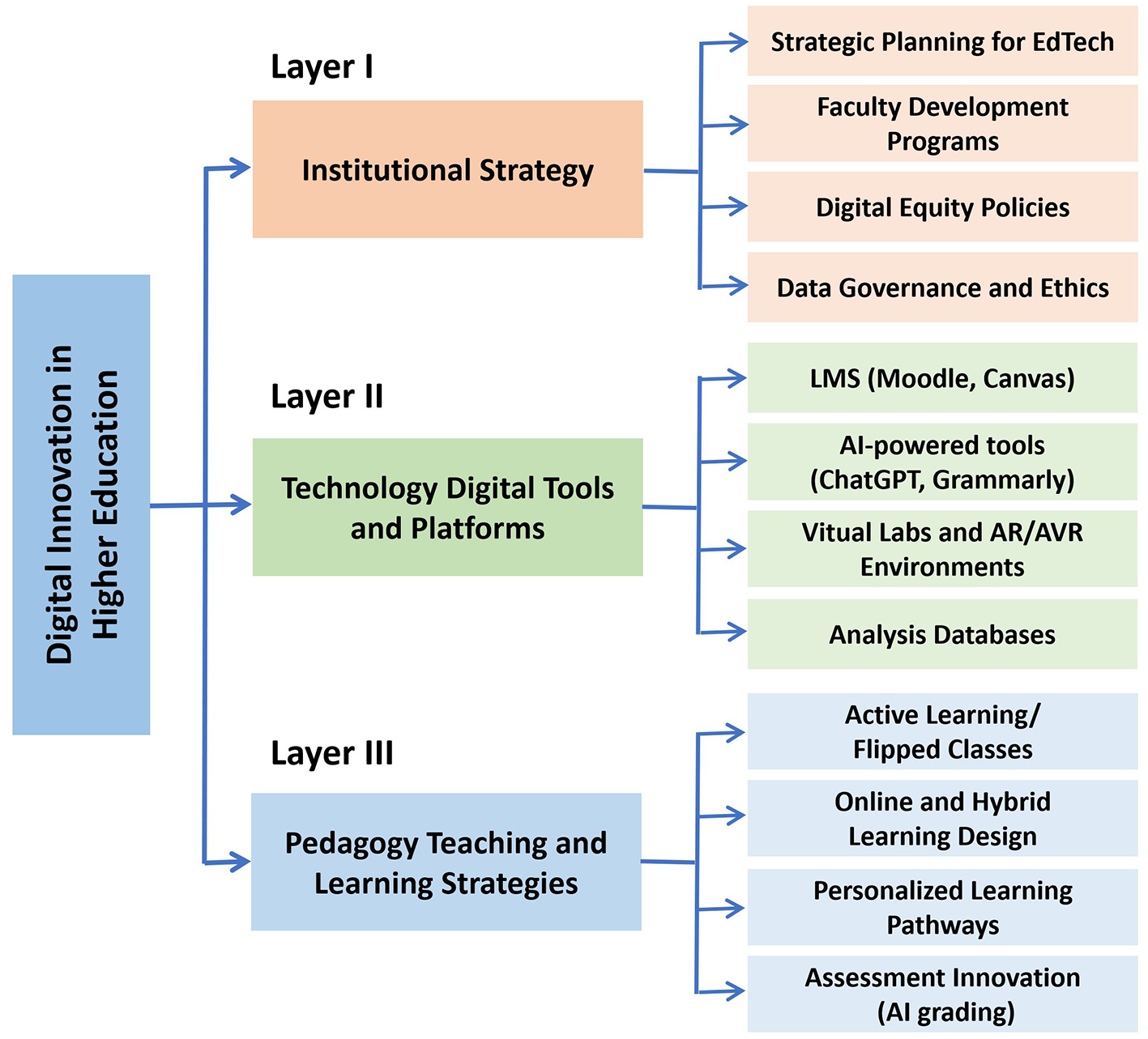

We observed that strategies for digital innovation in HEIs are broadly consistent across developed and developing countries, resembling a multi-layered structure (Figure 2). Although there are discrepancies in the extent of implementation and capacities in sustaining these strategies. In this study, we showed a framework comprised of three independent layers: institutional strategy, technology, and pedagogy (Figure 2). In the Institutional strategy, leadership is central, setting goals, defining operational principles, and allocating resources for digital adoption. Consequently, it provides a foundation on which other layers are laid. The second layer, technology, encompasses digital tools and platforms that provide new modes of delivery and administration. In the Pedagogy layer, teaching and learning approaches integrate digital systems into curricula and assessment. We also noted that these layers were not isolated but extended into broader educational fields, such as faculty development programs, digital equity policies, and data governance and ethics (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Digital innovation framework in higher education. A tripartite layered framework outfling the components of digital innovation in higher education institutions: Layer I, illustrating institutional strategies, this serves as the foundational driver for initiatives, emphasizes on leadership, policy and strategic vision. Layer II encompasses technology (digital tools and platforms), which are platforms, environments, and analysis databases for learning analytics. Lastly, Layer III, pedagogy, highlights all teaching methods that are enabled by technology. These layers interlink, generating a relationship that signifies that effective digitalization in HEIs requires an interactive cycle of all components.

To provide a clearer view of these findings, we summarized this model for strategic digital innovation in Table 1. In which the impact of digital innovation was demonstrated across seven groups, aligning with three main pillars (Table 1). We observed the most significant developments in teaching and learning, where online platforms, adaptive learning systems, and immersive technologies such as VR/AR shape student engagement. Additionally, Assessment and Feedback were shown to be driven by automated tools and data analytics. Meanwhile, institutional efficiency and security were achieved through cloud automation and blockchain-based systems (Table 1). These findings suggest that the process of digital adoption and implementation is structurally logical and universal. It is not uniform but rather a layered framework whose outcomes are mediated by local capacities and priorities.

