Abstract

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) colonizes the gastrointestinal and vaginal epithelium of a significant percentage of healthy women, with potential for ascending intrauterine infection or transmission during parturition, creating a risk of serious disease in the vulnerable newborn. This review highlights new insights on the bacterial virulence determinants, host immune responses, and microbiome interactions that underpin GBS vaginal colonization, the proximal step in newborn infectious disease pathogenesis. From the pathogen perspective, the function GBS adhesins and biofilms, β-hemolysin/cytolysin toxin, immune resistance factors, sialic acid mimicry, and two-component transcriptional regulatory systems are reviewed. From the host standpoint, pathogen recognition, cytokine responses, and the vaginal mucosal and placental immunity to the pathogen are detailed. Finally, the rationale, efficacy, and potential unintended consequences of current universal recommended intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis are considered, with updates on new developments toward a GBS vaccine or alternative approaches to reducing vaginal colonization.

Summary: This review provides an update on group B Streptococcus factors promoting maternal colonization and considerations for current and developing neonatal disease prevention strategies.

Introduction

Streptococcus agalactiae [group B Streptococcus (GBS)] is an encapsulated Gram-positive bacterium that colonizes the lower gastrointestinal tract, and in females, the urogenital tract, of 20–30% of healthy human adults (1). GBS utilizes multiple adhesins and stress response mechanisms, defenses against other microbes, and immune evasion strategies to achieve persistent or intermittent vaginal colonization. During the peripartum period, GBS gains access to a new host, the immune-deficient neonate, where GBS can again serve as a commensal organism or transition to an invasive pathogen resulting in sepsis or meningitis. GBS displays an arsenal of virulence factors, including a potent hemolytic toxin and multiple surface proteins to invade host tissues, as well as molecular mimicry and proteases to impede host immune recognition and responses. Maternal screening and antibiotic therapy during labor are the current preventive measures against GBS neonatal disease. However, this early exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics alters the infant gut flora and may be accompanied with life-long consequences. This review provides a collection of recent findings on the epidemiology, molecular pathogenesis and host immune responses related to GBS vaginal colonization, and an outlook on emerging alternative prophylactic strategies to limiting maternal vaginal colonization and neonatal exposure.

Emergence of GBS as a Human Neonatal Pathogen

In the 1970s, GBS emerged as the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in human neonates, causing over 7,000 cases of invasive neonatal infections annually in the U.S. at that time (2). Early-onset GBS disease (EOD) results from ascending infection of the womb or by neonatal acquisition during vaginal passage and manifests on days 0–6 of life with pneumonia or respiratory distress commonly advancing to sepsis. Late-onset disease (LOD) is classified with onset from days 7 to 90, arising from maternal, nosocomial, or community sources, and presents with bacteremia with a high complication rate of meningitis (3, 4). Of the children developing GBS meningitis, almost 50% will have consequences of neurological disability (5). An estimated four million newborns die each year within the first 4 weeks of life globally, and one in four of these deaths stems from severe infection including sepsis or pneumonia with 99% of neonatal deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (6). In developed countries, GBS and E. coli combined cause approximately 70% of early-onset neonatal sepsis of both term and preterm infants (7). Neonatal colonization occurs in approximately 40–75% of births from GBS colonized mothers, with 1–2% of cases leading to invasive disease (8–11). Risk factors for neonatal colonization include intrapartum fever and heavy maternal colonization, lack of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) exposure, and also African ethnicity (12). Risk factors for neonatal infection include preterm delivery <37 weeks, prolonged rupture of membranes (>18 h), intrapartum fever temperature of at least 38°C or 100.4°F, a prior infant with GBS infection, or exposure but not infection with HIV (13, 14). Infants born to GBS-positive mothers are also three times more likely to be transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (15). GBS exposure or colonization may also impact health later in childhood, as maternal GBS colonization has been associated with a significant increased risk of childhood asthma (16). Increasing in immune-compromised adults, including pregnant women, diabetics and the elderly, GBS is recognized as an invasive pathogen, with reports of sepsis, urinary tract infections, soft tissue infections, and meningitis (3).

GBS Phylogeny and Host Range

Until the 1930s, GBS was considered primarily bovine in origin and recognized as a frequent etiologic agent of mastitis (17). GBS has since been readily isolated from various mammals, reptiles, and fishes, both as a commensal and pathogen (18). GBS is now a rising concern in aquaculture, particularly the tilapia industry, causing an estimated 40 million dollar in losses annually, and serving as a potential additional route of zoonotic infection (19). Little is known about the dissemination of GBS across species; however, a cross-sectional cohort study revealed that cattle exposure was a predictor of human GBS colonization indicating interspecies transmission can occur (20). Phylogenetic analysis of bovine and human invasive GBS strains suggests that hyperinvasive human neonatal isolates have recently diverged from a bovine ancestor (17). In the 1930s, Dr. Rebecca Lancefield described two polysaccharide antigens: the conserved Group B carbohydrate, and the diverse S substance that generates type-specific antisera (21). Since then, 10 variants of the capsule have been described (Ia, Ib, and II–IX), with serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, and V most commonly isolated from humans (4, 22, 23). More recently, GBS has been classified by sequence type (ST) based on an allelic profile of seven different loci, with the majority of GBS human isolates being ST-1, ST-17, ST-19, or ST-23 (24). Diversity of the GBS polysaccharide capsule may allow for its broad range of hosts, in part through the establishment of biofilms (25).

Epidemiology of GBS Vaginal Colonization

A broad range of GBS vaginal colonization rates during pregnancy have been reported, and this variance depends on the regions or populations of individual studies as well as the method of sampling and culturing. The most recent report of global vaginal GBS colonization estimates a prevalence of 18%, after adjusting for sample collection and methodology, with the lowest regional prevalence in Southern and Eastern Asia (11–13%) and highest prevalence in the Caribbean (35%) (26). Previous global estimates were similar, falling in the range of 8–18% (27–29). Numerous risk factors for GBS vaginal colonization have been identified both biological and socioeconomic in nature. Biological factors include a history of premature rupture of membranes (PROM) (30), gastrointestinal GBS colonization (31), and increased maternal age. In one study, maternal age >36 years of age was associated with persistent colonization (32), and another demonstrated a higher GBS colonization rate in women >40 years of age (33). Ethnicity, obesity, low vitamin D intake, hygiene, sexual activity, health care occupation, and illiteracy have also been associated with GBS vaginal carriage (31, 34–36). During pregnancy, GBS vaginal colonization may be continuous, intermittent, or transient among individual women (37). The majority of GBS-positive women are stably colonized during the peripartum period; however, changes in serotype or ST or subsequent loss of specific STs have been documented (32). Many studies have examined the most common serotypes of colonizing strains in the United States and are in agreement that serotypes Ia, III, and V are the most represented serotypes (32, 38, 39) with serotype III being more likely to result in persistent colonization than Ia or V (40). Given the possibility of capsular switching, more recent studies have determined GBS STs and found STs 1, 23, and 19 the most abundant colonizing strains (32, 41). Strong biofilm formation was recently determined to be a trait of asymptomatic colonizing strains, with weak biofilm capacity present in invasive strains (42).

Bacterial Determinants of GBS Vaginal Colonization

The transient nature of GBS vaginal colonization likely reflects a combination of GBS determinants, antagonism by commensal flora, host immune responses, and changes in pregnancy status, vaginal pH and estrous cycle, among other factors which are summarized in Figure 1. One of the most critical steps in successful GBS colonization of the mucosal surface is adherence to luminal epithelial cells and/or surface host proteins. Increased GBS adherence to vaginal epithelial cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins has been observed in vitro as pH shifts from acidic to neutral, suggesting a propensity for tissue attachment at vaginal pH (43). Several specific GBS surface-expressed determinants have been shown to contribute to vaginal and cervical epithelial cell adherence, including surface serine-rich repeat (Srr) proteins, Srr-1 and Srr-2 (44, 45), alpha-like proteins (46), the pilus protein PilA of the GBS pilus island (PI)-2a (44), bacterial surface adhesins BsaB (47), BspA (48), and BibA (49). In addition, GBS pili, and other surface proteins, promote adherence to ECM constituents such as collagen (50), fibrinogen (51–53), fibronectin (52, 54–56), and laminin (57, 58), all of which have been identified in multiple vaginal proteome studies (59). Of note, GBS possesses metallopeptidases capable of cleaving all four of these ECM proteins (60), which may aid in local tissue contact and invasion, or niche establishment. GBS constituents apart from surface adherence proteins can influence cervicovaginal adherence or vaginal persistence, including particular capsular serotypes (61, 62), expression of β-hemolysin/cytolysin (β-H/C) toxin and carotenoid pigment (63, 64), and MntH, an H+-dependent manganese transporter (65).

