- 1Biofood and Nutraceutics Research and Development Group, Faculty of Engineering in Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Universidad Técnica del Norte, Ibarra, Ecuador

- 2Research Institute of the University of Bucharest-ICUB, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

- 3Independent Research Association, Bucharest, Romania

- 4Blue Screen SRL, Bucharest, Romania

Introduction: Microbial fermentation by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) significantly influences the flavor, quality, and functional attributes of coffee. However, the specific metabolic outputs and roles of LAB native strains to distinct Coffea arabica ecosystems remain insufficiently understood. This study aimed to characterize the metabolite profiles and functional signatures of cell-free supernatants (CFS) from six indigenous LAB strains isolated from three Ecuadorian coffee varieties, C. arabica var. Typica (TYP), C. arabica var. Yellow Caturra (CATY), and C. arabica var. Red Caturra (CATR), harvested at two ripening stages (green and yellow/red).

Methods: Metabolite profiling was performed using capillary liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with a SWATH-based data-independent acquisition (DIA) strategy in positive electrospray ionization (ESI+) mode, enabling detection of metabolites associated with flavor development, stress response, and antimicrobial potential. Functional group analysis via attenuated total reflectance Fourier transforms infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy provided insights into structural and biochemical changes, including protein, carbohydrate, and lipid modifications during LAB activity. Total polyphenol content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) were quantified to assess nutritional and antioxidant shifts.

Results: Strain-specific metabolic signatures were identified. Lactiplantibacillus strains (B3, B6, B9, B10, B17) showed enriched biosynthesis of harmala alkaloids, isoflavonoids, indole derivatives, and bioactive peptides (e.g., FruLeuIle), which may contribute to enhanced aroma and bioactivity. Weissella (B19) exhibited a simpler profile, dominated by organic acids and benzene derivatives, potentially enhancing acidity and freshness. FTIR analysis revealed that B6, B10, B17, and B19 released distinctive extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, and aromatic compounds, shaping the fermented matrix.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates the functional diversity of indigenous LAB strains from C. arabica cherries, showing that their strain-specific metabolic signatures reshape the fermentation matrix and highlighting their potential for targeted microbial selection to enhance flavor complexity, quality, and the market value of Ecuadorian specialty coffees.

1 Introduction

Coffea arabica L., which represents around 70% of global coffee consumption, owes its distinctive flavor, aroma, and sensory quality not only to its genetic background and agronomic conditions but also to the complex microbial interactions that occur during post-harvest fermentation (Todhanakasem et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2025). Microbial communities comprising bacteria, yeasts, and filamentous fungi drive the biochemical transformations of coffee mucilage, generating key flavor precursors that shape the final cup profile (Bernardes, 2024; Hu et al., 2025). Among these, LAB play a particularly significant role through their metabolic activity, producing organic acids and volatile compounds that enhance acidity, sweetness, and overall flavor complexity (Duque-Buitrago et al., 2025).

Ecuador, with its high biodiversity and favorable climate, is emerging as a notable origin of specialty C. arabica production (Mihai et al., 2024), though it faces challenges from climate variability, plant diseases, and infrastructural limitations (Torres Castillo et al., 2020). The Intag Valley in northern Ecuador exemplifies eco-friendly agroforestry, where coffee is intercropped with banana, papaya, and cacao, supporting biodiversity while fostering diverse microbial communities on coffee cherries that influence fermentation outcomes (Venegas Sánchez et al., 2018; Todhanakasem et al., 2024).

Previously, our shotgun metagenomic study of three C. arabica varieties, Typica, Yellow Caturra, and Red Caturra, at two ripeness stages revealed a rich microbial diversity, including several LAB strains, with clear variety- and stage-specific community shifts (Tenea et al., 2025). While this study focused on the broader microbial diversity, the observed variations in the dominant bacterial genera and species across the coffee varieties strongly suggest that the LAB communities within these fermentations also differed, which would likely lead to variations in their respective metabolite profiles. For instance, Levilactobacillus and Lactiplantibacillus were dominant in Typica and Red Caturra, whereas Acetobacter was more abundant in Yellow Caturra (Tenea et al., 2025). These differences in LAB genera point toward potential variations in the types and quantities of metabolites produced. These findings suggest that varietal biochemical differences, particularly in sugars (sucrose, glucose, fructose), organic (citric, malic) acids, amino acids, and phenolic compounds, serve as distinct fermentation substrates that steer LAB metabolism (Mengesha et al., 2024). Moreover, the presence of anthocyanins in red and carotenoids in yellow varieties reflects divergent metabolic environments that further modulate LAB enzymatic activity and metabolite profiles (Tenea et al., 2025). Understanding these cultivar-specific microbial interactions is critical for optimizing fermentation to enhance desirable sensory traits (Silva et al., 2024).

LAB fermentation of coffee not only modulates its chemical composition, including chlorogenic acid, phenolics, and caffeine, but also enhances flavor, bioactivity, and functional properties, highlighting LAB potential to improve both the sensory quality and health benefits of specialty coffee (de Melo Pereira et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2024). Beyond flavor modulation, LAB also produce bioactive compounds such as peptides, organic acids, and phenolics with antioxidant properties, which can stabilize flavor precursors, protect aromatic molecules from oxidative degradation, and contribute to more complex and durable sensory profiles (de Carvalho Neto et al., 2018; Su et al., 2018; Tan et al., 2023). However, in this study, we comprehensively characterize the metabolomic profiles of six LAB strains isolated from Coffea arabica varieties, Typica, Yellow Caturra, and Red Caturra, harvested at both green and ripe stages. Capillary LC–MS/MS, coupled with a SWATH-based data-independent acquisition (DIA) strategy in positive electrospray ionization mode (ESI+), was employed to comprehensively characterize the metabolic outputs of LAB. This approach enabled the evaluation of strain- and cultivar-specific variations in metabolite production and their associations with flavor development, stress adaptation, and antimicrobial potential. In parallel, we employ ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to monitor structural and functional biochemical changes in the CFS, providing insights into the release and transformation of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and aromatic compounds during fermentation. Additionally, we assess total phenolic and flavonoid content in the CFS to explore their potential contributions to the antioxidant capacity, nutritional value, and sensory properties of fermented coffee. This integrated analytical approach allows for the identification of ripeness- and cultivar-dependent LAB metabolic signatures that enhance desirable sensory and functional traits. Ultimately, the outcome is a deeper understanding of how microbial fermentation modulates coffee biochemistry and flavor development, guiding the design of tailored, precision fermentation protocols. Our findings contribute to advancing microbial-based strategies for improving the sensory complexity and bioactive potential of Ecuadorian specialty coffees, with implications for enhancing their market value both locally and internationally.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial isolates identification and culture

Six LAB isolates were obtained from fermented coffee cherries at two ripeness stages (green-red and green-yellow) from three C. arabica varieties: Typica (TYP), Yellow Caturra (CATY), and Red Caturra (CATR). For each sample, 500 g of cherries were collected from a coffee farm in the Intag Valley, Peñaherrera parish, Ecuador (0°21′0″ N, 78°44′0″ W), an area characterized by volcanic soil. Fruits were harvested in sterile bags according to ripeness stage, variety, and color (2 stages × 3 varieties × 2 colors), transported to the laboratory, and processed. The cherries were thoroughly washed and allowed to undergo natural fermentation in sterile flasks containing 100 mL of water at room temperature for 9 days. The ferment was inoculated onto MRS-agar containing 1% CaCO3 incubated at 37 °C for 48 h to select for LAB. Colonies were randomly picked from each fermented sample and purified by streaking on MRS-agar before being used for further studies. Using conventional 16S ARN sequencing these isolates were taxonomically identified. In brief, PCR amplification was performed using the primers 27F 5′ (AGA GTT TGA TCM TGG CTC AG) 3′ and 1492R 5′ (TAC GGY TAC CTTGTT ACG ACT T) 3′ (Weisburg et al., 1991), followed by a standard protocol with EF-Taq polymerase (SolGent, Korea). The amplicons were purified and sequenced using a PRISM BigDye Terminator v3.1 kit. Sequencing was carried out with primers 785F 5′ (GGA TTAGAT ACC CTG GTA) 3′ and 907R 5′ (CCG CAA TTC MTT TRA GTT T) 3′ (Muyzer et al., 1993), targeting the 16S RNA V3 region. The sequencing products were analyzed on an ABI Prism 3730XL DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Initial homology search was conducted using the megablast algorithm against the NCBI 16S database. Taxonomic classification was confirmed using the RDP Bayesian classifier algorithm (Wang et al., 2007) with 100 bootstrap replicates, integrated into the DADA2 package (Callahan et al., 2020) for high-resolution sample inference. Table 1 showed the identification codes, origin description of each sample and their NCBI assigned number. The strains were maintained as frozen stock cultures in MRS broth (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA).

Table 1. LAB strains isolated from fermented coffee cherries of different Coffea arabica varieties, including sample codes, species identification, strain codes, and corresponding NCBI accession numbers.

2.2 CFS extraction

To extract CFS, each LAB isolate was first cultured overnight in MRS broth at 37 °C for 24 h. Following incubation, the cultures were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to separate the cell-free supernatant (CFS) from the bacterial cells. The resulting CFS was then passed through a 0.22 μm syringe filter (#STF020025H, Chemlab Group, Washington, DC, USA) and kept at 4 °C until further analysis. The CFS was lyophilized before use.

2.3 ATR-FTIR analysis

FTIR spectra of all freeze-dried samples were recorded using a Cary 630 FTIR Spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA) equipped with an ATR accessory and operated via Agilent MicroLab Software. Spectral acquisition was performed over the 4,000–650 cm–1 range, with 400 scans collected at a resolution of 4 cm–1 under ambient conditions. Freeze-dried MRS broth was used as the reference control.

