Abstract

Objective:

Current knowledge on the global burden of infant sepsis is limited to population-level data. We aimed to summarize global case fatality rates (CFRs) of young infants with sepsis, stratified by gross national income (GNI) status and patient-level risk factors.

Methods:

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on CFRs among young infants < 90 days with sepsis. We searched PubMed, Cochrane Central, Embase, and Web of Science for studies published between January 2010 and September 2019. We obtained pooled CFRs estimates using the random effects model. We performed a univariate analysis at patient-level and a meta-regression to study the associations of gestational age, birth weight, onset of sepsis, GNI, age group and culture-proven sepsis with CFRs.

Results:

The search yielded 6314 publications, of which 240 studies (N = 437,796 patients) from 77 countries were included. Of 240 studies, 99 were conducted in high-income countries, 44 in upper-middle-income countries, 82 in lower-middle-income countries, 6 in low-income countries and 9 in multiple income-level countries. Overall pooled CFR was 18% (95% CI, 17–19%). The CFR was highest for low-income countries [25% (95% CI, 7–43%)], followed by lower-middle [25% (95% CI, 7–43%)], upper-middle [21% (95% CI, 18–24%)] and lowest for high-income countries [12% (95% CI, 11–13%)]. Factors associated with high CFRs included prematurity, low birth weight, age less than 28 days, early onset sepsis, hospital acquired infections and sepsis in middle- and low-income countries. Study setting in middle-income countries was an independent predictor of high CFRs. We found a widening disparity in CFRs between countries of different GNI over time.

Conclusion:

Young infant sepsis remains a major global health challenge. The widening disparity in young infant sepsis CFRs between GNI groups underscore the need to channel greater resources especially to the lower income regions.

Systematic Review Registration:

[www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero], identifier [CRD42020164321].

Introduction

Infant sepsis is an important public health challenge with a significant burden of disease. Globally, an estimated 1.3–3.9 million young infants experience sepsis and 400,000–700,000 die from sepsis-related conditions annually (1). In the Sub-Saharan African region alone, young infant sepsis incurs an economic burden of US$10 – $469 billion annually (2).

Sepsis remains a significant cause for death and accounts for up to 15% of all young infant deaths (3). One of the targets in the United Nations Sustainable Developmental Goals 3 (SDG 3) is to reduce neonatal mortality to 12 per 1,000 livebirths and under-5 mortality to 25 per 1,000 livebirths by 2030 (4, 5). The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that an estimated 84% of young infant deaths due to sepsis are preventable (1). Reducing young infant sepsis mortality can contribute to achieving the SDG3 targets by 2030. Pediatric sepsis survivors are at higher risk of poor neurodevelopmental sequelae including neurocognitive deficits and developmental delay (6–8). A better understanding of young infant sepsis can provide valuable insights to inform strategies that span prevention, diagnosis and intervention to mitigate long term mortality and morbidity.

The recent population-based systematic review and meta-analysis on young infant sepsis mortality performed by Fleischmann et al. reviewed data from 1979 to 2019 and reported a population rate of 2824 (95% CI, 1892–4194) neonatal sepsis cases per 100,000 livebirths worldwide with a mortality of 17.6% (95% CI, 10.3–28.6%) (9). Sepsis incidence was reported to be highest in preterm and very low birth weight (VLBW) infants. However, this seminal study only included 14 countries with available population-level data with majority originating from middle-income countries. In addition, there is still a gap in mortality data in low-income countries. This limits the accurate estimate of the global burden of young infant sepsis (10). A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis on young infant sepsis case fatality rates (CFRs) from different income level countries will allow for a timely update to previously published literature on the global burden of young infant sepsis, and provide a more complete understanding on the global burden of young infant sepsis.

We therefore aimed to summarize global CFRs for young infants (<90 days) with sepsis, published from January 2010 to September 2019. We also aimed to describe any differences in young infant sepsis mortality among countries of different gross national income (GNI) status over time.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (11). This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020164321). The protocol is available online (12).

Eligibility Criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies and cross-sectional studies that were published between January 2010 and September 2019. This range was chosen to provide an update on a previously published systematic review on the global burden of neonatal sepsis (10). We excluded studies published before January 2010 in view of the substantial changes in neonatal sepsis diagnosis and management over time.

We identified studies that contained the following specified elements of population, exposure, outcome and study design. We defined the population as infants less than 90 days old, regardless of gestational age. The neonatal period was defined as the first 28 postnatal days in term and post-term newborns, and day of birth through the expected date of delivery plus 27 days for preterm newborns (13). We chose to study infants less than 90 days old to obtain a comprehensive picture of sepsis burden, as serious infections in the young infant population can present past 28 postnatal days (14). If a study included both pediatric and adult population, it was included only if data pertaining to the infant population (<90 days) could be extracted. We defined the exposure as sepsis, which could be of bacterial, viral or fungal origin (15). We included viral infections because young infants can suffer from long term deficits from invasive viral illnesses (16, 17). Due to the lack of a gold standard for diagnosis of young infant sepsis (18), we decided to include all studies with sepsis as defined by study authors. However, we documented if the study defined sepsis according to the International Paediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference (15). We defined our primary outcome as the CFR, which was computed based on the number of deaths divided by the number of infants with sepsis.

We excluded case-control studies, case reports, animal studies, laboratory studies and publications that were not in English. We excluded studies with a primary focus on necrotising enterocolitis, respiratory distress syndrome without a primary sepsis study population, leukemia or other malignancies. We also excluded studies with a sample size of less than 50 to avoid small study effects (19).

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, Cochrane Central, Embase and Web of Science to identify eligible studies. The search was conducted on 17 September 2019 with a search strategy developed in consultation with research librarians experienced in systematic reviews and meta analyses. Strategic keywords used include “neonates,” “infants,” “sepsis,” “neonatal sepsis,” and “mortality.” The detailed search strategy can be found in Supplementary Table 1. We ensured that there were no completed or ongoing trials evaluating global burden of neonatal sepsis by searching PROSPERO, ClinicalTrials.gov, International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), and European Union Clinical Trials Register.

Study Selection Process

Covidence (Australia) was used for the review of articles. Three reviewers (MG, BY, SS) independently conducted the database search and screened the title and abstracts for relevance, and subsequently assessed the full-text of shortlisted articles for eligibility. Any conflict on study eligibility were resolved in discussion with the senior author (S-LC). Reason(s) for exclusion of each article was (were) recorded.

Data Collection Process and Data Items

Four reviewers (MG, BY, SS, and WL) independently carried out the data extraction using a standardized data collection form, and any conflict was resolved by discussion. Study variables included were study characteristics (e.g., study year, study design, geographical origin, sepsis definition, sample size), patient demographics (e.g., age, gender, gestational age, birth weight), patient characteristics (e.g., severity of sepsis, comorbidities, maternal risk factors, microbiological data, sources of infection, onset of sepsis, interventions, duration of hospital stay and blood markers), and outcome (deaths, timeframe to mortality). GNI was determined according to the World Bank Country Classification (20). We contacted the corresponding authors for any missing or unreported data via email. A second reminder email was sent 2 weeks later. When there was no reply 1 month from the first email we considered the team to be un-contactable.

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

We assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs (21), and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for all observational studies (22). Two assessors (SS and WL) independently carried out the assessment, and any conflict was resolved by discussion or with input from a third independent reviewer (MG). An overall rating of high, moderate or low risk was given to each study.

Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages while continuous variables were summarized as means with standard deviations (SD). We generated pooled CFRs and the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using the DerSimonian and Laird method (23). We performed a univariate analysis at patient-level to assess the association between the CFRs and each variable (birth weight, age, gestational age, type of sepsis, source of infection either hospital or community acquired and culture-proven sepsis). We also performed a multivariable meta-regression at study level to assess the association between CFRs among infants less than 90 days and the following variables determined a priori – gestational age, birth weight, onset of sepsis, GNI, age group, and culture-proven sepsis. For each variable in the multivariable meta-regression analysis, only studies that exclusively looked at high risk groups [preterm infants, infants with low birth weight (LBW), early onset sepsis, countries with middle- and low-income, age <28 days and culture-proven sepsis] were selected. These studies were compared to reference groups of lower risk, and included studies that did not exclusively contain the high risk groups. For example, when studying the effect of birth weight, we compared studies that only included LBW and VLBW infants, as compared to studies that included infants of normal birth weight. For GNI status, we took high-income groups as the reference group. For study design, we took RCTs as the reference group.

All statistical analysis was done using Stata (v16.1, College Station, TX, United States). We used I2 statistics to quantify heterogeneity between studies. We performed two sensitivity analyses in which we included: (1) only studies with culture-proven sepsis; and (2) only studies with low risk of bias, evaluating CFRs and temporal trends limiting to these studies.

Results

Study Selection

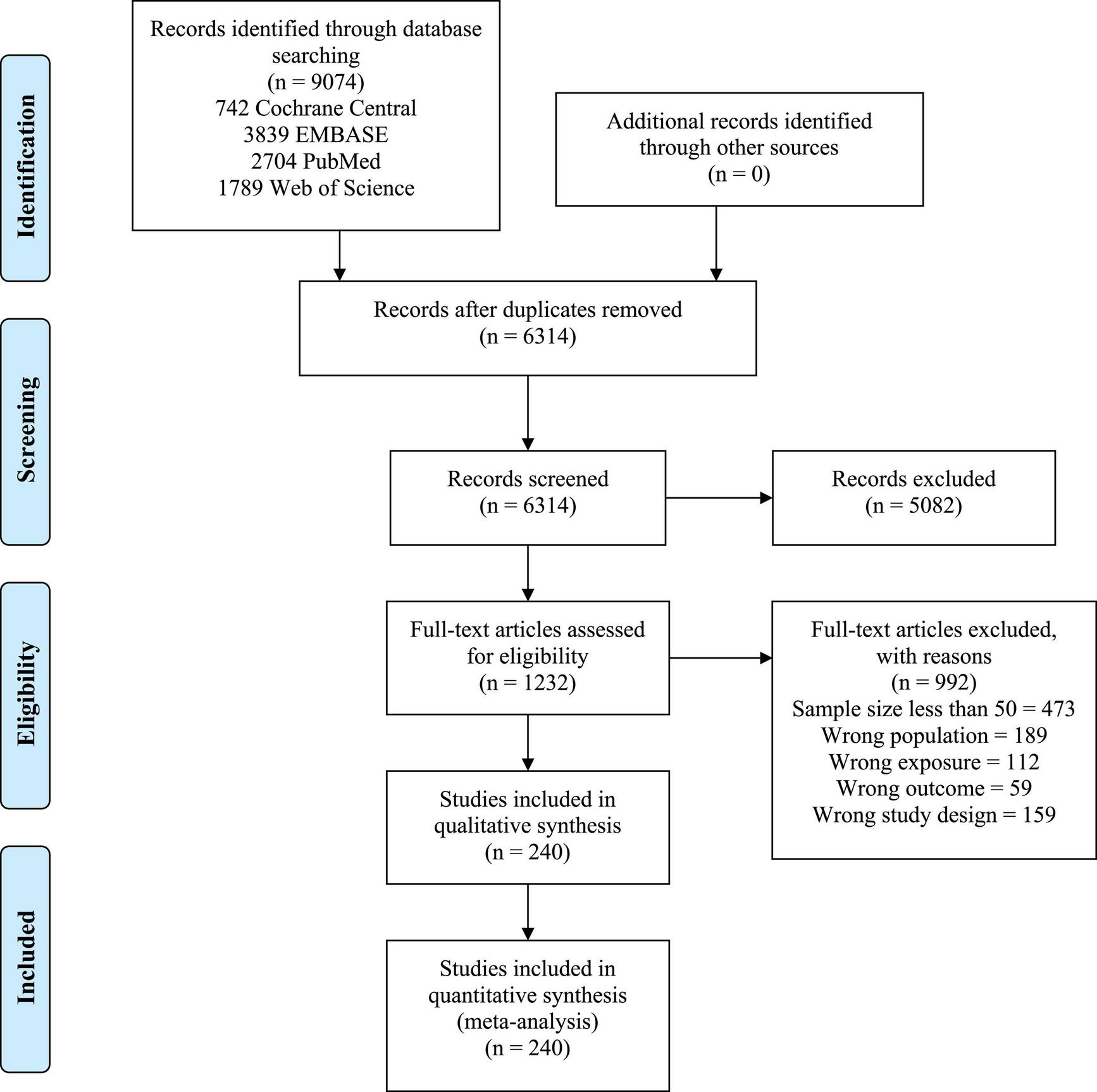

Among 6314 articles screened, 240 studies (with a total of 437,796 patients) met the inclusion criteria and were included for analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

