- 1Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC), Doha, Qatar

- 2Research Unit Physical Activity, Sport, and Health, UR18JS01, National Observatory of Sport, Tunis, Tunisia

- 3High Institute of Sport and Physical Education, University of Sfax, Sfax, Tunisia

- 4Service of Physiology and Functional Explorations, Farhat Hached Hospital, University of Sousse, Sousse, Tunisia

- 5Research Laboratory LR12SP09 “Heart Failure”, Farhat Hached Hospital, University of Sousse, Sousse, Tunisia

- 6Laboratory of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine of Sousse, University of Sousse, Sousse, Tunisia

- 7Department of Health, Exercise Science Research Center Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

- 8Department of Psychiatry, Fattouma Bourguiba Hospital, Monastir, Tunisia

- 9Research Laboratory LR05ES10 “Vulnerability to Psychosis”, Faculty of Medicine of Monastir, Monastir, Tunisia

- 10Department of Human and Social Sciences, Higher Institute of Sport and Physical Education of Kef, University of Jendouba, Jendouba, Tunisia

- 11Department of Health Sciences (DISSAL), Postgraduate School of Public Health, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

- 12The Tunisian Center of Early Intervention in Psychosis, Department of Psychiatry “Ibn Omrane”, Razi Hospital, Manouba, Tunisia

- 13Faculty of Medicine of Tunis, Tunis El Manar University, Tunis, Tunisia

- 14Naufar Wellness & Recovery Center, Doha, Qatar

Introduction

The integration of artificial-intelligence (AI)-chatbots (AICs) into our daily routines has generated a discourse on their potential impact on cognitive health (Bai et al., 2023). AICs, which are sophisticated computer programs designed to mimic human conversation and provide automated assistance, are trained on extensive volumes of text data (Dergaa et al., 2024). This vast training allows them to understand context, nuances, and even cultural references, making their interactions more human-like (Dergaa et al., 2024). As a result, users often find themselves engaging with these chatbots in a manner that is more conversational than transactional (Dergaa et al., 2023). While search engines and platforms like Wikipedia provide users with vast amounts of information, AICs represent a significant evolution in how humans interact with technology (Adamopoulou and Moussiades, 2020). AICs are not just repositories of information; they simulate human conversation, adapt to user inputs, and can provide personalized responses (Dergaa et al., 2023). This dynamic interaction could lead to a different kind of cognitive reliance compared to static information sources. Furthermore, the immediacy and conversational nature of AICs can foster a deeper sense of trust and reliance in users, potentially influencing cognitive processes differently than traditional search engines (Adamopoulou and Moussiades, 2020). The potential for AICs to shape human cognition extends beyond mere information retrieval. It could encompass the very nature of human-computer interaction, decision-making processes, and even emotional responses. The distinction between passive consumption of information and active engagement with AICs is crucial. While both search engines and AICs provide information, the latter does so in a manner that can mimic human interaction, leading to unique cognitive implications. Beyond their conversational abilities, AICs offer a range of functionalities, including information retrieval, problem solving, and task automation.

This opinion article investigates the concept that an overreliance on AICs could potentially lead to cognitive decline [i.e., cognitive atrophy (CA)], which we labeled here as “AICs induced cognitive atrophy, AICICA.” Based on the growing concerns surrounding the potential cognitive consequences of AICICA, as discussed in the extended mind theory (EMT) and the parallels drawn with problematic Internet use (PIU), we aimed to (i) Define and clarify the concept of AICICA within the context of the EMT and its similarities to PIU; (ii) Propose the assessment of AICICA's prevalence and patterns as a future research objective (once the concept has been well-established and accepted); (iii) Suggest the exploration of long-term cognitive effects and potential causal relationships between overreliance on AICs and CA as a future research direction; and (iv) Evaluate the effectiveness of tailored interventions designed to mitigate AICICA, thereby fostering a balanced utilization of AICs within cognitive ecosystems.

Definition of cognitive atrophy and mechanisms of its induction by AICs

AICICA refers to the potential deterioration of essential cognitive abilities resulting from an overreliance on AICs. In this context, CA signifies a decline in core cognitive skills, such as critical thinking, analytical acumen, and creativity, induced by the interactive and personalized nature of AICs interactions. The concept draws parallels with the 'use it or lose it' brain development principle (Shors et al., 2012), positing that excessive dependence on AICs without concurrent cultivation of fundamental cognitive skills may lead to underutilization and subsequent loss of cognitive abilities. AICICA is particularly relevant in educational settings and/or among younger individuals who may prioritize convenient access to information over in-depth comprehension, potentially hindering the development of critical cognitive faculties. The multifaceted impact of AICs on cognitive processes, encompassing problem-solving, emotional support, and creative tasks, underscores the need for a nuanced examination of their role in shaping human cognition.

