- 1The First People’s Hospital of Neijiang City, Sichuan, Neijiang, China

- 2The Second People’s Hospital of Neijiang City, Sichuan, Neijiang, China

Objective: This study aims to conduct a comparative analysis of the effects of different physical therapies on the pain, fatigue, functional impairment, quality of life, and grip strength of breast cancer survivors. Design:A systematic review and network meta-analysis were conducted.

Methods: The process of screening, data extraction, coding and bias risk assessment is conducted in an independent and duplicated manner. The primary outcome measures are subjected to evaluation through the utilization of Bayesian network meta-analysis. The online Meta-analysis Confidence (CINeMA) tool is employed to assess the quality of evidence.

The data source: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and Embase.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies: This article examines any randomized controlled trials that involve physical therapy for breast cancer survivors.

Results: A total of 111 RCTs involving 6888 participants and 16 types of physical therapy interventions were included. A network meta-analysis showed that all physical therapy measures had some effect on breast cancer survivors compared with placebo. Virtual reality technology may be more effective in relieving pain, electrotherapy may be more effective in restoring functional disorders, kinesiology taping may be more effective in terms of fatigue, quality of life (physical aspect), and grip strength, and aerobic exercise may be more effective in relieving Quality of life (Mental Component). The final curvature under the cumulative sequence curve indicates that virtual reality technology, intramuscular adhesives, and mixed exercises are relatively good auxiliary treatment methods. The degree of confidence varies from high to very low according to CINeMA.

Conclusion: For breast cancer survivors, mental improvements are just as important as physical improvements. Researchers should pay more attention to the overall benefits and the safety and feasibility of trials. However, this conclusion still needs to be further verified by a large number of multi-center and large sample size RCT.

Background

Breast cancer is the most prevalent form of cancer among women (1–3). Consequently, a significant volume of research is dedicated to the management of breast cancer in various settings, including diagnosis, surgery, adjuvant therapy, and metastatic treatment (4). Breast cancer survivors frequently encounter complications such as lymphedema, limited shoulder mobility, pain, fatigue, and other health issues (5–8). These sequelae collectively represent a major clinical challenge in survivorship care, as they significantly impair physical function, psychological well-being, and overall health-related quality of life. Consequently, the development of effective rehabilitation strategies is a priority within oncological clinical practice guidelines. A meta-analysis of randomized trials has demonstrated the efficacy of physical therapy in improving function in patients with early breast cancer (9). At the time, however, there was a paucity of research on complementary treatments for breast cancer, and no conclusive research evidence existed regarding the safety or actual efficacy of most physical therapy modalities for breast cancer survivors.

The utilization of diverse physical therapy modalities has undergone a gradual transition over time. Conventional decongestant therapy plays a pivotal role in the management of lymphedema in breast cancer, encompassing manual lymphatic drainage, intermittent pneumatic compression, compression bandages or pressure garments, regular functional exercise, and skin care (10–12). Subsequent studies have seen an increase in the use of alternative physical therapy modalities, including the application of intramural tape, hydrolymphatic therapy, virtual reality technology, neuromuscular promotion technology and yoga in breast cancer survivors, thus providing survivors with a choice of physical therapy interventions (13–19). This expansion of available modalities is reflected in numerous systematic reviews, which have synthesized evidence for individual interventions. However, these reviews often focus on a single therapy or a limited set of outcomes, creating a fragmented evidence base. However, the issue remains unresolved, as no study has yet demonstrated which physical therapy modality is more beneficial for breast cancer survivors. The critical gap lies in the absence of a unified, comparative analysis that ranks these diverse interventions simultaneously to inform clinical decision-making.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of various physical therapy interventions for breast cancer survivors, with a particular focus on pain management and quality of life. To provide a comprehensive assessment of patient-centered outcomes, we also pre-specified several secondary outcomes, including fatigue, functional disability, and grip strength, which are commonly reported in the literature and highly relevant to daily living. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has systematically analyzed and statistically compared diverse physical therapy techniques for this population. We conducted a comprehensive literature review and performed a network meta-analysis to evaluate the relative efficacy of these interventions. Our aim was to identify optimal physical therapy approaches and provide evidence-based clinical recommendations.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines. The literature search was conducted for articles published between January 1990 and October 2025. See Appendix for a detailed search strategy. In order to obtain a more complete data report, we also conducted a search of references from relevant systematic reviews included in the study, and conducted a manual check to obtain and identify eligible gray literature. We manually screened the reference lists of all studies included in the final analysis as well as relevant systematic reviews identified during our database search to identify any potentially eligible articles that our electronic search might have missed.

Data selection

Inclusion criteria: (a) Randomized controlled trial; (b) Study participants were breast cancer survivors aged 18 years or older; (c)studies in which patients have received some intervention related to physical therapy (any treatment related to physical exercise, manual therapy or other complementary therapies used in clinical practice) (20); (d) Outcome measures included at least one of pain assessment, fatigue assessment, functional disability assessment, quality of life, and grip strength, and relevant data were extracted before and after treatment.

Exclusion criteria: (a) literature with incomplete data, such as meetings, abstracts, letters and reviews; (b) Duplicate published studies; (c) Studies in which literature data cannot be extracted effectively; (d) Studies where the full text is not available;(e) Pilot randomized controlled trial.

Rationale for the broad scope of interventions

We acknowledge the methodological challenge of incorporating a wide array of physical therapy modalities, which indeed differ in their application and mechanisms of action (e.g., passive device-based therapies like electrotherapy versus active, patient-engaged modalities like exercise). The decision to include this diverse set was driven by the primary research objective: to provide a comprehensive overview and generate a hierarchy of effectiveness for the most common physical therapy interventions available in clinical practice for breast cancer survivors. This approach, while introducing clinical heterogeneity, is a recognized application of network meta-analysis (NMA) aimed at answering a pragmatic clinical question. We have addressed this inherent diversity through several measures: 1) ensuring all interventions fall under the broad, pre-specified definition of physical therapy; 2) conducting a thorough evaluation of the transitivity assumption; and 3) performing sensitivity and subgroup analyses to explore the impact of different intervention types on the overall results, as detailed in the subsequent analysis sections.

Literature screening and data extraction

The electronic database was searched independently by two researchers (YL and LC) using EndNote software to delete duplicate studies. Relevant literature titles and abstracts were then read, and literature not relevant to the study was excluded. The selection process was conducted by the two researchers, and any objections were discussed until a consensus was reached. If a consensus could not be reached, the third researcher made the final decision after group discussion. The data were then extracted and organized according to pre-established information tables, including the first author of each study, the year of publication, the country in which the study was conducted, mean/median age of the study participants, the sample size, the intervention mode, the randomization method, the treatment cycle, and the outcome evaluation.

Literature quality evaluation

The RCTs included were assessed for methodological bias and quality according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions. This assessment included the generation of random sequences, assignment concealment, investigator-patient blindness, blind outcome evaluation, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias (21). Assessment options include: ‘Low risk,’ ‘High risk,’ or ‘Unclear risk.’ To assess the confidence of each comparison with the control group, we also used the CINeMA online assessment system, a tool designed by Cochrane to compare multiple intervention groups as an adaptation of the GRADE network meta-analysis to determine in-study bias, reporting bias, incoherence, imprecision, heterogeneity, and inconsistency (22, 23).

