Despite desperately wanting a dog, like many children, because of restricted financial circumstances, I did not have the good fortune of owning a dog as a child. However, research may overcome this barrier so that lack of dog ownership need not be a barrier to spending time with and walking dogs.

The US Department of Health and Human Services recommends walking 5 days a week for at least 45 minutes at a time, with 30 minutes at a moderate to brisk pace of 3–4 miles per hour and 15 minutes at a very brisk walking of 5–6 miles per hour (1). This level of physical activity is associated with a decreased risk of mortality, cardiorespiratory disease, and increased likelihood for weight-loss, and improvements in musculoskeletal health (2). Only about half of Americans engage in this recommended amount of physical activity (3). But if every American had a healthy dog and walked it regularly, they would be more likely to achieve these recommended levels of activity (4).

Multiple studies show that dog ownership improves human health. Becoming a dog owner increases physical activity (4–7) and walking (8–10), reduces your weight (11), and decreases your odds of diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and depression (12–15). Dog ownership reduces predictors of negative cardiovascular outcomes like blood pressure (15–19), triglycerides (20, 21), and stress (22–25). Indeed, owning a dog increases the likelihood of you surviving a heart attack (26–28) such that even the American Heart Association advocates dog ownership as a way to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease (29). Australian, German, and Chinese studies show that pet ownership decreases doctor visits, and reduces the likelihood of cardiac problems and sleeping difficulties (30–33). Interventions with dogs improve the outcome of children, adolescents, and adults with a range of medical and psychological problems including post-traumatic stress disorder, developmental disabilities, schizophrenia, autism-spectrum disorders, and cancer (34–38). In a short period of time, human-animal studies have progressed from small experimental studies to studies assessing the public health impact of dogs on human lives, including increasing human physical activity, please see these reviews (6, 34–43).

Despite the double challenge of conducting clinical trials with humans and animals (44) randomized controlled trials are needed in this field. For instance in considering the needs of both dogs and humans, human-animal trials require approval from both human and animal institutional review boards. However, the randomized controlled trial is the gold standard for the assessment of intervention efficacy because it most effectively and efficiently evaluates an intervention's effect, eliminating systematic, and random bias (45).

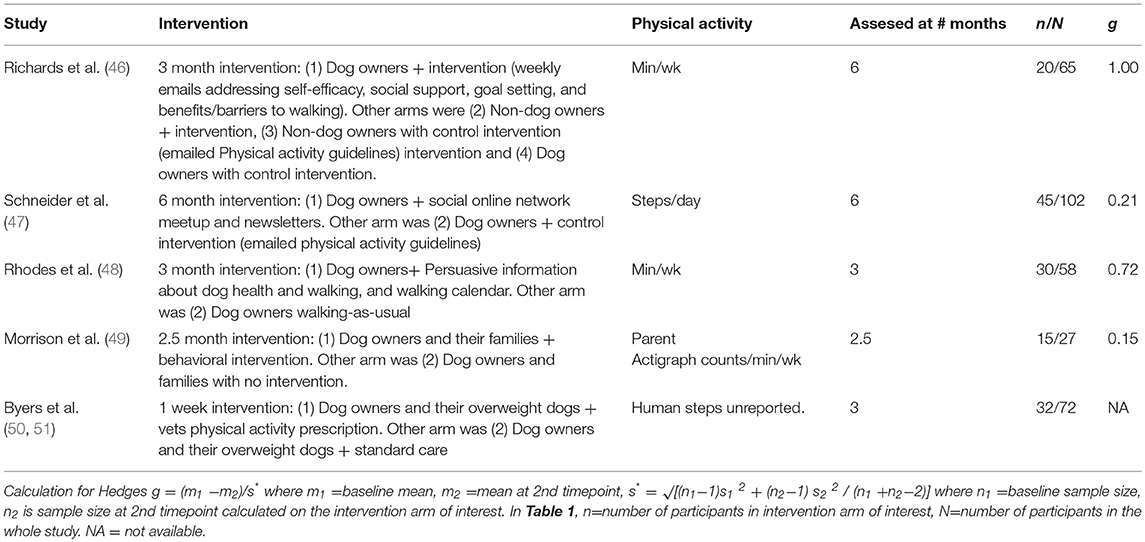

A search using the terms “randomized controlled trial” AND “dogs” and “walking” resulted in 40 hits in PubMed up to 4/15/2018. When studies with groups with psychological or medical problems were excluded, this yielded five randomized controlled trials (46–51), that examine the effects of dog-walking on human walking, see Table 1. An effect size could not be calculated for one of the five randomized controlled trials, and of the remaining 4 randomized controlled trials, two had moderate to large effects (Hedges g) for the dog-walking intervention arm, and two of the four had small effects.

