- 1Doctoral Program in Public Health, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

- 2Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University, Denpasar, Indonesia

- 3Department of Environmental Health, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia

There is a continuous increase in the number of COVID-19 cases in Indonesia. To control its spread, the government has implemented several strategies, such as policies associated with large-scale social restrictions (Indonesian: Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar or PSBB). The purpose of this study is to determine the variables that influence attitudes toward PSBB policies in Indonesia. This is a cross-sectional study with data obtained from 856 respondents from all provinces in Indonesia using the partial least squares and structural equation model (PLS-SEM). A total of 23 indicators were used to examine these policies, which were grouped into five variables: benefits of the PSBB (5 indicators), positive perception (5 indicators), negative perception (3 indicators), threatened perceptions of COVID-19 (5 indicators), and attitude toward the PSBB policy (5 indicators). The model explains over 50% of attitudes exhibited toward PSBB policy implementation and how it is influenced by the perceived benefits, negative and positive perceptions as well as the threat associated with COVID-19. The policy of stay at home, physical distancing, and always using face masks needs to be continued for the public to have a supportive attitude of the PSBB policy in preventing the transmission of COVID-19.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which initially started in Wuhan, China, has spread to over 200 countries worldwide. On August 12, 2020, there are 20,162,474 cases were reported, with ~737,417 deaths (1–4). In Indonesia, according to government data on August 12, 2020, there were 130,718 cases and 5,903 deaths (5).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the COVID-19 virus can be transmitted from an infected person to others through droplets when coughing or sneezing as well as by touching objects infected with the virus (6). The WHO recommends the mandatory use of face masks (7, 8), reducing crowds by shutting down workplaces, schools, places of worship, and other forms of social gathering. Furthermore, physical distancing needs to be maintained by staying at a distance of more than 2 m away from other people (9). Regular washing of hands, disinfecting frequently touched surfaces, and desisting from touching the mouth, nose, and eyes are also recommended (10). However, social distancing was found to be less accepted by the public than other means of control, as evidenced by a continuous increase in transmission at the local level and in communities outside the home. The Indonesian government has enacted regulation No. 21 of 2020 concerning large-scale social restrictions (PSBB) to help increase control over the spread of COVID-19.

These restrictions include closing workplaces, schools, public transportation, and socio-cultural, religious, and community activities in public places or facilities (11). The criteria for the application of PSBB are the significant and rapid increase in the number of cases and deaths from COVID-19 disease as well as epidemiological links with similar incidents in other regions or countries.

All regions in Indonesia are encouraged to implement physical and social distancing policies to prevent the spread of this virus, which is currently at the community transmission level (12, 13). Citizens in almost all the provinces in Indonesia are at risk of being infected with this virus; therefore, they are encouraged to restrict their activities.

Unfortunately, public awareness to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 is still very low; which is demonstrated by the presence of people who actively live their lives in public places. Many studies have been conducted on the attitudes and perceptions of health workers (14, 15). However, there has not been any published research regarding people's perceptions and attitudes toward PSBB policy. This study adopted a theoretical framework from the research carried out in Kenya on health workers' perceptions and attitudes toward national health care (16) to create PSBB policies. Therefore, through structural equation modeling analysis, the right variables are formed to support these policies.

Methodology

Conceptual Model

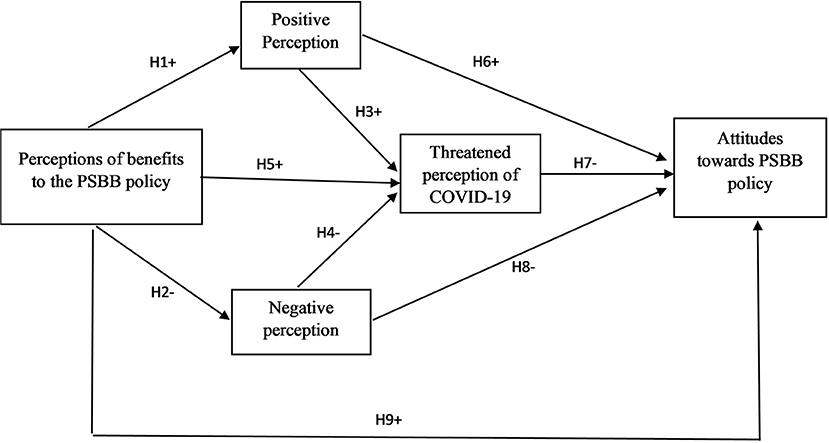

The theoretical model adopted in this study was associated with the perceptions and attitudes of health workers in allocating national nursing resources (16) as well as perceptions and attitudes related to tourism (17, 18). The hypothesized model comprised of five latent constructs on the PSBB policy is influenced by the benefits, positive perception, negative perception, perceived threat of COVID-19, and attitude toward PSBB policy, as shown in Figure 1. The path direction represents the positive (+) and negative (–) effects of the relationship. This study examines the suitability of the model and hypothesis with SEM-PLS.

Study Design and Data Collection

This is a cross-sectional study based on a web-based survey used to measure the five variables on attitudes toward PSBB policy influenced by the benefits, positive perception, negative perception, and perceived threat of COVID-19. Questionnaires related to the perceptions of health workers and mechanisms for national nursing resources for COVID-19 prevention were developed by the Ministry of Health (14, 16). Respondents answered these questions using a five-point Likert scale: 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neutral), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). This tool was used because of its simplicity and ease of use. Each question item was discussed with experts to obtain the necessary suggestions and ways to further prevent the virus. The online questionnaire was tested for validity and reliability by 50 respondents, which led to a total of five invalid questions. Data were anonymously collected from respondents in 34 provinces through an online survey (19) using Google forms. It was also distributed by the Indonesian health professional organizations through WhatsApp from May 1 to May 14, 2020.

