Abstract

Introduction:

As artificial intelligence (AI) becomes increasingly embedded in educational environments, understanding its role in shaping learners’ self-regulated learning (SRL) and self-directed learning (SDL) has emerged as a central concern in contemporary learning science. While prior studies suggest that AI-driven systems may support planning, monitoring, and autonomy in learning, empirical evidence remains fragmented across contexts, learner groups, and instructional designs. This study synthesizes existing empirical research to systematically examine the magnitude and conditions under which AI-based interventions influence SRL, its dimensions and phases, SDL, and associated learning outcomes.

Methods:

A systematic meta-analysis was conducted following PRISMA guidelines, synthesizing evidence from 32 empirical studies comprising 92 effect sizes and a total of 3,029 participants. The analysis examined overall effects of AI-based interventions on SRL and SDL, disaggregated effects across SRL dimensions (cognitive/metacognitive, motivational/affective, and behavioral regulation) and SRL phases (forethought, performance, and self-reflection), as well as impacts on learning outcomes and academic achievement. Random-effects models were applied, and moderator analyses explored learner characteristics, contextual variables, and AI design features. Sensitivity analyses and publication bias assessments were performed to evaluate the robustness of findings.

Results:

AI-based interventions demonstrated a large and statistically significant positive effect on overall SRL (g = 1.613, p = 0.032) and SDL (g = 1.111, p = 0.043), indicating substantial improvements in learners’ ability to plan, monitor, and regulate their learning while sustaining autonomy and persistence. At the dimensional level, AI produced moderate gains in cognitive/metacognitive regulation (g = 0.377, p = 0.0004) and motivational/affective regulation (g = 0.505, p = 0.013), whereas effects on behavioral regulation were inconsistent. Phase-level analyses revealed that AI interventions were most effective during the forethought phase, supporting goal setting, planning, and motivational readiness, with smaller but significant gains observed in self-reflection and variable effects during the performance phase. AI systems also yielded moderate improvements in learning outcomes and achievement (g = 0.350, p = 0.034). Moderator analyses indicated stronger SRL effects among older learners, longer intervention durations, and language learning contexts employing interactive AI systems, while gender differences were minimal. Sensitivity and publication bias tests confirmed the stability of results.

Discussion:

The findings indicate that AI functions as an adaptive scaffold that meaningfully enhances learners’ self-regulatory and self-directed capacities across cognitive, motivational, and reflective processes. By strengthening forethought and planning mechanisms in particular, AI-based interventions support more autonomous, sustained, and effective learning behaviors that translate into measurable academic benefits. Variability in behavioral regulation outcomes highlights the need for more explicit action-level supports in AI design. Overall, the results showcase AI’s potential to promote equitable and scalable self-regulated learning across diverse educational contexts, while also pointing to the importance of aligning intervention design with learner characteristics and instructional goals.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence now permeates the learning lifecycle. Learners plan and decompose tasks using generative planners (Ruan and Lu, 2025) and code assistants (Gonçalves and Gonçalves, 2024; Benkhelifa et al., 2025). They practice with adaptive mastery systems (Oubagine et al., 2025), consult conversational tutors for explanations and hints (Barrot, 2024; Jyothy et al., 2024), and track progress through analytics dashboards that visualize pace and performance (Kannan and Zapata-Rivera, 2022). Institutions deploy AI to scaffold feedback at scale, personalize learning sequences, and surface at-risk signals in real time. Across modalities and domains—including writing, programming, clinical reasoning and benchmarking (Raman et al., 2024)—AI augments access to explanation, exemplars, and iterative practice. Early findings consistently report short-term performance gains on proximal tasks and improved user experience through rapid feedback and reduced friction (Singh, 2025; Diwakar et al., 2024). Across studies, AI supports are associated with meaningful improvements in self-regulation and achievement, though effects vary markedly across contexts, measures, and designs (Molenaar, 2022). At the same time, AI alters the microeconomics of study by shifting where effort is spent: sense-making, drafting, and revision are increasingly mediated by tools that can propose strategies or generate partial solutions (Kolil et al., 2025).

Two design currents are reshaping learner–tool interaction. First, assistance is becoming context-aware (Kavitha et al., 2025): models condition guidance on learner state, history, and task complexity, enabling just-in-time prompts that target planning, monitoring, or error remediation. Second, assistance is becoming ambient: suggestions arrive proactively—autocomplete, auto-hints, dashboards that nudge—blurring the boundary between learner-initiated help and tool-initiated intervention (Cohn et al., 2025). These trends promise stronger scaffolds for metacognitive monitoring, effort regulation, and time management. They also extend beyond formal instruction to support self-directed practice through recommenders and schedule optimizers. Rich behavioral traces (clickstreams, revision logs, planning events) now allow fine-grained observation of regulatory processes, creating opportunities to link tool affordances to changes in self-regulation and self-direction rather than only to end scores (Wang and Lin, 2023). Evidence also points to more consistent gains in cognitive/metacognitive and motivational regulation, whereas behavioral regulation shows mixed and context-dependent results, a pattern echoed in immersive and metaverse-based learning contexts (Raman et al., 2025).

Self-regulated learning (SRL) involves three phases: forethought, performance, and self-reflection (Zimmerman and Moylan, 2009). In the forethought phase, learners set goals, plan strategies, and draw on motivational beliefs to initiate learning. During the performance phase, they carry out the task, monitor progress, and apply self-control strategies to maintain focus and motivation. In the self-reflection phase, learners evaluate their performance and make attributions for success or failure, shaping their motivation and future approach. SRL integrates cognitive/metacognitive processes (rehearsal, elaboration, planning, monitoring, evaluation), motivational/affective regulation (goal orientations, task value, self-efficacy, anxiety management), and behavioral regulation (environment structuring, time management, effort regulation, help seeking) (Seban and Urban, 2024). Self-directed learning (SDL) extends regulation into learner-initiated goal setting, resource curation, and sustained practice beyond instructor scaffolds. Learning outcomes are distal expressions of these processes—achievement, knowledge or skill growth, and task-specific competencies (Aljafari, 2021). Because existing studies differ widely in delivery mode (Hu and Zhang, 2025), scaffold intensity (Liao et al., 2024), assessment timing (Lee et al., 2025), and learner characteristics, the present analysis treats these as interpretive lenses rather than formal moderators, situating observed variability within broader design and contextual differences.

Despite rapid diffusion, empirical evidence on how AI interventions influence SRL and SDL remains broad and uneven. Most studies report global SRL (Du, 2025; Wang W. S. et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Han I. et al., 2025) or SDL (Xu G. et al., 2025; Pan et al., 2025b) scores that aggregate across dimensions, limiting insight into which regulatory processes—planning, monitoring, effort regulation, or motivation—and which phases—forethought, performance, or self-reflection—benefit most. Likewise, while assistance delivery modes (solicited vs. unsolicited) and AI affordances (e.g., generative tutors, adaptive practice, analytics dashboards, planners) likely condition outcomes, few studies report or disaggregate effects by these factors, contributing to high between-study variability. Mediation mechanisms linking SRL/SDL changes to performance outcomes are also rarely tested (Ma et al., 2025; Han J. W. et al., 2025), leaving unclear whether process improvements drive achievement gains. Measurement practices diverge as well: short interventions rely mainly on self-report instruments, whereas behavioral traces and multimodal data remain underused or misaligned with theoretical constructs (Cloude et al., 2022). These gaps motivate the present meta-analysis. The specific research questions addressed as part of this study include:

RQ1. What is the overall effect of AI-based interventions on users’ self-regulated learning across educational levels and subject domains?

RQ2. Across different categories of AI tools (e.g., conversational agents, intelligent tutoring systems, adaptive recommendation systems), which SRL dimensions—cognitive/metacognitive, motivational/affective, or behavioral—show the greatest improvement?

RQ3. Which phases of the SRL cycle (forethought, performance, self-reflection) are most positively influenced by AI-based interventions across contexts?

RQ4. To what extent do improvements in SRL processes mediate the relationship between AI interventions and learning performance?

RQ5. What is the effect of AI-based interventions on users’ self-directed learning, and does this effect differ across educational contexts?

This paper makes several key contributions to advancing our understanding of how artificial intelligence (AI) influences learner regulation and autonomy. First, it establishes a cohesive conceptual bridge between self-regulated and self-directed learning, clarifying their overlaps and distinctions within AI-supported education. Second, it introduces a theoretically grounded classification of AI affordances, mapping feedback, adaptive, and generative systems to specific regulatory levers across cognitive, motivational, and behavioral dimensions. Third, it enhances methodological rigor by aligning effect-size coding with SRL phases and dimensions. Fourth, it identifies key design- and learner-related moderators that shape how AI systems influence regulatory processes. Finally, the paper offers a mediation-oriented interpretive framework that positions AI not merely as a performance enhancer but as an adaptive scaffold capable of internalizing regulation and sustaining learner autonomy beyond technological dependence.

2 Literature review

2.1 Self-regulated and self-directed learning

Self-regulated learning is typically conceptualized across three interlocking layers: cognitive and metacognitive regulation (planning, monitoring, evaluation, elaboration, critical thinking), motivational and affective regulation (goal orientations, task value, self-efficacy, anxiety control), and behavioral regulation (time management, effort regulation, environment structuring, help seeking) (Tinajero et al., 2024). Widely used instruments such as the MSLQ, MAI, and related subscales map onto these layers and generally demonstrate acceptable reliability, although their sensitivity to short interventions varies—metacognitive self-regulation tends to shift more readily than effort regulation (Wang et al., 2023). Across domains, metacognitive monitoring and effort regulation show the strongest associations with achievement, while planning and time management are consistent predictors of persistence and timely submission. However, continued reliance on global SRL totals obscures which specific dimensions respond to instructional or technological conditions, limiting explanatory power and design relevance (Quick et al., 2020). Methodologically, the field remains dominated by self-report measures, which introduce common-method bias and offer limited temporal fidelity. In contrast, behavioral traces—such as revision events, progress-view checks, help-seeking logs, and adherence to study plans—provide fine-grained, time-aligned indicators of regulation and are well suited for testing process-to-performance linkages (Li et al., 2018). The emerging consensus is to retain SRL change as an important endpoint while prioritizing disaggregated, theory-aligned indicators that reveal which regulatory levers shift and whether those shifts translate into performance gains.

Self-directed learning extends regulation beyond instructor-defined tasks to learner-initiated goal setting, resource selection, and sustained out-of-class practice (Han et al., 2022). Core facets include self-management (planning across weeks), self-monitoring (tracking progress toward self-set milestones), motivation (persistence without external prompts), and interpersonal skills (seeking mentors or peers) (Liu M. et al., 2025). SDL inventories assessing ability, motivation, self-management, self-monitoring, and interpersonal skills are frequently used, complemented by behavioral indicators such as voluntary study time, diversity of resources, and schedule adherence. Evidence suggests that SDL can be strengthened through scaffolds that support planning and routine maintenance; however, its effects are under-reported relative to SRL and are sometimes conflated with broader motivational constructs (Aljafari, 2021). The literature also remains unclear on how improvements in SDL behaviors under AI-supported conditions relate to broader learning outcomes, an issue that connects SDL to mediation processes within adaptive learning contexts.

2.2 AI affordances and contextual influences on SRL/SDL

AI-based learning interventions can be grouped according to their primary regulatory affordances. Feedback and coaching agents, which provide explanations or reflective prompts, primarily engage learners’ metacognitive monitoring and evaluation processes (Li and Fan, 2025). Adaptive practice and mastery systems enhance self-efficacy, persistence, and effort regulation by aligning task difficulty with learner progress. Analytics dashboards that embed metacognitive nudges promote planning, progress monitoring, and effective time management. Planning and co-authoring tools—such as large language model planners or code assistants—support goal setting and task strategy development, while conversational intelligent tutoring systems foster elaboration and critical thinking (Liu Y. et al., 2025). The mode of assistance delivery also matters: user-initiated (solicited) support tends to preserve autonomy and promote deeper engagement, whereas proactive (unsolicited) prompts may introduce automation bias and reduce active reflection. The granularity of support—whether aimed at individual tasks or entire courses—and the degree to which scaffolds are gradually faded influence whether regulatory skills are internalized or merely displaced by tool-driven assistance (Xia, 2025). Together, these distinctions illustrate how specific AI affordances align with different facets of self-regulated and self-directed learning.

Outcomes vary systematically with design and context. The mode of assistance delivery—solicited versus unsolicited—shapes learner autonomy and reliance, while scaffold intensity and fading plans determine whether regulation is internalized rather than substituted by the tool (Lim et al., 2024). Assessment proximity also matters: near-transfer, immediate tests tend to yield larger effects than far-transfer or delayed assessments. Learner characteristics, such as prior knowledge and baseline self-regulation or self-direction, condition responsiveness to the same intervention (Mihalca and Mengelkamp, 2020). Domain and task complexity determine which regulatory mechanisms are most consequential—for example, monitoring in programming versus elaboration and revision in writing—and study setting and duration (laboratory sessions versus semester-long courses) influence the visibility of effort-regulation signals (Han et al., 2024). In addition, the quality of explanations and the presence of uncertainty signaling moderate reliance on AI outputs by inviting critical scrutiny or encouraging over-trust. Attending to these moderators helps reconcile inconsistent findings in the literature, attribute observed changes to the most plausible regulatory mechanisms, and identify the conditions under which process improvements translate into measurable performance gains.

2.3 Linking AI, regulation, and learning outcomes

A central proposition in this literature is that AI influences proximal regulatory processes that subsequently yield distal performance gains (Liu et al., 2024; Lim et al., 2023; Afzaal et al., 2024). Yet formal mediation tests remain comparatively rare, often constrained by single-time self-reports, brief interventions, or insufficient statistical power. Where repeated measures are available, increases in monitoring, self-explanation, or plan quality have been shown to predict later task accuracy and productivity, partially accounting for observed treatment effects (Tomisu et al., 2025). Behavioral mediators—including adherence to study schedules, frequency of progress checks, and revision density—provide temporally precise pathways from process to outcome, but remain underused and inconsistently reported (Pacheco et al., 2025). Boundary conditions such as assistance delivery mode (solicited versus unsolicited) (Nair et al., 2025) and the presence or absence of scaffold fade likely modulate mediated effects, underscoring the need to document these design features alongside outcomes. Taken together, the evidence supports more systematic mediation analyses that combine validated self-report indices with aligned behavioral traces to determine whether shifts in specific regulatory processes function as mechanisms linking AI interventions to performance (Sadykova et al., 2024).