Statistical analysis

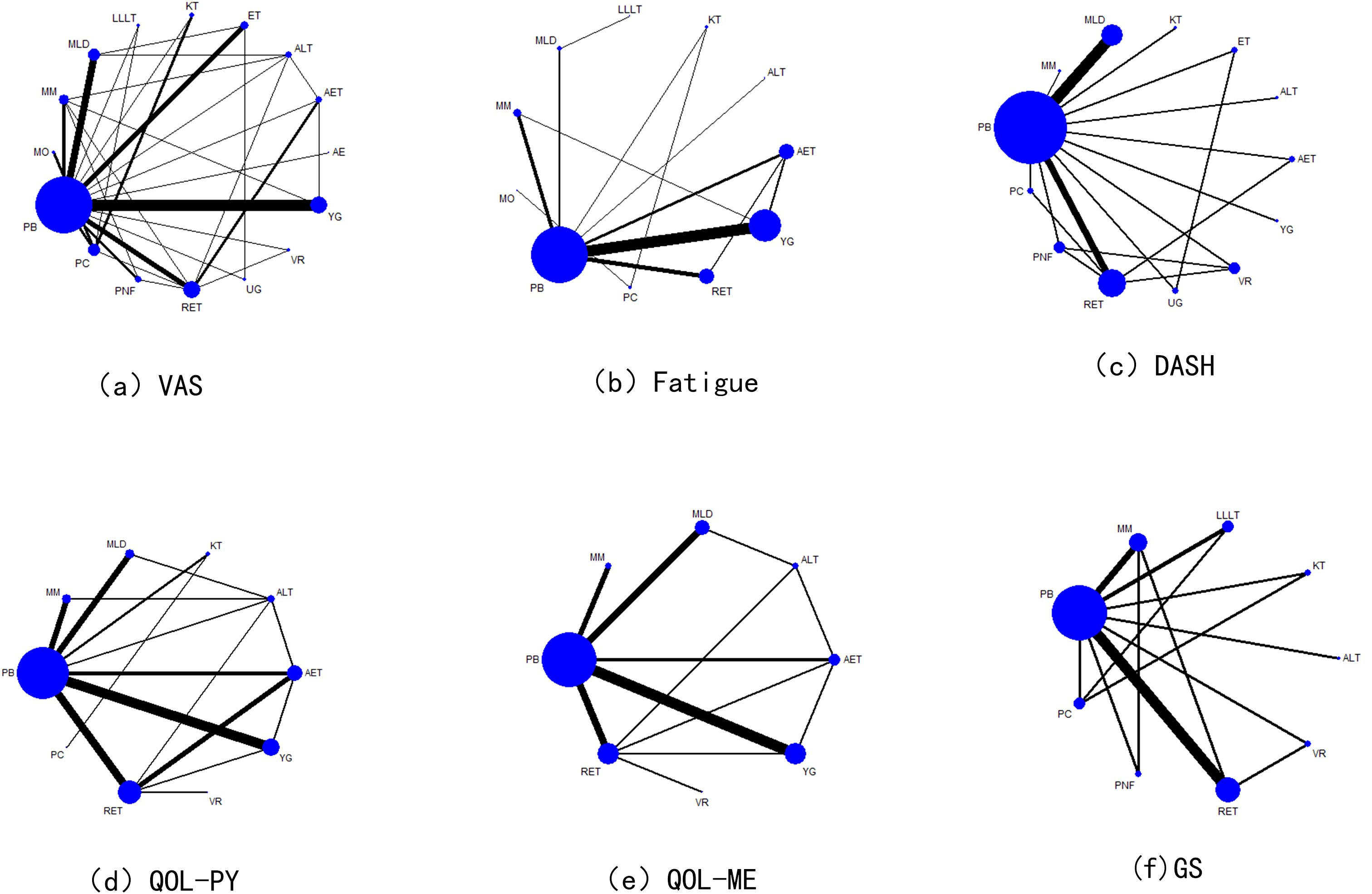

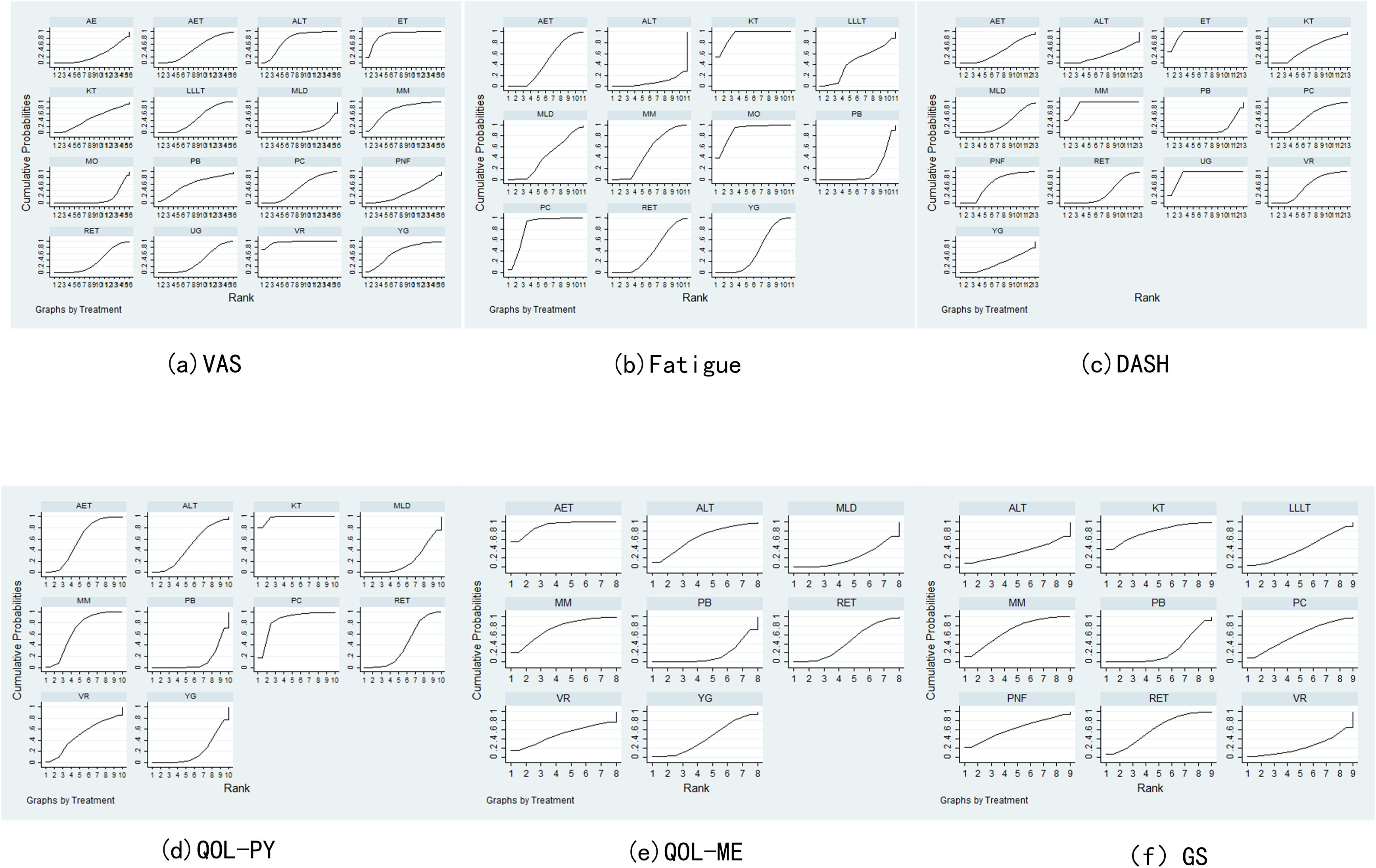

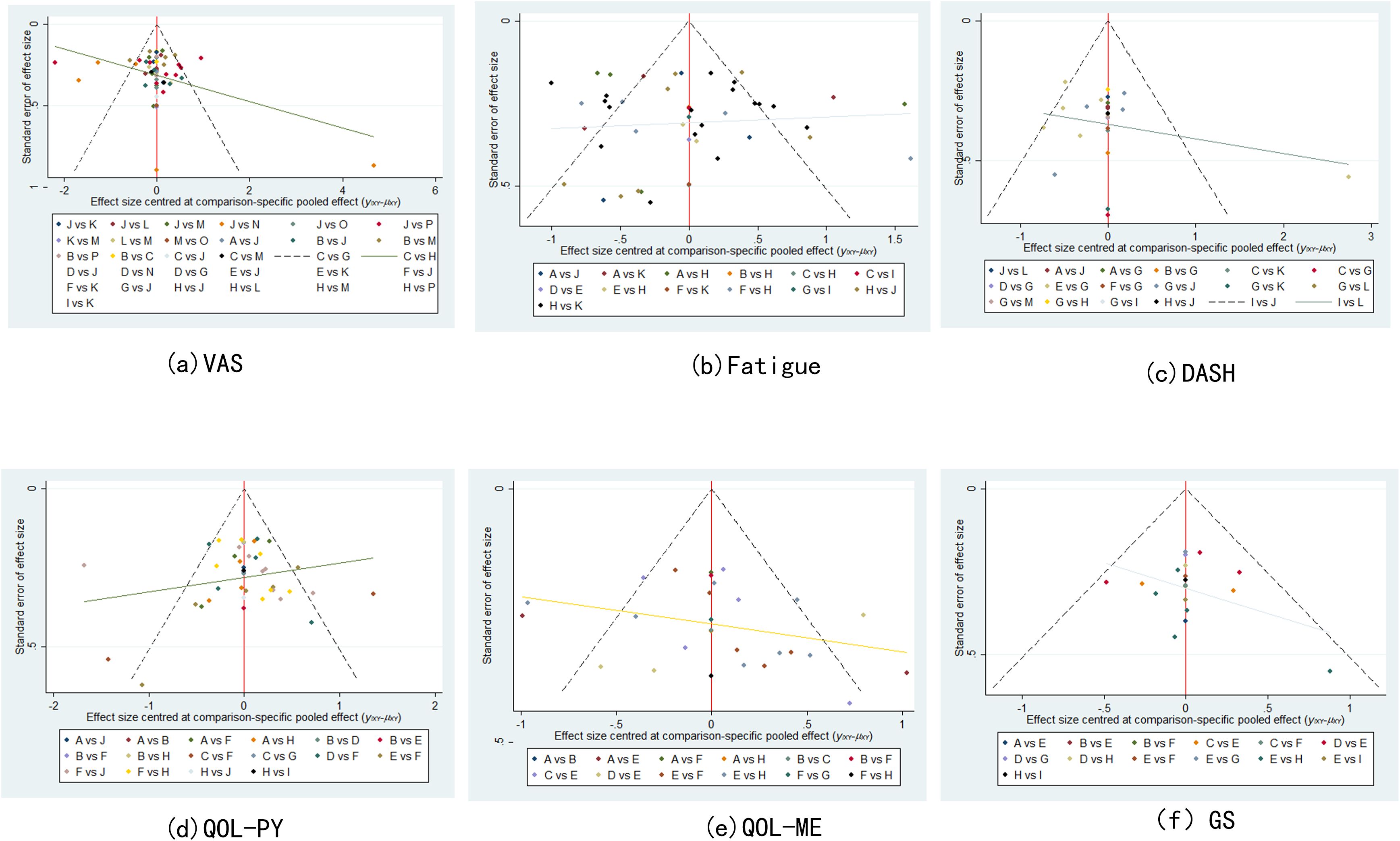

Network meta-analysis of the data was performed using Stata 17.0 software (24, 25). In this study, continuous variables were employed, and weighted mean difference (WMD) statistics were combined, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) being calculated, including VAS, QOL, fatigue and GS. When the 95%CI value of WMD was 0, the comparison was deemed to be statistically insignificant. P < 0.05 indicated significant differences, and I² value was used to test heterogeneity. When P > 0.05 and I² ≤ 50%, it indicated small differences, and a fixed benefit model was used for network meta-analysis. Conversely, when P < 0.05 and I² > 50%, a random effects model was used to further explore the source of heterogeneity, including subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis. For each pre-specified outcome, a global network diagram is used to illustrate a direct comparison between interventions, with the size of the nodes in the graph corresponding to the number of participants receiving each treatment. Treatments receiving direct comparisons are connected with lines whose thickness is proportional to the number of tests evaluating a particular comparison. In the results section, a cumulative probability ranking plot is used to represent the ranking probability of each intervention, with SUCRA values ranging from 0 to 100%, with higher SUCRA values indicating a higher ranking of the intervention, generally reflecting a more favorable or unfavorable effect. The ranking of interventions was conducted on the basis of SUCRA values or the area under the curve, with the objective being to calculate the ranking result of the probability cumulative ranking curve of each physical therapy intervention, to draw a ranking map, and to judge the relatively best physical therapy measures. In order to assess potential publication bias, funnel plots adjusted for comparison were used. The analysis was designed to determine whether there was evidence of small sample effects or publication bias in the intervention network.