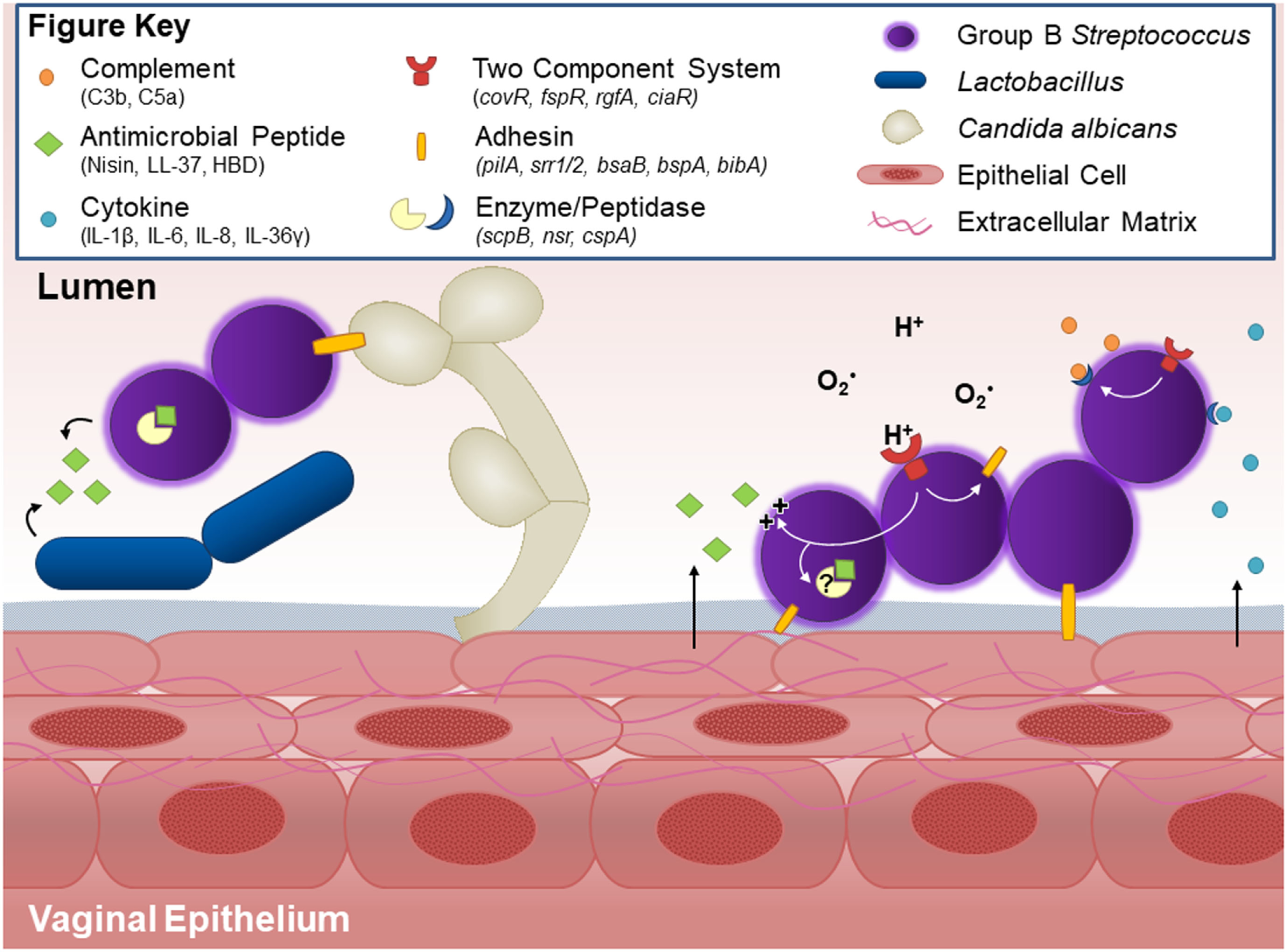

Figure 1

Host and bacterial factors contributing to group B Streptococcus (GBS) vaginal colonization. Within the vaginal tract, GBS interacts with other vaginal flora. Lactobacillus and GBS both possess antagonistic activity against each other, likely through production of antimicrobial peptides and niche competition. GBS produces countermeasures such as the protease NSR, which degrades the lantibiotic Nisin produced by Lactococcus. Other flora, such as C. albicans, facilitate GBS vaginal colonization in part through the GBS adhesion BspA. GBS binds to host vaginal epithelial cells and extracellular matrix proteins through surface adhesins including pili, Srr-1 and Srr-2, BsaB, BspA, and BibA. Upon interaction with the epithelium, GBS elicits host cytokine responses such as IL-1β, IL-8, CXCL1, and CXCL2, the latter two of which can be degraded by the serine protease CspA. The vaginal epithelium can also generate antimicrobial peptides, such as LL-37 or β-defensins, which GBS deflects with lipoteichoic acid-anchored d-alanine, or possibly degrades through yet unidentified peptidases. GBS further thwarts innate immune mechanisms by blocking capsular deposition of C3b or through degradation of C5a via ScpB. GBS uses multiple two-component systems to sense environmental conditions and regulate virulence and survival factors via response regulators such as CovR and CiaR.

Biofilm Formation and GBS Vaginal Colonization

Group B Streptococcus biofilm development appears to support vaginal tract colonization by affording protection from harsh environmental factors and host defenses (66). Acidic conditions characteristic of the vaginal tract may promote GBS biofilms (67, 68), although some studies have yielded contradictory results (69). Under acidic conditions, some hypervirulent ST-17 strains show heightened biofilm production compared with other sequences types (67), whereas in neutral conditions, neonatal ST-17 and ST-19 strains formed weaker biofilms vs. colonizing isolates (42). In addition, GBS surface proteins PI-2a and FbsC have been implicated in the formation of biofilms in vitro (66, 70, 71). GBS vaginal biofilms using in vivo models, or in human clinical observations, have not been demonstrated and future development of such models would increase our understanding of GBS colonization at the mucosal surface.

Influence of Vaginal Microbiota on GBS Colonization

In contemporary schema, the healthy human vaginal microbiome has been clustered into five different communities. Four communities are dominated by Lactobacillus species that are believed to lower the environmental pH through lactic acid production, helping protect the host from various microbial pathogens (72). During pregnancy, there is a reduction in species diversity within the vaginal microbiota, with a dominance of Lactobacillus species and the orders Lactobacillales, followed by Clostridiales, Bacteroidales, and Actinomycetales, which drive a further lowering vaginal pH to protect both mother and fetus from infection (73, 74). Whether or not GBS should be considered a native component of the vaginal microbiota is still debated. A number of recent reports have described a relative reduction of vaginal Lactobacillus populations in GBS-positive women (75–77), although other studies have failed to establish such changes (37, 78). Furthermore, an absence of Lactobacillus within the gut has been established as a risk factor for GBS vaginal colonization (31). Interestingly, an inverse relationship between Lactobacillus and GBS has also been observed in cows with subclinical mastitis (79). Certain Lactobacillus strains have the capacity to inhibit GBS adherence to vaginal epithelial cells (80, 81), and antimicrobial activity of Lactobacillus against GBS has been documented in vitro (82) and reduction of colonization seen in vivo (83, 84). Although the full complexity of the vaginal microbiome is only now being characterized, preliminary in vitro studies have begun to probe GBS communication and cooperation with other microbes in this host microenvironment. In pregnant women, GBS is frequently co-isolated with C. albicans (28, 76, 85), whereas co-isolation with other pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Trichomonas vaginalis, and Mycoplasma hominis has not been observed (28). In a recent study in non-pregnant women, GBS colonization was positively correlated with vaginal Prevotella bivia, and increased rates of GBS colonization were observed in the non-Lactobacillus dominated vaginal community state type IV-A (86). GBS binds directly to C. albicans, in part through interactions facilitated by the surface-anchored BspA protein, which also assists in epithelial cell adherence (48). GBS also utilizes products derived from vaginal microbes, such as exogenous 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, to stimulate its own respiratory metabolism (87). Moreover, in vitro studies suggest GBS may exchange quorum sensing molecules with other Streptococcus species to reciprocally influence each other’s gene expression (88). The presence of GBS may also affect the virulence properties of other reproductive tract pathogens. For example, GBS culture supernatants increase production of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 in Staphylococcus aureus (89), and these two organisms are frequently co-isolated from vaginal swabs (90, 91) as well as the infant nasopharynx (92). GBS possesses several resistance mechanisms for competing with the dominant Lactobacillus spp. and other native flora. These include the manganese transporter MntH that supports GBS growth during lactic acid exposure (65). GBS is inherently resistant to the antimicrobial activity of nisin, a lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis, through the action of SaNSR, a nisin-degrading enzyme that cleaves off the terminal six amino acids of the peptide to dramatically reduce (100-fold) its bactericidal activity (93, 94). GBS can also inhibit the growth of groups A, B, C, and G streptococci, Gardnerella vaginalis, lactobacilli, and diphtheroids under in vitro coculture conditions (95). Interestingly, GBS was never isolated with other β-hemolytic streptococci in a clinical study of vaginal swabs (90) or infant nasopharyngeal swabs (92). However, more studies are required to fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing GBS persistence and competition among the normal vaginal microbiota.