2.4 Capillary LC-MS/MS procedure, SWATH data acquisition, processing and identification

Approximately 400 mg of each lyophilized CFS sample was rehydrated in 8 mL distilled water, refiltered through a 0.22 μm syringe filter, and centrifuged (15 min, 4 °C, 17,000 × g). The clear supernatant was transferred to vials for LC–MS/MS analysis on an AB SCIEX TripleTOF 5,600+ mass spectrometer coupled to a nanoACQUITY UPLC system equipped with a 5C18-CL-120 column and AB Sciex DuoSpray ion source. Chromatographic separation was achieved using a 90 min acetonitrile gradient (5%–80%, 0.1% formic acid) at 5 μL/min, with the column temperature maintained at 55 °C. The instrument was calibrated every three samples, maintaining mass accuracy within 4 ppm (calibration) and 20 ppm (up to 5 h). Electrospray ionization was performed in positive mode under the following parameters: GS1, 15; GS2, 0; CUR, 25; TEM, 0; ISVF, 5,500 V. Data were acquired in SWATH-MS mode using 60 variable windows (Xiao et al., 2021). MS1 scans covered 100–1,250 m/z (150 ms accumulation), while MS2 spectra were acquired in high-sensitivity mode from 100 to 2,000 m/z (30 ms accumulation), generating a 2 s duty cycle. Collision energy was optimized by Analyst TF 1.8.1 software with a 15 V spread. Untargeted metabolite identification was carried out using MS-DIAL v5.3.240719 and the MSP spectral kit database.1 MS-DIAL parameters included: retention time 1–90 min; MS1 range 100–1,250 Da; MS2 range 100–2,000 Da; minimum peak width, 5 scans; peak height threshold, 1,000 amplitude; smoothing level, 3 scans; MS2 spectrum cutoff, 10 amplitude; mass slice width, 0.05 Da; retention time tolerance, 0.1 min; MS1 tolerance, 0.01 Da; MS2 tolerance, 0.025 Da; matched spectrum ≥ 70%.

2.5 Prediction of enrichment pathways

The metabolites identified by LC–MS were linked to different enrichment pathways through Metabolomics Pathway Analysis version 6.0 (MSEA)2 (Pang et al., 2024). The enrichment tests utilize the globally recognized global test method to assess associations between metabolite sets and the outcome. This algorithm employs a generalized linear model to compute a “Q-stat” for each metabolite set, which is derived as the average of the Q values for each individual metabolite. The Q value represents the squared covariance between the metabolite and the outcome. The global test has demonstrated comparable or superior performance when benchmarked against various other widely used methods. The uploaded compounds list was converted by a built-in tool into common names, synonyms, and identifiers used in HMDB ID, PubChem, and KEGG databases. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database3 was utilized to map these metabolites and determine their roles in metabolic pathways (Kanehisa et al., 2024).

2.6 Quantification of phenolic secondary metabolites

The supernatant was subjected to a liquid-liquid extraction in ethyl acetate (1:1, v: v) and evaporated to dryness. The residue was taken up in 70% ethanol in a volume like the sample volume used for the liquid-liquid extraction.

2.6.1 The total phenolic content (TPC) assay

Following the procedure outlined by Corbu et al. (2022), the Folin-Ciocalteu assay was used to quantify the total phenolic content (TPC). Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (0.1 mL), distilled H2O (1.8 mL), and saturated Na2CO3 (0.1 mL) were combined with an aliquot. To develop the color, the tubes were vortexed for 15 s and then left in the dark for 60 min. At 765 nm, the absorbance was then measured. The same circumstances as the samples were used to create a standard curve with varying gallic acid concentrations (R2 = 0.9972). The amount of TPC was measured in milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per milliliter of extract (mg GAE/L). Three separate analyses were conducted.

2.6.2 The total flavonoid content (TFC) assay

Using the AlCl3 method as described by Corbu et al. (2022), the TFC assay was assessed. To put it briefly, 0.12 mL of 2.5% AlCl3 and 0.1 mL of 10% sodium acetate were combined with 0.1 mL of the sample/standard solution, and the final volume was adjusted to 1 mL using 50% ethanol. After that, the samples were vortexed and left for 45 min in the dark. At λ = 430 nm, absorbances were measured. Various quercetin concentrations were used to create a standard curve (R2 = 0.9996). The total flavonoid concentration was reported as mg of quercetin equivalent per L of extract (mg QE/L). Three separate analyses were conducted.

2.7 Statistical analysis

Based on measurements made in triplicate, all results were displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analyses. The effects of metabolic extracts and culture media (MRS) were evaluated using a pooled variance technique, with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for differences in polyphenols and flavonoids content. The assumptions of ANOVA were verified by assessing normality with the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variances with the Brown–Forsythe test. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05 according to GraphPad Prism software.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 LAB strain-specific metabolic profile shape coffee fermentation flavors

To elucidate the contribution of LAB to coffee fermentation, we applied an integrative metabolomic workflow combining untargeted LC–MS/MS (ESI+), ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, and colorimetric assays. Six representative isolates (B3, B6, B9, B10, B17, and B19) derived from Typica, Yellow Caturra, and Red Caturra cultivars at different ripening stages were selected for comparative analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Workflow for metabolomic profiling of LAB isolated from Coffea arabica cultivars. Fermented isolates were screened for bioactive potential using ATR-FTIR (A), untargeted LC-MS/MS (ESI+) (B), and colorimetric assays (C).

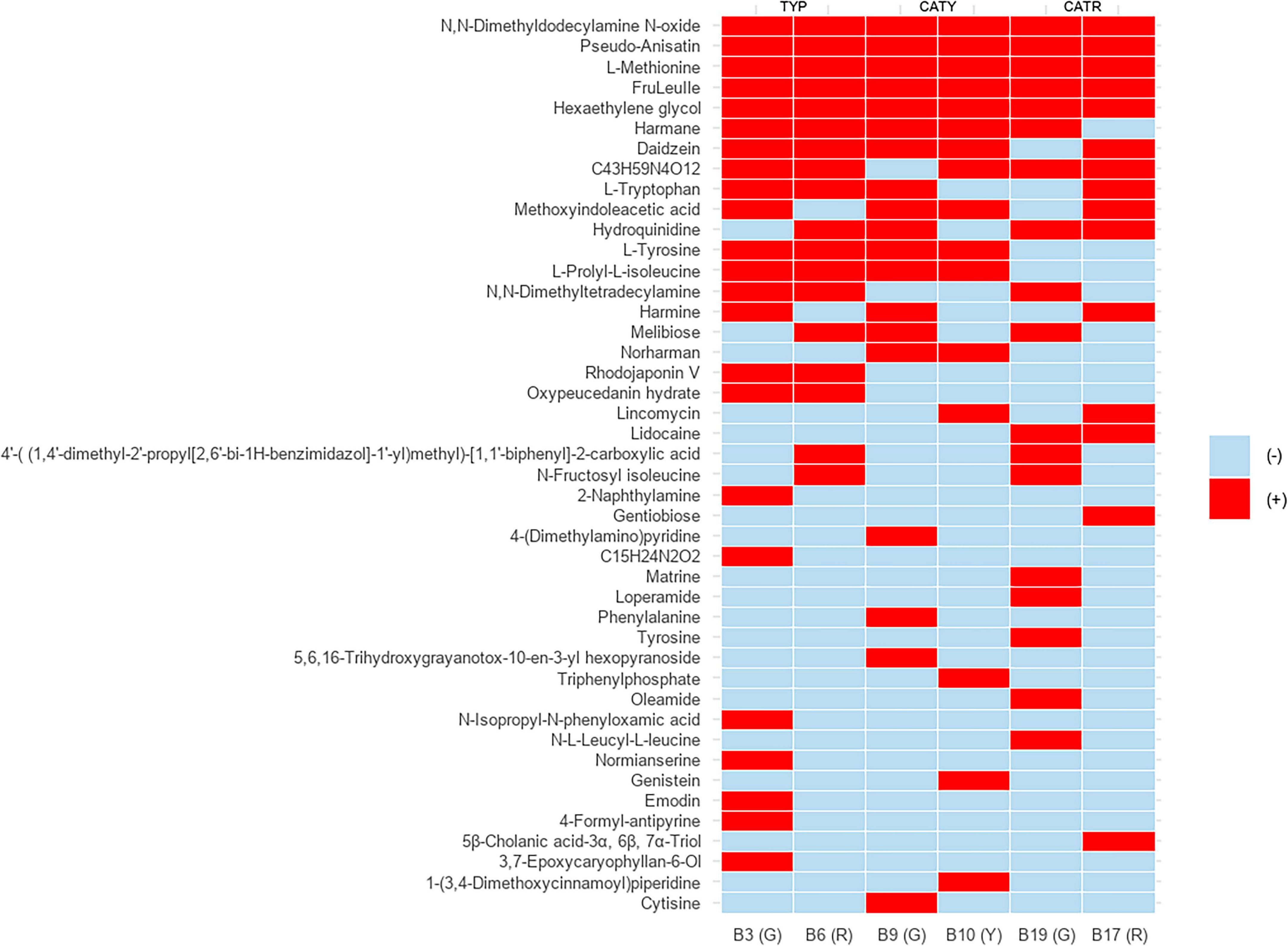

Untargeted LC–MS/MS profiling, visualized as a binary presence–absence heatmap (Figure 2), revealed highly strain-specific metabolite distributions, reflecting distinct biosynthetic and catabolic capacities. Key metabolite classes included aromatic and sulfur-containing amino acids (L-tyrosine, L-tryptophan, L-methionine), disaccharides (melibiose, gentiobiose), β-carboline alkaloids (harmane, norharmane, harmine), isoflavones (daidzein, genistein), and low-molecular-weight peptides such as FruLeuIle. These compounds are well documented for their roles in modulating umami, bitterness, aromatic complexity, and overall sensory perception in fermented foods (Parthasarathy et al., 2018; Haile and Kang, 2019; Schieber and Wüst, 2020).

