- 1Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

- 2Human Flourishing Program, Institute for Quantitative Social Science, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

- 3Paediatric-Adolescent Treatment Africa, Cape Town, South Africa

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created extraordinary challenges and prompted remarkable social changes around the world. The effects of COVID-19 and the public health control measures that have been implemented to mitigate its impact are likely to be accompanied by a unique set of consequences for specific subpopulations living in low-income countries that have fragile health systems and pervasive social-structural vulnerabilities. This paper discusses the implications of COVID-19 and related public health interventions for children and young people living in Eastern and Southern Africa. Actionable prevention, care, and health promotion initiatives are proposed to attenuate the negative effects of the pandemic and government-enforced movement restrictions on children and young people.

Introduction

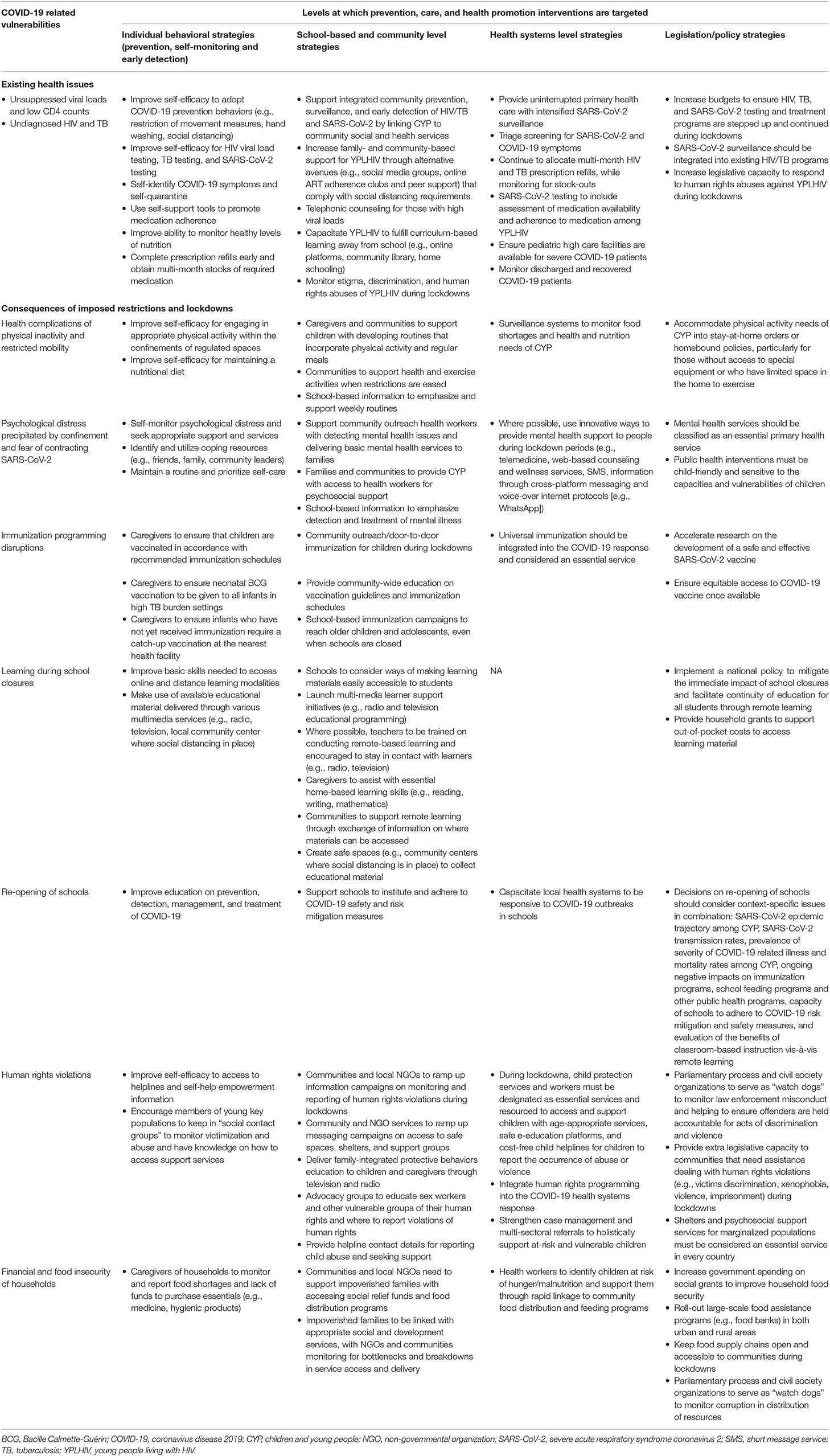

The outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is likely to create unprecedented challenges in Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA), a region where health systems are fragile, socioeconomic inequalities exist, and public health crises of HIV and tuberculosis are rampant. Many countries in this region instituted nationwide public health control measures (e.g., social distancing requirements, stay-at-home orders) to minimize the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and reduce the burden of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on health systems. Although such measures are designed to flatten the curve of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, they often present unique direct and indirect consequences for specific subpopulations. This paper provides an analysis of the implications of COVID-19 and related public health interventions for the well-being of children and young people (CYP)1 living in ESA. We discuss responses that should be implemented to mitigate the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on CYP in the region (for a summary, see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of COVID-19 vulnerabilities and strategies for promoting well-being among children and young people in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Medical Care Needs of Children Living With Unsuppressed Viral Loads, Low CD4 Counts, and Tuberculosis Infections

Previous disease outbreaks have demonstrated that when health systems are overwhelmed, deaths from vaccine-preventable (e.g., tuberculosis) and treatable conditions (e.g., HIV) tend to increase. COVID-19 is likely to adversely affect the many CYP living with HIV in the region, especially those who are not aware that they are HIV positive and those with unsuppressed viral loads and low CD4 counts. Estimates from countries in ESA (e.g., Kenya, South Africa) indicate that up to 37% of HIV positive CYP are living with unsuppressed viral loads (3, 4). Unsuppressed viral loads (and low CD4 