- 1Department of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2British Columbia Mental Health and Substance Use Services Research Institute, Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 3Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, UBC, Vancouver, BC, Canada

The present review sought to examine and summarise the unique experience of concurrent pain and psychiatric conditions, that is often neglected, within the population of homeless individuals. Furthermore, the review examined factors that work to aggravate pain and those that have been shown to improve pain management. Electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, psycINFO, and Web of Science) and the grey literature (Google Scholar) were searched. Two reviewers independently screened and assessed all literature. The PHO MetaQAT was used to appraise quality of all studies included. Fifty-seven studies were included in this scoping review, with most of the research being based in the United States of America. Several interacting factors were found to exacerbate reported pain, as well as severely affect other crucial aspects of life that correlate directly with health, within the homeless population. Notable factors included drug use as a coping mechanism for pain, as well as opioid use preceding pain; financial issues; transportation problems; stigma; and various psychiatric disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. Important pain management strategies included cannabis use, Accelerated Resolution Therapy for treating trauma, and acupuncture. The homeless population experiences multiple barriers which work to further impact their experience with pain and psychiatric conditions. Psychiatric conditions impact pain experience and can work to intensify already adverse health circumstances of homeless individuals.

Background

Homelessness is currently a significant public health issue in urban centers worldwide, and has increased recently in regions such as the West Coast of North America (1, 2). More recent data indicate that in the United States, approximately half a million people experience homelessness on a single night (1), while in Canada, more than 235,000 people experience homelessness in a given year (2). Based on this key issue, it remains a high priority for research studies to continue to identify the various factors that act to disadvantage the homeless population. In particular, the topic of pain with comorbid psychiatric conditions within the homeless population is still notably understudied, and there is an urgent need to better understand this complex biopsychosocial issue and how it effects related individuals (3, 4). Importantly, research should continue to advance and better elucidate how pain is affecting this at-risk population, as this is crucial to understand how to better address issues within the various levels of the healthcare system. It is already evident that there are a number of factors that impede homeless individuals from seeking help for pain-related conditions, including the manner in which healthcare professionals behave towards them, as well as reliable access to high-quality clinical staff who have a deeper understanding of the complexities of multimorbid mental illness (5–7).

Homelessness and precarious housing are often intertwined with various mental health disorders at a rate substantially greater than the general population (8–12). The frequency and severity of major mental illnesses are alarming, including conditions such as anxiety, major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, and many more (13). Trauma is relatively common in the homeless population (8), often occurring early in life and thus not a direct consequence of living in homeless conditions; this early trauma can therefore create a psychological vulnerability to develop subsequent mental health issues when facing the severe stressors of “life on the street” (14). Impaired mental health - on its own—creates challenges and unequal opportunities for a host of various issues pertaining to housing, employment, seeking out healthcare, and proper nutrition (7, 15–17). In addition, both psychiatric conditions (such as depression) and pain can exacerbate disadvantageous health and further feed into a negative feedback loop that creates worse health outcomes along with decreased functioning in daily life. Chronic pain is often substantial and untreated within the homeless population, and its impact can be exacerbated within a large subset of individuals experiencing psychiatric symptoms (18). Stigma and biases towards the homeless population, including by those involved with their healthcare- can have a grave effect on their treatment, potentially aiding in the development of pain (18–20). Experiencing homelessness makes acquiring health services onerous. Some examples of how this inequity manifest include the following: difficulties in obtaining a health card due to the lack of a permanent address; unable to afford necessary fees associated in treatment; making appointments via phone call; disconcerting appearance; difficulties with maintaining a physician who has the individual's extensive medical records and is able to provide consistent treatment (21–23). All these barriers then lead to the overutilization of emergency health resources (24).

The aim of the current article therefore was to (a) summarize and (b) highlight the key points and “takeaway” messages of the literature on homeless or precariously housed individuals with reported chronic pain and concurrent psychiatric conditions; additionally, (c) we also sought to summarized this information comprehensively in a table where readers can easily access the key points of these studies.

We hypothesized that the homeless or precariously housed individuals with concurrent psychiatric issues are (a) at a higher risk of having worsening of health-related issues due to the snowball effect from intertwined and complicated relationship between psychiatric illnesses, day-to-day issues including living and financial status, and pain. And for this reason, we (b) further hypothesized that this cohort would respond better in treatments that encompass the variables that simultaneously contribute to the exacerbation of health-related issues than the commonly used traditional therapies such as medication therapy and opioid replacement therapy.