Table 1. Randomized controlled trials examining the effect of dog-walking interventions on human walking.

These randomized controlled trials focus on dog owners walking their dogs. However, randomized controlled trials that focus on dog owners walking their own dogs may limit whether dog-walking interventions can be “scaled-up” or implemented on a more widespread basis (52).

Certain correlates may distinguish dog owners from non-dog owners. For instance, a large US study showed that dog ownership is associated with being white, with home ownership, and with living in a house (53). A review of the literature also suggests that living close to places wheredogs can be walked (41) also increases the likelihood of owning a dog. The implication of this is that racial diversity, renting rather than owning a home, living in an apartment, and possibly socioeconomic disadvantage may decrease the likelihood of dog ownership. So although 44% of households in the US (2015–2016) are estimated to own a dog, the majority of households do not (54).

But does lack of dog ownership have to be a barrier to dog-walking interventions? One of the foreseeable challenges for dog-walking interventions targeting human physical activity is working out how to scale this intervention to individuals who do not own a dog. There are numerous online media reports of shelter dog-walking programs, even phone applications for walking shelter dogs. However, trials published in peer-reviewed journals are scant (55, 56). One small open trial with public housing residents showed that overweight individuals who borrowed and walked dogs from a dog-shelter had small (hedges g = 0.17), but significant weight loss (57). This suggests that pairing individuals who do not own a dog with dogs in rescues or shelters may be a feasible weight loss solution.

Designing behavioral interventions that can “scale-up” is increasingly becoming an important criteria for the success of an intervention (58, 59). One of the ways that this critical barrier can be addressed is by considering mutually beneficial partnerships between dog shelters/rescues and other institutions, some of which may seem improbable at first.

An important start is to take into account both the socio-ecological structure and function of institutions. Drawing on Bronferonner's work (60), Westgarth et al. (41) describes the structure of a socio-ecological model of dog-walking that highlights the individual sphere of influence and its dog-related factors, as well as more distal social-environmental, and physical-environmental factors that are associated with dog-walking (6). This can add to a consideration of the functions of different institutions and how these can promote healthy behaviors in both individuals and institutions.

Human-dog relationships have been described as a form of social capital which is defined as an “investment in social relations with expected returns” (61–63). On a system-level mutually reinforcing, sustainable partnerships can be formed between institutions to improve the health of both humans and animals (62, 63). Social capital requires the utilization of resources embedded in a social structure, accessibility to this, and the mobilization of these resources for purposive action, e.g., improved health for both humans and animals (62, 63). Increasing physical activityis a serious public health challenge; as is ensuring that homeless dogs are cared for. Considering a model of human-dog interventions that considers function as well as the structure of institutions and individuals is empowering and self-sustaining, and has the potential to build scalable, sustainable interventions.

Everyone who does not own a dog could probably benefit from walking a dog daily. However, there may be certain institutions that could provide the other half of a mutually beneficial partnership. For instance, with appropriate supervision, various institutions could offer dog-walking opportunities: health care institutions like rehabilitation centers, half-way houses, group homes or elder care facilities; educational institutions, such as colleges or schools; even insurance companies.

Is it possible to do something like this? Recently undergraduates at Temple University undertook this endeavor. Temple University is a large urban college in Center City Philadelphia consisting of a socioeconomically and racially diverse group of more than 30,000 undergraduates. After a review of the literature (64) over the summer of 2017, one of my lab undergraduates sent an informational Facebook message on July 18th, 2017 to the incoming freshmen class and in one day 22 incoming freshmen posted their interest (and photos of their dogs) in joining a volunteer dog-walking association, with another 56 freshmen signing up. In 10 days, 172 incoming freshmen posted their interest in joining the volunteer dog-walking association. On December 6th, 2017, the “Diamond Dogs” undergraduate dog-walking association was formally ratified by the university, with support from the Dean's office and since then there have been 3 townhall meetings of ~70 students a time. “Diamond Dogs” is partnered with two inner-city dog rescues approximately a mile from Temple University's campus. My last communication with the rescues was that students are participating in their orientations and training and are walking their dogs. From the perspective of dog rescues, this is a “win-win.” Inner city rescues in Philadelphia find it difficult to recuit regular dog-walkers but a schedule of regular volunteer walkers has eased their need to play and to walk their healthy dogs daily.