counts) increase vulnerability to opportunistic infections, including respiratory-related conditions (5). HIV testing must be paired with SARS-CoV-2 testing to detect the concurrent presence of these viruses in CYP. Those who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 should be monitored closely (if asymptomatic) or treated for COVID-19 symptoms, whereas those who test positive for HIV should immediately be placed on antiretroviral treatment (ART). The latter is particularly important for young people who are at increased risk of being severely affected by COVID-19, including those who have not disclosed their HIV status and those who defer seeking HIV treatment during the pandemic. For CYP on ART, continuation of comprehensive ART is crucial to achieving optimal adherence and viral suppression.

Recently modeled projections indicate that a 6 months disruption of ART could lead to an additional 465,000 AIDS-related deaths in ESA in the next 12 months (6). As countries in the region implement COVID-19-related public health control measures, there is a need to allocate multi-month prescriptions and refills to reduce the frequency of visits to clinical settings and maintain access to HIV prevention services, including condoms and pre-exposure prophylaxis (7). This will ensure that patients have enough treatment during stay-at-home orders and limit unnecessary visits to health care facilities, thereby reducing the risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Children with unsuppressed viral loads who contract SARS-CoV-2 will need to be placed immediately in high care facilities to manage complications from co-infections.

Disruptions to Immunization Programs

Long-term stay-at-home orders that have been implemented to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 have disrupted vaccination campaigns and immunization activities, which increases the risk of children contracting other infectious diseases. Measles immunization campaigns have been delayed in 24 countries and will be canceled in 13 others, with millions of children missing out on immunization activities during the pandemic (8). Many countries in ESA already had sub-optimal rates of immunization for vaccinable diseases (e.g., measles, polio) before the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, 2018 estimates indicate that Angola and Ethiopia accounted for 45% of all infants in ESA who were un- or under-vaccinated for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (9). Immunization activities in this region are likely to be disrupted by social responses to COVID-19 (e.g., reluctance to attend vaccination sessions for fear of exposure) and the effects of public health control measures (e.g., border closures and travel disruptions can impact vaccine accessibility). These conditions raise the risk of sudden outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases occurring when social distancing restrictions are eased. For children who already have a compromised immune system (e.g., those living with HIV), likelihood of mortality from vaccine-preventable conditions (e.g., measles) is higher if immunizations are not received (10).