Regulatory Systems Influencing GBS Pathogenicity

Group B Streptococcus has several genetically encoded regulatory systems in place that impact the transition from a commensal niche (e.g., vaginal or gastrointestinal tract) to invasive niches (e.g., blood, lungs, or brain). Like many bacterial pathogens, GBS respond to changes in environmental stimuli using two-component systems (TCS), which typically consist of a membrane-associated histidine kinase, with a sensor or input domain and an intracellular kinase domain, and a cytoplasmic transcriptional response regulator (96, 97). Sequence analyses reveal that GBS strains typically have 17–21 TCS (98–100), a curious abundance compared with the related important human streptococcal pathogens S. pneumoniae (~14 TCS) and S. pyogenes (~13 TCS), suggesting that GBS may have a more nuanced capacity to sense and respond to various environmental conditions within the host (98). GBS TCS have important roles in controlling virulence, adherence, resistance to host defenses, and bacterial metabolism. The most well-characterized GBS TCS to date is the sensor histidine kinase CovS (Cov = control of virulence) coupled to response regulator CovR, which coordinately regulate up to 27% of the entire genome (101). CovR/S has largely inhibitory effects on virulence gene expression, including downregulation of fibrinogen-binding proteins A, B, and C (FbsA, FbsB, and FbsC), multiple non-pilus adherence factors, genes involved in iron uptake, and the cyl operon implicated in production of the β-H/C toxin and antioxidant carotenoid pigment (43, 66, 102–104). TCS RgfA/C controls expression of the GBS C5a peptidase, which inactivates a critical host complement-derived chemokine, as well as expression of several surface proteins including fibrinogen-binding proteins FbsA and FbsB (99, 105, 106). The recently characterized TCS HssRS senses and regulates heme utilization and metabolism critical for colonization of blood-rich organs (107). TCS CiaR/H promotes GBS oxidant resistance and intracellular trafficking, and by regulating several putative peptidases may enhance GBS resistance to endogenous host antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) (108, 109). Likewise, TCS LiaR/S responds to host AMPs acting on cell wall integrity to modulate cell wall synthesis (110), and TCS DltR/S maintains levels of d-alanine in GBS cell wall lipoteichoic acid (LTA) to increase AMP resistance (111). By coordinately regulating virulence factors, stress response, and AMP sensitivity, GBS mutants deficient in several of the above TCS (with the exception of RgfA/C) have been shown to have attenuated virulence in vivo. Conversely, mutation in one TCS BgrR/S that controls expression of the β-antigen (bac gene) is associated with increased GBS virulence in a mouse sepsis model (112). With respect to GBS vaginal colonization, only the CovR/S system has been proven to regulate vaginal epithelial cell attachment and promote vaginal persistence in vivo (43, 63, 99). Recently identified TCS FspS/R regulates fructose metabolism and plays a role in GBS vaginal colonization (99), but its effect on vaginal epithelial cell attachment per se has not been studied. Likewise, TCS NsrR/K senses and regulates resistance genes involved in lantibiotic resistance, which theoretically could enable GBS to better compete against lantibiotic-producing mucosal flora (113), although this has not yet been confirmed in vivo.

GBS Interaction with Host Innate Immune Receptors

Immediate host recognition of invading bacterial pathogens includes complement deposition and engagement of receptors for pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including toll-like receptors (TLRs) (114). GBS has a number of factors to counteract the opsonizing effects of complement, including its surface polysaccharide capsule, which prevents C3b deposition (115, 116), and lessens host production of C5a (117); C5a levels are further degraded by the specific GBS peptidase ScpB (118, 119). GBS also thwarts the complement system through a secreted complement interfering protein (CIP) (120), surface protein BibA (49), and binding of inhibitory complement factor H to the surface-expressed β-protein (Bac) (121) and streptococcal histidine triad (122). TLRs implicated in GBS recognition including TLR2 and TLR6 which engage cell wall LTA and lipoproteins (123, 124), and processes of intracellular sensing by endosomal TLR7 (125) and the murine endosomal TLR13 (124, 126). TLR signaling activates adaptor protein MyD88 and GBS-induced NF-κB translocation, and phagocyte generation of reactive oxygen species (though not phagocytosis itself) is significantly impaired in MyD88−/− mice (127). In macrophages, MyD88 and fellow TLR adaptor UNC-93 signaling elicit the production multiple cytokines in response to GBS (128). Compared with WT mice, TLR2- and MyD88-deficient animals were less able to control systemic GBS infection at lower doses, but conversely, were protected from cytokine storm induced by lethal GBS challenge, highlighting the importance of MyD88 in the magnitude to host cytokine response to the pathogen (129). In contrast to other pyogenic bacterial pathogens such as S. aureus, intracellular NOD2 receptor signaling was not critical in host defense against GBS (130, 131).

GBS Sialic Acid Molecular Mimicry and Siglecs

Another unique mechanism by which GBS evades innate immunity is through molecular mimicry of a critical host glycan. All GBS capsular polysaccharide serotypes present a prominent α2,3-linked terminal sialic acid in their repeat units, which is precisely identical to a common host cell epitope present on glycolipids and glycoproteins decorating the surface of all mammalian cells (132). A family of inhibitory leukocyte receptors, the sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs), plays an important role in immune homeostasis by recognizing sialic acid as a “self” epitope, and GBS molecular mimicry allows inhibitory Siglec engagement to downregulate macrophage and neutrophil responses including phagocytosis, oxidative burst, cytokine release and bacterial killing (133–138). Interestingly, the surface-anchored β-protein present in some GBS strains can engage inhibitory Siglec-5 on human macrophages in a sialic-acid-independent manner but still elicit promote inhibitory signaling to suppress innate immune responsiveness (135). Transgenic mice expressing a soluble form of human Siglec-9, that competitively inhibits GBS engagement of the inhibitory Siglec-9 to downregulate neutrophil function, demonstrated improved survival, suggesting a potential novel therapeutic avenue (139).

Patterns of GBS Cytokine Stimulation

Group B Streptococcus cytokine stimulation has been examined in many human immune, epithelial, and endothelial cells that comprise host barriers and defenses including dendritic cells (140), monocytes (141), lung epithelial cells (142), urinary bladder epithelial cells (143), vaginal and cervical epithelial cells (63), brain microvascular endothelial cells (144), astrocytes (145), and coronary artery endothelial cells (146). Intravenous or intraperitoneal GBS infection in mouse models induced robust production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 (147, 148); and these cytokines as well as IFN-γ, IL-8, and IL-10 were activated upon intraperitoneal challenge of humanized mice (149). Although important for control of GBS in sublethal challenge doses, TNF-α may be detrimental to the host during GBS septic shock as anti-TNF-α antibody treatment reduced mortality upon high-dose GBS challenge (129, 150). IL-1β contributes to CXCL1 and CXCL2 chemokine signaling resulting in neutrophil recruitment to GBS-infected tissues (151, 152), and neutrophils themselves are a key producer of IL-1β in an amplification loop for innate immunity and inflammation (153). IL-1 receptor signaling contributes to host clearance of GBS, even at sublethal doses (152). IFN-γ, as well as IFN-γ inducers IL-12 and IL-18, protects the host during GBS infection (154–156). Recent studies have shown that blocking IL-10, or IL-10 deficiency, promotes resistance to GBS sepsis in part by restoring neutrophil recruitment to sites of infection (157, 158). The role of particular GBS bacterial components in modulating cytokine responses has been a subject of recent studies. The GBS protease CspA cleaves multiple CXC chemokines, but not CC chemokines (159). GBS single-stranded RNA facilitates macrophage recognition of GBS and subsequent cytokine responses via MyD88 (128). Furthermore, GBS RNA and β-H/C induce IL-1β in macrophages through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome (153, 160). β-H/C is also responsible for increased anti-inflammatory IL-10 production in macrophages, concurrent with decreased IL-12 and NOS2 expression (161). GBS GAPDH has also been linked to host immune modulation through induction of IL-10 (162). Neonatal mononuclear cells produce significantly less of the critical IFN-γ inducing cytokines IL-12 and IL-18 (163), which may be involved in protecting the host as demonstrated by increased survival and reduced GBS load with recombinant IFN-γ treatment in a neonatal sepsis model (154). Furthermore, presence of serum IFN-γ at 20 weeks gestation was more common in women clearing GBS by 37 weeks gestation compared with women who were still colonized (164). Recently, CD4+ T cells were recognized as a source of IFN-γ during GBS-induced sepsis (165).

Vaginal Immunity to GBS Infection

Studies examining potential host immune responses resulting from asymptomatic GBS vaginal colonization, or from other tissues of the female reproductive tract, are few in number. One study comparing phagocyte engulfment of GBS in colonized and non-colonized pregnant women observed that monocytes from colonized women engulfed significantly more GBS but released more superoxide extracellularly suggesting impaired or insufficient immune function may contribute to GBS vaginal persistence (166). Another work demonstrated that vaginally colonized women possessed elevated levels of IgG and IgA antibodies to GBS in cervical secretions compared with non-colonized women (167). In addition, increased levels of maternal serum IL-1β have been associated with increased risk of GBS neonatal infection and early term birth (168). Vaginal fluid collected from GBS-positive pregnant women contains higher concentrations of MMP-8 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin compared with GBS-negative samples (169). Rectal inoculation of GBS in mice stimulated vaginal secretion of IgA (170).

Until recently, GBS induction of host responses of the vaginal epithelium had not been examined. In vitro analyses of vaginal and cervical epithelial cells demonstrate robust induction of inflammation including IL-1β production and epithelial disruption by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and VEGF, and neutrophil recruitment through IL-8, CXCL1, and CXCL2, as well as inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and IL-36γ (62, 63). In murine models of vaginal colonization, GBS was found to stimulate IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17, CXCL1, TNF-α, and GM-CSF (62–64, 84). In addition, IL-17+ neutrophils and T cells, and mast cells have been implicated in GBS clearance from the vaginal tract (62, 171).

Placental Immune Responses to GBS Infection

Since GBS is capable of crossing placental barriers in utero, the final physical barrier to the developing fetus, the host responses to GBS within these tissues is actively investigated. Ascension of GBS from the vaginal tract has been observed in both non-pregnant (62) and pregnant mice (172) suggesting this is the main route by which GBS compromises placental tissues. GBS stimulates HBD-2, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α in human extraplacental or chorioamniotic membranes ex vivo (103, 173–175). In a rhesus monkey GBS infection model, increased amniotic fluid TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 occurred before uterine contractility or any clinical signs of infection, suggesting a direct role for infection in triggering preterm labor (176). Additional non-human primate GBS chorioamionitis studies demonstrated increased amniotic fluid TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-6, and fetal IL-8 along with fetal lung injury (177), combined with reduced cytokeratin and other cytoskeletal genes which may compromise fetal membrane integrity (178). In an in utero infection model, GBS β-H/C was implicated in GBS-mediated fetal injury through both NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent and -independent pathways (179). In a non-human primate model, a hyperhemolytic GBS mutant induced inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 in the amniotic fluid compared with non-hemolytic and uninfected controls (180). In a rat model of GBS-induced chorioamnionitis, IL-1β increased in both placental tissues and fetal blood followed by neutrophil invasion into the placenta (181). Up to one-fourth of invasive GBS infection during pregnancy end in stillbirth or abortion (182). Furthermore, recent work suggests that not only can GBS cause placental dysfunction but also maternal inflammation may affect offspring brain development and neurobehavioral traits particularly in male offspring (181, 183, 184).