Table 1

| Category | Digital innovation | Description/examples | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching and learning | Online learning platforms | MOOCs (Coursera, edX), LMS (Canvas, Moodle), hybrid learning models | Greater accessibility, flexible learning, global reach |

| Adaptive learning technologies | AI-driven platforms that personalize learning (Smart Sparrow, Knewton) | Improved student engagement and outcomes | |

| Virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) | Simulated labs, immersive learning in history, medicine, engineering | Greater accessibility, flexible learning, global reach | |

| Gamification | Incorporating game elements in learning (badges, leaderboards). | Increases motivation and engagement | |

| Assessment and feedback | Digital assessment tools | Auto-grading, online quizzes, plagiarism detection (Turnitin, Gradescope) | Efficiency, scalability, instant feedback |

| Learning analytics | Tracking student performance data to improve teaching and support decisions | Enables data-driven teaching and early intervention | |

| Student support | Chatbots and AI assistants | 24/7 student support bots (IBM Watson Education, Replika for mental health) | Immediate help, personalized support |

| Virtual advising | Online academic counseling tools (DegreeWorks, uAchieve) | Better student guidance, increased retention | |

| Institutional operations | Cloud computing and automation | Digitized admissions, registration, financial aid systems | Improved efficiency and reduced administrative burden |

| Blockchain for credentials | Secure, verifiable digital diplomas and transcripts | Reduces fraud, speeds up verification | |

| Research and collaboration | Digital research tools | Online databases, collaborative platforms (Zotero, Overleaf, ResearchGate) | Facilitates interdisciplinary and remote collaboration |

| AI in research | AI for data analysis, simulation, predictive modeling | Accelerates discovery, handles large datasets | |

| Equity and inclusion | Assistive technologies | Screen readers, captioning, adaptive interfaces | Expands access to learners with disabilities |

| Open educational resources (OER) | Free textbooks and content (OpenStax, MERLOT) | Reduces cost barriers, democratizes knowledge | |

| Campus experience | Smart campuses | IoT-enabled campuses for security, lighting, HVAC, and resource management | Sustainability, cost savings, enhanced safety |

| Virtual campus tours | 3D or VR-based exploration tools | Assists with remote recruitment and planning |

Digital innovation framework in higher education institutions and their outcomes.

3.2 Digitalization in developed and developing contexts

Developed and developing countries aim to promote equality and improve educational quality; they often pursue different approaches to achieve these goals, although they face almost similar challenges (Hanna, 1998). These gaps are primarily influenced by infrastructure and core challenges (Matsieli and Mutula, 2024). To answer the research question regarding the strategic priorities of digitalization in HEIs in both developed and developing countries, we conducted a comparative analysis that revealed significant contradictions in approaches to digital innovation adoption (Table 2). In this study, we observed that in developed countries, digitalization is largely framed as a means to overcome foundational challenges while simultaneously expanding access. We noted that their strategic priority is often driven by institutional goals of excellence and competitiveness. Therefore, HEIs in these contexts often invest heavily in immersive digital tools such as augmented AI, AR/VR, and learning analytics. Suggesting that digitalization in developed countries is closely tied to reputational advantage and educational experiences. On the contrary, we also observed that digitalization in developing countries is practical and necessary, driven by the aim to provide basic, scalable access to education, particularly in marginalized communities (Table 2). We noted that HEIs, in this context, prioritize affordable digital tools, mobile-friendly solutions, and open educational resources. Showing that digitalization in developing countries is more about ensuring basic education without the need for competitiveness. Taken together, this result highlights that digitalization in HEIs is not a uniform but context-dependent strategy.

Table 2

| Digital approaches | Developed countries | Developing countries |

|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure and connectivity | Advanced digital infrastructure (high-speed internet, campus-wide Wi-Fi, cloud computing, smart classrooms). | Often limited by poor internet connectivity and outdated infrastructure. |

| Greater access to latest hardware (e.g., VR labs, AI labs, IoT devices). | Reliance on basic tools (e.g., computer labs rather than personal laptops or cloud access). | |

| Funding and resources | Substantial funding from government, industry, and alumni supports research and digital innovation. | Budget constraints limit investments in advanced digital tools and platforms. |

| Strong investment in R&D, digital tools, and continuous tech upgrades. | Heavy dependence on foreign aid, grants, or NGO support for tech-based initiatives. | |

| Digital curriculum and pedagogy | Integration of emerging technologies (AI, blockchain, data science) into the curriculum. | Slower adoption of tech-enabled pedagogies due to lack of training and resources. |

| Use of flipped classrooms, gamification, and personalized learning platforms. | Digital content may not be localized or aligned with local contexts. | |

| Research and innovation ecosystem | Strong collaboration with tech companies, startups, and research institutions. | Fragmented or emerging innovation ecosystems. |

| Incubators and innovation hubs often linked with universities. | Limited tech-transfer mechanisms and industry-academia partnerships. | |

| Digital inclusion and access | Higher digital literacy and access among students and staff. | Digital divide remains a significant barrier—rural vs. urban, gender gaps, affordability. |

| Better support for students with disabilities via assistive technologies. | Limited access to digital devices among students from low-income families. | |

| Policy and governance | Comprehensive digital transformation strategies at national and institutional levels. | Digital policy development is often reactive or inconsistent. |

| Data privacy, cybersecurity, and digital ethics frameworks are well-established. | Regulatory frameworks for digital education may be underdeveloped or poorly enforced. | |

| Adoption of emerging technologies | Proactive experimentation with AI tutors, learning analytics, metaverse classrooms. | More focused on mobile learning, radio/TV education, and basic LMS (e.g., Moodle) due to constraints. |

| Response to crisis (e.g., COVID-19) | Swift transition to online learning using robust platforms like Zoom, Blackboard, Canvas. | Struggled with transition due to infrastructure and access issues; many relied on WhatsApp, radio, and SMS-based solutions. |

Comparative approaches to digital innovation adoption in higher education across developed and developing countries.

