- 1Institute of Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 2Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Can moments of viral media activity transform into enduring activist movements? The killing of Cecil the lion by a trophy hunter in Zimbabwe in 2015 attracted global attention and generated enduring conservation activism in the form of monetary donations to the research unit that was studying him (WildCRU). Utilizing a longitudinal survey design, we found that intensely dysphoric reactions to Cecil's death triggered especially strong social cohesion (i.e., “identity fusion”) amongst donors. Over a 6-month period, identity fusion to WildCRU increased amongst donors. In addition, in line with an emerging psychological model of the experiential antecedents of identity fusion, cohesion amongst donors increased most for those who continued to reflect deeply on Cecil's death and felt his death to be a central event in their own lives. Our results highlight the profound capabilities of humans to commit resources to supporting others who are distant in space and time, unrelated culturally or biologically, and even (as in this case) belonging to another species altogether. In addition, our findings add to recent interdisciplinary work uncovering the precise social mechanisms by which intense group cohesion develops.

Introduction

Cecil the lion's death in 2015 at the hands of a trophy hunter prompted one of the largest reactions in wildlife conservation history (Macdonald et al., 2016a). Global attention to Cecil's story quickly generated over $1 million in donations, from thousands of individual donors, to the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), the Oxford University group studying Cecil at the time. Past analyses of the Cecil case and others like it have focused on the factors that trigger a viral media response (Berger and Milkman, 2012; Macdonald et al., 2016a). Considering the dire state of lion conservation (Bauer et al., 2015), Macdonald and colleagues asked whether the “Cecil Moment” presaged a significant shift in commitment to lion conservation: a “Cecil Movement”—a metaphor for a world view in which humanity places a higher value on, and therefore conserves better, not just lions, but wildlife, nature and the wider environment (Macdonald et al., 2016a). Here, we examine this shift empirically.

Our examination is guided by recent work on the social psychology of pro-group commitment. Accumulating studies show that numerous forms of prosociality, including sacrificing one's life for others, are motivated by a particularly lasting form of social cohesion termed “identity fusion” (Swann et al., 2009; Buhrmester and Swann, 2015). People who are strongly fused to a group (e.g., a nation or religion) subjectively experience a visceral sense of oneness with that group, and view fellow members as kin (Buhrmester et al., 2015). For fused persons, personally costly acts that benefit the group can be seen as a moral duty (Swann et al., 2014), compelling them, for instance, to defend their brother-in-arms on the battlefield (Whitehouse et al., 2014) or to donate to victims of terrorist attacks (Buhrmester et al., 2015). Identity fusion thus connotes an unusually affective and personal form of cohesion that is distinct from more cognitive forms of cohesion based on self and group categorization processes (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). Building on these studies, we sought to examine levels of identity fusion in relation to Cecil as well as WildCRU, as well as relationships to pro-social outcomes related to wildlife conservation.

Given that strong fusion promotes such a range of pro-social outcomes in various contexts, we also sought to ask what fosters fusion in the first place? Emerging evidence from anthropological and psychological studies suggests that particular kinds of shared group experiences are especially likely to cultivate identity fusion (see Buhrmester and Swann, 2015 for a review). Specifically, shared experiences that are infrequent and intensely dysphoric, such as painful or shocking group initiation rituals, tend to produce tight social bonds in many contexts and cultures (Whitehouse and Lanman, 2014). Such bonds may arise because these experiences trigger a process of personal reflection and meaning-making that enjoins one's personal identity to that of the group (Swann et al., 2012; Jong et al., 2015). Did these mechanisms of change in fusion occur for those following Cecil's story?

