Abstract

Natural selection is based on the concept of differential reproduction between entities, often characterized as a struggle between individual organisms. However, natural selection can act at all levels of biological organization, thus being termed “multilevel selection” (MLS). A common misconception is that selection across levels of biological organization lacks empirical support. To address this, we conducted a bibliometric review of 2,950 Web of Science/Scopus-indexed scientific articles, to document the range of taxa and research topics where MLS has been used to understand natural selection across levels. The 280 studies providing empirical support for selection at more than one level spanned a vast range of organisms, from viruses to humans to eusocial insects. They included research done both in natural populations (100) and in laboratory experiments (180). While 90.4% of studies focused on selection among organismal groups (e.g., demes, colonies, aggregates), another 9.6% explored selection across other levels (genetic elements, nuclei, cells, or multispecies communities). We classified studies by topic including artificial selection, breeding through group selection, indirect genetic effects, and contextual analysis, among others. Contrary to common notions, we found solid empirical support for the utility and importance of MLS in explaining natural selection and evolution.

1 Introduction

Multilevel selection (MLS) occurs when natural selection simultaneously acts at two or more levels of biological organization (Damuth and Heisler, 1988; Okasha, 2006; Wilson and Wilson, 2007; Marín, 2024). Specifically, MLS occurs when there is differential reproduction of groups in addition to reproduction of individual entities within them, or when the differential reproduction of individuals is based on their group composition or characteristics, e.g., the social environment (Goodnight et al., 1992) (see key definitions in Table 1). Goodnight et al. (1992) have defined MLS as: “variation in the fitness of individuals that is due to both properties of the individuals and properties of the group or groups of which they are members” (p. 745). Goodnight et al. (1992) definition incorporates models that explicitly include differential extinction of entire groups (Levins, 1970), trait-group models (Wilson, 1975), and Wright’s (1945) definition of interdemic selection, which does not require group extinction.

Table 1

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Artificial selection | Human goal-driven selective breeding. Humans breed whole communities (like microbiomes) or species consortia or aggregates (like yeast aggregates) for specific desired traits (like bigger colony size, for yeasts), under imposed environmental conditions. |

| Breeding through group selection | Artificial selection where humans control the context for reproduction in such a way as to influence how groups of organisms function (e.g., reduced competition). Typically, these studies have two contrasting breeding treatments: individual-based breeding (classical way to breed animals or crops) and group-based breeding. “Group-based breeding” means that emergent or contextual or group-level traits are the basis for the breeding program. |

| Contextual analysis | Contextual analysis follows the methods for analyzing phenotypic selection originally developed by Lande and Arnold (1983) and Arnold and Wade (1984), where a multiple regression of relative fitness on phenotype is performed (Goodnight et al., 1992). Contextual analysis extends such methods by including “contextual” or “emergent” traits, that is, traits measured on the group or neighborhood, in the multiple regression. In this way, relative fitness is a function of individual and group or emergent traits. This phenotypic selection tool allows to disentangle the strength and direction of selection operating at the individual and group levels. Goodnight et al. (1992) has shown that contextual analysis is an useful tool, compatible with models that explicitly include differential extinction of entire groups (Levins, 1970), Wright’s definition of interdemic selection – which does not require group extinction (Wright, 1945) – and trait-group models (Wilson, 1975). |

| Cultural multilevel selection | Multilevel selection (MLS) in which the inheritance system is cultural transmission, not genetic material. These studies investigated MLS in cultural traits, thus, for example these studies showed traits that confer a group-level advantage can spread via cultural MLS. |

| Indirect genetic effects (IGEs) | An IGE has been defined as the “effect of a gene in the genome of one individual on the phenotype of another individual” (Wade, 2026). IGEs sometimes are also deemed as “social genetic effects”. A recent meta-analysis on this subject was recently published by Santostefano et al (Santostefano et al., 2025). Bijma and Wade (2008) have shown that when IGEs are included when calculating the response to selection, MLS without relatedness can explain the evolution of social traits. |

| Multilevel selection | MLS has been defined as a situation in which natural selection occurs among entities at two or more different levels in a nested biological hierarchy (Damuth and Heisler, 1988). Specifically, MLS occurs when there is differential reproduction of entire groups (as well as of individual entities within them), or when the differential reproduction of individuals is based on their group composition or characteristics. |

| Trait groups | Trait groups (Wilson, 1975) are fitness-affecting associations between two or more individuals, regardless of the duration of the association or whether actual reproduction takes place. Selection is then acting on both individuals within groups and the groups or demes themselves. |

Glossary of terms.

The MLS framework has been useful, even essential in studying the central dogma in molecular biology (Takeuchi and Kaneko, 2019), horizontal gene transfer in bacteria (Lee et al., 2022), the origin of multicellularity (Bozdag et al., 2023), cancer (Aktipis et al., 2015), disease/virus evolution (Blackstone et al., 2020), animal (Craig and Muir, 1996) and plant breeding (Zhu et al., 2019b), as well as economics (Wilson et al., 2020) and cultural institutions (Wilson et al., 2023). The clear value of an MLS approach, whether related to the selection of particular traits, or to the discovery of what affects fitness in a given system/organism, is its focus on identifying both the direction and strength of selection from multiple sources. Despite this, criticisms and skepticism persist among biologists (Eldakar and Wilson, 2011) – albeit anthropologists seem to favor an MLS framework, according to a survey by Yaworsky et al. (2015). Marı́n (2024) has identified three main arguments in favor of MLS: first, the term “unit of selection” has a polysemic nature, with at least three different meanings: “interactors”, “replicators or reproducers or reconstitutors”, and “manifestors of accumulated adaptations” (Suárez and Lloyd, 2023; Lloyd, 2024). The second is the fact that biological entities as complex as organisms or genes must-at least- have evolved from less complex entities (Okasha, 2006). And third, there is vast empirical evidence for this theory both in laboratory and natural populations. Sound literature reviews of such empirical evidence of MLS can be found in: Wilson and Sober (1994), Goodnight and Stevens (1997), Eldakar and Wilson (2011), Goodnight (2015), Marín (2015, 2016, 2024), and Hertler et al. (2020). Despite these clear reviews and a diversity of empirical studies across a range of taxa, the misconception that MLS lacks empirical support persists (Harms et al., 2023). Here we address this misconception head on, by revealing an abundance (not a paucity) of examples of MLS in a diversity of taxa and biological systems, levels of biological organization, and type of research topics and tools.

In evolutionary biology, the evolution of altruism or prosociality has been a main focus of MLS debates for decades, but altruism is just one trait that can evolve via MLS. On the one hand, the classic example of the evolution of altruism considers groups within which selfish individuals out-compete altruists, while groups with more altruists contribute more offspring to the next generation than groups comprised of more selfish individuals (Darwin, 1871; Wilson and Wilson, 2007). On the other hand, MLS also occurs when emergent group traits (e.g., social network structure, density, collective colony personality, among other descriptors) have significant effects on the reproductive success of a focal individual (Damuth and Heisler, 1988; Goodnight et al., 1992; Philson et al., 2025). Such effects of emergent or contextual traits have been amply demonstrated, for example in studies of epistasis (Burch et al., 2024) and indirect genetic effects (IGEs) (Linksvayer et al., 2009; Buttery et al., 2010; Bijma, 2014; Baud et al., 2021; Santostefano et al., 2025), and using techniques such as contextual analysis (Marín, 2016; Suárez and Lloyd, 2023; Lloyd, 2024; Philson et al., 2025).

We conducted a bibliometric review of the scientific literature to identify the breadth and depth of empirical evidence of MLS across levels of biological organization. In addition, we also focused on phenotypic selection studies that use contextual analysis (Heisler and Damuth, 1987) to decompose the strength and direction of selection at different levels (individual organisms and groups of organisms). We then organized the literature on the basis of study systems (i.e., eusocial insects, humans, wild plants and algae, crops, etc.), levels of biological organization assessed (demes, communities, cells, etc.), and type of research (i.e. in situ studies of natural populations, artificial selection experiments, breeding through group selection, etc.). The focus of this review is to provide an introduction, accounting, and organization of the vast empirical support of MLS and its utility to understand the natural world. In this review, “support” means only that selection at different levels was explicitly measured, not that higher levels or “group” selection outweighed lower levels. For example, there were some studies in which lower-level selection or individual properties were shown to be more important than higher-level selection or properties in explaining focal individual fitness (Tsuji, 1995; Donohue, 2003; Fisher et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2021). Thus, our bibliometric review captured the full spectrum of studies, whether or not individual or higher-level selection is the prevailing force – something perfectly consistent with MLS theory, as MLS should be evaluated in a case-by-case basis (Wilson and Wilson, 2007). In addition, while discussions of alternative and complementary frameworks (such as inclusive fitness theory or direct reciprocity) and mechanisms that partition variation within and between groups (e.g., conditional dispersal, kinship, and kin groups) are of general interest (for detailed discussions, see Bijma and Wade, 2008; Goodnight, 2013; Frank, 2025; Marín and Wade, 2025), the consideration of such topics are beyond the scope of this review. However, in Appendix 1 we discuss why MLS is not mathematically equivalent to other frameworks such as inclusive fitness theory.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bibliometric analysis: search terms

The current review is classified as a “bibliometric” analysis and not as a “meta-analysis” because, with the exception of the regression coefficients of 21 studies involving contextual analysis, no actual data was extracted from the articles. Rather, this review aimed at compiling the empirical evidence for MLS in situ and in laboratory experiments by conducting a bibliometric analysis following the “Preliminary guideline for reporting bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO)” (Montazeri et al., 2023). Please find in Appendix 2 the BIBLIO complete check-list required in such preliminary guideline.