GBS Disease in Pregnancy and In Utero Complications

While notorious for its preeminent role in neonatal infections, GBS also causes various maternal infections, with pregnant women displaying an increased incidence of invasive GBS disease, both during gestation (0.04 cases per 1,000 woman-years) and postpartum (0.49 cases per 1,000 woman-years), compared with non-pregnant women (0.02 cases per 1,000 woman-years) (182). GBS carriage is increased in women presenting with vaginitis (185) and in some cases, GBS may even be the etiologic agent of the clinical syndrome (186). GBS bacteremia without focus is also exceptionally prevalent during pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period, accounting for 75% of cases in adults. GBS vaginal colonization, particularly heavy colonization, at the time of delivery has been associated with preterm birth and premature rupture of membranes (PROM) in several individual study populations (9, 187–190), but not in one systematic review (191). GBS ascension of the reproductive tract during pregnancy may result in intra-amniotic infection, chorioamnionitis, or stillbirth (13, 192–195), and GBS burden is increased in placentas from individuals with preterm birth and severe chorioamnionitis (196). Recently, a number of research groups have developed animal models of GBS ascending in utero infection to study disease mechanisms. The GBS β-H/C toxin was identified as a key virulence factor contributing to in utero infection in several such models. In ascending GBS infection during pregnancy in mice, wild-type GBS instigated more preterm birth and fetal demise, along with increased placental inflammation and fetal bacterial burdens, compared with isogenic β-H/C-deficient mutants (172). Upon direct intrauterine instillation of bacteria, β-H/C was implicated as a driver of GBS-mediated fetal injury in mice (179). Furthermore, in a non-human primate model, hyperhemolytic GBS initiated preterm birth more readily that non-hemolytic GBS controls (180). GBS hyaluronidase was another virulence determinant shown to contribute to bacterial ascension into the uterus, fetal demise, and preterm birth, and further acts to suppress uterine inflammatory responses when live GBS is recovered from uterine horns (197). These animal studies correlate well with human clinical observations regarding the GBS virulence mechanisms at play. Primary human amniotic epithelial cells and intact chorioamniotic membranes are more readily invaded or traversed by a hyperhemolytic ΔcovR mutant of GBS, compared with wild-type or β-H/C-deficient strains (103), and increased GBS hyaluronidase activity is observed in GBS clinical isolates from preterm birth cases compared with invasive neonatal or colonizing vaginal isolates (197).

GBS Urinary Tract Infection, Mastitis, and Postpartum Maternal Disease

Group B Streptococcus causes approximately 160,000 cases of urinary tract infection (UTI) annually in the U.S. (198). In up to 3.5% of pregnancies, GBS is the etiologic agent of UTI or asymptomatic bacteriuria (199, 200). Left untreated, bacteriuria may advance to acute pyelonephritis, with GBS the leading Gram-positive pathogen, representing 10% of cases in pregnancy (201). GBS bacteriuria during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of intrapartum fever, chorioamnionitis, preterm delivery, and PROM (202), and recently, was found to indicate intrapartum vaginal colonization independent of rectovaginal swab screening (203). Currently, the CDC recommends IAP treatment to all mothers with positive GBS urine cultures during pregnancy (2). The epidemiology, host response, and bacterial virulence factors influencing GBS UTI have been reviewed recently (198). Of note, multiparity is a risk factor for UTI during pregnancy (204), and this multiparous correlation has been demonstrated in GBS UTI model in aged mice (205). A contribution of β-H/C to UTI has been observed in some studies but not others (206, 207), suggesting variables such the GBS strains or murine infection model employed can influence the experimental outcome. In the postpartum period, GBS can cause symptomatic or asymptomatic mastitis in mothers and is proposed as a possible infection route for late-onset neonatal disease (192). GBS may be present in the breastmilk of 3–10% of lactating women, and in up to 20% of women with mastitis (208, 209) Interestingly, mothers who are positive for Lewis antigen system, a blood group which influences the types of human milk oligosaccharides within an individual, are less likely to be vaginally colonized by GBS and to have a colonized infant (210). Whether breastmilk is a source of GBS infant transmission, or infant protection from GBS, is still controversial. Evidence exists for both associations; GBS LOD occurs in some infants from high bacterial loads in breastmilk, yet human milk oligosaccharides are antibacterial against GBS, highlighting the need for further studies to develop recommendations for women with GBS-positive breastmilk (211, 212). Severe maternal infections have also been reported including bacteremia, endometritis, sepsis, and meningitis (192, 213).

Rational and Efficacy for GBS IAP

By the mid-1990s, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued the recommendation for intrapartum (intravenous) antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) to GBS-positive mothers, and in 2002, further recommended universal screening of pregnant women for vaginorectal colonization in weeks 35–37 of gestation (2). Oral antibiotics are not recommended, as no reduction in maternal colonization or neonatal transmission has been observed (214, 215). Current recommendations for GBS neonatal disease prevention consists of universal maternal screening for GBS in the 35–37th week of gestation, with IAP given to GBS-positive mothers during labor (2). Unfortunately, even with screening women just before full term is still not a completely accurate depiction of colonization status at delivery. In one study, over 20% of 37th week GBS-positive women were GBS-negative at the time of delivery (216). In addition, hospital compliance with CDC guidelines confounds the efficacy of IAP with as little as 65% of GBS carriers receiving IAP (217). When given correctly, IAP reduces GBS vaginal colonization to 47% after 2 h of administration, and 12% after 4 h of administration (218). Four hours of IAP with a beta-lactam has been shown to be highly effective in preventing early-onset disease (219) yet there is evidence to support treating for longer than 4 h when possible (220). Another benefit of IAP is that neonates are less likely to be colonized with GBS at birth, although maternal transmission may occur in the months following (221, 222). Furthermore, the maternal vaginal flora, including GBS, does not appear to develop selective antibiotic resistance after IAP administration (223). IAP has led to a dramatic reduction in GBS EOD to approximately 1,000 cases in the U.S. annually. Nevertheless, GBS remains the leading cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis in term infants, and late-onset occurrence remains unaffected, and may be on the rise (2, 224–226). The CDC Active Bacterial Core surveillance program currently estimates a total of 28,150 cases of GBS infection including neonatal and adult populations resulting in 1,865 deaths annually in the U.S. (227).

Potential Unintended Consequences of IAP

Whether or not IAP alters infection rates of other pathogens or increases GBS antibiotic resistance remains unclear. Some studies have alerted to the possibility of negative IAP effects including increased infections with Gram-negative bacteria such as ampicillin-resistant E. coli (228, 229), whereas others have not (230). A recent epidemiological study found an increase in GBS LOD from 1997–2001 to 2002–2010, but it is not known whether this is due to a shift in GBS pathogenicity, or due to an increase in survival of preterm infants, or delay in disease onset from IAP (226). As determined by oral swab, immediate vertical transmission of lactobacilli within hours of birth is reduced in neonates exposed to IAP (231). Several studies have recorded a reduction of fecal Bifidobacteria counts in IAP-exposed neonates at 1 week of age, but this difference may be nullified by 1 month of age (232, 233). Levels of gut lactobacilli are not altered by IAP exposure; however, and exclusively breastfed infants have higher Lactobacillus counts in the first month of life (233). A combination of IAP and emergency cesarean section may have even more pronounced effects on the infant microbiome (234). In one study, which adjusted for IAP use, infants born to GBS-positive mothers had increased abundance of Clostridiaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Enterococcaceae at 6 months of age, suggesting that GBS exposure in and of itself may alter gut composition in early life (235). Furthermore, both mother and infant are more susceptible to fungal infections postpartum when IAP is administered (236), and maternal vaginal flora is altered with exposure to antibiotics (78, 237). Apart from altered infant microbiota, IAP exposure may also predispose neonates to various health and developmental disorders. Children born to women receiving antibiotics for spontaneous preterm labor displayed increased functional impairment as well as an increased risk of cerebral palsy (238). Additional studies have examined antibiotic exposure later in infancy, where it can be speculated that at least some of the health impacts are similar. Infants exposed to prenatal antibiotics or receiving antibiotics within the first 6 months of life display increased risk of childhood obesity, or increased body mass by 2 years of age, respectively (239, 240). Maternal GBS colonization and IAP have also been associated with increased infant aortic intima-media thickness, an early marker for risk of cardiovascular disease (241). Risk of developing childhood asthma is increased with early exposure to antibiotics including administration during infancy, or in utero exposure from maternal UTI treatment (16, 242). A reduction in intestinal Bifidobacteria has been reported in children with atopic dermatitis (243), similar to the effect seen with IAP in the first 6 months of life; however, no direct correlation has been made between allergy development and maternal IAP or GBS vaginal colonization to date (244). The heightened incidence of allergies and autoimmune diseases in modern Western cultures, particularly with early childhood onset, merits further clarification of long-term impacts of IAP. In addition, adverse maternal and neonatal events resulting from IAP has been recently systematically reviewed (245). The current considerations for IAP to prevent neonatal GBS disease are summarized in Table 1 and highlight the need for more targeted or narrow spectrum prophylaxis.