Most prior meta-analytic studies have examined the influence of self-regulated learning (SRL) on academic outcomes, positioning SRL as the core intervention variable. Zhao et al. (2025) showed that specific SRL strategies predict academic achievement in online and blended learning environments, with time management and effort regulation emerging as key determinants. Chen (2022) concluded that SRL-focused interventions enhance performance while strengthening motivation and strategic autonomy in second language learning. Similarly, Lee and Chang (2025) found that self-directed learning (SDL) significantly improves performance, engagement, and problem-solving in K–12 digital learning contexts in comparison to traditional approaches. These findings demonstrate the positive impact of SRL and SDL on learning. Building on this foundation, the present study investigates how artificial intelligence (AI) interventions shape both SRL and SDL, and examines whether AI-mediated regulatory processes influence or mediate the relationships between SRL/SDL and learning outcomes.

Despite the progress of SRL- and SDL-focused meta-analyses, the literature on AI-supported regulation remains conceptually fragmented and unevenly synthesized. Existing studies often examine isolated affordances—feedback agents, dashboards, adaptive practice systems, or LLM-based planners—without integrating effects across cognitive, motivational, and behavioral regulation or across SRL phases. Moreover, AI-focused studies vary widely in design, context, scaffolding intensity, and measurement granularity, making it difficult to determine which regulatory processes are most responsive to AI support and under what conditions these improvements translate into performance gains. Few reviews address SDL in AI-supported contexts, and even fewer examine whether AI-mediated regulation serves as a mechanism linking SRL/SDL to outcomes. These gaps highlight the need for a multi-dimensional synthesis that integrates SRL dimensions, SRL phases, SDL components, and outcome pathways. The present meta-analysis addresses this need by consolidating evidence across 32 empirical studies, examining sources of variability, and identifying where AI interventions reliably strengthen regulatory processes and autonomy.

3 Methodology

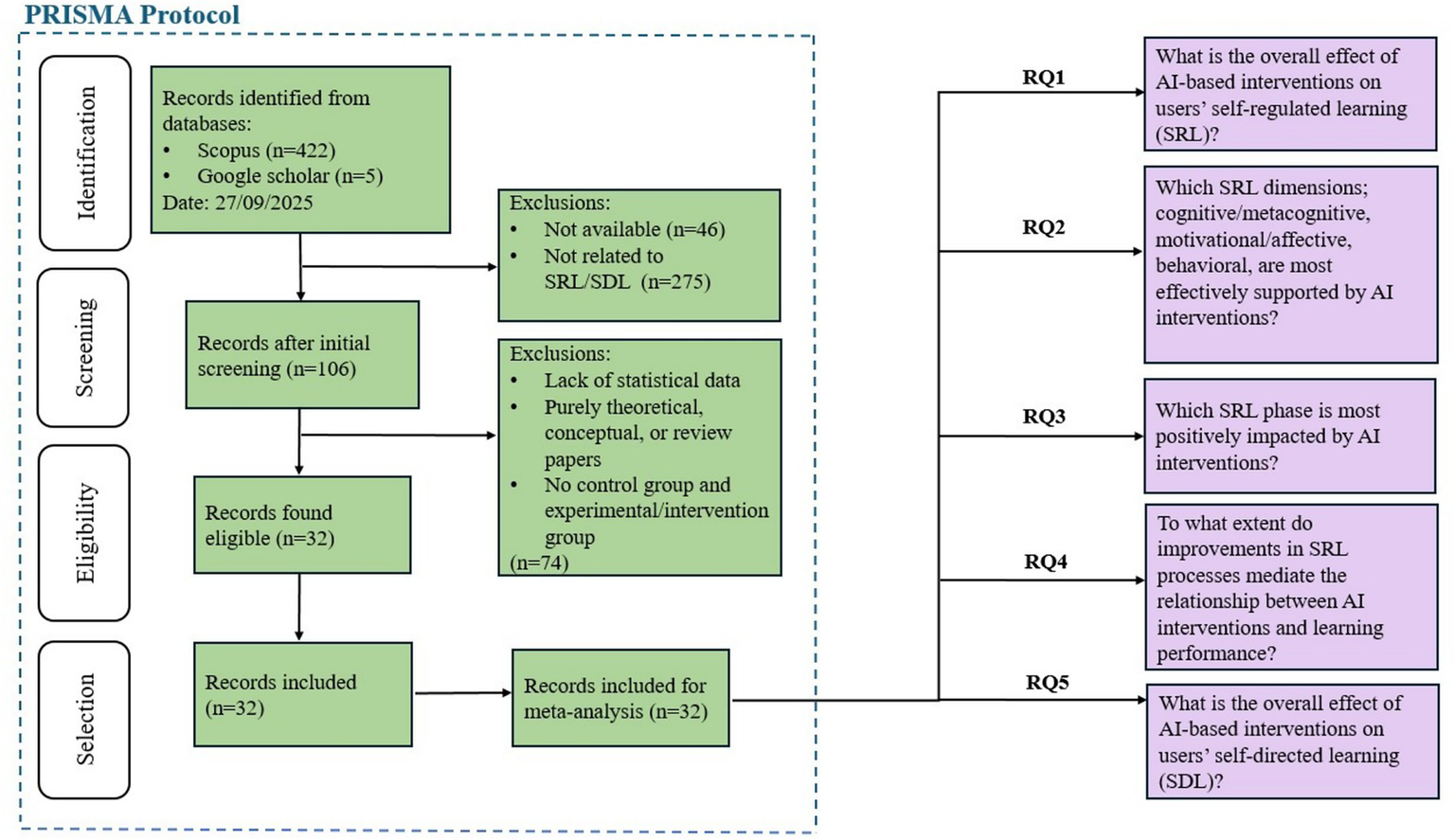

To quantitatively consolidate evidence on how artificial intelligence (AI) interventions influence learners’ self-regulated and self-directed learning, this study employed a systematic meta-analytic approach. Meta-analysis was chosen to integrate findings from empirical studies that differ in design, context, and measurement yet collectively examine how AI supports regulation and autonomy. This approach enabled the estimation of overall and dimension-specific effect sizes, the identification of consistent patterns across cognitive, motivational, and behavioral processes, and the examination of conditions under which AI support is most effective. All procedures followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor (Figure 1).

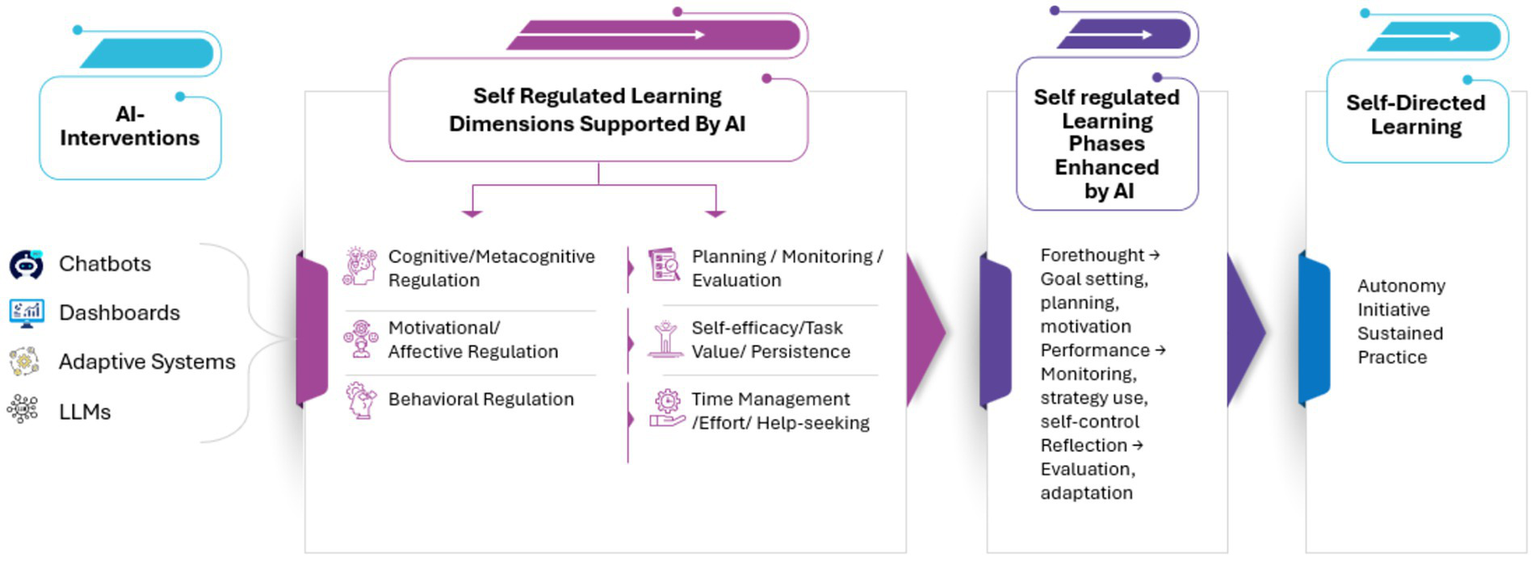

Figure 1

Research framework.

3.1 Literature search

A literature search was conducted on 27th September 2025 across the databases, Scopus and Google Scholar. The following search query was used: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“artificial intelligence” OR “AI” OR “chatbot” OR “genAI” OR “gen AI” OR “generative AI” OR “generative artificial intelligence”) AND (“self-regulated learning” OR “SRL” OR “self-regulated learning” OR “self-regulated learn*” OR “self-directed learning” OR “self-directed learn*” OR “self-directed learning” OR “self-guided learn*”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2019 AND PUBYEAR < 2027 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “re”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)). This search query was designed to retrieve all available documents containing terms related to both AI and SRL / SDL, which resulted in 427 documents.

3.2 Data selection

A rigorous set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was established to ensure the relevance, methodological quality, and comparability of studies included in the meta-analysis. Studies were included if they (a) focused on AI interventions targeting SRL or SDL, (b) employed quantitative designs with extractable statistical data (e.g., means, standard deviations), and (c) included both an experimental group and a control group to enable direct comparison of intervention effects. Studies were excluded if they (a) lacked sufficient quantitative data for effect size estimation, (b) were purely theoretical, conceptual, or review papers, or (c) lacked both control and experimental groups. These rigorous selection criteria narrowed the dataset to 32 studies, contributing 92 effect sizes and involving 3,029 participants. Across these studies, the age of participants ranged from 18 to 37 years, with median ages between 19 and 24, reflecting the predominance of undergraduate and early postgraduate learners. The learning domains represented a diverse set of instructional contexts, including language learning, STEM fields, and medical education, among others. The AI tools employed across the studies encompassed a broad spectrum, including conversational and interactive systems (e.g., Rasa, Dialogflow, Chatfuel, ReadNate, Codeflow Assistant, KI-based “ReadToMe” tutor, Study Buddy SRL chatbot), adaptive and instructional systems (e.g., LLaMA-based AI textbooks, reinforcement-learning agents using PPO in OpenAI Gym), and supportive or analytical tools (e.g., Google Speech-to-Text API, rule-based SRL scaffolding engines, analytics-enhanced feedback systems).

Different studies emphasized varied aspects of SRL and related constructs. The extracted factors were organized into five main categories: overall self-regulated learning, SRL dimensions, SRL phases, learning outcomes and performance, and self-directed learning. The overall SRL category included studies measuring composite self-regulation scores (Shafiee Rad, 2025; Klar, 2025; Liu et al., 2023). The SRL dimensions category captured the cognitive/metacognitive (planning, monitoring, and evaluation) (Huang et al., 2025; Pan et al., 2025a), motivational/affective (goal orientation, self-efficacy, and emotional control) (Wei, 2023), and behavioral (time management, effort regulation, and environment structuring) components of regulation (Huang et al., 2023). The SRL phases category encompassed the forethought, performance, and self-reflection phases. The forethought phase involves preparatory processes such as goal setting, strategic planning, and activation of motivational beliefs. The performance phase includes attention focusing, strategy use, progress monitoring, and self-control during task execution. The self-reflection phase involves evaluating performance, forming attributions, and generating adaptive or defensive reactions that guide future behavior. The learning outcomes and performance category included measures such as achievement, skill development, and knowledge acquisition (Chun et al., 2025; Tang et al., 2025; Wang P. et al., 2025). Finally, the SDL category reflected learners’ capacity for autonomous goal setting, self-management, and monitoring beyond formal instruction (Li et al., 2025; Behforouz and Al Ghaithi, 2024).

This categorization ensured conceptual clarity and analytical precision in the meta-analysis. Since SRL is a multifaceted construct encompassing cognitive, motivational, affective, and behavioral components, organizing factors under these dimensions supported a structured examination of how AI interventions influence different aspects of regulation. Similarly, grouping factors by SRL phase enabled a process-oriented analysis that reveals where AI support is most impactful. Distinguishing learning outcomes and performance allowed for the assessment of how regulatory improvements translate into academic gains. Finally, treating SDL as a separate category acknowledged its conceptual overlap with SRL while preserving its distinct emphasis on autonomy and learner-initiated regulation. Overall, this grouping enhances interpretive coherence, aligns with established SRL frameworks (Pintrich, 2000; Zimmerman and Moylan, 2009), and supports meaningful synthesis across studies with varied operationalizations of learning constructs.

3.3 Meta-analytic procedure

Before conducting the meta-analysis, we coded data such as study name, publication year, sample size, and the mean and standard deviation values for both the control and experimental groups. The meta-analysis was performed in R and was carried out across the five main groups as well as their respective subgroups. The standardized mean difference (Hedges’ g) was used to calculate effect sizes. For groups in which studies reported multiple effect sizes, a random-effects model with Robust Variance Estimation (RVE) was applied. For groups containing studies with only a single effect size, a standard random-effects model was used. To assess the robustness and validity of the findings, moderator analyses, sensitivity analyses, and publication bias tests were subsequently conducted.

