- 1Division of Epidemiology and Public Health, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 2The Nottingham Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare: A Joanna Briggs Institute Centre of Excellence, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 3School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

- 4National Institute for Health Research Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Regular physical activity has a range of benefits for children's health, academic achievement, and behavioral development, yet they face barriers to participation. The aim of the study was to systematically develop an intervention for improving Chinese children's physical activity participation, using the Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). The BCW and TDF were used to (i) understand the behavior (through literature review), (ii) identify intervention options (through the TDF-intervention function mapping table), (iii) select content and implementation options [through behavior change technique (BCT) taxonomy and literature review], and (iv) finalize the intervention content (through expert consultation, patient and public involvement and engagement, and piloting). A systematic iterative process was followed to design the intervention by following the steps recommended by the BCW. This systematic process identified 10 relevant TDF domains to encourage engagement in physical activity among Chinese children: knowledge, memory, attention and decision processes, social influences, environmental context and resources, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, social/professional role and identity, emotions, and physical skills. It resulted in the selection of seven intervention functions (education, persuasion, environmental restricting, modeling, enablement, training, and incentivization) and 21 BCTs in the program, delivered over a period of 16 weeks. The BCW and TDF allowed an in-depth consideration of the physical activity behavior among Chinese children and provided a systematic framework for developing the intervention. A feasibility study is now being undertaken to determine its acceptability and utility.

Background

Health benefits of physical activity among children are vast (1, 2). Regular participation in physical activity can improve children's overall health (e.g., cardiovascular health, mental health, musculoskeletal health) and can contribute to their social well-being (3). Evidence shows low physical activity levels among children, and physical inactivity continues to be a major public health problem globally (4). The World Health Organization's (WHO) physical activity guideline recommends a minimum of 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day among children aged 5–17 years, including vigorous activities and activities that strengthen muscles and bones at least 3 days per week (1). WHO also recommends that these children should limit the amount of time spent on being sedentary and recreational screen time in particular (1). In China, however, only 34% of school-aged children have met the recommended 60 min of MVPA per day, and only 9% of children have spent at least 3 days on vigorous activities per week (5, 6). Around 35% of children have failed to adhere to the recommendations on sedentary and recreational screen time (5, 6). Boys are more likely to meet the MVPA recommendations compared to girls. However, boys are less likely to meet the sedentary and recreational screen recommendations compared to girls (7). A range of factors may influence a child's physical activity, including (i) personal (relating to physical, emotional, or mood-associated factors among children), (ii) socio-cultural (relating to people with whom the child would come in contact with, such as parents/guardians and teachers), (iii) environmental (relating to structural elements such as facilities and transport), and (iv) policy- and program-related (relating to programs, organizations, and staff) factors (8–14). MVPA starts to decline among children at around 13 years of age irrespective of their residence (i.e., urban or rural) (5, 15, 16). These factors are interconnected and important at different stages across the lifespan, with certain aspects being more influential at different points across the life course. Approximately 25% of Chinese children have spent over 30 min on MVPA in primary school (aged 7–12 years) whilst only 15% and 10% of junior middle children (aged 13–15 years) and junior high children (aged 16–18 years), respectively (10). This is consistent with several national and international surveys that have reported children's physical activity starts to decline at 10–12 years of age (17, 18). In other words, it can be beneficial to target health behaviors (including physical activity) at this transition period as children approach adolescence.

In China, children are under huge academic pressure as a result of the national exam-oriented education system. Over one-third of these children report psychosomatic symptoms at least once a week, and around 76% of them report being in a bad mood because of academic pressure and high parental expectation (19). This pressure increases from junior middle school to junior high school (20). On weekdays, the school hours last for ~9 h for Chinese children in primary school, which is more intensive than in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK) (21–23). In schools, health (physical) education and structured exercise programs are available and delivered to the children orally and/or in written format. Structured exercise sessions are run to achieve the recommended intensity and duration of physical activity. However, evidence suggests that these programs either do not intervene on the children's intrinsic determinations to physical activity or physical activity that occurs after school (e.g., weekends and holidays) (24). At the administrative level, a “shrinkage” of physical activity time for children has been identified due to the low enforcement of physical activity policy and unorganized school support (24, 25). Moreover, there has been a consistent decline in physical activity time among Chinese children over the past two decades (26). Health education sessions are often replaced by other elements of the academic curriculum due to bad weather or during periods when children are due to undergo academic assessments (24). Health education has not historically been valued within the curriculum because it is not a mandatory module listed on the national university entrance exam (24, 27). In addition, the number of health education sessions set up for children reduces as they move into higher classes (27). In turn, the organization of health education becomes relatively insignificant in Chinese schools, which fails to provide a supportive physical activity environment and appropriate physical activity education or values for the children, parents, and teachers. Moreover, the development process of these programs remains questionable, and most of these programs are not based on behavior change theories (28–30). For instance, a systematic review of the effectiveness of physical activity programs has suggested that the programs in China delimit the rigorous process of development and evaluation (30–32). Around 80% of these physical activity programs are found to be of poor quality. Furthermore, the program designs lack a theoretical basis for the analysis regarding potential drivers of target behaviors (30–32). The quality of interventions could be improved through consulting experts and by having patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) during intervention development, dissemination, and implementation; however, previous studies have often neglected or not reported these steps in the intervention development (33). This could be due to the associated costs of PPIE, short timescales for delivery of interventions, not understanding the importance of PPIE steps, or having a tight word limit in peer-reviewed publications.

Theory-based interventions are more likely to succeed and could help to elucidate why and how the intervention components may contribute to the overall effectiveness (34). In contrast, non-theory based interventions are less likely to be successful as they may fail to translate the existing scientific evidence into knowledge and practice and neglect the potential explanatory underpinnings of the target behaviors or problems (35, 36). As such, there is a need to develop theory-based interventions. The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW) and Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) are models that could provide a systematic and comprehensive assessment of the factors that are likely to influence behaviors (37, 38). Specifically, the BCW is a synthesis of 19 frameworks of behavior change and is based on a Capability Opportunity Motivation Behavior (COM-B) model, which is fundamental to the identification of changes needed for desired behavior and selection of associated intervention functions and behavior change techniques (BCTs) (34, 37). Theoretically, the COM-B model assumes that interactions between an individual's capability, opportunity, and motivation can explain why a particular behavior is or is not performed (34). Each COM-B component can be further subdivided into two categories. Capacity can be physical (e.g., physical skills, strength) or psychological (e.g., knowledge, psychological skills) capacity to engage in the activity concerned. Opportunity can be physical (e.g., time, resource) or social (e.g., cultural norms, interpersonal influences) factors that lie outside the individual that prompt the behavior. Motivation can be reflective (e.g., self-conscious intentions, plans) or automatic (e.g., emotional reactions, desires) brain processes that energize and direct the behavior. Altogether, the COM-B model provides a systematic and comprehensive way to guide the behavior change analysis to bring about the desired behavioral change. The TDF is an elaboration of the COM-B that consists of 14 theoretical domains and can be used for a detailed analysis of potential barriers and facilitators to be targeted in an intervention (38). In total, a set of 14 domains covering the main factors influencing a practitioner's clinical behavior and behavioral changes were identified, including (i) knowledge, (ii) skills, (iii) social/professional role and identity, (iv) beliefs about capabilities, (v) optimism, (vi) beliefs about consequences, (vii) reinforcement, (viii) intentions, (ix) motivation and goals, (x) memory, attention, and decision processes, (xi) environmental context and resources, (xii) social influences, (xiii) emotion, and (xiv) behavioral regulation (38). Overall, these 14 domains provide an extensive framework to prompt the consideration of good coverage of influencers to behavioral change and therefore improves the intervention implementation. The BCW has been successfully used to inform the design of many interventions that target a variety of health-related issues, such as stroke rehabilitation, auditory rehabilitation, and cancer symptom awareness (39–41). Moreover, it has been successfully used to develop physical activity interventions in both children and adults in high-income countries (42, 43). However, there remains a dearth of research using the BCW and TDF to develop a physical activity intervention in an upper middle-income country like China (44, 45). Physical activity interventions are likely to be complex interventions as several components interact with those who deliver and those who receive the intervention. It is also needed to take account of the role of parents and the environment for physical activity. Developing an intervention that is aimed at increasing children's physical activity level has much to do with behavioral change (46). This is because intervening through the promotion of physical activity is a long-term behavior change process that should include both behavior initiation and maintenance. However, previous studies have paid little attention to behavioral changes of children and people who have responsibility for them (i.e., parents, guardians, or teachers) in the development and implementation of complex interventions (30–32). Similarly, previous studies have understated the role of policy- and program-related factors (i.e., sports programs, organizations, and government departments) in the development process. Interventions aimed at changing Chinese children's behavior have generally proven problematic in demonstrating efficacy, possibly because of a lack of or inadequate theoretical foundation in the development phase (30). Furthermore, interventions have been criticized for lacking a theoretical rationale and detailed reporting, thus complicating both the development and the possibility of replicating or improving interventions (34).