Table 1

| Reference | ||

|---|---|---|

| Benefits of IAP | ||

| Maternal | Twofold to eightfold reduction in vaginal colonization at delivery | (218) |

| No increase in antibiotic resistance of vaginal flora | (223) | |

| Neonatal | Drastic reduction (>80%) in early-onset disease | (2, 219, 246, 247) |

| Reduction in colonization at birth | (221, 222) | |

| Considerations for IAP | ||

| Maternal | Increased risk of fungal infection | (236) |

| Altered vaginal flora | (78, 237) | |

| Neonatal | Increased risk of fungal infection | (236) |

| Potential increase in Gram-negative infections | (228–230) | |

| Altered transmission of maternal flora | (231) | |

| Altered gut flora | (232, 233) | |

| Increased risk of cerebral palsy | (238) | |

| Increased aortic intima-media thickness | (241) | |

Benefits and considerations for maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP).

Status of GBS Vaccine Development

In hallmark studies, Lancefield demonstrated that GBS elicits antibody production in the host in a strain-specific manner (21). For decades, we have known that humans generate serum antibodies against the GBS capsule, and these antibodies are specific to a particular serotype (248). Now recent work has attempted to identify all major GBS proteins that elicit the production of human serum antibodies (249). Antibodies mounted to GBS influence disease susceptibility in neonatal infection, as infants born to women with higher levels of anti-GBS IgG were at lower risk for early-onset disease than women with low levels of anti-GBS IgG (250). A recent murine model suggests that mucosal immunization can result in vaginal IgG production combined with enhanced GBS vaginal clearance (251). Moreover, both IgG and IgM type antibody responses are present in infants surviving meningitis, suggesting that the neonatal immune response may also participate in protection (252). Work performed by Drs. Carol Baker, Dennis Kasper and colleagues in the mid-1970s examined production of maternal IgG to GBS capsular polysaccharide types laid the foundation for the development of a GBS vaccine (253). The vaccine strategy that has progressed the furthest is a Novartis/GSK trivalent GBS conjugate vaccine (against serotypes Ia, Ib, and III), which has completed Phase II clinical trials in pregnant women (246), with Phase III trials proposed (254). This trivalent conjugate has achieved significantly higher GBS-specific titers (measured out to 90 days) in infants born to vaccinated mothers compared with placebo controls, without impacting antibody responses to diphtheria and pneumococcal vaccination (255). Furthermore, a recent study has demonstrated a striking negative correlation between GBS antibody titers in cord blood and infant colonization at birth through 90 days of life (256). GBS surface proteins have also been proposed as conserved antigens including pilus proteins (257), Srr-1 (258), alpha C protein (259), Sip, and ScpB (260). Analytic models have determined a GBS vaccine has comparable cost-effectiveness to other pediatric vaccines (261), and a combination of a GBS vaccine with ≥70% efficacy, and IAP for unimmunized women, would prevent more GBS-associated disease than the current screening/IAP at a similar cost (262). The history of vaccine development, analysis of current candidates, obstacles especially within low- and middle-income countries, and future development pathways have just recently been extensively reviewed and discussed (263, 264).

Alternative Targeted Prevention Strategies Against GBS Colonization

Several alternative strategies to prevent or limit maternal GBS colonization, in place of the current IAP or proposed vaccine candidates, have been recently explored. The first type of strategy consists of applying purified or synthetic compounds with specific antimicrobial or inhibitory activity toward GBS. Potential agents suggested thus far come from various natural or synthetic sources and have not been explored beyond preliminary in vitro and animal studies. Multiple plant-derived crude extracts and phytochemicals hinder GBS growth in minimum inhibitory concentration assays (265). For example, plant-based lipids from Aristolochia longa and Bryonia dioïca show inhibitory activity against GBS in vitro (266), as does the vaginal microbicide octylglycerol (267). Bacteriostatic synthetic polymers may represent a barrier for selectively blocking GBS adherence to the vaginal mucosa, while allowing normal constituents of the vaginal flora, such as lactobacilli, to persist (268). Recently, a synthetic peptide mimicking human C5a was shown to be directly bacteriocidal toward GBS and displayed therapeutic in vivo activity in both peritonitis and vaginal colonization mouse models (269). Although these compounds show preclinical efficacy in controlling GBS in animal models, it has yet to be established if any of them are feasible or cost-effective for human use. As an alternative to antibiotic treatment, intrapartum chlorhexidine vaginal washes have been considered, but resulted in no significant reduction of EOD, but did significantly lower neonatal colonization (270). Another alternative strategy explores the growing trend of probiotics agents to limit pathogen overgrowth while promoting healthy native vaginal flora (271, 272). To date, the most studied probiotic candidates for controlling GBS are within the Lactobacillus genus. Multiple studies have documented the inhibitory activity of lactobacilli on GBS growth in vitro including Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus gasseri, Lactobacillus salivarius, and Lactobacillus fermentum (82, 273–277). Pretreatment with L reuteri, but not a combination of L. gasseri and L. salivarius, reduced GBS vaginal colonization in a murine model (82, 83) indicating some probiotic strains may be more efficacious than others. In a recent human clinical trial, daily oral probiotic treatment of two Lactobacillus species, L. rhamnosus and L. reuteri, to GBS-positive women at the 35–37th week screening visit was found to reduce GBS colonization at the time of delivery (278). Other probiotic species such as Bifidobacterium, known to be reduced in the neonatal gut after IAP, have antibacterial activity against GBS (232). The efficacy of a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Bifidobacterium longum has been examined in one small pilot study, and while potentially effective, results did not achieve significant due to modest sample size. Nevertheless, an inverse relationship of yogurt consumption and GBS vaginal colonization was observed (279). Finally, an oral probiotic, S. salivarius, was found to inhibit GBS adherence and vaginal colonization in a mouse model (280).

Conclusion and Perspective

Over the last 50 years, GBS has remained a prominent concern for mother and neonatal health. Although universal screening and IAP have reduced the incidence of early-onset GBS sepsis, maternal and infant colonization rates remain unchanged, and LOD and potential GBS-induced preterm birth are not impacted by IAP. Recent discoveries in the molecular and microbial determinants of GBS vaginal colonization and placental disease have given a better understanding of host–microbe interactions within the female reproductive tract. Furthermore, advances in GBS vaccines and human trials, as well as the emergence of novel targeted strategies to control GBS vaginal colonization, point to a new era beyond broad-spectrum antibiotics, and its detrimental consequences, to prevent neonatal GBS pathogenesis.

Statements

Author contributions

KP designed the review layout and drafted the manuscript and tables. VN obtained funding and edited and reviewed subsequent drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

Research was supported by NIH grants to VN (HL107150 and HD090259). KP was supported through a postdoctoral fellowship from University of California Chancellor’s Postdoctoral Fellowship Program.

Acknowledgments

Portions of the manuscript were adapted from the doctoral thesis of KP (281).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

DoranKSNizetV. Molecular pathogenesis of neonatal group B streptococcal infection: no longer in its infancy. Mol Microbiol (2004) 54(1):23–31.10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04266.x

2

VeraniJRMcGeeLSchragSJDivision of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease – revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep (2010) 59(RR–10):1–36.

3

MaiseyHCDoranKSNizetV. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of group B Streptococcus virulence. Expert Rev Mol Med (2008) 10:e27.10.1017/S1462399408000811

4

EdmondKMKortsalioudakiCScottSSchragSJZaidiAKCousensSet alGroup B streptococcal disease in infants aged younger than 3 months: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet (2012) 379(9815):547–56.10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61651-6

5

BedfordHde LouvoisJHalketSPeckhamCHurleyRHarveyD. Meningitis in infancy in England and Wales: follow up at age 5 years. BMJ (2001) 323(7312):533–6.10.1136/bmj.323.7312.533

6

LawnJECousensSZupanJThe Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 Million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why?Lancet (2005) 365(9462):891–900.10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5

7

SimonsenKAAnderson-BerryALDelairSFDaviesHD. Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev (2014) 27(1):21–47.10.1128/CMR.00031-13

8

WinnHN. Group B Streptococcus infection in pregnancy. Clin Perinatol (2007) 34(3):387–92.10.1016/j.clp.2007.03.012

9

Namavar JahromiBPoorarianSPoorbarfeheeS. The prevalence and adverse effects of group B streptococcal colonization during pregnancy. Arch Iran Med (2008) 11(6):654–7.

10

ChanGJLeeACBaquiAHTanJBlackRE. Prevalence of early-onset neonatal infection among newborns of mothers with bacterial infection or colonization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis (2015) 15:118.10.1186/s12879-015-0813-3

11

BoyerKMGotoffSP. Prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease with selective intrapartum chemoprophylaxis. N Engl J Med (1986) 314(26):1665–9.10.1056/NEJM198606263142603

12

BerardiARossiCGuidottiIVellaniGLugliLBacchi ReggianiMLet alFactors associated with intrapartum transmission of group B Streptococcus. Pediatr Infect Dis J (2014) 33(12):1211–5.10.1097/INF.0000000000000439

13

SchragSGorwitzRFultz-ButtsKSchuchatA. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease: a public health perspective. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep (1996) 45(RR–7):1–24.