Respondent

The respondents who participated in the online survey were above 17 years old and had resided in Indonesia for more than 6 months. They provided informed consent before filling out the questionnaire and were paid by the sponsor. A total of 868 people filled out the data, with 856 eligible responses.

Several steps were taken to prevent missing data (20). First, each respondent received an explanation of the purpose of the study by filling out documents associated with their informed consent. Second, in the web-based questionnaire survey, an automatic system was used to fill out the data, and it was discontinued when blank. Third, respondents' data were collected anonymously to ensure confidentiality. Listwise deletion was used when data were missing. Incomplete data that did not meet the requirements were not used in this study.

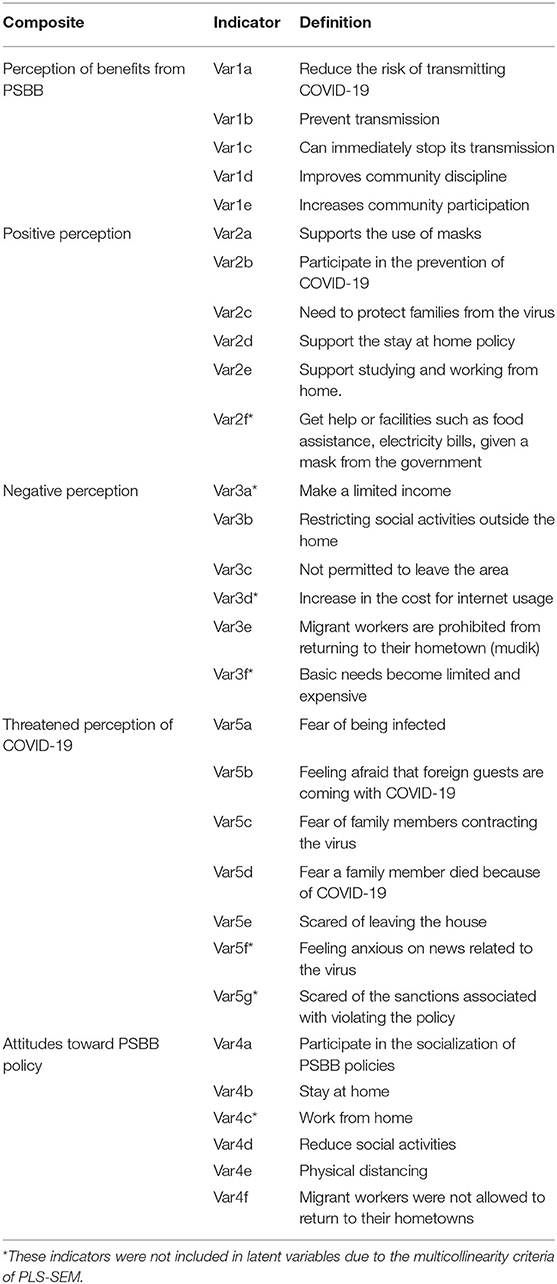

This study used a partial least squares (PLS-SEM) composite scheme with the SmartPLS 3.0 software to analyze four perception variables on attitudes toward PSBB policy consisting of 30 indicators. Partial least squares were used to create a structural model with the ability to map paths with many variables simultaneously. This analysis was used to predict the multicollinearity among variables (21). Table 1 shows the theoretical models proposed in this study, which examines the effect of PSBB policy influenced by the benefits, positive perception, negative perception, and perceived threat of COVID-19.

Measurement of Variables

This study consists of five variables measuring 30 indicators using a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neutral), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). The following constructs are part of this model:

The attitude toward the PSBB policy is the dependent variable, which means that the respondent's attitude is carried out in daily life. It is measured by six indicators, consisting of those who participate in the socialization of PSBB policies: stay at home, work from home, reduce social activities, physical distancing, and migrant workers who do not return to their hometown or village during or before major holidays (mudik).

The perception of benefits from the PSBB policy is associated with assessing the policy implemented by the government that benefits the community. It consists of six indicators that reduce the risk of transmitting COVID-19 and prevent its spread, thereby improving community discipline and participation.

Positive perception is associated with respondent's assessments of the PSBB policy, which is in line with the expectations of its regulations. It comprises of six indicators: support the use of masks, participate in preventing COVID-19, protecting families from the virus, not leaving the house, studying and working from home, and getting help or convenience such as food and bills assistance, and masks from the government.

Negative perception is the respondent's assessment of PSBB policies that are not in line with their expectations. It consists of six indicators: receiving limited income, restricting social activities outside the home, not permitted to leave the area, increasing cost for internet usage, migrant workers are prohibited from returning to their hometown (mudik), and basic needs become limited and expensive.

Threatened perception of COVID-19 frightens respondents. It consists of seven indicators, namely fear of being infected, increased by foreign guests, family members contracting the virus, fear of the death of a family, scared of leaving the house, feeling anxious about news related to the virus, and scared of the sanctions.

Statistical Procedure

Structural equation models are analyzed in two stages: measurement and structural model analyses (22). The first stage describes the model being measured by connecting the constructs and indicators according to the theory. After obtaining the quality of the measured data, a structural model is used to determine the relationship between the construction or hypothesis model. This is carried out to make valid and reliable measurement scales to prove the structural model hypothesis. This study used the Smart-PLS 3.2.7. software.