The application of the BCW varies from one context or behavior to another. For instance, the barriers and facilitators to children's physical activity differ in different cultural contexts. As such, a theory-based physical activity intervention is needed in China. Thus, the aim of the study was to use BCW and TDF for designing the components of an intervention to improve Chinese children's (aged 10–12 years) physical activity. Specifically, this is the first stage of the UK Medical Research Council's (MRC) widely used framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions, which describes four phases: intervention development, feasibility/piloting, evaluation, and implementation (46). The specific objectives were to (i) identify barriers and facilitators to physical activity in ethnic Chinese children and determine which barriers and facilitators need to be addressed in different settings (e.g., home, school, community), (ii) identify the type of intervention functions required to bring about the change, (iii) identify specific BCTs aligned to the purpose of physical activity promotion, and (iv) develop the intervention content and structure for the physical activity program.

Methods

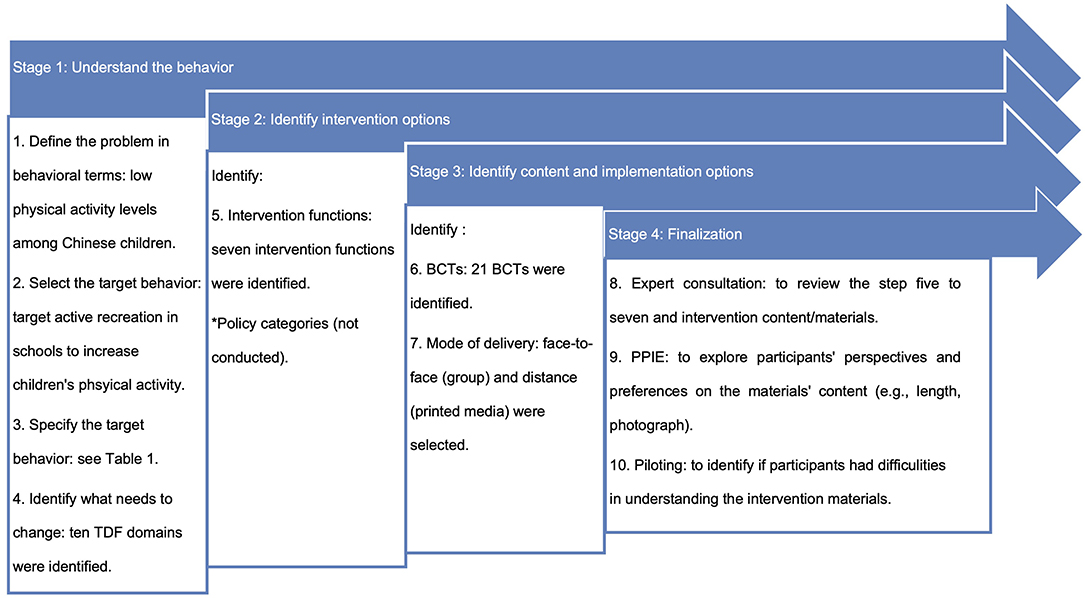

BCW and TDF intervention development steps were followed, and this was an iterative process (e.g., going back to the previous step and making changes based on the feedback) (37). In the BCW, the intervention design has eight steps: (i) defining the problem in behavioral terms, (ii) selecting the target behavior, (iii) specifying the target behavior, (iv) identifying what needs to change, (v) identifying intervention functions, (vi) identifying policy categories, (vii) identifying BCTs, and (viii) identifying the mode of delivery (37). We broadly followed these steps (except for identifying policy categories) along with the process of expert consultation, PPIE, and piloting in developing the physical activity intervention (see Figure 1). Reporting of the developed intervention is in accordance with The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) (see Table 1) (47).

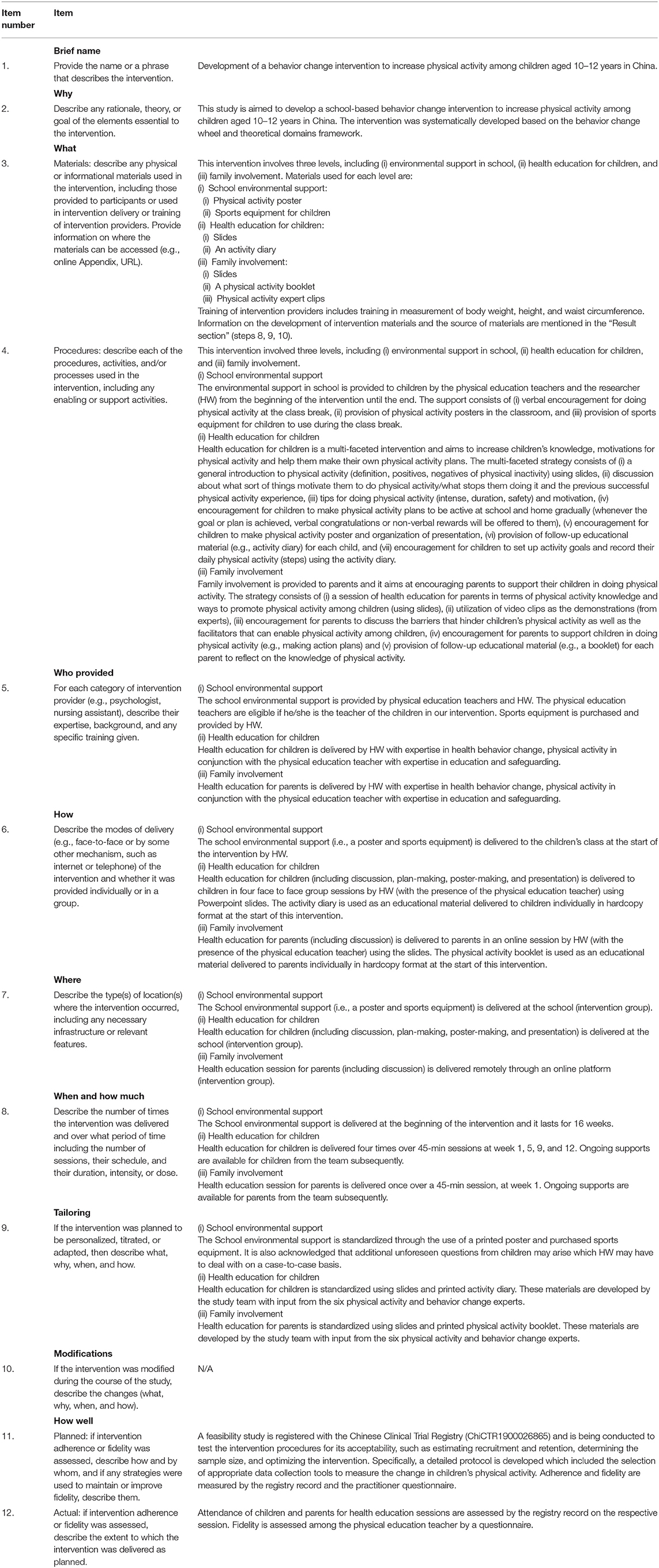

Table 1. Description of the finalized intervention and implementation strategy using the TIDieR checklist.

Step 1: Define the Problem in Behavioral Terms

In this step, researchers are to define the problem in behavioral terms, and there are two components: (i) who would perform the behavior and (ii) what the behavior would be (37). We took into account the specific behavioral context of the problem (i.e., low physical activity levels among Chinese children), and conducted an exploratory literature review to identify the national statistics on physical inactivity and its negative health consequences among Chinese children, and major barriers and facilitators to improving their physical activity (4–7, 48, 49). Specifically, to support our study rationale, an initial search was carried out on MEDLINE and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases using the keywords: “physical activity,” “physical education,” “Chinese,” “children,” “barriers,” and “facilitators.”

Step 2: Select the Target Behavior

Having defined the problem of the low level of physical activity in step one, the next step was to decide which behavior to target through the research literature. In this step, a literature search on the trends of physical activity among Chinese children in different physical activity domains (i.e., everyday activity, active recreation, and sport) was undertaken to identify the target behavior that could address the defined problem (as identified in step one) (50–59). Four criteria from the BCW model were used to inform the selection of the final target behavior: (i) how much of an impact changing the behavior would have on the desired outcome, (ii) how likely it is that the behavior can be changed, (iii) how likely it is that the behavior would have a positive or negative impact on other related behaviors, and (iv) how easy it would be to measure the behavior (37).

