- 1Economics and Management School, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

The green credit policy is a crucial tool that the Chinese government adopted to tackle environmental problems by combining environmental regulation and credit policy. This study takes the Green Credit Guidelines (GCG) issued in 2012 as a quasi-natural experiment to examine its impact on the export quality of firms. Using data covering Chinese A-share listed firms and the difference-in-difference (DID) method, the empirical research shows that the GCG significantly enhanced the export quality of heavily polluting firms. The mediation analyses indicate that green innovation plays an intermediate role in enhancing the export quality of firms. The heterogeneity analysis of firm characteristics demonstrates that the improvement effect brought by the GCG is significantly reflected in state-owned firms and firms in financially underdeveloped areas. The research results provide implications for firms on how to deal with the green credit policy. In addition, it also serves as an essential reference for developing economies on the successful implementation of market-based environmental regulations.

1 Introduction

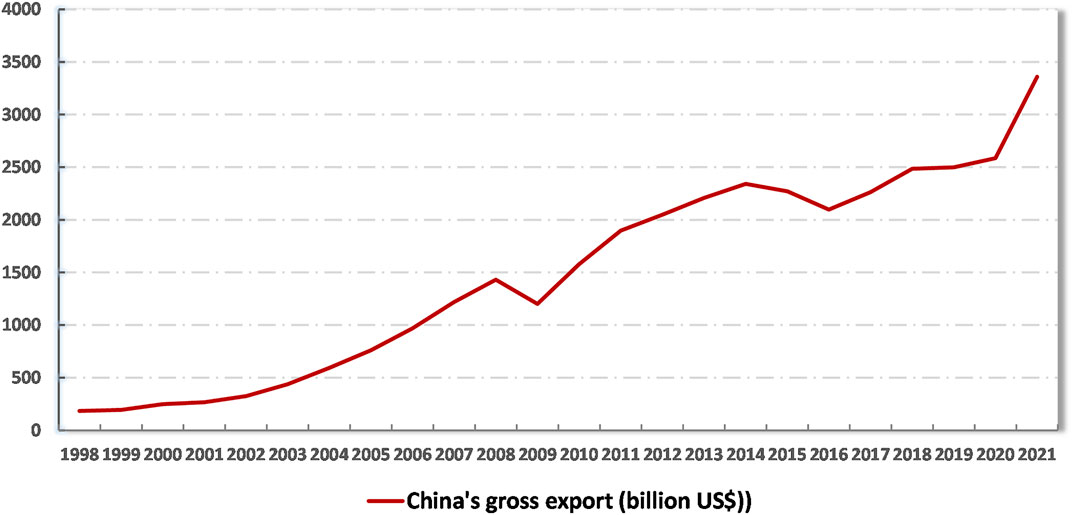

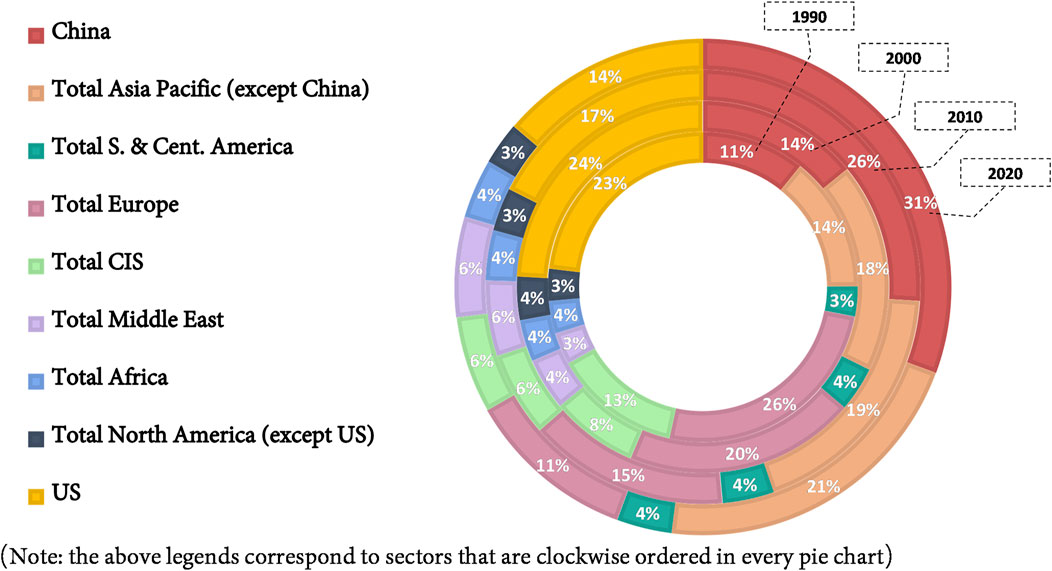

Since it acceded to the WTO, China’s export has increased rapidly (Feng et al., 2017). According to the latest figures released by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics (Figure 1), even though the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant adverse effect on export (Zhao et al., 2021), China’s gross exports still showed an upward trend. After reaching remarkable achievements in the scale of its export trade, however, China is now facing a more crucial issue of sustainable development. On the one hand, the quality of export products and the domestic value-added in gross exports are still relatively low in China (Koopman et al., 2014), which will restrict further improvements in China’s competitiveness in the fierce international competition. On the other hand, export is the leading cause of the rise in CO2 emissions in China (Weber et al., 2008) and has caused severe environmental problems. According to the “Statistical Review of World Energy 2021” released by British Petroleum (BP) (Figure 2), China’s carbon dioxide emissions in 2020 accounted for about 31% of global carbon emissions, and this is nearly three times larger than it was in 1990. In addition, Figure 2 also indicates that China’s share has been growing since 2010, while that of the United States has started to decline. As a result, a green and high-quality development model has become an inevitable choice (Ye et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2022a) for China.

FIGURE 1. 1998–2021 China’s gross export. Data source: http://www.stats.gov.cn/.

FIGURE 2. Global share of carbon dioxide emissions by region in 1990, 2000, 2010, and 2020. Data source: http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview.