3.3 Driving factors of digital innovation adoption

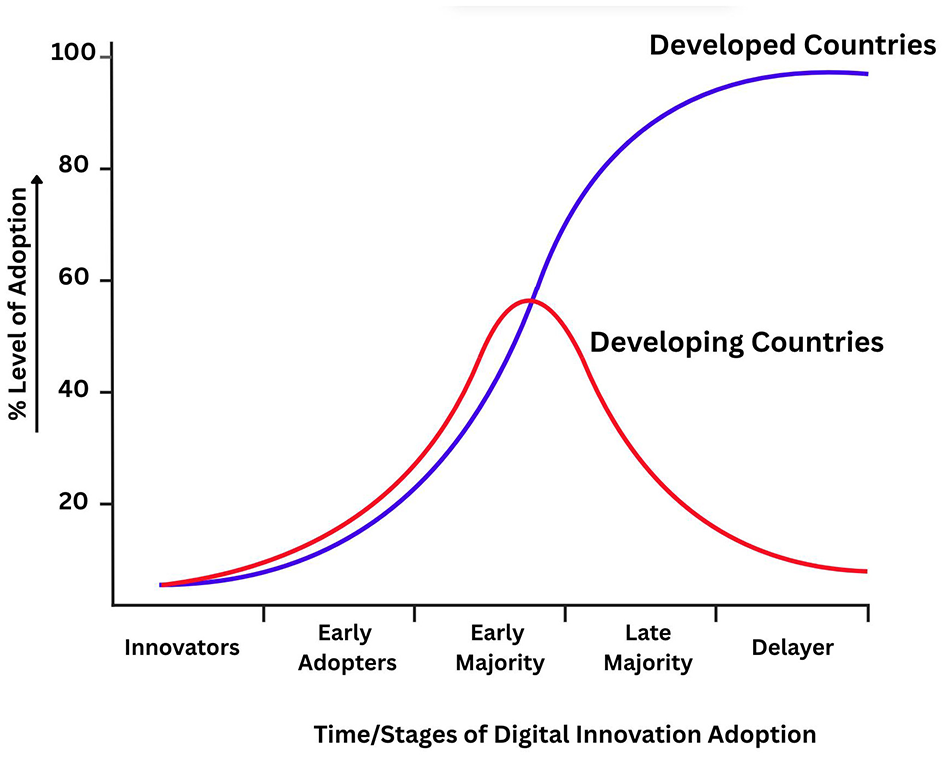

The rate and trajectories of digital adoption in HEIs are contextual and vary (Singun, 2025). Our analysis demonstrated that digitalization in HEIs of developed countries follows a rapid S-curved trajectory (Figure 3). Defined by a rapid uptake beginning at the Early adopter stage and reaching an equilibrium at a high level through the late majority. Suggesting a well-founded infrastructural readiness, policy alignment, and institutional adaptability. In contrast, developing countries demonstrated a delayed and reduced adoption pattern, defined by a diffusion curve (Figure 3). Similar to adoption in developed countries, integration accelerated modestly during the early majority but declined thereafter. This decline is usually due to structural bottlenecks such as limited digital infrastructure, fragmented policy implementation, and socio-economic constraints that impede scalability and long-term institutionalization. Interestingly, the inflection points in both adoption approaches of HEIs in both contexts appear around the early majority stage (Figure 3), highlighting that this phase is critical for widespread adoption. The differences in the post-inflection stage suggest that sustained integration is contingent on endogenous capacity and contextual enablers (Figure 3), while the initial adoption may be fastened by global trends or donor-driven initiatives. These findings imply the need for differentiated innovation strategies: while developed countries may benefit from optimization and refinement of digital ecosystems, developing countries may require targeted interventions that abridge limitations to ensure that early adoption can be translated into durable transformation.

Figure 3

Technology adoption curve with contextual modifiers in higher education. The graph shows two distinct trajectories, comparing digital adoption in Higher Education Institutions across developed and developing countries, marked on the curve. The y-axis perceives external and internal factors limiting the rate adoption, such as institutional policy, digital infrastructure, organizational culture, faculty readiness, and leadership. The x-axis depicts different stages of adoption, ranging from innovators to laggards.

3.4 Cross-case study analysis

Using the Web of Science Clarivate database and Derwent World Patents Index, we showed that digital innovation in higher education is more organized in developed countries, likely due to substantial investments in infrastructure, research, and teacher training (Table 3). From the collected case studies, we observed that institutions in countries such as the United States, Germany, and South Korea are characterized by strong broadband access, sophisticated learning management systems, and policies that emphasize technology-enhanced learning that prioritize technology-enhanced learning (Table 3). Within these contexts, advanced tools such as AI-powered adaptive learning platforms, virtual reality (VR) simulations used in engineering and health education, and data-driven student assistance systems are widely adopted, reflecting a mature ecosystem of digital transformation. On the other hand, systemic issues such as poverty, gender inequality, and language barriers hinder the full participation of developing nations in the digital economy. Cases from regions such as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have smartphone adoption that surpasses the internet penetration, making mobile-first platforms and offline learning applications crucial for extending educational opportunities. These innovations are often pragmatic responses to infrastructure gaps, designed to maximize reach in regions of poor connectivity and scarce resources. Additional comparisons are shown in Table 2. These findings highlight that, unlike developed countries, developing countries adopt digital systems as a tool for widening access and addressing systemic inequalities.

Table 3

| Number | University | Country/ region | Digital innovation features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) | USA | Open Courseware at global scale; CSAIL leading AI/robotics; Initiative on the Digital Economy translating research to practice |

| 2 | Stanford University | USA | Stanford HAI (human-centered AI); Stanford Online for scaled digital learning. |

| 3 | University of Oxford | UK | Oxford Internet Institute (digital society & AI ethics); Bodleian Centre for Digital Scholarship. |

| 4 | University of Cambridge | UK | Cambridge Digital Humanities; flagship AI@Cam & CCAIM for AI in medicine. |

| 5 | ETH Zürich | Switzerland | ETH AI Center (cross-disciplinary AI research & translation). |

| 6 | Technical University of Munich (TUM) | Germany | UnternehmerTUM (Europe's largest entrepreneurship/ innovation center); TUM AI initiatives. |

| 7 | National University of Singapore (NUS) | Singapore | New NUS Artificial Intelligence Institute; NUS FinTech Lab & AI/innovation programmes. |

| 8 | University of Tokyo | Japan | Beyond AI Institute with partners; university-wide digital/AI initiatives. |

| 9 | University of Toronto | Canada | Longstanding AI leadership through CS/AI research; ecosystem ties with Vector Institute. |

| 10 | University of Melbourne | Australia | “Melbourne Connect” innovation precinct (smart, digital, maker/creator spaces). |

| 11 | Tsinghua University | China | Tsinghua AI Institute; XuetangX MOOC platform (pioneer in China's online higher ed). |

| 12 | Peking University | China | PKU Center for AI; digital research/education in AI & data science. |

| 13 | IIT Bombay | India | e-Yantra (nationwide embedded-systems/robotics edtech); major NPTEL MOOC contributor. |

| 14 | IIT Madras | India | Scaled online BS in Data Science/AI; industry-facing deep-tech via Pravartak. |

| 15 | University of Cape Town (UCT) | South Africa | eResearch services supporting data-intensive/digital scholarship; strong OER/digital pedagogy activity. |

| 16 | University of São Paulo (USP) | Brazil | C4AI (USP–IBM–FAPESP Center for AI); Inova USP innovation hub. |

| 17 | Tecnológico de Monterrey | Mexico | Institute for the Future of Education (IFE) and EdTech innovation/observatory. |

| 18 | University of Malaya (UM) | Malaysia | Commercialization/ innovation via UMCIC; campus-wide e-learning/digital initiatives. |

| 19 | KAUST | Saudi Arabia | KAUST AI Initiative and digital-science research; smart campus/advanced digital infrastructure. |

| 20 | University of Nairobi | Kenya | C4DLab (computing for development, startups & digital innovation); FabLab Kenya. |

Global top 20 universities with standard digital innovation adoption and their features.