Step 3: Specify the Target Behavior

Behavior specification is the step following the selection of the target behavior where the researchers need to specify the behavior in precise and appropriate detail and in its context. As guided by the BCW, six questions were raised in this step to help us specify the target behavior (37). These questions include (i) who would perform the target behavior, (ii) what they would need to do differently to achieve change, (iii) where and (iv) when they needed to do it, (v) how often, and (vi) with whom would they do it. Similar to step one and two, a literature search along with researchers' knowledge of children's physical activity helped us to develop the behavior specification (14, 56, 60–62).

Step 4: Identify What Needs to Change

We previously conducted a Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) qualitative systematic review to synthesize the barriers and facilitators to physical activity (as understood, perceived, or experienced) among ethnic Chinese children who reside in the Chinese and non-Chinese territory or among people who had responsibility for them (e.g., ethnic Chinese/non-Chinese parents, teachers) (63, 64). As this intervention is aimed at Chinese children who are residing in China, only barriers and facilitators to physical activity among Chinese children who reside in the Chinese territories were included. Using the TDF domains and definitions as a guide, the identified barriers and facilitators were coded into 14 TDF domains based on similarity in statements and were illustrated with the quotations. The statements and quotations identified from the systematic review were examined to determine (i) any conflicting beliefs within the domain and (ii) the frequency of specific beliefs across the data (i.e., the percent (count) of statements coded for each specific TDF domain out of the total identified statements).

Step 5: Identify Intervention Functions

Using the mapping table (TDF-intervention function) in the BCW, the intervention functions that most likely affect the behavioral change were selected based on the TDF diagnosis (37). All the intervention functions were then assessed according to their affordability, practicability, effectiveness/cost-effectiveness, acceptability, side-effects/safety, and equity (APEASE) (37).

Identify Policy Categories (Not Conducted)

As this study aimed to theoretically develop a school-based intervention and was not related to changing policy on physical activity, this step was skipped. However, the evidence accumulated from the development process may provide useful insights related to policy categories (e.g., guidelines, regulations) for achieving behavioral changes.

Step 6: Identify Behavior Change Techniques and Intervention Contents

BCTs are considered as the “active ingredients” of an intervention to change behaviors (37). Specifically, BCTs are observable, replicable, and an irreducible component of the behavioral change intervention and a postulated active ingredient within the intervention (i.e., the proposed mechanisms of change). Previously, BCTs have been identified in relation to particular types of behaviors (e.g., physical activity), and these behavior-specific “taxonomies” of BCTs have been synthesized. The BCW is linked with a taxonomy of BCTs that allows systematic and transparent selection of the specific BCTs that would best serve the intervention functions (37, 65). As such, this step used BCT taxonomy (BCTTv1) to identify and map the most frequently used BCTs for each intervention function (65). To identify any additional BCTs, a comprehensive matrix developed by Michie and colleagues to map the relevant 59 BCTs from the BCTTv1 to the TDF domains was utilized (37). The intervention content was then identified in the form of BCTs that would help bring about the target behavior. The APEASE criteria were again used to narrow down the most frequently used BCTs for each intervention function (37).

Step 7: Identify the Mode of Delivery

In the final step of the BCW, it prompts researchers to consider the full range of possible modes of delivering the interventions before deciding the most appropriate one for the particular target behavior and population and setting (37). We identified the modes of delivery for BCTs after taking into consideration the context in which the intervention would be implemented. Specifically, the selection was based on the previous experience of physical activity intervention development in the research team and supplemented by the findings obtained from similar research of physical activity intervention among children (44, 61, 66–71). Once again, the APEASE criteria were used to assess the selection of the modes of delivery (37).

Step 8: Expert Consultation

A consultation on the intervention was conducted with six academic researchers from the UK (n = 4) and China (n = 2). Specifically, they have specialized knowledge and professional experience in developing physical activity interventions and/or behavioral change interventions. They were purposively selected to ensure representation of diversity by expertise. Two of the study researchers (HB/KC) have expertise in the field of physical activity and behavior change, and so access to these physical activity and behavior change experts was gained through professional networks within the study team. The intervention materials were shared with them through email, and they reviewed the selection of intervention functions, BCTs, and content as well as the readability, flow of information, and consistency of expressions in the developed intervention. All experts reviewed the intervention materials independently, and their feedback (received via email) was used to improve the intervention structure and materials. Specifically, we thoroughly reviewed and discussed each comment given by the experts and then revised the intervention materials accordingly.

Step 9: Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement in Research

PPIE in research means doing research “with” the patients and public in research (72). In other words, they should be actively involved in research activities as partners and decision-making. In turn, it could make the methods and outcomes more appropriate to research participants (73). In this case, PPIE involvement provided their perspectives, and the aim was not to ensure their “representativeness” (74). We aimed for a variety of perspectives and different viewpoints. Six lay people in China were part of this PPIE. They were the intended user community and purposively selected. Like step eight, we used our lay members' contact to approach these lay people. Specifically, PPIE group included one boy and a girl aged 10–12 years, parents of each child (one father and one mother who had university education and were employed), and two physical education teachers (one male, one female) who had more than 20 years of teaching experience in a local public primary school in China. The intervention materials were shared with them (i.e., children viewed materials for children, parents viewed materials for children and parents, teachers reviewed all materials), and their preferences were identified (i.e., decision was made by considering whom the material was targeting at) and used to finalize the intervention materials (e.g., whether they preferred cartoon or photo for illustrations in the intervention materials and whether they were comfortable with the length of the text in the intervention materials).

Step 10: Piloting

Piloting is a preparatory investigation that provides specific information needed for planning subsequent studies (75). It can assist the researchers to identify potential problems as well as possible solutions (75). In this step, we tested the participants' understanding of our intervention materials and finalized these. Specifically, we reviewed comments raised about unintelligible, unacceptable, or offensive words within the intervention materials and revisions were made after considering the alternative words or expressions that best represent the acceptable and common language in Chinese culture. The intervention materials were piloted among four children (aged 10–12 years), four parents (whose child was aged 10–12 years), and four physical education teachers. They were purposively selected from a local primary school. Like step nine, we aimed for a variety of perspectives and different viewpoints. The intervention materials were shared with them to read and understand in their free time (i.e., children viewed materials for children, parents viewed materials for children and parents, teachers reviewed all materials). The shared intervention materials were reported in the result section (i.e., step eight, nine, and ten). The objectives were to identify any difficulties they had in reading and understanding the intervention materials (i.e., comprehension of content/instructions). Parents and teachers were requested to make suggestions for change or discuss any queries directly with the researchers. Teachers were requested to collect and record any queries that children had and report these to the researchers. Their feedback was used to finalize the intervention.

Results

Step 1: Define the Problem in Behavioral Terms

Physical inactivity among children is a serious public health problem. Evidence suggests that physical inactivity is significantly associated with many negative health (physical and mental) consequences, including increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, cancers, type 2 diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, anxiety, and depression (48, 49). We identified four systematic reviews that synthesized the reasons for low engagement in physical activity among Chinese children (14, 76–78). In summary, we synthesized that physical inactivity among children was a result of a combination of personal, social-cultural, environmental, and policy- and program-related factors (63, 64). All these factors should be taken into consideration when developing a behavior change intervention to increase physical activity among Chinese children.