Figure 2. Presence–absence heatmap of detected metabolites across LAB strains isolated from different coffee cherries varieties (CATR, CATY, TYP). Red bars indicate the presence (+) of specific compounds, while absence is denoted by blue cells (–).

Besides, metabolite origin may derive from both de novo biosynthesis and enzymatic biotransformation of medium-derived substrates. LAB are equipped with proteases, glycosidases, and esterases that hydrolyze proteins, polysaccharides, and phenolic esters into bioactive units (Virdis et al., 2021). Thus, the detected pool of peptides, disaccharides, and aromatic amino acids likely reflects a dual contribution of biosynthetic activity and substrate remodeling. This metabolic plasticity underscores the capacity of LAB to enrich coffee fermentation with structurally diverse, flavor-active metabolites under nutrient-rich conditions.

Drawing from these strain-specific metabolic signatures, aromatic amino acids emerged as pivotal contributors to flavor formation. L-tyrosine derivatives such as p-cresol and tyramine impart subtle spicy and woody nuances (Li et al., 2020), while indole compounds derived from L-tryptophan enhance floral and fruity notes (Xiao et al., 2023). L-methionine, consistently detected across isolates, provides sulfur precursors for volatile compounds that add savory and complex dimensions, like those found in dairy and cured meat products (Bonnarme et al., 2000). Together, these sensory-active metabolites highlight how LAB adapt to the phytochemical richness of C. arabica cherries, translating varietal and environmental differences in sugars, amino acids, and polyphenols into distinctive coffee flavor profiles (Todhanakasem et al., 2024).

In addition to amino acid–derived volatiles, β-carboline alkaloids were identified (Supplementary Figure 1A). Harmane, typically associated with roasted or nutty notes from Maillard reactions (Piechowska et al., 2019), was detected in CFS of LAB representing the first report of harmala-like alkaloids in this group. Traditionally linked to Peganum harmala (Moloudizargari et al., 2013), their occurrence here suggests that LAB may convert tryptophan-derived intermediates into β-carbolines via tryptophan decarboxylase and monoamine oxidase activities (Zuo et al., 2025). This enzymatic route involves tryptamine intermediates and oxidative steps leading to β-carbolines through Pictet–Spengler condensation (Matsui et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). The enrichment of tryptophan and caffeine in coffee berries may provide precursors or cofactors for such pathways, supporting niche-driven metabolic adaptation in LAB. This aligns with previous reports of genomic plasticity in L. plantarum within plant-associated environments (Siezen et al., 2010; Martino et al., 2016). While microbial β-carboline biosynthesis remains rare, it has been demonstrated in engineered E. coli and Streptomyces expressing Pictet–Spenglerases (Kishimoto et al., 2016), highlighting the novelty of our observation of spontaneous β-carboline production in LAB.

Isoflavones were also detected, with daidzein consistently present in Lactiplantibacillus strains (B3, B6, B9, B10, B17) and genistein uniquely in B10 (Supplementary Figures 1B, C). These compounds, known for antioxidant activity and astringency, point to roles beyond flavor modulation (Kim, 2021). Notably, B17 (L. pentosus) showed enriched disaccharide (gentiobiose) and alkaloid (harmine) profiles, indicating enhanced capacity to modulate sweetness, bitterness, and antimicrobial potential (Zhao et al., 2020; Kishimoto et al., 2016).

Moreover, all isolates produced hexaethylene glycol (Supplementary Figure 1D), a surfactant-like compound that, while not flavor-active, may influence aroma solubility and release kinetics (Wijaya et al., 2016). Among Typica-derived strains, B3 and B6 exhibited the broadest metabolite repertoires, underscoring their potential as starter cultures for improving mouthfeel and sensory complexity. In contrast, B9 (L. plantarum) and B19 (W. confusa) showed narrower but distinct metabolic signatures, suggesting application in niche fermentations with unique sensory outputs (Gao et al., 2021).

Finally, metabolites detected in Weissella B19 further underscore functional versatility. 5β-Cholanic acid-3α,6β,7α-triol, a bile acid derivative, may confer antimicrobial activity and bile resistance (Begley et al., 2006), while gentiobiose supports prebiotic effects through selective stimulation of beneficial LAB and short-chain fatty acid production (Mussatto and Mancilha, 2007; Ucar et al., 2020). These features highlight the dual role of W. confusa in probiotic resilience and host–microbe interactions.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that LAB isolated from coffee cherries possess a diverse metabolic repertoire capable of generating flavor-active, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and prebiotic compounds. Such results not only support the application of indigenous LAB strains for precision fermentation but also emphasize the influence of phytochemical-rich coffee environments in shaping microbial secondary metabolism.

3.2 Peptides production: a microbial adaptation to local substrate

Coffee plants grown at higher altitudes are known to accumulate greater concentrations of sugars and polyphenols, contributing to enhanced flavor complexity and unique chemical profiles in the fruit (Tolessa et al., 2017). Red and yellow cherries, which represent more advanced stages of maturation, are characterized by higher concentrations of readily fermentable sugars and free amino acids (Hall et al., 2022). Based on this study, all strains produce small peptides in the CFS, may have undergone selective metabolic adaptation to exploit these nutrient-rich environments. The consistent detection of the tripeptide FruLeuIle suggests a potential link between coffee cherry and microbial peptide biosynthesis during fermentation (Supplementary Figure 1E). This observation indicates a metabolically adaptive response of LAB to the distinct phytochemical environments associated to cherry ripeness.

Lactobacillus species are well known to secrete a variety of extracellular and intracellular peptidases, which hydrolyze host proteins into small bioactive peptides (Pessione and Cirrincione, 2016). During the natural ripening of coffee cherries, proteolytic processes are known to intensify, leading to the accumulation of free amino acids and small peptides because of both plant enzymatic activity and microbial contributions (Bastian et al., 2021). Besides, the production of specific bioactive peptides may play a role in microbial signaling (quorum sensing), stress resistance, and the formation of precursor molecules for volatile flavor compounds, thereby contributing to the sensory attributes of fermented coffee (Bastian et al., 2021). Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated that peptide accumulation in LAB can be influenced by the availability of carbohydrates and the presence of phenolic compounds two factors that vary with fruit maturity (Zhao et al., 2021; Padonou et al., 2022). In this context, the presence of the small peptide FruLeuIle in strains associated with mature cherries could be interpreted as a biosignature of substrate-driven metabolic specialization. This further underscores the role of plant–microbe coevolution and ecological selection in shaping the metabolic repertoire of LAB, with direct implications for the enhancement of coffee flavor and quality through fermentation. This supports the hypothesis that plant-microbe cohabitation in niche environments fosters functional diversification in microbial metabolism (Junkins et al., 2022).

Moreover, the detection of lincomycin in the CFS of B10 and B17 from Caturra variety yellow and red mature cherries, suggests a possible case of metabolically induced antibiotic production or the synthesis of structurally related analogs. While lincomycin is traditionally produced by Streptomyces spp., recent studies have highlighted the metabolic plasticity of LAB in response to complex plant-derived substrates, particularly under selective ecological pressures (Molina et al., 2025). The nutrient-rich composition of mature coffee cherries characterized by high concentrations of fermentable sugars, free amino acids, and polyphenolic compounds (Hall et al., 2022), may serve as biochemical cues that activate cryptic or horizontally acquired biosynthetic pathways. Such pathways could facilitate the production of antimicrobial compounds, conferring a competitive advantage by modulating microbial community dynamics during fermentation (Bastian et al., 2021). Nonetheless, the consistent detection of such metabolites in CFS derived from mature cherry fermentations underscores the potential for substrate-induced metabolic specialization in LAB, with implications for both microbial ecology and the development of bioactive compounds in coffee (Zhao et al., 2021; Padonou et al., 2022).

3.3 Vibrational signatures of LAB-derived metabolites as a perspective on the modulation of aroma and functionality through FTIR spectroscopy

The FTIR spectra of the extracellular metabolites produced by the LAB strains (Figure 3) were significantly different from the un-inoculated and lyophilized MRS broth in certain spectral regions, demonstrating biochemical changes caused by fermentation.

Figure 3. FTIR spectral profiles of LAB-derived extracellular metabolites compared to uninoculated MRS medium.

In the region 690–1,000 cm–1 (fingerprint for carbohydrates), the bands at 698–808 cm–1 in the free cell supernatant of the samples, which were absent in the MRS medium spectrum, suggest the presence of new compounds, possibly polysaccharides or proteins. The strong bands in the region of 929–1,000 cm–1, common to all samples, correspond to the C-O-C and C-O vibrations characteristic of polysaccharides (β-glycosidic bond) or phosphates, suggesting that the microbial cells did not fully metabolize the carbohydrate components present in the broth (Chen et al., 2025; Gieroba et al., 2023; Jastrzebski et al., 2011).