While acknowledging the importance of initiating measures to minimize the spread of SARS-CoV-2, delivery of immunization services is essential to maintaining the health of children through vaccinations for preventable diseases. Particularly in ESA where health care systems are under-resourced, finding a balance between containing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and continuing immunization programs is critical. Planning is needed to ensure that unvaccinated children are prioritized by immunization initiatives (e.g., large-scale, home-based immunization campaigns) and developing contingency plans to circumvent immunization campaign disruptions caused by homebound orders related to COVID-19.

Physical, Psychological, and Social Consequences of Human Mobility Restrictions

As SARS-CoV-2 rapidly spreads across the world, it is inducing a considerable degree of fear and anxiety among people. Measures that have been implemented to contain the virus, including restrictions on freedom of mobility, limits to physical social contact, and imposed isolation and quarantine, can negatively impact the health and well-being of CYP (11). The consequences of stay-at-home orders are likely to be exacerbated in low-resource countries where financial capacity to support CYP is limited (12).

Stress that is triggered by homebound orders can weaken immune systems of growing children and increase their susceptibility to infections (13). CYP who are forced into sedentary lifestyles are at higher risk of developing non-communicable chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes, hypertension), which is already a growing concern in low-resource contexts such as ESA (14). Because young people living with HIV are more vulnerable to mental illness, especially depression (15), coping with a public health emergency like COVID-19 might compound pre-existing psychological distress.

Restrictions to mobility imposed by lockdowns will make it difficult for CYP living in ESA to access health services. As funding and health care services are scaled up to manage COVID-19 and its psychosocial effects, it is important that essential counseling and social support services remain accessible. Innovative approaches need to be developed and implemented to provide mental health support to CYP during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., telemedicine, virtual peer support, online counseling and wellness services). Where such services are not feasible, community health workers and families need to be supported to care for CYP. Relaxing lockdown restrictions by creating opportunities for CYP to engage in physical activity will improve physical and psychological health.

In ESA, unemployment rates remain relatively high, with young people being disproportionately affected (16). Most of the employable young people in the region rely on the informal sector for income. In countries that were confronted with food insecurity before the pandemic (e.g., Zimbabwe), stringent public health control measures that are now linked to COVID-19 are exacerbating hunger and poverty among young people. It is crucial that governments institute social protection measures to cushion the informal economy and provide food subsidies for those living in poverty.

Impact of School Closures on Health, Safety, and Learning

As a result of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders, many children have experienced a disruption in formal education. Nationwide school closures are likely to have negative implications for the educational experiences of many children, especially those living in ESA where schools lack sufficient infrastructure to support the educational needs of children while stay-at-home orders are enforced. Government-sponsored school nutritional programs (e.g., feeding schemes) are prevalent in many countries in the region (17). Closing schools immediately restricts access to these programs, which many children depend on. Poor nutrition has been associated with worse educational outcomes in children, weakened immune systems, susceptibility to opportunistic infections, and premature mortality (18). During periods of prolonged school closures, there is a need to ensure children continue to have access to food. South Africa recently increased household funding through a child support grant that provides an additional R300 per child and R500 per caregiver each month (19). Similar initiatives are required in other countries in the ESA region.

School closures during times of crisis can heighten children's risk of exploitation, abuse, and violence (20). During homebound restrictions, families and communities need to be vigilant and protect children from harm. Countries may benefit from adopting the seven strategies outlined in the INSPIRE package (21). INSPIRE is designed to assist countries and communities to focus on prevention programs and services that have the greatest potential to reduce violence against children. This package has been successfully used in low- and middle-income countries, including those in ESA. During stay-at-home periods, social and child protection services must be designated as essential services and sufficiently resourced to support children with age-appropriate services, safe e-education platforms, and cost-free child helplines for children to report incidences of abuse or violence. Caregivers also need to be offered guidance on communicating in clear and sensitive language to children about risks, concerns, and protective measures related to SARS-CoV-2 transmission and infection.