In January 2025, the following terms were searched in the Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/home.uri) database: “multilevel selection” across the whole article, and “group selection” in the Title, Abstract, and Keywords – because the latter was the term most commonly used before Damuth and Heisler (1988). The search spanned 1900–2024 and included articles and reviews only published in English, in journals indexed both in Web of Science and Scopus. In Scopus, the following areas were excluded from the search: dentistry; nursing; energy; chemical engineering; health professions; pharmacology, toxicology and pharmaceutics; business, management, and accounting; materials science; physics and astronomy; engineering; computer science; arts and humanities; mathematics; and medicine. All the remaining areas were included in the search. We also conducted an additional search in Google Scholar, with the same terms as in the Scopus search, to capture Web of Science/Scopus-indexed MLS empirical papers not discovered by the Scopus search due to differences in both search engines.

2.2 Bibliometric analysis: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion criteria

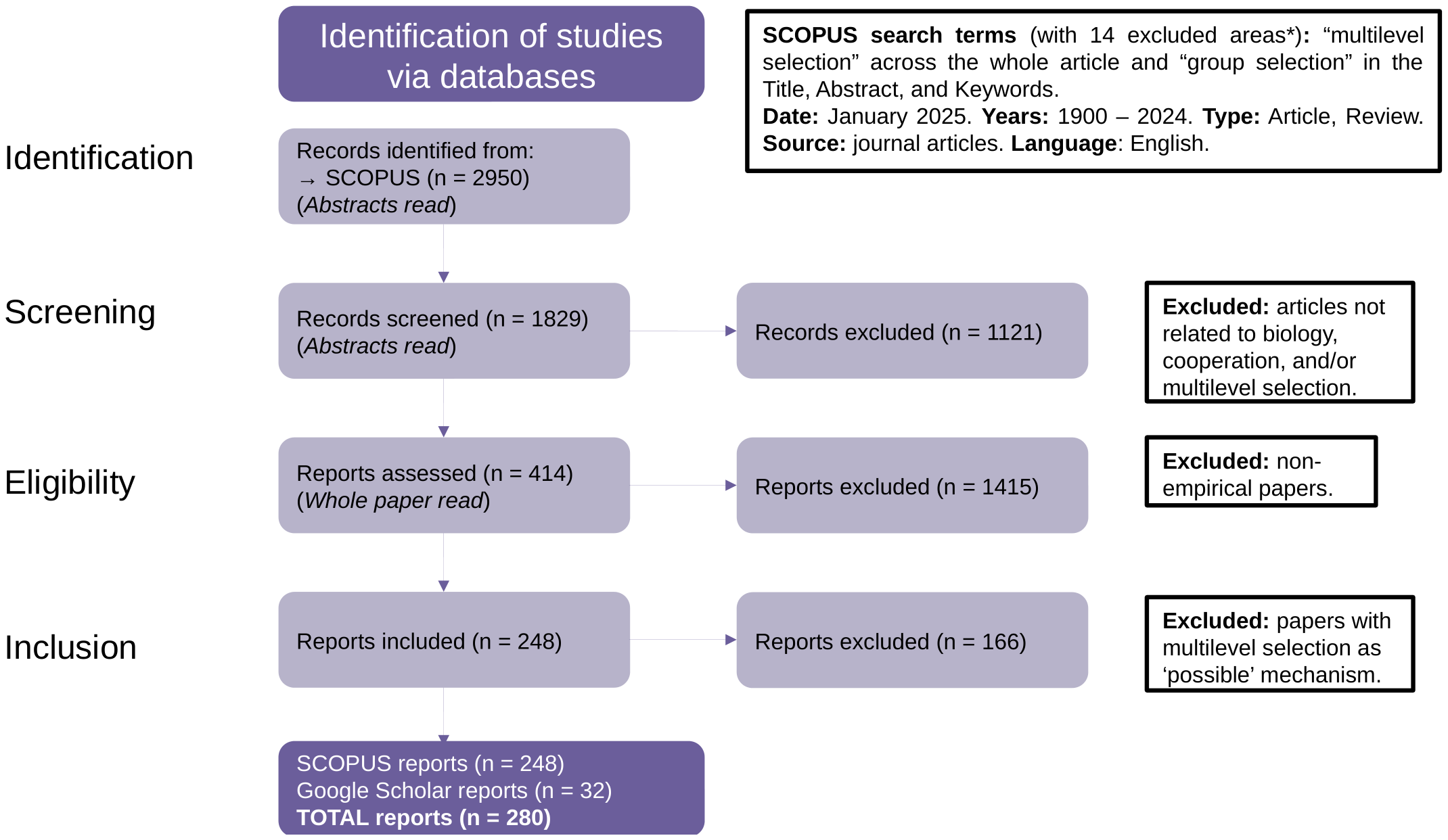

The bibliometric analysis had a total of four phases: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion (Figure 1). In the identification phase, all duplicates were deleted, and in the screening phase, based on information contained within the abstracts, all articles not related to biology, cooperation, and social behavior in general, were excluded. For the eligibility phase, all non-empirical studies were excluded, again based on the content within the abstracts. These non-empirical studies included mathematical models, reviews, discussions, response articles, conceptual models, and opinion articles, among others. In the inclusion phase, the articles were read in their totality, and those articles indicating MLS or group selection as “possible” or “plausible” (but not surely) mechanism explaining the observed results or patterns, were also excluded. For example, among the articles excluded on this third phase is an article entitled: “Sex-ratio bias and possible group selection in the social spider Anelosimus eximius” published in The American Naturalist (Aviles, 1986), because the author indicates that group selection might be the mechanism explaining her results but further research is needed. All articles employing the same type of argumentation or reasoning were also excluded.

Figure 1

BIBLIO flow diagram for bibliometric review of empirical studies of multilevel selection.

2.3 Bibliometric analysis: classification

After the inclusion phase, articles were classified according to the type of study (in situ or laboratory experiments); taxon or study system (fungi, farm animals, eusocial insects, humans, microbiomes, etc.); the level of biological organization that was the main focus of research (groups or demes of organisms, communities, colonies, nuclei, aggregates, selfish genetic elements, etc.); and the main topic (or sub-topic) or method to assess MLS in situ or in the lab. For the latter, we identified a total of 9 topic categories and 70 sub-categories of MLS empirical research (Supplementary Table S1 in Appendix 2). A general overview and specific details, as well as information about the exclusion/inclusion criteria of each category and sub-category, can be found in Appendix 2. The full list of MLS empirical articles, after the inclusion (third) phase, can be found in Appendix 3.

The MLS in situ studies included five categories (a more detailed description can be found in Appendix 2), as follows:

-

Cultural multilevel selection: those that investigated MLS in the spread of cultural traits, and, for example, demonstrated that traits conferring a group-level advantage can spread via cultural group selection.

-

Dataset analyses: these studies analyzed historical or published data to infer MLS processes occurring in natural populations or communities. A subset of these studies implemented different sorts of molecular sequencing to natural populations, using different tools, from single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis to genome-wide association studies. Another subset implemented phylogenetic analyses either to assess selection at the species level or to explain the evolution of complexity/multicellularity across phylogenetic trees.

-

Indirect Genetic Effects (IGE): an IGE has been defined as the “effect of a gene in the genome of one individual on the phenotype of another individual” (Wade, 2026). IGE studies collect population and trait and/or loci data to assess the effects of interacting partners on a focal individual traits’ and/or reproduction.

-

Group effects: these studies assessed the effects of group emergent properties (like networks of interactions or group structure) on focal individuals’ trait variation and/or individual fitness. A subset of these studies assessed group heritability, which has been defined as the “tendency of offspring groups to resemble their parental groups with respect to group-level traits” (Okasha, 2003). Another subset detected colony-level selection, by directly measuring phenotypic variation at the whole-colony level, in eusocial insects. Another subset still assessed group effects on focal individuals’ phenotypic variation and/or fitness under field conditions.

-

Contextual analysis: contextual analysis extends the commonly used methods to measure natural selection in natural populations (Lande and Arnold, 1983; Arnold and Wade, 1984) by including “contextual” or “emergent” traits, that is, traits measured on the group or neighborhood, in a multiple regression. In this way, relative fitness is a function of individual and group or emergent traits.

The MLS experimental studies included four categories (a more detailed description can be found in Appendix 2), as follows:

-

Lab experiments: some lab experiments imposed group and individual selection regimes and compared responses to selection afterwards, some measured the molecular consequences of such treatments, others measured group effects on focal individuals’ fitness, microbial culture treatments, and measurements of different aspects of colony-level selection (trait variation, fitness, among others). A subset of these studies consisted of controlled experiments done to assess how IGEs affect focal individuals phenotypic variation and/or fitness.

-

Breeding through group selection: typically, these studies have two contrasting breeding treatments: individual-based breeding (classical way to breed animals or crops) and group-based breeding, measuring the individual and group phenotypic effects and productivity of both treatments after several generations. A subset of these studies were breeding programs that incorporated the calculation and effects of IGEs.

-

Psychology experiment: these were psychological experiments following and aimed to assess a cultural multilevel selection framework (Wilson et al., 2023).

-

Artificial selection: in these studies, researchers selected whole communities (like microbiomes) or species consortia or aggregates (like yeast aggregates) for specific desired traits (like bigger colony size for yeasts), under specific environmental conditions. For example, studies implementing artificial selection for multicellularity in yeasts (Ratcliff et al., 2012; Bozdag et al., 2023) match this category.

These nine categories were created by organizing all qualifying MLS empirical papers by similarity and/or main topic and/or main method assessed. The 70 sub-categories are mostly related to specific taxa or study systems, techniques, or sub-topic (Appendix 2).

2.4 Contextual analysis studies

Lastly, with the specific goal of comparing the strength and direction of natural selection as measured across different levels of biological organization, we conducted a detailed analysis of the 25 phenotypic selection studies that explicitly measured selection at multiple levels of biological organization (individual organisms and demes). A recently published article implementing contextual analysis in wild mammal populations was added to this analysis (Philson et al., 2025), totaling 26 studies. Specifically, we extracted the available beta regression coefficients of each study, as these coefficients depict the direction and strength of selection on the trait in question at individual and group levels. The complete dataset of these coefficients is found in the Supplementary Table S3 of Appendix 2.