In the region between 1,000 and 1,372 cm–1, polysaccharides were confirmed by C-O stretching vibrations in the range of 1,000–1,100 cm–1, while CO deformation in condensed COC structures was highlighted in the range of 1,112–1,164 cm–1, which are specific to carbohydrates and/or peptides (Xu et al., 2013; Khadivi et al., 2022). Only for samples B6, B10, and B19 was a band at 1,164 cm–1, suggesting the presence of distinct extracellular polysaccharides with a more complex structure (polysaccharides with a higher degree of branching or specific types of glycosidic linkages), which differentiates them from the other samples (Liu et al., 2021). For samples B9 and B17, a specific band at wavenumbers 1,180 cm–1 and 1,265 cm–1 was identified, which can be attributed to phenolic C-O stretching (Agatonovic-Kustrin et al., 2020). In the case of B17 sample, a band at 1,289 cm–1 was identified and attributed to the C-O stretching vibration of the amide group and the C–N stretching vibration in the pyrrolidine ring (Yang et al., 1997; Fu et al., 1994; Li et al., 2013; Jeevaratnam et al., 2015). The changes in the region 1,343–1,372 cm–1, where additional bands are detected around 1,357 cm–1 for samples B9 and B17, are attributed to the symmetric O-C-O vibration (Chico-Mesa et al., 2025).

The amide (Amide I and II) and aromatic regions are between 1,400 and 1,700 cm–1. The bands in the range of 1,470–1,570 cm–1 indicate the presence of carboxyl and amide groups (Chatterley et al., 2022; Ji et al., 2020). The deformation vibrations of the CH2 or CH3 group, which are unique to lipids, but found also in proteins, were responsible for the absorption maxima that were seen at wavenumbers 1,402 and 1,451 cm–1 in the uninoculated media. The O–H bending vibration of carboxylic acids can be shown by the peak at 1,402 cm–1 (Yang et al., 2025). Additionally, the intense band around the value of 1,562–1,579 cm–1 suggests the presence of amide-type vibrations (Amide II), characteristic of proteins or extracellular peptide compounds (Ghafoor and Butt, 2025). The presence of the band at 1,592 cm–1, characteristic of C = C vibrations in aromatic rings for samples B6, B10, and B19, indicates the presence of aromatic amino acids such as phenylalanine, tyrosine, or tryptophan, or phenolic compounds (Amber et al., 2023; Tomasetig et al., 2024). The bands in the range of 1,600–1,700 cm–1 are associated with C = O vibrations of the amide type (Amide I), highlighting the presence of extracellular proteins or peptides (Sadat and Joye, 2020). Only for sample B9 was a specific band identified at a wavenumber of 1,655 cm–1, associated with an extracellular protein structure with a possible α-helix type structure (Barth, 2007; Sizeland et al., 2018).

Bands in the range of 2,923–2,933 cm–1, attributed to C-H stretching vibrations, suggest the existence of lipid and carbohydrate structures (Portaccio et al., 2023). A broad absorption around the values of 3,200–3,300 cm–1 (amide A) was present in both free cell supernatant samples and the uninoculated medium, but slight shifts in the peaks indicate a change in the content of extracellular polysaccharides or glycoproteins (Synytsya and Novak, 2014; Das et al., 2021; Tatulian, 2019). FTIR spectrum analysis confirms that the lactic acid bacteria strains secreted extracellular metabolites into the culture medium, particularly polysaccharides and proteins, thereby altering the initial composition of the MRS medium.

The evaluation of FTIR spectra showed that, during fermentation, LAB strains actively release extracellular polysaccharides, peptides, proteins, and phenolic and aromatic compounds. These biochemical changes distinguish the fermented matrix from the original MRS environment and demonstrate the distinct metabolic adaptations of the bacteria. Samples B6, B10, B17, and B19 showed unique markers in the individual spectrum with different aromatic compounds or structural polysaccharides, highlighting their ability to control functional bioactivity, texture, and aroma release under coffee fermentation conditions.

3.4 Metabolic pathway enrichment profiles of coffee-origin LAB strains across Typica, Caturra Yellow, and Caturra Red varieties

3.4.1 Metabolic enrichment profiles of Typica-derived strains (B3 and B6)

The metabolic pathway enrichment analysis of samples B3 and B6 revealed pronounced activation of aromatic amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism pathways (Figure 4). Both strains showed elevated phenylalanine and tryptophan biosynthesis and metabolism, precursors of phenols, indoles, and other flavor-active compounds (Evangelista et al., 2014), suggesting their potential to enhance sensory profiles during coffee pulp fermentation. Enrichment in novobiocin biosynthesis and tyrosine metabolism further indicated active secondary metabolism, possibly contributing to bioactivity and functional properties of the fermented matrix (Supplementary Figure 2). Notably, B6 uniquely exhibited significant enrichment in galactose metabolism, pointing to a superior capacity for carbohydrate catabolism that could modulate fermentation kinetics and direct metabolic flux toward flavor precursors (Li et al., 2021). Both strains also showed enrichment in one-carbon metabolism via folate and sulfur amino acid pathways, supporting roles in methylation reactions and sulfur-containing volatile production, key to flavor complexity and oxidative stability (Liu et al., 2008). Together, these results suggest that B3 and B6 drive flavor development through aromatic amino acid and sulfur metabolism, with B6 emerging as a particularly promising candidate due to its expanded sugar metabolism and potential to improve both flavor quality and functional value in coffee by-products (Hall et al., 2022; Todhanakasem et al., 2024).

Figure 4. Metabolite set enrichment overview associated with LAB strains isolated from C. arabica var. Typica (B3 and B6). Enrichment bar plots illustrate the significantly overrepresented chemical classes among metabolites produced by each strain. The x-axis denotes the enrichment ratio, reflecting the degree of overrepresentation relative to background levels, while bar coloration corresponds to statistical significance (p-value), with red indicating the highest significance and yellow the lowest.

3.4.2 Metabolic enrichment profiles of Caturra Yellow-derived strains (B9 and B10)

The metabolite set enrichment analysis of B9 and B10 revealed distinct but overlapping metabolic reprogramming (Figure 5). Both strains showed strong enrichment in phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis and phenylalanine metabolism, highlighting upregulation of aromatic amino acid pathways that provide precursors for alkaloids and phenolic compounds linked to stress adaptation and signaling (Dodd et al., 2017). B9 exhibited particularly strong enrichment in tryptophan metabolism (Supplementary Figure 3), suggesting elevated production of indole-derived compounds with roles in plant defense and growth regulation (Tennoune et al., 2022). Both strains also showed enrichment in ubiquinone and terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis, as well as moderate activation of cysteine, methionine, and galactose metabolism, pointing to adjustments in redox homeostasis and energy metabolism (Paul et al., 2018). While B9 displayed stronger activation of aromatic amino acid and tryptophan pathways, B10 (L. plantarum) exhibited a broader but less intense enrichment profile, potentially reflecting different stress responses and niche adaptations. Pathway mapping for B10 was limited by the smaller number of annotated metabolites. Overall, these findings underscore strain-specific metabolic strategies of coffee-associated LAB, shaped by adaptation to the biochemical challenges of coffee fermentation.

Figure 5. Metabolite set enrichment overview associated with LAB strains isolated from C. arabica var. Caturra Yellow (B9 and B10). Enrichment bar plots illustrate the significantly overrepresented chemical classes among metabolites produced by each strain. The x-axis denotes the enrichment ratio, reflecting the degree of overrepresentation relative to background levels, while bar coloration corresponds to statistical significance (p-value), with red indicating the highest significance and yellow the lowest.

