- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medicine, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa

The phenomenon of street children is a challenging global social problem. Using an independent sample group design, this study explored the differences in self-esteem and resilience among street children and non-street children. A total of 300 (N = 300) street children with ages ranging from 8 to 18 years were selected using a purposive sampling method, while a total of 300 (N = 300) non-street children with ages ranging from 8 to 18 years were selected using a simple random sample to participate in this study. A questionnaire with three sections was used to collect data. Results of an independent sample t-test revealed that street children reported low self-esteem and poor resilience compared to non-street children. The study, therefore, concluded that street children and non-street children differ on self-esteem and resilience. It is recommended that social skills training be provided for the street children population.

Introduction

Street children phenomenon is a global social problem. In South Africa, The Tshwane Alliance for Street Children (1) reported about 100,000 cases of street children. They are defined as persons who are below the age of 18 years who live on the streets on their own without any form of parental or adult care (National Coalition for the Homeless as cited in Ligon (2)). They are identified as children who are in difficult or challenging circumstances some associated with chronic poverty in their homes (3). They are predisposed to psychosocial problems such as substance use (4) and exposure to violence and aggression (5), being victims of social ills such as rape, violence, and different acts of aggression (6). Their challenges also include sexual and reproductive health such as HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases (7). They are also prone to untimely deaths (8).

The challenges associated with street life exacerbate the behavioral issues of homelessness (9). They have to find ways of coping with the harsh living conditions on the street. Their survival methods include risky behavior (10) such as survival sex (9) and crime in the form of car/housebreaking (11) while occupying empty buildings as their primary shelter (12). Gang formation and taking part in illegal activities (13) allow for social acceptance in peer groups (14), which is another crucial survival strategy. Street children also engage in different forms of non-violent criminal behavior to survive the street strategy (15). As such, it is worth asking how these children cope on a daily basis.

To deal with the challenges mentioned previously, street children need some personal characteristics that are known to help people deal effectively with adverse situations, such as but not limited to self-esteem and resilience. Exploring self-esteem and resilience among this population with specific reference to differentiating street children from non-street children might shed light on the phenomenon, thus helping researchers, policymakers, and clinicians to formulate intervention strategies to help street children to cope with their adverse situations more adequately, hoping they will eventually leave the streets.

Rosenberg (16) defines self-esteem as a positive or negative attitude a person carries toward themselves. The self-esteem theory indicates that self-esteem serves as a form of a protective factor when an individual is faced with challenging situations (17). As much as self-esteem can be a good or positive feeling about the self, it is influenced by persons in one's life. Early childhood experiences significantly contribute to the development of one's self-esteem (18). Street children have reported poor self-esteem associated with poor subjective well-being (19). In a sample of homeless youth, high self-esteem was found to be related to low levels of psychological distress (20), reducing the risk of mental health problems (21), suggesting that self-esteem serves as a protective factor.

Resilience means the ability to bounce back suggesting that people with high resilience levels are likely to cope better under stressful life situations. Roy et al. (22) reported that resilient children are likely to cope better with adverse life situations as resilience is a protecting factor for them. Meaningfully, Karatas and Cakar (23) argued that when an individual's self-esteem improves, resilience also improves suggesting a link between resilience and self-esteem.

Various factors, including family environment, are associated with the development of resilience among children (24). In South Africa, street children come from unstable abusive family environments (25) which might negatively affect their development of resilience. However, Malindi and Theron (26) and Madu et al. (27) reported that street children are more resilient. Elsewhere, homeless youth have also been found to be resilient (28). They demonstrated this by engaging in peer mutual trust and friendships (29), taking part in street markets (30) finding shelter, and engaging in safer sex (31), thus enabling them to cope with street life.

Research has been conducted among street children populations across the globe, in Africa, and in Limpopo Province in particular (32–35). Most of the available studies focused on pathways from the homes to the streets and challenges during a period of homelessness with a few studies exploring the coping mechanisms. However, in South Africa, despite an increase in the visibility of children on South African streets, this population remains under-investigated. Those who have investigated this situation (34–36), have not explored their differences with children who are not in the streets.