Materials and methods

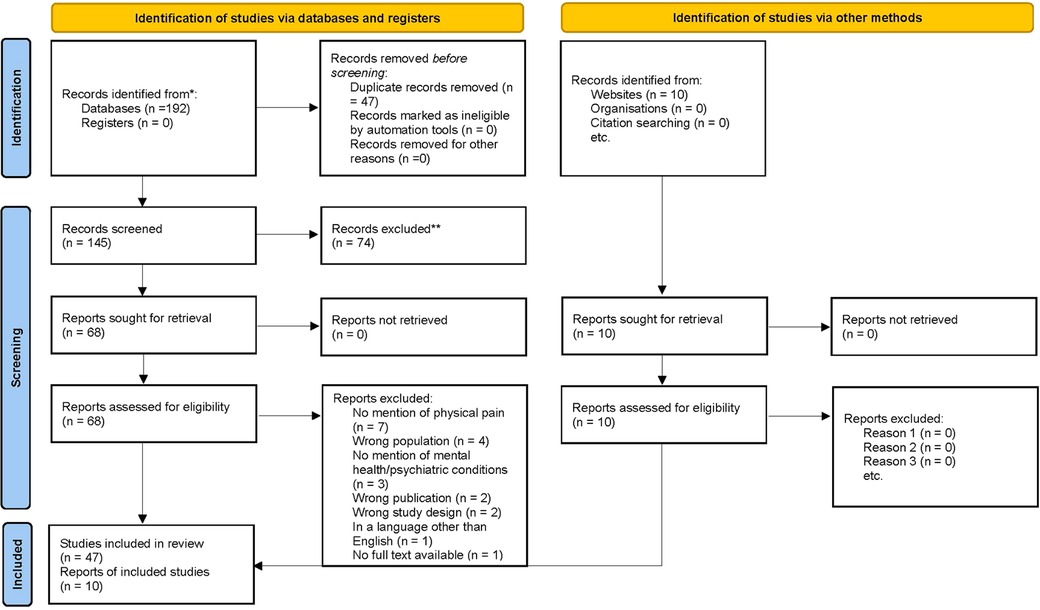

A scoping review was conducted on associated psychiatric conditions with reporting pain in the homeless population. The review was registered on the PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews [CRD42021268224]. See PRISMA checklist. While the current review did not fully satisfy the requirements PRISMA requirements for a systematic review, it incorporated many of these features to strengthen the comprehensiveness and objectivity of the review.

We approached the electronic search of articles published at any time using MEDLINE, EMBASE, psycINFO, and Web of Science, using the key words that are listed below.

1. Keywords: homeless persons/ or homeless youth/(homeless or unhoused or housing insecure).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]1 or 2

2. Keywords: exp Pain/(pain or painful or pains).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]4 or 5

3. Keywords: exp Mental Disorders/(psychological disorder or psychiatric disorder or mental illness or mental health conditions).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms]7 or 8

4. Boolean operator: 3 and 6 and 9

5. Limits Language: English language

6. Limits date: N/A

7. Limits subjects of studies: N/A

8. Selection: Removal of duplicate articles and manual disposal of articles that do not fit the criteria.

In addition, we found grey literature through utilizing google scholar and employing the keywords: homelessness, pain, and mental disorders.

We extracted articles using these search terms after consulting with a subject librarian, as conducted previously (25–27). In addition, we used search terms from published articles examining similar discourse to gain more insight. Studies were included if the article was:

1. Published in a peer-reviewed journal.

2. The study was empirical in nature.

3. It examined participants who were homeless, using Gaetz et al.'s definition (28), defined as peoples, on a spectrum, that on one end have unstable and inappropriate housing and those who are without shelter; studies that examined psychiatric or mental disorders; and investigated pain. For this review, we define homelessness using Gaetz et al.'s definition (28) which encompasses homelessness as those who fall into four categories.

a. The first being those who can be considered unsheltered, or inhabiting public or private places with no consent or contract, or those occupying a space that in not intended to be a long-term place.

b. Secondly, those who live in an emergency shelter, which can be defined as those in overnight shelters, those suffering from family violence, or people escaping from arrangements due to disaster or demolition such as fires, flooding, etc.

c. Those who are provisionally accommodated, meaning those who have accommodations without security or arrangements that are temporary.

d. Finally, those who are risk of homelessness, which includes factors such as insecure employment, unexpected unemployment, soon to be discontinued supported housing, risk of eviction, critical and continued levels of mental illness, dissolution of a household, abuse in one's current household, or institutional care that is insufficient or inappropriate.

We excluded studies that examined the history of a person or populations homelessness, who at the time of the study, were no longer homeless. Additionally, as a team, we made the decision to further exclude any case-studies, as the results from those were not as useful for our questions.

Based on the inclusion criteria of both the population of homeless adults and youth and the domain of pain and concurrent psychiatric disorders, each database was searched by the first reviewer (KR). The articles, retrieved from the respective databases, produced abstracts and titles, which were subsequently exported into Covidence. Abstracts and titles were then screened by two reviewers (KR, ES) and assessed for fitness of abstracts, based on the inclusion criteria set out. Both reviewers (KR, ES) then read the full articles thoroughly and excluded those that had focused on excluded parameters, examining the full articles for fitness, looking at factors such as study population, mean age of participants, the aim of the study, the study results, and conclusions drawn from results. Due to the nature of our review, and not wanting to exclude data, we initially did not place limitations on study design, and therefore, needed to find a more appropriate appraisal tool to assess quality of all the included study designs. Which after discussion with a subject librarian, we decided to use the PHO MetaQAT. The PHO MetaQAT is a more thorough quality appraisal tool that favours qualitative research and more easily addresses the relevancy, reliability, validity, and applicability for public health research. Covidence extracted data was then added to an excel spreadsheet to use the PHO MetaQAT, to assess quality of all included studies. Discussions surrounding what data points were appropriate for further examination were done via a conversation with one reviewer (KR) and the corresponding author (AB). Once we had a clear agreement as to what exactly we were looking for, two reviewers (KR, EMK), set out to examine the excel spreadsheet to further extract specific data of importance. If a disagreement came about, EMK and KR would both discuss their reasonings behind a recommendation and decisions were made between the reviewers. In rare circumstances, if the two reviewers could not agree, decisions were made by the corresponding author (AB). After discussion, we further excluded 3 studies which utilized a case-study method, due to the data not being generalized. The results from included studies were reported narratively.