Step 2: Select the Target Behavior

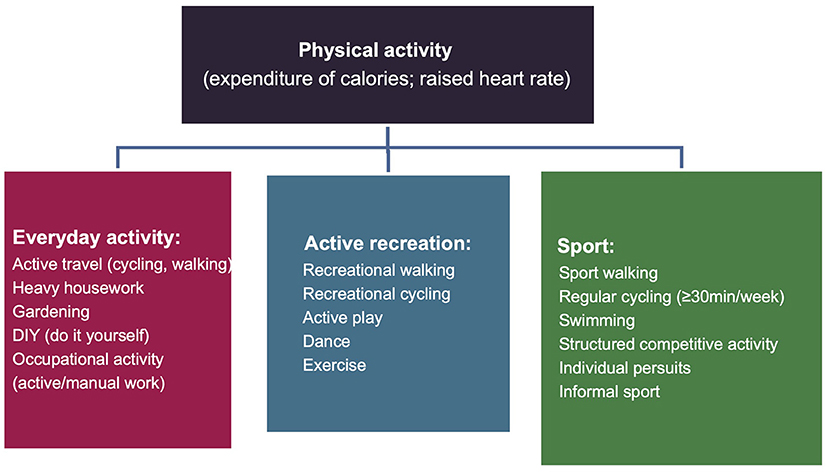

Physical activity is a complex behavior and can be divided into three domains: everyday activity (e.g., active travel, occupational activity), active recreation (e.g., active play, recreational walking, exercise), and sport (e.g., sport walking, structured competitive activity) (see Figure 2) (79). In China, the decline in children's physical activity can be found in all of these three domains, and this decline continues from childhood into adolescence. Regarding everyday activity, for instance, a great decline was reported in children's active travel (50). Specifically, there were only ~41% of Chinese children who traveled to school on foot or by bike in 2016 (51). In terms of active recreation, it has been significantly influenced by the increasing utilization of computer, television (TV), and video games (52). Children should not have more than 120 min of sedentary behavior per day (e.g., watching TV, using computers, playing video games) (53). However, over a third of Chinese children did not achieve this recommendation in 2016 (59). Chinese children are reported to have insufficient physical activity (sport) opportunities, and they spend the majority of their time on academic attainment (54–57). Previous research has reported an average of 9 h in school's weekday (ranges from 6.5 to 11.65 h) in Chinese schools (80). The majority of Chinese children are suggested to spend around 30–90 min per day on homework, and there are 30% of children who spend over 90 min on homework (21, 80). Chinese children have a higher study load than children from other areas of the world (around 14 h per week on homework compared to around 6 h in the US and 3 h in Finland) (80). In addition, more than 66% of Chinese children are having extracurricular tutoring classes each week. In contrast, only 24.7% of Chinese children participated in organized exercise sessions afterschool (6). In China, academic achievements are heavily emphasized and schools are evaluated based on their academic performances. As a result, schools prefer to allocate greater resources (including time) more to academic curriculum compared to physical activity (21, 22, 58). Overall, all these three domains were identified to be the pivotal domains. As suggested by the BCW, it is more effective to intervene intensively on one or two target behaviors than to intervene less intensively on multiple behaviors (37). Children's physical activity through active recreation at school appeared to be promising and could have a positive impact on children and their peers and parents. These criteria addressed that (i) how much of an impact changing the behavior would have on the desired outcome, (ii) how likely it is that the behavior could be changed, (iii) how likely it is that the behavior would have a positive or negative impact on other related behaviors, and (iv) how easy it would be to measure the behavior (37). Children spend the majority time of their waking hours in school, and therefore schools represent an ideal environment to reach the majority of school-aged children (81). Schools can provide access to children from different socioeconomic backgrounds and help institutionalize the physical activity programs into other settings, such as communities (81). Five to 45 min per day of improvement in MVPA can be achieved through school-based physical activity interventions (67). Based on existing literature, targeting schools to increase children's physical activity appears to be promising and is relatively easy to implement and reasonably easy to measure (60–62).

Step 3: Specify the Target Behavior

The behavior specification is detailed in Table 2. Previous systematic reviews on school-based physical activity interventions have identified that the increase in children's physical activity level can be potentially achieved through (i) active lunch breaks (i.e., providing opportunities for children to be physically active during the lunch break), (ii) classroom physical activity breaks (i.e., short breaks for doing physical activities), and (iii) education on being physically active (60, 61). The classroom physical activity breaks are highly effective in presenting opportunities for children to participate in a range of organized or unorganized physical activities (61, 62). Classroom physical activity breaks were therefore considered as an important intervention target time in our study. In terms of the people who could influence children's physical activity engagement, parents and teachers were identified as the integral “gatekeepers” because they play an important role in establishing children's health behaviors (14, 56). Parents and grandparents are likely to be over-attentive due to the “one-child policy” in China, and this may result in children having less intrinsic physical activity motivations (82). Beyond the parental influences, the role of teachers and peers is influential in shaping a child's physical activity behavior and has been identified as another important facilitator in the literature (14, 56, 76, 77). Altogether, children were identified as the intervention target, and their peers, teachers, and parents were identified as important people who may influence children's physical activities.

Step 4: Identify What Needs to Change

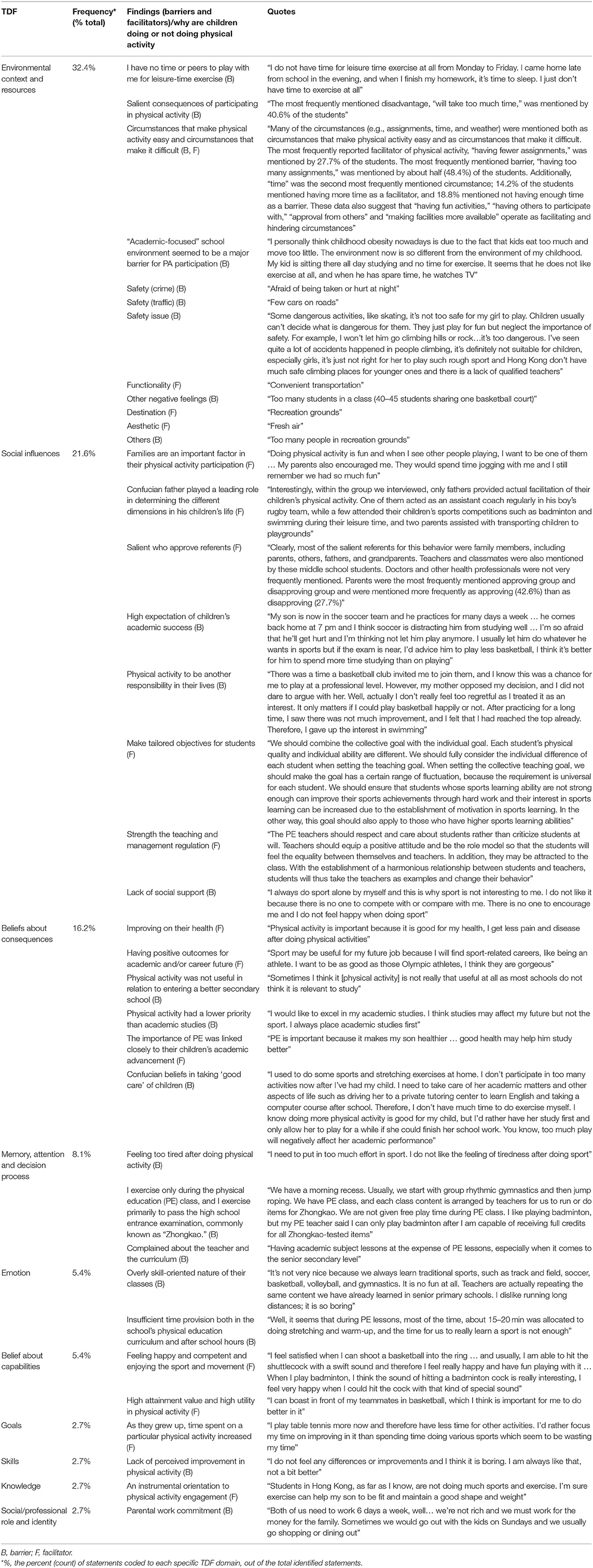

The findings of the systematic review are reported in detail elsewhere (64). Briefly, 11 studies were included in our systematic review explored the barriers and facilitators to physical activity among ethnic Chinese children and extracted 56 findings. Of which 37 findings were extracted from the studies conducted in the Chinese territories and 19 findings were from the studies in non-Chinese territories. Overall, 10 TDF domains were coded based on the findings of systematic review in this step (see Table 3). Of 37 extracted findings, the most commonly coded TDF domains accounting for 89.1% of the total findings were environmental context and resources (n = 12; 32.4%), social influences (n = 8; 21.6%), beliefs about consequences (n = 6; 16.2%), memory, attention, and decision process (n = 3; 8.1%), emotion (n = 2; 5.4%), and belief about capabilities (n = 2; 5.4%). The remaining findings were coded into other four TDF domains, which accounted for 2.7% (n = 1), respectively (e.g., belief about capabilities, skills, knowledge, social/professional role, and identity). Four domains (optimism, reinforcement, intentions, and behavioral regulation) were not identified from the 37 findings and thus were not coded. The table of TDF domains, findings, and quotations was made and organized hierarchically by percent frequency (see Table 3). Of 37 findings, 16 were facilitators and 22 were barriers. Only one finding (circumstances that make physical activity easy and circumstances that make it difficult) was discussed as both barrier and facilitator. In terms of the TDF domains, more barriers than facilitators were discussed relating to environmental context and resources (three facilitators, eight barriers, and one both) while only the social influences had more facilitators than barriers discussed in the domain (five facilitators, two barriers). As for the memory, attention and decision process, emotion, skills, and social/professional role and identity, only the barriers were discussed within these domains. In comparison, only facilitators were discussed in the domains of belief about capabilities, knowledge and motivation, and goals. Barriers and facilitators were equally discussed in beliefs about consequences.

Table 3. Summary of behavioral diagnosis using the TDF (quotes are taken verbatim from the systematic review).