Regardless of the evidence of hardship and trauma among this population (6), studies that explore coping strategies remain limited in South Africa. Few studies (6, 26, 36) explored resilience. More studies that explore resilience and other factors associated with coping strategies among this population are needed to help shed light on appropriate intervention strategies. It is anticipated that this study finding could inform tailor-made intervention strategies to address the challenges faced by this population. It is against this background that the current study explores the difference in self-esteem and resilience among street children, comparing them with children in the general population.

Materials and Methods

Participants

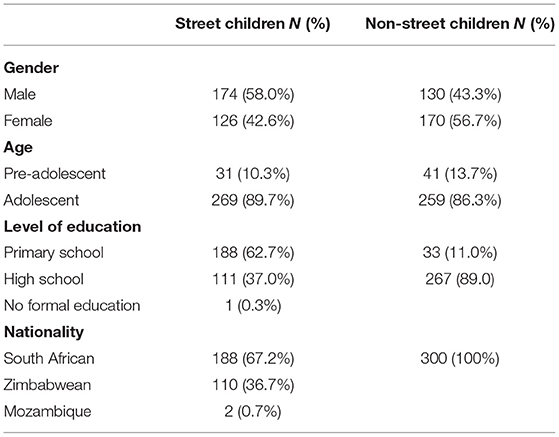

A total of 600 (N = 600) children, that is 300 street children who resided in the street of the towns of Limpopo Province and 300 children who stayed in their homes, were purposively sampled to take part in this study. The street children sampled comprised 42% males and 58% females with their ages ranging from 8–18 years with the mean age of 15.92 (SD = 1.89). The non-street children sample comprised 56.7 % females and 43.3% males with the age ranging from 8 to 18 years with a mean of 15.46 (SD = 1.87). The street children were compared to the family children.

From the street children population, the youngest to get to the street was at the age of 6 years. The majority (31.7%) of them have been in the streets for more than 2 years, followed by those who have been on the streets for more than 3 years (30.7%). Of the sample, 67.7 % did not have both parents as one (31.0%) or both (37.3%) died. These children are South African (62.7%), Zimbabwean (36.7%), and a few from Mozambique (0.7%) (Table 1). They have at least some high school (36.3%) and some primary school (35.7%) level of education. The reasons for their homelessness were linked to a history of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse while at home.

Procedure

The data were collected on the streets of various towns in Limpopo Province. This was with the use of a questionnaire that had three sections. Section A contained biographical information, Section B had a self-esteem scale, and Section C had the resilience scale. Participants completed the questionnaires voluntarily with the assistance of the first author and an appointed research assistant who is a registered mental health care professional. The principal investigator and the research assistant helped participants in completing the questionnaires. They read the questions out and clarified some of them, and participants filled in the answer that resonated with them. The participants completed the questionnaire starting from the demographic section to the different measures one after the other as the questionnaire was compiled. They were allowed to rest from completing the questionnaire for about 15–20 min when they needed to do so. They were allowed to continue with the questionnaire after the break.

The study received ethical approval (NWU-00117-10-A3- Mafikeng Health) from the Department of Psychology, Higher Degrees Committee, and Ethics Committee of the North-West University. Additional approval was obtained from the Limpopo Provincial Department of Education. Assent forms were also signed by the participants. For participants who were under the age of 18 years their legal guardians gave consent where applicable, and those participants on the streets only gave assent for participation.

Materials

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

This 10-item four-point Likert scale assessed the children's self-esteem (16). The items are scored differently with items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 scored from 0, which means strongly disagree, to three, which means strongly agree. Item 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10 are reverse scored with 0 indicating strongly agree and three indicating strongly disagree. The scores range from 0 to 30 with 30 being the possible highest score suggesting high self-esteem. The sample items include “on the whole, I am satisfied with myself” and “at times I think I'm no good at all.” This scale has been widely used across many populations of different demography. It is reliable 0.78 and 0.92 in South Africa (37) and also in the current study with an alpha of 0.65.

Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale

This 25-item scale was used to measure resilience (38). Each item is rated on five-point frequency response ranging from 0 (“not true at all”) to 4 (“true nearly all the time”). The total score is between 0 and 100 with a score of 51 and above suggesting greater resilience. Singh and Yu (39) found the overall alpha reliability of α = 0.89, whereas in the current study the Cronbach's' alpha reliability was 0.90.

Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 22). With this software, data were computed using an independent sample t-test to test the hypothesis about the difference in self-esteem and resilience between the two groups. Chi-square was also computed to determine gender and gender differences in self-esteem and resilience between the two groups.

Results

Self-Esteem and Resilience Differences

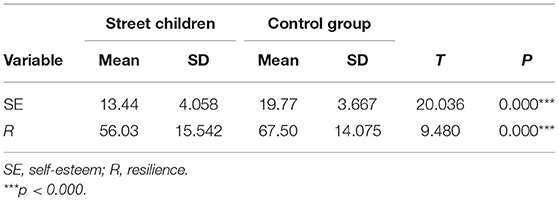

The results of the independent sample t-test revealed significant statistical differences in self-esteem [t(598) = 20.03, p < 0.000] between the two groups of street children and family children as indicated in Table 1. Further analysis of mean scores indicates that street children have poor self-esteem (mean = 13.44, SD = 4.06) compared to family children (mean = 19.77, SD = 3.67).

Furthermore, an independent sample t-test statistical analysis method was used to test the differences in resilience between these two groups. The results showed significant statistical differences in resilience [t(598) = 9.48, p < 0.000] between these two samples (see Table 2). Additionally, analysis of mean scores indicates that street children reported poor resilience (mean = 56.03, SD = 15.54) compared to family children who scored higher on resilience (mean = 67.50, SD = 14.06).

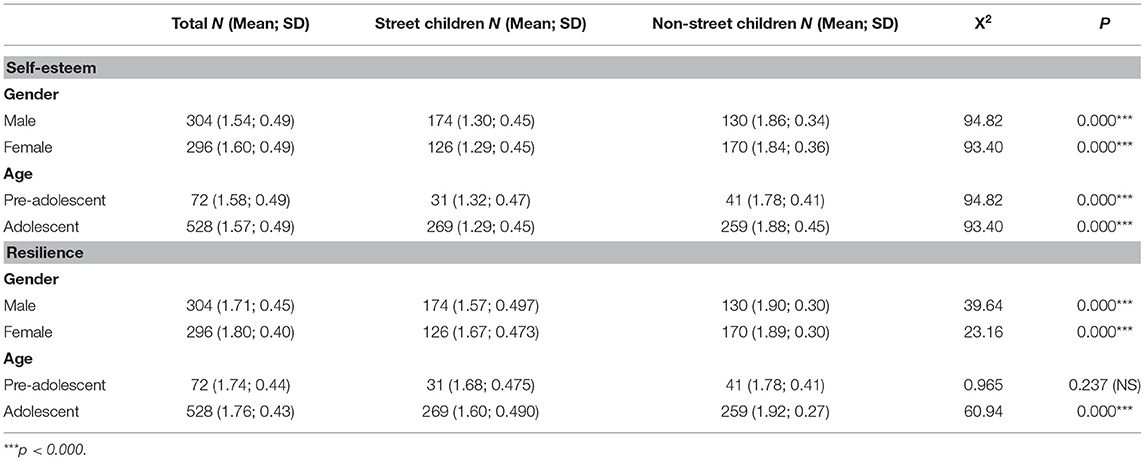

A chi-square analysis was computed to determine gender and age difference in self-esteem and resilience between the two groups (see Table 3 below). Male = 94.82, p = 0.000] and female = 93.40, p = 0.000] street children reported poor self-esteem compared to their non-street children counterparts. The same gender differences were further observed on resilience scores as male = 39.64, p = 0.000] and female = 23.16, p = 0.000] street children also reported poor resilience compared to the control.

Table 3. Results showing gender and age differences in self-esteem and resilience between the street children and non-street children.

Both pre-adolescent = 94.82, p = 0.000] and adolescent = 93.40, p = 0.000] street children reported poor self-esteem when compared to their non-street children age mates. The street children in the adolescent group = 60.94, p = 0.000] reported poor resilience where are there were no statistical difference in the pre-adolescent group when resilience was assessed.