Results

Study characteristics

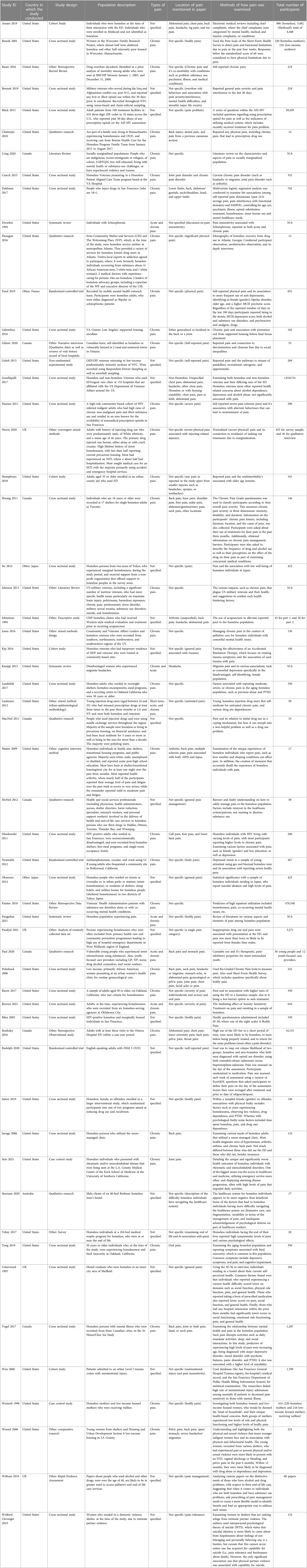

There were 57 studies included that were published over 28 years (1993–2021) (Table 1). Of the 57 studies identified, individual sample sizes ranged from 12 in Flanagan et al. (29) to 1,018,741 in Gundlapalli et al. (30). Among them, the great majority were from the United States with 41, 8 from Canada, 4 from the United Kingdom, 2 from Japan, and lastly, 1 was from France and 1 was conducted in Australia.

All literature contained investigation of mental illness or psychiatric conditions interacting with pain in unique ways. Most of the studies examined mental illness in a broad sense. The specific psychiatric conditions that were analyzed were as follows: a large proportion of the studies assessed substance use dependencies (7, 15, 16, 19, 30–44); PTSD (16, 18, 45–47); bipolar disorder (33); schizophrenia (48) and (33); depressive disorders (18, 30, 33, 39, 43, 49–53).

All studies examined pain, in differing significance, with the vast majority examining reported chronic pain. Specific examinations of pain in the various studies included pelvic pain reported from indigent women in (43), oral pain (52), headache or migraine pain (54, 49), and finally, inflammatory diseases, associated with pain, such as arthritis (54–57).

Population characteristics

In all the studies examined, the age range of participants was 19–95, with the average age roughly estimated in their 40's. Thirty nine out of 57 (68.4%) of the selected studies had a majority representation of males, 7/57 (12.3%) had solely female representation and 1/57 (0.02%) had a majority representation of females. Ten out of 57 (17.5%) did not specify gender as they were limited due to their study design (e.g., narrative review) and the questions they set out to answer. Ethnicity varied substantially across the studies, with 17/57 studies not specifying ethnicity. Twenty one out of 57 studies had a majority of Caucasian participants, 16/57 had a larger proportion of African American/Black participants, and individually Bassuk et al. (45) identified race as non-white making up 66% of their sample; Okamura et al. (51) examined individuals of Asian heritage, constituting all of their sample, and Weinreb et al. (58) studied those identifying as Puerto Rican.

Due to the complex scope of our review, and the limited literature on mental illness and reported pain in the homeless population, it is important to note that it is not possible to provide full specifics on each population studied. As anticipated, we found that the homeless populations were non-homogeneous, and there was not a common denominator for the many different cohorts that had been studied. Further descriptors to note were that 8/57 studies included homeless veterans; 37/57 studies included discourse on medical treatment and observation; 6/57 studies spoke on the unique experience of homeless women experiencing pain with regards to motherhood, sexual and physical violence, and the unique pain they experience; and finally, 2/57 studies examined homeless individuals in jail or ex-offenders.

Factors in aggravation of reporting pain in the homeless population with concurrent psychiatric conditions

Precarious housing, including homelessness, is associated with high rates of pain (4, 8, 46, 52, 55, 57, 59–61); for example, one observational study reported that 63% of homeless subjects endorsed experiencing pain lasting longer than three months (62). Living with pain disrupts securing housing (7, 16), and in turn precarious housing also has a significant impact across a wide spectrum of variables on the person experiencing pain. While living with psychiatric condition(s) alone can lead to many challenges in performing daily tasks, experiencing pain may be a significant additional stressor and add further impairment; for example, a study of 1,204 subjects with chronic disabling pain that was unresponsive to medical treatment noted that those with concurrent depression were “more likely to be unable to work because of ill health and reported greater work absence, greater pain-related interference with functioning, lower pain acceptance, and more generalised pain” compared to those without concurrent mental illness (63). Dworkin (48) examined pain insensitivity among people with schizophrenia, where this population reported significantly reduced pain sensitivity while experiencing various severe medical conditions including third-degree burns, cancer, and heart diseases at a rate presumably higher than in the general population. Substance use disorder is also related to chronic pain in various ways. For instance, it was noted that some individuals started using prescription opioids due to chronic pain [in contrast to the role of non-prescription opioids, which we recently examined in detail in the homeless population (4)]. Worsening pain, including pain from drug withdrawal or conditions such as chronic arthritis, then led to additional problems when co-occurring with an existing psychiatric condition, such as getting into financial difficulties, a worsening of housing-related problems, interpersonal problems, as well as struggles with taking care of family and other aspects of daily life (7, 16, 17, 19, 42, 64). Such challenges then also then led to disruptions in receiving appropriate treatment. For example, Opioid Use Disorder treatments can be difficult to implement effectively due to financial issues, transportation issues, associated stigma, the emotionally challenges involved with treatment, and interference in various other everyday tasks (7, 65). Thus, there is a high prevalence of reporting pain among people with substance use disorder (7, 16, 19, 35, 42, 46, 66), as well as with low mental well-being (61)—for example, it was reported that 37%–60% of patients in methadone maintenance treatment for opioid dependence exhibit concurrent chronic pain (67, 68). A large number of people experiencing pain also co-reported Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (7, 16, 35, 43, 47, 66), as well as depression and anxiety (43, 47, 64–66).