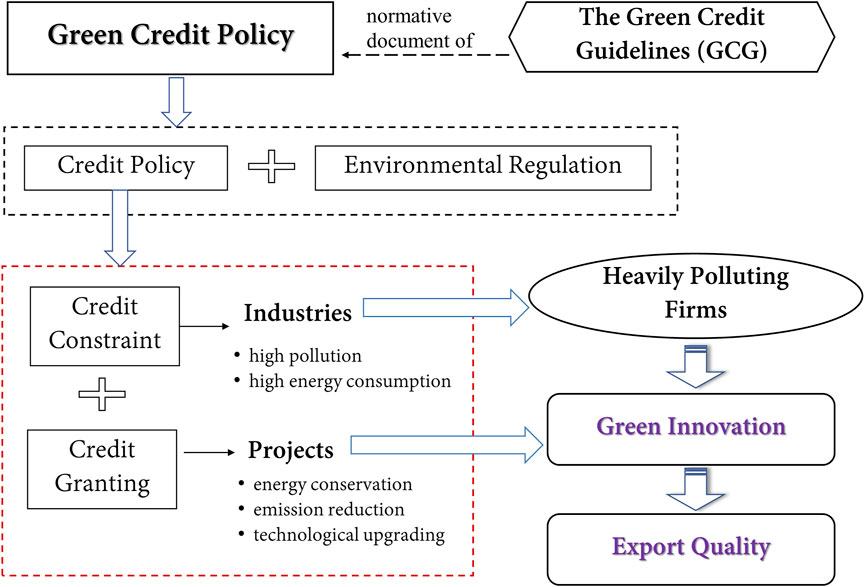

The green credit policy is an important measure taken by the Chinese government to achieve green and high-quality development. Given the importance of bank credit for firms, this policy aims to encourage enterprises to take up environmental responsibility by linking access to credit loans and firms’ environmental performance (Bing et al., 2011). The Green Credit Guidelines (hereafter referred to as the GCG) issued by the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) in 2012 is the first normative document of the green credit policy. It points out that when making credit decisions, banks should not only consider financial indicators such as corporate solvency but also pay close attention to the firm’s environmental risks. Specifically, it requires banks to strictly control credit issuance in high pollution and energy consumption industries. In addition, it also promises to increase credit support for green projects related to energy conservation, emission reduction, and technological upgrading. By adding credit constraints to heavily polluting firms and alleviating the financing burden for green projects, the GCG serves as an essential supplement to traditional environmental regulations and a crucial means to encourage firms to invest in innovation. When non-tariff barriers such as the green barrier advocating strict environmental standards have been widely accepted in international trade, the green credit policy may have a more widespread effect on firms than expected.

This study takes the promulgation of the GCG as a quasi-natural experiment. It uses the DID method to detect whether the green credit policy enhances the export quality of firms. The marginal contribution of this study is as follows. First, to the best of the author’s knowledge, this article provides the first empirical evidence on the relationship between the green credit policy and the export quality of firms. Other studies in this area are more concerned about the environmental implication of the green credit policy (Bing et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2019; Xiao et al., 2022). Since credit constraints placed on firms influence their export strategy and lead them to produce lower-quality products, as noted in the literature on financial distress (Phillips and Sertsios, 2013), the impact of the green credit policy on the export quality of heavily polluting firms in China is worthy of more deep exploration. This study enriches the literature on the evaluation of market-based environmental regulations. Second, this study uses firm-level data and empirically verifies that heavily polluting firms are more willing to carry out green innovation and thus improve their export quality in the face of the green credit policy. This finding provides a better understanding of the micro transmission mechanism of the green credit policy.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review about the implementation effect of the green credit policy and factors affecting China’s export quality. Section 3 discusses the theoretical mechanism. Section 4 describes the data and introduces the strategy of the empirical analysis. Section 5 reports the empirical results. The final section discusses the conclusions and implications.

2 Literature review

The research on China’s green credit policy mainly focuses on investigating its implementation effect. Bing et al. (2011) have found that this policy was not fully implemented due to the vague policy details and unclear implementing standards. Liu et al. (2019) used the promulgation of the GCG to empirically evaluate the impact of the green credit policy on the debt financing capacity of heavily polluting firms. They discovered that this policy has a significant inhibitory effect on the latter. Wang et al. (2019) utilized the listed Chinese heavily polluting firms as an example to empirically study the impact of the green credit policy on the level of environmental information disclosure and discovered that this policy improved the level of environmental information disclosure of firms. Other scholars employed mediation effect analysis and found that green credit policy can promote environmental protection by regulating the behavior of heavily polluting firms (Sun et al., 2019; Yao et al., 2021; Zhang, 2021), improving the quality of the green innovation of firms (Wang et al., 2022), or increasing their environmental investment and energy consumption intensity (Xiao et al., 2022). In addition, Cui et al. (2022) also found that the green credit policy can improve firms’ total factor productivity by promoting technological innovation and resource allocation efficiency.

Regarding export quality, scholars have examined factors influencing the improvement of China’s export quality from various perspectives. Some studies argued that the improvement of China’s export quality is mainly due to internal factors such as financing constraints (Phillips and Sertsios, 2013), the minimum wage standard (Xu and Wang, 2016), the degree of technology market development (Dai, 2018), the liberalization of foreign entry (Hou et al., 2021), and tax incentives (Kong and Xiong, 2021). However, the majority of the literature agreed that the export quality of Chinese firms is shaped by external factors, such as import (Xu and Mao, 2018), foreign direct investment (Li et al., 2019), the liberalization of trade (Chen et al., 2017; Shen and Mao, 2017), trade barriers (Zhen and Zhen, 2020), and regional trade agreements (Sun, 2021). Among the existing literature, the study investigating the impact of credit constraints on firms’ export quality is the most relevant to this study. Phillips and Sertsios (2013) examined the relationship between quality decisions and financial distress in the airline industry and found a negative relationship. Fan H et al. (2015) verified that tighter credit constraints would force firms to produce lower-quality products both theoretically and empirically. Li and Lu (2018) constructed an index of the export green-sophistication, which reflected the export quality of the firm and conducted an analysis of the effects of financing constraints on it. They found that the capability of obtaining loans or trade credit helps firms to improve their export green-sophistication.

Because of the increasing significance of green development, the impact of environmental regulation on export quality has recently attracted much attention. After constructing an environmental regulation index, Ge et al. (2020) demonstrated that environmental regulation has a significant positive effect on the green technology content of firms’ export. Xie et al. (2020) also showed that environmental regulation could significantly improve the export quality of the manufacturing industry, with the process and product productivity being two possible impact channels. Some scholars, however, have found that strict environmental regulation will transfer pollution control costs to firms and, thus, reduce their export competitiveness. For example, Deng et al. (2021) affirmed that export product quality is negatively affected by the implementation of pollution reduction targets. Ma (2022) found that China’s pilot policy about trading carbon emissions is negatively correlated with the export product quality of enterprises in the pilot areas.

The green credit policy applied in China is an essential supplement to traditional environmental regulations and a combination of environmental regulation and credit policy. The existing literature investigated the causal effect of credit policy and environmental regulation on export quality and derived controversial conclusions, but the relationship between market-based environmental regulation, that is, the green credit policy and export quality, is seldom examined. Therefore, this study attempts to evaluate the impact of the green credit policy on export quality and examine the mechanism of the effect.

3 Theoretical mechanisms and hypotheses

3.1 Green credit policy and export quality

The purpose of the green credit policy is to curb the expansion of energy-intensive and highly polluting industries to relieve the increasingly prominent contradiction between economic growth and environmental protection. The policy requires commercial banks to treat the environmental compliance of firms as one of the necessary conditions for the approval of loans and to control credit issuance to projects that violate environmental laws or industrial policies.

In contrast to traditional regulations released by the government, the green credit policy is a market-based method that will further influence other behaviors of firms through financing constraints. Export firms need external financing for certain activities such as upgrading the quality of export products, investing in manufacturing and marketing capabilities, and maintaining an overseas marketing network. Financing constraints caused by the green credit policy will make highly polluting firms unable to obtain adequate loans from banks, resulting in insufficient funds to continue production and investment, thus affecting product quality improvement. At the same time, the green credit policy grants credit facilities for green projects. It will provide incentives for firms to achieve energy conservation and emission reduction. Firms affected by this policy, especially those with high pollution, may, therefore, prioritize green transformation, reduce the production of less environmental-friendly products and improve the efficiency of resource allocation, and, thus, improve the export quality. The central hypothesis of this study is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 1. The green credit policy can significantly promote the export quality of highly polluting firms.