14

SlogroveALGoetghebuerTCottonMFSingerJBettingerJA. Pattern of infectious morbidity in HIV-exposed uninfected infants and children. Front Immunol (2016) 7:164.10.3389/fimmu.2016.00164

15

BrigtsenAKJacobsenAFDediLMelbyKKFugelsethDWhitelawA. Maternal colonization with group B Streptococcus is associated with an increased rate of infants transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit. Neonatology (2015) 108(3):157–63.10.1159/000434716

16

WuPFeldmanASRosas-SalazarCJamesKEscobarGGebretsadikTet alRelative importance and additive effects of maternal and infant risk factors on childhood asthma. PLoS One (2016) 11(3):e0151705.10.1371/journal.pone.0151705

17

BisharatNCrookDWLeighJHardingRMWardPNCoffeyTJet alHyperinvasive neonatal group B Streptococcus has arisen from a bovine ancestor. J Clin Microbiol (2004) 42(5):2161–7.10.1128/JCM.42.5.2161-2167.2004

18

BrochetMCouveEZouineMVallaeysTRusniokCLamyMCet alGenomic diversity and evolution within the species Streptococcus agalactiae. Microbes Infect (2006) 8(5):1227–43.10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.010

19

SunJFangWKeBHeDLiangYNingDet alInapparent Streptococcus agalactiae infection in adult/commercial tilapia. Sci Rep (2016) 6:26319.10.1038/srep26319

20

ManningSDSpringmanACMillionADMiltonNRMcNamaraSESomselPAet alAssociation of group B Streptococcus colonization and bovine exposure: a prospective cross-sectional cohort study. PLoS One (2010) 5(1):e8795.10.1371/journal.pone.0008795

21

LancefieldRC. A serological differentiation of specific types of bovine hemolytic streptococci (Group B). J Exp Med (1934) 59(4):441–58.10.1084/jem.59.4.441

22

BertiFCampisiETonioloCMorelliLCrottiSRosiniRet alStructure of the type IX group B Streptococcus capsular polysaccharide and its evolutionary relationship with types V and VII. J Biol Chem (2014) 289(34):23437–48.10.1074/jbc.M114.567974

23

PharesCRLynfieldRFarleyMMMohle-BoetaniJHarrisonLHPetitSet alEpidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal disease in the United States, 1999–2005. JAMA (2008) 299(17):2056–65.10.1001/jama.299.17.2056

24

JonesNBohnsackJFTakahashiSOliverKAChanMSKunstFet alMultilocus sequence typing system for group B Streptococcus. J Clin Microbiol (2003) 41(6):2530–6.10.1128/JCM.41.6.2530-2536.2003

25

XiaFDMalletACaliotEGaoCTrieu-CuotPDramsiS. Capsular polysaccharide of Group B Streptococcus mediates biofilm formation in the presence of human plasma. Microbes Infect (2015) 17(1):71–6.10.1016/j.micinf.2014.10.007

26

RussellNJSealeACO’DriscollMO’SullivanCBianchi-JassirFGonzalez-GuarinJet alMaternal colonization with group B Streptococcus and serotype distribution worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis (2017) 65(Suppl_2):S100–11.10.1093/cid/cix658

27

StollBJSchuchatA. Maternal carriage of group B streptococci in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J (1998) 17(6):499–503.10.1097/00006454-199806000-00013

28

ReganJAKlebanoffMANugentRP. The epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization in pregnancy. Vaginal infections and prematurity study group. Obstet Gynecol (1991) 77(4):604–10.

29

KwatraGCunningtonMCMerrallEAdrianPVIpMKlugmanKPet alPrevalence of maternal colonisation with group B Streptococcus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis (2016) 16(9):1076–84.10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30055-X

30

AlpFFindikDDagiHTArslanUPekinATYilmazSA. Screening and genotyping of group B Streptococcus in pregnant and non-pregnant women in Turkey. J Infect Dev Ctries (2016) 10(3):222–6.10.3855/jidc.6190

31

Le DoareKHeathPT. An overview of global GBS epidemiology. Vaccine (2013) 31(Suppl 4):D7–12.10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.009

32

ManningSDLewisMASpringmanACLehotzkyEWhittamTSDaviesHD. Genotypic diversity and serotype distribution of group B Streptococcus isolated from women before and after delivery. Clin Infect Dis (2008) 46(12):1829–37.10.1086/588296

33

KhanMAFaizAAshshiAM. Maternal colonization of group B Streptococcus: prevalence, associated factors and antimicrobial resistance. Ann Saudi Med (2015) 35(6):423–7.10.5144/0256-4947.2015.423

34

Capan-MelserMMombo NgomaGAkerey-DiopDBasraAWurbelHGrogerMet alEvaluation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria against group B Streptococcus colonization in pregnant women: a nested analysis of a randomized controlled clinical trial of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine versus mefloquine. J Antimicrob Chemother (2015) 70(6):1898–902.10.1093/jac/dkv041

35

StapletonRDKahnJMEvansLECritchlowCWGardellaCM. Risk factors for group B streptococcal genitourinary tract colonization in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol (2005) 106(6):1246–52.10.1097/01.AOG.0000187893.52488.4b

36

AkohCCPressmanEKCooperEQueenanRAPillittereJO’BrienKO. Prevalence and risk factors for infections in a pregnant adolescent population. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol (2017) 30(1):71–5.10.1016/j.jpag.2016.08.001

37

Brzychczy-WlochMPabianWMajewskaEZukMGKielbikJGosiewskiTet alDynamics of colonization with group B streptococci in relation to normal flora in women during subsequent trimesters of pregnancy. New Microbiol (2014) 37(3):307–19.

38

FerrieriPBakerCJHillierSLFloresAE. Diversity of surface protein expression in group B streptococcal colonizing & invasive isolates. Indian J Med Res (2004) 119(Suppl):191–6.

39

EdwardsMSRenchMAPalazziDLBakerCJ. Group B streptococcal colonization and serotype-specific immunity in healthy elderly persons. Clin Infect Dis (2005) 40(3):352–7.10.1086/426820

40

KwatraGAdrianPVShiriTBuchmannEJCutlandCLMadhiSA. Serotype-specific acquisition and loss of group B Streptococcus recto-vaginal colonization in late pregnancy. PLoS One (2014) 9(6):e98778.10.1371/journal.pone.0098778

41

TeateroSFerrieriPMartinIDemczukWMcGeerAFittipaldiN. Serotype distribution, population structure, and antimicrobial resistance of group B Streptococcus strains recovered from colonized pregnant women. J Clin Microbiol (2017) 55(2):412–22.10.1128/JCM.01615-16

42

ParkerRELautCGaddyJAZadoksRNDaviesHDManningSD. Association between genotypic diversity and biofilm production in group B Streptococcus. BMC Microbiol (2016) 16:86.10.1186/s12866-016-0704-9

43

ParkSEJiangSWesselsMR. CsrRS and environmental pH regulate group B Streptococcus adherence to human epithelial cells and extracellular matrix. Infect Immun (2012) 80(11):3975–84.10.1128/IAI.00699-12

44

SheenTRJimenezAWangNYBanerjeeAvan SorgeNMDoranKS. Serine-rich repeat proteins and pili promote Streptococcus agalactiae colonization of the vaginal tract. J Bacteriol (2011) 193(24):6834–42.10.1128/JB.00094-11

45

WangNYPatrasKASeoHSCavacoCKRoslerBNeelyMNet alGroup B streptococcal serine-rich repeat proteins promote interaction with fibrinogen and vaginal colonization. J Infect Dis (2014) 210(6):982–91.10.1093/infdis/jiu151

46

BaronMJBolducGRGoldbergMBAuperinTCMadoffLC. Alpha C protein of group B Streptococcus binds host cell surface glycosaminoglycan and enters cells by an actin-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(23):24714–23.10.1074/jbc.M402164200

47

JiangSWesselsMR. BsaB, a novel adherence factor of group B Streptococcus. Infect Immun (2014) 82(3):1007–16.10.1128/IAI.01014-13

48

RegoSHealTJPidwillGRTillMRobsonALamontRJet alStructural and functional analysis of cell wall-anchored polypeptide adhesin BspA in Streptococcus agalactiae. J Biol Chem (2016) 291(31):15985–6000.10.1074/jbc.M116.726562

49

SantiIScarselliMMarianiMPezzicoliAMasignaniVTaddeiAet alBibA: a novel immunogenic bacterial adhesin contributing to group B Streptococcus survival in human blood. Mol Microbiol (2007) 63(3):754–67.10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05555.x

50

BanerjeeAKimBJCarmonaEMCuttingASGurneyMACarlosCet alBacterial Pili exploit integrin machinery to promote immune activation and efficient blood-brain barrier penetration. Nat Commun (2011) 2:462.10.1038/ncomms1474

51

SchubertAZakikhanyKSchreinerMFrankRSpellerbergBEikmannsBJet alA fibrinogen receptor from group B Streptococcus interacts with fibrinogen by repetitive units with novel ligand binding sites. Mol Microbiol (2002) 46(2):557–69.10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03177.x

52

DehbashiSPourmandMRMashhadiR. Characterization of Afb, a novel bifunctional protein in Streptococcus agalactiae. Iran J Microbiol (2016) 8(1):73–9.

53

DeviASPonnurajK. Cloning, expression, purification and ligand binding studies of novel fibrinogen-binding protein FbsB of Streptococcus agalactiae. Protein Expr Purif (2010) 74(2):148–55.10.1016/j.pep.2010.07.004

54

TamuraGSRubensCE. Group B streptococci adhere to a variant of fibronectin attached to a solid phase. Mol Microbiol (1995) 15(3):581–9.10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02271.x

55

HullJRTamuraGSCastnerDG. Interactions of the streptococcal C5a peptidase with human fibronectin. Acta Biomater (2008) 4(3):504–13.10.1016/j.actbio.2008.01.009

56

ChengQStafslienDPurushothamanSSClearyP. The group B streptococcal C5a peptidase is both a specific protease and an invasin. Infect Immun (2002) 70(5):2408–13.10.1128/IAI.70.5.2408-2413.2002

57

FrankenCHaaseGBrandtCWeber-HeynemannJMartinSLammlerCet alHorizontal gene transfer and host specificity of beta-haemolytic streptococci: the role of a putative composite transposon containing scpB and lmb. Mol Microbiol (2001) 41(4):925–35.10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02563.x

58

SpellerbergBRozdzinskiEMartinSWeber-HeynemannJSchnitzlerNLuttickenRet alLmb, a protein with similarities to the LraI adhesin family, mediates attachment of Streptococcus agalactiae to human laminin. Infect Immun (1999) 67(2):871–8.

