- 1CAS Key Laboratory of Geospace Environment, Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China

- 2CAS Center for Excellence in Comparative Planetology, Hefei, China

Prominence bubbles are cavities rising into quiescent prominences from below. The bubble-prominence interface is often the active location for the formation of plumes, which flow turbulently into quiescent prominences. Not only the origin of prominence bubbles is poorly understood, but most of their physical characteristics are still largely unknown. Here, we investigate the dynamical properties of a bubble, which is observed since its early emergence beneath the spine of a quiescent prominence on 20 October 2017 in the Hα line-center and in ±0.4 Å line-wing wavelengths by the 1-m New Vacuum Solar Telescope. We report the prominence bubble to be exhibiting a disparate morphology in the Hα line-center compared to its line-wings' images, indicating a complex pattern of mass motion along the line-of-sight. Combining Doppler maps with flow maps in the plane of sky derived from a Nonlinear Affine Velocity Estimator, we obtained a comprehensive picture of mass motions revealing a counter-clockwise rotation inside the bubble; with blue-shifted material flowing upward and red-shifted material flowing downward. This sequence of mass motions is interpreted to be either outlining a kinked flux rope configuration of the prominence bubble or providing observational evidence of the internal kink instability in the prominence plasma.

1. Introduction

It is crucial to understand the dynamical characteristics and magnetic field configuration of the solar prominences primarily due to their association with the solar eruptions. Prominences are believed to be a visible manifestation of the cool material suspended in the corona on the dips of the nearly horizontal magnetic field lines spanned across the polarity inversion line [1–3]. Although a long-term observational history of solar filaments enabled the general characterization of its formation and evolution [4–6], high-resolution observations unveiled obscure features, for example, the prominence bubbles. Bubbles are observed as a void region located just above the spicule height emerging underneath the quiescent prominences [7, 8]. Bubbles are known to be the active locations for the formation of “plumes” which are a probable source of mass supply into the prominence [9] countering the observed drainage of the prominence material due to the gravitation pull. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the physical mechanisms responsible for the formation, uprise, and expansion of the bubbles.

It is unclear what is inside the prominence bubble. Is it a void region or filled with low-density cool plasma? The earliest observation of the prominence bubble in Ca 8542 Å spectra [7] revealed the absence of line emission in the bubble to be due to its absorption by the cool plasma, and not due to the “off-band effect” of the filter. Heinzel et al. [10] compared the EUV and X-ray intensities observed from prominence with the bubble, determining the opacity of the bubble (and hence the hydrogen column density) to be approximately one-sixth of that of the prominence. Similarly, Labrosse et al. [11] obtained the intensity of the coronal Fe xii line in the bubble to be larger than that in the prominence, however lower than the corona. They speculated the absorption to be due to the optically thin prominence plasma which, however, is not clearly visible in the Hα images. Berger et al. [8] determined the temperature of the plasma inside the bubble to be ranging between 2.5–12 × 105 kelvin, and that it is 25–120 times hotter than the surrounding prominence material. Of particular interest was the observation of a hot rising structure (logT≈6.0) within a prominence bubble investigated in Berger et al. [8], which was argued to play a crucial role in the formation and expansion of the bubble through pushing the cooler prominence material upwards. They further inferred “magneto-thermal convection” process to be responsible for the expansion of the prominence bubble. Similarly, Shen et al. [12] also found higher temperature inside the bubble (< T >= 6.83MK) compared to the surrounding prominence material (< T >= 5.53MK). On the other hand, Dudík et al. [13] rejected the presence of any kind of hot material inside the bubble based on the investigation of a prominence bubble in the EUV 193 Å wavelength. Further, the emission inside the prominence bubble and the prominence cavity region was found to be of similar magnitude. In agreement to this, Gunár et al. [14] interpreted the apparent brightening in the bubble region (particularly in the 171 Å images) to be due to the material corresponding to the prominence-corona-transition-region (PCTR) in the foreground or the background of the bubble based on the observational evidence that the bubble appeared as a void region in Hα images but not distinctly separable in the contemporaneous optically thick EUV 304 Å images. Therefore, it is evident that the consensus on the composition of the bubble interior is yet to be reached.

Highly structured ambient and background magnetic field on the top of low emitting bubbles makes it very difficult to determine the magnetic field strength and configuration of the prominence bubble. Dudík et al. [13] modeled prominence bubble through the inclusion of an emerging parasitic bipole beneath the prominence where the arcade field lines of the bipole correspond to the boundary of the bubble. They further argued that bubbles are devoid of any material and just the “gaps or windows" in the prominence due to the absence of dips in the bubble field lines. Moreover, the reconnection between the arcade field lines of the bubble and that of the overlying prominence may explain the generation of plumes. Shen et al. [12] interpreted the enhanced temperature inside the investigated bubble using the aforesaid scheme of reconnection. The magnetic field strength of two different prominence bubbles estimated using the THEMIS/MTR polarimetric observations revealed a higher magnetic field inside the bubble compared to the prominence [15], which is indicative of emerging magnetic flux at the location of the prominence bubble. Observational evidences of flux emergence beneath the prominence can be found in Chae et al. [16]. Based on these observations, the role of Lorentz force has been proposed to explain the emergence and uprise of the prominence bubbles.

Quiescent prominences exhibit irregular motion persistently over the entire structure which is generally attributed to the fundamental plasma instabilities. Ryutova et al. [17] investigated several cases of prominence with bubbles and plumes and suggested the presence of both the Kelvin–Helmholtz (K–H) and Rayleigh–Taylor (R–T) instabilities. K–H instability is attributed to driving the ripples (perturbations) at the bubble boundary to form a single large plume whereas self-similar multiple plumes are suggested to be due to the R–T instability. Further, they characterized the bubble to be a “growing coronal cavity” underneath the prominence and suggested the screw-pinch instability [18] to be the formation mechanism of the bubble. K-H instability is one among the most commonly observed instabilities [19] and occurs at the surface of discontinuity of the two fluids which propagate with different speeds, however, possess sufficient enough shear so as to overcome the surface tension force. Berger et al. [20] attributed the coupled KH–RT instability to be responsible for the development and growth of ripples at the boundary of a prominence bubble as they were located at the density inversion layer. Similarly, Mishra and Srivastava [21] found the magnetic R-T (MRT) instability to drive regular formation and development of plumes originating from small-scale cavities developed within the prominence whereas the collapse of a plume was attributed to K-H instability. Thus, probing the dynamical behavior of the prominence material leads to the identification of associated plasma instabilities, and in turn, offers insights into the physics of formation and stability of the quiescent prominence.