Ethical Approval

The study's ethical clearance was obtained from the Public Health Faculty, Universitas Indonesia (No. 198/UN2.F10. D11/PPM.00.02/2020). This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the recommendations of those committees with written informed consent from all participants.

Results

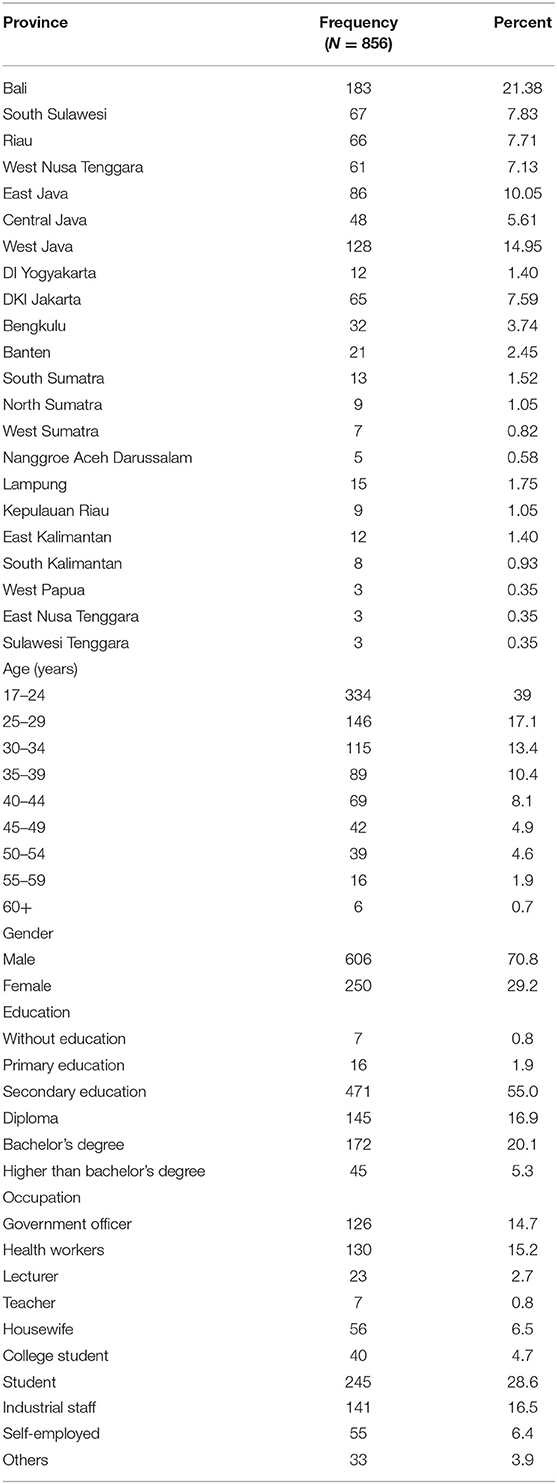

The respondents in the provinces were distributed as follows: Bali (21.3%), West Java (14.9%), East Java (10%), South Sulawesi (7.8%), Riau (7.7%), and Central Java (5.6%) (Table 2). The Java-Bali region had a relatively high trend of increasing cases compared to other provinces, due to the population density and higher mobility. The demographic characteristics of the 856 respondents were aged 17–24 years (39%). The highest gender distribution, education level, and employment type were male (70.8%), secondary education (55%), and students (28.6%), respectively. Furthermore, the health workers and government officers were 15.2 and 14.7%, respectively.