3.5 Challenges and possible solutions to digital innovation in institutions

Despite significant advancements in digital educational innovation, several challenges persist that hinder its widespread adoption and distribution. These challenges span from institutional, technological, and sociocultural barriers (Mexhuani, 2025). To better understand the barriers and possible solutions, we developed a priority matrix from the collected data (Figure 4). The matrix showed possible challenges against the perceived solutions. While also assessing their impact and feasibility. This approach allowed us to map items in four different strategic quadrants, thereby clarifying initiatives that require prioritization by HEIs. The initial list of ten preliminary challenges and solutions with their feasibility and impact scores is shown in Supplementary Table S2. We noted that solutions clustered in the upper quadrants of the matrix, specifically strategic bets and quick wins (Figure 4). The strategic bets characterized initiatives with high potential impact but a significant implementation difficulty, requiring substantial resources and long-term commitments; these included S4, S6, S7, and S10. In contrast, quick wins are impactful and relatively easy to implement, making them attractive for immediate adoption. This quadrant had five solutions, including S2, S3, S5, S9, and S10.

Figure 4

Priority matrix showing the median ratings (1–7 scale) of challenges (red circles) and solutions (blue diamonds) for digital innovation in universities, based on literature review (N = 40). The horizontal axis represents the degree of impact; the vertical axis represents ease of addressing or implementing. Dashed lines indicate the median cut points, dividing the matrix into four quadrants: Quick wins (high impact, high ease), Strategic bets (high impact, low ease), Low-hanging fruit (low impact, high ease), and De-prioritize (low impact, low ease). Example: Cybersecurity training and secure programs (S4) appear in Quick wins, while Limited bandwidth and infrastructure (C2) appear in Strategic bets. Full item descriptions are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

However, challenges were predominantly positioned in the lower quadrants. The de-prioritize quadrant had initiatives of low impact and high implementation requirements; these included C5, C7, C8, C9, and C10 (Figure 4). These challenges require significant resources but with little yield, making them the last option investments for institutions. Lastly, the low-hanging fruit quadrant had easy-to-implement initiatives with moderate impact. Therefore, management often addresses these first as they provide visible progress with minimal effort. In this quadrant present were three challenges and two solutions these presented: C2, C3, and C6; and S1 and S3, respectively. Taken together, this result shows that while solutions are often feasible and impactful than challenges, they require careful strategic planning when implementing. Highlighting the importance of prioritization, institutions need to balance short-term gains with long-term investments that ensure that digital innovation strategies are both practical and attainable.

4 Discussion

Higher education (HE) systems require digital transformation tailored to specific socio-cultural, economic, and institutional contexts (Amjad et al., 2024). The incorporation of digital systems has led to the development of various teaching methods, including video lectures, interactive simulations, and adaptive learning resources (Al-Fraihat et al., 2020). Although there are significant differences in digitalization that exist between developed and developing countries, HEIs in both contexts adopt a framework with elements that interlink (Ouadoud et al., 2021). We have shown a tripartite structure of a digital innovation framework comprising institutional strategies, technology, and teaching methods (Figure 2). This finding concurs with Jisc's Framework for Digital Transformation in HEIs for the first layer, which highlights leadership as a key factor, essential for resource allocation and stakeholder engagement (Biškupić, 2022). Similar to the Jisc's Framework, our framework recognizes functional roles of digital leadership, stakeholder engagement, and secure infrastructure as critical enablers of digital transformation (Table 1). It argues that without a coherent government and investment in digital capability, technology initiatives risk fragmentation and limited impact. It also emphasizes data equity and ethics with global concerns regarding responsible data use, especially in AI-driven educational environments. To corroborate our findings, another framework, HolonIQ's Higher Education Digital Capability Framework (HEDC), also demonstrates leadership through governance and funding, and provides operational platforms for technological and pedagogical innovations (Leišyte, 2025). The second layer of our framework, technology, involves tools and platforms that facilitate new modes of delivery, administration, and efficiency. These incorporate learning management systems (LMS) into academic institutions, such as the global diffusion of open educational resources (OER) and the democratizing objectives of massive open online courses (MOOCs) (Ouadoud et al., 2021). The HEDC framework further expands this view by segmenting potentials in domains such as digital infrastructure, technology governance, and digital product strategy. Highlighting the importance of integrative operations, cloud connectivity, and identity management in ensuring seamless user experiences and scalable solutions, similar to our findings (Table 1). At present, cloud computing, blockchain systems, and AI-driven analytics use are also increasing. For example, generative tools like ChatGPT and Grammarly which demonstrate a shift toward intelligent augmentation, where technology supports both learners and educators in real-time (Yang, 2025). The third layer, Pedagogy, illustrates how digitalization restructures teaching and learning in HEIs (Figure 2). Suggesting a shift toward learner-centered design through active learning, flipped classrooms, personalized pathways, and AI-driven assessment (Table 1). This observation also aligns with UNESCO's Digital Transformation of Education Systems report (2023), which emphasizes the need to scale up technological solutions in HEIs (Xu and Rakhmatullaev, 2023). Practical tools like adaptive learning systems, immersive AR/VR, and AI-driven feedback are being adopted in HEIs, reshaping and allowing experimentation with cutting-edge technologies, especially in developed countries (Table 3). In Australia, the University of Sydney has integrated virtual reality (VR) into its medical education programs. Enabling students to practice surgical operations and clinical scenarios in a fully immersive setting boosts their abilities and fosters empathy (Table 3). The African Virtual University (AVU) operates in over 20 African countries, delivering degrees and professional courses via online platforms that adapt content to local languages and customs (Mugizi and Nagasha, 2025). Recent frameworks like the Advance HE's Professional Standards Framework (PSF2023) emphasize the need to integrate digital pedagogy into curricula and assessment practices (Akerman and Hunter, 2025).

Most importantly, the layered structure shows that innovation is not merely additive but synergistic. Institutional strategy facilitates technology selection, consequently enabling pedagogical transformation. The Jisc framework also supports this idea by advocating for cross-team approaches and the reduction of complexity, promoting shared understanding and strategic coherence throughout faculties. Our framework also implicitly supports a maturity model of digital transformation, where HEIs evolve from isolated tool adoption to systematic integration and cultural change, showing that digital innovation framework layers extend to broader faculties, interconnecting and creating an ecosystem of both strategy and adaptation in both contexts. A recent comparative study, OECD Digital Education Outlook, suggests that this universality in the layered model lies in its structural logic, while its variability emerges from the contextual realities of implementation (Bo, 2025).