Cecil's story was both ordinary and extraordinary. As another instance of trophy hunting of a large predator, Cecil's story was not especially out of the ordinary (Macdonald et al., 2016a; and for further discussion of perspectives on trophy hunting relating to Cecil, see Di Minin et al., 2016; Macdonald et al., 2016b). Numbers of many large predators, including lions, are declining globally, in part due to trophy hunting (Loveridge et al., 2016). However, the viral spread of Cecil's story through the media as a singular, shocking moment shared by millions globally was extraordinary for at least a moment—relatively few stories of trophy hunting become global media headlines (Macdonald et al., 2016a). But could Cecil's story—a story that had no measurable material impact on the personal lives of donors, most of whom live half a world away in the U.S.—have had lasting changes in identity and motivation to champion conservationist causes? To examine these issues, we sought to test the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: In line with Whitehouse's model of the experiential causes of increased identity fusion (Whitehouse and Lanman, 2014), we hypothesized that participants who experienced high levels of dysphoria in response to Cecil's death would (1) experience strong fusion to Cecil, and (2) in turn, feeling that Cecil's death has bound WildCRU members closer together, experience strong fusion to WildCRU (Swann et al., 2012).

Hypothesis 2: According to theory (Swann et al., 2012; Whitehouse and Lanman, 2014), lasting changes in fusion to a group (e.g., WildCRU) take weeks to months to develop following a precipitating event. Insofar as Cecil's death served as an intensely dysphoric experience, in line with Whitehouse's model, we hypothesized that mean levels of fusion amongst donors to WildCRU would increase over time.

Hypothesis 3: Why might fusion to WildCRU increase over time? Past work suggests that intensely dysphoric, shared experiences promote continued ingroup discussion and reflection on the meaning of the event (Whitehouse, 1996, 2002; Jong et al., 2015). For some, continued reflection may foster the perception that the event was meaningful to one's personal identity and the identities of others who experienced the event similarly (Whitehouse and Lanman, 2014). Thus, we hypothesized that felt levels of dysphoria in the wake of Cecil's death would promote continued reflection and a sense that the event was central to the identities of oneself and other WildCRU donors. Furthermore, we hypothesized that fusion would increase most for participants who both (1) reported especially high amounts of reflection after Cecil's death, and (2) reported especially strong perceptions that Cecil's death has been a central experience for understanding one's personal identity and the identities of others who also experienced Cecil's death.

Hypothesis 4: Understanding the psychological mechanisms underlying what causes fusion to increase is important because strong fusion to a group motivates pro-group actions and attitudes (Buhrmester et al., 2015). We hypothesized that strongly fused WildCRU supporters would be especially engaged in continuing conservation efforts in various ways, such as continuing to donate to WildCRU, perceive wildlife to have significant inherent value, and to be especially social engaged with ongoing conservation efforts worldwide.

Methods

Participants

After the killing of Cecil the lion, thousands of people globally made donations to WildCRU and were sent occasional e-mail updates about the activities of the conservation organization, especially as it related to Cecil. In an e-mail update sent out in winter 2015, donors were invited to participate in a brief survey about their experiences learning about Cecil and could click on a link taking them to our survey. Participation was purely voluntary and no compensation was offered.

A total of 992 donor participants completed the survey at Time 1. Given the unexpectedly high number of responses, we decided to send out a second survey in the summer of 2016 (Time 2) to test additional hypotheses. All data were analyzed only after Time 2 data collection was completed. The survey was advertised similarly to Time 1 (i.e., at the end of an e-mail update to donors), and participation was again voluntary. There were 563 responses at Time 2, and 160 of those had also completed the Time 1 survey.

The 160 donors who participated in both surveys are the subject of this analysis. Most of the participants resided in the U.S. (89%), were female (83%), college graduates (80%), and worked full time (58%), with a mean age of 53.7 (SD = 12.02). Media saturation was especially high in North America, in large part due to coverage by the American television show Jimmy Kimmel Live (Macdonald et al., 2016a). Our participant demographics are consistent, at least in terms of country of residence, with viewers of the show. For an in-depth dissection of the role of the media in relation to Cecil's story, see Macdonald et al. (2016a). When asked about their donation frequency (see Supplementary Materials for survey details), 20% of participants reported that they had donated “very frequently to conservation organizations,” 31% “regularly,” 34% “only on occasion,” and 15% that their donation to WildCRU was their first to a conservation fund. All participants provided informed, written consent prior to the Time 1 survey.

Measures

Participants completed the following scales.