3 Results

The identification phase of the Scopus search yielded a total of 2,950 articles (after deleting duplicates) (Figure 1). A total of 1,829 papers remained after exclusion of all articles not related to biology, cooperation, and social behavior in general (screening phase). From these, only 414 papers included empirical studies and thus persisted in the eligibility phase (Figure 1). Finally, 166 articles indicating group selection or MLS as possible or plausible mechanism but not ensuring it as an explanation, were also excluded, resulting in a total of 248 papers providing empirical support for MLS found with Scopus. The additional search with Google Scholar, which was restricted to Web of Science and Scopus-indexed articles, added 32 articles to this list, leading to a total of 280 scientific articles providing empirical support for MLS (Figure 1).

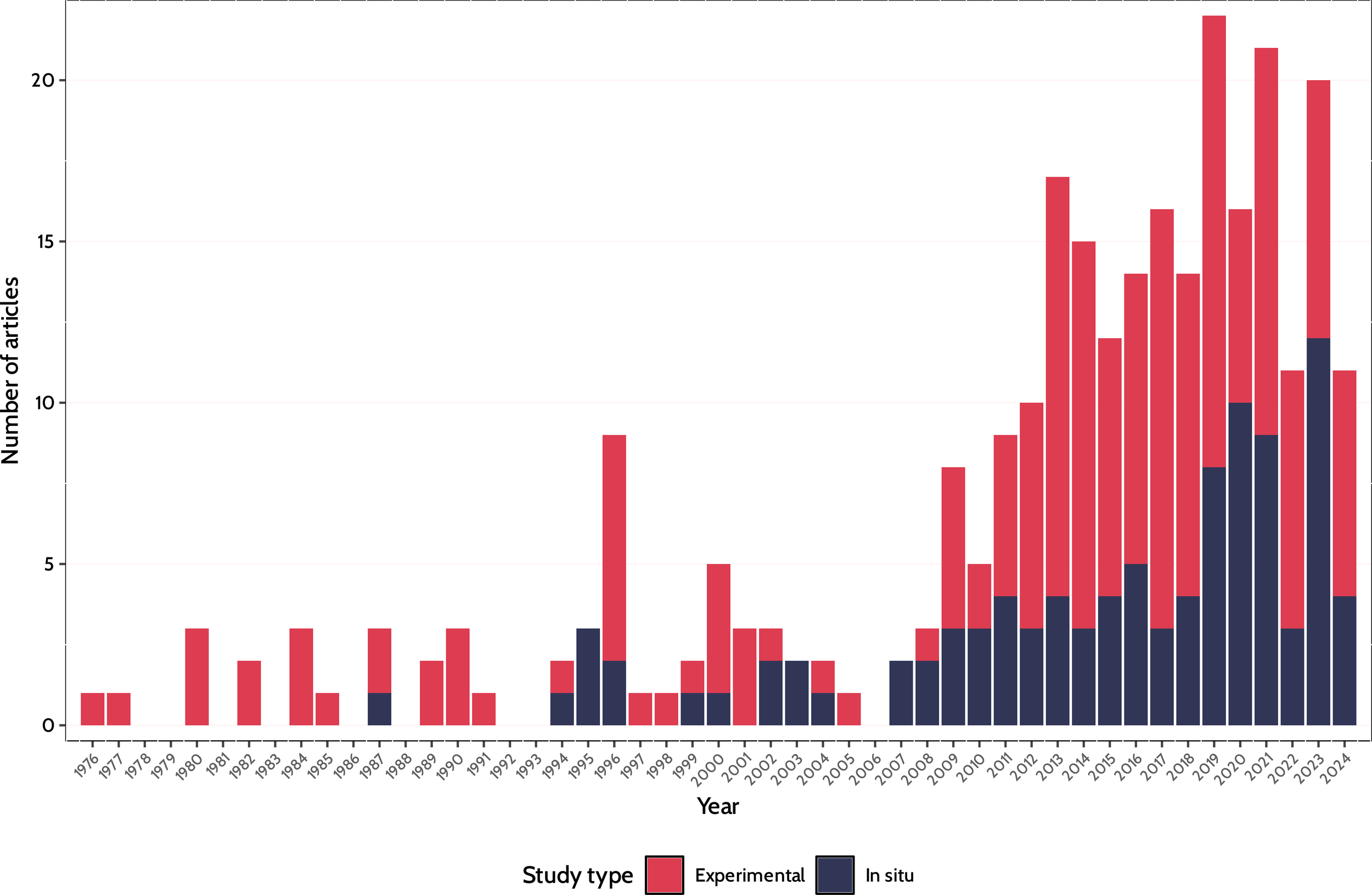

These articles spanned 1976–2024, and 180 consisted of laboratory-controlled experiments, while the remaining 100 consisted of in situ (field) measurements and/or experiments (Figure 2). Only years 2019, 2021, and 2023, yielded 20 or more MLS empirical papers, with a peak of 22 studies in 2019 (Figure 2). Only 81 studies were published during the first 35 years of MLS empirical research (1976–2011), while the remaining 199 have been published since 2012, showing a marked increase in research in the last 12 years, both on MLS in situ and experimental studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Number of Web of Science/Scopus-indexed articles (n=280) published between 1976 and 2024 providing empirical support for multilevel selection in situ (n=100; blue) and through Experimental studies (n=180; red).

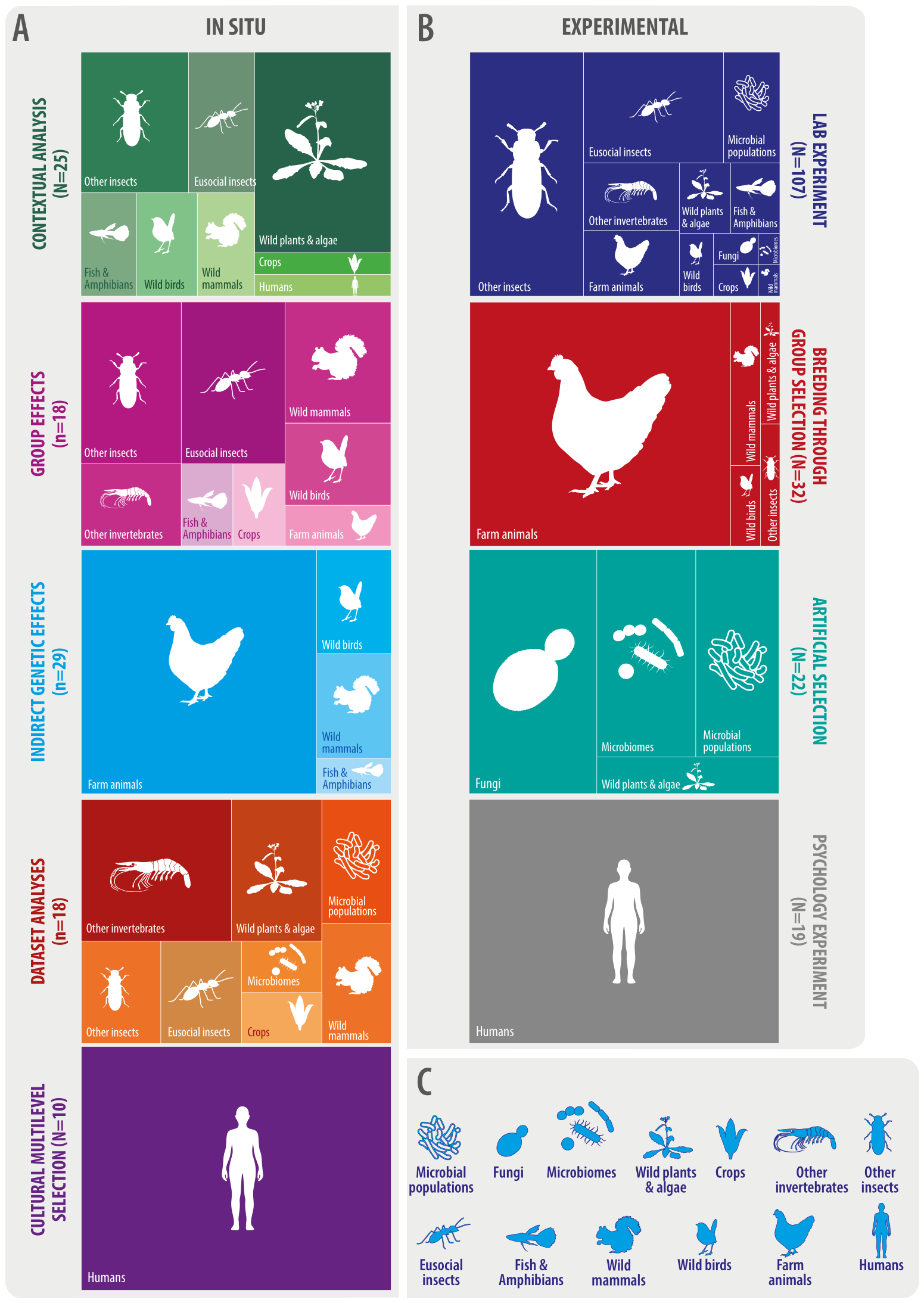

Regarding the taxa or study systems, systems like farm animals, eusocial insects, “other insects” (this means non-eusocial insects such as beetles, spiders, water striders, among others), and humans, together compose approximately 65% and 55% of experimental and MLS in situ studies, respectively (Figure 3). However, in MLS in situ studies, systems like wild plants and algae, wild mammals, and wild birds also make up an important proportion of studies, while this is the case for microbial populations and fungi in MLS experimental studies (Figure 3). Many other study systems or taxa have been empirically investigated under a MLS framework: other invertebrates (such as tunicates and polychaetes), crops, algae, fish and amphibians, microbiomes, etc. (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Distribution of 280 studies providing empirical support for multilevel selection across study systems and types. (A)In situ studies. (B) Experimental studies. (C) Study systems.