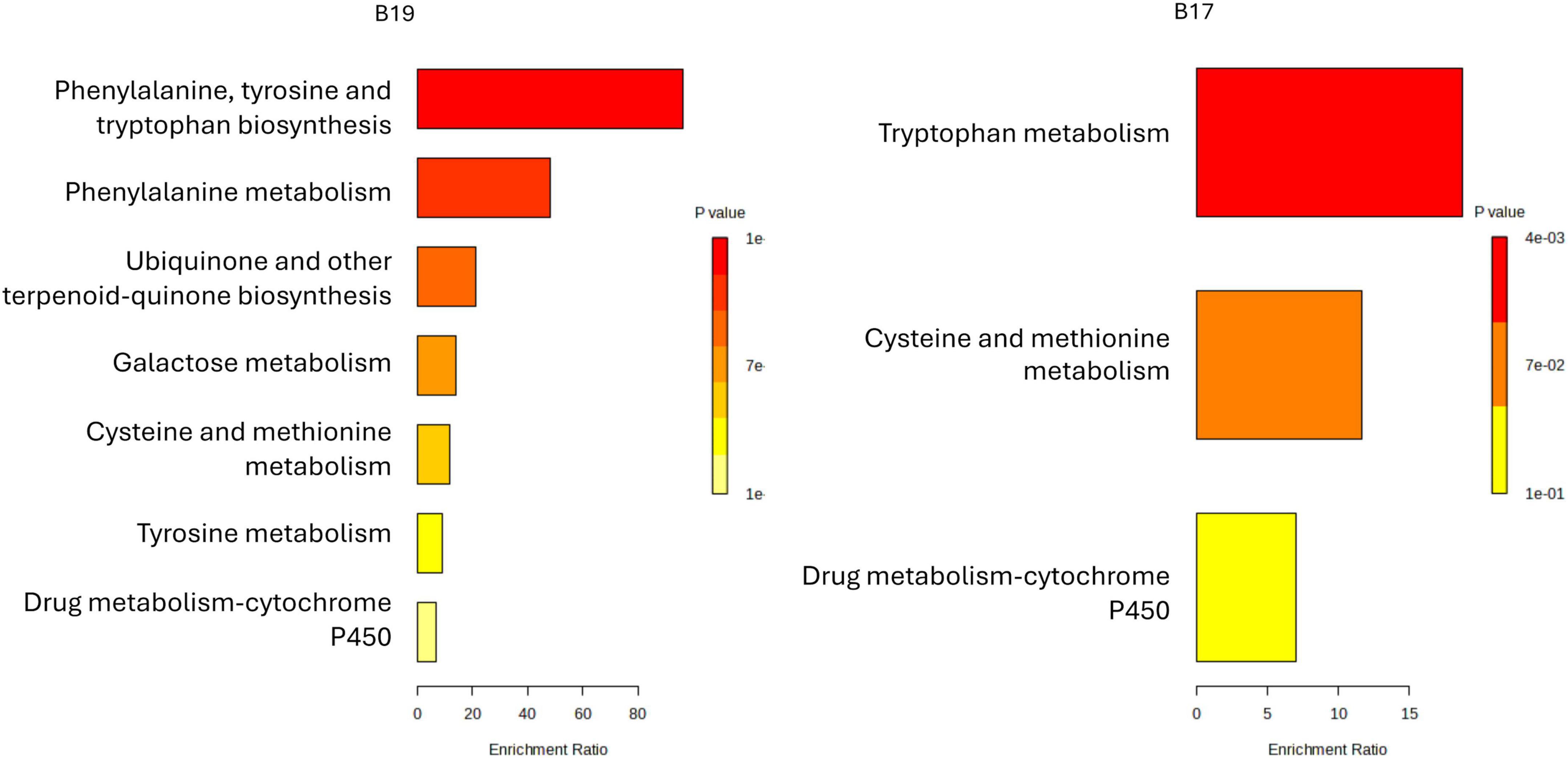

3.4.3 Metabolic enrichment profiles of Caturra Red-derived strains (B17 and B19)

The metabolite enrichment profiles of B17 (L. pentosus) and B19 (W. confusa), reveal distinct metabolic strategies that align with their ecological roles and potential functional applications in coffee fermentation (Figure 6). B17 demonstrates significant enrichment in pathways associated with phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis, as well as phenylalanine metabolism, ubiquinone and other terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis, and galactose metabolism. This broad enrichment suggests that B17 possesses an active aromatic amino acid metabolism capable of generating precursor compounds for flavor-active phenolics and volatiles (Maeda and Dudareva, 2012). The engagement of galactose metabolism is particularly relevant, considering that coffee mucilage contains substantial amounts of galactose-rich polysaccharides (de Soares da Silva et al., 2023), indicating B17 adaptability in utilizing coffee-derived sugars during fermentation. Moreover, the activation of ubiquinone and terpenoid-quinone biosynthesis in B17 implies a heightened electron transport and redox balancing capacity, which could improve resilience under oxygen-variable conditions typical of spontaneous coffee fermentations (De Bruyn et al., 2016). This redox activity may also indirectly influence the fermentation’s microbial ecology and oxidative processes involved in flavor development. Nonetheless, similar with the sample B10, the limited number of compounds mapped to known metabolic pathways precluded the generation of a pathway profile for B17. In contrast, B19 exhibits a more focused metabolic enrichment, with dominant activation of tryptophan metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, and drug metabolism (Figure 6 and Supplementary Figure 4). The sulfur amino acid metabolism reflects an adaptive stress response mechanism, enabling Lactobacillus sp. to manage oxidative stress and thrive in the challenging conditions of fermentation (Papadimitriou et al., 2016). Additionally, cytochrome P450-related activity in B19 points to its role in detoxification and secondary metabolism, which can support fermentation stability by neutralizing inhibitory compounds (Wszołek, 2022). From a functional perspective, these metabolic signatures suggest B17 (L. pentosus) is well-suited for early-stage fermentation, where its carbohydrate catabolism, redox modulation, and aromatic amino acid metabolism can actively shape flavor and microbial succession. This aligns with previous reports highlighting Weissella spp. as early colonizers in coffee and cacao fermentations, contributing to initial sugar breakdown and acid production (De Bruyn et al., 2016). In contrast, B19 (W. confusa) appears more adapted to late-stage fermentation, where its stress tolerance and detoxification systems maintain process stability and microbial homeostasis. L. plantarum is known for its robustness and versatile metabolism in diverse fermentation systems, including vegetable and cereal fermentations (Filannino et al., 2018). Considering the coffee origin of both strains, leveraging their complementary metabolic traits could enhance the quality and consistency of coffee fermentation. Specifically, B17 ability to metabolize galactose and activate aromatic pathways positions it as a driver of early biochemical transformations that define coffee sensory profile, while B19 could ensure microbial robustness and redox balance in later stages. Therefore, a sequential or co-culture application of B17 and B19 offers a promising strategy for optimizing coffee fermentation, improving both flavor complexity and process reliability.

Figure 6. Metabolite set enrichment overview associated with LAB strains isolated from C. arabica var. Caturra Red (B17 and B19). Enrichment bar plots illustrate the significantly overrepresented chemical classes among metabolites produced by each strain. The x-axis denotes the enrichment ratio, reflecting the degree of overrepresentation relative to background levels, while bar coloration corresponds to statistical significance (p-value), with red indicating the highest significance and yellow the lowest.

3.5 Strain-specific metabolite enrichment revealed by pathway analysis

The metabolomic profiles of the CFS from six bacterial strains (B3, B6, B9, B10, B17, and B19) revealed distinct enrichment patterns based on metabolite set analysis (Figure 7). Notably, the strains could be divided into two main species-specific metabolic profiles:

Figure 7. Enriched metabolic pathways based on KEGG analysis detected in LAB isolates. Enriched classes include harmala alkaloids, indoles and derivatives, isoflavonoids, organooxygen compounds, and fatty acids, with strain-specific differences in enrichment ratios and significance levels (p-values). These results highlight the metabolic diversity and functional specialization of LAB strains in coffee fermentation.

3.5.1 Lactiplantibacillus strains enrich harmala alkaloids, isoflavonoids, and indole derivatives

CFS extracted from B3, B6, B9, B10, and B17 exhibited significant enrichment in harmala alkaloids, isoflavonoids, and indole derivatives (Figure 7). LAB associated with Coffea arabica may either produce these compounds as part of their secondary metabolism or possess specific metabolic pathways to tolerate or transform alkaloid compounds. Similar observations have been reported in microbial communities inhabiting alkaloid-rich environments, such as cocoa fermentations, where the presence of alkaloids acts as a selective pressure, shaping microbial community structure and function (Picon et al., 2024). This finding suggests a potential metabolic adaptation of the LAB strains to the chemical environment of coffee cherries, known to be rich in alkaloids and phenolic compounds. Among them, B9 showed a distinctive signature in aromatic amino acid metabolism (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan) but still followed the general trend of Lactobacillus strains producing secondary metabolites. The strong enrichment of β-carboline derivatives (harmala alkaloids) suggests an active metabolism of tryptophan. Lactobacillus species are known to metabolize tryptophan into bioactive compounds such as indole-3-lactic acid, indole-3-acetic acid, and potentially β-carbolines via microbial secondary metabolism (Hou et al., 2023). This ability could enhance the functional properties of fermented coffee by producing neuroactive and antioxidant metabolites. Moreover, the detection of isoflavonoid derivatives is consistent with Lactobacillus strains ability to hydrolyze glycosides into aglycones via β-glucosidase activities (Strahsburger et al., 2017). Such bioconversions not only improve the bioavailability of polyphenols but also contribute to the sensory characteristics of the fermented product. The metabolic signatures of B9 emphasized the metabolism of phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan, pointing toward a highly active aromatic amino acid biosynthesis and catabolism pathway. The secondary metabolites enriched by Lactobacillus strains, particularly indole derivatives and isoflavonoids, are likely to contribute to the development of fruity, floral, and sweet aromatic profiles in fermented coffee. In addition, β-carbolines have been reported to impart subtle bitterness and complexity, potentially enhancing mouthfeel and the perceived body of the coffee beverage.

3.5.2 Distinct metabolic signature in Weissella strain

The W. confusa strain CATV17 (sample B19) exhibited a different metabolic enrichment pattern (Figure 7). The enrichment pathway was focused on benzene derivatives and carboxylic acids rather than secondary metabolites like harmala alkaloids or indoles. Weissella species are known for their proteolytic activities and the ability to metabolize simple aromatic structures derived from amino acids or plant phenolics (Fusco et al., 2015). The limited presence of harmala alkaloids and lower enrichment ratios for complex secondary metabolites suggest a metabolism more oriented toward basic energy acquisition and simple aromatic transformations, rather than elaborate secondary metabolism. The metabolic profile of B19 suggests a potential contribution to acidity and fresh, clean flavors in fermented coffee, dominated by organic acid production and simple aromatic transformations. However, the lack of enriched complex secondary metabolites indicates that Weissella alone might not provide the same degree of aromatic complexity (e.g., floral, fruity notes) compared to Lactiplantibacillus strains.

3.5.3 Minor but conserved pathways across strains

All strains exhibited low yet measurable enrichment in pathways related to fatty acyl metabolism, organooxygen compounds, and naphthalene degradation, likely reflecting partial catabolism of plant-derived aromatics from the coffee pulp (Figure 7). The strain-specific metabolomic profiles observed here are consistent with previous reports showing that microbial secondary metabolism is highly strain-dependent and shaped by environmental factors, particularly the phytochemical composition of the host plant (Lippolis et al., 2023). Notably, the enrichment of isoflavonoids across strains suggests a conserved metabolic response to phenolic-rich substrates, corroborating evidence from fermented food systems where LAB mediate the biotransformation of dietary phenolics into bioactive metabolites (Li et al., 2021).

These results highlight the complex metabolic interplay between LAB and their C. arabica niches, indicating that adaptation to distinct coffee varieties drives functional specialization at the metabolomic level. Such specialization likely contributes not only to microbial ecological fitness but also to potential applications in food fermentation and probiotic functionality. In contrast, Weissella strains, characterized by organic acid and simple aromatic metabolite production, may enhance acidity, brightness, and overall cleanliness of the beverage profile.