State Dysphoria

At Time 1, participants reported state dysphoria in reaction to Cecil's death via an 8-item checklist (M = 4.12, SD = 1.76, α = 0.63; scale range 0–8). The checklist asked participants to check whether they had, for instance, felt intense anger in the wake of Cecil's death.

Identity Fusion

At Time 1 and 2, participants also completed the pictorial identity fusion scales (Swann et al., 2009). The pictorial identity fusion scale asks respondents to choose which of five pictorial representations of “self” and “other” best reflect their relationship (Swann et al., 2009). The self and other are represented by two circles in five Venn-diagram options ranging from totally non-overlapping circles to totally overlapping. Participants completed the scales at each time point, once in reference to “Cecil the Lion” as the other target (Time 1: M = 3.59, SD = 1.23, Time 2: M = 3.64, SD = 1.12), and again in reference to “WildCRU” (Time 1: M = 3.05, SD = 1.03, Time 2: M = 3.26, SD = 1.03).

Depth of Reflection

At Time 2, participants also completed a four-item measure designed to assess their depth of reflection on Cecil's death (e.g., “When you reflect on this experience, to what extent does it come to mind in words or pictures as a coherent episode?,” α = 0.61, M = 2.31, SD = 0.80). These items were derived from Jong et al.'s (2015) operationalization of depth of reflection following a precipitating event.

Self/Group Centrality

At Time 2, we included a two-question measure designed to assess self/group centrality, i.e., the extent to which Cecil's death and story was a personally central experience as well as a similarly central experience for fellow conservationists (α = 0.63, M = 2.78, SD = 0.81). These items were derived from items developed by Newson et al. (2016) to assess the how central an event was perceived to be to one's personal identity.

Pro-group Outcomes

At Time 2, we additionally asked participants (1) whether they had donated again to WildCRU in the previous months (38% had done so), (2) two questions to measure the extent to which they felt that the lives of lions and all wildlife were invaluable (α = 0.91, M = 4.13, SD = 0.99), and (3) five questions to measure how engaged they had recently been in wildlife conservation efforts (e.g., “do you feel your thoughts about politicians and voting are now more influenced by wildlife conservation issues?,” (α = 0.71, M = 2.95, SD = 0.63). Note: Examinations of distribution normality of key variables (e.g., Q-Q plots, histograms) suggested the use of parametric tests.

Results

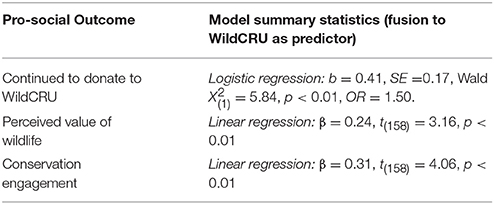

We followed the steps of statistical mediation (Hayes, 2013) to test Hypothesis 1 (i.e., that dysphoric reactions to Cecil's death generated fusion to Cecil, and in turn, fusion to fellow WildCRU supporters). In a first regression, represented by the “a path” in Figure 1, dysphoric intensity predicted fusion to Cecil, standardized regression coefficient, β = 0.27, t(157) = 3.45, p < 0.01. In a second regression, represented by the “c path” in Figure 1, dysphoric intensity predicted fusion to WildCRU, β = 0.23, t(154) = 2.90, p < 0.01. Then, in a third regression with dysphoric intensity and fusion to Cecil entered as simultaneous predictors of fusion to WildCRU, the effect of intensity on fusion to WildCRU, the c' path, was no longer statistically significant, β = 0.05, t(153) = 0.78, p = 0.45, while the effect of fusion to Cecil on fusion to WildCRU remained significant, β = 0.62, t(153) = 9.41, p < 0.01, with Sobel z = 3.46, p < 0.01, indicating the presence of statistical mediation. These results supported Hypothesis 1.

Figure 1. Mediation model showing the effect of dysphoria on fusion to WildCRU was mediated by fusion to Cecil.