Discussion

The main study aim was to explore self-esteem and resilience differences between street children and non-street children in the general population. An independent group sample design was chosen to explore group differences. The results revealed that street children reported low self-esteem compared to their non-street children counterparts suggesting challenges associated with self-esteem. These results are supported by Maccio and Schuler (40), who stated lower levels of self-esteem among the homeless youth compared to their non-homeless counterparts in the USA. Contrary to this finding Ezeokana et al. (41) in Nigeria reported no difference in self-esteem between street children and non-street children. Further contradictions were reported by Tozer et al. (42) as street youth had a good sense of self-worth demonstrated by their ability to refrain from substance abuse longing for a better future. The reasons these discrepancies in literature for the self-esteem and resilience could be attributed to the different types of street children that exists as Madu et al. (27) indicated that there are hard-core, sheltered, and part-time street children. Issues related to social stigma which are common among this population (43) also contribute. Those less stigmatized usually benefit from social support (44) by means of maintaining contact with their families. This suggests that future studies should explore different types of street children and their dynamics. Different street children reported different history of adversity (45) which could impact on their self-esteem and resilience.

Despite this discrepancy in literature, the current study finding suggests that the street children population remains at risk due to their low self-esteem suggesting the reason for prolonged periods of homelessness. To curb this challenge, street children need to be helped with self-esteem as it serves as a protective factor for those who experienced adversities (44, 46).

The self-esteem theory which indicates that self-esteem is a result of positive appraisal by significant others (47) can help with a better understanding of the current results. In this case, due to common reasons for homelessness, such as poverty, neglect, family breakdown, death of one or both parents, and other forms of child abuse (8, 48, 49), these children lack that positive appraisal. This could also be attributed to the fact that a majority of the samples had no parents who usually serve as a foundation of self-esteem. This is seen in other studies, where street children have been reported to have been abused by their parents who were supposed to protect them and enhance their self-esteem (50, 51). Furthermore, in most instances, street children have no family ties and spend most of the time of their lives worrying about their survival and not about their worth.

This study revealed that street children reported poor resilience compared to non-street children. These results concur with the work of Cleverley and Kidd (52) who found lower resilience among homeless youth. Regardless of these findings, there is still evidence of large numbers of street children in many South African cities (26). This could be associated with their resilience which was reported by Malindi (36). This indicates that, as much as street children in this current study reported poor resilience compared to their non-street children counterparts, this does not mean that they are not resilient. They are found not to be resilient only when a comparison with their non-street children counterpart is made. This is supported by other studies that have revealed that, even when some street children reported psychological problems such as post traumatic stress disorder, they were still found to be resilient (53). Despite evidence of harsh living conditions, street children have shown adaptability as the majority of them have lived on the streets for years in the current study, up to 7 years.

Evidence that somehow street children can cope with their living conditions may help answer this question. They use personal character and emotional strength, cultural values, religious beliefs, and peer support (6). This is also in line with their responses on the resilience scale as some answered positively to questions about seeking help from friends and praying about their situation. They support each other during difficult times, and that helps them survive harsh street life (54). Furthermore, due to the available peer support these children offer to each other and other forms of support received from people who provide them with money and food (55, 56) or other family and community capacities (57), they can be regarded as resilient as such relationships promoter resilience (58).

It is worthy to note that the street children in this sample continued to report low scores on self-esteem and resilience when compared to their non-street children counterparts in terms of gender and age. Male and female adolescent street children reported poor self-esteem and resilience when compared to non-street children. The pre-adolescent street children reported poor self-esteem when compared to non-street children, but no significant statistical difference was found between pre-adolescent street children and non-street children with resilience. These results stress the different levels of self-esteem and resilience between these two groups. A possible explanation for these findings could be the continued adversity faced by this group while still at home (59) and while on the streets (60). This suggests that treatment intervention plans should be inclusive of all street children regardless of age and gender.

Limitations

The cross-sectional design and nature of this study serve as a limitation. Data were collected once-off at a single point in time minimizing the possibilities of establishing causalities. The children solely reported on the data self-report, and data from parents or guardians could not be collected. There also might have been a poor recall of childhood memories leading to inaccurate reporting. Other extraneous variables such as temperament and coping styles were not explored.