From an applied perspective, strategic co-cultivation of selected lactobacilli and Weissella strains could balance aromatic depth with vibrant acidity, generating a more complex and consumer-preferred sensory profile. Future studies integrating sensory evaluation and volatile compound analysis will be essential to directly link metabolomic outputs with flavor perception. Such integrative studies could ultimately lead to the development of microbial consortia as functional bio-tools for customized fermentation and differentiated specialty coffee products.

3.6 Polyphenol and flavonoid variability in LAB strains

Total phenolic content (TPC, mg GAE/L) and flavonoids (TFC, mg QE/L) were measured in the CFS of the six LAB strains (B3, B6, B9, B10, B17, and B19). The findings revealed significant differences between the strains, suggesting a high degree of functional diversity in their ability to produce or accumulate bioactive metabolites with antioxidant functions. To reduce the interference of compounds from the culture medium, the extracts were obtained through liquid-liquid extraction with ethyl acetate, a method that excludes amino acids and major polar metabolites (Filannino et al., 2014). The analysis of the negative control (MRS without inoculation) showed a signal below the detection limit, confirming that the organic fraction predominantly contains metabolites generated by LAB, and not culture medium-derived compounds.

From Figure 8A, it can be observed that B10 and B3 exhibited the highest (42.44 ± 3.06 mg GAE/L and 29.61 ± 1.06, respectively), while B19 the lowest (13.32 ± 0.64 mg GAE/L) phenolic content. Multiple statistically significant differences have been recorded between almost all samples, especially, B10 and B3 are significantly richer in polyphenols compared to the other samples (p < 0.0001, p < 0.01).

Figure 8. Total polyphenol and flavonoid content in cell-free supernatants of LAB isolates. (A) Polyphenols (mg gallic acid equivalents/L, mg GAE/L). (B) Flavonoids (mg quercetin equivalents/L, mg QE/L). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical differences among strains were determined by one-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests (p-values shown).

In the case of the total flavonoid content (Figure 8B), sample B3 had the highest flavonoid content (1.013 ± 0.184 mg QE/L), significantly different from all the other samples (p < 0.01, p < 0.001, etc.). The rest of the samples (B6, B9, B10, B17, B19) had lower levels, ranging from 0.551 ± 0.085 mg QE/L (B9) to 0.794 ± 0.063 mg QE/L (B19), with no significant differences between them. The experimental data on the TPC and TFC met the conditions for applying the ANOVA test, as the Brown–Forsythe test indicated homogeneity of variances (p > 0.05), and the normality of the residuals was confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test, with p-values > 0.05 for both data sets.

The TPC and TFC results provide additional experimental support for the claim that LAB strains isolated from C. arabica cherries possess distinct metabolic signatures correlated with their phytochemical niches. Samples B3 and B10 demonstrate a superior capacity to biosynthesize or accumulate phenolic compounds and flavonoids. This is consistent with the previously observed enrichment in the metabolism of aromatic amino acids (biosynthesized by microorganisms or produced by the degradation of protein content in the MRS medium) and in the biosynthesis of compounds derived from tryptophan, which serve as precursors for volatile phenols and flavonoid derivatives (Okoye et al., 2023). The highest concentration of flavonoids and polyphenols was found in the CFS of strain B3, indicating that this sample could considerably stabilize volatile compounds, enhancing their aromatic complexity and endurance (Farag et al., 2022; Aloo et al., 2024). Its antioxidant properties could potentially be useful. CFS from strains B6, B9, B17, and B19 can maintain the acidity and freshness of coffee through alternative metabolic processes like the production of organic acid or peptides, even in the case of a decreased phenolic concentration.

It should be noted, however, that the TPC and TFC analyses were limited to the ethyl acetate-extractable fraction, which excludes polar metabolites and amino acids. Consequently, the results may not capture the full spectrum of bioactive compounds produced by the LAB strains, and additional analyses of the polar fraction would be necessary to obtain a more complete metabolic profile. Nevertheless, the observed variability among strains, with B3 and B10 exhibiting the highest levels of phenolic compounds (p < 0.0001), aligns with the previously observed enrichment of metabolic pathways and underscores the role of the plant substrate in shaping the functional and aromatic properties of LAB strains (da Silva Vale et al., 2024; Abbaspour, 2024).

4 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that LAB strains isolated from Coffea arabica cherries exhibit distinct, strain-specific metabolic signatures shaped by their ecological niche. Lactiplantibacillus strains were enriched in secondary metabolites such as harmala alkaloids and aromatic amino acid derivatives, contributing to fruity, floral, and sweet notes, while Weissella confusa showed higher levels of organic acids and simple aromatics, supporting acidity and brightness. FTIR analysis confirmed molecular changes in the fermentation matrix, including the release of extracellular polysaccharides, proteins, and phenolic compounds, with strain-specific spectral features suggesting functional contributions to texture, bioactivity, and flavor modulation. These findings highlight the dual role of de novo biosynthesis and enzymatic hydrolysis of complex substrates in shaping the extracellular metabolite pool, emphasizing enzymatic remodeling as a key mechanism in coffee fermentation. The study provides a foundation for leveraging the natural diversity of LAB strains to guide targeted fermentation strategies, enabling producers to balance aromatic richness, acidity, and freshness to enhance sensory quality and product differentiation. Future work should combine targeted metabolomics, genomic analyses, and sensory evaluation to confirm metabolite origins, elucidate enzymatic mechanisms, and directly link metabolomic profiles with flavor attributes. Such integrative approaches will support the development of next-generation microbial consortia for precision fermentation and high-value specialty coffee production.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. IM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. RP: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MC: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. GT: Validation, Supervision, Visualization, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Universidad Técnica del Norte under grant number No. 9674/2024 awarded to GT. Additionally, GT received partial support through the Scientific Visitor Fellowship Grant No. 147/2025 from the Research Institute of the University of Bucharest (ICUB), Romania. In addition, this manuscript was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the Smart Growth, Digitization and Financial Instruments Program (PoCIDIF), call PCIDIF/144_P1/OP1/RSO1.1/PCIDIF_A3, Project Smis Number 309287, acronym METROFOOD-RO Evolve.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Universidad Técnica del Norte for funding this research. We would also like to sincerely thank M. Cevallos and I. Sanchez for their valuable assistance with the collection of Coffea arabica cherries, which was essential for the successful completion of this study.

Conflict of interest

GM, RP were employed by Blue Screen SRL.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1697280/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^https://systemsomicslab.github.io/compms/msdial/main.html#MSP, accessed 15 April 2025

2. ^http://www.metaboanalyst.ca/, accessed on 22 April 2025

3. ^http://www.kegg.jp/, accessed on 20 May 2025

References

Abbaspour, N. (2024). Fermentation’s pivotal role in shaping the future of plant-based foods: An integrative review of fermentation processes and their impact on sensory and health benefits. Appl. Food Res. 4:100468. doi: 10.1016/j.afres.2024.100468

Agatonovic-Kustrin, S., Ramenskaya, G., Kustrin, E., Ortakand, D. B., and Morton, D. W. (2020). A new integrated HPTLC - ATR/FTIR approach in marine algae bioprofiling. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. Anal. 189:113488. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113488

Aloo, O. S., Gemechu, F. G., Oh, H. J., Kilel, E. C., Chelliah, R., Gonfa, G., et al. (2024). Harnessing fermentation for sustainable beverage production: A tool for improving the nutritional quality of coffee bean and valorizing coffee byproducts. Biocatal. Agricultural Biotechnol. 59:103263. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103263

Amber, A., Nawaz, H., Bhatti, H. N., and Mushtaq, Z. (2023). Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for the characterization of different anatomical subtypes of oral cavity cancer. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Therapy 42:103607. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2023.103607

Barth, A. (2007). Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerget. 1767, 1073–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.06.004

Bastian, F., Hutabarat, O. S., Dirpan, A., Nainu, F., Harapan, H., Emran, T. B., et al. (2021). From plantation to cup: Changes in bioactive compounds during coffee processing. Foods 10:2827. doi: 10.3390/foods10112827

Begley, M., Hill, C., and Gahan, C. G. (2006). Bile salt hydrolase activity in probiotics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1729–1738. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.1729-1738.2006

Bernardes, P. C. (2024). Microbial ecology and fermentation of Coffea canephora. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 4:1377226. doi: 10.3389/frfst.2024.1377226

Bonnarme, P., Psoni, L., and Spinnler, H. E. (2000). Diversity of L-methionine catabolism pathways in cheese-ripening bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 5514–5517. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5514-5517.2000

Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J., Rosen, M. J., Han, A. W., Johnson, A. J. A., and Holmes, S. P. (2020). DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869

Chatterley, A. S., Laity, P., Holland, C., Weidner, T., Woutersen, S., and Giubertoni, G. (2022). Broadband multidimensional spectroscopy identifies the amide II vibrations in silkworm films. Molecules 27:6275. doi: 10.3390/molecules27196275

Chen, M., Zhang, M., Yang, R., Wang, X., Du, L., Yue, Y., et al. (2025). Structural analysis and prebiotic properties of the polysaccharides produced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum YT013. Food Chem. 28:102600. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102600

Chico-Mesa, L., Rodes, A., Arán-Ais, R. M., and Herrero, E. (2025). Insights into catalytic activity and selectivity of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural oxidation on gold single-crystal electrodes. Nat. Commun. 16:3349. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-58696-4