We turned next to assessing Hypothesis 2 (i.e., that fusion to WildCRU would increase from Time 1 to Time 2). In line with our hypothesis, a paired t-test revealed that fusion to WildCRU increased overall (Time 1 M = 3.05, SD = 1.03 vs. Time 2 M = 3.26, SD = 1.03), t(153) = 2.41, p < 0.02. To our knowledge, this finding represents the first empirical demonstration of a longitudinal overall increase in fusion with a group resulting from a single precipitating event (in this case, the death of Cecil). This finding is unique given the remarkable stability of fusion that has been reported in response to other types of significant group events (Vázquez et al., 2017). We also examined via a paired t-test whether fusion to Cecil changed over time and found no change (M = 3.59, SD = 1.23) to Time 2 (M = 3.64, SD = 1.12), t(153) = −0.54, p = 0.59).

To examine Hypothesis 3, we first examined whether levels of dysphoric intensity reported at Time 1 predicted reported levels of reflection and self/group centrality measured at Time 2. We conducted two linear regressions, and found that Time 1 dysphoric intensity predicted both depth of reflection, β = 0.24, t(158) = 3.05, p < 0.01, and self/group centrality β = 0.25, t(158) = 3.24, p < 0.01 at Time 2. In line with Hypothesis 3, these results suggest that high levels of shock following Cecil's death tended to promote deep reflection and a sense that the event was central to the identities of oneself and other WildCRU members.

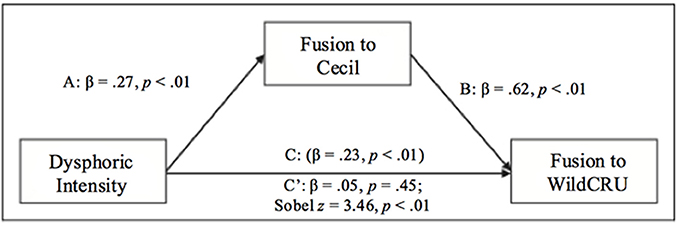

We next examined whether fusion increased most for participants who both (1) reported especially high amounts of reflection after Cecil's death, and (2) reported especially strong perceptions that Cecil's death has been a central experience for understanding one's personal identity and the identities of others who also experienced Cecil's death. To test this, we conducted a multiple regression with reflection, centrality, and their interaction as predictors of donors' change in fusion to WildCRU from Time 1 to 2. The analysis revealed a significant interactive effect of reflection and centrality on fusion change, β = 0.21, t(150) = 2.78, p < 0.01 (see Figure 2). The conditional effect of reflection on fusion change was significant only when centrality was high [i.e., +1 SD), β = 0.35, t(150) = 3.14, p < 0.01, but not low (i.e., –1 SD), β = –0.08, t(150) = −0.67, n.s., indicating that increases in fusion to WildCRU occurred for participants who engaged in high levels of reflection and also felt that Cecil's death was a central self and group experience, whereas participants who did not score highly on both the reflection and centrality measures reported little to no change or a decrease in fusion.

Figure 2. Interactive effect of reflection and centrality on change in fusion to WildCRU from Time 1 to Time 2.