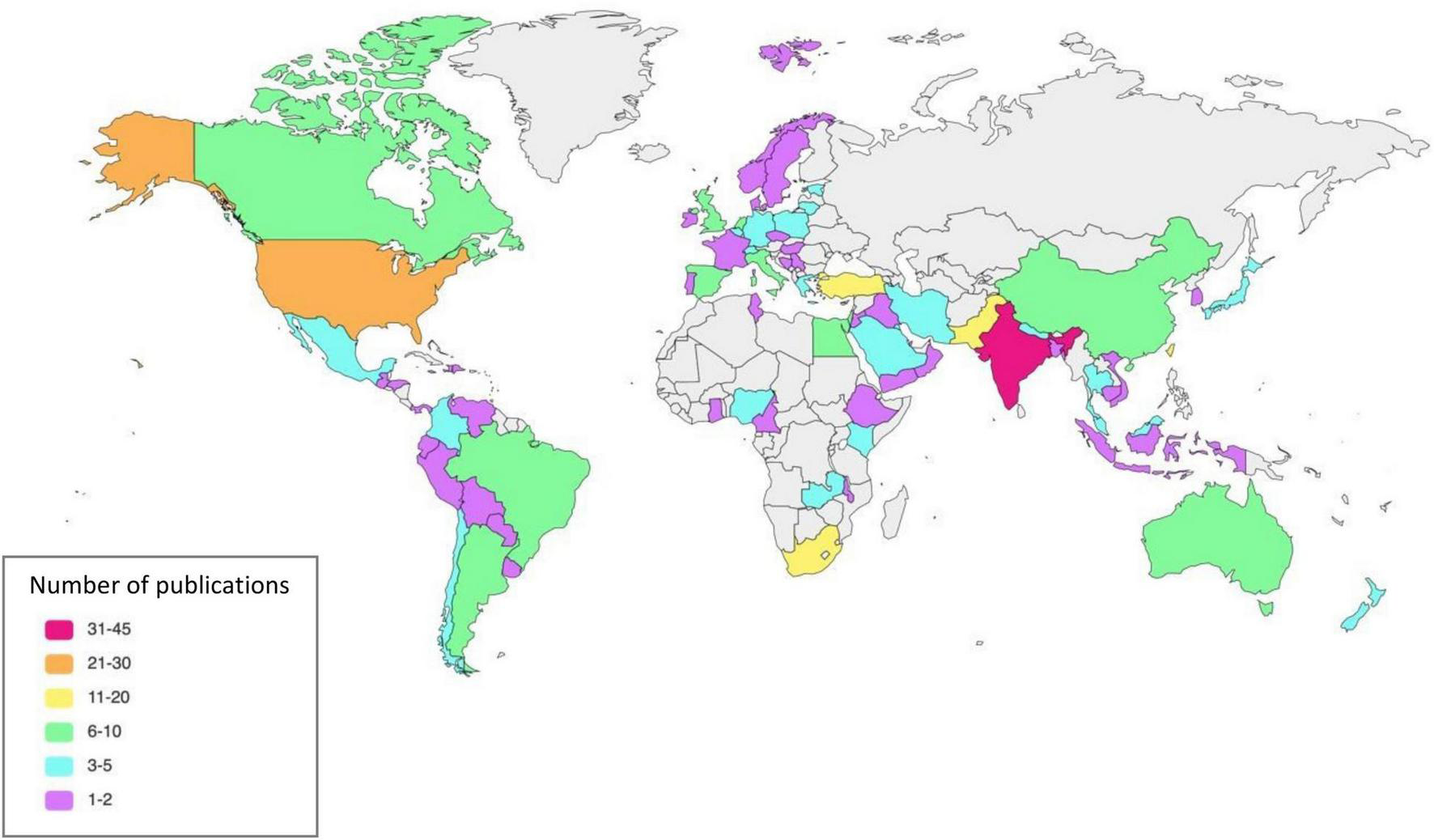

Characteristics of the included studies and study population are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and Supplementary Table 2. The studies originate from 77 countries and six continents (Figure 2).

TABLE 1

| High-income countries (n = 99) | Upper-middle-income countries (n = 44) | Lower-middle-income countries (n = 82) | Low-income countries (n = 6) | Multiple income level countries (n = 9) | All studies (n = 240) | |

| Study design | ||||||

| Cross sectional study, n (%) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 11 (5) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 22 (9) |

| Randomized controlled trial, n (%) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 9 (4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 15 (6) |

| Prospective cohort study, n (%) | 31 (13) | 14 (6) | 34 (14) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2) | 85 (35) |

| Retrospective cohort study, n (%) | 63 (26) | 23 (10) | 27 (11) | 3 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 117 (49) |

| Continents* | ||||||

| Africa, n (%) | 3 (1) | 8 (3) | 20 (8) | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 38 (16) |

| Asia, n (%) | 33 (14) | 23 (10) | 70 (29) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (3) | 133 (55) |

| Australia, n (%) | 4 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1) | 7 (3) |

| Europe, n (%) | 34 (14) | 13 (5) | 2 (0.8) | 0 | 4 (2) | 53 (22) |

| North America, n (%) | 28 (12) | 4 (2) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 6 (3) | 40 (17) |

| South America, n (%) | 0 | 7 (3) | 0 | 0 | 6 (3) | 13 (5) |

| Studies that include culture-proven sepsis,n (%) | 91 (38) | 40 (17) | 74 (31) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 215 (90) |

Characteristics of studies.

*Some countries are transcontinental and hence total n for countries does not add up to 240.

TABLE 2

| High-income countries (n = 99) | Upper-middle-income countries (n = 44) | Lower-middle-income countries (n = 82) | Low-income countries (n = 6) | Multiple income level countries (n = 9) | All studies (n = 240) | |

| Age of patients | ||||||

| Age of patients, mean ± SD, days | 27.9 ± 20.4 | 16.2 ± 15.6 | 9.8 ± 10.7 | 1.7 | – | 13.2 ± 15.5 |

| Studies that exclusively studied neonates (<28 days), n (%) | 55 (23) | 31 (13) | 70 (29) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 164 (68) |

| Birth weight of patients | ||||||

| Birth weight of patients, mean (SD), g | 978 ± 356 | 1397 ± 522 | 2328 ± 666 | – | – | 1481 ± 517 |

| Studies that exclusively studied low birth weight infants (<2500 g), n (%) | 17 (7) | 4 (2) | 3 (1) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 26 (11) |

| Gestational age of patients | ||||||

| Gestational age, mean (SD), weeks | 28.0 ± 3.0 | 29.8 ± 3.1 | 35.7 ± 2.9 | – | 37.0 ± 4.0 | 30.4 ± 3.0 |

| Studies that exclusively studied preterm infants (<37 weeks), n (%) | 13 (5) | 6 (3) | 5 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (10) |

| Types of sepsis | ||||||

| Studies that exclusively studied early onset sepsis (based on author’s definition), n (%) | 15 (6) | 3 (1) | 7 (3) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 26 (11) |

| Predominant Causative Organisms | ||||||

| Gram-positive bacteria, n (%) | 62 (26) | 17 (7) | 15 (6) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (3) | 102 (43) |

| Gram-negative bacteria, n (%) | 20 (8) | 18 (8) | 48 (20) | 4 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 91 (38) |

| Viral, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Fungal, n (%) | 6 (3) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 12 (5) |

Characteristics of study population.

FIGURE 2

Publication by countries.

The greatest number of studies were conducted in Asia with 133 studies (63042 patients), followed by Europe with 53 studies (23639 patients), North America (40 studies, 253786 patients), Africa (38 studies, 39554 patients), South America (13 studies, 160386 patients) and Australia (7 studies, 3270 patients).

Of the 240 studies, 99 (24–122) (41%) were conducted in high-income countries, 44 (123–166) (18%) in upper-middle-income countries, 82 (167–248) (34%) in lower-middle-income countries, and 6 (249–254) (3%) in low-income countries. Nine (255–263) (4%) studies were conducted in countries with multiple income levels.

Among all studies, 215/240 studies (90%) included culture-proven sepsis in their study population while 175/240 (73%) used a combination of clinical and laboratory criteria. 164/240 (68%) studies exclusively studied neonates (<28 days), 24/116 (21%) studies exclusively studied preterm infants, 26/125 (21%) exclusively studied LBW infants and 26/160 (16%) exclusively studied early onset sepsis. Out of 240 studies, 55 (23%) studies reported CFRs stratified by preterm versus term, 28 (12%) studies reported CFRs in community versus hospital acquired sepsis, 107 (45%) studies reported CFRs defined by early or late onset sepsis, and 56 (23%) studies reported birth weight related specific CFRs.

Patient Characteristics

Overall mean age of the study population was 13.2 ± 15.5 days. Mean birth weight and gestational age of the study population was 1480 ± 516 grams and 30.4 ± 3.0 weeks, respectively.