Regarding the levels of biological organization investigated, 90.4% of MLS empirical studies focused on individual organisms and groups of organisms. In particular, 71% of studies (198 papers) focused on demes, while 19.4% of studies focused on tighter organismal groups: 24 studies were conducted at the “aggregate” level (aggregates of bacteria, amoebas, algae, and yeast) and 31 studies investigated colony-level selection (mostly in eusocial insects but also including spider and Caenorhabditis elegans colony studies). A 9.6% of MLS empirical studies focused on organization levels above or below organisms/groups of organisms: four studies were conducted at the cell level (this include horizontal gene transfer or RNA viruses, for example); three studies were conducted at the genetic element level (specifically investigating selfish genetic elements or gene transfer agents using an MLS framework); 13 studies investigated community-level selection (mostly microbiomes, but also including beetles, ants, and arthropod communities); three studies with either algae or sea-grass investigated clonal or module-level selection, i.e. selection acting at the clonal level; two studies with fungi investigated natural selection at the nuclei level, as some fungal taxa can contain thousands of nuclei on a single spore (Jany and Pawlowska, 2010); and finally, two studies investigated natural selection at the species level.

Both in situ and experimental MLS empirical evidence comes from many different sources, types of study, and taxa or study systems, to the point that our nine main categories were sub-categorized into 70 sub-categories (Figure 3; Appendix 2). More than half (n=54) of MLS in situ studies used either IGEs measurements or contextual analysis, with categories such as group effects (n=18) and dataset analyses (n=18) also having important numbers (Figure 3). Similarly, 107 of the 180 MLS experimental studies were laboratory experiments of different types, with the group selection treatments on wild animals sub-category in particular having 18 studies (Appendix 2). Other MLS experimental studies categories also had an important number of articles, including breeding through group selection (n=32), artificial selection (n=22), and psychology experiment (n=19) (Figure 3). A brief summary of nine representative studies of each one of the main categories is given in Table 2 for MLS in situ studies and in Table 3 for MLS experimental studies.

Table 2

| Study type and reference | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Cultural multilevel selection (Turchin and Gavrilets, 2021) | Using a database of past societies history (Seshat: Global History Databank), the authors found that the tempo (rates of change) of cultural macroevolution is characterized by periods of apparent stasis interspersed by rapid change. They found that the most important macroevolutionary patterns include competition and warfare but also cultural exchange and selective imitation, fully in accordance with cultural multilevel selection theory. |

| 2. Dataset analyses (Herron and Michod, 2008) | This study investigated the transition from unicellular to multicellular life in Volvocine algae. Phylogenetic reconstructions of ancestral character states were derived from the diverse array of extant species in the volvocine lineage ranging from unicellular to colonial forms that themselves vary in size, structure, and degree of cellular specialization. Herron and Michod (2008) describe an evolutionary history with multiple independent origins and reversals of traits that underlie cellular cooperation (i.e., transition of fitness from individual cells to the group level) as well as conflict-mediation mechanisms to curtail the exploitation of cooperation. |

| 3. Indirect Genetic Effects (IGE) (Santostefano et al., 2021) | The authors assessed how IGEs contributed to genetic variation of behavioral, morphological, and life-history traits in a wild Eastern chipmunk population, comparing the contribution of direct and indirect genetic effects to trait evolvability. They found significant IGEs for trappability and relative fecundity, but little direct genetic effects in all traits measured. |

| 4. Group effects (Robinson et al., 2023) | The ant Rhytidoponera metallica forms queen-less colonies, with such a low intra-colony relatedness that they are proposed as a transient, unstable form of eusociality. Despite this, these ants are among the most widespread in Australia, showing that relatedness is not necessary for such success. The authors show that these ants exhibits remarkable intra-colony variation regarding their polypeptidic venom composition (revealed by transcriptomic and mass spectrometry), with workers sharing only a relatively small proportion of toxins in their venoms. Such variation is not due to the presence of chemical castes, but is rather explained by toxin allelic diversity. The authors conclude that such high toxin diversity is explained through MLS, selecting for colonies that can exploit more resources and defend against a wider range of predators. |

| 5. Contextual analysis (Stevens et al., 1995) | This constitutes the first study to implement contextual analysis (Heisler and Damuth, 1987) in natural populations. This study partitioned selection into group and individual level components in natural populations of Impatiens capensis, measuring the relationships between three fitness components and several group and individual level traits. Two of the fitness components (survival rate and cleistogamous seed production) were affected by individual and group selection, while chasmogamous seed production (the third fitness component) was only affected by individual selection. |

Representative studies of multilevel selection (MLS) in situ studies.

Table 3

| Study type and reference | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Lab experiment (Wade, 1976) | First empirical study of MLS in our bibliometric search. Wade (1976) imposed group selection for both increased and decreased adult population size in laboratory populations of the beetle Tribolium castaneum, at 37-day intervals. Individual selection control treatments (i.e. no group selection imposed) were included. Response to the group selection treatments occurred fast, at three or four generations, and in general was large in magnitude (sometimes 200% larger magnitude than the control). |

| 2. Psychology experiment (Francois et al., 2018) | This study provides evidence both from survey data and laboratory treatments of experimental subjects, consistent with a set of core concepts and theories based on cultural MLS. Specifically, the authors find that “increases in competition increase trust levels of individuals who (i) work in firms facing more competition, (ii) live in states where competition increases, (iii) move to more competitive industries, and (iv) are placed into groups facing higher competition in a laboratory experiment”. They conclude that their findings provide support for cultural MLS as a contributor to human prosociality. |

| 3. Breeding through group selection (Craig and Muir, 1996) | An important behavioral problem with egg laying hens is their proclivity to aggressively peck their cage-mates. This can be minimized through the practice of beak-trimming; however, this can cause lasting pain for the animals involved, thus essentially improving one scenario of animal well-being at the cost of another. Craig and Muir (1996) investigated whether beneficial behaviors could be selected for at the group-level, thereby eliminating the need for beak-trimming. Three genetic stocks of hens were compared for mortality, injuries, and body condition: one of the lines involved the seventh-generation of group-selected hens (recurrent selection of the most productive cages), an unselected stock of hens, and a highly productive, typically beak-trimmed commercial stock. Overall, the group-selected lineage showed behavioral improvements over the unselected and commercial lines resulting in reduced cannibalism, better feathering, and improved welfare. Furthermore, when comparing the previous six generations of the group-selected line of collectively house hens to those housed individually (Craig and Muir, 1996), by the sixth-generation the collectively housed hens approximated the mortality of their solitary counterparts (8.8% to 9.1%, respectively). This was the result of a dramatic decrease in mortality from 68% in the second generation down to 8.8% in the sixth-generation of group-selected hens. In addition, the group-selected lineage also experienced substantial improvements in survival (from 169 to 348 days) and egg production per hen (from 91 to 237 eggs) over that same time frame. |

| 4. Artificial selection (Bozdag et al., 2023) | This multicellularity long-term evolution experiment was carried out with snowflake yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), by selecting for larger group size under three metabolic treatments: anaerobic, obligately aerobic, and mixotrophic yeast. After 600 rounds of selection, yeast in the anaerobic treatment group evolved to be macroscopic, becoming around 2 × 104 times larger (about 1 mm, visible to the naked eye) and about 104-fold more biophysically tough, while retaining a clonal multicellular life cycle. Yeast in the aerobic treatment remained microscopic (only sixfold larger). This was explained through biophysical adaptation of increasingly elongate cells, which after some time facilitated branch entanglements that enabled groups of cells to stay together. |

Representative studies of multilevel selection (MLS) experimental studies.