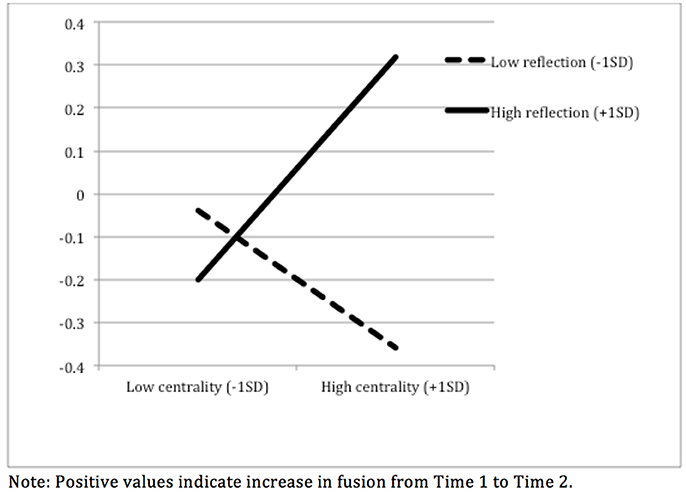

Finally, we examined Hypothesis 4 via a series of regressions (see Table 1 summary). In a logistic regression, mean fusion to WildCRU combined across both times predicted whether participants had made another donation to WildCRU beyond their initial donation [β = 0.41, SE = 0.17, Wald X2(1) = 5.84, p < 0.02, Odds Ratio = 1.50]. In two linear regressions, fusion to WildCRU also predicted perceptions of wildlife value [β = 0.24, t(158) = 3.16, p < 0.01], and conservation engagement [β = 0.31, t(158) = 4.06, p < 0.01]. Consistent with Hypothesis 4, these results demonstrate that strongly fused WildCRU supporters were especially engaged, continuing conservation efforts in ways that constitute a sustainable movement.

Given that of those who completed Wave 1 (N = 992), N = 160 completed Wave 2 (16.1% of the Wave 1 total), we also examined whether attrition was random or systematic. First, we examined whether Wave 1 participants who did not complete Wave 2 differed from those who completed both waves on demographic and key study variables. The two samples did not differ in terms of gender, Chi-square (1) = 0.11, p = 0.74; education, t(975) = 1.05, p = 0.30; occupation status, Chi-square (1) = 0.27, p = 0.60; age, t(956) = −1.74, p = 0.08; nor how they learned of Cecil's death, Chi-square (3) = 0.99, p = 0.80. Slightly more participants who completed both waves reported residing in a country other than the U.S. (11.3%) than participants who only completed Wave 1 (6.3%), Chi-square (1) = 5.01, p = 0.03. For the dysphoric reactions scale, participants who completed both waves reported no more dysphoria (M = 4.12, SD = 1.76) than those who did not participate at Time 2 (M = 3.97, SD = 1.84), t(990) = −0.97, p = 0.33. For the fusion scales, participants who completed both waves reported being slightly more fused to WildCRU (M = 3.05, SD = 1.03) and Cecil (M = 3.59, SD = 1.23) than those who only completed Wave 1 (WildCRU: M = 2.83, SD = 1.07; Cecil: M = 3.28, SD = 1.33), t(971) = −2.22, p = 0.03, and t(981) = −2.73, p = 0.006, respectively. It is plausible that those who initially felt a deeper connection with Cecil and WildCRU would be more likely to read the emailed update from WildCRU and notice the survey link at Time 2. Also note that there are small differences in N's and corresponding df 's for analyses because we did not eliminate participants' data if there were missing cells.

We also examined the full Time 1 dataset (N = 992) to see whether the results reported with the N = 160 subset were consistent with each other. We tested the mediation result from Time 1 data involving the dysphoric intensity, fusion to Cecil, and fusion to WildCRU variables. The results were very similar. First, dysphoric intensity predicted fusion to Cecil, standardized regression coefficient, β = 0.27, p < 0.01, and fusion to WildCRU, β = 0.21, p < 0.01. Fusion to Cecil also predicted fusion to WildCRU, β = 0.67, p < 0.01. Then, in a regression with dysphoric intensity and fusion to Cecil entered as simultaneous predictors, the effect of intensity on fusion to WildCRU was in a positive direction but no longer statistically significant, β = 0.03, p = 0.25, while fusion to Cecil remained significant, β = 0.66, p < 0.01, with Sobel z = 8.04, p < 0.01.

In addition, one likely cause of attrition was that, unlike most studies with longitudinal designs, we offered no material incentive to complete the survey. Another likely cause was that the survey was advertised toward the end of a long e-mail primarily focusing on updates regarding Cecil's story and WildCRU conservation efforts, thus many readers may have simply not noticed the survey link. Also, given that the total N for those who completed both waves was 160, well exceeding the required sample size to detect a medium effect size in a multiple regression with up to 10 predictors (at power = 0.8 and p < 0.05), and that there were only minor differences between those who completed only wave 1 and those who completed both waves, we believe that attrition was non-systematic.