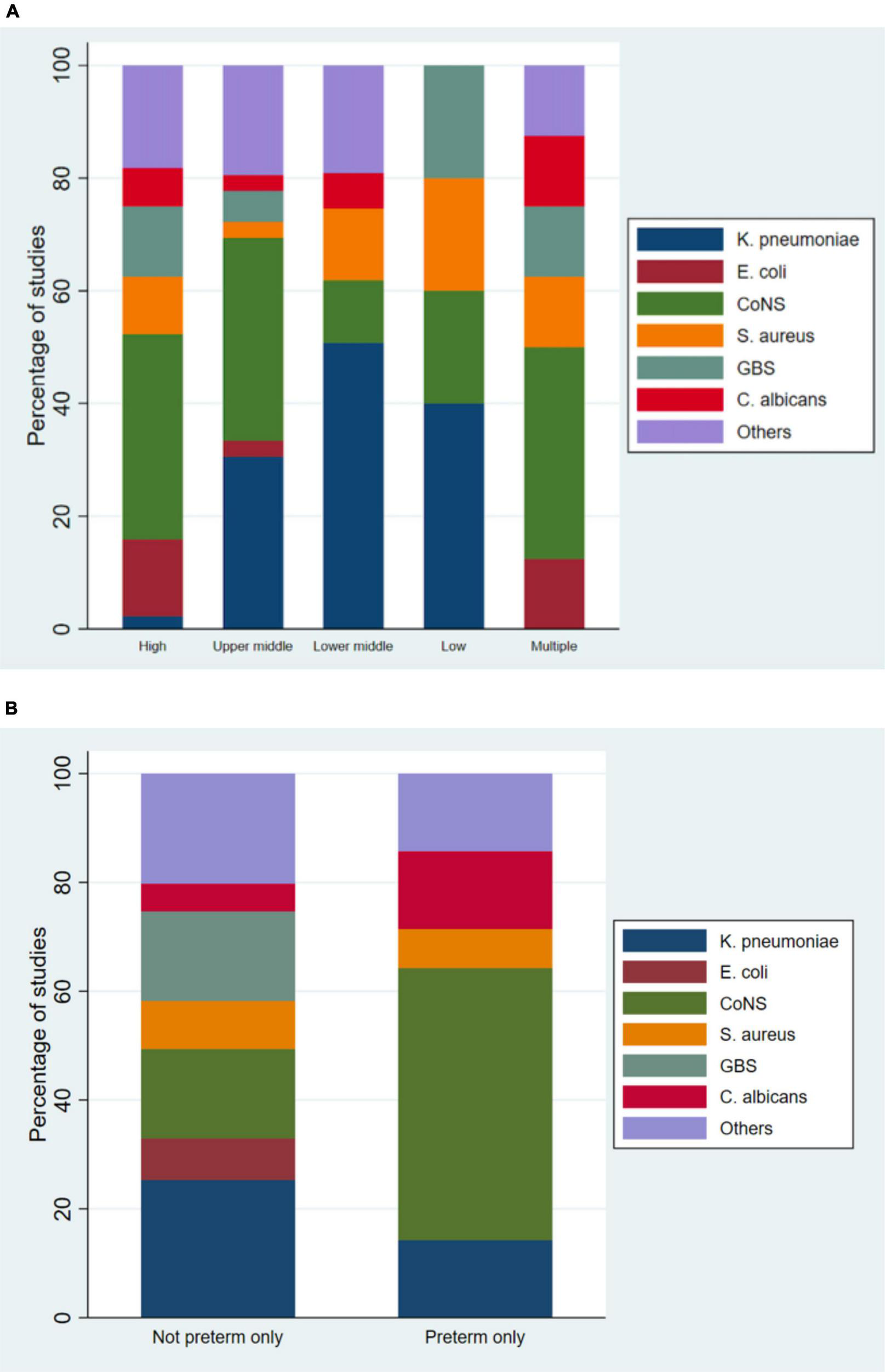

One hundred and two studies (43%) reported gram positive organisms as the predominant organisms causing sepsis. Among the studies conducted in high-income countries, 62 of 99 studies (63%) reported gram positive organisms as the predominant causative organisms, while gram negative organisms were the predominant causative organisms in studies conducted in middle- or low-income countries – 18/44 (41%) in upper-middle-income countries, 48/82 (59%) in lower-middle-income countries, 4/6 (67%) in low-income countries.

Amongst the 200 studies that reported pathogens causing infant sepsis, the most common organisms reported were Coagulase-negative staphylococci (28%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (24), Staphylococcus aureus (10%), Group B Streptococcus (8%), Escherichia coli (7%), and Candida albicans (6%). Among 24 studies that exclusively studied preterm infants, 21 studies reported the most common organism, in which the most common organism was coagulase-negative staphylococci, reported by 10/21 (48%) studies (Figure 3). Among 26 studies that exclusively studied LBW infants, 24 studies reported the most common organism, in which the most common organism was coagulase-negative staphylococci, reported by 13/24 (54%) studies.

FIGURE 3

Causative organisms categorized by gross national income (A) and gestational age (B).

Outcomes

Overall, the pooled CFR was 18% (95% CI, 17–19%). The CFR was lowest for high-income countries [12% (95% CI, 11–13%)], as compared to upper-middle-income countries [21% (95% CI, 18–24%)] and lower-middle-income countries [24% (95% CI, 21–26%)]. Low-income countries had the highest CFR [25% (95% CI, 7–43%)]. Pooled CFR for continents was highest for Africa 24% (95% CI, 21–27%) and lowest in Australia 14% (95% CI, 10–18%) (Table 3). For study designs, cross sectional studies had a higher CFR of 22% (95% CI, 16–28%), while RCTs had a CFR of 13% (95% CI, 10–17%). Studies with a low risk of bias had a pooled CFR of 17% (95% CI, 16–18%).

TABLE 3

| Pooled CFRs (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Gross National Income | |

| Low-income countries (6)† | 25% (7–43%) |

| Lower-middle-income countries (82) | 24% (21–26%) |

| Upper-middle-income countries (44) | 21% (18–24%) |

| High-income countries (99) | 12% (11–13%) |

| Study designs | |

| Cross-sectional studies (22) | 22% (16–28%) |

| Prospective studies (85) | 20% (18–22%) |

| Retrospective studies (117) | 17% (16–18%) |

| Randomized controlled trials (15) | 13% (10–17%) |

| Study continent | |

| Africa (38) | 24% (21–27%) |

| South America (13) | 20% (17–22%) |

| Asia (133) | 19% (18–21%) |

| North America (40) | 18% (15–20%) |

| Europe (53) | 16% (14–17%) |

| Australia (7) | 14% (10–18%) |

| Studies with low risk of bias (184) | 17% (16–18%) |

| Overall pooled CFR | 18% (17–19%) |

Pooled Case Fatality Rates based on study characteristics.

†(N) refers to the number of studies that studied the variable and reported mortality.

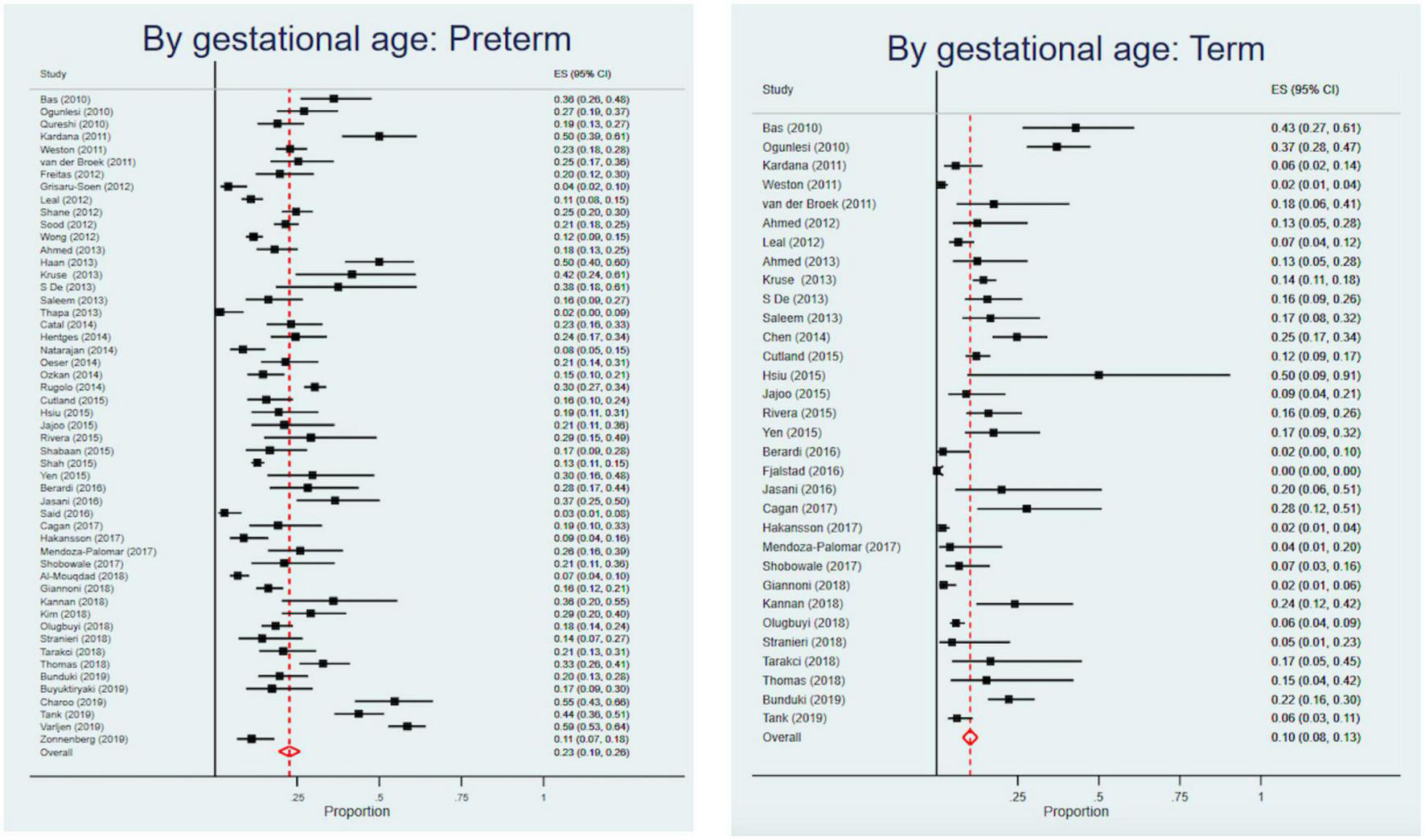

Among studies that reported CFRs by birth weight, the highest CFR was for VLBW infants [24% (95% CI, 21–26%] in comparison to LBW infants [23% (95% CI, 21–26%) and normal birth weight infants [15% (95% CI, 10–21%)]. Studies exclusively on neonates had a higher CFR of 18% (95% CI, 17–19%) compared to studies that included older infants [15% (95% CI, 14–17%)]. Studies on preterm infants had a CFR of 23% (95% CI, 19–26%), more than double compared to term infants with a CFR of 10% (95% CI, 8–13%) (Figure 4). Infants with early onset sepsis (<72 h of life) had a CFR of 20% (95% CI, 17–24%), while infants with early and late onset sepsis had a CFR of 16% (95% CI, 14–18%). Infants with hospital-acquired infections had a CFR of 23% (95% CI, 17–29%), higher than those with community-acquired infections [14% (95% CI, 9–19%)]. Infants with culture- proven sepsis had a CFR of 20% (95% CI, 19–22%) (Table 4).

FIGURE 4

Forest plots of preterm and term Case Fatality Rates.

TABLE 4

| Pooled CFRs (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Birth weight | |

| <1500 g (45)‡ | 24% (21–26%) |

| <2500 g (51) | 23% (21–26%) |

| ≥2500 g (16) | 15% (10–21%) |

| Age | |

| Studies that exclusively studied neonates < 28 days (164) | 18% (17–19%) |

| Gestational age | |

| Preterm (52) | 23% (19–26%) |

| Term (32) | 10% (8–13%) |

| Type of sepsis | |

| Early onset (<72 h) (44) | 20% (17–24%) |

| All (both) (83) | 16% (14–18%) |

| Source of infection | |

| Hospital acquired (22) | 23% (17–29%) |

| Community acquired (14) | 14% (9–19%) |

| Culture-proven sepsis (178) | 20% (19–22%) |

| Overall pooled case fatality rate (240) | 18% (17–19%) |

Pooled Case Fatality Rates for study population characteristics.

‡(N) refers to the number of studies that studied the variable and reported mortality.