Humans form strong attachments to pets, particularly dogs (65–68) and pets increase social capital through creating more social connections and networks (61, 69, 70). But will people who don't own a dog develop an attachment for a dog at a shelter or rescue who may leave in a couple of weeks because they have been adopted? Are the positive cardiovascular effects in response to stressful situations also found in non-dog owners who interact with shelter or rescue dogs (71)? Can shelter/rescue dog-walking interventions increase the likelihood of walkers to eventually adopt a dog? Can cortisol or immunological measures be used to check that shelter/rescue dogs are experiencing less stress with regular walkers (72)? While these are important research questions there are also important ethical and practical issues to consider in research of this nature.

Rescue and shelter dogs often have greater psychological and medical needs than dogs not in a shelter or rescue. Volunteers at shelters are likely to be pet-owners (73) and shelters and rescues are likely to prefer experienced dog owners rather than non-dog owners to walk their dogs. Guidelines from the Association of Shelter Veterinarians (74), and from the American Veterinary Medical Association (75) and the Humane Society (76) highlight the importance of training and supervising shelter and rescue volunteers, including basic training in animal handling and bite prevention. However, research addressing the training of non-dog owner volunteers is in its infancy (77, 78). Some questions that will need to be answered include: how much training do non-dog owner volunteer walkers need to achieve the skill level of experienced dog owners? How are these skills best assessed? And what are the effects of volunteers with varied experience on shelter dogs?

Assessing the efficacy of shelter dog-walking intervention for non- owners, deserves the best designs and methods. This means that non-peer reviewed reports by the media are not sufficient as evidence for the efficacy of interventions like this and the use of phone applications to encourage the walking of shelter dogs warrant thoughtful and rigorous testing prior to widespread use or claims about their effect. Clinical trials with shelter dogs and humans need to meet both Human Institutional Review Board and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee requirements. The design and oversight of these trials require the partnership of human clinical trial experts, human-animal intervention research experts, veternarians, and shelters/rescues. There are not only ethical issues that must be considered but also legal issues in clinical trials of this nature. For instance animal rescues in the United States are governed by state, county and city ordinances that may differ between rescues. Careful attention to these ordinances are needed in rescue dog-walking intervention trials.

It is important to conduct clinical trials to test if it is possible to engage educational and social institutions in mutually reinforcing partnerships to improve the health of people and animals. The Shelter dog-walking intervention proposed can potentially make dog-walking a scalable intervention and has broad applicability to a wide variety of institutions and partnerships.

Despite the challenges, I'm looking forward to a future where everyone can walk a dog even if they don't own one.

Author Contributions

EC conceived of this idea and opinion and wrote this paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report (2018). Available online at: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/ (Accessed November 20, 2018).

2. American College of Sports Medicine's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription 10th ed. China: Wolters Kluwer (2018).

3. Clarke TC, Norris T, Schiller JS. Early Release of Selected Estimates Based on Data from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics (2017). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/releases/released201705.htm#TechNotes

4. Soares J, Epping JN, Owens CJ, Brown DR, Lankford TJ, Simoes EJ, et al. Odds of getting adequate physical activity by dog walking. J Phys Activity Health (2015) 12:S102–S9.

5. Yabroff KR, Troiano RP, Berrigan D. Walking the dog: is pet ownership associated with physical activity in California? J Phys Activity Health (2008) 5:216–28. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.2.216

6. Christian HE, Westgarth C, Bauman A, Richards EA, Rhodes RE, Evenson KR, et al. Dog ownership and physical activity: a review of the evidence. J Phys Activity Health (2013) 10:750–9. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.5.750

7. Serpell J. Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. J R Soc Med. (1991) 84:717. doi: 10.1177/014107689108401208

8. Cutt HE, Knuiman MW, Giles-Corti B. Does getting a dog increase recreational walking? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity (2008) 5:17. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-17

9. Oka K, Shibata A. Dog ownership and health-related physical activity among Japanese adults. J Phys Activity Health (2009) 6:412–8. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.4.412

10. Christian H, Wood L, Nathan A, Kawachi I, Houghton S, Martin K, et al. The association between dog walking, physical activity and owner's perceptions of safety: cross-sectional evidence from the US and Australia. BMC Public Health (2016) 16:1010. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3659-8

11. Coleman KJ, Rosenberg DE, Conway TL, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, et al. Physical activity, weight status, and neighborhood characteristics of dog walkers. Prevent Med. (2008) 47:309–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.05.007