Discussion

Overall, our results reveal one possible psychological pathway by which a viral moment can have long-term effects on supporters' identities and behavior. The case of Cecil may seem remarkable in that none of those donating to lion conservation as a consequence were affected personally in any practical or material way by Cecil's death. But this may be true of social movements in human history in general. For instance, many supporters of the civil rights movement in the U.S. or hunger strikes in Northern Ireland or, more recently, efforts to bring about regime change during the Arab Spring, have been motivated to get involved despite being far removed from their seminal events, perhaps even on the other side of the world. Indeed, the Arab Spring and other revolutionary movements have benefitted from diaspora communities in other parts of the world providing crucial diplomatic and financial support (Moss, 2016). If we better understand the psychology involved in generating identity fusion to groups involved in social movements, and in particular the role of unique, dysphoric, transformative experiences in augmenting group cohesion, we can begin to explain the failures and successes of specific moments in history to generate enduring movements, even from a great distance. We can also harness these processes to help solve collective action problems of other kinds, not only in domains like conservation but also closely related global problems such as climate change or antibiotic resistance (Whitehouse, 2014). Conversely, more destructive expressions of the same psychological processes (e.g., foreign fighters who have joined ISIS) may be responded to more effectively if we understand the role of shared dysphoria in motivating extreme pro-group action of all kinds (Whitehouse et al., 2017).

Our investigation of WildCRU donors has been guided by a larger collaboration that aims to leverage behavioral insights from multiple disciplines in order to create and sustain high levels of human cooperation in contexts where it is desperately needed (e.g., wildlife conservation, social and economic conflicts, etc.). Here, we are building on efforts to synthesize two bodies of work, one based on Whitehouse's anthropological studies of the experiential causes of social bonding (Whitehouse, 1996; Whitehouse and Lanman, 2014), and the other based on Swann's social psychological studies of the nature and consequences of identity fusion (Swann et al., 2009; Buhrmester and Swann, 2015). This synthesis is highly interdisciplinary, involving collaborations with mathematical modelers (e.g., Salali et al., 2015; Whitehouse et al., 2017), historians (e.g., Whitehouse et al., 2015), archaeologists (e.g., Gantley et al., 2018), cultural evolution theorists (e.g., Atkinson and Whitehouse, 2011), and developmental psychologists (Watson-Jones et al., 2014; Rybanska et al., 2017)—to name only a few of the disciplines contributing to theory building on this topic. Our present study is the first to apply this emerging theoretical synthesis to work in the domain of human dimensions of wildlife conservation. In doing so, we adapted study measures from instruments that have been previously validated as part of the above synthesis (Swann et al., 2009; Jong et al., 2015). Furthermore, our examination extends the synthesis by focusing on a precipitating event (i.e., Cecil's death) that was centered largely on a wild animal. Past studies have focused on events involving only humans (e.g., the Boston Marathon Bombings, Buhrmester et al., 2015), thus our study's findings add to the generalizability of the psychological processes that we have examined.

Our findings point to the need for continued future research along several avenues. More empirical work is needed to examine the extent to which continued reflection after a precipitating event is caused by aspects of the event itself (i.e., its affective intensity, uniqueness, etc.) vs. communication between group members in the wake of the event. Understanding the impact of continued communication, as well as identifying the key components of fusion-augmenting communication after a precipitating event, could lead to positive practical applications. In addition, future work should examine how perceptions of donation usage may impact both continued giving as well as group bonding. In our case, donors learned from WildCRU's newsletter and website that all donations would be used to achieve the organization's strategic plan, a plan that includes the study of the ecology and conservation of lions such as Cecil but is much broader in scope (see https://www.wildcru.org/about-wildcru/2020-vision). The Cecil case thus shows that many individuals are willing to give (sometimes rather large sums) to broad wildlife conservation efforts based on a single, compelling narrative.

Lastly, can our results facilitate Macdonald et al.'s (2016a) vision of “Cecil Moment” blossoming into a “Cecil Movement”? At the very least, our evidence—that depth of reflection and perception of event centrality underlie increases in fusion over time—should cause conservation advocates to ask how these processes can be amplified to increase fusion amongst supporters (and indeed, to create some level of fusion among initial non-supporters). In addition, advocates and researchers alike should seek out ways to reach the millions who for reasons unknown have not felt swayed by viral moments like Cecil's. Is there a hard cap on the number of conservationist hearts to be won, or could all of humanity rally as one?