4 Results

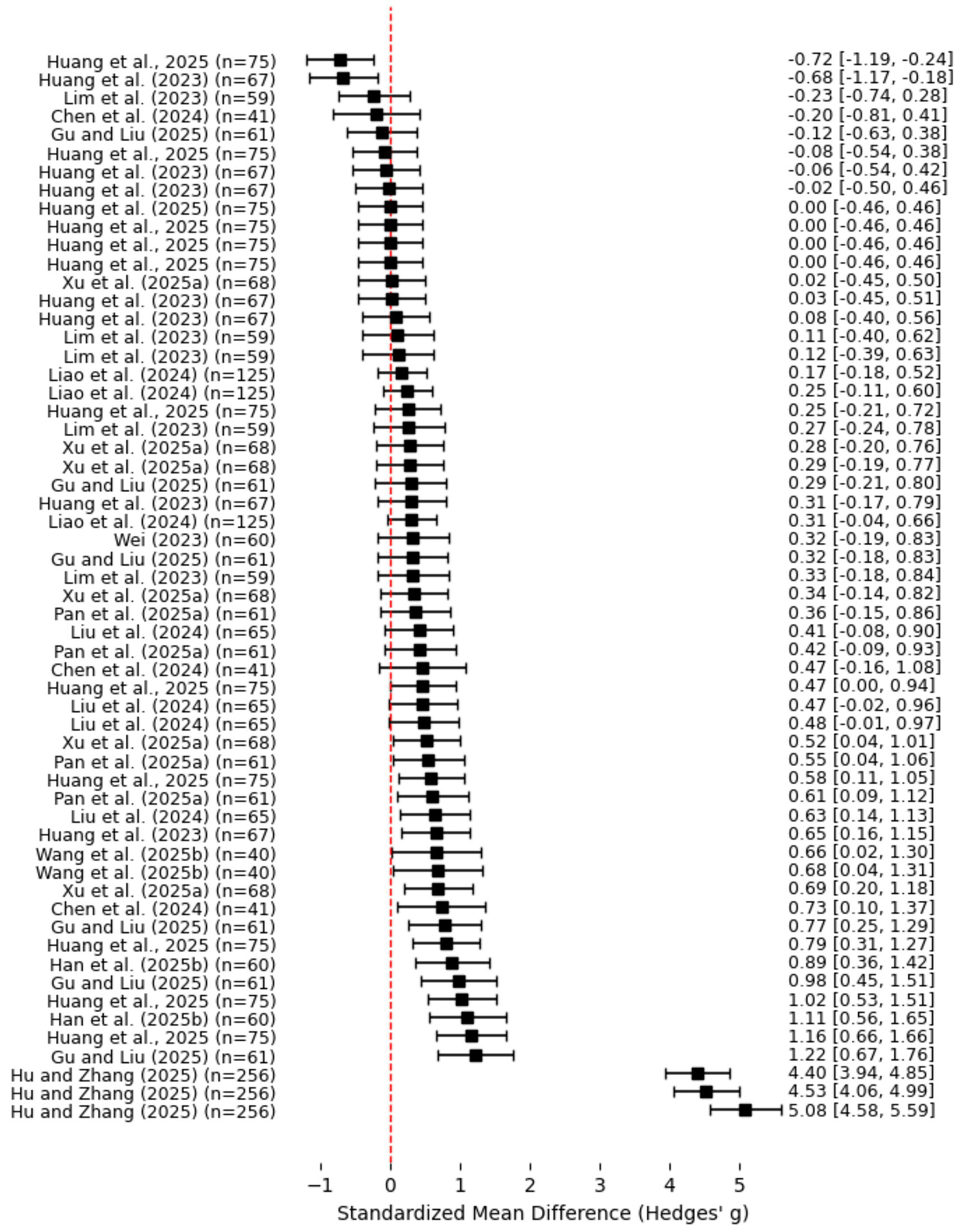

4.1 Meta-analysis

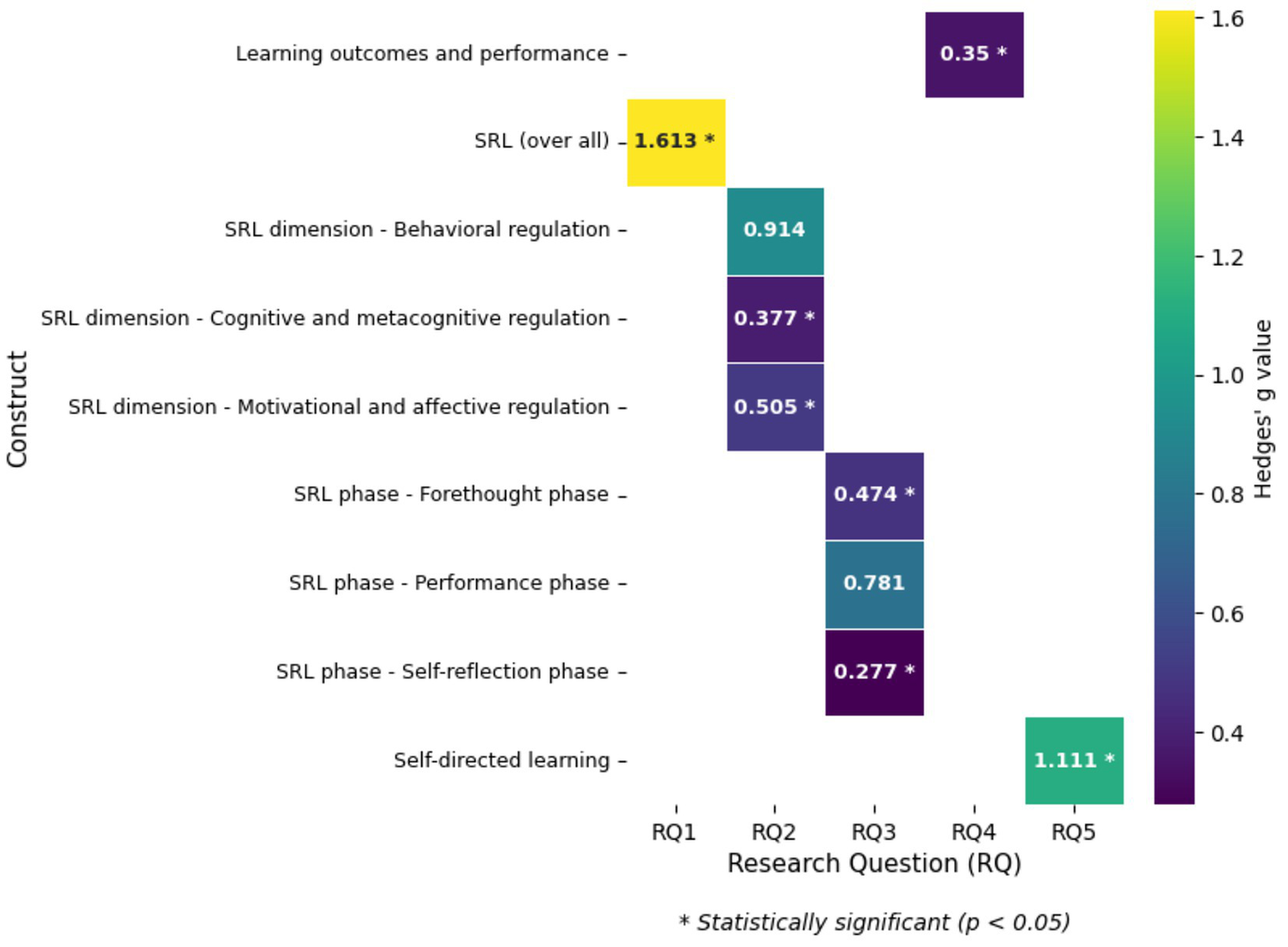

The effect sizes are reported using Hedges’ g, along with 95% confidence intervals, significance levels (p-values), and heterogeneity indicators (I2 and tau-squared), as summarized in Table 1. In the ‘g’ column, red colored font in italics highlight significant effect sizes, and standard font represents non-significant ones. Figure 2 offers a heatmap representation that contrasts significant and non-significant effects across research questions and constructs, highlighting variations in effect size magnitude.

Table 1

| Sl no. | Factors | No. of studies | No. of effect sizes | g | SE | 95% CI | p | Test for heterogeneity | Interpretation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL |

(%) |

τ 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | SRL (over all) | 11 | 11 | 1.6127 | 0.7531 | 0.1366 | 3.0887 | 0.0322 | 98.85 | 6.1332 | Large positive effect |

| 2 | SRL dimensions | 13 | 58 | 0.7394 | 0.3365 | 0.0063 | 1.4725 | 0.0484 | 96.11 | 1.5943 | Large positive effect |

| Cognitive and metacognitive regulation | 10 | 29 | 0.3767 | 0.0676 | 0.2225 | 0.5308 | 0.0004 | 30.98 | 0.0287 | Small-to-moderate positive effect | |

| Motivational and affective regulation | 6 | 13 | 0.5051 | 0.1330 | 0.1608 | 0.8494 | 0.0132 | 56.48 | 0.0814 | Moderate positive effect | |

| Behavioral regulation | 6 | 16 | 0.9144 | 0.7624 | −1.0454 | 2.8742 | 0.2841 | 98.32 | 3.703 | Large positive effect | |

| 3 | SRL phases | ||||||||||

| Forethought phase | 10 | 17 | 0.4739 | 0.0959 | 0.2561 | 0.6916 | 0.0009 | 43.91 | 0.0493 | Moderate positive effect | |

| Performance phase | 11 | 36 | 0.7809 | 0.3981 | −0.1061 | 1.668 | 0.0782 | 96.69 | 1.8529 | Large positive effect | |

| Self-reflection phase | 10 | 13 | 0.2774 | 0.1164 | 0.0128 | 0.542 | 0.0418 | 67.55 | 0.0982 | Small positive effect | |

| 4 | Learning outcomes and performance | 7 | 9 | 0.3502 | 0.1264 | 0.0379 | 0.6626 | 0.0338 | 69.04 | 0.0971 | Small-to-moderate positive effect |

| 5 | Self-directed learning | 8 | 14 | 1.1111 | 0.4484 | 0.0457 | 2.1764 | 0.0431 | 91.14 | 0.5321 | Large positive effect |

Meta-analysis result.

I 2: proportion of variability due to heterogeneity; τ2: magnitude of variance.

Figure 2

RQ vs. constructs heatmap.