Results

Literature search results

As demonstrated in Figure 1, a total of 4,359 publications were identified (Pubmed: 1,168, Embase: 802, Cochrane Library: 2,063, Web of Science: 314, Other sources: 12) 2,172 duplicative literatures were deleted, 685 non-conforming literatures were deleted according to abstract and title, 128 were not searched reports, 1,374 literatures met full text screening, 1,263 literatures were deleted according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 111 (26–136) literatures were finally included. The two statisticians have a unified opinion in the process of searching and including documents.

Basic features and quality assessment were included

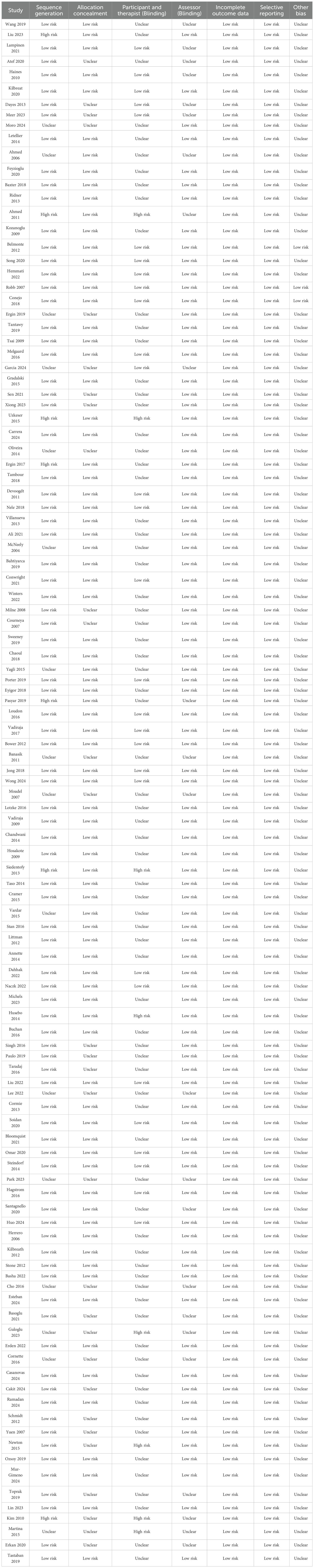

A total of 111 randomized controlled trials were included in the analysis, with a total of 6,888 participants from 22 countries. The 111 studies comprised 16 distinct interventions: aquatic exercise, aerobic exercise, aqua lymphatic therapy, electrotherapy, kinesio taping, low level laser therapy, manual lymphatic drainage, mixed motion, moxibustion, pneumatic circulation, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, resistance exercise, virtual reality, yoga and ultrasound therapy. The fundamental characteristics of the included studies are delineated in Table 1. The Cochrane systematic review of interventions described the evaluation of randomized controlled trials on seven aspects associated with the risk of bias (see Table 2). Please refer to Appendix for the CINeMA Network Meta-online evaluation.

Results of network meta-analysis

Network diagram

A total of 16 interventions were included in the literature review, of which 47 studies reported VAS, 38 studies reported Fatigue Assessment, 22 studies reported DASH(Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand) Functional Disability Index, and 36 studies reported QOL (Physical Component) scores. QOL (Mental Component) scores were reported in 26 studies, and GS scores were reported in 18 studies. The results are illustrated in Figure 2.

Inconsistency testing and reliability testing

For all outcome measures that constitute network evidence, no significant inconsistencies were detected, thereby substantiating the hypothesis that network analysis possesses satisfactory internal consistency. A web meta-analysis of confidence in CINeMA was employed to assess confidence, and the overall quality of evidence was found to be substandard (see Appendix for details).

Analysis of the results of each index

Pain assessment

Pain assessment was reported in 47 studies: Virtual Reality was associated with significantly lower pain scores compared to Aerobic Exercise (SMD = –2.26, 95% CI: –4.20 to –0.33). Electrotherapy also showed superior pain reduction relative to Aquatic Exercise (SMD = –1.81, 95% CI: –3.24 to –0.38). In contrast, Manual Lymphatic Drainage resulted in significantly higher pain scores compared to Aqua Lymphatic Therapy (SMD = 1.45, 95% CI: 0.41 to 2.50), and Low-Level Laser Therapy was associated with higher pain scores relative to Electrotherapy (SMD = 1.42, 95% CI: 0.13 to 2.70). The SUCRA value of Virtual Reality (96.5%) was relatively high, followed by Electrotherapy (89.4%) and Aqua Lymphatic Therapy (75.3%).As demonstrated in Figures 3a, 4a.

Fatigue assessment

Thirty-eight studies reported fatigue assessment data: Placebo was associated with significantly higher fatigue scores compared to Kinesio Taping (SMD = 3.24, 95% CI: 1.71 to 4.78) and Moxibustion (SMD = 3.07, 95% CI: 0.68 to 5.47). In contrast, Pneumatic Circulation demonstrated significantly lower fatigue scores than Placebo (SMD = –2.71, 95% CI: –4.71 to –0.70), as did Yoga (SMD = –0.34, 95% CI: –0.65 to –0.04). The SUCRA analysis revealed that Kinesio Taping (93.5%) has a more significant effect, followed by Moxibustion (89.9%) and Pneumatic Circulation (83.6%). As illustrated in Figures 3b, 4b.

DASH functional disability

Twenty-two studies reported DASH functional disability index: Placebo was associated with significantly higher disability scores compared to Electrotherapy (SMD = 4.69, 95% CI: 2.78 to 6.59) and Mixed Motion (SMD = 4.54, 95% CI: 3.01 to 6.08). Conversely, Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation resulted in significantly lower scores than Placebo (SMD = –1.16, 95% CI: –2.25 to –0.06), as did Ultrasound therapy (SMD = –4.49, 95% CI: –6.37 to –2.61). The SUCRA analysis revealed that Electrotherapy (93%) has a more significant effect, followed by Mixed Motion (91.2%) and Ultrasound therapy (90.7%). As demonstrated in Figures 3c, 4c.

QOL (Physical component)

Thirty-six studies reported QOL (Physical component): Placebo was associated with significantly lower QOL scores compared to Aerobic Exercise (SMD = –0.52, 95% CI: –0.97 to –0.07), Kinesio Taping (SMD = –1.99, 95% CI: –2.87 to –1.10), and Mixed Motion (SMD = –0.67, 95% CI: –1.15 to –0.18). Kinesio Taping (97.8%) had a more favorable effect on SUCRA, followed by Pneumatic Circulation (84.7%) and Mixed Motion (67.3%). As demonstrated in Figures 3d, 4d.

QOL (Mental component)

Twenty-six studies reported QOL (Mental component): Placebo was associated with significantly lower QOL scores compared to Aerobic Exercise (SMD = –1.12, 95% CI: –1.86 to –0.38). Similarly, Manual Lymphatic Drainage demonstrated significantly lower scores relative to Aerobic Exercise (SMD = –1.09, 95% CI: –1.99 to –0.20), as did Resistance Exercise (SMD = –0.81, 95% CI: –1.62 to –0.01). The SUCRA value of Aerobic Exercise (90.3%) was relatively strong, followed by Mixed Motion (73%) and Aqua Lymphatic Therapy (63.7%). As demonstrated in Figures 3e, 4e.

Grip strength

The results of the network meta-analysis for grip strength (GS), based on 18 studies, indicated that no significant differences were observed between Placebo and Aqua Lymphatic Therapy (SMD = –0.01, 95% CI: –1.43 to 1.45), Kinesio Taping (SMD = –0.82, 95% CI: –1.89 to 0.25), or Mixed Motion (SMD = –0.59, 95% CI: –1.26 to 0.08). The SUCRA value of Kinesio Taping (77.2%) was relatively high, followed by Mixed Motion (68.4%) and Resistance Exercise (61.5%). As demonstrated in Figures 3f, 4f.

Publication bias

Correction-comparison funnel plots of VAS, fatigue, DASH, QOL (physical component), QOL (mental component), and GS were plotted to assess publication bias. It can be seen that all points basically fall within the funnel, and the distribution of scatter points on both sides of X = 0 is roughly symmetrical, suggesting that the possibility of publication bias or small sample effect is small (see Figure 5).