Step 5: Identify Intervention Functions

All nine intervention functions were available for selection. Two intervention functions (i.e., coercion and restriction) were excluded as they did not meet the APEASE criteria (37). Coercion was not considered as practicable, acceptable, or equitable in the school context. The restriction was deemed not to be acceptable to children, parents, and teachers. Eventually, seven intervention functions were selected for this study design including education, persuasion, incentivization, training, environmental restructuring, modeling, and enablement.

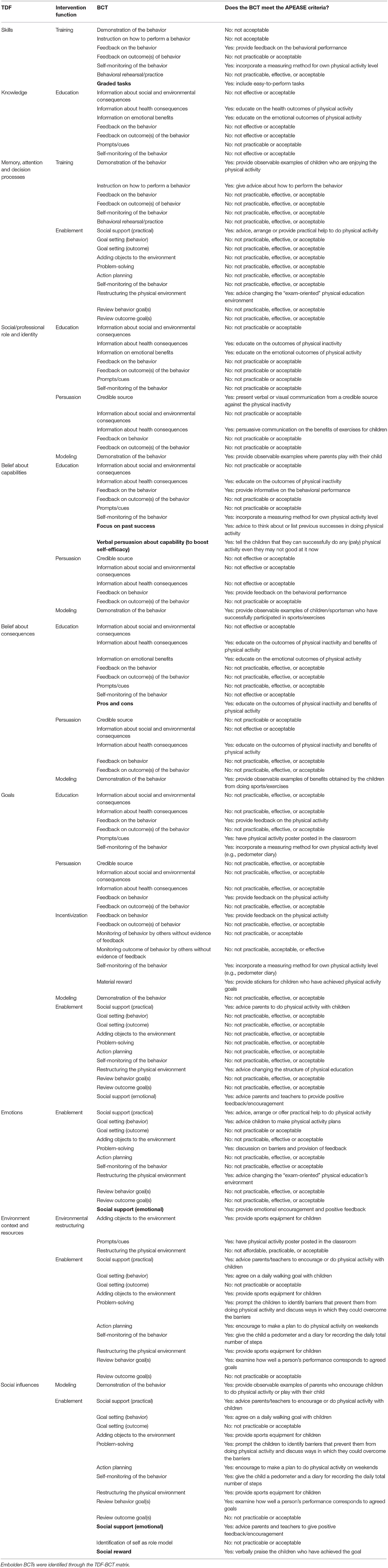

Step 6: Identify Behavior Change Techniques and Intervention Contents

In terms of the BCTs, 15 BCTs that best serve the seven intervention functions were first identified using the BCTTv1 taxonomy and then selected based on evaluation against the APEASE criteria (37, 65). Subsequently, a review of the matrix of TDF and BCTs identified six additional BCTs to include in this intervention (see Table 4) (84). As a result, there were 21 BCTs in total selected for the intervention.

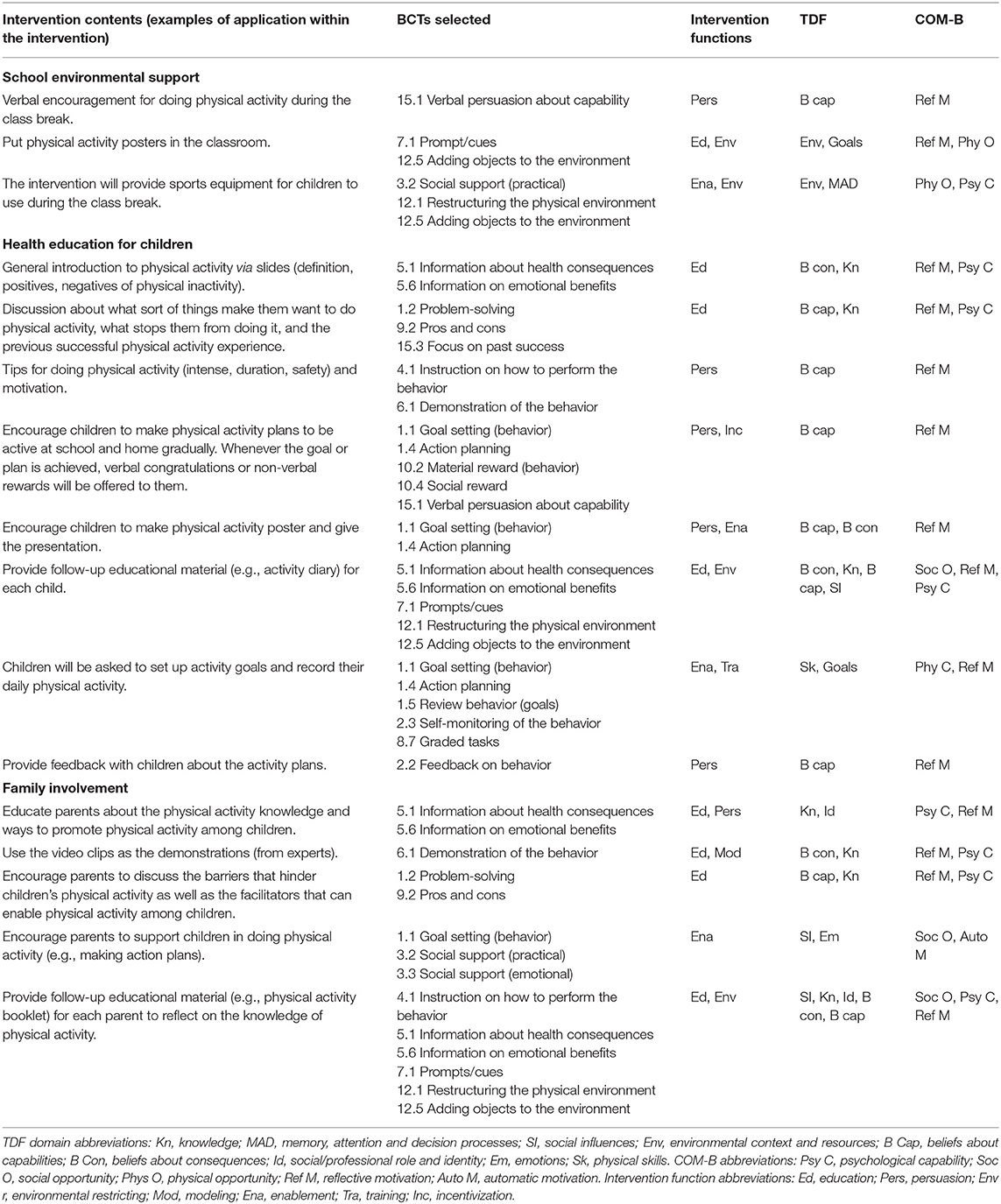

A summary of intervention functions, BCTs as well as examples of intervention contents that describe how the BCTs are delivered in the intervention is presented in Table 5. This table represents a summary of all the steps in the BCW and is the culmination of all the steps of the work in the current study. As suggested in step four, the barriers and facilitators were, by and large, related to the TDF domains of environmental context and resources; social influences; the belief about the consequences; memory, attention and decision process; and emotion. In other words, environmental, socio-cultural, and personal factors would be the priorities of our intervention, and the selected BCTs would help bring about the target behavior. Restructuring the physical environment is to make a change in the physical environment to help facilitate the performance of the target behavior (37). By adding objects to the environment (providing sports equipment) and using prompts/cues (e.g., poster), children's initiatives for doing physical activity may increase (see Table 5). The teachers will persuade the role of physical activity and encourage children to use the provided sports equipment.

Provision of information about health consequences/emotional benefits in the intervention could educate both children and parents. Additionally, the demonstration of the behavior could act as persuasion whenever there exists an opportunity for doing physical activity (see Table 5). Emphasizing the pros and cons, previous successful experience, and personal capacities in physical activity may encourage children to perform the activity voluntarily. Information that indicates when and how to perform physical activity is crucial content for the individuals and could act as a prompt or cue to action (see Table 5). Goal setting, graded tasks, and action planning were also identified as valuable BCTs and emphasize the importance of acting in the present but also planning for the future. Engaging children to self-monitor the behavior may facilitate the completion of individual actions and act as a springboard from which children can improve with feedback (on their behavior) from a health practitioner. Moreover, teachers and health practitioners will review the behavioral goals of children through the intervention to encourage them to act on their own self-set personalized goals (see Table 5). Other social support strategies will involve asking children to buddy up with friends [i.e., social support (emotional)] or parents to prepare sports gear for their children [i.e., social support (practical)]. Whenever a child achieves the physical activity goal, giving a social reward or material reward may help incentivize their motivation in keeping the desired behavior.