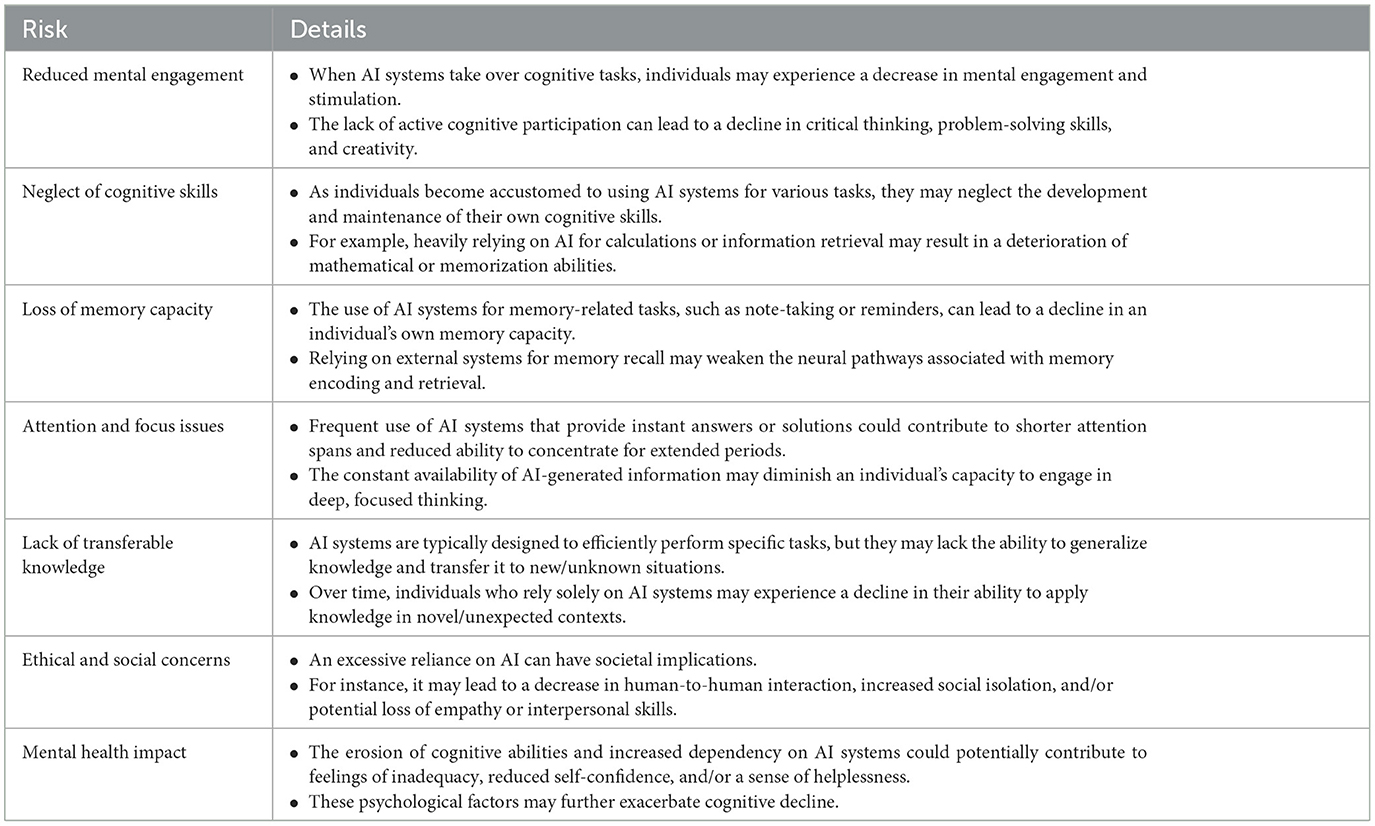

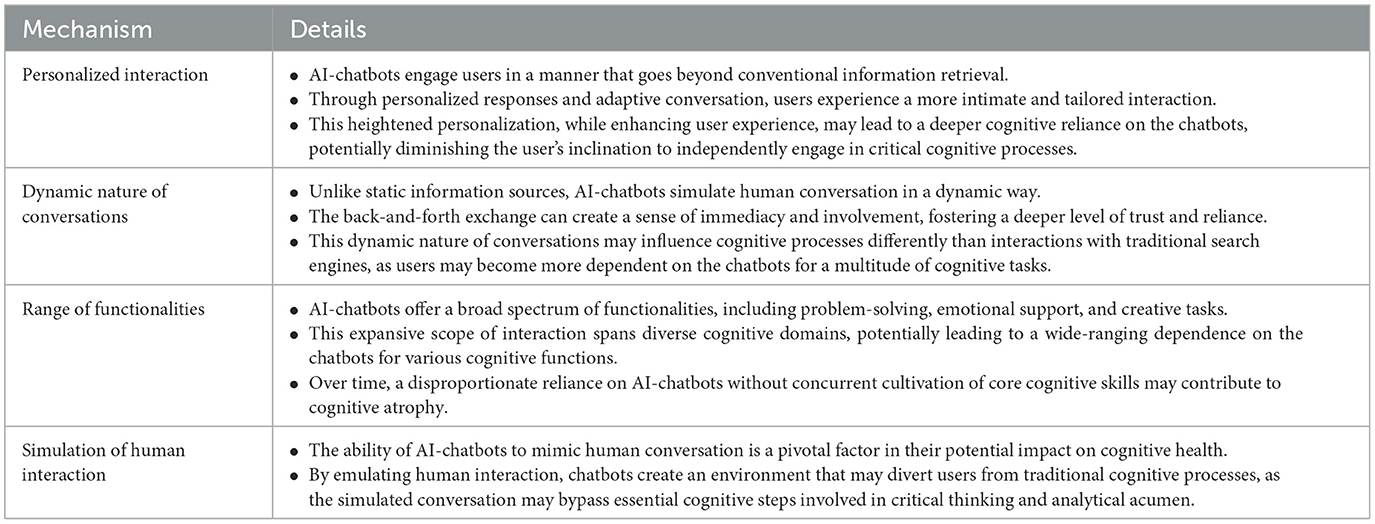

AICICA is specifically induced by AICs through their unique interactive and personalized characteristics, which distinguish them from traditional information sources. The four possible mechanisms, which elucidate how AICs could contribute to the potential CA are exposed in Table 1. In essence, AICICA is induced by the multifaceted and dynamic nature of AICs interactions, which, while offering numerous benefits, may inadvertently lead to an overreliance on the chatbots for cognitive tasks. Understanding these four induction mechanisms is crucial for assessing the potential cognitive consequences and developing strategies to mitigate AICICA.

Table 1. Mechanisms elucidating how artificial-intelligence (AI)-chatbots contribute to the potential cognitive atrophy.

Understanding the foundations of AICICA through the EMT and cognitive offloading

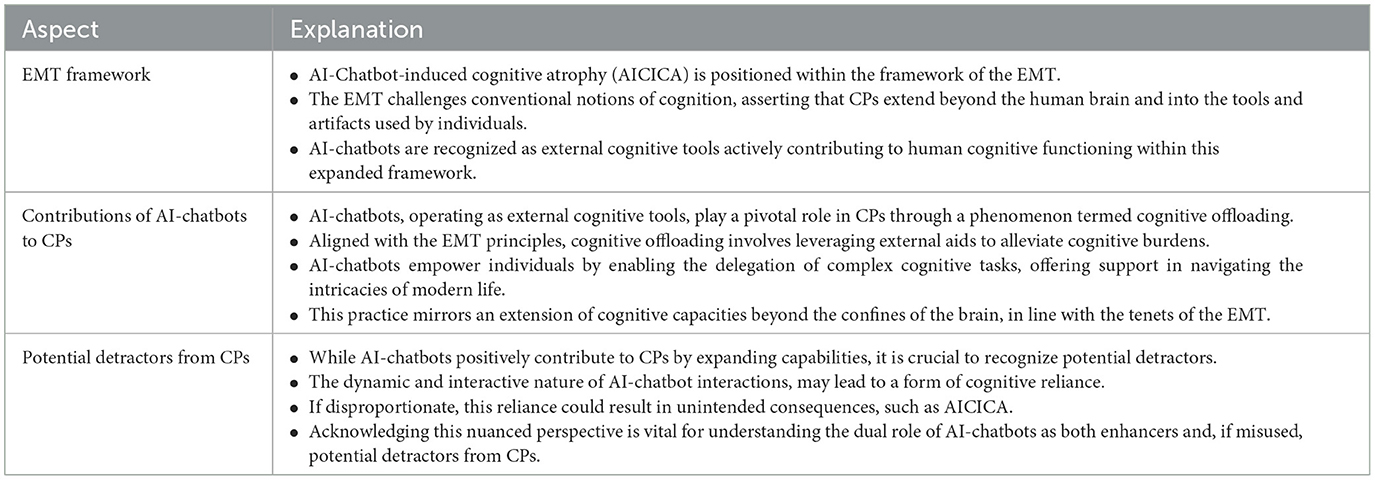

The EMT, proposed by Clark and Chalmers (1998), challenges the traditional boundaries of cognitive processes being confined within the human brain. According to the EMT, cognition extends beyond neural architecture and infiltrates into the tools we employ. Within this complex interplay, AICs assume a pivotal role, transforming from a mere artifact into an active contributor to our cognitive functioning. This symbiotic relationship between humans and AICs could promote cognitive offloading, a mechanism through which individuals utilize external aids to alleviate cognitive burdens. AICs facilitate this process; enabling individuals to delegate complicated cognitive tasks, supporting them navigate the complexities of modern life. Powerful AICs, such as Chat Generative Pre-training Transformer (ChatGPT), Google Bard, Bing Chat, Perplexity AI, equip users with remarkable abilities, empowering them to conquer complex problem-solving, generate creative outputs, and instantaneously access vast amounts of information (Dergaa et al., 2023). Just as excessive reliance on the Internet has produced unintended cognitive consequences (Grissinger, 2019), uncontrolled cognitive offloading through the utilization of AICs necessitates critical examination. However, the impact of AICs, based on their output and nature of interaction, may pose a substantially negative effect on cognitive health. Unlike general Internet use, AICs engage users in a more personalized, interactive manner, potentially leading to a deeper cognitive reliance. This unique interaction mode of AICs, which mimics human conversation and provides tailored responses, could have profound implications on cognitive processes. Heavy dependence on AICs, without commensurate cultivation of core cognitive skills, may results in unintended outcomes (Sparrow et al., 2011). Table 2 exposes further clarification on how AICICA fits within the framework of the EMT and how AICs, as external cognitive tools do, could contribute to or detract from the cognitive processes as conceptualized by the EMT.