Our findings, especially those suggesting that Cecil's story sparked sustained support for WildCRU, give us at least some measure of hope that broad swaths of humanity can and do wish to support not just specific animal rights or wildlife causes, but also broader organizations involved in an array of research and conservation activities with a global focus. And in the case of lions, whose numbers have declined, on average, by 43% over the last three leonine generations (Bauer et al., 2016), greater sustained commitment to their conservation by citizens of the range states and of the wider world, cannot come soon enough.

Data Availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the corresponding author, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with and approved by the School of Anthropology and Museum of Ethnography Research Ethics Committee at the University of Oxford. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

DM and HW contributed equally as joint senior authors. All authors designed the measures. MB collected and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by Oxford Martin School, a Large Grant from the UK's Economic and Social Research Council (REF RES-060-25-467-0085), an Advanced Grant from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement No. 694986), and the Recanati-Kaplan Foundation. See Supplementary Materials for data deposition. We thank Ashle Bailey, Sanaz Talaifar, and Ashwini Ashokkumar for providing feedback on an earlier version of this article.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2018.00054/full#supplementary-material

References

Atkinson, Q. D., and Whitehouse, H. (2011). The cultural morphospace of ritual form; Examining modes of religiosity cross-culturally. Evol. Hum. Behavior. 32, 50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.09.002

Bauer, H., Chapron, G., Nowell, K., Henschel, P., Funston, P., Hunter, L. T., et al (2015). Lion (Panthera leo) populations are declining rapidly across Africa, except in intensively managed areas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 14894–14899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500664112

Bauer, H., Packer, C., Funston, P. F., Henschel, P., and Nowell, K. (2016). Panthera leo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T15951A107265605. Available online at: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/15951/0

Berger, J., and Milkman, K. L. (2012). What makes online content viral?. J. Market. Res. 49, 192–205. doi: 10.1509/jmr.10.0353

Buhrmester, M. D., Fraser, W. T., Lanman, J. A., Whitehouse, H., and Swann, W. B. Jr. (2015). When terror hits home: identity fused Americans who saw Boston bombing victims as family provided aid. Self Ident. 14, 253–270. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2014.992465

Buhrmester, M. D., and Swann, W. B. (2015). “Identity fusion,” in Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource, eds R. A. Scott and S. M. Kosslyn. doi: 10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0172

Di Minin, E., Leader-Williams, N., and Bradshaw, C. (2016). Banning trophy hunting will exacerbate biodiversity loss. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst). 31, 99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.12.006

Gantley, M., Bogaard, A., and Whitehouse, H. (2018). Material Correlates Analysis (MCA): an innovative way of examining questions in archaeology using ethnographic data. Advan. Archaeol. Pract.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach. New York, ny: Guilford.

Jong, J., Whitehouse, H., Kavanagh, C., and Lane, J. (2015). Shared negative experiences lead to identity fusion via personal reflection. PLoS ONE 10:e0145611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145611

Loveridge, A. J., Valeix, M., Chapron, G., Davidson, Z., Mtare, G., and Macdonald, D. W. (2016). Conservation of large predator populations: demographic and spatial responses of African lions to the intensity of trophy hunting. Biol. Conserv. 204, 247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.024

Macdonald, D. W., Jacobsen, K. S., Burnham, D., Johnson, P. J., and Loveridge, A. J. (2016a). Cecil: a moment or a movement? Analysis of media coverage of the death of a lion, Panthera leo. Animals 6:26. doi: 10.3390/ani6050026

Macdonald, D. W., Johnson, P. J., Loveridge, A. J., Burnham, D., and Dickman, A. J. (2016b). Conservation or the moral high ground: Siding with Bentham or Kant. Conserv. Lett. 9, 307–308. doi: 10.1111/conl.12254