12. Lentino C, Visek AJ, McDonnell K, DiPietro L. Dog walking is associated with a favorable risk profile independent of moderate to high volume of physical activity. J Phys Activity Health (2012) 9:414–20. doi: 10.1123/jpah.9.3.414

13. Aiba N, Hotta K, Yokoyama M, Wang G, Tabata M, Kamiya K, et al. Usefulness of pet ownership as a modulator of cardiac autonomic imbalance in patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and/or hyperlipidemia. Am J Cardiol. (2012) 109:1164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.055

14. Weber KS, Roden M, Mussig K. Do dogs sense hypoglycaemia? Diabet Med. (2016) 33:934–8. doi: 10.1111/dme.12975

15. Anderson WP, Reid CM, Jennings GL. Pet ownership and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Med J Austr. (1992) 157:298–301.

16. Chowdhury EK, Nelson MR, Jennings GL, Wing LM, Reid CM, Committee AM. Pet ownership and survival in the elderly hypertensive population. J Hypertension (2017) 35:769–75. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001214

17. Grossberg JM, Alf EF. Interaction with pet dogs: effects on human cardiovascular response. J Delta Soc. (1985) 2:20–7.

18. Jenkins JL. Physiological effects of petting a companion animal. Psychol Rep. (1986) 58:21–2. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1986.58.1.21

19. Allen K, Blascovich J, Mendes WB. Cardiovascular reactivity and the presence of pets, friends, and spouses: the truth about cats and dogs. Psychosom Med. (2002) 64:727–39. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000024236.11538.41

20. Dembicki D, Anderson J. Pet ownership may be a factor in improved health of the elderly. J Nutr Elderly (1996) 15:15–31. doi: 10.1300/J052v15n03_02

21. Schreiner PJ. Emerging cardiovascular risk research: impact of pets on cardiovascular risk prevention. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. (2016) 10:8. doi: 10.1007/s12170-016-0489-2

22. Barker SB, Knisely JS, McCain NL, Best AM. Measuring stress and immune response in healthcare professionals following interaction with a therapy dog: A pilot study. Psychol Rep. (2005) 96:713–29. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.3.713-729

23. Beetz A, Kotrschal K, Turner DC, Hediger K, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Julius H. The effect of a real dog, toy dog and friendly person on insecurely attached children during a stressful task: an exploratory study. Anthrozoös (2011) 24:349–68. doi: 10.2752/175303711X13159027359746

24. Odendaal J. Animal-assisted therapy—magic or medicine? J Psychosomat Res. (2000) 49:275–80. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(00)00183-5

25. Krause-Parello CA, Tychowski J, Gonzalez A, Boyd Z. Human–canine interaction: exploring stress indicator response patterns of salivary cortisol and immunoglobulin A. Res Theory Nurs Pract. (2012) 26:25–40. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.26.1.25

26. Friedmann E, Katcher AH, Lynch JJ, Thomas SA. Animal companions and one-year survival of patients after discharge from a coronary care unit. Public Health Rep. (1980) 95:307.

27. Friedmann E, Thomas SA. Pet ownership, social support, and one-year survival after acute myocardial infarction in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). Am J Cardiol. (1995) 76:1213–7. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80343-9

28. Friedmann E, Thomas SA, Son H. Pets, depression and long-term survival in community living patients following myocardial infarction. Anthrozoös (2011) 24:273–85. doi: 10.2752/175303711X13045914865268

29. Levine GN, Allen K, Braun LT, Christian HE, Friedmann E, Taubert KA, et al. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation (2013) 127:2353–63. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829201e1

30. Headey B. Health benefits and health cost savings due to pets: preliminary estimates from an Australian national survey. Soc Indic Res. (1999) 47:233–43. doi: 10.1023/A:1006892908532

31. Headey B, Grabka M, Kelley J, Reddy P, Tseng Y-P. Pet ownership is good for your health and saves public expenditure too: Australian and German longitudinal evidence. Austr Soc Monitor (2002) 5:93–9. Available online at: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=674270738133649;res=IELBUS

32. Headey B, Grabka MM. Pets and human health in Germany and Australia: National longitudinal results. Soc Indic Res. (2007) 80:297–311. doi: 10.1007/s11205-005-5072-z

33. Headey B, Na F, Zheng R. Pet dogs benefit owners' health: a ‘natural experiment’ in China. Soc Indic Res. (2008) 87:481–93. doi: 10.1007/sl1205-007-9142-2