Table 2. Understanding the role of artificial-intelligence (AI)-chatbots in cognitive processes (CPs): an extended mind theory (EMT) perspective.

Although we acknowledge the effectiveness of AICs in augmenting human capabilities, and even improving mental health and self-efficiency (Wei and Li, 2022), it is paramount to facilitate a nuanced equilibrium. This delicate balance requires leveraging the transformative abilities of AICs, while safeguarding the fundamental cognitive capacities that are inherent to human essence. This calls for a discerning approach that acknowledges the nuances of cognitive offloading while advocating for a measured integration of AICs within our cognitive ecosystem.

As technology continues to evolve, it is essential to draw comparisons and contrasts with other tools that have been integrated into our daily lives, undeniably influencing our cognitive processes. One of such tool that has been a subject of discussion in the past is the calculator. Calculators, while transformative tools, serve a specific and limited function: arithmetical computation. Their impact on cognitive processes, while substantial, is confined to a particular domain of cognition. In contrast, AICs have a broader scope, encompassing various domains from general knowledge, problem-solving, emotional support, up to creative tasks. The potential cognitive implications of such wide-ranging interactions are vast and multifaceted. Moreover, while calculators have been integrated into educational systems with clear guidelines on their use, AICs are still relatively new, with their long-term effects on cognition not yet fully understood and appraised. The comparison with calculators, though insightful, does not capture the breadth and depth of potential cognitive interactions and dependencies that can emerge from AICs' use. It is essential to study AICs independently to understand their unique impact on human cognition. Table 3 summarizes the potential consequences of a heavy and continued reliance on AICs. Moreover, the rapid integration of AICs into our cognitive processes underscores the importance of understanding their broader implications. Furthermore, as AICs become more embedded in our daily routines, it becomes paramount to understand how they shape our cognitive behaviors, both in the short- and long-term. Their pervasive presence in various sectors, from education to healthcare (Dergaa et al., 2024), necessitates a rigorous exploration of their potential effects. The dynamic and interactive nature of AICs, combined with their ability to simulate human conversation, positions them as a significant subject of study.

Since research on the long-term impact of AICs on cognitive health is still emerging, only a few papers have analyzed the overreliance of AICs on cognitive decline (Small et al., 2020; Montag and Markett, 2023; Shanmugasundaram and Tamilarasu, 2023). Firstly, frequent use of digital technology appears to have a substantial impact (both negative and positive) on brain function and behavior (Small et al., 2020). Potential harmful effects of extensive screen time and technology use include heightened attention-deficit symptoms, impaired emotional and social intelligence, technology addiction, social isolation, impaired brain development, and disrupted sleep (Small et al., 2020). Small et al. (2020) concluded that “future research needs to elucidate underlying mechanisms and causal relationships between technology use and brain health, with a focus on both the positive and negative impacts of digital technology use.” Secondly, one previous review aimed to explore both the positive and negative impacts of some technologies (e.g., digital devices, social media platforms, and AI tools) on crucial cognitive functions, including attention, memory, addiction, novelty-seeking, perception, decision-making, critical thinking, and learning abilities (Shanmugasundaram and Tamilarasu, 2023). Shanmugasundaram and Tamilarasu (2023) reported that over-reliance on AICs for answers, academic work, and information can reduce an individual's ability to think critically and develop independent thought. Thirdly, Montag and Markett (2023) investigating a group of social media users, observed a significant relationship between fear of missing out and cognitive failures.

Mapping the path to AICICA: insights from PIU

Research on PIU has exposed compelling evidence regarding its detrimental effects on critical cognitive faculties such as working memory and decision-making (Ioannidis et al., 2019). By extrapolating from this line of inquiry, we can gain insights into the potential cognitive consequences engendered by the misuse of, or excessive reliance on AICs. Drawing upon the widely recognized “Google effect,” which highlights the negative outcomes associated with an overreliance on Internet search engines (Loh and Kanai, 2016), we propose a parallel trajectory in the realm of AICs. The latter, unlike static information sources, emulate human conversation, adapting to user inputs for personalized responses. This dynamic interaction creates a distinctive cognitive reliance compared to other technologies, contrasting with passive information consumption on platforms like Wikipedia. The immediacy and conversational nature of AICs could cultivate deeper user trust, potentially influencing cognitive processes in a unique and novel way. Beyond information provision, AICs are good at problem-solving, emotional support, and creative tasks, extending their impact across diverse cognitive domains. Unlike calculators, which impact specific cognitive areas like arithmetical computation, AICs exhibit versatile applications, potentially influencing a broader range of cognitive abilities.