Step 7: Identify the Mode of Delivery

Several systematic reviews suggest that school-based interventions are the most effective way to counteract low physical activity in children aged 5–18 years, and it is typically made up of a combination of school curricula, printed educational materials, educational sessions, and physical activity-specific sessions (66, 67). In addition, previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of group-based sessions and printed media (e.g., poster, written materials) in helping increase children's physical activity level (44, 61, 68–71). As a result, the face-to-face (group) and distance (printed media) were selected as the modes of delivery.

Step 8, 9, 10: Expert Consultation, PPIE, and Piloting

As part of the intervention, we adapted a physical activity booklet, poster, slides, and two physical activity diaries (see Table 5). With permission, the information on children's physical activity, reasons behind the physical inactivity among children, and recommendations for helping increase children's physical activity were extracted from two existing booklets of the British Heart Foundation (UK), the websites of Better Health Channel (Australia), Caring for Kids (Canada), and two WHO reports (1, 85–89). These were adapted to the Chinese context and used in the physical activity booklet and slides for parents. The physical activity booklet was distributed among teachers to use as guidance for health education practices. In addition, the intervention includes video clips (i.e., physical activity expert's speech) to provide an introduction about children's physical activity among parents. The content of the slides for children was based on existing slides of the Zhejiang Center of Disease Control (China), and the poster was adapted from a poster produced by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (90, 91).

Rather than developing a completely new dairy, we adapted two existing theory- and evidence-based physical activity diaries (Steps for Active Kids (STAK) and STAK-Diabetes, UK). Both diaries were found to be effective in engaging children in physical activities (70, 71). With permission, the information on physical activity knowledge, recommendations to become physically activity and activity log to record daily physical activity, was extracted from both diaries as well as the Better Health Channel's website (70, 71, 87), and the materials were then adapted to the Chinese context. Two BCTs (information on emotional benefits and material rewards) were added to the intervention based on expert consultation. In addition, the disagreements that arose regarding the selection of certain intervention functions and BCTs (i.e., not appropriate or wrong coding) were addressed through iterative revisions until the consensus was reached. The intervention content, complex language, lengthy wording, inconsistent use of phrases and color scheme, and typos were addressed based on the expert consultation. For instance, experts' comments regarding the intervention content and complex language included:

• “Promoting a health behavior like physical activity does not mean that you must promote the health benefits of that behavior. Instead, you should focus on encouraging people to pursue activity for some intrinsically valued motive.”

• “Have you considered the whole issue of financial constraints and how to deal with it. For example, parents might say the only thing their daughter really wants to do is horse riding but they cannot afford it.”

• “The language used throughout the resources is quite technical/advanced.”

• “…particularly the slides both for parents/children and the booklet are that they are far too complex (especially for young children) and there is a lot of scientific language that is not appropriate for members of the public/children.”

• “The participant-facing wording is technical and not lay-friendly.”

• “Consider using ‘mental health’ instead of ‘psychological’.”

Experts' comments regarding the length wording included:

• “I have included suggestions of ways you could think about simplifying some of the language, particularly in the slides for the children in the comments function on PowerPoint, … see where you can simplify the language and cut down on as much text as possible where you can.”

• “You should simplify your wording throughout, so that it speaks to participants in their own language; not necessarily informal language, but a more simple and direct form of wording that resonates with them.”

Experts' comments regarding the inconsistent use of phrases, color scheme, and typos included:

• “I think you should use the language from the activity diary in your slides/booklet and use that consistently across all the intervention materials.”

• “The color scheme throughout these resources could be more consistent.”

• “Keep font size consistent throughout. Including size of titles.”

The cartoons (for physical activity illustration) used in the activity diary and slides for children were chosen based on the feedback received from children. The photo (for physical activity illustration) used in the physical activity booklet and slides for parents were chosen based on the feedback received from parents and teachers. For instance, PPIE comments regarding the preference of the photograph and length wording included:

• “I would prefer the cartoons because these are more appealing.”

• “I think cartoons are interesting and our teachers make slides in this way [use cartoons as illustrations] as well.”

• “I think cartoons are too childish for us [parents] and I would like the photo instead.”

• “I would suggest you use photos as illustrations in the materials for parents.”

• “I think the length is fine.”

• “I am fine with the length.”

All these intervention materials are available in English and Mandarin. The translation work was completed after PPIE. Translational and literal mistakes in the Mandarin version were corrected after the piloting work. For instance, comments from piloting regarding the translational (including unintelligible expressions), literal mistakes, and recommendations included:

• “The translation of title ‘Welcome to physical activity promotion’ program (not clear).”

• “Translation of ‘Tips for safely doing physical activity’ (not clear).”

• “Suggest to re-translate the phrase ‘become more active.”

• “Translation - Be creative and vary your child's activities (unclear).”

• “Please give the definition and benefits of physical activity in the end of presentation rather than give a brief summary. This could make children have a direct understanding and it may be easier for them to memorize.”

Discussion

We report the systematic development of a physical activity program for Chinese children aged 10–12 years. Physical activity interventions for Chinese children have previously been criticized for being underdeveloped or underreported (28–32). Among health practitioners and researchers, it is argued that a systematic and transparent theory-and-evidence-based approach can prevent research waste that is led by poor-quality research methods or researchers' biased manner. In our study, we supplemented this process with findings from a JBI qualitative systematic review (63, 64). This strengthens the likelihood of generalization as the intervention is based on a broader perspective that includes different contexts (e.g., school, home, community) and participants (children, parents, teachers). To our knowledge, the current study is the first to apply the BCW and TDF in this population and context. This systematic process identified 10 relevant TDF domains and selected seven interventions and 21 BCTs in the program. Three main components constitute the intervention, namely: (i) school environmental support, (ii) health education for children, and (iii) family involvement. The school environmental support is based on the provision of sports equipment, pedometers, and a physical activity poster. Health education for children is delivered via face-to-face mode using presentation slides and print materials including a physical activity diary. Family involvement is promoted via a face-to-face workshop and a physical activity booklet. Moving forward, a feasibility pre- and post-intervention study is being conducted to determine the feasibility of undertaking a cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) among Chinese children. The feasibility study has been registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR1900026865). If the intervention is found to be feasible and acceptable, we will design and conduct the cluster RCT.

In the cluster RCT, if the intervention is found to be effective, it could be a low-cost, acceptable and local solution for increasing the physical activity level among Chinese children. It may also alleviate the future personal and economic burden of physical inactivity on individuals, the health system, and the economy. The advantages of increasing physical activity in this population may extend to the prevention of physical inactivity related complications. This program of work means that evidence-based practices could be available to health professionals to promote physical activity among children. The intervention may simultaneously empower children or their parents to actively engage in physical activity. Given that physical inactivity and its related costs are global concerns, there could be worldwide interest in this low-cost behavior change theory-based physical activity program.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic approach provided insights to inform the development of a school-based physical activity program for Chinese children. We used the MRC framework along with existing evidence, which led to a logical, practical, and theory-based intervention. The use of the BCW and TDF helped categorize and comprehend potential barriers and facilitators to Chinese children's physical activity. Although several subjective and pragmatic decisions were made throughout the development process, detailed and transparent processes are presented in this paper to clarify why options were or were not taken. We conducted expert consultation on the intervention design, and this minimized risk of bias in the identification of domains, intervention functions, BCTs, and increased trustworthiness. In addition, the PPIE ensured the intervention would be appropriate in the Chinese context. Altogether, the developed intervention will be followed by a thorough evaluation (feasibility pre- and post-intervention study).

This work has several limitations. We identified our target behavior problem (in step 1) through an exploratory literature review and not a systematic review as there are existing systematic reviews and other primary studies to support this. The total count (frequency) of barriers or facilitators coded to each TDF domain was used as a proxy for importance. However, domains that coded infrequently might be highly important to determine the physical activity level among children. Therefore, the design and selection bias may delimit the effectiveness of the intervention. However, it should be noted that using the integrative theoretical framework (i.e., TDF) could enable all the necessary elements for our intervention program are in place to maximize potential benefits. As we were not primarily concerned with changing the policy in this study, the analysis of policy categories was not taken. Further studies are needed to carry out the analysis related to policy categories to help identify guidelines, regulations, and legislations useful for achieving behavioral change. Although expert consultation, PPIE, and piloting were part of the intervention development process, there could be selection bias as convenience sampling was used throughout, and recruitment for this input was undertaken through the researchers' professional and social networks. BCW provides a systematic, theory-driven, and evidence-based approach to develop an intervention that meets the unique needs of the target group. However, the process was time-consuming from problem identification to intervention design.