The quality of the experience while receiving medical treatment is important for patients; however, negative interactions with healthcare professionals can play a role in under-reporting pain. Possible discrimination as well as stigma associated with the healthcare system was found to be one of the main barriers to effective treatment in multiple studies (7, 18–20, 36, 53, 60). Additionally, physicians may be unwilling to prescribe pain medication due to patients' substance use history, psychiatric condition(s), and lack of compliance (17). Attempts to self-medicate pain or other health problems due to the barriers mentioned above can lead some to use illicit drugs (17, 19, 60, 69), which then puts them in situations where they face even more challenges, potentially resulting in greater social withdrawal (49). Thus, when the primary problem with pain is not effectively resolved, it may result in an exacerbation of that pain leading to further challenges and worsening of concurrent psychiatric conditions (4).

Examples of pain management with positive responses in homeless population

It is informative to describe in some detail the different approaches to pain management in the homeless and precariously housed population, such as (CBD) pills, acupuncture, and accelerated resolution therapy (ART), which examines individual's trauma to address pain, as well as depression (see below). Evidently, the management of pain within this population requires treatment that is tailored to their specific circumstances. When addressing such chronic/acute pains, it is important to think about the circumstances that these individuals find themselves in currently, in respect to their living, their food consumption, their personal healthcare options, and have previously endured, such as traumatic events including sexual assault, being a war veteran, and family abuse. Various treatment methods have been studied to suggest potential options, and below we discuss three experimental options.

A number of participants reported that using cannabis was more effective and “healthier” than the traditional psychopharmaceuticals and medication assisted substance use treatment (41). While cannabis provides a hedonic and pleasurable experience, and has been reported to help with chronic neuropathic pain (70–72), study participants noted improvement not just in chronic pain but also anxiety, depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (41). Cannabis is also seen as a form of harm reduction by some because it lessens the severity of withdrawal, while others see it as a form of treatment that helps them not only with the easing withdrawal symptoms, but also with avoiding relapse (41).

Among veterans in homeless shelters suffering from PTSD, the non-pharmacological treatment Accelerated Resolution Therapy (ART) used in treating trauma also showed improvement in symptoms of pain as well as depression, anxiety, and quality of life (47). While the improvement of symptoms was observed among those who completed ART, Kip et al. (47) acknowledged the rate of completion was low among homeless veterans when compared to their counterparts. Thus, such treatments will benefit from the development of more effective protocols to ensure treatment is completed (17, 47).

Homeless persons receiving acupuncture treatment at the Chicago Health Outreach Clinic to ease arthritis, headache, back pain, substance abuse, anxiety, fatigue, and other diagnoses reported favourable responses overall, where part of the study recorded a 97% positive response (73). The study found that even those who previously did not see much improvement or no improvement from Western medical treatments saw positive results (73). Additionally, acupuncture is cost effective with fewer severe potential side-effects compared to opioid therapy (73). Although the two-part study had a small sample size and was neither controlled nor blinded, the findings suggest that alternatives to traditional pain treatment can be studied with better designed trials to address pain and other associated comorbidities.

Discussion

This review summarized findings from articles examining the associations between pain and mental illness within the homeless population. The detailed literature was surveyed for both pain and mental illness, while examining the nature of the relationship between these two across multiple different domains. This review set out to explore the common concurrent psychiatric conditions that are associated with chronic pain in the homeless population, and furthermore, delved into factors that could aggravate the act of reporting pain in the homeless population with concurrent psychiatric conditions. The main findings from this review highlight the unique and complex difficulties presented with this population.

The literature shows that a history of stress, abuse and trauma is important to consider when examining pain. Throughout the literature, there is considerable uncertainty surrounding whether drug use precedes or follows pain, and it is evident that both scenarios do transpire. In addition, housing issues that come with being homeless, such as the vulnerability to the elements, potential violent/sexual encounters, overcrowding in shelters, the requirement to trek long distances, not having proper bedding, and many other factors have been found to worsen ill health and exacerbate pain. Furthermore, suboptimal treatment from the healthcare system has also been found to aggravate pain within this population, and prevent them from seeking out the proper care that is needed. These issues in the healthcare system can prevent individuals from receiving the appropriate care for pain as well as for psychiatric conditions. This often leads to avoidance of seeking various needed treatments and using social withdrawal as a way of coping with pain. Other significant factors include the cost of treatments, and the transportation that is often not available.

In addition to standard medications for pain relief, a small number of alternative pain therapies had been tested in the homeless and marginally housed population, although issues around experimental design, samples size and recruitment will make future studies challenging. Cannabis use was self-reported by some as a more effective and amenable substitute to other more conventional routes such as psychopharmaceuticals and medication-assisted substance use treatments. The use of acupuncture to alleviate self-reported pain within the homeless population showed a positive response. Finally, Accelerated Resolution Therapy, which bases its practice in treating trauma symptoms and the pain that is associated with said trauma (47), showed potential. However, as noted above, it is evident that there are barriers present in today's current social climate that restrict the homeless population from accessing treatments such as these to address concerns and feelings of pain.