Therefore, it is evident that the physics of the formation and evolution of prominence bubbles is still debated. Thanks to high spatial-resolution Hα images of a prominence recorded by New Vacuum Solar Telescope (NVST), we distinctly characterize the mass motions within a prominence bubble (section 3) in this work. A crucial finding of our analysis is the presence of disparate mass distribution within the bubble in the co-temporal Hα line-center and in line-wing images. An interesting feature in the EUV observations of the prominence is the presence of a “bright compact region” within the bubble. The morphological and thermodynamical evolution of the blob is made to discuss its origin in the context of bubble or from PCTR. Finally, Doppler analysis from the Hα line-wing observations is employed to infer the magnetic skeleton of the prominence bubble in section 4.

2. Instruments and Data

In order to investigate the mass motion in a quiescent prominence, we primarily use the images acquired by a ground-based 1-m New Vacuum Solar Telescope (NVST; [22]) in the Hα line center and in ±0.4 Å wings, during 07:27–09:28 UT. NVST raw data-set has been further subjected to the alignment as well as speckle reconstruction, resulting in the pixel scale and the temporal cadence of the final Hα images to be 0″.136 and 28 s, respectively. While the NVST field-of-view could only capture the southern section of the prominence (Figures 1a–c), the full context of the prominence has been obtained using full-disk extreme ultra-violet (EUV) images in the 211, 171, and 193 Å wavelengths, recorded by the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA; [23]) onboard Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO; [24]) with a pixel scale of 0″.6 and a temporal cadence of 12 s. Full-disk Hα images acquired by the Kanzelhöhe Solar Observatory (KSO) and Global Oscillation Network Group (GONG) with the pixel scale of 1″ have also been utilized to study the long-term evolution of the prominence.

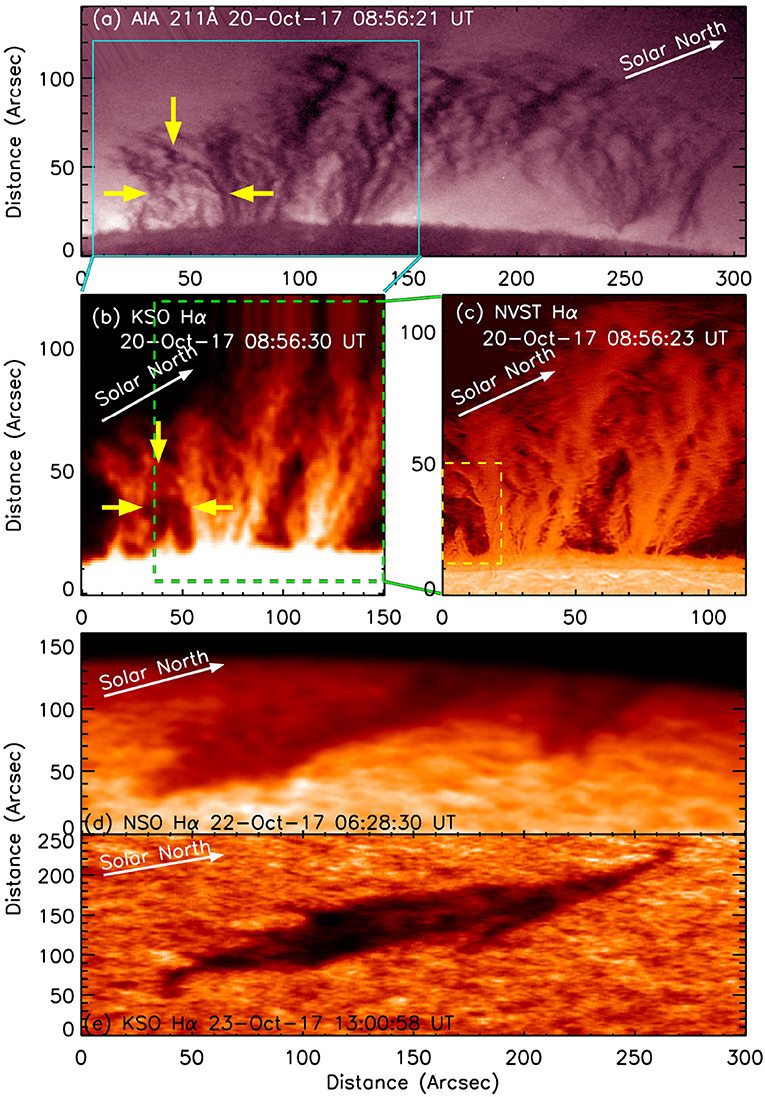

Figure 1. Multi-wavelength overview of the quiescent prominence, located at the northeast limb of the solar disk on October 20, 2017 (N24E87). All the images have been rotated clockwise by 65° for presenting an upright view of the prominence. (a) AIA 211 Å image showing the entire prominence spanning across approximately 250" on the limb. The Cyan rectangle represents the field of view of the Hα image acquired by the Kanzelhoehe Solar Observatory (KSO), shown in (b). The green square region in (b) indicates the field-of-view of the Hα image recorded by NVST, shown in panel (c). Prominence bubble, investigated in this paper is outlined in yellow in (a–c). (d,e) Prominence as observed on 22 and 23 October 2017 from the National Solar Observatory (NSO) and KSO, respectively. It is clear that the prominence morphology has not altered significantly.

3. Observational Results

We investigate the mass motion in a quiescent prominence of October 20, 2017, located at the north-east limb of the solar disk (N24E87). In particular, dynamical characteristics intrinsic to a prominence bubble (marked by yellow arrows in the of Figures 1a–c), that is situated beneath the spine of the prominence, have been investigated. The bubble is seen in the form of a dark cavity in the Hα line center whereas the same appears bright surrounded by dark threads in the EUV observations. From the NVST Hα images, it is evident that the cavity region has a distinctively sharp boundary (Figure 1c), a typical feature attributed to the prominence bubbles. Further, the bubble interior is composed of fine structures and appears to be filled partially with the material of relatively lesser brightness than the prominence itself. The prominence structure corresponds to a typical “hedgerow" shape, suggesting that the prominence main body spans obliquely with respect to the line-of-sight [17]. This can be further confirmed by the Hα images of the prominence acquired on the subsequent days where the prominence is visible in absorption against the bright disk and spans along the north-south direction (Figures 1d,e). Such configuration allows a clear view of the prominence material as the effect of the sky-plane projection of the background and foreground activities remain minimal [25]. As follows we characterize the small-scale mass motion within the prominence bubble.