In this research, we also demonstrated that HEIs' digitalization in both contexts follows different trajectories of adoption (Figure 3). In developed countries, there is a rapid uptake beginning at the Early adopter stage and reaching an equilibrium at a high level through the late majority. Suggesting a well-founded infrastructural readiness, policy alignment, and institutional adaptability in developed countries. Similar to adoption in developed countries, integration accelerates modestly during the early majority but declines thereafter. This decline is usually due to structural bottlenecks such as limited digital infrastructure, fragmented policy implementation, and socio-economic constraints that impede scalability and long-term institutionalization (Graham et al., 2013). Interestingly, the inflection points in both adoption approaches of HEIs in both contexts appear around the early majority stage (Figure 3), highlighting that this phase is critical for widespread adoption. The differences in the post-inflection stage suggest that sustained integration is contingent on endogenous capacity and contextual enablers (Figure 2), while the initial adoption may be fastened by global trends or donor-driven initiatives (Graham et al., 2013). Additionally, we hypothesized that the decline in adoption post-Early Majority in developing countries reflects a lack of institutional support and digital governance (Figure 3). These patterns align with the findings of the World Bank's Digital Progress and Trends (2023), which explains the growth of digital innovation globally that remains uneven (Tawil and Miao, 2024). Additionally, the report notes that the top economies account for 70% of global value added in IT services, while small firms in lower-income countries struggle to adopt digital solutions, with fewer than 30% investing in digital tools by 2022. Likewise, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) warns of a widening divide that excludes developing countries from the fourth industrial revolution (Canton, 2021). To further corroborate our findings, the World Economic Forum (2024) has noted that only 36% of individuals in developing countries are online, and that digitalization remains elusive without targeted investment in local innovation ecosystems (Bain et al., 2019).

In total, we assert that digital innovation adoption in HEIs requires a cooperation of multiple factors, including institutional readiness, policy coherence, and socio-economic equity, and not merely the availability of technological tools. Specifically, for developing countries, interventions must go beyond tool deployment to include capacity building for digitalization to move beyond the Early Majority peak, which includes inclusive infrastructure and long-term strategic alignment (Díaz-Arancibia et al., 2024). This also requires a shift from donor-driven projects to locally sponsored digital ecosystems that support sustainable digital tools (Srivastava et al., 2023). In this research, we also imply that in developing countries, early adoption alone is insufficient; thus, sustained integration requires systemic enablers such as faculty development, strategic planning, and ethical data governance.

To assess the adoption and effectiveness of digital innovation in higher education, we used case studies from 20 different universities globally (Table 3). We noted that institutions in countries such as the United States, Germany, and South Korea have strong broadband access, sophisticated learning management systems, and policies that emphasize technology-enhanced learning, probably due to substantial investments in infrastructure, research, and teacher training (Gala et al., 2025). In developed countries, these features are rapidly driven by substantial state support, performance-based research funding, and institutional benchmarks. Countries like Australia and the UK have initiatives such Digital Education Action Plan and the Teaching Excellence Framework, respectively, which fund the digitalization in HEIs (Taguma and Frid, 2024; Outeda, 2024). Developed countries often have integrated digital strategies aligned with national or international frameworks, such as the European Commission's Digital Education Action Plan, which connects educational objectives with digital initiatives (Taguma and Frid, 2024). In comparison, universities in developing countries rely on support from global organizations such as the Gates Foundation, UNESCO, the World Bank, and NGOs (Selwyn, 2014; Singun, 2025). While this support is essential, it sometimes involves models designed externally that may not align well with local teaching styles or infrastructure realities, thereby limiting the success rate of digitalization (Selwyn, 2014). Therefore, in all contexts, without addressing systemic barriers such as resource limitations, policy issues, or mistrust, adoption remains slow even among early innovators (Singun, 2025).

Despite significant advancements in digital educational innovation, several challenges persist that hinder its widespread adoption (Díaz-Arancibia et al., 2024; Farley, 2024). Nonetheless, research has provided tools and concepts that aid higher education institutions in decision-making for digital innovation. For example, the Impact-Feasibility Matrix developed by the Tamarack Institute on innovation poses a concept to evaluate and prioritize ideas based on two dimensions: potential impact and ease of implementation (Megersa, 2019). This matrix challenges universities to identify which initiatives to pursue immediately (Quick Wins), which to invest in strategically (Strategic Bets), and which to defer or reconsider (De-prioritize and Low-hanging). Similarly, the Participatory Methods Framework encourages collaborative placement of ideas to build consensus and transparency in decision-making in the context of digital transformation in HEIs (Smajgl and Ward, 2015). Lastly, the Impact-Effort Matrix, widely used, helps stakeholders to identify tasks that deliver maximum value with minimal effort (Ilbahar et al., 2023). Especially relevant in EdTech and institutional innovation, where resource constraints and demand strategic clarity.

Here, we showed several solutions in the Quick wins quadrant that are both impactful and readily implementable, and ideal for short-term execution and resource-efficient scaling (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). For example, upgrading ICT infrastructure and increasing access which is a high-impact intervention with moderate feasibility (S2). Interventions such as cybersecurity training and secure platforms (S4) are well-defined, highly feasible solutions that can be easily delivered through workshops and low-cost platforms. This approach often leads to immediate and visible results due to its resource intensity. Cheng et al. have proposed eight strategies to mitigate cybersecurity threats, which include: reinforcement of institutional governance for cybersecurity, revisiting cybersecurity KPIs, clarifying cybersecurity policies, guidelines, and mechanisms, enhancing training and cybersecurity awareness, responding and enhancing AI-based cybersecurity, introducing stricter measures, monitoring device usage across campus points, and risk management (Cheng and Wang, 2022). Context-sensitive teacher training (S8) offers the best potential to improve digital competencies with minimal time investment, while focusing on meeting faculty training needs (Radovanović et al., 2015). While engaging stakeholders and implementing incentive mechanisms (S5) and broad-based digital skills training and support (S9) offer rapid, high-impact results. Organizations like the Global Learning Council and the Commonwealth of Learning facilitate knowledge sharing worldwide, helping developing countries access new teaching methods and technologies (Cogburn, 2003).