Measurement Model

Composite Mode A

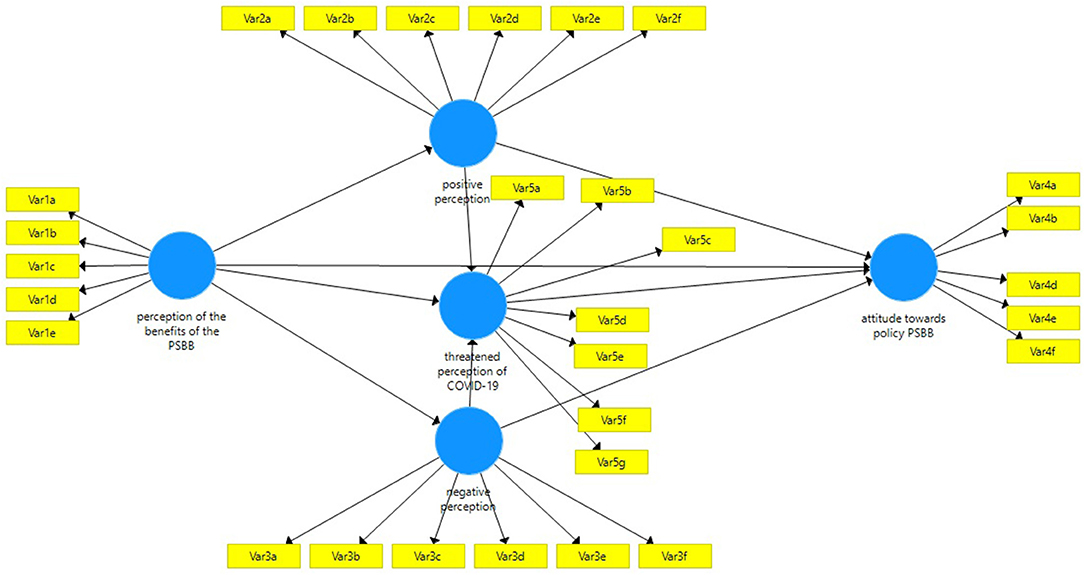

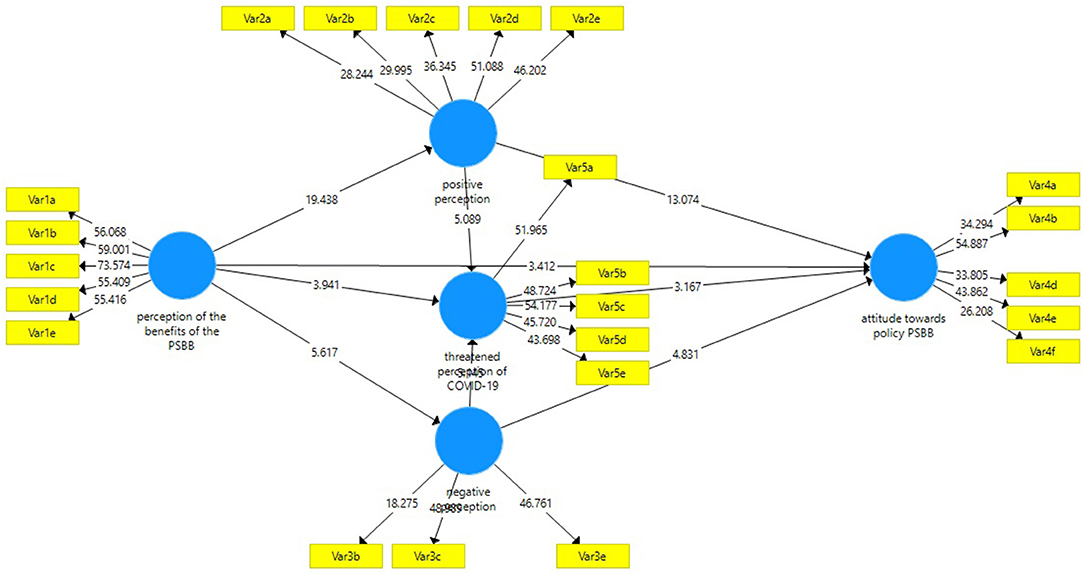

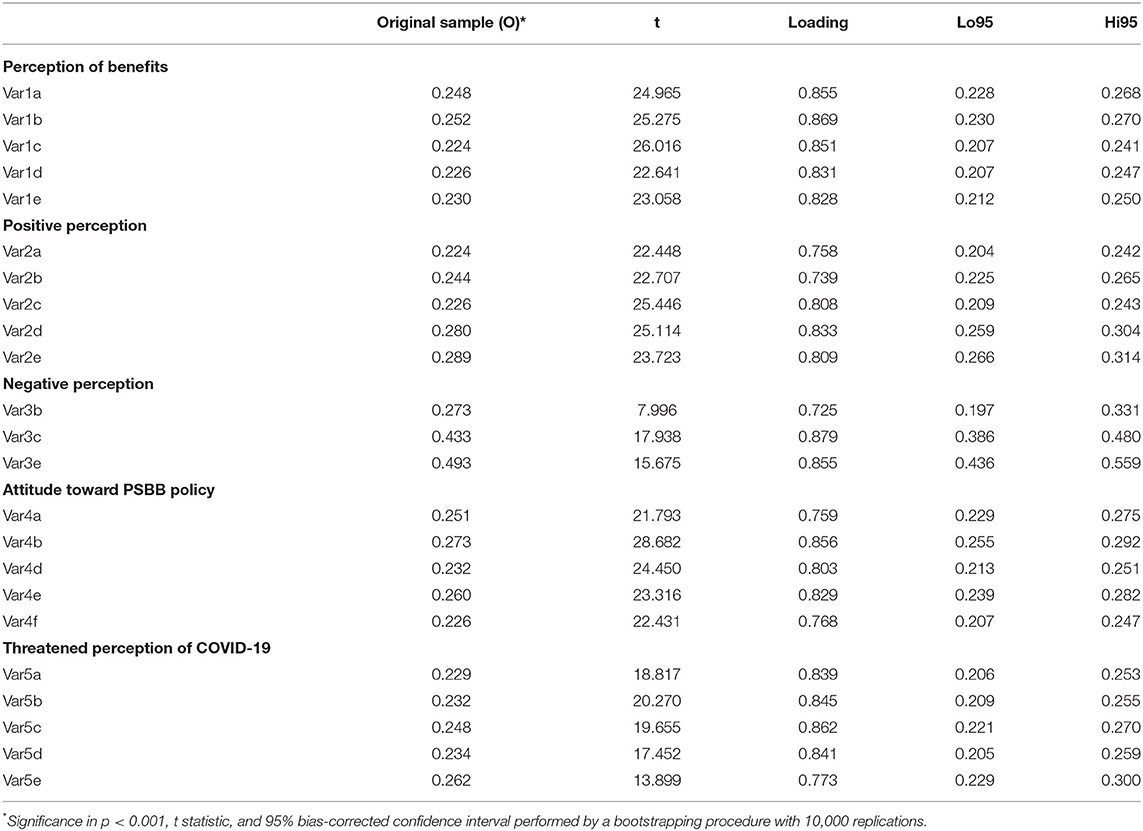

The composite measurement model in mode A was assessed in terms of individual item reliability, discriminant validity, convergent validity, and construct reliability, which were analyzed using the through-loading factors shown in Figure 2.