3.1. Morphological Evolution of the Prominence Bubble in Hα

The evolutionary sequence of the prominence bubble since its formation has been investigated using the NVST Hα line-center and line-wing images (Figure 2 and available online as Supplementary Movie). Prominence bubble originated in the form of an ellipse-shaped void with its major axis having the span of ~13" (~9 Mm) and acutely tilted toward the solar limb (Figure 2a). After 90 minutes of evolution, the bubble enlarged [~35" (25 Mm)] and became more vertically arranged (Figure 2k). Several interesting features have been identified in the bubble interior and at the boundary in the course of its evolution, discussed as follows and in the section 3.3.

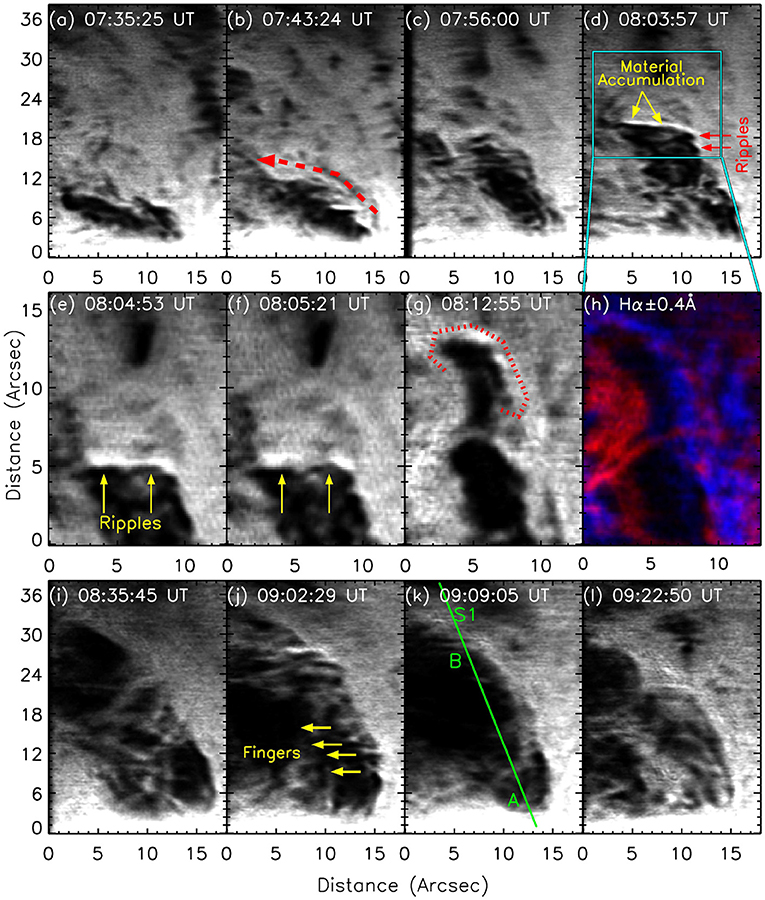

Figure 2. Dynamical evolution of a prominence bubble since its formation as seen in the Hα line-center and line-wing image sequence, acquired by NVST telescope. Crucial dynamical activities exhibited by the material flowing in the bubble interior and at the boundary include; anti-clockwise shear flow at the bubble boundary (a–b), brightened section of the bubble boundary indicating the plasma accumulation as bubble uplifts (c–d); rippling boundary followed by the generation of a mushroom-head plume (e–g in Hα line-center). Hα line-wing images of the plume show dissimilar line-of-sight flow pattern across the rising plume which comprises of blue-shifted material at the head of the plume while red-shifted material is predominant at its left leg (h). A clear instance of the formation of finger-shaped structures, extending out from the right boundary of the bubble, is shown in (j). Constantly altering mass distribution in the bubble interior (i–l) is indicative of the highly dynamical nature of the investigated bubble. (A movie covering the entire evolutionary sequence of the bubble in the Hα line-center as well as in the line-wings, and in various EUV wavelengths is made available online as a Supplementary Material).

Since the bubble formation, counter-clockwise shear flows are persistently observed along its boundary (Figure 2b). Further, as the bubble uplifts, its visually topmost boundary exhibits excess in emission compared to the prominence brightness (Figure 2d). This manifests the accumulation of ambient prominence material on the bubble boundary during its uprising process [17].