Corbu, V. M., Gheorghe-Barbu, I., Marinas, I. C., Avramescu, S. M., Pecete, I., Geana, E. I., et al. (2022). Eco-friendly solution based on Rosmarinus officinalis hydro-alcoholic extract to prevent biodeterioration of cultural heritage objects and buildings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23:11463. doi: 10.3390/ijms231911463

da Silva Vale, A., Pereira, C. M. T., De Dea Lindner, J., Rodrigues, L. R. S., El Kadri, N. K., et al. (2024). Exploring microbial influence on flavor development during coffee processing in humid subtropical climate through metagenetic–metabolomics analysis. Foods 13:1871. doi: 10.3390/foods13121871

da Silva Vale, A., Pereira, C. M. T., De Dea Lindner, J., Rodrigues, L. R. S., Kadri, N. K. E., Pagnoncelli, M. G. B., et al. (2024). Exploring microbial influence on flavor development during coffee processing in humid subtropical climate through metagenetic–metabolomics analysis. Foods 13:1871. doi: 10.3390/foods13121871

Das, T., Harshey, A., Srivastava, A., Nigam, K., Yadav, V. K., Sharma, K., et al. (2021). Analysis of the ex-vivo transformation of semen, saliva and urine as they dry out using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and chemometric approach. Sci. Rep. 11:11855. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91009-5

De Bruyn, F., Zhang, S. J., Pothakos, V., Torres, J., Lambot, C., Moroni, A. V., et al. (2016). Exploring the impacts of postharvest processing on the microbiota and metabolite profiles during green coffee bean production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e02398-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02398-16

de Carvalho Neto, D. P., de Melo Pereira, G. V., Finco, A. M. O., Letti, L. A. J., da Silva, B. J. G., Vandenberghe, L. P. S., et al. (2018). Efficient coffee beans mucilage layer removal using lactic acid fermentation in a stirred-tank bioreactor: Kinetic, metabolic and sensorial studies. Food Biosci. 26, 80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2018.09.004

de Melo Pereira, G. V., de Carvalho Neto, D. P., Pedroni Medeiros, A. B., Soccol, V. T., Neto, E., Woiciechowski, A. L., et al. (2016). Potential of lactic acid bacteria to improve the fermentation and quality of coffee during on-farm processing. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 1689–1695. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.13142

de Soares, da Silva, M. C., Veloso, T. G. R., Brioschi Junior, D., Bullergahn, V. B., da Luz, J. M. R., et al. (2023). Bacterial community and sensory quality from coffee are affected along fermentation under carbonic maceration. Food Chem. Adv. 3:100554. doi: 10.1016/j.focha.2023.100554

Dodd, D., Spitzer, M. H., Van Treuren, W., Merrill, B. D., Hryckowian, A. J., Higginbottom, S. K., et al. (2017). A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551, 648–652. doi: 10.1038/nature24661

Duque-Buitrago, L. F., Calderón-Gaviria, K. D., Torres-Valenzuela, L. S., Sánchez-Tamayo, M. I., and Plaza-Dorado, J. L. (2025). Modulating coffee fermentation quality using microbial inoculums from coffee by-products for sustainable practices in smallholder coffee production. Sustainability 17:1781. doi: 10.3390/su17051781

Evangelista, S. R., Silva, C. F., Miguel, M. G. C. P., Cordeiro, C. S., Pinheiro, A. C. M., Duarte, W. F., et al. (2014). Inoculation of starter cultures in a semi-dry coffee (Coffea arabica) fermentation process. Food Microbiol. 44, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.05.015

Farag, M. A., Zayed, A., Sallam, I. E., Abdelwareth, A., and Wessjohann, L. A. (2022). Metabolomics-based approach for coffee beverage improvement in the context of processing, brewing methods, and quality attributes. Foods 11:864. doi: 10.3390/foods11060864

Filannino, P., Di Cagno, R., and Gobbetti, M. (2018). Metabolic and functional paths of lactic acid bacteria in plant foods: Get out of the labyrinth. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 49, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.07.016

Filannino, P., Gobbetti, M., De Angelis, M., and Di Cagno, R. (2014). Hydroxycinnamic acids used as external acceptors of electrons: An energetic advantage for strictly heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80:24. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02413-14

Fu, F. N., Deoliveira, D. B., Trumble, W. R., Sarkar, H. K., and Singh, B. R. (1994). Secondary structure estimation of proteins using the amide iii region of fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: Application to analyze calcium-binding-induced structural changes in calsequestrin. Appl. Spectroscopy 48, 1432–1441. doi: 10.1366/0003702944028065

Fusco, V., Quero, G. M., Cho, G. S., Kabisch, J., Meske, D., Neve, H., et al. (2015). The genus Weissella: Taxonomy, ecology and biotechnological potential. Front. Microbiol. 6:155. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00155

Gao, Y., Hou, L., Gao, J., Li, D., Tian, Z., Fan, B., et al. (2021). Metabolomics approaches for the comprehensive evaluation of fermented foods: A review. Foods 10:2294. doi: 10.3390/foods10102294

Ghafoor, H., and Butt, M. S. (2025). Synthesis and characterization of clove/gelatin coated silk sutures for surgical site infection and wound healing. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 36:36. doi: 10.1007/s10856-025-06886-3

Gieroba, B., Kalisz, G., Krysa, M., Khalavka, M., and Przekora, A. (2023). Application of vibrational spectroscopic techniques in the study of the natural polysaccharides and their cross-linking process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24:2630. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032630

Haile, M., and Kang, W. H. (2019). The role of microbes in coffee fermentation and their impact on coffee quality. J. Food Qual. 12:4836709. doi: 10.1155/2019/4836709

Hall, R. D., Trevisan, F., and de Vos, R. C. H. (2022). Coffee berry and green bean chemistry – Opportunities for improving cup quality and crop circularity. Food Res. Int. 151:110825. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110825

Hou, Y., Li, J., and Ying, S. (2023). Tryptophan metabolism and gut microbiota: A novel regulatory axis integrating the microbiome. Immun. Cancer Metab. 13:1166. doi: 10.3390/metabo13111166

Hu, F., Yu, H., Fu, X., Li, Z., Dong, W., Li, G., et al. (2025). Characterization of volatile compounds and microbial diversity of Arabica coffee in honey processing method based on different mucilage retention treatments. Food Chem. 25:102251. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102251

Jastrzebski, W., Sitarz, M., Rokita, M., and Bulat, K. (2011). Infrared spectroscopy of different phosphates structures. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectroscopy 79, 722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.08.044

Jeevaratnam, K., Vidhyasagar, V., Agaliya, P. J., Saraniya, A., and Umaiyaparvathy, M. (2015). Characterization of an antibacterial compound, 2-hydroxyl indole-3-propanamide, produced by lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented batter. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 177, 137–147. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1733-9

Ji, Y., Yang, X., Ji, Z., Zhu, L., Ma, N., Chen, D., et al. (2020). DFT-Calculated IR spectrum amide I, II, and III band contributions of N-methylacetamide fine components. ACS Omega 15, 8572–8578. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b04421

Junkins, E. N., McWhirter, J. B., McCall, L. I., and Stevenson, B. S. (2022). Environmental structure impacts microbial composition and secondary metabolism. ISME Commun. 2:15. doi: 10.1038/s43705-022-00097-5

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y., and Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. (2024). KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53:gkae909. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae909

Khadivi, P., Salami-Kalajahi, M., Roghani-Mamaqani, H., and Sofla, R. L. M. (2022). Polydimethylsiloxane-based polyurethane/cellulose nanocrystal nanocomposites: From structural properties toward cytotoxicity. Silicon 14, 1695–1703. doi: 10.1007/s12633-021-00970-3

Kim, I. S. (2021). Current perspectives on the beneficial effects of Soybean isoflavones and their metabolites for humans. Antioxidants 10:1064. doi: 10.3390/antiox10071064

Kim, S. G., Abbas, A., and Moon, G. S. (2024). Improved functions of fermented coffee by lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Sci. 14:7596. doi: 10.3390/app14177596

Kishimoto, S., Sato, M., Tsunematsu, Y., and Watanabe, K. (2016). Evaluation of biosynthetic pathway and engineered biosynthesis of alkaloids. Molecules 21:1078. doi: 10.3390/molecules21081078

Li, G., Chen, Z., Chen, N., and Xu, Q. (2020). Enhancing the efficiency of L-tyrosine by repeated batch fermentation. Bioengineered 11, 852–861. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2020.1804177

Li, R., Wang, H., Wang, W., and Ye, Y. (2013). Simultaneous radiation induced graft polymerization of N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone onto polypropylene non-woven fabric for improvement of blood compatibility. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 88, 65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2013.03.013

Li, T., Jiang, T., Liu, N., Wu, C., Xu, H., and Lei, H. (2021). Biotransformation of phenolic profiles and improvement of antioxidant capacities in jujube juice by select lactic acid bacteria. Food Chem. 339:127859. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127859

Lippolis, T., Cofano, M., Caponio, G. R., De Nunzio, V., and Notarnicola, M. (2023). Bioaccessibility and bioavailability of diet polyphenols and their modulation of gut microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24:3813. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043813

Liu, M., Nauta, A., Francke, C., and Siezen, R. J. (2008). Comparative genomics of enzymes in flavor-forming pathways from amino acids in lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 4590–4600. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00150-08

Liu, X., Renard, C. M. G. C., Bureau, S., and Le Bourvellec, C. (2021). Revisiting the contribution of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy to characterize plant cell wall polysaccharides. Carbohydrate Polym. 262:117935. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117935

Maeda, H., and Dudareva, N. (2012). The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino Acid biosynthesis in plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 73–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439

Martino, M. E., Bayjanov, J. R., Caffrey, B. E., Wels, M., Joncour, P., Hughes, S., et al. (2016). Nomadic lifestyle of Lactobacillus plantarum revealed by comparative genomics of 54 strains isolated from different habitats. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 4974–4989. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13455

Matsui, D., Sugimoto, M., and Masuda, T. (2018). Microbial metabolism of tryptophan to β-carbolines in lactic acid bacteria. Microbiol. Res. 21, 42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.03.005

Mengesha, D., Retta, N., Woldemariam, H. W., and Getachew, P. (2024). Changes in biochemical composition of Ethiopian Coffee arabica with growing region and traditional roasting. Front. Nutr. 11:1390515. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1390515

Mihai, R. A., Ortiz-Pillajo, D. C., Iturralde-Proaño, K. M., Vinueza-Pullotasig, M. Y., Villares-Ledesma, M. L., and Melo-Heras, E. J. (2024). Comprehensive assessment of coffee varieties (Coffea arabica L. Coffea canephora L.) from coastal, andean, and amazonian regions of ecuador; a holistic evaluation of metabolism, antioxidant capacity and sensory attributes. Horticulturae 10:200. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae10030200

Molina, D., Angamarca, E., Marinescu, G. C., Popescu, R. G., and Tenea, G. N. (2025). Integrating metabolomics and genomics to uncover antimicrobial compounds in Lactiplantibacillus plantarum UTNGt2, a CACAO-Originating probiotic from ecuador. Antibiotics 14:123. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics14020123

Moloudizargari, M., Mikaili, P., Aghajanshakeri, S., Asghari, M. H., and Shayegh, J. (2013). Pharmacological and therapeutic effects of Peganum harmala and its main alkaloids. Pharmacognosy Rev. 7, 199–212. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.120524

Mussatto, S. I., and Mancilha, I. M. (2007). Non-digestible oligosaccharides: A review. Carbohydrate Pol. 68, 587–597. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2006.12.011

Muyzer, G., de Waal, E. C., and Uitterlinden, A. G. (1993). Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993

Okoye, C. O., Jiang, H., Wu, Y., Li, X., Gao, L., Wang, Y., et al. (2023). Bacterial biosynthesis of flavonoids: Overview, current biotechnology applications, challenges, and prospects. J. Cell. Physiol. 239:e31006. doi: 10.1002/jcp.31006

Padonou, S. W., Nielsen, D. S., Akissoe, H. N., Hounhouigan, D. J., and Jakobsen, M. (2022). Fermentation characteristics of lactic acid bacteria in the presence of plant phenolics: Adaptation, peptide production, and functionality. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 158:113105. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113105

Pang, Z., Lu, Y., Zhou, G., Hui, F., Xu, L., Viau, C., et al. (2024). MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W398–W406. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae253

Papadimitriou, K., Alegría, Á Bron, P. A., de Angelis, M., Gobbetti, M., Kleerebezem, M., et al. (2016). Stress physiology of lactic acid bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 837–890. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00076-15

Parthasarathy, A., Cross, P. J., Dobson, R. C. J., Adams, L. E., Savka, M. A., and Hudson, A. O. (2018). A three-ring circus: Metabolism of the three proteogenic aromatic amino acids and their role in the health of plants and animals. Front. Mol. Biosci. 5:29. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00029

Paul, B. D., Sbodio, J. I., and Snyder, S. H. (2018). Cysteine metabolism in neuronal redox homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 39, 513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.02.007

Pessione, E., and Cirrincione, S. (2016). Bioactive molecules released in food by lactic acid bacteria: Encrypted peptides and biogenic amines. Front. Microbiol. 7:876. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00876

Picon, A., Campanero, Y., Sánchez, C., Álvarez, I., and Rodríguez-Mínguez, E. (2024). Valorization of coffee cherry by-products through fermentation by human intestinal Lactobacilli in functional fermented milk beverages. Foods 14:44. doi: 10.3390/foods14010044

Piechowska, P., Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R., and Mildner-Szkudlarz, S. (2019). Bioactive β-Carbolines in food: A review. Nutrients 11:814. doi: 10.3390/nu11040814

Portaccio, M., Faramarzi, B., and Lepore, M. (2023). Probing biochemical differences in lipid components of human cells by means of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Biophysica 3, 524–538. doi: 10.3390/biophysica3030035

Sadat, A., and Joye, I. J. (2020). Peak fitting applied to fourier transform infrared and Raman spectroscopic analysis of proteins. Appl. Sci. 10:5918. doi: 10.3390/app10175918

Schieber, A., and Wüst, M. (2020). Volatile phenols—important contributors to the aroma of plant-derived foods. Molecules 25:4529. doi: 10.3390/molecules25194529

Shen, X., Wang, Q., Wang, H., Fang, G., Li, Y., Zhang, J., et al. (2025). Microbial characteristics and functions in coffee fermentation: A review. Fermentation 11:5. doi: 10.3390/fermentation11010005

Siezen, R. J., Tzeneva, V. A., Castioni, A., Wels, M., Phan, H. T. K., Rademaker, J. L. W., et al. (2010). Phenotypic and genomic diversity of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from various environmental niches. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 758–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02119.x

Silva, L. C. F., Pereira, P. V. R., Cruz, M. A. D. D., Costa, G. X. R., Rocha, R. A. R., Bertarini, P. L. L., et al. (2024). Enhancing sensory quality of coffee: The impact of fermentation techniques on. Foods 13:653. doi: 10.3390/foods13050653

Sizeland, K. H., Hofman, K. A., Hallett, I. C., Martin, D. E., Potgieter, J., Kirby, N. M., et al. (2018). Nanostructure of electrospun collagen: Do electrospun collagen fibers form native structures? Materialia 3, 90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mtla.2018.10.001

Strahsburger, E., Lopez, de Lacey, A. M., Marotti, I., DiGioia, D., Biavati, B., et al. (2017). In vivo assay to identify bacteria with β-glucosidase activity. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 30, 83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbt.2017.08.010

Su, L. W., Cheng, Y. H., Hsiao, F. S., Han, J. C., and Yu, Y. H. (2018). Optimization of mixed solid-state fermentation of soybean meal by Lactobacillus Species and Clostridium butyricum. Pol. J. Microbiol. 67, 297–305. doi: 10.21307/pjm-2018-035

Synytsya, A., and Novak, M. (2014). Structural analysis of glucans. Ann. Trans. Med. 2:17. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.02.07

Tan, Y., Wu, H., Shi, L., Barrow, C., Dunshea, F. R., and Suleria, H. A. R. (2023). Impacts of fermentation on the phenolic composition, antioxidant potential, and volatile compounds profile of commercially roasted coffee beans. Fermentation 9:918. doi: 10.3390/fermentation9100918

Tatulian, S. A. (2019). “FTIR analysis of proteins and protein–membrane interactions,” in Lipid-Protein interactions. methods in molecular biology, Vol. 2003, ed. J. Kleinschmidt (New York, NY: Humana), doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9512-7_13

Tenea, G. N., Cifuentes, V., Reyes, P., and Cevallos-Vallejos, M. (2025). Unveiling the microbial signatures of Arabica coffee cherries: Insights into ripeness-specific diversity, functional traits, and implications for quality and safety. Foods 14:614. doi: 10.3390/foods14040614

Tennoune, N., Andriamihaja, M., and Blachier, F. (2022). Production of indole and indole-related compounds by the intestinal microbiota and consequences for the host: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Microorganisms 10:930. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10050930

Todhanakasem, T., Van Tai, N., Pornpukdeewattana, S., Charoenrat, T., Young, B. M., and Wattanachaisaereekul, S. (2024). The relationship between microbial communities in coffee fermentation and aroma with metabolite attributes of finished products. Foods 13:2332. doi: 10.3390/foods13152332

Tolessa, K., D’heer, J., Duchateau, L., and Boeckx, P. (2017). Influence of growing altitude, shade and harvest period on quality and biochemical composition of Ethiopian specialty coffee. J. Sci. Food Agriculture 97, 2849–2857. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8114

Tomasetig, D., Wang, C., Hondl, N., Friedl, A., and Ejima, H. (2024). Exploring caffeic acid and lignosulfonate as key phenolic ligands for metal-phenolic network assembly. ACS Omega 9, 20444–20453. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.4c01399

Torres Castillo, N. E., Melchor Martínez, E. M., Ochoa Sierra, J. S., Ramirez-Mendoza, R. A., Parra Saldívar, R., and Iqba, H. M. N. (2020). Impact of climate change and early development of coffee rust: An overview of control strategies to preserve organic cultivars in Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 738, 140–225. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140225

Ucar, R. A., Pérez-Díaz, I. M., and Dean, L. L. (2020). Gentiobiose and cellobiose content in fresh and fermenting cucumbers and utilization of such disaccharides by lactic acid bacteria in fermented cucumber juice medium. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 5798–5810. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1830

Venegas Sánchez, S., Orellana Bueno, D., and Pérez Jara, P. (2018). La realidad ecuatoriana en la producción de café. Recimundo 2, 72–91. doi: 10.26820/recimundo/2.(2).2018.72-91

Virdis, C., Sumby, K., Bartowsky, E., and Jiranek, V. (2021). Lactic acid bacteria in wine: Technological advances and evaluation of their functional role. Front. Microbiol. 11:612118. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.612118

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M., and Cole, J. R. (2007). Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07

Weisburg, W. G., Barns, S. M., Pelletier, D. A., and Lane, D. J. (1991). 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173, 697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991

Wijaya, E. C., Separovic, F., Drummond, C. J., and Greaves, T. L. (2016). Micelle formation of a non-ionic surfactant in non-aqueous molecular solvents and protic ionic liquids (PILs). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 24377–24386. doi: 10.1039/C6CP03332F

Wszołek, A. (2022). Monooksygenazy cytochromu P450 – wszechstronne biokatalizatory [Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases - versatile biocatalysts]. Postepy Biochem. 68, 399–409. doi: 10.18388/pb.2021_464