The strategic bets offered other solutions, including aligning university strategies with national digital initiatives (S6), effective for HEIs to gain increased funding opportunities and legitimacy, while also facilitating coordination, especially under leadership influence (Cheng and Wang, 2022). The introduction of multilingual and inclusive content (S7) is a feasible solution to improve accessibility, with a moderate systemic impact (Monteiro and Leite, 2021). Subsidizing internet is a moderately impactful and highly feasible solution (S10) that can be maintained effectively if internet access is funded through partnerships with telecommunications providers or bulk institutional procurement (Benavides et al., 2020). Innovative solutions, such as SolarSPELL, provide offline digital resources through handheld, solar-powered devices (Hosman et al., 2020). Discussions are increasingly focusing on artificial intelligence, suitable and localized transformations, rather than solely on sustainable development. Noteworthy, in the low-hanging quadrant, we observed the requirement of a curriculum revision (S1) solution, which is of intermediate feasibility. This allows for interaction with curriculum committees and accreditation bodies to extend education time and with faculty to retrain them (Yasin et al., 2024). Thelma et al. have also suggested that aligning digital tools with curriculum goals and supporting faculty enhances technology-enhanced learning (Thelma et al., 2024).

While these solutions are easy to implement and have a high impact, they resolve most of the challenges we presented in the strategic bets and low-hanging quadrants (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2). Challenges in the low-hanging quadrant are easy to address, yielding limited systematic change, useful for incremental improvements. These include Cybersecurity threats (C4), which are of high impact. Post COVID-19, there has been an increased use of personal devices, thus an increase in cybersecurity challenges in the HEI (Alexei and Alexei, 2021), and language and cultural barriers (C10) in strategic bets. In the low-hanging quadrant are: curriculum misalignment (C1), which poses a significant challenge if existing curricula are not aligned with the industry's growing demand for digital innovation (Yasin et al., 2024). Bandwidth and all kinds of infrastructure (C2) constitute a foundational constraint for the adoption of digital innovation. Even in well-resourced higher education institutions, high-speed internet may not be universally accessible throughout (Bashir, 2020). Most importantly, this constraint is prevalent in developing countries. The World Bank report notes that many institutions lag behind technological advancements, especially in third-world countries, reflecting a supply-demand imbalance (Collins, 2011). Vincente et al. characterized the quality of digital infrastructure and resources in Portuguese HEIs, noting that limited infrastructure, such as outdated systems, poor internet, and insufficient resources, is the main barrier to digital innovation (Vicente et al., 2020). In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), these issues are elevated. A survey in Tunisia revealed that over 80% of undergraduate students engage in self-directed activities outside class, such as digital textbooks and language apps (Melliti and Henchiri, 2024). Management and leadership barriers (C6) often cause gaps in vision, resource allocation, or policy guidance (Schneckenberg, 2009). Furthermore, digital projects are hindered by rigid faculty development programs and insufficient support for student autonomy, which limits their usefulness (Lane, 2007).

We also showed some constraints in the de-prioritize quadrant; these are of low impact and low feasibility. Management may not prioritize resolving these. Studies in public sector digital transformation (CAF Development Bank of Latin America, 2022) note that some low-impact, low-feasibility initiatives still hold symbolic exploratory value; institutions may reconsider them in the future (America, 2022). These included resistance to change (C5) that stems from cultural and organizational inactivity that inhibits digital adoption (Mexhuani, 2025; Lane, 2007). Low digital literacy (C7) among teachers and educational staff. Students, particularly those from backgrounds with traditional teaching methods, may struggle to adapt to the self-directed digital learning process; this opposition extends beyond simple technophobia (Singun, 2025). Inadequate professional development (C8) due to underfunded training and retraining programs and economic inequality (C9). Digital education has often involved the unidirectional transfer of content from the Global North to the South (Mays, 2023). In some cases, some projects are delayed or abandoned due to a lack of consistency from funders. For instance, the Global South faces challenges from donor-driven digital education initiatives that often remain as pilots, lacking scalability or integration into national systems (Souza, 2025). Disagreements with local curricula, governance, and policies lead to minimal adoption and project cessation. Sustainable digital efforts require systemic integration, including policies, teacher training, and assessment systems (Yurieva et al., 2021).

5 Conclusion and future perspectives

In this analysis, we have shown distinct patterns, drivers, challenges, and possible solutions of digital innovation in Higher Education Institutes between developed and developing countries. Concluding that while it is imperative to digitalize, the context of occurrence significantly shapes its scalability and ultimately its impact. We also demonstrated that digitalization in developed countries is characterized by a top-down, ecosystem-driven model with primary challenges revolving around ethical data use, digital pedagogies and equitable access. In contrast, we also showed that in developing countries that innovation often develops from bottom top, necessity-driven model. Its impact is often hindered primarily with infrastructural deficits and resource constraints. Despite these challenges, this study has also shown a critical convergence point in digitalization, the importance of human element. A framework of operation, layered into leadership, technological strategies, and pedagogy. Therefore, this is a significant factor for the sustainable innovation of digital systems across contexts. Thus, this study has significant implications for policy makers in developed countries to shift their focus from simple adoption to the ethical integration and pedagogical effectiveness of digital tools. For developing countries, the priority must be public-private cooperation to resolve infrastructural limitations and polices that support the innovation of locally relevant digital tools. Although this study bridges a gap in HEIs' innovation, there are some limitations, including its broad comparative scope, which may overlook variations within contextual categories of developing and developed countries. Additionally, the technology continually evolves rapidly, suggesting that instabilities in the operations of innovation and that this study might require longitudinal study since the impacts of these digital systems are long-term. Future research should, therefore, focus on deeper micro-level case studies of successful implementation in specific socio-economic contexts. Analyzing the return on investment (ROI) of several digital learning models will provide evidence for resource use and allocation. Lastly, future studies should also focus on hybrid translational educational models and the significance of AI in education systems globally.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TW: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. TD: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis. LY: Conceptualization, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. LO: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. DH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Projects of Education Science Planning in Jiangsu Province: Research on the Rotational Cultivation Model for Professional Degree Postgraduates in Forestry Science (Grant Number: B/2023/01/190), and Research Project on Higher Education at Nanjing Forestry University: Research on Pathways to Enhance the Quality of Top Students in the Bioscience Major: A Case Study of the “Zheng Wanjun” Class (Grant Number: 2025B21).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the funder of this research.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1723087/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

HE, Higher education; LMS, Learning Management Systems; OERs, Open educational resources; MOOCs, Massive open online courses; IQRs, Interquartile ranges; LMICs, low- and middle-income countries; POI, Points of intersection; TAC, Technology Adoption Curve; VR, Virtual reality; AI, Artificial intelligence; ROI, Return On Investment.