3.2. Doppler Map and Flow Field in the Prominence Bubble

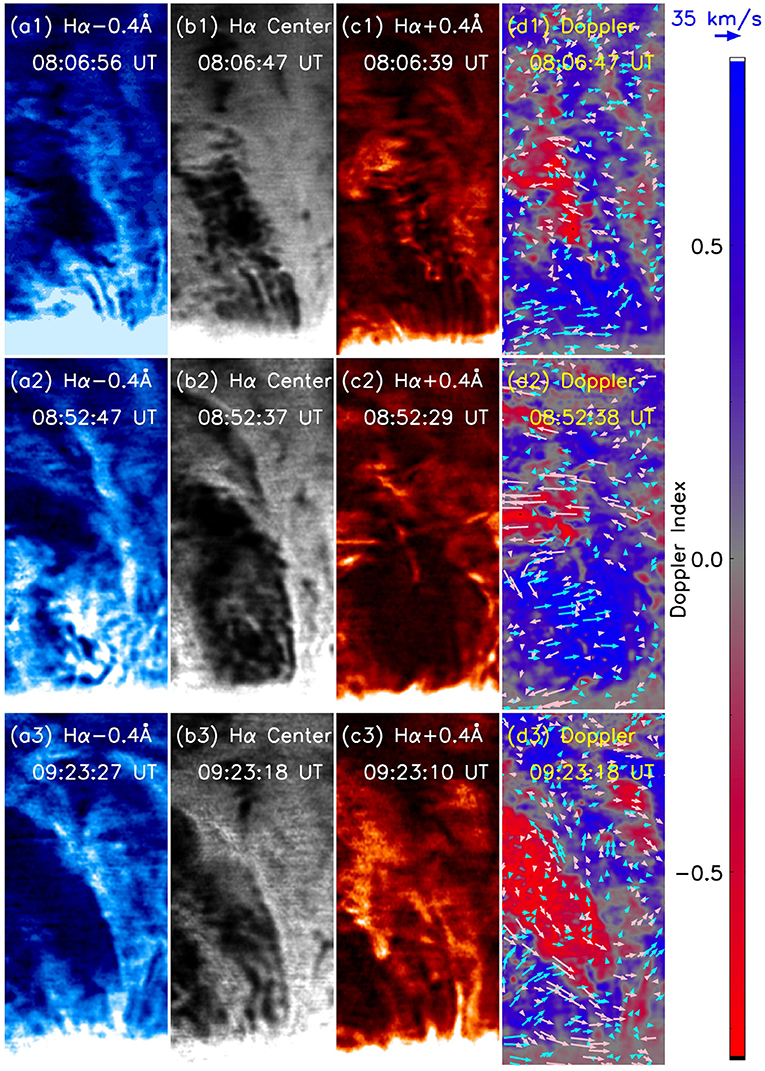

We investigate the dynamical characteristics of the prominence material by analyzing the images acquired by NVST in the Hα line center as well as in the Hα±0.4 Å wings. It is interesting to note that mass distribution in the bubble interior as seen in the Hα line-center images differs remarkably from that appearing in the respective Hα blue and red wing images (Figure 3). For instance, while the prominence bubble is imaged in the form of a cavity in the Hα line-center wavelength at 08:52:37 UT (Figure 3b2), the co-temporal Hα line-wing images (Figures 3a2,c2) indicate that the mass motion inside the bubble along the line-of-sight (LOS) has a complex pattern. Therefore, multi-wavelength observations are crucial in making a comprehensive assessment of the dynamical characteristics of prominence bubbles, as conducted in the present study.

Figure 3. Bubble dynamics quantified using the flow maps derived using NAVE procedure and Doppler maps. A sequence of images in the Hα-0.4 Å, Hα line-center, and Hα+0.4 Å are shown in the first three columns (a–c), respectively. (d1–d3) The flow map derived from the Hα blue- and red-wing images is plotted in cyan and pink, respectively, on the respective Doppler maps. The blue (red) color in the doppler map represents the mass motion toward (away from) the line-of-sight. The LOS refers to the direction pointing away and orthogonal to the image plane.

In order to quantify the mass motion inside the bubble as well as on its boundaries, we employ the nonlinear affine velocity estimator (NAVE) technique [26] to derive the flow-map from the NVST images acquired in the Hα line-center, blue and red-wing wavelengths. The flow-map has been derived over a grid of uniform spacing of 5 pixels (~0.5 Mm) and 50 × 65 pixels span. The continuity equation, a default solver in the NAVE procedure, is used for an FWHM of 30 pixels. An important input to the NAVE procedure is the noise level, which is determined using the relationship , where σd is determined as the standard deviation of the absolute difference of two consecutive images corresponding to a region enclosing a quiet and dark area above the prominence. In parallel, in order to deduce plasma motion along the LOS, doppler maps have been constructed using the following relationship [27].

where B and R refer to the pixel intensities in the Hα blue and red-wing images, respectively.

The overlay of flow maps, derived using the Hα line-wing images [pink (cyan) vectors in Figures 3d1–d3 corresponds to the red (blue) wing of the Hα line profile], onto the co-temporal doppler maps [background images in the (Figures 3d1–d3) with the blue (red) color representing the positive (negative) doppler index] revealed the material inside the bubble to be rotating in a counter-clockwise sense. It is further observed that the red-shifted material is predominately exhibiting a downflow (toward the solar disk), whereas a definitive trend of upward motion was seen in the blue-shifted material (Figure 3d3). The rotational motion remained persistent during the entire period of investigation (07:27–09:27 UT), however with a varying speed ranging between 5 and 38 km/s. The flow of the red-shifted material has been mainly constrained either at the top of the bubble or at its left side. Similarly, the blue-shifted material appears to be flowing predominately at the bottom or at the right side of the bubble (directions correspond to the vertically upright view of the bubble as a reference, see Figure 3).

3.3. Plasma Instabilities in the Prominence Bubble

Mass motion inside the bubble and along its boundary reveals several interesting features associated with the plasma instabilities. For instance, at least two distinctively clear small-amplitude (0.5 Mm) ripples are observed at the right boundary of the bubble (shown by red arrows in Figure 2d). Subsequently, the top boundary of the bubble also exhibits a clear signature of rippling motions (Figure 2e). While there is no significant increase in the amplitude of the rippling motion until the image acquired at 08:05:21 UT (Figure 2f), the perturbations increased significantly later, leading to the generation of a typical mushroom-head plume (Figure 2g). Interestingly, only a single episode of the plume generation (average uplift speed ~13 km/s) was observed. This indicates the nonlinear explosive phase of the K–H instability to be the most possible mechanism for the investigated plume [17]. To further understand, we have derived the growth rate of explosive instability using Equation (2) [17] for our case of plume evolution.

where the parameter α is considered equal to unity. is the rate of inverse slowing down of the particles due to electron-ion collision. Considering the temperature and density of the particles to be 1 MK and 5 × 1010 cm−3, respectively, takes a value of 2.7 × 10−2 s−1. It has been further shown in Ryutova et al. [17] that the ratio of energy increased (|W|/|W0|) can be approximated to the ratio of the square of the initial and final perturbation amplitudes, which are determined to be 0.5" and 4.5", respectively, in our case (cf. Figures 2f,g). With the aforesaid values and equation 2, the rate of growth of the explosive instability is determined to be 9.34 × 10−3 s−1, similar to that deduced in Ryutova et al. [17]. Another possible mechanism for the plume generation can be the coupled KH–RT instability [20], however limited spatial resolution restricts the definitive determination of the growth rate of the ripples in their pre-explosive evolution phase (on or before 08:05:21 UT; see Figures 2e–f) which makes it difficult to test this scenario. Hα line-wing images (±0.4 Å) of the plume reveal the blue-shifted emission to be dominant at the plume head whereas the red-shifted material prevails along its left trail (Figures 2i–l). This is a possible indication of generation of sheared flow at the plume boundary as the plume ascends.