59

ZegelsGVan RaemdonckGACoenEPTjalmaWAVan OstadeXW. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of human cervical-vaginal fluid using colposcopy samples. Proteome Sci (2009) 7:17.10.1186/1477-5956-7-17

60

SoaresGCda SilvaBADos SantosMHda CostaAFDos SantosALMorandiVet alMetallopeptidases produced by group B Streptococcus: influence of proteolytic inhibitors on growth and on interaction with human cell lineages. Int J Mol Med (2008) 22(1):119–25.10.3892/ijmm.22.1.119

61

Bodaszewska-LubasMBrzychczy-WlochMAdamskiPGosiewskiTStrusMHeczkoPB. Adherence of group B streptococci to human rectal and vaginal epithelial cell lines in relation to capsular polysaccharides as well as alpha-like protein genes – pilot study. Pol J Microbiol (2013) 62(1):85–90.

62

PatrasKARoslerBThomanMLDoranKS. Characterization of host immunity during persistent vaginal colonization by group B Streptococcus. Mucosal Immunol (2015) 8(6):1339–48.10.1038/mi.2015.23

63

PatrasKAWangNYFletcherEMCavacoCKJimenezAGargMet alGroup B Streptococcus covR regulation modulates host immune signalling pathways to promote vaginal colonization. Cell Microbiol (2013) 15(7):1154–67.10.1111/cmi.12105

64

CareyAJTanCKMirzaSIrving-RodgersHWebbRILamAet alInfection and cellular defense dynamics in a novel 17beta-estradiol murine model of chronic human group B Streptococcus genital tract colonization reveal a role for hemolysin in persistence and neutrophil accumulation. J Immunol (2014) 192(4):1718–31.10.4049/jimmunol.1202811

65

ShabayekSBauerRMauererSMizaikoffBSpellerbergB. A streptococcal NRAMP homologue is crucial for the survival of Streptococcus agalactiae under low pH conditions. Mol Microbiol (2016) 100(4):589–606.10.1111/mmi.13335

66

RosiniRMargaritI. Biofilm formation by Streptococcus agalactiae: influence of environmental conditions and implicated virulence factors. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2015) 5:6.10.3389/fcimb.2015.00006

67

D’UrzoNMartinelliMPezzicoliADe CesareVPintoVMargaritIet alAcidic pH strongly enhances in vitro biofilm formation by a subset of hypervirulent ST-17 Streptococcus agalactiae strains. Appl Environ Microbiol (2014) 80(7):2176–85.10.1128/AEM.03627-13

68

HoYRLiCMYuCHLinYJWuCMHarnICet alThe enhancement of biofilm formation in Group B streptococcal isolates at vaginal pH. Med Microbiol Immunol (2013) 202(2):105–15.10.1007/s00430-012-0255-0

69

BorgesSSilvaJTeixeiraP. Survival and biofilm formation by Group B streptococci in simulated vaginal fluid at different pHs. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek (2012) 101(3):677–82.10.1007/s10482-011-9666-y

70

RinaudoCDRosiniRGaleottiCLBertiFNecchiFReguzziVet alSpecific involvement of pilus type 2a in biofilm formation in group B Streptococcus. PLoS One (2010) 5(2):e9216.10.1371/journal.pone.0009216

71

BuscettaMPapasergiSFironAPietrocolaGBiondoCMancusoGet alFbsC, a novel fibrinogen-binding protein, promotes Streptococcus agalactiae-host cell interactions. J Biol Chem (2014) 289(30):21003–15.10.1074/jbc.M114.553073

72

RavelJGajerPAbdoZSchneiderGMKoenigSSMcCulleSLet alVaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2011) 108(Suppl 1):4680–7.10.1073/pnas.1002611107

73

Nuriel-OhayonMNeumanHKorenO. Microbial changes during pregnancy, birth, and infancy. Front Microbiol (2016) 7:1031.10.3389/fmicb.2016.01031

74

AagaardKRiehleKMaJSegataNMistrettaTACoarfaCet alA metagenomic approach to characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy. PLoS One (2012) 7(6):e36466.10.1371/journal.pone.0036466

75

KubotaTNojimaMItohS. Vaginal bacterial flora of pregnant women colonized with group B Streptococcus. J Infect Chemother (2002) 8(4):326–30.10.1007/s10156-002-0190-x

76

AltoparlakUKadanaliAKadanaliS. Genital flora in pregnancy and its association with group B streptococcal colonization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2004) 87(3):245–6.10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.08.006

77

RonnqvistPDForsgren-BruskUBGrahn-HakanssonEE. Lactobacilli in the female genital tract in relation to other genital microbes and vaginal pH. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand (2006) 85(6):726–35.10.1080/00016340600578357

78

RickAMAguilarACortesRGordilloRMelgarMSamayoa-ReyesGet alGroup B streptococci colonization in pregnant Guatemalan women: prevalence, risk factors, and vaginal microbiome. Open Forum Infect Dis (2017) 4(1):ofx020.10.1093/ofid/ofx020

79

QiaoJKwokLZhangJGaoPZhengYGuoZet alReduction of Lactobacillus in the milks of cows with subclinical mastitis. Benef Microbes (2015) 6(4):485–90.10.3920/BM2014.0077

80

ZarateGNader-MaciasME. Influence of probiotic vaginal lactobacilli on in vitro adhesion of urogenital pathogens to vaginal epithelial cells. Lett Appl Microbiol (2006) 43(2):174–80.10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01934.x

81

OrtizLRuizFPascualLBarberisL. Effect of two probiotic strains of Lactobacillus on in vitro adherence of Listeria monocytogenes, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Staphylococcus aureus to vaginal epithelial cells. Curr Microbiol (2014) 68(6):679–84.10.1007/s00284-014-0524-9

82

De GregorioPRJuarez TomasMSLeccese TerrafMCNader-MaciasME. In vitro and in vivo effects of beneficial vaginal lactobacilli on pathogens responsible for urogenital tract infections. J Med Microbiol (2014) 63(Pt 5):685–96.10.1099/jmm.0.069401-0

83

De GregorioPRJuarez TomasMSLeccese TerrafMCNader-MaciasME. Preventive effect of Lactobacillus reuteri CRL1324 on Group B Streptococcus vaginal colonization in an experimental mouse model. J Appl Microbiol (2015) 118(4):1034–47.10.1111/jam.12739

84

De GregorioPRJuarez TomasMSNader-MaciasME. Immunomodulation of Lactobacillus reuteri CRL1324 on group B Streptococcus vaginal colonization in a murine experimental model. Am J Reprod Immunol (2016) 75(1):23–35.10.1111/aji.12445

85

BayoMBerlangaMAgutM. Vaginal microbiota in healthy pregnant women and prenatal screening of group B streptococci (GBS). Int Microbiol (2002) 5(2):87–90.10.1007/s10123-002-0064-1

86

RosenGRandisTMDesaiPVSapraKJMaBGajerPet alGroup B Streptococcus and the vaginal microbiota. J Infect Dis (2017) 216(6):744–51.10.1093/infdis/jix395

87

FranzaTDelavenneEDerre-BobillotAJuillardVBoulayMDemeyEet alA partial metabolic pathway enables group B Streptococcus to overcome quinone deficiency in a host bacterial community. Mol Microbiol (2016) 102(1):81–91.10.1111/mmi.13447

88

CookLCLaSarreBFederleMJ. Interspecies communication among commensal and pathogenic streptococci. MBio (2013) 4(4):e00382–413.10.1128/mBio.00382-13

89

MacPheeRAMillerWLGloorGBMcCormickJKHammondJABurtonJPet alInfluence of the vaginal microbiota on toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 production by Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol (2013) 79(6):1835–42.10.1128/AEM.02908-12

90

CarsonHJLapointPGMonifGR. Interrelationships within the bacterial flora of the female genital tract. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol (1997) 5(4):303–9.10.1155/S1064744997000525

91

GhanimNAlchyibOMorrishDTompkinsDJulliardKViscontiEet alMaternal-neonatal outcome with Staphylococcus aureus rectovaginal colonization. J Reprod Med (2011) 56(9–10):421–4.

92

Foster-NyarkoEKwambanaBAderonkeOCeesayFJarjuSBojangAet alAssociations between nasopharyngeal carriage of group B Streptococcus and other respiratory pathogens during early infancy. BMC Microbiol (2016) 16:97.10.1186/s12866-016-0714-7

93

KhosaSAlKhatibZSmitsSH. NSR from Streptococcus agalactiae confers resistance against nisin and is encoded by a conserved nsr operon. Biol Chem (2013) 394(11):1543–9.10.1515/hsz-2013-0167

94

KhosaSLagedrosteMSmitsSH. Protein defense systems against the lantibiotic nisin: function of the immunity protein NisI and the resistance protein NSR. Front Microbiol (2016) 7:504.10.3389/fmicb.2016.00504

95

ChaisilwattanaPMonifGR. In vitro ability of the group B streptococci to inhibit Gram-positive and Gram-variable constituents of the bacterial flora of the female genital tract. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol (1995) 3(3):91–7.10.1155/S1064744995000391

96

BeierDGrossR. Regulation of bacterial virulence by two-component systems. Curr Opin Microbiol (2006) 9(2):143–52.10.1016/j.mib.2006.01.005

97

MascherTHelmannJDUndenG. Stimulus perception in bacterial signal-transducing histidine kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev (2006) 70(4):910–38.10.1128/MMBR.00020-06

98

GlaserPRusniokCBuchrieserCChevalierFFrangeulLMsadekTet alGenome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol Microbiol (2002) 45(6):1499–513.10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03126.x

99

FarallaCMetruccioMMDe ChiaraMMuRPatrasKAMuzziAet alAnalysis of two-component systems in group B Streptococcus shows that RgfAC and the novel FspSR modulate virulence and bacterial fitness. MBio (2014) 5(3):e870–814.10.1128/mBio.00870-14