3.2 Mediation effect of green innovation

There are two opposite opinions on the economic effects of environmental regulation policies. The first is the pollution haven hypothesis, which holds that developing countries can enhance their competitive edge in pollution-intensive products by relaxing environmental regulations, while strictly implementing environmental regulations will make them lose their competitive edge and hinder economic growth (Cole et al., 2010; Hering and Poncet, 2014). The other view, based on Porter’s hypothesis, asserts that reasonable environmental regulation can stimulate firms’ technological innovation and promote the long-term economic growth of the country (Porter and Vanderlinde, 1995; Song et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2021).

What impact the green credit policy will bring to firms is also controversial and depends on how firms respond to it. When facing credit constraints, firms might passively shrink the capital investment or actively take actions to improve their environmental performance. Different response strategies will bring different results to the long-term development of firms. The goal of the green credit policy is to stimulate the internal motivation of firms to reduce emissions, and the credit constraints it imposes on firms are not intended to restrain their development. Instead, it hopes to make heavily polluting firms withdraw from projects that may cause severe environmental problems through credit constraints and encourage them to develop clean projects and adopt green and low-carbon production technologies. The second hypothesis of this study is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 2. The green credit policy can improve the export quality of highly polluting firms by promoting green innovation.The mechanism of how the green credit policy affects export quality is shown in Figure 3.

4 Data and method

4.1 Sample selection and core variables

4.1.1 Sample selection

To empirically test the impact of the GCG on the export quality of listed firms, the sample interval is set from 2003 to 2016. According to Liu et al. (2019) and Wang et al. (2022), the definition of heavily polluting firms depends on the industry a firm belongs to. Specifically, if a firm belongs to the thermal power, steel, petrochemical, cement, nonferrous metals, or chemical industries, it will be recognized as a heavily polluting firm according to the “Announcement on the Implementation of Special Emission Limits for Atmospheric Pollutants” issued by the Ministry of Environment Protection (MEP) in 2013.

In order to control the financing condition of firms, this study merged data from the China Customs Database and the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database to obtain the final sample. Referring to Qi and Cheng (2022), this study first matches the samples in the two databases according to the firm’s name and then further matches the left samples according to their address, legal representative, postal code, and the last seven digits of the telephone number of the firm. Since industrial firms with high pollution emissions are more sensitive to environmental regulation policies and are the primary force in export, non-industrial firms are deleted from the sample. In addition, samples with missing data or significant losses (marked ST or *ST) during the sample period are also excluded.

4.1.2 Core variables

4.1.2.1 Export quality

In this study, we adopted the methods used by Khandelwal (2010), Shi et al. (2013), and Fan H C et al. (2015) to measure the export quality as follows:

where qinjt is the quantity of the 8-digit product n exported by firm i to country j in year t. When the price is fixed, the greater the consumer demands for imported products, the higher the product quality is. α is the moving parameter for the demand curve of the product n, and when the price pinjt is fixed, the demand curve will move outward with the improvement of the product quality. Parameter γinjt represents the consumers’ vertical evaluation of the quantity, which reflects the quality that all consumers can intuitively feel and are willing to pay for. The parameter εinjt represents the consumers’ horizontal evaluation of quantity, which refers to the level of product differentiation and explains why some consumers are willing to pay while some are unwilling to. өγinjt + εinjt represents other random factors that affect demand when the price is fixed, such as the time effect, specific effects of different industries, distance and cultural differences between the two trade parties, exchange rate fluctuations, and style differences.

Based on Eq. 1, regressing the export quantity and price of the product i at the three dimensions of the firm-product-import country yields the following equation after taking the logarithm:

where tinjt is the residual term that includes the information on product quality. When the price is fixed, if the product’s market share rises, the product’s quality rises correspondingly. In order to make it more accurate, we translated the formula into

After standardizing (3), we obtain the following:

where max qualitynjt and qualitynjt represent the highest and lowest quality of product n, respectively, and the standardized quality indicators are located between [0,1]. Finally, the export quality index of firm i is defined as follows:

where

The data used to calculate export quality are from China Customs Database.

4.1.2.2 Green innovation

In order to investigate the willingness of firms to invest in green innovation, this study uses the ratio of the number of green patent applications to the total number of firm patent applications to measure the level of green innovation gi.

The data on patent applications of listed firms are from the China Intellectual Property Office (CIPO). Based on these data, the green patent applications are identified according to the International Patent Classification (IPC) code published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

4.1.2.3 Control variables

According to Li and Lu (2018) and Qi and Cheng (2022), the control variables included in this study should consist of export amount, total assets, the number of employees, firm age, asset–liability ratio, return on assets, and Tobin Q value. Except for the last three variables, other variables are represented by lnex, lnasset, lnlabor, and lnage, respectively, after taking the logarithm. The asset–liability ratio is the ratio of total assets to total liabilities of the firm and is denoted as dar. The return on assets is the ratio of the total operating income to total assets and is denoted as roa. The Tobin Q value is the ratio of the firm market value to capital reset cost and is denoted as tobinq.

The data on control variables except export amount are collected from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) Database, which contains the financial data on Chinese listed firms.

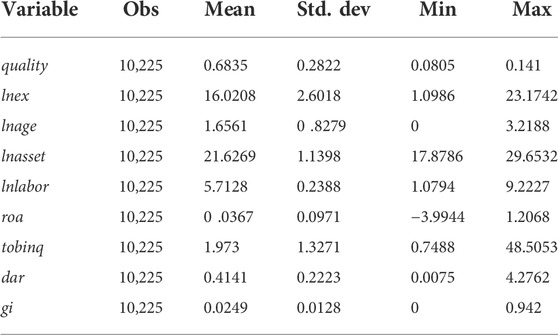

The descriptive statistical values for each variable are shown in Table 1.

4.2 Model setting

4.2.1 Difference-in-difference model

The difference-in-difference (DID) method is a popular research method for policy evaluation in empirical econometrics. It was first proposed in natural science and was introduced into economics by Ashenfelter (1978). The basic idea of the DID method is to treat a new policy as a natural experiment exogenous to the economic system. It identifies the average treatment effect of the policy by comparing the difference between the treatment group and the control group. Compared with traditional methods for policy evaluation, the DID method can effectively alleviate the problem of endogeneity and the problem caused by omitted variables.

Much literature has adopted the DID approach within the field of environmental policy evaluation. For example, Liu et al. (2019) regarded the promulgation of the GCG as a quasi-natural experiment and conducted a DID analysis; they discovered that the debt financing capacity of heavily polluting enterprises is negatively affected by this policy. Ye (2022) conducted an ex-post policy evaluation of the Ecological Red Lines (ERL) policy on the improvements of industrial structure and residents’ health based on the DID model and found a positive effect.