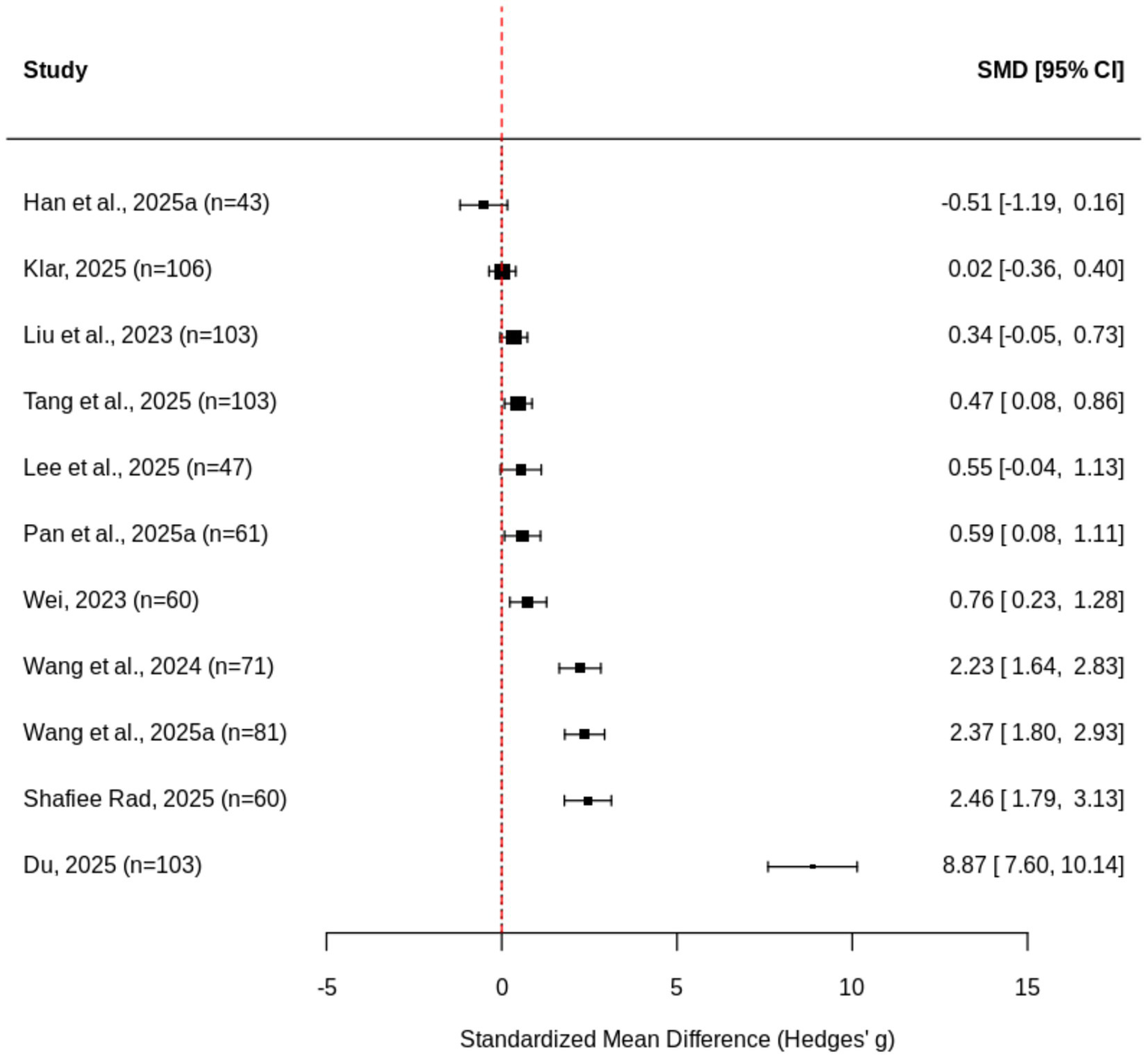

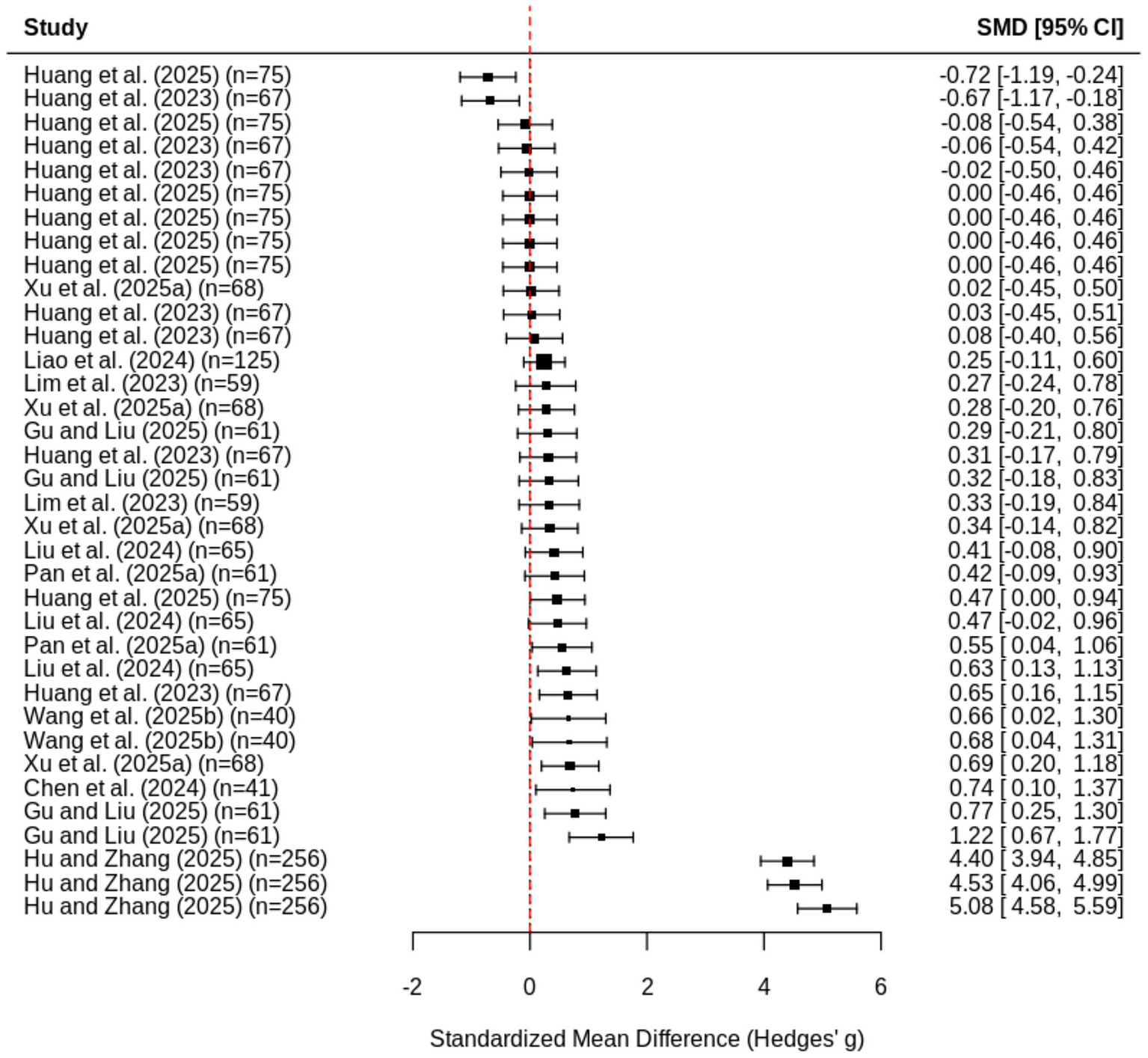

4.1.1 Overall SRL effects

The meta-analysis revealed that AI-based or related interventions had a large and statistically significant positive effect on overall SRL (g = 1.613, p = 0.032), indicating substantial improvements in learners’ SRL (Figure 3). However, heterogeneity was extremely high (I2 = 98.85%, τ2 = 6.133), suggesting considerable variability across studies due to differences in SRL measurement methods, participant characteristics, or intervention designs. These results directly address RQ1 by showing that AI interventions produce substantial gains in learners’ overall self-regulation. In practical terms, this means learners become more capable of planning, monitoring, and adjusting their learning processes when supported by AI systems.

Figure 3

Forest plot of overall SRL.