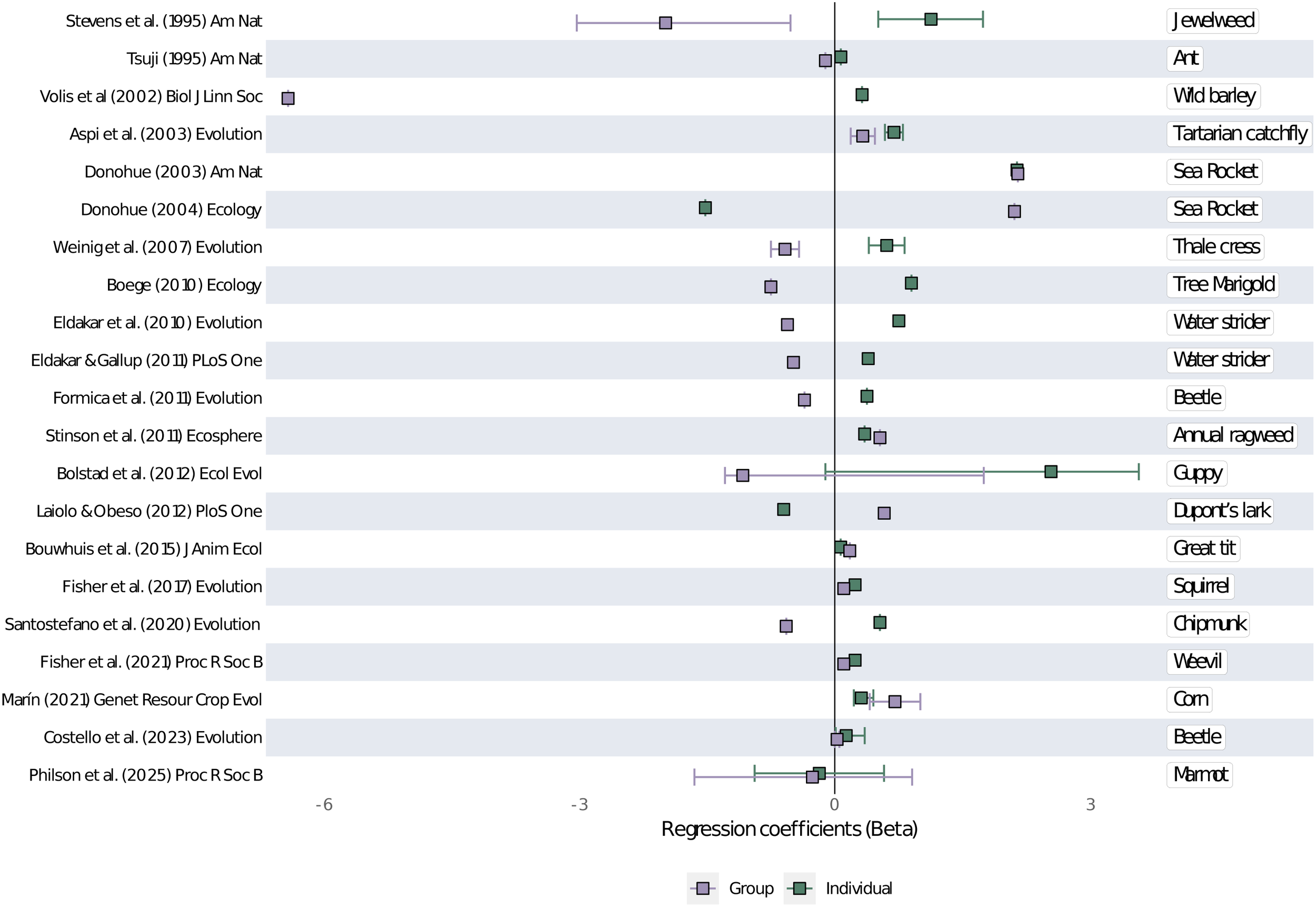

Finally, regarding the 26 studies that implemented contextual analysis in natural populations, it was not possible to extract the regression coefficient information from five of them (Appendix 2; Appendix 3). Thus, Figure 4 shows the regression coefficients from 21 studies spanning 1995–2025, which were conducted in a plethora of study systems: from plants and water striders to chipmunks and humans. In Figure 4, the effects of individual (“size”) and group (average “size” of the neighborhood individuals) traits on focal individuals’ fitness is shown with the Beta (β) regression coefficients. In some studies (Stevens et al., 1995), group selection is stronger and goes in an opposite direction than individual selection, while in other studies (Donohue, 2004) the strength and direction of individual and group selection are similar, and in other studies (Bolstad et al., 2012), individual selection is significantly stronger than group selection (Figure 4). In summary, there is a variety of selection outcomes across the 21 studies as revealed by contextual analysis, with some showing selection at different levels acting in concert while others show selection acting in opposition (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Summary of 21 (out of 26) contextual analysis of phenotypic selection done between 1995 and 2025. Beta regression coefficients show the effects of organismal “size” (or traits which are a proxy of size, like height) at the individual (green squares) and group (purple squares) levels, on individual fitness (or fitness proxies). References cited: Stevens et al. (1995), Tsuji (1995), Volis et al. (2002), Aspi et al. (2003), Donohue (2003, 2004), Weinig et al. (2007), Boege (2010), Eldakar et al. (2010), Eldakar and Gallup (2011), Formica et al. (2011), Stinson et al. (2011), Bolstad et al. (2012), Laiolo and Obeso (2012), Bouwhuis et al. (2015), Fisher et al. (2017), Santostefano et al. (2020), Fisher et al. (2021), Marí́n (2021), Costello et al. (2023), and Philson et al. (2025).

4 Discussion

In this review, we catalogued a vast body of empirical evidence for multilevel selection (MLS), from in situ observations to experimental studies, spanning five decades. Such evidence encompasses a broad spectrum of study systems and taxa, albeit systems like farm animals, eusocial and non-eusocial insects, and humans have been the main focus of MLS research. Similarly, and likely due to the organismal focus of most biologists, but also due to methodological feasibility, individual organisms and groups of organisms (demes, colonies, aggregates) have been the most investigated levels of selection in the MLS empirical research literature. With our analysis we can conclude that there is not a single or majority way to investigate MLS in situ or experimentally. Rather, multiple tools or ways of empirically investigating MLS have been used through the decades, which respond to the specificity of each study system or taxa, level of organization, topic, and/or tool. Further, our bibliometric screening shows that from 1,829 articles that deal in some way with MLS or social evolution, 1,415 articles (77%) consisted of mathematical and conceptual models (Figure 1), opinion pieces, debates, reviews, simulations, and so on. These are important in their own right but are excluded here because we are concerned with the realized utility of the MLS framework in empirical research. Group selection was initially rejected, not due to lack of evidence, but due to its supposed theoretically implausibility (Maynard Smith, 1964; Williams, 1966). The large number of models demonstrating the theoretical plausibility of MLS therefore complements our review of the empirical literature.

The debate on the units of selection has gone on for too long. It is high time to move on and focus on the empirical evidence and data (Marín, 2015; Marín, 2016; Marín, 2024). Because there is a plurality of levels of selection investigated, from selfish genetic elements and nuclei to microbiomes, not all tools or experiments will work the same. For example, it would be quite challenging to apply contextual analysis in artificial selection experiments dealing with multicellularity evolution. Following our comprehensive MLS definition (Table 1), here we focused on compiling an extensive list of studies showing either differential reproduction of entire groups, or the differential reproduction of individuals being affected by their group composition or characteristics.

The plurality of study types and systems involves a variety of different methods to assess MLS in situ. For example, some in situ studies infer MLS by using molecular sequencing tools such as microsatellites, fingerprinting, and genome-wide association studies, among other tools. More than half of MLS in situ studies implemented either IGE assessment or contextual analysis (Figure 3), finding quite significant effects of the neighborhood traits or emergent traits on focal individuals’ fitness (and individual trait variation). Such neighborhood/emergent effects are a core feature of MLS (Table 1), with IGEs, contextual analysis, and group effects measurements, representing different ways in which they are calculated. It is not within the scope of this article to compare such mechanisms of assessment, as this has been done plenty in the literature (Bijma and Wade, 2008; Goodnight, 2013). In particular, Bijma and Wade (2008) have shown the relationships between kin selection (inclusive fitness theory), MLS, and IGEs. In Appendix 1 you can find an expanded Discussion on these relationships and on the non-equivalence between MLS and inclusive fitness theory. Rather, here we show that when group composition or characteristics or average/emergent traits are considered in the response to selection models’ (in addition to individual traits), focal individuals’ fitness are affected by such group composition or characteristics. This is supported by recent meta-analyses by Santostefano et al. (2025) and Burch et al. (2024), which respectively showed that IGE and epistasis are ubiquitous across the Tree of Life.

The comprehensive definition of MLS that we employ here (Table 1) falls into the disambiguating project of the units of selection literature (Suárez and Lloyd, 2023). In the disambiguating project (Suárez and Lloyd, 2023; Lloyd, 2024), the “units of selection” at any given level in the biological hierarchy can have one or more of three functional roles in the process of natural selection, which must be distinguished from each other. These roles are: interactors (phenotypic variation and differential proliferation), replicators (or reproducers or reconstitutors; inheritance), and manifestation of accumulated adaptations (Suárez and Lloyd, 2023). Thus, for a biological entity to be considered an interactor, two minimal things are required: phenotypic variation and differential proliferation. Furthermore, Suárez and Lloyd (2023, p. 17) have defined natural selection as a “process in which the differential proliferation of interactors causes the differential replication of replicators” [or the differential reproduction of reproducers or the differential reconstitution of reconstitutors]. This clarification is necessary, as many of the historical (Williams, 1966) and current-day (Harms et al., 2023) critiques of MLS confound the roles of the different units of selection (Gould and Lloyd, 1999), requiring phenotypic variation, differential proliferation, and inheritance at the same level of biological organization to be considered as a unit of selection. This is not necessarily the case. For example, although typically genes constitute replicators, in specific cases such as selfish genetic elements, genes might also be considered as interactors (Gitschlag et al., 2020).

The comprehensive definition of MLS (Table 1) employed here captures instances in which entire groups constitute the inheritance unit (replicator/reproducer/reconstitutor) and instances in which entire groups constitute the interactor but inheritance occurs at a lower level of biological organization (most typically, the individual organism or its genetic material). The latter cases are typically detectable with techniques such as IGE measurements, social network analysis, the Price equation, and contextual analysis, among others (Marín and Wade, 2025), as mentioned above. In summary, MLS occurs when natural selection operates simultaneously among two or more different levels of a nested biological hierarchy, which either causes differential reproduction of entire groups (i.e., the group is also the replicator/reproducer/reconstitutor) or when the differential reproduction of individuals is influenced by their group composition or its characteristics (i.e., lower-level entities are the replicator/reproducer/reconstitutor).

The pioneering study by Wade (1976) (Table 3) was the starting point of laboratory studies on which group selection was imposed as a treatment. Several dozen similar studies (imposed group selection in laboratory populations) were conducted through the decades, generally finding rapid responses to the group selection treatments after a few generations. Further, such imposed group selection studies found that selection sometimes acts in concert and sometimes in opposition at the individual and group levels, also with varying strength. Interestingly, the same pattern is found when analyzing contextual analysis studies (Figure 4): natural selection sometimes acts at the same and sometimes at different directions and strengths across levels of biological organization. As such, no generalization can be made about MLS and it should be investigated on a case by case manner (Wilson and Wilson, 2007; Eldakar and Wilson, 2011). However, ecological constraints can help predict responses to selection. For example, when in 2017 the category 4 Hurricane Maria almost totally destroyed a Puerto Rican island inhabited by rhesus macaques, shade became a very scarce resource. As a response, there was a marked increase in tolerance and decrease in aggression among macaques (Testard et al., 2024), with the most tolerant animals having the highest survival. Similarly, in plant-mycorrhizal associations it has long been known that under scarcity of nutrients (particularly nitrogen and phosphorous), this symbiotic association becomes more mutualistic while under “luxury” conditions (excess of nutrients), the usually benign mycorrhizal fungal microbiomes can behave as nutritional parasites (Johnson et al., 1997; Johnson and Marín, 2025).

Several other influential MLS experimental studies include Craig and Muir (1996), Swenson et al. (2000), Ratcliff et al. (2012), and Bozdag et al. (2023) (Table 3). Craig and Muir (1996) and several dozen more studies (a total of 32 studies; Figure 3) have shown that MLS is a very useful framework for breeding programs of farm animals and crops. Furthermore, when farm animals or crops are bred through group selection treatments (i.e., selecting group traits) or when IGEs are considered in breeding programs, the outcome is almost always the desired for the farmer: higher yields or more production. Even MLS sceptics recognize the value of MLS-focused breeding programs in wheat cultivars (Zhu et al., 2019b; Zhu et al., 2019a; Zhu et al., 2022). Empirical evidence showing the success of wheat breeding for higher yields over the past 100 years in north-western China has been argued to result in part from “unconscious group selection on root traits” (Zhu et al., 2019b), which results in smaller, less branched, and deeper roots.

Swenson et al. (2000) pioneered the framework of artificial ecosystem selection as a way of selecting communities of soil microorganisms based on plant performance. This implies exposing multiple generations of plants to particular selection pressures, selecting the microbiomes that increase plant fitness (or selected traits) to the next generation, while the genetic basis of the host remains the same. This approach has been successfully used to engineer belowground communities that increase plant tolerance to drought (Lau and Lennon, 2012; Jochum et al., 2019) and salinity (Mueller et al., 2021), or that increase leaf greenness (Jacquiod et al., 2022), among others (reviewed in Sánchez et al., 2021; Sanchez et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2023). On their part, Ratcliff et al. (2012) and Bozdag et al. (2023), implementing artificial selection regimes in yeast aggregates, have shown some of the most visually stunning examples of experimental MLS: they shown de novo evolution of macroscopic multicellularity just after one year and 600 rounds of selection (Bozdag et al., 2023). In particular, in an anaerobic treatment, yeast evolved to be macroscopic, becoming 2 x 104 times larger than at the beginning, while maintaining a clonal multicellular life cycle (Bozdag et al., 2023).

A MLS framework has long been used to investigate human culture (Soltis et al., 1995), originating a whole sub-discipline, deemed “cultural multilevel selection” (Wilson et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2023). In our review, a total of 30 MLS empirical studies were centered around humans: 19 consisted of psychological experiments, 10 assessed or inferred cultural MLS in situ, and one implemented contextual analysis over 55 years of polygyny and polyandry data, based on the Utah Population Database (Moorad, 2013). MLS seems to explain the most important cultural macro-evolutionary patterns and historical trends, including competition and warfare but also exchange and selective imitation (Turchin and Gavrilets, 2021) (Table 2). The utility of MLS has been recognized in anthropology: a survey to 175 evolutionary anthropologists (faculty members of graduate programs) finds that 78.7% of them regard cultural MLS as “important”, while 64.9% disagree with the statement “Group selection has no useful role to play in social science” (Yaworsky et al., 2015). Whether a similar acceptance rate of MLS by evolutionary biologists not working with humans is yet to be analyzed/surveyed. However, it is worth noticing that two recent analyses of biology, evolution, and behavior undergraduate textbooks show that MLS theory is generally dismissed as unimportant when compared to individual selection (Greene et al., 2025), with teaching on evolutionary transitions in individuality also being absent (La et al., 2025).

Our findings showing a marked increase in MLS research in the last 12 years (Figure 2), with 199 MLS studies for 2012–2024, indicates both that MLS is becoming more accepted as a conceptual framework and that many studies are using adequate sample sizes to ask questions across levels of biological organization. With the marked increase since 2012 and expanding acceptance of MLS as an conceptual evolutionary framework, many more ground-breaking studies are to come in the next few decades.

There are some caveats to our findings that the evidence for MLS is vast. First, we expect a publication bias towards studies finding positive outcomes, by which we mean that some studies where no selection at a higher level was found, were likely not captured. Despite this, our database does include studies in which higher-level selection or group properties were not important in explaining focal individual trait variation and fitness (Philson and Blumstein, 2023a; Philson and Blumstein, 2023b). Further, in several of the contextual analysis studies (Tsuji, 1995; Donohue, 2003; Weinig et al., 2007; Boege, 2010; Eldakar et al., 2010; Formica et al., 2011; Bolstad et al., 2012; Laiolo and Obeso, 2012; Fisher et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2021) (Figure 4), the magnitude of selection was stronger at the individual than at the group level. Similarly, direct genetic effects are also usually stronger than indirect genetic effects, as shown by the meta-analysis of Santostefano et al. (2025) and through our database (but see Santostefano et al., 2021). However, because MLS should be evaluated in a case-by-case basis (Wilson and Wilson, 2007), this is not problematic for our framework: depending on the environmental context, case, and traits, it is expected that there will be cases in which there are no group effects or they are not as important as individual-level effects. It is, in fact, a central point that, unless a MLS perspective is applied, one would not know if or how strongly individual selection was causally related to trait evolution (Wade, 2026). Secondly, in order to have a distinct cut-off, we excluded MLS empirical evidence produced after 2024, thus missing new studies such as Lipowska et al. (2025), showing how bank vole holobionts selected for herbivorous capability evolved distinct and robust gut bacterial communities.

In general, we were quite strict in our search. For example, a study classically cited by some as the first MLS empirical study (Lewontin, 1962) was excluded, because, although it is based on real lab mice population data, the conclusions (about interdemic selection) are based on Monte Carlo simulations. Similarly, studies arguing that MLS is a “likely” (Dyer et al., 2005) or “possible” (Aviles, 1986) explanation were also excluded. Thus our total of 280 articles obtained is an underestimate of the evidence and conceptual use, because many more studies that clearly show results consistent with the MLS framework (Pope, 1992; Heinsohn and Packer, 1995; Ingvarsson, 2000; Papkou et al., 2023; Barnett et al., 2025), have historically avoiding using the term (Eldakar and Wilson, 2011; Greene et al., 2025). For example results based on Wright’s fitness landscapes (Papkou et al., 2023) or on evolvability (Barnett et al., 2025), explicitly require a MLS perspective to understand them, but avoid the terminology. Although a MLS framework may not be explicitly mentioned by name, and in some cases may be avoided due to historical misconceptions (Eldakar and Wilson, 2011), it is implicit in experimental design and rationale.

5 Conclusions

In summary, a thorough search of the literature shows that contrary to common misconceptions which plagued the field since the 1960s, there is vast empirical evidence of selection acting at multiple levels and of the utility of assessing multilevel selection (MLS) both in situ and via experimental studies. We found 280 papers providing empirical support for MLS: 100 in situ and 180 laboratory experiments. The studies span many taxa and research methodologies, meaning MLS is not situational or an exception: MLS is a powerful evolutionary force in nature. Disregarding MLS will continue to hold the field of evolutionary biology back and prevent us from more fully understanding life on earth.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. AC: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. CP: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. OE: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. MW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Funded by Fondecyt Regular Project No. 1240186 (ANID, Chile).

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to David Sloan Wilson for helpful comments and suggestions and to Mitchel Distin and the Multilevel Selection Initiative (https://www.prosocial.world/prosocial-initiatives/the-multilevel-selection-initiative), for support, helpful academic discussion, and prosociality. CM thanks ANID + Convocatoria Nacional Subvención a Instalación en la Academia Convocatoria Año 2021 + Folio no. SA77210019 and the Fondecyt Regular Project no. 1240186 (ANID, Convocatoria 2024). Many thanks to Felipe G. Serrano (https://illustrative-science.com/) for Figure 3 artwork.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author CM declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2026.1752597/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aktipis C. A. Boddy A. M. Jansen G. Hibner U. Hochberg M. E. Maley C. C. et al . (2015). Cancer across the tree of life: cooperation and cheating in multicellularity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc B370, 20140219. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0219

2

Arnold S. J. Wade M. J. (1984). On the measurement of natural and sexual selection: theory. Evolution38, 709–719. doi: 10.2307/2408383

3

Aspi J. Jäkäläniemi A. Tuomi J. Siikamäki P. (2003). Multilevel phenotypic selection on morphological characters in a metapopulation of Silene tatarica. Evolution57 (3), 509–517.

4

Aviles L. (1986). Sex-ratio bias and possible group selection in the social spider Anelosimus eximius. Am. Nat.128, 1–12. doi: 10.1086/284535

5

Barnett M. Meister L. Rainey P. B. (2025). Experimental evolution of evolvability. Science387, eadr2756. doi: 10.1126/science.adr2756

6

Baud A. Casale F. P. Barkley-Levenson A. M. Farhadi N. Montillot C. Yalcin B. et al . (2021). Dissecting indirect genetic effects from peers in laboratory mice. Genome Biol.22, 216. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02415-x

7

Bijma P. (2014). The quantitative genetics of indirect genetic effects: a selective review of modelling issues. Heredity112, 61–69. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2013.15

8

Bijma P. Wade M. J. (2008). The joint effects of kin, multilevel selection and indirect genetic effects on response to genetic selection. J. Evol. Biol.21, 1175–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01550.x

9

Blackstone N. W. Blackstone S. R. Berg A. T. (2020). Variation and multilevel selection of SARS-CoV-2. Evolution74, 2429–2434. doi: 10.1111/evo.14080

10

Boege K. (2010). Induced responses to competition and herbivory: natural selection on multi-trait phenotypic plasticity. Ecology91, 2628–2637. doi: 10.1890/09-0543.1

11

Bolstad G. H. Pelabon C. Larsen L. K. Fleming I. A. Viken Å. Rosenqvist G. (2012). The effect of purging on sexually selected traits through antagonistic pleiotropy with survival. Ecol. Evol.2, 1181–1194. doi: 10.1002/ece3.246

12

Bouwhuis S. Vedder O. Garroway C. J. Sheldon B. C. (2015). Ecological causes of multilevel covariance between size and first-year survival in a wild bird population. J. Anim. Ecol.84 (1), 208–218.

13

Bozdag G. O. Zamani-Dahaj S. A. Day T. C. Kahn P. C. Burnetti A. J. Lac D. T. et al . (2023). De novo evolution of macroscopic multicellularity. Nature617, 747–754. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06052-1

14

Burch J. Chin M. Fontenot B. E. Mandal S. McKnight T. D. Demuth J. P. et al . (2024). Wright was right: leveraging old data and new methods to illustrate the critical role of epistasis in genetics and evolution. Evolution78, 624–634. doi: 10.1093/evolut/qpae003

15

Buttery N. J. Thompson C. R. L. Wolf J. B. (2010). Complex genotype interactions influence social fitness during the developmental phase of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Evol. Biol.23, 1664–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02032.x

16

Costello R. A. Cook P. A. Brodie E. D. III Formica V. A. (2023). Multilevel selection on social network traits differs between sexes in experimental populations of forked fungus beetles. Evolution77 (1), 289–303.

17

Craig J. V. Muir W. M. (1996). Group selection for adaptation to multiple-hen cages: beak-related mortality, feathering, and body weight responses. Poul. Sci.75, 294–302. doi: 10.3382/ps.0750294

18

Damuth J. Heisler I. L. (1988). Alternative formulations of multilevel selection. Biol. Philos.3, 407–430. doi: 10.1007/BF00647962

19

Darwin C. (1871). The Descent of Man (London, United Kingdom: John Murray).

20

Donohue K. (2003). The influence of neighbor relatedness on multilevel selection in the Great Lakes sea rocket. Am. Nat.162, 77–92. doi: 10.1086/375299

21

Donohue K. (2004). Density-dependent multilevel selection in the great lakes sea rocket. Ecology85, 180–191. doi: 10.1890/02-0767

22

Dyer K. A. Minhas M. D. Jaenike J. (2005). Expression and modulation of embryonic male-killing in Drosophila innubila: opportunities for multilevel selection. Evolution59, 838–848. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01757.x

23

Eldakar O. T. Wilson D. S. (2011). Eight criticisms not to make about group selection. Evolution65, 1523–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01290.x

24

Eldakar O. T. Gallup A. C. (2011). The group-level consequences of sexual conflict in multigroup populations. PloS One6 (10), e26451.

25

Eldakar O. T. Wilson D. S. Dlugos M. J. Pepper J. W. (2010). The role of multilevel selection in the evolution of sexual conflict in the water strider Aquarius remigis. Evolution64, 3183–3189. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01087.x

26

Fisher D. N. Boutin S. Dantzer B. Humphries M. M. Lane J. E. McAdam A. G. (2017). Multilevel and sex-specific selection on competitive traits in North American red squirrels. Evolution71, 1841–1854. doi: 10.1111/evo.13270

27

Fisher D. N. LeGrice R. J. Painting C. J. (2021). Social selection is density dependent but makes little contribution to total selection in New Zealand giraffe weevils. Proc. R. Soc B: Biol. Sci.288, 20210696. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2021.0696

28

Formica V. A. McGlothlin J. W. Wood C. W. Augat M. E. Butterfield R. E. Barnard M. E. et al . (2011). Phenotypic assortment mediates the effect of social selection in a wild beetle population. Evolution65, 2771–2781. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01340.x

29

Francois P. Fujiwara T. van Ypersele T. (2018). The origins of human prosociality: Cultural group selection in the workplace and the laboratory. Sci. Adv.4, eaat2201. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat2201

30

Frank S. A. (2025). Natural selection at multiple scales. Evolution79, 1166–1184. doi: 10.1093/evolut/qpaf037

31

Gitschlag B. L. Tate A. T. Patel M. R. (2020). Nutrient status shapes selfish mitochondrial genome dynamics across different levels of selection. eLife9, e56686. doi: 10.7554/eLife.56686

32

Goodnight C. (2013). On multilevel selection and kin selection: contextual analysis meets direct fitness. Evolution67, 1539–1548. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01821.x

33

Goodnight C. J. (2015). Multilevel selection theory and evidence: a critique of Gardner, 2015. J. Evol. Biol.28, 1734–1746. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12685

34

Goodnight C. J. Schwartz J. M. Stevens L. (1992). Contextual analysis of models of group selection, soft selection, hard selection, and the evolution of altruism. Am. Nat.140, 743–761. doi: 10.1086/285438

35

Goodnight C. J. Stevens L. (1997). Experimental studies of group selection: what do they tell us about group selection in nature? Am. Nat.150, s59–s79. doi: 10.1086/286050

36

Gould S. J. Lloyd E. A. (1999). Individuality and adaptation across levels of selection: how shall we name and generalize the unit of Darwinism? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.96, 11904–11909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.11904

37

Greene C. A. McPeek S. J. Mitchem L. Clark A. B. Formica V. A. Philson C. S. et al . (2025). Multilevel selection in the margins: A review of its representation in undergraduate biology textbooks. Ecol. Evol.15, e72493. doi: 10.1002/ece3.72493

38

Harms K. E. Watson D. M. Santiago-Rosario L. Y. Mathews S. (2023). Exposing the error hidden in plain sight: A critique of Calder’s (1983) group selectionist seed-dispersal hypothesis for mistletoe “mimicry” of host plants. Ecol. Evol.13, e10760. doi: 10.1002/ece3.10760

39

Heinsohn R. Packer C. (1995). Complex cooperative strategies in group-territorial African lions. Science269, 1260–1262. doi: 10.1126/science.7652573

40

Heisler I. L. Damuth J. (1987). A method for analyzing selection in hierarchically structured populations. Am. Nat.130, 582–602. doi: 10.1086/284732

41

Herron M. D. Michod R. E. (2008). Evolution of complexity in the volvocine algae: transitions in individuality through Darwin’s eye. Evolution62, 436–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00304.x

42

Hertler S. C. Figueredo A. J. Peñaherrera-Aguirre M. (2020). Multilevel selection: Theoretical foundations, historical examples, and empirical evidence (Berlin, Germany: Springer Nature).

43

Ingvarsson P. K. (2000). Differential migration from high fitness demes in the shining fungus beetle, Phalacrus substriatus. Evolution54, 297–301. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00031.x

44

Jacquiod S. Spor A. Wei S. Munkager V. Bru D. Sørensen S. J. et al . (2022). Artificial selection of stable rhizosphere microbiota leads to heritable plant phenotype changes. Ecol. Lett.25, 189–201. doi: 10.1111/ele.13916

45

Jany J. L. Pawlowska T. E. (2010). Multinucleate spores contribute to evolutionary longevity of asexual Glomeromycota. Am. Nat.175, 424–435. doi: 10.1086/650725

46

Jochum M. D. McWilliams K. L. Pierson E. A. Jo Y. K. (2019). Host-mediated microbiome engineering (HMME) of drought tolerance in the wheat rhizosphere. PloS One14, e0225933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225933

47

Johnson N. C. Graham J. H. Smith F. A. (1997). Functioning of mycorrhizal associations along the mutualism–parasitism continuum. New Phytol.135, 575–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00729.x

48

Johnson N. C. Marín C. (2025). Functional team selection as a framework for local adaptation in plants and their belowground microbiomes. ISME J.19, wraf137. doi: 10.1093/ismejo/wraf137

49

La S. Grochau-Wright Z. I. Hoskinson J. S. Davison D. R. Michod R. E. (2025). Translating research on evolutionary transitions into the teaching of hierarchical complexity in university biology courses. Ecol. Evol.15, e72267. doi: 10.1002/ece3.72267

50

Laiolo P. Obeso J. R. (2012). Multilevel selection and neighbourhood effects from individual to metapopulation in a wild passerine. PloS One7, e38526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038526

51

Lande R. Arnold S. J. (1983). The measurement of selection on correlated characters. Evolution37, 1210–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1983.tb00236.x

52

Lau J. A. Lennon J. T. (2012). Rapid responses of soil microorganisms improve plant fitness in novel environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.109, 14058–14062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202319109

53

Lee I. P. A. Eldakar O. T. Gogarten J. P. Andam C. P. (2022). Bacterial cooperation through horizontal gene transfer. Trends Ecol. Evol.37, 223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2021.11.006

54

Levins R. (1970). “ Extinction,” in Some Mathematical Questions in Biology, vol. 2. Ed. GerstenhaberM. (Providence, Rhode Island, US: American Mathematical Society), 77–107.

55

Lewontin R. C. (1962). Interdeme selection controlling a polymorphism in the house mouse. Am. Nat.96, 65–78. doi: 10.1086/282208

56

Linksvayer T. A. Fondrk M. K. Page R. E. Jr. (2009). Honeybee social regulatory networks are shaped by colony-level selection. Am. Nat.173, E99–E107. doi: 10.1086/596527

57

Lipowska M. M. Sadowska E. T. Kohl K. D. Koteja P. (2025). Experimental evolution of a mammalian holobiont: bank voles selected for herbivorous capability evolved distinct and robust gut bacterial communities. ISME Commun.5, ycaf160. doi: 10.1093/ismeco/ycaf160

58

Lloyd E. (2024). Units and levels of selection, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2024 edition). Eds. ZaltaE. N.NodelmanU. Available online at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2024/entries/selection-units/ (Accessed January 21, 2025).