Discussions

In this systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, the effect of various physical therapies on breast cancer survivors was found to be positive in comparison to placebo (home schooling or primary care). However, the evidence results were moderate, either by themselves or in combination with other medications or surgery. We believe that based on the SUCRA assessment, VR is a relatively effective physical therapy method in terms of pain improvement. The analgesic mechanism of Virtual Reality (VR) is primarily attributed to its capacity to engage multiple attentional and cognitive resources, thereby diverting processing capacity away from nociceptive signals in a manner consistent with the limited capacity model of attention (67). In terms of improving fatigue scores, kinesiology tape may be more effective. It is believed to be able to promote local microcirculation and the drainage of lymph fluid, thereby helping to eliminate metabolic waste and improve the oxygen supply to tissues. At the same time, the neuro-regulatory effect produced by continuous skin stimulation may help restore the abnormal muscle tension to normal levels and reduce pain through the gating theory, thereby alleviating fatigue conditions (137, 138). However, for DASH functional disability, electrotherapy may be a more effective form of physical therapy. This might be achieved through its various neuroregulatory and physiological effects, by activating large-diameter afferent fibers to “gate control” the transmission of nociceptive signals in the spinal cord, and possibly stimulating the release of endogenous opioids, thereby regulating pain perception. Furthermore, electrotherapy helps prevent muscle atrophy and enhance local blood circulation, thereby addressing potential damage to muscle function and promoting tissue recovery. This combined effect of pain relief and recovery alleviates pain and facilitates the functional use of the upper limbs (85). Due to the predominance of female subjects in the study, a gender-based subgroup analysis was not feasible. However, a preliminary investigation into age stratification revealed a correlation between younger age and greater benefit. The intensity of physical therapy cannot be fully assessed in survivors of different stages of breast cancer. However, mixed exercise has been shown to have some advantages in terms of selection as adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. An appropriate increase in exercise intensity may be more conducive to the improvement of patient function. This is consistent with the views of Zhou et al. (139) that mixed exercise and resistance exercise can effectively improve the fatigue experienced by breast cancer survivors. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that exercise intervention with a frequency of ≥3 times per week, lasting > 60 minutes each time and > 180 minutes per week, has a more pronounced effect. Increasing the level of physical activity has been shown to reduce the risk of various cancers, and the appropriate intensity of exercise can effectively reduce the overall mortality and adverse reactions of various cancers, including breast cancer (139–142). It is imperative to raise awareness of the benefits of exercise and to conduct disease screening and assessment according to factors such as age and gender, which can effectively reduce the medical burden (143). In a similar vein, it is postulated that the incorporation of physical therapy modalities such as pneumatic circulation therapy, Aqua lymphatic therapy, aerobic exercise and mixed exercise into the therapeutic regimen of breast cancer survivors would prove to be of considerable benefit in enhancing their quality of life.

Our review did not find an exact causal mechanism, but the statistical findings are valid. A single mechanism of action may not fully explain all of our findings. We therefore considered a number of hypotheses, including a combination of mindfulness or psychological cues (144), competing mechanisms (145), interstitial or lymphatic regulation (146), edema blocking mechanisms (147), neuromuscular regulation (18), functional or pain-related (148), and photobiological regulation (149), to produce a positive and favorable outcome. The meta-findings found that these factors were associated with improved quality of life or lymphedema in breast cancer survivors, but could not fully explain why a single mechanism covered all factors. Yoga exercises, for example, can directly promote the role of mindfulness, while also improving mental health (150); Various kinds of sports, including aerobic exercise, resistance exercise and mixed exercise, they have a certain competitive relationship, but also affect each other, because no sport can exist completely independently (151–153); The effects of pressure therapy, bandages and kinesio taping on edema blockage in breast cancer survivors were profound (123, 154, 155). Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation technology and virtual reality technology are important manifestations of neuromuscular regulation (156, 167). Electrotherapy, moxibustion, and ultrasound therapy provide more positive effects on pain and function (29, 157, 158). Manual lymphatic drainage may satisfy a variety of mechanisms, but it cannot cover all aspects (66, 159). We believe that understanding the mechanisms of action of these treatments can lead to better understanding and development of adjuvant treatment plans.

Our review included more studies than previous reviews of breast cancer survivors with various physical therapies (148, 149, 160–164). Therefore, we can draw a more comprehensive and accurate conclusion. We included 111 studies for statistical analysis, and the confidence interval is narrower than that of most existing meta-analyses, and the accuracy of the estimation is higher (165). At the same time, we found a significant phenomenon that for the treatment cycle, the shorter the time, the better the effect, which was similar to the study results of Wahid et al. (164). However, this is not absolute, because most statistics do not have an absolute linear time sequence, we cannot give a precise judgment on the duration of the treatment effect, and it is certain that the long-term (beyond 12 months) effect after treatment is gradually reduced. In our review, some niche treatments, such as the use of intramuscular patches, had good results, possibly because mesh meta-analyses used smaller study data with higher efficacy than ordinary meta-analyses. In addition, a proportion of the studies we included combined different interventions, making it more difficult to interpret the estimates of meta-analyses.

This study shows that virtual reality technology can improve the pain of breast cancer survivors most obviously. This non-invasive, non-pharmaceutical choice may be based on the fact that virtual reality can distract patients’ attention and reduce their pain experience to a certain extent through meditation and mindfulness technology (166–168). The use of virtual reality technology in clinical practice is not uncommon, whether in assessment or treatment, immersive gaming experience and emotional rendering, which is also effective for mental illness in breast cancer survivors (169–171). Aerobic exercise is very effective in improving the psychological aspect of quality of life, and the importance of exercise for cancer patients has been generally emphasized. Regular exercise can improve physical function, enhance the immune function of cancer patients, psychologically provide better feelings and reduce stress, depression and anxiety (172–175). In addition, we found good acceptance of electrotherapy, manual lymphatic drainage, and pneumatic circulation therapy, due to a lower percentage of dropouts or omissions found in most of the included studies, although measurements of dropouts are not fully representative of patient acceptance. Whether a patient completes the study depends largely on the interest and effectiveness of the adjuvant treatment program. Of course, these passive physical therapies seem to be more satisfying to patients. However, we are confused that the opt-out rate in the control group is still not high, and there are many included literatures that do not mention these useful data, so more high-quality studies are needed to confirm these results.

The present study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, the literature included is all in English, which may result in geographical and ethnic bias, although the comparison of adjusted funnel plots suggests that this probability is not high. Secondly, the large number of included studies may have resulted in heterogeneity due to differences in research objects, intervention measures, outcome indicators, etc. Despite the implementation of stricter inclusion criteria and quality assessment, these heterogeneities could not be eliminated. For instance, when assessing the quality of life, not all relevant scales were included. We mainly incorporated assessment tools such as SF-36 (Short Form 36 Health Survey) and EORTC QLQ (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire), which led to the exclusion of some quality assessment tools like ULL-27 (Upper Limb Lymphedema-27). Vatansever et al. demonstrated that the ULL-27 questionnaire is a reliable and effective scale for assessing the quality of life of patients with upper limb lymphedema (176). In addition, the treatment methods and treatment cycles of the included studies exhibited significant heterogeneity, and the disease progression of patients was not completely consistent. The standards of resistance exercise, aerobic exercise and mixed exercise in exercise therapy were not fully unified, which may also be the cause of large heterogeneity. Low confidence levels are usually due to in-study bias, imprecise treatment effects, or lack of randomization and assignment of hidden information (21). Given that a significant portion of the included randomized controlled trials were assessed as having “low” or “very low” confidence levels based on the CINeMA evaluation, these findings must be interpreted with caution. The inherent limitations of this primary evidence significantly weaken the strength and generalizability of our conclusions, and emphasize that they should not be regarded as direct clinical application guidelines without further validation. Consequently, there is a necessity for further high-quality, multi-center, large-sample studies to be conducted in the future in order to strengthen the data.

In light of the significance of clinical decision-making, there is a need to elucidate the benefits and limitations of employing diverse physical therapy interventions in the management of breast cancer survivors. This information should be made readily available to physicians, rehabilitation therapists, and caregivers. The findings of this study should contribute to the development of future guidelines or the revision of existing information, with the objective of ensuring that patients receive optimal physical therapy and care. The results of our network meta-analysis show that all physical therapy measures seem to be effective compared with the placebo group. This finding has considerable value in clinical practice.

Conclusion

All physical therapy measures demonstrated efficacy in breast cancer survivors when compared with placebo. Virtual reality technology exhibited the most significant effect on pain improvement, while electrotherapy demonstrated the most substantial effect on functional disability recovery. Intramuscular tape exhibited the most marked effect on fatigue, physical quality of life and grip strength, and aerobic exercise exhibited the most substantial effect on psychological quality of life. However, these findings require further validation through large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YLu: Visualization, Resources, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Validation, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software. QH: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Conceptualization, Data curation. XC: Methodology, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. HP: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation. YLi: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. LC: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation. LZ: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation. YH: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1699682/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CI, confidence interval; AE, aquatic exercise; AET, aerobic exercise; ALT, aqua lymphatic therapy; ET, electrotherapy; KT, kinesio taping; LLLT, low level laser therapy; MLD, manual lymphatic drainage; MM, mixed motion; MO, moxibustion; PB, placebo group; PC, pneumatic circulation; PNF, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation; RET, resistance exercise; VR, virtual reality; YG, yoga; UG, ultrasound therapy; SMD, Standard Mean Difference; SUCRA, Surface Under The Cumulative Ranking Curve; VAS, visual analog scale; GS, Grip strength; QOL, Quality of Life; DASH, Disabilities of Arm; Shoulder and Hand; SF-36, Short Form 36 Health Survey; EORTC QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; ULL-27, Upper Limb Lymphedema-27.