Children from many impoverished households in ESA are also likely to fare poorly at homeschooling or distance learning due to challenges accessing electricity, electronic devices (e.g., computers), and the internet. Government and private sector partnerships with schools are needed to provide learners and caregivers with resources to facilitate meaningful remote learning opportunities. Basic Education Ministries should identify ways of supplying learners with printed reading materials through community health workers and community centers that are applying COVID-19 safety measures. Caregivers of children must be given support to implement simple routines that maintain typical eating windows, incorporate time for educational activities (e.g., reading), and include recreational activities that adhere to public health control measures. Teachers should be encouraged to stay in regular contact with learners and caregivers during school closures to ensure that learners understand and can engage with educational material. Teachers also need to be trained to remotely teach children living with disabilities, and caregivers should be given assistance with making distance learning accessible to children with disabilities. In low-income countries, radio and television education broadcasts may be more effective than e-learning (22). Rapidly creating age- and grade-appropriate educational radio and television programs in different languages can support learning during school closures.

There is evidence to suggest that most children who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 have mild symptoms or are low transmitters of the virus (23). As countries consider whether or not to re-open schools, the best interests of children and overall public health should be considered. Decisions need to be based on localized prevalence rates of SARS-CoV-2, the ability of schools to adhere to COVID-19 safety regulations, and an assessment of the benefits of classroom-based instruction vis-à-vis remote learning (24).

Disproportionate Implications of Violence, Human Rights Abuses, and Limits on Access to Services for Marginalized Groups

The COVID-19 pandemic is accentuating social-structural inequalities, which tend to disproportionately affect marginalized people and those living in financially precarious situations (25). As countries implement public health policies to minimize transmission of SARS-CoV-2, young girls and women, people who identify as LGBTI, people who engage in sex work, informal traders, and street children are more likely to be targets of police brutality (26, 27). There have also been reports of misuse of emergency powers by governments to target marginalized and vulnerable populations (27). For example, a number of LGBTI shelter residents in Uganda were falsely arrested and incarcerated for approximately 50 days on the pretext of violating COVID-19 lockdown regulations (28). Young sex workers may have fewer avenues to protect themselves and are more prone to being victims of violence from police and other sex workers (29). Some younger sex workers may have children, which might increase their risk-taking propensity as they search for income and food to support their families.

Access to contraceptives is also a challenge with the imposition of COVID-19 stay-at-home requirements. Restricted mobility, reduced availability of public transportation, and closures of non-essential retail outlets and youth centers limits the capacity of young people to access contraceptives. Shortages of these commodities may precipitate risky sexual practices and unintended pregnancies (30), both of which were already long-standing issues in ESA before lockdowns were imposed in response to COVID-19 (31, 32). For young people living with HIV, condom shortages may increase the likelihood of onward HIV transmission. Further, fear associated with contracting SARS-CoV-2 is preventing individuals from attending public clinics (33). Closure of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and community centers also places additional strain on the homeless and street children who ordinarily rely on those sources for food, clothing, and basic hygiene products.

As COVID-19 stay-at-home orders confine people to their homes, some young women may not have the opportunity to distance themselves from perpetrators of abuse or seek in-person support and health services for experienced abuse. Countries in ESA (e.g., Kenya, South Africa) have reported increases in the incidence of gender-based violence since COVID-19 homebound orders began (34, 35). Periods of confinement or lockdown accentuate the need to reach the most vulnerable groups with social safety nets. While it may be difficult to reach vulnerable populations when country-level COVID-19 public health control measures are in place, civil society organizations and NGOs need to actively monitor incidents of human rights violations by law enforcement and military personnel who enforce stay-at-home orders and social distancing measures. More broadly, civil society organizations ought to be involved in mitigating unintended consequences of the pandemic, including gender-based violence, discrimination, and food insecurity.

NGOs with established networks are more likely to have access to marginalized populations and should act as conduits between recipients and donors that offer shelter, access to food, and other essential services. Retail shops and youth centers that provide sexual and reproductive health services should be classified as essential services to ensure continued provision of contraceptives and medical treatment to young people. Upholding the rights of all citizens, including marginalized groups, should be a cornerstone of the COVID-19 response. Legal and psychosocial support services should also be accessible to CYP who may require “crisis response” interventions.