59

Marín C. (2015). Selección Multinivel: historia, modelos, debates, y principalmente, evidencias empíricas. eVOLUCIÓN: Rev. la Sociedad Española Biología Evolutiva10, 51–70.

60

Marín C. (2016). The levels of selection debate: taking into account existing empirical evidence. Acta Biol. Colomb21, 467–472. doi: 10.15446/abc.v21n3.54596

61

Marín C. (2021). Spatial and density-dependent multilevel selection on weed-infested maize. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol.68 (3), 885–897.

62

Marín C. (2024). Three types of units of selection. Evolution78, 579–586. doi: 10.1093/evolut/qpad234

63

Marín C. Wade M. J. (2025). Bring back the phenotype. New Phytol.246, 2440–2445. doi: 10.1111/nph.70138

64

Maynard Smith J. (1964). Group selection and kin selection. Nature201, 1145–1146. doi: 10.1038/2011145a0

65

Montazeri A. Mohammadi S. M.Hesari P. Ghaemi M. Riazi H. Sheikhi-Mobarakeh Z. (2023). Preliminary guideline for reporting bibliometric reviews of the biomedical literature (BIBLIO): a minimum requirements. Syst. Rev.12, 239. doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02410-2

66

Moorad J. A. (2013). Multi-level sexual selection: individual and family-level selection for mating success in a historical human population. Evolution67, 1635–1648. doi: 10.1111/evo.12050

67

Mueller U. G. Juenger T. E. Kardish M. R. Carlson A. L. Burns K. M. Edwards J. A. et al . (2021). Artificial selection on microbiomes to breed microbiomes that confer salt tolerance to plants. mSystems6, e01125–e01121. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.01125-21

68

Okasha S. (2003). The concept of group heritability. Biol. Philos.18, 445–461. doi: 10.1023/A:1024140123391

69

Okasha S. (2006). Evolution and the levels of selection (New York, United States: Oxford University Press).

70

Papkou A. Garcia-Pastor L. Escudero J. A. Wagner A. (2023). A rugged yet easily navigable fitness landscape. Science382, eadh3860. doi: 10.1126/science.adh3860

71

Philson C. S. Blumstein D. T. (2023a). Group social structure has limited impact on reproductive success in a wild mammal. Behav. Ecol.34, 89–98. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arac102

72

Philson C. S. Blumstein D. T. (2023b). Emergent social structure is typically not associated with survival in a facultatively social mammal. Biol. Lett.19, 20220511. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2022.0511

73

Philson C. S. Martin J. G. Blumstein D. T. (2025). Multilevel selection on individual and group social behaviour in the wild. Proc. R. Soc B: Biol. Sci.292, 20243061. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2024.3061

74

Pope T. R. (1992). The influence of dispersal patterns and mating system on genetic differentiation within and between populations of the red howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus). Evolution46, 1112–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1992.tb00623.x

75

Ratcliff W. C. Denison R. F. Borrello M. Travisano M. (2012). Experimental evolution of multicellularity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.109, 1595–1600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115323109

76

Robinson S. D. Schendel V. Schroeder C. I. Moen S. Mueller A. Walker A. A. et al . (2023). Intra-colony venom diversity contributes to maintaining eusociality in a cooperatively breeding ant. BMC Biol.21, 5. doi: 10.1186/s12915-022-01507-9

77

Sanchez A. Bajic D. Diaz-Colunga J. Skwara A. Vila J. C. Kuehn S. (2023). The community-function landscape of microbial consortia. Cell Syst.14, 122–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2022.12.011

78

Sánchez Á. Vila J. C. Chang C. Y. Diaz-Colunga J. Estrela S. Rebolleda-Gomez M. (2021). Directed evolution of microbial communities. Annu. Rev. Biophys.50, 323–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-101220-072829

79

Santostefano F. Garant D. Bergeron P. Montiglio P. O. Reale D. (2020). Social selection acts on behavior and body mass but does not contribute to the total selection differential in eastern chipmunks. Evolution74 (1), 89–102.

80

Santostefano F. Allegue H. Garant D. Bergeron P. Réale D. (2021). Indirect genetic and environmental effects on behaviors, morphology, and life-history traits in a wild Eastern chipmunk population. Evolution75, 1492–1512. doi: 10.1111/evo.14232

81

Santostefano F. Moiron M. Sánchez-Tójar A. Fisher D. N. (2025). Indirect genetic effects increase the heritable variation available to selection and are largest for behaviors: a meta-analysis. Evol. Lett.9, 89–104. doi: 10.1093/evlett/qrae051

82

Soltis J. Boyd R. Richerson P. J. (1995). Can group-functional behaviors evolve by cultural group selection?: An empirical test. Curr. Anthropol.36, 473–494. doi: 10.1086/204381

83

Stevens L. Goodnight C. J. Kalisz S. (1995). Multilevel selection in natural populations of Impatiens capensis. Am. Nat.145, 513–526. doi: 10.1086/285753

84

Stinson K. A. Brophy C. Connolly J. (2011). Catching up on global change: new ragweed genotypes emerge in elevated CO2 conditions. Ecosphere2 (4), 1–11.

85

Suárez J. Lloyd E. A. (2023). Units of selection (Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press).

86

Swenson W. Wilson D. S. Elias R. (2000). Artificial ecosystem selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.97, 9110–9114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150237597

87

Takeuchi N. Kaneko K. (2019). The origin of the central dogma through conflicting multilevel selection. Proc. R. Soc B: Biol. Sci.286, 20191359. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2019.1359

88

Testard C. Shergold C. Acevedo-Ithier A. Hart J. Bernau A. Negron-Del Valle J. E. et al . (2024). Ecological disturbance alters the adaptive benefits of social ties. Science384, 1330–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.adk0606

89

Tsuji K. (1995). Reproductive conflicts and levels of selection in the ant Pristomyrmex pungens: contextual analysis and partitioning of covariance. Am. Nat.146, 586–607. doi: 10.1086/285816

90

Turchin P. Gavrilets S. (2021). Tempo and mode in cultural macroevolution. Evol. Psychol.19, 4. doi: 10.1177/14747049211066600

91

Volis S. Mendlinger S. Ward D. (2002). Differentiation in populations of Hordeum spontaneum along a gradient of environmental productivity and predictability: life history and local adaptation. Biol. J. Linn. Soc.77 (4), 479–490.

92

Wade M. J. (1976). Group selections among laboratory populations of Tribolium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.73, 4604–4607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4604

93

Wade M. J. (2026). “ Sewall wright and the shifting balance theory,” in Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Biology, 2nd ed. Eds. WolfJ. B.De Moraes RussoC. A. ( Academic Press, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), 387–395. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-15750-9.00111-7

94

Weinig C. Johnston J. A. Willis C. G. Maloof J. N. (2007). Antagonistic multilevel selection on size and architecture in variable density settings. Evolution61, 58–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00005.x

95

Williams G. C. (1966). Adaptation and natural selection: A critique of some current evolutionary thought (Princeton, United States: Princeton University Press).

96

Wilson D. S. (1975). A theory of group selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.72, 143–146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.143

97

Wilson D. S. Madhavan G. Gelfand M. J. Hayes S. C. Atkins P. W. Colwell R. R. (2023). Multilevel cultural evolution: From new theory to practical applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.120, e2218222120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2218222120

98

Wilson D. S. Philip M. M. MacDonald I. F. Atkins P. W. Kniffin K. M. (2020). Core design principles for nurturing organization-level selection. Sci. Rep.10, 13989. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70632-8

99

Wilson D. S. Sober E. (1994). Reintroducing group selection to the human behavioral sciences. Behav. Brain Sci.17, 585–608. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00036104

100

Wilson D. S. Wilson E. O. (2007). Rethinking the theoretical foundation of sociobiology. Q. Rev. Biol.82, 327–348. doi: 10.1086/522809

101

Wright S. (1945). Tempo and mode in evolution: a critical review. Ecology26, 415–419. doi: 10.2307/1931666

102

Yaworsky W. Horowitz M. Kickham K. (2015). Gender and politics among anthropologists in the units of selection debate. Biol. Theory10, 145–155. doi: 10.1007/s13752-014-0196-5

103

Yu S. R. Zhang Y. Y. Zhang Q. G. (2023). The effectiveness of artificial microbial community selection: a conceptual framework and a meta-analysis. Front. Microbiol.14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1257935

104

Zhu Y. H. Weiner J. Jin Y. Yu M. X. Li F. M. (2022). Biomass allocation responses to root interactions in wheat cultivars support predictions of crop evolutionary ecology theory. Front. Plant Sci.13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.858636

105

Zhu Y. H. Weiner J. Li F. M. (2019a). Root proliferation in response to neighbouring roots in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Basic Appl. Ecol.39, 10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2019.07.001

106

Zhu Y. H. Weiner J. Yu M. X. Li F. M. (2019b). Evolutionary agroecology: Trends in root architecture during wheat breeding. Evol. Appl.12, 733–743. doi: 10.1111/eva.12749

Summary

Keywords

artificial selection, breeding, contextual analysis, cultural evolution, indirect genetic effects, multicellularity, units of selection, group selection

Citation

Marín C, Clark AB, Philson CS, Eldakar OT and Wade MJ (2026) Abundant empirical evidence of multilevel selection revealed by a bibliometric review. Front. Ecol. Evol. 14:1752597. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2026.1752597

Received

23 November 2025

Accepted

05 January 2026

Published

10 February 2026

Volume

14 - 2026

Edited by

Sabine Nöbel, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Germany

Reviewed by

Tomas Veloz, Vrije University Brussels, Belgium

W. Ford Doolittle, Dalhousie University, Canada

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Marín, Clark, Philson, Eldakar and Wade.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: César Marín, cmarind@santotomas.cl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.