References

1

Akerman K. Hunter C. (2025). The third way: the contribution of academic quality assurance third spacers to ‘pedagogical partnership'. J. Learn. Dev. High. Educ.33, 1–14. doi: 10.47408/jldhe.vi33.1211

2

Alenezi M. (2023). Digital learning and digital institution in higher education. Educ. Sci.13:88. doi: 10.3390/educsci13010088

3

Alexei L. A. Alexei A. (2021). Cyber security threat analysis in higher education institutions as a result of distance learning. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res,.128–133.

4

Al-Fraihat D. Joy M. Masa'deh R. Sinclair J. (2020). Evaluating E-learning systems success: an empirical study. Comput. Hum. Behav.102, 67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.004

5

Amjad A. I. Aslam S. Tabassum U. Sial Z. A. Shafqat F. (2024). Digital equity and accessibility in higher education: reaching the unreached. Eur. J. Educ.59:e12795. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12795

6

Bain P. G. Kroonenberg P. M. Johansson L. O. Milfont T. L. Crimston C. R. Kurz T. et al . (2019). Public views of the Sustainable Development Goals across countries. Nat. Sustain.2, 819–825. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0365-4

7

Bashir S. (2020). Connecting Africa's Universities to Affordable High-Speed Broadband Internet: What Will it Take?Washington, DC: World Bank.

8

Benavides L. M. C. Arias J. A. T. Serna M. D. A. Bedoya J. W. B. Burgos D. (2020). Digital transformation in higher education institutions: a systematic literature review. Sensors20:3291. doi: 10.3390/s20113291

9

Biškupić I. O. (2022). “Digital strategies in higher education–from digital competences to digital transformation,” in EDULEARN22 Proceedings (Palma, Spain) 8675–8684.

10

Bo N. S. W. (2025). OECD digital education outlook 2023: towards an effective education ecosystem. Hung. Educ. Res. J.15, 284–289. doi: 10.1556/063.2024.00340

11

Bond M. Zawacki-Richter O. Nichols M. (2019). Revisiting five decades of educational technology research: a content and authorship analysis of the British Journal of Educational Technology. Br. J. Educ. Technol.50, 12–63. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12730

12

Bradley V. M. (2021). Learning Management System (LMS) use with online instruction. Int. J. Technol. Educ.4, 68–92. doi: 10.46328/ijte.36

13

CAF Development Bank of Latin America (2022). OECD Public Governance Reviews: The Strategic and Responsible Use of Artificial Intelligence in the Public Sector of Latin America and the Caribbean. Paris: OECD Publishing.

14

Canton H. (2021). “United Nations conference on trade and development—UNCTAD,” in The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021 (London: Routledge).

15

Chakraborty M. Al Rashdi S. (2018). “Venkatesh et al.'s unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) (2003),” in Technology Adoption and Social Issues: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications (IGI Global Scientific Publishing), 1657–1674.

16

Cheng E. C. K. Wang T. (2022). Institutional strategies for cybersecurity in higher education institutions. Information13:192. doi: 10.3390/info13040192

17

Cogburn D. L. (2003). “Globally-distributed collaborative learning and human capacity development in the knowledge economy,” in Globalisation and Lifelong Education: Critical Perspectives (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum).

18

Collins C. S. (2011). Higher Education and Global Poverty: University Partnerships and the World Bank in Developing Countries. New York, NY: Cambria Press.

19

Deroncele-Acosta A. Palacios-Núñez M. L. Toribio-López A. (2023). Digital transformation and technological innovation on higher education post-COVID-19. Sustainability15:2466. doi: 10.3390/su15032466

20

Díaz-Arancibia J. Hochstetter-Diez J. Bustamante-Mora A. Sepúlveda-Cuevas S. Albayay I. Arango-López J. (2024). Navigating digital transformation and technology adoption: a literature review from small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries. Sustainability16:5946. doi: 10.3390/su16145946

21

Farley H. (2024). Changes in Special Education Teacher Roles While Implementing One-to-One Devices in Rural Secondary Public Schools. Huntington, WV: Marshall University.

22

Gala P. M. Namit K. Kidwai H. (2025). “Strategies for enhancing digital skills among Africa's NEET youth,” in The World Bank.

23

Graham C. R. Woodfield W. Harrison J. B. (2013). A framework for institutional adoption and implementation of blended learning in higher education. Internet High. Educ.18, 4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.09.003

24

Gull M. Parveen S. Sridadi A. R. (2024). Resilient higher educational institutions in a world of digital transformation. Foresight26, 755–774. doi: 10.1108/FS-12-2022-0186

25

Hanna D. E. (1998). Higher education in an era of digital competition: emerging organizational models. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw.2, 66–95.

26

Hosman L. Walsh C. Pérez Comisso M. Sidman J. (2020). Building Online Skills in Off-Line Realities: the SolarSPELL Initiative (Solar Powered Educational Learning Library). Chicago, IL: First Monday.

27

Ilbahar E. Kahraman C. Cebi S. (2023). Evaluation of sustainable energy planning scenarios with a new approach based on FCM, WASPAS and impact effort matrix. Environ. Dev. Sustain.25, 11931–11955. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02560-8

28

Imran A. (2023). Why addressing digital inequality should be a priority. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries.89:e12255. doi: 10.1002/isd2.12255

29

Kryukov V. Gorin A. (2017). Digital technologies as education innovation at universities. Aust. Educ. Comput.32, 1–16.

30

Lane I. F. (2007). Change in higher education: understanding and responding to individual and organizational resistance. J. Vet. Med. Educ.34, 85–92. doi: 10.3138/jvme.34.2.85

31

Leišyte L. (2025). “Digital platforms and their usage in higher education human resource management,” in Critical Perspectives on EdTech in Higher Education: Varieties of Platformisation (Princeton, NJ: Springer).

32

Mah D. K. (2016). Learning analytics and digital badges: potential impact on student retention in higher education. Technol. Knowl. Learn.21, 285–305. doi: 10.1007/s10758-016-9286-8

33

Matsieli M. Mutula S. (2024). COVID-19 and digital transformation in higher education institutions: towards inclusive and equitable access to quality education. Educ. Sci.14:819. doi: 10.3390/educsci14080819

34

Mays T. (2023). “Challenges and opportunities for open, distance, and digital education in the global south,” in Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education (Singapore: Springer Nature), 321–336. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-2080-6_20

35

Megersa K. (2019). Designing and Managing Innovation Portfolios. K4D Helpdesk Report.Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12413/14741

36

Melliti M. Henchiri M. (2024). Advancing autonomy in Tunisian higher education: exploring the role of technology in empowering learners. Educ. Technol. Q. 456–483. doi: 10.55056/etq.780

37

Mexhuani B. (2025). Adopting digital tools in higher education: opportunities, challenges and theoretical insights. Eur. J. Educ.60:e12819. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12819

38

Mishra S. (2017). Open educational resources: removing barriers from within. Distance Educ.38, 369–380. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2017.1369350

39

Monteiro A. Leite C. (2021). Digital literacies in higher education: skills, uses, opportunities and obstacles to digital transformation. Rev. Educ. Distancia 21. doi: 10.6018/red.438721

40

Mugizi W. Nagasha J. I. (2025). “E-Learning,” in Conceptualizations of Africa: Perspectives from Sciences and Humanities143–163.