Recommendations

1. Opioid abuse is closely associated with chronic pain related issues than other types of substance use. Therefore, harm reduction programs, such as safe consumption or injection sites, should become more available and accessible. Such initiatives should then help with minimizing potential harm from substance use, especially with opioid use, in the management of higher levels of pain.

2. Stable residence.

a. We would like to emphasize the importance of reliable and stable housing as the base of the whole treatment picture. There is an imminent need for those who present as having psychiatric needs, dealing with disabilities, are elderly, and/or are single to have affordable housing. This housing should employ competent support workers who can demonstrate thorough understanding of the unique needs of and circumstances of the cohort they are taking care of.

3. Access to support groups that are led by a qualified and licenced professional or physician would be greatly helpful in alleviating this biopsychosocial issue of pain.

4. Improvement on stigma around homeless and precariously housed individuals with psychiatric illness and pain issues among the public as well as health professionals would allow better access to health care and appropriate treatments. Raising awareness among the public about the issues that are experienced by this cohort without labeling or stereotyping, but rather with the view that they are individuals with health issues like everyone else, would improve the quality and availability of treatments. The increased awareness would also have potential to inform policy decisions and allocation of funding.

5. More research should be conducted in treating this cohort in a holistic biopsychosocial approach, attending to the unique and specific needs and circumstances, as suggested by various studies including those examined in our review. Even if we see positive results from a treatment developed for a general population, more effort to tailor treatments and approaches is needed to maximize positive outcomes in this cohort.

Limitations

Generally, there is a paucity of research that examines mental illness and pain in the homeless population, given the numbers of individuals involved, their medical complexity, and the medical resources required to address this issue. A limitation of this review includes the predominance of literature collected from North American studies, and in turn with that, our inability to include studies not published in English due to a language barrier. To overcome this limitation, our team, if greater funding were available, we could have incorporated studies printed in other languages translated into English to ensure we were obtaining a more comprehensive view of these issues across the planet. As an extension of this issue, there are considerable differences in healthcare systems and clinical resources within North America alone—based on country, state/province, and other geographic variables such as urban vs. rural. These differences make generalized inferences about treatment deficiencies for this population challenging, and recommendations for improvement are likewise difficult. While we had initially planned to use a common concept of pain when we initially started searches for literature (such as pain scores on standardized pain questionnaires), it was quickly apparent that most studies use a much more diverse set of reporting conditions when describing pain and comorbid mental illness in the homeless population. This lack of standardization means that in reviewing the literature, major themes emerge but commonalities tend to be less granular in detail across the field; thus, our review was required to examine pain in varied ways due to the diverse and unique types of pain presented within these studies. As a caveat, Matter et al. (60) noted that appropriate modifications should be applied when conducting cognitive interview processes in measuring pain among the homeless population. The majority of studies we reviewed, however, utilised pain measurement metrics that are designed for the general population, not for this specific population. With respect to bias, we have been attentive to the application of certain parts of the systematic review process and recognize the possibility for subjectivity.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources. Citation: From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights and further cements housing status as an important factor when considering an individual's current health status and the further impact housing has towards a person's health. It has become increasingly clear that the unique health determinants that this population displays have contributed toward, and is a symptom of, a widespread pandemic among people who are homeless. Due to the disparate nature of the services available for this community of peoples, it has become clear that there is not currently a comprehensive way to adequately address the unique treatment requirements of this population. With this in consideration, this results in the exacerbation of the chronic pain that is commonly experienced within this population. In the variety of support services, there needs to be enhanced training within those positions, to minimize stigma that can adversely affect and exacerbate this population's unique levels of pain in conjunction with mental illness. Additionally, healthcare workers who interact with this population, should consider gaining beneficial knowledge on pain management, in conjunction with a comprehensive education on mental health. This should also include training in integrated treatment (74), which ensures that treatment is straightforward, co-ordinated and comprehensive for the client. Integrated treatment also ensures that the client is provided with assistance not only with the concurrent disorders, but importantly in additional day-to-day aspects, including housing and employment. Furthermore, if a client's treatment services are in multiple locations, the clinical services should work together to co-ordinate treatment; a recent systematic review reported that integrated models of clinical care for those with concurrent disorders are more effective than conventional, non-integrated models (75). With respect to shelters, a valuable addition would be to implement centralized information centres, with trained mental health and pain management professionals, to ensure correct information is being communicated to this particularly vulnerable population. Shelters could also benefit from inclusion of key services such as physical therapy, and technology to facilitate pain management tools.

With regards to research, better controlled clinical trials specifically for this population need to assess interventions for pain, and how this affects concurrent mental illness. These all represent significant challenges, but given the worldwide numbers of individuals living with both pain and mental illness in housing instability, a significant amount of human suffering could be reduced by improving outcomes in this population.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KR reviewed abstracts, analyzed results and wrote the first draft of the review. ES assisted in abstract review. RMC helped with developing the Table. ENRS assisted with early stages of the systematic review formulation. AMB oversaw the project. All authors provided intellectual input into the final version of the systematic review and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Henry M, Watt R, Mahathey A, Ouellette J, Sitler A, Associates A. The 2019 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress: Part 1: Point-in-time estimates of homelessness. In: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, editor. (2020). p. 1–98.

2. Gaetz S, Dej E, Richter T, Redman M. The state of homelessness in Canada 2016. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press (2016).

3. Jones AA, Cho LL, Kim DD, Barbic SP, Leonova O, Byford A, et al. Pain, opioid use, depressive symptoms, and mortality in adults living in precarious housing or homelessness: a longitudinal prospective study. Pain. (2022) 163:2213–23. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002619.