Several strengths have been noted in this study. Data were collected from those children who were on the streets surviving mainly on their own rather than from those children who are in care centers who receive help in different forms. It is argued that their survival and coping strategies are thus not influenced by the help they receive in care centers. South Africa has an estimate of 250,000 street children (61) with an increase of 0.002 to 0.22 in Limpopo Province (62). This makes the sample size of the study big enough to generalize the findings for the Limpopo Province which could be extended to other provinces.

Conclusions

This study concludes that there is a significant difference between street children and non-street children. Street children differed from non-street children in terms of self-esteem and resilience where street children reported low self-esteem and poor resilience. However, this does not take away from the fact that street children demonstrated to some extent a level of self-esteem and resilience even though it was not statistically significant.

Suggestions for Improvements

Future studies should consider exploring other extraneous variables such as socio-demographic factors that could influence the street children's survival method. History of substance use or use should also be considered. Longitudinal studies can provide a clearer pattern on self-esteem and resilience of this population helping in the formation of intervention strategies over time.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by North-West University Ethics Committee. Written informed consent from the participants' legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

MM has developed the study concept, study design, sought ethical clearance, data collection, capturing and analysis were performed, wrote this manuscript, contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

North-West University post-graduate bursary partially funded this project. Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University has funded the publication of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

2. Ligon L. Infectious diseases among homeless children and adolescents: a national concern. Semin Paediatr Infect Dis. (2000) 11:220–6. doi: 10.1053/pi.2000.9079

3. Lugalla JLP, Mbwambo JK. Street children and street life in urban Tanzania: the culture of surviving and its implications for children's health. Int J Urban Reg Res. (1999) 23:329–44. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00198

4. Sharma N, Joshi S. Preventing substance abuse among street children in India: a literature review. Health Sci J. (2013) 7:137–48.

5. Anooshian LJ. Violence and aggression in the lives of homeless children: a review. Aggress Violent Behav. (2005) 10:129–52. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.10.004

6. Hills F, Meyer-Weitz A, Asante KO. The lived experiences of street children in Durban, South Africa: violence, substance use and resilience. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. (2016) 11. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.30302

7. Kruger LM, Richter JM. South African street children - at risk for AIDS? Afr Insight. (1996) 26:237–43.

8. Hickler B, Auerswald CL. The worlds of homeless white and African American youth in San Francisco, California: a cultural epidemiological comparison. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 68:824–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.030

9. Gwadz MV, Gostnell K, Smolenski C, Willis B, Nish D, Nolan TC, et al. The initiation of homeless youth into the street economy. J Adolesc. (2009) 32:357–77. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.01.004

10. Rachlis BS, Wood E, Zhang R, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. High rates of homelessness among a cohort of street-involved youth. Health Place. (2009) 15:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.008

11. Idemudia ES. Personality and criminal outcomes of homeless youth in a Nigerian jail population: results of PDS and MAACL-H assessments. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2007) 19:137–45. doi: 10.2989/17280580709486649

12. Milburn NG, Swendeman D, Amani B, Applegate E, Winetrobe H, Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. Homelessness. Encycl Adolesc. (2011) 2:135–41. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-373951-3.00062-4

13. Akers R. Social Learning and Social Structure: A General Theory of Crime and Deviance. Boston: North-eastern University Press (1998).

14. Bender R. Why do some maltreated youth become juvenile offenders? A call for further investigation and adaptation of youth services. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2010) 32:466–73. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.10.022

15. Fischer SN, Shinn M, Shrout P, Tsemberis S. Homelessness, mental illness, and criminal activity: examining patterns over time. Am J Commun Psychol. (2008) 42:251–65. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9210-z

16. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (1965). doi: 10.1515/9781400876136

17. Rosenberg M, Schooler C, Schoenbach C, Rosenberg F. Global self-esteem and specific self-esteem: different concepts, different outcomes. Am Sociol Rev. (1995) 60:141–56. doi: 10.2307/2096350

18. DeHart T, Pelham BW, Tennen H. What lies beneath: parenting style and implicit self-esteem? J Exp Soc Psychol. (2006) 42:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.12.005

19. Cheng F, Lam D. How is street life? An examination of the subjective wellbeing of street children in China. Int Soc Work. (2010) 53:353–65. doi: 10.1177/0020872809359863

20. Dang MT. Social connectedness and self-esteem: predictors of resilience and mental health among maltreated homeless youth. Issues Ment Health Nurs. (2014) 35:212–9. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2013.860647