COVID-19 has provoked social stigma and discriminatory behaviors (36). People who are already living with a stigmatized health condition (e.g., HIV) could face dual stigmas if they contract SARS-CoV-2. Stigmatization can deter health-seeking behaviors and contribute to more severe health problems (37). Local broadcasters ought to regularly feature medical experts and health scientists to support the dissemination of accurate information about individual and group vulnerability to COVID-19, safe prevention and health promotion measures, and effective treatment approaches. With so many sources of information available to CYP, government-supported initiatives are needed to ensure that the public is informed about where to acquire credible information about COVID-19. Caregivers must be empowered to provide accurate, age-appropriate information to children about stigma and supervise exposure of CYP to information about COVID-19. Innovative, ongoing support services are also needed to assist CYP who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 or recovering from COVID-19 to cope with stigma and its psychosocial consequences.

Food Insecurity in Families and Communities

In ESA countries that have been affected by COVID-19, public health measures designed to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 has stalled economies and severely impacted the livelihood of people. Many people in ESA are employed informally, have low-paid contract positions, or receive hourly wages. The abrupt closure of many businesses (formal and informal) has resulted in a sudden loss of income for numerous people, with household food and health security being threatened. The World Food Programme (38) has warned that more than 200 million people could be pushed into acute food insecurity by the COVID-19 pandemic, many of which will be residents of ESA countries. ESA also has an immense number of children orphaned by AIDS Double orphans, in particular, are likely to end up living on the street, in youth- and child-headed households, or with extended family members who are likely to experience further financial strain because of the increased dependency ratio (39).

Food insecurity will limit the availability of nutritional food choices, which could detract from optimal immune system functioning and reduce the effectiveness of ART among those who are living with HIV. Addressing the impact of income loss in lower-income households through allocation of cash transfers can ease the burden of food insecurity. For example, South Africa has implemented the COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress grant that is paid to individuals who are currently unemployed and do not receive any other form of social grant. While cash transfers can assist many low-income households, this may not be sufficient to avert food insecurity. Large-scale roll out of food assistance programs (e.g., food banks) in both urban and rural areas is needed to supplement cash transfers, ensure access to life-sustaining food, and prevent social unrest and hunger riots. Food security at home could be improved through home-delivered meals facilitated by local organizations (e.g., NGOs, municipalities). School feeding programs need to be reintroduced, with the option of community sites becoming key distribution points that are accompanied by screening for COVID-19 symptoms, follow-up, and monitoring of children from affected households. Therapeutic nutrition ought to be provided to children who are malnourished or receiving ART. In the long-term, providing lower-income households with direct livelihood support through financed projects to develop small scale livestock and agricultural activities will both support child nutrition and mitigate the strain of food shortages and increases in food prices.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted extraordinary measures around the world to slow the pace of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and minimize the public health consequences of the disease. Though necessary, some of these measures may have direct and indirect implications for specific subpopulations. Public health control orders should be cognizant of the unique needs of CYP, particularly those with underlying health conditions and who live in impoverished conditions. Countries in ESA will need to balance responding directly to the COVID-19 pandemic with upholding human rights and supporting CYP, particularly more vulnerable groups (e.g., children living with HIV, young women), to ensure food, education, and counseling services are available during government-enforced movement restrictions. More generally, the COVID-19 public health crisis highlights the importance of providing fiscal support to improve health systems and other institutional capacities in ESA, such as education and national security.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

KG, RC, and PN conceptualized the manuscript. RC and PN led the writing of the manuscript. KG, RC, PN, RA, and LH provided critical revisions, edited, and finalized the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) and the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) for supporting this work.

Footnotes

1. ^Children and young people is an inclusive term that refers to any person aged 24 years or younger (1, 2).

References

1. World Health Organization. Guidance on Ethical Considerations in Planning and Reviewing Research Studies on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Adolescents. (2018). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/273792/9789241508414-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed May 3, 2020).

2. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1989). Available online at: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf (accessed May 16, 2020).