Conclusion

This paper describes how an intervention to increase physical activity in Chinese children was developed. We followed a systematic and transparent process using the BCW and TDF to exemplify the first phase (i.e., intervention development) when developing and evaluating a complex intervention. A school-based intervention facilitated by environmental support, health education, and family involvement may help to engage children in physical activity. A feasibility study is now being undertaken in the next phase to determine the acceptability and utility (initial estimates) of the program and the feasibility of undertaking a cluster RCT.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Nottingham.

Author Contributions

HW took the lead in writing the manuscript. HB and KC supervised the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded internally by the University of Nottingham. The funding agency had no role in conducting the study or writing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the participants who have contributed to the development of this intervention. We thank Cris Glazebrook for allowing us to adapt the Steps to Active Kids physical activity diary.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Available online at: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/ (accessed December 20, 2019).

2. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. (2012) 380:219–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

3. Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, Daniels SR, Dishman RK, Gutin B, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr. (2005) 146:732–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.01.055

4. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. (2020) 4:23–35. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2

5. Zhu Z, Tang Y, Zhuang J, Liu Y, Wu X, Cai Y, et al. Physical activity, screen viewing time, and overweight/obesity among Chinese children and adolescents: an update from the 2017 physical activity and fitness in China—the youth study. BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:197–204. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6515-9

6. Li P, Wang M, Wang-Fu BH. Comparison of physical activity levels between Chinese children and youth and global AHKC reports. Chin J Health Educ. (2017) 33:99–102. doi: 10.16168/j.cnki.issn.1002-9982.2017.02.001

7. Wang Z, Dong Y, Song Y, Yang Z, Ma J. Analysis on prevalence of physical activity time <1 hour and related factors in students aged 9-22 years in China, 2014. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. (2017) 38:341–5. doi: 10.3760/cmaj.issn.0254-6450.2017.03.013

8. He G, Cerin E, Huang W, Wong S. Understanding neighborhood environment related to Hong Kong children's physical activity: a qualitative study using nominal group technique. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e106578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106578

9. Li B, Lin R, Liu W, Chen J, Liu W, Cheng K, et al. Differences in perceived causes of childhood obesity between migrant and local communities in China: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. (2016) 12:e0177505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177505

10. Zhang R, Li H. Associated factors of physical exercise participation among primary and middle school students in Jiangsu. Chin J School Health. (2017) 38:1793–5. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2017.12.010

11. Chen L, Zou Y, Song Y, Liu Z. Physical activities of primary and middle school students and its influential factors in Jiangsu province. J Sports Adult Educ. (2011) 27:92–4. doi: 10.16419/j.cnki.42-1684/g8.2011.04.032

12. Guan Y. The physical activity of teenagers and influence factors in big cities in China. J Tianjin Univ Sport. (2005) 28–31.

13. Cheng K, Cheng P, Mak KT, Wong SH, Wong YK, Yeung EW. Relationships of perceived benefits and barriers to physical activity, physical activity participation and physical fitness in Hong Kong female adolescents. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. (2003) 43:523–9.

14. He Q. Analysis of influential factors to the formation of exercise habits among primary and middle school students. Contemp Sports Technol. (2015) 252−3. doi: 10.16655/j.cnki.2095-2813.2015.11.012

15. Veitch J, Bagley S, Ball K, Salmon J. Where do children usually play? A qualitative study of parents' perceptions of influences on children's active free-play. Health Place. (2006) 12:383–93. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.02.009

16. Kneeshaw-Price S, Saelens B, Sallis J, Glanz K, Frank L, Kerr J, et al. Children's objective physical activity by location: why the neighborhood matters. Pediatr Exerc Sci. (2013) 25:468–86. doi: 10.1123/pes.25.3.468

17. WHO. Spotlight on Adolescent Health and Well-Being: Findings From the 2017/2018 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Survey in Europe and Canada. Available online at: http://www.hbsc.org/publications/international/ (accessed September 20, 2020).

18. Scottish Office Department of Health. The Scottish Health Survey 2019. Available online at: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-health-survey-2019-volume-1-main-report/pages/3/ (accessed September 20, 2020).

19. Hesketh T, Zhen Y, Lu L, Dong ZX, Jun YX, Xing ZW. Stress and psychosomatic symptoms in Chinese school children: cross-sectional survey. Arch Dis Child. (2010) 95:136–40. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.171660

20. Zhao X, Selman RL, Haste H. Academic stress in Chinese schools and a proposed preventive intervention program. Cogent Educa. (2015) 2:1000477. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2014.1000477

21. Guo H, Yang Z. Study on time arrangement and daily status of primary school students in Beijing. Educ Sci Res. (2008) 29:31–2.

22. Just Landed. The American School System. Available online at: https://www.justlanded.com/english/United-States/USA-Guide/Education/The-American-school-system (accessed December 20, 2019).

24. Jiang L, Li C. Attribution and countermeasures of “1 hour” shrinkage of sunshine sports. J Teach Manage. (2017) 21–4.

25. Yang X. Rural-urban migration and mental and sexual health: a case study in Southwestern China. Health Psychol Behav Med. (2014) 2:1–15. doi: 10.1080/21642850.2013.839384

26. He L, Lin L. The tendency of the physical activity level among school-aged urban children in China. Chin J School Health. (2016) 37:636–40. doi: 10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2016.04.049

27. Jian Y, Wang B, Yang L, Huang M, Zheng L. The social security for sunny sports in elementary schools. J Jilin Inst Phys Educ. (2013) 29:109–13.

28. Li M, Li S, Baur LA, Huxley RR. A systematic review of school-based intervention studies for the prevention or reduction of excess weight among Chinese children and adolescents. Obes Rev. (2008) 9:548–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00495.x

29. Gao Y, Griffiths S, Chan EYY. Community-based interventions to reduce overweight and obesity in China: a systematic review of the Chinese and English literature. J Public Health. (2008) 30:436–48. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm057

30. Lin F, Wei D, Lin S, Maddison R, Mhurchu CN, Jiang Y, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based obesity interventions in mainland China. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0184704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184704

31. Li Y, Hu X, Schouten EG, Liu A, Du S, Li L, et al. Report on childhood obesity in China: effects and sustainability of physical activity intervention on body composition of Chinese youth. Biomed Environ Sci. (2010) 23:180–7. doi: 10.1016/S0895-3988(10)60050-5

32. Liu A, Hu X, Ma G, Cui Z, Pan Y, Chang S, et al. Evaluation of a classroom-based physical activity promoting programme. Obes Rev. (2008) 9(Suppl. 1):130–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00454.x

33. Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. (2014) 17:637–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x

34. Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci. (2011) 6:42–53. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

35. Hansen S, Kanning M, Lauer R, Steinacker JM, Schlicht W. MAP-IT: a practical tool for planning complex behavior modification interventions. Health Promot Pract. (2017) 18:696–705. doi: 10.1177/1524839917710454

36. Davies P, Walker AE, Grimshaw JM. A systematic review of the use of theory in the design of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies and interpretation of the results of rigorous evaluations. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-14

37. Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing (2014).

38. Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. (2012) 7:37–53. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

39. Barker F, Lusignan Sd, Deborah C. Improving collaborative behaviour planning in adult auditory rehabilitation: development of the I-PLAN intervention using the behaviour change wheel. Ann Behav Med. (2017) 52:489–500. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9843-3

40. Loft MI, Martinsen B, Esbensen BA, Mathiesen LL, Iversen HK, Poulsen I. Strengthening the role and functions of nursing staff in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: developing a complex intervention using the Behaviour Change Wheel. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. (2017) 12:1392218. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2017.1392218

41. Smits S, McCutchan G, Wood F, Edwards A, Lewis I, Robling M, et al. Development of a behavior change intervention to encourage timely cancer symptom presentation among people living in deprived communities using the behavior change wheel. Ann Behav Med. (2017) 52:474–88. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9849-x

42. Murtagh E, Barnes A, McMullen J, Morgan P. Mothers and teenage daughters walking to health: using the behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to improve adolescent girls' physical activity. Public Health. (2018) 158:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.012

43. Munir F, Biddle SJ, Davies MJ, Dunstan D, Esliger D, Gray LJ, et al. Stand More AT Work (SMArT Work): using the behaviour change wheel to develop an intervention to reduce sitting time in the workplace. BMC Public Health. (2018) 18:319–33. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5187-1

44. Xu F, Ware RS, Leslie E, Tse LA, Wang Z, Li J, et al. Effectiveness of a randomized controlled lifestyle intervention to prevent obesity among Chinese primary school students: CLICK-obesity study. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0141421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141421

45. Li B, Liu W, Cheng K, Pallan M, Hemming K, Frew E, et al. Development of the theory-based Chinese primary school children physical activity and dietary behaviour changes intervention (CHIRPY DRAGON): development of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. (2016) 388:S51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31978-X

46. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud. (2013) 50:587–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010

47. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. (2014) 348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687

48. Lan Z, Luo Y. A research on the effect of the physical education at school to students' mentality health education. J Sports Sci. (2003) 24:72–4.