41

Natasia S. R. Wiranti Y. T. Parastika A. (2022). Acceptance analysis of NUADU as e-learning platform using the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) approach. Procedia Comput. Sci.197, 512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2021.12.168

42

Okunlaya R. O. Abdullah N. S. Alias R. A. (2022). Artificial intelligence (AI) library services innovative conceptual framework for the digital transformation of university education. Library Hi Tech40, 1869–1892. doi: 10.1108/LHT-07-2021-0242

43

Ouadoud M. Rida N. Chafiq T. (2021). Overview of E-learning platforms for teaching and learning. Int. J. Recent Contrib. Eng. Sci. IT9, 50–70. doi: 10.3991/ijes.v9i1.21111

44

Outeda C. C. (2024). “European education area and digital education action plan (2021–2027): one more step towards the europeanisation of education policy,” in E-Governance in the European Union: Strategies, Tools, and Implementation (Princeton, NJ: Springer).

45

Radovanović D. Hogan B. Lalić D. (2015). Overcoming digital divides in higher education: digital literacy beyond Facebook. New Media Soc.17, 1733–1749. doi: 10.1177/1461444815588323

46

Rulinawaty R. Priyanto A. Kuncoro S. Rahmawaty D. Wijaya A. (2023). Massive open online courses (MOOCs) as catalysts of change in education during unprecedented times: a narrative review. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA9, 53–63. doi: 10.29303/jppipa.v9iSpecialIssue.6697

47

Santiago C. J. Ulanday M. L. Centeno Z. J. Bayla M. C. Callanta J. (2021). Flexible learning adaptabilities in the new normal: e-learning resources, digital meeting platforms, online learning systems and learning engagement. Asian J. Distance Educ.16, 38–56. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.5762474

48

Schiavenato M. Chu F. (2021). PICO: what it is and what it is not. Nurse Educ. Pract.56:103194. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103194

49

Schmidt D. A. Baran E. Thompson A. D. Mishra P. Koehler M. J. Shin T. S. (2009). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) the development and validation of an assessment instrument for preservice teachers. J. Res. Technol. Educ.42, 123–149. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2009.10782544

50

Schneckenberg D. (2009). Understanding the real barriers to technology-enhanced innovation in higher education. Educ. Res.51, 411–424. doi: 10.1080/00131880903354741

51

Selwyn N. (2014). Digital Technology and the Contemporary University: Degrees of Digitization. London: Routledge.

52

Singun A. Jr. (2025). Unveiling the barriers to digital transformation in higher education institutions: a systematic literature review. Discov. Educ.4:37. doi: 10.1007/s44217-025-00430-9

53

Skenderi F. Skenderi L. (2023). Fostering innovation in higher education: transforming teaching for tomorrow. KNOWLEDGE Int. J.60, 251–255.

54

Smajgl A. Ward J. (2015). Evaluating participatory research: framework, methods and implementation results. J. Environ. Manage.157, 311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.04.014

55

Souza A. D. M. E. (2025). The prospects for international development cooperation in times of geopolitical conflict and resource scarcity. Dev. Policy Rev.43:e70029. doi: 10.1111/dpr.70029

56

Srivastava K. Siddiqui M. H. Kaurav R. P. S. Narula S. Baber R. (2023). The high of higher education: interactivity its influence and effectiveness on virtual communities. Benchmarking31, 3807–3832. doi: 10.1108/BIJ-09-2022-0603

57

Taguma M. Frid A. (2024). Curriculum frameworks and visualisations beyond national frameworks: alignment with the OECD Learning Compass 2030. Paris: OECD.

58

Tawil S. Miao F. (2024). Steering the digital transformation of education: UNESCO's human-centered approach. Front. Digit. Educ.1, 51–58. doi: 10.1007/s44366-024-0020-0

59

Thelma C. C. Sain Z. H. Mpolomoka D. L. Akpan W. M. Davy M. (2024). Curriculum design for the digital age: strategies for effective technology integration in higher education. Int. J. Res.11, 185–201.

60

Traxler J. (2018). Digital literacy: a Palestinian refugee perspective. Res. Learn. Technol.26:1983. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v26.1983

61

Vicente P. N. Lucas M. Carlos V. Bem-Haja P. (2020). Higher education in a material world: constraints to digital innovation in Portuguese universities and polytechnic institutes. Educ. Inf. Technol.25, 5815–5833. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10258-5

62

Xu M. Rakhmatullaev M. (2023). “UNESCO-ICHEI: striving for the digital transformation of global higher education,” in Перспективы развития высшего образования, 176–183. Russian.

63

Yang A. (2025). Generative AI chatbots: the future of grammar and spelling correction in English learning. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol.26, 72–87. doi: 10.1504/IJICT.2025.146909

64

Yasin I. R. Razak A. Z. A. Abdullah Z. Mustafa W. A. Risdianto E. (2024). E-Learning application and teacher autonomy: a comprehensive review. J. Adv. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol.57, 116–133. doi: 10.37934/araset.57.2.220237

65

Yurieva O. Musiichuk T. Baisan D. (2021). Informal English learning with online digital tools: non-linguist students. Adv. Educ.8, 90–102. doi: 10.20535/2410-8286.223896

Summary

Keywords

digital innovation, educational technology, e-learning, learning management systems, massive open online courses, open educational resources

Citation

Wang T, Dai T, Yang L, Osmanova L and Hwarari D (2026) Digital innovation in higher education: comparing approaches in developed and developing countries. Front. Educ. 10:1723087. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1723087

Received

11 October 2025

Revised

28 November 2025

Accepted

23 December 2025

Published

15 January 2026

Volume

10 - 2025

Edited by

Nishant Kumar, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India

Reviewed by

Rahul Pratap Singh Kaurav, Fore School of Management, India

Abílio Afonso Lourenço, University of Minho, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Dai, Yang, Osmanova and Hwarari.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Delight Hwarari, tondehwarr@njfu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.