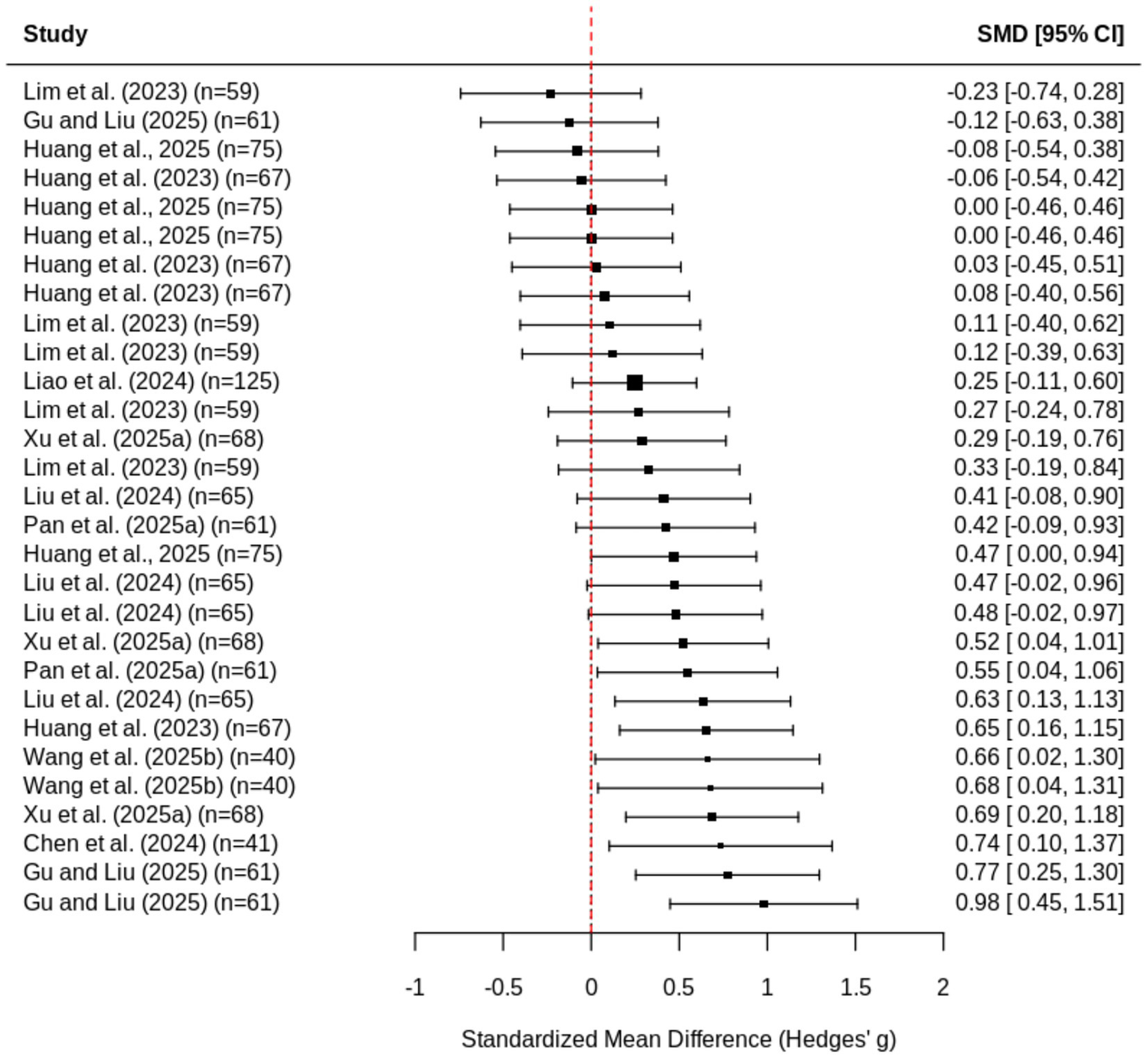

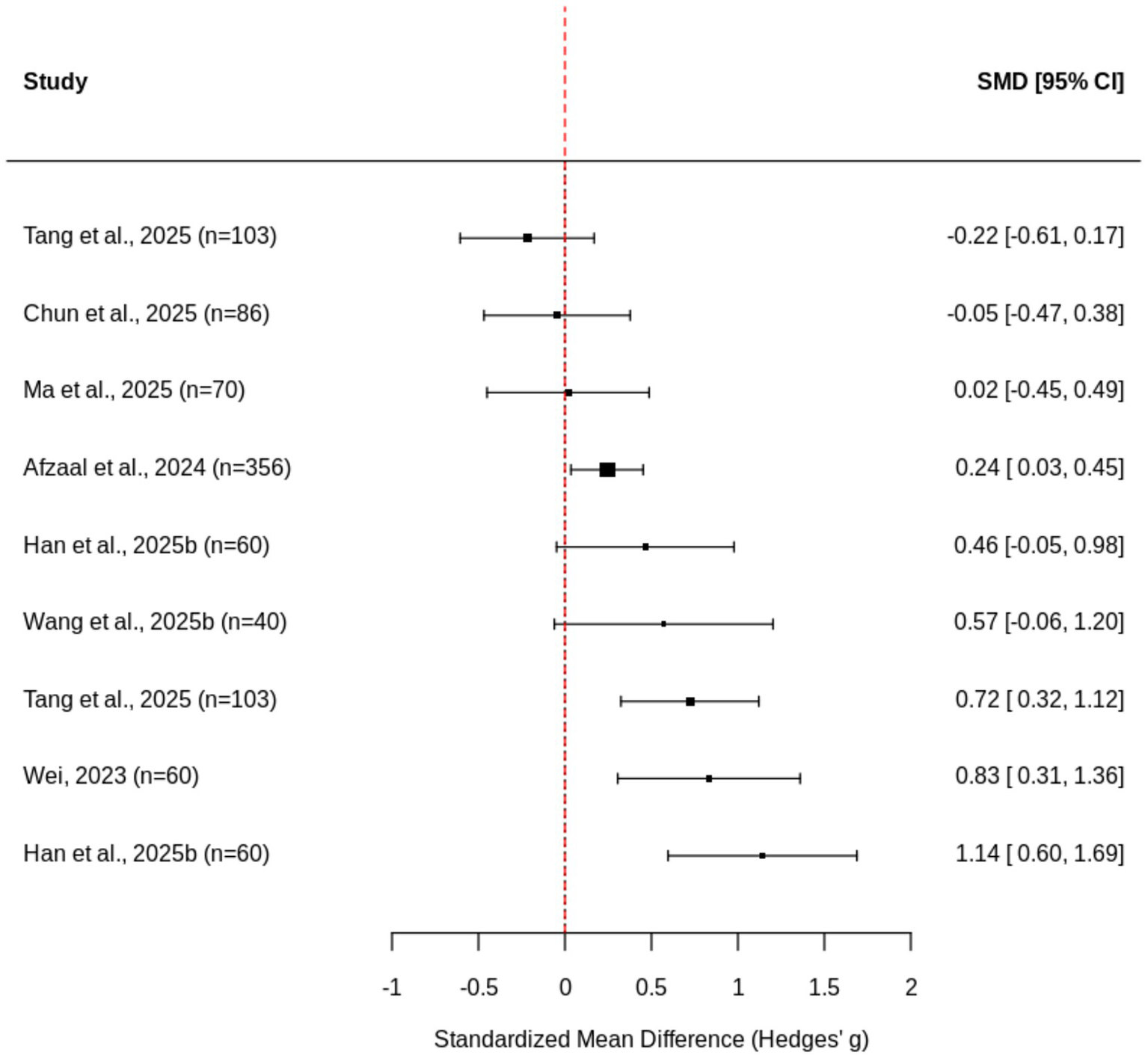

4.1.2 SRL dimensions

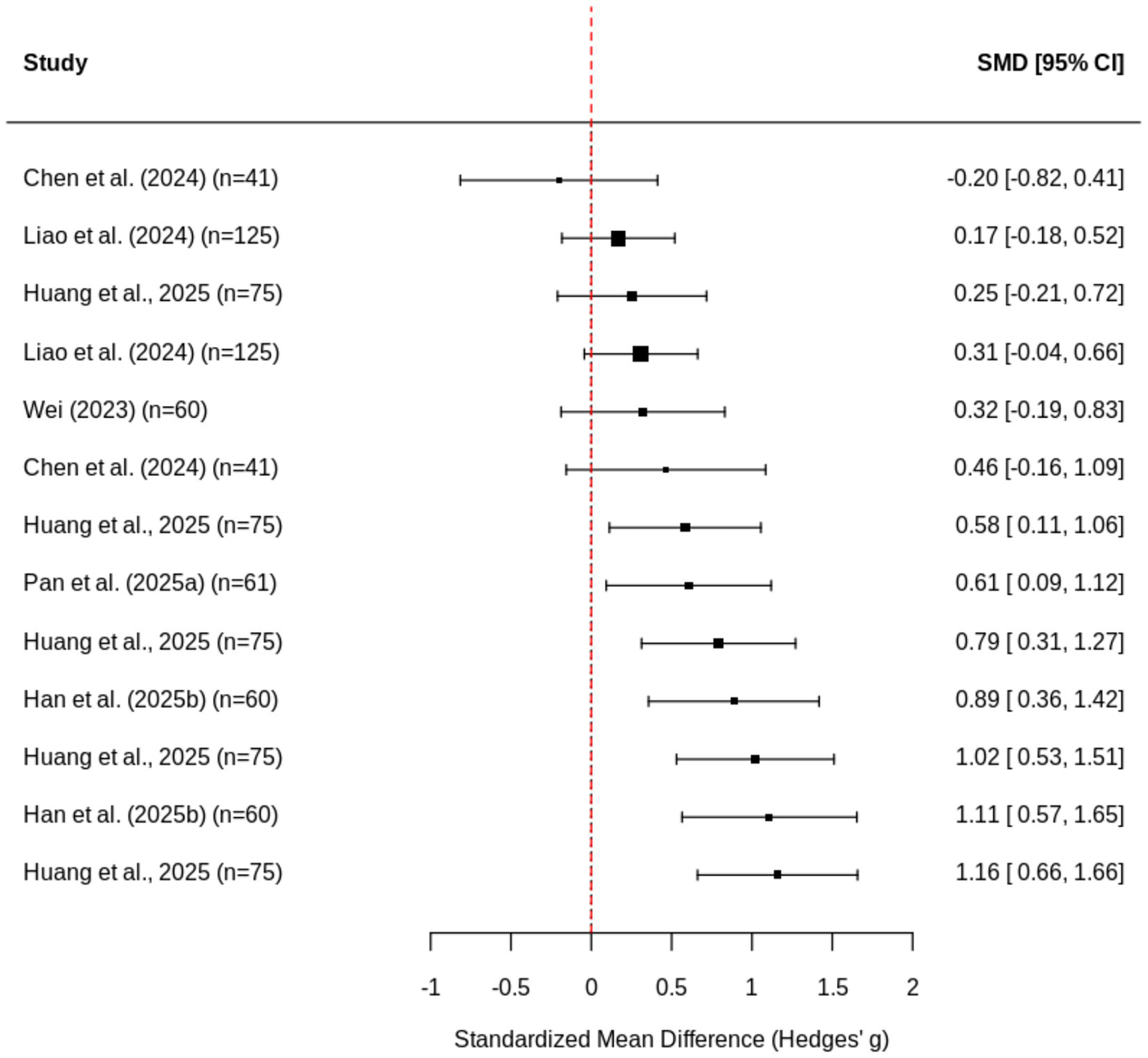

Examining SRL dimensions, interventions produced a small-to-moderate positive effect on cognitive and metacognitive regulation (Figure 4) (g = 0.377, p = 0.0004) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 30.98%, τ2 = 0.029), a moderate positive effect on motivational and affective regulation (Figure 5) (g = 0.505, p = 0.013) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 56.48%, τ2 = 0.081), and a non-significant effect on behavioral regulation (Figure 6) (g = 0.914, p = 0.284) with extremely high heterogeneity (I2 = 98.32%, τ2 = 3.703), indicating inconsistent outcomes across studies. Interventions showed a large positive effect on SRL dimensions (Figure 7) (g = 0.739, p = 0.048), though heterogeneity remained very high (I2 = 96.11%, τ2 = 1.5943), suggesting that the effectiveness of interventions depends strongly on study characteristics. This pattern clarifies RQ2, which examines the specific SRL dimensions that benefit most from AI support, with cognitive and motivational regulation showing consistent improvement while behavioral regulation remains context-dependent. Practically, this indicates that AI tools are more reliable for supporting planning and monitoring than for influencing behaviors such as time management or sustained effort.

Figure 4

Forest plot of cognitive/metacognitive regulation.

Figure 5

Forest plot of motivational and affective components.

Figure 6

Forest plot of behavioral regulation.

Figure 7

Forest plot of SRL dimensions.

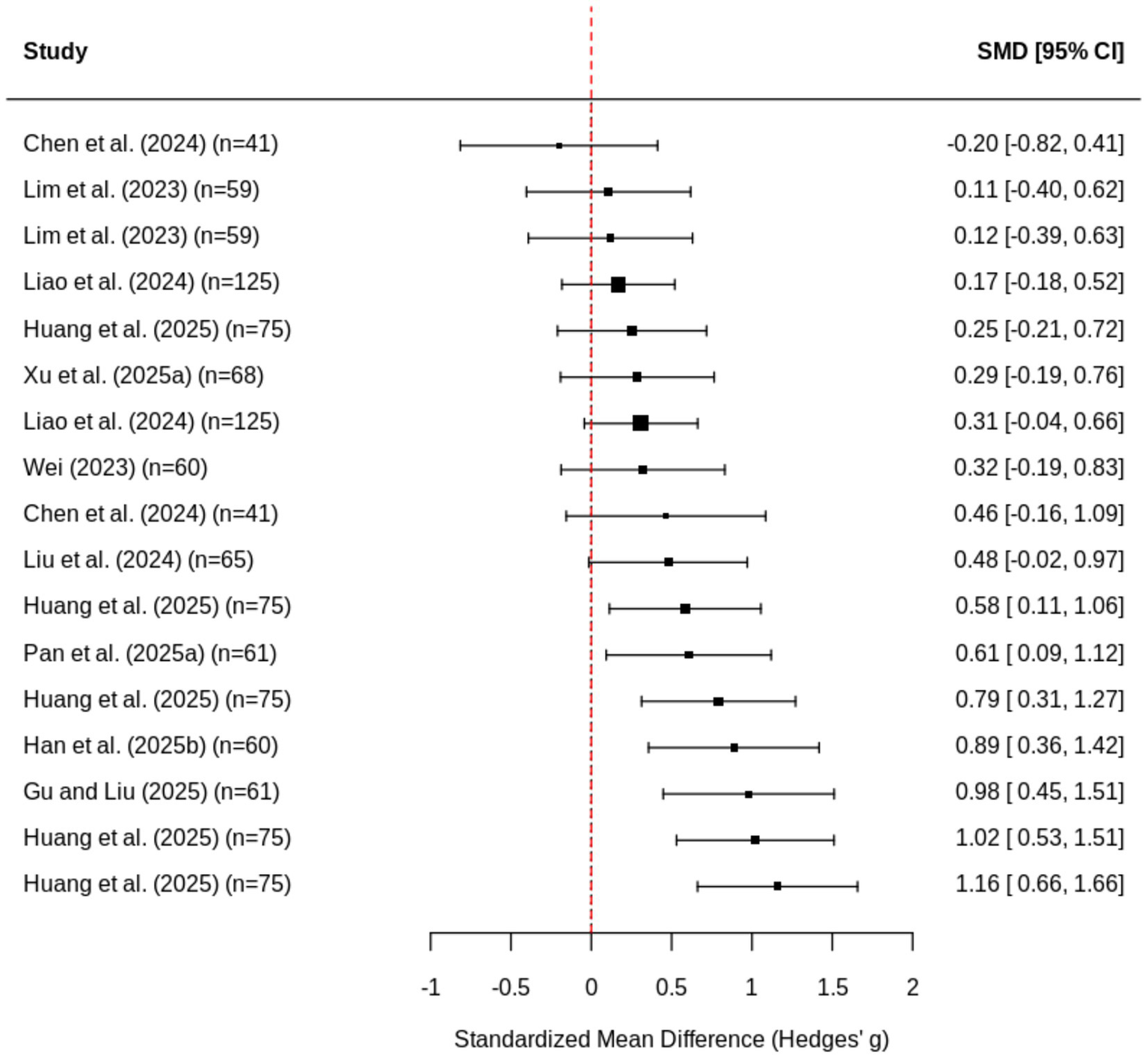

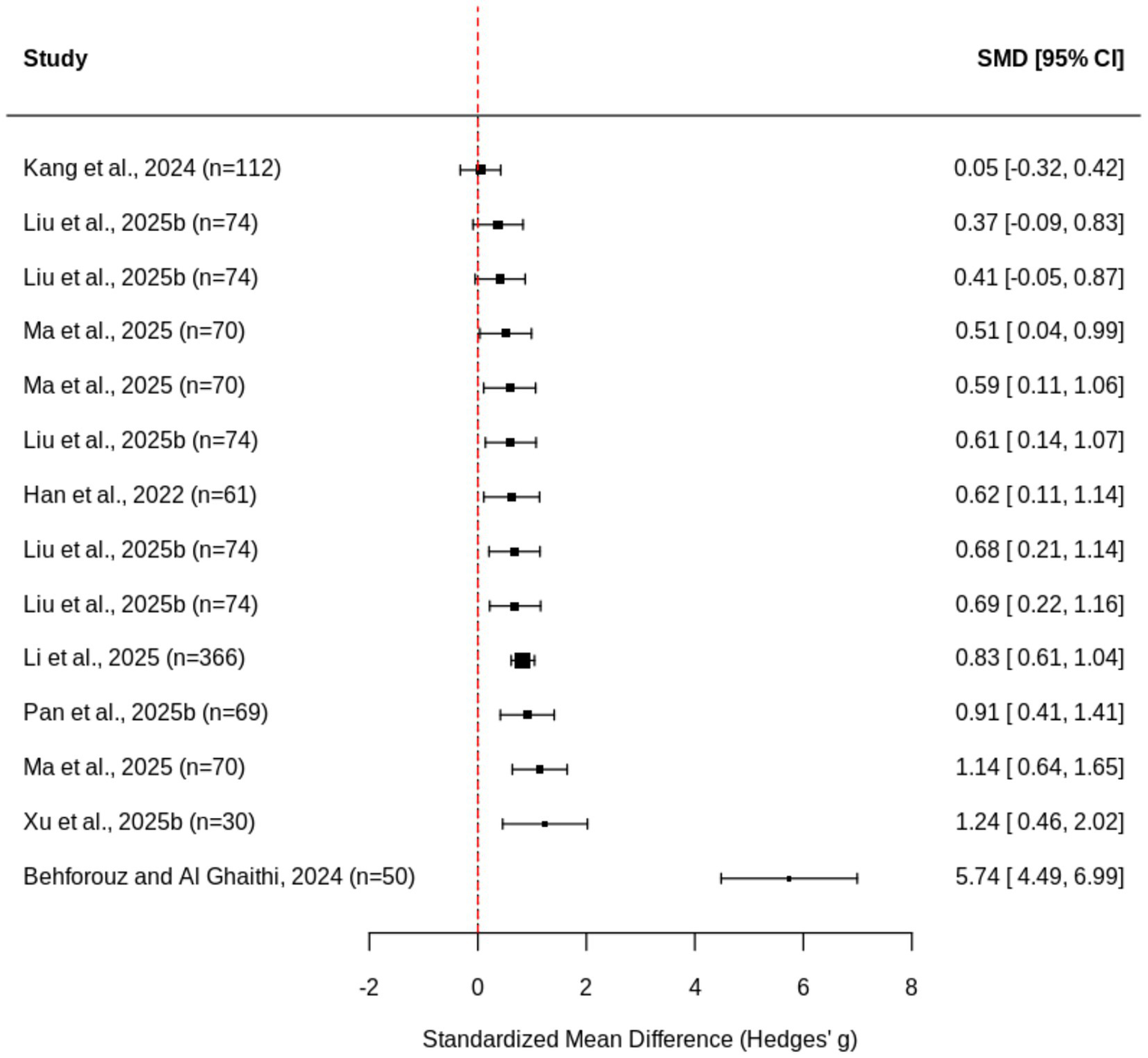

4.1.3 SRL phases

AI interventions had a moderate and statistically significant positive effect on the forethought phase of SRL (Figure 8). The relatively low heterogeneity (I2 = 44%) suggests that the effects were fairly consistent across studies. This implies that AI tools are reliably effective in enhancing learners’ preparatory and motivational processes.

Figure 8

Forest plot of forethought phase.

Although the performance phase (Figure 9) yielded a large mean effect size (g = 0.78), the confidence interval includes zero (−0.11 to 1.67) and the p-value (0.0782) indicates non-significance at the 0.05 level. The extremely high heterogeneity (I2 = 97%) suggests that results varied widely across studies. This variability may stem from differences in the types of AI systems, learning tasks, or performance indicators used (e.g., monitoring, strategy use, help-seeking).

Figure 9

Forest plot of performance phase.

For the self-reflection phase (Figure 10), AI interventions demonstrated a small but statistically significant positive effect. The moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 68%) indicates moderate variability across studies. These findings suggest that AI tools modestly support reflective learning processes such as self-evaluation, satisfaction, and adaptive regulation.

Figure 10

Forest plot of self-reflection phase.

These results directly address RQ3 by showing that AI interventions are most effective during the forethought phase and modestly beneficial in self-reflection, but less predictable during active performance. This suggests that AI tools currently support preparatory thinking and post-task evaluation more effectively than real-time behavioral regulation. These findings collectively indicate that AI-based systems are particularly effective in the forethought phase, where they enhance learners’ planning and motivational readiness. Performance-phase outcomes, although potentially strong, are highly context-dependent. Self-reflection outcomes show modest improvement, pointing to the need for AI tools that better facilitate post-task reflection and adaptive learning.