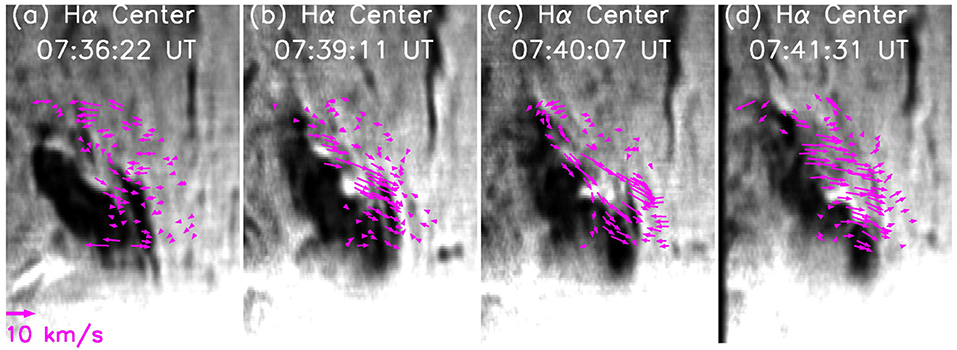

In addition to the counter-clockwise flow of material, clockwise mass motion along the right boundary of the bubble is also found at the early onset phase of the bubble evolution, particularly during 07:35–07:43 UT (Figure 4; also refer to the movie associated with the Figure 2). These oppositely directed flows may provide favorable conditions for the generation of K–H instability. Using the NAVE technique on the Hα images, we determined the flow speed along the right boundary region of the bubble to be varying in the range of 2–10 km/s, in agreement to that deduced in Berger et al. [20]. Further definitive characterization of K-H instability may be difficult here due to limited spatial resolution of the NVST images.

Figure 4. Sheared flow along bubble boundary as seen in the early evolution phase of the bubble. (a–d) Sequence of images in the Hα line-center along with the flow-map, derived using NAVE procedure, show the oppositely directed flows along the right boundary of the bubble.

Another interesting feature of the bubble evolution is the development of finger structures at the bubble boundary. One such evidently clear instance is reported in Figure 2j where the average separation between the fingers is 1.1 Mm (~1.5"). Usually, finger-like break-up structures are believed to be generated due to R–T instability taking place at the boundary of plasma layers of different densities [28]. However, since the fingers are not oriented along the direction of solar gravity, these extrusions may be the K–H vortices generated due to shearing flows.

3.4. EUV Perspective and Thermal Diagnostics of the Prominence Bubble and Bright Blob

Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) images obtained from the SDO/AIA instrument have been analyzed in order to determine the morphological and thermodynamic evolution of the prominence bubble (Figure 5). Prominence bubble interior in the 211 Å EUV image sequence (Figure 5a; also refer to the Supplementary Movie associated with the Figure 2) appears to be highly structured and dynamic in nature, similar to that observed in the Hα images.

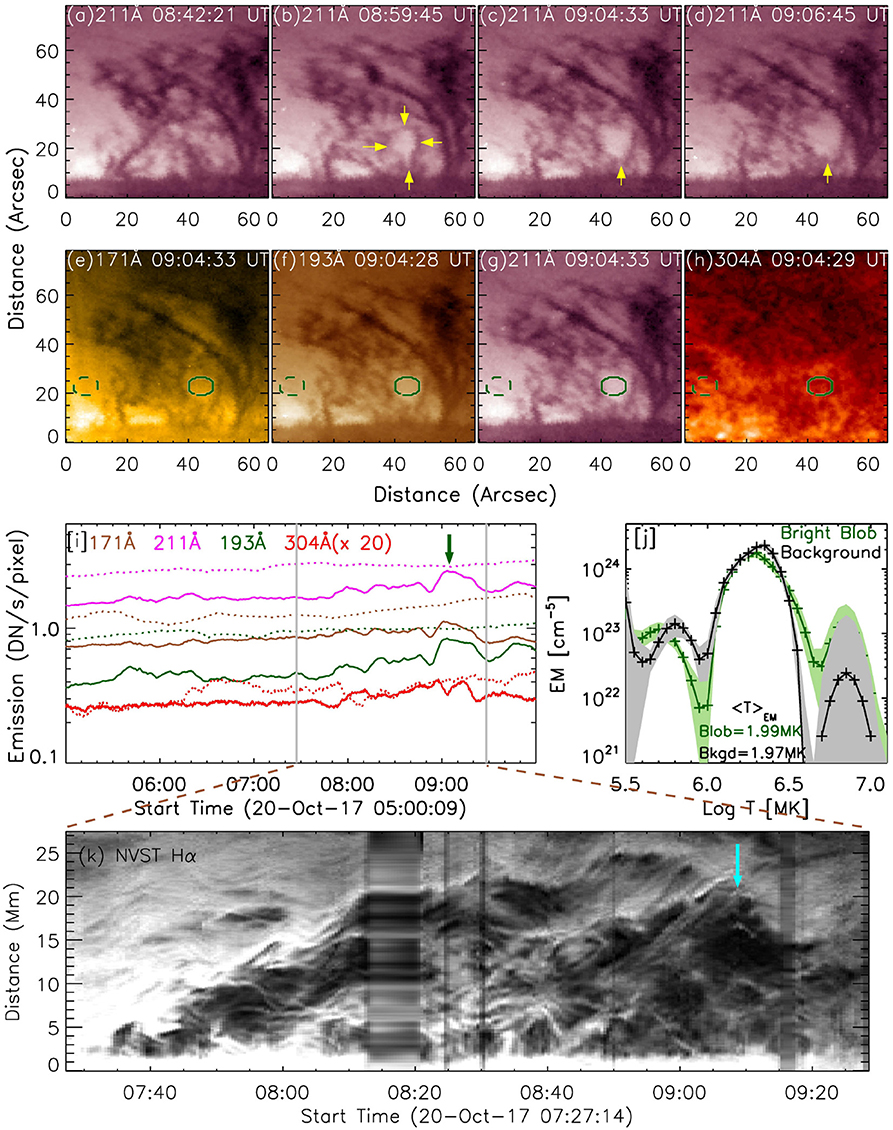

Figure 5. EUV perspective of the prominence bubble and thermodynamical evolution of a bright blob within the bubble. (a–d) Similar to the Hα observations, the bubble interior appears highly structured throughout its evolution. The formation and expansion of an interesting bright blob-like feature within the bubble, indicated by yellow color arrows in the top panel of the figure. (e–h) EUV images showing the multi-wavelength perspective of the blob at 09:04 UT. (i) Mean EUV intensity profile within a region-of-interest (ROI) representing the blob (green; full line) during 05:00 UT–10:00 UT. Background intensity evolution in respective wavelengths as derived from a ROI away from the prominence [dotted green region in panels (e–h)] is also plotted. (j) Emission measure distribution within the selected ROIs corresponding to bright blob (green) and background (black) is plotted along with the respective errors. (k) Time-distance map prepared from the Hα line-center image sequence over a virtual slit “S1” along the direction A to B (see Figure 2k).

A distinctively clear bright blob-like feature appeared inside the bubble at 08:59 UT in the EUV images (Figure 5b). The evolution of EUV emission corresponding to the bubble is quantified by taking an average of the emission from a small circular region-of-interest (ROI), selected so as to cover the change in intensity from both the bubble interior as well as the bright blob. Similarly, the respective background fluctuations are estimated by averaging the brightness of the pixels corresponding to an ROI away from the prominence, but the same in terms of geometrical parameters (area and radial distance from the limb) of the bubble ROI. The resulted EUV intensity profiles from both the bubble (full lines) and the background (dotted lines) are plotted in Figure 5i. We also prepare a time-distance map from the Hα image sequence (Figure 5k) along a virtual slit crossing the bubble (slit “S1” is shown in the Figure 2k) in order to compare the bubble evolution in the EUV and Hα wavelengths. Since the earliest formation of the bubble in Hα, a slight enhancement in the EUV emission compared to that at earlier times is evidenced. In addition to several small-scale perturbations, EUV intensity profile also exhibits a “maximum” at 09:04 UT, corresponding to the bright blob within the bubble. It is crucial to note that the EUV emission corresponding to the blob is always slightly lower than the background emission in the respective wavelengths. This is indicative of the presence of material either in the blob or along its line of sight. On the other hand, the blob appears dark in the Hα wavelengths as also seen from the time-distance images during 09:00–09:15 UT (indicated in Figure 5k).

To characterize the thermodynamical nature of the blob, we prepared emission measure (EM) maps by employing the method presented in Su et al. [29], which is a modified version of the sparse inversion technique for thermal diagnostics developed by Cheung et al. [30]. This technique makes use of the pixel intensity from the six EUV wavelengths obtained from SDO/AIA namely 94, 131, 171, 193, 211, and 335Å to derive the EM[T] distribution. We have prepared the EM maps corresponding to the temperature range 0.5–15 MK with a bin size LogT = 0.05. The evolution of emission measure derived by taking an average of the estimated EM[T] distribution over the region corresponding to the bubble and the background ROI are plotted in Figure 5j. The uncertainty is calculated using the Monte-Carlo method, implemented in the EM diagnostics technique of Su et al. [29]. We find the EM values only within the temperature range logT = 6.0–6.6 to be reliable as the derived EM for temperature values beyond this range possess very large uncertainties (Figure 5j). Therefore, we estimate the EM-weighted average temperature (< T >EM) using the Equation 3 (adopted from [31]) only within the aforesaid temperature range.

The < T >EM of the blob results to be 1.99 MK, similar to that of the background corona (1.97 MK). Therefore, this analysis remains inconclusive in untangling the thermodynamical characteristics of bright blob within the bubble from that of the foreground/background corona.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Our investigation of mass motion of a prominence targets the evolutionary phase of a bubble since its earliest appearance in the Hα and EUV observations. We find several new morphological and dynamical characteristics of the prominence bubble as discussed following.

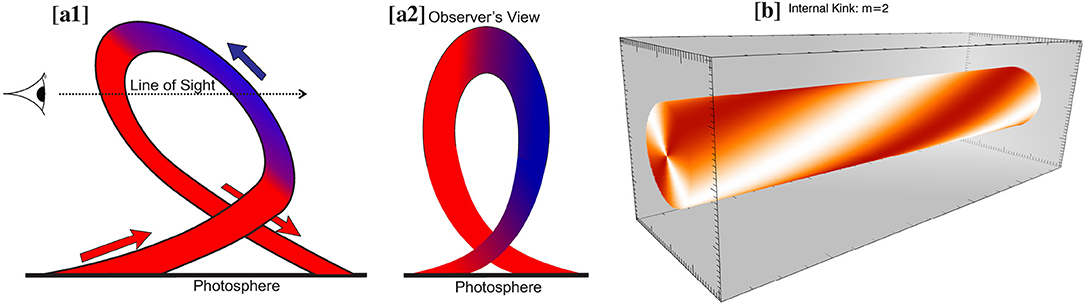

The bubble interior is observed to replete with dynamic mass (Figures 2, 3). This suggests that during the formation stage, prominence bubbles do not always possess an obvious cavity-like morphology as usually identified in the existing literature [8, 13]. Besides, we have been unable to identify any distinct morphological difference between the bubble location and ambient prominence prior to the formation of the bubble. Therefore, the formation mechanism of the bubble may not require any preferential magnetic field configuration of the pre-existing prominence. The observed disparate mass distribution in the Hα line-center compared to that in the co-temporal line-wing (±0.4 Å) images indicate a highly dynamical nature of the mass motions inside the bubble (Figure 3). To better understand, a comprehensive dynamical characteristic of the prominence bubble is derived by preparing doppler maps and flow-maps from the line-wing images. This revealed a counter-clockwise rotational motion of the material in the bubble interior, which is composed predominately of the blue-shifted material exhibiting upward flow while red-shifted material undergoes a downward flow. Doppler maps further reveal that the red-shifted material is primarily observed in the top as well as at the left portion of the bubble whereas the bottom and the right sections of the bubble are filled with the blue-shifted material (Figures 3d1–d3). We interpret this sequence of mass motion to be outlining a kinked flux rope configuration of the magnetic field inside the prominence bubble (Figures 6a1,a2). Liu et al. [32] obtained a similar doppler-shift pattern in a pre-eruptive active-region prominence and inferred it as the signature of a kink-unstable configuration. This concurs with the hypothesis of an emerging flux complex to be the magnetic field structure of the prominence bubble, conceived in Berger et al. [20].

Figure 6. Inferences on the magnetic structure of the prominence bubble as revealed by mass motions. (a1,a2) Schematic representation of a kinked flux-rope as the magnetic field configuration of the bubble, drawn from two perspectives. Material flowing toward (away from) the observer is denoted in blue (red) color. (b) Internal kink instability in a cylindrical flux-rope corresponding to mode (m) = 2.

Internal kink instability [33–35] can provide an alternate interpretation of the dynamical characteristics exhibited by the prominence bubble investigated in this work. From the counter-streaming mass motions [36] in a magnetic field configuration which is resulted from the internal kink instability with higher mode values (m≥2) ([37]; refer to Figure 6b), it is possible to envisage a similar Doppler pattern that is shown by the prominence bubble (Figures 3d1–d3). Mei et al. [38] performed isothermal numerical magneto-hydrodynamic (MHD) simulations in a finite plasma-β environment to parameterize the role of internal and external kink instabilities in a magnetic flux rope (MFR). They found both kinds of instabilities to be competing to drive a complex evolution of MFR through the process of reconnection within and around the MFR. However, since the internal kinks are known to possess a smaller growth rate and tend to be energetically benign, which may explain the absence of any obvious signs of heating within the bubble, it can be a preferred mechanism compared to the external kink in the case of prominence bubbles. Further, internal kinks are local and confined in nature, hence their impact on the external field is limited which can help the bubbles in maintaining their shape and boundary for a longer period of time.

Since the earliest appearance of the bubble, we find the signatures of rapid rotational motion within the bubble with a speed much faster relative to the intrinsic motions exhibited by the prominence material. These flows are found to be present within the bubble (Figure 2) as well as along its boundary (Figure 4) and can be characterized as shear flows [20]. During the uprise and expansion phase of the bubble, prominence material gets accumulated on the boundary of the bubble. When the shear flow interacts with these dense bubble boundaries, ripples of 0.5–1 Mm amplitude are generated. The amplitude of the ripples rapidly increases in time, leading to generating a large typical mushroom-headed plume. While the ripples are understood to be the signatures of linear phase of instability, its rapid growth rate leading to the generation of a plume is attributed to the non-linear explosive stage of K–H instability [17]. In addition, finger-shaped structures are also observed on the bubble boundary. Although such structures are generally associated with the R–T instability [28], we believe that these extrusions may be the K–H vortices as the fingers are not oriented along the direction of solar gravity. Therefore, the generation of K–H instability can be understood as the intrinsic dynamical characteristic of the prominence bubble during its evolution and expansion.

In order to probe the signatures of heating within the bubble, we estimate the EUV emission originating within the bubble region. During the bubble expansion, slight increase in the EUV emission is found inside the bubble (particularly in the 171, 193, 211, and 304Å wavelengths), but the peak emission in the respective wavelengths has always remained lower than that resulting from the background corona (Figure 5i). An in-depth investigation further revealed an interesting episode of the formation of a localized blob within the bubble, which appears bright in all of the aforementioned EUV wavelength channels. Similar EUV emission characteristics have been exhibited by a compact region within the prominence bubble investigated in Berger et al. [39], who derived its temperature to be of the order of 1 MK. In agreement, the EM-weighted mean temperature of the blob in our case is derived to be~1.99 MK. However, since ambient corona is also estimated to have similar temperature as that of the blob, it is difficult to infer whether the emission corresponds to the “hot compact region” within the bubble [39] or from the foreground/background prominence-corona-transition-region (PCTR) [14]. Intriguingly, the blob is observed to push the material toward the bubble boundaries during the course of its evolution, which appears to result in the upward expansion of the bubble.

To conclude, high-resolution observation of the prominence not only offers insights into its magnetic field configuration, but it also provides a platform to characterize the generation and growth of the instabilities in the magnetohydrodynamic fluids. Intrinsic mass motions in the prominence (not necessarily leading to its eruption) are an outstanding indirect probe of the physical conditions, as demonstrated in this study where they outline a kinked flux rope configuration of the prominence bubble or provide a new observational signature of the internal kink instability in the prominence. This work also provides physical constraints in the form of morphological characteristics, growth rate, and thermodynamical characteristics of the bubble, which can be used to drive realistic numerical simulations.

Data Availability Statement

Hα observations from NVST, analyzed in this work, can be requested through the URL http://fso.ynao.ac.cn/datashow.aspx?id=1782. Data from SDO and GONG Hα network are archived at the respective instruments' URLs and freely available for download.

Author Contributions

AA conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript under the guidance of RL. RL led the interpretation of the results.

Funding

AA acknowledges the support from the Chinese Academy of Science (CAS) as well as the International Postdoctoral Program of the University of Science and Technology of China. RL acknowledges the support from NSFC 41474151, 41774150, and 41761134088.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This investigation primarily made use of the data acquired from the New Vacuum Solar Telescope under a guest observation program. NVST is operated by the Yunnan Astronomical Observatory, Kunming, China. AA acknowledges the hospitality offered by the staff of Fuxian Lake Solar Observatory during his stay for the observing period and for carrying out the post-processing of the raw data in terms of the alignment and application of speckle-reconstruction technique. RL thank Prof. Jongchul Chae for providing the NAVE code. Dr. Yang Su and Dr. Mark Cheung are acknowledged for the code used to derive the thermodynamical properties of the plasma bubble from the EUV images. Authors also acknowledge the reviewers for their constructive comments which improved the scientific clarity of the work.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphy.2019.00218/full#supplementary-material

Associated with Figure 2, a supplementary movie covering the entire evolutionary sequence of the bubble in the Hα line-center as well as in the line-wings, and in various EUV wavelengths is made available online.

References

1. Leroy JL, Bommier V, Sahal-Brechot S. New data on the magnetic structure of quiescent prominences. Astron Astrophys. (1984) 131:33–44.

2. Aulanier G, DeVore CR, Antiochos SK. Prominence magnetic dips in three-dimensional sheared arcades. Astrophys J Lett. (2002) 567:L97–101. doi: 10.1086/339436

3. Ariste AL. Magnetometry of prominences. In: Vial JC, Engvold O, Editors. Solar Prominences. Astrophysics and Space Science Library, Vol. 415. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2015). p. 179–203. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10416-4_8

4. Martin SF, Echols CR. An Observational and Conceptual Model of the Magnetic Field of a Filament. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands (1994). p. 339–346.

5. Mackay DH, Karpen JT, Ballester JL, Schmieder B, Aulanier G. Physics of solar prominences: II magnetic structure and dynamics. Space Sci Rev. (2010) 151:333–99. doi: 10.1007/s11214-010-9628-0

6. Parenti S. Solar prominences: observations. Liv Rev Solar Phys. (2014) 11:1. doi: 10.12942/lrsp-2014-1

7. Stellmacher G, Wiehr E. Observatino of an instability in a “Quiescent” prominence. Astron Astrophys. (1973) 24:321.

8. Berger TE, Liu W, Low BC. SDO/AIA detection of solar prominence formation within a coronal cavity. Astrophys J Lett. (2012) 758:L37. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/758/2/L37

9. Berger TE, Shine RA, Slater GL, Tarbell TD, Title AM, Okamoto TJ, et al. Hinode SOT observations of solar quiescent prominence dynamics. Astrophys J Lett. (2008) 676:L89. doi: 10.1086/587171

10. Heinzel P, Schmieder B, Fárník F, Schwartz P, Labrosse N, Kotrč P, et al. Hinode, TRACE, SOHO, and Ground-based Observations of a Quiescent Prominence. Astrophys J. (2008) 686:1383–96. doi: 10.1086/591018

11. Labrosse N, Schmieder B, Heinzel P, Watanabe T. EUV lines observed with EIS/Hinode in a solar prominence. Astron Astrophys. (2011) 531:A69. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015064