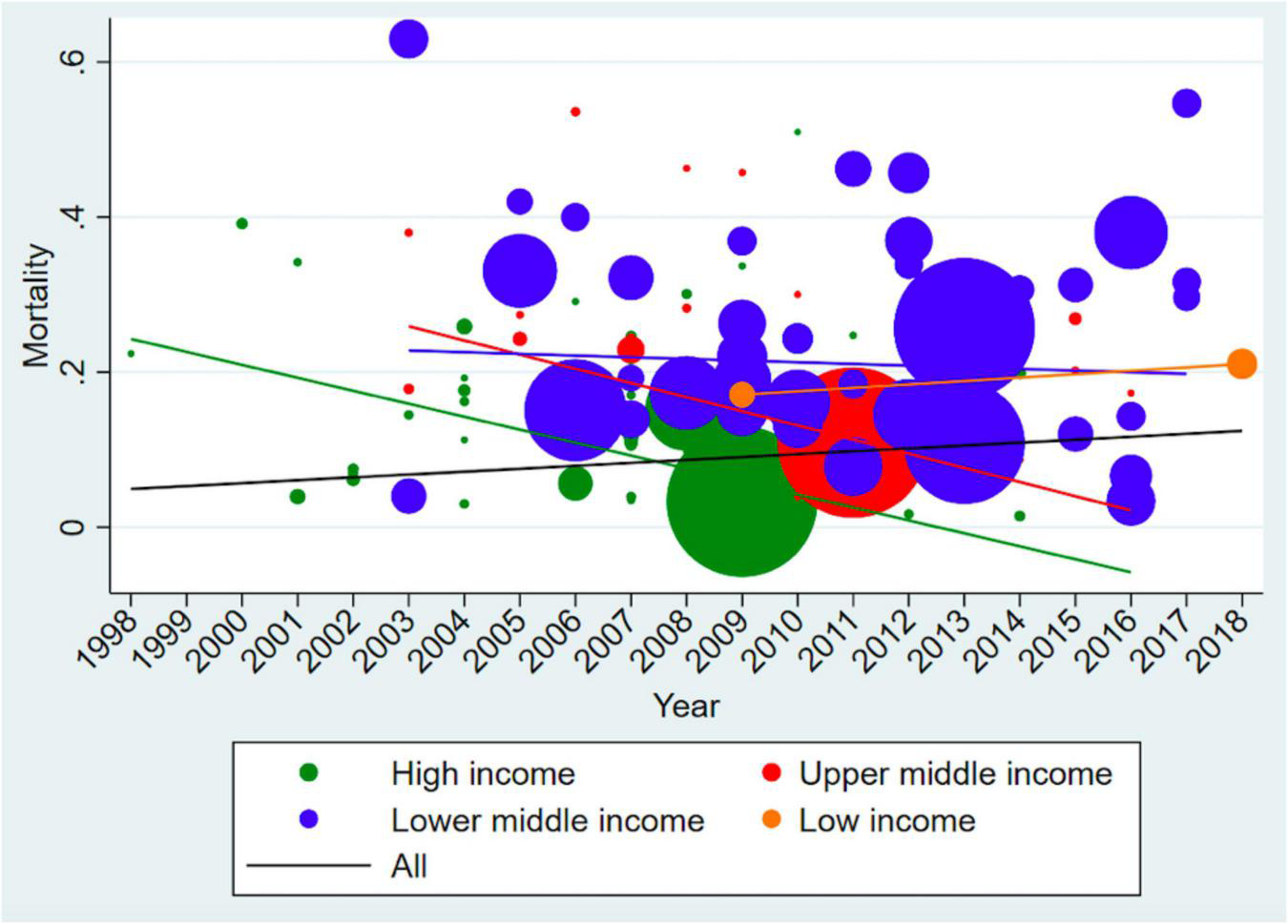

There was an overall increasing trend in young infant sepsis CFRs over time (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 1). When annual pooled CFRs were stratified according to GNI status, there was a widening of the disparity between GNI and young infant CFRs, with time. This is consistent with the sensitivity analysis including only studies with low risk of bias (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Time trend analysis of Case Fatality Rates (including only low risk of bias studies). The size of the bubble is proportionate to the number of infants in the study, while the line represents the trends of case fatality rates over time. There is an increasing trend for low-income countries and decreasing trend for middle- and high-income countries overtime. The overall trend for young infant sepsis case fatality rates is increasing.

Meta Regression

Nine (4%) studies that were conducted in countries with multiple income levels were excluded from the analysis. Independent predictors of higher CFRs include upper-middle- and lower-middle-income countries [regression coefficient 0.12 (95% CI, 0.04–0.21); p = 0.003 and 0.14 (95% CI, 0.06–0.22); p = 0.001 respectively] (Table 5).

TABLE 5

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Gestational age§ | ||||

| Term | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Preterm | 0.04 (–0.01, 0.09) | 0.11 | 0.11 (–0.02, 0.23) | 0.09 |

| Birth weight** | ||||

| Normal birth weight | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Low birth weight | 0.08 (0.03, 0.12) | 0.001 | –0.02 (–0.16, 0.13) | 0.83 |

| Type of sepsis†† | ||||

| Late onset sepsis | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Early onset sepsis | 0.0005 (–0.07, 0.07) | 0.99 | 0.05 (–0.05, 0.15) | 0.35 |

| Both early and late onset sepsis | 0.05 (–0.006, 0.10) | 0.08 | 0.04 (–0.04, 0.12) | 0.33 |

| Gross national income | ||||

| High-income | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Upper-middle-income | 0.05 (0.03, 0.07) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.04, 0.21) | 0.003 |

| Lower-middle-income | 0.15 (0.11, 0.19) | <0.001 | 0.14 (0.06, 0.22) | 0.001 |

| Low-income | 0.20 (0.08, 0.31) | 0.001 | 0.04 (–0.13, 0.21) | 0.65 |

| Age < 28 days | –0.06 (–0.08, –0.05) | <0.001 | –0.06 (–0.15, 0.03) | 0.17 |

| Culture-proven sepsis | 0.07 (0.04, 0.09) | <0.001 | 0.08 (–0.04, 0.20) | 0.20 |

Meta regression predicting Case Fatality Rates among infants less than 90 days.

§Term is defined as 37 weeks or more, preterm is defined as less than 37 weeks.

**Normal birthweight is defined as ≥ 2500 g, low birthweight is defined as < 2500 g.

††Early onset sepsis is defined as sepsis onset < 72 h.

Heterogeneity among studies were high with I2 ranging 91–99%. This was persistent even with our sensitivity analyses that included only studies with culture-proven sepsis, and only studies with low risk of bias.

Reporting Biases

Five (33%) of the 15 RCTs and 179 (80%) of the 225 observational studies were assigned low risk of bias respectively (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). RCTs that were assigned moderate or high risk of bias were mainly due to the lack of blinding of participants or outcome assessors. Observational studies that were assigned moderate or high risk of bias were mainly due to either undefined or poorly defined clinical sepsis criteria, lack of a sufficient duration of follow up for assessing mortality or lack of adequate follow up rate.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we provide an update to previously published literature on the global burden of young infant sepsis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest systematic review and meta-analysis of young infant sepsis CFRs, comprising 240 studies from 77 countries over six continents, which are not limited to population-based studies. Of the 240 studies included, 132 (55%) studies from 36 countries were conducted in middle and low-income countries, compared to 22 studies from 11 countries that were included in the prior systematic review by Fleischmann et al. (9). Our data bridge the knowledge gap on young infant sepsis particularly from low- and middle-income countries. This is also the first study that reflects global young infant sepsis CFRs over time stratified by GNI – with a decreasing trend in high-income countries but a worrying increasing trend in low-income countries, providing new insights into global young infant sepsis CFR trajectories.

We found a widening disparity in young infant sepsis outcomes between countries of different GNI. Our study revealed that Africa with a majority of low-income countries bore the highest burden of young infant sepsis with a CFR of 24% compared to Europe and Australia with a CFR burden of 16 and 14% respectively. The WHO Global Report on the Epidemiology and Burden of Sepsis 2020 showed similar results where low- and middle-income countries shoulder a higher incidence and mortality burden of young infant sepsis, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia (1). Fleischmann-Struzek et al. also reported that young infant sepsis mortality rates were two times higher in middle-income countries than high-income countries (10). Young infants from lower middle- and low-income countries often present with comorbidities such as malnutrition and dehydration that can increase the risk of severe sepsis and death (264). Furthermore, unrecognized or untreated perinatal infections increase the risk of young infant sepsis (264). Limited access to high-quality healthcare results in delays to diagnosis and treatment of young infant sepsis (265–267). This includes the lack of adequately equipped and staffed healthcare institutions (19), and insufficient subsidized healthcare services for the poor (268).

There is currently limited epidemiological data on infant sepsis, especially in low-middle- and low-income countries (9, 10). The WHO has repeatedly called for a global effort to generate sepsis epidemiological data, especially in low-income countries (1). This requires early and accurate diagnosis of sepsis, as well as an improved coordination between like-minded groups doing research in these countries. Systems-based changes to strengthen each country’s health system should target the achievement of universal health coverage (269). This will ensure the availability of essential health-care services that are safe, effective and affordable to all in low-income countries (270). With a global commitment to robust infant sepsis surveillance, universal health coverage and greater resources channeled to low-income countries, we can work toward reducing young infant CFRs globally, especially in low-income countries.

Our overall CFR of 18% for young infants with sepsis was consistent with prior reports (11–29%) (9, 10). Of potential concern is that our time trend analysis of young infant sepsis CFRs showed an overall increasing trend over time from 1998 to 2018. In contrast, the Global Burden of Disease study 2019 showed a decreasing trend of –11.5% (95% CI, –23.6% to –4.3%) change in deaths due to neonatal sepsis from 2009 to 2019 (271). The limited number of studies from middle- and low-income countries represented in the earlier time period in our meta-analysis could have resulted in falsely low global young infant CFRs. Notably, all studies with a reference year prior to 2002 (Figure 5) were conducted in high-income countries. In addition, a global shift in focus to better understand young infant sepsis epidemiology in recent years could have resulted in an increased reporting of young infant sepsis mortality in lower-middle- and low-income countries (1, 272), contributing to the increasing trend of young infant CFRs in the lower-middle- and low-income countries, and also the overall trend.

Our study highlighted several factors associated with higher CFRs in young infant sepsis, namely prematurity, LBW, age less than 28 days, early onset sepsis and hospital acquired infections and sepsis in middle- and low-income countries. Previous literature similarly demonstrated prematurity and LBW to be major risk factors of young infant sepsis (273). In addition, neonates aged less than 28 days reported higher CFRs. This could be attributed to a relatively immature immune system resulting in neonates being more susceptible to infections (274). Studies have also shown that early onset sepsis disproportionately affects preterm infants who are already at a higher risk for mortality, and can result in fulminant, multisystemic infections (275). Infants who develop hospital acquired infections often have lower birth weights, lower gestational age and greater comorbidities compared to community acquired infections (37, 276). This translates to lower functional reserves and decreased immunity defenses, resulting in infants who develop hospital acquired infections having more severe infections and poorer outcomes.

Our study focused on the association between geographical gross income status and CFRs. Nonetheless, we recognize the impact of social determinants of health on young infant sepsis CFRs. A previous study reported that patients of lower socioeconomic status and those who paid out-of-pocket (as compared to privately insured patients) experienced a greater risk of young infant sepsis mortality (39). In another study, it was reported that young infants born to mothers with lower education experienced higher young infant sepsis death rate (101). Young infants of non-White ethnicity have been reported to have higher odds ratio of young infant sepsis mortality as compared to infants of White ethnicity (109). Currently, few studies detail the impact of specific social determinants of health on young infant sepsis incidence and CFRs. Further research in this area may be helpful in informing strategies regarding resource distribution and utilization.

Our attempt to provide a global scope on young infant sepsis with an inclusion criteria that accepted a wide range of study populations and sepsis definition may have led to considerable heterogeneity (1). This is likely to be contributed by the differing underlying parameters used in each study – such as differences in study design, study period, geographical region as well as the predominant organisms. Previous studies have shown that meta-analyses addressing broad review questions may result in highly heterogenous studies (277). We generated pooled CFRs using the random effects model which accounts for total study variation including between-study variations. Nevertheless, we recognize wide variation between study populations, social determinants of health, resource availability and outcome measures used, so much so that the high heterogeneity limited precise answers on sepsis mortality among young infants (277).

Limitations

Firstly, due to the lack of a gold standard for diagnosis of young infant sepsis, we accepted a wide range of sepsis definitions but categorized them into clinical, laboratory or culture-proven (18). Future studies utilizing a standardized sepsis definition that can be widely applied to all regions will facilitate comparative studies. Secondly, there was considerable heterogeneity in our meta-analysis, ranging from 91 to 99%. A sensitivity analysis including only studies with low risk of bias revealed similar results. We attributed this to variability in study populations, availability and delivery of health services, and outcome measures used. Thirdly, we excluded non-English studies which may have resulted in us missing useful data. We also excluded any studies with sample size less than 50 to reduce small study effects (19), which may have resulted in relevant studies being excluded. Finally, a lack of studies from the low- and middle-income countries in the earlier time period resulted in limited interpretation of the overall trend of young infant sepsis.

Conclusion

Our review showed an overall global burden of young infant sepsis CFR of 18%, with an increasing disparity between low- and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries over time. Factors associated with higher CFRs included prematurity, LBW, age less than 28 days, early onset sepsis, hospital acquired infections and sepsis in middle- and low-income countries, of which sepsis in middle-income countries was an independent predictor of higher CFRs. The findings from our study serve as a global call to action to achieve further reductions in young infant sepsis mortality. Future initiatives should focus on improving the delivery of care to infants at higher risk of sepsis, especially in the low- and middle-income countries.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MG, WL, BY, and S-LC coordinated the study. MG, BY, JP, BT, and S-LC developed the search strategy and registered the protocol. MG, WL, BY, SS, and BT reviewed the studies and extracted data from the studies. WL and SS conducted risk of bias assessments. RG conducted the statistical analyses. MG, WL, RG, CH, JL, and S-LC performed the data interpretation. MG and WL wrote the original draft of the manuscript with revision from BY and SS. BY, SS, RG, JP, BT, CH, JL, and S-LC helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Toh Kim Kee, senior librarian from National University of Singapore, for tirelessly helping us with the search strategy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2022.890767/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

WHO.Global Report on the Epidemiology and Burden of Sepsis: Current Evidence, Identifying Gaps and Future Directions.Geneva: WHO (2020).

2.

RanjevaSLWarfBCSchiffSJ. Economic burden of neonatal sepsis in sub-Saharan Africa.BMJ Glob Health. (2018) 3:e000347. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000347

3.

UN-IGME, UNICEF.Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2019, Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation.New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund (2019).

4.

WHO.Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). (2020). Available online at:https://www.who.int/health-topics/sustainable-development-goals#tab=tab_2 (accessed October 18, 2020).

5.

HugLAlexanderMYouDAlkemaL.National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis.Lancet Glob Health. (2019) 7:e710–20. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30163-9

6.

SavioliKRouseCSusiAGormanGHisle-GormanE.Suspected or known neonatal sepsis and neurodevelopmental delay by 5 years.J Perinatol. (2018) 38:1573–80. 10.1038/s41372-018-0217-5

7.

CaiSThompsonDKAndersonPJYangJY-M.Short-and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of very preterm infants with neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Children. (2019) 6:131.

8.

AlshaikhBYusufKSauveR.Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very low birth weight infants with neonatal sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis.J Perinatol. (2013) 33:558–64. 10.1038/jp.2012.167

9.

FleischmannCReichertFCassiniAHornerRHarderTMarkwartRet alGlobal incidence and mortality of neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106:745–52. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320217

10.

Fleischmann-StruzekCGoldfarbDMSchlattmannPSchlapbachLJReinhartKKissoonN.The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review.Lancet Respir Med. (2018) 6:223–30. 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30063-8

11.

PageMJMcKenzieJEBossuytPMBoutronIHoffmannTCMulrowCDet alThe PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews.BMJ. (2021) 372:n71.

12.

PekJHGanMYYapBJSeethorSTTGreenbergRGHornikCPVet alContemporary trends in global mortality of sepsis among young infants less than 90 days old: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis.BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e038815. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038815

13.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER).General Clinical Pharmacology Considerations for Neonatal Studies for Drugs and Biological Products Guidance for Industry. (2019). Available online at:https://www.fda.gov/media/129532/download (accessed May 2021).

14.

BizzarroMJShabanovaVBaltimoreRSDembryL-MEhrenkranzRAGallagherPG.Neonatal sepsis 2004-2013: the rise and fall of coagulase-negative staphylococci.J Pediatr. (2015) 166:1193–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.02.009

15.

GoldsteinBGiroirBRandolphA.International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics.Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2005) 6:2–8.

16.

ShaneALSánchezPJStollBJ.Neonatal sepsis.Lancet. (2017) 390:1770–80.

17.

SatarMOzlüF.Neonatal sepsis: a continuing disease burden.Turk J Pediatr. (2012) 54:449–57.

18.

CoopersmithCMDe BackerDDeutschmanCSFerrerRLatIMachadoFRet alSurviving sepsis campaign: research priorities for sepsis and septic shock.Intensive Care Med. (2018) 44:1400–26.

19.

TanBWongJJSultanaRKohJJitMMokYHet alGlobal case-fatality rates in pediatric severe sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis.JAMA Pediatr. (2019) 173:352–62. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4839

20.

The World Bank.World Bank Country and Lending Groups. (2020). Available online at:https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed October 18, 2020).

21.

SterneJASavovićJPageMJElbersRGBlencoweNSBoutronIet alRoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials.BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

22.

GA WellsBSO’ConnellDPetersonJWelchVLososMTugwellP.The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. (2021) Available online at:http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed September 12, 2021).

23.

SterneJBradburnMEggerM.Meta-Analysis in Stata: Systematic Reviews in Health Care.London: BMJ Publishing Group (2008).

24.

ZonnenbergIAvan Dijk-LokkartEMvan den DungenFAMVermeulenRJvan WeissenbruchMM.Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age in preterm infants with late-onset sepsis.Eur J Pediatr. (2019) 178:673–80. 10.1007/s00431-019-03339-2

25.

SinghTBarnesEHIsaacsDAustralian Study Group for Neonatal Infections.Early-onset neonatal infections in Australia and New Zealand, 2002-2012.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2019) 104:F248–52. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314671

26.

PruittCMNeumanMIShahSSShabanovaVWollCWangMEet alFactors associated with adverse outcomes among febrile young infants with invasive bacterial infections.J Pediatr. (2019) 204:177–82.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.066

27.

HamdyRFDonaDJacobsMBGerberJS.Risk Factors for complications in children with staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.J Pediatr. (2019) 208:214–20.e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.002

28.

GlikmanDCurielNGlatman-FreedmanAMeggedOYoungsterIMaromRet alNationwide epidemiology of early-onset sepsis in Israel 2010-2015, time to re-evaluate empiric treatment.Acta Paediatr. (2019) 108:2192–8. 10.1111/apa.14889

29.

BerardiASpadaCReggianiMLBCretiRBaroniLCaprettiMGet alGroup B Streptococcus early-onset disease and observation of well-appearing newborns.PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0212784. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212784

30.

Al-MataryAHeenaHAlSarheedASOudaWAlShahraniDAWaniTAet alCharacteristics of neonatal sepsis at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia.J Infect Public Health. (2019) 12:666–72. 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.03.007

31.

Al LuhidanLMadaniAAlbanyanEAAl SaifSNasefMAlJohaniSet alNeonatal group B streptococcal infection in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia: a 13-year experience.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2019) 38:731–4. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002269

32.

AbdellatifMAl-KhaboriMRahmanAUKhanAAAl-FarsiAAliK.Outcome of late-onset neonatal sepsis at a tertiary hospital in Oman.Oman Med J. (2019) 34:302–7. 10.5001/omj.2019.60

33.

TingJYRobertsASynnesACanningRBodaniJMonterossaLet alInvasive fungal infections in neonates in Canada: epidemiology and outcomes.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2018) 37:1154–9. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001968

34.

KimJKChangYSSungSAhnSYParkWS.Trends in the incidence and associated factors of late-onset sepsis associated with improved survival in extremely preterm infants born at 23-26 weeks’ gestation: a retrospective study.BMC Pediatr. (2018) 18:172. 10.1186/s12887-018-1130-y

35.

HsuJFLaiMYLeeCWChuSMWuIHHuangHRet alComparison of the incidence, clinical features and outcomes of invasive candidiasis in children and neonates.BMC Infect Dis. (2018) 18:194. 10.1186/s12879-018-3100-2

36.

GlikmanDDaganRBarkaiGAverbuchDGuriAGivon-LaviNet alDynamics of severe and non-severe invasive pneumococcal disease in young children in israel following PCV7/PCV13 introduction.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2018) 37:1048–53. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002100

37.

GiannoniEAgyemanPKAStockerMPosfay-BarbeKMHeiningerUSpycherBDet alNeonatal sepsis of early onset, and hospital-acquired and community-acquired late onset: a prospective population-based cohort study.J Pediatr. (2018) 201:106–14.e4. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.048

38.

CanteyJBAndersonKRKalagiriRRMallettLH.Morbidity and mortality of coagulase-negative staphylococcal sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants.World J Pediatr. (2018) 14:269–73. 10.1007/s12519-018-0145-7

39.

BohanonFJNunez LopezOAdhikariDMehtaHBRojas-KhalilYBowen-JallowKAet alRace, income and insurance status affect neonatal sepsis mortality and healthcare resource utilization.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2018) 37:e178–84. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001846

40.

BenedictKRoyMKabbaniSAndersonEJFarleyMMHarbSet alNeonatal and pediatric candidemia: results from population-based active laboratory surveillance in four US locations, 2009-2015.J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. (2018) 7:e78–85. 10.1093/jpids/piy009

41.

Al-MouqdadMMAljobairFAlaklobiFATahaMYAbdelrahimAAsfourSS.The consequences of prolonged duration of antibiotics in premature infants with suspected sepsis in a large tertiary referral hospital: a retrospective cohort study.Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2018) 5:110–5. 10.1016/j.ijpam.2018.08.003

42.

WuIHTsaiMHLaiMYHsuLFChiangMCLienRet alIncidence, clinical features, and implications on outcomes of neonatal late-onset sepsis with concurrent infectious focus.BMC Infect Dis. (2017) 17:465. 10.1186/s12879-017-2574-7

43.

ReeIMCFustolo-GunninkSFBekkerVFijnvandraatKJSteggerdaSJLoprioreE.Thrombocytopenia in neonatal sepsis: incidence, severity and risk factors.PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0185581. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185581

44.

PieningBCGeffersCGastmeierPSchwabF.Pathogen-specific mortality in very low birth weight infants with primary bloodstream infection.PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0180134. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180134

45.

Mendoza-PalomarNBalasch-CarullaMGonzalez-Di LauroSCespedesMCAndreuAFrickMAet alEscherichia coli early-onset sepsis: trends over two decades.Eur J Pediatr. (2017) 176:1227–34. 10.1007/s00431-017-2975-z

46.

MaticsTJSanchez-PintoLN.Adaptation and validation of a pediatric sequential organ failure assessment score and evaluation of the sepsis-3 definitions in critically Ill children.JAMA Pediatr. (2017) 171:e172352. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352

47.

KuzniewiczMWPuopoloKMFischerAWalshEMLiSNewmanTBet alRisk-based approach to the management of neonatal early-onset sepsis.JAMA Pediatr. (2017) 171:365–71.