Moss, D. M. (2016). Diaspora Mobilization for Western Military Intervention During the Arab Spring. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 14, 277–297. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2016.1177152

Newson, M., Buhrmester, M., and Whitehouse, H. (2016). Explaining lifelong loyalty: the role of identity fusion and self-shaping group events. PLoS ONE 11:e0160427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160427

Rybanska, V., McKay, R., Jong, J., and Whitehouse, H. (2017). Rituals improve children's ability to delay gratification. Child Develop. 89, 349–359. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12762

Salali, G. D., Whitehouse, H., and Hochberg, M. E. (2015). A life-cycle model of human social groups produces a U-shaped distribution in group size. PLoS ONE 10:e0138496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138496

Swann, W. B., Gómez, Á., Buhrmester, M. D., López-Rodríguez, L., Jiménez, J., and Vázquez, A. (2014). Contemplating the ultimate sacrifice: identity fusion channels pro-group affect, cognition, and moral decision making. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 106:713. doi: 10.1037/a0035809

Swann, W. B., Gómez, Á., Seyle, D. C., Morales, J. F., and Huici, C. (2009). Identity fusion: the interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 96:995. doi: 10.1037/a0013668

Swann, W. B., Jetten, J., Gómez, Á., Whitehouse, H., and Bastian, B. (2012). When group membership gets personal: a theory of identity fusion. Psychol. Rev. 119:441. doi: 10.1037/a0028589

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Soc. Psychol. Intergr. Relat. 33:74.

Vázquez, A., Gómez, Á., and Swann, W. B. (2017). Do historic threats to the group diminish identity fusion and its correlates? Self Identity 16, 480–503. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2016.1272485

Watson-Jones, R., Legare, C. H., Whitehouse, H., and Clegg, J. (2014). Task-specific effects of ostracism on imitation of social convention in early childhood. Evol. Hum. Behav. 35, 204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.01.004

Whitehouse, H. (1996). Rites of terror: emotion, metaphor and memory in Melanesian initiation cults. J. R. Anthropol. Instit. 2, 703–715. doi: 10.2307/3034304

Whitehouse, H. (2002). Religious reflexivity and transmissive frequency. Soc. Anthropol. 10, 91–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8676.2002.tb00048.x

Whitehouse, H. (2014). Three wishes for the world (with comment). Cliodyn. J. Theor. Math. Hist. 4, 281–323. Available online at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2wv6r7v3

Whitehouse, H., François, P., and Turchin, P. (2015). Can there be a science of history? Response to commentaries on the role of ritual in the evolution of social complexity: five predictions and a drum roll. Cliodynamics 6, 214–216. doi: 10.21237/C7clio6229624

Whitehouse, H., Jong, J., Buhrmester, M. D., Gómez, Á., Bastian, B., Kavanagh, C. M., et al. (2017). The evolution of extreme cooperation via shared dysphoric experiences. Sci. Reports. 7:44292. doi: 10.1038/srep44292

Whitehouse, H., and Lanman, J. A. (2014). The ties that bind us: ritual, fusion, and identification. Curr. Anthropol. 55, 674–695. doi: 10.1086/678698

Keywords: conservation, activism, groups, identity fusion, prosociality

Citation: Buhrmester MD, Burnham D, Johnson DDP, Curry OS, Macdonald DW and Whitehouse H (2018) How Moments Become Movements: Shared Outrage, Group Cohesion, and the Lion That Went Viral. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6:54. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00054

Received: 24 January 2018; Accepted: 12 April 2018;

Published: 03 May 2018.

Edited by:

Robert A. Montgomery, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mirko Di Febbraro, University of Molise, ItalySpartaco Gippoliti, Società Italiana di Storia della Fauna, Italy

Copyright © 2018 Buhrmester, Burnham, Johnson, Curry, Macdonald and Whitehouse. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael D. Buhrmester, bWljaGFlbC5idWhybWVzdGVyQGFudGhyby5veC5hYy51aw==

Michael D. Buhrmester

Michael D. Buhrmester Dawn Burnham2

Dawn Burnham2 Oliver S. Curry

Oliver S. Curry