34. Nimer J, Lundahl B. Animal-assisted therapy: a meta-analysis. Anthrozoös (2007) 20:225–38. doi: 10.2752/089279307X224773

35. Brelsford VL, Meints K, Gee NR, Pfeffer K. Animal-Assisted Interventions in the Classroom—a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2017) 14:669. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070669

36. Maujean A, Pepping CA, Kendall E. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of animal-assisted therapy on psychosocial outcomes. Anthrozoös (2015) 28:23–36. doi: 10.2752/089279315X14129350721812

37. Hoagwood KE, Acri M, Morrissey M, Peth-Pierce R. Animal-assisted therapies for youth with or at risk for mental health problems: a systematic review. Appl Dev Sci. (2017) 21:1–13. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2015.1134267

38. Gee NR, Griffin JA, McCardle P. Human–animal interaction research in school settings: current knowledge and future directions. AERA Open (2017) 3:2332858417724346. doi: 10.1177/2332858417724346

39. Christian H, Bauman A, Epping JN, Levine GN, McCormack G, Rhodes RE, et al. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2016) 12:233–43. doi: 10.1177/1559827616643686

40. Purewal R, Christley R, Kordas K, Joinson C, Meints K, Gee N, et al. Companion animals and child/adolescent development: a systematic review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2017) 14:234. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030234

41. Westgarth C, Christley RM, Christian HE. How might we increase physical activity through dog walking?: a comprehensive review of dog walking correlates. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2014) 11:83. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-83

42. Arhant-Sudhir K, Arhant-Sudhir R, Sudhir K. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk reduction: supporting evidence, conflicting data and underlying mechanisms. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2011) 38:734–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05583.x

43. McCune S, Kruger KA, Griffin JA, Esposito L, Freund LS, Hurley KJ, et al. Evolution of research into the mutual benefits of human–animal interaction. Anim Front. (2014) 4:49–58. doi: 10.2527/af.2014-0022

44. Serpell J, McCune S, Gee N, Griffin JA. Current challenges to research on animal-assisted interventions. Appl Dev Sci. (2017) 21:223–33. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2016.1262775

45. American Psychological Association. Criteria for evaluating treatment guidelines. Am Psychol. (2002) 57:1052–9. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.57.12.1052

46. Richards EA, Ogata N, Cheng C-W. Randomized controlled theory-based, e-mail-mediated walking intervention: differences between dog owners and non-dog owners. Clin Nurs Res. (2017) 26:47–67. doi: 10.1177/1054773816657799

47. Schneider KL, Murphy D, Ferrara C, Oleski J, Panza E, Savage C, et al. An online social network to increase walking in dog owners: a randomized trial. Med Sci Sports Exercise (2015) 47:631. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000441

48. Rhodes RE, Murray H, Temple VA, Tuokko H, Higgins JW. Pilot study of a dog walking randomized intervention: effects of a focus on canine exercise. Prevent Med. (2012) 54:309–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.014

49. Morrison R, Reilly JJ, Penpraze V, Westgarth C, Ward DS, Mutrie N, et al. Children, parents and pets exercising together (CPET): exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health (2013) 13:1096. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1096

50. Byers CG, Wilson CC, Stephens MB, Goodie JL, Netting FE, Olsen CH. Owners and pets exercising together: Canine response to veterinarian-prescribed physical activity. Anthrozoös (2014) 27:325–33. doi: 10.2752/175303714X14036956449224

51. Stephens MB, Wilson CC, Goodie JL, Netting FE, Olsen CH, Byers CG. Health perceptions and levels of attachment: owners and pets exercising together. J Am Board Family Med. (2012) 25:923–6. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.110325

52. Milat AJ, King L, Bauman AE, Redman S. The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot Int. (2012) 28:285–98. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar097

53. Saunders J, Parast L, Babey SH, Miles JV. Exploring the differences between pet and non-pet owners: implications for human-animal interaction research and policy. PloS ONE (2017) 12:e0179494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179494

55. Gunter L, Protopopova A, Hooker SP, Der Ananian C, Wynne CDL. Impacts of encouraging dog walking on returns of newly adopted dogs to a shelter. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. (2017) 20:357–71. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2017.1341318

56. Bright TM, Hadden L. Safewalk: improving enrichment and adoption rates for shelter dogs by changing human behavior. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. (2017) 20:95–105. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2016.1247353

57. Johnson RA, Meadows RL. Dog-walking: motivation for adherence to a walking program. Clin Nurs Res. (2010) 19:387–402. doi: 10.1177/1054773810373122

58. Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC, et al. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet (2016) 388:1337–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30728-0

59. Lutz W. Global sustainable development priorities 500 y after luther: Sola schola et sanitate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:6904–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702609114

60. Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (1979).