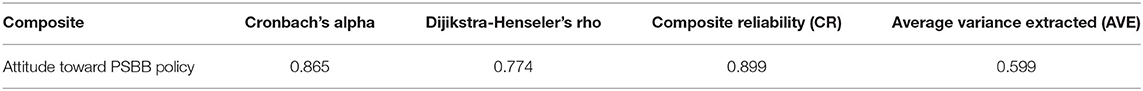

Composite reliability is more precise than internal consistency. It can be used with PLS-SEM to accommodate different loading indicators. Validity assessment was carried out by calculating convergent and discriminant validities. Table 3 illustrates the cutoff value of 0.7 for 3 measurements, namely Cronbach's alpha, Dijkstra-Henseler's rho coefficients, and composite reliability. The third convergent validity is proven because each construct's average variance extracted (AVE) is higher than 0.5. Table 3 shows that the measurement model fits the criteria.

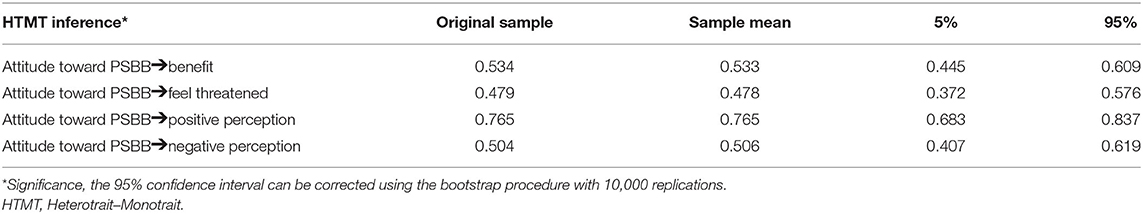

Table 4 presents the results of discriminant validity through the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) correlation ratio. All constructs are in accordance with the discriminant validity because the confidence interval does not contain a zero value. This means that each variable is different from one another.

The data examined above in the measurement model show that the construct is reliable and valid.

Composite Mode B

The composite measurement model in mode B was assessed in terms of the collinearity between the indicators, significance, and relevance of the external weights. First, this was carried out by removing the indicator when it exceeded the value of the impact factor variance (VIF = 3). As a result of this process, only the indicators shown in Table 1 are not collinear. Second, the relevance of weights was analyzed, as shown in Figure 3, with the relevance of indicators in construction for latent variables. Finally, 10,000 subsamples were used to start bootstrapping, and to determine the ability to the outside weight significantly different from zero. Indicators with weights were insignificant, with a significant loading of 0.50 above the relevant values, as shown in Table 5.

Structural Model

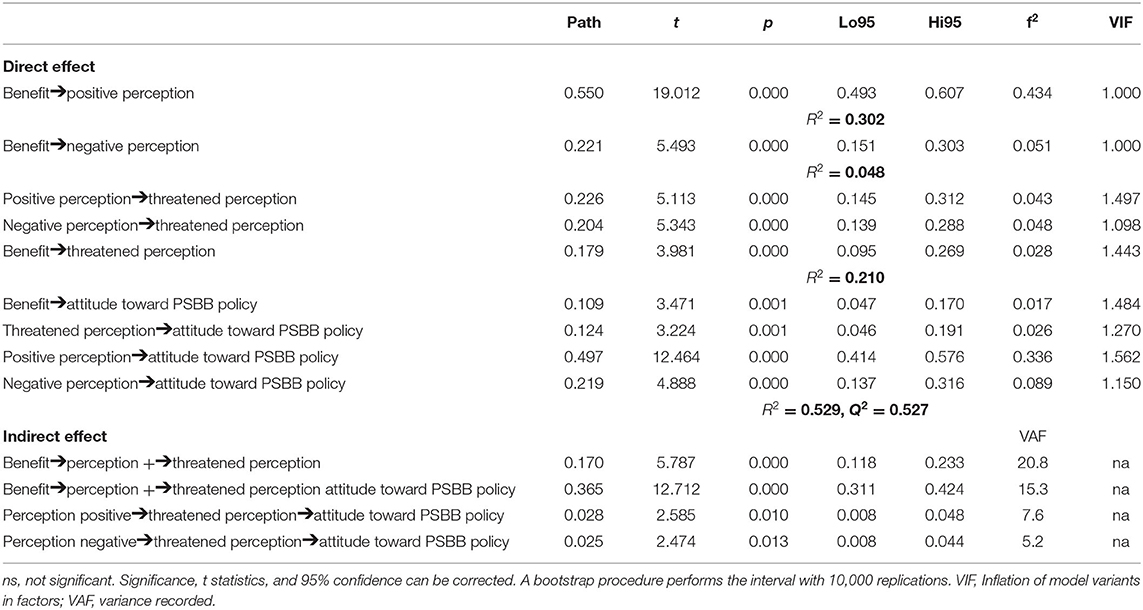

After verifying the appropriate values of the construction measurements, an assessment of the structural model was carried out using 10,000 resampling bootstraps. The path coefficients and the significance level of their 10,000 resampling bootstraps are reported in Table 6 and Figure 3. Furthermore, Table 6 also shows that the VIF construction ranges from 1,000 to 1,700, indicating that there is no collinearity between variables. This study also assesses quality by examining whether the predictive relevance of the whole model has a Q2-value above zero; therefore, it fits in the model predictions. The coefficient of determination (R2) also exceeds 0.1 for endogenous latent variables. Therefore, the construct has an acceptable predictive power quality.

Table 6 shows that the PSBB policy influenced by the benefits, positive, negative, and perceived threat of COVID-19 directly influence community attitudes (p values <0.001 and 0.001). Furthermore, each variable has a positive relationship with attitude, and the indirect effect can be seen from the value of VAF, which indicates that the proportion mediated by the total effect of feeling threatened through negative perception is 7.6%, as shown in the indirect effect in Table 6. This model explains that the benefits, positive, and negative perceptions influence 52.9% of attitudes toward PSBB policy, and the perceived threat of COVID-19.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study (23), PLS-SEM was used to explore the determinant relationships of perceptions and attitudes toward COVID-19 policy in Indonesia. The general population in several provinces in Indonesia were used to represent the conditions in each region. The PSBB policy is not carried out simultaneously in all regions, although all of them have the potential risk of COVID-19 transmission.

The study analyzed a total of five variables with 30 indicators that influence attitudes toward the policies of PSBB. After analysis using PLS-SEM, 23 indicators were obtained. This model explains that attitudes toward PSBB policy are influenced by the benefits, positive and negative perceptions, and perceived threat of COVID-19.

Policymakers need to understand how to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 as opening public access to infrastructures without considering epidemiological studies can lead to rapid transmission (24). This study describes the attitudes of the community in supporting large-scale social restriction policies carried out in Indonesia. A positive attitude toward this policy causes the community to comply with the regulations willingly and understand the benefits.

Most of the survey respondents were located on Java Island. The distribution of respondents does not represent all provinces in Indonesia; however, Java Island is densely populated, and high population density is one of the risks in the spread of COVID-19 (25). In particular, the challenges are greater in limiting population mobility and social distancing (26). Studies in China also show that people infected with COVID-19 tend to be in densely populated areas (27). A study in Brazil also found that air transportation, population density, and temperature affect the spread of COVID-19 (28).

Most of the respondents in the survey were male and aged 17–24 years. The PSBB policy encouraged school closure and home study through electronic media and online applications. Students' perceptions of the benefits and positive attitude toward PSBB tend to influence their compliance with PSBB policies. Efforts are needed to increase student awareness in preventing the transmission of COVID-19 (29). School closure policies must also be supported by strict social distancing policies (11).

Through a cross-sectional approach, PLS-SEM analysis can be carried out quickly in the general population. This model is designed to determine the respondent's attitude toward the PSBB policy at a specific time. However, it is necessary to carry out further research with a longitudinal approach to determine the comparison of changes in people's attitudes toward the PSBB policy according to the observation period.

The community's attitude as a dependent variable is associated with participating in socializing PSBB, staying at home, reducing social activities, maintaining a safe distance from others, and migrant workers not returning to their hometown. This is consistent with the WHO recommendation to prevent transmission of COVID-19 on staying at home and maintaining a safe distance of more than 2 m (30). These measures aim to stop the spread of the virus, which is transmitted from an infected person to another through droplets when coughing (31–33).

The city of Wuhan in China was locked down to prevent the rapid transmission of the virus (34). This policy was implemented under strict action, discipline, and punishment for violators, and food was provided for the population. However, in Indonesia, restrictions were placed on community activities such as schools, workplaces, and religious places, with access to markets and population logistics. The government also failed to cover the daily needs of the population and hopes that the transmission rate will be reduced through the PSBB policy.

The PSBB policy reduces the risk of COVID-19 transmission by preventing its spread and stopping its transmission through increased community discipline and involvement. The government has supported socialization through electronic platforms and social media, with teachers and community leaders providing adequate information on the benefits of the PSBB policy. It is expected that the public complies with this regulation due to the increase in public awareness.

Furthermore, increased understanding of the community causes positive attitudes such as supporting the use of masks, wanting to protect families from contracting the virus, supporting the idea of not leaving the house as well as learning, and working from home, and participating in the prevention of COVID-19 (35–37). Health education needs to be given to vulnerable populations infected with COVID-19, such as the elderly (38, 39) used to avoid stress (40). The use of masks is an easy, cheap, and effective way to prevent transmission (41); therefore, the WHO recommends its usage (42–44).

The negative perceptions toward the PSBB policy are limited social activities outside the home and not being allowed to leave the area or town. Therefore, traders, construction, and factory workers lost their income negatively affecting their socioeconomic status. Furthermore, those who have family outside their area were also prohibited from traveling. This makes the population uncomfortable with the PSBB policy, thereby leading to anxiety, lack of sleep, depression (16–28%), and stress (8%) (45).

The perception of being threatened with COVID-19 consists of a feeling of fear of being exposed to the virus, foreign guests coming into the country infected, and fear of leaving the house (46–48). It is also associated with the fear of family members being infected with the virus and the possibility of death. These perceptions encourage people to take the necessary preventive steps not leaving the house and adhering to the government's recommendation to conduct a PSBB.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this research were determined by measuring the benefits, positive, negative, and perceived threat of COVID-19 in accordance with the use of PSBB. These perceptions can influence respondents' attitudes toward the PSBB policy. This model is usually used in social research in tourism as well as in the health sector (16–18, 49).

The PLS-SEM was chosen for component-based social research with formative construct properties. This approach is variant based and has the ability to estimate composites and factors (50, 51). It is also useful to predict the dependent variable within a large number of independent variables. In addition, through this approach, an appropriate structural equation model can be made with variables related to attitudes toward PSBB policy.

This study is limited by the use of online surveys, which are provided by the general public rather than specific targets. However, with the general public, there are various advantages, such as the ability to reach all groups in a broad range, depending on the PSBB policy. However, this situation was not uniform in all places, which had a non-concurrent implementation process.

Policy Implications and Future Research

This study is useful for policymakers, especially for health interventions and health education programs in efforts to control COVID-19. The PSBB policy with restrictions on community activities and entering and leaving the area. Schools and workplaces are closed, but learning activities can be carried out online. The PSBB is also supported by tracking and finding people who are exposed (52). Efforts to control COVID-19 in other countries by limiting community activities at the beginning of the pandemic, such as lockdown implementations, have proven effective in reducing the transmission of the virus (53, 54). However, this approach has been reported to have an impact on psychological and economic factors in society (55–57).

The results of this study have implications for controlling COVID-19 in various regions, particularly in Indonesia. The public needs to obtain adequate educational awareness on the perception and benefits of the PSBB policy, which can positively impact the public's attitudes to abide by the policy. This study contributes to the addition of academic literature by applying the PLS-SEM to explore the relationship between attitudes toward PSBB and COVID-19 spread. Subsequent studies can be conducted in certain areas to control numerous factors by the timing of a particular PSBB implementation, to ensure that the impact is clear when compared to many regions with a non-concurrent PSBB period.

Conclusion

The PSBB policy needed to obtain adequate attention from the community to prevent the rapid transmission of COVID-19 in Indonesia. Furthermore, the attitude of those that support this policy tends to affect the successful implementation of this program. This model explains that 52.9% of attitudes toward PSBB policies are influenced by perceptions of the benefits of the PSBB policy, positive perceptions, negative perceptions, and perceptions of the threat of COVID-19. The policy of not leaving the house, keeping a safe distance, and always using face masks needs to be continued for the public to support the PSBB policy in preventing further transmission.

Data Availability Statement

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Sang Gede Purnama, c2FuZ3B1cm5hbWFAdW51ZC5hYy5pZA==.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Public Health Faculty, Universitas Indonesia. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

SP developed a draft proposal, study design, collected data, and revised the results. Meanwhile, the DS participants made study drafts, researched designs, collected data, and revised the results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Public Health Faculty, Universitas Indonesia and Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) for supporting this research. The authors are also grateful to the respondents for their participation.

References

1. Wu Y, Chen C, Chan Y. The outbreak of COVID-19 : an overview. J Chin Med Assoc. (2020) 83:217–20. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000270

2. Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China. Glob Heal Res Policy. (2020) 5:1–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1097

3. Li Q, Quan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. (2020) 382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

4. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med Med. (2020) 382:727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

6. Ghinai I, McPherson T, Hunter J, Kirking H, Christiansen D, Joshi K, et al. Articles First known person-to-person transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the USA. Lancet. (2020) 395:1137–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30607-3

7. van der Sande M, Teunis P, Sabel R. Professional and home-made face masks reduce exposure to respiratory infections among the general population. PLoS ONE. (2008) 3:e2618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002618

8. WHO. Rational Use of Personal Protective Equipment for Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID-19. Geneva: WHO (2020).

9. Lewnard JA. Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:631–3. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30190-0

10. Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. (2020) 104:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022

11. Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, Packer J, Ward J, Stansfield C, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. (2020) 4:397–404. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30095-X

12. De Vos J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect. (2020) 5:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100121

13. Bach P, Robinson S, Sutherland C, Brar R. Comment innovative strategies to support physical distancing among individuals with active addiction. Lancet Psychiatry. (2020) 7:731–3. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30231-5

14. Ma SC, Wang HH, Chien TW. Hospital nurses' attitudes, negative perceptions, and negative acts regarding workplace bullying. Ann Gen Psychiatry. (2017) 16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12991-017-0156-0

15. Valls Martínez MDC, Ramírez-Orellana A. Patient satisfaction in the Spanish national health service: partial least squares structural equation modeling. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4886. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16244886

16. Owili PO, Hsu YHE, Chern JY, Chiu CHM, Wang B, Huang KC, et al. Perceptions and attitudes of health professionals in Kenya on national health care resource allocation mechanisms: a structural equation modeling. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0127160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127160

17. Ko DW, Stewart WP. A structural equation model of residents' attitudes for tourism development. Tour Manag. (2002) 23:521–30. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00006-7

18. Rasoolimanesh SM, Ali F, Jaafar M. Modeling residents' perceptions of tourism development: Linear versus non-linear models. J Destin Mark Manag. (2018) 10:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.05.007

19. Roopa S, Rani M. Questionnaire designing for a survey. J Indian Orthod Soc. (2012) 46(4 Suppl. 1):273–7. doi: 10.1177/0974909820120509S

20. Kang H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean J Anesthesiol. (2013) 64:402–6. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.5.402

21. Sabri A, Wan Mohamad Asyraf WA. The importance-performance matrix analysis in partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Int J Math Res. (2014) 3:1–14. Available online at: https://ideas.repec.org/a/pkp/ijomre/2014p1-14.html

22. Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Hair JF. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In: Homburg C, Klarmann M, Vomberg A, editors. Handbook of Market Research. Cham: Springer (2017). p. 1–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-05542-8_15-1

23. Levin KA. Study design III: cross-sectional studies. Evid Based Dent. (2006) 7:24–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375

24. Altmann DM, Douek DC, Boyton RJ. What policy makers need to know about COVID-19 protective immunity. Lancet. (2020) 395:1527–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30985-5

25. Rocklöv J, Sjödin H. High population densities catalyse the spread of COVID-19. J Travel Med. (2020) 27:1–2. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa038

26. Hamidi S, Sabouri S, Ewing R. Does density aggravate the COVID-19 pandemic?: early findings and lessons for planners. J Am Plan Assoc. (2020) 84:495–509. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2020.1777891

27. Kang D, Choi H, Kim JH, Choi J. Spatial epidemic dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 94:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.076