4. Lei M, Rintoul K, Stubbs JL, Kim DD, Jones AA, Hamzah Y, et al. Characterization of bodily pain and use of both prescription and non-prescription opioids in tenants of precarious housing. Subst Use Misuse. (2021) 56(13):1951–61. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1958865

5. Ledingham E, Adams RS, Heaphy D, Duarte A, Reif S. Perspectives of adults with disabilities and opioid misuse: qualitative findings illuminating experiences with stigma and substance use treatment. Disabil Health J. (2022) 15(2s):101292. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2022.101292

6. Gilmer C, Buccieri K. Homeless patients associate clinician bias with suboptimal care for mental illness, addictions, and chronic pain. J Prim Care Community Health. (2020) 11:2150132720910289. doi: 10.1177/2150132720910289

7. Chatterjee A, Yu EJ, Tishberg L. Exploring opioid use disorder, its impact, and treatment among individuals experiencing homelessness as part of a family. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2018) 188:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.012

8. Honer WG, Cervantes-Larios A, Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Montaner JS, Tran H, et al. The hotel study-clinical and health service effectiveness in a cohort of homeless or marginally housed persons. Can J Psychiatry. (2017) 62(7):482–92. doi: 10.1177/0706743717693781

9. Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Leonova O, Langheimer V, Lang DJ, Barr AM, et al. Mortality from treatable illnesses in marginally housed adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ open. (2015) 5(8):e008876. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008876

10. Rigney G, Leith J, Lennon M, Reeves A, Chrisinger B. The association of traumatic brain injury with neurologic and psychiatric illnesses among individuals experiencing homelessness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2022) 33(2):685–701. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2022.0056

11. Jones AA, Gicas KM, Seyedin S, Willi TS, Leonova O, Vila-Rodriguez F, et al. Associations of substance use, psychosis, and mortality among people living in precarious housing or homelessness: a longitudinal, community-based study in Vancouver, Canada. PLoS Med. (2020) 17(7):e1003172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003172

12. Gicas KM, Cheng A, Panenka WJ, Kim DD, Yau JC, Procyshyn RM, et al. Differential effects of cannabis exposure during early versus later adolescence on the expression of psychosis in homeless and precariously housed adults. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2020) 106:110084. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110084

13. Schreiter S, Speerforck S, Schomerus G, Gutwinski S. Homelessness: care for the most vulnerable—a narrative review of risk factors, health needs, stigma, and intervention strategies. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2021) 34(4):400–4. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000715

14. Norman T, Resit D. Homelessness, mental health and substance use: Understanding the connections. Victoria, BC: Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research (2021).

15. MacNeil J, Pauly B. Needle exchange as a safe haven in an unsafe world. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2011) 30(1):26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00188.x

16. Salem BE, Brecht ML, Ekstrand ML, Faucette M, Nyamathi AM. Correlates of physical, psychological, and social frailty among formerly incarcerated, homeless women. Health Care Women Int. (2019) 40(7-9):788–812. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2019.1566333

17. Hwang SW, Wilkins E, Chambers C, Estrabillo E, Berends J, MacDonald A. Chronic pain among homeless persons: characteristics, treatment, and barriers to management. BMC Fam Pract. (2011) 12:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-73

18. Vogel M, Frank A, Choi F, Strehlau V, Nikoo N, Nikoo M, et al. Chronic pain among homeless persons with mental illness. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass). (2017) 18(12):2280–8. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw324

19. McNeil R, Guirguis-Younger M. Illicit drug use as a challenge to the delivery of end-of-life care services to homeless persons: perceptions of health and social services professionals. Palliat Med. (2012) 26(4):350–9. doi: 10.1177/0269216311402713

20. Sturman N, Matheson D. “I just hope they take it seriously”: homeless men talk about their health care. Aust Health Rev. (2020) 44(5):748–54. doi: 10.1071/AH19070

21. Khandor E, Mason K, Chambers C, Rossiter K, Cowan L, Hwang SW. Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: results from the street health survey. Open Med. (2011) 5(2):e94–e103. PMID: 21915240.21915240

22. Campbell DJ, O'Neill BG, Gibson K, Thurston WE. Primary healthcare needs and barriers to care among calgary's homeless populations. BMC Fam Pract. (2015) 16:139. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0361-3

23. Gunner E, Chandan SK, Marwick S, Saunders K, Burwood S, Yahyouche A, et al. Provision and accessibility of primary healthcare services for people who are homeless: a qualitative study of patient perspectives in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. (2019) 69(685):e526–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp19X704633

24. Hans K, Mike L, Heidel R, Benavides P, Arnce R, Talley J. Comorbid patterns in the homeless population: a theoretical model to enhance patient care. West J Emerg Med. (2022) 23(2):200–10. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.10.52539

25. Yuen JWY, Kim DD, Procyshyn RM, White RF, Honer WG, Barr AM. Clozapine-induced cardiovascular Side effects and autonomic dysfunction: a systematic review. Front Neurosci. (2018) 12:203. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00203

26. Tse L, Procyshyn RM, Fredrikson DH, Boyda HN, Honer WG, Barr AM. Pharmacological treatment of antipsychotic-induced dyslipidemia and hypertension. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. (2014) 29(3):125–37. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000014

27. Lian L, Kim DD, Procyshyn RM, Cázares D, Honer WG, Barr AM. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for early psychosis: a comprehensive systematic review. PLoS One. (2022) 17(4):e0267808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267808

28. Gaetz S, Barr C, Friesen A, Harris B, Kovacs-Burns K, Pauly B, et al. Canadian Definition of Homelessness.2012. Available from: https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/COHhomelessdefinition.pdf

29. Flanagan MW, Briggs HE. Substance abuse recovery among homeless adults in Atlanta, Georgia, and a multilevel drug abuse resiliency tool. Best Pract Ment Health. (2016) 12(1):89–109.