62. Wood L, Giles-Corti B, Bulsara M. The pet connection: pets as a conduit for social capital? Soc Sci Med. (2005) 61:1159–73. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.017

64. Chen E, Murray S, Arlt J, Middleton D, Conklin C, Windom CAA, et al. Systematic review of RCTs for Dog-walking and Pilot Study with Fitbark & Fitbit M-Health Devices. The Obesity Society: Obesity Week 2017. Washington, DC (2017). Available online at: https://higherlogicdownload.s3.amazonaws.com/OBESITY/004d4f70-37d5-434e-b24d-08a32dfdfcd9/UploadedImages/2017ow_abstracts/11-2-Thursday-LB-Poster-Abstracts.pdf (Accessed November 20, 2018).

65. Archer J. Why do people love their pets? Evol Hum Behav. (1997) 18:237–59. doi: 10.1016/S0162-3095(99)80001-4

66. Stallones L, Marx MB, Garrity TF, Johnson TP. Pet ownership and attachment in relation to the health of US adults, 21 to 64 years of age. Anthrozoös (1990) 4:100–12. doi: 10.2752/089279391787057206

67. Marx MB, Stallones LB, Garrity TF, Johnson TP. Demographics of pet ownership among U.S. adults 21 to 64 years of age. Anthrozoös (1988) 2:33–7. doi: 10.2752/089279389787058262

68. Zasloff RL. Measuring attachment to companion animals: a dog is not a cat is not a bird. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (1996) 47:43–8. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(95)01009-2

69. Wood LJ, Giles-Corti B, Bulsara MK, Bosch DA. More than a furry companion: the ripple effect of companion animals on neighborhood interactions and sense of community. Soc Anim. (2007) 15:43–56. doi: 10.1163/156853007X169333

70. Wood L, Martin K, Christian H, Nathan A, Lauritsen C, Houghton S, et al. The pet factor–companion animals as a conduit for getting to know people, friendship formation and social support. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0122085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122085

71. Kingwell BA, Lomdahl A, Anderson WP. Presence of a pet dog and human cardiovascular responses to mild mental stress. Clin Autonom Res. (2001) 11:313–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02332977

72. Dreschel N, Granger D. Advancing the social neuroscience of human-animal interaction: the role of salivary bioscience. In: Freund L, McCardle P, Esposito L, Griffin J, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Human-Animal Interaction Washington, DC: American Psychological Association (2016). p. 210–30. doi: 10.1037/14856-001

73. Neumann SL. Animal welfare volunteers: who are they and why do they do what they do? Anthrozoös (2010) 23:351–64. doi: 10.2752/175303710X12750451259372

74. Newbury S, Blinn MK, Bushby PA, Cox CB, Dinnage JD, Griffin B, et al. Guidelines for Standards of Care in Animal Shelters. Association of Shelter Veterinarians (2010), 1–64. Available online at: https://www.sheltervet.org/assets/docs/shelter-standards-oct2011-wforward.pdf (Accessed November 20, 2018).

75. American Veterinary Medical Association. Guidelines for Animal Assisted Activity, Animal-Assisted Therapy and Resident Animal Programs (2009). Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association.

76. McFarland B. Volunteer Management for Animal Care Organizations. 2nd ed. The Humane Society of the United States. Washington, DC: Human Society Press (2005).

77. Howard VJ, DiGennaro Reed FD. Training shelter volunteers to teach dog compliance. J Appl Behav Anal. (2014) 47:344–59. doi: 10.1002/jaba.120

Keywords: animals, dogs, walking, overweight, students, humans, animal-assisted therapy

Citation: Chen EY (2018) To a Future Where Everyone Can Walk a Dog Even if They Don't Own One. Front. Public Health 6:349. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00349

Received: 15 April 2018; Accepted: 09 November 2018;

Published: 30 November 2018.

Edited by:

Peggy D. McCardle, Consultant, New Haven, CT, United StatesReviewed by:

Carri Westgarth, University of Liverpool, United KingdomCopyright © 2018 Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eunice Y. Chen, ZXVuaWNlLmNoZW5AdGVtcGxlLmVkdQ==

Eunice Y. Chen

Eunice Y. Chen