References

1. Decker NS, Johnson T, Vey JA, Le Cornet C, Behrens S, Obi N, et al. Circulating oxysterols and prognosis among women with a breast cancer diagnosis: results from the MARIE patient cohort. BMC Med. (2023) 21:438. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-03152-7

2. Liu Z, Yu B, Su M, Yuan C, Liu C, Wang X, et al. Construction of a risk stratification model integrating ctDNA to predict response and survival in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer. BMC Med. (2023) 21:493. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-03163-4

3. Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. (2022) 66:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.08.010

4. Hogeveen SE, Han D, Trudeau–Tavara S, Buck J, Brezden–Masley CB, Quan ML, et al. Comparison of international breast cancer guidelines: are we globally consistent? Cancer guideline AGREEment. Curr Oncol. (2012) 19:184–90. doi: 10.3747/co.19.930

5. Harborg S, Larsen HB, Elsgaard S, and Borgquist S. Metabolic syndrome is associated with breast cancer mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. (2025). doi: 10.1111/joim.20052

6. Mete Civelek G, Borman P, Sahbaz Pirincci C, Yaman A, Ucar G, Uncu D, et al. The comparative frequency of breast cancer-related lymphedema determined by perometer and circumferential measurements: relationship with functional status and quality of life. Lymphat Res Biol. (2025). doi: 10.1089/lrb.2024.0008

7. Leitzelar BN, Crawford SL, Levine B, Ylitalo KR, Colvin AB, Gabriel KP, et al. Physical activity and quality of life among breast cancer survivors: Pink SWAN. Support Care Cancer. (2025) 33:101. doi: 10.1007/s00520-025-09156-8

8. Paltrinieri S, Cavuto S, Contri A, Bassi MC, Bravi F, Schiavi M, et al. Needs of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative data. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2024) 201:104432. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104432

9. A’Hern RP and Ebbs S. Meta-analysis of cancer trials: a new approach to the assessment of treatment. Anticancer Res. (1987) 7:955–8.

10. Tsai YL ITJ, Chuang YC, Cheng YY, and Lee YC. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy combined with complex decongestive therapy in patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema: A systemic review and meta-analysis. JCM. (2021) 10:5970. doi: 10.3390/jcm10245970

11. Keskin D, Dalyan M, Ünsal‐Delialioğlu S, and Düzlü‐Öztürk Ü. The results of the intensive phase of complete decongestive therapy and the determination of predictive factors for response to treatment in patients with breast cancer related‐lymphedema. Cancer Rep. (2020) 3:e1225. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1225

12. Mobarakeh ZS, Mokhtari-Hesari P, Lotfi-Tokaldany M, Montazeri A, Heidari M, and Zekri F. Combined decongestive therapy and reduction of pain and heaviness in patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer. (2019) 27:3805–11. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04681-9

13. Yang F-A, Wu P-J, Su Y-T, Strong P-C, Chu Y-C, and Huang C-C. Effect of kinesiology taping on breast cancer-related lymphedema: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Breast Cancer. (2024) 24:541–551.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2024.04.013

14. Malicka I, Rosseger A, Hanuszkiewicz J, and Woźniewski M. Kinesiology Taping reduces lymphedema of the upper extremity in women after breast cancer treatment: a pilot study. Prz Menopauzalny. (2014) 13:221–6. doi: 10.5114/pm.2014.44997

15. Reger M, Kutschan S, Freuding M, Schmidt T, Josfeld L, and Huebner J. Water therapies (hydrotherapy, balneotherapy or aqua therapy) for patients with cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2022) 148:1277–97. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-03947-w

16. Tidhar D and Katz-Leurer M. Aqua lymphatic therapy in women who suffer from breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema: a randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer. (2010) 18:383–92. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0669-4

17. Bani Mohammad E and Ahmad M. Virtual reality as a distraction technique for pain and anxiety among patients with breast cancer: A randomized control trial. Palliat Support Care. (2019) 17:29–34. doi: 10.1017/S1478951518000639

18. Ha K-J, Lee S-Y, Lee H, and Choi S-J. Synergistic effects of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and manual lymphatic drainage in patients with mastectomy-related lymphedema. Front Physiol. (2017) 8:959. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00959

19. Zhu J, Chen X, Zhen X, Zheng H, Chen H, Chen H, et al. Meta-analysis of effects of yoga exercise intervention on sleep quality in breast cancer patients. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1146433. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1146433

20. Calvo S, González C, Lapuente-Hernández D, Cuenca-Zaldívar JN, Herrero P, and Gil-Calvo M. Are physical therapy interventions effective in improving sleep in people with chronic pain? A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med. (2023) 111:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2023.09.008

21. Li L, Wang Y, Cai M, and Fan T. Effect of different exercise types on quality of life in patients with breast cancer: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Breast. (2024) 78:103798. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2024.103798

22. Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Papakonstantinou T, Chaimani A, Del Giovane C, Egger M, et al. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PloS Med. (2020) 17:e1003082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003082

23. Papakonstantinou T, Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Egger M, and Salanti G. CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Syst Rev. (2020) 16:e1080. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1080

24. Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, and Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PloS One. (2013) 8:e76654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654

25. Mavridis D, White IR, Higgins JPT, Cipriani A, and Salanti G. Allowing for uncertainty due to missing continuous outcome data in pairwise and network meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2015) 34:721–41. doi: 10.1002/sim.6365

26. Atef D, Elkeblawy MM, El-Sebaie A, and Abouelnaga WAI. A quasi-randomized clinical trial: virtual reality versus proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation for postmastectomy lymphedema. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. (2020) 32:29. doi: 10.1186/s43046-020-00041-5

27. Ali KM, El Gammal ER, and Eladl HM. Effect of aqua therapy exercises on postmastectomy lymphedema: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Rehabil Med. (2021) 45:131–40. doi: 10.5535/arm.20127

28. Bahtiyarca ZT, Can A, Ekşioğlu E, and Çakcı A. The addition of self-lymphatic drainage to compression therapy instead of manual lymphatic drainage in the first phase of complex decongestive therapy for treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized-controlled, prospective study. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. (2019) 65:309–17. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2019.3126

29. Belmonte R, Tejero M, Ferrer M, Muniesa JM, Duarte E, Cunillera O, et al. Efficacy of low-frequency low-intensity electrotherapy in the treatment of breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a cross-over randomized trial. Clin Rehabil. (2012) 26:607–18. doi: 10.1177/0269215511427414

30. Bloomquist K, Krustrup P, Fristrup B, Sørensen V, Helge JW, Helge EW, et al. Effects of football fitness training on lymphedema and upper-extremity function in women after treatment for breast cancer: a randomized trial. Acta Oncol. (2021) 60:392–400. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1868570

31. Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. (2012) 118:3766–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702

32. Buchan J, Janda M, Box R, Schmitz K, and Hayes S. A randomized trial on the effect of exercise mode on breast cancer-related lymphedema. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2016) 48:1866–74. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000988

33. Chandwani KD, Perkins G, Nagendra HR, Raghuram NV, Spelman A, Nagarathna R, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:1058–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2752

34. Chaoul A, Milbury K, Spelman A, Basen-Engquist K, Hall MH, Wei Q, et al. Randomized trial of Tibetan yoga in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer. (2018) 124:36–45. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30938

35. Conejo I, Pajares B, Alba E, and Cuesta-Vargas AI. Effect of neuromuscular taping on musculoskeletal disorders secondary to the use of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer survivors: a pragmatic randomised clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2018) 18:180. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2236-3

36. Lee K-J and An K-O. Impact of high-intensity circuit resistance exercise on physical fitness, inflammation, and immune cells in female breast cancer survivors: A randomized control trial. IJERPH. (2022) 19:5463. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095463

37. Littman AJ, Bertram LC, Ceballos R, Ulrich CM, Ramaprasad J, McGregor B, et al. Randomized controlled pilot trial of yoga in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: effects on quality of life and anthropometric measures. Support Care Cancer. (2012) 20:267–77. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1066-8

38. Liu W, Liu J, Ma L, and Chen J. Effect of mindfulness yoga on anxiety and depression in early breast cancer patients received adjuvant chemotherapy: a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2022) 148:2549–60. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04167-y

39. Lötzke D, Wiedemann F, Rodrigues Recchia D, Ostermann T, Sattler D, Ettl J, et al. Iyengar-yoga compared to exercise as a therapeutic intervention during (Neo)adjuvant therapy in women with stage I-III breast cancer: health-related quality of life, mindfulness, spirituality, life satisfaction, and cancer-related fatigue. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2016) 2016:5931816. doi: 10.1155/2016/5931816

40. Loudon A, Barnett T, Piller N, Immink MA, and Williams AD. Yoga management of breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a randomised controlled pilot-trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2014) 14:214. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-214

41. Loudon A, Barnett T, Piller N, Immink MA, Visentin D, and Williams AD. The effects of yoga on shoulder and spinal actions for women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema of the arm: A randomised controlled pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med. (2016) 16:343. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1330-7

42. Meer TA, Noor R, Bashir MS, and Ikram M. Comparative effects of lymphatic drainage and soft tissue mobilization on pain threshold, shoulder mobility and quality of life in patients with axillary web syndrome after mastectomy. BMC Womens Health. (2023) 23:588. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02762-w

43. Michels D, König S, and Heckel A. Effects of combined exercises on shoulder mobility and strength of the upper extremities in breast cancer rehabilitation: a 3-week randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. (2023) 31:550. doi: 10.1007/s00520-023-07959-1

44. Moro T, Casolo A, Bordignon V, Sampieri A, Schiavinotto G, Vigo L, et al. Keep calm and keep rowing: the psychophysical effects of dragon boat program in breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. (2024) 32:218. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08420-7

45. Naczk A, Huzarski T, Doś J, Górska-Doś M, Gramza P, Gajewska E, et al. Impact of inertial training on muscle strength and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:3278. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063278

46. Park Y-J, Na S-J, and Kim M-K. Effect of progressive resistance exercise using Thera-band on edema volume, upper limb function, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema. J Exerc Rehabil. (2023) 19:105–13. doi: 10.12965/jer.2346046.023

47. Paulo TRS, Rossi FE, Viezel J, Tosello GT, Seidinger SC, Simões RR, et al. The impact of an exercise program on quality of life in older breast cancer survivors undergoing aromatase inhibitor therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2019) 17:17. doi: 10.1186/s12955-019-1090-4

48. Porter LS, Carson JW, Olsen M, Carson KM, Sanders L, Jones L, et al. Feasibility of a mindful yoga program for women with metastatic breast cancer: results of a randomized pilot study. Support Care Cancer. (2019) 27:4307–16. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04710-7

49. Ramadan AM, ElDeeb AM, Ramadan AA, and Aleshmawy DM. Effect of combined Kinesiotaping and resistive exercise on muscle strength and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a randomized clinical trial. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. (2024) 36:1. doi: 10.1186/s43046-023-00205-z

50. Ridner SH, Poage-Hooper E, Kanar C, Doersam JK, Bond SM, and Dietrich MS. A pilot randomized trial evaluating low-level laser therapy as an alternative treatment to manual lymphatic drainage for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Oncol Nurs Forum. (2013) 40:383–93. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.383-393

51. Siedentopf F, Utz-Billing I, Gairing S, Schoenegg W, Kentenich H, and Kollak I. Yoga for Patients with Early Breast Cancer and its Impact on Quality of Life - a Randomized Controlled Trial. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. (2013) 73:311–7.