3. Boerma RS, Boender TS, Bussink AP, Calis JC, Bertagnolio S, Rinke de Wit TF, et al. Suboptimal viral suppression rates among HIV-infected children in low-and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. (2016) 63:1645–54. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw645

4. Njuguna I, Neary J, Mburu C, Black D, Beima-Sofie K, Wagner AD, et al. Clinic-level and individual-level factors that influence HIV viral suppression in adolescents and young adults: a national survey in Kenya. AIDS. (2020) 34:1065–74. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002538

5. Anígilájé EA, Aderibigbe SA, Adeoti AO, Nweke NO. Tuberculosis, before and after antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children in Nigeria: what are the risk factors? PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0156177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156177

6. Jewell BL, Mudimu E, Stover J, ten Brink D, Phillips AN, Smith JA, et al. Potential effects of disruption to HIV programs in sub-Saharan Africa caused by COVID-19: results from multiple mathematical models. Lancet. (2020). doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30211-3. [Epub ahead of print].

7. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Thai Hospitals to Provide Three- to Six-Month Supplies of Antiretroviral Therapy. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2020/march/20200325_thailand (accessed March 12, 2020).

8. United Nations. COVID-19 Isolation Threatens Life-Saving Vaccinations for Millions of Children Globally. (2020). Available online at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/04/1061612 (accessed April 21, 2020).

9. United Nations Children's Fund. Immunization Regional Snapshot 2018: Eastern and Southern Africa. (2018). Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Immunization-regional-snapshots-ESAR-2020.pdf (accessed April 4, 2020).

10. Mutsaerts EA, Nunes MC, van Rijswijk MN, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Grobbee DE, Madhi SA. Safety and immunogenicity of measles vaccination in HIV-infected and HIV-exposed uninfected children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. (2018) 1:28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.06.002

11. World Vision. Children's Voices in Times of COVID-19: Continued Child Activism in the Face of Personal Challenges. (2020). Available online at: https://www.wvi.org/publications/report/child-participation/childrens-voices-times-covid-19-continued-child-activism (accessed April 13, 2020).

12. Madhi SA, Gray GE, Ismail N, Izu A, Mendelson M, Cassim N, et al. COVID-19 lockdowns in low- and middle-income countries: success against COVID-19 at the price of greater costs. S Afr Med J. (2020) 110:724–6. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i8.15055

13. Kołodziej J. Effects of stress on HIV infection progression. HIV AIDS Rev. (2016) 15:13–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hivar.2015.07.003

14. Vancampfort D, Mugisha J, Richards J, De Hert M, Lazzarotto AR, Schuch FB, et al. Dropout from physical activity interventions in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care. (2017) 29:636–43. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1248347

15. Woollett N, Cluver L, Bandeira M, Brahmbhatt H. Identifying risks for mental health problems in HIV positive adolescents accessing HIV treatment in Johannesburg. Child Adol Psych Men. (2017) 29:11–26. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2017.1283320

16. Chigunta F, Schnurr J, James-Wilson D, Torres V. Being “Real” About Youth Entrepreneurship in Eastern and Southern Africa: Implications for Adults, Institutions and Sector Structures. Geneva: International Labour Organization (2005).

17. Lesley D, Alice W, Carmen B, Donald B. Global School Feeding Sourcebook: Lessons From 14 Countries. London: Imperial College Press (2016).

18. United Nations Development Programme. Africa Human Development Report 2012: Towards a Food Secure Future. (2012). Available online at: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/240/ahdr_2012.pdf (accessed April 14, 2020).

19. South African Government. President Cyril Ramaphosa: Additional Coronavirus COVID-19 economic and social relief measures. (2020). Available online at: https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-additional-coronavirus-covid-19-economic-and-social-relief (accessed April 14, 2020).

20. United Nations Children's Fund. Don't Let Children be the Hidden Victims of COVID-19 Pandemic. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/dont-let-children-be-hidden-victims-covid-19-pandemic (accessed April 15, 2020).

21. World Health Organization. INSPIRE Handbook: Action for Implementing the Seven Strategies for Ending Violence Against Children. Geneva: World Health Organization (2018).

22. United Nations Children's Fund. Radio Programs Help Keep Children Learning in Lake Chad Crisis. (2017). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/media_96644.html (accessed May 7, 2020).

23. Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatrica. (2020) 109:1088–95. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270

24. United Nations Children's Fund. Framework for Reopening Schools. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/68366/file/Framework-for-reopening-schools-2020.pdf (accessed May 8, 2020).

25. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Sex Workers Must Not be Left Behind in the Response to COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2020/april/20200408_sex-workers-covid-19 (accessed April 23, 2020).