48.

HakanssonSLiljaMJacobssonBKallenK.Reduced incidence of neonatal early-onset group B streptococcal infection after promulgation of guidelines for risk-based intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis in Sweden: analysis of a national population-based cohort.Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (2017) 96:1475–83. 10.1111/aogs.13211

49.

GowdaHNortonRWhiteAKandasamyY.Late-onset neonatal sepsis-a 10-year review from north Queensland, Australia.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2017) 36:883–8. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001568

50.

DragesetMFjalstadJWMortensenSKlingenbergC.Management of early-onset neonatal sepsis differs in the north and south of Scandinavia.Acta Paediatr. (2017) 106:375–81. 10.1111/apa.13698

51.

ChenILChiuNCChiHHsuCHChangJHHuangDTet alChanging of bloodstream infections in a medical center neonatal intensive care unit.J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2017) 50:514–20. 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.08.023

52.

CarrDBarnesEHGordonAIsaacsD.Effect of antibiotic use on antimicrobial antibiotic resistance and late-onset neonatal infections over 25 years in an Australian tertiary neonatal unit.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2017) 102:F244–50. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310905

53.

BlanchardACFortinELaferriereCGoyerIMoussaAAutmizguineJet alComparative effectiveness of linezolid versus vancomycin as definitive antibiotic therapy for heterogeneously resistant vancomycin-intermediate coagulase-negative staphylococcal central-line-associated bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit.J Antimicrob Chemother. (2017) 72:1812–7. 10.1093/jac/dkx059

54.

AgyemanPKASchlapbachLJGiannoniEStockerMPosfay-BarbeKMHeiningerUet alEpidemiology of blood culture-proven bacterial sepsis in children in Switzerland: a population-based cohort study.Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2017) 1:124–33. 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30010-X

55.

VerstraeteEHMahieuLDe CoenKVogelaersDBlotS.Impact of healthcare-associated sepsis on mortality in critically ill infants.Eur J Pediatr. (2016) 175:943–52. 10.1007/s00431-016-2726-6

56.

TsaiMHLeeCWChuSMLeeITLienRHuangHRet alInfectious complications and morbidities after neonatal bloodstream infections: an observational cohort study.Medicine (Baltimore). (2016) 95:e3078.

57.

SchragSJFarleyMMPetitSReingoldAWestonEJPondoTet alEpidemiology of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis, 2005 to 2014.Pediatrics. (2016) 138:e20162013. 10.1542/peds.2016-2013

58.

PugniLRonchiABizzarriBConsonniDPietrasantaCGhirardiBet alExchange transfusion in the treatment of neonatal septic shock: a ten-year experience in a neonatal intensive care unit.Int J Mol Sci. (2016) 17:695. 10.3390/ijms17050695

59.

LauterbachRWilkBBochenskaAHurkalaJRadziszewskaR.Nonactivated protein C in the treatment of neonatal sepsis: a retrospective analysis of outcome.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2016) 35:967–71. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001247

60.

IvadyBKeneseiEToth-HeynPKerteszGTarkanyiKKassaCet alFactors influencing antimicrobial resistance and outcome of Gram-negative bloodstream infections in children.Infection. (2016) 44:309–21. 10.1007/s15010-015-0857-8

61.

FjalstadJWStensvoldHJBergsengHSimonsenGSSalvesenBRonnestadAEet alEarly-onset sepsis and antibiotic exposure in term infants: a nationwide population-based study in Norway.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2016) 35:1–6. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000906

62.

DeshpandePJainAShahPS.Outcomes associated with early removal versus retention of peripherally inserted central catheters after diagnosis of catheter-associated infections in neonates.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2016) 29:4082–7. 10.3109/14767058.2016.1157578

63.

BulkowsteinSBen-ShimolSGivon-LaviNMelamedRShanyEGreenbergD.Comparison of early onset sepsis and community-acquired late onset sepsis in infants less than 3 months of age.BMC Pediatr. (2016) 16:82. 10.1186/s12887-016-0618-6

64.

BerardiABaroniLBacchi ReggianiMLAmbrettiSBiasucciGBolognesiSet alThe burden of early-onset sepsis in Emilia-Romagna (Italy): a 4-year, population-based study.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2016) 29:3126–31. 10.3109/14767058.2015.1114093

65.

Ben SaidMHaysSBonfilsMJourdesERasigadeJPLaurentFet alLate-onset sepsis due to Staphylococcus capitis ‘neonatalis’ in low-birthweight infants: a new entity?J Hosp Infect. (2016) 94:95–8. 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.06.008

66.

YenMHHuangYCChenMCLiuCCChiuNCLienRet alEffect of intravenous immunoglobulin for neonates with severe enteroviral infections with emphasis on the timing of administration.J Clin Virol. (2015) 64:92–6. 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.01.013

67.

WeiHMHsuYLLinHCHsiehTHYenTYLinHCet alMultidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection among neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit at a medical center in central Taiwan.J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2015) 48:531–9. 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.08.025

68.

TsaiMHChuSMHsuJFLienRHuangHRChiangMCet alBreakthrough bacteremia in the neonatal intensive care unit: incidence, risk factors, and attributable mortality.Am J Infect Control. (2015) 43:20–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.09.022

69.

ShahJJefferiesALYoonEWLeeSKShahPSCanadian NeonatalN.Risk factors and outcomes of late-onset bacterial sepsis in preterm neonates born at < 32 weeks’.Gestation. Am J Perinatol. (2015) 32:675–82. 10.1055/s-0034-1393936

70.

SchwabFZibellRPieningBGeffersCGastmeierP.Mortality due to bloodstream infections and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2015) 34:235–40. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000532

71.

SchlapbachLJStraneyLAlexanderJMacLarenGFestaMSchiblerAet alMortality related to invasive infections, sepsis, and septic shock in critically ill children in Australia and New Zealand, 2002–13: a multicentre retrospective cohort study.Lancet Infect Dis. (2015) 15:46–54. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71003-5

72.

MitsiakosGPanaZ-DChatziioannidisIPiltsouliDLazaridouEKoulouridaVet alPlatelet mass predicts intracranial hemorrhage in neonates with gram-negative sepsis.J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2015) 37:519–23. 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000367

73.

LeeSMChangMKimKS.Blood culture proven early onset sepsis and late onset sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants in Korea.J Korean Med Sci. (2015) 30(Suppl. 1):S67–74. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.S1.S67

74.

LaiMYTsaiMHLeeCWChiangMCLienRFuRHet alCharacteristics of neonates with culture-proven bloodstream infection who have low levels of C-reactive protein (<==10 mg/L).BMC Infect Dis. (2015) 15:320. 10.1186/s12879-015-1069-7

75.

HsuJFChuSMLeeCWYangPHLienRChiangMCet alIncidence, clinical characteristics and attributable mortality of persistent bloodstream infection in the neonatal intensive care unit.PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0124567. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124567

76.

Cobos-CarrascosaESoler-PalacínPNieves LarrosaMBartoloméRMartín-NaldaAAntoinette FrickMet alStaphylococcus aureus bacteremia in children: changes during eighteen years.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2015) 34:1329–34. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000907

77.

BerginSPThadenJTEricsonJECrossHMessinaJClarkRHet alLeadership, neonatal Escherichia coli bloodstream infections: clinical outcomes and impact of initial antibiotic therapy.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2015) 34:933–6. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000769

78.

ChmielarczykAPobiegaMWójkowska-MachJRomaniszynDHeczkoPBBulandaM.Bloodstream infections due to Enterobacteriaceae among neonates in poland – molecular analysis of the isolates (Chmielarczyk) (2015).pdf.Polish J Microbiol. (2015) 64:217–25.

79.

VerstraeteEBoelensJDe CoenKClaeysGVogelaersDVanhaesebrouckPet alHealthcare-associated bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit over a 20-year period (1992-2011): trends in incidence, pathogens, and mortality.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2014) 35:511–8. 10.1086/675836

80.

TsaiMHChuSMHsuJFLienRHuangHRChiangMCet alRisk factors and outcomes for multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteremia in the NICU.Pediatrics. (2014) 133:e322–9. 10.1542/peds.2013-1248

81.

TsaiM-HHsuJ-FChuS-MLienRHuangH-RChiangM-Cet alIncidence, clinical characteristics and risk factors for adverse outcome in neonates with late-onset sepsis.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2014) 33:e7–13. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182a72ee0

82.

OeserCVergnanoSNaidooRAnthonyMChangJChowPet alNeonatal invasive fungal infection in England 2004–2010.Clin Microbiol Infect. (2014) 20:936–41. 10.1111/1469-0691.12578

83.

NatarajanGMondayLScheerTLulic-BoticaM.Timely empiric antimicrobials are associated with faster microbiologic clearance in preterm neonates with late-onset bloodstream infections.Acta Paediatr. (2014) 103:e418–23. 10.1111/apa.12734

84.

MittPMetsvahtTAdamsonVTellingKNaaberPLutsarIet alFive-year prospective surveillance of nosocomial bloodstream infections in an Estonian paediatric intensive care unit.J Hosp Infect. (2014) 86:95–9. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.11.002

85.

LutsarIChazallonCCarducciFITrafojerUAbdelkaderBde CabreVMet alCurrent management of late onset neonatal bacterial sepsis in five European countries.Eur J Pediatr. (2014) 173:997–1004. 10.1007/s00431-014-2279-5

86.

LevitOBhandariVLiFYShabanovaVGallagherPGBizzarroMJ.Clinical and laboratory factors that predict death in very low birth weight infants presenting with late-onset sepsis.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2014) 33:143–6. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000024

87.

DolapoODhanireddyRTalatiAJ.Trends of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit from 2000-2009.BMC Pediatr. (2014) 14:121. 10.1186/1471-2431-14-121

88.

ChuSMHsuJFLeeCWLienRHuangHRChiangMCet alNeurological complications after neonatal bacteremia: the clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes.PLoS One. (2014) 9:e105294. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105294

89.

ChenJJinLYangT.Clinical study of RDW and prognosis in sepsis new borns.Biomed Res. (2014) 25:576–79.

90.

BizzarroMJEhrenkranzRAGallagherPG.Concurrent bloodstream infections in infants with necrotizing enterocolitis.J Pediatr. (2014) 164:61–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.020

91.

BambergerEEBen-ShimolSRayaBAKatzAGivon-LaviNDaganRet alPediatric invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections in Israel in the era of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine: a nationwide prospective study.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2014) 33:477–81. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000193

92.

BalamuthFWeissSLNeumanMIScottHBradyPWPaulRet alPediatric severe sepsis in U.S. children’s hospitals.Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2014) 15:798–805. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000225

93.

WynnJLHansenNIDasACottenCMGoldbergRNSanchezPJet alEarly sepsis does not increase the risk of late sepsis in very low birth weight neonates.J Pediatr. (2013) 162:942–8.e1–3. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.027

94.

PrietoCLColomerBFSastreJB.Prognostic factors of mortality in very low-birth-weight infants with neonatal sepsis of nosocomial origin.Am J Perinatol. (2013) 30:353–8. 10.1055/s-0032-1324701

95.

LuthanderJBennetRGiskeCGNilssonAErikssonM.Age and risk factors influence the microbial aetiology of bloodstream infection in children.Acta Paediatr. (2013) 102:182–6. 10.1111/apa.12077

96.

HammoudMSAl-TaiarAFouadMRainaAKhanZ.Persistent candidemia in neonatal care units: risk factors and clinical significance.Int J Infect Dis. (2013) 17:e624–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.11.020

97.

FairchildKDSchelonkaRLKaufmanDACarloWAKattwinkelJPorcelliPJet alSepticemia mortality reduction in neonates in a heart rate characteristics monitoring trial.Pediatr Res. (2013) 74:570–5. 10.1038/pr.2013.136

98.

ErgazZBenensonSCohenMJBraunsteinRBar-OzB.No change in antibiotic susceptibility patterns in the neonatal ICU over two decades.Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2013) 14:164–70. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31824fbc19

99.

de HaanTRBeckersLde JongeRCSpanjaardLvan ToledoLPajkrtDet alNeonatal gram negative and Candida sepsis survival and neurodevelopmental outcome at the corrected age of 24 months.PLoS One. (2013) 8:e59214. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059214

100.

AhmedALutfiSAl-HailMAl-SaadiM.Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of microbial isolates from blood culture in the neonatal intensive care unit of Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar.Asian J Pharm Clin Res. (2013) 6(Suppl. 2):191–5.

101.

dams-ChapmanIABannCMDasAGoldbergRNStollBJWalshMCet alNeurodevelopmental outcome of extremely low birth weight infants with Candida infection.J Pediatr. (2013) 163:961–7.e3.

102.

WongJDowKShahPSAndrewsWLeeS.Percutaneously placed central venous catheter-related sepsis in Canadian neonatal intensive care units.Am J Perinatol. (2012) 29:629–34. 10.1055/s-0032-1311978

103.

VillaJAlbaCBarradoLSanzFDel CastilloEGViedmaEet alLong-term evolution of multiple outbreaks of Serratia marcescens bacteremia in a neonatal intensive care unit.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2012) 31:1298–300. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318267f441

104.

TsaiMHHsuJFLienRHuangHRChiangCCChuSMet alCatheter management in neonates with bloodstream infection and a percutaneously inserted central venous catheter in situ: removal or not?Am J Infect Control. (2012) 40:59–64. 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.04.051

105.

SoodBGShankaranSSchelonkaRLSahaSBenjaminDKJrSanchezPJet alCytokine profiles of preterm neonates with fungal and bacterial sepsis.Pediatr Res. (2012) 72:212–20. 10.1038/pr.2012.56

106.

ShaneALHansenNIStollBJBellEFSánchezPJShankaranSet alMethicillin-resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and meningitis in preterm infants.Pediatrics. (2012) 129:e914–22. 10.1542/peds.2011-0966

107.

MoriokaIMorikawaSMiwaAMinamiHYoshiiKKugoMet alCulture-proven neonatal sepsis in Japanese neonatal care units in 2006-2008.Neonatology. (2012) 102:75–80. 10.1159/000337833

108.

LivorsiDJMacneilJRCohnACBaretaJZanskySPetitSet alInvasive Haemophilus influenzae in the United States, 1999-2008: epidemiology and outcomes.J Infect. (2012) 65:496–504.

109.

HornikCPFortPClarkRHWattKBenjaminDKSmithPBet alEarly and late onset sepsis in very-low-birth-weight infants from a large group of neonatal intensive care units.Early Hum Dev. (2012) 88:S69–74. 10.1016/S0378-3782(12)70019-1

110.

HammoudMSAl-TaiarAThalibLAl-SweihNPathanSIsaacsD.Incidence, aetiology and resistance of late-onset neonatal sepsis: a five-year prospective study.J Paediatr Child Health. (2012) 48:604–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02432.x

111.

Grisaru-SoenGFriedmanTDollbergSMishaliHCarmeliY.Late-onset bloodstream infections in preterm infants: a 2-year survey.Pediatr Int. (2012) 54:748–53. 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03679.x

112.

AhmedALutfiSPvRAHailMRahmanSKassimW.Incidence of bacterial isolates from blood culture in the neonatal intensive care unit of tertiary care hospital.Int J Drug Dev Res. (2012) 4:359–67.

113.

WestonEJPondoTLewisMMMartell-ClearyPMorinCJewellBet alThe burden of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States, 2005-2008.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2011) 30:937–41. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318223bad2

114.

VergnanoSMensonESmithZKenneaNEmbletonNClarkePet alCharacteristics of invasive Staphylococcus aureus in United Kingdom neonatal units.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2011) 30:850–4.

115.

van den BroekPVerkadeHJHulzebosCV.Hyperbilirubinemia in infants with gram-negative sepsis does not affect mortality.Early Hum Dev. (2011) 87:515–9.

116.

StollBJHansenNISánchezPJFaixRGPoindexterBBMeursK.P. Vanet alEarly onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues.Pediatrics. (2011) 127:817–26.

117.

SchlapbachLJAebischerMAdamsMNatalucciGBonhoefferJLatzinPet alImpact of sepsis on neurodevelopmental outcome in a swiss national cohort of extremely premature infants.Pediatrics. (2011) 128:e348–57. 10.1542/peds.2010-3338

118.

Al-TaiarAHammoudMSThalibLIsaacsD.Pattern and etiology of culture-proven early-onset neonatal sepsis: a five-year prospective study.Int J Infect Dis. (2011) 15:e631–4. 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.004

119.

MetsvahtTIlmojaMLParmUMaipuuLMerilaMLutsarI.Comparison of ampicillin plus gentamicin vs. penicillin plus gentamicin in empiric treatment of neonates at risk of early onset sepsis.Acta Paediatr. (2010) 99:665–72. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01687.x

120.

KlingerGLevyISirotaLBoykoVLerner-GevaLReichmanBet alOutcome of early-onset sepsis in a national cohort of very low birth weight infants.Pediatrics. (2010) 125:e736–40. 10.1542/peds.2009-2017

121.

GuilbertJLevyCCohenRBacterial Meningitis groupDelacourtCRenolleauSet alLate and ultra late onset Streptococcus B meningitis: clinical and bacteriological data over 6 years in France.Acta Paediatr. (2010) 99:47–51. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01510.x

122.

AuritiCPrencipeGIngleseRAzzariCRonchettiMPTozziAet alRole of mannose-binding lectin in nosocomial sepsis in critically ill neonates.Hum Immunol. (2010) 71:1084–8. 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.08.012

123.

VarljenTRakicOSekulovicGJekicBMaksimovicNJanevskiMRet alAssociation between tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter -308 G/A polymorphism and early onset sepsis in preterm infants.Tohoku J Exp Med. (2019) 247:259–64. 10.1620/tjem.247.259

124.

MacooieAAFakhraieSHAfjehSAKazemianMKolahiAA.Comparing the values of serum high density lipoprotein (Hdl) level in neonatal sepsis.J Evol Med Dent Sci. (2019) 8:1772–6. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002682

125.

LealYAAlvarez-NemegyeiJLavadores-MayAIGiron-CarrilloJLCedillo-RiveraRVelazquezJR.Cytokine profile as diagnostic and prognostic factor in neonatal sepsis.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:2830–6. 10.1080/14767058.2018.1449828

126.

FreitasFTMAraujoAMeloMISRomeroGAS.Late-onset sepsis and mortality among neonates in a Brazilian intensive care unit: a cohort study and survival analysis.Epidemiol Infect. (2019) 147:e208. 10.1017/S095026881900092X

127.

CelikIHArifogluIArslanZAksuGBasAYDemirelN.The value of delta neutrophil index in neonatal sepsis diagnosis, follow-up and mortality prediction.Early Hum Dev. (2019) 131:6–9. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2019.02.003

128.

YusefDShalakhtiTAwadSAlgharaibehHKhasawnehW.Clinical characteristics and epidemiology of sepsis in the neonatal intensive care unit in the era of multi-drug resistant organisms: a retrospective review.Pediatr Neonatol. (2018) 59:35–41. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2017.06.001

129.

ThomasRWadulaJSeetharamSVelaphiS.Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles and case fatality rates of Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis in a neonatal unit.J Infect Dev Ctries. (2018) 12:211–9. 10.3855/jidc.9543

130.

TarakcıN.Neonatal septicemia in tertiary hospitals in Konya, Turkey.J Clin Anal Med. (2018) 9:187–91.

131.

StranieriIKanunfreKARodriguesJCYamamotoLNadafMIVPalmeiraPet alAssessment and comparison of bacterial load levels determined by quantitative amplifications in blood culture-positive and negative neonatal sepsis.Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. (2018) 60:e61. 10.1590/S1678-9946201860061

132.

Quintano NeiraRAHamacherSJapiassuAM.Epidemiology of sepsis in Brazil: incidence, lethality, costs, and other indicators for Brazilian unified health system hospitalizations from 2006 to 2015.PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0195873. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195873

133.

OguzSOncelMHalilHCakirUSerkantUOkurNet alCan endocan predict late-onset neonatal sepsis?J Pediatr Infect Dis. (2018) 14:096–102. 10.3855/jidc.11660

134.

EscalanteMJCeriani-CernadasJMD’ApremontIBancalariAWebbVGenesLet alLate onset sepsis in very low birth weight infants in the South American NEOCOSUR network.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2018) 37:1022–7. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001958

135.

SofticITahirovicHDi CiommoVAuritiC.Bacterial sepsis in neonates: single centre study in a Neonatal intensive care unit in Bosnia and Herzegovina.Acta Med Acad. (2017) 46:7–15. 10.5644/ama2006-124.181

136.

SiavashiVAsadianSTaheri-AslMKeshavarzSZamani-AhmadmahmudiMNassiriSM.Endothelial progenitor cell mobilization in preterm infants with sepsis is associated with improved survival.J Cell Biochem. (2017) 118:3299–307. 10.1002/jcb.25981

137.

OlugbuyiOSwabyKRobertsPChristieCKissoonN.Burden of paediatric sepsis in a tertiary centre from a developing country.West Indian Med J. (2018) 67:137–42.

138.

FuJDingYWeiBWangLXuSQinPet alEpidemiology of Candida albicans and non-C.albicans of neonatal candidemia at a tertiary care hospital in western China.BMC Infect Dis. (2017) 17:329. 10.1186/s12879-017-2423-8

139.

CaganEKiray BasEAskerHS.Use of colistin in a neonatal intensive care unit: a cohort study of 65 patients.Med Sci Monit. (2017) 23:548–54. 10.12659/msm.898213

140.

ZhouBLiuXWuJBJinBZhangYY.Clinical and microbiological profile of babies born with risk of neonatal sepsis.Exp Ther Med. (2016) 12:3621–5. 10.3892/etm.2016.3836

141.

TurhanEEGursoyTOvaliF.Factors which affect mortality in neonatal sepsis.Turk Pediatri Ars. (2015) 50:170–5. 10.5152/TurkPediatriArs.2015.2627

142.

MosayebiZMovahedianAHEbrahimB.Epidemiologic features of early onset sepsis in neonatal ward of Shabih Khani hospital in Kashan.Iran J Neonatol. (2015) 5:19–23.

143.

DramowskiAMadideABekkerA.Neonatal nosocomial bloodstream infections at a referral hospital in a middle-income country: burden, pathogens, antimicrobial resistance and mortality.Paediatr Int Child Health. (2015) 35:265–72. 10.1179/2046905515Y.0000000029

144.

DramowskiACottonMFRabieHWhitelawA.Trends in paediatric bloodstream infections at a South African referral hospital.BMC Pediatr. (2015) 15:33. 10.1186/s12887-015-0354-3

145.

CutlandCLSchragSJThigpenMCVelaphiSCWadulaJAdrianPVet alIncreased risk for group B Streptococcus sepsis in young infants exposed to HIV, Soweto, South Africa, 2004-2008(1).Emerg Infect Dis. (2015) 21:638–45.

146.

Arizaga-BallesterosVAlcorta-GarciaMRLazaro-MartinezLCAmezquita-GomezJMAlanis-CajeroJMVillelaLet alCan sTREM-1 predict septic shock & death in late-onset neonatal sepsis? A pilot study.Int J Infect Dis. (2015) 30:27–32.

147.

ThatrimontrichaiAChanvitanPJanjindamaiWDissaneevateSJefferiesAShahV.Trends in neonatal sepsis in a neonatal intensive care unit in Thailand before and after construction of a new facility.Asian Biomed. (2014) 8:771–8.

148.

OzkanHCetinkayaMKoksalNCelebiSHacimustafaogluM.Culture-proven neonatal sepsis in preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care unit over a 7 year period: coagulase-negative Staphylococcus as the predominant pathogen.Pediatr Int. (2014) 56:60–6. 10.1111/ped.12218

149.

MorkelGBekkerAMaraisBJKirstenGvan WykJDramowskiA.Bloodstream infections and antimicrobial resistance patterns in a South African neonatal intensive care unit.Paediatr Int Child Health. (2014) 34:108–14. 10.1179/2046905513Y.0000000082

150.

HentgesCRSilveiraRCProcianoyRSCarvalhoCGFilipouskiGRFuentefriaRNet alAssociation of late-onset neonatal sepsis with late neurodevelopment in the first two years of life of preterm infants with very low birth weight.J Pediatr (Rio J). (2014) 90:50–7. 10.1016/j.jped.2013.10.002

151.

de Souza RugoloLMBentlinMRMussi-PinhataMde AlmeidaMFLopesJMMarbaSTet alLate-onset sepsis in very low birth weight infants: a Brazilian neonatal research network study.J Trop Pediatr. (2014) 60:415–21. 10.1093/tropej/fmu038

152.

AkdagADilmenUHaqueKDilliDErdeveOGoekmenT.Role of pentoxifylline and/or IgM-enriched intravenous immunoglobulin in the management of neonatal sepsis.Am J Perinatol. (2014) 31:905–12. 10.1055/s-0033-1363771

153.

TurnerCTurnerPHoogenboomGAye Mya TheinNMcGreadyRPhakaudomKet alA three year descriptive study of early onset neonatal sepsis in a refugee population on the Thailand Myanmar border.BMC Infect Dis. (2013) 13:601. 10.1186/1471-2334-13-601

154.

BallotDEBosmanNNanaTRamdinTCooperPA.Background changing patterns of neonatal fungal sepsis in a developing country.J Trop Pediatr. (2013) 59:460–4. 10.1093/tropej/fmt053

155.

Al-TalibHAl-KhateebAAl-KhalidiR.Neonatal septicemia in neonatal intensive care units: epidemiological and microbiological analysis of causative organisms and antimicrobial susceptibility.Int Med J. (2013) 20:36–40.

156.

SchragSJCutlandCLZellERKuwandaLBuchmannEJVelaphiSCet alRisk factors for neonatal sepsis and perinatal death among infants enrolled in the prevention of perinatal sepsis trial, Soweto, South Africa.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2012) 31:821–6. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825c4b5a

157.

LealYAAlvarez-NemegyeiJVelazquezJRRosado-QuiabUDiego-RodriguezNPaz-BaezaEet alRisk factors and prognosis for neonatal sepsis in southeastern Mexico: analysis of a four-year historic cohort follow-up.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2012) 12:48. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-48

158.

FreitasBAPelosoMManellaLDFranceschini SdoCLongoGZGomesAPet alLate-onset sepsis in preterm children in a neonatal intensive care unit: a three-year analysis.Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. (2012) 24:79–85.

159.

BallotDENanaTSriruttanCCooperPA.Bacterial bloodstream infections in neonates in a developing country.ISRN Pediatr. (2012) 2012:508512. 10.5402/2012/508512

160.

AfsharpaimanSTorkamanMSaburiAFarzaampurAAmirsalariSKavehmaneshZ.Trends in incidence of neonatal sepsis and antibiotic susceptibility of causative agents in two neonatal intensive care units in tehran, I.R iran.J Clin Neonatol. (2012) 1:124–30. 10.4103/2249-4847.101692

161.

MutluYAMSayginBYilmazGBayramoðluGKöksalI.Neonatal sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria in a neonatal intensive care unit- a six years analysis.Hong Kong J Paediatr. (2011) 16:253–7.

162.

KardanaIM.Incidence and factors associated with mortality of neonatal sepsis.Paediatr Indones. (2011) 51:144–8.

163.

AletayebSMHKhosraviADDehdashtianMKompaniFArameshMR.Identification of bacterial agents and antimicrobial susceptibility of neonatal sepsis: a 54-month study in a tertiary hospital.Afr J Microbiol Res. (2011) 5:528–31.

164.

YilmazNOAgusNHelvaciMKoseSOzerESahbudakZ.Change in pathogens causing late-onset sepsis in neonatal intensive care unit in Izmir, Turkey.Iran J Pediatr. (2010) 20:451.

165.

Turkish Neonatal Society, Nosocomial Infections Study Group.Nosocomial infections in neonatal units in Turkey: epidemiology, problems, unit policies and opinions of healthcare workers.Turk J Pediatr. (2010) 52:50–7.

166.

BasAYDemirelNZencirogluAGölNTanirG.Nosocomial blood stream infections in a neonatal intensive care unit in Ankara, Turkey.Turk J Pediatr. (2010) 52:464.

167.

FahmeySSHodeibMRefaatKMohammedW.Evaluation of myocardial function in neonatal sepsis using tissue Doppler imaging.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2019) 33:3752–6. 10.1080/14767058.2019.1583739

168.

EllahonyDMEl-MekkawyMSFaragMM.A study of red cell distribution width in neonatal sepsis.Pediatr Emerg Care. (2017) 36:378–83.

169.

TankPJOmarAMusokeR.Audit of antibiotic prescribing practices for neonatal sepsis and measurement of outcome in new born unit at Kenyatta national hospital.Int J Pediatr. (2019) 2019:7930238. 10.1155/2019/7930238

170.

MartinSLDesaiSNanavatiRColahRBGhoshKMukherjeeMB.Red cell distribution width and its association with mortality in neonatal sepsis.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2019) 32:1925–30. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1421932

171.

BhatJCharooBAshrafYQaziI.Systemic Candida infection in preterm babies: experience from a tertiary care hospital of North India.J Clin Neonatol. (2019) 8:151–4.

172.

SinghLDasSBhatVBPlakkalN.Early neurodevelopmental outcome of very low birthweight neonates with culture-positive blood stream infection: a prospective cohort study.Cureus. (2018) 10:e3492. 10.7759/cureus.3492

173.

KumarSShankarBAryaSDebMChellaniH.Healthcare associated infections in neonatal intensive care unit and its correlation with environmental surveillance.J Infect Public Health. (2018) 11:275–9. 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.08.005

174.

KhattabAAEl-MekkawyMSHelwaMAOmarES.Utility of serum resistin in the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis and prediction of disease severity in term and late preterm infants.J Perinat Med. (2018) 46:919–25. 10.1515/jpm-2018-0018

175.

KannanRRaoSSMithraPDhanashreeBBaligaSBhatKG.Diagnostic and prognostic validity of proadrenomedullin among neonates with sepsis in tertiary care hospitals of Southern India.Int J Pediatr. (2018) 2018:7908148. 10.1155/2018/7908148

176.

JajooMManchandaVChaurasiaSSankarMJGautamHAgarwalRet alAlarming rates of antimicrobial resistance and fungal sepsis in outborn neonates in North India.PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0180705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180705

177.

FahmeySSMostafaHElhafeezNAHussainH.Diagnostic and prognostic value of proadrenomedullin in neonatal sepsis.Korean J Pediatr. (2018) 61:156–9. 10.3345/kjp.2018.61.5.156

178.

El ShimyMSEl-RaggalNMEl-FarrashRAShaabanHAMohamedHEBarakatNMet alCerebral blood flow and serum neuron-specific enolase in early-onset neonatal sepsis.Pediatr Res. (2018) 84:261–6. 10.1038/s41390-018-0062-4

179.

BanupriyaNBhatBVBenetBDCatherineCSridharMGParijaSC.Short term oral zinc supplementation among babies with neonatal sepsis for reducing mortality and improving outcome – a double-blind randomized controlled trial.Indian J Pediatr. (2018) 85:5–9. 10.1007/s12098-017-2444-8

180.

BandyopadhyayTKumarASailiARandhawaVS.Distribution, antimicrobial resistance and predictors of mortality in neonatal sepsis.J Neonatal Perinatal Med. (2018) 11:145–53. 10.3233/NPM-1765

181.

AhmadMSAhmadDMedhatNZaidiSAHFarooqHTabraizSA.Electrolyte abnormalities in neonates with probable and culture-proven sepsis and its association with neonatal mortality.J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. (2018) 28:206–9. 10.29271/jcpsp.2018.03.206

182.

ShobowaleEOSolarinAUElikwuCJOnyedibeKIAkinolaIJFaniranAA.Neonatal sepsis in a Nigerian private tertiary hospital: bacterial isolates, risk factors, and antibiotic susceptibility patterns.Ann Afr Med. (2017) 16:52–8.

183.

ShabaanAENourIElsayed EldeglaHNasefNShoumanBAbdel-HadyH.Conventional versus prolonged infusion of meropenem in neonates with gram-negative late-onset sepsis: a randomized controlled trial.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2017) 36:358–63.

184.

SealeACObieroCWJonesKDBarsosioHCThitiriJNgariMet alShould first-line empiric treatment strategies for neonates cover coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections in Kenya?Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2017) 36:1073–8. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001699

185.

ChohanMNDassDTalrejaSAhmedN.Bacterial resistance in neonates with sepsis, not responding to first line antibiotics.Med Forum Mon. (2017) 28:30–3.

186.

AhmadMSMemoodRWahidAMehboobNAliNNasirW.Prevalence of neutropenia in cases of neonatal sepsis.Pak Pediatr J. (2017) 41:116–8.

187.

ChellaniHKaurCKumarSAryaS.Acute kidney injury in neonatal sepsis: risk factors, clinical profile, and outcome.J Pediatr Infect Dis. (2017) 13:32–6. 10.4103/1319-2442.338284

188.

BanupriyaNVishnu BhatBBenetBDSridharMGParijaSC.Efficacy of zinc supplementation on serum calprotectin, inflammatory cytokines and outcome in neonatal sepsis – a randomized controlled trial.J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2017) 30:1627–31. 10.1080/14767058.2016.1220524

189.

ArowosegbeAOOjoDADedekeIOShittuOBAkingbadeOA.Neonatal sepsis in a Nigerian tertiary hospital: clinical features, clinical outcome, aetiology and antibiotic susceptibility pattern.Southern Afr J Infect Dis. (2017) 32:127–31.

190.

PradhanRJainPPariaASahaASahooJSenAet alRatio of neutrophilic CD64 and monocytic HLA-DR: a novel parameter in diagnosis and prognostication of neonatal sepsis.Cytometry B Clin Cytom. (2016) 90:295–302. 10.1002/cyto.b.21244

191.

Kumar DebbarmaSMajumdarTKumar ChakrabartiSIslamN.Proportion of neonatal sepsis among study subjects with or without jaundice in a tertiary care centre of Agartala, Tripura.J Evol Med Dent Sci. (2016) 5:7141–5.

192.

KabweMTemboJChilukutuLChilufyaMNgulubeFLukwesaCet alEtiology, antibiotic resistance and risk factors for neonatal sepsis in a large referral center in Zambia.Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2016) 35:e191–8. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001154

193.