52. Ahmed Omar MT, Abd-El-Gayed Ebid A, and El Morsy AM. Treatment of post-mastectomy lymphedema with laser therapy: double blind placebo control randomized study. J Surg Res. (2011) 165:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.050

53. Ahmed RL, Thomas W, Yee D, and Schmitz KH. Randomized controlled trial of weight training and lymphedema in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. (2006) 24:2765–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6749

54. Banasik J, Williams H, Haberman M, Blank SE, and Bendel R. Effect of Iyengar yoga practice on fatigue and diurnal salivary cortisol concentration in breast cancer survivors. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. (2011) 23:135–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00573.x

55. Basha MA, Aboelnour NH, Alsharidah AS, and Kamel FH. Effect of exercise mode on physical function and quality of life in breast cancer–related lymphedema: a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 30:2101–10. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06559-1

56. Basoglu C, Sindel D, Corum M, and Oral A. Comparison of complete decongestive therapy and kinesiology taping for unilateral upper limb breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized controlled trial. Lymphology. (2021) 54:41–51. doi: 10.2458/lymph.4680

57. Baxter GD, Liu L, Tumilty S, Petrich S, Chapple C, Anders JJ, et al. Low level laser therapy for the management of breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Lasers Surg Med. (2018) 50:924–32. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22947

58. Çakıt BD and Vural SP. Short-term effects of dry heat treatment (Fluidotherapy) in the management of breast cancer related lymphedema: A randomized controlled study. Clin Breast Cancer. (2024) 24:439–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2024.02.019

59. Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Del Moral-Avila R, Fernández-De-Las-Peñas C, and Arroyo-Morales M. The effectiveness of a deep water aquatic exercise program in cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2013) 94:221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.09.008

60. Casanovas-Álvarez A, Estanyol B, Ciendones M, Padròs J, Cuartero J, Barnadas A, et al. Effectiveness of an exercise and educational-based prehabilitation program in patients with breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy (PREOptimize) on functional outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. (2024) 104:pzae151. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzae151

61. Cho Y, Do J, Jung S, Kwon O, and Jeon JY. Effects of a physical therapy program combined with manual lymphatic drainage on shoulder function, quality of life, lymphedema incidence, and pain in breast cancer patients with axillary web syndrome following axillary dissection. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:2047–57. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-3005-1

62. Cormie P, Pumpa K, Galvão DA, Turner E, Spry N, Saunders C, et al. Is it safe and efficacious for women with lymphedema secondary to breast cancer to lift heavy weights during exercise: a randomised controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. (2013) 7:413–24. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0284-8

63. Cornette T, Vincent F, Mandigout S, Antonini MT, Leobon S, Labrunie A, et al. Effects of home-based exercise training on VO2 in breast cancer patients under adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SAPA): a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2016) 52:223–32.

64. Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, Gelmon K, Reid RD, Friedenreich CM, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. (2007) 25:4396–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024

65. Cramer H, Rabsilber S, Lauche R, Kümmel S, and Dobos G. Yoga and meditation for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors-A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. (2015) 121:2175–84. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29330

66. Da Cuña-Carrera I, Soto-González M, Abalo-Núñez R, and Lantarón-Caeiro EM. Is the absence of manual lymphatic drainage-based treatment in lymphedema after breast cancer harmful? A randomized crossover study. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:402. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020402

67. Dahhak A, Devoogdt N, and Langer D. Adjunctive inspiratory muscle training during a rehabilitation program in patients with breast cancer: an exploratory double-blind, randomized, controlled pilot study. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. (2022) 4:100196. doi: 10.1016/j.arrct.2022.100196

68. Dayes IS, Whelan TJ, Julian JA, Parpia S, Pritchard KI, D’Souza DP, et al. Randomized trial of decongestive lymphatic therapy for the treatment of lymphedema in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2013) 31:3758–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.7192

69. De Oliveira MMF, De Rezende LF, Do Amaral MTP, Pinto E Silva MP, Morais SS, and Gurgel MSC. Manual lymphatic drainage versus exercise in the early postoperative period for breast cancer. Physiother Theory Pract. (2014) 30:384–9. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.876695

70. Devoogdt N, Christiaens M-R, Geraerts I, Truijen S, Smeets A, Leunen K, et al. Effect of manual lymph drainage in addition to guidelines and exercise therapy on arm lymphoedema related to breast cancer: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5326–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5326

71. Devoogdt N, Geraerts I, Van Kampen M, De Vrieze T, Vos L, Neven P, et al. Manual lymph drainage may not have a preventive effect on the development of breast cancer-related lymphoedema in the long term: a randomised trial. J Physiother. (2018) 64:245–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2018.08.007

72. Dieli-Conwright CM, Fox FS, Tripathy D, Sami N, Van Fleet J, Buchanan TA, et al. Hispanic ethnicity as a moderator of the effects of aerobic and resistance exercise on physical fitness and quality-of-life in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. (2021) 15:127–39. doi: 10.1007/s11764-020-00918-3

73. Erden S, Yurtseven Ş, Demir SG, Arslan S, Arslan UE, and Dalcı K. Effects of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on mastectomy pain, patient satisfaction, and patient outcomes. J Perianesth Nurs. (2022) 37:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2021.08.017

74. Ergin G, Karadibak D, Sener HO, and Gurpinar B. Effects of aqua-lymphatic therapy on lower extremity lymphedema: A randomized controlled study. Lymphat Res Biol. (2017) 15:284–91. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2017.0017

75. Ergin G, Şahinoğlu E, Karadibak D, and Yavuzşen T. Effectiveness of kinesio taping on anastomotic regions in patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized controlled pilot study. Lymphat Res Biol. (2019) 17:655–60. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2019.0003

76. Esteban-Simón A, Díez-Fernández DM, Rodríguez-Pérez MA, Artés-Rodríguez E, Casimiro-Andújar AJ, and Soriano-Maldonado A. Does a resistance training program affect between-arms volume difference and shoulder-arm disabilities in female breast cancer survivors? The role of surgery type and treatments. Secondary outcomes of the EFICAN trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2024) 105:647–54. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2023.11.010

77. Eyigor S, Uslu R, Apaydın S, Caramat I, and Yesil H. Can yoga have any effect on shoulder and arm pain and quality of life in patients with breast cancer? A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2018) 32:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.04.010

78. Feyzioğlu Ö, Dinçer S, Akan A, and Algun ZC. Is Xbox 360 Kinect-based virtual reality training as effective as standard physiotherapy in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery? Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:4295–303. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05287-x

79. Garcia-Roca ME, Catalá-Vilaplana I, Hernando C, Baliño P, Salas-Medina P, Suarez-Alcazar P, et al. Effect of a long-term online home-based supervised exercise program on physical fitness and adherence in breast cancer patients: A randomized clinical trial. Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:1912. doi: 10.3390/cancers16101912

80. García-Soidán JL, Pérez-Ribao I, Leirós-Rodríguez R, and Soto-Rodríguez A. Long-term influence of the practice of physical activity on the self-perceived quality of life of women with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4986. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17144986

81. Gradalski T, Ochalek K, and Kurpiewska J. Complex decongestive lymphatic therapy with or without vodder II manual lymph drainage in more severe chronic postmastectomy upper limb lymphedema: A randomized noninferiority prospective study. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2015) 50:750–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.06.017

82. Guloglu S, Basim P, and Algun ZC. Efficacy of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation in improving shoulder biomechanical parameters, functionality, and pain after axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer: A randomized controlled study. Complementary Therapies Clin Pract. (2023) 50:101692. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101692

83. Hagstrom AD, Marshall PWM, Lonsdale C, Cheema BS, Fiatarone Singh MA, and Green S. Resistance training improves fatigue and quality of life in previously sedentary breast cancer survivors: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2016) 25:784–94. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12422

84. Haines TP, Sinnamon P, Wetzig NG, Lehman M, Walpole E, Pratt T, et al. Multimodal exercise improves quality of life of women being treated for breast cancer, but at what cost? Randomized trial with economic evaluation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2010) 124:163–75. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1126-2

85. Hemmati M, Rojhani-Shirazi Z, Zakeri ZS, Akrami M, and Salehi Dehno N. The effect of the combined use of complex decongestive therapy with electrotherapy modalities for the treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2022) 23:837. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05780-1

86. Herrero F, San Juan AF, Fleck SJ, Balmer J, Pérez M, Cañete S, et al. Combined aerobic and resistance training in breast cancer survivors: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. Int J Sports Med. (2006) 27:573–80. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865848