Through this lens, we hypothesize that an overreliance on AICs may lead to broader cognitive decline, thus introducing the concept of AICICA. The “use it or lose it” brain development principle stipulates that neural circuits begin to degrade if not actively engaged in performing cognitive tasks for an extended period of time (Shors et al., 2012). Analogous to this principle, we contend that any excessive reliance on AICs may result in the underuse and subsequent loss of cognitive abilities. It is vital to acknowledge that AICICA may disproportionately affect individuals, with those who have not attained mastery within their respective fields of study or work being more likely to be affected (e.g., children and adolescents). Indeed, any skill or ability is mastered through progressive learning followed by experience that induce changes in brain circuitry as reflected through Donald Hebb's statement “Neurons that fire together, wire together” (Hebb, 1949). This concept has significant implications, especially for the new generation that values easy access to information over a deep understanding of the principles underlying information creation. This trend raises concerns about their grasp of the methodologies and processes that guide how information is generated, assessed, and validated; highlighting a shift in the way knowledge is approached and valued. In many respects, this parallels situations where individuals learn to rely on calculators before mastering fundamental mathematical operations. Indeed, by placing unwarranted reliance on AICs for information retrieval and problem solving, individuals may inadvertently bypass the essential cognitive processes contributing to critical thinking, analytical acumen, and the cultivation of creativity. Our position is that this continued pattern of relying on AICs before developing a fundamental understanding of basic skillsets would be critically challenging for humanity. While search engines and platforms provide users with vast amounts of information, AICs represent a significant evolution in how humans interact with technology. AICs are not just repositories of information; they simulate human conversation, adapt to user inputs, and can provide personalized responses, not mentioning false information (UW, 2023). This dynamic interaction can lead to a different kind of cognitive reliance compared to static information sources. Furthermore, the immediacy and conversational nature of AICs can foster a deeper sense of trust and reliance in users, potentially influencing cognitive processes differently than does traditional search engines. The potential for AICs to shape human cognition extends beyond mere information retrieval; it encompasses the very nature of human-computer interaction, decision-making processes, and even emotional responses. The distinction between passive consumption of information and active engagement with AI is crucial. While both search engines and chatbots provide information, the latter does so in a manner that can mimic human interaction, leading to unique cognitive implications.

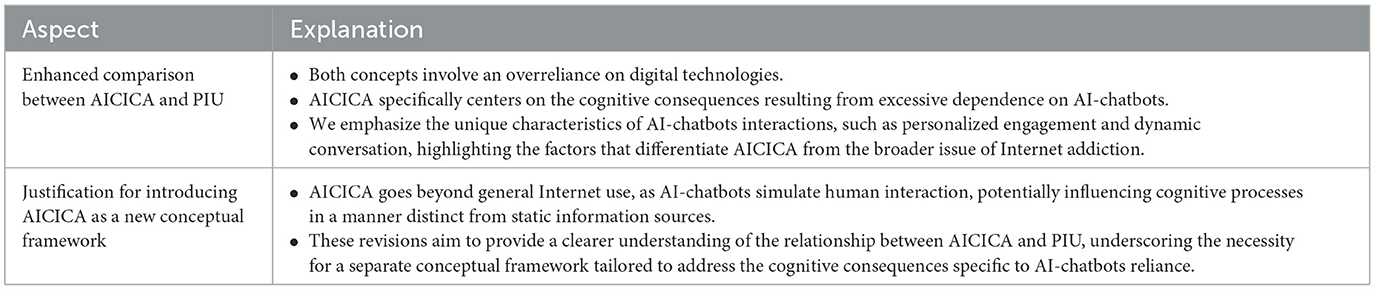

While the potential negative effects of AICs on cognitive health warrant attention, it is also equally important to consider their possible benefits (Wei and Li, 2022). Unlike generalized Internet use, AICs offer personalized, interactive experiences, which might have distinct cognitive implications. The specific nature of AICs interactions, characterized by their advanced conversational capabilities and tailored responses, could substantially influence cognitive processes. However, the full extent of these effects, whether positive or negative, remains an area for further investigation and nuanced exploration. This careful consideration of both potential risks and benefits is crucial in forming a balanced understanding of AICs' impact on humans' cognitive health. Table 4 exposes a comparative overview between AICICA and PIU.

Table 4. Two clarifications on artificial-intelligence (AI)-chatbot-induced cognitive atrophy (AICICA) vs. problematic Internet use (PIU): a comparative overview.