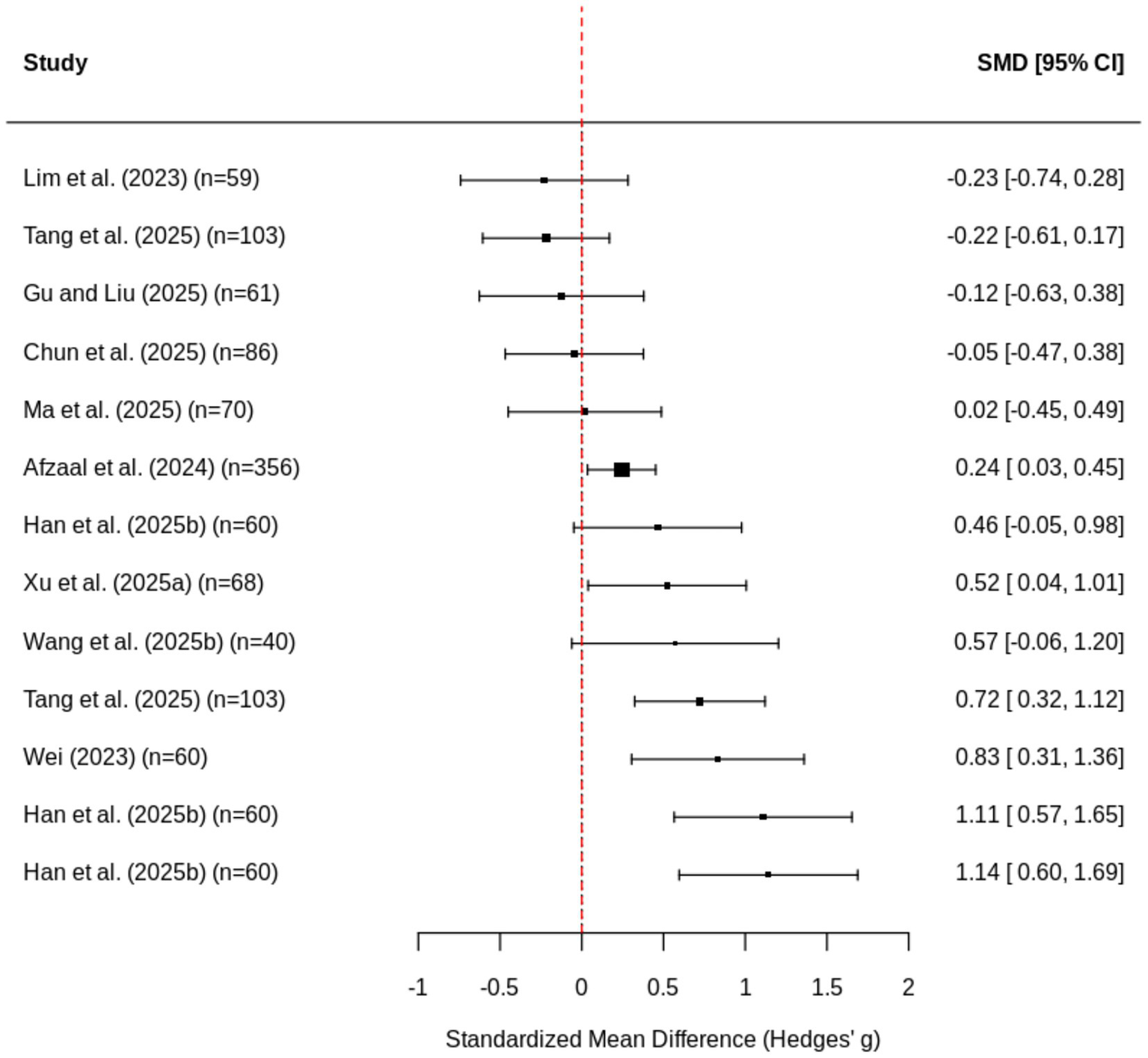

4.1.4 Learning outcomes

Interventions led to a small-to-moderate positive effect on learning outcomes and performance (Figure 11) (g = 0.350, p = 0.034) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 69.04%, τ2 = 0.097), indicating that AI-based or related interventions can improve learners’ academic performance and task achievement. The moderate heterogeneity suggests that effects varied across studies, potentially due to differences in intervention design, subject domains, learner characteristics, or assessment methods. These findings indicate that AI-based interventions moderately enhance learning outcomes, supporting the development of knowledge, skills, and performance. This result answers RQ4 by demonstrating that AI-supported gains in regulatory processes translate into measurable improvements in academic performance. In practice, this implies that AI tools not only shape learning strategies but also produce meaningful, although variable, achievement gains.

Figure 11

Forest plot of learning outcomes and performance.

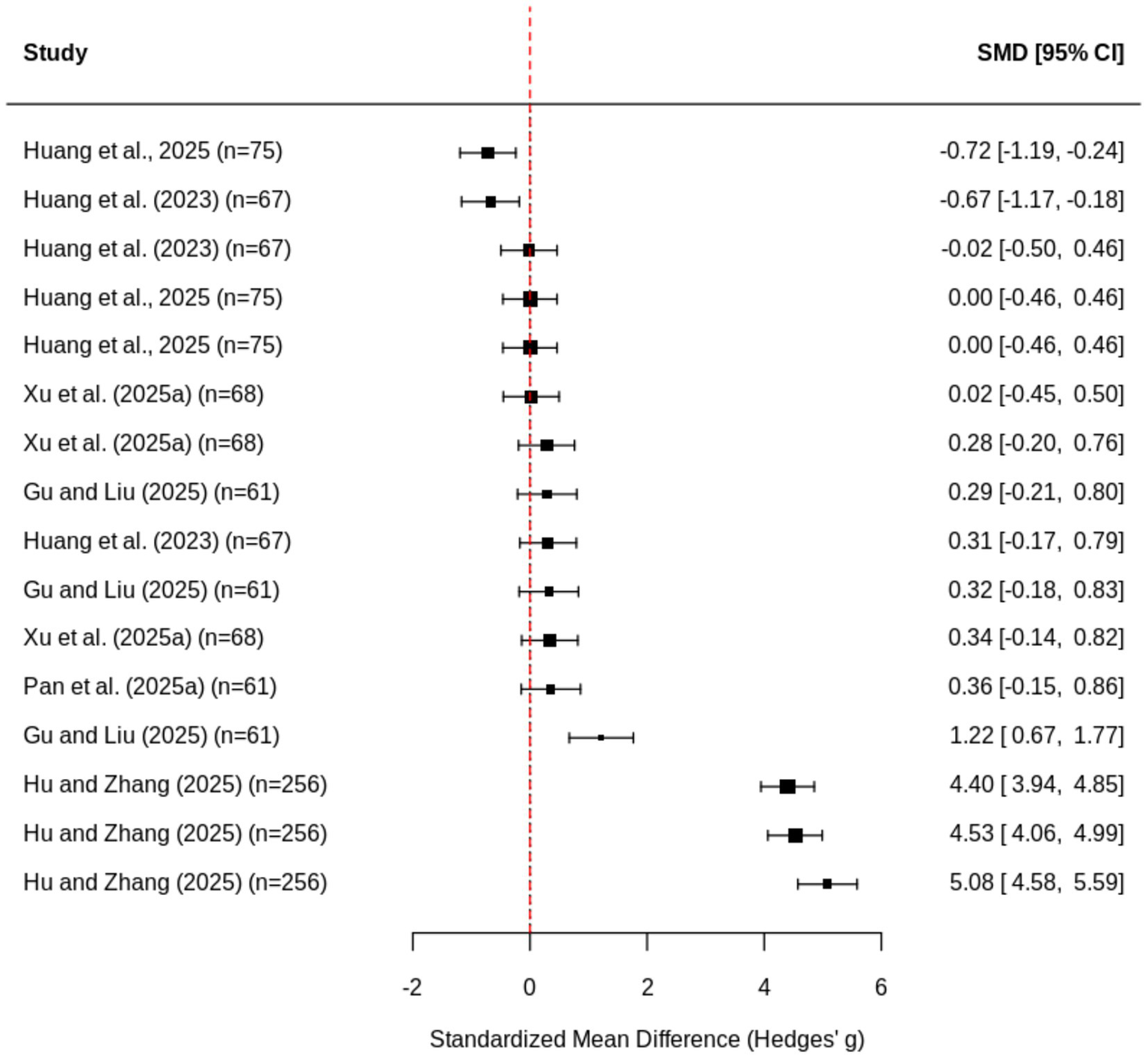

4.1.5 Self-directed learning

Interventions also produced a large positive effect on self-directed learning (Figure 12) (g = 1.111, p = 0.043) with very high heterogeneity (I2 = 91.14%, τ2 = 0.532), suggesting substantial gains in learners’ ability to plan, monitor, and regulate their own learning activities. The high heterogeneity indicates considerable variability across studies, which may result from differences in the types of AI tools, measurement approaches, or learner populations. These findings suggest that AI-based or related interventions are particularly effective in fostering self-directed learning, enhancing learners’ autonomy, engagement, and capacity for adaptive self-regulation. These findings directly address RQ5 by confirming that AI interventions significantly enhance learners’ autonomy, self-monitoring, and long-term learning habits. This suggests that AI systems can support both immediate regulation and the development of enduring self-directed learning behaviors.

Figure 12

Forest plot of SDL.

4.2 Moderator analysis

Meta-regression analysis was conducted to examine the moderating effects of participant characteristics (age and gender), study duration, subject domain, and AI intervention type across the various constructs related to self-regulated learning (Table 2). Each moderator was evaluated separately to determine its relationship with the effect sizes. Among the examined moderators, age emerged as a statistically significant moderator for overall SRL effects (Estimate = 0.4053, p = 0.0471). Older learners tended to experience stronger gains in self-regulatory capacities when supported by AI tools. The positive coefficient suggests that with increasing cognitive maturity and metacognitive development, learners may be better positioned to leverage AI feedback, adaptive prompts, and analytics. Although age did not significantly moderate specific SRL dimensions or phases, a marginal effect was observed for behavioral regulation (estimate = 1.3518, p = 0.059), implying that age-related factors may influence behavioral control and effort management under AI guidance. These results align with developmental theories of metacognition, suggesting that SRL gains from AI integration may become more pronounced as learners mature. In contrast, gender composition—measured as the proportion of male participants—did not significantly influence SRL outcomes. This indicates that AI interventions generally support SRL processes similarly across gender groups.

Table 2

| Moderators | Value | SRL (over all) | SRL dimensions | Cognitive and metacognitive regulation | Motivational and affective regulation | Behavioral regulation | Forethought phase | Performance phase | Self-reflection phase | Learning outcomes and performance | Self-directed learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Estimate | 0.4053 | 0.0211 | −0.0221 | 0.063 | 1.3518 | −0.0054 | 0.0809 | 0.0177 | 0.0174 | −0.0298 |

| p-value | 0.0471 | 0.6786 | 0.1705 | 0.1215 | 0.059 | 0.854 | 0.337 | 0.5988 | 0.6164 | 0.7662 | |

| Male participant (%) | Estimate | 0.0132 | 0.0076 | −0.0029 | −0.017 | 0.026 | −0.0077 | 0.0076 | −0.0147 | −0.0175 | 0.0305 |

| p-value | 0.8074 | 0.5917 | 0.5926 | 0.0624 | 0.6363 | 0.4008 | 0.7229 | 0.2638 | 0.2037 | 0.0741 | |

| Study duration | Estimate | 0.4143 | −0.0043 | −0.0051 | −0.0776 | 0.0183 | −0.0111 | 0.0014 | −0.0112 | −0.0199 | −0.0362 |

| p-value | 0.0157 | 0.7012 | 0.1278 | 0.0632 | 0.9433 | 0.0595 | 0.9474 | 0.3255 | 0.7283 | 0.7201 | |

| Subject domain | |||||||||||

| Language learning | Estimate | 2.5373 | 1.0411 | 0.5006 | 0.4634 | 1.6850 | 0.5270 | 1.3211 | 0.3057 | 0.4123 | 1.2595 |

| p-value | 0.031 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0845 | 0.0024 | 0.0016 | <0.0001 | 0.1593 | 0.2377 | 0.0064 | |

| STEM | Estimate | 1.1263 | 0.1295 | 0.2448 | 0.1296 | −0.1273 | 0.1296 | 0.1298 | 0.2485 | 0.2494 | 0.5503 |

| p-value | 0.456 | 0.6840 | 0.0441 | 0.6617 | 0.9002 | 0.6588 | 0.7577 | 0.3867 | 0.4515 | 0.3080 | |

| Medical | Estimate | 0.9980 | 0.9968 | 0.8873 | 0.8984 | 0.7970 | 0.9215 | ||||

| p-value | 0.1613 | 0.0003 | 0.0205 | 0.0005 | 0.0249 | 0.2897 | |||||

| Others | Estimate | 0.5796 | 0.2685 | 0.1848 | 0.5819 | −0.2392 | 0.4872 | 0.1884 | 0.1243 | 0.2340 | |

| p-value | 0.7016 | 0.2079 | 0.0154 | <0.0001 | 0.8135 | <0.0001 | 0.5684 | 0.5532 | 0.3951 | ||

| AI intervention type | |||||||||||

| Conversational and interactive AI systems | Estimate | 1.9063 | 1.1493 | 0.5320 | 0.5902 | 1.8325 | 0.5003 | 1.6445 | 0.4984 | 0.5040 | 1.0063 |

| p-value | 0.0896 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0069 | 0.0014 | 0.0034 | <0.0001 | 0.0054 | 0.0376 | 0.0170 | |

| Instructional and adaptive learning systems | Estimate | 2.4573 | 0.0909 | 0.1432 | −0.1273 | 0.1135 | 0.1020 | −0.2295 | 1.2384 | ||

| p-value | 0.3714 | 0.7485 | 0.1282 | 0.8980 | 0.6618 | 0.7928 | 0.6341 | 0.3389 | |||

| Supportive and analytical AI systems | Estimate | 0.9794 | 0.3664 | 0.3118 | 0.5623 | −0.0906 | 0.5489 | 0.2160 | 0.3009 | 0.2493 | 0.7870 |

| p-value | 0.4746 | 0.0617 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.9161 | <0.0001 | 0.4873 | 0.1498 | 0.2920 | 0.2100 | |

Moderator analyses.

Study duration significantly moderated overall SRL effects (Estimate = 0.4143, p = 0.0157), with longer interventions producing stronger improvements. This underscores the importance of sustained engagement with AI tools to enable learners to internalize regulatory strategies and transfer them into autonomous learning behaviors. Although most SRL dimensions did not show significant duration effects, marginal influences were observed for motivational regulation (p = 0.0632) and the forethought phase (p = 0.0595), suggesting that extended exposure may particularly strengthen motivational readiness and planning processes.

Subject domain, a categorical variable with four levels (language learning, STEM, medical, and other), also produced significant differences. Studies in the language learning domain demonstrated consistently strong moderating effects across SRL dimensions, including cognitive and metacognitive regulation, the performance phase, and learning outcomes. This suggests that communication-rich, feedback-intensive environments may be especially conducive to AI-supported SRL development. In STEM domains, significant moderation was observed only for cognitive and metacognitive regulation (p = 0.0441). Studies categorized as “other” domains (e.g., social sciences, humanities, business) produced significant moderating effects for cognitive and metacognitive regulation (p = 0.0154), motivational regulation (p < 0.0001), and the forethought phase (p < 0.0001). Medical education studies demonstrated significant moderation for SRL dimensions (p = 0.0003), behavioral regulation (p = 0.0205), and the performance phase (p = 0.0005), suggesting that practice-based learning environments may encourage deeper engagement with AI-supported regulatory strategies. Collectively, these findings indicate that disciplinary context meaningfully shapes SRL responsiveness, with language learning and medical domains yielding the strongest effects.