87. Huo M, Zhang X, Fan J, Qi H, Chai X, Qu M, et al. Short-term effects of a new resistance exercise approach on physical function during chemotherapy after radical breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:160. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-02989-1

88. Husebø AML, Dyrstad SM, Mjaaland I, Søreide JA, and Bru E. Effects of scheduled exercise on cancer-related fatigue in women with early breast cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. (2014) 2014:271828. doi: 10.1155/2014/271828

89. Jong MC, Boers I, Schouten Van Der Velden AP, Meij SVD, Göker E, Timmer-Bonte ANJH, et al. A randomized study of yoga for fatigue and quality of life in women with breast cancer undergoing (Neo) adjuvant chemotherapy. J Altern Complement Med. (2018) 24:942–53. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0191

90. Kilbreath SL, Ward LC, Davis GM, Degnim AC, Hackett DA, Skinner TL, et al. Reduction of breast lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer: a randomised controlled exercise trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2020) 184:459–67. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05863-4

91. Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM, Beith JM, Ward LC, Lee M, Simpson JM, et al. Upper limb progressive resistance training and stretching exercises following surgery for early breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2012) 133:667–76. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1964-1

92. Kim DS, Sim Y-J, Jeong HJ, and Kim GC. Effect of active resistive exercise on breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2010) 91:1844–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.09.008

93. Kozanoglu E, Basaran S, Paydas S, and Sarpel T. Efficacy of pneumatic compression and low-level laser therapy in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphoedema: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2009) 23:117–24. doi: 10.1177/0269215508096173

94. Kozanoglu E, Gokcen N, Basaran S, and Paydas S. Long-term effectiveness of combined intermittent pneumatic compression plus low-level laser therapy in patients with postmastectomy lymphedema: A randomized controlled trial. Lymphat Res Biol. (2022) 20:175–84. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2020.0132

95. Lampinen R, Lee JQ, Leano J, Miaskowski C, Mastick J, Brinker L, et al. Treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema using negative pressure massage: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2021) 102:1465–1472.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.03.022

96. Letellier M-E, Towers A, Shimony A, and Tidhar D. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized controlled pilot and feasibility study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2014) 93:751–9. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000089

97. Lin Y, Wu C, He C, Yan J, Chen Y, Gao L, et al. Effectiveness of three exercise programs and intensive follow-up in improving quality of life, pain, and lymphedema among breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled 6-month trial. Support Care Cancer. (2023) 31:9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07494-5

98. McNeely ML, Magee DJ, Lees AW, Bagnall KM, Haykowsky M, and Hanson J. The addition of manual lymph drainage to compression therapy for breast cancer related lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2004) 86:95–106. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000032978.67677.9f

99. Melgaard D. What is the effect of treating secondary lymphedema after breast cancer with complete decongestive physiotherapy when the bandage is replaced with Kinesio Textape? - A pilot study. Physiother Theory Pract (2016) 32:446–51.

100. Milne HM, Wallman KE, Gordon S, and Courneya KS. Effects of a combined aerobic and resistance exercise program in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2008) 108:279–88. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9602-z

101. Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, Harris MS, Patel SR, Hall CB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. (2007) 25:4387–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027

102. Mur-Gimeno E, Coll M, Yuguero-Ortiz A, Navarro M, Vernet-Tomás M, Noguera-Llauradó A, et al. Comparison of water- vs. land-based exercise for improving functional capacity and quality of life in patients living with and beyond breast cancer (the AQUA-FiT study): a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer. (2024) 31:815–24. doi: 10.1007/s12282-024-01596-0

103. Omar MTA, Gwada RFM, Omar GSM, El-Sabagh RM, and Mersal A-EAE. Low-intensity resistance training and compression garment in the management of breast cancer-related lymphedema: single-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Educ. (2020) 35:1101–10. doi: 10.1007/s13187-019-01564-9

104. Ozsoy-Unubol T, Sanal-Toprak C, Bahar-Ozdemir Y, and Akyuz G. Efficacy of kinesio taping in early stage breast cancer associated lymphedema: A randomized single blinded study. Lymphology. (2019) 52:166–76.

105. Pasyar N, Barshan Tashnizi N, Mansouri P, and Tahmasebi S. Effect of yoga exercise on the quality of life and upper extremity volume among women with breast cancer related lymphedema: A pilot study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2019) 42:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.08.008

106. Reul-Hirche H. Manual lymph drainage when added to advice and exercise may not be effective in preventing lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer. J Physiother. (2011) 57:258. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70059-5

107. Robb KA, Newham DJ, and Williams JE. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation vs. transcutaneous spinal electroanalgesia for chronic pain associated with breast cancer treatments. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2007) 33:410–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.020

108. Sanal-Toprak C, Ozsoy-Unubol T, Bahar-Ozdemir Y, and Akyuz G. The efficacy of intermittent pneumatic compression as a substitute for manual lymphatic drainage in complete decongestive therapy in the treatment of breast cancer related lymphedema. Lymphology. (2019) 52:82–91. doi: 10.2458/lymph.4629

109. Santagnello SB, Martins FM, de Oliveira Junior GN, de Freitas Rodrigues de Sousa J, Nomelini RS, Murta EFC, et al. Improvements in muscle strength, power, and size and self-reported fatigue as mediators of the effect of resistance exercise on physical performance breast cancer survivor women: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. (2020) 28:6075–84. doi: 10.1007/s00520-020-05429-6

110. Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Armbrust P, Schneeweiss A, Ulrich CM, and Steindorf K. Effects of resistance exercise on fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Cancer. (2015) 137:471–80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29383

111. Schmidt T, Weisser B, Jonat W, Baumann FT, and Mundhenke C. Gentle strength training in rehabilitation of breast cancer patients compared to conventional therapy. Anticancer Res. (2012) 32:3229–33.

112. El-Abd AM, Ibrahim AR, and El-Hafez HM. Efficacy of kinesiology tape versus postural correction exercises on neck disability and axioscapular muscles fatigue in mechanical neck dysfunction: A randomized blinded clinical trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2017) 21:314–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.07.008

113. Son Y-J, Lee J-H, and Choi I-R. Immediate effect of patellar kinesiology tape application on quadriceps peak moment following muscle fatigue: A randomized controlled study. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. (2020) 20:549–55.

114. Zhou R, Chen Z, Zhang S, Wang Y, Zhang C, Lv Y, et al. Effects of exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Life (Basel). (2024) 14:1011. doi: 10.3390/life14081011

115. Schmid D and Leitzmann MF. Cardiorespiratory fitness as predictor of cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. (2015) 26:272–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu250

116. Zimmer P, Esser T, Lueftner D, Schuetz F, Baumann FT, Rody A, et al. Physical activity levels are positively related to progression-free survival and reduced adverse events in advanced ER+ breast cancer. BMC Med. (2024) 22:442. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03671-x

117. Friedenreich CM, Stone CR, Cheung WY, and Hayes SC. Physical activity and mortality in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectr. (2020) 4:pkz080. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz080

118. Gathani T, Cutress R, Horgan K, Kirwan C, Stobart H, Kan SW, et al. Age and sex can predict cancer risk in people referred with breast symptoms. BMJ. (2023) 381:e073269. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-073269

119. Shao D, Zhang H, Cui N, Sun J, Li J, and Cao F. The efficacy and mechanisms of a guided self-help intervention based on mindfulness in patients with breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. (2021) 127:1377–86. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33381

120. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Guimaraes TD, Oliani AH, and De Godoy JMP. Association of Godoy & Godoy contention with mechanism with apparatus-assisted exercises in patients with arm lymphedema after breast cancer. Int J Gen Med. (2011) 4:373–6. doi: 10.1177/1534735419847276

121. Bates DO. An interstitial hypothesis for breast cancer related lymphoedema. Pathophysiology. (2010) 17:289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.10.006

122. Stanton AWB, Modi S, Mellor RH, Levick JR, and Mortimer PS. Recent advances in breast cancer-related lymphedema of the arm: lymphatic pump failure and predisposing factors. Lymphat Res Biol. (2009) 7:29–45. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2008.1026

123. De Baets L, Vets N, Emmerzaal J, Devoogdt N, and De Groef A. Altered upper limb motor behavior in breast cancer survivors and its relation to pain: A narrative review. Anat Rec (Hoboken). (2024) 307:298–308. doi: 10.1002/ar.25120

124. Da Silva TG, Rodrigues JA, Siqueira PB, Dos Santos Soares M, Mencalha AL, and De Souza Fonseca A. Effects of photobiomodulation by low-power lasers and LEDs on the viability, migration, and invasion of breast cancer cells. Lasers Med Sci. (2023) 38:191. doi: 10.1007/s10103-023-03858-3

125. Sathyanarayanan G, Vengadavaradan A, and Bharadwaj B. Role of yoga and mindfulness in severe mental illnesses: A narrative review. Int J Yoga. (2019) 12:3–28. doi: 10.4103/ijoy.IJOY_65_17

126. Fairman CM, Focht BC, Lucas AR, and Lustberg MB. Effects of exercise interventions during different treatments in breast cancer. J Community Support Oncol. (2016) 14:200–9. doi: 10.12788/jcso.0225

127. Kim TH, Chang JS, and Kong ID. Effects of exercise training on physical fitness and biomarker levels in breast cancer survivors. J Lifestyle Med. (2017) 7:55–62. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2017.7.2.55

128. Díez-Fernández DM, Esteban-Simón A, Baena-Raya A, Pérez-Castilla A, Rodríguez-Pérez MA, and Soriano-Maldonado A. Optimizing resistance training intensity in supportive care for survivors of breast cancer: velocity-based approach in the row exercise. Support Care Cancer. (2024) 32:617. doi: 10.1007/s00520-024-08824-5