12. Shen Y, Liu Y, Liu YD, Chen PF, Su J, Xu Z, et al. Fine magnetic structure and origin of counter-streaming mass flows in a quiescent solar prominence. Astrophys J Lett. (2015) 814:L17. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/814/1/L17

13. Dudík J, Aulanier G, Schmieder B, Zapiór M, Heinzel P. Magnetic Topology of Bubbles in Quiescent Prominences. Astrophys J. (2012) 761:9. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/761/1/9

14. Gunár S, Schwartz P, Dudík J, Schmieder B, Heinzel P, Jurčák J. Magnetic field and radiative transfer modelling of a quiescent prominence. Astron Astrophys. (2014) 567:A123. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322777

15. Levens PJ, Schmieder B, López Ariste A, Labrosse N, Dalmasse K, Gelly B. Magnetic field in atypical prominence structures: bubble, tornado, and eruption. Astrophys J. (2016) 826:164. doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/826/2/164

16. Chae J, Martin SF, Yun HS, Kim J, Lee S, Goode PR, et al. Small magnetic bipoles emerging in a filament channel. Astrophys J. (2001) 548:497–507. doi: 10.1086/318661

17. Ryutova M, Berger T, Frank Z, Tarbell T, Title A. Observation of plasma instabilities in quiescent prominences. Solar Phys. (2010) 267:75–94. doi: 10.1007/s11207-010-9638-9

18. Sakurai T. Magnetohydrodynamic interpretation of the motion of prominences. Pub Astron Soc Japan (1976) 28:177–98.

19. Zhelyazkov I, Chandra R, Srivastava AK. Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in an active region jet observed with Hinode. Astrophys Space Sci. (2016) 361:51. doi: 10.1007/s10509-015-2639-2

20. Berger T, Hillier A, Liu W. Quiescent prominence dynamics observed with the hinode solar optical telescope. II. Prominence bubble boundary layer characteristics and the onset of a coupled Kelvin-Helmholtz Rayleigh-Taylor instability. Astrophys J. (2017) 850:60. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aa95b6

21. Mishra SK, Srivastava AK. The Evolution of magnetic Rayleigh-Taylor unstable plumes and hybrid KH-RT instability into a loop-like eruptive prominence. Astrophys J. (2019) 874:57. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab06f2

22. Liu Z, Xu J, Gu BZ, Wang S, You JQ, Shen LX, et al. New vacuum solar telescope and observations with high resolution. Res Astron Astrophys. (2014) 14:705–18. doi: 10.1088/1674-4527/14/6/009

23. Lemen JR, Title AM, Akin DJ, Boerner PF, Chou C, Drake JF, et al. The Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) on the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Solar Phys. (2012) 275:17–40. doi: 10.1007/s11207-011-9776-8

24. Pesnell WD, Thompson BJ, Chamberlin PC. The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). Solar Phys. (2012) 275:3–15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3673-7-2

25. Berger TE, Slater G, Hurlburt N, Shine R, Tarbell T, Title A, et al. Quiescent prominence dynamics observed with the hinode solar optical telescope. I. Turbulent upflow plumes. Astrophys J. (2010) 716:1288–307. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/716/2/1288

26. Chae J, Sakurai T. A test of three optical flow techniques-LCT, DAVE, and NAVE. Astrophys J. (2008) 689:593–612. doi: 10.1086/592761

27. Langangen Ø, Rouppe van der Voort L, Lin Y. Measurements of plasma motions in dynamic fibrils. Astrophys J. (2008) 673:1201–8. doi: 10.1086/524057

28. Innes DE, Cameron RH, Fletcher L, Inhester B, Solanki SK. Break up of returning plasma after the 7 June 2011 filament eruption by Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities. Astron Astrophys. (2012) 540:L10. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118530

29. Su Y, Veronig AM, Hannah IG, Cheung MCM, Dennis BR, Holman GD, et al. Determination of differential emission measure from solar extreme ultraviolet images. Astrophys J. (2018) 856:L17. doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aab436

30. Cheung MCM, Boerner P, Schrijver CJ, Testa P, Chen F, Peter H, et al. Thermal diagnostics with the atmospheric imaging assembly on board the solar dynamics observatory: a validated method for differential emission measure inversions. Astrophys J. (2015) 807:143. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/807/2/143

31. Cheng X, Zhang J, Saar SH, Ding MD. Differential emission measure analysis of multiple structural components of coronal mass ejections in the inner corona. Astrophys J. (2012) 761:62. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/761/1/62

32. Liu R, Alexander D, Gilbert HR. Kink-induced Catastrophe in a Coronal Eruption. Astrophys J. (2007) 661:1260–71. doi: 10.1086/513269

33. Mikic Z, Schnack DD, van Hoven G. Dynamical evolution of twisted magnetic flux tubes. I - Equilibrium and linear stability. Astrophys J. (1990) 361:690–700.

34. Hood AW, Browning PK, van der Linden RAM. Coronal heating by magnetic reconnection in loops with zero net current. Astron Astrophys. (2009) 506:913–25. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/200912285

35. Keppens R, Guo Y, Makwana K, Mei Z, Ripperda B, Xia C, et al. Ideal MHD instabilities for coronal mass ejections. arXiv e-prints (2019) arXiv:1910.12659

36. Zirker JB, Engvold O, Martin SF. Counter-streaming gas flows in solar prominences as evidence for vertical magnetic fields. Nature. (1998) 396:440–1.

37. Cap FF. Handbook on Plasma Instabilities. Vol 1. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc. (1976). doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-159101-4.X5001-3

38. Mei ZX, Keppens R, Roussev II, Lin J. Parametric study on kink instabilities of twisted magnetic flux ropes in the solar atmosphere. Astron Astrophys. (2018) 609:A2. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201730395

Keywords: quiescent prominences, prominence: bubble, prominence: magnetic field, prominence: instability, kinked flux rope, internal kink instability

Citation: Awasthi AK and Liu R (2019) Mass Motion in a Prominence Bubble Revealing a Kinked Flux Rope Configuration. Front. Phys. 7:218. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2019.00218

Received: 30 August 2019; Accepted: 28 November 2019;

Published: 13 December 2019.

Edited by:

Xueshang Feng, National Space Science Center (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Yeon-Han Kim, Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, South KoreaXin Cheng, Nanjing University, China

Copyright © 2019 Awasthi and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arun Kumar Awasthi, arun.awasthi.87@gmail.com; Rui Liu, rliu@ustc.edu.cn

Arun Kumar Awasthi

Arun Kumar Awasthi Rui Liu

Rui Liu