AI intervention type also emerged as a significant moderator. This categorical moderator consisted of three categories: (a) conversational and interactive systems (e.g., ChatGPT, chatbots), (b) instructional and adaptive systems (e.g., intelligent tutoring systems), and (c) supportive and analytical systems (e.g., analytics dashboards, generative AI-powered textbooks). Conversational and interactive AI systems produced consistently strong and significant effects across nearly all SRL outcomes (all p < 0.01 except overall SRL, p = 0.0896), highlighting the central role of dialogic interaction and feedback exchange. Instructional and adaptive systems did not show significant moderating effects, suggesting that these tools may not provide the level of agency or reflective engagement required for SRL development. Supportive and analytical systems yielded significant effects for cognitive and metacognitive regulation (p = 0.0001), motivational regulation (p < 0.0001), and the forethought phase (p < 0.0001), indicating that dashboards and feedback tools may effectively support planning and metacognitive oversight.

In summary, the moderator analysis shows that the effectiveness of AI interventions on self-regulated and self-directed learning depends on developmental, contextual, and design-related factors. Age and study duration positively predict SRL gains, while disciplinary context produces distinct patterns of responsiveness. Domain-level differences reveal that language learning, as well as medical domains, yield the most robust and widespread SRL improvements, while STEM and other fields exhibit more selective effects across subdimensions. Conversational and interactive AI systems offer the broadest benefits, whereas supportive and analytical tools strengthen specific SRL sub-processes. These results emphasize the importance of aligning AI design with pedagogical goals and learner characteristics to ensure that AI functions as an empowering scaffold that supports sustained, autonomous, and adaptive learning regulation.

4.3 Sensitivity analysis

Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the stability of the pooled effect sizes across all constructs. For overall SRL, effect sizes remained consistently large (g = 0.914 to 1.746), indicating that no single study disproportionately influenced the results, even though publication bias was detected. In the cognitive/metacognitive regulation and motivational regulation domains, pooled effects were similarly robust (g = 0.451 to 0.577), showing stable improvements in learners’ cognitive engagement, metacognitive strategy use, and motivation when individual studies were removed. Behavioral regulation showed wider variability (g = 0.157 to 1.145) due to high heterogeneity, yet the overall positive pattern persisted. Across other SRL dimensions, pooled effects remained positive and relatively stable (g = 0.718 to 0.797), indicating consistent intervention effects on specific regulatory processes. For the SRL phases, the forethought phase demonstrated stable pooled effect sizes (g = 0.219 to 0.445), with overlapping confidence intervals across all leave-one-out iterations, indicating that no individual study exerted disproportionate influence. The performance phase also showed stable effects (g = 0.364 to 0.864), with minimal fluctuation when any single study was omitted. For the self-reflection phase, sensitivity analyses revealed only minor variations (g = 0.2139–0.3284), and the overlapping confidence intervals confirmed that no study dominated the results. For learning outcomes, pooled effects were moderate and stable (g = 0.278 to 0.421), suggesting reliable enhancement of academic performance. Similarly, SDL exhibited consistently large pooled effects (g = 0.667 to 1.285), supporting the robustness of interventions that promote autonomous learning behaviors. Collectively, these leave-one-out analyses indicate that the meta-analytic findings are highly robust across all constructs, with positive intervention effects maintained despite heterogeneity among studies.

4.4 Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed using multiple approaches, including Egger’s tests (standard and RVE-adjusted), Begg’s rank correlation, and trim-and-fill analyses. For overall SRL, both Egger’s standard test (p = 0.0056) and Begg’s test (p = 0.0264) indicated significant publication bias, suggesting a possible overestimation of effect sizes. However, the RVE-based Egger’s test did not reach significance. Across the cognitive/metacognitive regulation, motivational regulation, behavioral regulation, SRL dimensions, learning outcomes and performance, and SDL constructs, Egger’s tests and RVE-adjusted intercepts consistently indicated no significant bias (p ≥ 0.05). In contrast, Begg’s tests identified potential bias for SRL dimensions (p = 0.002) and SDL (p = 0.0098). Trim-and-fill analyses generally estimated few or no missing studies, suggesting that observed effect sizes were minimally affected by unpublished results. For the three SRL phases, evidence of publication bias was minimal. Egger’s tests (standard and RVE) indicated no significant funnel plot asymmetry across the forethought (t = 0.887, p = 0.391; RVE p = 0.687), performance (p = 0.8262; RVE p = 0.7275), and self-reflection phases (p = 0.3588; RVE p = 0.8338). Begg’s tests and trim-and-fill analyses further confirmed minimal bias, with no missing studies detected and adjusted effects closely matching the original estimates. Despite variation in heterogeneity across phases (I2 = 53–96%), these findings collectively suggest that publication bias is unlikely to have materially affected the pooled effects for any SRL phase. Although some evidence of bias appeared in specific SRL-related domains, the majority of tests indicate that the meta-analytic findings are reasonably robust and not substantially influenced by selective reporting.

5 Discussion

The current study examined how AI interventions influence learners’ self-regulated and self-directed learning by conducting a meta-analysis that identifies the SRL dimensions and phases benefiting most from AI integration. The findings provide strong evidence that AI-based interventions substantially enhance both self-regulated learning (Research Question 1) and self-directed learning (Research Question 5). They also offer insight into how technology mediates cognitive, motivational, and behavioral processes (Research Question 2), and which phases of SRL—forethought, performance, and self-reflection—are most affected (Research Question 3). In addition, the analysis evaluates whether AI interventions mediate the relationship between SRL and learning outcomes (Research Question 4).

Across 32 empirical studies and 92 effect sizes involving 3,029 participants, AI interventions produced large and statistically significant improvements in overall SRL (g = 1.613) and SDL (g = 1.111). These results indicate that learners not only become more capable of planning, monitoring, and regulating their learning activities but also develop greater autonomy in managing their learning trajectories. They reinforce the conceptualization of AI tools as dynamic external scaffolds that extend and amplify learners’ regulatory capacities, facilitating immediate task success while supporting long-term, self-sustained learning (Ruan and Lu, 2025; Barrot, 2024). Importantly, the findings suggest that AI does not merely automate learning processes but can actively shape cognitive and motivational habits—an observation consistent with He (2025)—by providing targeted support aligned with learners’ developmental and contextual needs.

To gain a deeper understanding of how these effects manifest, the analysis next examined specific SRL dimensions. At the dimensional level, the meta-analysis showed that AI interventions consistently enhance cognitive and metacognitive regulation (g = 0.377) as well as motivational and affective regulation (g = 0.505), with relatively low to moderate heterogeneity. These results suggest that AI affordances—ranging from adaptive feedback and generative prompts to analytics dashboards—effectively support strategic planning, progress monitoring, and self-evaluation, while also strengthening motivation, perceived task value, and self-efficacy. In contrast, behavioral regulation demonstrated non-significant and highly heterogeneous effects (g = 0.914, I2 = 98.32%), indicating that external supports struggle to consistently influence behaviors such as time management, effort regulation, and environmental structuring. This inconsistency likely reflects the complex interplay between learner context, personal habits, and environmental factors. Behavioral regulation is widely recognized as one of the most resistant SRL components to change, even under intensive interventions (Panadero, 2017), and our results show that AI does not overcome this structural difficulty. Most AI systems operate within bounded digital tasks and lack visibility into learners’ physical study environments, routines, or competing demands. As a result, their ability to shape persistence, time allocation, or productive workspace management remains limited. Emerging research on GenAI tools further cautions that automation may inadvertently reduce the need for deliberate effort regulation, leading some learners to offload responsibility rather than strengthen it (Nair et al., 2025). These findings indicate that AI is far more effective at supporting “in-the-head” SRL processes than habit-like behavioral routines that require environmental restructuring and sustained self-discipline.

Beyond the dimensional perspective, the meta-analysis also examined how AI influences different phases of SRL processes. Analyzing effects across SRL phases provided deeper insight into when AI support is most effective. The forethought phase showed moderate and consistent gains (g = 0.4739), underscoring the reliability of AI in supporting goal-setting, strategic planning, and motivational readiness. This suggests that AI tools are particularly well suited to scaffold preparatory processes in which learners make decisions about resource allocation, effort investment, and task prioritization. These findings align with emerging studies showing that AI enhances learners’ capacity to plan, monitor, and reflect—core processes emphasized in both student-focused SRL research (Zhu, 2025) and teacher-oriented AI–SRL assessments (Zhang et al., 2025). Performance-phase outcomes, although associated with a large mean effect (g = 0.78), were not statistically significant and exhibited extremely high heterogeneity (I2 = 97%). This pattern suggests that although AI effectively supports preparatory and reflective processes, it is far less capable of assisting learners during the cognitively demanding performance phase. Real-time task execution requires rapid sensemaking, adaptive prompting, and accurate interpretation of learner uncertainty—capabilities that many current AI systems do not yet reliably provide. Prior SRL and HCI research also indicates that interacting with AI during problem-solving can increase cognitive load or disrupt task flow in certain contexts (Prasad and Sane, 2024).

In the self-reflection phase, small but significant gains (g = 0.2774) suggest that AI can modestly enhance evaluative processes, helping learners interpret outcomes, regulate affect, and adapt strategies for future tasks. The modest magnitude of these gains implies that many AI tools provide feedback that is descriptive rather than diagnostic, limiting learners’ ability to translate insights into deeper strategy revision (Otaki and Lindwall, 2024). High-quality reflection requires prompts that encourage learners to interrogate errors, explain reasoning, and plan alternative approaches, yet many self-developed tools examined in these studies offered limited guidance of this kind. These findings indicate that AI interventions are highly effective during the forethought phase, moderately effective during post-task reflection, and variably impactful during real-time performance. This pattern points to opportunities for improving AI design to better support dynamic, in-task regulation.

In this meta-analysis, heterogeneity was assessed using Q, I2, and τ2 statistics to capture the magnitude and direction of between-study variability. High I2 values in behavioral regulation (98.32%) and performance-phase outcomes (97%) indicate substantial inconsistency, suggesting that effect sizes are shaped by differences in learner profiles, disciplinary contexts, intervention durations, and the design characteristics of AI tools. Conversely, the low-to-moderate heterogeneity observed for cognitive–metacognitive and motivational–affective regulation suggests a more uniform response to AI scaffolds, possibly reflecting shared cognitive mechanisms across instructional settings. Moderator analyses further clarified these trends by identifying age, study duration, subject domain, and AI system type as meaningful sources of variability, indicating that heterogeneity is not random but aligned with pedagogical and developmental factors.

A more analytical interpretation of heterogeneity provides additional clarity regarding the confidence and generalizability of these pooled effects. The very high I2 values observed for behavioral regulation and performance-phase outcomes suggest that these domains are strongly shaped by methodological and contextual variation—such as differences in SRL measurement (self-report vs. behavioral trace indicators), subject domain, intervention duration, and the design characteristics of AI systems (e.g., dialogic vs. adaptive vs. analytical tools). In contrast, cognitive/metacognitive and motivational regulation demonstrated low-to-moderate heterogeneity, indicating that these regulatory processes respond more consistently to AI-based scaffolds across learning contexts. These patterns imply that although the direction of effects is consistently positive, the magnitude of improvement in certain SRL components is context-dependent rather than universally generalizable. However, the stability of pooled estimates in sensitivity analyses reinforces confidence that the trends remain robust despite this variability. Thus, heterogeneity in this meta-analysis reflects meaningful pedagogical and learner-related differences rather than statistical noise and helps identify where AI interventions produce dependable gains versus where effects rely on contextual alignment.

The observed improvements in regulation processes naturally prompt consideration of whether such benefits extend to learners’ actual performance outcomes. The results revealed a small-to-moderate positive effect of AI-based interventions on learning outcomes and performance (g = 0.350), indicating that such interventions contribute meaningfully to learners’ academic achievement and task performance. The moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 69.04%) suggests that while the overall impact is beneficial, the magnitude of improvement varies across studies. These findings imply that AI technologies are most effective when they are pedagogically aligned with learning goals and tailored to individual learner needs. The results also provide empirical support for the notion that AI-supported learning environments can moderately enhance academic performance by fostering personalized and data-informed learning experiences (Vieriu and Petrea, 2025; Tang and Liao, 2025).

Complementing these findings on SRL and performance, the analysis also examined SDL, which represents a more autonomous extension of learners’ regulatory capabilities. The large positive effect observed for self-directed learning (g = 1.111) indicates the potential of AI interventions to substantially strengthen learners’ autonomy and self-regulation capacities. This enhancement reflects the ability of AI tools, such as intelligent dashboards, learning analytics, and adaptive recommendation systems, to scaffold learners’ planning, monitoring, and reflection processes. The very high heterogeneity (I2 = 91.14%) indicates wide variability across studies. Despite this variability, the consistently positive direction of effects suggests that AI-based interventions meaningfully promote self-directed learning behaviors. These technologies seem to empower learners to take greater control of their learning trajectories, enhance metacognitive awareness, and cultivate lifelong learning dispositions. Therefore, AI-supported learning environments hold significant promise for developing self-directed learners capable of adaptive and autonomous knowledge construction in dynamic educational contexts (Kang and Sung, 2024). High heterogeneity suggests that AI can both foster and inadvertently constrain autonomy depending on system transparency and design. If recommendations are overly prescriptive or opaque, learners may follow AI-generated paths rather than initiate or evaluate their own choices, creating dependence rather than genuine self-direction (Bonilla et al., 2025). Thus, while SDL gains are promising, they must be interpreted alongside the risk that AI may strengthen autonomy in some contexts while substituting it in others.