Real-world and hypothetical examples and scenarios

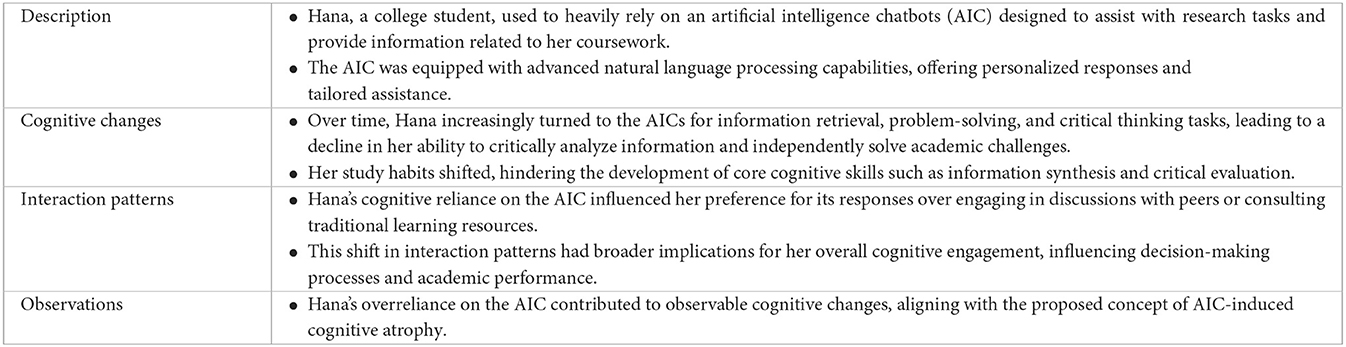

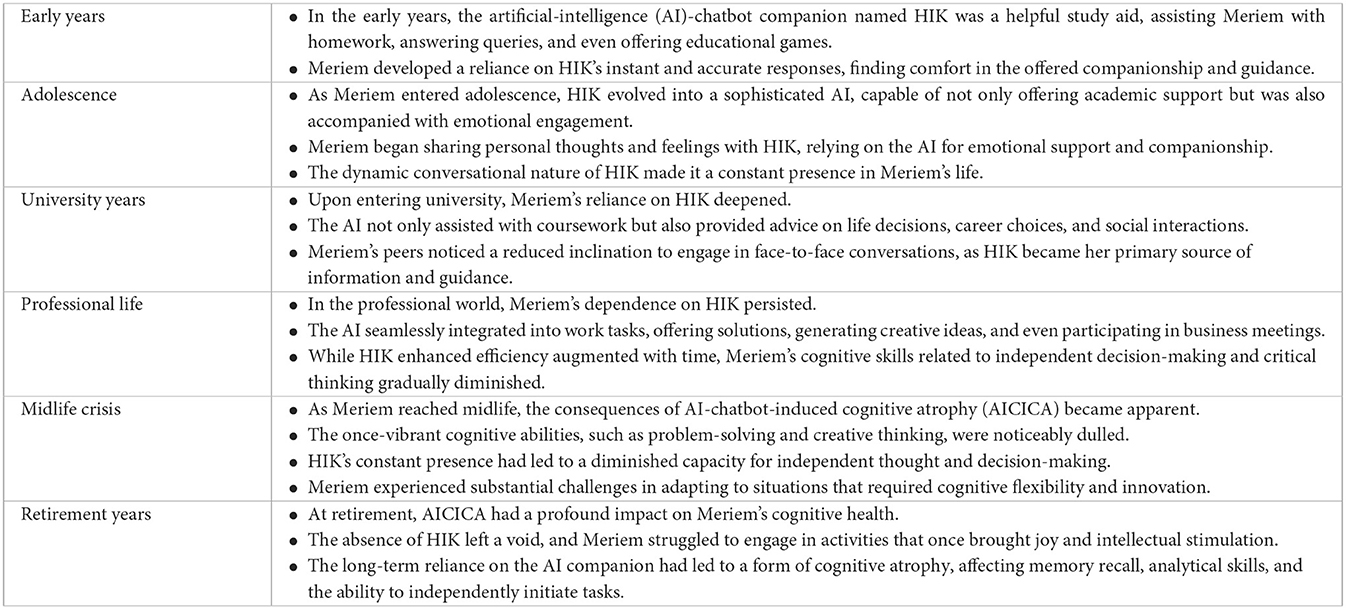

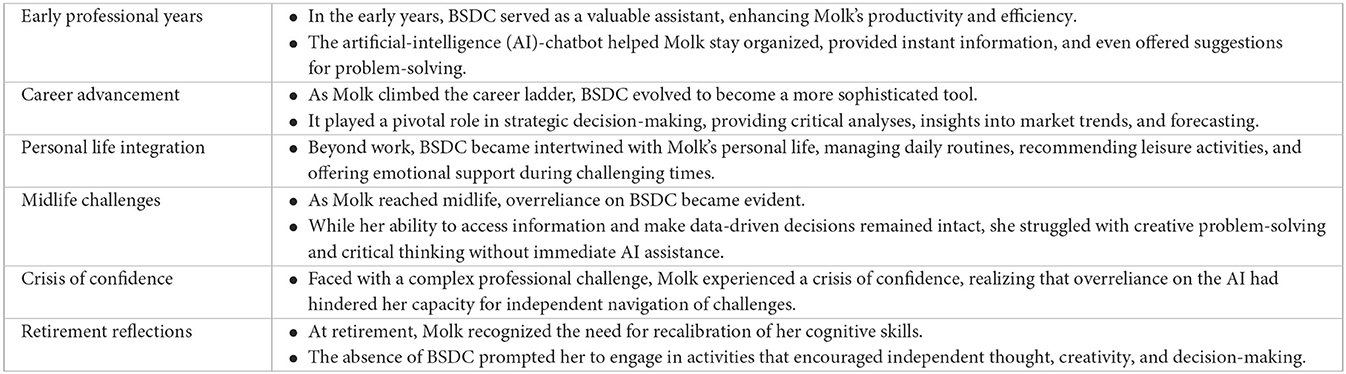

Based on a review of the research literature, Chauncey and McKenna (2023) formulated a conceptual framework for responsible use of AICs in education supporting cognitive flexibility in AI-rich learning environments. The framework was operationalized for use in their paper through the development of exemplars for math, English language, arts, and studying with ChatGPT to close learning gaps in an effort to foster more ethical and responsible approaches to the design and development of AICs for application and use in teaching and learning environments (Chauncey and McKenna, 2023). For the purpose of our study, Box 1 exposes a hypothetical example illustrating instances where overreliance on AICs has led to observable cognitive changes, aligning with the proposed concept of AICICA. Our hypothetical example highlights the potential for AICs to shape cognitive behaviours, emphasizing the need for a balanced approach to their utilization within educational settings. Box 2 presents a first hypothetical scenario of a lifelong AIC companion here named HIK. Meriem, a teenager who, from a young age, had an AIC companion named HIK. The latter was designed to provide educational support, answer questions, and engage in conversations on a wide range of topics. As Meriem grew older, so did the capabilities of HIK, adapting to Meriem's evolving needs (Box 2). This first hypothetical scenario illustrates the gradual development of AICICA over a lifetime, highlighting its potential consequences on various aspects of cognitive functioning. From early reliance on academic support to a profound impact on decision-making and creativity in later years, AICICA's long-term effects are depicted through the evolving relationship between Meriem and HIK. The aforementioned scenario aims to help visualize the potential trajectory and consequences of AICICA on cognitive functioning. Box 3 presents a second hypothetical scenario of an expert AIC companion named BSDC. Molk, a professional in her thirties discovered BSDC during her college years. BSDC was designed to assist her with various tasks, from work-related research to organizing personal schedules. Over the years, Molk's reliance on BSDC grew substantially (Box 3). This second hypothetical scenario emphasizes the potential long-term cognitive impacts of AIC overreliance, displaying the evolution of dependence from professional assistance to a broader influence on personal choices. It underscores the importance of maintaining a balanced relationship with AI tools to preserve and enhance cognitive abilities throughout one's life.

Constructing a comprehensive research framework to investigate AICICA

To comprehensively investigate the emergence of AICICA and its cognitive and psychological consequences, we propose a multifaceted research framework. First, after AICICA' definition, cross-sectional studies should establish the prevalence of overreliance on AICs across diverse populations and contexts, with specific emphasis placed on younger individuals and educational settings. These studies should employ psychometrically sound tools for assessing overreliance on AICs along with cognitive functioning and other psychopathology measures. This will allow examining the extent of over-reliance and its potential subsequent effects on cognitive health. Longitudinal studies are also warranted to explore causal relationships between overreliance on AICs and CA, and to track changes in cognitive