129. Paskett ED and Stark N. Lymphedema: knowledge, treatment, and impact among breast cancer survivors. Breast J. (2000) 6:373–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2000.99072.x

130. Tsai H-J, Hung H-C, Yang J-L, Huang C-S, and Tsauo J-Y. Could Kinesio tape replace the bandage in decongestive lymphatic therapy for breast-cancer-related lymphedema? A pilot study. Support Care Cancer. (2009) 17:1353–60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0592-8

131. Ergin G, Şahinoğlu E, Karadibak D, and Yavuzşen T. Effect of bandage compliance on upper extremity volume in patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. (2018) 16:553–8. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2017.0060

132. Balcı NC, Yuruk ZO, Zeybek A, Gulsen M, and Tekindal MA. Acute effect of scapular proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) techniques and classic exercises in adhesive capsulitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Phys Ther Sci. (2016) 28:1219–27. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.1219

133. Wu S-C, Chuang C-W, Liao W-C, Li C-F, and Shih H-H. Using virtual reality in a rehabilitation program for patients with breast cancer: phenomenological study. JMIR Serious Games. (2024) 12:e44025. doi: 10.2196/44025

134. Bae H-R, Kim E-J, Ahn Y-C, Cho J-H, Son C-G, and Lee N-H. Efficacy of moxibustion for cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. (2024) 23:15347354241233226. doi: 10.1177/15347354241233226

135. Cağlı M, Duyur Çakıt B, and Pervane S. Efficacy of therapeutic ultrasound added to complex decongestive therapy in breast cancer-related lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. (2025). doi: 10.1089/lrb.2023.0019

136. Yao M, Peng P, Ding X, Sun Q, and Chen L. Comparison of Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Pump as Adjunct to Decongestive Lymphatic Therapy against Decongestive Therapy Alone for Upper Limb Lymphedema after Breast Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breast Care (Basel). (2024) 19:155–64. doi: 10.1159/000538940

137. Yagli NV and Ulger O. The effects of yoga on the quality of life and depression in elderly breast cancer patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2015) 21:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.01.002

138. Yuen HK and Sword D. Home-based exercise to alleviate fatigue and improve functional capacity among breast cancer survivors. J Allied Health. (2007) 36:e257–275. doi: 10.1177/15347354241233226

139. Wang J, Chen X, Wang L, Zhang C, Ma J, and Zhao Q. Does aquatic physical therapy affect the rehabilitation of breast cancer in women? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS One. (2022) 17:e0272337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272337

140. Liang Z, Zhang M, Shi F, Wang C, Wang J, and Yuan Y. Comparative efficacy of four exercise types on obesity-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2023) 66:102423. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2023.102423

141. Deng C, Wu Z, Cai Z, Zheng X, and Tang C. Conservative medical intervention as a complement to CDT for BCRL therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1361128. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1361128

142. Wahid DI, Wahyono RA, Setiaji K, Hardiyanto H, Suwardjo S, Anwar SL, et al. The effication of low-level laser therapy, kinesio taping, and endermology on post-mastectomy lymphedema: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2024) 25:3771–9. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2024.25.11.3771

143. Pildal J, Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Forfang E, Altman DG, and Gøtzsche PC. Comparison of descriptions of allocation concealment in trial protocols and the published reports: cohort study. BMJ. (2005) 330:1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38414.422650.8F

144. Teh JJ, Pascoe DJ, Hafeji S, Parchure R, Koczoski A, Rimmer MP, et al. Efficacy of virtual reality for pain relief in medical procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. (2024) 22:64. doi: 10.1186/s12916-024-03266-6

145. Chen J, Wu J, Xie X, Wu S, Yang J, Bi Z, et al. Experience of breast cancer patients participating in a virtual reality psychological rehabilitation: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. (2025) 33:122. doi: 10.1007/s00520-025-09182-6

146. Lee JH, Ku J, Cho W, Hahn WY, Kim IY, Lee S-M, et al. A virtual reality system for the assessment and rehabilitation of the activities of daily living. Cyberpsychol Behav. (2003) 6:383–8. doi: 10.1089/109493103322278763

147. Montoya D, Barria P, Cifuentes CA, Aycardi LF, Morís A, Aguilar R, et al. Biomechanical Assessment of Post-Stroke Patients’ Upper Limb before and after Rehabilitation Therapy Based on FES and VR. Sensors (Basel). (2022) 22:2693. doi: 10.3390/s22072693

148. Pourmand A, Davis S, Lee D, Barber S, and Sikka N. Emerging utility of virtual reality as a multidisciplinary tool in clinical medicine. Games Health J. (2017) 6:263–70. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2017.0046

149. Aydin M, Kose E, Odabas I, Meric Bingul B, Demirci D, and Aydin Z. The effect of exercise on life quality and depression levels of breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2021) 22:725–32. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.3.725

150. Vadiraja HS, Rao MR, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Rekha M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of yoga program on quality of life and affect in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. (2009) 17:274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.06.004

151. Vadiraja HS, Rao RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Patil S, Diwakar RB, et al. Effects of yoga in managing fatigue in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Palliat Care. (2017) 23:247–52. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_95_17

152. Vadiraja SH, Rao MR, Nagendra RH, Nagarathna R, Rekha M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of yoga on symptom management in breast cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga. (2009) 2:73–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.60048

153. Vardar Yağlı N, Şener G, Arıkan H, Sağlam M, İnal İnce D, Savcı S, et al. Do yoga and aerobic exercise training have impact on functional capacity, fatigue, peripheral muscle strength, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Integr Cancer Ther. (2015) 14:125–32. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2017.7.2.55

154. Wang C, Liu H, Shen J, Hao Y, Zhao L, Fan Y, et al. Effects of tuina combined with moxibustion on breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized cross-over controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. (2023) 22:15347354231172735. doi: 10.1177/15347354231172735

155. Wang C, Yang M, Fan Y, and Pei X. Moxibustion as a therapy for breast cancer-related lymphedema in female adults: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. (2019) 18:1534735419866919. doi: 10.1177/1534735419866919

156. Winters-Stone KM, Dobek J, Bennett JA, Nail LM, Leo MC, and Schwartz A. The effect of resistance training on muscle strength and physical function in older, postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. (2012) 6:189–99. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0210-x

157. Winters-Stone KM, Torgrimson-Ojerio B, Dieckmann NF, Stoyles S, Mitri Z, and Luoh S-W. A randomized-controlled trial comparing supervised aerobic training to resistance training followed by unsupervised exercise on physical functioning in older breast cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. (2022) 13:152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2021.08.003

158. ong SSS, Liu TW, and Ng SSM. Effects of a tailor-made yoga program on upper limb function and sleep quality in women with breast cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e35883. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.1219

159. iong Q, Luo F, Zhan J, Qiao J, Duan Y, Huang J, et al. Effect of manual lymphatic drainage combined with targeted rehabilitation therapies on the recovery of upper limb function in patients with modified radical mastectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. (2023) 69:161–70. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2023.11221

160. Zhang D, Xiong X, Ding H, He X, Li H, Yao Y, et al. Effectiveness of exercise-based interventions in preventing cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction in patients with breast cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2025) 163:104997. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2025.104997

161. Ficarra S, Thomas E, Bianco A, Gentile A, Thaller P, Grassadonio F, et al. Impact of exercise interventions on physical fitness in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review. Breast Cancer. (2022) 29:402–18. doi: 10.1007/s12282-022-01347-z

162. Campbell KL, Kam JWY, Neil-Sztramko SE, Liu Ambrose T, Handy TC, Lim HJ, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on cancer-associated cognitive impairment: A proof-of-concept RCT. Psychooncology. (2018) 27:53–60. doi: 10.1002/pon.4370

163. Kayali Vatansever A, Yavuzşen T, and Karadibak D. The reliability and validity of quality of life questionnaire upper limb lymphedema (ULL-27) Turkish patient with breast cancer related lymphedema. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:455. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00455

164. Sen EI, Arman S, Zure M, Yavuz H, Sindel D, and Oral A. Manual lymphatic drainage may not have an additional effect on the intensive phase of breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized controlled trial. Lymphat Res Biol. (2021) 19:141–50. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2020.0049

165. Singh B, Newton RU, Cormie P, Galvao DA, Cornish B, Reul-Hirche H, et al. Effects of compression on lymphedema during resistance exercise in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized, cross-over trial. Lymphology. (2015) 48:80–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38414.422650.8F

166. Singh B, Buchan J, Box R, Janda M, Peake J, Purcell A, et al. Compression use during an exercise intervention and associated changes in breast cancer-related lymphedema. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. (2016) 12:216–24. doi: 10.1111/ajco.12471

167. Song S-Y, Park J-H, Lee JS, Kim JR, Sohn EH, Jung MS, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating changes in peripheral neuropathy and quality of life by using low-frequency electrostimulation on breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. (2020) 19:1534735420925519. doi: 10.1177/1534735420925519

168. Stan DL, Croghan KA, Croghan IT, Jenkins SM, Sutherland SJ, Cheville AL, et al. Randomized pilot trial of yoga versus strengthening exercises in breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue. Support Care Cancer. (2016) 24:4005–15. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3233-z

169. Steindorf K, Schmidt ME, Klassen O, Ulrich CM, Oelmann J, Habermann N, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of resistance training in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy: results on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Ann Oncol. (2014) 25:2237–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu374

170. Sweeney FC, Demark-Wahnefried W, Courneya KS, Sami N, Lee K, Tripathy D, et al. Aerobic and resistance exercise improves shoulder function in women who are overweight or obese and have breast cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. (2019) 99:1334–45. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzz096