- 1Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

- 2School of Nursing, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 3Department of Laboratory Medicine, Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 4College of Life Sciences, Northwestern University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

- 5University of Sydney Camperdown, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 6School of Health Management, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 7Department of emergency medicine, Sichuan Provincial People′s Hospital, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China

Background: The effectiveness of tranexamic acid (TXA) in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) remains controversial and appears to vary with the severity of the injury. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the impact of TXA on mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI and severe TBI.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted across PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library database, Chinese CNKI database, and clinical trial repositories was conducted up to 1 May 2024. Studies comparing TXA with placebo were performed for relevant studies comparing TXA for mild to moderate and severe TBI were included. After literature screening, data were independently extracted and pooled using random-effects or fixed-effects models according to the magnitude of heterogeneity. Certainty of findings was assessed using the GRADE methodology.

Results: Sixteen studies involving 15,015 patients were analyzed. TXA could significantly reduce the 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI (RR, 0.71; 95% CI 0.60–0.85; I2 = 0%), supported by randomized controlled trials (RR: (0.74; 95% CI:0.62–0.89; I2 = 0%; high certainty) and cohort studies: (RR:0.47; 95% 0.26–0.86; I2 = 0%; low certainty). However, no mortality benefit was observed in severe TBI patients (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.93–1.19; I2 = 21%), as demonstrated in RCTs (RR:0.98; 95% CI, 0.91–1.05; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty) and cohort studies (RR,1.23; 95% CI:1.08–1.4; I2 = 0%; low certainty).

Conclusion: The findings suggest that the therapeutic effectiveness of TXA varies by the severity of brain injury. Post-injury administration of TXA significantly reduced 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI (GCS: 9–15) but showed no benefit in patients with severe TBI (GCS: 3–8). Further research is needed to investigate the effect of TXA on thromboembolic events and to determine optimal dosing strategies, particularly for severe TBI patients.

1 Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide (Liesemer et al., 2014; Maas et al., 2017). The yearly incidence of TBI is estimated at 50 million cases worldwide, with complicated intracranial hemorrhage being the most fatal complication (Taylor et al., 2017; Final results of MRC CRASH, 2005). According to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), TBI is categorized into 3 severity levels based on the GCS: mild (GCS score 13–15), moderate (GCS score 9–12), and severe (GCS score 3–8) (Fakharian et al., 2018; Rundhaug et al., 2015).

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic agent that reduces bleeding by inhibiting plasmin production and preventing fibrin degradation (Wang and Santiago, 2022). TXA is currently widely used in trauma patients (Ramirez et al., 2017), but its role in patients with traumatic brain injury remains controversial. The CRASH-3 (CRASH-3 trial collaborators, 2019) study demonstrated that TXA can reduce mortality in TBI patients; however, the benefits appears to vary among patients with different severity levels.

Given these findings, we hypothesized that TXA has different effects on patients with varying severities of traumatic brain injury. This study summarizes the efficacy of TXA in reducing mortality across different levels of TBI severity.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy

The meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and adhered to the Guidelines for Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Research, as outlined in the study protocol (Page et al., 2021) (ID: CRD42023422701). A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Libraries, Chinese CNKI Database, Web of Science, and clinical trial repositories, covering studies published up to 1 May 2024.

The search strategy utilized a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)/Emtree terms and title/abstract keywords, specifically “tranexamic acid” and “traumatic brain injury”. Detailed search strategies are provided in the Supplementary Material, with an overview of the process illustrated in Figure 1.

Two junior investigators independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies to exclude those irrelevant to the research question. Subsequently, full texts of the screening articles were reviewed based on predefined screening criteria. The reference lists of included studies were also examined to identify additional relevant publications. Discrepancies in study selection or data extraction were resolved through discussions with two senior researchers.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: (1) Eligible study types were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, or case-control studies; (2) Participants included patients aged 15 or older with acute TBI, confirmed by GCS score or CT scan showing any intracranial hemorrhage and no major extracranial hemorrhage; (3) There was a clear classification of the severity of brain injury, such as according to severity, Mild: GCS Score (13–15), Moderate: GCS Score (9–12), Severe: GCS Score (3–8); (4) The intervention is TXA treatment with intravenous infusion in any dosing regimen, and the control group is treated with placebo; (5) Reported deaths in patients with brain injury of varying severity, including 28-day, 30-day or hospital discharge deaths; (6) Reported related thromboembolic events, such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) Studies that did not involve patients with TBI; (2) Studies lacking a clear classification of brain injury severity (mild, moderate, and severe).

The PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design) criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies into qualitative and quantitative meta-analysis are detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

2.3 Data extraction

Two junior researchers independently extracted data using predetermined forms. Any disagreements during the extraction process were resolved through discussion. Based on the characteristics of the included studies, patients with mild and moderate TBI were grouped into a single category for analysis. The data extracted included the following information: author and year of publication, country or region where study was conducted, patient demographics, including age (TXA/placebo groups) and percentage of males (TXA/placebo), number of patinets with mild to moderate TBI and severe TBI in the TXA group, mortality outcomes specifically the number of 28-day or hospital discharged deaths in mild to moderate and severe TBI patients (TXA), study design, TXA dosing and the timing of TXA administration after injury, as well as the reported primary outcomes.

2.4 Assessment of study quality

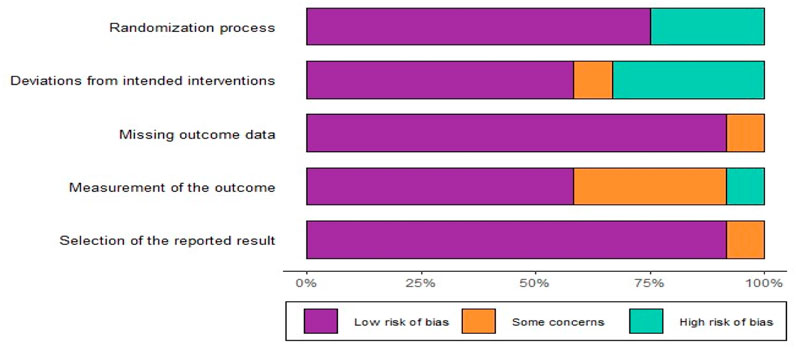

The 16 articles included in the analysis comprised RCTs and observational studies. The quality of these articles was evaluated using appropriate tools. For RCTs, we used the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2) (Sterne et al., 2019) was used, which assess bias in six areas: (1) the randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of outcomes, (5) selection of reported results, and (6) overall bias.

For observational studies, the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized intervention Studies (ROBINS-I) (Sterne et al., 2016) was applied, evaluating bias in seven areas: (1) bias due to confounding, (2) participant selection, (3) classification of interventions, (4) deviations from intended interventions, (5) missing data, (6) measurement of outcomes, and (7) selection of reported results.

Additionally, certainty of the evidence for each outcome was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (Guyatt et al., 2008). Discrepancies in RoB or GRADE assessment were resolved through consensus among researchers. The Guideline Development Tool (https://www.gradepro.org) was used to create the Summary of Findings table.

2.5 Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R 4.3.1 software to generate correlation forest plots using both random effects models and fixed-effects models on the data. Discrepancies in the analysis were resolved through discussion. To assess the heterogeneity between trials, the chi-square test of homogeneity (where p < 0.1 indicates significant heterogeneity), and I2 statistics (values ≥50% considered reference values for potentially important heterogeneity) were used to assess heterogeneity between trials (Higgins et al., 2003). Subgroup analyses were performed based on study type, and the results of both random-effects and fixed-effects models were presented in forest plots. For conservative estimation, we believe that when I2 ≠ 0 we explain the pooled results of the random effects model; conversely, when I2 = 0, we explain the pooled results of the fixed effects model. In addition, we performed sensitivity analyses based on sample size and dose of TXA, with special attention given to trials with large sample sizes and trials with non-standard doses of TXA. Finally, we plotted colored funnel plots with outlines added to show relevant biases more clearly.

3 Results

3.1 Search result

Following the complete searching strategy, we identified a total of 982 records in the electronic database. After removing duplicates, screening titles, abstracts, and full texts where applicable, we included 10 reports of RCTs and 6 cohort studies for detailed evaluation (Figure 1). Due to the stratification of patients based on TBI in some trials, we identified 8 studies focusing on patients with mild to moderate TBI and 12 studies on patients with severe TBI.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. A total of 10 RCTs and 6 cohort studies were included in the analysis. These studies collectively involved 15,015 patients with acute TBI. Of these, 7,245 patients had mild and moderate TBI, and 7,770 patients had severe TBI.

In the included quantitative synthesis are 8 articles (5 RCTs and 3 cohort studies) focused on patients with mild to moderate TBI, and 12 articles (8 RCTs and 4 cohort studies) focused on patients with severe TBI. This divison reflects that some studies, such as CRASH-3, included patients across both mild/moderate and severe TBI categories.

Four studies used non-standard dosing regimens of TXA (CRASH-3 trial collaborators, 2019; Hobensack and Phan, 2021; Yutthakasemsunt et al., 2013; Morte et al., 2019). One study (Hobensack and Phan, 2021) administered TXA at doses of 1 g (151 patients), 2 g (141 patients), and 3 g (150 patients). Another study (Rowell et al., 2020) reported doses of 1 g (312 patients) and 2 g (345 patients). A third study (Bossers et al., 2021) administered a uniform dose of 1 g to all TBI patients, while a fourth study (Walker et al., 2020) did not specify the relevant dose of TXA. In contrast, the standard dosing regimen in the remaining studies involved a 1 g TXA bolus followed by 1 g TXA maintenance/Patients receiving non-standard doses represented 17.7% of the total study population. Three articles (Yutthakasemsunt et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2020; Chen, 2018) did not report the time window for TXA administration. For the remaining articles, reported administration of tranexamic acid was reported within 8 h of injury. In addition, we summarized the characteristics of the excluded studies, as detailed in Supplementary Table S2.

3.3 Quality assessment results

Among the 10 RCTs analyzed, four studies were identified as having a high risk of bias using the Cochrane RoB-2 tool, two trials were categorized as high RoB, and four trials were assessed as having a low RoB (Figures 2, 3). Due to the unique nature of the studies, allocation concealment was often challenging to achieve. Nevertheless, all included RCTs provided complete and non-selective outcome data. For the six cohort studies, two articles limited participant populations to war injuries, posing a significant bias risk based on the ROBINS-I tool (Supplementary Figures S1,S2). These limitations underline the variability in study design and participant selection across the included studies.

3.4 Outcomes

Figure 4. Shows the effect of TXA on 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI, based on data from 5 RCTs and 3 cohort studies, comprising 3,598 patients in the TXA group and 3,647 in the control group. The results showed that TXA can significantly reduce 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI (RR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.60–0.85; P = 0.45; I2 = 0%). Subgroup analyses were performed according to study type showed that TXA was effective in reducing mortality in both the RCTs subgroup (RR = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.62–0.89; I2 = 0%) and the cohort study subgroup (RR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.26–0.86; I2 = 0%) were shown to reduce 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI.

Figure 5 presents the effect of TXA on 28-day mortality in patients with severe TBI, based on 5 RCTs and 3 cohort studies with 3,865 in the TXA group and 3,905 in the control group. The findings indicated that TXA did not reduce 28-day mortality in patients with severe TBI (RR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.93–1.19; P = 0.24; I2 = 21%). Subgroup analyses were performed according to study type. TXA did not reduce 28-day mortality in patients with severe TBI in the RCTs subgroup (RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.91–1.06; I2 = 0%) but increased 28-day mortality in patients with severe TBI in a cohort study subgroup (RR = 1.23; 95% CI, 1.08–1.40; I2 = 0%).

Table 2 summarizes the findings for all outcomes including the certainty of evidence. A comprehensive analysis of RCTs found that TXA reduced 28-day mortality in patients with mild-to-moderate TBI [RR 0.74; 95% CI 0.62–0.89; risk difference (RD) 1.0% reduction; 95% CI 0.8% reduction to 2.9% increase; high degree of certainty], but not in patients with severe TBI [RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.93–1.19; risk difference (RD) reduction 0.6%; 95% CI-1.6%–2.9%; moderate certainty], cohort studies, thromboembolic complications, and analysis of patients with a GOS score less than 4 were determined to have low or very low certainty.

3.5 Sensitivity analyses and publication bias

We used R 4.3.1 software to conduct sensitivity analysis and publication bias. Sensitivity analysis showed no significant differences between the pooled results for calculations that did not exceed the 95% confidence limit (Supplementary Figures S6,S7). We also generated funnel plots to assess publication bias (Supplementary Figures S8,S9. However, the funnel plot showed significant asymmetry between studies (Supplementary Figure S8), suggesting possible publication bias.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis show that TXA reduces 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI (GCS: 9–15) but not in patients with severe TBI (GCS: 3–8). Due to the small sample size and limited number of events, the current low-certainty evidence may suggest that TXA does not significantly impact disability outcomes in TBI of varying severity, nor does it increase the risk of thromboembolic complications.

The findings of the CRASH-3 trial are particularly noteworthy. In fact, our results are also consistent with the relevant conclusions of the trial (CRASH-3 trial collaborators, 2019). Standard doses of TXA appear to have varying benefits depending on TBI severity. Because TXA can inhibit the fibrinolytic system, it can pass through the blood-brain barrier and reduce the level of fibrinolysis early after injury (Supplementary Figure S10), thereby reducing the expansion of intracranial hematoma, so it is suitable for central nervous system hemorrhage (Jokar et al, 2017; Maegele, 2021; CRASH-2 Collaborators Intracranial Bleeding Study, 2011). Previous studies have shown that TXA can significantly reduce the haematoma size in patients with cerebral hemorrhage (Safari et al., 2020), and the extent of hematoma is closely associated with patients’ prognosis (Zille et al., 2022). It is worth reminding that these TBI patients did not have severe damage to other organs. However, in cases of severe TBI, the large volume of intracranial hemorrhage often leads to symptoms such as brain herniation, and pupil insensitivity to light reflex may appear in the early stage of trauma, and the use of tranexamic acid may not be effective at this time (Maegele, 2021; Roberts et al., 2013). It is worth noting that the cohort study shows that tranexamic acid can increase the mortality of patients with severe TBI. Possible explanations for this evidence may be related to the hypercoagulable state after severe brain injury that may promote cerebral vascular microthrombosis or systemic diffuse intravascular coagulation (Harhangi et al., 2008). In addition, since patients with severe brain trauma have a considerable risk of deep venous thrombosis (For the EPO-TBI investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group et al., 2017), the use of TXA may break the balance mechanism of anticoagulation and fibrinolysis, which may lead to poor prognosis. In addition, as the severity of injury in patients with severe TBI increases, extracranial injury and unmeasured confounding factors may also lead to an increased risk of death in such patients. These findings highlight the need for future research to determine appropriate TXA dosing for patients with severe TBI.

Three meta-analyses on TXA for all-cause mortality in TBI patients have been previously published (Weng et al., 2019; July and Pranata, 2020; Lawati et al., 2021), but none performed stratified analyses based on the severity of TBI patients. July et al.'s study (July and Pranata, 2020) showed that TXA can reduce mortality in TBI patients but included non-TBI patients in the CRASH-2 trial in their analysis. To ensure a more robust conclusion, we included only TBI patients from the CRASH-2 trial in our analysis. The meta-analysis published by Weng et al. (Weng et al., 2019) reported an impact of TXA on all-cause mortality in TBI patients: RR: 0.64 (0.41–1.00), but they included three small sample trials previously published. In contrast, our meta-analysis conducted a detailed search and included all relevant studies, including the CRASH-3trial. The meta-analysis published by Lawati et al. (Lawati et al., 2021) showed that TXA could not reduce the mortality of patients with traumatic brain injury [ RR0.95 (0.88–1.02) ]. They failed to stratify the severity of TBI patients, as the wider confidence interval buried the benefits of some mild to moderate TBI, as shown in the stratification results of the CRASH-3 trial.

Due to the lack of robust data on the side effects of TXA in TBI patients of different severity levels, the limited sample size and number of events indicate that there is no statistical difference in thromboembolic events between the TXA group and the placebo group in TBI patients of different severity levels, which is consistent with the results of this large randomized controlled trial previously published (CRASH-3 trial collaborators, 2019; Hobensack and Phan, 2021; Rowell et al., 2020). However, the relatively low level of evidence for related complications, as assessed in GRADE, creates uncertainty about whether TXA use might increase the incidence of thromboembolic or other complications. Future research should explore the benefits of TXA in patients with mild, moderate, and severe TBI as well as its impact on specific types of hemorrhage, including subdural, subarachnoid, and cerebral parenchymal hemorrhage. Related thromboembolic events can also be explored in greater detail across different TBI severity levels. Notably, most of the studies included in this analysis administered TXA at a standard dose of a 1 g bolus followed by a 1 g maintenance dose within 3 h post-injury. However, this standard dose of TXA has proven ineffective for patients with severe TBI. Therefore, further research is essential to identify the optimal TXA dosing regimen for severe TBI patients to improve outcomes.

This study has several advantages. Firstly, it is the first study to stratify TBI patients by severity, highlighting the potential benefits of TXA for patients with mild to moderate TBI. Secondly, it includes a comprehensive literature search of all relevant studies and incorporates a GRADE evaluation to assess the certainty of evidence. However, there are also limitations. First of all, although we try to extract data exclusively from relevant trials involving isolated TBI patients, very few trials still include cases of mild extracranial injury. In addition, this study primarily focuses on the effects of standard-dose TXA on patients with varying TBI severity. While a few studies utilized non-standard dosing regimens, their proportions were relatively small, and we conducted a subgroup analysis to show that after excluding trials with non-standard doses of TXA, the results were consistent with the conclusions of this article (Supplementary Figures S3, S4, S5). Furthermore, the available evidence, particularly from heavily weighted studies at high risk of bias, is insufficient to establish a definitive causal relationship between TBI and the outcomes studied. Moreover, we see that these studies from different development regions show that, due to the economic disparity, patients with severe traumatic brain injury in less developed regions may have a higher mortality rate compared to those in more developed regions, depending on the effectiveness of treatment. Therefore, the associations presented in this meta-analysis must be interpreted with caution. Future studies with more rigorous designs, more transparent reporting, and better control for key confounders are needed to increase the certainty of the evidence.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings suggest that the therapeutic effectiveness of tranexamic acid varies with the severity of the traumatic brain injury. When administered early after injury, TXA significantly reduces 28-day mortality in patients with mild to moderate TBI (GCS:9–15) but does not demonstrate the same benefit in severe TBI patients (GCS:3–8). Further research is required to better understand the effect of TXA on thromboembolic events and to explore optimal dosing strategies, particularly for patients with severe TBI.

Author contributions

WB: Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Software, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis. MQ: Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Software, Data curation, Writing – original draft. LD: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft. YL: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. KY: Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZW: Writing – original draft, Data curation. JZ: Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition. PZ: Investigation, Resources, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Project administration.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the people who conducted the studies that contributed to this meta-analysis and systematic review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1677936/full#supplementary-material

References

Bossers, S. M., Loer, S. A., Bloemers, F. W., Den Hartog, D., Van Lieshout, E. M. M., Hoogerwerf, N., et al. (2021). Association between prehospital tranexamic acid administration and outcomes of severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 78, 338–345. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4596

Chakroun-Walha, O., Samet, A., Jerbi, M., Nasri, A., Talbi, A., Kanoun, H., et al. (2019). Benefits of the tranexamic acid in head trauma with no extracranial bleeding: a prospective follow-up of 180 patients. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 45, 719–726. doi:10.1007/s00068-018-0974-z

Chen, (2018). “Efficacy of tranexamic acid in preventing intracranial hematoma enlargement in patients with traumatic brain injury,” in Stroke and nervous diseases.

CRASH-2 Collaborators (Intracranial Bleeding Study) (2011). Effect of tranexamic acid in traumatic brain injury: a nested randomised, placebo controlled trial (CRASH-2 intracranial bleeding study). BMJ 343, d3795. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3795

CRASH-3 trial collaborators (2019). Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 394, 1713–1723. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32233-0

de Tymowski, C., Augustin, P., Houissa, H., Allou, N., Montravers, P., Delzongle, A., et al. (2017). CRRT connected to ECMO: managing high pressures. ASAIO J. 63, 48–52. doi:10.1097/MAT.0000000000000441

Ebrahimi, P., Mozafari, J., Ilkhchi, R. B., Hanafi, M. G., and Mousavinejad, M. (2019). Intravenous tranexamic acid for subdural and epidural intracranial hemorrhage: randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. RRCT. 14, 286–291. doi:10.2174/1574887114666190620112829

Fakharian, E., Abedzadeh-kalahroudi, M., and Atoof, F. (2018). Effect of tranexamic acid on prevention of hemorrhagic mass growth in patients with traumatic brain injury. World Neurosurg. 109, e748–e753. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.075

Final results of MRC CRASH. (2005). Final results of MRC CRASH, a randomised placebo-controlled trial of intravenous corticosteroid in adults with head injury—outcomes at 6 months. Lancet. 365:1957–1959. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66552-X

For the EPO-TBI investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group Skrifvars, M. B., Bailey, M., French, C., Nichol, A., Little, L., et al. (2017). Venous thromboembolic events in critically ill traumatic brain injury patients. Intensive Care Med. 43, 419–428. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4655-2

Guyatt, G. H., Oxman, A. D., Vist, G. E., Kunz, R., Falck-Ytter, Y., Alonso-Coello, P., et al. (2008). GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 336, 924–926. doi:10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Harhangi, B. S., Kompanje, E. J. O., Leebeek, F. W. G., and Maas, A. I. R. (2008). Coagulation disorders after traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 150, 165–175. doi:10.1007/s00701-007-1475-8

Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., and Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 327, 557–560. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Hobensack, M., and Phan, N. (2021). Tranexamic acid during prehospital transport in patients at risk for hemorrhage after injury; A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J. Emerg. Med. 60, 416–417. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.02.014

Jokar, A., Ahmadi, K., Salehi, T., Sharif-Alhoseini, M., and Rahimi-Movaghar, V. (2017). The effect of tranexamic acid in traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Chin. J. Traumatology. 20, 49–51. doi:10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.02.005

July, J., and Pranata, R. (2020). Tranexamic acid is associated with reduced mortality, hemorrhagic expansion, and vascular occlusive events in traumatic brain injury – meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Neurol. 20, 119. doi:10.1186/s12883-020-01694-4

Lawati, K. A., Sharif, S., Maqbali, S. A., Rimawi, H. A., Petrosoniak, A., Belley-Cote, E. P., et al. (2021). Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in acute traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Intensive Care Med. 47, 14–27. doi:10.1007/s00134-020-06279-w

Liesemer, K., Riva-Cambrin, J., Bennett, K. S., Bratton, S. L., Tran, H., Metzger, R. R., et al. (2014). Use of rotterdam CT scores for mortality risk stratification in children with traumatic brain injury. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 15, 554–562. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000000150

Maas, A. I. R., Menon, D. K., Adelson, P. D., Andelic, N., Bell, M. J., Belli, A., et al. (2017). Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurology 16, 987–1048. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30371-X

Maegele, M. (2021). Prehospital tranexamic acid (TXA) in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Transfus. Med. Rev. 35, 87–90. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2021.08.003

Morte, D., Lammers, D., Bingham, J., Kuckelman, J., Eckert, M., and Martin, M. (2019). Tranexamic acid administration following head trauma in a combat setting: does tranexamic acid result in improved neurologic outcomes? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 87, 125–129. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002269

Mousavinejad, M., Mozafari, J., Ilkhchi, R. B., Hanafi, M. G., and Ebrahimi, P. (2020). Intravenous tranexamic acid for brain contusion with intraparenchymal hemorrhage: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. RRCT. 15, 70–75. doi:10.2174/1574887114666191118111826

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 134, 178–189. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001

Ramirez, R. J., Spinella, P. C., and Bochicchio, G. V. (2017). Tranexamic acid update in trauma. Crit. Care Clin. 33, 85–99. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2016.08.004