The conceptual framework presented in Figure 13, derived from the findings of the current study, offers an interpretive understanding of how AI-based interventions can foster learners’ self-regulated and self-directed learning processes. The findings suggest that AI tools—such as chatbots, dashboards, adaptive systems, and large language models (LLMs)—serve as mediating mechanisms that facilitate multiple dimensions of SRL, including cognitive and metacognitive regulation (planning, monitoring, and evaluation) (Gu and Liu, 2025), motivational and affective regulation (self-efficacy, task value, and persistence) (Chen et al., 2025), and behavioral regulation (time management, effort, and help-seeking) (Xu X. et al., 2025). By supporting these regulatory processes, AI appears to enhance the three core phases of SRL—forethought, performance, and self-reflection—thereby strengthening learners’ ability to plan, monitor, and adapt their learning strategies effectively. Importantly, these findings highlight AI’s potential role as an external scaffold that gradually promotes learner autonomy and adaptive self-regulation. Over time, this scaffolding effect may extend beyond SRL toward the development of SDL, characterized by greater independence, initiative, and sustained engagement in self-guided learning. Thus, the framework indicates how AI-enhanced regulation can serve as a pathway toward more autonomous and enduring learning behaviors.

Figure 13

AI–regulation–autonomy pathway.

To further contextualize these findings, moderator, sensitivity and publication bias analyses were conducted to examine potential sources of variability and the robustness of the results. Moderator analyses provide additional interpretive depth. The meta-regression results highlight that the effectiveness of AI-based interventions on SRL is shaped by learner, contextual, and design-related factors. Age significantly moderated overall SRL effects, indicating that older learners benefited more from AI support, likely due to greater metacognitive maturity and ability to utilize AI feedback for regulation. Study duration also showed a positive moderating effect, suggesting that sustained engagement with AI tools allows sufficient time for learners to internalize regulatory strategies and develop autonomy. In contrast, gender composition did not significantly influence outcomes, indicating that AI systems support SRL equitably across groups, a conclusion that diverges from the findings of Xia et al. (2023). Contextual differences were evident, with language learning subject domain showing stronger SRL gains compared to other domains, possibly due to their feedback-rich and reflective learning environments. Finally, AI intervention type emerged as a key determinant: conversational and interactive systems were more effective in promoting SRL than instructional, adaptive, or analytical systems, which may limit learner agency through over-automation or passive feedback. These findings, thus, suggest that AI’s impact on SRL is maximized when tools are interactive, implemented over extended periods, and aligned with the pedagogical and cognitive characteristics of the learning domain, which aligns with the findings of Ouyang (2025) that linking platform features to SRL can enhance educational quality.

The stability of the meta-analytic results was further confirmed through sensitivity analyses, which demonstrated that no single study disproportionately influenced effect sizes across SRL, SDL, or learning outcomes. While some evidence of publication bias was observed in specific SRL domains, trim-and-fill analyses suggested minimal impact on conclusions. Collectively, these analyses reinforce the reliability, validity, and generalizability of the observed effects, providing strong empirical support for integrating AI tools into both formal and self-directed learning contexts.

6 Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that AI-based interventions meaningfully strengthen learners’ self-regulated and self-directed learning, but in differentiated rather than uniform ways. Across 32 empirical studies, AI consistently improved cognitive and metacognitive processes as well as motivational and affective regulation, confirming that AI functions most effectively as a feedback-rich scaffold supporting planning, monitoring, and reflective evaluation. In contrast, behavioral regulation and in-task performance exhibited wide variability, reinforcing that these domains are strongly shaped by learners’ habits, contextual constraints, and the design sensitivity of the AI tools involved. These differentiated effects indicate that AI’s value lies not in broadly automating regulatory processes but in amplifying the SRL and SDL components that benefit most from structured guidance, adaptive prompting, and reflective analytics.

The phase-level analysis further clarifies how AI shapes self-regulation. AI showed the most reliable effects during the forethought phase—supporting goal-setting, strategic planning, and motivational activation—while post-task reflection benefited modestly. The performance phase, however, yielded inconsistent outcomes, suggesting that real-time task engagement requires AI systems capable of dynamic, context-aware support that extends beyond static scaffolding. These findings refine SRL theory by identifying the stages at which AI scaffolds are developmentally and cognitively most impactful, offering a more granular pathway for aligning AI design with the temporal structure of learning.

While the pooled effects for SRL and SDL are strongly positive, the high heterogeneity observed in behavioral regulation and performance-phase outcomes indicates that these effects are sensitive to contextual and methodological differences and should be interpreted with caution. Conversely, the low-to-moderate heterogeneity in cognitive/metacognitive regulation, motivational regulation, and forethought processes strengthens confidence in the consistency of these findings across diverse learning environments. Taken together, these distinctions highlight the importance of aligning AI design with the regulatory processes most responsive to external scaffolds. These patterns are further illuminated by the moderator analyses.

Moderator analyses reveal that learner maturity, duration of exposure, disciplinary context, and system type substantially shape effectiveness. Older learners and those engaging with AI over longer periods demonstrated greater regulatory gains, indicating that internalization of SRL strategies develops gradually. Language-learning contexts showed the strongest improvements, reflecting the inherently reflective and feedback-driven nature of language tasks. Importantly, conversational and interactive AI systems consistently outperformed adaptive or analytical ones, underscoring the centrality of dialogic engagement and learner agency in effective AI-supported learning.

Taken together, these findings resolve inconsistencies in earlier AI–SRL research and clarify when, why, and for whom AI scaffolds produce the most meaningful benefits. The evidence suggests that AI can play a critical role in cultivating strategic, motivated, and autonomous learners—but only when systems are intentionally designed around the phases and dimensions of SRL most receptive to external support. By articulating the mechanisms through which AI strengthens internal regulation and identifying the conditions under which these effects generalize, this study provides a theoretically grounded and empirically supported roadmap for the next generation of AI-enhanced learning environments.

7 Implications and future directions

The findings of this study affirm the utilization of AI-based tools in pedagogical design to scaffold specific phases and dimensions of self-regulated learning rather than providing uniform support. The strong effects observed in the forethought phase suggest that AI should prioritize goal-setting aids, planning assistance, and motivational prompts early in the learning cycle. However, since performance and behavioral regulation outcomes were highly variable, designers should incorporate adaptive, context-sensitive feedback that responds to learners’ engagement patterns without fostering overreliance. Embedding reflection-oriented analytics or conversational prompts post-task can further strengthen self-evaluation and transfer of regulatory skills.

Moderation analyses showing stronger effects among older learners indicate developmental differences in AI responsiveness. This suggests that adaptive scaffolds should calibrate support intensity based on learners’ maturity, prior self-regulation skills, and domain experience. Additionally, since prolonged study durations were associated with stronger self-regulatory outcomes, educational programs should promote sustained engagement with AI tools over short-term or one-off implementations. Iterative interaction allows learners to internalize regulatory strategies, reinforcing the gradual transition from guided to autonomous control.

By combining learner modeling with adaptive fading strategies, AI systems can personalize the balance between guidance and autonomy, ensuring equitable benefits across age, gender, and educational backgrounds. Given the moderating influence of subject domain, AI integration should be contextually grounded, language learning field may leverage conversational agents and reflective feedback, while STEM and applied domains might require tools emphasizing strategic monitoring and procedural adaptability. Tailoring AI affordances to disciplinary learning demands can enhance relevance and efficacy.

For institutions, the results highlight the value of integrating AI as a complementary scaffold rather than a substitute for human regulation. Universities and training organizations should adopt AI systems that encourage autonomy by gradually fading support and making metacognitive processes explicit. Policies governing AI adoption in education should ensure transparency, learner agency, and pedagogical alignment, balancing efficiency with ethical considerations of data privacy, fairness, and responsible use. Institutions should also consider that conversational and interactive AI systems, which support active dialog and feedback exchange, appear more effective in promoting self-regulation than purely adaptive or analytical systems. Strategic adoption of such interactive designs may foster deeper learner engagement and reflective thinking.

Educators should be trained to interpret AI analytics and feedback to personalize guidance and foster learner independence. The observed gains in SRL and SDL imply that learners benefit most when AI systems are paired with explicit instruction in metacognitive and self-monitoring strategies. Instructors can leverage AI dashboards and generative feedback tools to model reflection, goal revision, and strategy use, turning AI interactions into opportunities for metacognitive coaching rather than automated evaluation. Longer-term educator engagement with AI can further help sustain learners’ regulatory habits, aligning with findings that duration of exposure amplifies SRL benefits.

The study provides empirical support for models of self-regulated and self-directed learning that treat AI as an external regulatory agent capable of influencing internal cognitive, motivational, and affective processes. Future research should extend this work through longitudinal and experimental designs that trace how AI scaffolds contribute to the maintenance and transfer of regulatory skills after support is withdrawn. Further, more precise alignment of behavioral trace data with SRL theory could clarify mechanisms linking AI interaction patterns to learning outcomes. Future investigations should also examine cross-domain adaptation of AI scaffolds and compare interactive versus adaptive system designs to determine which configurations sustain long-term self-regulation most effectively across learner populations. Future research can achieve broader coverage by complementing Scopus and Google Scholar with subject-specific databases to capture any additional studies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KA: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

This work derives direction and ideas from the Chancellor of Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Sri Mata Amritanandamayi Devi. The author would like to thank Ms. Athulya N. for her contribution to the study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Afzaal M. Zia A. Nouri J. Fors U. (2024). Informative feedback and explainable AI-based recommendations to support students’ self-regulation. Technol. Knowl. Learn.29, 331–354. doi: 10.1007/s10758-023-09650-0

2

Aljafari R. (2021). “Self-directed learning strategies in adult educational contexts: helping students to perceive themselves as having the skills for successful learning” in Research anthology on adult education and the development of lifelong learners (IGI Global), 611–621.

3

Barrot J. S. (2024). ChatGPT as a language learning tool: an emerging technology report. Technol. Knowl. Learn.29, 1151–1156. doi: 10.1007/s10758-023-09711-4

4

Behforouz B. Al Ghaithi A. (2024). The impact of using interactive chatbots on self-directed learning. Stud. Self-Access Learn. J.15:302. doi: 10.37237/150302

5

Benkhelifa F. Lakhani F. Jendoubi T. Paltalidis N. Wijeratne V. (2025). “Exploring the use of Genai code assistants for engineering students in transnational education programmes: a pilot study” in 2025 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (IEEE), 1–7.

6

Bonilla C. R. N. Viñan Carrasco L. M. Gaibor Pupiales J. C. Murillo Noriega D. E. (2025). The future of education: a systematic literature review of self-directed learning with ai. Future Internet17:366.

7

Chen J. (2022). The effectiveness of self-regulated learning (SRL) interventions on L2 learning achievement, strategy employment and self-efficacy: a meta-analytic study. Front. Psychol.13:1021101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1021101,

8

Chen A. Wei Y. Le H. Zhang Y. (2025). Learning by teaching with ChatGPT: the effect of teachable ChatGPT agent on programming education. Br. J. Educ. Technol., 1–22.

9

Chun J. Kim J. Kim H. Lee G. Cho S. Kim C. et al . (2025). A comparative analysis of on-device AI-driven, self-regulated learning and traditional pedagogy in university health sciences education. Appl. Sci.15:1815. doi: 10.3390/app15041815

10

Cloude E. B. Azevedo R. Winne P. H. Biswas G. Jang E. E. (2022). System design for using multimodal trace data in modeling self-regulated learning. Front. Educ.7:928632.

11

Cohn C. Snyder C. Fonteles J. H. Ts A. Montenegro J. Biswas G. (2025). A multimodal approach to support teacher, researcher and AI collaboration in STEM+ C learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol.56, 595–620. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13518

12

Diwakar S. Kolil V. K. Francis S. P. Achuthan K. (2023). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation among students for laboratory courses-Assessing the impact of virtual laboratories. Computers & Education, 198:104758. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2024.103804

13

Du Q. (2025). How artificially intelligent conversational agents influence EFL learners' self-regulated learning and retention. Educ. Inf. Technol.30, 21635–21701. doi: 10.1007/s10639-025-13602-9

14

Gonçalves C. A. Gonçalves C. T. (2024). “Assessment on the effectiveness of github copilot as a code assistance tool: an empirical study” in EPIA conference on artificial intelligence. (Eds.) Santos M. F., J. Machado J., Novais, P., Cortez, P., Moreira, P. M. (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 27–38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-73503-5_3

15

Gu J. Liu Q. (2025). Enhancing Chinese EFL university students’ self-regulated learning through AI chatbot intervention: insights from achievement goal theory. Learn. Motiv.92:102191. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2025.102191

16

Han I. Ji H. Jin S. Choi K. (2025). Mobile-based artificial intelligence chatbot for self-regulated learning in a hybrid flipped classroom. J. Comput. High. Educ., 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s12528-025-09434-8

17

Han J. W. Park J. Lee H. (2022). Analysis of the effect of an artificial intelligence chatbot educational program on non-face-to-face classes: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Med. Educ.22:830. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03898-3,

18

Han J. W. Park J. Lee H. (2025). Development and effects of a chatbot education program for self-directed learning in nursing students. BMC Med. Educ.25:825. doi: 10.1186/s12909-025-07316-2,

19

Han S. Zhang Z. Liu H. Kong W. Xue Z. Cao T. et al . (2024). From engagement to performance: the role of effort regulation in higher education online learning. Interact. Learn. Environ.32, 6607–6627. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2023.2273486

20

He G. (2025). Predicting learner autonomy through AI-supported self-regulated learning: a social cognitive theory approach. Learn. Motiv.92:102195. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2025.102195

21

Hu X. Zhang H. (2025). Exploring AI-assisted self-regulated learning profiles and the predictive role of academic appraisals: a control-value perspective on Chinese EFL university students. Eur. J. Educ.60:e70249. doi: 10.1111/ejed.70249

22

Huang A. Y. Chang J. W. Yang A. C. Ogata H. Li S. T. Yen R. X. et al . (2023). Personalized intervention based on the early prediction of at-risk students to improve their learning performance. Educ. Technol. Soc.26, 69–89.

23

Huang A. Y. Lin C. Y. Su S. Y. Yang S. J. (2025). The impact of GenAI-enabled coding hints on students' programming performance and cognitive load in an SRL-based Python course. Br. J. Educ. Technol.56:13589. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13589

24