30. Gundlapalli AV, Jones AL, Redd A, Suo Y, Pettey WBP, Mohanty A, et al. Characteristics of the highest users of emergency services in veterans affairs hospitals: homeless and non-homeless. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2017) 238:24–7. PMID: 28679878.28679878

31. Black RA, Trudeau KJ, Cassidy TA, Budman SH, Butler SF. Associations between public health indicators and injecting prescription opioids by prescription opioid abusers in substance abuse treatment. J Opioid Manag. (2013) 9(1):5–17. doi: 10.5055/jom.2013.0142

32. Dahlman D, Kral AH, Wenger L, Hakansson A, Novak SP. Physical pain is common and associated with nonmedical prescription opioid use among people who inject drugs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. (2017) 12(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13011-017-0112-7

33. Fond G, Tinland A, Boucekine M, Girard V, Loubière S, Boyer L, et al. The need to improve detection and treatment of physical pain of homeless people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Results from the French housing first study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 88:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2018.07.021

34. Golub A, Bennett AS. Prescription opioid initiation, correlates, and consequences among a sample of OEF/OIF military personnel. Subst Use Misuse. (2013) 48(10):811–20. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.796988

35. Hansen L, Penko J, Guzman D, Bangsberg DR, Miaskowski C, Kushel MB. Aberrant behaviors with prescription opioids and problem drug use history in a community-based cohort of HIV-infected individuals. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2011) 42(6):893–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.02.026

36. Harris M. Normalised pain and severe health care delay among people who inject drugs in London: adapting cultural safety principles to promote care. Soc Sci Med. (2020) 260:113183. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113183

37. Johnson BS, Boudiab LD, Freundl M, Anthony M, Gmerek GB, Carter J. Enhancing veteran-centered care: a guide for nurses in non-VA settings. Am J Nurs. (2013) 113(7):24–39.doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000431913.50226.83

38. Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Bloom JJ, Harocopos A, Treese M. Patterns of prescription drug misuse among young injection drug users. J Urban Health. (2012) 89(6):1004–16. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9691-9

39. Nyamathi A, Branson C, Idemundia F, Reback C, Shoptaw S, Marfisee M, et al. Correlates of depressed mood among young stimulant-using homeless gay and bisexual men. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2012) 33(10):641–9. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.691605

40. Paudyal V, Ghani A, Shafi T, Punj E, Saunders K, Vohra N, et al. Clinical characteristics, attendance outcomes and deaths of homeless persons in the emergency department: implications for primary health care and community prevention programmes. Public Health. (2021) 196:117–23. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.05.007

41. Paul B, Thulien M, Knight R, Milloy MJ, Howard B, Nelson S, et al. “Something that actually works”: cannabis use among young people in the context of street entrenchment. PLoS One. (2020) 15(7):e0236243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236243

42. Rudolph KE, Díaz I, Hejazi NS, van der Laan MJ, Luo SX, Shulman M, et al. Explaining differential effects of medication for opioid use disorder using a novel approach incorporating mediating variables. Addiction. (2021) 116(8):2094–103. doi: 10.1111/add.15377

43. Wenzel SL, Hambarsoomian K, D’Amico EJ, Ellison M, Tucker JS. Victimization and health among indigent young women in the transition to adulthood: a portrait of need. J Adolesc Health. (2006) 38(5):536–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.019

44. Witham G, Galvani S, Peacock M. End of life care for people with alcohol and drug problems: findings from a rapid evidence assessment. Health Soc Care Community. (2019) 27(5):e637–50. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12807

45. Bassuk EL, Dawson R, Perloff J, Weinreb L. Post-traumatic stress disorder in extremely poor women: implications for health care clinicians. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). (2001) 56(2):79–85. PMID: 11326804.11326804

46. Landefeld JC, Miaskowski C, Tieu L, Ponath C, Lee CT, Guzman D, et al. Characteristics and factors associated with pain in older homeless individuals: results from the health outcomes in people experiencing homelessness in older middle age (HOPE HOME) study. J Pain. (2017) 18(9):1036–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.03.011

47. Kip KE, D'Aoust RF, Hernandez DF, Girling SA, Cuttino B, Long MK, et al. Evaluation of brief treatment of symptoms of psychological trauma among veterans residing in a homeless shelter by use of accelerated resolution therapy. Nurs Outlook. (2016) 64(5):411–23. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.04.006

48. Dworkin RH. Pain insensitivity in schizophrenia: a neglected phenomenon and some implications. Schizophr Bull. (1994) 20(2):235–48. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.2.235

49. Kneipp SM, Beeber L. Social withdrawal as a self-management behavior for migraine: implications for depression comorbidity among disadvantaged women. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. (2015) 38(1):34–44. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000059

50. Miaskowski C, Penko JM, Guzman D, Mattson JE, Bangsberg DR, Kushel MB. Occurrence and characteristics of chronic pain in a community-based cohort of indigent adults living with HIV infection. J Pain. (2011) 12(9):1004–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.002

51. Okamura T, Ito K, Morikawa S, Awata S. Suicidal behavior among homeless people in Japan. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2014) 49(4):573–82. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0791-y

52. Tong M, Tieu L, Lee CT, Ponath C, Guzman D, Kushel M. Factors associated with food insecurity among older homeless adults: results from the HOPE HOME study. J Public Health (Oxf). (2019) 41(2):240–9. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy063

53. Wolford-Clevenger C, Smith PN, Kuhlman S, D'Amato D. A preliminary test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide in women seeking shelter from intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. (2019) 34(12):2476–97. doi: 10.1177/0886260516660974