28. Pequeno P, Mendel B, Rosa C, Bosholn M, Souza JL, Baccaro F, et al. Air transportation, population density and temperature predict the spread of COVID-19 in Brazil. PeerJ. (2020) 8:1–15. doi: 10.7717/peerj.9322

29. Al-Hazmi A, Gosadi I, Somily A, Alsubaie S, Bin Saeed A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of secondary schools and university students toward middle east respiratory syndrome epidemic in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2018) 25:572–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2016.01.032

30. Sen-Crowe B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: staying home save lives. Am J Emerg Med. (2020) 38:1519–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.044

31. Sen S, Karaca-Mandic P, Georgiou A. Association of stay-at-home orders with COVID-19 hospitalizations in 4 states. JAMA. (2020) 323:2522–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9176

32. Bueno DC. Physical distancing: a rapid global analysis of public health strategies to minimize COVID-19 outbreaks. BMJ. (2020) 370:m2743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2743

33. Bueno DC. Physical distancing: a rapid global analysis of public health strategies to minimize COVID-19 outbreaks. IMRaD J. (2020) 3:3153. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30429.15840/1

34. Wu J, Gamber M, Sun W. Does wuhan need to be in lockdown during the Chinese lunar new year? Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:2019–21. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17031002

35. Zhang M, Zhou M, Tang F, Wang Y, Nie H, Zhang L, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 among healthcare workers in Henan, China. J Hosp Infect. (2020) 105:183–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.012

36. Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sern TJ, Ayub SH, Mohamad E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0233668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233668

37. Zhong BL, Luo W, Li HM, Zhang QQ, Liu XG, Li WT, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1745–52. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221

38. Al-Hanawi MK, Angawi K, Alshareef N, Qattan AMN, Helmy HZ, Abudawood Y, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 among the public in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Heal. (2020) 8:217. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00217

39. Khasawneh AI, Humeidan AA, Alsulaiman JW, Bloukh S, Ramadan M, Al-Shatanawi TN, et al. Medical students and COVID-19: knowledge, attitudes, and precautionary measures. A descriptive study from Jordan. Front Public Heal. (2020) 8:253. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00253

40. Zhang Y, Ma ZF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381

41. Greenhalgh T, Schmid MB, Czypionka T, Bassler D, Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. BMJ. (2020) 369:m1435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1435

42. Cheng KK, Lam TH, Leung CC. Wearing face masks in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic: altruism and solidarity. Lancet. (2020). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30918-1

43. Cheng VCC, Wong SC, Chuang VWM, So SYC, Chen JHK, Sridhar S, et al. The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. (2020) 81:107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.024

44. Eikenberry SE, Mancuso M, Iboi E, Phan T, Eikenberry K, Kuang Y, et al. To mask or not to mask: modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect Dis Model. (2020) 5:293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.04.001

45. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

46. De Zwart O, Veldhuijzen IK, Elam G, Aro AR, Abraham T, Bishop GD, et al. Perceived threat, risk perception, and efficacy beliefs related to SARS and other (emerging) infectious diseases: results of an international survey. Int J Behav Med. (2009) 16:30–40. doi: 10.1007/s12529-008-9008-2

47. Sadique MZ, Edmunds WJ, Smith RD, Meerding WJ, De Zwart O, Brug J, et al. Precautionary behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic influenza. Emerg Infect Dis. (2007) 13:1307–13. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070372

48. Sevi B, Eskenazi T. The impact of perceived threat of infectious disease on the framing effect. Evol Psychol Sci. (2018) 4:340–6. doi: 10.1007/s40806-018-0145-9

49. Ekici R, Cizel B. Examining the residents' attitudes toward tourism development: case study of Kaş, Turkey. In: Conference Proceedings Examining. GIBA (2014). p. 72734.

50. Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Mitchell R, Gudergan SP. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int J Hum Resour Manag. (2020) 31:1617–43. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1416655

51. Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev. (2014) 26:106–21. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

52. Kang JH, Jang YY, Kim JH, Han SH, Lee KR, Kim M, et al. South Korea's responses to stop the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Infect Control. (2020) 48:1080–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.003

53. Vinceti M, Filippini T, Rothman KJ, Ferrari F, Goffi A, Maffeis G, et al. Lockdown timing and efficacy in controlling COVID-19 using mobile phone tracking. EClinicalMedicine. (2020) 25:100457. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100457

54. Ghosal S, Bhattacharyya R, Majumder M. Impact of complete lockdown on total infection and death rates: a hierarchical cluster analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. (2020) 14:707–7011. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.026

55. Sahu D, Agrawal T, Rathod V, Bagaria V. Impact of COVID 19 lockdown on orthopaedic surgeons in India: a survey. J Clin Orthop Trauma. (2020) 11:283–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.05.007

56. Atalan A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-9 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Ann Med Surg. (2020) 56:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.010

Keywords: attitude, perception, COVID-19, Indonesia, modeling

Citation: Purnama SG and Susanna D (2020) Attitude to COVID-19 Prevention With Large-Scale Social Restrictions (PSBB) in Indonesia: Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Front. Public Health 8:570394. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.570394

Received: 07 June 2020; Accepted: 28 August 2020;

Published: 30 October 2020.

Edited by:

Hailay Abrha Gesesew, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

I. Gusti Ngurah Edi Putra, University of Wollongong, AustraliaYodi Mahendradhata, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2020 Purnama and Susanna. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sang Gede Purnama, c2FuZ3B1cm5hbWFAdW51ZC5hYy5pZA==

Sang Gede Purnama

Sang Gede Purnama Dewi Susanna

Dewi Susanna