21. Ni C, Liu X, Hua Q, Lv A, Wang B, Yan Y. Relationship between coping, self-esteem, individual factors and mental health among Chinese nursing students: a matched case-control study. Nurse Educ Today. (2010) 30:338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.09.003

22. Roy A, Carli V, Sarchiapone M. Resilience mitigates the suicide risk associated with childhood trauma. J Affect Disord. (2011) 133:591–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.006

23. Karatas Z, Cakar FS. Self-esteem and hopelessness, and resilience: an exploratory study of adolescence in Turkey. Int Educ Stud. (2011) 4:84–91. doi: 10.5539/ies.v4n4p84

24. Mandleco BL, Peery JC. An organizational framework for conceptualising resilience in children. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. (2000) 13:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2000.tb00086.x

25. Idemudia ES, Kgokong K, Kolobe P. Street children in Mafikeng, North-West Province: a qualitative study of social experiences. J Soc Dev Afr. (2013) 28:161–85.

26. Malindi MJ, Theron LC. The hidden resilience of street children. S Afr J Psychol. (2010) 40:318–26. doi: 10.1177/008124631004000310

27. Madu SN, Meyer A, Mako MK. Tenacity, purpose in life and quality of interpersonal relationships among street children in the Vaal Triangle Townships of South Africa. J Soc Sci. (2005) 11:197–206. doi: 10.1080/09718923.2005.11892514

28. Obradović J. Effortful control and adaptive functioning of homeless children: variable-focused and person-focused analyses. J Appl Dev Psychol. (2010) 31:109–17. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2009.09.004

29. Kaime-Atterhög W, Ahlberg BM. Are street children beyond rehabilitation? Understanding life situation of street boys through ethnographic methods in Nakuru, Kenya. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2008) 30:1345–54. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.003

30. Libório RMC, Ungar M. Children's perspectives on their economic activity as a pathway to resilience. Child Soc. (2010) 24:326–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00284.x

31. Lankenau SE, Clatts MC, Welle D, Goldsamt LA, Gwadz MV. Street careers: homelessness, drug use, and sex work among young men who have sex with men (YMSM). Int J Drug Policy. (2005) 16:10–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2004.07.006

32. Baron SW. Street youths' control imbalance and soft and hard drug use. J Crim Justice. (2010) 38:903–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.06.006

33. Hoersting RC, Jenkins SR. No place to call home: cultural homelessness, self-esteem and cross-cultural identities. Int J Intercult Relat. (2011) 35:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.005

34. Mthombeni HM. Factors in the Family System Causing Children to Live in the Streets: A Comparative Study of Parents' and Children's Perspectives. Unpublished master's dissertation. University of Pretoria, South Africa (2010). Available online at: http://upetd.up.ac.za/thesis/available/etd-09292010-175540/unrestricted/disseration.pdf (accessed October 11, 2019).

35. Shiluvane RD, Khoza LB, Lebese RT, Shiluvane HN. An intervention programme to improve the quality of life of street children in Mopani district, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recreation Dance. (2012) 3:174–84. doi: 10.10520/EJC128322

36. Malindi MJ. Swimming upstream in the midst of adversity: exploring resilience-enablers among street children. J Soc Sci. (2014) 39:265–74. doi: 10.1080/09718923.2014.11893289

37. Westaway MS, Wolmarans L. Depression and self-esteem: rapid screening for depression in black, low literacy, hospitalised tuberculosis patients. Soc Sci Med. (1992) 35:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90184-R

38. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. Depress Anxiety. (2003) 18:76–82 doi: 10.1002/da.10113

39. Singh K, Yu X. Psychometric evaluation of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) in a sample of Indian students. J Psychol. (2010) 1:23–30. doi: 10.1080/09764224.2010.11885442

40. Maccio EM, Schuler JT. Substance use, self-esteem and self-efficacy among homeless and runaway youth in New Orleans. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. (2012) 29:123–36. doi: 10.1007/s10560-011-0249-6

41. Ezeokana JO, Obi-Nwuso H, Okoye CAF. Influence of street life and gender on aggression and self-esteem in a sample of Nigerian children. Int Rev Manage Bus Res. (2014) 3:949–59.