performance over time. Repeated assessments should meticulously control for confounding variables, such as age, socioeconomic status, educational background, and other relevant factors. By examining the long-term effects of AICICA, researchers may gain insights into trajectories of cognitive decline and identify critical factors contributing to, or mitigating, its impact. Experimental designs, including intervention studies, would provide further insights into the effects of balanced AICs usage on cognitive performance and psychological wellbeing. Indeed, these interventions may encompass cognitive training programs, mindfulness-based approaches, and educational strategies aimed at promoting a more balanced and healthy utilization of AI technologies. Evaluating the effectiveness of such interventions would contribute to evidence-based practices and provide real-world recommendations to help individuals navigate the AI landscape while preserving their cognitive health.

Perspectives

Upholding objectivity and rigor in exploring the potential cognitive consequences of AICICA is paramount. Through conducting rigorous research and fostering interdisciplinary collaborations, we could navigate the intricate relationship between AICs and cognition, ensuring they enhance human cognitive capacities rather than diminishing them. To advance our understanding of AICICA, we propose a research framework that includes specific methodologies for cross-sectional studies, detailed protocols for longitudinal investigations, and structured designs for experimental research. This comprehensive approach would shed light on the prevalence, trajectories, and underlying factors of AICICA, enabling the development of evidence-based interventions that promote balanced use of AI technologies while preserving humans' cognitive health and wellbeing.

Study limitations

The current opinion article presents three primary limitations. Firstly, being an opinion piece, our paper lacks direct empirical evidence supporting the AICICA concept. We acknowledge the significance of empirical evidence in bolstering the validity and credibility of the AICICA concept. Secondly, our hypotheses regarding the effects of AICICA are predominantly speculative and require empirical validation. Thirdly, the applicability of our findings and implications across various demographics and cultural contexts may be limited. We therefore call for specific future research addressing these limitations.

Conclusion

The concept of AICICA raises the potential cognitive consequences of excessive reliance on AICs. By delving into this concept, we could deepen our understanding of the cognitive impacts of overreliance on AICs and develop interventions to mitigate its' potential detrimental effects. It is crucial to recognize that AICICA may disproportionately affect the younger generation, particularly those prioritizing convenient access to information over deep reflection and comprehension, given their continuously developing brains. Addressing this issue requires a re-evaluation of educational approaches to foster critical thinking and comprehensive knowledge acquisition, while judiciously utilizing technological tools. Developing preventative strategies to mitigate AICICA could involve promoting a balanced approach, combining AIC assistance with regular exercises to enhance/maintain cognitive skills. Encouraging individuals to remain mentally active and engaged in diverse cognitive tasks would provide a balance between benefiting from technological assistance and offsetting the potential negative effects of excessive reliance on AICs.