26. Platt L, Elmes J, Stevenson L, Hol V, Rolles S, Stuart R. Sex workers must not be forgotten in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. (2020) 396: 9–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31033-3

27. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. UNAIDS Condemns Misuse and Abuse of Emergency Powers to Target Marginalized and Vulnerable Populations. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2020/april/20200409_laws-covid19 (accessed April 22, 2020).

28. McCool A. Court Orders Release of LGBT+ Ugandans Arrested for 'Risking Spreading Coronavirus'. (2020). Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-uganda-lgbt/court-orders-release-of-jailed-lgbt-ugandans-after-coronavirus-charges-dropped-idUSKBN22U2DO (accessed May 6, 2020).

29. Global Network of Sex Work Projects. Policy Brief: Young Sex Workers. (2016). Available online at: https://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/Policy%20Brief%20Young%20Sex%20Workers%20-%20NSWP,%202016.pdf (accessed April 24, 2020).

30. United Nations Population Fund. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-Based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/COVID-19_impact_brief_for_UNFPA_24_April_2020_1.pdf (accessed April 26, 2020).

31. Schaefer R, Gregson S, Benedikt C. Widespread changes in sexual behaviour in eastern and southern Africa: challenges to achieving global HIV targets? Longitudinal analyses of nationally representative surveys. J Int Aids Soc. (2019) 22:e25329. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25329

32. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Situational Analysis on Early and Unintended Pregnancy in Eastern and Southern Africa. (2018). Available online at: https://www.youngpeopletoday.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Unesco_EUP_Report_2018_LOW_RES.pdf (accessed April 25, 2020).

33. African News Agency. High Percentage of HIV-Positive People Skipping Treatment Over Covid-19 Fears. (2020). Available online at: https://www.africannewsagency.com/news-politics/HIV-positive-people-in-SA-skipping-treatment-over-Covid-19-fears-24770911 (accessed April 19, 2020).

34. John N, Casey SE, Carino G, McGovern T. Lessons never learned: crisis and gender-based violence. Dev World Bioeth. (2020) 20:65–8. doi: 10.1111/dewb.12261

35. Mutavati A, Zaman M. Fighting the ‘Shadow Pandemic’ of Violence Against Women & Children During COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.un.org/africarenewal/web-features/coronavirus/fighting-%E2%80%98shadow-pandemic%E2%80%99-violence-against-women-children-during-covid-19 (accessed April 27, 2020).

36. United Nations Children's Fund. Social Stigma Associated With COVID-19. (2020). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/media/65931/file/Social%20stigma%20associated%20with%20the%20coronavirus%20disease%202019%20(COVID-19).pdf (accessed May 14, 2020).

37. Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, van Brakel W, Simbayi LC, Barré I, et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. (2019) 17:31. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3

38. World Food Programme. COVID-19 Will Double Number of People Facing Food Crises Unless Swift Action is Taken. (2020). Available online at: https://www.wfp.org/news/covid-19-will-double-number-people-facing-food-crises-unless-swift-action-taken (accessed May 15, 2020).

39. United Nations Children's Fund. Africa's Orphaned Generation. (2003). Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/sowc06/pdfs/africas_orphans.pdf (accessed May 19, 2020).

Keywords: COVID-19, Eastern and Southern Africa, health, well-being, children, young people

Citation: Govender K, Cowden RG, Nyamaruze P, Armstrong RM and Hatane L (2020) Beyond the Disease: Contextualized Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Children and Young People Living in Eastern and Southern Africa. Front. Public Health 8:504. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00504

Received: 02 June 2020; Accepted: 06 August 2020;

Published: 19 October 2020.

Edited by:

Marie Leiner, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Luis Alvaro Moreno Espinoza, The College of Chihuahua, MexicoSatinder Aneja, Sharda University, India

Copyright © 2020 Govender, Cowden, Nyamaruze, Armstrong and Hatane. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kaymarlin Govender, Z292ZW5kZXJrMkB1a3puLmFjLnph

Kaymarlin Govender

Kaymarlin Govender Richard Gregory Cowden

Richard Gregory Cowden Patrick Nyamaruze

Patrick Nyamaruze Russell Murray Armstrong1

Russell Murray Armstrong1 Luann Hatane

Luann Hatane