Roberts, I., Shakur, H., Coats, T., Hunt, B., Balogun, E., Barnetson, L., et al. (2013). The CRASH-2 trial: a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of the effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events and transfusion requirement in bleeding trauma patients. Health Technol. Assess. 17, 1–79. doi:10.3310/hta17100

Rowell, S. E., Meier, E. N., McKnight, B., Kannas, D., May, S., Sheehan, K., et al. (2020). Effect of out-of-hospital tranexamic acid vs placebo on 6-Month functional neurologic outcomes in patients with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. JAMA. 324, 961–974. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8958

Rundhaug, N. P., Moen, K. G., Skandsen, T., Schirmer-Mikalsen, K., Lund, S. B., Hara, S., et al. (2015). Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: effect of blood alcohol concentration on Glasgow coma scale score and relation to computed tomography findings. JNS. 122, 211–218. doi:10.3171/2014.9.JNS14322

Safari, H., Farrahi, P., Rasras, S., Marandi, H. J., and Zeinali, M. (2020). Effect of intravenous tranexamic acid on intracerebral brain hemorrhage in traumatic brain injury. Turk. Neurosurg. 31, 223–227. doi:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.30774-20.4

Shiraishi, A., Kushimoto, S., Otomo, Y., Matsui, H., Hagiwara, A., Murata, K., et al. (2017). Effectiveness of early administration of tranexamic acid in patients with severe trauma. Br. J. Surg. 104, 710–717. doi:10.1002/bjs.10497

Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., et al. (2016). ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. i4919, i4919. doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., et al. (2019). RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. l4898, l4898. doi:10.1136/bmj.l4898

Taylor, C. A., Bell, J. M., Breiding, M. J., and Xu, L. (2017). Traumatic brain injury–related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths — united States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 66, 1–16. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1

Valle, E. J., Allen, C. J., Van Haren, R. M., Jouria, J. M., Li, H., Livingstone, A. S., et al. (2014). Do all trauma patients benefit from tranexamic acid? J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 76, 1373–1378. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000000242

Van Wessem, K. J. P., Jochems, D., and Leenen, L. P. H. (2022). The effect of prehospital tranexamic acid on outcome in polytrauma patients with associated severe brain injury. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 48, 1589–1599. doi:10.1007/s00068-021-01827-5

Walker, P. F., Bozzay, J. D., Johnston, L. R., Elster, E. A., Rodriguez, C. J., and Bradley, M. J. (2020). Outcomes of tranexamic acid administration in military trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage: a cohort study. BMC Emerg. Med. 20, 39. doi:10.1186/s12873-020-00335-w

Wang, K., and Santiago, R. (2022). Tranexamic acid – a narrative review for the emergency medicine clinician. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 56, 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.027

Weng, S., Wang, W., Wei, Q., Lan, H., Su, J., and Xu, Y. (2019). Effect of tranexamic acid in patients with traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 123, 128–135. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.214

Yutthakasemsunt, S., Kittiwatanagul, W., Piyavechvirat, P., Thinkamrop, B., Phuenpathom, N., and Lumbiganon, P. (2013). Tranexamic acid for patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Emerg. Med. 13, 20. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-13-20

Keywords: tranexamic acid, acute brain injury, mortality, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Bian W, Qi M, Ding L, Lu Y, Yan K, Wang Z, Zhang J and Zhou P (2025) Is tranexamic acid effective for all traumatic brain injury patients? a severity based systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1677936. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1677936

Received: 01 August 2025; Accepted: 18 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Giuseppe Di Giovanni, University of Magna Graecia, ItalyReviewed by:

Vikas Bansal, Mayo Clinic, United StatesGuangdong Wang, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2025 Bian, Qi, Ding, Lu, Yan, Wang, Zhang and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ping Zhou, enBfMzE5QDE2My5jb20=; Wentao Bian, Ymlhbnd0Mzc3NkAxNjMuY29t; Jiancheng Zhang, MTcwMTYzNTVAcXEuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Wentao Bian

Wentao Bian Mengxia Qi2†

Mengxia Qi2† Ping Zhou

Ping Zhou