54. Creech SK, Johnson E, Borgia M, Bourgault C, Redihan S, O’Toole TP. Identifying mental and physical health correlates of homelessness among first-time and chronically homeless veterans. J Community Psychol. (2015) 43(5):619–27. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21707

55. Ronksley PE, Liu EY, McKay JA, Kobewka DM, Rothwell DM, Mulpuru S, et al. Variations in resource intensity and cost among high users of the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. (2016) 23(6):722–30. doi: 10.1111/acem.12939

56. Savage CL, Lindsell CJ, Gillespie GL, Dempsey A, Lee RJ, Corbin A. Health care needs of homeless adults at a nurse-managed clinic. J Community Health Nurs. (2006) 23(4):225–34. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2304_3

57. Seto R, Mathias K, Ward NZ, Panush RS. Challenges of caring for homeless patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal disorders in Los Angeles. Clin Rheumatol. (2021) 40(1):413–20. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05505-6

58. Weinreb L, Goldberg R, Perloff J. Health characteristics and medical service use patterns of sheltered homeless and low-income housed mothers. J Gen Intern Med. (1998) 13(6):389–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00119.x

59. Gabrielian S, Burns AV, Nanda N, Hellemann G, Kane V, Young AS. Factors associated with premature exits from supported housing. Psychiatr Serv. (2016) 67(1):86–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400311

60. Matter R, Kline S, Cook KF, Amtmann D. Measuring pain in the context of homelessness. Qual Life Res. (2009) 18(7):863–72. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9507-x

61. Ito K, Morikawa S, Okamura T, Shimokado K, Awata S. Factors associated with mental well-being of homeless people in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2014) 68(2):145–53. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12108

62. Fisher R, Ewing J, Garrett A, Harrison EK, Lwin KK, Wheeler DW. The nature and prevalence of chronic pain in homeless persons: an observational study. F1000Res. (2013) 2:164. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-164.v1

63. Rayner L, Hotopf M, Petkova H, Matcham F, Simpson A, McCracken LM. Depression in patients with chronic pain attending a specialised pain treatment centre: prevalence and impact on health care costs. Pain. (2016) 157(7):1472–9. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000542

64. Riley ED, Wu AW, Perry S, Clark RA, Moss AR, Crane J, et al. Depression and drug use impact health status among marginally housed HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. (2003) 17(8):401–6. doi: 10.1089/108729103322277411

65. Poleshuck EL, Giles DE, Tu X. Pain and depressive symptoms among financially disadvantaged women’s health patients. J Women’s Health (2002). (2006) 15(2):182–93. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.182

66. Pangarkar SS, Chang LE. Chronic pain management in the homeless population. In: Ritchie EC, Llorente MD, editors. Clinical management of the homeless patient: Springer (2021). p. 41–68.

67. Jamison RN, Kauffman J, Katz NP. Characteristics of methadone maintenance patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2000) 19(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00144-X

68. Rosenblum A, Joseph H, Fong C, Kipnis S, Cleland C, Portenoy RK. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic pain among chemically dependent patients in methadone maintenance and residential treatment facilities. JAMA. (2003) 289(18):2370–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2370

69. Lankenau SE, Teti M, Silva K, Jackson Bloom J, Harocopos A, Treese M. Initiation into prescription opioid misuse amongst young injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy. (2012) 23(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.014

70. Rouhollahi E, MacLeod BA, Barr AM, Puil E. Cannabis extract CT-921 has a high efficacy-adverse effect profile in a neuropathic pain model. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2020) 14:3351–61. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S247584

71. Lo LA, MacCallum CA, Yau JC, Barr AM. Differences in those who prefer smoking cannabis to other consumption forms for mental health: what can be learned to promote safer methods of consumption? J Addict Dis. (2022):1–5. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2022.2107332

72. Lo LA, MacCallum CA, Yau JC, Panenka WJ, Barr AM. Factors associated with problematic Cannabis use in a sample of medical Cannabis dispensary users. Psychiatry Clin Psychopharmacol. (2022) 32:262–7. doi: 10.5152/pcp.2022.22358

73. Johnstone H, Marcinak J, Luckett M, Scott J. An evaluation of the treatment effectiveness of the Chicago health outreach acupuncture clinic. J Holistic Nurs. (1994) 12(2):171–83. doi: 10.1177/089801019401200207

74. Skinner WJW, O'Grady CP, Bartha C, Parker C. Concurrent substance use and mental health disorders. An information guide. Toronto, Canada: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (2010).

Keywords: chronic pain, mental illness, psychiatric morbidity, homeless, systematic reviews

Citation: Rintoul K, Song E, McLellan-Carich R, Schjelderup ENR and Barr AM (2023) A scoping review of psychiatric conditions associated with chronic pain in the homeless and marginally housed population. Front. Pain Res. 4:1020038. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2023.1020038

Received: 15 August 2022; Accepted: 13 April 2023;

Published: 28 April 2023.

Edited by:

Albert Dahan, Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), NetherlandsReviewed by:

Janiece Taylor, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesHendrik Helmerhorst, Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), Netherlands

© 2023 Rintoul, Song, McLellan-Carich, Schjelderup and Barr. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alasdair M. Barr YWwuYmFyckB1YmMuY2E=

†ORCID Alasdair M. Barr orcid.org/0000-0002-3407-1574

Kathryn Rintoul

Kathryn Rintoul Esther Song

Esther Song Rachel McLellan-Carich

Rachel McLellan-Carich Elizabeth N. R. Schjelderup

Elizabeth N. R. Schjelderup Alasdair M. Barr

Alasdair M. Barr