By referring to Liu et al. (2019), this study constructs the DID model used to examine the impact of the green credit policy on firm export quality as follows:

where the subscript i represents the individual (firm), and t represents the time (year). The explained variable qualityit is the export quality of the firm i in year t. treati is a dummy variable which equals 1 if firm i is a heavily polluting firm and is 0 otherwise. postt is also a dummy variable, and it equals 1 if t ≥ 2012 and equals 0 if t < 2012. treati × postt is the core variable of this study, whose coefficient reflects the impact of the GCG on the export quality of firms. Xit represents the control variables. μi and γt denote firm-fixed and time-fixed effects, respectively. Province × time indicates province-specific time trends, and sector × time indicates industry-specific time trends. These two variables can control factors that will vary with time at the provincial and industry level. εit is a stochastic disturbance term.

4.2.2 Mediation model

Revealing the relationship between variables is an important objective of quantitative research. Mediation effect analysis can help explore how the influence of the independent variable X on the dependent variable Y is realized through mediator M, and it has become a critical statistical method in multivariate research.

In evaluating environmental regulation policies, some studies used the mediation effect analysis and found the micro transmission mechanisms of these policies. For example, Dai (2018) discovered that the development of the technology market has significantly increased the technological complexity of high-tech exports, and this is realized by the increase in R&D investment. Xiao et al. (2022) found that the green credit policy can promote environmental protection by increasing environmental investment.

In order to detect whether the green credit policy can promote the improvement of the firm export quality by improving their green innovation, this study refers to Dai (2018) and sets the mediation models as follows:

where in the model (7), the explained variable giit is the green innovation of firm i in year t. Model (8) is similar to model (6) but adds giit as an independent variable. The stepwise regression method is taken to test the mediation effect. The general steps of it are as follows: if β1 is not significant in the model (7), it means the causal relationship between the green credit policy and green innovation is weak or does not exist, so there would be no need to regress model (8); if β1, λ1, and λ2 are all significant in both model (7) and model (8) and λ1 is significantly closer to 0 than α1, it indicates that green innovation is the mediation variable of the green credit policy to improve the export quality of firms.

5 Empirical analyses and results

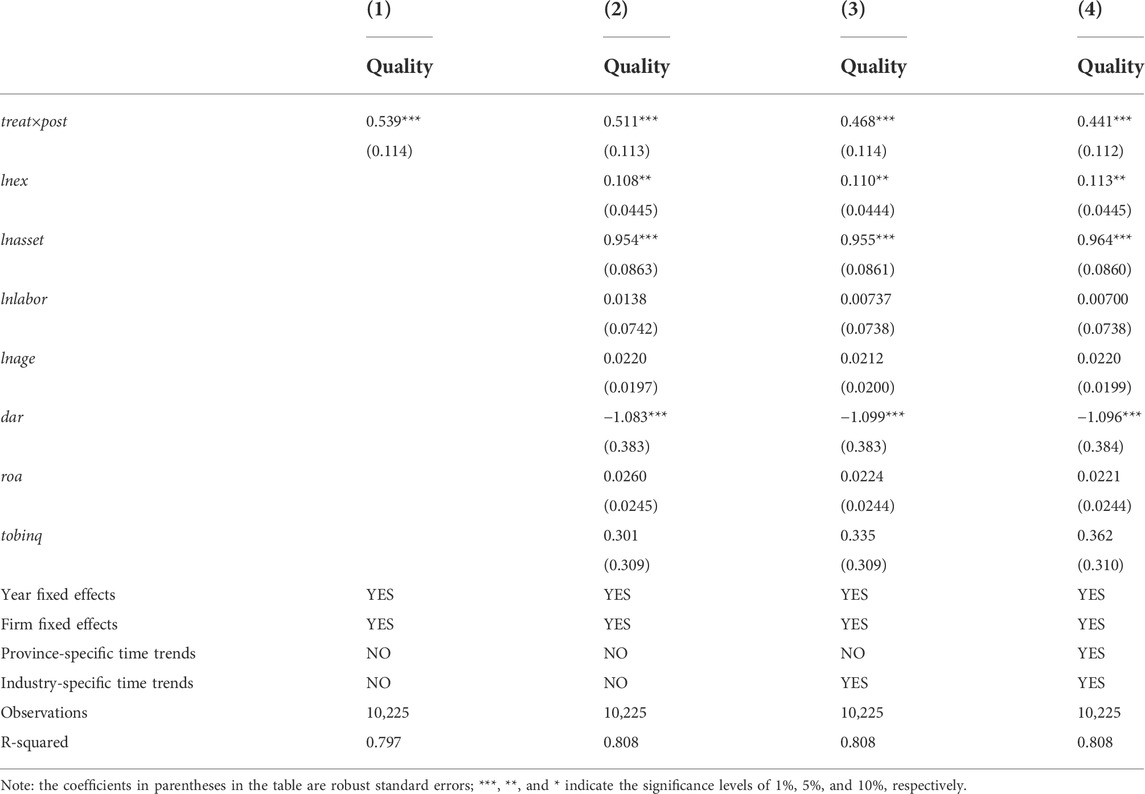

5.1 Benchmark regression results

In order to test Hypothesis H1, the results obtained from the regression of the GCG on export quality are presented in Table 2. Column (1) does not include the control variables, province-specific time trends, and industry-specific time trends, and these variables are gradually added in columns (2) to (4). The coefficients of treat × post in columns (1) to (4) are significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that after the implementation of the GCG, the export quality of heavily polluting firms has been significantly improved. Specifically, the coefficient of treat × post in column (4) is 0.441, meaning that the green credit policy increases the export quality of highly polluting firms (treated group) by 0.441 compared to other firms (control group). Therefore, Hypothesis H1 is proved.

In terms of control variables, the coefficients of the export amount and total assets are positive and significant at 5% and 1% levels, respectively, reflecting that firms with a larger export scale and more considerable total assets have higher export quality. The coefficient of the asset–liability ratio is negative at the 1% level, indicating that the increase of the asset liability of firms is harmful to the improvement of the export quality of firms. No statistically significant correlation is observed between other control variables and export quality.

5.2 Robustness test

5.2.1 Parallel trend test and placebo test

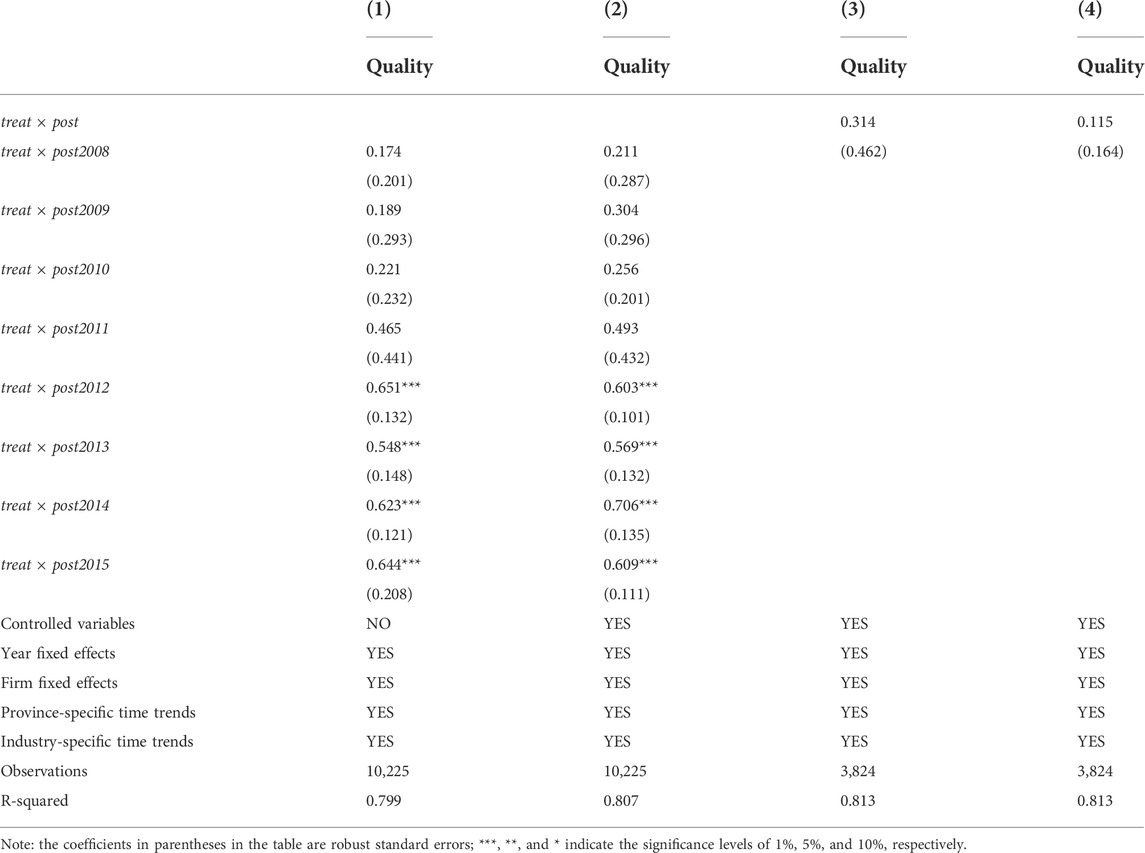

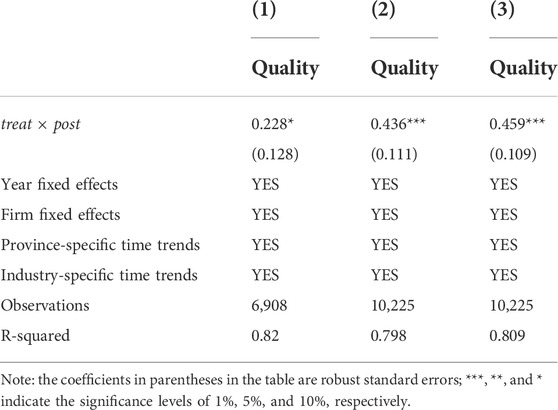

This study tests whether the parallel trend hypothesis is satisfied in the treatment and control groups before the implementation of the GCG based on Eq. 1. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 3 are the regression results, with no control variables added in column (1) and control variables added in column (2). It can be seen that the coefficients of treat × post2008, treat × post2009, treat × post2010, and treat × post2011 are insignificant, and the coefficients afterward are significantly positive, which are consistent with the parallel trend hypothesis.

Subsequently, this study conducts a placebo test, assuming that the GCG were implemented in 2010 and 2011, respectively, and performs DID regression after removing the samples of 2012 and beyond. The regression results are shown in columns (3) and (4) in Table 3. It is found that the difference in the export quality between treatment and control groups is insignificant, indicating the robustness of this study’s results.

5.2.2 Eliminating the impact of energy policies and environmental regulations

While implementing the GCG, China has also introduced some energy policies that would also affect the environmental performance and innovation of firms. These policies may interfere with the impact of the GCG, so it is necessary to separate their impact.

China’s energy policies can generally be divided into energy structure adjustment policies and energy conservation policies (Deng and Farah, 2020). In terms of energy structure adjustment policies, there is a strong regional heterogeneity. They can be subdivided into the policy promoting the transformation of traditional energy and the policy supporting the development of clean energy. Since China’s energy production and consumption have been dominated by coal for an extended period of time, the government prefers to implement the policy of promoting the transformation of traditional energy in major coal-consuming provinces such as Shandong, Hebei, and Shanxi. On the other hand, provinces in the western region, such as Ningxia, Qinghai, and Gansu, possess prominent natural endowment advantages in utilizing clean energy, enabling the government to implement the policy of supporting the development of clean energy (Hasanbeigi et al., 2013). As for energy conservation policies, the Chinese government issued the “Notice on the Demonstration and Promotion of Energy Conservation and New Energy Vehicle” in 2009. It has catered to and provided financial subsidies for energy conservation and purchasing of new energy vehicles. A total of 26 cities are selected as pilot cities for this policy (Lo, 2014; Si et al., 2018).

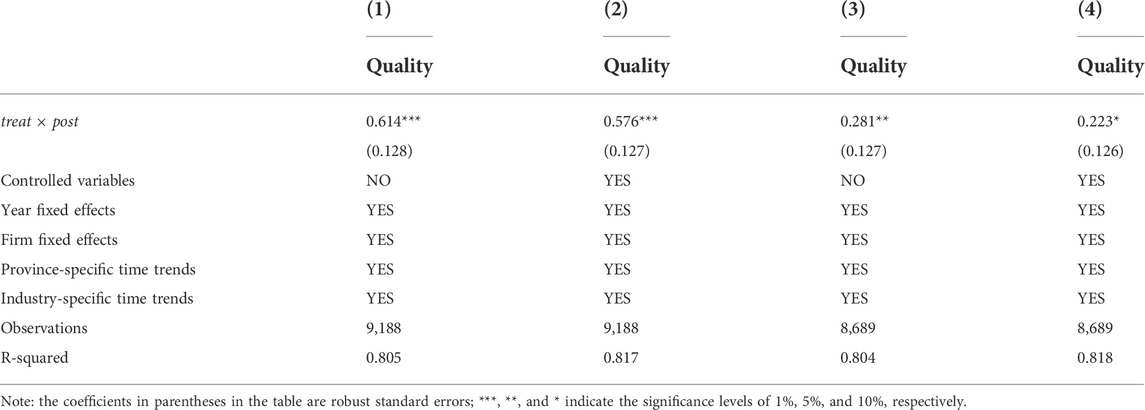

To effectively strip away the potential impact of energy policies on export quality, this study drops sample firms that are from China’s major coal consumption provinces (Inner Mongolia, Jiangsu, Shandong, Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi, and Henan) and clean energy-producing provinces (Ningxia, Yunnan, Qinghai, Gansu, and Xinjiang), as well as those belonging to energy-saving policy cities. Specific estimation results are shown in column (1) of Table 4, and the DID coefficient is significant at the 5% level. This result reflects that after excluding the potential impact of energy policies, the GCG can still positively enhance the export quality.

During the sample period, several environmental regulatory policies were implemented in China. At the urban level, China adopted and implemented the “Acid Rain Control Area and Sulfur dioxide Pollution Control Area Plan” in 1998. It limited the number of sulfur dioxide emissions in certain cities. In 2010, China implemented a pilot policy for low-carbon cities, encouraging pilot cities to actively adopt carbon emission reduction policies for low-carbon transformation and upgrading. In 2012, China issued the “Ambient Air Quality Standards (2012).” In order to exclude the influence of environmental regulation on the results of this study, the intersection term of city fixed effects and year fixed effects are included in model (1). The regression results are shown in column (2) of Table 4. The results present that the DID coefficient is still significantly positive at the 1% level, which verifies the robustness of the results.

At the provincial level, the Chinese government implemented a carbon trading pilot policy in 2013, and the carbon emissions of seven provinces have been restricted. In addition, some time-varying factors like the R&D intensity, economic development level, and industrial structure in different provinces may also influence the export quality. Therefore, this study adds the interaction term of province fixed effects and year fixed effects to model (1). The specific regression results are shown in column (3) of Table 4. The main results derived are barely changed.

5.2.3 Excluding the impact of important events

Some important events like the Global Financial Crisis and the Beijing Olympics that occurred during the sample period of this study might interfere with the estimated results.

The global financial crisis of 2007–2009 greatly influenced China’s economic growth and energy consumption (Yuan et al., 2010), and it may also affect the export quality of firms. In order to eliminate the potential impact of the global financial crisis, the samples of 2008 and 2009 are removed from the sample. The specific regression results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 5. It is observed that the DID coefficients are significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the conclusion of this study is still robust after excluding the interference of the global financial crisis.

During the Beijing Olympic Games in China, Beijing and its surrounding provinces and cities jointly implemented the blue-sky and clean energy construction projects. Therefore, holding the Olympic Games will enable firms to accelerate green investment in a short time and reduce pollution emissions (Wang et al., 2009; Mijling et al., 2009; Okuda et al., 2011). This will affect the quality of export and interfere with the results of this study. In order to eliminate the potential impact of the Beijing Olympic Games, this study removes the samples from Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Liaoning. The regression results are displayed in columns (3) and (4) of Table 5. The results present that the DID coefficients are significantly positive at the10% level, indicating that the main conclusions of this study are robust.

5.3 Mediation effect of green innovation

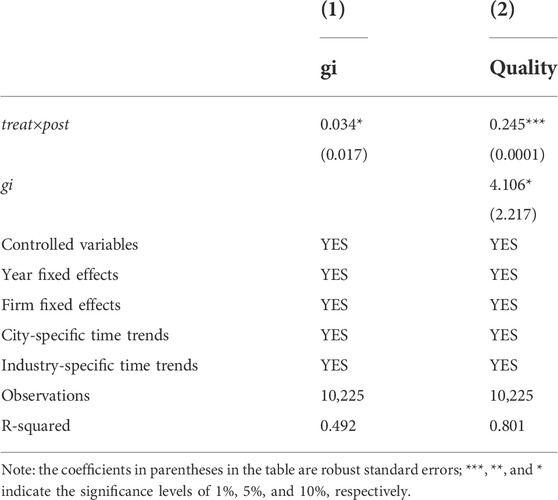

In order to test Hypothesis H2, the mediation effect of green innovation is analyzed based on Eqs 7 and 8, and the regression results are displayed in columns (1) and (2) of Table 6.

The explained variable of column (1) is green innovation, and the estimation result of it shows that the DID coefficient is significantly positive, indicating that the GCG can significantly enhance firms’ green innovation level. The explained variable in column (2) is export quality, and the explanatory variables are gi and treat × post. The result of it shows that the coefficients of treat × post and the gi are both significantly positive, and the value of the former is much smaller than its counterpart in the benchmark regression, which means that the GCG can improve the export quality of firms by increasing their green innovation and, thus, proves Hypothesis H2. One possible explanation behind this result is that the promulgation of the GCG would limit heavily polluting firms’ access to bank credit. If they want to apply for credit facilities, they have to perform green transformation and carry out high-quality green innovation activities. When the level of green innovation of firms has been improved, firms can consume fewer resources when producing products, thus reducing carbon emissions and production costs. The export quality could be enhanced while firms also gain a competitive advantage in the export market.

5.4 Heterogeneity analysis

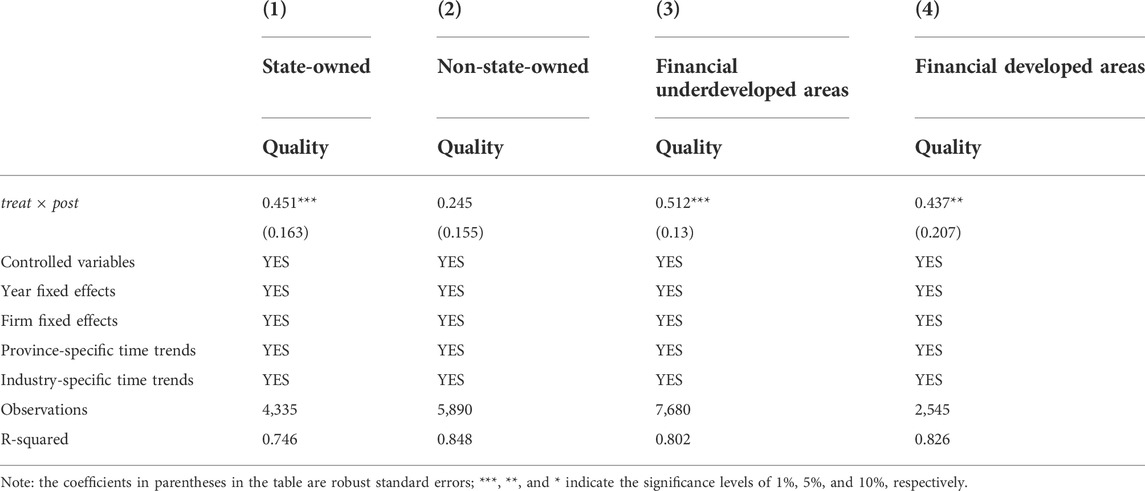

Considering the variation in the property rights structure of different firms and the variation in the degree of financial development of different regions (Cull and Xu, 2004; Jing et al., 2013), it is necessary to further test whether the impact of the implementation of the GCG on the export quality of firms varies.

In terms of the type of firm, the samples are divided into state-owned and non-state-owned groups in this article. In terms of the degree of regional financial development, the development degree score of each regional market included in the market index report of Wang et al. (2018) is utilized to measure the degree of regional financial development. If a region’s score is higher than the median of the total sample, it is regarded as a financially developed region. Otherwise, it will be deemed as a financially underdeveloped region.

The specific results of the heterogeneity analysis are displayed in Table 7. It can be seen that the DID coefficient of column (1) is significantly positive and is greater than the coefficient in column (2), indicating that the GCG has a greater impact on the export quality of state-owned firms. This phenomenon may be because, compared to non-state-owned firms, state-owned firms possess unique resources from their government–firm relationship and undertake more social responsibility in energy conservation and emissions reduction. Hence, after the implementation of the GCG, state-owned firms will actively carry out more high-quality green innovations and improve the quality of exports.