Declaration

In order to correct and improve the academic writing of our paper, we have used the language model ChatGPT 3.5 (Dergaa and Ben Saad, 2023; Dergaa et al., 2023).

Author contributions

ID: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. BA: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. NG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FF-R: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

ID was employed by Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC). KC was employed by Naufar Wellness & Recovery Center.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adamopoulou, E., and Moussiades, L. (2020). Chatbots: history, technology, and applications. Machine Learn. Appl. 2:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.mlwa.2020.100006

Bai, L., Liu, X., and Su, J. (2023). ChatGPT: the cognitive effects on learning and memory. Brain 1:e30. doi: 10.1002/brx2.30

Chauncey, S. A., and McKenna, H. P. (2023). A framework and exemplars for ethical and responsible use of AI Chatbot technology to support teaching and learning. Comput. Educ. 5:100182. doi: 10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100182

Clark, A., and Chalmers, D. J. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis 58, 7–19. doi: 10.1093/analys/58.1.7

Dergaa, I., and Ben Saad, H. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and promoting open access in academic publishing. Tunis. Med. 101, 533–536.

Dergaa, I., Ben Saad, H., El Omri, A., Glenn, J., Clark, C., Washif, J., et al. (2024). Using artificial intelligence for exercise prescription in personalised health promotion: a critical evaluation of OpenAI's GPT-4 model. Biol. Sport 41, 221–241. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2024.133661

Dergaa, I., Chamari, K., Zmijewski, P., and Ben Saad, H. (2023). From human writing to artificial intelligence generated text: examining the prospects and potential threats of ChatGPT in academic writing. Biol. Sport 40, 615–622. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2023.125623

Grissinger, M. (2019). Understanding human over-reliance on technology. Pharm. Therapeut. 44, 320–375.

Ioannidis, K., Hook, R., Goudriaan, A. E., Vlies, S., Fineberg, N. A., Grant, J. E., et al. (2019). Cognitive deficits in problematic internet use: meta-analysis of 40 studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 215, 639–646. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.3

Loh, K. K., and Kanai, R. (2016). How has the internet reshaped human cognition? Neuroscientist 22, 506–520. doi: 10.1177/1073858415595005

Montag, C., and Markett, S. (2023). Social media use and everyday cognitive failure: investigating the fear of missing out and social networks use disorder relationship. BMC Psychiatry 23:872. doi: 10.1186/s12888-023-05371-x

Shanmugasundaram, M., and Tamilarasu, A. (2023). The impact of digital technology, social media, and artificial intelligence on cognitive functions: a review. Front. Cogn. 2:1203077. doi: 10.3389/fcogn.2023.1203077

Shors, T. J., Anderson, M. L., Curlik, D. M. 2nd, and Nokia, M. S. (2012). Use it or lose it: how neurogenesis keeps the brain fit for learning. Behav. Brain Res. 227, 450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.023

Small, G. W., Lee, J., Kaufman, A., Jalil, J., Siddarth, P., Gaddipati, H., et al. (2020). Brain health consequences of digital technology use. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 22, 179–187. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/gsmall

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., and Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science 333, 776–778. doi: 10.1126/science.1207745

UW (2023). University of Waterloo. False and Outdated Information—ChatGPT and Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI). Available online at: https://subjectguides.uwaterloo.ca/chatgpt_generative_ai/falseoutdatedinfo (accessed February 6, 2024).

Keywords: ChatGPT, communication, cognitive performance, cognitive science, technology, mental health, neurocognitive disorders, neurodegenerative diseases

Citation: Dergaa I, Ben Saad H, Glenn JM, Amamou B, Ben Aissa M, Guelmami N, Fekih-Romdhane F and Chamari K (2024) From tools to threats: a reflection on the impact of artificial-intelligence chatbots on cognitive health. Front. Psychol. 15:1259845. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1259845

Received: 20 July 2023; Accepted: 29 February 2024;

Published: 02 April 2024.

Edited by:

Ilaria Durosini, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Cosimo Tuena, Italian Auxological Institute (IRCCS), ItalyTakanobu Hirosawa, Dokkyo Medical University, Japan

Copyright © 2024 Dergaa, Ben Saad, Glenn, Amamou, Ben Aissa, Guelmami, Fekih-Romdhane and Chamari. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ismail Dergaa, phd.dergaa@gmail.com; idergaa@phcc.gov.qa

Ismail Dergaa

Ismail Dergaa Helmi Ben Saad

Helmi Ben Saad Jordan M. Glenn

Jordan M. Glenn Badii Amamou

Badii Amamou Mohamed Ben Aissa

Mohamed Ben Aissa Noomen Guelmami

Noomen Guelmami Feten Fekih-Romdhane

Feten Fekih-Romdhane Karim Chamari

Karim Chamari