42. Tozer K, Tzemis D, Amlani A, Coser L, Taylor D, Van Borek N, et al. Reorienting risk to resilience: street-involved youth perspectives on preventing the transition to injection drug use. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:800. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2153-z

43. Kidd SA. Youth homelessness and social stigma. J Youth Adolesc. (2007) 36:291–9. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9100-3

44. Kidd S, Shahar G. Resilience in homeless youth: the key role of self-esteem. Am J Orthopsychiatry. (2008) 78:163–72. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.2.163

45. Mathur M, Rathore P, Mathur M. Incidence, type and intensity of abuse in street children in India. Child Adolesc Abuse. (2009) 33:907–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.01.003

46. Lightfoot M, Stein JA, Tevendale H, Preston K. Protective factors associated with fewer multiple problem behaviours among homeless/runaway youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. (2011) 40:878–89. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.614581

48. Gwadz MV, Clatts MC, Leonard NR, Goldsamt L. Attachment style, childhood adversity, and behavioural risk among young men who have sex with men. J Adolesc Health. (2004) 34:402–14. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00329-X

49. Whitbeck LB, Crawford DM, Hartshorn KJS. Correlates of homeless episodes among indigenous people. Am J Commun Psychol. (2012) 49:156–67. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9446-x

50. Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Risk factors for homelessness among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: a developmental milestone approach. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2012) 34:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.09.016

51. Conticini A, Hulme D. Escaping violence, seeking freedom: why children in Bangladesh migrate to the street. Develop Change. (2007) 38:201–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00409.x

52. Cleverley K, Kidd SA. Resilience and suicidality among homeless youth. J Adolesc. (2011) 34:1049–54. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.003

53. Cénat JM, Derivois D, Hébert M, Amédée LM, Karray A. Multiple traumas and resilience among street children in Haiti: Psychopathology of survival. Child Abuse Negl. (2018) 79:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.024

54. Reza MH, Henly JR. Health crises, social support, and care giving practices among street children in Bangladesh. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2018) 88:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.006

55. Bender K, Thompson SJ, McManus H, Lantry J, Flynn PM. Capacity for survival: exploring strengths of homeless youth. Child Youth Care Forum. (2007) 36:25–42. doi: 10.1007/s10566-006-9029-4

56. Harden TD. Street life-oriented African American males and violence as a public concern. J Human Behav Soc Environ. (2014) 24:678–93. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2014.930300

57. Ungar M. Pathways to resilience among children in child welfare, corrections, mental health and educational settings: navigation and negotiation. Child and Youth Care Forum. (2005) 34:423–44. doi: 10.1007/s10566-005-7755-7

58. Ungar M, Liebenberg L, Boothroyd R, Kwong MW, Lee TK, Leblanc J, et al. The study of youth resilience across cultures: Lessons from a pilot study of measurement. Develop Res Hum Develop. (2008) 5:166–80. doi: 10.1080/15427600802274019

59. McAlpine K, Henley R, Mueller M, Vetter S. A survey of street children in Northern Tanzania: how abuse or support factors may influence migration to the streets. Commun Ment Health J. (2010) 46:26–32. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9196-5

60. Melander LA, Tyler KA. The effect of early maltreatment, victimization, and partner violence on HIV risk behaviour among homeless young adults. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 47:575–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.010

61. Consortium for Street Children. Consortium of Street children, Annual Report of 2009. Available online at: https://www.globalgiving.org (accessed October 11, 2019).

Keywords: South Africa, Limpopo Province, street children, non-street children, self-esteem, resilience

Citation: Maepa MP (2021) Self-Esteem and Resilience Differences Among Street Children Compared to Non-street Children in Limpopo Province of South Africa: A Baseline Study. Front. Public Health 9:542778. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.542778

Received: 02 September 2020; Accepted: 12 February 2021;

Published: 23 April 2021.

Edited by:

Marie Leiner, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Sharon Zlotnik, University of Haifa, IsraelLuis Alvaro Moreno Espinoza, The College of Chihuahua, Mexico

Copyright © 2021 Maepa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mokoena Patronella Maepa, bW9rb2VuYW1hZXBhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Mokoena Patronella Maepa

Mokoena Patronella Maepa