100

TettelinHMasignaniVCieslewiczMJEisenJAPetersonSWesselsMRet alComplete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2002) 99(19):12391–6.10.1073/pnas.182380799

101

Di PaloBRippaVSantiIBrettoniCMuzziAMetruccioMMet alAdaptive response of group B Streptococcus to high glucose conditions: new insights on the CovRS regulation network. PLoS One (2013) 8(4):e61294.10.1371/journal.pone.0061294

102

LemboAGurneyMABurnsideKBanerjeeAde los ReyesMConnellyJEet alRegulation of CovR expression in group B Streptococcus impacts blood-brain barrier penetration. Mol Microbiol (2010) 77(2):431–43.10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07215.x

103

WhidbeyCHarrellMIBurnsideKNgoLBecraftAKIyerLMet alA hemolytic pigment of group B Streptococcus allows bacterial penetration of human placenta. J Exp Med (2013) 210(6):1265–81.10.1084/jem.20122753

104

JiangSMIshmaelNDunning HotoppJPulitiMTissiLKumarNet alVariation in the group B Streptococcus CsrRS regulon and effects on pathogenicity. J Bacteriol (2008) 190(6):1956–65.10.1128/JB.01677-07

105

Al SafadiRMereghettiLSalloumMLartigueMFVirlogeux-PayantIQuentinRet alTwo-component system RgfA/C activates the fbsB gene encoding major fibrinogen-binding protein in highly virulent CC17 clone group B Streptococcus. PLoS One (2011) 6(2):e14658.10.1371/journal.pone.0014658

106

SpellerbergBRozdzinskiEMartinSWeber-HeynemannJLuttickenR. rgf encodes a novel two-component signal transduction system of Streptococcus agalactiae. Infect Immun (2002) 70(5):2434–40.10.1128/IAI.70.5.2434-2440.2002

107

JoubertLDagieuJBFernandezADerre-BobillotABorezee-DurantEFleurotIet alVisualization of the role of host heme on the virulence of the heme auxotroph Streptococcus agalactiae. Sci Rep (2017) 7:40435.10.1038/srep40435

108

QuachDvan SorgeNMKristianSABryanJDShelverDWDoranKS. The CiaR response regulator in group B Streptococcus promotes intracellular survival and resistance to innate immune defenses. J Bacteriol (2009) 191(7):2023–32.10.1128/JB.01216-08

109

MuRCuttingASDel RosarioYVillarinoNStewartLWestonTAet alIdentification of CiaR regulated genes that promote group B streptococcal virulence and interaction with brain endothelial cells. PLoS One (2016) 11(4):e0153891.10.1371/journal.pone.0153891

110

KlinzingDCIshmaelNDunning HotoppJCTettelinHShieldsKRMadoffLCet alThe two-component response regulator LiaR regulates cell wall stress responses, pili expression and virulence in group B Streptococcus. Microbiology (2013) 159(Pt 7):1521–34.10.1099/mic.0.064444-0

111

PoyartCLamyMCBoumailaCFiedlerFTrieu-CuotP. Regulation of D-alanyl-lipoteichoic acid biosynthesis in Streptococcus agalactiae involves a novel two-component regulatory system. J Bacteriol (2001) 183(21):6324–34.10.1128/JB.183.21.6324-6334.2001

112

RozhdestvenskayaASTotolianAADmitrievAV. Inactivation of DNA-binding response regulator Sak189 abrogates beta-antigen expression and affects virulence of Streptococcus agalactiae. PLoS One (2010) 5(4):e10212.10.1371/journal.pone.0010212

113

KhosaSHoeppnerAGohlkeHSchmittLSmitsSH. Structure of the response regulator NsrR from Streptococcus agalactiae, which is involved in lantibiotic resistance. PLoS One (2016) 11(3):e0149903.10.1371/journal.pone.0149903

114

KenzelSHennekeP. The innate immune system and its relevance to neonatal sepsis. Curr Opin Infect Dis (2006) 19(3):264–70.10.1097/01.qco.0000224821.27482.bd

115

MarquesMBKasperDLPangburnMKWesselsMR. Prevention of C3 deposition by capsular polysaccharide is a virulence mechanism of type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun (1992) 60(10):3986–93.

116

EdwardsMSKasperDLJenningsHJBakerCJNicholson-WellerA. Capsular sialic acid prevents activation of the alternative complement pathway by type III, group B streptococci. J Immunol (1982) 128(3):1278–83.

117

TakahashiSAoyagiYAddersonEEOkuwakiYBohnsackJF. Capsular sialic acid limits C5a production on type III group B streptococci. Infect Immun (1999) 67(4):1866–70.

118

ClearyPPHandleyJSuvorovANPodbielskiAFerrieriP. Similarity between the group B and A streptococcal C5a peptidase genes. Infect Immun (1992) 60(10):4239–44.

119

BohnsackJFMollisonKWBukoAMAshworthJCHillHR. Group B streptococci inactivate complement component C5a by enzymic cleavage at the C-terminus. Biochem J (1991) 273(Pt 3):635–40.10.1042/bj2730635

120

PietrocolaGRindiSRosiniRBuccatoSSpezialePMargaritI. The group B Streptococcus-secreted protein CIP interacts with C4, preventing C3b deposition via the lectin and classical complement pathways. J Immunol (2016) 196(1):385–94.10.4049/jimmunol.1501954

121

AreschougTStalhammar-CarlemalmMKarlssonILindahlG. Streptococcal beta protein has separate binding sites for human factor H and IgA-Fc. J Biol Chem (2002) 277(15):12642–8.10.1074/jbc.M112072200

122

MaruvadaRPrasadaraoNVRubensCE. Acquisition of factor H by a novel surface protein on group B Streptococcus promotes complement degradation. FASEB J (2009) 23(11):3967–77.10.1096/fj.09-138149

123

HennekePMorathSUematsuSWeichertSPfitzenmaierMTakeuchiOet alRole of lipoteichoic acid in the phagocyte response to group B Streptococcus. J Immunol (2005) 174(10):6449–55.10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6449

124

KolterJFeuersteinRSpoeriEGharunKEllingRTrieu-CuotPet alStreptococci engage TLR13 on myeloid cells in a site-specific fashion. J Immunol (2016) 196(6):2733–41.10.4049/jimmunol.1501014

125

MancusoGGambuzzaMMidiriABiondoCPapasergiSAkiraSet alBacterial recognition by TLR7 in the lysosomes of conventional dendritic cells. Nat Immunol (2009) 10(6):587–94.10.1038/ni.1733

126

SignorinoGMohammadiNPataneFBuscettaMVenzaMVenzaIet alRole of toll-like receptor 13 in innate immune recognition of group B streptococci. Infect Immun (2014) 82(12):5013–22.10.1128/IAI.02282-14

127

HennekePTakeuchiOMalleyRLienEIngallsRRFreemanMWet alCellular activation, phagocytosis, and bactericidal activity against group B Streptococcus involve parallel myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent and independent signaling pathways. J Immunol (2002) 169(7):3970–7.10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3970

128

DeshmukhSDKremerBFreudenbergMBauerSGolenbockDTHennekeP. Macrophages recognize streptococci through bacterial single-stranded RNA. EMBO Rep (2011) 12(1):71–6.10.1038/embor.2010.189

129

MancusoGMidiriABeninatiCBiondoCGalboRAkiraSet alDual role of TLR2 and myeloid differentiation factor 88 in a mouse model of invasive group B streptococcal disease. J Immunol (2004) 172(10):6324–9.10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6324

130

LemirePCalzasCSeguraM. The NOD2 receptor does not play a major role in the pathogenesis of Group B Streptococcus in mice. Microb Pathog (2013) 65:41–7.10.1016/j.micpath.2013.09.006

131

LemirePRoyDFittipaldiNOkuraMTakamatsuDBergmanEet alImplication of TLR- but not of NOD2-signaling pathways in dendritic cell activation by group B Streptococcus serotypes III and V. PLoS One (2014) 9(12):e113940.10.1371/journal.pone.0113940

132

WesselsMRRubensCEBenediVJKasperDL. Definition of a bacterial virulence factor: sialylation of the group B streptococcal capsule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1989) 86(22):8983–7.10.1073/pnas.86.22.8983

133

CarlinAFLewisALVarkiANizetV. Group B streptococcal capsular sialic acids interact with siglecs (immunoglobulin-like lectins) on human leukocytes. J Bacteriol (2007) 189(4):1231–7.10.1128/JB.01155-06

134

CarlinAFUchiyamaSChangYCLewisALNizetVVarkiA. Molecular mimicry of host sialylated glycans allows a bacterial pathogen to engage neutrophil Siglec-9 and dampen the innate immune response. Blood (2009) 113(14):3333–6.10.1182/blood-2008-11-187302

135

CarlinAFChangYCAreschougTLindahlGHurtado-ZiolaNKingCCet alGroup B Streptococcus suppression of phagocyte functions by protein-mediated engagement of human Siglec-5. J Exp Med (2009) 206(8):1691–9.10.1084/jem.20090691

136

ChangYCOlsonJBeasleyFCTungCZhangJCrockerPRet alGroup B Streptococcus engages an inhibitory Siglec through sialic acid mimicry to blunt innate immune and inflammatory responses in vivo. PLoS Pathog (2014) 10(1):e1003846.10.1371/journal.ppat.1003846

137

AliSRFongJJCarlinAFBuschTDLindenRAngataTet alSiglec-5 and Siglec-14 are polymorphic paired receptors that modulate neutrophil and amnion signaling responses to group B Streptococcus. J Exp Med (2014) 211(6):1231–42.10.1084/jem.20131853