The DID coefficient in column (3) is significantly greater than that in column (4). This indicates that the GCG has a larger impact on the export quality of firms in financially underdeveloped areas. The reason might be that the degree of regional financial development would also affect the specific implementation of the green credit policy. When a region’s financial system is more developed, firms there would have a wider channel for financing. Therefore, in areas with rich financial resources, the regulatory role of the green credit policy will be significantly weakened. However, in areas with underdeveloped financial systems, firms often face a strict financing environment and possess limited financing choices. As a primary financing source, firms depend highly on bank loans. As a result, for the heavily polluting firms in the areas with undeveloped financial development, the GCG possess a substantially stronger effect on improving their export quality.

6 Conclusion and implications

The green credit policy applied in China is an essential supplement to traditional environmental regulations, which has successfully achieved the desired objectives in environmental protection. However, as a combination of the environmental regulation policy and credit policy, it may also result in unintended impacts on other aspects of the firms since it has adjusted the difficulty of access to bank loans of different firms.

Based on the data on Chinese listed firms from 2003 to 2016, this study takes the promulgation of the GCG as a quasi-natural experiment and uses the DID method to empirically examine the impact of the green credit policy on the export quality of firms. The following conclusions are derived from the investigation. First, the DID regression results show that after the implementation of the green credit policy, the export quality of heavily polluting firms has increased by 0.441 compared with other firms, and this increment is statistically significant. Second, the result of the mediation analysis indicates that the influence of the green credit policy on heavily polluting firms’ export quality is realized through green innovation. This reflects that the credit constraint imposed on heavily polluting firms and the credit facilities granted for green projects by this policy have stimulated them to invest in and adopt green and low-carbon production technologies, thus helping improve their export quality. Third, the enhancement effect on the export quality brought by the green credit policy is significantly reflected in state-owned firms and firms in financially underdeveloped areas.

The findings of this study provide some instructions to firms, banks, and other developing countries’ policymakers. First, heavily polluting firms should place more emphasis on sustainable development under the current situation where environmental protection has received substantial attention. They should seize the opportunity given by the green credit policy, increase investment in green projects and carry out high-quality green innovation activities. The realization of cleaner production brought by this effort could help them to occupy an advantageous position in the fierce global competition.

Second, banks should conscientiously implement green credit policies and take environmental performance as an important consideration in their credit decision-making process. Moreover, they should also adopt differentiated measures for different types of firms to maximize the effectiveness of this policy. In particular, targeted support should be given to private firms or firms from financially underdeveloped regions that are willing to make environmental investments but lack funds.

Third, other developing countries that are currently in the stage of rapid economic development but have high energy consumption and serious environmental pollution could take China’s green credit policy as a reference. The adoption of a properly designed market-based environmental policy could help them to achieve the improvement of the environment while improving other performances of firms in their countries.

Although this research study has gained certain results, there are also some deficiencies. First, the definition of the heavily polluting firm used in this study is based on its industry category. However, it has to be noted that even in the same industry, there is still a certain degree of difference in the environmental performance of firms. Future studies should consider a more precise definition of heavily polluting firms. Moreover, this study uses the export data on Chinese firms to study the impact of the implementation of the green credit policy on the quality of their export products. However, it does not further explore whether there are heavily polluting firms withdrawing from the export market under the influence of this policy and the number of these quitted firms. If the green credit policy promotes the improvement of the export quality of some firms and, at the same time, causes some firms to withdraw from the export market, it may also have a short-term adverse impact on China’s economic development. This question deserves further study in the future.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found at: https://www.gtarsc.com/

Author contributions

GY: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ashenfelter, O. C. (1978). Estimating the effect of training programs on earnings. Rev. Econ. Stat. 60, 47. doi:10.2307/1924332

Bing, Z., Yang, Y., and Bi, J. (2011). Tracking the implementation of green credit policy in China: Top-down perspective and bottom-up reform. J. Environ. Manage. 92 (4), 1321–1327. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.12.019

Chen, W., Wang, Y., and Sun, W. (2017). Trade liberalization, import competition, and technological complexity in Chinese industry. J. Int. Trade 1, 50–59. (China Journal).

Cole, M. A., Elliott, R. J. R., and Okubo, T. (2010). Trade, environmental regulations and industrial mobility: An industry-level study of Japan. Ecol. Econ. 69 (10), 1995–2002. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.05.015

Cui, X., Wang, P., Sensoy, A., Nguyen, D. K., and Pan, Y. (2022). Green credit policy and corporate productivity: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 177, 121516. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121516

Cull, R., and Xu, L. C. (2004). Who gets credit? The behavior of bureaucrats and state banks in allocating credit to Chinese state-owned enterprises. J. Dev. Econ. 71 (2), 533–559. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00039-7

Dai, K. (2018). The influence of technology market development on export technology complexity and its impact mechanism. China. Ind. Econ. 7, 19–32. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2018.07.006

Deng, H. F., and Farah, P. D. (2020). China's energy policies and strategies for climate change and energy security. J. World Energy Law Bus. 13 (2), 141–156. doi:10.1093/jwelb/jwaa018

Deng, Y. P., Wu, Y. R., and Xu, H. L. (2021). On the relationship between pollution reduction and export product quality: Evidence from Chinese firms. J. Environ. Manage. 281, 111883. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111883

Fan, H. C., Li, Y. A., and Yeaple, S. R. (2015). Trade liberalization, quality, and export prices. Rev. Econ. Stat. 97 (5), 1033–1051. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00524

Fan, H., Lai, E. L. C., and Li, Y. A. (2015). Credit constraints, quality, and export prices: Theory and evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 43 (2), 390–416. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2015.02.007

Feng, L., Li, Z. Y., and Swenson, D. L. (2017). Trade policy uncertainty and exports: Evidence from China's WTO accession. J. Int. Econ. 106, 20–36. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2016.12.009

Ge, T., Li, J. Y., Sha, R., and Hao, X. L. (2020). Environmental regulations, financial constraints and export green-sophistication: Evidence from China's enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 251, 119671. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119671

Hasanbeigi, A., Lobscheid, A., Lu, H. Y., Price, L., and Dai, Y. (2013). Quantifying the co-benefits of energy-efficiency policies: A case study of the cement industry in Shandong province, China. Sci. Total Environ. 458, 624–636. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.031

Hering, L., and Poncet, S. (2014). Environmental policy and exports: Evidence from Chinese cities. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 68 (2), 296–318. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2014.06.005

Hou, X. Y., Shi, Y. Y., and Sun, P. Y. (2021). Foreign entry liberalization and export quality: Evidence from China. Contemp. Econ. Policy 39 (1), 205–219. doi:10.1111/coep.12498

Jing, Z., Chen, J., and Liu, X. (2013). Credit mobility across regions, financial development and economic growth:an empirical study based on provincial panel data in China. Rev. Invest. Stud. (China Journal) 30 (6), 63–76.

Khandelwal, A. (2010). The long and short (of) quality ladders. Rev. Econ. Stud. 77 (4), 1450–1476. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937X.2010.00602.x

Kong, D. M., and Xiong, M. X. (2021). Unintended consequences of tax incentives on export product quality: Evidence from a natural experiment in China. Rev. Int. Econ. 29 (4), 802–837. doi:10.1111/roie.12499

Koopman, R., Wang, Z., and Wei, S. J. (2014). Tracing value-added and double counting in gross exports. Am. Econ. Rev. 104 (2), 459–494. doi:10.1257/aer.104.2.459

Li, C. Q., and Lu, J. (2018). R & D, financing constraints and export green-sophistication in China. China Econ. Rev. 47, 234–244. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2017.08.007

Li, R. Q., Liu, Y. P., and Bustinza, O. F. (2019). FDI, service intensity, and international marketing agility: The case of export quality of Chinese enterprises. Int. Mark. Rev. 36 (2), 213–238. doi:10.1108/Imr-01-2018-0031

Liu, X., Wang, E., and Cai, D. (2019). Green credit policy, property rights and debt financing: Quasi-natural experimental evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 29, 129–135. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2019.03.014

Lo, K. (2014). A critical review of China's rapidly developing renewable energy and energy efficiency policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 29, 508–516. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.09.006

Ma, B. (2022). Assessment of the impact of China's carbon emissions trading pilot policy on the export product quality. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2022, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2022/6458398

Mijling, B., van der A, R. J., Boersma, K. F., Van Roozendael, M., De Smedt, I., and Kelder, H. M. (2009). Reductions of NO2 detected from space during the 2008 beijing olympic games. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L13801. doi:10.1029/2009gl038943

Okuda, T., Matsuura, S., Yamaguchi, D., Umemura, T., Hanada, E., Orihara, H., et al. (2011). The impact of the pollution control measures for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games on the chemical composition of aerosols. Atmos. Environ. X. 45 (16), 2789–2794. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2011.01.053

Phillips, G., and Sertsios, G. (2013). How do firm financial conditions affect product quality and pricing? Manage. Sci. 59 (8), 1764–1782. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1120.1693

Porter, M. E., and Vanderlinde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 9 (4), 97–118. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.97

Qi, S. Z., and Cheng, S. H. (2022). The influence of China's pollution emissions trading system on the listed companies' export products' quality. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (14), 20145–20159. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17228-5

Shen, B., and Mao, Q. (2017). Does import trade liberalization affect the technological complexity of China's manufacturing exports. J. World Econ. 40, 52–75. (China Journal).

Shi, B., Wang, Y., and Li, K. (2013). Quality measurement of Chinese export products and its determinants. J. World Econ. 36, 69–93. (China Journal).

Si, S. Y., Lyu, M. J., Lawell, C. Y. C. L., and Chen, S. (2018). The effects of energy-related policies on energy consumption in China. Energy Econ. 76, 202–227. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2018.10.013

Song, Y., Yang, T., and Zhang, M. (2019). Research on the impact of environmental regulation on enterprise technology innovation—An empirical analysis based on Chinese provincial panel data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 21835–21848. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-05532-0

Sun, J. (2021). Do higher-quality regional trade agreements improve the quality of export products from China to "One-Belt one-road" countries? Asian Econ. J. 35 (2), 142–165. doi:10.1111/asej.12241

Sun, J., Wang, F., Yin, H., and Zhang, B. (2019). Money talks: The environmental impact of China's green credit policy. J. Pol. Anal. Manage. 38 (3), 653–680. doi:10.1002/pam.22137

Wang, F., Yang, S., Reisner, A., and Liu, N. (2019). Does green credit policy work in China? The correlation between green credit and corporate environmental information disclosure quality. Sustainability 11 (3), 733. doi:10.3390/su11030733

Wang, H. T., Qi, S. Z., Zhou, C. B., Zhou, J. J., and Huang, X. Y. (2022). Green credit policy, government behavior and green innovation quality of enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 331, 129834. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129834

Wang, X., Fan, G., and Hu, L. (2018). Report on market index by province in China. Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. (China).

Wang, X., Westerdahl, D., Chen, L. C., Wu, Y., Hao, J. M., Pan, X. C., et al. (2009). Evaluating the air quality impacts of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games: On-road emission factors and black carbon profiles. Atmos. Environ. X. 43 (30), 4535–4543. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.06.054

Weber, C. L., Peters, G. P., Guan, D., and Hubacek, K. (2008). The contribution of Chinese exports to climate change. Energy Policy 36 (9), 3572–3577. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.06.009

Xiao, Z., Yu, L., Liu, Y., Bu, X., and Yin, Z. (2022). Does green credit policy move the industrial firms toward a greener future? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.810305

Xie, J., Sun, Q., Wang, S., Li, X., and Fan, F. (2020). Does environmental regulation affect export quality? Theory and evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (21), 8237. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218237

Xu, H., and Wang, H. (2016). The effect of minimum wage standards on firms' export quality. J. World Econ. 39 (7), 73–96. (China Journal).

Xu, J., Chen, D., Liu, R., Zhou, M., and Kong, Y. (2021). Environmental regulation, technological innovation, and industrial transformation: An empirical study based on city function in China. Sustainability 13, 12512. doi:10.3390/su132212512

Xu, J., and Mao, Q. (2018). On the relationship between intermediate input imports and export quality in China. Econ. Transit. 26 (3), 429–467. doi:10.1111/ecot.12155

Yao, S., Pan, Y., Sensoy, A., Uddin, G. S., and Cheng, F. (2021). Green credit policy and firm performance: What we learn from China. Energy Econ. 101 (5), 105415. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105415

Ye, P., Li, J., Ma, W., and Zhang, H. (2022a). Impact of collaborative agglomeration of manufacturing and producer services on air quality: Evidence from the emission reduction of PM2.5, NOx and SO2 in China. Atmosphere 13 (6), 966. doi:10.3390/atmos13060966

Ye, P. (2022). Policy effects of ecological red Lines on industrial upgrading and health promotion: Evidence from China based on DID model. Front. Public Health 10, 844593. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.844593

Ye, P., Xia, S., Xiong, Y., Liu, C., Li, F., Liang, J., et al. (2020). Did an ultra-low emissions policy on coal-fueled thermal power reduce the harmful emissions? Evidence from three typical air Pollutants abatement in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (22), 8555. doi:10.3390/ijerph17228555

Yuan, C. Q., Liu, S. F., and Xie, N. M. (2010). The impact on Chinese economic growth and energy consumption of the Global Financial Crisis: An input-output analysis. Energy 35 (4), 1805–1812. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2009.12.035

Zhang, D. (2021). Green credit regulation, induced R&D and green productivity: Revisiting the Porter Hypothesis. Int. Rev. Financial Analysis 75, 101723. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2021.101723

Zhao, Y., Zhang, H. Y., Ding, Y. B., and Tang, S. T. (2021). Implications of COVID-19 pandemic on China's exports. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 57 (6), 1716–1726. doi:10.1080/1540496x.2021.1877653

Keywords: green credit policy, export quality, green technology innovation, environmental regulation, difference-in-difference

Citation: Yang G (2022) Can the green credit policy enhance firm export quality? Evidence from China based on the DID model. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:969726. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.969726

Received: 15 June 2022; Accepted: 11 July 2022;

Published: 08 August 2022.

Edited by:

Atif Jahanger, Hainan University, Haikou, ChinaReviewed by:

Penghao Ye, Hainan University, Haikou, ChinaYang Yu, Hainan University, Haikou, China

Ashar Awan, Nişantaşı University, Istanbul, Turkey

Copyright © 2022 Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ge Yang, Z3lfd2h1MjAyMUAxMjYuY29t

Ge Yang

Ge Yang