49. Zhang Y, Ma S, Chen C, Liu J, Zhang C, Cao Z, et al. Physical activity guide for children and adolescents in China. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr. (2017) 12:401–9. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5501.2017.06.001

50. Bell AC, Ge K, Popkin BM. The road to obesity or the path to prevention: motorized transportation and obesity in China. Obesity. (2002) 10:277–83. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.38

51. Liu Y, Tang Y, Cao Z, Chen P, Zhang J, Zhu Z, et al. Results from Shanghai's (China) 2016 report card on physical activity for children and youth. J Phys Activity Health. (2016) 13(11 Suppl. 2):S124–8. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2016-0362

52. Luis AM, Iris P, Wolfgang A. Epidemiology of Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Prevalence and Etiology. Prevalence and Etiology. New York, NY: Springer (2011).

53. Viner R, Davie M. The Health Impacts of Screen Time: A Guide for Clinicians and Parents. Available online at: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-12/rcpch_screen_time_guide_-_final.pdf (accessed December 20, 2019).

56. He L, Wang X, Lin L. Factors associated with physical activity of school age children in Chinese cities: a systemic review based on a social ecological model. Urban Plann Int. (2016) 31:10–5. doi: 10.22217/upi.2016.216

57. Pang B. Promoting physical activity in Hong Kong Chinese young people: factors influencing their subjective task values and expectancy beliefs in physical activity. Eur Phy Educ Rev. (2014) 20:385–97. doi: 10.1177/1356336X14534360

58. Ma J, Wu J. Why is the academic burden reduction policy hard to achieve? On the nature and mechanism of time allocation of academic burden. J Beijing Normal Univ. (2014) 59:5–14.

59. Cai Y, Zhu X, Wu X. Overweight, obesity, and screen-time viewing among Chinese school-aged children: national prevalence estimates from the 2016 physical activity and fitness in China—the youth study. J Sport Health Sci. (2017) 6:404–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2017.09.002

60. Owen KB, Parker PD, Van Zanden B, MacMillan F, Astell-Burt T, Lonsdale C. Physical activity and school engagement in youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Educ Psychol. (2016) 51:129–45. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1151793

61. Watson A, Timperio A, Brown H, Best K, Hesketh KD. Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2017) 14:114–37. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0569-9

62. Hills AP, Dengel DR, Lubans DR. Supporting public health priorities: recommendations for physical education and physical activity promotion in schools. Progress Cardiovasc Dis. (2015) 57:368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.09.010

63. Wang H, Blake H, Chattopadhyay K. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity among ethnic Chinese children: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. (2019) 17:1–8. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003865

64. Wang H, Blake H, Chattopadhyay K. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity among ethnic Chinese children in school, home and community settings: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. (2020) 18:2445–511. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00154

65. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. (2013) 46:81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

66. Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, van Sluijs EMF, Andersen LB, Martin BW. Effect of school- based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med. (2011) 45:923–30. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090186

67. Dobbins M, DeCorby K, Robeson PH, Tirilis D. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6-18. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) CD007651. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007651.pub2

68. Sutherland R, Campbell E, Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Okely AD, Nathan N, et al. A cluster randomised trial of a school-based intervention to prevent decline in adolescent physical activity levels: study protocol for the ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone’ trial. BMC Public Health. (2013) 13:57–66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-57

69. Jago R, Sebire SJ, Davies B, Wood L, Banfield K, Edwards MJ, et al. Increasing children's physical activity through a teaching-assistant led extracurricular intervention: process evaluation of the action 3: 30 randomised feasibility trial. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:156. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1501-3

70. Glazebrook C, Batty MJ, Mullan N, MacDonald I, Nathan D, Sayal K, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a schools-based programme to promote exercise self-efficacy in children and young people with risk factors for obesity: steps to active kids (STAK). BMC Public Health. (2011) 11:830–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-830

71. Quirk H, Glazebrook C, Blake H. A physical activity intervention for children with type 1 diabetes-steps to active kids with diabetes (STAK-D): a feasibility study. BMC Pediatr. (2018) 18:37–48. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1036-8

72. NIHR INVOLVE. What Is Public Involvement in Research? Available online at: https://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/ (accessed January 11, 2021).

73. Kaisler RE, Missbach B. Co-creating a patient and public involvement and engagement ‘how to’ guide for researchers. Res Involvement Engage. (2020) 6:32. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00208-3

74. NIHR INVOLVE. Briefing Note Six: Who Should I Involve and How Do I Find People? Available online at: https://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/ (accessed January 11, 2021).

75. Moore CG, Carter RE, Nietert PJ, Stewart PW. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin Transl Sci. (2011) 4:332–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00347.x

76. Liu F, Xie C. The review of the extracurricular exercise participation among middle school students. Modern Commun. (2011) 25:117–8.

77. Qian J, Ma D. The review of the exercise and sports among middle school students. Sports World. (2014) 43:60–2. doi: 10.16730/j.cnki.61-1019/g8.2014.08.010

78. Yuan A, Lei Y. Discussion on the influencing factors and countermeasure of physical health in elementary school students. J Shaoyang Univ. (2017) 14:77–83.

79. Department of Health. Start Active, Stay Active a Report on Physical Activity for Health From the Four Home Countries' Chief Medical Officers. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/830943/withdrawn_dh_128210.pdf (accessed December 20, 2019).

80. Zhang J, Tang Y, Chen P, Liu Y, Cao Z, Hu Y, et al. The report card of Chinese city children and youth physical activity based on AHKGA-take Shanghai as example. China Sport Sci. (2017) 37:14–27. doi: 10.16469/j.css.201701002

81. Chen Y, Ma L, Ma Y, Wang H, Luo J, Zhang X, et al. A national school-based health lifestyles interventions among Chinese children and adolescents against obesity: rationale, design and methodology of a randomized controlled trial in China. BMC Public Health. (2015) 15:210–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1516-9

82. Jiang J, Xia X, Greiner T, Lian G, Rosenqvist U. A two year family based behaviour treatment for obese children. Arch Dis Child. (2005) 90:1235–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.071753

83. Gao J, Chen P. Study of daily physical activity status of adolescents in Jiangsu Province. J Nanjing Sport Institute (Natural Science). (2015) 14:103–8. doi: 10.15877/j.cnki.nsin.2015.02.023

84. Cane J, Richardson M, Johnston M, Ladha R, Michie S. From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. Br J Health Psychol. (2015) 20:130–50. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12102

85. British Heart Foundation. Get Active, Stay Active. Available online at: https://www.bhf.org.uk/-/media/files/publications/being-active/g12_get_active_stay_active.pdf (accessed March 6, 2020).

86. British Heart Foundation. Physical Activity for Children and Young People, Evidence Briefing. Available online at: http://www.ncsem-em.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/cyp_evidence_briefing.pdf (accessed March 6, 2020).

87. Beter Health Channel. Physical Activity - Staying Motivated. Available online at: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/physical-activity-staying-motivated (accessed March 6, 2020).

88. Caring for Kids. Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Available online at: https://www.caringforkids.cps.ca/handouts/physical_activity (accessed March 6, 2020).

89. WHO. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. (2009). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44203/9789241563871_eng.pdf (accessed September 20, 2020).

90. ZheJiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity and Health. Available online at: https://wenku.baidu.com/view/9be7b5cbcc175527072208e3.html (accessed March 6, 2020).

91. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Youth Physical Activity Guidelines Poster. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physicalactivity/toolkit/poster_pa_guidelines_poster.pdf (accessed March 6, 2020).

Keywords: China, exercise, sport, child, systematic process, intervention development

Citation: Wang H, Blake H and Chattopadhyay K (2021) Development of a School-Based Intervention to Increase Physical Activity Levels Among Chinese Children: A Systematic Iterative Process Based on Behavior Change Wheel and Theoretical Domains Framework. Front. Public Health 9:610245. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.610245

Received: 25 September 2020; Accepted: 16 March 2021;

Published: 27 April 2021.

Edited by:

Vijay S. Gc, University of York, United KingdomReviewed by:

Warren G. McDonald, Methodist University, United StatesAndrew Brinkley, Loughborough University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Wang, Blake and Chattopadhyay. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haiquan Wang, aGFpcXVhbi53YW5nQG5vdHRpbmdoYW0uYWMudWs=

Haiquan Wang

Haiquan Wang Holly Blake

Holly Blake Kaushik Chattopadhyay1,2

Kaushik Chattopadhyay1,2